Summary

Development of a new dug is a very lengthy and highly expensive process since only preclinical, pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and toxicological studies include a multiple of in silico, in vitro, in vivo experimentations that traditionally last several years. In the present review, we briefly report some examples that demonstrate the power of the computer-assisted drug discovery process with some examples that are published and revealing the successful applications of artificial intelligence (AI) technology on this vivid area. Besides, we address the situation of drug repositioning (repurposing) in clinical applications. Yet few success stories in this regard that provide us with a clear evidence that AI will reveal its great potential in accelerating effective new drug finding. AI accelerates drug repurposing and AI approaches are altogether necessary and inevitable tools in new medicine development. In spite of the fact that AI in drug development is still in its infancy, the advancements in AI and machine-learning (ML) algorithms have an unprecedented potential. The AI/ML solutions driven by pharmaceutical scientists, computer scientists, statisticians, physicians and others are increasingly working together in the processes of drug development and are adopting AI-based technologies for the rapid discovery of medicines. AI approaches, coupled with big data, are expected to substantially improve the effectiveness of drug repurposing and finding new drugs for various complex human diseases.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Computer-assisted drug discovery, Drug repositioning, Machine learning, DSP-1181

Introduction

The developments in drug discovery have changed the practice of medicine tremendously that converting once fatal diseases into a kind of routine therapeutic exercises. One reason of this medicinal advancement has been an enhancement in the methods of developing and testing new drugs. A new drug usually does not imitate an existing drug in chemical structure that necessitates the discovery of a new molecule (Katzung et al. 2019).

The new molecules are mostly found by the public sector as universities and research centers while the development of a new medicine, is usually done by industrial laboratories due to the requirement of very expensive chemicals, pharmacologic and toxicological screening and thorough testing. Due to these obstacles, therefore, the recent advancements are ascribed to the pharmaceutical industry as a pharma with its multibillion dollar corporation that is devoted to drug development and marketing. Development of a new dug is very lengthy and highly expensive process since only, preclinical, pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and toxicological studies include a multitude of in silico, in vitro, in vivo experimentations that traditionally last in average 4 years. The further potential drug is subjected to a series of experimentation and characterization known as drug screening. A variety of biologic assays at the molecular, cellular, organ, and whole animal levels are used to define the activity and selectivity of the drug. Naturally, the type and number of initial screening tests depend on the pharmacologic goal. For instance, anti-infective drugs should be tested first against a number of infectious organisms, hypoglycemic drugs for their ability to lower blood sugar, etc. Nevertheless, the molecule is usually studied for a broad array of actions to establish the specificity of the drug. This kind of testing demonstrates the toxic effects. In addition, this may reveal a previously unsuspected beneficial therapeutic action. The selection of molecules for further study is usually conducted in animal models of human disease. These very lengthy and very expensive procedures have to be modified and if possible to be simplified. Here lies the importance of artificial intelligence (AI) technology in drug development that is demonstrated by its present and the potentials of future applications.

The present article is not intended to cover all the current applicability of AI in new drug development that is a highly sophisticated process. This process needs usually highly trained teams that are setup by a pharma including medicinal chemists, pharmacologists, toxicologists, computer experts and many other specialists in clinical area. The aim of the present article is, therefore, to briefly provide few published examples, that reveal the power of the computer-assisted drug discovery process to demonstrate the successful applications of AI technology in this important and vital area. Moreover, we address the situation of drug repositioning (repurposing) in clinical applications through the use of AI technology.

The present status of artificial intelligence in drug development

Machine intelligence that is known as artificial intelligence, is the intelligence exhibited by computers. In particular, AI is any technique that allows computers to mimic the human brain, and can be used throughout the drug discovery and development process. AI in information synthesis refers to applications directly involved in drug development optimization by analyzing clinically relevant data that guide the discovery of new potential targets. AI in drug design can be used to create and optimize the molecular structure of potential drugs. Besides, an important step in drug design is understanding how the precise shapes of proteins determine their functions in health, and dysfunction in the case of disease. Two recent research articles reported on the use of AI approaches for predicting the three-dimensional structure of proteins in record time, based solely on their one-dimensional amino acid sequences (Baek et al. 2021, Jumper et al. 2021). This innovative approach will extremely facilitate basic research, and guide drug developers in designing safer and more effective ways to treat and prevent disease.

