Abstract

Clofibric and ethacrynic acids are prototypical pharmacological agents administered in the treatment of hypertrigliceridemia and as a diuretic agent, respectively. They share with 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (the widely used herbicide known as 2,4-D) a chlorinated phenoxy structural moiety. These aryloxoalcanoic agents (AOAs) are mainly excreted by the renal route as unaltered or conjugated active compounds. The relatedness of these agents at the structural level and their potential effect on therapeutically treated or occupationally exposed individuals who are simultaneously undergoing a bacterial urinary tract infection led us to analyze their action on uropathogenic, clinically isolated Escherichia coli strains. We found that exposure to these compounds increases the bacterial resistance to an ample variety of antibiotics in clinical isolates of both uropathogenic and nonpathogenic E. coli strains. We demonstrate that the AOAs induce an alteration of the bacterial outer membrane permeability properties by the repression of the major porin OmpF in a micF-dependent process. Furthermore, we establish that the antibiotic resistance phenotype is primarily due to the induction of the MarRAB regulatory system by the AOAs, while other regulatory pathways that also converge into micF modulation (OmpR/EnvZ, SoxRS, and Lrp) remained unaltered. The fact that AOAs give rise to uropathogenic strains with a diminished susceptibility to antimicrobials highlights the impact of frequently underestimated or ignored collateral effects of chemical agents.

Aryloxoalcanoic acids (AOAs) comprise a family of agents that include clofibric acid, the prototypical hypolipidemic fibrate from a group of pharmaceutical products administered in the treatment of hypertrigliceridemia (50); ethacrynic acid, with diuretic action by inhibition of the Na+-K+-2Cl symport at the level of the ascending limb of Henle (23), and the widely used selective herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) (18, 48). These compounds are mainly excreted by the renal route unaltered or conjugated. Therefore, they remain essentially in their active form when they reach the mammalian urinary tract (14, 23, 26, 50).

The potential effect of these AOAs on either exposed or treated patients who simultaneously undergo a bacterial urinary tract infection led us to investigate the action of these compounds on uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains. It was previously shown that 2,4-D alters hydrophobicity, fimbriation, and other envelope properties of E. coli strains (7). Interestingly, we found that exposure to AOAs induced in these uropathogenic clinical isolates an increase in the resistance to a structurally unrelated variety of antibiotics.

Resistance to antibiotics in gram-negative bacteria is due to various mechanisms that can act additively or synergistically. While some of them account for the intrinsic bacterial resistance, the expression of others is regulated in response to environmental changes. These mechanisms can be broadly classified as specific, which includes the enzymatic inactivation by hydrolysis or modification of the antibiotic and the alteration of the target of the antibiotic, and moderately specific or nonspecific, which involves the presence of permeation barriers and efflux systems that impede the access or pump out a wide variety of drugs (37, 39, 47).

Transmembrane pores composed of porin proteins are the major route for passage of a diversity of hydrophilic drugs and of exclusion of large, negatively charged, hydrophobic compounds across the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria. In E. coli, two of these major outer membrane proteins, OmpC and OmpF, function as hydrophilic diffusion channels that allow small water-soluble molecules to pass through the outer membrane permeability barrier. These proteins are highly expressed, and the rate of diffusion through the pore formed by OmpF has been measured to be approximately 10 times faster than that through the OmpC pore. By switching from the wider OmpF channel to the narrower and more restrictive OmpC channel, bacteria can modulate their permeability properties. Several environmental factors have been demonstrated to affect the expression of OmpF, including temperature, carbon source, osmolarity, oxygen stress, and the presence of salicylate, which is produced in plant tissues in response to microbial invasion. The decrease in OmpF is known to turn bacteria more resistant to antimicrobial compounds present in animals and plants and to a variety of synthetic antibiotics (38, 41).

The regulation of OmpF expression occurs at both the transcriptional and the translational levels. The osmosensitive two-component regulatory system OmpR/EnvZ modulates ompF transcriptional levels by defining the phosphorylation state of its regulator, OmpR (45). On the other hand, the antisense RNA MicF down-regulates OmpF expression, blocking its translation by forming a duplex with the ribosomal binding site of OmpF mRNA and possibly destabilizing this mRNA as well (4). The transcriptional levels of micF RNA have been demonstrated to be controlled in response to multiple environmental parameters via different regulatory pathways: SoxRS (in response to oxidative stress agents), MarRAB (induced by antibiotics, sodium salicylate, oxidative agents, and phenolic compounds), OmpR/EnvZ (responsive to osmotic changes), the leucine-responsive Lrp (up-regulated under nutrient limitation), and other less characterized mechanisms like those activated by environmental temperature changes or mediated by the DNA-binding regulator Rob (41).

