Abstract

Objective

Informational support is an important pillar of psychosocial care for parents of children with cancer. Understanding the information needs of these parents may improve the provision of family-centered informational support. This paper aims to explore the information needs of Malaysian parents whose children have cancer.

Methods

This qualitative study was conducted among 14 parents of children with cancer and 8 healthcare providers. The parents were recruited from two urban pediatric oncology centers in Malaysia. Healthcare providers were recruited from these centers, as well as from community-based palliative care providers. In-depth interviews were conducted based on semi-structured topic guides, audio-recorded, and transcribed for thematic analysis using elements of the grounded theory approach.

Results

Analysis revealed three themes of information needs, which were: “interaction with the healthcare system,” “care for the child at home” and “psychosocial support for parents”. Information needs on parents’ interaction with the healthcare system consisted of disease and treatment-related information, as well as health system navigation. Information needs on care for the child at home were represented by their caregiving for basic activities of daily living, medical caregiving, and psychosocial caregiving. Psychosocial support for parents included information on practical support and self-care. There were differences in priorities for information needs between parents and healthcare providers.

Conclusions

Meeting the information needs of parents is an important part of psychosocial care in pediatric cancer care. Informational support may empower parents in caregiving for their child. The development of suitable information resources will be invaluable for healthcare providers in supporting parents’ needs.

Keywords: Cancer, Information needs, Psychosocial support, Nursing, Parents, Pediatrics

Introduction

Childhood cancer is an important cause of morbidity in children, being the ninth leading cause of child disease burden worldwide.1 Common childhood cancers include hematological malignancies such as leukemia and lymphoma, central nervous system tumors, neuroblastomas, and kidney tumors such as Wilm’s tumor.2 The rapid advancement of pediatric oncology has resulted in a better prognosis for cure and survival for childhood cancers, particularly in high-income countries. The 5-year survival rate for childhood cancers was reported to be about 80% in high-income countries.2 However, there is insufficient quality data on outcomes for childhood cancers for low- and middle-income countries. South Asia and South-East Asia were regions with the highest disability-adjusted life year (DALY) burden for childhood cancers.1 The Malaysian National Cancer Registry reported 3829 cases of cancer in children aged 0–18 years between 2012 and 2016.3 An updated report was not available at the time of writing.

Although childhood cancers have a relatively better prognosis compared to cancers in adults, this does not negate the trauma or distress experienced by parents when their children are diagnosed with cancer. Often, the diagnosis was unexpected, and parents found themselves swept into a whirlwind of caregiving demands from diagnosis, treatment, and home care while maintaining their other commitments.4 Psychosocial support for parents is crucial and recognized as a priority in standards of care for pediatric oncology.5, 6, 7 It is extremely important to support parents in their role as a caregiver because their well-being may also affect their children’s outcomes.

Information support is one of the pillars of the cancer supportive care framework.8 Parents of children with cancer have information needs that reflect their supportive care needs. Based on past studies, the information needs of parents of children with cancer are quite extensive, ranging from disease-related information, treatment-related information, care for their child, practical information on resources, and coping strategies.9, 10, 11 However, most of these studies were conducted among Western populations in high-income countries with relatively more healthcare resources and presumably better health literacy. Relatively fewer studies were conducted among Asian cultures or in low- and middle-income countries such as Malaysia. The role of culture and availability of resources could possibly influence parents’ information needs.

Provision of psychoeducation and information is one of the strongly recommended international standards of care for childhood cancer.12 In Malaysia, there are only 10 public pediatric oncology treatment centers. Resources for psychosocial support are limited and vary by location. Most centers do not have a pediatric oncology nurse to oversee the provision of psychosocial support for the patients and their families. Psychologists are also available only in bigger centers and largely provide services for various other conditions besides pediatric oncology. There is great heterogeneity in the availability and accessibility to healthcare and psychosocial services for children with cancer, particularly in suburban or rural areas. Due to these major limitations, it can be difficult to meet the international standards for psychosocial care, including providing regular psychosocial needs assessments and access to psychosocial interventions.

Informational needs of Malaysians may be different from previous studies due to the local healthcare system and sociocultural environment. Information such as diagnosis-related and treatment-related information may need to be individualized to the caregivers’ health literacy, culture, and psychological readiness.9,13 Parents may benefit from the information that assists them in navigating the healthcare system.14 Caregivers need to be empowered during the process of information transfer.15 However, at the moment, information support for parents in most centers is provided based on clinician judgment, and there are insufficient suitable materials to support the communication process. Exploring the needs of the parents will help to develop educational materials to facilitate educational materials and communication.

Information needs may differ for different phases of the cancer trajectory, in tandem with the evolving stress and emotional impact of caregiving over time.16 Parents of children with cancer also have different supportive care needs as they transition from diagnosis to treatment.9 The cancer trajectory for their children may be categorized into different phases of the diagnostic evaluation, primary and adjuvant treatment, post-treatment and surveillance care, treatment of recurrence, and palliative care.17 More insights may be obtained by eliciting the information needs from parents over various phases of the cancer trajectory.

Including views from healthcare providers could complement the understanding of the information needs of parents. Healthcare providers may perceive different information needs that may not be apparent to parents themselves.6,18 Healthcare providers are also more aware of information regarding treatment, symptoms management, or availability of resources that could support parents. Hence it is important to include healthcare providers’ views in exploring parents’ information needs.

Informational support may facilitate emotional support and build resilience for caregivers of children with cancer. These may include knowledge of how to cope with stress and self-care.19 Knowledge on how to navigate the health system also may reduce anxiety and stress, resulting in better emotional health for caregivers.20 Therefore, informational support is crucial for parents of children with cancer as they provide the necessary support for their children. Identifying parents’ informational needs will be invaluable to guide the development of resources to support communication and caregiver education.

This paper aimed to explore the informational needs of parents of children with cancer receiving care from two public pediatric oncology centers in Malaysia. The research question to be addressed by this study was “What are the information needs of Malaysian parents of children with cancer?”

