Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Our objective was to conduct a systematic review of the published literature on housing instability during pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes and perinatal healthcare utilization.

DATA SOURCES:

We performed a systematic search in November 2020 using Embase, MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, and Scopus using terms related to housing instability during pregnancy, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and perinatal healthcare utilization. The search was limited to the United States.

STUDY ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA:

Studies examining housing instability (including homelessness) during pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes (including preterm birth, low birthweight neonates, and maternal morbidity) and perinatal healthcare utilization were included.

METHODS:

Two authors screened abstracts and full-length articles for inclusion. The final cohort consisted of 14 studies. Two authors independently extracted data from each article and assessed the study quality using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation tool. Risk of bias was assessed using the National Institutes of Health Study Quality Assessment Tools.

RESULTS:

All included studies were observational, including retrospective cohort (n=10, 71.4%), cross-sectional observational (n=3, 21.4%), or prospective cohort studies (n=1, 7.1%). There was significant heterogeneity in the definitions of housing instability and homelessness. Most of the studies only examined homelessness (n=9, 64.3%) and not lesser degrees of housing instability. Housing instability and homelessness during pregnancy were significantly associated with preterm birth, low birthweight neonates, neonatal intensive care unit admission, and delivery complications. Among studies examining perinatal healthcare utilization, housing instability was associated with inadequate prenatal care and increased hospital utilization. All studies exhibited moderate, low, or very low study quality and fair or poor internal validity.

CONCLUSION:

Although data on housing instability during pregnancy are limited by the lack of a standardized definition, a consistent relationship between housing instability and adverse pregnancy outcomes has been suggested by this systematic review. The evaluation and development of a standardized definition and measurement of housing instability among pregnant individuals is warranted to address future interventions targeted to housing instability during pregnancy.

Keywords: adverse perinatal outcomes, healthcare utilization, homelessness, housing instability, social determinants of health, systematic review

Introduction

Between 4% and 9% of pregnant individuals experience homelessness and even more have unstable housing arrangements during pregnancy.1,2 These rates are expected to rise as the national rates of housing instability continue to increase,3 a public health challenge that has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.4,5 Housing status is a crucial social determinant of health; among the general adult population, housing instability is associated with poor healthcare utilization and adverse health outcomes, such as depression and mortality.6–9 However, studying housing instability remains challenging because no standardized definition or measure exists.10 Most biosocial research has approached housing as a dichotomous variable of homelessness, but there has been a shift to consider the full spectrum of housing instability, which may include parameters such as frequent moves, poor housing quality, or overcrowding.10,11

Pregnancy is a time of physical, social, and emotional change in which the association between housing status and health may be even stronger because of the need for health behavior changes and the enhanced engagement with healthcare.12,13 Social determinants of health are known to influence perinatal morbidity.14,15 With regards to housing, pregnant individuals who report housing instability are more likely to self-identify as non-Hispanic Black, be younger, have a lower educational attainment, and have a lower income than those with stable housing16–18; all of these sociodemographic factors have been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes14

Objective

Although several studies have explored the association between housing instability and adverse pregnancy outcomes, the results have not been synthesized. With rising national rates of housing instability and increasing attention being paid to social determinants of pregnancy-related morbidity,5,14 evaluating the impact of housing instability on the health of pregnant individuals is imperative. Thus, we performed a systematic review to assess the relationship between housing instability during pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes and perinatal healthcare utilization.

Materials and Methods

The review protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO under registration number CRD42020219945. This study was designed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 checklist.

Eligibility criteria, information sources, search strategy

A medical librarian created search strategies in collaboration with a maternal-fetal medicine physician for the concepts of housing instability, pregnant individuals, and adverse pregnancy outcomes (Appendix 1). The search strategies were launched in PubMed (MEDLINE) 1946–, Embase (Elsevier) 1947–, Scopus (Elsevier) 1823–, and the Cochrane Library (Wiley). The search strategies for the Embase, Cochrane, and Scopus databases were adapted from the PubMed (MEDLINE) search strategy (Appendix 1). Clinical-Trials.gov was also searched. All databases were searched back to their inception and no language or date limits were applied. Searches were completed in November 2020.

