Abstract

We present the first population pharmacokinetic analysis of quinine in patients with Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Ghanaian children (n = 120; aged 12 months to 10 years) with severe malaria received an intramuscular loading dose of quinine dihydrochloride (20 mg/kg of body weight). A two-compartment model with first-order absorption and elimination gave post hoc estimates for pharmacokinetic parameters that were consistent with those derived from non-population pharmacokinetic studies (clearance [CL] = 0.05 liter/h/kg of body weight; volume of distribution in the central compartment [V1] = 0.65 liter/kg; volume of distribution at steady state = 1.41 liter/kg; half-life at β phase = 19.9 h). There were no covariates (including age, gender, acidemia, anemia, coma, parasitemia, or anticonvulsant use) that explained interpatient variability in weight-normalized CL and V1. Intramuscular quinine was associated with minor, local toxicity in some patients (13 of 108; 12%), and 11 patients (10%) experienced one or more episodes of postadmission hypoglycemia. A loading dose of intramuscular quinine results in predictable population pharmacokinetic profiles in children with severe malaria and may be preferred to the intravenous route of administration in some circumstances.

Although quinine is one of the oldest drugs in the pharmacopoeia, the optimum usage of quinine in children with severe malaria is still debated (12, 29). The choice of route and dose of quinine for children with severe malaria will vary depending on circumstances and particularly on the capability of administering intravenous infusions reliably. Quinine is the drug of choice for the management of severe malaria in most areas of the world, and it is frequently deployed in conditions where intravenous infusions cannot be rapidly established or reliably monitored.

Recent pharmacokinetic studies using African children have revived the intramuscular route as an alternative, cheaper, practicable, and potentially safer route for quinine administration (15, 25, 27). However, classical pharmacokinetic studies are not always applicable to populations at highest risk of death from Plasmodium falciparum infection. One of the most important risk factors that identify these children is the complication of lactic acidosis (plasma or whole blood lactate concentration of ≥5 mmol/liter) (11). Dichloroacetate (DCA) is a potential treatment for malaria-associated lactic acidosis (7).

We recently conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation to test the hypothesis that treatment with the lactate-lowering drug DCA, given with quinine, significantly improved morbidity and mortality in Ghanaian children with lactic acidosis due to severe P. falciparum malaria infection. This report describes the population pharmacokinetics of a loading dose of intramuscular quinine dihydrochloride (20 mg/kg of body weight) in 120 patients. The size of this study also allows assessment of covariables that may be important in influencing quinine kinetics. The major clinical results of the study will be presented elsewhere.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

The study was carried out at the Komfo-Anokye Teaching Hospital in Kumasi, Ghana, and was approved by the Committee of Research, Publication and Ethics of the School of Medical Sciences, University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana, and the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida. Between June 1997 and February 1999, 1,654 children with a suspected case of malaria were referred to the study team. Patients were examined by a member of the team, and samples were taken to measure glucose or lactate (100 μl of whole blood or plasma), hematocrit, and parasitemia. After written, informed consent from parents or guardians was obtained, children were entered into this study if they fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: age of 12 months to 10 years inclusive, positive blood film for asexual stages of P. falciparum, and plasma venous or capillary blood lactate concentration of ≥5 mmol/liter. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, assessed by a urine β-human chorionic gonadotropin test in patients aged 10 years, and brain death, determined by clinical examination. Cerebral malaria was defined using the Blantyre Coma Score (BCS) (≤2 on a 5-point scale) (16). A lumbar puncture was performed on all patients with coma (BCS ≤ 2) to exclude the possibility of meningitis or encephalitis. The cerebrospinal fluid was analyzed immediately by microscopy and cultured.

Quinine and DCA treatments.

Quinine (20 mg/kg as a loading dose; diluted 1:1 [vol/vol] in water for injection, giving a final concentration for quinine dihydrochloride of 150 mg/ml) (Rotomed [Rotex, Trittau, Germany] or quinine dihydrochloride [Martindale, Romford, United Kingdom]) was given to patients who had not received quinine treatment in the past 24 h. Half the loading dose was injected intramuscularly into the anterior aspect of each thigh. Maintenance doses of quinine (10 mg/kg, intramuscularly) were given into alternate thighs every 12 h (after dilution as before) until the patient was able to tolerate oral quinine. Patients were randomized to receive either DCA, 50 mg/kg formulated in 100 mg/ml as described previously (22), or normal saline (as placebo) after the first dose of quinine. DCA or placebo was given as a single infusion over 10 min by manual injection timed with a stopwatch.

Supportive treatment.

Patients were managed according to published guidelines (17), and supportive therapy included the following:

(i) Correction of possible thiamine deficiency.

