Abstract

Ertapenem (MK-0826, L-749,345) is a 1-β-methyl carbapenem with a long serum half-life. Its in vitro activity was determined by broth microdilution against 3,478 bacteria from 12 centers in Europe and Australia, with imipenem, cefepime, ceftriaxone, and piperacillin-tazobactam used as comparators. Ertapenem was the most active agent tested against members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, with MICs at which 90% of isolates are inhibited (MIC90s) of ≤1 μg/ml for all species. Ertapenem also was more active than imipenem against fastidious gram-negative bacteria and Moraxella spp.; on the other hand, ertapenem was slightly less active than imipenem against streptococci, methicillin-susceptible staphylococci, and anaerobes, but its MIC90s for these groups remained ≤0.5 μg/ml. Acinetobacter spp. and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were also much less susceptible to ertapenem than imipenem, and most Enterococcus faecalis strains were resistant. Ertapenem resistance, based on a provisional NCCLS MIC breakpoint of ≥16 μg/ml, was seen in only 3 of 1,611 strains of the family Enterobacteriaceae tested, all of them Enterobacter aerogenes. Resistance was also seen in 2 of 135 anaerobes, comprising 1 Bacteroides fragilis strain and 1 Clostridium difficile strain. Ertapenem breakpoints for streptococci have not been established, but an unofficial susceptibility breakpoint of ≤2 μg/ml was adopted for clinical trials to generate corresponding clinical response data for isolates for which MICs were as high as 2 μg/ml. Of 234 Streptococcus pneumoniae strains tested, 2 required ertapenem MICs of 2 μg/ml and one required an MIC of 4 μg/ml, among 67 non-Streptococcus pyogenes, non-Streptococcus pneumoniae streptococci, single isolates required ertapenem MICs of 2 and 16 μg/ml. These streptococci also had diminished susceptibilities to other β-lactams, including imipenem as well as ertapenem. The Etest and disk diffusion gave susceptibility test results in good agreement with those of the broth microdilution method for ertapenem.

The carbapenem antibiotics imipenem and meropenem have the broadest antibacterial spectra of all the β-lactams now available. Consistent resistance is seen only in cell wall-deficient organisms, slowly growing mycobacteria, Enterococcus faecium, methicillin-resistant staphylococci, and a few infrequent nonfermenters, notably Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and some flavobacteria. The carbapenems also are more stable than any available cephalosporin or penicillin to the AmpC and extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) (6, 11, 12). These advantages make carbapenems an attractive class for further pharmaceutical development (6), especially since strains that have ESBLs and that hyperproduce AmpC β-lactamases continue to accumulate in hospitals (11, 12, 18) and are beginning to be seen in nursing home patients (2, 18), perhaps selected by community use of oral oxyimino-aminothiazolyl cephalosporins.

Ertapenem (MK-0826, L-749,345) is a novel carbapenem reported to have activity similar to that of meropenem against gram-positive bacteria, members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, and fastidious gram-negative bacteria but to be less active against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp. (7, 10). Like meropenem, but unlike imipenem, ertapenem has a 1-β-methyl substituent and so does not require protection with an inhibitor of human renal dihydropeptidase I. Ertapenem's most distinguishing feature among carbapenems is a serum half-life of 4 to 4.5 h, which should allow once-daily administration, as with ceftriaxone (8). By contrast, imipenem and meropenem must be administered three or four times daily.

To assess its in vitro activity, ertapenem was tested against panels of 10 to 20 recent clinical isolates of important bacterial pathogens collected at each of 12 centers in Europe and Australia. The comparator drugs were piperacillin-tazobactam and cefepime, chosen as the broadest-spectrum penicillin and cephalosporin, respectively, together with imipenem as a reference carbapenem and ceftriaxone as the closest match to ertapenem in its pharmacokinetics and, potentially, patterns of clinical usage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Centers enrolled and isolates tested.

Single centers were enrolled in Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, The Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom, together with two centers in Australia. Each center was asked to test unselected clinical isolates collected in 1999 and 2000 as follows: Enterococcus faecalis (n = 10), methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (n = 20), coagulase-negative staphylococci (n = 20), Streptococcus pyogenes (n = 10), Streptococcus pneumoniae (n = 20), Streptococcus spp. (n = 10), Citrobacter spp. (n = 10), Enterobacter aerogenes (n = 10), Enterobacter cloacae (n = 10), Escherichia coli (n = 20), Klebsiella oxytoca (n = 10), Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 20), Morganella morganii (n = 10), Proteus mirabilis (n = 20), Proteus vulgaris (n = 10), Providencia rettgeri (n = 10), Providencia stuartii (n = 10), Salmonella spp. (n = 10), Serratia spp. (n = 10), Shigella spp. (n = 10), Aeromonas spp. (n = 10), Acinetobacter spp. (n = 10), P. aeruginosa (n = 10), Haemophilus influenzae (n = 20), Haemophilus spp. (n = 10), Moraxella spp. (n = 10), Neisseria meningitidis (n = 10), and anaerobes (n = 20). Determination of the species of the isolates was by the laboratories' routine methods. Multiple isolates from a single patient were excluded. None of the centers enrolled was involved in clinical trials with ertapenem.

Susceptibility testing.

