Abstract

Background: Transnational tobacco companies (TTCs) have a well-established presence in Southeast Asia and are now targeting other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), especially Africa. While the tobacco industry’s tactics in Southeast Asia are well documented, no study has systematically reviewed these tactics to inform tobacco control policies and movements in Africa, where the tobacco epidemic is spreading.

Methods: We conducted a systematic literature review of articles that describe tobacco industry tactics in Southeast Asia, which includes Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Myanmar, East Timor, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos, and Brunei. After screening 512 articles, we gathered and analysed data from 134 articles which met our final inclusion criteria.

Results: Tobacco transnationals gained dominance in Southeast Asian markets by positioning themselves as good corporate citizens with corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives, promoting the industry as a pillar of, and partner for, economic growth. Tobacco transnationals also formed strategic sectoral alliances and reinforced their political ties to delay the implementation of regulations and lobby for weaker tobacco control. Where governments resisted the transnationals’ attempts to enter a market, they used litigation and deceptive tactics including smuggling to pressure governments to open markets, and tarnished the reputation of public health organizations. The tobacco industry undermined tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship (TAPS) regulations through a broad range of direct and indirect marketing tactics.

Conclusion: The experience of Southeast Asia with tobacco transnationals show that, beyond highlighting the public health benefits, underscoring the economic benefits of tobacco control might be a more compelling argument for governments in LMICs to prioritise tobacco control. Given the tobacco industry’s widespread use of litigation, LMICs need more legal support and resources to counter industry litigations. LMICs should also prioritize measures to protect health policy from the vested interests of the tobacco industry, and to close regulatory loopholes in tobacco marketing restrictions.

Keywords: Tobacco Industry Tactics, Transnational Tobacco, Southeast Asia, Tobacco Control, LMICs

Background

In Southeast Asia, smoking rates are among the highest globally with an average male smoking prevalence of 42%. 1 As of 2017, the region had 122 million adult smokers. 2 Southeast Asia also remains a lucrative market for transnational tobacco companies (TTCs), 3 which have operations in multiple countries to manufacture, distribute and market their products, often using aggressive marketing and lobbying tactics.

While Southeast Asia now has a well-established tobacco epidemic, TTCs have, in more recent decades, also pursued other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). 4 TTCs used sophisticated marketing tactics, smuggling, aggressive lobbying, and trade threats to open up and gain dominance in LMICs in Eastern Europe, 5-7 Latin America, 8-10 and the Middle East. 11 As a result, TTCs managed to gain significant political and economic clout, influence policy to their advantage, and increase smoking rates in these regions. Consequently, smoking is no longer an epidemic restricted only to high-income countries (HICs). Eighty per cent of the world’s smokers now live in LMICs, where the burden of tobacco-related diseases hit the hardest by the substantial healthcare costs and lost human capital. 12

Africa in particular holds much promise for tobacco transnationals. Amid ageing populations and slowing population growth in many parts of the world, including Southeast Asia, 13 Africa’s population is growing, 14 and by 2050 it is predicted that over 33% of the world’s youths will be in sub-Saharan Africa. 15 Cigarette demand grew by 44% between 1990 and 2012 in 22 African nations representing 80% of the region’s population. 16 While smoking prevalence is projected to decrease in most world regions, it is expected to increase from 12.8% to 18.1% in the African region by 2025 amid slow implementation and ineffective enforcement, industry interference, and inadequate resources for tobacco control. 17-19

Although the tobacco epidemic started in ‘Western’ HICs, 20 TTCs have adapted their tactics to target LMICs. 4 LMICs generally have weak monitoring of tobacco use and policies, less resources to resist industry litigations, and are more susceptible to political corruption, trade pressure, exploitation of political instability and the industry’s promises of economic prosperity. 4,21-26 TTCs’ tactics have also evolved since they dominated North American and West European markets in the 1930s, focusing increasingly on trade litigation and more innovative marketing strategies to circumvent advertising regulations. 4,27-30

In preventing new tobacco epidemics in Africa, it is important to look to the experiences of other LMIC regions, such as Southeast Asia, where tobacco transnationals became established in more recent decades. Much like Africa now, Southeast Asia was a prime target for TTCs in the 1980s, 31,32 when its population was growing with affluence, 33,34 and when governments opened up to international trade in their pursuit of economic growth. 35 While the tobacco industry’s tactics in Southeast Asia are well-documented, no study has systematically reviewed these tactics.

The aim of this study was to systematically review literature that describes tobacco industry tactics in Southeast Asian countries, to inform tobacco control policies and movements in other LMICs, especially in the African region, where the tobacco epidemic is spreading. We defined ‘tobacco industry tactic’ as any tactic, direct or indirect, to increase tobacco sales. We defined ‘Southeast Asia’ as the geographical region that includes Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Myanmar, East Timor, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos, and Brunei.

Methods

Search Strategy

In March 2019, we searched databases for academic literature (eg, PubMed, Embase) and grey literature (eg, OAIster, Business Source Premier, publications of regional NGOs) using the search strings: “tobacco industry” AND (Asia OR ASEAN OR Singapore OR Indonesia OR Malaysia OR Philippines OR Myanmar OR Burma OR Timor OR Thailand OR Cambodia OR Vietnam OR Laos OR Brunei).

Selection Criteria

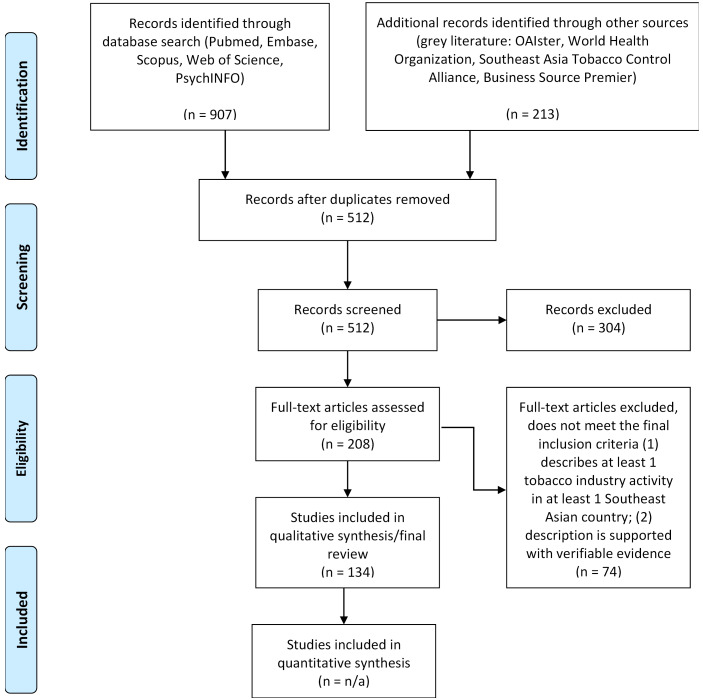

A total of 1120 articles were included for the initial abstract screening (Figure 1). 512 articles met our initial inclusion criteria: (1) available in English, (2) covers any of the Southeast Asian countries, and (3) mentions tobacco or tobacco industry. After reading the full text of these 512 articles, 134 articles from 1983 to 2019 met our final inclusion criteria for synthesis: (1) describes at least one tobacco industry activity in at least one Southeast Asian country; (2) activity is clearly described and supported with verifiable evidence. This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement.

Figure 1.

Study Selection Flowchart, Systematic Review of Tobacco Industry Tactics in Southeast Asia.

Data Extraction

Data extraction was undertaken by the first and second authors using a standard template which included: (1) detailed information about tobacco industry strategy in Southeast Asia, and; (2) tagged references on countries covered, year or time period of the industry activity, tobacco industry tactic, arguments or issues (see Protocol, Supplementary file 1).

Quality Assessment

The data extracted was then reviewed by the third author to check that all inclusion criteria were met and to agree on the categorization of industry tactics. All differences were discussed between all authors until agreement was reached.