To correct for a possible deficiency (10), all patients received a single intramuscular dose of thiamine (100 mg; Martindale) before DCA was administered.

(ii) Prevention of hypoglycemia.

A constant infusion of glucose (3 mg/kg/min, 5% dextrose) (Intravenous Infusions Ltd., Koforidua, Ghana) was administered to minimize the risk of hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemia (capillary or venous blood glucose concentration of ≤2.2 mmol/liter) was treated with a slow infusion of 50 or 25% glucose (1).

(iii) Prevention and treatment of seizures.

All patients with cerebral malaria received phenobarbitone (7 mg/kg, intramuscularly) (28), and seizures after admission were treated with diazepam (0.3 mg/kg, intravenously).

(iv) Correction of anemia.

A blood transfusion (20 ml/kg) was given to children with a hematocrit of ≤15%, and careful attention was given to maintenance of intravascular volume.

Monitoring and sampling.

Vital signs (respiratory rate, pulse, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and temperature), BCS, hematocrit, glucose, and lactate were monitored every 4 h for 24 h after admission or more frequently, if clinically indicated. Venous blood samples (2 ml) were taken at baseline and at two time points between 0 and 12 h after the first DCA dose. Randomization of sampling times was done at 0, 10, 20, and 40 min and at 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 h after DCA administration for collection of plasma to determine blood gas, metabolite, DCA, and quinine levels. As DCA was given a few minutes after quinine, this individual time difference for each patient was accounted for in analyses. Samples were collected in heparinized tubes (15 IU; Leo Pharmaceuticals, Risborough, United Kingdom). Plasma was separated within 15 min and stored and transported frozen (<−70°C) for analysis of quinine. Thick and thin blood films were also prepared at each pharmacokinetic time point and at every 4 h after admission, up to 24 h. Thereafter, sampling was performed every 6 h until parasitemia cleared.

Analysis of quinine.

Quinine was quantified in plasma samples by a previously reported high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method (8). Briefly, plasma (100 μl) was mixed with quinidine hydrochloride (10 μl of a 200-μg/ml solution), ammonia (60 μl), and water (230 μl). To this solution, methylene chloride (500 μl) was added, and the mixture was vortexed (45 s). The two layers were separated by centrifugation (3,000 × g, 10 min). The organic layer was vortex mixed with HCl (200 μl, 0.15 M) and was centrifuged again. The upper aqueous layer was separated, and sample (5 μl) was injected and analyzed by HPLC. HPLC was performed with a Hewlett-Packard 1100 Series system (Palo Alto, Calif.) made up of a G1322A Vacuum Degasser, a G1311A quaternary pump, a G1313A autosampler, and a G1315 diode array UV-visible detector. This instrument was coupled with a Hewlett-Packard Vectra Windows NT Workstation controlling pumps and detectors. A Hewlett-Packard Hypersil BDS-C-18 column (125 by 4 mm; inside diameter, 5 μm) was used for isocratic chromatographic separation with a mobile phase consisting of acetonitrile and 1% triethylamine in water adjusted to pH 3 with o-phosphoric acid (15%:85% [vol/vol]). The flow rate was kept at 1 ml/min. Quinine and quinidine were detected at 254 nm, and retention times for quinine and quinidine were 5.2 and 4.5 min, respectively. The assay method was linear in the range of 2.5 to 40 μg of quinine/ml. The inter- and intrabatch bias and relative standard deviation were <5% at all concentrations.

Data analysis. (i) Pharmacostatistical model.

Population modeling was developed by an expectation-and-maximization algorithm (described below) using P-Pharm software (InnaPhase, Champs sur Marne, France). Expectation-and-maximization analysis is an iterative two-step process suitable for computing maximum-likelihood (ML) population estimates of primary pharmacokinetic parameters. The algorithm computes the ML estimates by (i) an expectation step (E step), in which the individual parameters in the subjects are estimated by a Bayesian approach, given the present population parameters and the individual concentration-time data, and (ii) a maximization step (M step), in which the population parameters are estimated by ML methodology given the present individual-parameter estimates. These two steps are iterated up to convergence or until the fractional changes of fixed, random, and residual error variance parameters between two consecutive iterations become less than 0.001.

In the first stage, the population parameters and random effects (interindividual variations) together with the individual posterior estimates (Bayesian estimates) were computed with the assumption that no dependency exists between the pharmacokinetic parameters and the covariates. In the second stage, the relationship between the individual posterior estimates and the potential covariates was investigated by graphical exploratory functions and a multiple, linear, stepwise algorithm. Only those covariates showing a correlation with a pharmacokinetic parameter were retained in the analysis, and the population parameters were reestimated considering the ML ratio, Akaike information criterion (AIC), and residual distribution. Inspection of results and comparison with data from patients were used to assess the goodness of fit of the model.

