Abstract

Introduction:

Opioid use disorder (OUD) and related comorbid conditions are highly prevalent among patients presenting to emergency department (ED) settings. Research has developed few comprehensive disease management strategies for at-risk patients presenting to the ED that both decrease illicit opioid use and improve initiation and retention in medication treatment for OUD (MOUD).

Methods:

The research team conducted a pilot pragmatic clinical trial that randomized 40 patients presenting to a single ED to a collaborative care intervention (n = 20) versus usual care control (n = 20) conditions. Interviewers blinded to patient intervention and control group status followed-up with participants at 1, 3, and 6 months after presentation to the ED. The 3-month Emergency Department Longitudinal Integrated Care (ED-LINC) collaborative care intervention for patients at risk for OUD included: 1) a Brief Negotiated Interview at bedside, 2) overdose education and facilitation of MOUD, 3) longitudinal proactive care management, 4) utilization of the statewide health information exchange platform for 24/7 tracking of recurrent ED utilization, and 5) weekly caseload supervision that incorporated measurement-based care treatment assessment with stepped-up care for patients with recalcitrant symptoms.

Results:

Overall, the ED-LINC intervention was feasibly delivered and acceptable to patients. The pilot study achieved > 80% follow-up rates at 1, 3, and 6 months. In adjusted longitudinal mixed model regression analyses, no statistically significant differences existed in days of opioid use over the past 30 days for ED-LINC intervention patients when compared to patients receiving usual care (incidence-rate ratio (IRR) 1.50, 95% CI 0.54–4.16). The unadjusted mean number of days of illicit opioid use decreased at the 1-month and 3-month follow-up time points for both groups. ED-LINC intervention patients had increased rates of MOUD initiation compared to control patients (50% versus 30%); intervention versus control comparisons did not achieve statistical significance, although power to detect significant differences in the pilot was limited.

Conclusions:

The ED-LINC intervention for patients with OUD can be feasibly implemented and warrants testing in larger scale, adequately powered randomized pragmatic clinical trial investigations.

Keywords: Emergency medicine, Opioid use disorder, Amphetamine use disorder, Collaborative care, Pragmatic clinical trials, Implementation science

1. Introduction

Opioid use disorder (OUD)1 is a major public health crisis, with an estimated 2.1 million adults living with the disorder in the United States. Drug overdose death has increased and in 2019 more than 80% of overdose deaths involved opioids (O’Donnell, Gladden, Mattson, Hunter, & Davis, 2020). The rate of both fatal and nonfatal opioid overdose continues to rise, despite the successful development of interventions for reducing the prescription of opioids and improving prescription opioid guideline adherence (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020; Lasser et al., 2016; Meisenberg, Grover, Campbell, & Korpon, 2018). Research has shown that medications for OUD (MOUD), such as buprenorphine, methadone and naltrexone, reduce illicit opioid use (Mattick, Breen, Kimber, & Davoli, 2014). Also, patients on MOUD are less likely to overdose compared to patients not on MOUD (Larochelle et al., 2018; Morgan, Schackman, Weinstein, Walley, & Linas, 2019). However, evidence-based treatments for OUD remain underutilized in real-world settings (Larochelle et al., 2018).

Patients with OUD presenting to the emergency department (ED) constitute a complex comorbid patient population with intensive care coordination needs (Duber et al., 2018). These patients experience fragmented health care, difficult ED-to-community care transitions, and recurrent ED visits (Lo-Ciganic et al., 2016; Peterson et al., 2019; Ries et al., 2015; Rockett, Putnam, Jia, Chang, & Smith, 2005). Patients with OUD are often seeking care in the ED for a constellation of presentations, including medical conditions such as skin and soft tissue infections or complications of injection drug use (Collier, Doshani, & Asher, 2018; May, Klein, Martinez, Mojica, & Miller, 2017), other substance use disorders including methamphetamine use (Ellis, Kasper, & Cicero, 2018), comorbid mental illness (A. S. Bohnert et al., 2013; Cicero, Lynskey, Todorov, Inciardi, & Surratt, 2008; Cicero, Surratt, Kurtz, Ellis, & Inciardi, 2012), and chronic or acute pain (A. S. Bohnert et al., 2013; Cicero et al., 2008; Cicero et al., 2012). Additionally, ED visits are rapidly increasing for patients with nonfatal overdoses (Vivolo-Kantor et al., 2018), especially related to combined use of heroin and nonpharmaceutical fentanyl (Tedesco et al., 2017). Social workers can provide services to patients with complex needs in the ED, including substance use referrals and care coordination (Moore et al., 2016). However, much of this work does not extend longitudinally beyond the ED (Whiteside et al., 2017).

Initiating treatment for OUD in the ED is a key evidence-based public health strategy to address the opioid epidemic. Providers can dispense buprenorphine from the ED for patients in acute opioid withdrawal (D’Onofrio, McCormack, & Hawk, 2018; Herring, Perrone, & Nelson, 2019) and emergency physicians with a DATA 2000 waiver can prescribe buprenorphine from the ED for patients with OUD (Babu, Brent, & Juurlink, 2019; Duber et al., 2018). D’Onofrio and colleagues demonstrated improved 30-day retention in treatment and decreased days of illicit opioid use for patients who received ED-initiated buprenorphine at the time of ED discharge (D’Onofrio et al., 2017; D’Onofrio et al., 2015). Buprenorphine initiation can be done from the ED quickly and efficiently but should be combined with a warm hand-off and essential care coordination strategies to facilitate the transition to an outpatient provider for the continuation of treatment. Access to care is a known barrier to OUD treatment initiation and retention (Knudsen & Studts, 2019). A number of programs exist to improve linkage to care for patients in the ED after an opioid overdose (Samuels et al., 2018; Watson et al., 2019), and previous work evaluating care coordination programs from the ED shows decreases in ED utilization and opioid prescriptions (Chase, Bilinski, & Kanzaria, 2020; Neven et al., 2016; Olsen, Ogarek, Goldenberg, & Sulo, 2016) for patients with care coordination needs. Other ED-based interventions, such as take-home naloxone (Walley et al., 2013) and brief intervention utilizing principles of motivational interviewing (MI) (Blow et al., 2017; A.S. Bohnert et al., 2016), have shown efficacy. Providers need to combine these elements systematically to improve longitudinal evidence-based care delivery and incorporate promising multimodal strategies that might not demonstrate effectiveness in isolation.

Comprehensive disease management strategies such as collaborative care are promising approaches for addressing the treatment needs of patients with OUD presenting to the ED. Collaborative care combines evidence-based treatment and care coordination with population-level outcome tracking for patients with complex comorbid presentations. Essential to the collaborative care model is a proactive care manager who engages patients longitudinally and receives ongoing caseload supervision from a multidisciplinary medical team. Collaborative care is effective for patients presenting with mental health, substance use, and medical comorbidities in acute care and primary care settings (Alford et al., 2011; Katon et al., 2010; Roy-Byrne et al., 2010; Unutzer et al., 2002; Watkins et al., 2017; Zatzick et al., 2021; Zatzick et al., 2013; Zatzick et al., 2015; Zatzick et al., 2004). Collaborative care models are flexible enough to incorporate multiple components necessary to address the complex treatment needs of patients with OUD, which can include population-based screening, overdose education, ED initiation of buprenorphine for OUD, and proactive community linkages. Collaborative care can also flexibly incorporate technological innovation with the capacity to enhance 24 hours a day/7 days per week patient communication and tracking. Importantly, providers have used the collaborative care framework in primary care to treat OUD using a nurse care manager to improve initiation and retention with buprenorphine (Alford et al., 2011; Simon et al., 2017).

To date, no randomized studies have tested the effectiveness of collaborative care interventions initiated from the ED targeting patients with OUD. Previous investigation by the study team combined proactive longitudinal case management, opioid medication education, and health information exchange (HIE) technology in a single arm intervention trial targeting injured patients with prescription drug misuse (Whiteside et al., 2017). Although the intervention did not directly target patients with OUD, this single-arm trial suggested the feasibility and acceptability of an ED-initiated collaborative care intervention for patients with substance use and other comorbidities (Whiteside et al., 2017). Methodologists encourage conducting randomized pilot trials of novel interventions as essential preparation for larger, optimally powered randomized clinical trials (Leon, Davis, & Kraemer, 2011). Pilot randomized trials can be flexibly designed to incorporate both assessments of randomized protocol elements and of the intervention implementation process (Leon et al., 2011; Proctor et al., 2009; Rinehart et al., 2021; Zatzick et al., 2021), which is key for informing future fully powered studies.