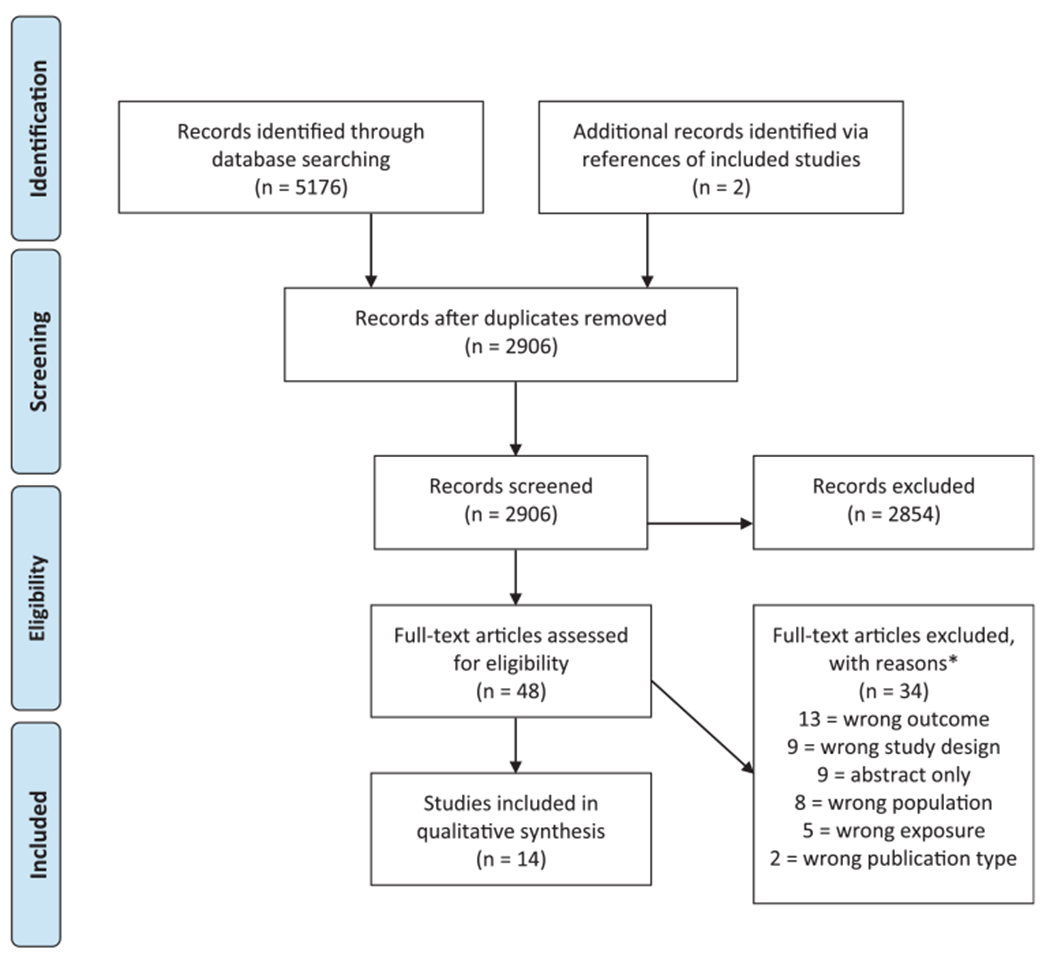

Duplicates were identified and removed in Endnote, giving a total of 2934 unique citations. All results were exported to Rayyan (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Doha, Qatar), software designed to support researchers in conducting systematic reviews, in which an additional 30 duplicates were identified. Two additional studies were identified by reviewing the references of included studies. The final set for screening included 2906 unique references (Figure).

FIGURE. PRISMA flow diagram.

The asterisk represents that exclusions are not mutually exclusive.

PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Study selection

The research team developed inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine the eligibility of studies during the screening process (Appendix 2). The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) study population of pregnant individuals at any point during pregnancy or up to 6 weeks postpartum; (2) housing instability measured at the individual level as the exposure of interest; (3) outcomes focused on adverse pregnancy outcomes or perinatal healthcare utilization; (4) quantitative and empirical study design; (5) English language; and (6) study population located in the United States. Adverse pregnancy outcomes included, but were not limited to, preterm birth, preterm labor, low birthweight, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, and maternal or neonatal death. Perinatal healthcare utilization outcomes included, but were not limited to, quality of prenatal care, birth hospitalization length of stay, and postpartum readmissions. Outcomes could be reported as odds ratios (ORs), risk ratios (RRs), or mean differences.

For the purpose of this review, housing instability was defined as meeting 1 or more of the following criteria: high housing costs (>30% of monthly household income), poor housing quality, unstable neighborhoods, overcrowding, homelessness or lack of housing, frequent moves, or temporary housing programs or shelters. To focus on housing instability as an individual-level social determinant of health, we exclusively included studies that defined the exposure of housing instability at the individual level and thus excluded studies that evaluated housing- or neighborhood-level exposures at the population level (eg, census tract or neighborhood).

Study selection was performed using Rayyan. To ensure consistency, 2 authors (J.D.D. and K.H.) conducted a preliminary review of 100 randomly selected abstracts. After resolving any disagreements, the same authors reviewed all abstracts and titles for inclusion. A third author (L.M.Y.) settled any disagreements. Once the relevant abstracts were agreed on, full-text analysis of the included abstracts was performed by 2 authors (J.D.D. and K. H.), again with a third author (L.M.Y.) settling any disagreements.

Study characteristics

The data from studies that met the final inclusion criteria were independently abstracted by 2 authors and included the first author, publication year, study design, population, exposure, outcome, and results, and the study quality was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) framework.19 Definitions and sources of housing instability and homelessness were extracted from all included articles.

Assessment of risk of bias

Two authors (J.D.D. and K.H.) separately assessed the risk of bias for each included study using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies.20 This tool is specifically designed to assist reviewers in critically appraising the internal validity of studies. Studies were deemed “good,” “fair,” or “poor.” In the case when the authors disagreed on a rating, a third author (L.M.Y.) resolved any disagreements. A detailed list of these questions have been provided in Appendix 3. Poor scores required additional comments to justify the rating (Appendix 4).