The two sites of quinine injection (10 mg/kg to each anterior thigh) were considered a single-depot compartment because the injections were administered almost simultaneously, and the bioavailability of intramuscular quinine was assumed to be complete (100%) (20). Demographic data and clinical admission and laboratory data were used as potential covariates to assess their relationship with derived population pharmacokinetic parameters for quinine.

(ii) Model validation.

The model was validated for standardized concentration prediction error (SCPE) and standardized parameter prediction error (SPPE) for clearance (CL), intercompartmental clearance (Q), volume of distribution in the central compartment (V1), and volume of distribution in the peripheral compartment (Vp). SCPE for each concentration was calculated using the relationship:

|

Cobs represents the observed concentrations, and SD (Cexp) represents the estimated standard deviation on the expected values computed, using all sources of random variability including residual error. For each pharmacokinetic parameter (CL and V1), the normalized SPPEs were computed as

|

Ppop is the population pharmacokinetic parameter, and SD (Ppop) is the corresponding standard deviation. To assess the posterior distribution properties of the residuals and the individual parameters, a t test was used to compare the mean of SCPE and SPPE to zero and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to compare the sampled distribution to the expected one [n (0,1)].

RESULTS

Patients.

Patients with malaria-associated lactic acidosis (n = 124) were enrolled. Sixteen patients (12.9%) died, the majority of them (11 of 16; 69%) within 24 h of admission. Demographic, clinical admission, and laboratory features of patients are summarized in Table 1. All patients had one or more defining features of severe malaria, including hyperlactatemia, cerebral malaria (n = 38; 31%), acidemia (39 of 81; 48%), or respiratory distress (n = 67; 56%). Fifteen patients who did not have cerebral malaria on admission became comatose during the first 24 h of quinine treatment. Half the patients (n = 62) were randomized to receive DCA. More detailed descriptions of these patients' clinical courses will be published elsewhere. Ninety-two patients (74%) had a history of antimalarial treatment (1 with amodiaquine, 1 with artesunate, 10 with an unspecified antimalarial, and the remainder with chloroquine).

TABLE 1.

Demographic, admission, clinical, and laboratory data of study patientsa

| Variable | Result |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 124 |

| Gender (male/female) | 72/52 |

| Age (mo) | 38.6 ± 23.3 |

| Weight (kg) | 12.3 ± 3.7 (6.6–24) |

| Incidence of cerebral malaria | 38 (31%) |

| Incidence of respiratory distress | 67 (56%) |

| Use of diazepam (no/yes)b | 85/39 |

| Use of phenobarbitone (no/yes)b | 82/42 |

| Axillary temp (°C) | 37.2 ± 1.9 (35.6–42.0) |

| Heart rate (min−1) | 146 ± 27 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths · min−1) | 48.3 ± 12.0 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 96.3 ± 18.0 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 58.8 ± 12.9 |

| Parasitemia (geometric mean [geometric SD]) | 157,860 (299,060) |

| Hematocrit (%) | 23 ± 6.2 (8–41.0) |

| Lactate (mmol/liter) | 7.5 ± 3.2 |

| Glucose (mmol/liter) | 9.8 ± 7.4 |

| Venous pH | 7.3 ± 0.1 |

| No. with pH of ≤7.3 | 39/82 (48%) |

| Venous pO2 (kPa) | 8.4 ± 4.0 |

| Venous pCO2 (kPa) | 3.8 ± 1.0 |

Data are means ± standard deviations. Ranges are included for some variables.

Administered on admission to this study.

Population modeling of quinine pharmacokinetics.

Each patient contributed 1 to 3 plasma samples, depending on the actual time of blood sampling. Five patients with a history of prior quinine pretreatment had measurable baseline quinine levels. Three patients with baseline quinine levels above 2 μg/ml (range, 6.6 to 13.4 μg/ml) and one patient without measurable quinine levels for up to 1 h after admission were excluded from the population analysis. The patient without measurable quinine survived. Another surviving patient's quinine concentration was >60 μg/ml (0.5-h sample), and this time point was also excluded from analysis. Plasma samples (n = 282) from 120 patients were available for population pharmacokinetic analysis of quinine. Based on earlier analysis and published reports (12), a two-compartment model with first-order absorption and elimination was used to develop a population pharmacokinetic model for quinine. Total CL, Q, V1, Vp, and absorption rate constant (ka) were used as the model parameters. The parameter ka was fixed at 3.5/h (absorption half-life of 12 min) (8) to arrive at reliable estimates of CL and V1. Intersubject variability in CL had a log-normal distribution, while the values for intersubject variability for Q, V1, and Vp showed normal distributions. The distribution of residual errors was best explained by a multiplicative (proportional to the observed concentration) error model.

