Key Points

Question

Is altered fetal brain development in the setting of maternal psychological distress associated with infant neurodevelopment?

Findings

In this cohort study of 97 mother-infant dyads who underwent 184 fetal magnetic resonance imaging studies (87 participants with 2 fetal studies each) and infant neurodevelopmental testing at 18 months, prenatal maternal stress was negatively associated with infant cognitive outcome, and this association was mediated by fetal left hippocampal volume. The study also found that increased fetal cortical local gyrification index and sulcal depth under elevated prenatal maternal distress were associated with decreased infant social-emotional scores measured by Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development and competence scores measured by Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment.

Meaning

These findings suggest that altered in vivo fetal brain development in the setting of elevated prenatal maternal psychological distress may be associated with adverse neurodevelopment.

This cohort study examines the association between infant 18-month neurodevelopment and fetal brain development using 3-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging volumes, cortical folding, and metabolites in the setting of maternal psychological distress.

Abstract

Importance

Prenatal maternal psychological distress is associated with disturbances in fetal brain development. However, the association between altered fetal brain development, prenatal maternal psychological distress, and long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes is unknown.

Objective

To determine the association of fetal brain development using 3-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) volumes, cortical folding, and metabolites in the setting of maternal psychological distress with infant 18-month neurodevelopment.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Healthy mother-infant dyads were prospectively recruited into a longitudinal observational cohort study from January 2016 to October 2020 at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, DC. Data analysis was performed from January 2016 to July 2021.

Exposures

Prenatal maternal stress, anxiety, and depression.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Prenatal maternal stress, anxiety, and depression were measured using validated self-report questionnaires. Fetal brain volumes and cortical folding were measured from 3-dimensional, reconstructed T2-weighted MRI scans. Fetal brain creatine and choline were quantified using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Infant neurodevelopment at 18 months was measured using Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development III and Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment. The parenting stress in the parent-child dyad was measured using the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form at 18-month testing.

Results

The cohort consisted of 97 mother-infant dyads (mean [SD] maternal age, 34.79 [5.64] years) who underwent 184 fetal MRI visits (87 participants with 2 fetal studies each) with maternal psychological distress measures between 24 and 40 gestational weeks and completed follow-up infant neurodevelopmental testing. Prenatal maternal stress was negatively associated with infant cognitive performance (β = −0.51; 95% CI, −0.92 to −0.09; P = .01), and this association was mediated by fetal left hippocampal volume. In addition, prenatal maternal anxiety, stress, and depression were positively associated with all parenting stress measures at 18-month testing. Finally, fetal cortical local gyrification index and sulcal depth were negatively associated with infant social-emotional performance (local gyrification index: β = −54.62; 95% CI, −85.05 to −24.19; P < .001; sulcal depth: β = −14.22; 95% CI, −23.59 to −4.85; P = .002) and competence scores (local gyrification index: β = −24.01; 95% CI, −40.34 to −7.69; P = .003; sulcal depth: β = −7.53; 95% CI, −11.73 to −3.32; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study of 97 mother-infant dyads, fetal cortical local gyrification index and sulcal depth were associated with infant 18-month social-emotional and competence outcomes, and fetal left hippocampal volume mediated the association between prenatal maternal stress and infant cognitive outcome. These findings suggest that altered prenatal brain development in the setting of elevated maternal distress has adverse infant sociocognitive outcomes, and identifying early biomarkers associated with long-term neurodevelopment may assist in early targeted interventions.

Introduction

Stress-related symptoms are now recognized as the most common complication of pregnancy, affecting approximately 1 of every 4 women, even those with healthy pregnancies and high socioeconomic status.1 Prenatal maternal stress exposure has been shown to have enduring consequences on brain development in the offspring, including altered regional brain volumetric growth (eg, amygdala, hippocampal, cerebellar, and cortical gray matter volumes), cortical folding, metabolism, microstructure, and functional connectivity,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 as well as long-term neurodevelopmental impairments (eg, cognitive, language, learning, and psychiatric dysfunctions).14,15,16,17

Neurodevelopmental problems in the setting of elevated maternal stress are thought to be associated with abnormal brain structure and circuitry.18,19 Notably, disaster-related prenatal maternal stress has been associated with larger amygdala volumes in children at 11 years old, and amygdala volume mediated the association between prenatal maternal stress and children’s externalizing problems.20 Similarly, maternal stress hormone (ie, cortisol) levels at early gestation have been associated with a larger right amygdala volume in girls at age 7 years, and amygdala volume mediated the association between prenatal maternal cortisol and children’s affective problems.8 In addition, prenatal maternal stress was associated with both reduced cortical thickness in children at age 7 years and elevated depressive symptoms at follow-up age 12 years, and children’s cortical thickness was associated with later depressive symptoms,21 suggesting a role of altered cortical thickness in the setting of prenatal maternal stress and adolescent depressive symptoms. Although a growing body of evidence links prenatal maternal stress exposure to altered brain growth and long-term neurodevelopment in the offspring, measures of in vivo fetal brain development using advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been very limited.

Exploring in utero fetal brain development is challenging because of fetal and maternal motion, imaging artifacts, signal-to-noise ratio issues, changes in morphology (due to brain growth), and changes in image intensity (due to myelination and cortical maturation). Recently, advances in in utero MRI techniques1,3,22,23 enabled us to detect early alterations in fetal brain development under stress exposure, which may forecast later neurodevelopmental problems at an early age.18 In a previous study,1 we reported for the first time that maternal stress, anxiety, or depression, even if not reaching the severity of a mental disorder, was associated with adverse fetal brain development, including impaired fetal brain choline and creatine levels and hippocampal growth, as well as accelerated cortical folding. However, it is unknown whether and how these findings of altered in vivo fetal brain development are associated with subsequent infant neurodevelopment. In this study, we expand on our prior work1 by (1) examining the association between prenatal maternal psychological distress (ie, stress, anxiety, and depression that did not reach the severity of a mental disorder1,24) and infant 18-month neurodevelopment; (2) examining the association between fetal brain development (ie, volumetric, cortical folding, and metabolic measures) and infant 18-month neurodevelopment; and (3) determining whether fetal brain development mediates the association between prenatal maternal psychological distress and infant neurodevelopment outcomes.

Methods

Study Design

We prospectively recruited pregnant women and their fetuses into a longitudinal, observational cohort study between January 2016 and October 2020. Pregnant women were healthy volunteers from low-risk obstetric clinics. Women were eligible if medical record reviews confirmed a normal prenatal medical history, without chronic or pregnancy-induced illnesses, normal screening serum values, and normal fetal ultrasonography and fetal biometry studies. We excluded fetuses with known or suspected congenital infection, dysgenetic lesions or dysmorphic features, or genetic abnormalities. We also excluded pregnant women with (1) chronic medical conditions identified at the time of screening through the medical record or by self-report of existing medical conditions during each study visit (eg, autoimmune, genetic, metabolic, or psychiatric disorders); (2) pregnancy-related complications; (3) multiple pregnancies; (4) self-reported drug abuse, smoking, and alcohol use; (5) medications for chronic conditions; and (6) contraindications to MRI. Participants identified their race from a list of options defined on the basis of the information in US Census. Race was assessed in this study to help to understand underlying contributing factors. Fetal brain MRI studies were scheduled at 2 time points between 24 and 40 weeks of gestation.

This is a follow-up study of our previous research.1 Ninety-two of 97 participants (95%) in the current study were from our previous report1 who completed the follow-up infant 18-month neurodevelopmental testing. In our previous publication,1 we reported significant associations between maternal psychological distress and specific fetal MRI-based brain measures, including volumetric growth of the hippocampus, cortical folding metrics (local gyrification index and sulcal depth), and brain metabolic measures (creatine and choline levels). We now sought to determine the association between these fetal brain measures and infant neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18 months.