Results

Study selection

A total of 2906 records were identified and screened. The screening process yielded 14 studies that met the inclusion criteria (Figure).1,2,18,21–31 All studies were observational; the studies were either retrospective cohort studies (n=10, 71.4%), cross-sectional observational studies (n=3, 21.4%), or prospective cohort studies (n=1, 7.1%) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Overview of the included studies evaluating homelessness or housing instability and pregnancy outcomes

| Study no. | Title | Author, y | Study design | Population | Sample size | Outcomes | Results | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure: maternal homelessness | ||||||||

| 1 | Association between homelessness and hospital readmissions––an analysis of 3 large states | Khatana et al,21 2020 | Retrospective cohort | Recently postpartum individuals in Florida, Massachusetts, and New York from 2010 to 2015 | N=92,720 | Hospitalization owing to complications of pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium within 30-d and 90-d postpartum | • 30-d readmission rates for which the cause of index hospitalization was complications of pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium were 0.2% points lower (P=.01) in the homeless group. • Similar trends were seen for 90-d readmission rates. |

Low |

| 2 | Characteristics of mothers and infants living in homeless shelters and public housing in New York City | Reilly et al,22 2019 | Cross-sectional | Individuals and newborns in New York City from 2008 to 2014 | N=41,076; 3228 births matched to homeless shelter addresses 37,848 births matched to stable housing | Low birthweight (<2500 g), preterm birth (GA <37 wk), NICU admission, breastfeeding following delivery, infant death within 1 y, infant discharge status | • Neonates born to mothers living in a shelter were more likely to have a low birthweight (13.3% vs 12.0%; P=.02), be preterm (14.5% vs 12.8%; P<.0001), be admitted to the NICU (14.8% vs 12.6%; P<.0001), less likely to exclusively breastfeed (77.4% vs 80.8%; P<.001), and be discharged home at the same time as the mother (73.4% vs 80.1%; P<.0001)when compared with mothers not living in shelters. • There was no significant association between maternal homelessness and infant death within 1 y (1.1% vs 0.8%; P=.07). |

Very low |

| 3 | Effects of maternal homelessness, supplemental nutrition programs, and prenatal PM (2.5) on birthweight | Rhee et al,23 2019 | Retrospective cohort study | Individuals and children enrolled in Boston-based Children’s HealthWatch cohort from 2007 to 2015 | N=3366; 524 pregnant individuals who are homeless and 2842 pregnant individuals who are not homeless | Infant birthweight (g) | Maternal homelessness during pregnancy was associated with a 56 g lower birth-weight (95% CI, −97.8 g to −13.7 g). | Low |

| 4 | Health behaviors and infant health outcomes in homeless pregnant women in the United States | Richards et al,2 2011 | Retrospective cohort study | Recently postpartum individuals participating in PRAMS 31 states/cities from 2000 to 2007 | N=10,671,258; 441,528 individuals who are homeless and 10,229,730 individuals who are not homeless | Prenatal visits in first trimester, GA at delivery, infant birthweight (g), infant length of time in hospital, NICU admission, breastfeeding initiation after delivery, breastfeeding duration | • Pregnant individuals who are homeless were less likely to have a prenatal visit during the first trimester (aOR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.9–2.2) and to breastfeed their infant (aOR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2–1.6). • Pregnant individuals who are homeless were less likely to not have an NICU admission (aOR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.7–0.8). • Mean birthweight was lower for individuals who are homeless than for individuals who are not homeless (3242 g vs 3311 g; P<.001). |

Low |

| 5 | Homelessness contributes to pregnancy complications | Clark et al,18 2019 | Retrospective cohort study | Pregnant individuals with Medicaid coverage in Massachusetts from January 2008 to June 2015 | N=9124; 4379 pregnant individuals who were homeless and 4745 pregnant individuals who were not homeless | Hypertension complicating pregnancy, iron deficiency and other anemia, polyhydramnios, hemorrhage during pregnancy, early or threatened labor, other complications of birth affecting mother | • Individuals who are homeless had significantly higher odds of pregnancy-related conditions, such as hypertension complicating pregnancy (aOR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.3–1.6), iron deficiency and other anemia (aOR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.2–1.4), polyhydramnios (aOR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.6–1.9), hemorrhage (aOR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.7–2.0), early or threatened labor (aOR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.8–2.1), and other complications of birth (aOR, 2.6; 95% CI, 2.4–2.8). | Low |

| 6 | Homelessness during pregnancy: a unique, time-dependent risk factor of birth outcomes | Cutts et al,1 2015 | Cross-sectional | <2 y postpartum individuals recounting experiences during pregnancy from 5 US cities from 2009 to 2011 | N=9666; 580 individuals with any prenatal homelessness and 9086 consistently housed individuals | Preterm birth (GA <37 wk), low birthweight (<2500 g) | • Individuals with any antenatal homelessness had greater odds of preterm birth (aOR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.1–1.8). There was no association between prenatal homelessness and birthweight (aOR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.98–1.56). | Very low |