The Emergency Department Longitudinal Integrated Care (ED-LINC) intervention is a stepped collaborative care model (Miller, Kessler, Peek, & Kallenberg, 2011) initiated from the ED for patients with OUD that combines evidence-based treatment elements, proactive care coordination, and population-level outcome tracking. ED-LINC builds on previous work (Whiteside et al., 2017; Whiteside et al., 2021) by tailoring the collaborative care model for patients at high risk for OUD presenting to the ED. The main objective of this study was to conduct a pilot pragmatic randomized clinical trial of ED-LINC compared to usual care for patients in the ED at high risk for OUD. The primary outcome of this study is feasibility, which we ascertain through a variety of measures. A secondary aim of the study was to conduct an implementation process assessment of the ED-LINC intervention aimed to elucidate the feasibility of delivery of ED-LINC. Although not fully powered, an additional aim of the investigation was to compare rates of heroin use and evaluate differences in initiation of MOUD for patients randomized to the ED-LINC intervention versus usual care control conditions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Setting and patient population

The team conducted this study at Harborview Medical Center (HMC), a large, urban, “safety net” hospital in Seattle, Washington. Study staff approached participants for screening in the ED from 8:00 a.m. until 5:00 p.m. Monday through Friday from December 2018 through June 2019. Eligible patients were English-speaking adults, aged 18–65 with viable contact information or mode of communication such as a phone. The study excluded patients if they were actively suicidal or having a primary psychiatric emergency that required evaluation by an emergency psychiatrist or inpatient psychiatric care, in need of resuscitation in the ED (e.g., tracheal intubation), had a prescription for opioids for treatment of a chronic pain condition, were on hospice or were receiving palliative care, or if they lived ≥ 50 miles from the hospital study site. Because this trial focuses on feasibility, the study team determined a total sample of 40 patients appropriate to gather this information (Leon et al., 2011). The University of Washington institutional review board (IRB) approved the study.

2.2. Screening and recruitment

Each day a member of the study team reviewed the census of current patients in the ED using the electronic medical record (EMR) to pre-screen for study eligibility. To pre-screen, study staff reviewed the EMR for a history of overdose, diagnosis of OUD, previous health care visit related to substance use, chief complaint suggestive of injection drug use (e.g., skin or soft tissue infection), and at least five ED visits in the past 12 months or a prescription for opioids including buprenorphine. Study staff approached patients with at least one of these risk factors for OUD. The study team accepted pre-screen referrals by a patient’s ED clinical team.

Next, a trained research assistant (RA) approached patients for an in-person screen using REDCap on a tablet computer. After verbal consent, possible participants underwent a 5-minute screening procedure to assess eligibility with the NIDA-Modified ASSIST V2.0 (Ali et al., 2002) for illicit opioids (e.g., heroin) and prescription opioid misuse. Patients who endorsed use of heroin or misuse of prescription opioids in the past 30 days and had a score of four or higher on the ASSIST, indicating moderate risk for either illicit opioids and/or prescription opioid misuse, were eligible for enrollment and offered the opportunity to participate after study staff obtained written informed consent.

2.3. Outcomes and assessments

The research team designed the outcome assessments in accordance with the primary and secondary aims of the study. Study staff collected self-report interview assessments at baseline and again at 1-month, 3-month, and 6-month follow-up time points for patients randomized to the intervention and control group conditions.

2.3.1. Primary outcome: Feasibility

The study assessed feasibility of the randomized pilot intervention procedures through ascertainment of rates of recruitment, randomization, and retention of intervention and control group patients over time.

2.3.1. Secondary outcome: Implementation process assessment

The study implementation process assessment tracked the delivery of ED-LINC collaborative care treatment elements as well as barriers and facilitators of treatment delivery among patients randomized to the intervention. Additionally, participants randomized to the EDLINC intervention completed the Intervention Appropriateness Measure (IAM) (Weiner et al., 2017). To assess patient satisfaction/acceptability of care received, all participants completed the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8) (Attkisson & Zwick, 1982) and select questions from the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) (Glasgow et al., 2005).

2.3.3. Secondary outcome: Clinical outcomes

Trained RAs administered the timeline follow back (TLFB) procedure to assess self-report of days of illicit opioid use in the last 30 days at each follow-up time point (Sobell et al., 1996). The study obtained MOUD use by patient self-report at baseline and at each follow-up visit.

2.3.4. Substance use and mental health

The study used the NM-ASSIST to measure heroin use, prescription opioid misuse, and other illicit drug use, including cannabis, cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, sedatives, and hallucinogens. A NM-ASSIST score of 4–26 indicates moderate risk and a score of 27 or higher indicates high risk of use disorder (Ali et al., 2002). The study assessed opioid overdose risk using 11 questions known to correspond to increased risk of opioid overdose, including historical overdose and mixing opioids with other drugs (Banta-Green et al., 2019; A.S. Bohnert et al., 2016). At each follow-up time point, the study asked participants about interim overdose and availability of naloxone. No patients in this study were on naltrexone. The study used the three-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) to assess alcohol misuse or problem alcohol use, using a cut-off of 4 for men and 3 for women to note hazardous drinking (Bradley et al., 2003; Walton et al., 2010). The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) examined depressive symptoms over the last two weeks with the PHQ-9 item 9 assessing the risk for suicidality (Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Lowe, 2006). The study staff administered the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 Questionnaire (GAD-7) to measure anxiety symptoms over the last two weeks (Spitzer et al., 2006). The HIV Risk-Taking Behavior Scale measured injection drug use habits and sexual risk activities such as transactional sex (Darke, Hall, Heather, Ward, & Wodak, 1991).

2.3.5. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

The study obtained information on age, sex, education, employment, and housing at baseline. Study staff derived clinical characteristics, such as ED chief complaint and medical, mental health, and substance-related comorbidities, from the electronic medical record.

2.3.6. Health services utilization

At every follow-up visit, research staff asked participants to report interim health care utilization, including their utilization of primary care and attachment to a particular primary care practice/provider.

2.4. Randomization

The investigation employed a blocked randomization strategy with block sizes of either 4 or 6 participants. Because of the anticipated low number of patients misusing prescription opioids only, the study stratified randomization by this characteristic to ensure group balance. The study RA randomized participants to the ED-LINC intervention or control conditions after completion of the baseline survey. All follow-up interviewers were blinded to patient intervention versus control group status.

2.5. Study conditions

2.5.1. The ED-LINC intervention condition

The study team derived the Emergency Department Longitudinal Integrated Care or ED-LINC intervention development and implementation from prior procedures and a prior single-arm pilot trial (Zatzick et al., 2013; Zatzick et al., 2014, Whiteside et al., 2017). Intervention team members included a board-certified emergency medicine physician (LKW), a psychiatrist (DZ), a licensed clinical social worker (HS), and a care manager trained in motivational interviewing (MI) (LH). The ED-LINC intervention combines evidence-based elements into one care delivery model using principles of collaborative care for patients with high-risk opioid use. ED-LINC elements included: 1) a Brief Negotiated Interview at bedside with an emphasis on motivation to link to services, 2) overdose education targeting illicit opioids or prescription opioid misuse as well as facilitation of MOUD, 4) longitudinal proactive care management for 3-months, 5) care plans in the Emergency Department Information Exchange (EDIE), and 6) weekly caseload supervision allowing for stepped-up care targeting opioid use and comorbidity. All elements are delivered using principles of MI. Over the 3-month intervention period, participants worked with a study care manager (LH) for care coordination, and cases underwent weekly caseload supervision with the study team to discuss treatment plans for OUD and associated comorbidities. The care plan and alerts remained active in EDIE for 6 months to allow for re-engagement and re-linkage back to existing outpatient care networks after a subsequent ED visit.

First, the care manager performed a Brief Negotiated Interview using MI techniques (Zatzick et al., 2014) at the bedside with an emphasis on motivation to link to services. The care manager engaged with patients by respectfully asking open ended questions about their substance use and eliciting change talk through asking about the pros and cons of use. The study assessed readiness for linkage by the scaling question, “On a scale of 1–10, how would you rate your readiness for change?”

