Abstract

Caspofungin (Merck Pharmaceuticals) was tested in vitro against 25 clinical isolates of Coccidoides immitis. In vitro susceptibility testing was performed in accordance with the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards document M38-P guidelines. Two C. immitis isolates for which the caspofungin MICs were different were selected for determination of the minimum effective concentration (MEC), and these same strains were used for animal studies. Survival and tissue burdens of the spleens, livers, and lungs were used as antifungal response markers. Mice infected with strain 98-449 (48-h MIC, 8 μg/ml; 48-h MEC, 0.125 μg/ml) showed 100% survival to day 50 when treated with caspofungin at ≥1 mg/kg. Mice infected with strain 98-571 (48-h MIC, 64 μg/ml; 48-h MEC, 0.125 μg/ml) displayed ≥80% survival when the treatment was caspofungin at ≥5 mg/kg. Treatment with caspofungin at 0.5, 1, 5, or 10 mg/kg was effective in reducing the tissue fungal burdens of mice infected with either isolate. When tissue fungal burden study results were compared between strains, caspofungin showed no statistically significant difference in efficacy in the organs of the mice treated with both strains. A better in vitro-in vivo correlation was noted when we used the MEC instead of the MIC as the endpoint for antifungal susceptibility testing. Caspofungin may have a role in the treatment of coccidioidomycosis.

Coccidioides immitis is the etiologic agent of coccidioidomycosis. The fungus lives in the soil of arid regions of the United States, Mexico, and Central and South America. There are an estimated 100,000 infections annually in the United States (17). Coccidioidomycosis is a systemic fungal infection and is frequently refractory to treatment. Unfortunately, conventional antifungal therapy is associated with therapeutic failures, relapses, and toxicity (5, 7, 8, 18). However, there is some hope that major improvements in therapy for coccidioidomycosis will come from drugs with novel mechanisms of action.

The fungal cell wall is a vital and complex structure containing mannoproteins, chitin, and glucans. Any disruption in its integrity should affect growth. The cell wall provides a unique therapeutic opportunity for antifungal agents by targeting a structure not found in mammalian cells.

The echinocandins are cyclic hexapeptides, members of a new class of antifungal agents. They appear to inhibit the synthesis of 1,3-β-d-glucan, a major cell wall component which provides structural integrity and osmotic stability in most pathogenic fungi (2, 14). Caspofungin (CAS), previously known as L-743,872 or MK-0991, is a semisynthetic derivative of the natural product pneumocandin B0 (L-688-786) (4; F. A. Bouffard, J. F. Dropinski, J. M Balkovec, R. M. Black, M. L. Hammond, K. H. Nollstadt, and S. Dreikorn, Abstr. 36th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-27, 1996). CAS has displayed potent in vitro activity against Candida species, including amphotericin B (AMB)- and fluconazole (FLU)-resistant isolates; Aspergillus species; and other clinically important molds, such as Alternaria spp., Curvularia lunata, Paecilomyces variotii, Scedosporium apiospermum, and dimorphic fungal pathogens (3; A. Espinel-Ingroff, Abstr. 36th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-31, 1996; A. M. Flattery, P. S. Hicks, A. Wilcox, and H. Rosen, Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. J-936, 2000; A. Fothergill, D. A. Sutton, and M. G. Rinaldi, Abstr. 36th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-29, 1996; P. W. Nelson, M. Lozano-Chiu, and J. H. Rex, Abstr. 36th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-28, 1996; P. S. Hicks, K. L. Dorso, L. S. Gerckens, L. P. Lynch, P. Sinclair, D. L. Shungu, D. Suber, A. Wilcox, B. A. Pelak, and H. Rosen, Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. J-193, 2000; J. A. Vazquez, D. Boikov, M. E. Lynch, and J. D. Sobel, Abstr. 36th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-30, 1996). However, CAS has poor inhibitory activity against Cryptococcus neoformans, Trichosporon beigelii, Rhizopus arrhizus, Fusarium spp., Paecilomyces lilacinus, and Scedosporium prolificans (3; Espinel-Ingroff, 36th ICAAC; Fothergill et al., 36th ICAAC). In animal studies, this pneumocandin showed excellent antifungal activity for the treatment of disseminated aspergillosis, candidiasis (1, 9), histoplasmosis (10), and Pneumocystis carinii infection (M. A. Powles, J. Anderson, P. Liberator, and D. M. Schmatz, Abstr. 36th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-42, 1996). Maertens et al. (J. Maertens, I. Raad, C. A. Sable, A. Ngai, R. Berman, T. F. Patterson, D. Denning, and T. Walsh, Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. J-1103, 2000) treated inmunocompromised patients with invasive aspergillosis refractory or intolerant to AMB, AMB lipid formulations, and azoles. The results demonstrated >40% efficacy of CAS in this salvage setting. At present, CAS is licensed for salvage therapy of aspergillosis as a parenteral antifungal drug.

