Abstract

The rapid development of machine learning (ML) applications in healthcare promises to transform the landscape of healthcare. In order for ML advancements to be effectively utilized in clinical care, it is necessary for the medical workforce to be prepared to handle these changes. As physicians in training are exposed to a wide breadth of clinical tools during medical school, this offers an ideal opportunity to introduce ML concepts. A foundational understanding of ML will not only be practically useful for clinicians, but will also address ethical concerns for clinical decision making. While select medical schools have made effort to integrate ML didactics and practice into their curriculum, we argue that foundational ML principles should be taught broadly to medical students across the country.

Keywords: Machine learning, Artificial intelligence, Medical education

Medical school is formative time where students develop the knowledge and skills necessary to function as physicians in the clinical setting, which includes developing comfort with interpreting key diagnostic and prognostic tools (imaging modalities and basic lab studies) to inform treatment decisions. While the clinician’s medical knowledge has traditionally been the sole mediator between these clinical tools and medical decision-making, improvements in technology and utilization of big data via machine learning (ML) algorithms have begun to change the landscape of healthcare (Table 1; Fig. 1). Indeed, ML has been shown to outperform and provide supplemental support to clinicians in performing various diagnostic, prognostic, and treatment response predictions [1–3]. Although implementation of ML in the clinical realm is minimal at present, the number of clinical trials that include ML components has more than tripled in the last decade [4], with 80% of pathologists predicting its introduction into the clinical setting in the coming decade [5]. Moreover, the FDA recently released an action plan highlighting their expectations for ML to make significant inroads into clinical practice [6]. As clinical trial results begin to be implemented into regular clinical practice, clinicians will be challenged to augment their clinical judgement with recommendations provided by the algorithms. Given ML’s emergence as a new clinical tool, in accordance with AMA policy on Augmented Intelligence [7], we believe basic literacy in ML should be incorporated as a standard part of medical school curricula.

Table 1.

Definitions of relevant terms related to artificial intelligence used in the present article

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Artificial intelligence | The simulation of human intelligence processes by machines (e.g., self-driving cars, smart phones, automated financial investing) |

| Machine learning | A branch of artificial intelligence that is concerned with utilizing algorithms that learn to perform a task following repeated exposure to training data (e.g., image recognition, prediction, speech recognition, recommendation systems) |

| Machine learning model | A machine learning algorithm that has been trained to complete a specific task(s) |

| Augmented intelligence | The use of machine learning to enhance human intelligence, rather than operate independently or replace humans |

| Black box | An artificial intelligence system who inputs and operations are not visible or interpretable to humans |

| Explainable artificial intelligence | Artificial Intelligence system in which the rationale for the results obtained can be understood by humans, serving as an important backbone for augmented intelligence and the antithesis to the “black box” |

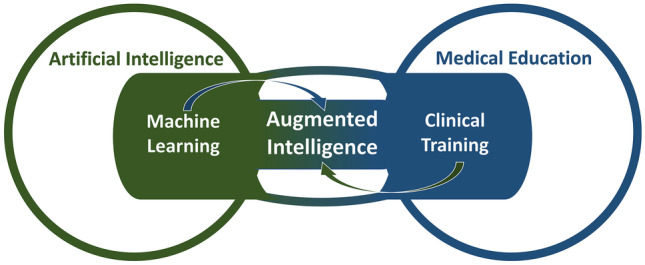

Fig. 1.

Machine learning is a branch of artificial intelligence, as is clinical training a branch of medical education. The utilization of both clinical training and additional knowledge obtained from machine learning to aid in clinical care is defined as augmented intelligence

It is not necessary that every medical student must become a computer scientist to effectively utilize machine learning in clinical practice. Clinicians interact with a host of diagnostic and prognostic tools on a daily basis without necessarily possessing expertise in the underlying mechanics of each device. Consider a frequently used clinical tool—the ultrasound. It is not the role of clinicians to design the ultrasound to use sound waves that penetrate tissue of different densities and subsequently transform these findings into a visual representation [8]. Rather, physicists and engineers develop the necessary mechanics to provide an output that can then be adopted for clinical decision making. While clinicians need not be versed in the inner workings of this device, they have a responsibility to understand the ultrasound conceptually, develop the skills to use the device, interpret its findings, and explain the informed rationale for their subsequent recommendation to the patient and their family. Similarly, in ML, while computer engineers develop and refine algorithms, future physicians need a basic understanding of the principles behind ML in order to best employ it in patient care [9].