In this work we found that treatment of uropathogenic E. coli strains with AOAs induces a down-regulation of the expression of the major outer membrane porin OmpF that leads to an increased antibiotic resistance. We examined the pathways that converge in the control of OmpF expression in E. coli and determined that the augmented antibiotic resistance triggered by the action of AOAs corresponds to the activation of the multiple antibiotic resistance marRAB operon in both nonpathogenic and uropathogenic strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

E. coli RM strains (listed in Table 1) were isolated from patients undergoing urinary tract infection in the Hospital Provincial del Centenario, Rosario, Argentina. These strains were typified and characterized in their antibiotic resistance pattern by conventional bacteriological methods. Strains were cultured onto blood agar plates, incubated aerobically at 37°C for 24 h, transferred to 20% glycerol broth, and stored at −70°C. Susceptibility to amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, ticarcillin, ticarcillin-clavulanic acid, cephalothin, and cefoxitin was tested by the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method (8) to determine β-lactam resistance phenotypes (22), using E. coli strains ATCC 25922 and ATCC 35218 as controls. All other E. coli strains used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains

| E. coli strain or clinical isolate | Characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| MC4100 | F−araD139 Δ(argF-lac)U169 rpsL 150 relA1 flbB5301 deoC ptsF25 rbsR | 9 |

| SM3001 | MC4100 ΔmicF Kmr | 30 |

| MH225 | MC4100 malQ7 φ(ompC::lacZ) 10-25 | 20 |

| MH513 | MC4100 araD+ φ(ompF::lacZ) 16-13 | 21 |

| MH610 | MC4100 araD+ φ(ompF::lacZ) 16-10 | 21 |

| SB221 | MC4100 (pmicB21) φ(micF::lacZ) | 33 |

| B177 | MC4100 zdd-230::Tn9 Cmr Δmar | 16 |

| B177-F | B177 φ(micF::lacZ) | This work |

| B160 | MC4100 Δsox-8::cat Δ(soxRS) | 32 |

| B160-F | B160 φ(micF::lacZ) | This work |

| LP64 | MC4100 ompR::Tn10 | 42 |

| LP64-F | MC4100 ompR::Tn10 φ(micF::lacZ) | This work |

| DL1784 | MC4100 Δlrp | 49 |

| DL1784-F | DL1784 φ(micF::lacZ) | This work |

| SPC105 | MC4100 marOII::lacZ promoter II | 13 |

| B247 | MC4100 φ(soxS′::′lacZ) Apr Kmr | 32 |

| Clinical isolates | ||

| RM11 | β-Lactam sensitive | This work |

| RM11-F | RM11 φ(micF::lacZ) | This work |

| RM 4549 | TEM-1-type producer | This work |

| RM 4549-F | RM 4549 φ(micF::lacZ) | This work |

| RM 19591 | TEM-1-type overproducer | This work |

| RM 19591-F | RM 19591 φ(micF::lacZ) | This work |

| RM 11-S | RM 11 φ(soxS′::′lacZ) | This work |

| RM 11-O | RM 11 marOII-lacZ promoter II | This work |

| RM 19591-S | RM 19591 φ(soxS′::′lacZ) | This work |

| RM 19591-O | RM 19591 marOII-lacZ promoter II | This work |

Chemicals and growth media.

Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) were obtained from Difco Laboratories (Detroit Mich.), chloramphenicol was purchased from Calbiochem, Novabiochem Corporation (La Jolla, Calif.), norfloxacin was obtained from Laboratorios Bagó (Buenos Aires, Argentina), and cefotaxime, cephalothin, trimethoprim, tetracycline, rifampin, o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside, sodium N-lauroyl sarcosinate (Sarkosyl), ethacrynic acid, clofibric acid, 2,4-D, and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.).

MIC determination.

The broth dilution method, performed in accordance with the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) (36) in MHB without cation supplementation, was used for MIC determination with a final inoculum of 105 CFU of exponentially growing cells/ml. The MIC was determined after 18 h of aerobically growing the strains at 37°C. The MIC endpoint was the lowest concentration of antibiotic that completely visibly inhibited the growth. One millimolar 2,4-D, clofibric acid, or ethacrynic acid was added to growth media when indicated.

Preparation of outer membrane fractions.

Bacterial outer membrane fractions were prepared by the Sarkosyl solubilization method described by Lambert (28). Briefly, strains were grown aerobically 24 h in LB (or LB supplemented with 1 mM 2,4-D, clofibric acid or ethacrynic acid, when indicated), harvested by centrifugation, and washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (NaCl, 8 g/liter; KCl, 0.2 g/liter; KH2PO4, 0.2 g/liter; Na2HPO4 · 2H2O, 2.9 g/liter, pH 7.4) at 4°C. Bacterial pellets were suspended in 5 ml of distilled water, and cells were disrupted by 10 30-s pulses of sonication in an ice bath, with 30-s intervals for cooling. Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was mixed with 0.5 ml of 22% (wt/vol) sodium N-lauroyl sarcosinate (Sarkosyl). After incubation for 30 min at room temperature, the mixture was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 45 min. The pellet was washed twice, resuspended in distilled water, and stored at −70°C. Protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Bio-Rad), using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Outer membrane samples were analyzed by electrophoresis using 12% polyacrylamide denaturing gels containing 8 M urea (34). Samples were mixed with an equal volume of denaturing buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% [wt/vol] SDS, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, 1% [vol/vol] β-mercaptoethanol) and boiled for 2 min prior to electrophoresis. Fifteen micrograms (for outer membrane samples from the RM 19591 strain) or 20 μg (for all other outer membrane samples analyzed) of total protein was loaded into each well. Gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 in methanol-water-acetic acid (50:40:10) and destained in water-methanol-acetic acid (83:10:7).

Beta-galactosidase assays.

For beta-galactosidase assays, overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 and grown aerobically to exponential phase in LB broth at 37°C (with the addition of 1 mM 2,4-D, clofibric acid, or ethacrynic acid when indicated). Beta-galactosidase activities were determined by adapting the method described by Miller (31) to a microassay, in a final volume of 200 μl, using an MRX microplate reader (Dynatech Laboratories). The same procedure was carried out when urine was used as the growth medium: urine was collected under aseptic conditions and assayed for the absence of bacteria by plating an aliquot of 0.1 ml onto blood agar plates.