Data Analysis

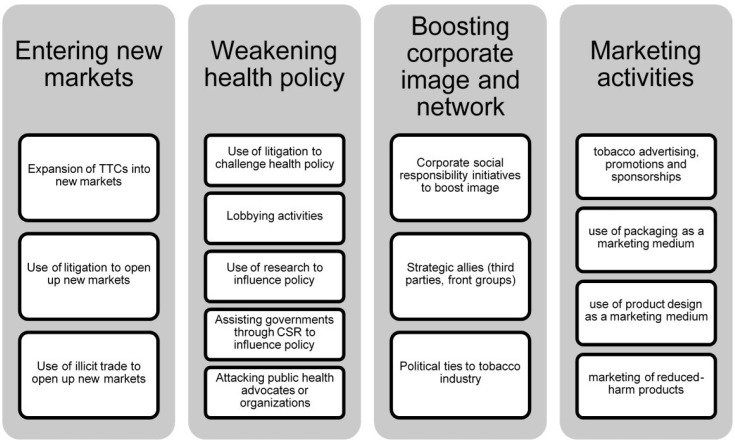

We used an inductive coding method. We identified codes relating to tobacco industry activities based on our data, and subsequently refined and categorized these codes in an iterative process between all authors. Any discrepancies were resolved via discussions between all authors until agreement was reached. Thirteen subcategories relating to four broader themes emerged from our data (Figure 2). The data from the articles were then synthesized in a narrative.

Figure 2.

Tobacco Industry Tactics in Southeast Asia. Abbreviations: TTCs, transnational tobacco companies; CSR, corporate social responsibility.

Results

Entering New Markets

Expansion of Transnational Tobacco Companies Into New Markets

TTCs British American Tobacco (BAT), Imperial Tobacco, Philip Morris International (PMI) and Japan Tobacco International (JTI) started aggressively pursuing new Southeast Asian markets in the 1980s and 1990s, after tobacco consumption started dropping in HICs. 36,37 In the countries with free port status (Singapore, the Philippines), TTCs already had well-established markets, while in other Southeast Asian countries, the industry started to dominate markets after the countries opened up trade. In Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam, the tobacco industry was state-owned, 38 while Indonesia, Myanmar, and the Philippines had well-established domestic tobacco industries before transnationals entered. 39-42

TTCs penetrated Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Myanmar, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia through joint ventures, investments, mergers or licensing agreements with local tobacco companies, state-owned industries or governments. This gave TTCs financial and political leverage over tobacco control policies, led to domestic-transnational alliances to form a unified industry lobby, and provided them with direct links to trade, industry and finance ministries (Table 1). 36,43-47

Table 1. Joint Ventures, Investments, Mergers and Licensing Agreements of Tobacco Transnationals in Southeast Asia.

| Country | Transnational | Local Entity | Details | Source |

| Laos | Imperial Brands (formerly Imperial Tobacco) | Lao Government | Joint venture to form Lao Tobacco Ltd through Coralma Intl, S3T | 2 |

| Cambodia | BAT | Cambodian Tobacco Company | Joint venture in 1996 between BAT-Singapura United Trading and Cambodian Tobacco Company (Kong Triv) | 49 |

| Vietnam | BAT | Vinataba | Joint venture in 2001 | 45 |

| Myanmar | BAT | Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings | Joint venture between Rothmans of Pall Mall Myanmar and Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings (military regime’s economic arm) until 2004 | 38 |

| BAT | IMU (Sein Wut Hmon Group) | Majority stake ($50m) in joint venture in 2014 | 50 | |

| Philippines | RJ Reynolds | Fortune Tobacco Company | Licensing agreement in 1974 | 42 |

| PMI |

La Suerte Cigar and Cigarette Company Fortune Tobacco Company |

Licensing agreement in 1955-2002 Merger to form PMFTC, $20m investment in 2010 |

2,42,51 | |

| JTI | Mighty Corporation | $936m investment in 2017 | 2 | |

| Indonesia | PMI | Sampoerna | $5.2b investment (98% share) in 2005 | 2,46,52 |

| BAT | Bentoel | Acquisition for $494m (99.7% share) in 2009 | 2,51,52 | |

| JTI | Karyadibya Mahardhika, Surya Mustika Nusantara | Acquisition for $677b in 2017 | 2 | |

| Malaysia | PMI | Philip Morris (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd | $40m investment in 2005 | 51 |

Abbreviations: BAT, British American Tobacco; PMI, Philip Morris International; JTI, Japan Tobacco International.

Notably, the agreement between Imperial and the Lao Government’s Lao Tobacco Ltd 2 resulted in a tax agreement which barred the Lao government from increasing tobacco taxes from 2001 to 2026. 38,48 The joint venture between BAT and Vinataba, Vietnam’s state-owned tobacco industry, gave BAT direct links to the Ministry of Trade and Industry and Ministry of Finance. 44,45

In Indonesia, where transnationals faced strong competition from domestic kretek manufacturers, 46 transnationals leveraged on the kretek industry’s political influence by forming lobby alliances with them to counter regulations. 47 A decade later, after the transnationals had gained more political influence, they started acquiring domestic industry shares.

Use of Litigation to Open up New Markets

Thailand, which had a government-owned tobacco monopoly (Thailand Tobacco Monopoly (TTM)) since 1939, was resistant to TTCs. 53 TTCs responded with litigation against Thailand and lobbying through an industry alliance (US Cigarette Export Association) with the US Trade Representative, Thailand’s Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Commerce, pro-entry politicians and Thai exporters to open up the tobacco market using Section 301 of the 1974 US Trade Act. 54 In 1989, the US Trade Representative referred its dispute to the World Trade Organization and in 1990, forced Thailand to lift its tobacco import restrictions. 32,36,55,56 TTCs then ‘localized’ by forming alliances and business relationships with politically influential Thais. 56

Use of Illicit Trade to Open up New Markets

BAT engaged in illicit trade operations while negotiating a joint venture with Vinataba, Vietnam’s state-owned tobacco industry, to create local demand and leverage access to the market after Vietnam’s import ban on cigarettes in 1990. 45,49 BAT’s joint venture in Cambodia was crucial for its smuggling operations into Vietnam, due to its proximity and manufacturing facilities. 49,57,58 After Vietnam’s market opened up, BAT controlled the prices of locally produced and smuggled cigarettes to aid the transition from illicit trade to legal sales. 45,57 BAT also smuggled its brands into Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, and the Philippines, 57,59,60 and used its Singapore-based distribution partner, Singapura United Tobacco Limited, to oversee smuggling in Southeast Asia. 57,61 BAT also used legal trade flows as cover for its smuggling operations in the region, blurring the line between legal and illegal operations through ‘partial duty paid’ products and ‘duty free’ leakage. 57

Weakening Health Policy

Use of Litigation to Challenge Health Policy

TTCs launched legal challenges against governments based on national laws, trade law and international agreements to undermine health policies and intimidate governments, both at the national and local levels, in Southeast Asia (Table 2). 62,63 There were 39 such legal challenges in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand documented in the literature. While most of these lawsuits were against national governments, the tobacco industry also used litigation to intimidate local governments such as Balanga, a small city in the Philippines.

Table 2. Tobacco Industry-Led Lawsuits Against Governments in Southeast Asia.

| Country | Number/Type of Lawsuit | Details | Sources |

| Indonesia | 13 vs. National government | To challenge Health Law 36/2009 on addictive nature of cigarettes, graphic health warnings, smokefree legislation | 2,64,65 |

| 1 vs. Jakarta | To challenge smokefree legislation | 2 | |

| 1 vs. Bogor | To challenge smokefree legislation | 2 | |

| Malaysia | 3 vs. Health Ministry | To challenge price increases, requirement of Health Ministry approval for cigarette pricing | 2,64 |

| Philippines | 11 vs. National government | To challenge graphic health warnings, authority to regulate tobacco products, marketing restrictions | 2,63,64,66 |

| 2 vs. Balanga | To challenge the Tobacco-Free Generation law and other sale restrictions | 67 | |

| Thailand | 8 vs. National government | To challenge graphic health warnings and other tobacco control measures | 2,62,64 |

Lobbying Activities

Tobacco industry front groups and alliances argued that the industry contributed to economic development and employment in the region, especially for tobacco farmers. 49,52,66,68-71 The industry formed alliances to strengthen their lobby, 47,52,66,72,73 which typically consisted of TTCs and domestic tobacco companies, the media, tobacco farmers, local governments, ministries, and influential locals. 47,56,73,74 These alliances resulted in weaker marketing regulations, 66 or where regulations could not be avoided, delays in their implementation. 62-64,70,75-77

In Indonesia, tobacco lobbyists successfully blocked Indonesia’s accession to the World Health Organization (WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). 47,52,70 Through Indonesian associations, tobacco companies lobbied for the Indonesian government’s ‘Roadmap of Tobacco Products Industry and Excise Policy 2007-2020,’ which called for a 12% increase in annual cigarette production up to 2020 and tobacco industry participation in policy-making. 52 In 2009, industry front groups lobbied against a proposed clause in the Indonesian National Health Bill that would identify tobacco as an addictive substance, which was later removed in the short period after the bill was passed by Parliament and before the President signed the bill into law. 73,78