In the present study, we sought to define the in vitro activity of CAS against clinical isolates of another problematic fungus, C. immitis. Secondarily, we sought possible correlations of C. immitis susceptibilities in vitro with the response to treatment in an animal model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In vitro susceptibility testing.

Twenty-five clinical isolates of C. immitis were used in this study. All were obtained from the Fungus Testing Laboratory, Department of Pathology, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Isolates were identified as C. immitis by macroscopic and microscopic morphology examinations, and identities were confirmed by DNA probe. Each isolate was maintained as a suspension in water at room temperature until testing was performed.

Each isolate of C. immitis was grown for 10 days at 35°C on potato flake agar slants prepared in-house (16). Isolates were evaluated by using National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards broth macrodilution proposed standard reference method M38-P for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of conidium-forming filamentous fungi (15). Briefly, the mycelium was overlaid with sterile distilled water and suspensions were made by gently scraping the colonies with wooden applicators. Heavy fragments were allowed to settle, and the upper, homogeneous supernatant was transferred to sterile tubes. The conidial-small mycelial fragment suspensions were vortexed and adjusted to the 95% transmittance at 530 nm setting with a spectrophotometer (Spectronic 21; Milton Roy Company). In a prior study, we found that the organism concentration at 95% transmittance corresponds to 1 × 104 to 5 × 104 CFU/ml (G. González González, R. Tijerina, D. A. Sutton, and M. G. Rinaldi, Abstr. 99th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 1999, abstr. C-172, 1999). CAS and FLU were tested in RPMI 1640 medium with l-glutamine and morpholinepropanesulfonic acid buffer at a concentration of 165 mM (Angus, Niagara Falls, N.Y.). AMB was tested in Antibiotic Medium 3 (Difco, Detroit, Mich.). CAS, FLU, and AMB were dissolved in sterile distilled water. The final drug concentrations were as follows: CAS (Merck Research Laboratories, Rahway, N.J.), 0.125 to 64 μg/ml; FLU (Pfizer Central Research, Groton, Conn.), 0.125 to 64 μg/ml; AMB (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, N.J.), 0.03 to 16 μg/ml.

Previously prepared frozen drug samples containing 0.1 ml of each drug were allowed to thaw and were inoculated with 0.9-ml volumes of the suspensions. A drug-free growth control tube was included for each isolate. Tubes were incubated at 35°C. The MIC and the minimum lethal concentration (MLC) were read at 48 h. The MIC was defined as the drug concentration in the first tube with a ≥80% reduction in turbidity compared to that of the drug-free control tube for CAS and FLU. For AMB, the MIC was the drug concentration in the first tube that was optically clear. The MLC was determined by streaking of 100 μl of broth from tubes with concentrations above the MIC and incubation at 35°C. The MLC was defined as the lowest concentration of an antifungal compound allowing the growth of five or fewer colonies. A Paecilomyces variotii control strain, UTHSC 90-459, was included for all testing. Two strains of C. immitis for which the CAS MICs were different were selected for determination of the minimum effective concentration (MEC). This evaluation consisted of microscopic inspection of the tubes with different concentrations of CAS. The lowest concentration of CAS needed to produce abnormal hyphal growth was recorded as the MEC.