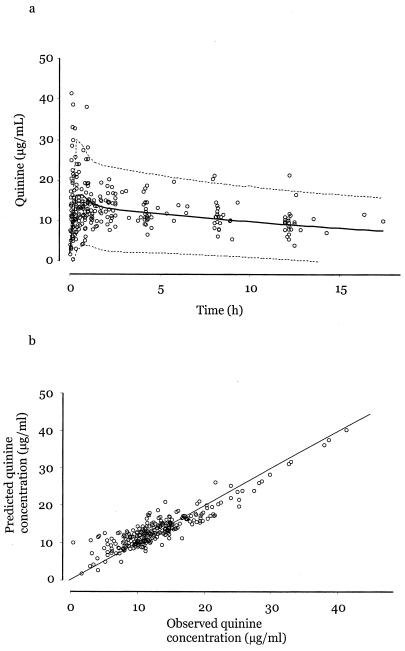

The population mean and post hoc estimates of pharmacokinetic parameters are summarized in Table 2. Figure 1a displays the base population pharmacokinetic model fitted to 282 samples obtained from patients in this study and the correlation between observed plasma quinine levels and Bayesian estimates predicted by the model. Six values for quinine lie at or above 30 μg/ml. These plasma samples were reassayed, and the initial measurements were confirmed. All these patients survived. The mean (± standard deviation) terminal elimination half-life for quinine was 19.9 ± 4.4 h. Figure 1b compares observed plasma quinine concentrations with those predicted from population modeling.

TABLE 2.

Population and posterior estimates of pharmacokinetic parameters for quinineb

| Parameter | Result for

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Population estimate (CV, %) | Post hoc estimate (CV, %) | |

| CL (liter/h/kg)a | 0.05 (73.6) | 0.05 (18.9) |

| V1 (liter/kg) | 0.65 (48.9) | 0.65 (36.4) |

| Q (liter/h/kg) | 1.12 (47.6) | 1.12 (15.4) |

| Vp (liter kg−1) | 0.764 (44.9) | 0.76 (20.6) |

| ka (h−1) | 3.5 | |

| t1/2ab (h) | 0.2 | |

| Vss (liter/kg) | 1.41 | 1.41 (19.0) |

| t1/2β (h) | 19.7 | 19.9 (22.0) |

Log normal distribution.

Vss, volume at steady state; t1/2ab, absorption half-life; t1/2β, elimination half-life; ka is fixed at 3.5. CV, intersubject variability. No covariates.

FIG. 1.

(a) Population pharmacokinetic profile with 95% confidence intervals for quinine after a single intramuscular dose (20 mg/kg). (b) Correlation between the observed quinine plasma levels and the Bayesian estimates predicted by the model.

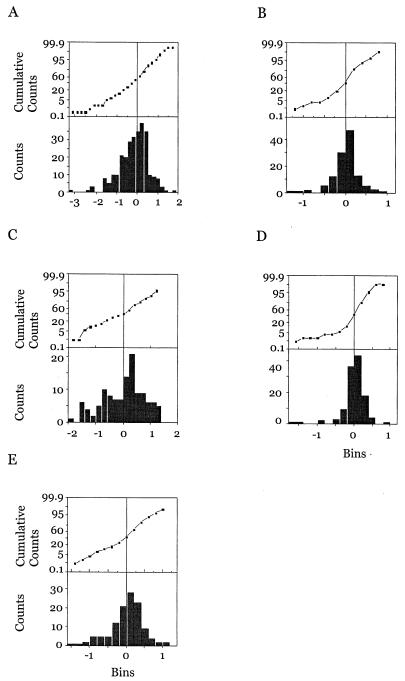

When model validation was carried out (as detailed in Materials and Methods), results showed that the distributions of the residuals and the normalized parameters were normal and not significantly different from expected. These results are represented as histograms and cumulative distribution curves in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Histograms and cumulative distribution graphs for normalized residuals (A), CL (B), V1 (C), Q (D), and Vp (E).

Analysis of covariates.

Based on a preselected critical percentage (5%) of the F distribution to assess the contribution of a covariate in multiple, stepwise, linear regression, none of the following covariates influenced weight-normalized CL and V1 : age, sex (0 = male, 1 = female), admission arterial pH, pO2, pCO2, body temperature, parasite count, cerebral malaria (0 = no, 1 = yes), phenobarbital treatment, diazepam treatment (0 = no, 1 = yes), and previous antimalarial treatment (0 = no, 1 = yes). When all of these factors were forcibly included as covariates and the data set was reanalyzed, weight, sex, age, hematocrit, and DCA (0 = placebo, 1 = DCA) treatment were selected as covariates for CL. Covariates for other parameters were weight for V1; hematocrit and cerebral malaria for Q; and cerebral malaria, DCA, and hematocrit for Vp. Intersubject variability estimates of all the parameters were lower with the covariate model (Table 3). However, there were no significant changes in the ML ratio and AIC. Analysis of the diagnostic graphs also did not indicate any improvements in the predictions. Hence, it was inferred that none of these patient-specific factors could be used reliably as covariables to explain interpatient variability in CL and V1.