Susceptibility testing with ertapenem, imipenem, cefepime, ceftriaxone, and piperacillin-tazobactam was primarily undertaken by broth microdilution, performed with preprepared antibiotic panels (PML Microbiologicals, Wilsonville, Oreg.). The basal media used were those recommended by the NCCLS, with cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth used for nonfastidious organisms, cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with lysed horse blood used for streptococci, Haemophilus test medium used for fastidious gram-negative species, and Wilkins-Chalgren broth used for anaerobes (14–16). The panels were distributed frozen to the participating centers by express courier and were then stored at −60°C or below. Prior to use, they were brought to room temperature and inoculated with bacterial suspensions prepared to NCCLS recommendations, giving ca. 5 × 105 CFU/ml. MICs for nonfastidious organisms were read as the concentrations in the first wells that showed no visible growth or haze after incubation at 35°C for 16 to 20 h; those for fastidious organisms and anaerobes were read similarly, but after 20 to 24 h of incubation.

The MICs of ertapenem and imipenem for the isolates at most centers were also determined by the Etest with the media, inocula, conditions, and protocols recommended by the supplier (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden). Disk diffusion tests were also performed by the NCCLS (14) methodology with ertapenem and imipenem (10-μg disks; Becton-Dickinson, Sparks, Md.). The media used were from the participating laboratories' stocks, meaning that the batches and suppliers varied.

Quality control.

All the centers were asked to test control strains in parallel with the isolates and to confirm that, for the established comparator antibiotics, their results fell within the ranges specified by NCCLS (14–16). The strains comprised Bacteroides fragilis ATCC 25285, E. faecalis ATCC 29212, E. coli ATCC 25922, H. influenzae ATCC 49427 and ATCC 49766, S. aureus ATCC 29213 and ATCC 25923, and S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619.

Statistical analyses.

Data were entered into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets and collated centrally. To test agreement between the two methods (broth microdilution and Etest) used to generate MICs, a weighted kappa statistic (κ) was calculated. The data obtained by disk diffusion testing were compared with the MIC data by error-bounded analysis.

RESULTS

Comparative activity of ertapenem.

The MIC results obtained with the preprepared dilution trays at the 12 centers are presented in Table 1. The breakpoints used to estimate rates of resistance to established antibiotics among nonfastidious species are those advocated by the NCCLS (15, 16). Provisional NCCLS MIC breakpoints for ertapenem against nonfastidious bacterial species are as follows: susceptible, ≤4 μg/ml; intermediate, 8 μg/ml; and resistant, ≥16 μg/ml (NCCLS Summary Minutes, Meeting of Subcommittee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, Reston, Va., 7 to 9 June 1998, p. 15 to 16) and are identical to those for imipenem. No NCCLS breakpoints are yet established for ertapenem against streptococci or haemophili, but an unofficial susceptibility breakpoint of ≤2 μg/ml was adopted for streptococci in clinical trials so as to generate corresponding clinical data for isolates for which MICs are as high as 2 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Summary MIC data for ertapenem and comparator drugs

| Organisms (no. tested) and antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml) in broth

|

% Resistanta | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | |||

| Citrobacter spp. (112) | |||||

| Ertapenem | 0.006–0.5 | 0.008 | 0.06 | 0 | |

| Imipenem | 0.06–4 | 0.5 | 2 | 0 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–128 | 0.12 | 32 | 9 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–128 | 0.03 | 1 | 4 | |

| Pip/tazob | 0.12–256 | 4 | 64 | 7 | |

| E. aerogenes (113) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–≥16 | 0.06 | 1 | 3 | |

| Imipenem | 0.12–≥16 | 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–128 | 0.5 | 128 | 30 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–64 | 0.12 | 16 | 10 | |

| Pip/tazo | 2–256 | 8 | 256 | 31 | |

| E. cloacae (118) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–4 | 0.06 | 1 | 0 | |

| Imipenem | 0.06–≥8 | 0.5 | 2 | 0 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–128 | 0.25 | 128 | 25 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–64 | 0.06 | 16 | 9 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.5–256 | 4 | 256 | 24 | |

| E. coli (248) | |||||

| Ertapenem | 0.006–1 | 0.008 | 0.03 | 0 | |

| Imipenem | 0.012–2 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–128 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 2 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–64 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.4 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.03–256 | 2 | 128 | 14 | |

| K. oxytoca (110) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–0.12 | 0.008 | 0.03 | 0 | |

| Imipenem | 0.12–4 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–128 | 0.06 | 2 | 8 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–64 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 1 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.5–256 | 2 | 64 | 10 | |

| K. pneumoniae (243) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–2 | 0.008 | 0.06 | 0 | |

| Imipenem | 0.06–≥16 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–128 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 5 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–64 | 0.03 | 1 | 1.6 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.03–256 | 4 | 256 | 14 | |

| M. morganii (119) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–4 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0 | |

| Imipenem | 0.25–16 | 4 | 8 | 8 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–64 | 0.12 | 8 | 1 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–16 | 0.03 | 2 | 0 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.03–256 | 0.5 | 32 | 7 | |

| P. mirabilis (115) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–1 | 0.015 | 0.06 | 0 | |

| Imipenem | 0.25–≥16 | 1 | 8 | 6 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–128 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 7 | |

| Cefepime | 0.006–64 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 7 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.03–256 | 0.25 | 1 | 7 | |

| P. vulgaris (76) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–1 | 0.016 | 0.25 | 0 | |

