Abstract

Childhood developmental-behavioural issues and disabilities have been identified as the major challenges in child health and to the national healthcare system in Singapore. Dealing with these morbidities requires new and innovative approaches that go far beyond hospital-based care into the community, with structured integration of medical services with education, and social and community support, including a strong collaborative partnership with parents and caregivers. A unique child development programme has evolved in Singapore over the last 30 years. Its main objectives are early identification and treatment of children with developmental and behavioural problems so as to correct developmental dysfunctions, minimise the impact of a child’s disability or prevailing risk factors, strengthen families and establish the foundations for subsequent development. This paper aimed to provide an update of the current ecosystem, along with a review of the fast-changing landscape in recent years.

Keywords: childhood disabilities, developmental-behavioural paediatrics, early childhood developmental intervention

INTRODUCTION

The early years of a child are a period of considerable opportunity for growth as well as vulnerability of harm. Decades of scientific research have concluded that experiences in the first few years establish a foundation for human development that is carried throughout life.(1) Early childhood intervention can shift the odds towards more favourable outcomes in child health and development, educational attainment and economic well-being, especially for children at risk.

A child development programme has evolved in Singapore over the last 30 years.(2,3) It is a unique nationwide ecosystem, which is inclusive, multidisciplinary, community-based, family-focused and child-centric, with structured integration of medical services with education, and social and community support, including strong collaborative involvement of parents and caregivers. The landscape is fast-changing in recent years, as the government has committed to investing in our children at an early age. Significant progress has been made in the various components of the evolving ecosystem.(2,3)

DEVELOPMENTAL SURVEILLANCE AND SCREENING

Both developmental surveillance and screening are important for early identification and provision of timely intervention to children with special developmental needs. The Second Enabling Masterplan (2012–2016)(4) of the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) recommended strengthening the national developmental surveillance and screening system by establishing a network of early detection touch points in the community, comprising primary healthcare professionals, child care centres, pre-schools and family service centres. The Masterplan also proposed that the Child Health Booklet be used as the main tool for routine developmental surveillance. Every child born in Singapore has a copy of the standardised Health Booklet. The Booklet contains developmental checklists at certain important and sensitive touch points of children, based on our validated Denver Developmental Screening Test, Singapore.(5,6) In the last revision of the Health Booklets, screening items that target early detection of autism have been incorporated in the checklists. In future revision, more touch points for children between the age of two and three years will also be included.

However, developmental screening should not be the sole responsibility of healthcare professionals. The aim is to encourage and empower the parents and caregivers at home to play a central role in monitoring the child’s health and development. The information on developmental milestones of a child will also serve as anticipatory guidance for parents and caregivers. This method of developmental surveillance has been extended to involve pre-school educators who will be the caretakers of children once they are in playgroups, nurseries or kindergartens.

An important challenge for developmental surveillance is that children and families with the highest level of possibility of developmental problems are sometimes the least likely to avail the services. Many upstream projects have attempted to identify children and families at risk. The most recent nationwide initiative is the KidSTART programme launched by MSF in 2016 and currently led by the Early Childhood Development Agency (ECDA).

COMPREHENSIVE DEVELOPMENTAL ASSESSMENT

A seamless and hassle-free referral system has been established. The majority of children would come through the polyclinics to the two main assessment centres: Department of Child Development, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH) and Child Development Unit, National University Hospital (NUH), both under the Child Development Programme of the Ministry of Health, Singapore.

The purpose of a comprehensive developmental assessment is to accurately determine a child’s developmental status in a number of domains: physical (including vision/hearing and gross and fine motor development), cognition, communication, social-emotional and adaptive. The assessment would attempt to determine the cause(s) of the delay in development. A multidisciplinary team coordinated by a trained paediatrician as the case manager is required to obtain a thorough understanding of the child’s unique abilities, namely his weaknesses, strengths, attainment levels and needs. Every assessment should also identify the family’s concerns, priorities and resources. Concerns are what family members identify as needs, issues or problems that they want addressed. Priorities allow family members to set their own agenda and makes choices about the involvement of subsequent early intervention in their life. Resources include finances, strengths, abilities and supports that can be mobilised to meet the family’s concerns, needs and desired outcomes. Identifying these issues aids the development of early intervention outcomes, strategies and activities that will help families achieve their goals.