| 7 | Prenatal maternal stress and physical abuse among homeless women and infant health outcomes in the United States | Merrill et al,24 2011 | Retrospective cohort | Recently postpartum individuals participating in PRAMS 31 states/cities from 2000 to 2007 | N=10,586,614; 434,534 individuals who are homeless and 10,152,080 individuals who are not homeless | Prenatal care as early as wanted, preterm birth (<37 wk GA), birthweight | • Individuals who are not homeless had higher odds of prenatal care early as wanted (aOR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.63–1.90) and lower odds of preterm labor (aOR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.68–0.79) than in individuals who are homeless. • Birthweight among infants of individuals who are homeless was an average of 17.37 g (standard error, 1.01; P<.001) lower than for infants of individuals who are not homeless. |

Low |

| 8 | Severity of homelessness and adverse birth outcomes | Stein et al,26 2000 | Cross-sectional | Individuals of reproductive age in Los Angeles who reported a live birth within the last 3 y | Total N is unknown; 974 homeless individuals compared with national norms | Low birthweight (<2500 g), birthweight (continuous), preterm birth (<37 wk GA), GA at delivery | • Almost 17% of the sample reported neonates who weighed <2500 g at birth as opposed to the national average of 6%. | Very low |

| 9 | The reproductive experience of women living in hotels for the homeless in New York City | Chavkin et al,271987 | Retrospective cohort | Singleton births in New York City from 1982 to 1984 | N=255,206; 401 individuals living in homeless hotels, 13,247 individuals living in low-income housing, and 241,558 individuals citywide | Prenatal visits, infant birthweight (g), infant mortality | • Individuals living in hotels had significantly fewer prenatal visits than the low-income housing group and citywide group. • There was an estimated reduction of 125 g in the neonatal birthweight associated with hotel residence and a reduction of 48 g in the neonatal birthweight associated with low-income housing project residence (P<.001). • The hotel group had a greater relative risk than the low-income housing project and citywide groups (respective RR, 1.4; P=.01; RR, 2.07; P<.01). The hotel residents had a 2.5-fold reduction in the likelihood of getting prenatal care than the low-income housing group and a 4.12-fold reduction in the likelihood than the citywide population. |

Very low |

| Exposure: maternal housing instability | ||||||||

| 10 | Associations between unstable housing, obstetrical outcomes, and perinatal healthcare utilization | Pantell et al,28 2019 | Retrospective cohort | Births from singleton pregnancies in California from 2007–2012 | N=5588; 2794 births to people with unstable housing code with propensity-matched controls | Preterm birth (GA<37 wk), GA at birth, preterm labor, preeclampsia, chorioamnionitis, placental abruption, small for gestational age, long length of stay, maternal ED visit within 3 mo and 1 y after delivery, maternal readmission within 3 mo and 1 y after delivery | • Individuals with unstable housing had greater odds of preterm birth (aOR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.0–1.4) and preterm labor (aOR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2–1.6). No relationship with any other obstetrical outcome was found. • Individuals with unstable housing were more likely to have a long length of stay after childbirth (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.4—1.8), an emergency department visit within 3 months (OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 2.1–2.8) and 1 y (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 2.4–3.0,) after delivery. • Individuals with unstable housing were more likely to have a readmission within 3 mo (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 2.2–3.4) and 1 y after delivery (OR, 2.6; 95% CI, 2.2–3.0). |

Moderate |

| 11 | Housing instability and birthweight among young urban mothers | Carrion et al,29 2015 | Retrospective cohort study of a cluster randomized controlled trial | Second trimester pregnant individuals between 14 and 21 y old at community hospitals and health centers in New York City | N=613; 175 with housing instability and 438 with stable housing | Infant birthweight (g) | • Housing instability was significantly associated with lower birthweight. • On average, infants of housing stable individuals weighed 3155.96 g (SD, ±532.69), whereas infants of housing instable individuals weighed 3028.17 g (SD, ±641.18). |

Low |

| 12 | Maternity shelter care for adolescents: its effect on incidence of low birthweight | LaGuardia et al,30 1989 | Prospective cohort | Adolescents (19 y and younger) who delivered at the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center in New York City from 1984 to 1986 | N=225; 112 individuals residing in a shelter; 113 individuals not residing in a shelter (ie, housed) individuals | Low birthweight (<2500 g), preterm birth (<37 wk), maternal ICU admission, average number of days in hospital per person with preterm labor | • Sheltered individuals had lower rates of low birthweight neonates and preterm birth than the control group. • The sheltered group spent a greater number of days in hospital after preterm labor (11.4% vs 5.8%; P<.025). |