This study was approved by the institutional review board at Children’s National Hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Prenatal Maternal Psychological Distress

Psychometrically sound questionnaires measuring stress, anxiety, and depression were used and completed on the same day as each fetal MRI visit. The Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS-10, range, 0-40) assesses the self-reported level of stress in the prior month.25 Total scores of 15 or higher have been suggested as indicative of elevated maternal stress.26,27 The Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory is composed of 2 self-reported measures of anxiety: state anxiety (SSAI) and trait anxiety (STAI).28 Both measures are composed of 20 items (range, 20-80). SSAI and STAI scores of 40 or higher are suggestive of presence of anxiety.29,30 The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; range, 0-30) screens depression symptoms in pregnant and postpartum women.31,32 EPDS scores of 10 or higher are suggestive of elevated depression.33,34 In this study, mothers who endorsed 1 or more measure of stress, anxiety, or depression (measured score greater than or equal to cutoff score) were referred to as positive for maternal psychological distress.

MRI Acquisition and Processing

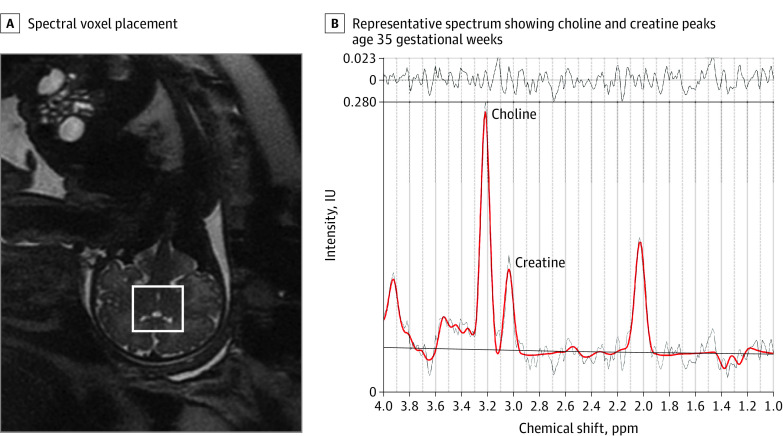

As reported in our previous study,1 fetal brain T2-weighted MRI was performed using a 1.5-Tesla magnet (GE Discovery MR450) and an 8-channel receiver coil at 2 time points between 24 and 40 weeks of gestation. The scanning protocol included multiplanar, single-shot, fast spin-echo acquisitions (repetition time, 1100 ms; echo time, 160 ms; flip angle, 90°; field of view, 32 cm; matrix, 256 × 192; 2-mm slice thickness). The acquisition time was 2 to 3 minutes for each plane. Participants were free-breathing during the scan. After acquiring the 2-dimensional (2D) brain slices from axial, sagittal, and coronal planes, a state-of-the-art motion correction technique35 that has been previously validated was used to correct the fetal brain motion and reconstruct the images from 2D slices of all 3 planes to a high-resolution 3-dimensional (3D) image (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). After that, the reconstructed brains were spatially oriented to the brain atlas36 using landmark-based rigid registration in the IRTK package.37 The oriented images with the resolution of 0.86 × 0.86 × 0.86 mm3 were used to measure brain volume and cortical folding. For 1H–magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS), a spectral voxel was placed in the center of the fetal brain to measure brain metabolites (Figure 1). More details on 1H-MRS acquisition have been reported in our previous study.1

Figure 1. Fetal Brain Metabolic Measures .

A, The spectral voxel (square) was placed in the center of a fetal brain using the anatomical image as a guidance. B, Representative spectrum shows choline and creatine peaks (parts per million [ppm]) of a fetus at 35 gestational weeks. IU indicates international units.

Brain Volume, Cortical Folding, and Metabolism

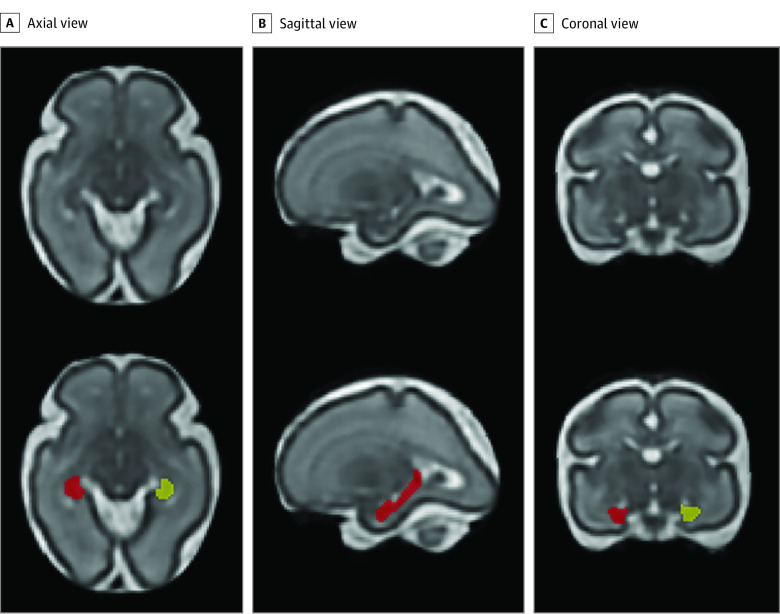

Left and right hippocampi were manually delineated on reconstructed T2-weighted MR images (Figure 2) according to previously validated anatomical criteria.38,39 An experienced neuroradiologist (G.V.) assisted with anatomical localization of the hippocampi on MR images. The manual segmentation was performed by the same rater (Y.W.), and 20% of scans were randomly selected and segmented by another experienced rater (K.K.). Interrater reliabilities using intraclass correlation coefficient were higher than 0.95. The cortical folding measures, including local gyrification index40 and sulcal depth,41 were calculated on the inner surface of cortical gray matter.1 The local gyrification index was calculated as the ratio between the cortical surface area at each vertex and the corresponding area on the cerebral hull surface,40 and sulcal depth was measured as the distance from each vertex on the cortical surface to the nearest point on the cerebral hull surface.41 For 1H-MRS data, creatine and choline measured with Cramer-Rao lower bounds less than 20% from the fetal brain were used in the analysis.1

Figure 2. Segmentation of the Hippocampus.

Left hippocampus (yellow) and right hippocampus (red) are shown on a 3-dimensional reconstructed T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of a fetus at 27.9 gestational weeks.