PATTERN OF DEVELOPMENTAL PROBLEMS IN PRE-SCHOOLERS

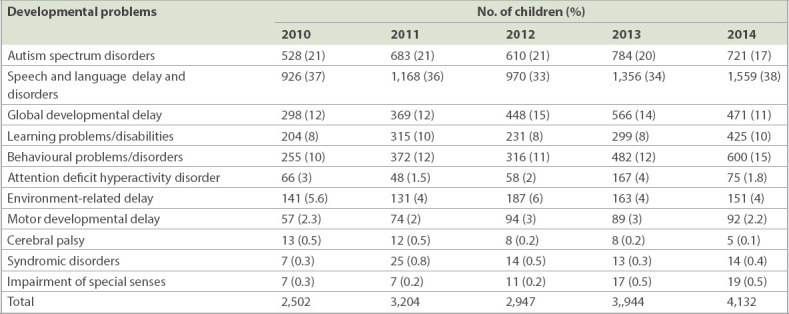

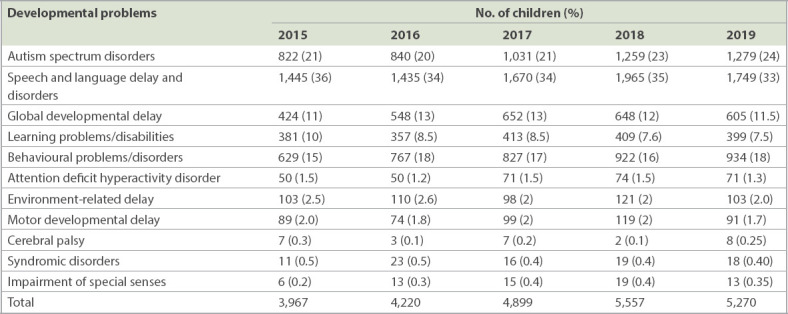

Table I shows the pattern of developmental problems in pre-schoolers seen under the Child Development Programme (both KKH and NUH) from 2010 to 2014. Table II shows the pattern of developmental problems in pre-schoolers from 2015 to 2019.

Table I.

Pattern of developmental problems in pre-schoolers (2010–2014).

Table II.

Pattern of developmental problems in pre-schoolers (2015–2019).

‘Pre-schoolers’ include children aged between 0 and 7 years who have not yet been enrolled into either mainstream schools or special schools in Singapore. The numbers only represent the developmental ‘problems’ seen in these children. A proportion of children with varying needs may require early intervention in the pre-school years and must not be considered as having disabilities.

A fairly consistent pattern of developmental problems can be observed in pre-schoolers. Autism spectrum disorders (ASD), and speech and language delay and disorders together accounted for 53%–58% of the developmental problems. Learning problems/disabilities and attention deficit hyperactivity disorders (ADHD) had not surfaced as major issues in this age range (< 10%). We anticipate that these two problems will emerge to dominate the developmental problems once the children enter primary schools and start to face different academic challenges and demands. Developmental delay, environment-related delay and other behavioural issues accounted for about 30% of the concerns.

Improved perinatal care and expanded nationwide neonatal screening programmes over the past five decades have considerably reduced the number of infants and children born with congenital malformations and those who may sustain significant brain damage during pregnancy or during the peripartum and postnatal periods. This is reflected in the fewer number of cases of cerebral palsy, syndromic disorders (such as Down syndrome) and impairment of special senses (visual and hearing impairment). About 30% of the children with developmental problems were seen before the age of three years and 50%, before they completed four years.

INDIVIDUALISED INTERVENTION PLAN

Development of the individualised management and education plan is based on the information gathered through the assessment of the child and family, directed by the family’s concerns, priorities and resources in collaboration with the early intervention team. Any eventual intervention plan would involve the parents as the focal point; hence, their participation in the entire process is of paramount importance. Health services alone will be insufficient in this regard, and strong working relationships and partnerships with social services in the community as well as with schools are warranted. A follow-up evaluation system is in place to monitor the progress of the child and the family so that the management plan can be regularly reviewed and updated through documentation of the adjustments and achievements.

In the child’s journey beyond early childhood, the case manager, who is usually the primary care paediatrician, will continue to monitor the progress of the child, support the family and play the important role of advocacy until the child reaches adulthood.

EARLY CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENTAL INTERVENTION

There is growing evidence that early intervention (EI) can have a substantial impact on children with developmental needs and their families.(1) The goals and outcomes of EI would be to promote development in all important domains; promote child engagement, independence and mastery; build and support social competence; facilitate the generalised use of skills; support families in achieving their own goals; prepare and assist children with normalised life experiences in their families, schools and communities; help children and families make smooth transitions; and prevent or minimise the development of future problems or disabilities.

The five key principles in the design of our current approach to EI are: shifting the decision-making power on caring for the child from the professional to the family (family-centred); shifting diagnosis-based intervention to one that is based on the developmental needs of the individual child; shifting emphasis of intervention from disability to functional and developmental performance, participation and quality of life; shifting the settings of service and care delivery to a less restrictive, more natural and inclusive environment (e.g. childcare centres, pre-schools and schools, homes and the community); and shifting from a multidisciplinary to a transdisciplinary team practice.

The development of children varies considerably owing to a combination of biological and environmental factors. During pre-school years, some children display a level of developmental functioning that is below the functioning of their typically developing peers of the same age. The developmental conditions can range from physical issues, sensory issues, cognitive and learning issues, to behavioural and emotional problems. These children require varying levels of EI support entailing different and/or additional resources beyond what is conventionally available for their typically developing peers.

As the developmental trajectory of these children is still fluid, it may not be possible or desirable to make a confirmatory diagnosis of a specific disability condition. These children are more appropriately classified as children with developmental needs (DN). Among children with DN, some children, even during pre-school years, display functional impairments and disability conditions that can be clearly identified and would likely require specialised targeted provisions and support beyond pre-schools, either in mainstream schools or special education (SPED) schools. This subset of children with DN can be categorised as having special educational needs (SEN). The categorisation of children as having DN or SEN is not static and can change over time in children with DN during the pre-school years. Therefore, professionals should be mindful when discussing with parents about the longer-term educational needs and placement of their children, so that the parents can make informed decisions. Currently, over 80% of children with SEN are supported in mainstream schools, and the remaining 20% in SPED schools,(7) owing to the children’s response to EI and/or maturational factors.

