Abstract

SARS-CoV-2, the causal agent of COVID-19, is primarily a pulmonary virus that can directly or indirectly infect several organs. Despite many studies carried out during the current COVID-19 pandemic, some pathological features of SARS-CoV-2 have remained unclear. It has been recently attempted to address the current knowledge gaps on the viral pathogenicity and pathological mechanisms via cellular-level tropism of SARS-CoV-2 using human proteomics, visualization of virus-host protein-protein interactions (PPIs), and enrichment analysis of experimental results. The synergistic use of models and methods that rely on graph theory has enabled the visualization and analysis of the molecular context of virus/host PPIs. We review current knowledge on the SARS-COV-2/host interactome cascade involved in the viral pathogenicity through the graph theory concept and highlight the hub proteins in the intra-viral network that create a subnet with a small number of host central proteins, leading to cell disintegration and infectivity. Then we discuss the putative principle of the “gene-for-gene and “network for network” concepts as platforms for future directions toward designing efficient anti-viral therapies.

Keywords: Gene network, SARS-CoV-2, Virus-host interactome, Protein-protein interactions

1. Introduction

The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) the causal agent of a zoonotic disease called COVID-19 infected more than 422 M people including 5.8 M deaths as of February 2022 [1,2]. Despite the widespread vaccination against the disease, the global number of new cases increased sharply due to the attenuation of the vaccine-induced immunity over time and the emergence of new variants [1,[3], [4], [5]]. Although the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) have infected many people in 2012 and 2003, respectively, the SARS-CoV-2 is the deadliest coronavirus to have ever emerged in the human population [6,7]. Increasing virulence of the coronaviruses in the last two decades is a wake-up call for global health to not only gain in-depth information on virulence factors of its pathogenicity but also provide therapeutic intervention for this severe respiratory illness to end up this dramatic story [8,9].

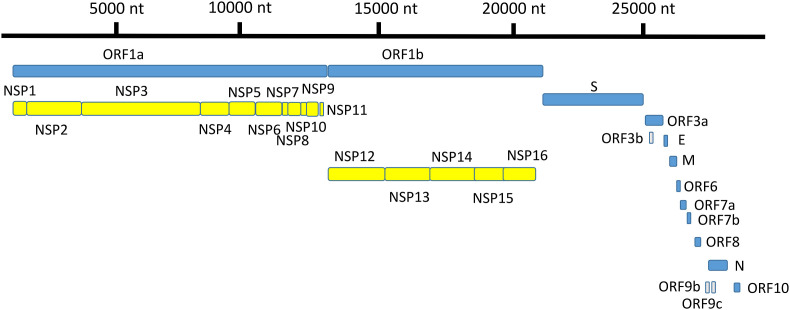

SARS-CoV-2 genome includes a 30-kb translation-ready RNA molecule that encodes 14 open-reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. 1 ). ORF1a and ORF1ab encode polyproteins, which are auto-proteolytically cleaved to form 16 non-structural proteins (NSP1–NSP16). NSPs play a variety of enzymatic roles by forming a replica–transcriptase complex and act as transcription factors that synthesize 13 ORFs for transcription of overlapping 4 structural proteins (spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M) and nucleocapsid (N)), and nine accessory factors (orf3a, orf3b, orf6, orf7a, orf7b, orf8, orf9b, orf9c, and orf10). Coronaviruses contain different numbers of accessory protein genes that are genus-specific and share no homology with other known viral proteins [10,11].

Fig. 1.

SARS-CoV-2 genome annotation showing position and relative size of ORFs of 4 structural proteins, 16 non-structural proteins and 9 accessory factors. Fig. 1 was illustrated using Adobe Photoshop 2021 v 22.2. nt = nucleotide.

The process of the SARS-CoV-2 endocytosis starts with the recognition of the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) by the spike protein. Then the S1/S2 boundary breaks down into the S1 and S2 subunits by the two host proteases TMPRSS-2 and cathepsins B/L. It is noteworthy that endocytosis of the virions does not always carry out using the receptor, ingress from cell to cell is facilitated by a furin-like binding site near the S1/S2 boundary. Upon the entrance of the virus genome into the host cell cytoplasm, the replicase gene activates and hijacks the host molecular machine to synthesize the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) genome and assembly into new virions which are facilitated by the association of M protein with structural proteins E and N [12]. The NSP7 and NSP8 enhanced the function of NSP12 for RNA-dependent RNA polymerization (RdRp), and NSP10 interacted with both NSP14, and NSP16 for cap formation and RNA 3′-end mismatch excision, respectively [13]. Interspersed between structural proteins are accessory proteins (ORFs), which their structure and functions are undefined yet. However, previous studies on other coronaviruses have suggested that accessory factors modulated host proteins related to virus replication and growth [14,15]. For example, the interferon pathway was targeted by NSP13, NSP15, and ORF9b; and the NF-κB pathway was targeted by NSP13 and ORF9c. In another study, over-expression of viral proteins in human 293 T cells revealed that the orf6 had the highest cytotoxicity among the other viral proteins through interaction with host nucleopore proteins such as XPO1 [15].

2. Developing antiviral medicines against COVID-19

The critical need to control the SARS-CoV-2 disease has enforced the researchers to prioritize the use of the already-known FDA-approved drugs instead of discovering de novo antiviral drugs, which is called “drug repurposing/repositioning/retasking/reprofiling” [[16], [17], [18]]. Since de novo drug discovery takes about ten years from developing to marketing, utilizing the existing drugs that their pharmacokinetics and manufacturing information is available is much more economical in terms of time and cost [16,19]. Nowadays, drug repurposing accounts for about 25% of the pharmaceutical industry's annual revenue [20]. Two principles that help discover the new indications of an old drug are the similarity of the two drugs' signatures on the single metabolic pathway or the matching single drug signature with the clinical complications of the two diseases [[21], [22], [23]]. Several papers highlighted the tools and methodologies leading to clinical uses of already FDA-approved drugs in the different therapeutic areas [20,21,[24], [25], [26]]. In the conventional activity-based drug repositioning strategies, drug signature is extracted from the details of literature or databases related to the drug side effects profile, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and chemical structure to discover novel indications of drug compounds through structure-based and ligand-based approaches [21,27]. In the structure-based methods, the docking simulation techniques predict the drug-ligand interaction if we have a three-dimensional structure of the target and ligands [28]. For example, based on the genomic sequences and protein structure of SARS-CoV2 enzymes, catalytic sites of the four enzymes of SARS-CoV2 shared high similarities with SARS-CoV and MERS [29,30]. Therefore, existing anti-SARS-CoV and anti-MERS drugs that target these enzymes can be repositioned for SARS-CoV-2 [29]. In another example, the drug Arbidol (ARB), which prevents the fusion of influenza virus, and Galidzivir, which is used as an adenine analog against influenza, are considered anti-covid drugs [31]. In the ligand-based approaches, the prediction of the target-ligand interaction is based on the suitability of a target protein with the competent known ligands [32]. One of the biggest challenges that traditional methods are faced is that these methods use a limited amount of information; thus, the acquisition of data from large-scale databases is not practical. Besides, the traditional methods cannot successfully differentiate between direct/indirect drug-target associations from random drug-target associations with high accuracy. Therefore, the computational approaches must be applied for systematic drug repurposing [21].

3. Computational drug repurposing approaches

Drug repositioning is a complicated process that involves multiple steps and requires various kinds of data analysis followed by experimental validation. The explosion of the fast-growing information in the databases pushes the drug repurposing toward using the computational frameworks and bioinformatic tools for collecting and integrating numerous biological data systematically. The first step in the drug repurposing workflow is data mining by searching related databases or articles [21,33]. Many review articles have introduced and discussed biomedical databases which are used widely in computational repurposing, which include: drug-centric databases such as (BindingDB, CHEMBL, DrugBank, DrugMap, Offsides, PROMISCUOUS, PubChem, SIDER, STITCH, SuperTarget, etc.), disease-centric databases such as (Disease ontology, DISEASE, DiseaseConnect, OMIM, MalaCards, DisGeNET, etc.) and biomolecular data such as (BioGrid, Gene ontology, HPRD, PDB, STRING, UniProtKB, etc.) [21,25,26,33,34]. Tanoli et al. (2021) have comprehensively reviewed the public data supporting drug repurposing and divided 102 databases into four main categories with 17 subcategories: (i) chemical, (ii) biomolecular, (iii) drug-target interaction, and (iv) disease databases. The authors have introduced the required databases in the drug repurposing flowchart and recommended high-quality databases in different steps (Table 1 ) [25].

Table 1.

Recommended database for computational drug repurposing from recently published comprehensive review by Tanoli et al. (2021) [25].

| Recommended database | Category | Subcategory | Link | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DrugTargetCommons (DTC) | Drug target interaction databases | Bioactivity databases | http://drugtargetcommons.fimm.fi/ |

| 2 | ChEMBL | Drug target interaction databases | Bioactivity databases | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/ |

| 3 | PubChem | Chemical databases | Structure databases | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ |

| 4 | ClinicalTrials | Disease databases | Clinical databases | https://www.clinicaltrialsregister |

| 5 | Side Effect Resource (SIDER) | Disease databases | Drug side effects | http://sideeffects.embl.de/ |

| 6 | Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) | Biomolecular data | Molecular omics | https://portals.broadinstitute.org/ccle |

| 7 | CellMiner Cross Database (CellMinerCDB) | Biomolecular data | Molecular omics | https://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminercdb/ |

After the information retrieval (IR), the artificial intelligence (RI) with various in silico algorithms such as Naïve Bayesian, k-Nearest Neighbor (kNN), Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and deep neural networks (DNN) classify essential pieces of information from heterogeneous big-data into predefined categories [21,26]. In the next step, relationships information from different types of the biological molecules related to target, drugs, and diseases extract for identifying the novel therapeutic potentials for the existing drugs [35]. After discovering repurposable drugs, they are categorized according to the number of targets or their minimum side effects by unique formulas. High-ranking candidates are validated according to the gold-standard datasets followed by in vitro/vivo experiments before marketing [21].