Methods

A qualitative approach was selected to explore the informational needs via semi-structured in-depth interviews. This qualitative study used elements of the grounded theory approach proposed by Charmaz.21 These included theoretical sampling, reflexivity, use of constant comparative methods, and interpretive constructivist approach in analysis. No underpinning theory was used during analysis, but data were used to generate theory. The theory is defined as a big idea that organizes many other ideas or concepts to define and explain phenomena.22,23 In line with the study objectives, this study aimed to generate a theory to provide an in-depth description and explanation about the informational needs of parents of children with cancer.

The study was conducted at two public pediatric oncology centers. One is the national tertiary referral center for pediatrics under the Ministry of Health Malaysia. The other center is a teaching hospital under a public university. These two centers were different in caseloads and availability of supportive care services such as pediatric palliative care and child psychology support. Treatment costs were fully subsidized in the first center, whereas in the second center, it was only partially subsidized.

This study obtained ethical approval from the Medical Research Ethics Committee for both institutions (Approval No. JEP-2020-550 and NMRR-20-1636-55775). All participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Participants for this study included parents of children diagnosed with cancer and various healthcare professionals involved in providing care for children with cancer. The inclusion criteria for parents recruited for this study included their child receiving treatment from the two study sites, ability to understand and converse in Malay or English language. Care was taken to sample participants from a variety of childhood cancer diagnoses (such as hematological and solid tumors) and at various stages of the cancer trajectory. Parents were excluded if they felt emotionally unprepared for an interview. Healthcare professionals who were included in this study had to be providing care for children with cancer within the preceding 1 year. Sampling was also varied to include different levels of work experience, different professions (doctors, nurses, pharmacists), and settings (hospital or community-based). A pharmacist involved in the process of medication counseling for pediatric oncology parents was interviewed. Community-based healthcare professionals were recruited from nongovernmental organizations providing community palliative care to both adults and children. They provided supportive care to families of children with cancer discharged to the community who may be concurrently receiving active treatment or end-of-life care. Their input was valuable as they were able to observe how families functioned in their home settings without close supervision or support of healthcare staff, unlike in the hospital setting.

Participants were sampled using purposive sampling to obtain maximum variation. Parents were approached in the pediatric oncology wards of both centers. Interviews with parents were conducted face-to-face in a quiet area in the pediatric oncology ward. Interviews with healthcare providers were done either face-to-face or via an Internet voice call due to social restrictions posed by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. There were no nonparticipants present during the interviews. These interviews were semi-structured based on the topic guide in Table 1. Each interview lasted between 35 min and 80 min. All participants were informed beforehand that the interview would be discontinued if they felt too emotionally distressed by the interview process. However, all participants were able to complete the interviews without problems.

Table 1.

Interview topic guide.

Topic guide for parents

|

Topic guide for hospital-based healthcare providers

|

Data collection was conducted from October 2020 until March 2021, when thematic data saturation was achieved. This was done through concurrent analysis of the data during the data collection phase. The interviews were conducted by a primary care physician trained in qualitative interviews, who had no influence on the children’s treatment and no prior knowledge of the parents prior to study recruitment. This was important to prevent bias during the interview process. Preliminary themes noted from the interview were recorded in the memos after each interview. This was further confirmed after thematic analysis. Data saturation was achieved when no new themes emerged despite interviewing participants from different characteristics. Field notes were written by the principal researcher during and after the interviews. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for thematic analysis using Nvivo by QSR International Ltd. The transcripts were transcribed in the language of the interview by local bilingual transcribers proficient in Malay and English.

Analysis was done using constant comparative methods to identify related concepts to form meaningful themes and categories. These themes and categories were recorded in a codebook that evolved during data analysis. All coding was done by the principal researcher, as this was part of her doctoral project, and thus no inter-rater agreement analysis was done. The researcher, being proficient in both Malay and English languages, coded the transcripts in both languages.

Themes and categories identified from the analysis were recorded in a codebook. These categories were assigned descriptions and representative quotes to guide subsequent coding. Open coding was done for the first round of analysis without using a predetermined theoretical framework.24,25 Subsequent rounds of analysis employed axial coding and theoretical coding. The Supportive Care Framework was used as an initial guide for theoretical coding, but care was taken not to restrict the emergence of new themes within this framework.8 This allowed new theory or explanation to surface beyond the selected theoretical framework.

The coresearchers comprised two pediatric oncologists, a pediatric palliative pediatrician, a senior consultant pediatric clinical geneticist, and a senior consultant family medicine specialist with experience in running a cancer education resource center. They evaluated the codes and relevant participant quotes, as well as the descriptions assigned to each code, based on their content expertise, clinical and work experience. Any disagreements were discussed openly by providing justifications, and a consensus was obtained for the final decision. Reflexivity was maintained by recording field notes and memos during the process of interviews and analysis. Reflexive memos during analysis also helped to shape the emerging theory and to ensure that the analysis was not overshadowed by the theoretical framework or personal biases. The coding structure was then illustrated using concept maps to facilitate visualization.