Infant Neurodevelopmental Testing

Measures of infant 18-month neurodevelopmental status were performed by an examiner (K.E.) blinded to clinical findings. Neurodevelopmental assessments were conducted using the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (BSID-III)42 and the Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA).43 The BSID-III evaluates cognitive, language, and motor functioning and was performed by a licensed psychologist (K.E.). The BSID-III Social-Emotional Scale measures adaptive behavior and social-emotional development via parent-completed measure. The normalized mean (SD) of each composite score is 100 (15). A mean score less than 85 indicates a developmental delay.44 The ITSEA is a parent-completed measure that evaluates child social-emotional and/or behavioral problems and delays in competence.45 The ITSEA assesses 4 domains: externalizing (activity/impulsivity, aggression/defiance, and peer aggression), internalizing (depression/withdrawal, general anxiety, separation distress, and inhibition to novelty), dysregulation (negative emotionality, sleep, eating, and sensory sensitivity), and competence (compliance, attention, mastery, motivation, imitation/play, empathy, and prosocial peer relations).43,46 Externalizing, internalizing, dysregulation scores of 65 or higher and competence domain scores of 35 or lower indicate a deficit or delay.46

Parenting Stress at 18 Months

The Parenting Stress Index–Short Form (PSI-SF)47 was used to evaluate the degree of stress in the parent-child dyad at 18-month testing. The PSI-SF is a self-reported measure of parenting stress that includes 3 subscales: parental distress, parent-child dysfunctional interaction, and difficult child.47,48 Each subscale (range, 12-60) consists of 12 items rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The PSI-SF also gives a defensive responding scale (7 items from the parental distress scale; range, 7-35) and a total stress scale (range, 36-180) that is a sum of parental distress, parent-child dysfunctional interaction, and difficult child.47,48 The PSI-SF has been validated to be effective and appropriate for measuring stress in the parent-child system in a variety of populations.49,50,51,52,53

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software version 9.3 (SAS Institute) and MATLAB statistical software version R2018b (MathWorks). Data analysis was performed from January 2016 to July 2021. Characteristics of the study sample in negative vs positive prenatal maternal psychological distress were compared using either t test or Fisher exact test, where appropriate. Infant neurodevelopmental scores in women positive on 1 or more prenatal distress measures were compared using analysis of covariance, controlling for possible confounders including maternal education and employment,54 PSI-SF total stress scale at 18 months, and neurodevelopmental assessment during COVID-19 pandemic (yes or no). Generalized estimating equations (GEEs), which allow multiple measurements for each participant, were used to measure associations between prenatal maternal psychological distress scores and infant neurodevelopmental outcomes, controlling for gestational age (GA) at the fetal visit, maternal education and employment, PSI-SF total stress scale, and neurodevelopmental assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic (yes or no). An unstructured correlation assumption was used to address the possible correlation within participants due to multiple measurements. GEE was used to determine the associations between prenatal maternal psychological distress scores and PSI-SF parenting stress scales measured at 18 months, controlling for GA at fetal visit, maternal education and employment, and neurodevelopmental assessment during COVID-19 pandemic (yes or no). GEE was also used to measure associations between fetal brain measures (volume, cortical folding, and metabolites) and infant neurodevelopmental outcomes, adjusting for prenatal maternal psychological distress status (positive or negative), GA at fetal visit, maternal education, maternal employment, PSI-SF total stress scale at 18 months, and neurodevelopmental assessment during COVID-19 pandemic (yes or no). The prenatal maternal psychological distress status was derived by combining the individual positive/negative distress measurements of participants (SSAI, STAI, PSS, and EPDS). In the combined measurement, participants were defined as positive if they had 1 or more positive individual distress measurements; otherwise, they were defined as negative. Additional adjustments for maternal body mass index, age, race, GA at birth, and birth weight were considered, with no material effect on estimates. The significance level of multiple testing was adjusted using the false discovery rate method,55 and adjusted 2-sided P ≤ .05 was considered significant. Causal mediation analyses56 were performed to assess whether fetal brain development mediated the association between prenatal maternal distress scores and infant neurodevelopment at 18 months. The direct effect of prenatal maternal distress on infant neurodevelopment and the indirect (mediating) effect of prenatal maternal distress on infant neurodevelopment through fetal brain volumes were evaluated using the following 3 models: model 1, Y = i1 + β1X + γ1C1 + e1, where β1 is the total effect of X on Y; model 2, M = i2+ β2X + γ2C2 + e2, where β2 tests the association between X and the mediator M; and model 3, Y = i3 + β3X + β4M + γ3C1+e3, where β3 is the direct effect of X on Y (X = prenatal maternal distress score, Y = infant neurodevelopment outcome, and M = fetal brain volume). C1 denotes the vector of confounding factors that include GA at the fetal visit, maternal education, maternal employment, PSI-SF total stress scale at 18 months, and neurodevelopmental assessment during COVID-19 pandemic (yes or no). C2 is a vector of confounding factors in model 2.1 If X and M and have no association in model 2, there is no ground for mediation. The mediating effect of X on Y through mediator M is the total effect in model 1 minus the direct effect in model 3 (β1 − β3). Bootstrapping (1000 samples) was used to estimate bias-corrected 95% CIs, and a significant mediating effect was defined as a bootstrapped 95% CI that did not include 0.

Results

Demographic Data

Our cohort consisted of 97 mother-fetus dyads (49 [51%] male fetuses and 48 [49%] female fetuses) who underwent 184 fetal MRI visits (87 participants with 2 fetal studies each) with maternal psychological distress measures between 24 and 40 gestational weeks and completed follow-up infant neurodevelopmental testing at 18 months. We initially enrolled 131 study participants; however, 1 participant was excluded because of an abnormal fetal MRI finding (ie, intraventricular hemorrhage). For the remaining participants, 101 completed both the prenatal MRI visits and follow-up infant neurodevelopmental testing. Four of 101 participants with missing prenatal maternal distress questionnaires were excluded. Ten of the remaining 97 participants completed the first but not the second MRI visit, resulting in 184 fetal MRI studies included in the analyses. Data from 13% of T2-weighted scans and 17% of 1H-MRS were not usable because of fetal motion. For T2-weighted MRI scans, left and right hippocampi were successfully measured on 92 fetuses (153 scans), and cortical folding was successfully measured on 80 fetuses (117 scans). For 1H-MRS scans, fetal brain choline and creatine levels were successfully analyzed on 84 fetuses (153 scans). All conventional fetal MRI scans were interpreted as structurally normal by an experienced fetal neuroradiologist (G.V.). The conventional MRI findings were shared with the study participants. The mean (SD) GA was 28.12 (2.41) weeks at the first fetal MRI and 35.95 (1.70) weeks at the second fetal MRI. The mean (SD) age at neurodevelopment testing was 19.68 (4.54) months. The mean (SD) maternal age was 34.79 (5.64) years. Ninety-one women (94%) attended college and 84 (87%) had professional employment. For maternal race, 7 women (7%) were Asian/Pacific Islander, 10 (10%) were Hispanic, 15 (15%) were non-Hispanic Black, and 60 (62%) were non-Hispanic White. All fetal MRI and prenatal maternal distress measures were performed before May 2019. Fourteen of our 97 participants completed their infant neurodevelopmental testing since the first case of COVID-19 was reported in the US on January 20, 2020. Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Overall Study Sample and by Prenatal Maternal Psychological Distress Status.

| Variable | Patients, No. (%) | P valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 97 [100%]) | Negative (n = 62 [64%]) | Positive (n = 35 [36%]) | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | ||||

| At fetal visit 1, wk (n = 97) | 28.12 (2.41) | 28.10 (2.55) | 28.20 (2.27) | .84 |

| At fetal visit 2, wk (n = 87) | 35.95 (1.70) | 35.94 (1.75) | 35.99 (1.61) | .88 |

| At neurodevelopment testing, mo (n = 97) | 19.68 (4.54) | 19.84 (4.50) | 19.39 (4.66) | .64 |

| Birth measures, mean (SD) | ||||

| Age, wk | 39.16 (1.41) | 39.09 (1.52) | 39.29 (1.19) | .49 |

| Weight, g | 3259 (512) | 3267 (518) | 3246 (510) | .84 |

| Characteristics | ||||

| Maternal age, mean (SD), y | 34.79 (5.64) | 35.18 (5.64) | 34.09 (5.65) | .37 |

| Maternal body mass index, mean (SD)b | ||||

| Fetal visit 1 | 46.19 (7.98) | 46.30 (8.63) | 45.66 (6.64) | .69 |

| Fetal visit 2 | 48.20 (7.68) | 48.14 (8.13) | 48.32 (6.69) | .91 |

| Primigravida | 38 (39) | 26 (42) | 12 (34) | .30 |

| Primipara | 51 (53) | 35 (56) | 16 (46) | .51 |

| Parental education | ||||

| Partial high school | .66 for mother; .12 for father | |||

| Maternal | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Paternal | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (3) | |