Finally, AI is used to help organize, optimize, operate, and acquire patients for clinical trials often paired with more effective patient monitoring during clinical trials, or medical devices accessing individual patient data and informing medical decisions (Balfour 2020, Zhavoronkov et al. 2020). Moreover, it is now possible to deploy AI methods to support healthcare research and services, for example, risk-based guidance with deep-learning-models used for predicting avoidable hospital readmissions (Zhavoronkov et al. 2020).

Historically, the rational drug discovery applied various machine intelligence approaches to guide conventional experiments, that are time consuming and consequently expensive. Over the past several decades, computer tools, such as quantitative structure-activity relationship modeling, were developed that can identify potential biological active molecules from great numbers of candidate compounds quickly and cheaply. Thereafter, when drug discovery moved into the era of ‘big’ data, machine learning (ML) approaches evolved into the so-called deep learning approaches, which are powerful and efficient way to deal with the massive amounts of data generated from modern drug discovery approaches (Zhang et al. 2017, Lamberti et al. 2019).

As mentioned earlier in this article, the new drug discovery is a complicated, expensive, time-consuming, and challenging project. Around 12 years in average of continuous research with estimated 2.7 billion USD are needed for a new drug discovery via conventional drug development pipeline (Hinkson et al. 2020, Cui et al. 2020). The reduction of research cost and speeding the development process of a new drug, therefore, has become an urgency, for the benefit of both drug makers and for the patients as well. Hence, computer-aided drug discovery has emerged as a powerful and promising technology with the hope of faster, cheaper, and more effective drug design. According to Schneider et al. (2020) the efficient growth of computational methods for various drug discovery, has exhibited a very important role in drug design, and has also provided fruitful insights into various aspects of pharmacotherapy. In other words, through the application of AI tools, which are increasingly adopted in drug discovery and development, potentially valuable results are expected (Schneider et al. 2020).

The drug DSP-1181 created using artificial intelligence enters clinical trials

As reported, DSP-1181 is the first such drug created using AI that enters clinical trials. Exscientia, which developed DSP-1181 in partnership with Japan's Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, pointed that it had taken less than 12 months from initial screening to the end of preclinical testing as contrasted to 4 years using conventional methods (Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma 2020). It is indeed amazing difference in speeding up the development of a new drug, thanks to optimizing AI in the pharmaceutical industry. The developers of DSP-1181 announced that it has entered a Phase I clinical trial for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). OCD is an anxiety disorder. If one lives with OCD, he/she will usually have obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors. DSP-1181 is a long-acting, potent serotonin 5-HT1A receptor agonist. Exscientia’s sophisticated AI drug discovery technologies combined with Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma’s deep experience in monoamine G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) drug discovery, allowed to work synergistically, delivering a highly successful outcome. The two companies continue to work hard to make this clinical study a success so that it may deliver new benefits to patients as soon as possible. In fact, the entry of DSP-1181, created using AI, into clinical studies represent an important milestone in drug discovery. This project’s rapid success was through the strong alignment of the integrated knowledge and experiences in chemistry and pharmacology on monoamine GPCR drug discovery (Balfour 2020, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma 2020).

Artificial intelligence yields new antibiotic

An AI model identifies a powerful new drug that can kill many species of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The computer model, which can screen more than a hundred million chemical compounds in a matter of days, is designed to pick out potential antibiotics that kill bacteria using different mechanisms than those of existing drugs.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) researchers used a ML algorithm to identify a drug called halicin that kills many strains of bacteria. Halicin prevented the development of antibiotic resistance in E. coli. In laboratory tests, the drug killed many of the world’s most problematic infectious disease-causing bacteria, including some strains that are resistant to all known antibiotics. It also cleared infections in two different mouse models.

Barzilay and Collins, faculty co-leads for MIT’s Abdul Latif Jameel Clinic for Machine Learning in Health, are the senior authors of the study, which was published last year in Cell (Stokes et al. 2020a, Stokes et al. 2020b). In this study, the authors found that E. coli did not develop any resistance to halicin during a 30-day treatment period and the researchers plan to pursue further studies of halicin, working with a pharmaceutical company or nonprofit organization, in hopes of developing it for use in humans.

