Abstract

Introduction

This study examined the long‐term influence of loneliness and social isolation on mental health outcomes in memory assessment service (MAS) attendees and their care partners, with a focus on interdependence and bidirectionality.

Methods

Longitudinal data from 95 clinic attendees with cognitive impairment, and their care partners (dyads), from four MAS in the North of England were analyzed. We applied the actor–partner interdependence model, seeking associations within the dyad. At baseline and 12‐month follow‐up, clinic attendees and care partners completed measures of loneliness and social isolation, depression, and anxiety.

Results

Social isolation at baseline was more prevalent in care partners compared to MAS attendees. Social isolation in MAS attendees was associated with higher anxiety symptoms (β = 0.28, 95% confidence intervals [CIs] = 0.11 to 0.45) in themselves at 12 months. We found significant positive actor and partner effects of loneliness on depression (actor effect: β = 0.36, 95% CIs = 0.19 to 0.53; partner effect: β = 0.23, 95% CIs = 0.06 to 0.40) and anxiety (actor effect: β = 0.39, 95% CIs = 0.23 to 0.55; partner effect: β = 0.22, 95% CIs = 0.05 to 0.39) among MAS attendees 1 year later. Loneliness scores of the care partners have a significant and positive association with depressive (β = 0.36, 95% CIs = 0.19 to 0.53) and anxiety symptoms (β = 0.32, 95% CIs = 0.22 to 0.55) in themselves at 12 months.

Discussion

Loneliness and social isolation in MAS clinic attendees had a downstream effect on their own and their care partners’ mental health. This highlights the importance of including care partners in assessments of mental health and social connectedness and expanding the remit of social prescribing in the MAS context.

Keywords: actor–partner interdependence model, anxiety, dementia, depression, loneliness, social isolation

1. INTRODUCTION

Loneliness and social isolation are important risk factors for a range of negative outcomes in older people, including cognitive decline, 1 , 2 dementia, 3 greater physical morbidity, 4 and higher mortality rates. 5 Loneliness is a subjective sense of inadequate quantity or quality of social contact and longing for close and emotional relationships with others. 6 , 7 Social isolation is an objective and quantifiable lack of, or reduction of, social network size and social contact. 5 , 8 Older adults may be at increased risk of being socially isolated and lonely due to bereavement, relocation, living alone, or loss of friends and social networks, all of which have been exaggerated by the COVID‐19 pandemic. 9 , 10 Loneliness may also arise in the context of marital or cohabiting relationships, particularly related to aging, due to changes in intimacy, functional decline or the emergence of illness, including neurodegenerative disorders leading to dementia. 11 , 12 The relationship between the caregiving role and loneliness and social isolation in care partners of people with cognitive disorders and other neurodegenerative conditions is gaining attention, especially due to the disruptions in care and support services brought on by the pandemic. 9 , 11 Thus, there have been calls for further quantitative studies to understand these issues better in people with cognitive disorders and their care partners, for whom loneliness is now an important public health concern. 13

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic Review: The authors reviewed the literature using PubMed for articles on care burden and mental health in care partners of people with cognitive disorders. There is still an urgent need for research looking at the link between loneliness and social isolation of people with cognitive disorders on the mental health of their care partners. We thus evaluated the possibility of collecting real‐world data from memory assessment services (MAS), as well as the acceptability of digital wearable devices in combination with patient‐ and clinician‐reported outcomes and conventional dementia‐related measures. We aim to examine how loneliness and social isolation in memory clinic attendees and their care partners influences mental health outcomes in both members of the dyad 12 months later. The analyses are based on longitudinal dyadic data from 95 MAS attendees and their care partners.

Interpretation: Findings of our study highlight the importance of addressing loneliness and social isolation at the point of presentation to services, even if offered remotely by means of virtual clinics, to obviate poor mental health outcomes of people with cognitive impairment and their care partners. MAS are uniquely placed to intervene early to maintain the mental well‐being of this population

Future Directions: More detailed and longer‐term studies are needed to further clarify the impact of members of the dyad on each other's outcomes over time, particularly considering the degenerative nature of dementia. Opportunities to intervene and support people with dementia and their care partners can thus by sought.