Low |

| 13 | Predicting preterm birth among women screened by North Carolina’s Pregnancy Medical Home Program | Tucker et al,31 2015 | Retrospective cohort | Individuals participating in North Carolina’s Pregnancy Medical Home Program screened between 6–24 wk gestational age from 2011 to 2012 | N=15,427; 956 individuals with unstable housing; 14,471 individuals with stable housing | Preterm birth (<37 wk GA) | • Individuals with unsafe or unstable housing have greater odds of preterm birth than in individuals with stable housing (aOR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.04–1.53). | Very low |

| 14 | Severe housing insecurity during pregnancy: association with adverse birth and infant outcomes | Leifheit et al,25 2020 | Retrospective cohort | Mother-infant dyads enrolled in the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study in 20 large US cities from 1998 to 2000 | N=3428; 55 severely housing insecure mother-infant dyads; 3373 mother-infant dyads who were not experiencing severe housing insecurity | Low birthweight (<2500 g), preterm birth (<37 wk GA), NICU admission | • Individuals experiencing severe housing insecurity during pregnancy had 1.73 times higher risk of having low birthweight neonates and/or preterm birth and 1.64 times higher risk for NICU admission than individuals who did not experience severe housing insecurity (95% CI, 1.28–2.32; 95% CI, 1.17–2.31, respectively). | Low |

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; GA, gestational age; ICU, intensive care unit; PRAMS, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System; RR, relative risk; SD, standard deviation.

Study characteristics

The majority (n=9, 64.3%) of studies examined homelessness during pregnancy as the primary exposure, whereas 5 (36.7%) examined housing instability. All studies measured the exposure dichotomously. Definitions of housing instability and homelessness were inconsistent across studies. Among the studies included, definitions of housing instability ranged from frequent moves, threatened eviction, inadequate housing, or being homeless at any point during pregnancy. Definitions of homelessness ranged from residence in emergency homeless shelters, sleeping on the streets, or having nowhere to sleep. More than half (n=8, 57.1%) of the studies relied on administrative data or medical records to define housing instability or homelessness, whereas 42.9% (n=6) relied on self-report (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Definitions of housing instability and homelessness among the included studies

| Definition | Source | |

|---|---|---|

| Exposure: housing instability | ||

| Carrion et al,29 2015 | ≥2 moves within the past year | Self-report |

| LaGuardia et al,30 1989 | Residence in a maternity shelter during pregnancy | Maternal medical records |

| Leifheit et al,25 2020 | Threatened eviction or homelessness during pregnancy | Maternal medical records |

| Pantell et al,28 2019 | An ICD-9 code of V60.0 (lack of housing) or V60.1 (inadequate housing) during either an ED visit or admission within 1 y before or after their birth hospitalization or during birth hospitalization | Maternal and neonate medical records |

| Tucker et al,31 2015 | No clear definition of housing instability or homelessness, but exposure was specified as inadequate housing | Community Care of North Carolina’s Case Management Information System, Medicaid claims, and birth certificates |

| Exposure: homelessness | ||

| Chavkin et al,27 1987 | Residence in a hotel used to house homeless individuals | Birth certificate files for singleton births |

| Clark et al,18 2019 | Residence in emergency shelters | Administrative data from the Emergency Assistance program and MassHealth claims and enrollment data |

| Cutts et al,1 2015 | Affirmative responses to the following questions: “Were you ever homeless or did you live in shelter when you were pregnant with this child?” and “Since your child was born has s/he ever been homeless or lived in a shelter?” In addition, included motel and other transitional living situations, or not having a steady place to sleep at night | Self-report |

| Khatana et al,21 2020 | Noted to be homeless at time of discharge from index hospitalization | Discharge data and administrative claims data |

| Merrill et al,24 2011 | Agreement with the following statement: “This question is about things that may have happened during the 12 mo before your new baby was born…I was homeless.” | Self-report |

| Rhee et al,23 2019 | Ever homeless or lived in shelters during pregnancy | Self-report |

| Reilly et al,22 2019 | Residence in a homeless shelter during pregnancy | Bureau of Vital Statistics birth records |

| Richards et al,2 2011 | Agreement with the following statement: “This question is about things that may have happened during the 12 mo before your new infant was born…you were homeless.” | Self-report |

| Stein et al,26 2000 | Affirmative responses to any of the following statements: spent any of the past 30 nights (1) in a mission, homeless shelter, or transitional shelter, a hotel paid for by a voucher, a church or chapel, an all-night theater or other indoor public place, an abandoned bldg., a vehicle, the street or other outdoor public place; (2) in a rehabilitation for homeless people and stayed in 1 of the settings mentioned in (1) during any of the 30 nights before she entered the program | Self-report |

ED, emergency department; ICD, International Classification of Diseases.

There was significant heterogeneity in the adverse pregnancy outcomes evaluated. The most common outcomes of interest were birthweight as a continuous variable (n=6, 42.8%), preterm birth (<37 weeks’ gestation; n=6, 42.8%), and low birthweight (<2500 g; n=5, 35.7%). Other outcomes included preterm labor (<37 weeks’ gestation; n=3), NICU admission (n=3), gestational age at birth (n=1), delivery complications (n=2), and infant mortality (n=1). Delivery complications included preeclampsia, chorioamnionitis, placental abruption, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, iron deficiency or other anemia, and other complications of birth affecting management of the parturient.