The majority of TCCs’ lobbying documented in Southeast Asia were against tobacco taxes and graphic health warnings. TTCs blocked or weakened tobacco taxes by publishing resource manuals not aligned with FCTC guidelines, 79-81 lobbying for ad valorem taxes, 82 meeting legislators, 68 mounting media campaigns, 83 and bribing government officials. 42 TTCs spent decades lobbying against graphic health warnings in Singapore, 63 Malaysia, 69 Cambodia, 63 and the Philippines. 42 In Malaysia, these efforts resulted in weaker regulations from 1970 to 1995. 69 In the Philippines, the tobacco industry was able to delay the implementation of graphic health warnings for three decades. 42

Use of Research to Influence Policy

TTCs also used researchers in Southeast Asia to substantiate their lobby, particularly against smokefree legislation and tobacco taxes (Table 3). TTCs launched initiatives like the International Environmental Tobacco Smoke Consultants Program (1989-1999) and the Asian Regional Tobacco Industry Science Team (1996) to counter smoke free measures by obscuring the effects of secondhand smoke compared to outdoor pollution and promoting ineffective ventilation technologies. 84-86 TTCs recruited consultant researchers from Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and the Philippines and were compensated with consultancy fees via Covington and Burling, a Washington DC-based law firm. 85 TTCs encouraged the consultants to solicit research assignments from government bodies to boost the group’s credibility, and amplified their publicity with media tours, editorial columns, and national and international conferences. 42 The consultants attended at least 34 conferences from 1988 to 1990 and developed a close relationship with the Asian Association of Occupational Health. 84

Table 3. Researchers in Southeast Asia Funded by the Tobacco Industry 42,84,87 .

| Country | Name | Research Area or Affiliation at Time of Involvement |

| Philippines | Ben Ferer | Architecture |

| Luis M. Ferrer | Director of Health Infrastructure Service, Ministry of Health | |

| Benito Reverente | Occupational Health/Pulmonary Medicine; Member of WHO Occupational Health Panel | |

| Camilo Roa Jr | Pulmonary medicine | |

| Lina Somera | Occupational health and biostatistics; Head of Public Health at University of the Philippines | |

| Domingo Aviado | Pharmacology | |

| Daniel A Witt | President, International Tax and Investment Center (Philippines, Thailand, Myanmar) | |

| Singapore | Choong Nam Ong | Occupational Hygienist, National University Hospital |

| Adrian Cooper | CEO, Oxford Economics (Singapore office) | |

| Malaysia | Krishna Ramphal | Department of Community Medicine, National University of Malaysia |

| Thailand | Malinee Wongphanich | President, Asian Association for Occupational Health |

| Mathuros Ruchirawat | Vice President for Research, Chulabhorn Research Institute; Associate Professor of Pharmacology, Mahidol University |

Abbreviations: WHO, World Health Organization; CEO, chief executive officer.

PMI took advantage of its links with scientists at Thailand’s Chulabhorn Research Institute, a WHO Collaborating Centre with ties to the Thai Royal family, to challenge Thailand’s smokefree legislation and the 1992 Tobacco Products Control Act. 56,87 Moreover, tobacco transnationals co-opted scientists from various disciplines, some of whom were unaware of the tobacco industry associations, to lobby against smokefree legislations. 56,87 PMI also wielded its ties with the Philippines’ Department of Science and Technology to offer research funds to a university teaching hospital in Bicol, Philippines, but was blocked by the Department of Health. 88,89

Through industry-funded research, TTCs lobbied against tobacco taxes in Southeast Asia using illicit trade as an argument. 42,45,56,61,70,80,82,90-92 An industry-funded report by the International Tax and Investment Center (ITIC) and Oxford Economics, the “Asia-14 Illicit Tobacco Indicator 2013,” overestimated illicit trade in the region and advised governments to avoid ‘excessive’ taxation to prevent illicit trade. 76,79-82,91,93 ITIC was funded by tobacco companies and Board of Directors included members from PMI, Imperial, JTI, and BAT. 82 The report’s authors had also previously been employed in the tobacco industry. 82 TTCs ensured that the report received widespread media coverage in the region, 82,91 and used it to lobby against tobacco taxes 61,82 and to offer ‘technical assistance’ to governments on excise tax reform. 76,79,81,93

Assisting Governments Through Corporate Social Responsibility to Influence Policy

TTCs set up anti-smuggling corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives to counter tobacco taxes in Southeast Asia, in the form of training and assistance to governments in anti-smuggling raids, 45,64,68,76,77,80,93-95 contributions to national and international anti-smuggling agencies including Interpol, 45,64,70,77,81,93 and partnerships with governments, trade and industry ministries, justice ministries and customs departments on anti-smuggling issues in the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Malaysia. 45,68,76,80,81,93,94,96 TTCs’ collaboration with Vietnam’s Ministry of Trade and Industry resulted in 50% of Vietnam’s tobacco control fund being allocated to control smuggling. 77,95 TTCs also proposed industry-developed track and trace systems to governments, particularly Codentify, a ‘digital tax verification’ system to replace tax stamps and fiscal markers. 97

TTCs promoted voluntary regulations in Southeast Asia to dilute regulations on tobacco marketing and ingredient disclosure, 50,71 and to supersede the FCTC. 98 TTCs also promoted their own CSR programmes to prevent youth smoking in Thailand, Malaysia and the Philippines to improve their image and provide opportunities for engagement with retailers and government officials. 69,71,88,98-100 TTCs espoused the concept of ‘smoker accommodation’ to undermine smokefree laws, by donating ashtrays to public places, 101 and by funding the construction of airport smoking rooms. 94

Attacking Public Health Advocates or Organisations

TTCs systematically identified public health advocates and health promotion organisations in Southeast Asia, monitored their publications and finances, and in some cases, attacked their reputation to limit their influence and credibility. 102 In Indonesia, TTCs set up a billboard with the names and photos of public health advocates, branding them as ‘enemies,’ 65 and in Thailand, TTCs pressured the Thai government to investigate and restructure the Thai Health Promotion Board. 76,81,93

Boosting Corporate Image and Network

Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives to Boost Image

From 2010 to 2018, TTCs spent over $80 million on CSR initiatives in Southeast Asia, 2,103,104 much of which was spent on promoting these initiatives to boost corporate image. 105 These CSR initiatives were either funded directly or channelled through foundations or industry-related associations (Table 4), and usually focused on human rights, the environment, employee welfare, education, social welfare, poverty, disaster relief, or arts and culture. 2,42,68,71,74,77,88,89,93,99,103-111 TTCs used these initiatives to gain publicity, 110 promote their products, 99,112 enhance their network and image with governments, 76,77,81,95,105,111,113 local organizations, 110 and international organizations (UNDP, ILO, UNICEF), 103,110,114 and to engage tobacco farmers in pro-tobacco lobbying. 71,106,108,115,116

Table 4. Foundations or Associations Used to Conduct CSR Activities in Southeast Asia.

| Foundation or Association | CSR Activities | Sources |

| BAT Malaysia Foundation | Scholarships, training, schools, community development | 52,88,110,112,116 |

| JTI Foundation | Disaster relief, prevention of human trafficking | 110,117 |

| KT&G Social Welfare Foundation | Disaster relief | 110,117 |

| Fundacion Altadis (Imperial) | Poverty relief, food security, environmental sustainability | 110,118 |

| American Chamber of Commerce Foundations | Education, poverty relief, disaster relief, environment | 81,110,119 |

| Jaime Ongpin Foundation | Environment, community development | 110,120,121 |

| Putera Sampoerna Foundation | Scholarships, training, schools, community development | 52,88,110,112,116 |

| Philip Morris Arts Foundation Thailand | ASEAN Art Awards | 88 |

| Tan Yan Kee Foundation (Fortune) | Not specified | 110 |

| Wong Chu King Foundation (Mighty) | Religious activities | 93,110 |

| Djarum Foundation | Not specified | 110 |

| KT&G Sunny Korea Welfare Foundation | Child welfare | 117 |

| PMI Thailand Population and Community Development Association | Scholarships, training, community development | 110 |

| PMI Thailand Chiangrai and Phayao Tobacco Curer, Planter and Seller Association | Scholarships, training, community development | 110 |

| PMI Thai Tobacco Growers, Curers and Dealers Association | Scholarships, training, community development | 107,110 |

| Eliminating Child Labour in Growing Tobacco Foundation | Child labour prevention | 103,114 |

Abbreviations: BAT, British American Tobacco; PMI, Philip Morris International; JTI, Japan Tobacco International; CSR, corporate social responsibility.