Results

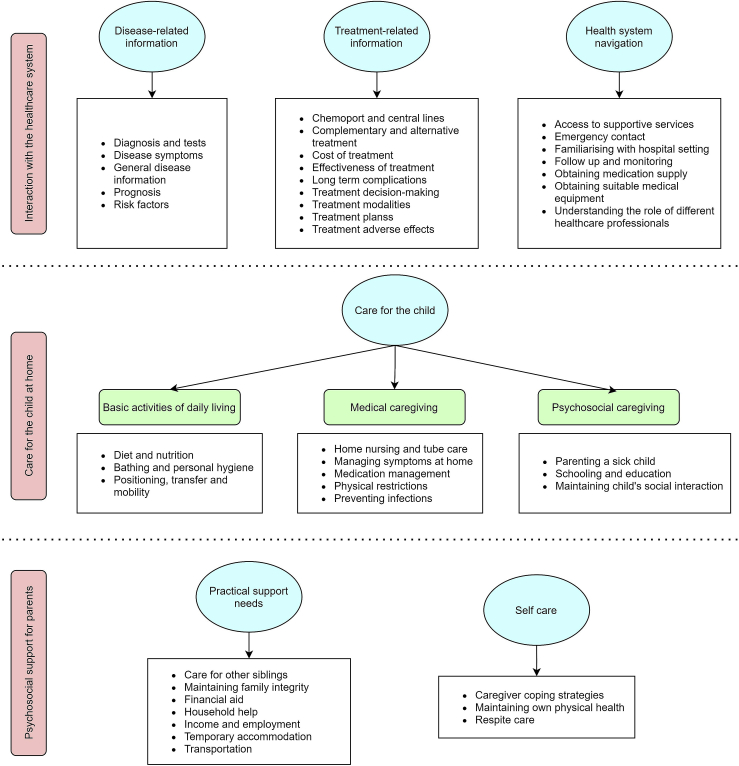

A total of 14 parents and 8 healthcare providers were interviewed in this study. Table 2 shows the characteristics of participants in this study. The informational needs were clustered into three main themes that were related to parents’ main roles of caregiving (Figure 1 for the theme structure and Table 3 for the descriptions and quotes of the subthemes).

Table 2.

Participant characteristics.

| Caregiver | Relationship to child | Ethnicity | Child’s age | Child’s diagnosis | Child’s treatment phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C01 | Mother | Kadazan | 2y 7m | AML | Induction phase chemotherapy |

| C02 | Mother | Malay | 5y 4m | AML | Induction phase chemotherapy |

| C03 | Both parents | Malay | 11y | ALL | Maintenance phase chemotherapy |

| C04 | Father | Malay | 8y | ALL | Maintenance phase chemotherapy |

| C05 | Mother | Indian | 3y | ALL | Maintenance phase chemotherapy |

| C06 | Father | Malay | 11y | Hepatoblastoma | Post-surgery, on chemotherapy |

| C07 | Mother | Malay | 4y | Neuroblastoma | Completing chemotherapy, planned for surgery |

| C08 | Mother | Malay | 13y | Osteosarcoma | Chemotherapy, planned for surgery |

| C09 | Father | Indian | 15y | Osteosarcoma | Post-surgery, on chemotherapy |

| C10 | Mother | Malay | 11y | Germ cell tumor | Chemotherapy, planned for radiotherapy |

| C11 | Mother | Malay | 8y | Pontine glioma | Palliative radiotherapy |

| C12 | Mother | Chinese | 8y | Pontine glioma | Palliative radiotherapy |

| C13 | Father | Chinese | 12y | Lymphoma | Relapse, on chemotherapy |

| Healthcare provider | Role | Setting | Work experience with pediatric cancer patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCP01 | Pediatrician | Hospital | 10 years |

| HCP02 | Postgraduate pediatric trainee | Hospital | 5 years |

| HCP03 | Palliative nurse | Community | 7 years |

| HCP04 | Palliative nurse | Community | 7 years |

| HCP05 | Postgraduate pediatric trainee | Hospital | 10 years |

| HCP06 | Palliative doctor | Community | 10 years |

| HCP07 | Pharmacist | Hospital | 5 years |

| HCP08 | Registered nurse | Hospital | 7 years |

AML: acute myeloid leukemia; ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Figure 1.

Theme structure.

Table 3.

Themes, subthemes, and participant quotes.

| Theme and description | Subthemes | Description of subthemes | Selected participant quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Interaction with the healthcare system Information regarding the disease, treatment, and how to navigate the healthcare system |

Disease-related information

|

Information related to the disease | Clinicians have to be very, how do we put it, very understanding and this and explain to the most basic level so that the parents do understand what this diagnosis means. If medulloblastomas, who does it mean? Where is it located? And what can it implicate? What can it affect and how will the progress be like? – HCP06General disease information I see, what symptoms were present before this, in my child. Then I try to remember, did my child have them before this? Or did we not realize or forget? – C05Disease symptoms I tried to search for my child’s diagnosis of hepatoblastoma. From the percentage, 90% of those who underwent surgery and chemo, will usually recover, based on my search. – C06Prognosis |

Treatment-related information

|

Information related to treatment | They will sometimes… not always… they will sometimes tell us things like, “Ah yeah! There’s another kid also with similar condition and hospice also seeing.. and he was trying this alternative treatment, and it has.. it seems to be quite well.” – HCP03Complementary and alternative treatment Because the doctor said the condition was serious, and so that my child can recover quickly, I was willing to agree for surgery and for chemotherapy – C06Treatment decision-making Each time the doctor gives the medications, she will explain.. okay, for example, if they give MTX, he will get ulcers, so he will need to gargle and clean his mouth regularly. – C03Treatment adverse effects |

|

Health system navigation

|

Information on how parents can access the health system effectively and reduce barriers for healthcare services | If they have PT/OT [physiotherapist or occupational therapist], can they suggest something that is practical and something that’s more practical to the parents since they have kids, right? Maybe like stroller or any other equipment that they might have known? – HCP03Obtaining suitable medical equipment Some parents don’t know the importance of coming for follow ups… You need to like explain to them, they can’t really like stop the medications on their own, right? – HCP08Follow up and monitoring It would be very helpful if they can explain what is the difference between the PC [palliative care] team in the hospital and the PC team in the community. What are the limitations the community team may face… – HCP06Understanding the role of different healthcare professionals |

|

|

Care for the child at home Direct caregiving for the sick child |

Basic activities of daily living

|

Caregiving related to the child’s basic needs for daily living | I asked the doctor about diet. The doctor told us, can give any food, but some types like vegetables need to be cleaned thoroughly and cooked properly. Cannot eat vegetables that are partially cooked or soft-boiled eggs. – C02Diet and nutrition Worried of vomiting if she doesn’t want it [the food]. If we force, she may totally refuse to eat. This will disturb her meals. So, to get her to eat, we get the vegetables that she will eat. – C06Behavioral issues related to feeding So once I bring my child home, then where do I put him or her, how do I position him or her, you know. If let’s say for feeding, what do I do? And then, if let’s say, they’re uncomfortable, then how do I make them more comfortable using whatever I have at home? – HCP04Positioning, transfer, and mobility |