| High school | ||||

| Maternal | 3 (3) | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | |

| Paternal | 9 (9) | 5 (8) | 4 (11) | |

| Partial college | ||||

| Maternal | 8 (8) | 4 (6) | 4 (11) | |

| Paternal | 12 (12) | 11 (18) | 1 (3) | |

| College graduate | ||||

| Maternal | 26 (27) | 19 (31) | 7 (20) | |

| Paternal | 23 (24) | 13 (21) | 10 (29) | |

| Graduate degree | ||||

| Maternal | 57 (59) | 36 (58) | 21 (60) | |

| Paternal | 47 (48) | 30 (48) | 17 (49) | |

| Unknown | ||||

| Maternal | 3 (3) | 1 (2) | 2 (6) | |

| Paternal | 5 (5) | 3 (5) | 2 (6) | |

| Parental employment | ||||

| Professional | .18 for mother; .86 for father | |||

| Maternal | 84 (87) | 55 (89) | 29 (83) | |

| Paternal | 77 (79) | 51 (82) | 26 (74) | |

| Skilled/clerical/sales | ||||

| Maternal | 3 (3) | 3 (5) | 0 | |

| Paternal | 5 (5) | 3 (5) | 2 (6) | |

| Semiskilled operator | ||||

| Maternal | 2 (2) | 0 | 2 (6) | |

| Paternal | 3 (3) | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | |

| Unemployed/homemaker | ||||

| Maternal | 5 (5) | 3 (5) | 2 (6) | |

| Paternal | 6 (6) | 3 (5) | 3 (9) | |

| Unknown | ||||

| Maternal | 3 (3) | 1 (2) | 2 (6) | |

| Paternal | 6 (6) | 3 (5) | 3 (9) | |

| Maternal race and ethnicity | ||||

| American Indian or Alaskan Indian | 0 | 0 | 0 | .80 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 7 (7) | 5 (8) | 2 (6) | |

| Hispanic | 10 (10) | 8 (13) | 2 (6) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 15 (15) | 9 (15) | 6 (17) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 60 (62) | 38 (61) | 22 (63) | |

| Other or unknownc | 5 (5) | 2 (3) | 3 (9) | |

| Distribution of endorsed maternal psychological distress | ||||

| 1 | 12 (12) | NA | 12 (34) | NA |

| 2 | 8 (8) | NA | 8 (23) | |

| 3 | 9 (9) | NA | 9 (26) | |

| 4 | 6 (6) | NA | 6 (17) | |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

P value for difference between participants with negative and positive maternal psychological distress based on t test for continuous variables and Fisher exact test for categorical variables.

Body mass index is calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Other is a self-reported option that includes all other responses not included in any other race category.

Prenatal Maternal Psychological Distress Measures

Mean (SD) maternal anxiety, stress, and depression scores were 29.6 (8.9) for SSAI, 30.7 (8.6) for STAI, 10.7 (5.8) for PSS, and 4.3 (3.8) for EPDS. The distress scores across GA are shown in eFigure 2 in the Supplement. Of the 97 pregnant women, 28 (29%) were positive (measured score greater than or equal to the cutoff score) for stress, 29 (30%) for anxiety (22 [23%] for state anxiety and 19 [20%] for trait anxiety), and 10 (10%) for depression. Thirty-five women (36%) tested positive for stress, anxiety, or depression. For the 35 women who tested positive on distress measures (ie, SSAI, STAI, PSS, or EPDS), 12 (34%) of them were positive on 1 distress measure, 8 (23%) on 2 measures, 9 (26%) on 3 measures, and 6 (17%) on all 4 measures (Table 1).

Fetal Brain Volumes, Cortical Folding, and Metabolites

Mean (SD) volumes of left and right hippocampi were 0.52 (0.18) cm3 and 0.56 (0.18) cm3, respectively. Mean (SD) values of cortical folding index and sulcal depth were 1.29 (0.20) and 1.62 (0.63) mm, respectively. Mean (SD) fetal brain choline and creatine levels were 2.39 (0.34) IU and 2.94 (0.68) IU, respectively.

Infant Neurodevelopmental Results and Parenting Stress Scales

The mean (SD) scores for the BSID-III were 108 (16) for cognitive, 102 (13) for language, 105 (10) for motor, 103 (15) for adaptive, and 113 (21) for social-emotional domains. Of the 97 infants, delayed development (score <85) was seen in 3 infants (3%) for cognitive, 6 infants (6%) for language, 1 infant (1%) for motor, 8 infants (8%) for adaptive, and 6 infants (6%) for social-emotional domains. The mean (SD) scores for ITSEA were 48 (8) for externalizing, 46 (10) for internalizing, 41 (11) for dysregulation, and 51 (10) for competence domains. Of the 97 infants, 4 (4%) had externalizing problems, 3 (3%) had internalizing problems, and 2 (2%) had dysregulation problems (measured score ≥65); 3 infants (3%) had delays in the competence domain (measured score ≤35). The mean (SD) scores for PSI-SF were 12 (4) for defensive responding, 21 (7) for parental distress, 16 (5) for parent-child dysfunctional interaction, 20 (6) for difficult child, and 56 (16) for total stress domains.

Associations Between Prenatal Maternal Psychological Distress and Infant Neurodevelopmental Outcomes

Prenatal maternal stress was negatively associated with infant cognitive performance (β = −0.51; 95% CI, −0.92 to −0.09; P = .01) (Table 2). We further assessed whether infant neurodevelopment outcomes would differ in participants who tested positive on 1 vs multiple prenatal distress measures (SSAI, STAI, PSS, and/or EPDS). There was no significant difference in neurodevelopment outcomes among infants born to women who were positive on 1 vs multiple distress measures (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Therefore, we combined the participants with any (≥1) positive distress measure and referred to them as positive for maternal psychological distress.

Table 2. Regression Estimates for the Association of Prenatal Maternal Psychological Distress on Infant Neurodevelopment Outcome and Parenting Stress Index at 18-Month Testinga.

| Test domain | SSAI | STAI | PSS | EPDS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | P value | q | β (95% CI) | P value | q | β (95% CI) | P value | q | β (95% CI) | P value | q | |

| Infant neurodevelopment outcomeb | ||||||||||||

| BSID-III | ||||||||||||

| Cognitive | −0.08 (0.22 to 0.07) | .30 | .48 | −0.27 (−0.56 to 0.01) | .06 | .16 | −0.51 (−0.92 to −0.09) | .01 | .03 | −0.26 (−0.56 to 0.05) | .10 | .23 |

| Language | 0.004 (−0.11 to 0.11) | .94 | .94 | −0.04 (−0.25 to 0.17) | .70 | .72 | −0.05 (−0.33 to 0.22) | .69 | .72 | 0.15 (−0.14 to 0.43) | .30 | .48 |

| Motor | −0.03 (−0.13 to 0.07) | .59 | .68 | −0.14 (−0.31 to 0.02) | .09 | .21 | −0.20 (−0.43 to 0.04) | .09 | .21 | −0.17 (−0.4 to 0.06) | .15 | .31 |

| Social-emotional | 0.10 (−0.06 to 0.26) | .20 | .37 | 0.07 (−0.18 to 0.33) | .56 | .67 | 0.04 (−0.33 to 0.41) | .82 | .83 | −0.15 (−0.62 to 0.31) | .51 | .64 |

| Adaptive | 0.08 (−0.08 to 0.23) | .33 | .50 | 0.07 (−0.18 to 0.32) | .60 | .68 | −0.06 (−0.37 to 0.25) | .70 | .72 | 0.12 (−0.31 to 0.55) | .57 | .67 |