Transduction assays.

Phage λ lysates and transductions were carried out as described previously (44). Strain SB221 was used as the donor strain to transduce the micF::lacZ gene fusion, B247 was the donor strain for the soxS′::′lacZ gene fusion, and SPC105 was the donor strain for the marOII::lacZ gene fusion.

RESULTS

Exposure to AOAs affects the antibiotic resistance profile of E. coli strains isolated from urinary tract infection.

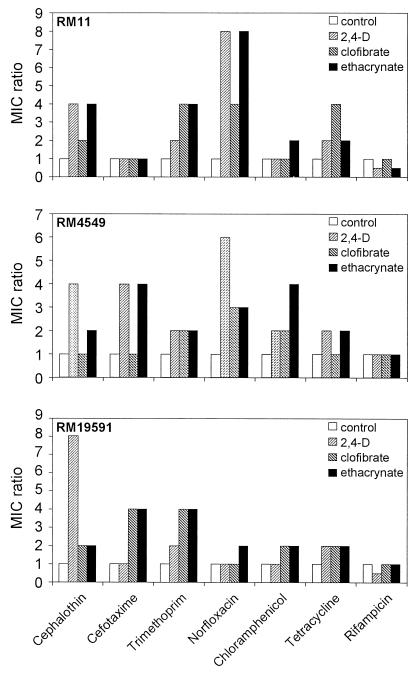

In order to determine the influence on the bacterial treatment of AOAs in the antibiotic resistance profile of clinically isolated uropathogenic E. coli strains, we determined the variation of the MICs for bacteria grown in MHB in the presence of 1 mM 2,4-D, 1 mM clofibric acid, or 1 mM ethacrynic acid relative to the values obtained in the absence of these compounds (Fig. 1). Each compound was initially tested at different concentrations to determine the amount that produced optimal induction without inhibiting bacterial growth. We used a final concentration of 1 mM for each individual compound in the growth medium because this value is within the concentration range that is present in the mammalian urinary tract in experimentally treated animals (25, 27, 43). Addition of a 1 mM concentration of each individual AOA did not show any detrimental effect either on the growth rate or in the final optical density reached by the tested strains. Fig. 1 shows the effect of AOAs in the antibiotic susceptibility profile of three different uropathogenic E. coli clinical isolates selected on the basis of their resistance to beta-lactams (RM11, sensitive; RM4549, TEM-1-type beta-lactamase producer; and RM 19591, TEM-1-type beta-lactamase overproducer; the “TEM-1-type” phenotype comprises TEM-1, TEM-2, and SHV-1, which cannot be distinguished on the basis of resistance patterns) (22). The analysis of the data revealed that incubation with AOAs increased the antibiotic resistance from two- to eightfold (with the only exception being the resistance to rifampin), which reflected the magnitude of the effect dependent on the strain, the antibiotic, and the AOA tested. Because the mode of action of the antibiotics tested was unrelated, the observed variability pointed out that AOAs are triggering a mechanism that results in a nonspecific augmented resistance against a broad range of antibiotics.

FIG. 1.

Effect of aryloxoalcanoic compounds on the antibiotic susceptibility profile of uropathogenic E. coli isolates. Values are expressed as the ratio of MICs determined in the presence and absence of each AOA. The data correspond to the mean values of at least three independent assays.

It is worth mentioning that the absolute MIC values obtained in the beta-lactamase overproducer strain RM 19591 exposed to AOAs rendered a clinically meaningful increase in the level of resistance to cephalothin (80 to 320 mg/liter).

AOA treatment represses OmpF in a micF-dependent manner.