Artificial intelligence in defining the mechanism of drug toxicity: the example of terbinafine toxicity

The antifungal terbinafine may produce in certain patients liver damage with very bad health consequences. The reason behind terbinafine hepatotoxicity was explained by a metabolite known as TBF-A. Physicians monitor and manage this potential toxicity during treatment taking the necessary precautions. How TBF-A is formed in the liver was not known for sometimes and even it was not possible to synthesize TBF-A in the laboratory. Then, in 2018, a graduate student Na Le Dang at Washington University in St. Louis used a ML algorithm to work out the possible biochemical pathways that terbinafine takes when it is biotransformed by the liver (Barnette et al. 2018). With the necessary information to the ML algorithm, the student was able to identify that the metabolism of terbinafine to TBF-A was a two-step process (Barnette et al. 2019).

The pathways that lead to bioactivation using computational and experimental approaches with modeling were reported (Hughes et al. 2021). The article describes in detail the events of bioactivation to reactive metabolites that lead to interaction with macromolecules and consequently toxicity. Interesting enough that the bioactivation model describes both metabolism and reactivity and enables drug candidates to be quickly evaluated for a toxicity risk that is not observable during preclinical trials. Such model is very valuable and unique of being incorporating drug biotransformation and possible toxicity (Hughes et al. 2021).

Artificial intelligence and machine learning-aided drug discovery in central nervous system diseases

Due to the numerous neurological disorders, the development of drugs in the central nervous system (CNS) disorders is a challenging area. With the rapid growth of biomedical data that enabled by advanced experimental technologies, AI and ML have emerged as an indispensable tool to draw meaningful insights and improve decision making in drug discovery. Due to the advancements in AI and ML algorithms, now the AI/ML-driven solutions have an unprecedented potential to accelerate the process of CNS drug discovery with better success rate (Vatansever et al. 2020). The last authors efficiently reviewed the present status of AI/ML-powered pharmaceutical discovery efforts and their implementations in the CNS area. They focused on the current state-of-the-art of AI/ML-guided CNS drug discovery with concern on blood-brain barrier permeability prediction and implementation into therapeutic discovery for neurological diseases (Vatansever et al. 2020).

What is new in malaria drug treatment? Development of potent antiplasmodials using artificial intelligence

As with the situation of chemotherapeutic agents, antimalarial drugs are becoming less effective due to the emergence of drug resistance which has been reported for all available anti-malaria drugs, including the natural product artemisinin (Arshadi et al. 2020). Therefore, developing of alternative drug candidates is necessary. AI utilizing various models has demonstrated highly accurate performances in the field of chemical property prediction. The AI model would learn patterns within the data and help to search for hit compounds efficiently. The authors of this work introduced DeepMalaria, a deep-learning based process capable of predicting the anti-Plasmodium falciparum inhibitory properties of compounds using their SMILES (The Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System). A graph-based model is trained on 13,446 publicly available antiplasmodial hit compounds from GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) dataset that are currently being used to find novel drug candidates for malaria. Experiments reveal that the compounds' mechanism of action has shown that not only does one of the hit compounds, DC-9237, inhibits all asexual stages of Plasmodium falciparum, but is a fast-acting compound which makes it a strong candidate for further research (Arshadi et al. 2020).

Drug repurposing (repositioning) through artificial intelligence technology

Drug repositioning represents an excellent opportunity to offer more pharmaceutical candidates to the patient with established postmarketing surveillance safety data, toxicity, and pharmacokinetics profile. Repurpose drugs that have already been approved by the regulatory authorities, would speed up the process of actually translating these molecules to the clinic (Attia et al. 2020). AI has huge potential to enhance and accelerate drug discovery in more than one direction. While scientists use AI in a major way to guide and speed up the discovery of new drugs it is distinguished from the use of AI to repurpose drugs as in the exploitation of AI in COVID-19 drug repurposing (Zhou et al. 2020).

Drug repurposing has become a promising approach because of the opportunity for reduced development timelines and overall costs. In the big data era, AI and network medicine offer the most advanced application of information science to defining disease, medicine, therapeutics, and identifying targets with the least error. The application of AI for accelerating drug repurposing or repositioning, demonstrates that AI approaches are not just formidable but are also necessary. As discussed by Zhou et al. (2020) about the use of AI models in precision medicine, AI models can accelerate COVID-19 drug repurposing.