4. Network-based drug repurposing

Network mapping is a type of post-genomic analysis in which visual information helps us examine the hidden aspect of underlying connections at the second and third levels for a better understanding of the dynamics of complex systems in biology or any other area of science. In biology, a network is constructed by repositories of interactions data and subjected to statistical analysis using computer-aided models based on the graph theory concept. In such a concept, nodes/vertex represent drugs, genes, proteins, molecules, phenotypes, or any other biological units, and edges represent functional similarities, physical interaction, mode of actions, mechanisms, or any other directional or non-directional relationships [21]. Then various networks can be mapped using different types of nodes and edges and classified into: gene regulatory networks, metabolic networks, protein-protein interaction (PPIs) networks, drug-target interaction networks, drug-drug interaction networks, drug-disease association networks, drug-side effect association networks, disease–disease interaction networks [21]. During network analysis, each node has multiple scores according to the information importance at that point which includes: degree value (the number of edges of a node), clustering coefficient (represents the density of edges connecting to a node), closeness centrality (how much a node is close to all other nodes), betweenness centrality (how many times a node is on the shortest path between two subnetworks) [36]. Then, any drug-target attributed data has been integrated into the network to introduce therapeutic biomarker candidates [37]. Some useful protein-protein interaction databases for network mapping were reviewed by Tanoli et al., 2020 which are (Human Protein Reference Database (HPRD), Biological General Repository for Interaction Datasets (BioGRID), Molecular INTeractiondatabase (MINT), GPS-Prot, Wiki-Pi, Protein Interaction Network Analysis (PINA), MPIDB for the retrieval of interacting genes (STRING), Mammalian protein-protein interaction (MIPS), IntAct, and Database of Interacting Proteins (DIP) [25]. In a systematic review regarding ranking the protein-protein interaction databases from a user's perspective, 16 databases were carefully selected from 375 PPI resources and compared with the gold-standard PPI-set [38]. Based on the coverage of ‘experimentally verified’ PPIs data, total information of STRING and UniHI covered only 84% of PPIs of which more than 70% belonged to STRING. Based on ‘total’ (experimentally verified and predicted) PPIs, concurrent application three websites (i.e. hPRINT, STRING, and IID) provided approximately 94% of the information. The authors concluded that the popularity of a database did not always correlate with its expected information coverage [38]. There are also some specific databases for virus-host interactomics such as (viruses.STRING, VirusMentha, VirHostNet) (viruses.STRING, VirusMentha, VirHostNet) [39].

The three basic tools for the creation of a network are (Cytoscape, INGENUITY, and PATHWAY STUDIO) of which Cytoscape software (https://cytoscape.org/) is the most popular open-source platform with multiple plug-ins implemented for screening top informative nodes in the high-level interaction data [40,41]. We can also benefit from web applications for the network-based analysis of the drug databases such as COVIDrugNet (http://compmedchem.unibo.it/covidrugnet) to discover potential repurposed drugs in clinical trials [34].

5. Virus-host interactions during infection

Viruses are intracellular parasites that hijack the molecular machinery of their hosts to accomplish their reproduction mission; thus, viral-host interactions play an essential role in the initiation of virulence in the host cells [42]. During infection, viral proteins interacted directly with some host proteins, which indirectly misregulated other host proteins.

PPIs usually involve a flat interaction interface between the domains/motifs of the host and viral proteins that is specific to the virus family. For example, Kruse et al., 2021 identified 269 peptide-based interactions for 18 coronaviruses, providing an attractive strategy for discovering specific antiviral reagents [[43], [44], [45]]. Protein-protein interactions are verified or predicted by experimental methods and computational simulation, respectively [[46], [47], [48]]. Most used experimental procedures are cloning followed by affinity-purification-mass spectrometry (AP-MS), comprehensive identification of RNA-binding proteins by mass spectrometry (ChIRP-MS), or yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assay [[49], [50], [51]]. These experimental techniques help identify the host key proteins that bind to viral proteins and design drugs for them [39,52]. For example, Gordon et al. (2020) attempted to predict human binding partners of 26 SARS-CoV-2 proteins using HEK293T cells as hosts for expressed viral proteins [52]. Using affinity-purification followed by mass-spectrometry, they reported 332 SARS-CoV-2-human (CoV-2-Hu) PPIs. Further chemoinformatics searches from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to pharmacology (2020-3-12) and the ChEMBL25 database revealed 66 human druggable proteins that were inhibited by ten different chemotypes, which included inhibitors of mRNA translation (e.g. zotatifin) and regulators of the sigma-1 and sigma-2 receptors (e.g. haloperidol) [52]. The peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) proteome signature in COVID-19 that has been explored by host-pathogen protein interactome analysis revealed more than 350 host proteins that are significantly perturbed in COVID-19-derived PBMCs and 286 human proteins with high degree and high centrality score that are targeted by SARS-CoV-2 [13]. This provided important insights about SARS-CoV-2 pathogenicity and potential novel targets for designing antiviral drugs or repurposing existing ones. Furthermore, in some other cases, the network-based protein signatures may not only identify the potential drug targets but also derive therapy clues for other specific diseases like respiratory, cardiovascular, and immune system diseases [53]. For instance, the antiviral drugs derived from herpes virus PPIs, major-type rhinovirus and minor-type rhinovirus have been confirmed by another study on Ebola [54].

The indirect effect of the virus on the host proteins is gene expression changes of the host proteins that are investigated by transcriptomic analyses. Elucidating the misregulated host genes in response to the virus potentially can reveal insights into viral pathogenesis and help characterize drug targets. Some of these genes were indispensable for a successful viral infection called host dependency genes (HDG) which suppression of their expression by Gene-trap, RNA interference (RNAi) approach, or genome editing tool (i.e. CRISPR-Cas) will rescue cells from infection [24,55]. Li et al. (2020) interrogated the host dependency genes to find drug targets via enrichment analysis and gene regulatory networks combined with drug-related databases [24]. sing two machine learning methods (DeepCPI and DTINet), they introduced the top 20 drug candidates for Coronaviridae viruses, of which the Baricitinib had the best score [24]. Further docking simulation analysis also approved the strong binding affinity of the Baricitinib with its predicted targets: Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT) signaling [24,56]. The main indication of Baricitinib is rheumatoid arthritis, and it is used in patients with COVID-19 as an immunomodulation treatment via lowering the cytokine effect.

Another interesting network-based analysis is integrating knowledge about SARS-CoV-2-Hu physical PPIs with host transcriptomic change in response to the SARS-CoV-2 to develop a Unified Knowledge Space (UKS) [57]. This kind of network has been constructed through computing the shortest paths between the physical interacting (PI) and the differentially expressed (DE) gene sets to discover intermediate proteins as potential therapeutic targets [57].

6. Host-based repurposed drugs

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, many drugs have been repurposed for the disease. Some of them work directly on viral proteins. According to a systematic review which was worked by Mohamed et al., 2021, most repurposed direct-acting drugs were against non-structural proteins of the SARS-CoV2: the main 3C-like protease (Lopinavir, Ritonavir, Indinavir, Atazanavir, Nelfinavir, and Clocortolone), RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Remdesivir and Ribavirin), and the papain-like protease (Mycophenolic acid, Telaprevir, Boceprevir, Grazoprevir, Darunavir, Chloroquine, and Formoterol). Some of the mentioned drugs were multi-targeted drugs such as Atazanavir which targeted up to six SARS-CoV2 proteins [58]. However, the repertoire of direct-acting drugs is decreasing due to the emergence of drug resistance following the rapid evolution of viral populations [[59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64]]. Therefore, discovering essential host-oriented molecules associated with viral pathogenicity is critical for developing novel antiviral drugs [65]. The most common host-target repurposed drugs are shown in Table 2 [7,66].

Table 2.

The most common host-target repurposed drugs for COVID-19.

| Drug | Mechanism of Action | main indication |

|---|---|---|

| Azithromycin | Inhibition translation of mRNA | Macrolide antibiotic |

| Carrimycin | Inhibition translation of mRNA | Macrolide antibiotic |

| Doxycycline | Inhibition bacterial protein synthesis | Tetracycline antibiotic |

| Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine | Increase of lysosomal pH in antigen-presenting cells | Malaria, systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Nitazoxanide | Inhibition of the pyruvate: ferredoxin/flavodoxin oxidoreductase cycle |

Broad-spectrum antiparasitic |

| Losartan Valsartan |

Competitive angiotensin II receptor type 1 antagonist | Hypertension |

| Tetrandrine | Calcium channel blocker | Hypertension |

| Spironolactone | Potassium-sparing diuretic | Hypertension |

| Bromhexine | Increasing lysosomal activity | Mucolytic |

| Dornase alfa | Recombinant human deoxyribonuclease I | Cystic fibrosis |

| Dexmedetomidine | Selective alpha-2 adrenoceptor agonist | Sedation |

| Fluoxetine | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | Antidepressant |

| Ruxolitinib | JAK inhibition | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Tocilizumab | Interleukin-6 receptor antagonist | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Eculizumab | Monoclonal antibody against C5 | |

| Dexamethasone | Inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine production Inflammation |

, immune system disorders |

| Camostat | Inhibition of the transmembrane protease, serine 2 enzyme |

Chronic pancreatitis |

| Interferons (IFN) | Initiation of JAK-STAT signaling cascades | HBV, HCV, various autoimmune disorders, and cancers |

The “gene for gene” hypothesis has been proposed for the description of the viral-host protein interaction under the viral disease process [67]. This hypothesis describes how a viral protein bind to its target in the host for viral diseases. But “gene for gene” just focused on a single protein of the virus and a host protein. In this review, we show that the “gene for gene” theory should be replaced by the network for network concept, especially in SARS-CoV-2/host protein interactions and the network-network concept provides potential platforms for discovering efficient drug targets from viruses and human proteins. As the initial part of this review, we attempted to highlight the SARS-CoV-2 proteome data relevant to intra-viral PPIs that were validated by the experimental studies (Table 3 ). In the next step, we highlighted and discussed the hub proteins in intra-viral PPIs, then we profound current knowledge on the SARS-COV-2/host interactome cascade involved in the viral pathogenicity through graph theory concept and highlighted the hub proteins in the intra-viral network that create a subnet with a small number of host-centered proteins, leading to cell disintegration and infectivity. We hope that this paper may stimulate the identification of novel methodological approaches based on the network for the network concept.