Health services outcomes of interest included prenatal care timing and utilization (n=5), 90-day maternal readmission (n=2), long hospital length of stay (n=2), breastfeeding (n=2), 30-day maternal readmission (n=1), 1-year maternal readmission (n=1), and maternal emergency department (ED) utilization (n=1). Among the included studies, prenatal care was defined heterogeneously with outcomes defined variably as presence of prenatal care, prenatal care in the first trimester, adequate prenatal care, and prenatal care as early as intended.

Study quality and risk of bias

Most of the studies had a low (n=8, 57.1%) or very low (n=5, 35.7%) GRADE score, whereas 1 study was rated as moderate (Table 1). All studies exhibited fair or poor internal validity. The low-quality designation was primarily driven by nonblinding during outcomes assessment, unreliable measures of housing stability and homelessness via medical records or administrative records, and concerns for recall and selection bias. An additional limitation of the cross-sectional studies was the measurement of housing instability or homelessness at the same time as the outcome (Table 3). Few prospective studies exist. Justifications for poor quality ratings are provided in Appendix 4. Most studies included individual race, age, mental health history, or substance use as covariates in adjusted logistic regression models.1,2,18,21,23–25,28,29,31

TABLE 3.

Risk of bias assessment for included studies using the National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies

| Study no. | Author, y | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Q14 | Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Khatana et al,21 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Fair |

| 2 | Reilly et al,22 2019 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Poor |

| 3 | Rhee et al,23 2019 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | CD | Y | Fair |

| 4 | Richards et al,2 2011 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Fair |

| 5 | Clark et al,18 2019 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Fair |

| 6 | Cutts et al,1 2015 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Poor |

| 7 | Merrill et al,24 2011 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | NA | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Fair |

| 8 | Leifheit et al,25 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Fair |

| 9 | Stein et al,26 2000 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Poor |

| 10 | Chavkin et al,27 1987 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Fair |

| 11 | Pantell et al,28 2019 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Fair |

| 12 | Carrion et al,29 2015 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Fair |

| 13 | LaGuardia et al,30 1989 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Fair |

| 14 | Tucker et al,31 2015 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Fair |

Q1: Was the research question or objective clearly stated?

Q2: Was the study population clearly specified and defined?

Q3: Was the participation rate of eligible persons at least 50%?

Q4: Were all the subjects selected or recruited from the same or similar populations (including the same time frame)? Were inclusion and exclusion criteria for being in the study prespecified and applied uniformly to all participants?

Q5: Was a sample size justification, power description, or variance and effect estimates provided?

Q6: For the analyses in this paper, were the exposure(s) of interest measured before the outcome(s) being measured?

Q7: Was the time frame sufficient so that one could reasonably expect to see an association between exposure and outcome if it existed?

Q8: For exposures that can vary in amount or level, did the study examine different levels of the exposure as related to the outcome (eg, categories of exposure, or exposure measured as continuous variable)?

Q9: Were the exposure measures (independent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants?

Q10: Was the exposure(s) assessed more than once over time?

Q11: Were the outcome measures (dependent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants?

Q12: Were the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of participants?

Q13: Was loss to follow-up after baseline 20% or less?

Q14: Were key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship between exposure(s) and outcome(s)?

CD, cannot determine; N, no; NA, not applicable; Y, yes.

Synthesis of results

Homelessness was associated with a reduction in birthweight (−56 g; 95% confidence interval [CI] −97.8 to −13.7; −48 g; P<.001; 3242 g vs 3311 g; P<.001; 3028 g vs 3156 g; P<.05).23,24,27,29 In all but 1 study (adjusted OR [aOR] 1.24; 95% CI, 0.98–1.56),1 housing instability or homelessness was associated with increased odds of and risk for low birthweight (aOR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.04–1.53; aRR, 2.18; P<.01).22,27 Housing instability or homelessness was consistently associated with increased odds of preterm birth in multiple studies with increased adjusted odds ranging from 20% to 43%.1,22,28,31 One study found no association, but this study had a limited sample size, with <20 individuals in each group who experienced preterm birth, was rated as very low using the GRADE approach and had poor internal validity.30 One study found that severe housing instability was associated with a 73% greater odds of low birth-weight and/or preterm birth (aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.28–2.32).25

Housing instability or homelessness was associated with increased odds of preterm labor (aOR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2–1.6; homeless as reference group: aOR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.68–0.79),24,28 and NICU admission (14.8% vs 12.6%; P<.0001; outcome: no NICU admission aOR, 0.80;95% CI, 0.7–0.8).2,22,25 Among pregnant individuals with Medicaid coverage in Massachusetts homelessness was associated with multiple delivery complications, such as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (aOR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.3–1.6) iron deficiency and other anemia (aOR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.2–1.4), antepartum hemorrhage (aOR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.7–2.0), “early or threatened” labor (aOR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.8–2.1) and other complications of birth affecting management of mother (aOR, 2.6; 95% CI, 2.4–2.8) when compared with individuals not experiencing homelessness.18 Among a cohort of singleton births in California, there was no reported association between housing instability or homelessness and pre-eclampsia, chorioamnionitis, placental abruption, infant mortality, or gestational age.28 Most of these studies examining pregnancy outcomes measured homelessness as the exposure.