Next, the care manager initiated a discussion about prescribed opioid medication management. The care manager reviewed opioid safety and harm reduction practices (e.g., no mixing with other opioids, benzodiazepines, or alcohol). The care manager offered patients take-home naloxone and provided verbal education on how to detect and respond to overdoses. All ED-LINC participants had a patient-centered discussion regarding MOUD, with an emphasis on linking to methadone or starting buprenorphine. The care manager did not routinely discuss naltrexone. In line with patient-centeredness, this conversation was done using principles of MI and considered patient preferences, needs, and values. The care manager then engaged with the primary clinical team for patients interested in buprenorphine and offered support and longitudinal follow-up for linking to methadone. The care manager also worked with the study emergency physician (LKW), who provided technical support to the primary clinical team for prescribing or dispensing buprenorphine as part of routine clinical care.

Care management was a key component of the intervention, wherein the care manager performed longitudinal care management tasks tailored to each individual participant’s needs for approximately three months. The study defined care linkage as linking the patient to outpatient care, which was tailored to participants’ specific needs with a focus on primary care. However, care linkage also included subspecialty care, substance use and mental health services as indicated by the initial assessment in the baseline survey, and medical problems related to the index ED or hospital visit. These care management tasks included calling, texting, or mailing to remind the participant of appointments or scheduling appointments on their behalf, referral to substance use treatment providers, and discussing participant progress and barriers with existing care providers, such as primary care providers, substance use treatment providers, case managers, or social workers. Importantly, many patients had substance use comorbidity, and the care manager actively referred participants as needed to local substance use treatment providers, both at HMC and in the community. As requested by participants, the care manager would coordinate care with existing substance use treatment providers including those providing MOUD. Patients had access to the study phone number, which was immediately answered on weekdays from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., and on the evenings and weekends when patients reported or were suspected of enduring an acute crisis, such as suicidality.

The study used the Emergency Department Information Exchange (EDIE) platform to support ED-LINC delivery. EDIE connects EDs by providing historical ED utilization information from a large database managed by Collective Medical (CM) (Collective Medical Technologies), which enables unaffiliated EDs to share information across electronic medical records. For patients in the ED-LINC intervention, the care manager uploaded an ED-LINC care plan into the EDIE system, which was visible to any emergency provider at the time a patient checked into any subsequent ED within the state of Washington, as well as the CM EDIE network of 22 states. The care plan instructed subsequent providers to call the 24/7 study cell phone. Additionally, EDIE provides real-time workflow integrated electronic alerts that allowed team providers to be notified when ED-LINC patients made recurrent visits to any ED and care coordination efforts were continued for subsequent ED visits.

2.5.2. The usual care condition

The patients randomized to the control condition received usual ED care. Previous investigations at HMC note that patients with substance use comorbidity may receive a spectrum of services, including social work evaluation and referral to services (Moore et al., 2016), referral to outpatient care and overdose education, or brief advice for patients at risk for overdose. At HMC, a program offers prescriptions for naloxone for patients at risk for opioid overdose. Patients can be referred for routine primary care or subspecialty follow-up care for their acute needs, as well as the occasional linkage to outpatient MOUD services depending on the clinical practice of the provider.

2.6. Data analysis

Study staff tabulated baseline characteristics of study participants for categorical variables and calculated univariate statistics for continuous variables. The study tabulated descriptive statistics for all feasibility and acceptability assessments. We used unadjusted and adjusted mixed effects regression models to determine whether patients in the intervention and control group manifested different patterns of change in days of heroin use in the past 30 days (Garson, 2013; Gibbons et al., 1993). The interaction effect allows analysis of the study condition (e.g., ED-LINC) interacting with each timepoint. Both the unadjusted and adjusted models applied a negative binomial distribution to help account for overdispersion of outcome data. The study performed covariate selection for the adjusted model using stepwise selection that combined clinical prioritization of candidate variables with reverse elimination using a p-value threshold of <0.05 (Appendix A). Variables tested in the models included age, probation/warrant and employment status, PHQ-9 and GAD-7 responses, behavioral risk factors including baseline heroin use by any route assessed by the TLFB, number of injections per day, needle reuse, transactional sex, use of multiple substances by TLFB, and baseline methamphetamine use by TLFB. The study calculated a variance inflation factor to rule out collinearity of the covariates retained in the model after selection. The study evaluated model fit via Akaike’s Information Criteria. The model results are presented in terms of incidence-rate ratio, in this case the ratio of the expected count of days of TLFB heroin use.

Study staff performed comparison of any MOUD initiation over three months in the control group versus the intervention group via two-sample test of proportions. The team performed all analyses with Stata 15.1 (College Station, TX).

3. Results

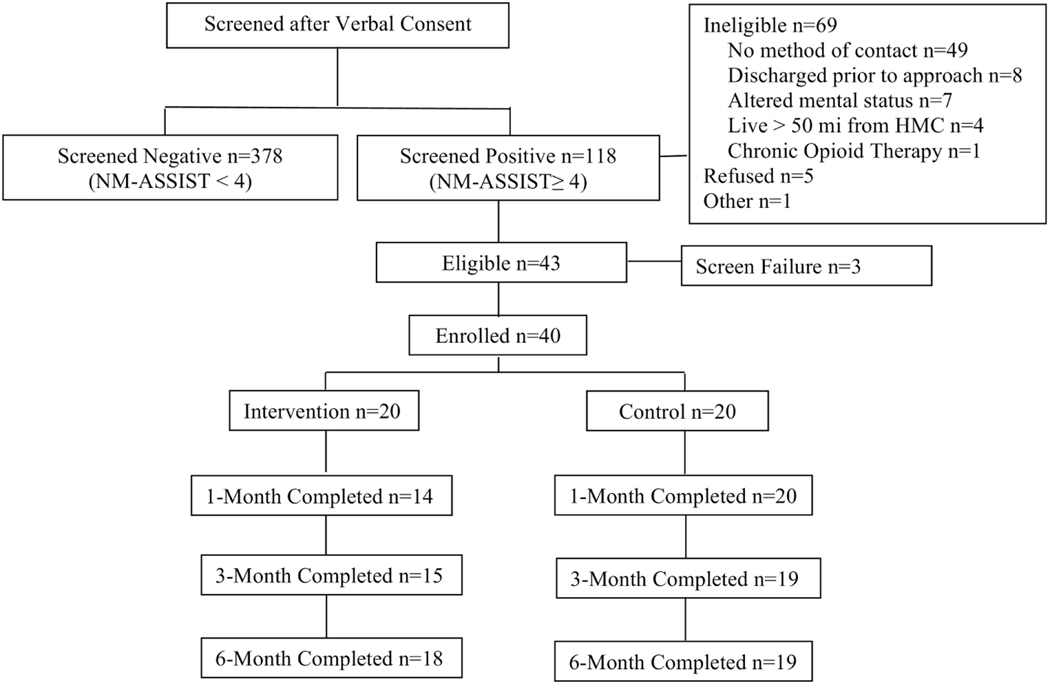

The study screened a total of 496 patients in the ED and 118 (23.4%) had moderate or high risk for OUD from illicit opioids (e.g., heroin) or misuse of prescription opioids. Of these patients, n=69 (58.5%) did not meet further eligibility criteria, n=5 (4.2%) refused participation, and n=43 participants (36%) provided informed consent and initiated the baseline survey. A total of 93% of eligible participants (n=40) completed the baseline and were randomized to the EDLINC intervention (n=20) or the control condition (n=20). Retention in the study over time was high overall, with at least 80% retention at all follow-up time points (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Recruitment flow for ED-LINC