TABLE 3.

| Parameter | Values for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base model

|

Covariate model

|

|||

| Mean | CV | Mean | CV | |

| CL (liter/kg/h) | 0.050 | 73.6 | 0.053 | 45.6 |

| V1 (liter/kg) | 0.650 | 48.9 | 0.598 | 48.6 |

| Q (liter/kg/h) | 1.118 | 47.6 | 1.446 | 38.5 |

| Vp (liter/kg) | 0.764 | 44.9 | 0.794 | 32.4 |

| ka (h−1) | 3.5 | 3.5 | ||

| t1/2β (h) | 19.9 ± 4.4 | 20.8 ± 11.6 | ||

| ML | −861.1 | −850.8 | ||

| AIC | 3.082 | 3.046 | ||

| Sigma | 0.912 × y | 0.848 × y | ||

Sigma, residual variability; ka, fixed at 3.5; t1/2β, half-life at β phase, estimated using post hoc parameters; y, observed concentration of quinine (Table 1); CV, intersubject variability.

Distribution models and equations: CL, log-normal distribution. CL = 0.088965 − 0.006 × weight − 0.0161 × sex + 0.0006 × age + 0.00098 × PCV − 0.0113 × cerebral + 0.0075 × DCA. V1, Q, Vp, normal distribution. V1 = 0.3158 + 0.0232 × weight. Q = 2.041 − 0.028 × PCV − 0.0949 × cerebral. Vp = 0.585 − 0.1637 × cerebral + 0.161 × DCA + 0.00883 × PCV.

Values for pH, pO2, and pCO2 were not available for 38 patients. The influence of these blood gas variables on the parameters was therefore assessed separately in a subgroup of 82 patients with all potential covariables. The base model parameters (without covariables) were similar to those for the data set containing 120 patients. In this subgroup also, none of these additional factors (pH, pO2, and pCO2) were selected as covariables. Hence, results from the complete data set with 120 patients were retained. Table 3 summarizes a model that includes covariates and goodness-of-fit parameters. There were no significant differences in estimates for pharmacokinetic parameters between survivors and fatal cases.

Efficacy and tolerability of quinine.

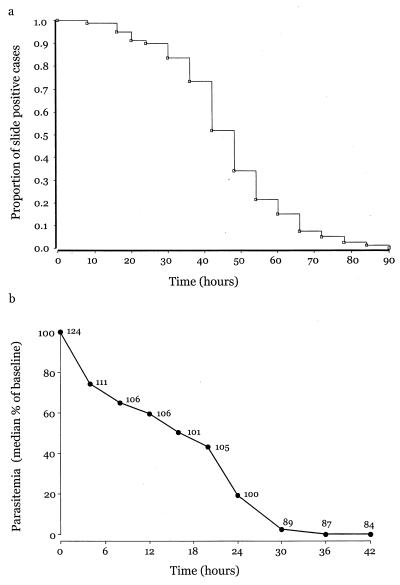

Figure 3a represents parasite CL data following quinine as a survival curve. The time taken for half the patients to clear parasites completely is 43 h. Figure 3b shows normalized parasite CL kinetics (median PC50 = 16 h and PC90 = 27 h, where PC50 is the time taken for parasite numbers to fall by 50% of baseline values and PC90 is the time required for parasite numbers to fall by 90% of baseline values). The median (interquartile range) parasite clearance time was 48 (36 to 54) h.

FIG. 3.

(a) Proportion of cases remaining positive for P. falciparum following admission. (b) Median change in parasitemia after admission. Numbers of patients contributing to each value are also given beside the data points.

Ninety-five (88%) patients from among 108 survivors had normal injection sites when discharged from the hospital. Twelve (11%) patients had mild, mainly unilateral induration, and one (1%) had unilateral swelling on discharge. Four (3%) of 68 patients who returned for follow-up examination 28 days after admission had evidence of local toxicity (two with induration and two with small [≤2 cm] fluctuant swellings). These patients were reexamined 1 to 2 weeks later, and local toxicity had resolved without specific therapy. It is not possible to attribute all local toxicity to quinine injections, as patients also received other intramuscular medication.