Individuals who are not homeless were more likely to have a prenatal visit during their first trimester (aOR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.2–1.6)2 and reported that they started prenatal care as early as intended (aOR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.63–1.90) when compared with individuals who are homeless.24 Among individuals in New York City, homelessness was associated with a 4.12-fold greater risk (no CI reported) of receiving no prenatal care when compared with all other residents.27 Housing instability and homelessness were associated with increased odds of maternal readmission within 90 days (aOR, 2.7; 95% CI, 2.2–3.4).28 Individuals who are homeless were less likely to breastfeed their infant (homeless as reference group; aOR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2–1.6) and less likely to exclusively breastfeed (77.4% vs 80.8%; P<.0001) than individuals who are not homeless.22 Among individuals in California, housing instability was associated with a long hospital length of stay (aOR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.4–1.8) postpartum ED utilization within 90 days (aOR 2.4; 95% CI, 2.1–2.8) and 1 year (aOR, 2.7; 95% CI, 2.4–3.0), and maternal readmission within 1 year (aOR, 2.6; 95% CI, 2.2–3.0).28

Comment

Principal findings

We aimed to analyze the current literature examining the association between housing instability during pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Most of the studies showed a relationship between homelessness or housing instability and low birthweight or preterm birth. Housing instability or homelessness was in addition associated with other adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as increased odds of NICU admission and delivery complications, and differential healthcare utilization such as poor prenatal care and increased odds of postpartum readmission. However the studies had highly variable definitions for homelessness, examined homelessness almost exclusively with less focus on housing instability, and were largely rated as being of low quality and having fair or poor scores for risk of bias, in large part because of the challenges associated with prospectively studying this issue. Thus, the limitations of existing data suggest that the findings of individual studies should be interpreted with caution and present a call to action to encourage future studies on this topic.

Comparison of existing literature

Nearly two-thirds of the studies examined homelessness as the primary exposure, which is the most extreme form of housing instability,32 whereas only a few specifically examined other forms of housing instability. Before reaching the extreme circumstance of homelessness, many individuals will have experienced some alternative form of housing instability, such as difficulties with paying rent or staying with relatives, which likely contributes to future homelessness.33 Thus, identifying and examining the associated health outcomes of the full spectrum of housing instability may be crucial for the design of screening methods or interventions targeted at reducing the rates of homelessness and its health sequelae. However it is important to note that the experience of individuals who are experiencing homelessness during pregnancy is likely different from those with less severe forms of housing instability, but, further work is warranted to examine these differences. Furthermore, all studies included in this systematic review classified housing instability or homelessness as a dichotomous exposure. However, the concept of housing instability accounts for a wide range of issues related to housing, such as high housing costs, overcrowding, frequent moves, or homelessness—many of which were not included in these studies.10,11 Classifying the exposure as a dichotomous variable fails to account for the heterogeneity of housing instability as a social determinant of health and how the exposure changes over time. For instance, individuals may alternate between housing instability states throughout pregnancy. Examining housing instability as a spectrum and categorizing it based on severity warrants further investigation.

Furthermore, we identified significant heterogeneity in the definitions of housing instability and homelessness. Nevertheless, this limitation of the current literature is likely a reflection of the lack of a comprehensive and cohesive standardized definition for housing instability. In fact, housing instability is a key issue in the Economic Stability domain of the Healthy People 2020 Social Determinants of Health’s national objectives to improve health and wellbeing in the United States,32 despite it having no standardized definition. This notably differs from other widely recognized social determinants of health, such as food insecurity, poverty, or health literacy, which all have national definitions consistently used in policy, research, and clinical settings. Therefore, it is likely that the methodology of defining housing instability in the included studies underreported the true prevalence of housing instability in these populations.

In addition, homelessness and housing instability were either documented via self-report, which is subject to recall and reporting bias, or in electronic medical records (EMRs). Multiple studies noted the limitation of using EMRs, because housing status was likely only documented for the most extreme cases, thus further suggesting an underreport of pregnant individuals who are experiencing housing instability. Indeed, providers in other fields have reported not incorporating patient housing status in routine assessments and having it subsequently documented in EMRs.34