Table 3.

Intra-viral interactions of SARS-CoV-2 proteins. All of the SARS-CoV-2 protein sequence identity and similarity percent are in comparison with SARS-CoV [68].

| SARS-CoV-2 protein | Approximate length (a.a.) | Seq. Identity (%) | Seq. Similarity (%) | Predicted function | Interaction(s) with other proteins | Self association | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-structural proteins | |||||||

| NSP 1 | 180 | 84.4 | 91.1 | A host shut-off factor blocks the ribosomal mRNA entry channel to inhibit host translation and antagonizes interferon induction | orf7b | - | [13] [69] [70] |

| NSP2 | 638 | 68.3 | 82.9 | Manipulate the host factors involved in calcium homeostasis at ER-mitochondrial sites. Controls the host milieu and cellular processes including mitochondria biogenesis. |

NSP15 NSP5 M orf10 orf7b |

+ | [52] [13] [71] [72] |

| NSP3 | 1945 | 76 | 91.8 | A papain-like protease (PLP) cleaves the viral polyprotein to produce NSP1-3. A multi-pass membrane protein that forms a complex with Nsp4 and Nsp6 necessary for viral replication. |

NSP4 NSP6 NSP2 |

- | [52] [73] [74] |

| NSP4 | 500 | 80 | 90.8 | A multi-span membrane protein that participates in organizing and localization of viral replication complex into double-membrane vesicles in the cytoplasm. | N orf3a orf7b NSP3 NSP6 |

- | [52] [13] [74] |

| NSP5 | 306 | 96.1 | 98.7 | A 3-chymotrypsin is like a protease (3CLpro) responsible for auto-proteolytic cleavage of ORF1a and ORF1b after the host ribosome translation. Also called the main protease (Mpro) because it releases and matures 13 NSPs (NSP4-NSP16). Predicted to cleave the human proteins and hijack innate immunity. Has a critical role in SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. |

NSP2 NSP13 M orf10 | + | [52] [13] [75] [76] [77] |

| NSP6 | 290 | 87.2 | 94.8 | A multi-pass membrane protein that ensures viral replication by inducing double-membrane vesicles for anchoring the replication complex. Suppresses IFN-I signaling and interferes with the function of autophagosomes in delivering virus fragments to lysosomes. |

NSP3 NSP4 | - | [52] [78] [74] [79] |

| NSP7 | 83 | 98.8 | 100 | Assembled into hexadecamer with NSP8 to form NSP7-NSP8-NSP12 core polymerase complex. NSP7-NSP8 serves as a primase for NSP12 polymerase activity. |

NSP12 NSP8 NSP9 orf7a orf7b |

+ | [52] [80] [13] [81] [82] |

| NSP8 | 198 | 97.5 | 99 | Assembled into hexadecamer with NSP7 to form NSP7-NSP8-NSP12 core polymerase complex. NSP7-NSP8 serves as a primase for NSP12 polymerase activity. |

NSP12 NSP7 NSP12 NSP13 M orf7b orf8 |

+ | [52] [13] [81] [80] |

| NSP9 | 113 | 97.3 | 98.2 | An ssRNA binding protein that plays a crucial role in viral replication through its dimer form. The substrate of the NSP12 NiRAN domain for NMPylation. |

Nsp8 Nsp12 NSP7 NSP16 orf7a orf10 |

+ | [52] [13] [83] [84] [85] |

| NSP10 | 139 | 97.1 | 99.3 | A cofactor of NSP14 and NSP16 that are necessary for cap formation and RNA 3′-end mismatch excision | NSP14NSP16 | - | [52] [13] [86] [87] |

| NSP11 | 13 | 84.6 | 92.3 | A disordered peptide whose function has not been recognized so far | - | - | [52] [88] |

| NSP12 | 932 | 96.4 | 98.3 | An RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) that needs NSP7-NSP8 hexadecamer as a primase. | NSP8 NSP16 orf7a orf10 |

- | [52] [13] [81] [89] [80] |

| NSP13 | 601 | 99.8 | 100 | A Zinc binding helicase in replication-transcription complex. Act as a triphosphatase that initiates the first step in viral mRNA capping. Inhibits interferon activation and NF-κB promoter signaling. |

Nsp12 NSP5 NSP8 NSP16 orf7a orf10 |

- | [52] [13] [90] [70] |

| NSP14 | 527 | 95.1 | 98.7 | A bifunctional enzyme is necessary for the capping of viral mRNA via SAM-dependent methyltransferase domain and exonuclease activity for RNA mismatch repair. Needs NSP10 as a cofactor |

NSP10 orf6 NSP10 |

- | [52] [13] [86] [87] |

| NSP15 | 346 | 88.7 | 95.7 | A uridine-specific endoribonuclease (endoU) is essential for viral RNA synthesis. Potent interferon antagonist |

NSP2 NSP16 orf7a orf10 | - | [52] [13] [91] [92] |

| NSP16 | 298 | A cap-synthesizing enzyme. Its 2′O-methyltransferases activity is necessary for viral RNA integrity. Needs NSP10 as a cofactor. |

NSP9 NSP10 NSP12 NSP13 NSP15 M N orf3a orf7a orf10 |

- | [52] [13] [93] |

||

| Structural proteins | |||||||

| M (orf5) | 222 | 90.5 | 96.4 | The major protein in the envelope that play role in virus assembly and budding. Participates in viral entry and replication. Specifies the shape of the envelope and stabilizes the other structural proteins. |

NSP2 NSP5 NSP8 NSP16 M S N orf7a orf7b orf6 orf10 |

+ | [52] [13] [94] |

| S (orf2) | 1273 | 76.3 | 87 | Binds with the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor in the lung and mediates virus entry to the host cell. | M | + | [52] [13] |

| N (orf9a) | 419 | 90.5 | 94.3 | Packages the RNA genome into a helical ribonucleocapsid (RNP) structure. Protects SARS-CoV-2 RNA from recognition and degradation by host antiviral defense (RNAi). An interferon-1 antagonist |

NSP4 NSP16 E M orf7a orf10 |

+ | [52] [13] [95] |

| E (orf4) | 75 | 94.7 | 96.1 | A small multifunctional protein that plays a central role in virus assembly. Hijacks cell junction proteins in the lung and mediates host immune responses. |

E M N orf3a orf9b |

+ | [52] [13] [96] |

| Accessory factors | |||||||

| orf3a | 275 | 72.4 | 85.1 | A viroporin involve in virion release. A strong inducer of caspase-dependent apoptosis. |

NSP4 NSP16 E orf7a orf7b orf10 | + | [52] [13] [97] [98] |

| orf3b | 22(truncated form) | 7.1 | 9.5 | An interferon-1 antagonist and the modulator of host cell signaling pathways. | ? | ? | [52] [99] [100] |

| orf6 | 61 | 66.7 | 85.7 | The strongest interferon antagonist among all SARS-CoV-2 proteins. | NSP14 M orf6 orf7a | + | [52] [13] [92] |

| orf7a | 121 | 85.2 | 90.2 | An immunomodulator factor for human CD14+ monocytes. Interferon antagonist |

NSP7 NSP9 NSP12NSP13 NSP15 NSP16 M N orf3a orf6 |

+ | [52] [13] [101] [102] |

| orf7b | 43 | 85.4 | 97.2 | Interfering with cellular processes like heart rhythm and epithelial damaging using its leucine zipper motif. Common symptoms of covid-19 such as impaired heart rhythm, odor loss, and limitation of oxygen uptake may be related to this accessory factor. |

NSP1 NSP2 NSP4 NSP7 NSP8 M orf3a |

+ | [13] [103] |

| orf8 | 121 | 28.5 | 45.3 | Mediates escape from the immune system via their role in decreasing the expression of surface MHC-I. Responsible for spike production and localization in new virion surface. |

NSP8 | - | [52] [13] [104] [105] [106] |

| orf9b | 97 | 72.4 | 84.7 | Mediates escape from the immune system via their role in manipulating mitochondria membrane proteins. Antagonizes cytokines involved in pro-inflammatory response and limits IFN-β production |

E | + | [52] [13] [107] [108] |

| orf9c | 73 | 74.0 | 78.1 | A transmembrane protein that antagonizes interferon signaling and other antiviral immune responses. Regulates protein degradation in the endoplasmic reticulum. |

? | ? | [109] [110] |

| orf10 | 38 | Does not have a homolog in SARS-CoV | Not essential for SARS-CoV-2 pathogenicity in humans. | NSP2 NSP5 NSP8 NSP9 NSP12 NSP13 NSP15 NSP16 M N orf3a |

+ | [13] [111] [112] |

|

7. Interactome of SARS-CoV-2 proteins

Like other viruses, SARS-CoV-2 makes multi-molecular protein complexes to develop pathogenicity. Li et al. (2021) discovered 58 intra-viral PPIs (heteromers) and some self-association of proteins (homomers) such as M, N, E, NSP2, NSP5, NSP8, orf6, orf7a, orf7b, orf9b, and orf10 [13].