TTCs regularly conducted CSR activities for tobacco workers but failed to improve their lives and well-being. In Cambodia, Indonesia and the Philippines, tobacco farmers entered into loan agreements with tobacco companies, trapping them into debt cycles and forcing them to sell tobacco leaf at a price set by manufacturers. 90,122 In Malaysia, despite tobacco industry assistance and subsidies, tobacco farmers still bore the cost of tackling crop diseases and adverse weather conditions. 115 In Vietnam, tobacco farmers were found to be earning less or only marginally more than non-tobacco farmers, and had more health complaints. 123 In Indonesia, PMI subsidiary Sampoerna ignored complaints of mistreatment, low pay, poor living conditions, and unsafe working environments from its factory workers. 116 Moreover, TTCs also profited from child labour in Southeast Asia, 103,105,110 while their CSR initiatives to combat child labour in the region had little impact. 103,114

Strategic Allies (Third Parties, Front Groups)

TTCs funded or partnered with front groups and third parties in Southeast Asia to gain access to governments, undermine tobacco regulations and boost their corporate image (Table 5).

Table 5. Front Groups and Third Parties Documented to Have Received Tobacco Industry Funding for Operations in Southeast Asia.

| Organization | Sources |

| Formal business networks | |

| International Business Chamber Cambodia | 68 |

| Cambodia Chamber of Commerce | 68 |

| Cambodian Federation of Employers and Business Associations | 68 |

| American Chamber of Commerce | 77,80,81,95,119 |

| Associations/alliances | |

| Gabungan Pengusaha Pabrik Rokok Indonesia (kretek manufacturers association) | 52 |

| Gabungan Produsen Rokok Putih Indonesia (white cigarette manufacturers association) | 52 65 |

| Alliance of Indonesia Tobacco Society | 65 |

| Indonesia Tobacco Society Movement (Gemati) | 65 |

| Central Java Regional Representatives Council | 83 |

| District Legislative Councils Association | 83 |

| Indonesian Tobacco Farmers’ Association | 83 |

| International Tobacco Growers Association | 2,64,124,125 |

| Thai Tobacco Trade Association | 70 |

| Tobacco Retailer Association (Thailand) | 126 |

| Malaysia Coffee Shop Association | 73 |

| Malaysia-Singapore Coffee Shop Proprietors General Association | 73,127 |

| International agencies | |

| International Union of Food | 103 |

| International Labour Organization | 103,73 |

| UNICEF | 103,73 |

| Interpol | 70,97 |

| Think tanks | |

| Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs | 77 |

| International Tax and Investment Center | 76,81,93,128 |

Abbreviation: UNICEF, The United Nations Children’s Fund.

Political Ties to Tobacco Industry

TTCs forged extensive ties with political and business elites in Southeast Asia (Table 6), especially in Indonesia, the Philippines, 42 Cambodia, 63,68 and Malaysia. 115

Table 6. Political and Business Elites in Southeast Asia Reported to Have Conflicts of Interest With the Tobacco Industry.

| Individual | Conflict of Interest | Sources |

| Indonesia | ||

| President Suharto’s brother | Joint venture with Gudang Garam founder Surya Wonowidjojo | 47 |

| President Suharto’s youngest son | Founded BPCC (Clove Support and Trading Board) clove monopoly in 1990 | 47,113,129,130,131 |

| President Suharto’s cousin | Partnership with Australian Rothmans Holdings Ltd | 113,129 |

| President Suharto’s second son; owner of Indovision | Star TV Indonesia, which runs Indovision, owned by Phillip Morris director Rupert Murdoch | 113,129 |

| Raden Bagus Permana Agung Dradjattun, Expert for Ministry of Finance | Independent Commissioner of Sampoerna | 76,77,80,81,95 |

| Former Director-General of Customs and Excise | Commissioner of Sampoerna | 76,77,80,81,95 |

| Eddy Abdurrahman, Former Director-General of Customs and Excise in Ministry of Finance | BAT/Bentoel Independent Commissioner on BAT’s Board and Chairman of BAT/Bentoel Audit Committee | 76,77,80,81,95 |

| Philippines | ||

| Estelito Mendoza, Former Solicitor General | Legal counsel to Lucio Tan (Chairman of Fortune Tobacco) | 81 |

| Edilberto Adan, Former Military Official | Director and President of Mighty Corporation | 81 |

| Oscar Barrientos, Former Judge | Executive Vice President of Mighty Corporation | 81 |

| Members of the Inter-Agency Committee on Tobacco | Employed in Philippine Tobacco Institute | 80,81,96 |

| Cambodia | ||

| Senator | Chairman of BAT Cambodia | 77 |

| Laos | ||

| Officials in Ministry of Finance | Members of the Board Management of Lao Tobacco Ltd | 81 |

| Officials in Ministry of Industry and Commerce | Members of the Board Management of Lao Tobacco Ltd | 81 |

| Retired Vice Director General of Enterprise Department | Board member of Lao Tobacco Ltd | 81 |

| Malaysia | ||

| Tan Sri Datuk Dr Rebecca Fatima Sta Maria, Secretary-General of the Ministry of International Trade and Industry | Council member of Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs, a tobacco industry-funded think tank | 77 |

| Tan Sri Datuk Abu Talib bin Othman, Former Attorney General | Chairman of BAT Malaysia | 94-96,115 |

| Tan Sri Dato’ Seri Dr Aseh, Former Secretary General of the Ministry of Home Affairs | Chairman of BAT Malaysia | 94-96 |

| Hon Dato’ Sri Mohamed Khalid Bin Hj Yusef, former Director General of Customs | Senior Adviser to ITIC | 80 |

| Tunku Tan Sri Mohamed bin Tunku Besar Burhanuddin, Former Chief Secretary | First chairman of Rothmans of Pall Mall (later BAT Malaysia) | 115 |

| Brother of Prime Minister, Dato’ Sri Mohamed Najib Abdul Razak | Non-executive director on BAT Malaysia’s board | 115 |

| Datuk Mohamad bin Fateh Din, Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission | Chairman of BAT Malaysia | 115 |

| Datuk Zainun Aishah binti, Malaysian Industrial Development Agency | Board member of BAT Malaysia | 115 |

| Tan Sri Kamarul bin Mohamed Yassin, Former Senator | Board member of BAT Malaysia | 115 |

| Thailand | ||

| Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Interior | TTM board member | 76,81,94,96 |

| Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office | Owner of a local tobacco leaf business | 76,81,94,96 |

| Former Lieutenant General | TTM Chairman | 76 |

| Vietnam | ||

| Ha Quang Hoa, Former Deputy Director in Ministry of Trade and Industry | Vice Director at VINATABA | 81 |

| Vice Director in Ministry of Trade and Industry | Board member at VINATABA | 81 |

| Vu Van Cuong, Senior Member of Communist Party | Chairman of the Board of VINATABA | 81 |

| Ha Quang Hoa, Former Deputy Director in Ministry of Trade and Industry | Vice Director at VINATABA | 81 |

Abbreviations: BPCC, Badan Penyangga dan Pemasaran Cenkgeh; BAT, British American Tobacco; ITIC, International Tax and Investment Center; TTM, Thailand Tobacco Monopoly.

Marketing Activities

Tobacco Advertising, Promotions and Sponsorships

TTCs’ marketing tactics varied widely in Southeast Asia, depending on the strength and enforcement of regulations on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship (TAPS).