EARLY INTERVENTION AT KKH AND NUH

Each of the five community-based intervention centres of KKH and NUH consists of a multidisciplinary team of allied health professionals (AHPs) (occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, educational therapy professionals, educational psychologists), social workers and nurse practitioners. They serve the important role of providing EI at the tertiary level after the comprehensive assessment. Parents would go through the ‘Signposts for Building Better Behaviour Programme’ to assist them in understanding their children and to acquire skills and techniques in managing some of the difficult behavioural issues of their children. Children with mild developmental problems can be discharged after a short period of intervention. For children with more complex issues and those who are likely to require a longer period of intervention, the centres will continue appropriate interim intervention in partnership with the parents until they are enrolled in the Early Intervention Programme for Infants and Children (EIPIC) centres. ‘SG Enable’ is the central coordinating body for arranging the children’s placement at the EIPIC centres nearest to their respective homes.

EARLY INTERVENTION PROGRAMME FOR INFANTS AND CHILDREN

The government-funded EIPIC@Centres provide EI support to children aged two to six years with moderate to severe DN and SEN. In each EIPIC centre, the AHPs, social workers and related EI professionals adopt a transdisciplinary approach, in partnership with the families, to design and deliver individualised educational plans and goals. As of 2021, there are 21 EIPIC centres located across Singapore. They are run by the following Social Service Agencies (SSAs), which are non-profit voluntary welfare organisations (in alphabetical order): Autism Association (Singapore) Eden Children Centre; Autism Resource Centre, Singapore; Asian Women’s Welfare Association; Canossian School; Cerebral Palsy Alliance, Singapore; Fei Yue Community Service; Metta Welfare Association; Rainbow Centre; SPD (former Society for the Physically Disabled); and Thye Hua Kwan Moral Charities.

Since July 2019, the EIPIC Under-2s programme has been rolled out progressively to serve children aged below two years who require medium to severe levels of EI support. The programme emphasises on imparting skills to the parents/caregivers and would require them to accompany the children. Home-based EI can be provided for a selected group of children who have medical or high-risk family factors that make their participation at EI centres difficult.

FROM ‘MISSION: I’MPOSSIBLE’ TO DEVELOPMENT SUPPORT PROGRAMMES

In 2006, the then KKH SengKang EI centre initiated a ‘Therapy Outreach Programme’ to the neighbouring pre-schools, which was a success. In 2009, with funding support from Lien Foundation, the programme was further expanded to more pre-schools in the region, and the project was renamed ‘Mission I’mPossible’ (MIP).(8,9) The MIP was completed in 2012. The MSF then decided to develop the MIP as the ‘Development Support Programme’ (DSP).

The DSP was officially launched by the MSF in May 2013 to provide learning support and therapy intervention to children with mild DN. Under this programme, a group of professionally qualified early childhood educators known as Learning Support Educators are deployed to work closely with teachers and parents. They play the key role of conducting screening to assist in understanding the child’s developmental needs; providing in-class support to embed and generalise therapy goals back into the classroom after individual intervention with the therapists; providing targeted support in social skills, literacy, language and handwriting; and providing advice and support to classroom teachers and parents. AHPs and EI professionals from various EIPIC centres play a complementary role by providing appropriate therapy intervention to children who require greater support.

DSP was renamed the ‘Development Support and Learning Support (DS-LS) programme’ in 2017 to better reflect the therapy-based (i.e. DS) and psycho-educational (i.e. LS) aspects of the programme. The DS-LS programme should operate in a continuum with EIPIC, with varying intensities of interventions, to maximise the available resources. The Development Support-Plus (DS-Plus) programme is introduced for children who have made sufficient progress under the EIPIC@Centre programme, to help their transition to a pre-school setting. These children have generally progressed to require low levels of EI support.

All the EI programmes must work towards seamless integration with the regional pre-schools and be complementary to one another in the care and education of children. To ensure that EI services are affordable, the MSF has enhanced EI subsidies and broadened the income criteria for means-tested subsidies so that more families can qualify, and the out-of-pocket expenses are lowered for most income groups.

RIDING ON THE WAVES OF EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION

Pre-school education has now been placed right at the start of a child’s education journey in Singapore. Pre-schools are the seeding fields of an inclusive, fair and just society. Early pre-school exposure allows children of different races, languages, religions and creed to play, relate and learn in the same setting so that they will know from a young age the diversity in all cultural and ethnic groups.

Individuals schooled in the Singapore education system embody the Desired Outcomes of Education.(10) These individuals are expected to have a good sense of self-awareness, a sound moral compass, and the necessary skills and knowledge to take on the challenges of the future. They are responsible to their family, community and nation. They appreciate the beauty of the world around them, possess a healthy mind and body, and have a zest for life. In summary, they are confident individuals, self-directed learners, active contributors and concerned citizens.