Animals.

Outbred male ICR mice 4 to 6 weeks old (25 to 30 g) were purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley Inc. Ten mice were included in each treatment or control group for each survival and tissue burden study. They were housed in cages of five mice each. Mice were provided food and water ad libitum.

Test organisms.

Strains 98-449 (48-h MIC of 8 μg/ml and 48-h MEC of 0.125 μg/ml) and 98-571 (48-h MIC of 64 μg/ml and 48-h MEC of 0.125 μg/ml) were used for the animal studies. Four-week-old cultures with mycelial phase were maintained on potato dextrose agar plates. Arthroconidia were collected by using the magnetic stir bar technique. They were then filtered through glass wool, washed three times, suspended in sterile saline, and counted in a hemacytometer.

Infection model.

A previously described model of systemic coccidioidomycosis was utilized (6). Mice received an intravenous injection of 200 arthroconidia of C. immitis. Quantitative cultures by serial dilution were used to confirm the inoculum size. CAS was reconstituted with sterile distilled water and injected intraperitoneally in a 0.2-ml volume. CAS was given at 0.01, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 5.0, and 10.0 mg/kg per day on days 2 through 22 postinfection. The control group received sterile distilled water intraperitoneally. Deaths were recorded through 50 days postinfection. Moribund mice were terminated, and their deaths were recorded as occurring on the next day. At the end of the study, survivors were sacrificed by inhalation of metofane, followed by cervical dislocation. Spleens and livers were removed aseptically. The organs were homogenized in 2 ml of sterile saline, and the entire organs were plated onto potato dextrose agar and incubated at 35°C for a week.

For tissue burden studies, the treatment was the same but mice were sacrificed on day 24. Livers, spleens, and lungs were removed, weighed, and homogenized in 2 ml of sterile saline, and serial 10-fold dilutions were plated onto potato dextrose agar and incubated at 35°C for a week to determine the number of viable CFU in each organ.

Statistics.

For survival studies, the log rank and Wilcoxon tests were used. The P values for determining significance varied because of correction for multiple comparisons. For tissue burden studies, Dunnett's one-tailed t test or the rank sum test (Wilcoxon scores) was used. A P value of ≤0.05 determined the significance of differences compared only with controls.

RESULTS

Antifungal susceptibility.

The MIC and MLC ranges, geometric mean MICs and MLCs, and MICs and MLCs of CAS, FLU, and AMB necessary to inhibit and kill 50% and 90% of the C. immitis isolates tested are summarized in Table 1. MICs were reported at 48 h. The 48-h MIC ranges of CAS, FLU, and AMB for the P. variotii control strain were as follows: CAS, ≤0.125 to 0.5 μg/ml; FLU, 4 to 8 μg/ml; AMB, 0.5 to 1 μg/ml. The results for this organism were within the expected ranges.

TABLE 1.

In vitro activities of CAS, FLU, and AMB against 25 clinical strains of C. immitis

| Compound | 48-h MIC (μg/ml)

|

48-h MLC (μg/ml)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | GMa | 50%b | 90%c | Range | GMa | 50%d | 90%e | |

| CAS | 8–64 | 17.4 | 16 | 32 | 8–64 | 18.9 | 16 | 32 |

| FLU | 16–64 | 28.6 | 32 | 64 | NDf | ND | ND | ND |

| AMB | 0.25–0.5 | 0.34 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5–1 | 0.63 | 1 | 1 |

GM, geometric mean.

MIC at which 50% of the isolates were inhibited.

MIC at which 90% of the isolates were inhibited.

MLC at which 50% of the isolates were killed.

MLC at which 90% of the isolates were killed.

ND, not done.