Generally, the application of AI in pandemic control has shown great potential in various ways, including predicting epidemic trend, patient tracking, stratifying asymptomatic patients, and finding potential repurpose drugs. According to Islam et al. (2021) all of the studies had a lack of sample size, and external validation and inappropriate model evaluation; therefore, using these findings would be an optimistic decision. In their excellent review, the authors recommended that more studies are needed to assess the actual effectiveness of AI models and calculate the cost effectiveness in clinical practice. They concluded that to get the real taste of AI to fight COVID-19, it is essential to reduce the false positive and negative rate as well as to disclose the ‘black-box’ nature of AI (Islam et al. 2021). Therefore, there is a long way to have good news in this direction.

Examples of the clinical significance of artificial intelligence in cancer treatment

Rapidly developing, powerful, and innovative AI and network medicine technologies can give a push to therapeutic development (Attia et al. 2020). Recently, scientists successfully trained a group of ML algorithms to rank clinically relevant cancer drug based on the drugs predicted efficacy in reducing cancer cell growth. The study suggested that ML may soon be widely used to predict the most appropriate treatment for individual patients with cancer (Gerdes et al. 2021).

Moreover, AI is being used in CyberKnife® treatment in oncology. The example mentioned here is not about an innovative drug treatment but rather an innovative radiotherapy for several types of cancers. Therefore, we feel that it is imperative to briefly hint about this very efficient technology related to cancer treatment. In fact, we have to just mention it in this place due to its high importance in implicating the use of AI with robotics for radiotherapy. It is indeed an ingenious development in the war against cancers with the following advantages as radiation treatment of being non-surgical and non-invasive, good cancer control, significantly reduced incidence of common side effects such as shortness of breath, swallowing difficulties or a sore throat. Treatments are typically completed in as little as 3 to 5 sessions across 1 to 2 weeks and most patients can continue normal activity throughout treatment, it is an amazing great technology in cancer treatment.