In line with the Desired Outcomes of Education of the Singapore system, the key stage outcomes of pre-school education emphasise the need for children to build up confidence and social skills and be equipped with the necessary knowledge, skills and dispositions for life-long learning. At the end of their pre-school education, children should know what is right and what is wrong; be willing to share and take turns with others; be able to relate to others; be curious and able to explore; be able to listen and speak with understanding; be comfortable and happy with themselves; have developed physical coordination and healthy habits; participate in and enjoy a variety of arts experience; and love their families, friends, teachers and school.

The Ministry of Education (MOE) developed the Nurturing Early Learners(11) Curriculum Framework in 2012 to support and guide early childhood educators in Singapore. As per this curriculum, children are nurtured holistically through six learning areas, and their positive learning dispositions are also cultivated through teacher-facilitated learning experiences. The six learning areas are: aesthetic and creative expression; discovery of the world; language and literacy; motor skills development; numeracy; and social and emotional development. The learning dispositions are positive behaviours and attitudes towards learning, which are important for children in their journey as life-long learners. The six learning dispositions (PRAISE) that pre-schools seek to develop in every child are perseverance; reflectiveness; appreciation; inventiveness; sense of wonder and curiosity; and engagement.

EARLY CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENT AGENCY

The ECDA was set up in 2013 as an autonomous agency to serve as the regulatory and developmental authority for the early childhood sector in Singapore and to oversee key aspects of the development of children aged below seven years across both kindergartens and child/infant care programmes. To ensure that every child has access to affordable and quality early childhood development services and programmes, it promotes accessibility by master planning the infrastructure and manpower resources to support the early childhood sector. In addition, the ECDA provides subsidies and grants to keep quality pre-school programmes affordable. It also facilitates the training and development of early childhood educators and conducts public education and outreach activities that help parents learn about their child’s early development.

The MOE embarked on a pilot programme of MOE Kindergartens (MKs) in 2014. Under this programme, MOE aims to increase the number of MOE Kindergartens to 60 by 2025 to provide more high-quality and affordable pre-school places. All new MKs will be co-located with primary schools to enable closer collaborations between MKs and primary schools on programmes and joint activities, which enrich the learning experience of pre-school children and support their smoother transition to Primary One.

Currently, there are two major anchor operators of Early Years Centres, namely the NTUC My First Skool and PCF Sparkletots. They will continue to focus on children’s early years of learning and development, and collaborate strategically with the MKs to ensure a smooth transition and continuum of quality and affordable pre-school service for children aged two months to six years.

The ECDA is in the best position to advance and integrate support for children with developmental needs in the EI programmes within the pre-schools. An Inclusive Preschool Workgroup consisting of professionals from health, education and social sectors has been formed. The ECDA will work towards having every pre-school appoint an ‘Inclusion Coordinator’ within the existing staff, starting in the second half of 2023. The government will expand outreach for the DS-LS and DS-Plus programmes to more pre-schools to support children requiring low levels of EI support. The target of the DS-LS programme is to cover 60% of pre-schoolers by 2025 and 80% in the steady state. The ECDA will also pilot an Inclusive Support programme, starting at a few pre-schools, to integrate the provision of EI services at pre-schools for children aged three to six years who require medium levels of EI support. In addition, the ECDA will study integration opportunities for children who require high levels of EI support and who are best served in a separate specialised EI setting. These could include partnerships between EI centres and pre-schools to facilitate activities for social interaction.

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EARLY CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENT

The National Institute of Early Childhood Development (NIEC) was incorporated in March 2018 and became fully operational from January 2019 through the consolidation of the early childhood training capabilities and expertise of the Institute of Technical Education (ITE), Ngee Ann Polytechnic, Temasek Polytechnic and NTUC’s SEED Institute to become a major player in early childhood training landscape. The NIEC will centralise and drive all strategic and professional aspects of early childhood training, such as curriculum design and development, academic governance and faculty development. It will offer certificate- and diploma-level pre-employment training courses for post-secondary students interested in joining the pre-school sector. In addition, it will offer Continuous Education and Training (courses for mid-careerists, and in-service upgrading and Continuing Professional Development courses) to further develop the competencies of in-service teachers and leaders. The strategic partners of NIEC include National Institute of Education, ECDA, Workforce Singapore, Employment and Employability Institute, and other industry operators. NIEC will cover about 60% of the training of pre-school teachers in the sector. Other major training providers in the private sector include Kinderland Consortium International Institute and Asian International College, to allow more diversity in the training approach.

SUPPORT FOR CHILDREN WITH DEVELOPMENTAL NEEDS IN MAINSTREAM SCHOOLS

Mainstream school is the usual learning environment for children who have adequate cognitive skills to cope with the demands of the national curriculum, as well as the adaptive skills to communicate and learn in a large group setting. In Singapore, a multi-pronged approach is adopted to cater to the diverse educational needs of students with developmental needs. Around 80% of students with SEN are in mainstream schools. Many of them, as well as the majority of students with sensory and physical impairment, have specific learning difficulties such as dyslexia, ADHD and ASD. The other 20% of children who have moderate-to-severe SEN are in SPED schools,(7) where they receive a highly customised curriculum and pedagogy delivered by trained SPED teachers and supported by a range of allied professionals.