Among those recruited into the trial (n=40), the mean age was 37.4 years (SD 10.0), 45% were female, 57.5% identified as White, 50% were homeless or unstably housed, 90% (n=36) were insured by Medicaid, and 25% were currently on probation or parole, indicating current involvement with the criminal legal system (Table 1). Nearly all (95%, n=38) participants had used heroin in the past 30 days and 30% (n=12) had misused prescription opioids in the past 30 days. Among those who used heroin at least once in the past 30 days, the average number of days of use out of 30 was 18.5 (SD 12.2) and among those who misused prescription opioids at least once in the last 30 days, the average number of days of use out of 30 was 7.9 (SD 10.0). A total of 5% (n=2) screened in for prescription opioid misuse only. Overall, severity of illicit opioid use was high, with the mean NM-ASSIST score for street opioids of 32.8 (SD 6.8) and 82.5% of the sample (n=33) with a score of 27 or higher, indicating high risk for opioid use disorder (OUD). Severity of prescription opioid misuse was lower, with a mean NM-ASSIST score of 17.4 (SD 12.2) and 7.5% (n=3) of the sample with a score of 27 or higher, indicating high risk for use disorder from prescription opioid misuse. More than half (57.5%, n=23) reported a lifetime overdose, and many participants reported high risk for opioid overdose in the past year. Polysubstance use was frequent, and while this was a study of patients with risk for OUD, use of multiple substances among participants was common. Specifically, 65% (n=26) had used three or more illicit substances or misused prescription drugs in the past 30 days. Overall, medical and mental health comorbidity in the sample was also high. More than two-thirds (67.5%, n=27) had symptoms of major depression disorder, 72.5% (n=29) had anxiety, and 30% (n=12) reported acute suicidality at the time of the baseline interview. Nearly one-third (32.5, n=13) were known to be positive for hepatitis C and 2.5 % (n=1) was known to be positive for HIV.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study sample

| Total n=40 | ED-LINC Intervention n=20 | Usual Care Control n=20 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (mean, ±SD) | 37.4 (9.3) | 35.5 (10.7) | 39.3 (9.3) |

| Female, n (%) | 18 (45.0) | 8 (40.0) | 10 (50.0) |

| Race a, n (%) | |||

| White | 23 (57.5) | 11 (55.0) | 12 (60.0) |

| African American/Black | 5 (12.5) | 1 (5.0) | 4 (20.0) |

| Multiple Race | 4 (10.0) | 4 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 5 (20.0) | 4 (20.0) | 4 (20.0) |

| Homeless/unstable housing, n (%) | 20 (50.0) | 8 (40.0) | 12 (60.0) |

| Probation/warrant, n (%) | 10 (25.0) | 3 (15.0) | 7 (35.0) |

| Employed, n (%) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) |

| Unable to work (disabled), n (%) | 7 (17.5) | 5 (25.0) | 2 (10.0) |

| Insurance, n (%) | |||

| Medicaid | 33 (82.5) | 15 (75.0) | 18 (90) |

| Medicare | 3 (7.5) | 2 (10.0) | 1 (5.0) |

| Commercial | 1 (2.5) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Medicare + Medicaid | 3 (7.5) | 2 (10.0) | 1 (5.0) |

| Mental Health, n (%) | |||

| PHQ9 total ≥10 | 27 (67.5) | 15 (75.0) | 12 (60.0) |

| PHQ9 item 9 positive | 12 (30.0) | 8 (40.0) | 4 (20.0) |

| GAD7 total ≥7 | 29 (72.5) | 17 (85.0) | 12 (60.0) |

| Substance use, n (%) | |||

| Lifetime heroin use | 39 (97.5) | 20 (100.0) | 19 (95.0) |

| Lifetime prescription opioid misuse | 25 (62.5) | 12 (60.0) | 13 (65.0) |

| Past 30-day heroin use | 38 (95.0) | 19 (95.0) | 19 (95.0) |

| Past 30-day prescription opioid misuse | 8 (20.5) | 6 (30.0) | 2 (10.5) |

| Past 30-day cocaine use | 12 (30.0) | 6 (30.0) | 6 (30.0) |

| Past 30-day cannabis use | 23 (57.5) | 13 (65.0) | 10 (50.0) |

| Past 30-day amphetamine use | 27 (67.5) | 13 (65.0) | 14 (70.0) |

| Past 30-day alcohol use | 17 (42.5) | 9 (45.0) | 8 (40.0) |

| Past 30-day tobacco use | 35 (87.5) | 19 (95.0) | 16 (80.0) |

| Past 30-day hallucinogen | 6 (15.0) | 5 (25.0) | 1 (5.0) |

| Past 30-day sedative misuse | 14 (35.0) | 7 (35.0) | 7 (35.0) |

| Overdose Risk Questions, n (%) | |||

| Lifetime opioid overdose | 23 (57.5) | 10 (50.0) | 13 (65.0) |

| Past year overdose | 14 (35.0) | 4 (20.0) | 10 (50.0) |

| Use opioid alone | 33 (82.5) | 18 (90.0) | 15 (75.0) |

| Mixed opioids with other drugs | 32 (80.0) | 16 (80.0) | 16 (80.0) |

| HIV Risk Behaviors, n (%) | |||

| HIV positive | 1 (2.5) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| HCV positive | 13 (32.5) | 6 (30.0) | 7 (35.0) |

| Injects more than once 1 day | 22 (56.4) | 11 (57.9) | 11 (55.0) |

| Shares needles | 3 (7.7) | 2 (10.5) | 1 (5.0) |

| Reuse needles | 16 (40.0) | 8 (40.0) | 8 (40.0) |

| Engages in transactional sex | 11 (28.2) | 7 (36.8) | 4 (20.0) |

| Clinical characteristics, n (%) | |||

| ED chief complaint is seeking treatment for OUD | 9 (22.5) | 6 (30.0) | 3 (15.0) |

| ED chief complaint is opioid withdrawal | 2 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) |

| ED chief complaint is overdose | 2 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) |

| ED chief complaint is skin/soft tissue infection | 14 (35.0) | 5 (25.0) | 9 (45.0) |

| ED chief complaint is ‘other’ | 19 (47.5) | 10 (50.0) | 9 (45.0) |

missing three responses, n=37

All participants received at least 1 of the collaborative care elements and a high percentage of intervention patients received multiple collaborative care treatment elements. The ED-LINC case manager was able to successfully complete all six elements of the longitudinal intervention with the majority of participants (Table 2). The mean amount of time the study care manager spent with ED-LINC participants over the three-month intervention time period was 162.3 minutes (interquartile range 68.5–216.5 minutes), and the average amount of time spent coordinating care with providers was 101.2 minutes (interquartile range 29.5–162 minutes) per participant. Nearly all intervention patients (95%) received a Brief Negotiated Interview, and staff offered 100% of intervention participants take-home naloxone. Linkage to care was high for primary care (75%) and mental health providers (65%). All participants received a tailored care plan in EDIE and the care team discussed all participants at least once during the weekly collaborative care supervision.

Table 2.

ED-LINC Process Assessment and Barriers and Facilitators to Intervention Completion

| Variable | n (%) / mean (SD) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Process Assessment of ED-LINC elements | |

|

| |

| Operational/Administrative | |

| Case Manager met patient at bedside in the ED or made contact within one week of ED visit | 18 (90) |

| Brief Negotiated Interview Completed (yes) | 19 (95) |

| Average time reported (mins) | 12.5 (±5.2) |

| Raised the subject/established report | 19 (100) |

| Feedback provided by case manager | 19 (100) |

| Enhanced Motivation and assessed readiness to change | 19 (100) |

| Did the Care Manager Negotiate a Plan | 19 (100) |

| Overdose Education and Medications for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) | 19 (95) |

| Offered take-home naloxone | 20 (100) |

| Initiated or continued MOUD | 17 (85) |

| Referral to outpatient MOUD provider | 2 (10) |

| Longitudinal Care Management | |

| Provided patient with Case Manager 24/7 phone number | 20 (100) |

| Linked to new PCP or assisted with reestablishing with existing PCP | 15 (75) |

| Linked to mental health provider | 13 (65) |

| Successful new mental health referral by care manager/study team | 8 (40) |

| Care Plan in EDIE | 20 (100) |

| Weekly Caseload supervision | |

| Reviewed Case 1+ times at weekly supervision meeting | 20 (100) |

| Discussed care coordination and referral to treatment at the weekly | 20 (100) |

| supervision meeting | |

| Discussed Pharmacotherapy during the weekly supervision meeting | 16 (80) |

|

| |

| Barriers to Providing ED-LINC Intervention | |

|

| |

| Crisis | 12 (60) |

| Acute Suicidal or Homicidal Ideation | 7 (35) |

| Interpersonal Violence | 8 (40) |

| Clinical | 17 (85) |

| Severe Medical Illness | 8 (40) |

| Psychosis, mania, bipolar or schizophrenia symptoms | 7 (35) |

| Severe cognitive impairment, TBI or dementia | 3 (15) |

| Taking a benzodiazepine | 6 (30) |

| Alcohol Use or Alcohol Use Disorder | 6 (30) |

| Logistical Factors | 20 (100) |

| Housing | 13 (65) |

| Financial or Insurance | 17 (85) |

| Transportation or distance from treatment center | 13 (65) |

| Phone Access | 18 (90) |

| Legal Involvement | 9 (45) |

| Other Treatment Considerations | 9 (45) |

| Stigma: Concerns for confidentiality, labeling, rejection or embarrassment | 7 (35) |