In many high‐income countries, memory assessment services (MAS) are often the first point of contact with care services for older people with cognitive impairment or dementia, and their families or care partners. In view of the limited effectiveness of anti‐dementia medication, 14 the focus of dementia care is often on well‐being or “living well with dementia.” 15 Well‐being includes the concept of social connectedness. 16 Loneliness and social isolation are threats to well‐being yet may be aspects that are potentially easy to identify, reverse, and, ideally, avoid. Thus, MAS, with a focus on the dyadic relationship between the person with cognitive impairment and their care partner, can play a key role in identifying and addressing loneliness and social isolation, particularly as the role of social prescribing is gaining greater acceptance in health‐care settings. 17

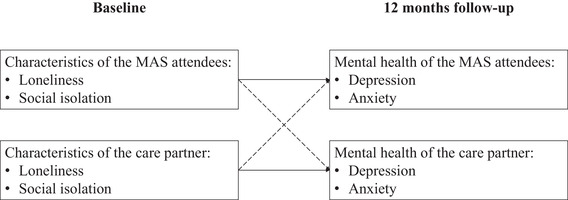

Our overall aim in this study was to explore the prevalence and direction of association of loneliness, social isolation, and aspects of mental health in MAS attendees and their care partners attending four regionally distributed MAS in the North of England. Our focus was on the dyadic relationship between the attendee and their care partner, aiming to understand “actor–partner” effects using a model of dyadic relationships that integrates a conceptual view of bidirectional interdependence. 18 Specifically, we first sought to determine whether there were actor effects, which is whether an individual's loneliness and social isolation predicts their own mental health at a subsequent time point. Specifically, we hypothesized that MAS attendees and their care partners’ loneliness and social isolation at baseline would predict their respective mental health status, as reflected by anxiety and depressive symptoms, 12 months later. Next, we sought to identify whether there were partner effects, whereby an individual's loneliness and social isolation could predict their partner's mental health a year later. We hypothesized that individuals’ characteristics (i.e., loneliness and social isolation) and their partners’ mental health 1 year later would be interdependent. For example, the MAS attendee's loneliness at baseline would predict the care partner's depression and anxiety status in the later wave. The hypothesized associations are illustrated in the conceptual model (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual model illustrating hypothesized interdependence among respondents and their care partners’ characteristics and mental health over 12 months. Note: solid line: actor effects; dashed line: partner effects

2. METHODS

Data for this study came from Project CYGNUS, a non‐interventional prospective observational study exploring ways of gathering meaningful data from people with memory problems in the real world. 19 To achieve the aims of Project CYGNUS, the baseline and quarterly data from consecutive MAS attendees (n = 224) and their care partner (n = 172) was collected over a 24‐month period. We included MAS attendees with care partners, both of whom had completed loneliness and social isolation questionnaires at baseline, and depression and anxiety questionnaires in the 12‐month follow‐up point. This gave a sample of 95 dyads, with the selection procedure, as illustrated in Figure S1 in supporting information. We used an online application of post hoc power analyses to calculate power curves for the actor–partner interdependence model (APIM) with indistinguishable dyads. The calculations indicated that with 95 couples, we had 96% power to detect the effects. 20 All participants were assessed for capacity to consent to the study and if they lacked the capacity to consent, a nominated consultee was appointed, as per the UK's Mental Capacity Act. 21 The study was approved by the London‐Central Research Ethics Committee and was conducted according to standards set by the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki. 22 Details of Project CYGNUS study protocol are outlined elsewhere. 19

2.1. Measures

2.1.1. Loneliness

We used the 3‐item short form of the revised UCLA Loneliness Scale, 23 which is the most commonly used quantitative self‐report measure of loneliness and has been validated in different populations. 24 Questions were: 1. “How often do you feel you lack companionship?”; 2. “I felt left out”; 3. “I felt isolated.” Response options are: “hardly ever or never,” “some of the time,” and “often.” Scores were summed to provide a loneliness score ranging from 3 to 9, higher scores indicating greater loneliness.

2.1.2. Social isolation

We used a three‐item questionnaire to record social isolation. The items were: (1) In the past month, how often did you see your friends and family? (2) In the past month, how often did you call/receive a phone call from your friends and family? (3) In the past month, how often have you used the computer/table to e‐mail or contact your friends or family? The items were scored by responding as “1 = three or more times a week; 2 = once a week; 3 = less than once a week; or 4 = not during last month.” The social isolation index was calculated by adding the score given to each item by respondents. Scores ranged from 3 to 12, with higher scores indicating greater isolation.