Hypoglycemia (blood sugar level of ≤ 2.2 mmol/liter) was present in 19 (15%) patients prior to quinine treatment. Eleven (10%) children had hypoglycemia following quinine treatment; four of these children also had admission hypoglycemia (relative risk for postadmission hypoglycemia was 3.2 [95% confidence interval = 1.02 to 9.75; P = 0.024], if there was preexisting hypoglycemia, when compared with patients who had no admission hypoglycemia).

DISCUSSION

Debate about the best way to administer quinine has continued since it was first used to treat severe malaria (12, 13, 29). Ross and others, working in India (14, 19), cautioned against using “strong” quinine solutions, because they might cause necrosis at the intramuscular injection site and might not be adequately absorbed. Diluted quinine was advocated as it was “practically painless and rapidly effective” (3). Fletcher provided a lucid review of clinical and laboratory experience on intramuscular quinine and suggested that it should be reserved for “patients who are most dangerously ill with malaria” (5). More recent studies have examined absorption of undiluted (300-mg/ml) (27) and diluted (150-mg/ml) (8) quinine and 60-mg/ml (18) quinine following a loading dose (20 mg of salt/kg). Dilution of quinine decreases the absorption half-life (mean ± standard deviation) from 38 ± 25 min to 10.4 ± 9 min (for 150-mg/ml quinine) and 8.7 ± 7.8 min (60-mg/ml quinine). There was no evidence of major local or systemic toxicity in these studies. A larger prospective evaluation of intramuscular (n = 57) versus intravenous (n = 47) quinine confirmed similar efficacy, safety, and blood levels of quinine for both routes (21) but did not include a pharmacokinetic analysis. Parasite CL estimates after quinine in our population are similar to those reported for children with cerebral malaria in The Gambia: median (with the interquartile range in parentheses) parasite CL time was 48 (36 to 54) h in our study, compared with 60 (48 to 72) h in the study from The Gambia (26).

This study on the pharmacokinetics of intramuscular quinine in children with severe malaria exceeds other reports in size and detail. Population estimates for pharmacokinetic parameters presented here are consistent with previous, smaller, classical pharmacokinetic studies. For example, quinine CL is estimated here as equal to 0.05 liter/h/kg. In previous studies, estimates ranged from 0.027 to 0.0816 liter/h/kg (reviewed in reference 12). In this study ka was fixed in order to obtain reliable estimates for other parameters. The suitability of distribution models is reflected in Fig. 1b, which shows the correlation between observed plasma concentrations of quinine and those predicted by Bayesian analysis.

Quinine (20 mg/kg) is absorbed rapidly and reliably after dilution and intramuscular injection into both anterior thighs. Mean peak plasma concentration versus time profiles between 15 and 20 μg/ml (Fig. 1a) are within the notional “therapeutic range” for quinine (12). The relatively broad confidence intervals around this value may reflect heterogeneity in quinine disposition rather than variability due to disease, as children were selected for study by strict and objective entry criteria and represent patients with the highest mortality (9, 11). The absence of any identifiable relationship between clinical and laboratory variables and population pharmacokinetic indices supports this suggestion. In particular, it is reassuring that intramuscular quinine is reliably absorbed, even in patients who may have severe acidemia, cerebral malaria, or anemia. Concomitant use of other medications (DCA, phenobarbital, and diazepam) also did not affect first-dose pharmacokinetics of quinine. Quinine is metabolized to 3-hydroxyquinine predominantly by the hepatic CYP4503A4 system (12). Since the expression of this enzyme system exhibits considerable interindividual variation (ranging from between 10 and >60% total hepatic cytochrome P450 activity) (6), genetic factors may contribute to quinine's variable disposition.

There was no major local toxicity associated with our regimen of intramuscular quinine. Local side effects were self-limiting, and none required surgical intervention, in contrast to findings from The Gambia, where some children (5 of 288) (1.7%) given intramuscular quinine (diluted 1:5) needed drainage of abscesses (26).

Patients who had hypoglycemia prior to admission were at highest risk of postadmission hypoglycemia, despite receiving a constant infusion of glucose (3 mg/kg/min). Taken together with observations on glucose kinetics in children with severe malaria receiving quinine (1), children who are hypoglycemic on admission to the hospital may require larger amounts of glucose (up to 6 mg/kg/min) than what we routinely used to prevent hypoglycemia. In any case, this high-risk group should be monitored particularly carefully. These observations are consistent with studies in Kenyan children, where admission hypoglycemia (n = 27 of 171; 16%) also identified children at risk of postadmission hypoglycemia (n = 9; relative risk = 5.33 [95% confidence interval = 2.33 to 12.2; P < 0.0001]). As in this study, some children who were euglycemic on admission subsequently developed hypoglycemia despite receiving dextrose (4). Postadmission rates of hypoglycemia were ∼15% in a large Gambian study (26). These observations contrast with those from Malawi indicating that glucose infusions prevented postadmission hypoglycemia after quinine treatment (23) and confirm that blood glucose should be monitored regularly, whenever practicable, in children with severe malaria.