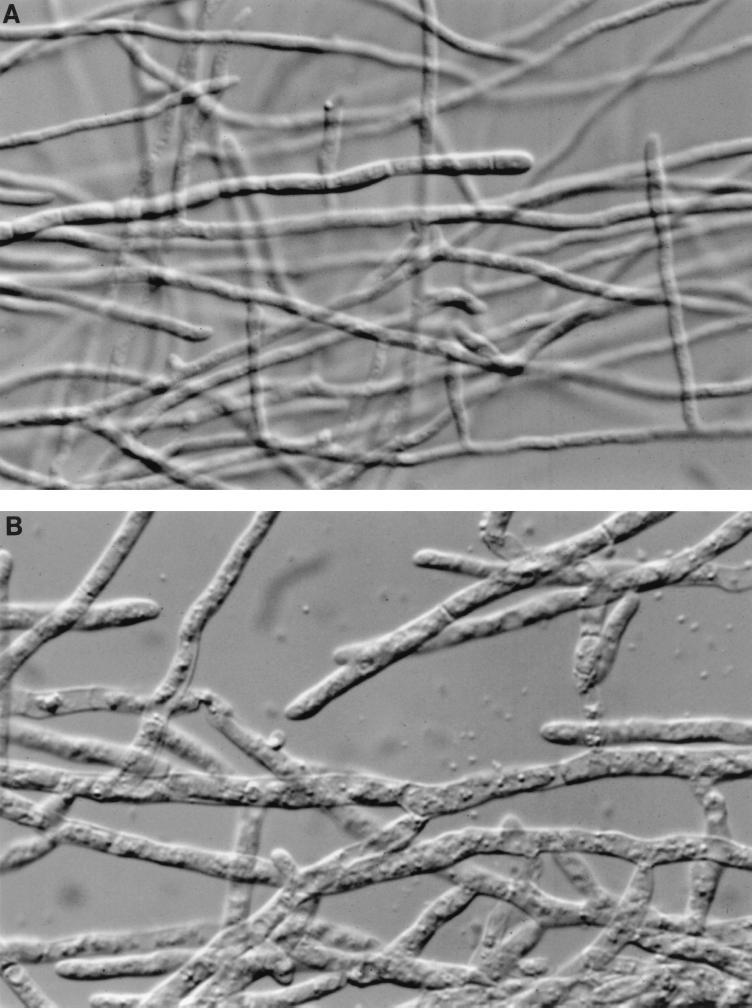

The result of the microscopic measurement of the 48-h MEC was 0.125 μg/ml for the pair of strains. We observed inflated and divided hyphae in the tubes with different concentrations of CAS (Fig. 1) in both strains. The results obtained when we used the MEC as the endpoint for in vitro susceptibility testing were dramatically different from those obtained when we employed the MIC defined as ≥80% inhibition of growth.

FIG. 1.

Photomicrographs (original magnification, ×400) after 48 h of incubation showing morphology changes in C. immitis strain 98-571. (A) RPMI 1640 medium control tube; (B) 1 μg of CAS per ml.

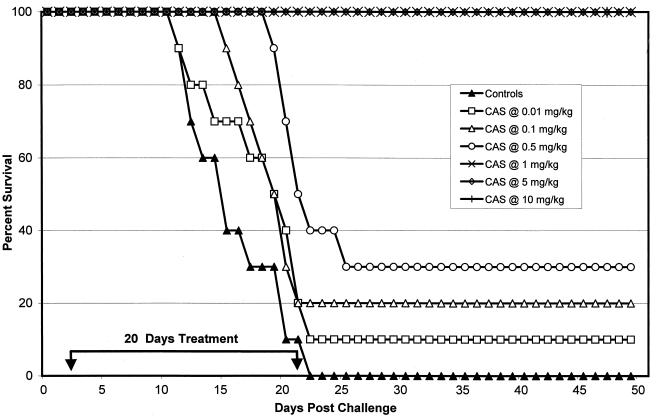

Survival study with strain 98-449.

The results of the survival study with strain 98-449 are displayed in Fig. 2. All control mice died between days 12 and 22. Every mouse treated with CAS at 1, 5, or 10 mg/kg survived to day 50. CAS doses of ≥0.5 mg/kg significantly prolonged survival (P ≤ 0.0085).

FIG. 2.