| ITSEA | ||||||||||||

| Externalizing | 0.01 (−0.03 to 0.06) | .48 | .64 | 0.04 (−0.05 to 0.13) | .35 | .50 | 0.04 (−0.06 to 0.15) | .43 | .60 | 0.05 (−0.05 to 0.14) | .34 | .50 |

| Internalizing | 0.07 (−0.03 to 0.18) | .17 | .34 | 0.08 (−0.07 to 0.22) | .29 | .48 | 0.16 (−0.05 to 0.37) | .13 | .29 | 0.14 (−0.16 to 0.45) | .35 | .50 |

| Dysregulation | 0.04 (−0.14 to 0.22) | .68 | .72 | 0.13 (−0.09 to 0.36) | .24 | .42 | 0.21 (−0.07 to 0.49) | .14 | .30 | 0.15 (−0.29 to 0.59) | .50 | .64 |

| Competence | −0.03 (−0.12 to 0.06) | .45 | .61 | −0.05 (−0.2 to 0.11) | .53 | .65 | −0.05 (−0.24 to 0.15) | .63 | .70 | −0.14 (−0.39 to 0.1) | .24 | .42 |

| Parenting stress index at 18 moc | ||||||||||||

| PSI-SF | ||||||||||||

| Defensive responding | 0.07 (0.02 to 0.11) | .004 | .01 | 0.15 (0.08 to 0.23) | <.001 | <.001 | 0.20 (0.1 to 0.31) | <.001 | <.001 | 0.13 (0.05 to 0.21) | .001 | .005 |

| Parental distress | 0.12 (0.04 to 0.2) | .002 | .008 | 0.26 (0.15 to 0.38) | <.001 | <.001 | 0.35 (0.18 to 0.52) | <.001 | <.001 | 0.28 (0.14 to 0.42) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Parent-child dysfunction interaction | 0.05 (0.0006 to 0.09) | .04 | .11 | 0.10 (0.03 to 0.17) | .002 | .008 | 0.13 (0.05 to 0.22) | .002 | .008 | 0.22 (0.1 to 0.34) | <.001 | .001 |

| Difficult child | 0.05 (−0.03 to 0.12) | .20 | .37 | 0.13 (0.02 to 0.24) | .02 | .05 | 0.16 (0.02 to 0.31) | .02 | .05 | 0.18 (0.04 to 0.32) | .01 | .03 |

| Total stress | 0.22 (0.05 to 0.39) | .009 | .03 | 0.49 (0.24 to 0.74) | <.001 | <.001 | 0.65 (0.29 to 1.01) | <.001 | .002 | 0.70 (0.35 to 1.05) | <.001 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: BSID-III, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, third edition; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; ITSEA, Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment; PSI-SF, Parenting Stress Index-Short Form; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; SSAI, Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory; STAI, Spielberger Trait Anxiety Inventory.

β is unstandardized coefficient that denotes the association for a 1-unit increase in prenatal maternal psychological distress scale and infant neurodevelopment outcome or parenting stress scale with 95% CIs around the estimate. q denotes adjusted P value using the false discovery rate; 56 tests were performed in this analysis.

Results based on generalized estimating equation models after controlling for gestational age at fetal visit, maternal education, maternal employment, total stress scale from PSI-SF at 18-month testing, and neurodevelopmental assessment during COVID-19 pandemic (yes or no).

Results based on generalized estimating equation models after controlling for gestational age at fetal visit, maternal education, maternal employment, and neurodevelopmental assessment during COVID-19 pandemic (yes or no).

Associations Between Prenatal Maternal Psychological Distress and Parenting Stress at 18-Month Testing

Prenatal maternal trait anxiety, stress, and depression were positively associated with all PSI-SF scales at 18-month testing (Table 2). Significant associations between prenatal distress and PSI-SF outcomes were noted in defensive responding (STAI: β = 0.15; 95% CI, 0.08 to 0.23; PSS: β = 0.20; 95% CI, 0.1 to 0.31; EPDS: β = 0.13; 95% CI, 0.05 to 0.21), parental distress (STAI: β = 0.26; 95% CI, 0.15 to 0.38; PSS: β = 0.35; 95% CI, 0.18 to 0.52; EPDS: β = 0.28; 95% CI, 0.14 to 0.42), parental-child dysfunction interaction (EPDS: β = 0.22; 95% CI, 0.1 to 0.34), and total stress (STAI: β = 0.49; 95% CI, 0.24 to 0.74; PSS: β = 0.65; 95% CI, 0.29 to 1.01; EPDS: β = 0.70; 95% CI, 0.35 to 1.05) (P < .001 for all).

Associations Between Fetal Brain Measures and Infant Neurodevelopmental Outcomes

Fetal cortical local gyrification index and sulcal depth were negatively associated with infant social-emotional performance (local gyrification index: β = −54.62; 95% CI, −85.05 to −24.19; P < .001; sulcal depth: β = −14.22; 95% CI, −23.59 to −4.85; P = .002) and competence scores (local gyrification index: β = −24.01; 95% CI, −40.34 to −7.69; P = .003; sulcal depth: β = −7.53, 95% CI, −11.73 to −3.32; P < .001) (Table 3). For fetal brain metabolic measures, choline and creatine levels were positively associated with infant adaptive behaviors (choline: β = 2.60; 95% CI, 0.40 to 4.79; P = .02; creatine: β = 1.58; 95% CI, 0.08 to 3.08; P = .03) (Table 3), but these associations were no longer significant after adjusting for multiple testing. Because prenatal maternal stress was negatively associated with infant cognitive performance (Table 2), we performed causal mediation analysis to measure whether this association was mediated by any fetal brain measure. We found that fetal left hippocampal volume accounted for 11% of the total prenatal maternal stress and infant cognitive outcome association (β = −0.11; bootstrapped 95% CI, −0.35 to −0.0002) (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Table 3. Regression Estimates for the Association of Fetal Brain Measures on Infant Neurodevelopmental Scoresa.

| Test domain | Volume | Cortical folding | Metabolites | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left hippocampus | Right hippocampus | Local gyrification index | Sulcal depth | Choline | Creatine | |||||||||||||

| β (95% CI) | P value | q | β (95% CI) | P value | q | β (95% CI) | P value | q | β (95% CI) | P value | q | β (95% CI) | P value | q | β (95% CI) | P value | q | |

| BSID-III | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cognitive | 26.69 (−12.64 to 66.02) | .18 | .66 | 4.15 (−26.57 to 34.87) | .79 | .95 | −2.02 (−23.74 to 19.70) | .85 | .95 | −0.11 (−6.38 to 6.16) | .97 | .97 | −0.24 (−2.22 to 1.74) | .81 | .95 | −0.42 (−1.57 to 0.74) | .47 | .84 |

| Language | −5.03 (−32.04 to 21.98) | .71 | .95 | −18.24 (−43.94 to 7.46) | .16 | .66 | −10.79 (−29.67 to 8.08) | .26 | .66 | −2.47 (−8.24 to 3.30) | .40 | .77 | 0.11 (−1.66 to 1.87) | .90 | .97 | −1.28 (−2.67 to 0.10) | .06 | .46 |

| Motor | −4.05 (−29.15 to 21.04) | .75 | .95 | −13.39 (−37.76 to 10.97) | .28 | .66 | −2.22 (−21.14 to 16.71) | .81 | .95 | −1.45 (−7.05 to 4.15) | .61 | .95 | 0.88 (−1.21 to 2.98) | .40 | .77 | −0.57 (−1.83 to 0.69) | .37 | .76 |