Li et al. (2021) supposed that most of the inferred PPIs are from NSP interactions suggesting the importance of these proteins in the life cycle of the virus [13]. More than 65% of intra-viral PPIs associated with SARS-CoV-2 were not detected in SARS-CoV. This significant number of interactions appears to play an important role in the unique pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 [13]. The other interactions (20 of 58) were shared by SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. These shared intra-viral PPIs might be essential for the functioning of the members of the Coronaviridae family [13]. The role of every single SARS-CoV-2 protein in the pathogenicity of the virus and intra-viral PPIs are summarized in Table 3.

8. Hub proteins of SARS-CoV-2 which are identified by network analysis

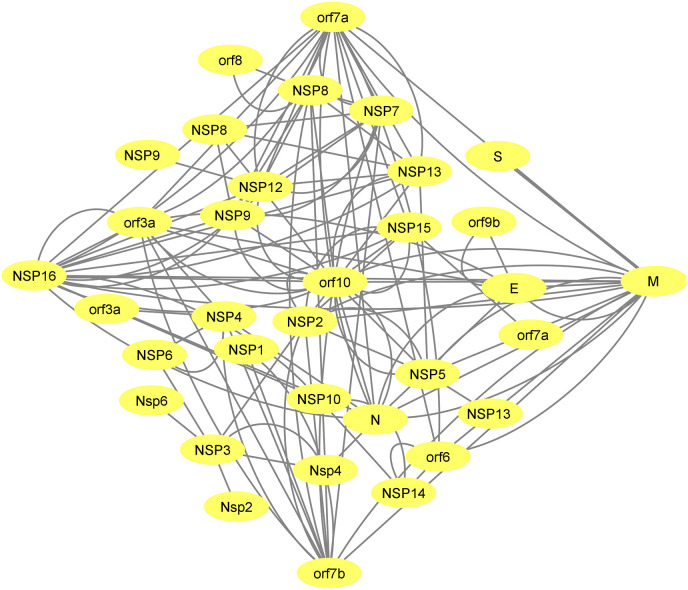

The SARS-CoV-2 genome codes for 32 structural and non-structural proteins. The interaction of these viral proteins with each other forms an intra-viral network which is shown in Fig. 2 . There are 8 PPIs between structural and accessory proteins (E-ORF3a, E-ORF9b M-ORF6, MORF7a, M-ORF7b, M-ORF10, N-ORF7a, and N-ORF10) and 6 PPIs between structural proteins and non-structural proteins. Among structural proteins, protein M has the maximum interactions in the intra-viral PPIs and has a connection with all of the other structural proteins (N, S and E). Among accessory proteins, ORF10 and NSP16 have the most interactions with non-structural proteins (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

SARS-CoV-2 protein-protein interactions were retrieved from the previously reported experimental method [13]. Orf10 followed by NSP16, M, orf7a and orf7b show a higher degree of intra-viral PPIs. The network was created using Cytoscape 3.8.

The degree value of nodes in the intra-viral network reveals a difference in the contribution of each viral member constructing the SARS-CoV-2 intra-viral network. ORF10 followed by M, NSP16, orf7a and, orf7b has a higher degree among other viral proteins and they are considered hubs in the network (Fig. 2). This suggests that they have a key role in the SARS-CoV-2 life cycle or pathogenicity.

Among these hubs, orf10 has maximum interactions with other SARS-CoV-2 proteins within the intra-viral network (Fig. 2). This protein is conserved in the SARS-CoV-2 and has no homolog in SARS-CoV; however, deletion of orf10 does not impact the replication and transmission capacity of SARS-CoV-2. Although orf10 was initially supposed to hijack the host protein CRL2ZYG11B, the proteomic studies showed that the binding of orf10 to the CRL2ZYG11B had no role in the pathogenicity of the virus [111]. Since the orf10 translation is low in the human cells and non-synonymous mutations in the orf10 gene emerge exponentially, some researchers concluded that the orf10 RNA sequence rather than the orf10 protein may play a regulatory role [113]. Considering the high degree of this protein in the intra-viral network (Fig. 2), it seems that further omics data is needed to determine the exact regulatory role of this protein in SARS-CoV-2 intra-viral interactions.

In the case of assessing the interaction of the hubs with each other without considering other nodes, M protein has the most interactions with other major hubs. (NSP16, orf7a, orf7b, and orf10).

9. Host proteins that interact with SARS-CoV-2 proteins

Gordon et al. (2020) attempted to predict human binding partners of 26 SARS-CoV-2 proteins using HEK293T cells as hosts for expressed viral proteins [52]. Using affinity-purification followed by mass-spectrometry, they reported 332 SARS-CoV-2-human PPIs. They characterized the viral proteins according to the function of their target proteins. They showed that a specific host cell pathway is not manipulated by a single viral protein and several viral proteins work together to target a pathway. In their study endomembrane compartments or vesicle trafficking pathways were targeted by approximately 40% of SARS-CoV-2-interacting proteins [52].

Li et al. (2021) analyzed three different sets of quantitative proteomics data and determined 295 high-confidence interactions among 286 cellular proteins and 29 virally encoded proteins [13]. In their study, the most frequent host-interacting proteins belonged to different cellular pathways including ATP biosynthesis and metabolic processes (M), mRNA transport (N), melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5) and retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) RNA sensing signaling (NSP1), nucleotide-excision repair (NSP4), protein methylation and alkylation (NSP5), translation initiation (NSP9), cellular amino acid metabolic process (NSP10), reactive oxygen species (ROS) metabolic process (NSP14), Golgi to plasma membrane transport (NSP16), endoplasmic reticulum stress (orf3a), and mRNA transport (orf6) [13].

Das et al. (2020) applied a codon usage similarity strategy to infer the CoV-2-Hu PPIs interactome [114]. They studied the detailed molecular mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis by deciphering the SARS-CoV-2 targeted human proteins participating in 17 different signaling pathways, namely TGF-beta, Jak-STAT, PI3K-Akt, MAPK, HIF-1, TNF, NF-kappa B, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, apoptosis, Th17 cell differentiation, chemokine, toll-like receptor, rIG-like receptor, IL-17, insulin signaling, mTOR, and adipocytokine signaling. Their findings predicted 9412 strong CoV-2-Hu PPIs that comprised 859 host proteins. Among these host proteins, 82 were connected with only one viral node whilst a total of 779 proteins were targeted by more than one viral protein. However, exploring the association of CoV-2-Hu PPIs with metabolic pathways showed that most of these proteins were involved in the PI3K-Akt pathway [114].

Stukalov et al. (2021) applied AP-MS technology and found 1484 links between 1086 cellular proteins in a wide range of metabolic pathways and 24 structural and nonstructural SARS-CoV-2 bait proteins. They realized that some protein interactions were specific to SARS-CoV-2 and were not seen in their homologs in SARS-CoV [115].

Some studies of CoV-2-host PPIs have been conducted at different tissue levels [116,117]. For instance, Feng et al. (2020) elucidated the tissue-specific feature of CoV-2-Hu crosstalk and revealed that each tissue has its unique network. They compared the cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 post 24 hits and realized that the size of the delineated networks was not the same in all tissues, for example, the liver and the heart had the highest and lowest edges in number respectively among all other studied tissues [118]. Some hubs were found in different tissues such as BRD4 and RIPK1 whilst other hubs were unique to particular human tissue (REEP5 for lung) indicating that designing the drug for SARS-CoV-2 is a complex process [118]. Khorsand et al. (2020) highlighted 727 interactions belonging to the CoV-2-Hu network mainly with interactions between 215 host proteins and viral proteins by applying the SARS-CoV-2-human PPIs three-layer network method [119]. This was followed by gene expression profiling of five COVID-19 positive patients via a comparative analysis between positive patients and negative controls. They defined the genes with log2 fold changes (overexpressed at least two times) as differentially expressed genes (DEGs). They identified 20 DEGs in the lung, 95 DEGs in the heart, 9 DEGs in the liver, 6 DEGs in the kidney, and 35 DEGs in the bowel. The outcome of their study showed that PPIs triggered by virus invasion and replication in host cells could be tissue-specific as each tissue had its particular PPI network structure [119].

In the present study, after retrieving PPIs data from the previously reported experimental methods, 2192 human proteins, which had the high-confidence PPIs with CoV-2 proteins, were collected for analysis (Supplementary file 1) [13,52,72,115,120].