2.1.3. Depression and anxiety

We used the 14‐item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in which seven items measured anxiety and seven items measured depression. 25 Items are rated on a 4‐point Likert scale (scored from 0 to 3) and refer to how the person felt over the past week. Total scores for each subcategory are divided into categories of normal (0–7), mild (8–10), moderate (11–14), and severe (15–21).

2.1.4. Analysis

First, we performed descriptive statistics of each variable and bivariate analysis using Pearson correlation. We then constructed longitudinal APIM using the structural equation modeling (SEM) approach to answer the research questions. 26 The SEM allows a direct translation of the APIM as in SEM: (1) more than one equation can be estimated and tested simultaneously, and (2) the associations between parameters in different equations can be specified. This model examined whether there were longitudinal actor effects (e.g., loneliness of MAS attendees at baseline predicting their depression symptoms at a later time point) and partner effects (e.g., loneliness of MAS attendees at baseline predicting the depression symptoms of care partners at a later time point). Good model fit is indicated by a root mean square error of approximation (RSMEA) of less than 0.08, and comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker Lewis index (TLI) of 0.90 or higher. 27 The analysis was performed using STATA 15.

3. RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the participants with dementia and their care partners are outlined in Table 1. On average, the MAS attendees were 7.3 years older (P < .001) than the care partners. The proportion of female sex (73.68%) among care partners was twice as high as the MAS attendees (35.79), and that difference was significant (P < .001). There was no significant difference in proportion of education attainment (P = .164) and ethnic minorities (P = .561) between MAS attendees and the care partners. Lower proportion of MAS attendees living with partner (P = .009) and working full time or part time than the care partners (P < .001).

TABLE 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the sample at baseline

| MAS attendees | Care partners | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 76.62 (8.44) | 69.22 (11.23) |

| Sex, % | ||

| Male | 64.21 | 26.32 |

| Female | 35.79 | 73.68 |

| Ethnicity, % | ||

| White British | 98.95 | 97.89 |

| Other | 1.05 | 2.11 |

| Education, % | ||

| None | 1.06 | 1.05 |

| Primary | 2.13 | 0 |

| Secondary | 72.34 | 62.11 |

| Tertiary | 24.47 | 36.84 |

| Living status, % | ||

| Living alone | 9.47 | 1.05 |

| Living with partner | 90.53 | 98.95 |

| Working status, % | ||

| Full time | 1.05 | 6.32 |

| Part time | 0 | 7.37 |

| Not in paid employment | 1.05 | 9.47 |

| Retired | 94.74 | 69.47 |

| Other | 3.16 | 7.37 |

Abbreviation: MAS, memory assessment service.

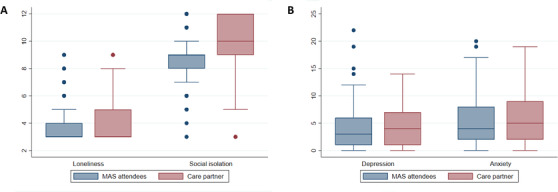

The descriptive statistics revealed that on average, the care partners reported slightly higher loneliness (mean = 4.02; standard deviation [SD] = 1.63) than the MAS attendees (m = 3.90; SD = 1.45) at baseline (Figure 2A). The analysis also demonstrates that care partners tend to be more socially isolated (m = 9.74; SD = 2.13) than the MAS attendees (m = 8.52; SD = 1.88). After 12 months, Figure 2B illustrates that the care partners reported a similar rate of depressive symptoms (m = 4.34; SD = 3.61) but higher anxiety (m = 5.99; SD = 4.43) than the MAS attendees (depression symptoms: m = 4.40; SD = 3.86; anxiety: m = 5.16; SD = 4.70). The t test analysis shows that the difference values between MAS attendees and their care partner only significant for social isolation (P < .001).

FIGURE 2.