| Preference for Alternate Treatment | 1 (5) |

| Sees no utility in treatment/ does not buy into rational | 2 (10) |

|

| |

| Facilitators to Providing ED-LINC Intervention | |

|

| |

| Psychological/Behavioral Facilitators | 15 (75) |

| Patient is psychologically minded | 14 (70) |

| Patient is able to keep appointments | 10 (50) |

| Treatment History Facilitators | |

| Patient reported positive prior experience with MOUD | 10 (50) |

| Care Manager Facilitators | 13 (65) |

| Patient has benefited from the ED-LINC intervention | 12 (60) |

| Patient independently contacted the study team | 9 (45) |

| Family or friend support for treatment participation | 12 (60) |

All intervention participants had at least one logistical barrier to intervention delivery; the most common logistical barriers were phone access (90%) and financial or insurance (90%) barriers (Table 2). Other documented barriers included crisis (e.g., acute suicidality) and barriers to treatment such as stigma. Facilitators to receiving the intervention included ability to keep appointments (50%) and previous positive experience with MOUD (50%). On the IAM at 6months, 18 participants “agreed” or “completely agreed” that ED-LINC seemed fitting and suitable, and 17 participants “agreed” or “completely agreed” that ED-LINC seemed applicable and like a good match for their care needs. Overall satisfaction with the ED-LINC protocol was high for both intervention (CSQ median = 29, interquartile range (IQR) = 6) and control group (CSQ median = 30, IQR = 6) participants. No significant differences existed in PACIC scores between patients randomized to the intervention and control group conditions (Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test, p = 0.38).

Overall, the mean number of days of illicit opioid use in the past 30 days decreased at the 1-month and 3-month follow-up time points for both groups (Table 3 and Figure 2). At the end of the 3-month intervention, patients randomized to ED-LINC had on average 3.5 fewer days of heroin use in the past 30 days compared to patients randomized to the control group (Figure 2). In adjusted mixed model regression, these 3-month differences did not achieve statistical significance (IRR 0.46, 95% CI 0.13, 1.58), and no significant differences occurred between intervention and control patients over the course of the 6-month investigation (Table 3). Greater baseline heroin use and injecting multiple times at baseline were associated with significantly greater heroin use longitudinally (Table 3).

Table 3.

Covariate-Adjusted Mixed Effects Regression Model for Past 30-day Heroin Use

| Incidence-Rate Ratio | Standard Error | P-value | 95% Confidence Interval |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower CI | Upper CI | ||||

|

| |||||

| Collaborative Care intervention (vs. control) | 1.50 | 0.78 | 0.44 | 0.54 | 4.16 |

| Baseline heroin use | 1.06 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1.02 | 1.09 |

|

| |||||

| TLFB a timepoint (vs. baseline) | |||||

| Month 1 | 0.47 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.21 | 1.09 |

| Month 3 | 0.40 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.92 |

| Month 6 | 0.26 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.63 |

|

| |||||

| Interaction between collaborative care intervention and TLFB timepoint (vs. control, baseline) | |||||

| Intervention at 1 mo. | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.16 | 1.82 |

| Intervention at 3 mo. | 0.46 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 1.58 |

| Intervention at 6 mo. | 1.29 | 0.80 | 0.68 | 0.38 | 4.37 |

|

| |||||

| Multiple injections daily (vs. no) | 4.28 | 1.93 | 0.00 | 1.77 | 10.37 |

Timeline Follow Back

Figure 2.

Unadjusted Days of Heroin Use in the last 30 days with 95% Confidence Intervals

Over the course of the intervention period, six patients initiated buprenorphine and four patients initiated methadone for a total of 10 (50%) new initiations of MOUD in the ED-LINC group while three patients initiated buprenorphine and three patients initiated methadone in the control group for a total of 6 (30%) new initiations of MOUD. The comparison for any new MOUD initiation did not achieve statistical significance (mean difference = 0.2, standard error = 0.15, 95% CI –0.10, 0.50).

4. Discussion

This is the first randomized clinical trial of a collaborative care intervention initiated from the ED for patients with risk for OUD and associated comorbidity. The pilot demonstrated the feasibility of initiating the intervention in the ED with ongoing treatment for 3 months. The refusal rate for study participation was low, and combined retention in both arms of the study was greater than 80% at the 1-, 3- and 6-month time points.

The collaborative care model may be an optimal approach for addressing the multiple comorbidities observed in patients with OUD (O’Gurek et al., 2021). Overall, the rate of polysubstance use in this trial was high, while nearly two-thirds of the sample used at least three substances in the past 30 days. Notably, 67.5% of patients in this trial reported baseline use of methamphetamine in the past 30 days. Previous work notes that nearly all people who use heroin report using at least one other drug during the past year (Jones, Logan, Gladden, & Bohm, 2015), and simultaneous methamphetamine and heroin use is on the rise (Al-Tayyib, Koester, Langegger, & Raville, 2017; Glick, Klein, Tinsley, & Golden, 2020). Patients who use methamphetamine and opioids are less likely to be retained in traditional buprenorphine care compared to patients who do not use methamphetamine (Tsui et al., 2020). The ED can serve as a low-barrier place to initiate buprenorphine (Snyder et al., 2021), especially for patients who might not be seeking treatment. Additionally, the ED is an optimal place to serve patients with OUD who historically have not been able to engage with outpatient care.

The collaborative care model can also flexibly adapt to patients’ circumstances especially as circumstances change longitudinally. Importantly, the study care manager identified barriers to providing the ED-LINC intervention to all participants. Documentation of these barriers allows for future work to incorporate these into the ED-LINC model. For example, 90% of patients had barriers to stable phone access and thus developing procedures and protocols to meet patients at clinic and in the ED for future visits is important to continue engagement and intervention activities. Likewise, 85% of patients had a clinical barrier to ED-LINC such as development of suicidal ideation or a co-existing benzodiazepine prescription. ED-LINC patients with psychiatric crisis often required emergency evaluation, including referral to the ED by the research care manager. Patients with substance use disorder and co-existing suicidal ideation are at high risk for overdose and death (A. S. B. Bohnert & Ilgen, 2019; Gicquelais et al., 2020). For patients in a constant state of crisis, care coordination efforts are often disrupted from care fragmentation and lack of health information sharing across systems.

The ED-LINC model allows for care coordination across a spectrum of providers for a constellation of patients. Specifically, our ED-LINC care plan integrated into the Emergency Department Information Exchange (EDIE) is pushed to providers at the time of any new ED visit. Also, the care manager can move through care settings to meet patients in the ED, inpatient space or outpatient space to help coordinate care and ensure a focus on OUD treatment. Importantly, some patients in ED-LINC were reluctant to engage in coordinated care, especially related to changes in existing medications. Work to decrease stigma and incorporate patient choice in treatment options while respecting privacy is essential to implementing coordinated care (Fox, Masyukova, & Cunningham, 2016). ED-LINC components involving stepped care and feasibly delivered linkages, and patients with multiple comorbidities found the protocol acceptable.

ED-initiated buprenorphine is now considered standard of care for the treatment of acute opioid withdrawal (Herring et al., 2019), and an increasing number of emergency providers are getting an X-waiver to prescribe buprenorphine at discharge. Despite recent and important changes that have decreased barriers to obtaining an X-waiver, barriers to prescribing buprenorphine from the ED still exist. Even without the requirement for the formal training course, barriers include lack of a systematic process, training of all health care workers, including nurses and pharmacists, and lack of outpatient partners for referral (Fockele, Duber, Finegood, Morse, & Whiteside, 2021; Hawk et al., 2020; Lowenstein et al., 2019). The study team conducted this pilot trial at a site that had a protocol and pathway for ED-initiated buprenorphine adapted for site specifics from publicly available resources (Crotty, Freedman, & Kampman, 2020; Yale Department of Emergency Medicine), as well as a group of ED providers with a DATA 2000 waiver to prescribe buprenorphine. It is important to note that while participants in both the control and ED-LINC intervention group had initiation of MOUD over the course of the study, ED-initiated buprenorphine will not benefit patients who prefer or are more appropriate for methadone or who are not appropriate for MOUD at the time of the ED visit due to acute pain (e.g., fracture) (Kampman & Jarvis, 2015). Many patients with OUD are in the ED for other acute issues seemingly unrelated to OUD (e.g., chest pain) and thus may not have considered initiating treatment. Interventions for patients with OUD in the ED need to adapt to a population that is not necessarily treatment seeking and may have competing health care demands. Also, buprenorphine treatment alone does not address the full constellation of comorbid medical, mental health, and substance use disorders highly prevalent in patients with OUD. Approximately two-thirds or more of ED-LINC intervention patients noted barriers such as transportation, phone access, and financial or insurance challenges. A recent study of care navigation among patients with substance use disorders seen in an inpatient setting noted similar challenges, which can be addressed through navigation (Gryczynski et al., 2021). In an audit study conducted in multiple states, many publicly listed buprenorphine prescribers were not accepting new patients, and those who did cited an average wait time of six days for an appointment (Lee et al., 2019). These observations serve as a reminder that many barriers exist to accessing care once the ED visit ends even if patients receive MOUD from the ED.