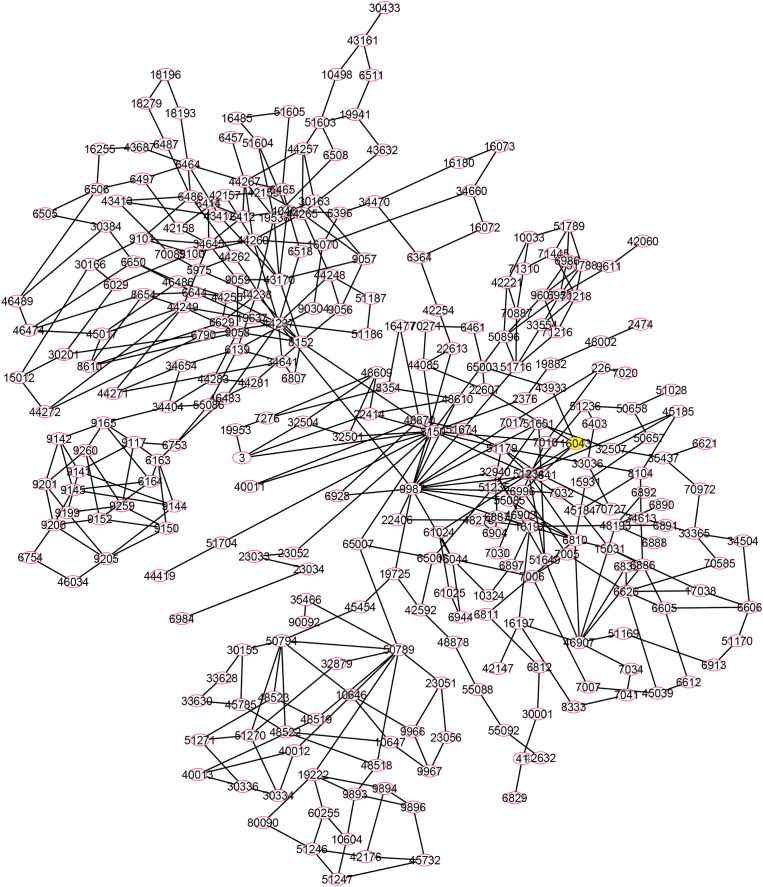

10. Gene ontology and network analysis of the host proteins in the response to SARS-CoV-2 infection

Gene Ontology (GO) is a biological information resource that provides computable data about the functions of the genes and gene products. GO analysis allows for the identification of the genes that significantly participate in the biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF) in biological systems [121]. In the present study, GO analysis identifies 162 biological processes (BPs) associated with 2192 CoV-2 interacted host proteins, which are used as input to the platform. As shown in Fig. 3 , human proteins in some biological processes had the most PPIs (>300) with the viral proteins, which include: cellular process, metabolic process, primary metabolic process, cellular metabolic process, macromolecule metabolic process, localization, transport, the establishment of localization, intra-Golgi vesicle-mediated transport, cellular macromolecule metabolic process, peptidyl-asparagine modification, protein amino acid N-linked glycosylation via asparagine, had the most PPIs (>300) with the viral proteins. The “cellular process” with 981 CoV-2 interacted with host proteins had the most proteins, and it was the first hit on the list (Supplementary file 2). The drugs which could block the proteins in the mentioned pathways would be more influential and potent against COVID-19/emerging disease.

Fig. 3.

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed on CoV-2-interacted host proteins. GO-terms for biological processes were obtained from the STRING database for analysis in the BiNGO tool: a Cytoscape plugin. Significant GO terms (5% FDR) were identified and further refined to select non-redundant terms.

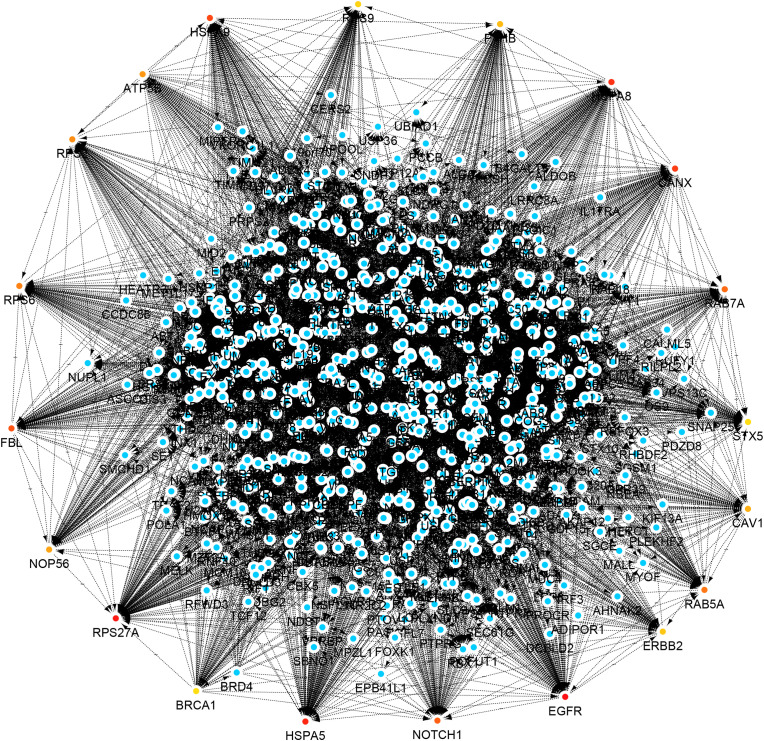

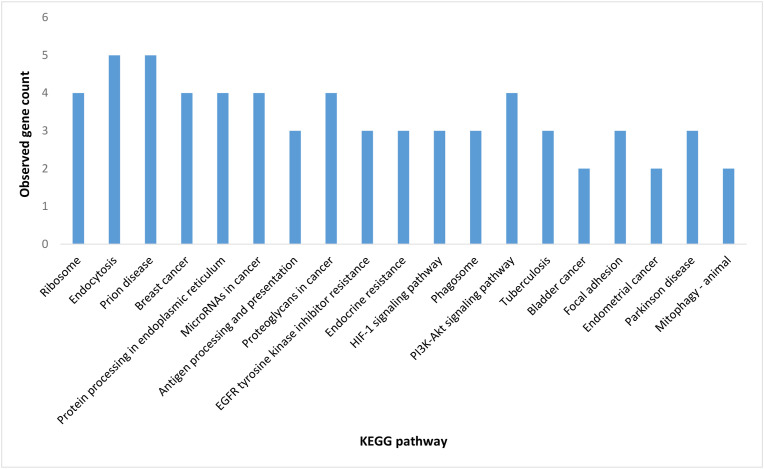

In the next step, SARS-CoV-2 target proteins were examined for their importance in their network, and the 20 proteins that revealed a high centrality score in the host network were depicted in Fig. 4 . These proteins included (with degree value shown within brackets): EGFR (169), RPS27A (164), HSPA5 (151), HSPA8 (149), CANX (133), HSPA9 (115), FBL (102), NOTCH1 (100), RAB7A (98), RAB5A (94), RPS6 (92), RPS2 (90), ATP5B (89), NOP56 (88), CAV1 (87), P4HB (85), ERBB2 (84), RPS9 (83), RPS8 (82) and BRCA1 (81). This was followed by applying the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database, which is composed of the PATHWAY, LIGAND, and GENES libraries, for further pathway analysis for mentioned 20 hosts hub proteins (Fig. 5 ) [122]. Accordingly, endocytosis and prion disease signaling pathways including 5 central proteins followed by proteoglycans in cancer and PI3K-Akt pathways including 4 central proteins, were the most crucial pathways post-SARS-CoV-2 infection. The central proteins of these pathways are potential targets from a pharmacology perspective for developing antiviral drugs.

Fig. 4.

Human protein interactors as a candidate for SARS-CoV-2 proteins collected from the previously reported experimental methods [13,52,72,115,120]. The network was created using Cytoscape 3.8. Red node: hub node that shows a higher degree of human-human PPIs.

Fig. 5.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways analysis was performed on the hub nodes of human-human PPIs [13,52,72,115,120]. The CytoKEGG plugin was used to import the pathways into the Cytoscape 3.8 software.

The highlights presented in this review were fairly consistent with Das et al. (2020) who explored the association of CoV-2-Hu PPIs with metabolic pathways and showed that most of the targeted proteins were involved in the PI3K-Akt pathway [114]. In their study PI3K-Akt and MAPK signaling pathways including 36 and 35 central proteins respectively, were shown as the most critical pathways post SARS-CoV-2 infection [114]. Different studies showed that viral proteins generally target those host proteins that are associated with multiple pathways to take over the human protein interactome [123,124]. As more than 600,000 PPIs are predicted to exist in the human interactome, it is supposed that targeting central proteins of PPI networks related to biological pathways is more common for the virus to manipulate host cell machinery [125]. For example, Das et al. (2021) reconstructed the CoV-2-Hu network by topology analysis of targeted proteins previously reported by Gordon et al. (2020); Li et al. (2021); Stukalov et al. (2020); and Cannataro and Harrison, (2021) [13,52,53,115,126]. They identified distinct host proteins that were targeted by 25 CoV-2 proteins. Accordingly, 4.4% of host proteins interacted most with viral proteins during the SARS-CoV-2 infection. These identified key host proteins were primarily associated with several crucial pathways, including cellular processes, signaling transduction and neurodegenerative diseases [53]. Guzzi et al. (2020) assessed human master regulator proteins that induced similar responses upon beta-coronavirus infections [127]. They have provided a CoV-2-Hu interactome that includes 125 proteins (94 human host proteins and 31 viral proteins) and 200 interactions. They found that eight proteins (ACE2, DCTN2, MCL1, EEF1A1, NDUFA10, RNF128, DEAD-box polypeptide 5 and EIF4B) were affected most by the viral infection and then influenced the rest of the cellular proteins. These authors also declared that the majority of these proteins functioned as part of mitochondrial or apoptotic pathways except ACE2, which is involved in directing the virus into the host cell, [127]. Feng et al. (2020) constructed a tissue-specific SARS-CoV-2 interactome and evaluated both common and specific hubs related to different tissues [118]. They have found that targeted host proteins were not necessarily the same in different tissues, some of the proteins were tissue-specific hubs like REEP5 which is responsible for reprogramming the tissue metabolic processes. Whilst the other hubs such as BRD4 and RIPK1, which were found in multiple tissues, are potentially important targets for developing drugs and preventing the inflammation of different tissues [118].