| Imipenem | 0.25–≥16 | 4 | 8 | 3 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–128 | 16 | 128 | 35 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–64 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 4 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.03–16 | 0.25 | 2 | 0 | |

| Providencia spp. (71) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–2 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0 | |

| Imipenem | 0.25–≥16 | 2 | 8 | 2 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–128 | 0.05 | 8 | 3 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–32 | 0.03 | 1 | 1 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.008–256 | 2 | 16 | 4 | |

| Salmonella spp. (111) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–0.25 | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0 | |

| Imipenem | 0.015–2 | 0.25 | 1 | 0 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–4 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–8 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.25–256 | 2 | 16 | 2 | |

| Serratia spp. (115) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–1 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0 | |

| Imipenem | 0.015–8 | 1 | 4 | 0 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–64 | 0.25 | 4 | 4 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–8 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 0 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.03–256 | 2 | 32 | 7 | |

| Shigella spp. (59) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–0.5 | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0 | |

| Imipenem | 0.12–2 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–128 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 2 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–2 | 0.03 | 1 | 0 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.03–128 | 2 | 64 | 5 | |

| Aeromonas spp. (72) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–≥16 | 0.12 | 4 | 8 | |

| Imipenem | 0.12–≥16 | 2 | 16 | 19 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–1 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 0 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–0.25 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.12–256 | 8 | 256 | 24 | |

| Acinetobacter spp. (109) | |||||

| Ertapenem | 0.015–≥16 | 4 | 16 | 30 | |

| Imipenem | 0.03–≥16 | 0.5 | 16 | 18 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.06–128 | 16 | 128 | 35 | |

| Cefepime | 0.12–64 | 4 | 64 | 23 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.03–256 | 16 | 256 | 31 | |

| P. aeruginosa (130) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–≥16 | 4 | 16 | 33 | |

| Imipenem | 0.06–≥16 | 4 | 16 | 17 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.06–128 | 64 | 128 | 53 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–64 | 4 | 64 | 17 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.25–256 | 8 | 256 | 22 | |

| H. influenzae (242) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–1 | 0.03 | 0.12 | NDc | |

| Imipenem | <0.008–≥16 | 1 | 2 | ND | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.06–8 | 0.06 | 0.06 | ND | |

| Cefepime | 0.012–2 | 0.06 | 0.125 | ND | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.03–2 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 1 | |

| Haemophilus spp. (87) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–0.5 | 0.03 | 0.25 | ND | |

| Imipenem | <0.008–≥2 | 0.5 | 2 | ND | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.06–0.5 | 0.06 | 0.25 | ND | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–8 | 0.06 | 1 | ND | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.06–4 | 0.12 | 1 | 10 | |

| Moraxella spp. (76) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–0.5 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0 | |

| Imipenem | <0.008–8 | 0.015 | 0.25 | 0 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–1 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–4 | 0.25 | 1 | 0 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.03–0.125 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0 | |

| N. meningitidis (26) | |||||

| Ertapenem | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | ND | |

| Imipenem | <0.008–0.125 | 0.008 | 0.12 | ND | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | ND | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | ND | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.03–0.12 | 0.06 | 0.12 | ND | |

| Clostridium spp. (25) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–16 | 0.12 | 2 | 4 | |

| Imipenem | <0.008–2 | 0.12 | 1 | 0 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.06–≥64 | 0.5 | 16 | 4 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–≥64 | 0.5 | ≥64 | ND | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.09–4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| B. fragilis group (81) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–≥16 | 0.25 | 2 | 1 | |

| Imipenem | <0.008–16 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.5–≥64 | 32 | ≥64 | 30 | |

| Cefepime | 0.5–≥64 | 32 | ≥64 | ND | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.5–32 | 1 | 4 | 0 | |

| Prevotella spp. (6) | |||||

| Ertapenem | 0.008–4 | 0 | |||

| Imipenem | 0.008–1 | 0 | |||

| Ceftriaxone | 0.05–≥64 | 17 | |||

| Cefepime | 0.5–64 | ND | |||

| Pip/tazo | 0.5–8 | 0 | |||

| Anaerobic cocci (8) | |||||

| Ertapenem | 0.008–0.03 | 0 | |||

| Imipenem | 0.008–0.03 | 0 | |||

| Ceftriaxone | 0.5–8 | 0 | |||

| Cefepime | 0.5–8 | ND | |||

| Pip/tazo | 0.5–4 | 0 | |||

| Propionibacterium spp. (11) | |||||

| Ertapenem | 0.008–0.25 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0 | |

| Imipenem | 0.008–0.03 | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | |

| Cefepime | 0.5–4 | 1 | 4 | ND | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.5–1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Veillonella spp. (2) | |||||

| Ertapenem | 0.03–2 | 0 | |||

| Imipenem | 0.25–0.5 | 0 | |||

| Ceftriaxone | 2–4 | 0 | |||

| Cefepime | 4–8 | ND | |||

| Pip/tazo | 2–8 | 0 | |||

| Fusobacterium sp. (1) | |||||

| Ertapenem | 0.008 | 0 | |||

| Imipenem | 0.015 | 0 | |||

| Ceftriaxone | 1 | 0 | |||

| Ceftriaxone | 0.5 | 0 | |||

| Cefepime | 0.5 | ND | |||

| Pip/tazo | 0.5 | 0 | |||

| E. faecalis (120) | |||||

| Ertapenem | 1–32 | 16 | 16 | 55 | |

| Imipenem | 0.25–≥16 | 2 | 4 | 5 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.25–≥128 | 128 | 128 | NAd | |