When clinicians make decisions affecting patient care, they have an ethical responsibility to understand the rationale by which the decision is made. ML tools are intended to augment, not replace, the role of the physician and should not be relied upon to overwrite clinical judgement. A cautionary tale can be told with the history of automated EKG readings. After development in the 1960s, Medicare eventually determined that there was not a need for clinician verification of the readings [10]. These readings, however, often identified spurious noise as an abnormal rhythm while missing true abnormal rhythms, leading to incorrect diagnoses when unquestioned. In concert with interpretation by a trained clinician, however, these automated readings offer improved accuracy and safety over either method alone [10]. Likewise, clinicians will be responsible for making an informed decision through understanding the rationale of an algorithm’s output. ML has long been thought of as a “black box,” as it was formerly uncertain what factors were being weighted in predictions. Recently, however, explainable artificial intelligence techniques have been developed to provide insight into the decision process [11]. This transparency is of particular importance as biases can be unintentionally integrated into a model and inform its predictions [12]. This was made strikingly clear when an algorithm used to manage care for 200 million people in the USA was found to be less likely to refer black, rather than white, people to programs aimed at benefiting those with complex care needs [13]. Another high profile example was in the hiring realm, where a company deployed a recruiting tool that was strongly biased against women applicants, despite otherwise similar qualifications [14]. Clinicians should be trained to critically analyze the ML models they use in their practice and develop confidence to thoughtfully question a model’s output when it does not align with their clinical intuition. Medical school is an ideal time to instill a conceptual framework to approach ML applications, to develop both an appreciation of their utility and an appropriate level of caution to identify and prevent bias. Without a foundational understanding of how ML models are developed and validated for practice, however, physicians will be forced to reject the recommendations altogether or blindly accept the recommendations along with all of the associated risks.

Nonetheless, few medical schools offer any formal ML or data science course offerings, despite medical students across the globe believing artificial intelligence should be incorporated in medical training [15]. At our institution, the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine (CCLCM), an inaugural Machine Learning in Healthcare course received interest from 48% of the students in the school (n = 77, 51% female), with 65% of respondents perceiving that a foundation in ML will be useful in their career as a physician. In the subsequent year, a data science elective course offered by CCLCM received enrollment of 55% of the student body, highlighting the interest of the next generation of physicians in effectively utilizing technology in healthcare. Select medical school across the country are beginning to offer courses exploring AI in healthcare, and Harvard Medical school has developed an accelerated artificial intelligence in healthcare program for clinicians in practice [16]. Additionally, a unique new medical school, the Carle Illinois College of Medicine, specifically recruits students with an engineering focus and teaches medicine through a data science and mathematics lens, in order to train clinicians who can be innovators in application of various ML algorithms [17]. However, while opportunities for students to explore ML are increasing, these offerings are not the norm for medical school across the country.

Medical education is already overstretched, and many disciplines are unable to be covered at the depth desired by many educators [18, 19]. In considering implementing education in ML into the already overpacked medical school schedule, its addition should be approached with the same goal as its use in practice: to augment, not replace, existing coursework [9]. As such, a key focus of the training at the medical school level would be to introduce students how to work in harmony with diverse and potentially complex decision-making tools. Moreover, with the rapidly developing landscape of technology, the majority of time may not be best used learning specifics about each tool, but rather a focus on developing a basic understanding of the underlying principles, such as model training, effective implementation, and proper interpretation of model output. At the resident and attending level, the shift may rightfully focus toward utilizing the current offerings in the field in the most effective and patient-centered way.

There is little question that ML will play a principle role as healthcare adapts to the technological innovations of the day. When these changes begin to take root, it will be necessary to have a workforce of clinicians who have the skills to work in sync with these new technologies. The Association of American Medical Colleges has acknowledged the changing landscape of medicine through their initiative, “Accelerating Change in Medical Education,” with focus on the health system science and health care delivery [20]. For future clinicians to indeed be prepared to most effectively use the tools at their disposal to deliver high-quality health care, it would be prudent for medical schools to teach the fundamentals of ML and how it may influence their future role as physicians.