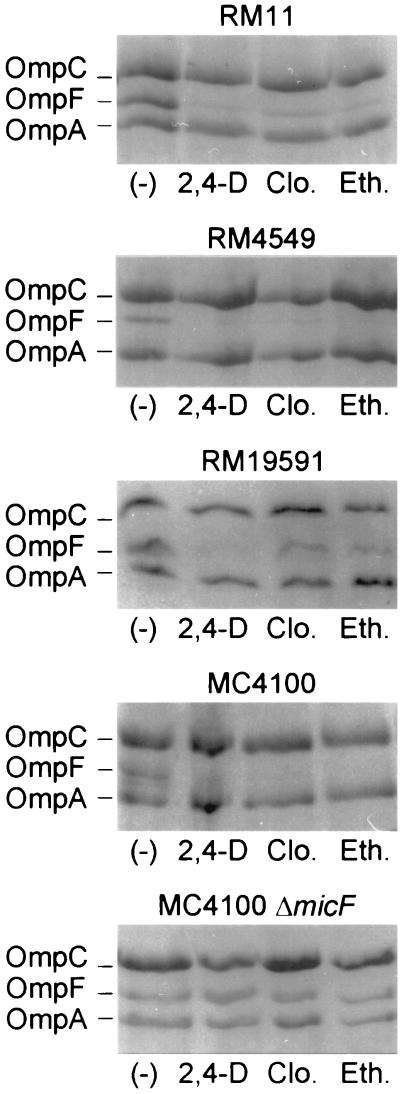

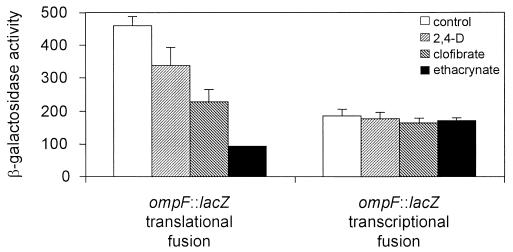

The above results were suggestive of an alteration in the permeability barrier of the cells. To explore this possibility we first examined the profile of the outer membrane porins in the E. coli uropathogenic strains and in the nonpathogenic strain MC4100 grown in the presence of the AOAs. Figure 2 shows that the AOA treatment dramatically reduced OmpF expression in all strains tested while OmpC expression remained unaltered (compare RM11, RM4549, and RM19591 with the MC4100 protein profile). Similar results were obtained for other clinical E. coli uropathogenic isolates (C. Balagué, N. Sturtz, R. Rey, C. Silva de Ruiz, M. E. Nader-Macías, R. Duffard, and A. M. Evangelista de Duffard, Biocell, vol. 24, suppl. 1–84, abstr. 164, 2000). This result suggests that the down-regulation of OmpF is not operated via the modulation of the phospho-OmpR concentration that would reciprocally control the level of both porins in response to environmental osmolarity (35). On the other hand, a deletion in micF that encodes the antisense RNA MicF abolished the observed repression of OmpF, indicating that the treatment with AOAs was affecting OmpF expression in a micF-dependent manner (Fig. 2, compare MC4100 with MC4100 ΔmicF). Since the antisense MicF RNA is involved in the posttranscriptional negative regulation of ompF, we tested the effect of AOAs on ompF expression at the transcriptional and at the translational levels. Figure 3 shows that AOAs reduced LacZ expression from a translational fusion of lacZ to ompF while the beta-galactosidase activity from a transcriptional fusion to lacZ remained essentially unchanged. Additionally, we determined that AOAs did not induce ompC expression at the transcriptional level (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Effect of aryloxoalcanoic compounds on the porin profile of uropathogenic and nonpathogenic E. coli strains. Strains were grown in LB broth without (−) or with the addition of 1 mM 2,4-D, 1 mM clofibric acid (Clo.), or 1 mM ethacrynic acid (Eth.). Outer membrane fractions from E. coli strains were analyzed by SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with the addition of 8 M urea, and the gel was stained with Coomassie blue as described in Materials and Methods. RM strains correspond to E. coli uropathogenic clinical isolates (all strains used are listed in Table 1).

FIG. 3.

Effect of aryloxoalcanoic compounds on the expression of OmpF. Beta-galactosidase activity was measured for strains MH610 and MH513 harboring ompF::lacZ translational and transcriptional fusions, respectively. Assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The bars represent the means of three independent determinations + the standard deviations of the means.

The induction of antibiotic resistance is due to the repression of OmpF.

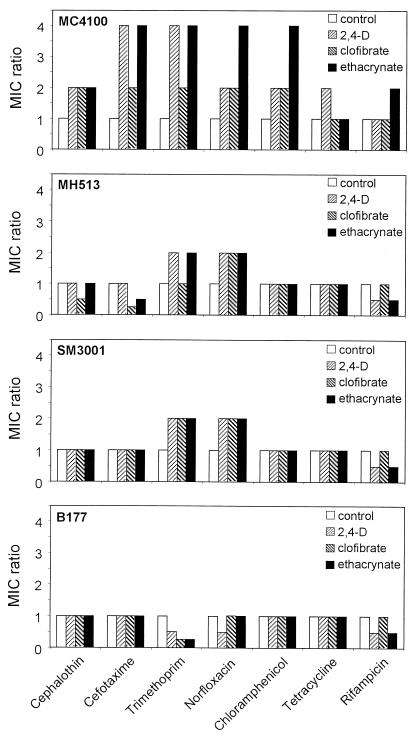

We next investigated if the repression of OmpF was the cause for the increased antibiotic resistance. We compared the effect of the treatment with AOAs on the induction of antibiotic resistance using the MC4100 nonpathogenic strain and isogenic mutants in ompF (MH513) or in micF (SM3001) (Fig. 4). For MC4100, the relative increase in the MIC values ranged from two- to fourfold, depending on the AOA and the antibiotic tested, while these effects were either completely abolished (for cephalothin, cefotaxime, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, and rifampin) (for MH513 the absolute MIC values equal the maximal resistance achieved by MC4100 induced by AOAs, while for SM3001 they equal the basal levels of MC4100 in the absence of the compounds) or partially reduced (for trimethoprim and norfloxacin) in the mutant strains. These results indicate that, as previously observed for the clinical uropathogenic isolates, the AOAs exert an inducing effect on the antibiotic resistance in the nonpathogenic E. coli strain MC4100 that relies entirely on the micF-mediated repression of ompF, with the exception of trimethoprim and norfloxacin.

FIG. 4.

Effect of aryloxoalcanoic compounds on the antibiotic susceptibility profile of nonpathogenic strain MC4100 and its isogenic mutants in ompF (MH513), micF (SM3001), or mar (B177) loci. Values are expressed as the ratio of MICs determined in the presence and absence of each AOA. The data correspond to mean values of at least three independent assays.