Teachers Trained in Special Needs (TSNs) are classroom teachers who have completed certificate-level training in special needs and are equipped with the skills required to support pupils with mild special needs by planning classroom instruction to cater to the pupils, adapting and differentiating the curriculum to suit the pupils’ needs, monitoring their progress and sharing relevant strategies with parents and fellow teachers, and facilitating the transition of pupils from one level to the next. In 2010, 10% of all primary school teachers have been trained as TSNs.

Mainstream schools have dedicated non-teaching staff known as Special Needs Officers (SNOs) with training in special education to support pupils with mild special needs by providing in-class support, providing individual/small group intervention or skills training, developing learning resources that are appropriate for pupils, monitoring the pupils’ progress, communicating and working closely with the teachers in the schools as well as specialists from the MOE, communicating with parents regarding the learning needs and progress of the pupils, and working with external agencies. The SNOs are now known as Allied Educators (Learning and Behavioural Support) (AED[LBS]).

The Learning Support Programme caters to Primary 1 and 2 students who need additional help with English. It is held for 30 minutes a day and in small groups of eight to ten students. In some primary schools, the programme is broadened to provide remedial support to pupils who lag behind in their academic capabilities. School counsellors provide support to students with personal or academic challenges, while Student Welfare Officers help disadvantaged students continue their schooling and establish links between the families and the relevant community resources, such as the family service centres.

TRANsition Support for InTegration (TRANSIT) takes place during Primary 1 to help students with social and behavioural needs develop independence through learning of fundamental self-management skills based on their specific needs. Schools will proactively identify these students for support based on information gathered from parents, teachers and EI educators in pre-schools, and through systematic observations conducted by trained school personnel, including teachers and AED(LBS). TRANSIT will be introduced progressively to all primary schools by 2026.

Certain primary schools have a School-based Dyslexia Remediation Programme for students with dyslexia in Primary 3 and 4. Students with dyslexia in other levels will have access to the Main Literacy Programme conducted by The Dyslexia Association of Singapore (DAS). The DAS has also been given funds to provide early testing of pre-school children suspected of having learning disabilities, so that early intervention can be started to make these children better prepared as they enter mainstream primary schools.

To help children with emotional, social and/or behavioural difficulties and disorders, such as ASD and ADHD, schools work closely with REACH (Response Early Intervention and Assessment in Community Mental Health) services and parents on suitable school-based interventions and support.

Children with visual impairment, hearing loss and/or physical impairment may tap on itinerant educational support services, where personnel from SSAs such as AWWA and Singapore Association for the Deaf provide additional support in school to enhance the child’s accessibility to learning and the environment. The MOE also provides assistive technology such as Frequency Modulation systems, magnifiers and text-to-speech software for children’s use. In addition, there are barrier-free facilities to help children with physical impairments. All primary and secondary schools in Singapore will have lifts by 2025. The schools will also provide accessibility accommodations for children to complete tests and national examination papers, such as larger fonts, extra time, presence of prompters, and conductance of the examination in a separate room with fewer distractions. The advocacy role of the paediatricians would be even more important then.

Children with DN are vulnerable groups in schools and they need to be accepted and protected. Two intervention programmes have been introduced that leverage peer support: Circle of Friends for primary and secondary students, and Facing Your Fears for secondary students. Singapore Children’s Society has been advocating for bully-free schools since 2008 and ‘Bully-free Schools’ campaigns have been organised on a regular basis. Some schools have taken up the bully-free programme as part of their co-curricular activities.

Pathlight School has been successful in offering the Singapore primary and secondary national curriculum to children with mild to moderate autism who lack adequate social and communication skills to allow them to cope in the usual mainstream schools. The school also has a suitable post-primary programme for students with ASD who are unable to access the national secondary curriculum. Several education tracks are designed according to the academic capabilities and behavioural competencies of these children. The MOE will set up two more similar schools for these students in the next few years.

In 2007, Northlight School was set up with the mandate to engage and to continue to provide learning opportunities to teenage premature primary school leavers or those who have not done well in the Primary School Leaving Examination. Assumption Pathway, another school of similar nature, opened in 2009. The goal is to assist these children to set aside their past academic failures, allow them to discover their individual strengths, maintain their self-esteem, and encourage character development and vocational training.

Crest Secondary School, a Specialised School for Normal (Technical) students, took in its first batch of Secondary One students in January 2013. This was followed by Spectra Secondary School in 2014. Both schools offer a customised curriculum that integrates both academic learning and vocational training. Apart from subjects such as English Language, Mathematics, Basic Mother Tongue (Chinese, Malay, Tamil) and Science, the schools also offer four ITE Skills Certificate courses, namely Hospitality Services, Retail Services, Facility Services and Mechanical Servicing. Learning will be practice oriented, with an emphasis on skills development to prepare students for progression to post-secondary skills training at the ITE and for employment. Industrial attachment will be an important component of the ITE Skills Certificate learning experience for the students. In addition, the schools will adopt innovative pedagogies to strengthen students’ literacy and numeracy skills. A key cornerstone of the school’s holistic education is in building students’ character, with a strong focus on value education, and strengthening social and emotional competencies.

Students in Singapore are encouraged to discover and develop their own strengths, follow and pursue their diverse passions in academic fields, sports and the arts, and emerge from schools being confident of their abilities. Our educational system has become more flexible and diverse, with wider range of curricula and schools, providing students more choices in pursuing their interests along pathways that better fit their learning styles. The vision is to ‘build a mountain range with many peaks of excellence’.