Concluding remarks

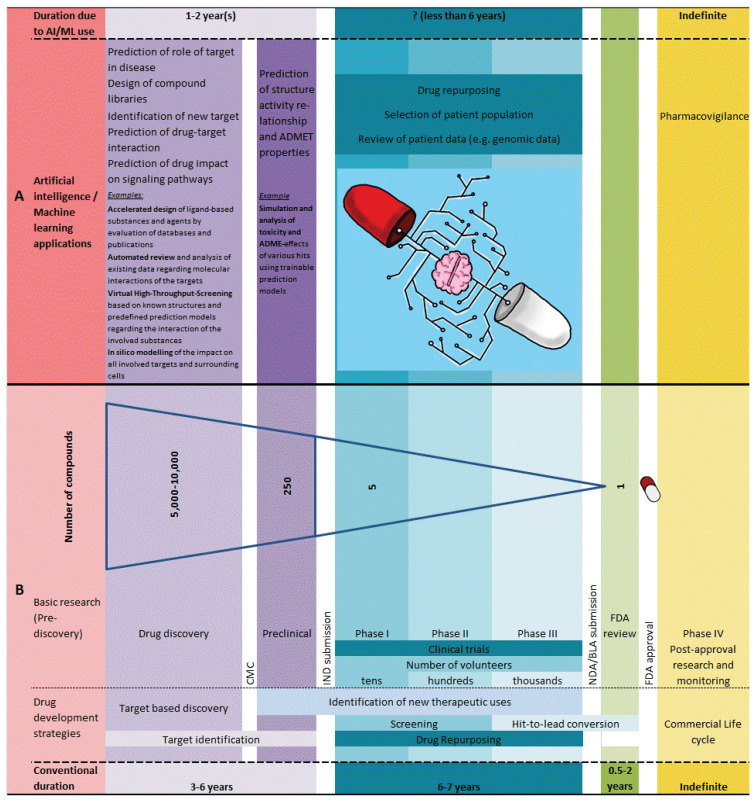

The reduction of research costs and speeding the development process of a new drug has become an urgency for the benefits of both drug makers and for the patients as well. The evolution of machines or AI now provides a guide for early-stage drug design and discovery in the current big data era. At present the success stories in this regard provide us with the clear evidence that AI really will reveal its great potential in accelerating effective new drug finding. Moreover, AI accelerates drug repurposing or repositioning and altogether, AI approaches are necessary and inevitable tools in new medicine development. Figure 1 demonstrates the possible applications of AI/ML in drug discovery and development (A) as compared to conventional methods (B). Thanks to the advancements in AI and ML algorithms where the AI/ML-driven solutions that have an unprecedented potential with pharmaceutical scientists, computer scientists, statisticians, physicians and others are increasingly working together in harmony in the processes of drug development and adopting AI-based technologies for the rapid discovery of therapeutics. AI approaches, coupled with big data, are expected to substantially improve the effectiveness of drug repurposing and finding new drugs for various complex human diseases, such as COVID-19, cancers, Alzheimer's disease etc.

Fig. 1.

Possible applications of artificial intelligence / machine learning (AI/ML) in drug discovery and development (A) as compared to conventional methods (B). ADMET: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity; BLA: Biologics License Application; CMC: Chemistry, Manufacturing, Controls; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; IND: Investigational New Drug Application; NDA: New Drug Application.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Charles University institutional project Progress Q25 and grant SVV 260 523. The authors would like to thank Anna Kutinová for helping with the Figure design.

Footnotes

This paper is dedicated to the 70th anniversary of the founding of Physiologia Bohemoslovaca (currently Physiological Research)

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- ARSHADI AK, SALEM M, COLLINS J, YUAN JS, CHAKRABARTI, DEEPMALARIA D. Artificial Intelligence Driven Discovery of Potent Antiplasmodials. Front Pharmacol. 2020;10:e1526. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATTIA YM, EWIDA H, AHMED MS. Chapter 8 - Successful stories of drug repurposing for cancer therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. In: KWK TO, WCS CHO, editors. Drug Repurposing in Cancer Therapy. Academic Press, Elsevier Inc. All; 2020. pp. 213–229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- BAEK M, DIMAIO F, ANISHCHENKO I, DAUPARAS J, OVCHINNIKOV S, LEE GR, WANG J, CONG Q, KINCH LN, SCHAEFFER RD, MILLÁN C, PARK H, ADAMS C, GLASSMAN CR, DEGIOVANNI A, PEREIRA JH, RODRIGUES AV, VAN DIJK AA, EBRECHT AC, OPPERMAN DJ, SAGMEISTER T, BUHLHELLER C, PAVKOV-KELLER T, RATHINASWAMY MK, DALWADI U, YIP CK, BURKE JE, GARCIA KC, GRISHIN NV, ADAMS PD, READ RJ, BAKER D. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science. 2021;373:871–876. doi: 10.1126/science.abj8754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BALFOUR H. DSP-1181: drug created using AI enters clinical trials. European Pharmaceutical Review – News on 4 February DSP-1181, 2020: drug created using AI enters clinical trials. europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com .