| Social-emotional | −10.88 (−59.22 to 37.47) | .65 | .95 | 4.96 (−37.27 to 47.18) | .81 | .95 | −54.62 (−85.05 to −24.19) | .0004 | .01 | −14.22 (−23.59 to −4.85) | .002 | .03 | 2.09 (−1.95 to 6.13) | .31 | .66 | 1.90 (−0.21 to 4.01) | .07 | .47 |

| Adaptive | 19.18 (−12.96 to 51.33) | .24 | .66 | 3.77 (−25.18 to 32.71) | .79 | .95 | 2.75 (−24.23 to 29.72) | .84 | .95 | 0.33 (−7.60 to 8.25) | .93 | .97 | 2.60 (0.40 to 4.79) | .02 | .21 | 1.58 (0.08 to 3.08) | .03 | .27 |

| ITSEA | ||||||||||||||||||

| Externalizing | 0.29 (−13.99 to 14.56) | .96 | .97 | 6.69 (−6.40 to 19.78) | .31 | .66 | −9.11 (−23.26 to 5.05) | .20 | .66 | −3.09 (−7.18 to 1.0) | .13 | .63 | −0.07 (−0.83 to 0.69) | .85 | .95 | −0.27 (−0.78 to 0.23) | .29 | .66 |

| Internalizing | −11.44 (−29.68 to 6.80) | .21 | .66 | −1.29 (−17.20 to 14.62) | .87 | .95 | −8.19 (−23.91 to 7.54) | .30 | .66 | −1.30 (−5.25 to 2.65) | .52 | .90 | −0.22 (−0.92 to 0.49) | .54 | .91 | 0.08 (−0.40 to 0.56) | .74 | .95 |

| Dysregulation | −12.41 (−31.89 to 7.07) | .21 | .66 | −2.54 (−21.73 to 16.65) | .79 | .95 | −13.10 (−28.76 to 2.55) | .10 | .60 | −3.10 (−7.20 to 1.0) | .13 | .63 | 0.50 (−0.44 to 1.44) | .29 | .66 | 0.26 (−0.38 to 0.90) | .42 | .78 |

| Competence | −0.57 (−20.28 to 19.14) | .95 | .97 | −10.46 (−30.78 to 9.85) | .31 | .66 | −24.01 (−40.34 to −7.69) | .003 | .04 | −7.53 (−11.73 to −3.32) | .0004 | .01 | 0.23 (−0.79 to 1.24) | .66 | .95 | −0.14 (−0.77 to 0.49) | .65 | .95 |

Abbreviations: BSID-III, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, third edition; ITSEA, Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment.

Results are based on generalized estimating equation models controlling for gestational age at fetal visit, prenatal maternal psychological distress status (positive or negative), maternal education, maternal employment, total stress scale from Parenting Stress Index–Short Form at 18-month testing, and neurodevelopmental assessment during COVID-19 pandemic (yes or no). β is an unstandardized coefficient that denotes the association for a 1-unit increase in fetal brain measure and infant neurodevelopment outcome with 95% CIs around the estimate. q denotes adjusted P value using the false discovery rate; 54 tests were performed in this analysis.

Discussion

In this longitudinal, prospective, observational cohort study, we found that prenatal maternal stress was inversely associated with infant cognitive outcome, and this association was mediated by fetal left hippocampal volume. In addition, prenatal maternal stress, anxiety, and depression were positively associated with parenting stress scores at 18-month testing. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that altered human fetal cortical folding may be associated with infant neurodevelopment. Specifically, fetal cortical local gyrification index and sulcal depth were negatively associated with infant social-emotional and competence performance.

The exact incidence of mental health disturbances in pregnant women is not known but is likely underestimated. In this study, all pregnant participants were healthy and had low-risk pregnancies, most were well educated and employed, and most were living in areas (Washington, DC) with good access to health care. Despite these seemingly favorable conditions, 36% of participants exceeded the positivity threshold for stress, anxiety, and/or depression. This is in keeping with recent studies57,58,59 reporting prenatal depression and anxiety in up to 18.4% and 25.3%, respectively, of women in high-income countries and of middle-to-high socioeconomic status. Furthermore, we found that prenatal maternal stress, depression, and anxiety were correlated with all PSI-SF scores at 18-month testing. This finding suggests that prenatal maternal distress may not be transient but persistent across the postnatal period with subsequent influences on both the parent-child interaction and infant self-regulation.

In addition, we found that prenatal maternal stress, even if not reaching the severity of a mental disorder, was associated with decreased infant cognitive performance. This finding is in keeping with results of previous studies14,15,16,60,61 showing cognitive impairments in children following early exposure to maternal stress. In particular, our findings suggest that this association may be partially mediated by fetal left hippocampal volume. This is supported by our previous study that maternal stress decreased fetal left hippocampal volume,1 as well as other studies that the hippocampal subregions were related to certain cognitive functions.62,63 The standardized assessment of infant cognitive performance further supports this mediation finding. Our bilateral asymmetrical finding may be explained by different functions and growth rates of left and right hippocampus.1,38,64 Our findings suggest that although the prevalence of prenatal maternal distress in our cohort may not be as high as in the high-risk population,3,65 its association with infant outcomes cannot be ignored.

Importantly, we found that increased fetal cortical gyrification index and sulcal depth were associated with decreased infant social-emotional and competence performance. Increased cortical gyrification has been suggested in children with dyslexia and autism,66,67 and sulcal depth has been associated with the severity of impaired performance on working memory and executive function in adults with schizophrenia.68 Our earlier study suggested that prenatal maternal psychological distress increased fetal cortical gyrification index and sulcal depth.1 The current study extends our previous findings and suggests a critical role for disturbances in emerging fetal cerebral cortical folding development in mediating the association between prenatal maternal distress and neurodevelopmental problems that later manifest in infancy.

In addition, we found positive associations between fetal brain choline and creatine levels and infant adaptive behaviors, although these associations were not significant after adjusting for multiple testing. Animal studies69 have suggested that there are associations between choline status and attention and memory, and choline supplementation during pregnancy improves cognitive and neurological function in offspring. In human studies,70 maternal plasma choline level in the second trimester was positively associated with cognitive development in 18-month-old infants. Levels of brain creatine have been linked to cognitive and emotional processing in infancy, and alterations in the brain creatine pathway have been related to psychiatric disorders.71 In addition, brain metabolites in healthy neonates have been associated with learning and memory in infants at 4 months.72 Our current study suggests that increased in utero fetal brain choline and creatine levels, in the setting of decreased prenatal maternal depression and stress reported in our previous study,1 are likely associated with better infant adaptive performance, which needs to be confirmed in a larger cohort.

These findings are particularly insightful, given the nature of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic; reports of increased maternal anxiety, stress, and depression73,74; and the underexplored nexus between elevated maternal distress during the pandemic and the health of the next generation of infants. More than 1 million US infants have been born in the COVID-19 pandemic era, yet we lack knowledge about the influence of pandemic-related maternal distress on infants’ long-term neurodevelopment. Our ongoing studies will continue to explore the association between heightened maternal distress amid the pandemic and children’s lifelong health.