Medical caregiving

|

Caregiving related to child’s medical and healthcare needs | If at home, we have to clean it ourselves. So at the hospital, the doctor will say, before you go back, when she was first admitted, before you go back, you need to learn how to clean it. If you don’t pass, you cannot go home. – C07Home nursing and tube care Which symptoms they need to panic? Which symptoms may not need so much of panicking? When do you need to rush to the hospital and when it can be handled at home? – HCP06Managing symptoms at home What we needed to know were the timing for the medications, because we need to know about the medications.. we needed information on how much is the dose, how to keep the medications, so these things are important to us – C04Medication management We did not simply accept visitors right now. Even if neighbors wanted to visit, we said for now, we said it nicely.. I told them we don’t want to accept visitors yet because my child is still in poor condition. They understand. – C04Preventing infections |

|

Psychosocial caregiving

|

Caregiving related to the child’s psychological and social well-being | The parents’ roles, in handling whatever issue regardless whether it’s education or whatever.. the main are the parents, not teachers, not doctors.. Doctors only help but the main role is the parents’.. – C04Parenting a sick child The doctors did explain that at the moment he can’t go to school, because he has many hospital appointments. Daycare once a week. After that, chemotherapy three times a week right? – C08Schooling and education |

|

|

Psychosocial support for parents Provision of support to meet the psychological and social needs of parents of children with cancer |

Practical support needs

|

Tips or advice to obtain practical support. | His younger sister also needs my care. If I come here, who will take care of my other children? My sister is around, it’s easier for me. She takes care of them at home. – C09Care for other siblings Sometimes, if we don’t have to bring him along, my husband and I come on a motorcycle. I only rode the motorcycle... Sometimes, if we need to bring him, then we need a car. And if we take the car, we need to find parking... – C08Transportation |

Self-care for caregivers

|

Tips or advice on maintaining own health to enable parents to continue caring for the child | If we are not strong, don’t take care of ourselves, how can we show to our child, so that she will be strong, right? If we just become like children and cry, our child will become weaker right? Even weaker. – C06Caregiver coping strategies Thank God, I have a strong daughter here. If not, I don’t know what to do. That’s why every day, morning, I wake up, I pray to God … my daughter [will] always [be] strong.. and can go through and face this kind of treatment. That’s what I always pray for.. she [will] always [be], every day, healthy, strong. – C13 Caregiver coping strategies/Faith based beliefs and practices Find out who’s the next best caregiver at hand. You have to ask them to take turns, take time off and relax. Some, especially mothers, it’s very difficult to say this to them. When we tell them to take time off, they find that it’s very non-virtuous. They find it sinful in fact, to leave their child in that condition to take a break. – HCP06Respite care |

Interaction with the healthcare system

In their interaction with the healthcare system, parents needed information regarding the disease, treatment, and how to navigate the healthcare system. These are essential information that are normally provided by healthcare providers when the diagnosis of cancer is made. Information regarding the disease and treatment are essential for the decision-making process about treatment.

“Yes, the doctor gave us details. Gave details, told us about it, and we asked a lot of questions about what is acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), how leukemia happens, what causes it.” – C04, father of a boy with ALL .

Parents often sought this information from other sources when they found it difficult to understand or needed more details.

“So like I am still searching for what is leukemia. So I ask mothers of other patients.” – C02, mother of a girl with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Health system navigation refers to information on how parents can access the health system effectively and reduce barriers to healthcare services. Categories in this theme included access to supportive care services, a contact point for emergencies, familiarizing with the hospital setting, follow up and monitoring, obtaining medications and suitable equipment. Parents reported that the healthcare professionals were instrumental in letting them know about the availability of these services.

“The doctors advised me. Since I didn't have a car, no transport. It’s better that you stay here [at the transit home]. So I stayed. If not, I wouldn’t know [this was available].” – C05, mother ofa girl with ALL (transit accommodations).

Finally, it is important to help parents to understand the roles of different healthcare professionals in the care of their child. Parents may face difficulties obtaining the support they need if they do not approach the right healthcare professional for help. Parents also had to understand the limitations of services so that they can make the right judgment on where to seek help for their child.

“It would be very helpful if they can explain what is the difference between the PC [palliative care] team in the hospital and the PC team in the community. What are the limitations the community team may face …” – HCP06, community palliative care doctor .

Care for the child at home

This was an important theme that encompassed the parents’ caregiving tasks for the child who was diagnosed with cancer. Information related to this theme was necessary for parents to support them in performing relevant caregiving tasks and observing the necessary precautions, particularly when their child has been discharged home. Often the process of learning and caregiver training began while their child was still in the ward. Parents had to achieve a minimum acceptable level of competence before their child could be discharged home safely.

“Before going home.. need to learn how to clean it [central venous line]. If we don't pass that, cannot go home. Once we pass, then we can go home.” – C07, mother ofa girl with neuroblastoma .

The scope of caregiving includes caregiving for basic activities of daily living, medical caregiving, and psychosocial caregiving. Most parents were already providing caregiving for basic activities of daily living but needed to tailor it to the child’s diagnosis of cancer. This was more evident when the disease has resulted in the child’s dependence on these activities, such as when the child has neurological impairment due to the cancer or complications of treatment. Parents frequently wanted to know what food their child could take as it is part of their main responsibilities as a parent.

“I searched for food for cancer patients sometimes.. I searched for ‘ALL’, the type of cell, and fruits. Like strawberries or other berries, can they take it.. I check for that in websites.” – C05, mother of a girl with ALL.

Parents had to adapt and learn medical caregiving almost immediately upon diagnosis. They had to know how to manage medications, prevent infections, and perform tube care and other home nursing activities, or manage symptoms at home. Of particular importance was the need to recognize situations that warrant emergency or urgent medical care for their child. This would ensure that appropriate medical care is sought without delay.

“The doctor did tell me, if you feel your child seems ‘off’, like too tired, you see, if you see that she is very pale, or unwell, call first, call the ward and inform. Consult the doctor.” – C05, mother of a girl with ALL .