Box plot of the study variables for memory assessment service (MAS) attendees and care partners, Plot A: Comparison of loneliness and social isolation in MAS attendees and care partners; Plot B: Comparison of depression and anxiety in MAS attendees and care partners

Bivariate correlations (Table 2) showed that the increase in one score of MAS attendees’ loneliness at baseline was related to 0.43 and 0.38 higher scores of their own depression and anxiety 12 months later (P < .001). In addition, one higher score of MAS attendees’ loneliness at baseline increased their care partners’ depression and anxiety 12 months later by 0.22 (P = .022) and 0.27 (P = .005), respectively. The addition of one social isolation score among MAS attendees at baseline increased the social isolation scores of their care partner at the same time point by 0.36 (P < .001). One score increase of the care partners’ loneliness at baseline was related to 0.45 (P < .001) and 0.46 (P < .001) higher scores of their own depression and anxiety 1 year later. Higher care partners’ social isolation index was associated with 0.20 lower depression symptoms later in life (P = .033).

TABLE 2.

Correlations among study variables in MAS attendees and care partners

| Loneliness in the MAS attendees | Social isolation in the MAS attendees | Loneliness in the care partner | Social isolation in the care partner | Depression in the MAS attendees | Anxiety in the MAS attendees | Depression in the care partner | Anxiety in the care partner | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness in the MAS attendees | – | |||||||

| Social isolation in the MAS attendees | –0.10 | – | ||||||

| Loneliness in the care partner | 0.07 | –0.06 | – | |||||

| Social isolation in the care partner | 0.01 | 0.36* | –0.14 | – | ||||

| Depression in the MAS attendees | 0.43* | –0.07 | 0.17 | 0.00 | – | |||

| Anxiety in the MAS attendees | 0.38* | 0.17* | 0.17 | –0.04 | 0.57* | – | ||

| Depression in the care partner | 0.22* | 0.05 | 0.45* | ‐0.20* | 0.25* | 0.18 | – | |

| Anxiety in the care partner | 0.27* | 0.14 | 0.46* | 0.00 | 0.37* | 0.48* | 0.49* | – |

Note: * = significant at < 0.05.

Abbreviation: MAS, memory assessment service.

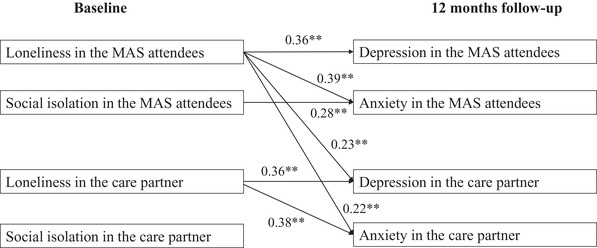

To examine the hypotheses that there would be actor and partner effects in 1‐year longitudinal data, the hypothesized model was constructed, including direct effects among all variables. The model demonstrated adequate fit of the data, RSMEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.982, TLI = 0.935, and P < .001. Standardized path coefficients for the model are presented in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Final model illustrating actor–partner interdependence model predicting memory assessment service (MAS) attendees and their care partners’ mental health in the 12 months of follow‐up. Note: * = significant at < 0.05. ** = significant at < 0.001. Standardized path coefficients are presented. Only significant coefficients are included in the figure

Results revealed several significant actor effects. MAS attendees’ loneliness scores were associated with their own depression (β = 0.36, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.19 to 0.53) and anxiety (β = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.23 to 0.55). MAS attendees who felt socially isolated tended to have higher anxiety symptoms (β = 0.28, 95% CI = 0.11 to 0.45) 1 year later. The care partners who felt lonely tended to have higher symptoms of depression (β = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.19 to 0.53) and anxiety (β = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.22 to 0.55). Several significant partner effects were also found. The care partners of MAS attendees with higher loneliness scores were more likely to have higher symptoms of depression (β = 0.23, 95% CI = 0.06 to 0.40) and anxiety (β = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.05 to 0.39). Four error co‐variances between variables are estimated: between MAS attendees’ and their care partners’ loneliness; between MAS attendees’ depressive symptoms and anxiety; between care partners’ depressive symptoms and anxiety; and between MAS attendees’ and their care partners’ anxiety.