Author Contribution

All the authors contributed to development of the argument, drafting and editing of the manuscript, and final approval.

Funding

No funding for this work.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

NA.

Informed Consent

NA.

Conflict of Interest

Aziz Nazha, Honoraria: DCI, Consulting or Advisory Role: Karyopharm Therapeutics, Tolero Pharmaceuticals, Speakers’ bureau: Novartis, Incyte, Stock ownership: Amazon.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Steiner DF, Nagpal K, Sayres R, Foote DJ, Wedin BD, Pearce A, et al. Evaluation of the use of combined artificial intelligence and pathologist assessment to review and grade prostate biopsies. JAMA Netw Open [Internet]. 2020;3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7662146/. Accessed 5 Jan 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Buetti-Dinh A, Galli V, Bellenberg S, Ilie O, Herold M, Christel S, et al. Deep neural networks outperform human expert’s capacity in characterizing bioleaching bacterial biofilm composition. Biotechnol Rep (Amst) [Internet]. 2019;22. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6430008/. Accessed 21 Jan 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Morrow JM, Sormani MP. Machine learning outperforms human experts in MRI pattern analysis of muscular dystrophies. Neurology. 2020;94:421–422. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolachalama VB, Garg PS. Machine learning and medical education. NPJ Digital Med. Nat Publishing Group. 2018;1:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Sarwar S, Dent A, Faust K, Richer M, Djuric U, Van Ommeren R, et al. Physician perspectives on integration of artificial intelligence into diagnostic pathology. NPJ Digital Med. Nat Publishing Group. 2019;2:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Health C for D and R. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in software as a medical device. FDA [Internet]. FDA. 2021. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/software-medical-device-samd/artificial-intelligence-and-machine-learning-software-medical-device. Accessed 21 Jan 2021.

- 7.2019 Council on Medical Education. Augmented intelligence in health care: medical education, professional development and credentialing. Am Med Assoc. 2019.

- 8.Carson PL, Fenster A. Anniversary paper: evolution of ultrasound physics and the role of medical physicists and the AAPM and its journal in that evolution. Med Phys. 2009;36:411–428. doi: 10.1118/1.2992048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paranjape K, Schinkel M, Panday RN, Car J, Nanayakkara P. Introducing artificial intelligence training in medical education. JMIR Med Educ. 2019;5:e16048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Smulyan H. The computerized ECG: friend and foe. The American Journal of Medicine Elsevier. 2019;132:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amann J, Blasimme A, Vayena E, Frey D, Madai VI. Explainability for artificial intelligence in healthcare: a multidisciplinary perspective. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak [Internet]. 2020;20. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7706019/. Accessed 21 Jan 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Gianfrancesco MA, Tamang S, Yazdany J, Schmajuk G. Potential biases in machine learning algorithms using electronic health record data. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1544–1547. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019;366:447–453. doi: 10.1126/science.aax2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women | Reuters [Internet]. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-com-jobs-automation-insight/amazon-scraps-secret-ai-recruiting-tool-that-showed-bias-against-women-idUSKCN1MK08G. Accessed 2 Nov 2021.

- 15.McCoy LG, Nagaraj S, Morgado F, Harish V, Das S, Celi LA. What do medical students actually need to know about artificial intelligence? NPJ Digit Med [Internet]. 2020;3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7305136/. Accessed 5 Jan 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare Accelerated Program [Internet]. Available from: https://aihap.mgh.harvard.edu/program-info/. Accessed 21 Jan 2021.

- 17.Brouillette M. AI added to the curriculum for doctors-to-be. Nature Medicine Nature Publishing Group. 2019;25:1808–1809. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0648-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buja LM. Medical education today: all that glitters is not gold. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:110. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1535-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kollmer Horton ME. The orphan child: humanities in modern medical education. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2019;14:1. doi: 10.1186/s13010-018-0067-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skochelak SE, Stack SJ. Creating the Medical Schools of the Future. Acad Med. 2017;92:16–19. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]