In Indonesia, TTCs exploited the lack of marketing restrictions with heavy direct, outdoor, and point-of-sale advertising. 64,124,132 In restricted markets that still allowed point-of-sale advertising (eg, the Philippines, Vietnam), TTCs invested heavily in point-of-sale advertising, including entire shops, buildings and cigarette booths painted with brand colours, illuminated brand advertisements and branded parasols, and the use of promotional girls to sell cigarettes. 89,109,132-139 In countries with weakly enforced marketing restrictions, TTCs violated marketing regulations with illegal installation of point-of-sale displays, vending machines, and promotional items. TTCs encouraged retailers to violate regulations through regular engagements, including frequent visits, free merchandise, rewards for meeting sales targets, and by hosting annual dinners and musical events for retailers. 64,111,124,127,132,135,140 After Thailand’s tobacco display ban, TTCs circumvented restrictions with mobile cigarette shops and transparent point-of-sale displays showing brand logos and colours. 126

TTCs utilized trademark diversification 50,56,99,141-149 by using tobacco brands on non-tobacco products such as lighters, 143 wine coolers, 142 luxury products, clothing, or travel agencies and holiday themes. 99,148,149 Tobacco companies also operated trademark diversification businesses, notably in Malaysia, including BAT’s ‘World Investment Company’ (Benson and Hedges Bistros, Kent Travel), Brown and Williamson’s ‘Diversification International Products’ (Kent Leisure Holidays), PMI’s ‘International Trademark’ (Marlboro Classics) and R.J. Reynolds’ ‘Worldwide Brands’ (Camel Stores). 141

TTCs also invested heavily in sponsorship of popular sports, music concerts, movies, fashion events and the arts, to associate their products with youth, popular culture, adventure and leisure. Notable arts sponsorships in the region include Philip Morris’ ASEAN Art Awards 150 and Sampoerna’s SoundrenAline concerts in Indonesia. 151 In Indonesia, which has no restrictions on tobacco industry sponsorship, an estimated 85% of Indonesian youths had attended at least one tobacco-sponsored event in 2007. 52 TTCs also sponsored professional football in Vietnam, 136 the Philippines’ annual Marlboro Tour (cycling), 152 and Malaysia’s Formula 1 Grand Prix, 148,153 and 2002 FIFA World Cup. 154 Sports sponsorships functioned as cross-border advertising to reach countries with stricter advertising bans (Thailand, Singapore). 111,155,156 Sports sponsorships also resulted in the delay of some tobacco control measures, such as Malaysia’s 5-year freeze on tobacco taxes in exchange for BAT’s sponsorship of the 1998 Commonwealth Games. 73,141

More recently, TTCs have used social media platforms (eg, Facebook, Flickr, Instagram) to promote their brands and sponsored events in Southeast Asia. 157 Despite Malaysia’s ban on internet advertising, BAT, PMI and JTI have all used social media, particularly Facebook, to promote their products. 64,124 Sampoerna used Instagram to promote its SoundrenAline concerts with brand hashtags, and used its ‘Go Ahead People’ art website to collect user data for marketing through social media account registration, promotions, and creative opportunities in music, fashion, photography and arts. 151

Use of Packaging as a Marketing Medium

Tobacco companies used pack colours and designs to differentiate brand variants, create a false impression of reduced harm, and replace banned descriptors. 134 Companies have used a variety of innovative pack designs to promote their brands in Southeast Asia, such as wallet packs, twin- or multi-packs, promotional packs, expanded size packs, lipstick packs, 89,134,158,159 glow in the dark packs, transparent packs, 142 and packs with rounded corners. 160,161 Tobacco companies also used pack designs to dilute or cover up graphic health warnings. 89,99,134,159,162 In some countries, tobacco companies did not comply to graphic health warnings, 65,77,162,163 and misled retailers about the enforcement start date to delay impact of the graphic health warning regulations. 162

To encourage youth smoking in Southeast Asia, tobacco companies sold cigarettes in smaller packs of 5, 99,158,164 10, and 14. 99,142 The sale of single sticks, sometimes illegally, was also reported to be common in the region. 90,99,158

Use of Product Design as a Marketing Medium

Tobacco companies carefully researched Southeast Asian youth to develop products to appeal to them, 42,100,147 notably cigarettes with novelties such as added flavours, flavour capsules, and product design novelties (sweetened tips, a dial to control menthol delivery). 89,100,117,147,161 To target health-conscious people in Malaysia and Singapore, tobacco companies marketed their imported menthol, ‘light’ and ‘mild’ brands with imagery, colours and messages that conveyed a lower health risk, despite knowing that these products were just as harmful as regular brands. 47,90,142,147 Companies also used filters, such as charcoal filters or white-coloured filters, to convey a lower health risk, and used descriptors alluding to cutting-edge technology (eg, ‘Triple Filter Charcoal’) when descriptors such as ‘light’ and ‘mild’ were banned. 161 Tobacco companies also targeted women in the region with light, menthol-flavoured and ‘slim’ brands. 42,52,117,130,138,147,150,165

Marketing of Reduced-Harm Products

Tobacco companies have aggressively marketed e-cigarettes in Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines with billboards, point of sale advertising, promotions, and online or temporary pop-up shops. E-liquids have been sold in a wide variety of flavours alongside other consumer products. Companies have provided little, if any information on the ingredients inside e-liquids or their safety, yet claim they are a safe alternative to tobacco. 166

Discussion

Our findings show that, in Southeast Asia, TTCs used arguments of economic growth and developed a good corporate image through CSR to forge ties with the local industry, policy-makers, researchers, political and economic elites, and key organizations to enter new markets and weaken tobacco policies. Where countries resisted, TTCs resorted to litigation and illicit trade. In countries with strong tobacco control movements, TTCs engaged in ‘smear’ campaigns against public health organizations. Our findings also highlight TTCs’ heavy use of point of sale advertising, sponsorships, social media and packaging to get around regulatory loopholes and create demand for their products in Southeast Asia, especially among youth.

As in Southeast Asia, TTCs regularly conduct CSR initiatives in Africa focusing on good employment practices, the environment, child welfare, 167 education, disaster relief, arts and culture, 168 and business development, 169 and provide ‘technical assistance’ on anti-smuggling measures to African governments. 167 TTCs have also provided funding to universities in South Africa. 168,170,171 In their lobbying efforts, TTCs use arguments of economic growth and good corporate citizenship as documented in Nigeria 172,173 and South Africa. 174 Our findings indicate that these activities are not intended to aid countries and unlikely to have a meaningful impact on their economic or social welfare. Rather they are a means to improve corporate image, gain access to policy-makers, lobby against health policies and gain dominance in new markets.

The experiences of Southeast Asia highlight the importance of protecting health policy in LMICs from the vested interests of the tobacco industry, in line with FCTC Article 5.3. 175 This is also evidenced in the contrasting examples of Singapore and Indonesia. Singapore, which follows strict internal policies in line with Article 5.3, 2 has the region’s most comprehensive tobacco policy and a daily smoking prevalence of 12.0%. 176 In contrast, Indonesia’s policy-makers have extensive ties with tobacco companies, and Indonesia has the region’s highest smoking rates 177 and weakest tobacco control measures. 2 The case of Indonesia also highlights the power of economic arguments, suggesting that arguments which emphasise the economic costs of the burden of tobacco, and benefits of tobacco control to economies and sustainable development, might be more persuasive to governments when pushing for tobacco control in LMICs. 178,179

Our study highlights the tobacco industry’s use of litigations to challenge tobacco control measures of Southeast Asian governments, both at the national and local level. This is consistent with other studies that illustrate the tobacco industry’s increasing reliance on litigation as an intimidation tactic (regulatory chilling) to dissuade governments, especially those with limited resources, from implementing health policies. 4 In the past decade, TTCs have threatened litigations against LMICs in Africa including Congo, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Togo, Gabon and Namibia, 180,181 and filed lawsuits, all of which TTCs lost, against governments in South Africa, Kenya and Uganda over their tobacco control laws. 182 Although the industry’s legal cases are often weak, and ultimately lost in courts, the costs of defending against these legal challenges can intimidate LMICs into lifting restrictions. 183,184 More resources to fight against tobacco industry litigations should be made available to LMICs.

Southeast Asia also illustrates the vast extent to which TTCs circumvent weak or poorly enforced TAPS restrictions with point of sale advertising, sponsorships, trademark diversification strategies, packaging, and the sale of ‘mini packs’ and single sticks to target youth. In other LMICs with partial or poorly enforced TAPS restrictions, similar tactics have been observed. 185,186 In Southeast Asia, only Thailand and Singapore have restricted all forms of direct and indirect TAPS, and have committed to plain packaging. 187 More Southeast Asian countries, and other LMICs, need to close the existing loopholes in their TAPS regulations.

Limitations

This study was based on published information of tobacco industry activities; thus, information may be limited in countries with less freedom of information, or where the topic has not been the subject of local research or media unless raised by regional or international civil society organisations. Our study included only English-language articles, although very few (less than five) were excluded based on this criterion. While the study offers a review of what is known about the tobacco industry’s tactics in Southeast Asia, the study does not delve deeper into what the industry has done beyond what is already published, or tobacco industry tactics in other regional, cultural or political contexts. Moreover, while East Timor was included in the study, we were not able to find studies on TTCs’ tactics in East Timor.

Conclusion

The tobacco industry’s tactics in Southeast Asia are being replicated in other LMIC regions, especially Africa. Tobacco business is detrimental to economies, yet in Southeast Asia, TTCs have used economic arguments to promote the tobacco industry and weaken tobacco control policies. Our findings suggest that policy-makers in LMICs need to recognize the burden of tobacco-related diseases on public health and the economy and institutionalize strong mechanisms to protect health policies from the vested interests of the tobacco industry. Policy-makers in LMICs also need to pay attention to civil society organizations that monitor the tobacco industry which help build the evidence of the tobacco industry’s tactics to weaken tobacco control measures. Policy-makers and tobacco control movements in LMICs also need better resources to fight industry counter-lobbying and litigation and should prioritise implementing FCTC-compliant regulations on all forms of tobacco marketing.