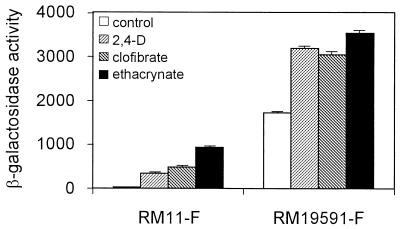

To test if the same pathway was triggered in the clinical isolates, we measured the beta-galactosidase activity from the uropathogenic strains RM11 and RM19591 harboring the transduced micF-lacZ transcriptional fusion (Fig. 5). Indeed, we found that the beta-galactosidase activity from the bacteria treated with AOAs was augmented, with the greatest effect corresponding to the treatment with ethacrynic acid in all the strains tested. Thus, OmpF down-regulation correlated with an enhanced micF transcription in the nonpathogenic as well as in the uropathogenic E. coli strains upon treatment with AOAs.

FIG. 5.

Effect of aryloxoalcanoic compounds on the expression of micF in the uropathogenic E. coli isolates. Beta-galactosidase activity was measured for strains RM11-F and RM19591-F harboring the micF::lacZ transcriptional fusion. Assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The bars represent the means of three independent determinations + the standard deviations of the means.

Interestingly, identical values of micF induction were obtained when the E. coli strains challenged with the AOAs were grown in urine instead of LB broth (data not shown).

AOAs activate the marRAB operon.

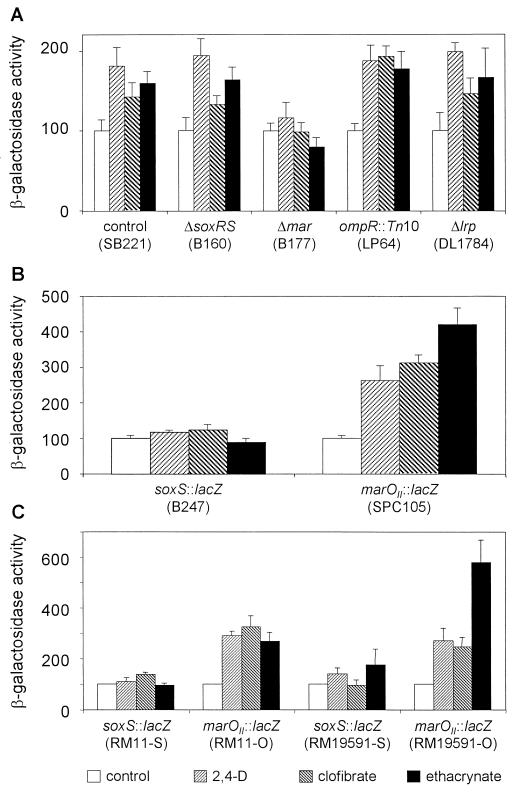

In light of the numerous pathways that converge into the transcriptional modulation of micF in response to distinct environmental cues (41), we decided to investigate which route(s) was involved in the mechanism promoted by AOAs. The best characterized paths that control the transcriptional levels of MicF depend on the activity of the marRAB operon, the osmo-sensitive two-component system OmpR/EnvZ, the oxidative stress-activated SoxRS system, and the leucine-responsive transcriptional regulator Lrp (4, 10, 15, 24). Figure 6A shows the beta-galactosidase activity from the micF-lacZ transcriptional fusion in MC4100 and in MC4100-derived mutants in each individual pathway when incubated in the absence or presence of AOAs. The induction of micF upon treatment with AOAs was abolished only when the Δmar mutant was used, while the activation profile remained essentially unchanged when we used the otherwise isogenic Δ(soxRS), ompR::Tn10, or Δlrp strain. This result reveals that the up-regulation of micF promoted by the AOAs depends on the activity of the marRAB operon.

FIG. 6.

Effect of aryloxoalcanoic compounds on the regulatory pathways that control micF expression. Beta-galactosidase activity was measured for (A) E. coli SB221 and the MC4100-derived mutant strains in soxRS (B160), mar (B177), ompR (LP64), or lrp (DL1784) harboring the micF::lacZ transcriptional fusion; (B) E. coli MC4100 harboring soxS::lacZ (B247) or marOII::lacZ (SPC105) transcriptional fusions; and (C) E. coli uropathogenic isolates RM11 and RM19591 harboring the soxS::lacZ or marOII::lacZ transcriptional fusions. Assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The bars represent the means of three independent determinations + the standard deviations of the means.

Transcription from marRAB is normally negatively autoregulated by the MarR repressor that binds to regions within marO, the promoter/operator region of the operon. MarR repression has been demonstrated to be alleviated upon exposure to a wide variety of compounds (1, 2, 24, 46) and results in the elevated expression of MarA, the master activator of the regulon (12, 24). Using an MC4100 derivative strain, SPC105, that harbors a lacZ fusion to the marOII promoter, we determined that the three AOAs tested increased the transcriptional activity from the marO regulatory region (Fig. 6B). Because MarA and SoxS are highly homologous to each other and they can both stimulate the transcription from the so-called mar/sox boxes (present in micF) (5, 32), we also measured the transcriptional activity from a soxS::lacZ transcriptional fusion, corroborating that this system is not simultaneously induced by the action of the AOAs. We next investigated if the AOAs up-regulated the marRAB operon in the uropathogenic strains, as it was above demonstrated for MC4100. Figure 6C shows that in the clinical E. coli isolates RM11 and RM19591, the induction of micF transcription upon exposure to AOAs also correlated with the up-regulation of the marRAB (but not the soxRS) operon. Finally, we tested the effect of the AOAs on antibiotic resistance when using the Δmar mutant strain B177. Figure 4 (compare MC4100 with B177) shows that the relative increase in the MIC values is abolished when the mar operon is not functional.