| Cefepime | 0.5–64 | 32 | 64 | NA | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.06–64 | 4 | 8 | NA | |

| S. aureus, methicillin susceptible (241) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–≥16 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.4 | |

| Imipenem | <0.008–≥16 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.5 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–128 | 2 | 4 | 0.4 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–64 | 2 | 4 | 0.4 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.03–128 | 1 | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Staphylococcus spp., coagulase negative (237) | |||||

| Ertapenem | 0.03–32 | 0.25 | 16 | 11 | |

| Imipenem | <0.008–32 | 0.03 | 2 | 5 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.12–128 | 2 | 32 | 8 | |

| Cefepime | 0.06–128 | 1 | 16 | 7 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.03–256 | 0.5 | 8 | 9 | |

| S. pneumoniae (234) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–4 | 0.008 | 0.5 | ND | |

| Imipenem | <0.008–2 | 0.008 | 0.25 | 0.9 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–4 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 3 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–4 | 0.03 | 1 | 5 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.03–8 | 0.12 | 2 | NRe | |

| S. pyogenes (92) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–0.25 | 0.008 | 0.06 | ND | |

| Imipenem | <0.008–0.25 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–1 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–0.5 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.06–4 | 0.06 | 0.5 | NR | |

| Streptococcus spp. (67) | |||||

| Ertapenem | <0.008–≥16 | 0.03 | 0.5 | ND | |

| Imipenem | <0.008–8 | 0.015 | 0.125 | 3 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.03–8 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 3 | |

| Cefepime | 0.03–4 | 0.06 | 1 | 6 | |

| Pip/tazo | 0.03–8 | 0.12 | 2 | NR | |

| Cefepime | 2 | ND | |||

| Pip/tazo | 2 | 0 | |||

| Actinomyces sp. (1) | |||||

| Ertapenem | 0.008 | 0 | |||

| Imipenem | 0.008 | 0 | |||

Relative to NCCLS resistance breakpoints (14–16), which were as follows: for nonfastidious species, cefepime, ≥32 μg/ml; ceftriaxone ≥64 μg/ml; ertapenem, ≥16 μg/ml; imipenem, ≥16 μg/ml; and piperacillin-tazobactam, 128 μg/ml; and for streptococci, cefepime, ≥2 μg/ml; ceftriaxone, ≥2 μg/ml; and imipenem, 1 μg/ml.

Pip/tazo, piperacillin-tazobactam.

ND, not determined.

NA, not applicable.

NR, not recommended.

Not all the centers tested their full complement of isolates, but in total, results for 3,478 isolates were available for analysis. Imipenem results for the Enterobacteriaceae panels at two centers were excluded on the ground that high rates of resistance were apparent by broth microdilution but were not confirmed by the Etest or disk diffusion. These centers also recorded imipenem MICs of 8 μg/ml or more for E. coli ATCC 25922 with the microdilution panels, and it was concluded that the imipenem had deteriorated during transit or storage. Similar problems were not seen with the other panels at these centers, so data obtained with these were accepted.

Ertapenem was the most active agent tested against isolates of the family Enterobacteriaceae, with MICs at which 90% of isolates are inhibited (MIC90s) of 1 μg/ml or less for all species. Imipenem also had good activity against these organisms, with MIC90s of 1 to 4 μg/ml, except for Proteus, Morganella, and Providenica spp., for which MIC90s of 8 μg/ml were recorded. Three carbapenem-resistant (MIC, ≥16 μg/ml) isolates of the Enterobacteriaceae, all E. aerogenes, were found and are discussed below. Cefepime MIC90s were 1 to 4 μg/ml for most groups of the Enterobacteriaceae, with the drug achieving activity similar to those of the carbapenems, but Enterobacter spp. were more resistant, with MIC90s of 16 μg/ml. Ceftriaxone and piperacillin-tazobactam had low MIC50s for isolates of the Enterobacteriaceae, but MIC90s were raised for many species and groups, indicating inclusion of substantial minorities of resistant isolates.

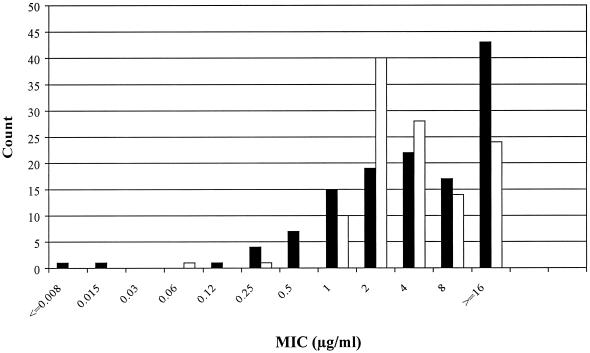

Ertapenem was much less active than imipenem against Acinetobacter spp. and P. aeruginosa. In the case of Acinetobacter spp., this differential was obvious from the MIC50s: 0.5 μg/ml for imipenem compared with 4 μg/ml for ertapenem. In the case of P. aeruginosa, the differential was not evident from the MIC50s and MIC90s, which were 4 and 16 μg/ml, respectively, for both carbapenems. Nevertheless a differential in antipseudomonal activity was evident from the MIC distributions (Fig. 1); moreover, 33% of the P. aeruginosa isolates required ertapenem MICs of ≥16 μg/ml, whereas only 17% required imipenem MICs of ≥16 μg/ml. Cefepime and piperacillin-tazobactam had low MIC50s (4 to 16 μg/ml) for P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp., but their MIC90s were high (64 to 256 μg/ml), indicating that substantial minorities of isolates had greater levels of resistance. Ceftriaxone had predictably poor activity against nonfermenters. Among nonfastidious gram-negative organisms, only Aeromonas spp. were more susceptible to ceftriaxone and cefepime than to either carbapenem.