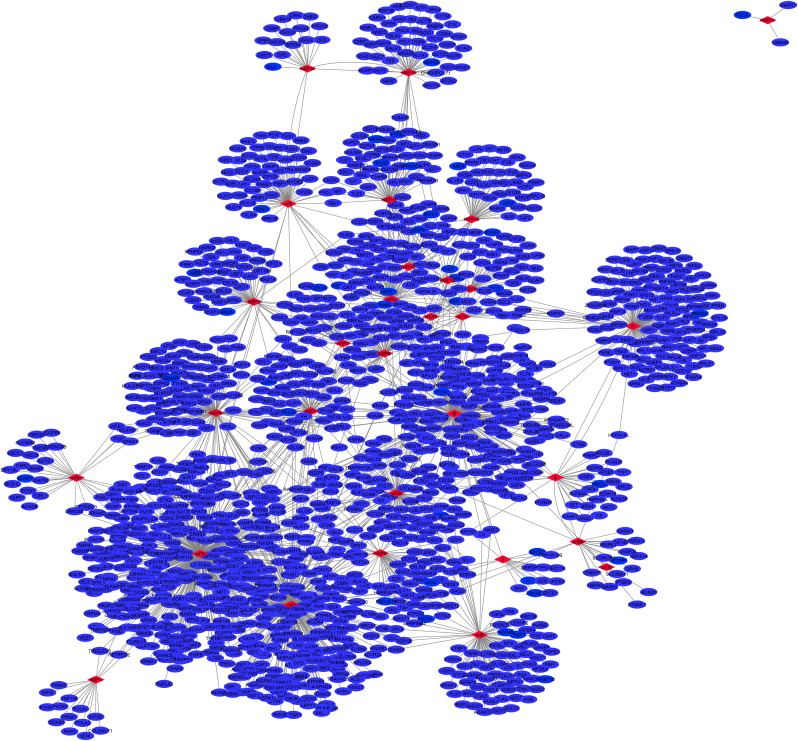

11. CoV-2-host PPIs network

CoV-2-host PPIs network consists of 2192 human proteins interacting with 27 CoV-2 viral proteins (Fig. 6 and Supplementary file 2). As previously mentioned, orf10 followed by NSP16, M, orf7a, and orf7b show a higher degree in the CoV-2 intra-viral network. This information shows that these proteins have a significant role in proteins communication and CoV-2 survival. Interestingly, the high degree proteins in the intra-viral network (orf10, NSP16, M, orf7a and orf7b) are different from the high degree viral proteins in the CoV-2-Hu PPI network (orf7b, orf3, M, N and NSP6). This difference revealed that the virus codes for a unique subnetwork to induce pathogenicity (Fig. 6). Additionally, most of the hub proteins in the host network were targeted by the viral proteins that were hubs in the intra-viral network (Fig. 3). For example, the host hub EGFR had the highest number of links with the viral hub orf7b. Moreover, host hub RAB7A and ERBB2 interacted with viral hub orf7b; HSPA9, RPS6, RPS2, NOP56, RPS9, RPS8, and FBL, interacted with N; NOTCH1 and RAB5A interacted with orf3; ATP5B and CAV1 interacted with NSP6. All of the targeted host proteins participate as hubs in host PPIs. We concluded that to manipulate the host cells, the virus must initiate a unique subnetwork to target some host proteins that are very important and participate as hubs in their network.

Fig. 6.

Merge of SARS-CoV-2 proteins network and human proteins network showing network for network theory. Intra-viral and Hu-CoV-2 protein interactions were experimentally verified in previously published data [13,52,115,120]. The network was created using Cytoscape 3.8. Blue node: human protein. Red node: virus protein.

This viral strategy in which a small number of viral proteins interact with the central proteins in the host has been demonstrated by other studies. For instance, Diaz (2020) revealed that more than half of the host nodes (59.7%) were affected by only six viral proteins (orf8, M, Nsp7, orf9c, NSP12, and NSP13) and among these viral proteins, three of them (orf8, M, and Nsp7) had the most links (102) [128]. This author reported that the network of SARS-CoV-2 proteins has a hierarchical, efficient, robust structure and scale-free topology with significant viral hubs (orf8, M, and NSP7) that manipulate host proteins in a completely programmed manner [74,75].

In our findings, proteins M and orf7b participate as hubs in both intra-viral and CoV-2-Hu PPIs networks suggesting that they play a significant role both in the internal communication of viral proteins and disruption of the host cells and pathogenicity. This is consistent with another study by Das et al. (2021) who showed the SARS-CoV-2 orf7b and M have the most links with the host proteins [53]. Another study base on the analysis of human lung, colon, kidney, liver, and heart proteomes, revealed that tissue-specific hubs often interacted with SARS-CoV-2 proteins including E, N, M, NSP7, NSP8, NSP12, and NSP13 but lung hubs specifically used viral M protein for interacting [118]. Li et al. (2021) have performed the experimental approaches to delineate the SARS-CoV-2/Hu interactome and concluded that the most typical hubs for SARS-CoV-2-human host PPIs are ORF1b (coding for nsp1-16) followed by orf3, M, N [13].

12. Network for network theory of CoV-2-host PPIs

Many attempts have been made so far to further knowledge of the mechanism behind pathogenesis and manipulation of the host's cells by zoonotic viruses, especially SARS-CoV-2. To perceive the mystery behind the viral infection and trigger an effective immune response in plants, the “gene for gene” hypothesis has been proposed for viral diseases. The “gene for gene” idea was first mentioned in plants' resistance (R) genes that confer recognition of corresponding genes for avirulence (Avr) proteins in the pathogen [67,129]. Although many plants developed immunity through the R gene, in some cases no R-Avr combinations were found, indicating that the induction of immunity in plants by the Avr proteins must be indirect [130,131]. With remarkable advancements in constructing virus-host PPI networks using the bioinformatics approaches, it seems that the putative principle of the “gene-for-gene hypothesis” needs to be revised. Recent studies of the SARS-CoV-2 interactome showed that viral proteins not only manipulate specific host proteins but also interact with various host proteins. These host proteins were pathway-central and directed many metabolic pathways. Based on this phenomenon, within a virus-host network, there is a viral subnetwork of proteins that interacts with its host targets in which the loss of a node does not mean the loss of the entire subnetwork. In this scenario, viral proteins take over their neighbor's dysfunction by targeting another protein from the host that performs a similar role in that pathway. Despite the low clustering coefficient value of all nodes in CoV-2-host PPIs, it could be suggested that viral proteins did not interact directly with each other and they enhanced their effects when converged toward the particular cellular process [52,128,132]. To design antiviral therapies, not only the main viral node must be blocked, but also the other proteins that are synergistic with this node must be attacked simultaneously [128]. Hoffman et al. (2021) previously screened interacting host proteins essential for infection of SARS-CoV-2 [133]. They found that viral proteins select their targets based on their functions. Multiple viral factors form complexes with host members in the same pathway called “complementary behavior”. For example, viral orf9c and orf8 proteins have interacted with different but functionally related host factors (SCAP and NPC2 in cholesterol homeostasis) [133]. Functional overlapping of viral proteins was also detected by Gordon et al. (2020) who found that different viral proteins manipulated various key centers of a particular pathway during SARS-CoV-2 infection [52]. For example, Nsp13 and orf9c both interacted with essential players in NF-kB signaling and orf3a and Nsp9 deactivated two E3 ubiquitin ligases (TRIM59 and MIB1) to down-regulate antiviral innate immune signaling [52]. The factor of “distribution” is also important for SARS-COV-2 pathogenicity which is based on the “power-law” concept. This concept means a limited number of target proteins have control over the pathways and specific groups of viral proteins interacted with these few top centers. For example, (with degree value shown within parentheses) MYC (2843), TRIM25 (2656), EGFR (2452), BRCA1 (2236), MDM2 (2219), NTRK1 (2030), KRAS (1944), ELAVL1 (1914) and HSP90AA1 (1734) were targeted by core viral enzymes such as Nsp2, Nsp3, Nsp4, Nsp5, Nsp8, NSP10, NSP12, NSP13 [114].

Liu et al. (2014) demonstrated accessory proteins of coronaviruses often function by forming sets of interactions, rather than individually [14]. Hence, the simultaneous deletion of multiple accessory genes might be a promising strategy for the development of a live attenuated vaccine [14]. The theory of targeting a viral/host subnet as a way to discover anti-COVID-19 therapies might be a platform to address questions linked to the viral pathogenicity such as i) what does the difference in the number of accessory genes from various coronaviruses mean and is this related to the diversity of the hosts of coronaviruses? ii) were the functions of the absent accessory proteins compensated by other viral proteins? [134]. The study of the viral perturbation mechanism of host cells has shown that a group of target proteins was also used as targets among other members of the viral family or across multiple species [127,135]. Further knowledge on host factors that are commonly manipulated among different viruses helps us to know that targeting a group of central host proteins can prevent other related infections or even different diseases. In addition to SARS-CoV-2, Das et al. (2021) studied the PPIs of other viruses that interacted with 64 key host proteins [53]. The outcome of their study indicated that the majority of the top target host proteins are also involved in other viruses’ pathogenesis [53]. Therefore, to combat COVID-19, we need to use recently emerging polypharmacology science and design efficient drugs to bind a certain number of key proteins to affect multiple biological processes simultaneously.

In this regard, Mohamed et al. (2021) reviewed the best-documented dual and multi-target drugs for COVID-19 therapy. They evaluated articles that used computational methods for drug repurposings such as docking tools combined with the analysis of molecular dynamics simulation and multi-target assessment with the help of drug databases [58]. They presented the list of drugs such as Atazanavir that could target up to six SARS-CoV-2 proteins, Ritonavir, Raltegravir, Darunavir, and Grazoprevir for targeting five, and Lopinavir, Asunaprevir, Lomibuvir, and Boceprevir for blocking four SARS-CoV2 proteins. Helicase, exonuclease, endoRNAse, PLP, and 3CLP were the most commonly affected proteins [58]. The above-mentioned antiviral drugs primarily treat other viral infections such as HIV, HCV, HBV, HSV, CMV, and Ebola.