DISCUSSION

The development of new pharmacological agents has a profound and sometimes unpredictable or underestimated effect on the acquisition of bacterial resistance to antibiotics. An acquired resistance phenotype either can imply a modification in the bacterial genome due to the persistence of an environmental selection pressure or can be the result of a reversible, adaptive response to the circumstantial presence of an external agent.

The ethacrynic and clofibric acids (as the prototype structures of the diuretics that act on the ascending limb of Henle and the hypolipidemic fibric acids, respectively) also share basic structural features with the herbicide 2,4-D, which is used worldwide and to which rural or forestry workers are overexposed in developing countries due to improper use of protective procedures. Ethacrynic acid and 2,4-D are compounds derived from phenoxyacetic acid, while clofibric acid derives from phenoxypropionic acid. The three compounds exhibit a common chlorinated phenoxy moiety and are substrates for the organic acid transport system in the kidney, being eliminated in the urine mainly unchanged and, to a lesser extent, as conjugates (glucuronic acid conjugates in the case of clofibrate; cystein and acetyl-cystein conjugates for ethacrynic acid) (14, 23, 26, 50). This means that in the urinary tract of an exposed worker (for 2,4-D) or a patient under treatment with the mentioned pharmacological agents, opportunistic or pathogenic microorganisms are under the action of the active forms of these drugs.

The results presented in this work examine the effect of these agents on different E. coli uropathogenic strains classified on the basis of their resistance to beta-lactams. The antibiotic resistance profile showed an increase in the MICs from two- to eightfold except for the resistance to rifampin, which remained essentially unaltered. The heterogeneity of the structure and mode of action of the antimicrobial agents used and the fact that it was previously shown that 2,4-D altered envelope properties in E. coli, such as its hydrophobic index (7), indicated that AOAs induced a broad-spectrum mechanism of resistance. The lack of effect obtained when using rifampin, which presents the highest hydrophobicity among the antibiotics tested, showed that the induced resistance was effective for hydrophilic molecules.

The analysis of the outer membrane porin profile of either the clinical isolates or the nonpathogenic E. coli strain treated with AOAs consistently rendered a strong repression of the major porin OmpF. We determined that this effect corresponded to a transcriptional up-regulation of the antisense RNA micF, causing OmpF translation to be blocked. On the other hand, ompC transcriptional and translational levels remained essentially unaltered, indicating that an OmpR/EnvZ-independent mechanism was triggered. Remarkably, the AOAs promoted an identical profile of micF induction when the challenge was carried out in urine instead of LB broth, pointing out the relevance of the effect in the physiological environment encountered in the urinary tract. To define the pathways affected by AOAs that caused micF transcription to be enhanced, we screened the response to the compounds in nonfunctional mutants in the soxRS, marRAB, ompR, or lrp loci. Only the mutation located in the marRAB operon shut down the transcriptional activation of micF and abolished the induction of the multiple antibiotic resistance promoted by the three AOAs, elucidating the basis of this effect.

The marRAB operon encodes the mar repressor (MarR), the mar activator (MarA) that belongs to the XylS/AraC family of DNA-binding regulators, and a small protein, MarB, of unknown function. MarR binds to two direct repeats (sites I and II) within marO, the mar operator, preventing the transcription of the marRAB operon. MarR repression can be reversed in vivo and in vitro by the action of a variety of structurally dissimilar compounds, including antibiotics like tetracycline and chloramphenicol, weak acids, salicylate, sodium benzoate, uncoupling agents (2,4-dinitrophenol and carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone), and redox cycling compounds. This in turn up-regulates the levels of MarA that activate its own expression and the differential expression of over 60 chromosomal genes that constitute the mar regulon (1–3, 12, 24, 46). Using a marOII::lacZ fusion, we corroborated that cell exposure to the three AOAs analyzed herein triggered the transcriptional expression of the operon, with ethacrynic acid being the compound that rendered the strongest effect. The concomitant transcriptional induction from the marO operator and the up-regulation of micF were established for both MC4100 and the clinical strains exposed to AOAs, suggesting that this response is ancestral to the acquisition of pathogenic traits and that it would confer adaptive benefits to all pathogenic and nonpathogenic strains.

All the genes directly regulated by MarA present a consensus sequence recognized by MarA, the “marbox,” that is highly homologous to the “soxbox,” the cis-acting element required for the recognition of SoxS, the regulator of the oxidative stress-responsive system SoxRS. Since it has been demonstrated that there is cross-regulation between these two systems (5, 32), we also ruled out the involvement of the SoxRS system as part of this AOA-triggered response.