From 2008, streaming of primary school pupils into EM1, EM2 and EM3 (E: English, M: Mother Tongue) was phased out. Instead, depending on their strengths, the pupils will study subjects at different levels of difficulty – the Standard level or the easier Foundation level. Therefore, there is a shift from a ‘fixed’ menu to a subject-based ‘a la carte’ menu of study (subject-based banding). With more flexibility in the curriculum, catering to the different abilities of students instead of a one-size-fits-all approach, students will not be easily discouraged and leave the school system prematurely. These changes in our educational approach would allow many children with different developmental problems to be included in the mainstream schools, supported by trained teachers and integrated with their peers in their learning experiences. The emphasis is on allowing opportunities for them to continue to learn and develop their innate strengths so that their talents will be valued, thus widening the definition of success.

CARING FOR CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL EDUCATIONAL NEEDS

SPED schools provide education to about 20% of students of school-going age with SEN who have higher support needs.(7) From 2019, all children with moderate-to-severe SEN have been included within the Compulsory Education framework. Currently, there are 19 SPED schools run by 12 SSAs. SPED schools charge different fees, as they have to customise their programmes and services to meet the diverse and specialised learning needs of their students.

The MOE’s vision for these students is to be ‘Active in the Community and Valued in Society’. For this purpose, students need to be equipped with the knowledge, skills and attributes to participate meaningfully in their communities and become contributing citizens who are valued by the society. SPED schools are guided by the SPED Curriculum Framework, ‘Living, Learning and Working in the 21st Century’, released in 2012,(12) in designing and delivering quality and holistic education for their students. SPED schools offer customised educational programmes aimed at developing the potential of students and helping them to be independent, self-supporting and contributing members of the society. Besides being taught by specialised teachers, students in all SPED schools are provided with supporting facilities and also receive support from allied professionals such as psychologists, speech and language therapists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists and social workers.

The SPED schools have established long-term sustained Satellite Partnerships with mainstream schools, where there are opportunities for purposeful social interactions between the students through platforms such as joint co-curricular activities, recess, workshops and camps. For example, Townsville Primary School and Pathlight School for Children with Autism are located adjacent to each other in Ang Mo Kio. During the 30-minute break each day, students share their meals and play games such as badminton and table tennis. At Canossian School for the Hearing Impaired, students attend daily lessons and participate in co-curricular activities alongside other children from MacPherson Primary and Canossa Primary Schools. Students from Dunman High School and MINDS Towner Gardens School do joint community service projects, arts and craft, and science activities. The Play Inclusive Campaign organised by SportCares and Special Olympics Singapore also brings together student athletes from several SPED and mainstream schools to share sporting experiences as members of the same team. They also rehearse, practise and perform together during National School Games, Youth Festival and National Day Parade.

SOCIAL AND COMMUNITY SUPPORT

The social safety net in Singapore is a unique ‘Many Helping Hands’ approach, which involves the partnership of all sectors of the society and the government. The many helping hands consist of the MSF, NCSS and Community Chest (its fund-raising arm), community development councils, SSAs, philanthropic organisations and foundations, grass-roots organisations, financial corporations and consumer groups, as well as parent support groups and associations. The principle is to foster self-reliance. Family remains the primary line of support, including financial and emotional support. The emphasis is on social assistance and not welfare.

Supplementary services are available to provide tangible financial or other material help to families. Supplementary helps targeted specifically at children’s needs are also available. The Community Care (ComCare) Fund was established in 2005 to provide sustainable funding for social assistance programmes for low-income Singaporeans, with the majority of the fund catering to programmes for children from disadvantaged families. The President’s Challenge is a movement supported by the kindness and generosity of people from all walks of life. It calls for the nation to do its part to build a more caring and inclusive society and to help the less fortunate. Singapore Press Holdings sponsored the School Pocket Money Fund, which raised large sums for distribution to ensure, among other things, that poor children can afford food at school recess times. Many SSAs also organise activities such as walks to raise funds that can be tapped to supplement needs for needy children. Ethnic community organisations, such as the Chinese Development Assistance Council; Mendaki and the Association of Malay Professionals; Sinda; and the Eurasian Association – serving Chinese, Malays, Indians and Eurasians, respectively – have an educational focus. Besides financial assistance, they also provide low-cost tuition to school children and parental education.

In 2013, the MSF started setting up social service offices (SSOs) in Housing and Development Board (HDB) towns to provide more accessible and coordinated social assistance to Singaporeans in need. The rollout of the full network of 24 SSOs was completed in 2015, and 95% of ComCare beneficiaries now live or work within 2 km of an SSO. Physical accessibility to and awareness of ComCare have increased because of the SSOs, making it easier for needy families to seek help. Besides providing ComCare assistance directly, SSOs also do ground-sensing and collaborate with SSAs and community partners to identify needs within each HDB town, to provide more holistic support to those in need.