Limitations

This study has potential limitations. First, maternal distress assessment at certain time points may not fully reflect maternal mental health status for the entire pregnancy. Second, the percentage of women positive for stress, anxiety, and depression will change using different cutoff scores. We chose cutoffs used for pregnant women in both our earlier work1,3 and those of others,26,27,29,30,33,34 but we acknowledge the potential for either false positives or false negatives. Third, in this study, cognitive, language, and motor skills on the Bayley Scales were evaluated by a licensed psychologist. However, infant social-emotional assessments and prenatal maternal psychological distress measures were based on maternal report. Although these maternal questionnaires are widely used in the literature and standardized with established psychometric properties, we acknowledge the possible bias that may exist in parent-reported measures. Fourth, data from 13% of T2-weighted scans and 17% of 1H-MRS images were not usable because of fetal motion; however, our percentage of lost data is similar to that in other fetal studies.75,76 Fifth, participants in our catchment area may not be reflective of other regions. The metropolitan Washington, DC, area is home to a highly educated, low-unemployment workforce, which may have increased access to health care needs not reflective of other geographical areas.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we report that prenatal maternal stress is associated with infant cognitive outcome, and this association is partially mediated by fetal left hippocampal volume. In addition, we report that increased fetal cortical gyrification index and sulcal depth in pregnancies complicated by maternal psychological distress is associated with decreased infant social-emotional and competence performance. Identifying early brain developmental biomarkers may help improve the identification of infants at risk for later neurodevelopmental impairment who might benefit from early targeted interventions.

eFigure 1. An Example of Fetal Brain Reconstruction From 2D Single Shot Fast Spin Echo MRI Slices of Coronal, Sagittal, and Axial Planes (Left) to a Single 3D Volume (Right)

eFigure 2. Prenatal Maternal State Anxiety (SSAI), Trait Anxiety (STAI), Stress (PSS), and Depression (EPDS) Scores Across Gestational Age (Weeks)

eTable 1. Infant Neurodevelopmental Outcomes With One and More Positive Maternal Distress Measures (SSAI, STAI, PSS, and/or EPDS)

eTable 2. Causal Mediation Analysis of the Relationship Between Prenatal Maternal Stress and 18-Month Cognitive Outcome With Fetal Brain Measure as the Mediator

References

- 1.Wu Y, Lu Y-C, Jacobs M, et al. Association of prenatal maternal psychological distress with fetal brain growth, metabolism, and cortical maturation. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1919940. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buss C, Davis EP, Muftuler LT, Head K, Sandman CA. High pregnancy anxiety during mid-gestation is associated with decreased gray matter density in 6-9-year-old children. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(1):141-153. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu Y, Kapse K, Jacobs M, et al. Association of maternal psychological distress with in utero brain development in fetuses with congenital heart disease. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(3):e195316. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiu A, Anh TT, Li Y, et al. Prenatal maternal depression alters amygdala functional connectivity in 6-month-old infants. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5(2):e508. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKee KA. The Effects of Prenatal Maternal Stress and Early Life Maternal Stress on Adolescent Hippocampal Morphology: Project Ice Storm. McGill University; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandman CA, Buss C, Head K, Davis EP. Fetal exposure to maternal depressive symptoms is associated with cortical thickness in late childhood. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77(4):324-334. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lebel C, Walton M, Letourneau N, Giesbrecht GF, Kaplan BJ, Dewey D. Prepartum and postpartum maternal depressive symptoms are related to children’s brain structure in preschool. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(11):859-868. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buss C, Davis EP, Shahbaba B, Pruessner JC, Head K, Sandman CA. Maternal cortisol over the course of pregnancy and subsequent child amygdala and hippocampus volumes and affective problems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(20):E1312-E1319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201295109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wen DJ, Poh JS, Ni SN, et al. Influences of prenatal and postnatal maternal depression on amygdala volume and microstructure in young children. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7(4):e1103. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qiu A, Rifkin-Graboi A, Chen H, et al. Maternal anxiety and infants’ hippocampal development: timing matters. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3(9):e306. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rifkin-Graboi A, Bai J, Chen H, et al. Prenatal maternal depression associates with microstructure of right amygdala in neonates at birth. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(11):837-844. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarkar S, Craig MC, Dell’Acqua F, et al. Prenatal stress and limbic-prefrontal white matter microstructure in children aged 6-9 years: a preliminary diffusion tensor imaging study. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2014;15(4):346-352. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2014.903336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheinost D, Kwon SH, Lacadie C, et al. Prenatal stress alters amygdala functional connectivity in preterm neonates. Neuroimage Clin. 2016;12:381-388. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van den Bergh BR, Mulder EJH, Mennes M, Glover V. Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioural development of the fetus and child: links and possible mechanisms—a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29(2):237-258. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cruceanu C, Matosin N, Binder EB. Interactions of early-life stress with the genome and epigenome: from prenatal stress to psychiatric disorders. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2017;14:167-171. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laplante DP, Barr RG, Brunet A, et al. Stress during pregnancy affects general intellectual and language functioning in human toddlers. Pediatr Res. 2004;56(3):400-410. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000136281.34035.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buss C, Davis EP, Hobel CJ, Sandman CA. Maternal pregnancy-specific anxiety is associated with child executive function at 6-9 years age. Stress. 2011;14(6):665-676. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2011.623250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den Bergh BRH, Dahnke R, Mennes M. Prenatal stress and the developing brain: risks for neurodevelopmental disorders. Dev Psychopathol. 2018;30(3):743-762. doi: 10.1017/S0954579418000342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Essen DC, Barch DM. The human connectome in health and psychopathology. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):154-157. doi: 10.1002/wps.20228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones SL, Dufoix R, Laplante DP, et al. Larger amygdala volume mediates the association between prenatal maternal stress and higher levels of externalizing behaviors: sex specific effects in Project Ice Storm. Front Hum Neurosci. 2019;13:144. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2019.00144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis EP, Hankin BL, Glynn LM, Head K, Kim DJ, Sandman CA. Prenatal maternal stress, child cortical thickness, and adolescent depressive symptoms. Child Dev. 2020;91(2):e432-e420. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomason ME, Hect J, Waller R, et al. Prenatal neural origins of infant motor development: associations between fetal brain and infant motor development. Dev Psychopathol. 2018;30(3):763-772. doi: 10.1017/S095457941800072X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van den Heuvel MI, Hect JL, Smarr BL, et al. Maternal stress during pregnancy alters fetal cortico-cerebellar connectivity in utero and increases child sleep problems after birth. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):2228. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81681-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Middleton H, Shaw I. Distinguishing mental illness in primary care: we need to separate proper syndromes from generalised distress. BMJ. 2000;320(7247):1420-1421. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7247.1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385-396. doi: 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andreou E, Alexopoulos EC, Lionis C, et al. Perceived Stress Scale: reliability and validity study in Greece. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(8):3287-3298. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8083287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gholipoor P, Saboory E, Ghazavi A, et al. Prenatal stress potentiates febrile seizure and leads to long-lasting increase in cortisol blood levels in children under 2 years old. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;72:22-27. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spielberger CD, Sydeman SJ. State-trait anxiety inventory and state-trait anger expression inventory. In: Maruish ME, ed. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcome Assessment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1994:292-321. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woolhouse H, Mercuri K, Judd F, Brown SJ. Antenatal mindfulness intervention to reduce depression, anxiety and stress: a pilot randomised controlled trial of the MindBabyBody program in an Australian tertiary maternity hospital. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):369. doi: 10.1186/s12884-014-0369-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tendais I, Costa R, Conde A, Figueiredo B. Screening for depression and anxiety disorders from pregnancy to postpartum with the EPDS and STAI. Span J Psychol. 2014;17:E7. doi: 10.1017/sjp.2014.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782-786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, Oke S, Golding J. Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. BMJ. 2001;323(7307):257-260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7307.257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinto TM, Caldas F, Nogueira-Silva C, Figueiredo B. Maternal depression and anxiety and fetal-neonatal growth. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2017;93(5):452-459. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2016.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Areias ME, Kumar R, Barros H, Figueiredo E. Comparative incidence of depression in women and men, during pregnancy and after childbirth: validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in Portuguese mothers. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169(1):30-35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.1.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kainz B, Steinberger M, Wein W, et al. Fast volume reconstruction from motion corrupted stacks of 2D slices. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2015;34(9):1901-1913. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2015.2415453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serag A, Aljabar P, Ball G, et al. Construction of a consistent high-definition spatio-temporal atlas of the developing brain using adaptive kernel regression. Neuroimage. 2012;59(3):2255-2265. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rueckert D, Sonoda LI, Denton ERE, et al. Comparison and evaluation of rigid and nonrigid registration of breast MR images. SPIE conference proceedings. May 21, 1999. Accessed March 29, 2022. https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/conference-proceedings-of-spie/3661/1/Comparison-and-evaluation-of-rigid-and-nonrigid-registration-of-breast/10.1117/12.348637.short