Reversible induction of the mar regulon in response to environmental stimulus or naturally occurring mutations within the mar locus due to the selective pressure exerted by antimicrobial compounds lead to the multiple antibiotic resistance phenotype (5, 11, 13, 19). The decreased susceptibility to an ample variety of antibiotics mediated by MarRAB is known to be accomplished mainly by decreasing the influx (down-regulating the synthesis of OmpF) and increasing the efflux of the toxic chemicals (up-regulating the AcrAB-TolC multidrug efflux system) (40). When using the ompF mutants, and accordingly in the micF mutants, we obtained a complete shutoff of the antibiotic resistance induced by AOAs except for trimethoprim and norfloxacin, where it became apparent that the action of an additional mechanism contributed to the resistance effect. This micF-independent effect was cancelled in the Δmar mutant strain, and we even detected an increased susceptibility to the above-mentioned antibiotics when the mar null strain was treated with the AOAs. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that a mar-dependent efflux mechanism, like AcrAB-TolC, is responsible for the observed additional resistance phenotype. Further analysis is required to assess the contribution of this efflux mechanism to the AOA-induced bacterial resistance to selected antibiotics. Additionally, we are currently exploring the potential involvement of regulators like Rob or Fis, MarA-like regulators that have an accessory function in the activation of the mar operon (6, 29).

It has been demonstrated that the induction of subclinical levels of antibiotic resistance is the first step towards the survival of mutants in an independent locus that displays clinically relevant antimicrobial resistance (3, 17). In this regard, we have shown that AOAs are capable of promoting antibiotic resistance, aiding the intrinsic mechanisms to achieve clinically significant levels.

Finally, this work reinforces the notion that the misuse of pharmacological agents or the underestimated occupational exposure to toxic chemicals are clearly risk factors that may undermine the success of an antibacterial treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. M. Evangelista de Duffard for helpful advice, J. L. Rosner, B. Demple, J. Liu, and D. Low for generously providing bacterial strains, and F. C. Soncini for helpful comments on the manuscript and technical assistance with the figures.