13. Conclusion

Providing a wide window of the human molecular landscape when responding to the SARS-CoV-2 infection via network medicine analysis and proteoinformatics can suggest new approaches for a drug repurposing strategy. The host-oriented intervention for designing antiviral drugs has currently a high reputation in overcoming the viral mutations that cause drug resistance and pan-viral therapies as we prepare for the next pandemic. Identification of host proteins that are already targeted by existing drugs can provide in-depth insights into the host dependencies of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In addition, PPIs studies and determination of the key genes/proteins involved in the different biological pathways lead to i) further knowledge on the characterization of disease progression [[136], [137], [138], [139]], ii) guides for future experimental research, iii) cross-species predictions for efficient interaction mapping to assign the function to uncharacterized gene products that might be involved in response to the viral infections [137,140]. Furthermore, the topology and pathway enrichment analysis of important host PPI networks can determine the potential key viral interacting host proteins associated with disease pathways, and highly central host proteins that might influence the whole PPI network. Emerging the vaccine-escape and fast-growing mutations including D614G also confers increased efficiency of SARS-CoV-2 cell entry, S494P, Q493L, K417 N, F490S, F486L, R403K, E484K, L452R, K417T, F490L, E484Q, and A475S has prompted scientists to investigate the targeting potential of the hub proteins like orf8, M, and NSP7 that have previously shown the most edges (link) within viral/host interactome [141,142].

Whether the principles of “network for network” can be accepted for SARS-COV-2 or not, it broadens our perspective of the need for anti-COVID-19 therapeutic interventions to specifically target the viral/host subnets. Based on recent PPI network studies of SARS-COV2, the future directions toward more efficient vaccine design approaches must focus on targeting and blockage not only the key proteins in the viral network such as the hubs or higher betweenness-value nodes but also proteins that act synergistically within a viral-host PPI network.

Compliance with ethical standards

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The research reported here did not involve experimentation with human participants or animals.