Ethical issues

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Disclaimers

The views of the authors in the study do not reflect the position of the institutions they are affiliated with.

Authors’ contributions

YV conceptualized and designed the protocol for the study. YV collected the initial list of references for systematic review. GGHA and GPPT acquired, analysed and interpreted the data. All authors contributed in the drafting and revising the manuscript and were all involved in the final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the study.

Authors’ affiliations

1Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore. 2Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore.

Supplementary files

Supplementary file 1. Protocol.

Citation: Amul GGH, Tan GPP, van der Eijk Y. A systematic review of tobacco industry tactics in Southeast Asia: lessons for other low- and middle-income regions. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2021;10(6):324–337. doi:10.34172/ijhpm.2020.97

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Smoking prevalence, males, Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.PRV.SMOK.MA?contextual=region&locations=BN-KH-MY-PH-MM-LA-SG-TH-VN-ID&most_recent_value_desc=true. Accessed February 26, 2020. Published 2016.

- 2. Tan YL, Dorotheo U. The Tobacco Control Atlas: ASEAN Region. Bangkok, Thailand: Southeast Asia Tob Control Alliance (SEATCA); 2018.

- 3.Mackay J, Ritthiphakdee B, Reddy KS. Tobacco Control in Asia. Lancet. 2013;381(9877):1581–1587. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60854-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilmore AB, Fooks G, Drope J, Bialous SA, Jackson RR. Exposing and addressing tobacco industry conduct in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2015;385(9972):1029–1043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60312-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilmore AB, McKee M. Tobacco and transition: an overview of industry investments, impact and influence in the former Soviet Union. Tob Control. 2004;13(2):136–142. doi: 10.1136/tc.2002.002667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szilágyi T, Chapman S. Hungry for Hungary: examples of tobacco industry’s expansionism. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2003;11(1):38–43. doi: 10.1007/bf02955964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilmore AB, McKee M. Moving East: how the transnational tobacco industry gained entry to the emerging markets of the former Soviet Union—part I: establishing cigarette imports. Tob Control. 2004;13(2):143–150. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.005108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crosbie E, Sebrié EM, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry success in Costa Rica: the importance of FCTC article 53. Salud Publica Mex. 2012;54(1):28–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holden C, Lee K, Fooks G, Wander N. The Impact of Regional Trade Integration on Firm Organization and Strategy. Bus Polit. 2010;12(4):3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crosbie E, Sosa P, Glantz SA. Defending strong tobacco packaging and labelling regulations in Uruguay: transnational Tobacco Control network versus Philip Morris International. Tob Control. 2018;27(2):185–194. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakkash R, Lee K. Smuggling as the “key to a combined market”: British American Tobacco in Lebanon. Tob Control. 2008;17(5):324–331. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.025254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization. Tobacco. Fact sheets 2019; https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco. Accessed February 21, 2020.

- 13. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects 2019 - Graphs and Profiles - Probabilistic Projections - Population-(Africa/Asia/Europe/Latin America and the Caribbean/Northern America/Oceania/South-Eastern Asia/Sub-Saharan Africa) - (total/age 0-24/age20-64). https://population.un.org/wpp/. Accessed May 27, 2020. Published 2019.

- 14. United Nations. Population. Global Issues 2019; https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/population/index.html. Accessed January 27, 2020.

- 15. Dews F. Charts of the Week: Africa’s changing demographics. Brookings Now 2019; https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brookings-now/2019/01/18/charts-of-the-week-africas-changing-demographics/. Accessed January 27, 2020.

- 16.Vellios N, Ross H, Perucic A-M. Trends in cigarette demand and supply in Africa. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Husain MJ, English LM, Ramanandraibe N. An overview of Tobacco Control and prevention policy status in Africa. Prev Med. 2016;91S:S16–S22. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. World Health Organization. The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: 10 Years of Implementation in the African Region. Geneva: WHO; 2015.

- 19. World Health Organization. WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco smoking 2000-2025 - First edition. Tobacco Free Initiative, Surveillance and monitoring 2015; https://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/surveillance/reportontrendstobaccosmoking/en/. Accessed January 27, 2020.

- 20. Brandt A. The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product that Defined America. New York, USA: Basic Books; 2009.

- 21. Drope J, Schluger NW, Cahn Z, et al. The Tobacco Atlas. Atlanta: American Cancer Society and Vital Strategies; 2018.

- 22.Gilmore AB, Collin J, McKee M. British American Tobacco’s erosion of health legislation in Uzbekistan. BMJ. 2006;332(7537):355–358. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7537.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samet J, Wipfli H, Perez-Padilla R, Yach D. Mexico and the tobacco industry: doing the wrong thing for the right reason? BMJ. 2006;332(7537):353–354. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7537.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tumwine J. Implementation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in Africa: current status of legislation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8:4312–4331. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8114312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boseley S. Revealed: how British American Tobacco exploited war zones to sell cigarettes. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/aug/18/british-american-tobacco-cigarettes-africa-middle-east. Accessed February 26, 2020. Published 2017.

- 26. Global Center for Good Governance in Tobacco Control. News in Brief - Tobacco Industry Interference. https://ggtc.world/2018/08/18/tobacco-industry-interference/. Accessed 26 February 2020, 2020. Published 2018.

- 27.Brandt AM. Inventing conflicts of interest: a history of tobacco industry tactics. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):63–71. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peeters S, Gilmore AB. Understanding the emergence of the tobacco industry’s use of the term tobacco harm reduction in order to inform public health policy. Tob Control. 2015;24(2):182–189. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilmore AB. Understanding the vector in order to plan effective tobacco control policies: an analysis of contemporary tobacco industry materials. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):119–126. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ulucanlar S, Fooks GJ, Gilmore AB. The Policy Dystopia Model: An Interpretive Analysis of Tobacco Industry Political Activity. PLOS Med. 2016;13(9):e1002125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chaloupka FJ, Laixuthai A. US Trade Policy and Cigarette Smoking in Asia. Natonal Bureau of Economic Research; April 1996.

- 32.Lee K, Eckhardt J. The globalisation strategies of five Asian tobacco companies: a comparative analysis and implications for global health governance. Global Public Health. 2017;12(3):367–379. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1273370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Worldometers.info. Regions in the world by population (2020), yearly population growth rates and population forecasts 2020; https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/population-by-region/. Accessed February 24, 2020.

- 34. The World Bank. Development indicators: GDP (Current US$), 1960-2018 - Singapore, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam 2020; https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=SG-BN-KH-LA-MY-MM-PH-TH-VN. Accessed February 25, 2020. Published 2020.

- 35. Bettcher DW, Subramaniam C, Guindon EG, et al. Confronting the tobacco epidemic in an era of trade liberalization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.

- 36.Levin M. US tobacco firms push eagerly into Asian market. Marketing News. 1991;25(2):2–14. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Easton A, Wallerstein C. Philippines fear they will be targeted by US tobacco industry. Lancet. 1997;350(9071):126–126. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)61841-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barraclough S, Morrow M. The political economy of tobacco and poverty alleviation in Southeast Asia: contradictions in the role of the state. Glob Health Promot. 2010;17(1 Suppl):40–50. doi: 10.1177/1757975909358243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arnez M. Tobacco and kretek: Indonesian drugs in historical change. ASEAS - Osterreichische Zeitschrift fur Sudostasienwissenschaften. 2009;2(1):49–69. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kyaing NN. Tobacco Economics in Myanmar. World Heatlh Organizaton and The World Bank; October 2003.

- 41. Cunnington G. Announcement filed with London Stock Exchange by British American Tobacco. US Securities and Exchange Commission website; 2003.

- 42.Alechnowicz K, Chapman S. The Philippine tobacco industry: “the strongest tobacco lobby in Asia”. Tob Control. 2004;13 Suppl 2:ii71–ii78. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee K, Eckhardt J. The globalisation strategies of five Asian tobacco companies: an analytical framework. Glob Public Health. 2017;12(3):269–280. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1251604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Higashi H, Khuong TA, Ngo AD, Hill PS. The development of Tobacco Harm Prevention Law in Vietnam: Stakeholder tensions over Tobacco Control legislation in a state owned industry. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2011;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee K, Kinh HV, Mackenzie R, Gilmore AB, Minh NT, Collin J. Gaining access to Vietnam’s cigarette market: British American Tobacco’s strategy to enter ‘a huge market which will become enormous. ’ Glob Public Health. 2008;3(1):1–25. doi: 10.1080/17441690701589789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Multinational Monitor. Philip Morris Comes to Indonesia: what does a company get for $5 billion? Multinational Monitor. Vol 26. Corporate Accountability Research; 2005:26-28.