- 38.Ge X, Shi Y, Li J, et al. Development of the human fetal hippocampal formation during early second trimester. Neuroimage. 2015;119:33-43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.06.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacob FD, Habas PA, Kim K, et al. Fetal hippocampal development: analysis by magnetic resonance imaging volumetry. Pediatr Res. 2011;69(5 pt 1):425-429. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318211dd7f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li G, Wang L, Shi F, et al. Mapping longitudinal development of local cortical gyrification in infants from birth to 2 years of age. J Neurosci. 2014;34(12):4228-4238. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3976-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yun HJ, Im K, Yang J-J, Yoon U, Lee J-M. Automated sulcal depth measurement on cortical surface reflecting geometrical properties of sulci. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development: Bayley-III. Harcourt; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ. ITSEA: Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment Examiner’s Manual. PsychCorp; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anderson PJ, De Luca CR, Hutchinson E, Roberts G, Doyle LW; Victorian Infant Collaborative Group . Underestimation of developmental delay by the new Bayley-III Scale. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(4):352-356. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS, Irwin JR, Wachtel K, Cicchetti DV. The Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment: screening for social-emotional problems and delays in competence. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29(2):143-155. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thurm A, Farmer CA, Manwaring S, Swineford L. 1.10 Social-emotional and behavioral problems in toddlers with language delay. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(10):S155. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.09.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abidin RR, Abidin RR. Parenting Stress Index (PSI). Pediatric Psychology Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haskett ME, Ahern LS, Ward CS, Allaire JC. Factor structure and validity of the parenting stress index-short form. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2006;35(2):302-312. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pérez-Padilla J, Menéndez S, Lozano O. Validity of the Parenting Stress Index Short Form in a sample of at-risk mothers. Eval Rev. 2015;39(4):428-446. doi: 10.1177/0193841X15600859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barroso NE, Hungerford GM, Garcia D, Graziano PA, Bagner DM. Psychometric properties of the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF) in a high-risk sample of mothers and their infants. Psychol Assess. 2016;28(10):1331-1335. doi: 10.1037/pas0000257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reitman D, Currier RO, Stickle TR. A critical evaluation of the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF) in a head start population. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2002;31(3):384-392. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aracena M, Gómez E, Undurraga C, Leiva L, Marinkovic K, Molina Y. Validity and reliability of the Parenting Stress Index Short Form (PSI-SF) applied to a Chilean sample. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25(12):3554-3564. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0520-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee SJ, Gopalan G, Harrington D. Validation of the Parenting Stress Index–Short Form with minority caregivers. Res Soc Work Pract. 2016;26(4):429-440. doi: 10.1177/1049731514554854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu Y-C, Kapse K, Andersen N, et al. Association between socioeconomic status and in utero fetal brain development. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e213526. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.3526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B. 1995;57(1):289-300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jung SJ. Introduction to mediation analysis and examples of its application to real-world data. J Prev Med Public Health. 2021;54(3):166-172. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.21.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5 pt 1):1071-1083. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, Koren G, Einarson TR. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):698-709. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000116689.75396.5f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Austin M-P, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Leader L, Saint K, Parker G. Maternal trait anxiety, depression and life event stress in pregnancy: relationships with infant temperament. Early Hum Dev. 2005;81(2):183-190. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2004.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buitelaar JK, Huizink AC, Mulder EJ, de Medina PGR, Visser GHA. Prenatal stress and cognitive development and temperament in infants. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(1)(suppl):S53-S60. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00050-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.King S, Laplante DP. The effects of prenatal maternal stress on children’s cognitive development: Project Ice Storm. Stress. 2005;8(1):35-45. doi: 10.1080/10253890500108391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Evans TE, Adams HHH, Licher S, et al. Subregional volumes of the hippocampus in relation to cognitive function and risk of dementia. Neuroimage. 2018;178:129-135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eichenbaum H. Hippocampus: cognitive processes and neural representations that underlie declarative memory. Neuron. 2004;44(1):109-120. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de Toledo-Morrell L, Dickerson B, Sullivan MP, Spanovic C, Wilson R, Bennett DA. Hemispheric differences in hippocampal volume predict verbal and spatial memory performance in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Hippocampus. 2000;10(2):136-142. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Williams NA, Villachan-Lyra P, Marvin C, et al. Anxiety and depression among caregivers of young children with Congenital Zika Syndrome in Brazil. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(15):2100-2109. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1692252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Williams VJ, Juranek J, Cirino P, Fletcher JM. Cortical thickness and local gyrification in children with developmental dyslexia. Cereb Cortex. 2018;28(3):963-973. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sasaki M. Single-photon emission computed tomography and electroencephalography findings in children with autism spectrum disorders. In: Patel VB, Preedy VR, Martin CR, eds. Comprehensive Guide to Autism. Springer; 2014:929-945. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Csernansky JG, Gillespie SK, Dierker DL, et al. Symmetric abnormalities in sulcal patterning in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2008;43(3):440-446. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McCann JC, Hudes M, Ames BN. An overview of evidence for a causal relationship between dietary availability of choline during development and cognitive function in offspring. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30(5):696-712. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu BTF, Dyer RA, King DJ, Richardson KJ, Innis SM. Early second trimester maternal plasma choline and betaine are related to measures of early cognitive development in term infants. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Allen PJ. Creatine metabolism and psychiatric disorders: does creatine supplementation have therapeutic value? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36(5):1442-1462. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Merz EC, Monk C, Bansal R, et al. Neonatal brain metabolite concentrations: associations with age, sex, and developmental outcomes. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0243255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lebel C, MacKinnon A, Bagshawe M, Tomfohr-Madsen L, Giesbrecht G. Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:5-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Preis H, Mahaffey B, Heiselman C, Lobel M. Pandemic-related pregnancy stress and anxiety among women pregnant during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2(3):100155. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Evangelou IE, du Plessis AJ, Vezina G, Noeske R, Limperopoulos C. Elucidating metabolic maturation in the healthy fetal brain using 1H-MR spectroscopy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37(2):360-366. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Scott JA, Habas PA, Kim K, et al. Growth trajectories of the human fetal brain tissues estimated from 3D reconstructed in utero MRI. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2011;29(5):529-536. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2011.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. An Example of Fetal Brain Reconstruction From 2D Single Shot Fast Spin Echo MRI Slices of Coronal, Sagittal, and Axial Planes (Left) to a Single 3D Volume (Right)

eFigure 2. Prenatal Maternal State Anxiety (SSAI), Trait Anxiety (STAI), Stress (PSS), and Depression (EPDS) Scores Across Gestational Age (Weeks)

eTable 1. Infant Neurodevelopmental Outcomes With One and More Positive Maternal Distress Measures (SSAI, STAI, PSS, and/or EPDS)

eTable 2. Causal Mediation Analysis of the Relationship Between Prenatal Maternal Stress and 18-Month Cognitive Outcome With Fetal Brain Measure as the Mediator