4. DISCUSSION

The primary aim of this study was to test for actor and partner effects in the association among loneliness, social isolation, and depression and anxiety among MAS attendees and their care partners. Although these data were collected pre‐COVID‐19, this question has particular resonance during the pandemic due to the social restriction measures that have been put in place worldwide. Even before the pandemic, people with dementia and their care partners were often socially isolated; pandemic‐related social restrictions have exaggerated this, leading to significantly higher levels of loneliness and social isolation in care partners of people with enduring brain health conditions. 9

Here, our results revealed that loneliness in MAS attendees was associated with a higher level of depression and anxiety for both MAS attendees and their care partners. These results are critical as they underscore how the mental state and well‐being of one member of a care dyad can affect the other member, strengthening the need to address the psychological aspects of both members of the dyad, even though only one may be a formal patient. Care partners are essential in supporting disease management and activities of daily living of people with neurodegenerative conditions. However, providing care can directly impact negatively on caregivers’ self‐efficacy, quality of life, and physical and mental health, and result in caregiver burden. 11 , 12 Our current findings extend this by demonstrating the additional impact on care partners’ mental health through the experience of loneliness and social isolation by the care recipient.

Our finding demonstrating the actor effects of loneliness and social isolation on depression is consistent with prior studies. 28 , 29 For example, Barg et al. found that loneliness among adults aged 65 years and older in the United States was highly associated with depressive symptoms and anxiety, 28 which has important implications for COVID‐19–related increases in loneliness and social isolation globally. 30

Interestingly, and contrary to our hypothesis, care partners’ loneliness and social isolation had no significant partner effect on MAS attendees’ mental health. There are several possible reasons why loneliness of the care partners may have predicted increases in depressive symptoms and anxiety for themselves, but not the MAS attendees. It is possible that due to the disruption of emotion‐specific neural networks in neurodegenerative disorders, detection of the emotional states in others is diminished, 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 disrupting the expected process of recognition of emotional states in others.

There are certain limitations of this study that must be considered when interpreting the findings. First, despite the longitudinal nature of the data used in our analysis, only dynamic prediction, rather than causality, can be inferred. Second, the relatively small sample size in this study prevents us from using more complex analysis. Nonetheless, this initial exploration of the dyadic impact of negative emotions in people attending MAS is an important finding. Finally, as most of the sample were White British, the results from this sample may not be generalized to other cultural groups.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is one of the first to use a longitudinal dyadic design with individuals attending memory clinics, so that the actor and partner effects of loneliness, social isolation, and mental health status can be explored. The study used accepted measures to assess relevant constructs and applied multivariable statistical methods.

The findings from this investigation have several implications, particularly in the context of pandemic‐related disruption of normal social relationships. It is crucial to screen for loneliness and social isolation in people with cognitive disorders, even if assessments are being conducted remotely. Loneliness and social isolation predicted depression and anxiety among individuals with cognitive disorders and their care partners in the current investigation. There are many useful tools for rapidly and accurately assessing loneliness and social isolation that could become part of clinical intake data.

5. CONCLUSION

MAS attendees and their care partners who experience loneliness and social isolation are at increased risk of developing mental health problems 12 months later. Crucially, MAS attendees’ loneliness was predictive of the mental health status of their care partners at the 12‐month follow‐up, highlighting the importance of addressing loneliness and social isolation at the point of presentation to services, to obviate poor mental health outcomes of all involved. MAS services are ideally placed to undertake this important role in supporting the mental well‐being of both their own attendees as well as the wider community.

Supporting information

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all the staff of the Project CYGNUS and Jack Wilkenson. This work was funded by Innovate UK [Grant number 102159].

Maharani A, Zaidi SNZ, Jury F, Vatter S, Hill D, Leroi I. The long‐term impact of loneliness and social isolation on depression and anxiety in memory clinic attendees and their care partners: A longitudinal actor–partner interdependence model. Alzheimer's Dement. 2022;8:e12235. 10.1002/trc2.12235