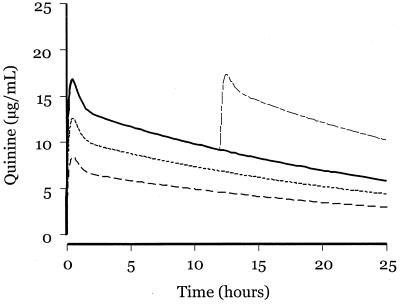

Figure 4 displays predicted quinine pharmacokinetic profiles of three different doses of quinine, based on our population analysis. Both 10- and 15-mg/kg doses are likely to undertreat a significant proportion of children in areas where parasites are not fully quinine sensitive. The safety of a 20-mg/kg loading dose of quinine and the potential for undertreatment suggest that this dose should be preferred in the management of severe malaria in African children. The risks of undertreatment with quinine were recently highlighted by a retrospective analysis that showed a significantly higher mortality rate in patients who received a 10-mg/kg dose than in those who received a 20-mg/kg dose of quinine (24). A few patients (5%) in our study had quinine levels of >30 μg/ml, but none suffered toxicity. Only one patient had levels below 5 μg/ml 12 h after the first dose of quinine. Many factors must be considered in choosing between intravenous and intramuscular routes for quinine use. Ease of administration, the lack of requirement for immediate intravenous access, more expensive fluid administration sets, predictable pharmacokinetics, usefulness in severe malaria, and safety favor the intramuscular route. However, the intramuscular route has some potential disadvantages, in particular the risk of infection (rarely tetanus or poliomyelitis) that may “seed” to areas of muscle necrosis (2, 5, 30). Both parenteral routes for quinine administration may be associated with hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia and the risk of transmitting blood-borne infections. The intravenous route incurs a risk of major quinine toxicity if infusion rates cannot be reliably managed. Thus, policies governing selection of one route over another must take into account these considerations. Our findings should increase confidence in the efficacy and safety of intramuscular quinine as the first choice for management of severe malaria in children.

FIG. 4.

Predicted pharmacokinetic profiles of four different doses of quinine based on population estimates: 20 mg/kg (——), 10 mg/kg (−−−), 15 mg/kg (--), 20 mg/kg + 10 mg/kg at 12 h (−-−).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Frank Micah, John Adabie Appiah, Cyclopea Anakwa, and Emmanuel Asafo-Agyei for patient care. Clement Opoku-Okrah and David Sambian gave technical support. We are grateful to Sister Esther Essuming and her staff for nursing care.

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health award M01 00082 to the General Clinical Research Center, University of Florida, and is part of a collaborative program for research in tropical medicine based at St. George's Hospital Medical School and funded by the Wellcome Trust. S.K. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow in Clinical Science.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agbenyega T, Angus B, Bedu-Addo G, Baffoe-Bonnie B, Guyton T, Stacpoole P, Krishna S. Glucose and lactate kinetics in children with severe malaria. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1569–1576. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.4.6529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barennes H. Intramuscular injections in sub-Saharan African children, apropos of a frequently misunderstood pathology: the complications related to intramuscular quinine injections. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1999;92:33–37. . (In French.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brodribb C. Quinine necrosis of muscle. Br Med J. 1922;ii:109. [Google Scholar]