While this investigation provides important information on the feasibility of this novel intervention for patients with OUD, the study has some important limitations to consider. First, the research team conducted this study at a single-site urban academic ED and results may not translate to rural or suburban populations. Participants needed to have viable contact information such as a phone to be included, which may exclude patients who have a hard time accessing medical care and are at high-risk for overdose. Future work should consider ways that cell phone access and connectivity may improve health outcomes. The inclusion criteria that this study used for participant selection was an NM-ASSIST (Ali et al., 2002) score of four or higher, which is associated with moderate risk for OUD. While the majority of participants had a score of 27 or higher, indicating high risk for OUD, as well as use characteristics associated with risky use such as injection use and daily use, the study did not systematically screen participants for OUD. This workflow mimics real-world emergency medicine job design, where providers are not often conducting lengthy psychologic assessments and providing a formal Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) diagnosis of OUD. The study did not systematically tracj components of usual care received in the ED at the time of randomization to allow for comparisons with the ED-LINC group. At follow-up assessments, participants self-reported methadone and buprenorphine use for OUD and the study did not verify this outcome of MOUD through administrative data and/or provider contact. Likewise, we do not have administrative data on naloxone or other medications. The study did not confirm self-report assessments for illicit substance use with biomarkers. Previous work has noted the reliability of self-report as well as the limitations of biomarkers in emergency medicine research related to opioids and other substances (Vitale, van de Mheen, van de Wiel, & Garretsen, 2006). Additionally, self-report assessments for opioids did not distinguish non-pharmaceutical fentanyl use from other types of illicit opioid use such as heroin. Finally, the study observed some differential follow-up between the intervention and control group participants at the 1-month assessment.

Nevertheless, the results of this pilot investigation suggest a number of future directions for research. A larger, adequately powered investigation of the ED-LINC intervention could target patient-reported opioid use outcomes and meaningful administrative outcomes such as MOUD initiation and retention from prescription records as well as health service utilization data derived from health information exchanges that document emergency department utilization (Whiteside et al., 2021; Zatzick et al., 2018) for the intent-to-treat sample. Also, recently established reimbursement codes for the delivery of collaborative care interventions could be expanded for use with patients diagnosed OUD in primary care. To expand the use and generalizability of the ED-LINC intervention beyond the research context, future investigation of the ED-LINC intervention could assess the feasibility of applying these codes in the acute care medical setting. Likewise, providers could use of the recently approved Medicare add-on code for Medication-Assisted Treatment in the Emergency Department (Davis, 2021) to assist with funding ED-LINC in the future if effectiveness of the intervention is established. Finally, the ED-LINC intervention should be flexibly adapted to address new developments in the opioid crises, such as the proliferation of non-pharmaceutical fentanyl, which may lead to different demographics and use patterns (Kral et al., 2021).

5. Conclusions

The results of this pilot study suggest that the ED-LINC collaborative care intervention for patients with OUD is feasible and acceptable to patients. Additionally, retention rates for patient-reported outcomes were high and critical research procedures showed feasibility. A fully powered randomized trial of the ED-LINC intervention compared to care as usual can help to determine if this intervention could improve MOUD initiation and retention, reduce illicit opioid use, and impact health services utilization. The ED-LINC intervention warrants testing in larger scale, adequately powered randomized pragmatic clinical trial investigations.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Collaborative care interventions targeting opioid use disorder can be feasibly delivered from the emergency department.

Implementation process assessments can enhance pilot feasibility studies initiated in the Emergency Department.

In this pilot study (N=40) patients receiving the ED-LINC intervention demonstrated no difference in heroin use in the past 30 days when compared to patients receiving usual care, but sample size was limited.

Acknowledgments

Role of the funding source: The NIH had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

This work was funded through the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23DA039974) and within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory by cooperative agreement 1UH2MH106338–01/4UH3MH106338–02 from the NIH Common Fund and by UH3 MH 106338–05S1 from NIMH. Support was also provided by the NIH Common Fund through cooperative agreement U24AT009676 from the Office of Strategic Coordination within the Office of the NIH Director. All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the Authors’ and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIH. The preparation of this article was supported in part by the Implementation Research Institute (IRI), at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis; through an award from the National Institute of Mental Health (5R25MH08091607).

Presentation of findings at the Center for Prevention and Implementation Methodology (CPIM) Virtual Grand Rounds Dec 12, 2019

Footnotes

OUD: opioid use disorder; MOUD: medications for opioid use disorder; ED: emergency department; ED-LINC: Emergency Department Longitudinal Integrated Care; HMC: Harborview Medical Center; EMR: electronic medical record; RA: research assistant; HIE: health information exchange; IAM: Intervention Appropriateness Measure; CSQ-8: Client Satisfaction Questionnaire; PACIC: Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care; TLFB: timeline follow back; MI: motivational interviewing; AUDIT-C: Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 Questionnaire

Declarations of interest: none

CRediT author statement

Lauren Whiteside: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Funding Acquisition. Ly Huynh: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Project Administration. Sophie Morse: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation. Jane Hall: Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Methodology, Writing – Review and Editing. William Meurer: Conceptualization, Supervision, Caleb Banta-Green, Hannah Scheuer: Methodology, Formal Investigation, Data Curation, Rebecca Cunningham: Conceptualization, Supervision Mark McGovern: Conceptualization, Validation, Supervision. Douglas Zatzick: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Funding Acquisition, Supervision

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Al-Tayyib A, Koester S, Langegger S, & Raville L (2017). Heroin and Methamphetamine Injection: An Emerging Drug Use Pattern. Subst Use Misuse, 52(8), 1051–1058. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1271432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Kretsch N, Bergeron A, Winter M, Botticelli M, & Samet JH (2011). Collaborative care of opioid-addicted patients in primary care using buprenorphine: five-year experience. Arch Intern Med, 171(5), 425–431. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali R, Awwad E, Babor TF, Bradley F, Butau T, Farrell M, Formigoni MLOS, Isralowitz R, de Lacerda RB, Marsden J, McRee B, Monteiro M, Pal H, RubioStipec M, Vendetti J, WHO ASSIST Working Grp (2002). The alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction, 97(9), 1183–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attkisson CC, & Zwick R (1982). The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval Program Plann, 5(3), 233–237. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu KM, Brent J, & Juurlink DN (2019). Prevention of Opioid Overdose. N Engl J Med, 380(23), 2246–2255. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1807054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banta-Green CJ, Coffin PO, Merrill JO, Sears JM, Dunn C, Floyd AS, Whiteside LK, Yanez ND, Donovan DM (2019). Impacts of an opioid overdose prevention intervention delivered subsequent to acute care. Injury prevention : journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention, 25(3), 191–198. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow FC, Walton MA, Bohnert AS, Ignacio RV, Chermack S, Cunningham RM, Booth BM, Ilgen M, Barry KL (2017). A randomized controlled trial of brief interventions to reduce drug use among adults in a low-income urban emergency department: the HealthiER You study. Addiction. doi: 10.1111/add.13773 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bohnert AS, Bonar EE, Cunningham R, Greenwald MK, Thomas L, Chermack S, Blow FC, Walton M (2016). A pilot randomized clinical trial of an intervention to reduce overdose risk behaviors among emergency department patients at risk for prescription opioid overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend, 163, 40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert AS, Eisenberg A, Whiteside L, Price A, McCabe SE, & Ilgen MA (2013). Prescription opioid use among addictions treatment patients: nonmedical use for pain relief vs. other forms of nonmedical use. Addict Behav, 38(3), 1776–1781. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert ASB, & Ilgen MA (2019). Understanding Links among Opioid Use, Overdose, and Suicide. N Engl J Med, 380(1), 71–79. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1802148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ, Dobie DJ, Davis TM, Sporleder JL, Marynard C, Burman ML, Kivlahan DR (2003). Two brief alcohol-screening tests from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): Validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch Intern Med, 163(7), 821–829. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821163/7/821 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Overdose Deaths Accelerating During COVID-19 [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p1218-overdose-deaths-covid-19.html