- BARNETTE DA, DAVIS MA, DANG NL, PIDUGU AS, HUGHES T, SWAMIDASS SJ, BOYSEN G, MILLER GP. Lamisil (terbinafine) toxicity: Determining pathways to bioactivation through computational and experimental approaches. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018;156:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2018.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNETTE DA, DAVIS MA, FLYNN N, PIDUGU AS, SWAMIDASS SJ, MILLER GP. Comprehensive kinetic and modeling analyses revealed CYP2C9 and 3A4 determine terbinafine metabolic clearance and bioactivation. iochem Pharmacol. 2019;170:e113661. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2019.113661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUI W, AOUIDATE A, WANG S, YU Q, LI Y, YUAN S. Discovering Anti-Cancer Drugs via Computational Methods. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:e733. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GERDES H, CASADO P, DOKAL A, HIJAZI M, AKHTAR N, OSUNTOLA R, RAJEEVE V, FITZGIBBON J, TRAVERS J, BRITTON D, KHORSANDI S, CUTILLAS PR. Drug ranking using machine learning systematically predicts the efficacy of anti-cancer drugs. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):e1850. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22170-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HINKSON IV, BENJAMIN M, STAHLBERG EA. Accelerating therapeutics for opportunities in medicine: a paradigm shift in drug discovery. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:e770. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUGHES TB, FLYNN N, DANG NL, SWAMIDASS SJ. Modeling the Bioactivation and Subsequent Reactivity of Drugs. Chem Res Toxicol. 2021;34(2):584–600. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.0c00417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISLAM MM, POLY TN, ALSINGLAWI B, LIN MC, HSU MH, LI YJ. A state-of-the-art survey on artificial intelligence to fight COVID-19. J Clin Med. 2021;10(9):1961. doi: 10.3390/jcm10091961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JUMPER J, EVANS R, PRITZEL A, GREEN T, FIGURNOV M, RONNEBERGER O, TUNYASUVUNAKOOL K, BATES R, ŽÍDEK A, POTAPENKO A, BRIDGLAND A, MEYER C, KOHL SAA, BALLARD AJ, COWIE A, ROMERA-PAREDES B, NIKOLOV S, JAIN R, ADLER J, BACK T, PETERSEN S, REIMAN D, CLANCY E, ZIELINSKI M, STEINEGGER M, PACHOLSKA M, BERGHAMMER T, BODENSTEIN S, SILVER D, VINYALS O, SENIOR AW, KAVUKCUOGLU K, KOHLI P, HASSABIS D. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATZUNG BG, KRUIDERING-HALL M, TREVOR AJ. Drug screening. In: WEITZ M, BOYLE PJ, editors. Katzung & Trevor's pharmacology: Examination & board review. Twelth edition. McGraw-Hill Education; New York, USA: 2019. pp. 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- LAMBERTI MJ, WILKINSON M, DONZANTI BA, WOHLHIETER GE, PARIKH S, WILKINS RG, GETZ K. A study on the application and use of artificial intelligence to support drug development. Clin Ther. 2019;41:1414–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHNEIDER P, WALTERS WP, PLOWRIGHT AT, SIEROKA N, LISTGARTEN J, GOODNOW RA, FISHER J, JANSEN JM, DUCA JS, RUSH TS, ZENTGRAF M, HILL JE, KRUTOHOLOW E, KOHLER M, BLANEY J, FUNATSU K, LUEBKEMANN C, SCHNEIDER G. Rethinking drug design in the artificial intelligence era. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19:353–364. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STOKES JM, YANG K, SWANSON K, JIN W, CUBILLOS-RUIZ A, DONGHIA NM, MACNAIR CR, FRENCH S, CARFRAE LA, BLOOM-ACKERMANN Z, TRAN VM, CHIAPPINO-PEPE A, BADRAN AH, ANDREWS IW, CHORY EJ, CHURCH GM, BROWN ED, JAAKKOLA TS, BARZILAY R, COLLINS JJ. A deep learning approach to antibiotic discovery. Cell. 2020a;181:475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STOKES JM, YANG K, SWANSON K, JIN W, CUBILLOS-RUIZ A, DONGHIA NM, MACNAIR CR, FRENCH S, CARFRAE LA, BLOOM-ACKERMANN Z, TRAN VM, CHIAPPINO-PEPE A, BADRAN AH, ANDREWS IW, CHORY EJ, CHURCH GM, BROWN ED, JAAKKOLA TS, BARZILAY R, COLLINS JJ. A deep learning approach to antibiotic discovery. Cell. 2020b;180:688–702.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUMITOMO DAINIPPON PHARMA. Integrated Report. Research & Development. Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd; 2020. Major products under development (as of July 30, 2020) – DP-1181. Value Chain; pp. 43–50. https://www.ds-pharma.com/ir/library/annual/pdf/2020/eng114.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- VATANSEVER S, SCHLESSINGER A, WACKER D, KANISKAN HU, JIN J, ZHOU MM, ZHANG B. Artificial intelligence and machine learning-aided drug discovery in central nervous system diseases: State-of-the-arts and future directions. Med Res Rev. 2020;41:1427–1473. doi: 10.1002/med.21764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG L, TAN J, HAN D, ZHU H. From machine learning to deep learning: progress in machine intelligence for rational drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today. 2017;22:1680–1685. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHAVORONKOV A, VANHAELEN Q, OPREA TI. Will Artificial Intelligence for Drug Discovery Impact Clinical Pharmacology? Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;107:780–785. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHOU YD, WANG F, TANG J, NUSSINOV R, CHENG FX. Artificial intelligence in COVID-19 drug repurposing. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2:E667–E676. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30192-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]