- 47.Lawrence S, Collin J. Competing with kreteks: transnational tobacco companies, globalisation, and Indonesia. Tob Control. 2004;13 Suppl 2:ii96–ii103. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance. Imperial Tobacco targets ASEAN to sell more cheap cigarettes. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2018.

- 49.MacKenzie R, Collin J, Sopharo C, Sopheap Y. “Almost a role model of what we would like to do everywhere”: British American Tobacco in Cambodia. Tob Control. 2004;13 Suppl 2:ii112–ii117. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mudditt J. Myanmar’s tobacco industry ripe for growth. Tobacco Journal International. 2014;(2):36–36. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Drope J, Chavez JJ. Complexities at the intersection of Tobacco Control and trade liberalisation: evidence from Southeast Asia. Tob Control. 2015;24(e2):e128–136. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hurt RD, Ebbert JO, Achadi A, Croghan IT. Roadmap to a tobacco epidemic: transnational tobacco companies invade Indonesia. Tob Control. 2012;21(3):306–312. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.036814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.MacKenzie R, Ross H, Lee K. ‘Preparing ourselves to become an international organization’: Thailand Tobacco Monopoly’s regional and global strategies. Glob Public Health. 2017;12(3):351–366. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1273369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Frankel G. U.S. aided cigarette firms in conquests across Asia. The Washington Post. November 17, 1996. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/tobacco/stories/asia.htm. Accessed December 20, 2019.

- 55.Chen TTL, Winder AE. The Opium Wars Revisited as US Forces Tobacco Exports in Asia. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(6):659–662. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.80.6.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chantornvong S, McCargo D. Political economy of Tobacco Control in Thailand. Tob Control. 2001;10(1):48–54. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Collin J, Legresley E, MacKenzie R, Lawrence S, Lee K. Complicity in contraband: British American Tobacco and cigarette smuggling in Asia. Tob Control. 2004;13 Suppl 2:ii104–ii111. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khor YL, Hussein A. Professionalism and ethics: is the tobacco industry damaging the health of the public relations profession? Kajian Malaysia. 2006;24(1 & 2):55–71. [Google Scholar]

- 59.MacKenzie R, Lee K, LeGresley E. To ‘enable our legal product to compete effectively with the transit market’: British American Tobacco’s strategies in Thailand following the 1990 GATT dispute. Glob Public Health. 2016;11(3):348–362. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2015.1050049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dean M, Dean M. British American tobacco shrugs off smuggling charges. Lancet. 2000;355(9203):557–557. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)73208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nguyen MT, Denniston R, Nguyen HTT, Hoang TA, Ross H, So AD. The empirical analysis of cigarette tax avoidance and illicit trade in Vietnam, 1998-2010. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e87272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.MacKenzie R, Collin J, Sriwongcharoen K, Muggli ME. “If we can just ‘stall’ new unfriendly legislations, the scoreboard is already in our favour”: transnational tobacco companies and ingredients disclosure in Thailand. Tob Control. 2004;13 Suppl 2:ii79–ii87. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Tan YL. It’s only words: interference in implementing health warnings in Cambodia. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2010.

- 64. Tan YL, Dorotheo U. The ASEAN Tobacco Control atlas, second edition. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2014.

- 65. Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance. Tobacco industry expanding in Indonesia. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2014.

- 66.Savell E, Gilmore AB, Fooks G. How Does the Tobacco Industry Attempt to Influence Marketing Regulations? A Systematic Review. Plos One. 2014;9(2):e87389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hefler M. Philippines: tobacco industry duplicity laid bare. Tob Control. 2018;27(5):487–487. [Google Scholar]

- 68.MacKenzie R, Collin J. ‘A preferred consultant and partner to the Royal Government, NGOs, and the community’: British American Tobacco’s access to policy-makers in Cambodia. Glob Public Health. 2017;12(4):432–448. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1170868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Assunta M, Chapman S. A mire of highly subjective and ineffective voluntary guidelines: tobacco industry efforts to thwart tobacco Control in Malaysia. Tob Control. 2004;13 Suppl 2:ii43–50. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance. Denormalizing the tobacco industry: through effective implementation of FCTC Article 5.3. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2013.

- 71.Barraclough S, Morrow M. A grim contradiction: The practice and consequences of corporate social responsibility by British American tobacco in Malaysia. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(8):1784–1796. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Astuti PAS, Freeman B. “It is merely a paper tiger” Battle for increased tobacco advertising regulation in Indonesia: content analysis of news articles. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016975. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance. Anti-corruption and Tobacco Control. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2017.

- 74.Nichter M, Padmawati S, Danardono M, Ng N, Prabandari Y, Nichter M. Reading culture from tobacco advertisements in Indonesia. Tob Control. 2009;18(2):98–107. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.025809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Tan YL. Implementing pictorial health warnings in Malaysia: challenges and lessons learned. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2010.

- 76.Assunta M, Ritthiphakdee B, Soerojo W, Cho MM, Jirathanapiwat W. Tobacco industry interference: a review of three South East Asian countries. Indian Journal of Public Health. 2017;61(Suppl):S35–S39. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_232_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kolandai MA. Tobacco industry interference index: ASEAN report on implementation of WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Article 5.3. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2017.

- 78.Sidipratomo P. Indonesia: Exposé on tobacco industry interference. Tob Control. 2013;22(5):291. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ross H. Undermining global best practice in tobacco taxation in the ASEAN region. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2015.

- 80. Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance. Tobacco industry interference index: 2015 ASEAN report on implementation of WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Article 5.3. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81. Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance. Tobacco industry interference index: 2016 ASEAN report on implementation of WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Article 5.3. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82. Ross H. A critique of the ITIC/OE Asia-14 illicit tobacco indicator 2013. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2015.

- 83. Corporate Accountability International, Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance. Primer on good governance and Tobacco Control. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2014.

- 84.Barnoya J, Glantz SA. The tobacco industry’s worldwide ETS consultants project: European and Asian components. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16(1):69–77. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Assunta M, Fields N, Knight J, Chapman S. “Care and feeding”: the Asian environmental tobacco smoke consultants programme. Tob Control. 2004;13 Suppl 2:ii4–ii12. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.005199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tong EK, Glantz SA. ARTIST (Asian regional tobacco industry scientist team): Philip Morris’ attempt to exert a scientific and regulatory agenda on Asia. Tob Control. 2004;13 Suppl 2:ii118–124. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.MacKenzie R, Collin J. “A Good Personal Scientific Relationship’’: Philip Morris Scientists and the Chulabhorn Research Institute, Bangkok. PloS Med. 2008;5(12):1737–1748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Kin F, Yong CY, Tan YL, Assunta M. A perfect deception: corporate social responsibility activities in ASEAN. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2008.

- 89.Kin F, Lian TY, Yoon YC. How the tobacco industry circumvented ban on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship: Observations from selected Asean countries. Asian Journal of WTO and International Health Law and Policy. 2010;5(2):449–465. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Achadi A, Soerojo W, Barber S. The relevance and prospects of advancing tobacco control in Indonesia. Health Policy. 2005;72(3):333–349. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance. Asia-11 illicit tobacco indicator 2012: more myth than fact. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2014.

- 92. Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. U.S. Chamber of Commerce: blowing smoke for big tobacco. Washington, DC: Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids; 2015.

- 93. Tan YL, Dorotheo EU. The tobacco control atlas: ASEAN region, third edition. Bangkok, Thailand2016.

- 94. Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance. Tobacco industry interference index: ASEAN report on implementation of WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Article 5.3. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95. Kolandai MA. Tobacco industry interference index: ASEAN report on implementation of WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Article 5.3. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2018.

- 96.Assunta M, Dorotheo EU. SEATCA Tobacco Industry Interference Index: a tool for measuring implementation of WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Article 53. Tob Control. 2016;25(3):313–318. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Reyes IPN. Measures to control the tobacco supply chain in the ASEAN. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2014.

- 98.Mamudu HM, Hammond R, Glantz SA. Project Cerberus: tobacco industry strategy to create an alternative to the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(9):1630–1642. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2007.129478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance. Profiting from death: exposing tobacco industry tactics in ASEAN countries. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2008.