- Chase J, Bilinski J, & Kanzaria HK (2020). Caring for Emergency Department Patients With Complex Medical, Behavioral Health, and Social Needs. JAMA, 324(24), 2550–2551. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ, Lynskey M, Todorov A, Inciardi JA, & Surratt HL (2008). Co-morbid pain and psychopathology in males and females admitted to treatment for opioid analgesic abuse. Pain, 139(1), 127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ, Surratt HL, Kurtz S, Ellis MS, & Inciardi JA (2012). Patterns of prescription opioid abuse and comorbidity in an aging treatment population. J Subst Abuse Treat, 42(1), 87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collective Medical Technologies. The Emergency Department Information Exchange. Retrieved from http://collectivemedicaltech.com/what-we-do-2/edie-option-2/

- Collier MG, Doshani M, & Asher A (2018). Using Population Based Hospitalization Data to Monitor Increases in Conditions Causing Morbidity Among Persons Who Inject Drugs. J Community Health, 43(3), 598–603. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0458-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crotty K, Freedman KI, & Kampman KM (2020). Executive Summary of the Focused Update of the ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 14(2), 99–112. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio G, Chawarski MC, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, Busch SH, Owens PH, Hawk K, Bernstein SL, Fiellin DA (2017). Emergency Department-Initiated Buprenorphine for Opioid Dependence with Continuation in Primary Care: Outcomes During and After Intervention. J Gen Intern Med, 32(6), 660–666. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-3993-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio G, McCormack RP, & Hawk K (2018). Emergency Departments - A 24/7/365 Option for Combating the Opioid Crisis. N Engl J Med, 379(26), 2487–2490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1811988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Busch SH, Owens PH, Bernstein SL Fiellin DA (2015). Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 313(16), 1636–1644. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Hall W, Heather N, Ward J, & Wodak A (1991). The reliability and validity of a scale to measure HIV risk-taking behaviour among intravenous drug users. Aids, 5(2), 181–185. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199102000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J (2021). The New Medicare Add-on Code for Medication-Assisted Treatment in the Emergency Department -- Got Questions? ACEP’s Got Answers. [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.acep.org/federal-advocacy/federal-advocacy-overview/regs-eggs/regs--eggs-articles/regs--eggs-february-11-2021/

- Duber HC, Barata IA, Cioe-Pena E, Liang SY, Ketcham E, Macias-Konstantopoulos W, Ryan SA, Stavros M, Whiteside LK (2018). Identification, Management, and Transition of Care for Patients With Opioid Use Disorder in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med, 72(4), 420–431. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis MS, Kasper ZA, & Cicero TJ (2018). Twin epidemics: The surging rise of methamphetamine use in chronic opioid users. Drug Alcohol Depend, 193, 14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fockele CE, Duber HC, Finegood B, Morse SC, & Whiteside LK (2021). Improving transitions of care for patients initiated on buprenorphine for opioid use disorder from the emergency departments in King County, Washington. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open, 2(2), e12408. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AD, Masyukova M, & Cunningham CO (2016). Optimizing psychosocial support during office-based buprenorphine treatment in primary care: Patients’ experiences and preferences. Subst Abus, 37(1), 70–75. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2015.1088496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garson G (2013). Fundamentals of hierarchical linear and multilevel modeling. Hierarchical linear modeling: Guide and applications. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons RD, Hedeker D, Elkin I, Waternaux C, Kraemer HC, Greenhouse JB, Shea MT, Imber SD, Sotsky SM, Watkins JT (1993). Some conceptual and statistical issues in analysis of longitudinal psychiatric data. Arch Gen Psychiat, 50, 739–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gicquelais RE, Jannausch M, Bohnert ASB, Thomas L, Sen S, & Fernandez AC (2020). Links between suicidal intent, polysubstance use, and medical treatment after non-fatal opioid overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend, 212, 108041. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Wagner EH, Schaefer J, Mahoney LD, Reid RJ, & Greene SM (2005). Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC). Med Care, 43(5), 436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick SN, Klein KS, Tinsley J, & Golden MR (2020). Increasing Heroin-Methamphetamine (Goofball) Use and Related Morbidity Among Seattle Area People Who Inject Drugs. Am J Addict. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gryczynski J, Nordeck CD, Welsh C, Mitchell SG, O’Grady KE, & Schwartz RP (2021). Preventing Hospital Readmission for Patients With Comorbid Substance Use Disorder. Ann Intern Med. doi: 10.7326/M20-5475 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hawk KF, D’Onofrio G, Chawarski MC, O’Connor PG, Cowan E, Lyons MS, Richardson L, Rothman RE, Whiteside LK, Owens PH, Martel SH, Coupet E Jr, Pantalon M, Curry L, Fielin DA, Edelman EJ (2020). Barriers and Facilitators to Clinician Readiness to Provide Emergency Department-Initiated Buprenorphine. JAMA Netw Open, 3(5), e204561. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.4561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herring AA, Perrone J, & Nelson LS (2019). Managing Opioid Withdrawal in the Emergency Department With Buprenorphine. Ann Emerg Med, 73(5), 481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Logan J, Gladden M, & Bohm MK (2015). Vital Signs: Demographic and Substance Use Trends Among Heroin Users - United States, 2002–2013. MmwrMorbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64(26), 719–725. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampman K, & Jarvis M (2015). American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) National Practice Guideline for the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use. J Addict Med, 9(5), 358–367. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, Young B, Peterson D, Rutter CM, McGregor M, McCulloch D (2010). Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. New England Journal of Medicine, 363(27), 26112620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, & Studts JL (2019). Physicians as Mediators of Health Policy: Acceptance of Medicaid in the Context of Buprenorphine Treatment. J Behav Health Serv Res, 46(1), 151–163. doi: 10.1007/s11414-018-9629-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral AH, Lambdin BH, Browne EN, Wenger LD, Bluthenthal RN, Zibbell JE, & Davidson PJ (2021). Transition from injecting opioids to smoking fentanyl in San Francisco, California. Drug Alcohol Depend, 227, 109003. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larochelle MR, Bernson D, Land T, Stopka TJ, Wang N, Xuan Z, Bagley SM, Liebschutz JM, Walley AY (2018). Medication for Opioid Use Disorder After Nonfatal Opioid Overdose and Association With Mortality: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med, 169(3), 137–145. doi: 10.7326/M17-3107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser KE, Shanahan C, Parker V, Beers D, Xuan Z, Heymann O, Lange A, Liebschutz JM (2016). A Multicomponent Intervention to Improve Primary Care Provider Adherence to Chronic Opioid Therapy Guidelines and Reduce Opioid Misuse: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial Protocol. J Subst Abuse Treat, 60, 101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, Rosales R, Stein MD, Nicholls M, O’Connor BM, Loukas Ryan V, & Davis EA (2019). Brief Report: Low-Barrier Buprenorphine Initiation Predicts Treatment Retention Among Latinx and Non-Latinx Primary Care Patients. Am J Addict. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Leon AC, Davis LL, & Kraemer HC (2011). The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. Journal of psychiatric research, 45(5), 626–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo-Ciganic WH, Gellad WF, Gordon AJ, Cochran G, Zemaitis MA, Cathers T, Kelley D, Donohue JM (2016). Association between trajectories of buprenorphine treatment and emergency department and in-patient utilization. Addiction, 111(5), 892–902. doi: 10.1111/add.13270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein M, Kilaru A, Perrone J, Hemmons J, Abdel-Rahman D, Meisel ZF, & Delgado MK (2019). Barriers and facilitators for emergency department initiation of buprenorphine: A physician survey. Am J Emerg Med, 37(9), 1787–1790. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, & Davoli M (2014). Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(2). doi:ARTN CD002207 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- May L, Klein EY, Martinez EM, Mojica N, & Miller LG (2017). Incidence and factors associated with emergency department visits for recurrent skin and soft tissue infections in patients in California, 2005–2011. Epidemiol Infect, 145(4), 746–754. doi: 10.1017/S0950268816002855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisenberg BR, Grover J, Campbell C, & Korpon D (2018). Assessment of Opioid Prescribing Practices Before and After Implementation of a Health System Intervention to Reduce Opioid Overprescribing. JAMA Netw Open, 1(5), e182908. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BF, Kessler R, Peek CJ, & Kallenberg GA (2011). A national agenda for research in collaborative care: Papers from the collaborative care research network research development conference. Retrieved from Rockville: [Google Scholar]