Survival study after intravenous infection with 200 arthroconidia of C. immitis strain 98-449 (MIC, 8 μg/ml). Therapy was given on days 2 to 22 after infection. The control group received sterile distilled water. There were 10 animals per group. Survivors were sacrificed on day 50.

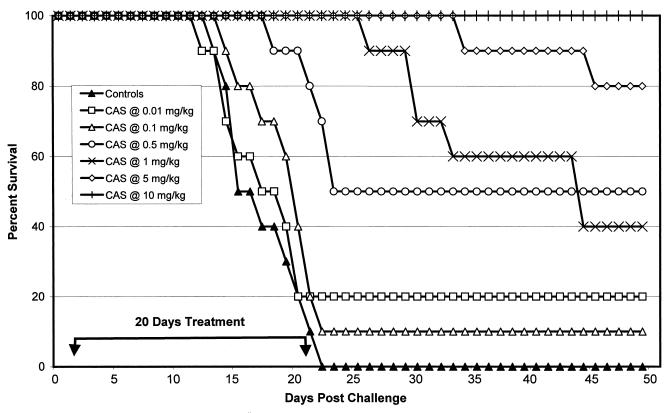

Survival study with strain 98-571.

Figure 3 shows that all of the control mice died between days 14 and 22. All mice treated with CAS at 10 mg/kg survived to day 50. Sixty and twenty percent of the mice treated with CAS at 1 and 5 mg/kg died between days 27 and 45 and days 35 and 45, respectively. CAS was slightly less effective in survival studies with strain 98-571 than with strain 98-449 at 1 mg/kg. However, significant prolongation of survival was noted at CAS doses of ≥0.5 mg/kg (P ≤ 0.0085).

FIG. 3.

Survival study after intravenous infection with 200 arthroconidia of C. immitis strain 98-571 (MIC, 64 μg/ml). Therapy was given on days 2 to 22. The control group received sterile distilled water. There were 10 animals per group. Survivors were sacrificed on day 50.

Tissue burden with strain 98-449.

The tissue fungal burden of mice was determined when they died or on day 24 postchallenge for those who survived. Treatment of mice with CAS at ≤0.1 mg/kg daily did not reduce the fungal burden, and there was no significant difference from the control value (P ≤ 0.05) (Table 2). CAS at ≥0.5 mg/kg significantly reduced spleen, liver, and lung fungal counts in a clearly dose-dependent manner.

TABLE 2.

Fungal burdens in spleens, livers, and lungs of mice infected with 200 arthroconidia of C. immitis strains 98-449a and 98-571b

| Amt of CAS (mg/kg) administered | Mean log10 no. of CFU/organ

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain 98-449

|

Strain 98-571

|

|||||

| Spleen | Liver | Lung | Spleen | Liver | Lung | |

| None (control) | 6.979 | 6.886 | 7.106 | 6.974 | 7.123 | 7.114 |

| 0.01 | 6.661 | 6.787 | 6.985 | 6.885 | 7.122 | 7.043 |

| 0.1 | 6.489 | 6.491 | 6.553 | 6.576c | 6.527c | 6.463c |

| 0.5 | 5.385a | 5.352c | 5.440c | 5.419c | 5.480c | 5.546c |

| 1 | 4.579c | 4.532c | 4.565c | 4.660c | 4.549c | 4.459c |

| 5 | 4.079c | 4.128c | 4.024c | 4.007c | 3.964c | 4.033c |

| 10 | 2.450c | 3.070c | 2.980c | 2.977c | 2.906c | 3.071c |

MIC, 8 μg/ml.

MIC, 64 μg/ml.

P ≤ 0.05 in comparison with control group.

Tissue burden with strain 98-571.

Treatment of mice with CAS at 0.01 mg/kg daily was ineffective in reducing the fungal burden, and there was no significant difference from the control value (P ≤ 0.05) (Table 2). CAS at ≥0.1 mg/kg was active in reducing the spleen, lung, and liver fungal burdens to levels lower than those of the controls, again in a dose-dependent manner.