FIG. 1.

MIC distributions of ertapenem (solid bars) and imipenem (open bars) for the 130 P. aeruginosa isolates tested, as determined by broth microdilution.

All five antibiotics had MIC90s of 2 μg/ml or less for Haemophilus, Neisseria, and Moraxella spp. Ertapenem was consistently the most active compound, with MIC50s and MIC90s slightly below those of the cephalosporins and 8- to 16-fold below those of imipenem. Ertapenem was slightly less active than imipenem against methicillin-susceptible staphylococci and streptococci, but its MIC90s for these groups of organisms were less than 1 μg/ml. A higher MIC90 was recorded for coagulase-negative staphylococci, in which the study population included methicillin-resistant strains, than for methicillin-susceptible S. aureus. The cephalosporins and piperacillin-tazobactam had activities similar to those of the carbapenems against streptococci or were slightly less active but were 4- to 32-fold less active against staphylococci. The MIC distributions of all the antibiotics were wide for all streptococci except S. pyogenes, and small minorities of isolates had resistance or greatly diminished susceptibility. Thus, the MICs of imipenem and ertapenem ranged up to 4 μg/ml for S. pneumoniae and to 16 μg/ml for a single Streptococcus sp. isolate (see below). Most E. faecalis isolates had low-level resistance to ertapenem; thus, MIC50s and MIC90s of 16 μg/ml were recorded for the species, whereas the MIC50 and MIC90 of imipenem were 2 and 4 μg/ml, respectively. Imipenem and ertapenem were both strongly active against anaerobes, with MIC90s of 2 μg/ml or less and with imipenem being the slightly more active compound. Piperacillin-tazobactam also had good activity against anaerobes, whereas both cephalosporins had poor activity against B. fragilis and some clostridia.

Ertapenem- and imipenem-resistant isolates.

Although ertapenem was strongly active against most isolates of the Enterobacteriaceae fastidious gram-negative bacteria, anaerobes, and gram-positive cocci, a few members of these groups had resistance or reduced susceptibility (Table 2). Among the 1,611 isolates in the family Enterobacteriaceae tested, 3 isolates, all E. aerogenes, were resistant to both ertapenem and imipenem, with MICs of ≥16 μg/ml found by broth microdilution test and confirmed (±1 dilution) by the Etest (Table 2). Of these three isolates, one was from Greece, one was from the United Kingdom, and one was from Belgium. No other isolate of the Enterobacteriaceae was confirmed to be resistant to either ertapenem or imipenem. Among the anaerobes, one B. fragilis isolate was resistant to ertapenem and to all the comparator drugs, and one C. difficile isolate was cross-resistant by the broth dilution test to ertapenem and the cephalosporins but not to imipenem or piperacillin-tazobactam. The results for streptococci for which ertapenem MICs were ≥2 μg/ml by the broth dilution tests are also included in Table 2, although no ertapenem breakpoint is yet established for these organisms. Two isolates of Streptococcus spp. (of 67 tested) required ertapenem MICs of 2 and 16 μg/ml, respectively, and 3 S. pneumoniae isolates (of 234 tested) required ertapenem MICs of 2 μg/ml (2 isolates) and 4 μg/ml (1 isolate). These five streptococci were resistant to the comparator antibiotics or had diminished susceptibility relative to the MIC50s, but ertapenem MICs of ≥2 μg/ml were confirmed by the Etest for only two of the five isolates.

TABLE 2.

MICs for ertapenem-resistant members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, anaerobes, and streptococci with substantially diminished ertapenem susceptibility

| Species | Source country | MIC (μg/ml) by broth microdilution a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ertapenem | Imipenem | Ceftriaxone | Cefepime | Pip/tazob | ||

| E. aerogenes | Belgium | 16 (32) | 16 (32) | 128 | 64 | 256 |

| E. aerogenes | England | 16 | 16 | 128 | 16 | 256 |

| E. aerogenes | Greece | 16 (32) | 16 (32) | 128 | 64 | 256 |

| Bacteroides spp. | Holland | >16 (32) | 16 (16) | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| C. difficile | Switzerland | 16 (6) | 1 (1.5) | 32 | >64 | 2 |

| S. pneumoniae | Germany | 4 (3) | 2 (1.5) | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| S. pneumoniae | Spain | 2 (0.25) | 0.25 (0.25) | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| S. pneumoniae | Spain | 2 (0.25) | 0.25 (0.19) | 0.5 | 1 | 4 |

| Streptococcus spp. | Belgium | 16 (32) | 2 (2) | 8 | 4 | 8 |

| Streptococcus spp. | Germany | 2 (0.75) | 8 (2) | 8 | 4 | 8 |

The value obtained by the Etest, where available, is given in parentheses.