Being a good parent for a sick child is extremely challenging. Parenting a sick child involves the provision of psychosocial support for the child, besides meeting the child’s physical needs. This theme included learning how to talk to the child about their sickness, treatment, and difficult topics such as death. It also involved how parents could support their child emotionally and manage potential behavioral issues, which may be related to the disease process or treatment. Schooling and education, as well as maintaining their child’s social health, was also part of psychosocial caregiving.

“I told her [my daughter], she needs to be patient, it's the effect of chemotherapy, you will lose your hair, no appetite. If you don't feel like eating a lot, you still have to eat a little. Your hair will drop. They will grow back.” – C07, mother of a girl with neuroblastoma.

Psychosocial support for parents

Psychosocial support refers to the provision of support to meet the psychological and social needs of the parents. Parents had to fulfill other roles and demands in life besides providing care for their child. This included their responsibilities to other children, family members, work, and their social circle. Information on how to obtain practical support needs are needed to assist parents in balancing these other responsibilities with caregiving for their sick child. This may include childcare for siblings, financial aid for medical and living costs, arrangements for leave from work, and temporary accommodations for those staying far from the treatment centers.

“Some of them have financial difficulties. They need to consider who will help to take care of their other children, who will work to earn income.” – HCP05, postgraduate pediatric trainee doctor .

Parents would also benefit from information about self-care, which encompassed possible coping strategies when faced with stress, how to maintain their own physical health, and to arrange for respite care. This information would help parents to keep their family and themselves intact throughout their journey of childhood cancer. A few parents mentioned the importance of being strong for their sick child.

“The strength is within us. Because if we stay negative, we will just cry. When we cry, our child is already big, she understands why we are crying. She will ask, and she will become [emotionally] down. We don't want that.” – C07, mother of a girl with neuroblastoma .

Among the various coping strategies for self-care, faith-based beliefs and practices were frequently mentioned by parents.

“Whatever it is now, we can only pray. We can only pray to Allah. For that is all we can do.. Because he allowed this sickness, he is able to cure it. That's all.” – C08, mother ofa boy with osteosarcoma .

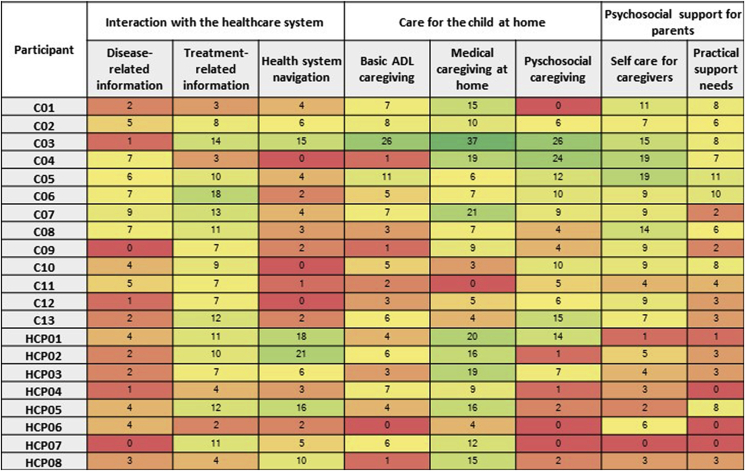

Distribution of subthemes across participants

The distribution of codes for various subthemes across participants is displayed in Figure 2. Codes are basic units of qualitative data. They are not uniform in terms of spread. Figure 2 shows that both parents and healthcare providers talked equally about treatment-related information and medical caregiving for the child. However, codes related to health system navigation were mentioned more frequently by healthcare providers and less by parents. Conversely, information related to psychosocial issues, including psychosocial caregiving for the child and psychosocial support for the parents, were more frequently mentioned by the parents and less by the healthcare providers. This provides evidence of data triangulation and that the two categories of participants had slightly different priorities regarding parents’ information needs.

Figure 2.

Distribution of codes across participants.

Discussion

The findings of this study reveal that parents’ information needs can be mapped to the main areas of their roles as caregivers for their children, which were their direct contact with the healthcare system, various forms of caregiving for their child at home and psychosocial support that enabled them to provide care for their child. These information needs also reflect their supportive care needs for their child’s cancer journey. Healthcare providers and parents had some differences in prioritizing information needs. In general, healthcare providers mentioned information needs related to treatment, navigation of healthcare system, and medical caregiving for the child. Parents expressed information needs across the three main themes related to their roles that included other aspects of psychosocial care for their child and self-care.

The information needs of parents in Malaysia were similar to what has been reported in prior literature.26 Disease-related and treatment-related information are needed for decision-making regarding their child’s treatment.27,28 However, these information should be communicated in easily-understood terms and with empathy for parents’ emotional distress.10,29 It is also important for healthcare providers to be able to maintain parents’ hope while communicating information with honesty and transparency.18 The way information is communicated, is therefore, essential to meeting the parents’ needs. If these information needs are not adequately addressed, parents will seek information from other sources such as from other parents. While peer support can be a valuable source of information, caution is needed to ensure that only accurate information is provided. Misinformation or sharing of unproven therapies may result in potential problems such as chemo–drug interactions.30 Communication training for healthcare providers is therefore important to enable effective information support for parents. Culturally appropriate educational materials in the local languages are needed to facilitate understanding by local parents.31

Navigation of the healthcare system is focused on enabling access to healthcare services.32 However, navigation in cancer care is often discussed and studied in the context of poor and under-served populations.20,33 The current study findings suggest that participating parents had low awareness of how the healthcare system works in their child’s cancer care and the availability of supportive services. Most of the quotes for this theme came from the healthcare providers, who were more aware of the various services that parents may need and the overall picture of how healthcare is to be provided for the child. Recognizing the roles of different healthcare providers may also enable parents to seek out the right person for advice or information.34 A compilation of available resources according to locations would thus be helpful to support both healthcare providers and parents. Parents should also be introduced to the various healthcare professionals in the team and their roles. Compiling resources according to locations could highlight gaps in the availability of resources, particularly community-based resources such as pediatric home nursing. This should be seen as an opportunity for service development in specific communities or locations.