DISCUSSION

At present, therapy of coccidioidomycosis is restricted to polyenes and azoles. AMB therapy is associated with frequent relapses and both acute and chronic toxicity. Renal insufficiency may be severe enough to lead to either early dose reduction or discontinuation of the drug. Treatment with itraconazole or FLU is also associated with frequent posttreatment relapses (5, 8, 18).

Given this poor record, a search for new antifungal drugs is justified. The glucan, chitin, and mannoproteins of fungal cell walls offer novel therapeutic opportunities for new drugs. The pioneer echinocandin was cilofungin, which has a narrow in vitro spectrum that is practically confined to Candida spp. (11, 12). In a model of systemic coccidioidomycosis, cilofungin did not prolong survival or reduce tissue fungal counts (6). This drug reached phase II clinical trials but was abandoned because of the occurrence of metabolic acidosis associated with the intravenous vehicle polyethylene glycol (unpublished data [Eli Lilly Co.]). However, new analogues of the echinocandins have been advanced into clinical trials. CAS, LY303366 (anidulacandin), and FK463 (micafungin) are in this group and appear promising for the treatment of systemic fungal infections.

The results of this study demonstrated poor in vitro antifungal activity against C. immitis, with 48-h MICs ranging from 8 to 64 μg/ml. Nevertheless, CAS was highly efficacious in the treatment of experimental coccidioidomycosis, despite MICs that differed between the strains. MIC endpoints were determined according to the conventional criteria outlined in NCCLS document M38-P. The NCCLS has not evaluated the echinocandins. Therefore, use of the same method to determine an endpoint may not be valid. In order to develop a clinically useful antifungal susceptibility method, perhaps entirely new criteria should be established for this class of compounds.

Studies of Aspergillus spp. have shown that endpoint readings with pneumocandins have been modified to obtain correlation with other parameters of antifungal activity. Kurtz et al. (13) used an endpoint MIC definition of complete absence of growth in ordinary broth microdilution to assess in vitro antifungal activities of pneumocandins A0 and B0. They found those compounds to be active in vitro against Candida spp. and inactive against Aspergillus spp. However, when they determined the MIC by microscopic examination of microdilution wells of Aspergillus spp., their observations showed that in the presence of drugs, the hyphae were extremely divided tips with inflated germ tubes. Macroscopically, these changes corresponded to production of very condensed clumps in dilution wells. They proposed the use of the MEC as the new endpoint for determination of susceptibility to lipopeptides.

For the two isolates of C. immitis we used in animal studies, there were discrepancies between the MIC and MEC evaluations. For these isolates, we found very different MICs but the same MEC of 0.125 μg/ml, which we considered an indication of sensitivity. The MEC results established that CAS is active in vitro against both isolates of C. immitis. This MEC could explain the similar results of survival and tissue burden studies done with both strains.

Visualization of the MEC is slightly more onerous because it demands microscopic inspection, but this inspection could be easily eliminated because the microscopic changes observed in the hyphae are analogous to the alterations seen on macroscopic assessment of the dilution tubes.

CAS is an antifungal compound that challenges the present methodology used for in vitro testing. Endpoint criteria for antifungal susceptibility testing with lipopeptide agents seem to occupy an important position among the numerous variables that may influence the results of in vitro tests. Reading of the MEC seems to hold great promise for the determination of in vitro susceptibility to this kind of compound. However, more studies are necessary to generalize this determination as a definitive endpoint.

One of the goals of this study was to permit comparison of the MICs of CAS for C. immitis in vitro with different doses of CAS against experimental systemic coccidioidomycosis. For this, we used six doses of CAS. CAS-treated mice survived longer than controls when subjected to the 1-, 5-, and 10-mg/kg treatment regimens. CAS was slightly less effective in survival studies with 98-571 than with 98-449 at 1 mg/kg. CAS at 0.5, 1, 5, and 10 mg/kg reduced the burdens of both strains of C. immitis in all of the organs examined to levels lower than those of the controls. When tissue burden results were compared between strains, CAS showed no statistically significant difference in efficacy in the organs of mice infected with strains 98-449 and 98-571.