- 4.English M, Wale S, Binns G, Mwangi I, Sauerwein H, Marsh K. Hypoglycaemia on and after admission in Kenyan children with severe malaria. QJM. 1998;91:191–197. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/91.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fletcher W. Notes on the treatment of malaria with the alkaloids of cinchona. Vol. 18. London, United Kingdom: John Bale, Sons & Danielsson, Ltd.; 1928. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzales F J, Idle J R. Pharmacogenetic phenotyping and genotyping. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1994;26:59–70. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199426010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holloway P A, Knox K, Bajaj N, Chapman D, White N J, O'Brien R, Stacpoole P W, Krishna S. Plasmodium berghei infection: dichloroacetate improves survival in rats with lactic acidosis. Exp Parasitol. 1995;80:624–632. doi: 10.1006/expr.1995.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krishna S, Agbenyega T, Angus B J, Bedu-Addo G, Ofori-Amanfo G, Henderson G, Szwandt I S F, O'Brien R, Stacpoole P W. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of dichloroacetate in children with lactic acidosis due to severe malaria. QJM. 1995;88:341–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishna S, Supanaranond W, Pukrittayakamee S, Karter D, Supputamongkol Y, Davis T M E, Holloway P A, White N J. Dichloroacetate for lactic acidosis in severe malaria: a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic assessment. Metabolism. 1994;43:974–981. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(94)90177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishna S, Taylor A M, Supanaranond W, Pukrittayakamee S, ter Kuile F, Tawfiq K M, Holloway P A H, White N J. Thiamine deficiency and malaria in adults from southeast Asia. Lancet. 1999;353:546–549. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)06316-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishna S, Waller D, ter Kuile F, Kwiatkowski D, Crawley J, Craddock C F C, Nosten F, Chapman D, Brewster D, Holloway P A, White N J. Lactic acidosis and hypoglycaemia in children with severe malaria: pathophysiological and prognostic significance. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88:67–73. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(94)90504-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishna S, White N J. Pharmacokinetics of quinine, chloroquine and amodiaquine. Clinical implications. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1996;30:263–299. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199630040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laveran A. Paludism. 1st. ed. CXLVI. London, United Kingdom: The New Sydenham Society; 1893. [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacGilchrist A C. Necrosis produced by intramuscular injections of strong solutions of quinine salts. Indian Med Gaz. 1917;lii:426–427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mansor S M, Taylor T E, McGrath C S, Edwards G, Ward S A, Wirima J J, Molyneux M E. The safety and kinetics of intramuscular quinine in Malawian children with moderately severe falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84:482–487. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molyneux M E, Taylor T E, Wirima J J, Borgstein A. Clinical features and prognostic indicators in paediatric cerebral malaria: a study of 131 comatose Malawian children. QJM. 1989;265:441–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newton C W, Krishna S. Severe falciparum malaria in children: current understanding of its pathophysiology and supportive treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;79:1–53. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasvol G, Newton C R J C, Winstanley P A, Watkins W M, Peshu N M, Were J B O, Marsh K, Warrell D A. Quinine treatment of severe falciparum malaria in African children: a randomized comparison of three regimens. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;45:702–713. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1991.45.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross R. Intramuscular injections of quinine. Lancet. 1914;i:1003–1004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shann F, Stace J, Edstein M. Pharmacokinetics of quinine in children. J Pediatr. 1985;106:506–511. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(85)80692-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shapira A, Solomon T, Julien M, Macome A, Parmar N, Ruas I, Simao F, Streat E, Betschart B. Comparison of intramuscular and intravenous quinine for the treatment of severe and complicated malaria in children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:299–302. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(93)90136-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stacpoole P W, Wright E C, Baumgartner T G, Bersin R M, Buchalter S, Curry S H, Duncan C A, Harman E M, Henderson G N, Jenkinson S, et al. A controlled clinical trial of dichloracetate for treatment of lactic acidosis in adults. The Dichloroacetate-Lactic Acidosis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1564–1569. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199211263272204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor T E, Molyneux M E, Wirima J J, Fletcher K A, Morris K. Blood glucose levels in Malawian children before and during the administration of intravenous quinine for severe falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1040–1047. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810203191602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Torn M, Thuma P E, Mabeza G F, Biemba G, Moyo V M, McLaren C E, Brittenham G M, Gordeuk V R. Loading dose of quinine in African children with cerebral malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:325–331. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(98)91032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Hensbroek B M, Kwiatkowski D, van der Berg B, Hoek F J, van Boxtel C J, Kager P A. Quinine pharmacokinetics in young children with severe malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:237–242. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Hensbroek B M, Onyiorah E, Jaffar S, Schneider G, Palmer A, Frenkel J, Enwere G, Forck S, Nusmeijer A, Bennett S, Greenwood B, Kwiatkowski D. A trial of artemether or quinine in children with cerebral malaria. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:69–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607113350201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waller D, Krishna S, Craddock C F, Brewster D, Jammeh A, Kwiatkowski D, Karbwang J, Molunto P, White N J. The pharmacokinetic properties of intramuscular quinine in Gambian children with severe falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84:488–491. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waller D, Krishna S, Crawley J, Miller K, Nosten F, Chapman D, ter Kuile F O, Craddock C F, Berry C, Brewster D, Greenwood B M, White N J. The outcome and course of severe malaria in Gambian children. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:577–587. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.3.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White N J. Controversies in the management of severe falciparum malaria. In: Pasvol G, editor. Malaria. Vol. 2. London, United Kingdom: Baillière Tindall; 1995. pp. 309–330. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yen L M, Dao L M, Day N P J, Waller D J, Bethall D B, Son L H, Hien T T, White N J. Role of quinine in the high mortality of intramuscular injection tetanus. Lancet. 1994;344:786–787. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]