Care for the child at home is a broad theme, which encompassed many caregiving tasks that parents must perform at home. Parental training on medical caregiving is standard care for children with cancer.26 All parents were given core medical caregiving information, especially on recognizing emergency situations, infection prevention, medication management, and tube care.26 Parents in this study were able to give examples of such information, demonstrating that they have understood it well. Parents may also use the knowledge to teach their children self-care. This could be beneficial to empower children in general.35

Other aspects of caregiving such as nutrition and caregiver support were considered secondary or tertiary topics in guidelines for cancer parent education.26 Most parents in this study talked about wanting to know what kind of food can or cannot be given to their child, despite guidelines ranking diet as a secondary topic. Again, when information is not sufficient, parents may turn to the web for more information. Its importance may be related to the fact that preparing food for their child is a core caregiving task that was most frequently performed by parents. Food also has a culturally important meaning as Asian parents believe that it plays an important role in helping the child fight the illness.36 Certain food may contribute to healing and restoration in local cultural belief.30 Hence, healthcare providers would need to be prepared to deal with parents’ questions pertaining to diet for children with cancer. Discussions on appropriate food for the child should not be limited to the calorie and nutrition requirements but also on how to build up the child’s capacity to recover and tips on how to manage their eating behavior. Dietary advice should consider parents’ cultural beliefs. Dietitians can provide invaluable support to meet this information need.

The subtheme of psychosocial caregiving shows that parents may benefit from guidance on parenting a sick child. Parents typically aim to become good parents to their children. When their child is sick, their role as parents would include being the decision-maker, companion, comforter, advocate, and protector.4,37 However, when their child is suffering from cancer, the parents often face the dilemma of having to provide care that is distressing to their child but simultaneously comforting them.4,38 Optimal parenting in the context of children with cancer can be confusing as parents struggle with overprotection or permissiveness, use of discipline and concern for the child’s stress levels.39 This aspect should be explored further in future research. Parents may benefit from understanding the emotional needs of their child who is facing cancer and the treatment process. Empowering parents to provide appropriate psychosocial support for their child could contribute to a better quality of life for the child in the longer term.40

To provide care for others, one must first take care of oneself. This was reflected by the final theme, where parents needed information on psychosocial support for themselves. While parents care for the child with cancer, they are not freed from other demands and responsibilities for other members of the family and their jobs.38 Being a caregiver for their sick child placed additional stress on these other responsibilities. Parents may need to negotiate for support from others, such as their extended family or employers. They also had to secure additional resources to support the process of caregiving during their child’s treatment. A family conference may be useful to facilitate problem-solving and identify sources of support from their social network. It is also important to highlight self-care for parents, as many tend to neglect themselves as they addressed the intense caregiving needs of their child.38 One of the healthcare providers who was interviewed highlighted the need to purposefully introduce the concept of respite care for parents who are facing excessive caregiving burdens (Table 3). The concept of self-care need to be emphasized to improve parents’ ability and self-efficacy for coping, as this will contribute toward their own health and well-being.41

Parents in this study also reported using religious practices, acceptance, and planning as one of their coping strategies.42,43 They shared about the role of their faith in God and how this belief helped them to accept the situation. Their faith also provided them with hope that things will be better. While faith-based practices are part of their repertoire of coping strategies, it may not be an explicit information need. Parents may seek guidance from their respective spiritual leaders rather than from healthcare providers. However, healthcare professionals need to be aware of religious concepts that shape the parents’ understanding of the meaning of their child’s illness. This is an important cultural aspect in a multi-ethnic population in Malaysia. Spiritual care training for healthcare providers may be useful for psychosocial support in general.44

There were differences between parents’ and healthcare providers’ priorities for the information needs. As mentioned above, healthcare providers were more familiar with how the healthcare system works and would be better positioned to recommend supportive services. Themes regarding psychosocial information needs were more frequently mentioned by parents compared to healthcare providers. This suggests a need for healthcare providers to provide more informational support for psychosocial issues, as recommended in international standards for psychosocial care.12 Examples of such information may include how parents can support the child emotionally, guiding parents in problem-solving to obtain the practical support needed to facilitate the child’s treatment and maintain the integrity of their family.45 Parents also benefit from interventions that can help them cope with the stress of the situation. Development of psychosocial interventions for Malaysian parents would be invaluable to support them through their child’s cancer journey.12

This study did not intend to use qualitative content analysis. However, the frequencies of codes mentioned by parents and healthcare providers do suggest that healthcare providers and parents talk about different issues. Codes for almost every theme were found in the interviews of all study participants, demonstrating thematic saturation. However, the codes are uneven in terms of spread and are not fully representative of the perceived importance of the themes to each participant. The purposive sampling method for qualitative research also makes this not generalizable to all pediatric cancer parents. Therefore, the differences in priorities for information needs should be confirmed by future quantitative studies on a representative sample.

Much focus is given to meeting the information needs related to the parents’ interaction with the healthcare system and medical caregiving. There is no doubt that at the initial phase of diagnosis, the needs for disease and treatment-related information are crucial for decision-making. Multidisciplinary care coordination and preparing parents for medical caregiving is also an early priority. However, the other information needs are also important in preparing parents for their role as caregivers. Parents may rely on guidance from “experienced parents”’ through formal or informal parent support groups, or in the Malaysian context, their extended social support network consisting of family members, friends, and community. It may be worthwhile to develop peer-reviewed and validated resources to meet these information needs as part of standard psychosocial support for parents of children with cancer. These resources will be of value for both healthcare providers who provide care for the child, as well as parents themselves.

The information needs of parents in this study appears to have some similarities to Clark’s conceptual model on self-management of chronic disease among older adults.46 Similarities include care for the child at home, such as symptom management, medication management, and nutritional needs. Other similarities include the psychosocial needs of dealing with the emotions related to the illness, communication with healthcare providers, seeking information, and adapting to life. However, in this study, parents are caregivers for their child, not managing their own illnesses. Their informational needs are related to their child’s medical and psychosocial needs, as well as their own needs. Therefore, the findings of this qualitative study represent caregivers’ informational needs in the context of childhood cancer, which is slightly different from the self-management model for older adults. The informational needs of these parents encompass not only medical information but information to support them to be able to confidently self-manage their child at home.