Pip/tazo, piperacillin-tazobactam.

Agreement of MICs determined by the Etest and broth microdilution.

Ertapenem MICs were determined by the Etest as well as by broth microdilution for 2,674 isolates. For 2,162 (80.8%) of these organisms, the MICs were within 1 dilution of those obtained by broth microdilution (Table 3); for a further 323 (12.1%), the MICs found by the Etest diverged from those obtained by broth microdilution by 2 dilutions. The number of instances in which the Etest indicated an MIC more than 1 dilution above that indicated by broth microdilution (n = 259) almost exactly equaled those in which the Etest gave a value more than 1 dilution below that given by broth microdilution (n = 253). In the case of imipenem (data not shown), 2,478 isolates were tested by broth microdilution and the Etest. In 1,889 cases (76.2%), the MIC results by the two methods agreed within 1 dilution and, in a further 405 cases (16.3%), they agreed within 2 dilutions. Cases in which the Etest gave MICs more than 1 dilution above those given by broth microdilution (n = 337) outnumbered those in which the Etest gave a result more than 1 dilution below that given by broth microdilution (n = 252).

TABLE 3.

MICs of ertapenem for 2,674 isolates (all species) determined by the Etest compared with those determined by broth microdilution

| MIC (μg/ml) by Etest | No. of isolates for which the MIC (μg/ml) by broth microdilution is as follows:

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | |

| 0.008 | 565 | 87 | 60 | 13 | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| 0.015 | 162 | 135 | 77 | 29 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| 0.03 | 31 | 76 | 119 | 54 | 21 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| 0.06 | 10 | 26 | 76 | 83 | 42 | 11 | 4 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| 0.12 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 40 | 102 | 30 | 10 | 6 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 0.25 | 8 | 14 | 16 | 33 | 46 | 70 | 30 | 14 | 5 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 0.5 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 23 | 28 | 32 | 16 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 11 | 8 | 7 | 1 | |||||

| 2 | 1 | 3 | 16 | 24 | 17 | 5 | 4 | ||||||

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 13 | 17 | 16 | 13 | |||||

| 8 | 2 | 6 | 11 | 24 | 23 | 1 | |||||||

| 16 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 14 | 17 | |||||||

| 32 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 74 | 2 | |||||

The agreement between broth dilution and Etest across the range of MICs was assessed by calculation of a weighted kappa statistic (κ). Although a simple κ is designed for nominal classifications, the measure of weighted κ uses weights to account for the differences in ordered categories. Values of κ and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals bound for ertapenem were as follows: all bacteria, 0.60 (0.57 to 0.63); nonfastidious bacteria, 0.59 (0.57 to 0.61); streptococci, 0.68 (0.48 to 0.88); haemophili, 0.49 (0.39 to 0.60); and anaerobes 0.67 (0.43 to 0.91). The corresponding values for imipenem were as follows: all bacteria, 0.54 (0.51 to 0.57); nonfastidious bacteria, 0.48 (0.45 to 0.51); streptococci, 0.73 (0.60 to 0.85); haemophili, 0.30 (0.16 to 0.44); and anaerobes, 0.79 (0.60 to 0.97). The level of agreement between the Etest and broth microdilution was good for both ertapenem and imipenem, as indicated by confidence intervals that did not cover zero.

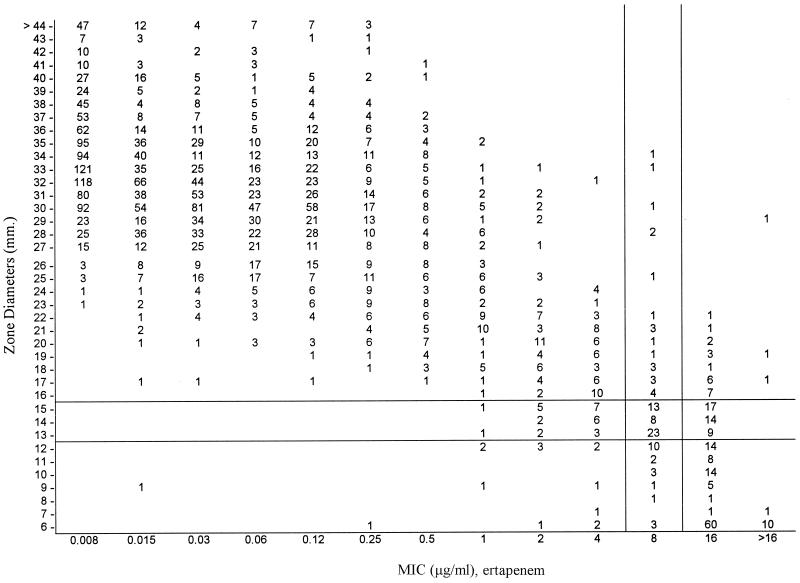

Agreement of broth microdilution and disk diffusion.