Author contributions

AG designed the study and analyzed the data; NE and AG drafted the manuscript. AT and NF analyzed the data. AG, KI, JD, PHG and SS edited and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105575.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Figures K. 2022. Weekly Operational Update on COVID-19; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghorbani A., Samarfard S., Eskandarzade N., Afsharifar A., Eskandari M.H., Niazi A., Izadpanah K., Karbanowicz T.P. Comparative phylogenetic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein—possibility effect on virus spillover. Briefings Bioinf. 2021;22:1–9. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbab144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . vols. 1–23. World Heal. Organ; 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-weekly-epidemiological-update (COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update). [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO . vol. 19. 2021. https://covid19.who.int/ (Weekly Epidemiological Update). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghorbani A., Samarfard S., Jajarmi M., Bagheri M., Karbanowicz T.P., Afsharifar A., Eskandari M.H., Niazi A., Izadpanah K. Highlight of potential impact of new viral genotypes of SARS-CoV-2 on vaccines and anti-viral therapeutics. Gene Rep. 2022;26:101537. doi: 10.1016/j.genrep.2022.101537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Wit E., Van Doremalen N., Falzarano D., Munster V.J. SARS and MERS: recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;14:523–534. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altay O., Mohammadi E., Lam S., Turkez H., Boren J., Nielsen J., Uhlen M., Mardinoglu A. Current status of COVID-19 therapies and drug repositioning applications. iScience. 2020;23:101303. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghorbani A., Samarfard S., Ramezani A., Izadpanah K., Afsharifar A., Eskandari M.H., Karbanowicz T.P., Peters J.R. Quasi-species nature and differential gene expression of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 and phylogenetic analysis of a novel Iranian strain. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020;85:104556. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J., Shu H., Liu H., Wu Y., Zhang L., Yu Z., Fang M., Yu T. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan J.F.-W., Kok K.-H., Zhu Z., Chu H., To K.K.-W., Yuan S., Yuen K.-Y. Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human-pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan, Emerg. Microb. Infect. 2020;9:221–236. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1719902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., Chen Y.-M., Wang W., Song Z.-G., Hu Y., Tao Z.-W., Tian J.-H., Pei Y.-Y. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rando H.M., MacLean A.L., Lee A.J., Ray S., Bansal V., Skelly A.N., Sell E., Dziak J.J., Shinholster L., McGowan L.D. ArXiv; 2021. Pathogenesis, Symptomatology, and Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 through Analysis of Viral Genomics and Structure. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J., Guo M., Tian X., Wang X., Yang X., Wu P., Liu C., Xiao Z., Qu Y., Yin Y. Virus-host interactome and proteomic survey reveal potential virulence factors influencing SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Med. 2021;2:99–112. doi: 10.1016/j.medj.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu D.X., Fung T.S., Chong K.K.-L., Shukla A., Hilgenfeld R. Accessory proteins of SARS-CoV and other coronaviruses. Antivir. Res. 2014;109:97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee J.-G., Huang W., Lee H., van de Leemput J., Kane M.A., Han Z. Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 proteins reveals Orf6 pathogenicity, subcellular localization, host interactions and attenuation by Selinexor. Cell Biosci. 2021;11:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13578-021-00568-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serafin M.B., Bottega A., Foletto V.S., da Rosa T.F., Hörner A., Hörner R. Drug repositioning is an alternative for the treatment of coronavirus COVID-19. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;55:105969. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris M., Bhatti Y., Buckley J., Sharma D. Fast and frugal innovations in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Med. 2020;26:814–817. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0889-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guy R.K., DiPaola R.S., Romanelli F., Dutch R.E. Rapid repurposing of drugs for COVID-19. Science (80-.) 2020;368:829–830. doi: 10.1126/science.abb9332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nosengo N. Can you teach old drugs new tricks? Nat. News. 2016;534:314. doi: 10.1038/534314a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naylor D.M., Kauppi D.M., Schonfeld J.M. Therapeutic drug repurposing, repositioning and rescue. Drug Discov. 2015;57 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarada T.N., Rokne J.G., Alhajj R. A review of computational drug repositioning: strategies, approaches, opportunities, challenges, and directions. J. Cheminf. 2020;12:1–23. doi: 10.1186/s13321-020-00450-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuffenhauer A., Floersheim P., Acklin P., Jacoby E. Similarity metrics for ligands reflecting the similarity of the target proteins. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003;43:391–405. doi: 10.1021/ci025569t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiang A.P., Butte A.J. Systematic evaluation of drug–disease relationships to identify leads for novel drug uses. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;86:507–510. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Z., Yao Y., Cheng X., Chen Q., Zhao W., Ma S., Li Z., Zhou H., Li W., Fei T. A computational framework of host-based drug repositioning for broad-spectrum antivirals against RNA viruses. iScience. 2021;24:102148. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanoli Z., Seemab U., Scherer A., Wennerberg K., Tang J., Vähä-Koskela M. Exploration of databases and methods supporting drug repurposing: a comprehensive survey, Brief. Bioinform. 2021;22:1656–1678. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo H., Li M., Yang M., Wu F.-X., Li Y., Wang J. Biomedical data and computational models for drug repositioning: a comprehensive review. Briefings Bioinf. 2021;22:1604–1619. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbz176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pushpakom S., Iorio F., Eyers P.A., Escott K.J., Hopper S., Wells A., Doig A., Guilliams T., Latimer J., McNamee C. Drug repurposing: progress, challenges and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18:41–58. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hosseini M., Chen W., Xiao D., Wang C. Computational molecular docking and virtual screening revealed promising SARS-CoV-2 drugs, Precis. Clin. Med. 2021;4:1–16. doi: 10.1093/pcmedi/pbab001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morse J.S., Lalonde T., Xu S., Liu W.R. Learning from the past: possible urgent prevention and treatment options for severe acute respiratory infections caused by 2019‐nCoV. Chembiochem. 2020;21:730. doi: 10.1002/cbic.202000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mei M., Tan X. Current strategies of antiviral drug discovery for COVID-19. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021;8:310. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2021.671263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mishra A., Rathore A.S. RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) as a drug target for SARS-CoV2. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021:1–13. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2021.1875886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Acharya C., Coop A., Polli J.E., D MacKerell A. Recent advances in ligand-based drug design: relevance and utility of the conformationally sampled pharmacophore approach. Curr. Comput. Aided Drug Des. 2011;7:10–22. doi: 10.2174/157340911793743547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masoudi-Sobhanzadeh Y., Omidi Y., Amanlou M., Masoudi-Nejad A. Drug databases and their contributions to drug repurposing. Genomics. 2020;112:1087–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2019.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menestrina L., Cabrelle C., Recanatini M. BioRxiv; 2021. COVIDrugNet: a Network-Based Web Tool to Investigate the Drugs Currently in Clinical Trial to Contrast COVID-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu F., Patumcharoenpol P., Zhang C., Yang Y., Chan J., Meechai A., Vongsangnak W., Shen B. Biomedical text mining and its applications in cancer research. J. Biomed. Inf. 2013;46:200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koutrouli M., Karatzas E., Paez-Espino D., Pavlopoulos G.A. A guide to conquer the biological network era using graph theory. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020;8:34. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Saleem J., Granet R., Ramakrishnan S., Ciancetta N.A., Saveson C., Gessner C., Zhou Q. Knowledge graph-based approaches to drug repurposing for COVID-19. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021;61:4058–4067. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bajpai A.K., Davuluri S., Tiwary K., Narayanan S., Oguru S., Basavaraju K., Dayalan D., Thirumurugan K., Acharya K.K. Systematic comparison of the protein-protein interaction databases from a user's perspective. J. Biomed. Inf. 2020;103:103380. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2020.103380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Chassey B., Meyniel-Schicklin L., Vonderscher J., André P., Lotteau V. Virus-host interactomics: new insights and opportunities for antiviral drug discovery. Genome Med. 2014;6:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13073-014-0115-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas S., Bonchev D. A survey of current software for network analysis in molecular biology. Hum. Genom. 2010;4:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-4-5-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N.S., Wang J.T., Ramage D., Amin N., Schwikowski B., Ideker T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Artika I.M., Dewantari A.K., Wiyatno A. Heliyon; 2020. Molecular Biology of Coronaviruses: Current Knowledge. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kruse T., Benz C., Garvanska D.H., Lindqvist R., Mihalic F., Coscia F., Inturi R., Sayadi A., Simonetti L., Nilsson E. Large scale discovery of coronavirus-host factor protein interaction motifs reveals SARS-CoV-2 specific mechanisms and vulnerabilities. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26498-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng L.-L., Li C., Ping J., Zhou Y., Li Y., Hao P. The domain landscape of virus-host interactomes. BioMed Res. Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/867235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brito A.F., Pinney J.W. Protein–protein interactions in virus–host systems. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:1557. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ivanov S., Lagunin A., Filimonov D., Tarasova O. Network-based analysis of OMICs data to understand the HIV–host interaction. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:1314. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khorsand B., Savadi A., Zahiri J., Naghibzadeh M. Alpha influenza virus infiltration prediction using virus-human protein–protein interaction network. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2020;17:3109–3129. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2020176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang C.-H., Li H.-C., Hung C.-H., Lo S.-Y. Coronaviruses. Springer; 2015. Studying coronavirus–host protein interactions; pp. 197–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang S., Huang W., Ren L., Ju X., Gong M., Rao J., Sun L., Li P., Ding Q., Wang J. Comparison of viral RNA–host protein interactomes across pathogenic RNA viruses informs rapid antiviral drug discovery for SARS-CoV-2. Cell Res. 2021:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41422-021-00581-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calderwood M.A., Venkatesan K., Xing L., Chase M.R., Vazquez A., Holthaus A.M., Ewence A.E., Li N., Hirozane-Kishikawa T., Hill D.E. Epstein–Barr virus and virus human protein interaction maps. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007;104:7606–7611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702332104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fields S., Song O. A novel genetic system to detect protein–protein interactions. Nature. 1989;340:245–246. doi: 10.1038/340245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gordon D.E., Jang G.M., Bouhaddou M., Xu J., Obernier K., White K.M., O'Meara M.J., Rezelj V.V., Guo J.Z., Swaney D.L. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature. 2020;583:459–468. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Das J.K., Roy S., Guzzi P.H. Analyzing host-viral interactome of SARS-CoV-2 for identifying vulnerable host proteins during COVID-19 pathogenesis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2021;93:104921. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2021.104921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Long J., Wright E., Molesti E., Temperton N., Barclay W. vol. 4. 2015. (Antiviral Therapies against Ebola and Other Emerging Viral Diseases Using Existing Medicines that Block Virus Entry). F1000Research. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ghorbani A., Hadifar S., Salari R., Izadpanah K., Burmistrz M., Afsharifar A., Eskandari M.H., Niazi A., Denes C.E., Neely G.G. A short overview of CRISPR-Cas technology and its application in viral disease control. Transgenic Res. 2021;30:221–238. doi: 10.1007/s11248-021-00247-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stebbing J., Krishnan V., de Bono S., Ottaviani S., Casalini G., Richardson P.J., Monteil V., Lauschke V.M., Mirazimi A., Youhanna S. Mechanism of baricitinib supports artificial intelligence‐predicted testing in COVID‐19 patients. EMBO Mol. Med. 2020;12 doi: 10.15252/emmm.202012697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pavel A., Del Giudice G., Federico A., Di Lieto A., Kinaret P.A.S., Serra A., Greco D. Integrated network analysis reveals new genes suggesting COVID-19 chronic effects and treatment. Briefings Bioinf. 2021;22:1430–1441. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mohamed K., Yazdanpanah N., Saghazadeh A., Rezaei N. Computational drug discovery and repurposing for the treatment of COVID-19: a systematic review. Bioorg. Chem. 2021;106:104490. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chaudhuri S., Symons J.A., Deval J. Innovation and trends in the development and approval of antiviral medicines: 1987–2017 and beyond. Antivir. Res. 2018;155:76–88. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Clercq E., Li G. Approved antiviral drugs over the past 50 years. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016;29:695–747. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00102-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tzou P.L., Tao K., Nouhin J., Rhee S.-Y., Hu B.D., Pai S., Parkin N., Shafer R.W. Coronavirus antiviral research database (CoV-RDB): an online database designed to facilitate comparisons between candidate anti-coronavirus Compounds. Viruses. 2020;12:1006. doi: 10.3390/v12091006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gordon C.J., Tchesnokov E.P., Feng J.Y., Porter D.P., Götte M. The antiviral compound remdesivir potently inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:4773–4779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.AC120.013056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xiong R., Zhang L., Li S., Sun Y., Ding M., Wang Y., Zhao Y., Wu Y., Shang W., Jiang X. BioRxiv; 2020. Novel and potent inhibitors targeting DHODH, a rate-limiting enzyme in de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis, are broad-spectrum antiviral against RNA viruses including newly emerged coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zumla A., Chan J.F.W., Azhar E.I., Hui D.S.C., Yuen K.-Y. Coronaviruses—drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016;15:327–347. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.de Chassey B., Meyniel-Schicklin L., Aublin-Gex A., André P., Lotteau V. New horizons for antiviral drug discovery from virus–host protein interaction networks. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012;2:606–613. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lythgoe M.P., Middleton P. Ongoing clinical trials for the management of the COVID-19 pandemic. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2020;41:363–382. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Flor H.H. Current status of the gene-for-gene concept. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1971;9:275–296. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yoshimoto F.K. The proteins of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS CoV-2 or n-COV19), the cause of COVID-19. Protein J. 2020;39:198–216. doi: 10.1007/s10930-020-09901-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang K., Miorin L., Makio T., Dehghan I., Gao S., Xie Y., Zhong H., Esparza M., Kehrer T., Kumar A. Nsp1 protein of SARS-CoV-2 disrupts the mRNA export machinery to inhibit host gene expression. Sci. Adv. 2021;7 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe7386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vazquez C., Swanson S.E., Negatu S.G., Dittmar M., Miller J., Ramage H.R., Cherry S., Jurado K.A. SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins NSP1 and NSP13 inhibit interferon activation through distinct mechanisms. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cornillez-Ty C.T., Liao L., Yates J.R., III, Kuhn P., Buchmeier M.J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nonstructural protein 2 interacts with a host protein complex involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and intracellular signaling. J. Virol. 2009;83:10314–10318. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00842-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Davies J.P., Almasy K.M., McDonald E.F., Plate L. Comparative multiplexed interactomics of SARS-CoV-2 and homologous coronavirus nonstructural proteins identifies unique and shared host-cell dependencies. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020;6:3174–3189. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Graham R.L., Sims A.C., Baric R.S., Denison M.R. The Nidoviruses. Springer; 2006. The nsp2 proteins of mouse hepatitis virus and SARS coronavirus are dispensable for viral replication; pp. 67–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sakai Y., Kawachi K., Terada Y., Omori H., Matsuura Y., Kamitani W. Two-amino acids change in the nsp4 of SARS coronavirus abolishes viral replication. Virology. 2017;510:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2017.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mielech A.M., Chen Y., Mesecar A.D., Baker S.C. Nidovirus papain-like proteases: multifunctional enzymes with protease, deubiquitinating and deISGylating activities. Virus Res. 2014;194:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Scott B.M., Lacasse V., Blom D.G., Tonner P.D., Blom N.S. 2021. Predicted Coronavirus Nsp5 Protease Cleavage Sites in the Human Proteome: A Resource for SARS-CoV-2 Research, BioRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Roe M.K., Junod N.A., Young A.R., Beachboard D.C., Stobart C.C. Targeting novel structural and functional features of coronavirus protease nsp5 (3CLpro, Mpro) in the age of COVID-19. J. Gen. Virol. 2021:1558. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Benvenuto D., Angeletti S., Giovanetti M., Bianchi M., Pascarella S., Cauda R., Ciccozzi M., Cassone A. Evolutionary analysis of SARS-CoV-2: how mutation of Non-Structural Protein 6 (NSP6) could affect viral autophagy. J. Infect. 2020;81 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.058. e24–e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xia H., Cao Z., Xie X., Zhang X., Chen J.Y.-C., Wang H., Menachery V.D., Rajsbaum R., Shi P.-Y. Evasion of type I interferon by SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep. 2020;33:108234. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peng Q., Peng R., Yuan B., Zhao J., Wang M., Wang X., Wang Q., Sun Y., Fan Z., Qi J. Structural and biochemical characterization of the nsp12-nsp7-nsp8 core polymerase complex from SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep. 2020;31:107774. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kirchdoerfer R.N., Ward A.B. Structure of the SARS-CoV nsp12 polymerase bound to nsp7 and nsp8 co-factors. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10280-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhai Y., Sun F., Li X., Pang H., Xu X., Bartlam M., Rao Z. Insights into SARS-CoV transcription and replication from the structure of the nsp7–nsp8 hexadecamer. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:980–986. doi: 10.1038/nsmb999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]