Provision of informational support can be strengthened by allocating specific staff to provide psychosocial support. Most pediatric oncology centers in Malaysia do not yet have specialized pediatric oncology nurses who can play an important role in coordinating psychosocial support and providing necessary informational support for parents.47 Even psychologists and counselor services are shared with various other pediatric disciplines. As such, the provision of psychosocial support for parents of children with cancer can be further strengthened by training specific staff for psychosocial care. Engaging parent support groups can also assist in meeting the needs of psychosocial care when healthcare resources are limited.

Strengths and limitations

This was the first qualitative study on information needs among pediatric cancer parents in Malaysia. Care was taken to ensure the credibility and trustworthiness of the study. This study included both parents of children with cancer and healthcare providers to provide data triangulation, giving an all-rounded view of parents’ information needs. Parents of children with different diagnosis categories (hematological cancers and solid tumors), at different phases of the cancer trajectory were interviewed, thus providing a broad variety of information needs. Healthcare providers from a variety of settings, both hospital and community-based, and from different professions, were also included in this study. While the findings cannot be generalized due to the qualitative study design, it provided the breadth of information needs of the parents from different angles. Other measures to ensure the study’s trustworthiness included ensuring researcher reflexivity through reflexive memos and peer checking. This study was limited by the recruitment of participants from the two centers and non-governmental organizations in the same city in central Malaysia. More studies are needed to explore whether the information needs of parents from other regions in Malaysia are different. The distribution of codes across participants should be interpreted with caution as codes are different in terms of spread and would not be representative of the overall importance of themes to the general population of parents.

Conclusions

In conclusion, Malaysian parents of children with cancer have a wide scope of information needs that are closely related to their role as caregiver and their supportive care needs. The findings of this study suggest the need to improve the provision of informational support by healthcare providers, particularly for psychosocial information needs. Educational resources to support parents’ information needs are required to facilitate the provision of information to parents. They will be invaluable for assisting parents in dealing with the various challenges in caregiving for a sick child. Future research to develop evidence-based resources for information support is therefore needed. These resources should also be developed to suit the local sociocultural and healthcare system context.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Author contribution statement

CET, ZAL, and SMS conceptualized the study and designed the methodology. CET collected and analyzed the data. SCDL, CCL, and KHT provided resources for the study. All authors provided peer review for the codes. CET wrote the original draft. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

All authors declare that the manuscript represents honest work. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Director General of Health, Malaysia, for permission to publish this study.

Declaration of competing interest

None declared.

Funding

This work was funded by the Universiti Kebangsaaan Malaysia Medical Faculty Fundamental Grant (GFFP) (Grant No. FF-2020-396).