In 2016, the ECDA initiated a new system of support for low-income and vulnerable children to enable them to have a good start in life. The new initiative, called KidSTART, coordinates and strengthens support across agencies, extends new forms of support and monitors the progress of these children from birth to six years of age. Through KidSTART, families requiring additional support are proactively identified. Their children are provided with early access to appropriate health, learning and developmental support. Parents are supported and equipped with parenting knowledge and resources to nurture the child at home, through home visits, parental education and/or family support programmes. Selected pre-schools will also provide additional support and work with parents to better support their child through the pre-school years and transition to primary school. The families will also be linked up with existing community resources for additional assistance, according to their needs.

The KidSTART programme will gradually expand to more regions in Singapore. A dedicated KidSTART Singapore office has been set up to partner an anchor SSA in each region, to support coordinated outreach to families and the programme implementation. Through the Growing Together with KidSTART initiative launched in 2019, the Government will continue to deepen and forge partnerships with the community and grow the pool of volunteers to reach more families.

In April 2019, the MSF launched Community Link (ComLinK), which has since been scaled up nationwide to provide comprehensive, convenient and coordinated support to families with children living in rental housing so that they can achieve stability, self-reliance and social mobility. ComLink is a key initiative under the SG Cares Community Network, a Singapore Together Alliance for Action announced in 2020. This is done through proactive outreach and closer case support, galvanising the community to offer customised programme and services to the families. At each ComLink town, the SSO leads a ComLink Alliance, comprising government agencies, corporate partners and community partners, to pool together resources and steer the effort.

Supportive services are social service provisions that strengthen the capacity of parents to fulfil their roles more effectively. Many families, including normal functioning families, require support to enable the social functioning of adults in their parental roles. These include affordable housing and healthcare services; job availability, training and re-training; family-friendly workplaces; and affordable quality childcare facilities for working parents and recreational facilities.

When both parents work, and when care by other family members is not available, alternative affordable and quality care arrangements by non-family members become necessary. While there are alternative care options by foreign domestic workers and family day-care providers who take care of a small group of children in their own home, infant and childcare and student care centres are some of the services that families have come to rely upon as more mothers join the work force.

Childcare centres cater to children from infancy up to the age of seven years as a service for working parents, with subsidised fees. Childcare centres are licensed by the MSF to ensure not only the children’s safety and well-being, but also their learning and development. A number of these centres have also expanded their services to include parenting education and counselling, parent support services, as well as public education programmes for families with children under their care. The emphasis is on encouraging parental participation in the care of their children.

Student care centres cater to primary school children who have no adult at home when they return from school or before they go to school. These children may be lonely and bored, and may seek distraction outside the home such as frequenting shopping centres and getting involved in undesirable activities with questionable company without their parents’ knowledge. Student care centres provide a place where these children can have a proper meal, do their homework and engage in recreational activities under the supervision of adults. The after-school services will be further extended to pre-schoolers, secondary school students and children with special needs.

An extensive network of family service centres (FSCs) is available in Singapore to offer general family-oriented programmes, ranging from parent education to family counselling and student care. The MSF will be rolling out the Strengthening Families Programme@FSCs at various locations across Singapore over the next few years. It will consolidate the existing FSC programmes and put in place a continuum of services, from upstream preventive initiatives targeted at couples who may face greater challenges and families showing early signs of stress to supporting families with complex and multiple issues. It will adopt a regional, integrated and multidisciplinary approach to support families in a holistic way. In each region, it will work closely with other service providers such as the respective SSOs and FSC partners, as well as bring together professionals trained in family counselling, financial counselling and psychology to address the families’ needs.

STRENGTHENING PARTNERSHIPS WITH FAMILIES

Parents and caregivers play the most critical role in a comprehensive, inclusive early childhood intervention system. The family is the most powerful and pervasive influence, and the constant in a young child’s life. The family is likely to be the only group of adults involved with the child’s educational programmes throughout his or her entire learning journey. There are many success stories where parents heroically enter into the world of their children, discover their hidden talents and start a fruitful learning journey together. Caring for the caregivers is one of the key areas to address in the Enabling Masterplan III (2017–2021).(13)

Professionals must always recognise the expert contribution of parents. They must always be aware that their attitudes and assumptions about parents would become roadblocks to a productive partnership: treating parents as vulnerable and helpless clients; keeping professional distance (aloofness and coldness); treating parents as if they need therapy and counselling; blaming parents for their child’s condition; disrespecting parents as less intelligent; treating parents as adversaries; and labelling parents (as denying, resistant, anxious, uncaring, troublesome, hostile,…), so that the parents feel intimidated, confused and angry. Professionals must work in collaboration with families to address the child’s needs in a way that is consistent with the priorities of the entire family. There should be a complete and unbiased exchange of information between families and professionals. Policies and programmes should address these diverse needs, and recognise and honour cultural diversity, and the strengths and individualities of all families. The principles of family-centred approach are empowering families, providing social support, building relationships with families as the basis for intervention, building communication skills and maintaining effective communication.

Since March 2011, a community-level programme called ‘Signposts for Building Better Behaviour’ (‘Signposts’) was introduced to help enhance the knowledge, skills and mental well-being of parents and caregivers of children with developmental needs, and to equip them to understand their child’s difficult behaviour, develop better ways to manage them more effectively and prevent the development of behavioural consequences. ‘Signposts’ is delivered through a network of qualified and trained facilitators from KKH, NUH, EIPIC centres and other centres across Singapore. Parents who have participated in ‘Signposts’ continue to meet regularly to share and support each other through the parent-initiated CASPER (Caring And Sharing Parents, Ever Resilient) programme.