Diffusion tests with 10-μg disks of ertapenem and imipenem were performed for all the nonfastidious isolates, and the relationships between the inhibition zones and the MICs found by broth microdilution for ertapenem are shown in Fig. 2. The provisional zone diameter breakpoints proposed for ertapenem are as follows: susceptible, ≥16 mm; intermediate, 13 to 15 mm; and resistant, ≤12 mm (7). These have been approved by the NCCLS to guide therapy in phase II and III trials (NCCLS Summary Minutes Meeting of Subcommittee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, Reston, Va., 7 to 9 June 1998, p. 15–16). On this basis and on the basis of counting MICs of 8 mg/ml as intermediate, the proportions of very major errors (resistant isolates found to be susceptible in diffusion tests) were 0.77% for ertapenem and 1.5% for imipenem, and the proportions of major errors (susceptible isolates found to be resistant in diffusion tests) were 0.48% for ertapenem and 0.15% for imipenem. Proportions of minor errors (isolates found to be intermediate by one method but resistant or susceptible by the other) were 3.49% for ertapenem and 3.16% for imipenem.

FIG. 2.

Error-bounded analysis of MIC and zone distributions for ertapenem against nonfastidious bacteria. The MICs were determined by broth microdilution, and the inhibition zones were measured with 10-μg disks.

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the in vitro susceptibilities of a wide range of bacterial isolates collected in Europe and Australia to ertapenem and comparator drugs. Susceptibility was assessed against NCCLS breakpoints. Provisional interpretive criteria (7; NCCLS Summary Minutes, meeting of Subcommittee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, Reston, Va., 7 to 9 June 1998, p. 15–16) for ertapenem against nonfastidious species are as follows for dilution tests and diffusion tests, respectively: susceptible, ≤4 μg/ml and ≥16 mm; intermediate, 8 μg/ml and 13 to 15 mm; and resistant, ≥16 μg/ml and ≤12 mm. These values are based upon the recommendations presented in NCCLS document M23-A2 (17) and take into account (i) the MIC and zone distribution data, (ii) error-bounded and regression analysis of MICs versus inhibition zones for over 600 isolates, (iii) animal and human pharmacokinetic data (A. K. Majumdar, K. L. Birk, W. Neway, D. G. Musser, L. Tomasko, M. Hesney, R. Lins, R. Haesen, G. Mistry, S. Holland, P. Deutsch, and J. D. Rogers, Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 491, 2000; M. L. van Ogtrop, D. Andes, and W. A. Craig., Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F48, 1998), and (iv) clinical correlation with data from phase IIa clinical studies (Merck Research Laboratories, data on file). The choice of breakpoints partially reflects the fact that carbapenems require levels above the MICs for only 15 to 40% of the dosage interval for therapeutic efficacy, whereas cephalosporins and penicillins require levels above the MICs for at least 40% of the dosage intervals (4).

Ertapenem and imipenem were the most active antibiotics tested in this study, which examined 3,478 recent clinical isolates from Europe and Australia. Ertapenem had greater activity than imipenem against members of the family Enterobacteriaceae and Moraxella, Neisseria, and Haemophilus spp., with MIC50s and MIC90s 2- and 128-fold, respectively below those of the earlier carbapenem. This gain in activity over imipenem is similar to that seen for meropenem (9). Ertapenem had activity similar to that of imipenem against anaerobes, streptococci, and staphylococci or was slightly less active than imipenem. This differential seems unlikely to be consequential since the MICs of both compounds were considerably below the likely resistance breakpoints. Ertapenem was also less active than imipenem against P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp., and this differential, although small in biological terms, led to substantially higher rates of resistance to the newer carbapenem. The only gram-negative bacteria that were consistently more susceptible to the cephalosporins than to either ertapenem or imipenem were Aeromonas spp. These organisms frequently produce chromosomally determined zinc carbapenemases, which might be expected to hydrolyze ertapenem (20, 23). The patterns of activity for ertapenem found here against isolates from Europe and Australia resemble those reported for bacteria collected in the United States (7, 10).

Resistance mechanisms were not characterized, and several of the authors believe that several NCCLS breakpoints used in this analysis may underestimate the biological resistance caused by, e.g., ESBLs. The high rate of ceftriaxone resistance among isolates of the genus Enterobacter nevertheless implies the inclusion of many organisms that hyperproduced their AmpC β-lactamases. Similarly, the wide ranges of MICs of the cephalosporins for K. pneumoniae suggest that a few strains of this species had ESBLs, although this proportion cannot have been large in view of the low MIC90s (1 μg/ml) of cefepime and ceftriaxone. Ertapenem, like imipenem, retained activity against most organisms inferred to have such enzymes, suggesting stability to critical β-lactamases. This inference is supported by direct studies on producers of enzymes that have been characterized (D. M. Livermore et al., unpublished observations). Nevertheless, ertapenem-resistant isolates were found. Resistance in a single isolate of B. fragilis is unsurprising since a few members of this species produce the CcrA (CfiA) enzyme, a metallo-β-lactamase which hydrolyzes carbapenems (20, 21, 24). Likewise, it was unsurprising to find reduced susceptibility to ertapenem in streptococci with resistance to other β-lactams. β-Lactam resistance in members of this genus entails changes to penicillin-binding proteins, and these typically affect the activities of all β-lactams to some degree (22). Results from clinical trials with ertapenem for the treatment of pneumococcal infections showed favorable clinical and bacteriological responses even for organisms for which MICs were 2 to 4 μg/ml (Merck Research Laboratories, data on file), albeit on the basis of the results for only a small number of patients.