REFERENCES

- 1. Maharani A, Pendleton N, Leroi I. Hearing Impairment, Loneliness, Social Isolation, and Cognitive Function: longitudinal Analysis Using English Longitudinal Study on Ageing. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019; 27: 887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O'Luanaigh C, O'Connell H, Chin AV, et al. Loneliness and cognition in older people: the Dublin Healthy Ageing study. Aging Ment Health. 2012; 16: 887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rafnsson SB, Orrell M, d'Orsi E, et al. Loneliness, social integration, and incident dementia over 6 years: prospective findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020; 75: 887–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holt‐Lunstad J, Smith TB. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for CVD: implications for evidence‐based patient care and scientific inquiry. Heart. 2016; 102: 887–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, et al. Social isolation, loneliness, and all‐cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013; 110: 887–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lundqvist L‐O, Carlsson F, Hilmersson P, Juslin PN. Emotional responses to music: experience, expression, and physiology. Psychology of Music. 2009; 37(1): 61–90. 10.1177/0305735607086048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2010; 40: 887–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Influences on loneliness in older adults: a meta‐analysis. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2001; 23: 887–896. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ong AD, Uchino BN, Wethington E. Loneliness and health in older adults: a Mini‐Review and Synthesis. Gerontology. 2016; 62(4): 443–449. 10.1159/000441651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Valtorta N, Hanratty B. Loneliness, isolation and the health of older adults: do we need a new research agenda? J R Soc Med. 2012; 105: 887–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vatter S, Stanmore E, Clare L, et al. Care burden and mental ill health in spouses of people with Parkinson disease dementia and Lewy body dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2020; 33: 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leroi I, McDonald K, Pantula H, et al. Cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease: impact on quality of life, disability, and caregiver burden. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2012; 25: 887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gerst‐Emerson K, Jayawardhana J. Loneliness as a public health issue: the impact of loneliness on health care utilization among older adults. Am J Public Health. 2015; 105: 887–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017; 390: 887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Banerjee S. Living well with dementia—development of the national dementia strategy for England. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010; 25: 887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chung JCC. Activity participation and well‐being of people with dementia in long‐term—care settings. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health. 2004; 24(1): 22–31. 10.1177/153944920402400104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gomes M, Pennington M, Wittenberg R, et al. Cost‐effectiveness of Memory Assessment Services for the diagnosis and early support of patients with dementia in England. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2017; 22: 887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cook WL, Kenny DA. The Actor‐Partner Interdependence Model: a model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. Int J Behav Dev. 2005; 29: 887–896. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marais L, Grootoonk S, Leroi I, Hall J, Hill DL. Feasibility of Real World Continuous Data Collection From Patients with Cognitive Impairment and Their Caregivers. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 2016. 12: 480‐P480 (abstract P1‐198).

- 20. Ackerman RA, Ledermann, T , Kenny DA Power analysis for the actor‐partner interdependence model. Unpublished manuscript 2016; Retrieved from https://robert‐ackerman.shinyapps.io/APIMPowerR/

- 21. Johnston C, Liddle J. The Mental Capacity Act 2005: a new framework for healthcare decision making. J Med Ethics. 2007; 33: 887–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013; 310: 2191–2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996; 66: 887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, et al. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population‐based studies. Res Aging. 2004; 26: 887–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Snaith R. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003; 1: 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ledermann T, Macho S, Kenny DA. Assessing mediation in dyadic data using the actor‐partner interdependence model. Struct Equat Model. 2011; 18: 887–896. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modelling. 3rd ed.. Guilford publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barg FK, Huss‐Ashmore R, Wittink MN, et al. A mixed‐methods approach to understanding loneliness and depression in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006; 61: S329‐S339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alpass FM, Neville S. Loneliness, health and depression in older males. Aging Ment Health. 2003; 7: 887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. O'Sullivan R, Burns A, Leavey G, et al. Impact of the Covid‐19 Pandemic on Loneliness and Social Isolation: a Multi‐Country Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. Sep 23; 18(19): 9982. 10.3390/ijerph18199982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Beeson R, Horton‐Deutsch S, Farran C, et al. Loneliness and depression in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer's disease or related disorders. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2000; 21: 887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hanby MF, Barraclough M, McKie S, Hinvest N, McDonald K, et al. Emotional and cognitive processing deficits in people with parkinson's disease and apathy. J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism. 2014; 4: 156. 10.4172/2161-0460.1000156 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leroi I, Perera N, Harbishettar V, Robert PH. Apathy and Emotional Blunting in Parkinsons disease. Brain Disord Ther. 2014; 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Teichmann M, Daigmorte C, Funkiewiez A, et al. Moral emotions in frontotemporal dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019; 69: 887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SUPPORTING INFORMATION