The Caregivers’ Space has been set up at the Enabling Village by SG Enable in 2018 to serve as a meeting place for peer support groups, training of caregivers of persons with disabilities and engagement sessions by SSAs as well as community partners for caregivers. Caregivers will also be able to get information and advisory service at Enabling Village. Besides SG Enable, the Special Needs Trust Company and SSAs providing disability services are also part of the caregivers’ network of support.

COMPLETING THE JIGSAW PUZZLE

Our vision of an inclusive early childhood intervention in Singapore is to start upstream in identifying families at risk even before the birth of the child. These families would receive early social and health support to ensure that the young child could receive optimal care and protection after birth in terms of appropriate nutrition, immunisations and early developmental stimulations. The regional social and community support system, with both the government and SSAs working closely in partnership, would ensure that these children receive early learning experience in childcare centres and pre-schools. Children with developmental needs are identified early and put under the continuum of care of EIPIC, DS-LS and DS-Plus programmes. The pre-schools would serve as an integrated and inclusive learning environment with trained pre-school teachers, learning support educators, inclusion coordinators and allied health professionals. Families are active participants in the entire process, which will facilitate seamless transition of the children from pre-schools to the next stage of education.

The transition from adolescence to adulthood after childhood interventions is a process, not an event, and should begin as early as possible, taking into account the young person’s developmental stage and the functional impact of the disability. Some of the future expectations and challenges would include moving towards independence; developing social competence; moving towards post-secondary education; entering the work force; community living; participation in sports, leisure and community activities; issues of sexuality; and developing a life plan. Outcome evaluation is a continuous process and should be interpreted from the perspectives of the summative effectiveness and efficiency of the network of medical care, social and community support, education, and parental and family participation in the ecosystem. On the one hand, professionals in the childhood programmes must prepare to ‘let go’ of the developing young adults. On the other hand, they should go beyond their comfort zone of medical care and continue to be ready to take on the leadership role in advocacy to ensure that the young adults continue to receive the best possible care with the best possible outcomes, as their life-course commitment.

CONCLUSION

Singapore has a new vision towards building an inclusive society with a broader definition of meritocracy that entails recognising different strengths and different individuals. The narrow meritocratic system that focuses too much on academic qualifications will make way for a more flexible and diverse broad-based education system that provides many paths for students to grow and develop. We look forward to building a mountain range with many peaks of excellence. Tackling inequality and building a fair and just society have to start in pre-schools. However, pre-school education is only a component of a comprehensive early childhood programme. It must be complemented with an effective early childhood development and intervention programme, a nationwide supportive network of social and community services for the families, and an efficient legal framework in child protection. This way, every child’s talent would be valued and no child would be left behind.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shonkoff JP, Phillips DA. From Neurons to Neighborhoods:The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho LY. Child Development Programme in Singapore 1988 to 2007. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2007;36:898–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho LY. Building an inclusive early childhood intervention ecosystem in Singapore 1988–2017. 16th Haridas Memorial Lecture, Singapore Paediatric Society. 2018. Published by KK Women's and Children's Hospital, Singapore [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Enabling Masterplan (2012–2016) Ministry of Social and Family Development, Singapore. [Accessed March 23, 2021]. Available at: www.msf.gov.sg .

- 5.Lim HC, Chan T, Yoong T. Standardisation and adaptation of the Denver Developmental Screening Test (DDST) and Denver II for use in Singapore children. Singapore Med J. 1984;35:156–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim HC, Ho LY, Goh LH, et al. The field-testing of Denver Developmental Screening Test (DDST) Singapore:a Singapore version of Denver II Developmental Screening Test. Ann Acad Med Singap. 1996;25:200–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Education, Singapore (2019) Speech by Ms Indranee Rajah, Second Minister for Education, at an Extraordinary Celebration Concert. [Accessed February 27, 2020]. Available at: https://www.moe.gov.sg/news/speeches/speech-by-ms-indranee-rajah--second-minister-for-education--at-an-extraordinary-celebration-concert .

- 8.Mission:I'mPossible, The Road Map. Department of Child Development, KK Women's and Children's Hospital. Singapore: Booksmith Publisher; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chong WH, Moore DW, Nonis KP, et al. Department of Child Development, KK Women's and Children's Hospital. Singapore: Booksmith Publisher; 2012. Mission:I'mPossible:Evaluation Report. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desired Outcomes of Education, Ministry of education, Singapore. [Accessed March 23, 2021]. Available at: https://www.moe.gov.sg/education/education-system-desired-outcomes-of-education.pdf .

- 11.Nurturing early learners:A curriculum framework for kindergartens in Singapore. Ministry of Education. [Accessed March 24, 2021]. Available at: https://www.moe.gov.sg/preschool/curriculum .

- 12.21st Century Competencies, Ministry of Education. [Accessed March 24, 2021]. Available at: https://www.moe.gov.sg/education-in-sg/21st-century-competencies .

- 13.Enabling Masterplan 2017-2021. Ministry of Social and Family Development, Singapore. [Accessed March 24, 2021]. Available at: www.msf.gov.sg .