References

- 1.Force L.M., Abdollahpour I., Advani S.M., Agius D., Ahmadian E., Alahdab F., et al. The global burden of childhood and adolescent cancer in 2017: an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Sep;20(9):1211–1225. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30339-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhakta N., Force L.M., Allemani C., Atun R., Bray F., Coleman M.P., et al. Childhood cancer burden: a review of global estimates. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(1):e42–53. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30761-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azizah A., Hashimah B., Nirmal K., Siti Zubaidah A., Puteri N., Nabihah A., et al. Ministry of Health Malaysia; Putrajaya: 2019. Malaysia National Cancer Registry Report (MNCR) 2012-2016; pp. 1–116. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones B.L. The challenge of quality care for family caregivers in pediatric cancer care. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2012;28(4):213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kowalczyk J.R., Samardakiewicz M., Fitzgerald E., Essiaf S., Ladenstein R., Vassal G., et al. Towards reducing inequalities: European standards of care for children with cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(3):481–485. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weaver M.S., Heinze K.E., Bell C.J., Wiener L., Garee A.M., Kelly K.P., et al. Establishing psychosocial palliative care standards for children and adolescents with cancer and their families: an integrative review. Palliat Med. 2016 Mar 28;30(3):212–223. doi: 10.1177/0269216315583446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kearney J.A., Salley C.G., Muriel A.C. Standards of psychosocial care for parents of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015 Dec;62(S5):S632–S683. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitch M.I. Supportive care framework. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2008;18(1):6–14. doi: 10.5737/1181912x181614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerr L.M.J., Harrison M.B., Medves J., Tranmer J. Supportive care needs of parents of children with cancer: transition from diagnosis to treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004 Nov 1;31(6):E116–E126. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.E116-E126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maree J.E., Parker S., Kaplan L., Oosthuizen J. The information needs of South African parents of children with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2016 Jan 2;33(1):9–17. doi: 10.1177/1043454214563757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koohkan E., Yousofian S., Rajabi G., Zare-Farashbandi F. Health information needs of families at childhood cancer: a qualitative study. J Educ Health Promot. 2019;8(5):246. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_300_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiener L., Kazak A.E., Noll R.B., Patenaude A.F., Kupst M.J. Standards for the psychosocial care of children with cancer and their families: an introduction to the special issue. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015 Dec;62(S5):S419–S424. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granek L., Rosenberg-Yunger Z.R.S., Dix D., Klaassen R.J., Sung L., Cairney J., et al. Caregiving, single parents and cumulative stresses when caring for a child with cancer. Child Care Health Dev. 2014 Mar;40(2):184–194. doi: 10.1111/cch.12008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mouw M.S., Wertman E.A., Barrington C., Earp J.A.L. Care transitions in childhood cancer survivorship: providers' perspectives. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017 Mar;6(1):111–119. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2016.0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kästel A., Enskär K., Björk O. Parents' views on information in childhood cancer care. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(4):290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sulkers E., Tissing W.J.E., Brinksma A., Roodbol P.F., Kamps W.A., Stewart R.E., et al. Providing care to a child with cancer: a longitudinal study on the course, predictors, and impact of caregiving stress during the first year after diagnosis. Psycho Oncol. 2015 Mar;24(3):318–324. doi: 10.1002/pon.3652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine (US), National Research Council (US), National cancer policy board . In: Childhood Cancer Survivorship: Improving Care and Quality of Life. Hewitt M., Weiner S.L., Simone J.V., editors. National Academies Press (US); Washington DC: 2003. 2003. The trajectory of childhood cancer care.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK221739/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coyne I., Amory A., Gibson F., Kiernan G. Information-sharing between healthcare professionals, parents and children with cancer: more than a matter of information exchange. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2016;25(1):141–156. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koch K., Jones B. Supporting parent caregivers of children with life-limiting illness. Children. 2018 Jun 26;5(7):85. doi: 10.3390/children5070085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun K.L., Kagawa-Singer M., Holden A.E.C., Burhansstipanov L., Tran J.H., Seals B.F., et al. Cancer patient navigator tasks across the cancer care continuum. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012 Feb;23(1):398–413. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charmaz K. In: The SAGE Handbook of Social Research Methods. 1 Oliver's Yard, 55 City Road. Alasuutari P., Bickman L., Brannen J., editors. SAGE Publications Ltd; London EC1Y 1SP United Kingdom: 2008. Reconstructing grounded theory; pp. 461–478. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly M. The role of theory in qualitative health research. Fam Pract. 2009;27(3):285–290. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmp077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins C.S., Stockton C.M. The central role of theory in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2018;17(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saldana J. 3rd ed. SAGE Publications Ltd; London: 2016. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; pp. 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creswell J.W. 3rd ed. Sage Publications; Los Angeles: 2013. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; pp. 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodgers C., Bertini V., Conway M.A., Crosty A., Filice A., Herring R.A., et al. A standardized education checklist for parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer: a report from the children's oncology group. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2018;35(4):235–246. doi: 10.1177/1043454218764889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Markward M.J., Benner K., Freese R. Perspectives of parents on making decisions about the care and treatment of a child with cancer: a review of literature. Fam Syst Health. 2013 Dec;31(4):406–413. doi: 10.1037/a0034440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kilicarslan-Toruner E., Akgun-Citak E. Information-seeking behaviours and decision-making process of parents of children with cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013 Apr;17(2):176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yiu J.M.-C., Twinn S. Determining the needs of Chinese parents during the hospitalization of their child diagnosed with cancer: an exploratory study. Cancer Nurs. 2001 Dec;24(6):483–489. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200112000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamidah A., Rustam Z.A., Tamil A.M., Zarina L.A., Zulkifli Z.S., Jamal R. Prevalence and parental perceptions of complementary and alternative medicine use by children with cancer in a multi-ethnic Southeast Asian population. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009 Jan;52(1):70–74. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gray W.N., Szulczewski L.J., Regan S.M.P., Williams J.A., Pai A.L.H. Cultural influences in pediatric cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2014 Sep 10;31(5):252–271. doi: 10.1177/1043454214529022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryvicker M. A conceptual framework for examining healthcare access and navigation: a behavioral-ecological perspective. Soc Theor Health. 2018;16(3):224–240. doi: 10.1057/s41285-017-0053-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whop L.J., Valery P.C., Beesley V.L., Moore S.P., Lokuge K., Jacka C., et al. Navigating the cancer journey: a review of patient navigator programs for Indigenous cancer patients. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2012;8(4):89–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-7563.2012.01532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaziunas E., Hanauer D.A., Ackerman M.S., Choi S.W. Identifying unmet informational needs in the inpatient setting to increase patient and caregiver engagement in the context of pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2016 Jan;23(1):94–104. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chong D.L.S., Azim E., Latiff Z., Zakaria S.Z.S., Wong S.W., Wu L.L., et al. Transition care readiness among patients in a tertiary paediatric department. Med J Malaysia. 2018;73(6):382–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong M.Y.F., Chan S.W.C. The qualitative experience of Chinese parents with children diagnosed of cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15(6):710–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palmer S.J. Care of sick children by parents: a meaningful role. J Adv Nurs. 1993;18(2):185–191. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18020185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woodgate R.L., Edwards M., Ripat J.D., Borton B., Rempel G. Intense parenting: a qualitative study detailing the experiences of parenting children with complex care needs. BMC Pediatr. 2015 Dec 26;15(1):197. doi: 10.1186/s12887-015-0514-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim M.A., Yi J., Wilford A., Kim S.H. Parenting changes of mothers of a child with cancer. J Fam Issues. 2020;41(4):460–482. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamidah A., Wong C.-Y., Tamil A.M., Zarina L.A., Zulkifli Z.S., Jamal R. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among pediatric leukemia patients in Malaysia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011 Jul 15;57(1):105–109. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klassen A., Raina P., Reineking S., Dix D., Pritchard S., O'Donnell M. Developing a literature base to understand the caregiving experience of parents of children with cancer: a systematic review of factors related to parental health and well-being. Support Care Cancer. 2007 Jun 18;15(7):807–818. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sutan R., Al-Saidi N.A., Latiff Z.A., Ibrahim H.M. Coping strategies among parents of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Health (Irvine Calif) 2017;9(7):987–999. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zarina A., Radhiyah R., Hamidah A., Syed Zulkifli S., Rahman J. Parenting stress in childhood leukaemia. Med Health. 2011;7(2):73–83. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paal P., Helo Y., Frick E. Spiritual care training provided to healthcare professionals: a systematic review. J Pastor Care Couns. 2015 Mar 21;69(1):19–30. doi: 10.1177/1542305015572955. Adv theory Prof Pract through Sch reflective Publ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hildenbrand A.K., Clawson K.J., Alderfer M.A., Marsac M.L. Coping with pediatric cancer: strategies employed by children and their parents to manage cancer-related stressors during treatment. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2011 Nov 22;28(6):344–354. doi: 10.1177/1043454211430823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clark N.M., Becker M.H., Janz N.K., Lorig K., Rakowski W., Anderson L. Self-management of chronic disease by older adults. J Aging Health. 1991 Feb;3(1):3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hollis R. The role of the specialist nurse in paediatric oncology in the United Kingdom. Eur J Cancer. 2005 Aug;41(12):1758–1764. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.