- Moore M, Whiteside LK, Dotolo D, Wang J, Ho L, Conley B, Forrester M, Fouts SO, Vavilala MS, Zatzick DF (2016). The Role of Social Work in Providing Mental Health Services and Care Coordination in an Urban Trauma Center Emergency Department. Psychiatr Serv, 67(12), 1348–1354. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JR, Schackman BR, Weinstein ZM, Walley AY, & Linas BP (2019). Overdose following initiation of naltrexone and buprenorphine medication treatment for opioid use disorder in a United States commercially insured cohort. Drug Alcohol Depend, 200, 34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.02.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neven D, Paulozzi L, Howell D, McPherson S, Murphy SM, Grohs B, Grohs B, Marsh, Lederhos C, Roll J (2016). A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Citywide Emergency Department Care Coordination Program to Reduce Prescription Opioid Related Emergency Department Visits. J Emerg Med, 51(5), 498–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.06.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell J, Gladden RM, Mattson CL, Hunter CT, & Davis NL (2020). Vital Signs: Characteristics of Drug Overdose Deaths Involving Opioids and Stimulants - 24 States and the District of Columbia, January-June 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 69(35), 1189–1197. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6935a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Gurek DT, Jatres J, Gibbs J, Latham I, Udegbe B, & Reeves K (2021). Expanding buprenorphine treatment to people experiencing homelessness through a mobile, multidisciplinary program in an urban, underserved setting. J Subst Abuse Treat, 127, 108342. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JC, Ogarek JL, Goldenberg EJ, & Sulo S (2016). Impact of a Chronic Pain Protocol on Emergency Department Utilization. Acad Emerg Med, 23(4), 424–432. doi: 10.1111/acem.12942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Liu Y, Xu L, Nataraj N, Zhang K, & Mikosz CA (2019). U.S. National 90-Day Readmissions After Opioid Overdose Discharge. Am J Prev Med, 56(6), 875–881. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, & Mittman B (2009). Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Adm Policy Ment Health, 36(1), 24–34. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries R, Krupski A, West II, Maynard C, Bumgardner K, Donovan D, Dunn C, Roy-Byrne P (2015). Correlates of Opioid Use in Adults With Self-Reported Drug Use Recruited From Public Safety-Net Primary Care Clinics. J Addict Med, 9(5), 417–426. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinehart DJ, Stowell M, Collings A, Durfee MJ, Thomas-Gale T, Jones HE, & Binswanger I (2021). Increasing access to family planning services among women receiving medications for opioid use disorder: A pilot randomized trial examining a peerled navigation intervention. J Subst Abuse Treat, 126, 108318. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockett IR, Putnam SL, Jia H, Chang CF, & Smith GS (2005). Unmet substance abuse treatment need, health services utilization, and cost: a population-based emergency department study. Ann Emerg Med, 45(2), 118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Byrne P, Craske MG, Sullivan G, Rose RD, Edlund MJ, Lang AJ, Bystritsky A, Welch SS, Chavira DA, Golinelli D, Campbell-Sills L, Sherbourne CD, Stein MB (2010). Delivery of evidence-based treatment for multiple anxiety disorders in primary care: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 303(19), 1921–1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels EA, Bernstein SL, Marshall BDL, Krieger M, Baird J, & Mello MJ (2018). Peer navigation and take-home naloxone for opioid overdose emergency department patients: Preliminary patient outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat, 94, 29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon CB, Tsui JI, Merrill JO, Adwell A, Tamru E, & Klein JW (2017). Linking patients with buprenorphine treatment in primary care: Predictors of engagement. Drug Alcohol Depend, 181, 58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder H, Kalmin MM, Moulin A, Campbell A, Goodman-Meza D, Padwa H, Clayton S, Speener M, Shoptaw S, Herring AA (2021). Rapid Adoption of Low-Threshold Buprenorphine Treatment at California Emergency Departments Participating in the CA Bridge Program. Ann Emerg Med. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Buchan G, Cleland PA, Fedoroff I, & Leo GI (1996). The Reliability of the Timeline Follow Back method applied to drug, cigarette and cannabis use. Paper presented at the 30th Meeting of the Assocication for Advancement of Behavior Therapy, New York City, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, & Lowe B (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med, 166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco D, Asch SM, Curtin C, Hah J, McDonald KM, Fantini MP, & HernandezBoussard T (2017). Opioid Abuse And Poisoning: Trends In Inpatient And Emergency Department Discharges. Health Affairs, 36(10), 1748–1753. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui JI, Mayfield J, Speaker EC, Yakup S, Ries R, Funai H, Leroux BG Merrill JO (2020). Association between methamphetamine use and retention among patients with opioid use disorders treated with buprenorphine. J Subst Abuse Treat, 109, 80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW Jr., Hunkeler E, Harpole L, Hoffing M, Della Penna RD, Lin EH, Arean PA, Hegel MT, Tang L, Belin TR, Oishi S, Langston C Impact Investigators. (2002). Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 288(22), 2836–2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale SG, van de Mheen H, van de Wiel A, & Garretsen HFL (2006). Substance use among emergency room patients: Is self-report preferable to biochemical markers? Addict Behav, 31(9), 1661–1669. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivolo-Kantor AM, Seth P, Gladden RM, Mattson CL, Baldwin GT, Kite-Powell A, & Coletta MA (2018). Vital Signs: Trends in Emergency Department Visits for Suspected Opioid Overdoses - United States, July 2016-September 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 67(9), 279–285. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6709e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, Quinn E, Doe-Simkins M, Sorensen-Alawad A, . . . Ozonoff A (2013). Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ, 346, f174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton, Chermack ST, Shope JT, Bingham CR, Zimmerman MA, Blow FC, & Cunningham RM (2010). Effects of a Brief Intervention for Reducing Violence and Alcohol Misuse Among Adolescents. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 304(5), 527–535. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins KE, Ober AJ, Lamp K, Lind M, Setodji C, Osilla KC, Hunter SB, McCullough CM, Becker K, Iyiewuare PO, Diamant A, Heinzerling K, Pincus HA (2017). Collaborative Care for Opioid and Alcohol Use Disorders in Primary Care: The SUMMIT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med, 177(10), 1480–1488. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson DP, Brucker K, McGuire A, Snow-Hill NL, Xu H, Cohen A, Campbell M, Robison L, Sightes E, Buhner R, O’Donnell D, Kline JA (2019). Replication of an emergency department-based recovery coaching intervention and pilot testing of pragmatic trial protocols within the context of Indiana’s Opioid State Targeted Response plan. J Subst Abuse Treat. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C, Powell BJ, Dorsey CN, Clary AS, Boynton MH, Halko H (2017). Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implement Sci, 12(1), 108. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside LK, Darnell D, Jackson K, Wang J, Russo J, Donovan DM, & Zatzick DF (2017). Collaborative care from the emergency department for injured patients with prescription drug misuse: An open feasibility study. J Subst Abuse Treat, 82(Supplement C), 12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside LK, Vrablik MC, Russo J, Bulger EM, Nehra D, Moloney K, & Zatzick DF (2021). Leveraging a health information exchange to examine the accuracy of selfreport emergency department utilization data among hospitalized injury survivors. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open, 6(1), e000550. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2020-000550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yale Department of Emergency Medicine. ED-Initiated Buprenorphine. Retrieved from https://medicine.yale.edu/edbup/

- Zatzick D, Donovan DM, Jurkovich G, Gentilello L, Dunn C, Russo J, Wang J, Zatzick DD, Love J, McFadden C, Rivara FP (2014). Disseminating alcohol screening and brief intervention at trauma centers: A policy-relevant cluster randomized effectiveness trial. Addiction, 109(5), 754–765. doi: 10.1111/add.12492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]