E.G.V is a Career Investigator of the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas (CONICET, Argentina). This work was supported in part by a grant from the Third World Academy of Sciences (Trieste, Italy) to E.G.V.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alekshun M N, Levy S B. Alteration of the repressor activity of MarR, the negative regulator of the Escherichia coli marRAB locus, by multiple chemicals in vitro. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4669–4672. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4669-4672.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alekshun M N, Levy S B. Characterization of MarR superrepressor mutants. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3303–3306. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.10.3303-3306.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alekshun M N, Levy S B. The mar regulon multiple resistance to antibiotics and other toxic chemicals. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:410–413. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01589-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen J, Forst S A, Zhao K, Inouye M, Delihas M. The function of micF RNA. micF RNA is a major factor in the thermal regulation of OmpF protein in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:17961–17970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ariza R R, Cohen S P, Bachhawat N, Levy S B, Demple B. Repressor mutations in the marRAB operon that activate oxidative stress genes and multiple antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:143–148. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.143-148.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ariza R R, Li Z, Ringstad N, Demple B. Activation of multiple antibiotic resistance and binding of stress-inducible promoters by Escherichia coli Rob protein. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1655–1661. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.7.1655-1661.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balagué C, Stürtz N, Duffard R, Evangelista de Duffard A M. Effect of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid herbicide in Escherichia coli growth, chemical composition and cellular envelope. Environ Toxicol. 2001;16:43–53. doi: 10.1002/1522-7278(2001)16:1<43::aid-tox50>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauer A W, Kirby W M M, Sherris J C, Turck M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966;45:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casadaban M J. Transposition and fusion of the lac genes to selected promoters in Escherichia coli using bacteriophage lambda and mu. J Mol Biol. 1976;104:541–555. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou J H, Greenberg J T, Demple B. Posttranslational repression of Escherichia coli OmpF protein in response to redox stress: positive control of the micF antisense RNA by the soxRS locus. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1026–1031. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.1026-1031.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen S P, McMurry L M, Hooper D C, Wolfson J S, Levy S B. Cross-resistance to fluoroquinolones in multiple antibiotic resistance (mar) Escherichia coli selected by tetracycline or chloramphenicol: decreased drug accumulation associated with membrane changes in addition to OmpF reduction. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1318–1325. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.8.1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen S P, Hächler H, Levy S B. Genetic and functional analysis of the multiple antibiotic resistance (mar) locus in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1484–1492. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.5.1484-1492.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen S P, Levy S B, Foulds J, Rosner J L. Salicylate induction of antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli: activation of the mar operon and a mar-independent pathway. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7856–7862. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7856-7862.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ecobichon D J. Toxic effects of pesticides. In: Klaassen C D, Amdur M O, Doull J, editors. Casarett and Doull's toxicology. The basic science of poisons. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill; 1996. pp. 643–689. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrario M, Ernsting B R, Borst D E, Wiese II D E, Blumenthal R M, Mathews R G. The leucine-responsive regulatory protein of Escherichia coli negatively regulates transcription of ompC and micF and positively regulates translation of ompF. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:103–113. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.103-113.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gambino L, Gracheck S J, Miller P F. Overexpression of the MarA positive regulator is sufficient to confer multiple antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2888–2894. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.2888-2894.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldman J D, White D G, Levy S B. Multiple antibiotic resistance (mar) locus protects Escherichia coli from rapid cell killing by fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1266–1269. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grover R, Franklin C A, Miur N I, Cessna A J, Riedel D. Dermal exposure and urinary metabolite excretion in farmers repeatedly exposed to 2,4-D amine. Toxicol Lett. 1986;33:73–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(86)90072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hachler H, Cohen S P, Levy S B. marA, a regulated locus which controls expression of chromosomal multiple antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5532–5538. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5532-5538.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall M N, Silhavy T J. Transcriptional regulation of Escherichia coli K12 major outer membrane protein 1b. J Bacteriol. 1979;140:342–350. doi: 10.1128/jb.140.2.342-350.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall M N, Silhavy T J. The ompB locus and the regulation of the major outer membrane proteins of Escherichia coli K-12. J Mol Biol. 1981;146:23–43. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90364-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henquell C, Sirot D, Chanal C, De Champs C, Chatron P, Lafeuille B, Texier P, Sirot J, Cluzel R. Frequency of inhibitor-resistant TEM β-lactamases in Escherichia coli isolates from urinary tract infections in France. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;34:707–714. doi: 10.1093/jac/34.5.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson E K. Diuretics. In: Hardman J G, Limbird L E, Molinoff P B, Ruddon R W, Goodman Gilman A, editors. Goodman & Gilman's. The pharmacological basis of therapeutics. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill; 1996. pp. 685–713. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jair K, Martin R G, Rosner J L, Fujita N, Ishihama A, Wolf R E. Purification and regulatory properties of MarA protein, a transcriptional activator of Escherichia coli multiple antibiotic and superoxide resistance promoters. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7100–7104. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7100-7104.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khanna S, Fang S C. Metabolism of C14-labelled 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid in rats. J Agric Food Chem. 1966;14:500–503. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knopp D, Glass S. Biological monitoring of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid-exposed workers in agriculture and forestry. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1991;63:329–333. doi: 10.1007/BF00381583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koechel D A, Budd G C, Bretz N S. Acute effects of alkylating agents on canine renal function and ultrastructure: high-dose ethacrynic acid vs. dihydroethacrynic acid and ticrynafen. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1984;228:799–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lambert P A. Separation and purification of surface components. Isolation and purification of outer membrane proteins from gram-negative bacteria. In: Hancock I, Poxton I, editors. Bacterial cell surface techniques (modern microbiological methods). Bath, Avon, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 1988. pp. 110–121. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin R G, Rosner J L. Fis, an accessorial factor for transcriptional activation of the mar (multiple antibiotic resistance) promoter of Escherichia coli in the presence of the activator MarA, SoxS, or Rob. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7410–7419. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7410-7419.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsuyama S, Mizushima S. Construction and characterization of a deletion mutant lacking micF, a proposed regulatory gene for OmpF synthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:1196–1202. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.3.1196-1202.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. pp. 352–355. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller P F, Gambino L F, Sulavik M C, Gracheck S J. Genetic relationship between soxRS and mar loci in promoting multiple antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1773–1779. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.8.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mizuno T, Chou M Y, Inouye M. A unique mechanism regulating gene expression: translation inhibition by a complementary RNA transcript (micRNA) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1966–1970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizuno T, Mizushima S. Isolation and characterization of deletion mutants of ompR and envZ, regulatory genes for expression of the outer membrane proteins OmpC and OmpF in Escherichia coli. J Biochem. 1987;101:387–396. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a121923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mizuno T, Mizushima S. Signal transduction and gene regulation through the phosphorylation of two regulatory components: the molecular basis for the osmotic regulation of the porin genes. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1077–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard. M7–A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nikaido H. Prevention of drug access to bacterial targets: permeability barriers and active efflux. Science. 1994;264:382–388. doi: 10.1126/science.8153625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nikaido H. Outer membrane. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Brooks Low K, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nikaido H. Multiple antibiotic resistance and efflux. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1998;1:516–523. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(98)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okusu H, Ma D, Nikaido H. AcrAB efflux pump plays a major role in the antibiotic resistance phenotype of Escherichia coli multiple-antibiotic-resistance (Mar) mutants. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:306–308. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.306-308.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pratt L A, Hsing W, Gibson K E, Silhavy T J. From acids to osmZ multiple factors influence synthesis of the OmpF and OmpC porins in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:911–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pratt L A, Silhavy T J. OmpR mutants specifically defective for transcriptional activation. J Mol Biol. 1994;243:579–594. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Price S C, Hinton R H, Mitchell F E, Hall D E, Grasso P, Blane G F. Time and dose study on the response of rats to the hypolipidaemic drug fenofibrate. Toxicol. 1986;41:169–191. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(86)90198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Provence D L, Curtiss R., III . Gene transfer in gram-negative bacteria. In: Gerardt P, Murray R G E, Wood W A, Krieg N R, editors. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1994. pp. 317–347. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Russo F D, Silhavy T J. EnvZ controls the concentration of phosphorylated OmpR to mediate osmoregulation of the porin genes. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:567–580. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90497-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seoane A S, Levy S B. Characterization of MarR, the repressor of the multiple antibiotic resistance (mar) operon in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3414–3419. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3414-3419.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spratt B G. Resistance to antibiotics mediated by target alterations. Science. 1994;264:388–393. doi: 10.1126/science.8153626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taskar P K, Das I T, Trout J R, Chattopadhyay S K, Brown H D. Measurement of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) after occupational exposure. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1982;29:586–591. doi: 10.1007/BF01669625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Woude M, Kaltenbach L S, Low D A. Leucine-responsive regulatory protein plays dual roles as both an activator and a repressor of the Escherichia coli pap operon. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:303–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17020303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Witztum J L. Drugs used in the treatment of hyperlipoproteinemias. In: Hardman J G, Limbird L E, Molinoff P B, Ruddon R W, Goodman Gilman A, editors. Goodman & Gilman's. The pharmacological basis of therapeutics. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill; 1996. pp. 875–897. [Google Scholar]