More surprising was the finding of three E. aerogenes isolates that were resistant to ertapenem and imipenem. Resistance to carbapenems remains extremely rare in members of the family Enterobacteriaceae (11, 12), and although reports of acquired carbapenemases in gram-negative bacilli are now accumulating, these mostly concern Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter spp. (13). Nevertheless, a very broad spectrum resistance to β-lactams, compromising carbapenems as well as other β-lactams, arises if hyperproduction of an AmpC β-lactamase or an ESBL is accompanied by porin loss in E. aerogenes (1, 3, 19). These combinations of mechanisms have been seen in representatives of major epidemic strains of E. aerogenes, notably in Belgium and France (1, 3, 5). It may be that such organisms were included in the present collection, but it remains possible that the present isolates had other resistance mechanisms, such as metallo-β-lactamases.

Broth microdilution was the reference method of susceptibility testing, but the Etest and disk diffusion assays were also evaluated and found to give results in good agreement with those of the reference method. With disk diffusion tests and zone criteria (7) of ≥16 mm for susceptible; 13 to 15 mm for intermediate, and ≤12 mm for resistant, the proportions of very major, major, and minor errors were small, were similar for both ertapenem and imipenem, and were well within acceptable NCCLS guidelines (17).

In summary, the data presented here reveal that ertapenem has potent broad-spectrum activity against most common bacterial pathogens except nonfermenters, Aeromonas spp., and enterococci. The spectrum of microbiological activity of ertapenem is slightly more focused compared to those of imipenem and meropenem, with very little or significantly reduced in vitro activity against enterococci, Acinetobacter spp., and P. aeruginosa.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was funded by Merck & Co., Rahway, N.J.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bornet C, Davin-Regli A, Bosi C, Pages J M, Bollet C. Imipenem resistance of Enterobacter aerogenes mediated by outer membrane permeability. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1048–1052. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.3.1048-1052.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford P A, Urban C, Jaiswal A, Mariano N, Rasmussen B A, Projan S J, Rahal J J, Bush K. SHV-7, a novel cefotaxime-hydrolyzing β-lactamase, identified in Escherichia coli isolates from hospitalized nursing home patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:899–905. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.4.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charrel R N, Pages J M, De Micco P, Mallea M. Prevalence of outer membrane porin alteration in β-lactam-antibiotic-resistant Enterobacter aerogenes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2854–2858. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craig W A. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1–12. doi: 10.1086/516284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Gheldre Y, Maes N, Rost F, De Ryck R, Clevenbergh P, Vincent J L, Struelens M J. Molecular epidemiology of an outbreak of multidrug-resistant Enterobacter aerogenes infection and in vivo emergence of imipenem resistance. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:152–160. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.152-160.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards J R, Betts M J. Carbapenems: the pinnacle of the β-lactam antibiotics or room for improvement? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;45:1–4. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuchs P C, Barry A L, Brown S D. In-vitro antimicrobial activity of a carbapenem, MK-0826 (L-749,345) and provisional interpretive criteria for disc tests. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:703–706. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.5.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill C J, Jackson J J, Gerckens L S, Pelak B A, Thompson R K, Sundelof J G, Kropp H, Rosen H. In vivo activity and pharmacokinetic evaluation of a novel long-acting carbapenem antibiotic, MK-826 (L-749,345) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1996–2001. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King A, Boothman C, Phillips I. Comparative in-vitro activity of meropenem on clinical isolates from the United Kingdom. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989;24(Suppl. A):31–45. doi: 10.1093/jac/24.suppl_a.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohler J, Dorso K L, Young K, Hammond G G, Rosen H, Kropp H, Silver L L. In vitro activities of the potent, broad-spectrum carbapenem MK-0826 (L-749,345) against broad-spectrum β-lactamase-and extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1170–1176. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Livermore D M. β-Lactamases in laboratory and clinical resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:557–584. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Livermore D M. Are all β-lactams created equal? Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1996;101:33–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Livermore D M, Woodford N. Carbapenemases: a problem in waiting? Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000;3:489–495. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobials disk susceptibility tests, 7th ed. Approved standard M2–A7. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 5th ed. Approved standard M7–A5. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing for anaerobic bacteria, 4th ed. Approved standard M11–A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Development of in vitro susceptibility testing criteria and quality control parameters, 2nd ed. Approved guideline M23–A2. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quinn J P. Clinical strategies for serious infection: a North American perspective. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;31:389–395. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(98)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raimondi A, Traverso A, Nikaido H. Imipenem- and meropenem-resistant mutants of Enterobacter cloacae and Proteus rettgeri lack porins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1174–1180. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.6.1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rasmussen B A, Bush K. Carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:223–232. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rasmussen, B. A., Y. Gluzman, and F. P. Tally. Cloning and sequencing of the class β-lactamase gene (ccrA) from Bacteroides fragilis TAL3636. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:1590–1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Spratt B G. Resistance to antibiotics mediated by target alterations. Science. 1994;264:388–393. doi: 10.1126/science.8153626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walsh T R, Stunt R A, Nabi J A, MacGowan A P, Bennett P M. Distribution and expression of β-lactamase genes among Aeromonas spp. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:171–178. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y, Rasmussen B A, Bush K. Biochemical characterization of the metallo-β-lactamase CcrA from Bacteroides fragilis TAL3636. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1155–1157. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.5.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]