In this study, different in vitro CAS activities were detected, depending on the endpoints applied. A limited association was displayed between in vitro testing with the MIC as the endpoint and antifungal treatment in this animal model. A better in vitro-in vivo correlation was noted when we used the MEC as the endpoint in antifungal susceptibility testing.

CAS may have a role in the treatment of coccidioidomycosis and should be evaluated in more seriously ill patients.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abruzzo G K, Flattery A M, Gill C J, Kong L, Smith J G, Pikounis V B, Balkovec J M, Bouffard A F, Dropinski J F, Rosen H, Kropp H, Bartizal K. Evaluation of the echinocandin antifungal MK-0991 (L-743,872): efficacies in mouse models of disseminated aspergillosis, candidiasis, and cryptococcosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2333–2338. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Current W L, Tang J, Boylan C, Watson P, Zeckner D, Turner W, Rodriguez M, Dixon C, Ma D, Radding J A. Glucan biosynthesis as a target for antifungals: the echinocandin class of antifungal agents. In: Dixon G K, Copping L G, Hollomon D W, editors. Antifungal agents. 1st ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Bios Scientific Publishers; 1995. pp. 143–157. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Del Poeta M, Schell W A, Perfect J R. In vitro antifungal activity of pneumocandin L-743,872 against a variety of clinically important molds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1835–1836. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.8.1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Lucca A J, Walsh T J. Antifungal peptides: novel therapeutic compounds against emerging pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1–11. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galgiani J N, Stevens D A, Graybill J R, Dismukes W E, Cloud G A The NIAID Mycoses Study Group. Ketoconazole therapy of progressive coccidioidomycosis. Comparisons of 400- and 800-mg doses and observations at higher doses. Am J Med. 1988;84:603–610. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galgiani J N, Sun S H, Clemons K V, Stevens D A. Activity of cilofungin against Coccidioides immitis: differential in vitro effects on mycelia and spherules correlated with in vivo studies. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:944–948. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.4.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallis H A, Drew R H, Pickard W W. Amphotericin B: 30 years of clinical experience. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:308–329. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.2.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graybill J R, Stevens D A, Galgiani J N, Dismukes W E, Cloud G A The NIAID Mycoses Study Group. Itraconazole treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Am J Med. 1990;89:282–290. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90339-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graybill J R, Najvar L K, Luther M F, Fothergill A W. Treatment of murine disseminated candidiasis with L-743,872. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1775–1777. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.8.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graybill J R, Najvar L K, Montalbo E M, Barchiesi F J, Luther M F, Rinaldi M G. Treatment of histoplasmosis with MK-991 (L-743,872) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:151–153. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.1.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall G S, Myles C, Pratt K J, Washington J A. Cilofungin ( LY121019), an antifungal agent with specific activity against Candida albicans and Candida tropicalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1331–1335. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.9.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanson L H, Stevens D A. Evaluation of cilofungin, a lipopeptide antifungal agent, in vitro against fungi isolated from clinical specimens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1391–1392. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.8.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurtz M B, Heath I B, Marrinan J, Dreikron S, Onishi J, Douglas C. Morphological effects of lipopeptides against Aspergillus fumigatus correlate with activities against (1,3)-β-d-glucan synthase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1480–1489. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.7.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurtz M B, Douglas C M. Lipopeptide inhibitors of fungal glucan synthase. J Med Vet Mycol. 1997;35:79–86. doi: 10.1080/02681219780000961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of conidium-forming filamentous fungi. Proposed standard. NCCLS document M38-P. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rinaldi M G. Use of potato flakes agar in clinical mycology. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15:1159–1160. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.6.1159-1160.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevens D A. Coccidioidomycosis. N Engl J Med. 1995;32:1077–1082. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504203321607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tucker R M, Galgiani J N, Denning D W, Hanson L H, Graybill J R, Sharkey K, Eckman M R, Salemi C, Libke R, Klein R A, Stevens D, A. Treatment of coccidioidal meningitis with fluconazole. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12(Suppl. 3):S380–S389. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.supplement_3.s380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]