- 100.Assunta M, Chapman S. Industry sponsored youth smoking prevention programme in Malaysia: a case study in duplicity. Tob Control. 2004;13 Suppl 2:ii37–ii42. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.007732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance, Health Justice. Toolkit for policy makers and advocates: preventing tobacco industry interference. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2010.

- 102.Knight J, Chapman S. “Asia is now the priority target for the world anti-tobacco movement”: attempts by the tobacco industry to undermine the Asian anti-smoking movement. Tob Control. 2004;13 Suppl 2:ii30–ii36. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Reyes JL, Kolandai MA. Child Labour in Tobacco Cultivation in the ASEAN Region. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2018.

- 104. Assunta M, Jirathanapiwat W. Terminate tobacco industry corporate giving: a review of CSR in ASEAN. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2016.

- 105.MacKenzie R. “An example for corporate social responsibility”: British American Tobacco’s response to criticism of its Myanmar subsidiary, 1999–2003. Asia Pac Policy Stud. 2018;5(2):298–312. doi: 10.1002/app5.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance. End tobacco industry corporate giving: a review of CSR in Southeast Asia. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2014.

- 107.MacKenzie R, Collin J. Philanthropy, politics and promotion: Philip Morris’ “charitable contributions” in Thailand. Tob Control. 2008;17(4):284–285. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.024935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Assunta M, Jirathanapiwat W. End tobacco industry corporate giving: a review of CSR in Southeast Asia. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2015.

- 109.McCall C. Tobacco advertising still rife in southeast Asia. Lancet. 2014;384(9951):1335–1336. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61804-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Jirathanapiwat W, Kolandai MA, Dorotheo EU, Tan YL, Ritthiphakdee B. Hijacking ‘sustainability’ from the SDGs: review of tobacco-related CSR activities in the ASEAN region. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2017.

- 111.Charoenca N, Mock J, Kungskulniti N, Preechawong S, Kojetin N, Hamann SL. Success counteracting tobacco company interference in Thailand: an example of FCTC implementation for low- and middle-income countries. Int J Environ Rese Public Health. 2012;9(4):1111–1134. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9041111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Arli D, Rundle-Thiele S, Lasmono H. Consumers’ evaluation toward tobacco companies: Implications for social marketing. Marketing Intelligence and Planning. 2015;33(3):276–291. doi: 10.1108/MIP-01-2014-0015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Reynolds C. The fourth largest market in the world. Tob Control. 1999;8(1):89–91. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance. Child labour in tobacco cultivation in the ASEAN region. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2013.

- 115.Barraclough S, Morrow M. Tobacco and the Malays: Ethnicity, health and the political economy of tobacco in Malaysia. Ethn Health. 2017;22(2):130–144. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2016.1244620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ayomi M. Tobacco industry and sustainability: a case of Indonesia Cigaretes Company. Asia-Pacific Management and Business Application. 2013;2(2):132–143. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lee K, Gong L, Eckhardt J, Holden C, Lee S. KT&G: From Korean monopoly to ‘a global name in the tobacco industry. ’ Glob Public Health. 2017;12(3):300–314. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1273367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Bienassis Cd. Altadis Foundation’s new recipe for a strengthened social impact. https://www.stone-soup.net/index.php/en/news/340-altadis-foundation-s-new-recipe-for-a-strengthened-social-impact. Accessed December 24, 2019. Published 2015.

- 119. Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance. Amcham must stop championing the tobacco industry. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2015.

- 120. Jaime V Ongpin Foundation. PMFTC-Region I assisted coops formulate sustainability plans. Jaime V Ongpin Foundation Previous Projects Implemented 2010(est); https://jvofi.org/pmftc-region-i-assisted-coops-complete-sustainability-workshop/. Accessed December 24, 2019.

- 121. Philip Morris International. 2018 charitable contributions at a glance. 2019(est); https://www.pmi.com/resources/docs/default-source/our_company/charitable-2018.pdf?sfvrsn=d97d91b5_2. Accessed December 24, 2019.

- 122. Guazon TM. Cycle of poverty in tobacco farming: tobacco cultivation in Southeast Asia. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2008.

- 123.Van Minh H, Giang KB, Bich NN, Huong NT. Tobacco farming in rural Vietnam: questionable economic gain but evident health risks. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Tan YL, Dorotheo U. The ASEAN Tob Control atlas. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2013.

- 125.Assunta M. Tobacco industry’s ITGA fights FCTC implementation in the Uruguay negotiations. Tob Control. 2012;21(6):563–568. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Nimpitakpong P. Status of pack display ban at point of sale in Thailand. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2014.

- 127. Kolandai MA, Jirathanapiwat W. Lucrative retailer incentives increase cigarette sales: report on five ASEAN countries. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2019.

- 128.Hefler M. Southeast Asia: Indonesia lagging on tobacco industry interference. Tob Control. 2016;25(6):614–615. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Reynolds C. Tobacco advertising in Indonesia: “the defining characteristics for success”. Tob Control. 1999;8(1):85–88. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Barraclough S. Women and tobacco in Indonesia. Tob Control. 1999;8(3):327–332. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.3.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Farley M. A familiar scent of monopoly. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-mar-21-mn-31117-story.html. Accessed December 26, 2019. Published 1989.

- 132. Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance. ASEAN status of tobacco promotion at point-of-sale. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2014.

- 133. Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance. Advertising at point-of-sale gone berserk: a case for pack display ban. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2012.

- 134. Tan YL. Abuse of the pack to promote cigarettes in the region. Bangkok, Thailand; 2010.

- 135. Kin F, Yong CY, Tan YL. Fatal attraction: the story of point-of-sale in the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2008.

- 136.Jenkins CNH, Pham Xuan D, Do Hong N. et al. Tobacco use in Vietnam: Prevalence, predictors, and the role of the transnational tobacco corporations. JAMA. 1997;277(21):1726–1731. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.21.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Changpetch P, Haughton D. Associations and determinants of tobacco consumption in Thailand. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.kjss.2017.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Morrow M, Barraclough S. Tobacco Control and gender in Southeast Asia Part I: Malaysia and the Philippines. Health Promot Int. 2003;18(3):255–264. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dag021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Webster PC. Indonesia: The tobacco industry’s “Disneyland”. CMAJ. 2013;185(2):E97–E98. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Kin F, Yong CY, Tan YL. Targeting the poor: casualties in Cambodia, Indonesia and Laos. Bangkok, Thailand: 2008.

- 141.Assunta M, Chapman S. The tobacco industry’s accounts of refining indirect tobacco advertising in Malaysia. Tob Control. 2004;13 Suppl 2:ii63–70. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Assunta M, Chapman S. “The world’s most hostile environment”: how the tobacco industry circumvented Singapore’s advertising ban. Tob Control. 2004;13 Suppl 2:ii51–57. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Southeast Asian Tobacco Control Alliance. You’re the target: new global Marlboro campaign found to target teens. Bangkok, Thailand: SEATCA; 2014.

- 144.Yong HH, Borland R, Hammond D. et al. Levels and correlates of awareness of tobacco promotional activities among adult smokers in Malaysia and Thailand: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Southeast Asia (ITC-SEA) Survey. Tob Control. 2008;17(1):46–52. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.021964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Sirichotiratana N, Techatraisakdi C, Rahman K. et al. Prevalence of smoking and other smoking-related behaviors reported by the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) in Thailand. BMC Public Health. 2008;8 Suppl 1:S3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-S1-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Saito J, Yasuoka J, Poudel KC, Foung L, Vilaysom S, Jimba M. Receptivity to tobacco marketing and susceptibility to smoking among non-smoking male students in an urban setting in Lao PDR. Tob Control. 2013;22(6):389–394. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.van der Eijk Y, Lee JK, P ML. How Menthol Is Key to the Tobacco Industry’s Strategy of Recruiting and Retaining Young Smokers in Singapore. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(3):347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Simpson D. Malaysia: racing round the hurdles. Tob Control. 2004;13(2):106–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Simpson D. Malaysia: camel tourism trick. Tob Control. 2006;15(4):277–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Mackay J, Amos A. Women and tobacco. Respirology. 2003;8(2):123–130. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Astuti PAS, Assunta M, Freeman B. Raising generation ‘A’: A case study of millennial tobacco company marketing in Indonesia. Tob Control. 2018;27(e1):e41–e49. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Villanueva WG. Nothing is sacred on the Philippine smoking front. Tob Control. 1997;6(4):357–359. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.4.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Ashraf H. Malaysia steps up anti-tobacco legislation. Lancet. 2002;360(9333):627. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09828-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]