Homelessness was associated with a reduction in birthweight among 4 cohorts and increased odds of preterm birth among 4 different cohorts. The data also suggested a relationship between housing instability and delivery complications, such as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, anemia, and hemorrhage, however, these outcomes were only examined for a single cohort. Among the studies that analyzed perinatal healthcare utilization, housing instability was associated with poor prenatal care, long birth hospitalization length of stay, increased postpartum readmission rates, and postpartum ED utilization. Nonetheless, these results should be interpreted with caution because most of the outcomes were only reported in a small number of studies or were limited to a single population. In addition, most of these studies included focused on infant-related health outcomes, such as preterm birth and low birthweight, despite the rise in maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States.35 Our systematic review highlights a need for research on housing instability and homelessness to additionally focus on maternal outcomes, such as severe maternal morbidity, pregnancy or delivery complications, and obstetric healthcare utilization.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists released a Committee Opinion on the importance of screening for social determinants of health in reproductive healthcare.14 To optimize health outcomes and reduce health inequities, healthcare providers are recommended to inquire about and document social determinants of health; access to stable housing is 1 of these determinants.14 The association between housing instability and poor health outcomes is clear, and our systematic review bolsters the existing state of knowledge by providing evidence that housing may be a particularly important social determinant of pregnancy-related health. Thus, recognizing and screening for housing instability during prenatal visits is important for providers to understand their patient’s current situation. Nevertheless, screening for a social determinant of health is challenging without a standardized definition, universal measure, and acceptable and effective intervention. Previous research has suggested that the integration of a 2-question screening measure of housing instability into EMRs increased provider attention and documentation,34 however, further research is required to examine this implementation in a prenatal setting, especially because clinicians may have limited ability to intervene when housing instability is identified.

Finally, social determinants of health may be difficult to individually evaluate because of the interconnected nature of social factors. For instance, housing instability, food insecurity, and access to healthcare are likely intertwined, making it difficult to isolate the effects of one social factor on overall individual health. As research on the social determinants of perinatal health becomes more prominent, it is important to consider the best way to address the intersection of social factors with regards to adverse health outcomes and healthcare utilization.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review examined the available literature on housing instability during pregnancy. Our search strategy was comprehensive and was tested via a preliminary title and abstract screen to ensure that the authors were evaluating articles similarly. The search strategy was implemented across multiple databases and did not exclude any date ranges. To reduce selection bias, 2 reviewers separately screen articles and full texts, extracted data, and rated the final cohort of articles using GRADE and the NIH Quality Assessment Tool.

Nevertheless, our systematic review has limitations. First, as with any systematic review, articles with related but atypical search terms may be missed, although we aimed to limit this by adopting a comprehensive search strategy with a medical librarian and a maternal-fetal medicine physician. Furthermore, because of the limitations of housing instability as a social determinant of health, we were limited by the lack of a standardized definition for housing instability. To combat this, we were as inclusive as possible with regards to the variable definitions with a focus on the individual level rather than the neighborhood. Similarly, we were limited by the heterogeneity in adverse pregnancy and perinatal healthcare utilization outcomes included in the studies; for instance, only 42.8% of the included studies reported on preterm birth. Nevertheless, to capture as much perinatal data on housing instability as possible, we sought to include a wide range of outcomes related to adverse pregnancy and health utilization variables. In addition, because of our a priori goal of examining individual-level housing as a determinant of health, we were unable to extrapolate whether community-level determinants that are related to housing have similar associations with perinatal health. For example, regional differences in social services, climate, or other environmental effects may influence the effect that housing instability has on health. The studies that were included defined housing instability at different time points throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period, and therefore we are unable to determine an association between timing of the exposure and adverse pregnancy outcomes. However, it is unlikely that the housing situation of individuals experiencing some form of housing instability at one time point during pregnancy will dramatically change in a period of 1 year. Finally, the existing state of literature on this topic, with heterogeneous exposures and outcomes, precludes a meta-analysis from being conducted.

Most of the studies included in this systematic review received low quality metrics because of the necessity for observational investigation for this topic. Most of the studies utilized EMRs, self-reports, or administrative databases, which are subject to underreporting and recall bias, as mentioned above. Similarly, EMRs do not capture individuals who are experiencing homelessness or housing instability who do not interact with the healthcare system, which introduces reporting bias. However, the exclusion of these individuals would bias the findings toward the null. Nevertheless, these limitations of the included studies further limit the generalizability of our systematic review.

Conclusions and implications

To collect more robust data on the prevalence of housing instability during pregnancy and its association with adverse pregnancy outcomes or perinatal healthcare utilization, multiple areas must be addressed. First, a standardized definition of housing instability must exist. Our results must be interpreted with caution because of the heterogeneity of definitions of housing instability. Second, an evidence-based measure of housing instability incorporating the heterogeneity of the exposure is warranted to accurately identify the prevalence of housing instability among pregnant people. Third, with rising rates of housing instability because of the financial impact of COVID-19,4,5 research that is specifically focused on defining, measuring, and prospectively documenting housing instability during pregnancy is imperative to better understand this social determinant of perinatal health. These steps are crucial to improve future research and subsequent policy efforts regarding housing status as a social determinant of perinatal health.

This systematic review identified consistent evidence of the relationship between housing instability and adverse pregnancy outcomes. However, our review demonstrated a lack of research on the full spectrum of housing instability and limited research on the breadth and depth of maternal outcomes. In addition, housing instability and homelessness were heterogeneously defined. The evaluation and development of a standardized definition and measurement of housing instability that could be used in further investigation of perinatal health is essential.

Supplementary Material

AJOG MFM at a Glance.

Why was this study conducted?

Housing status is a key social determinant of health and has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, housing instability during pregnancy is an understudied social determinant of perinatal health.

Key findings

Significant heterogeneity in the definitions of housing instability limits the interpretations of the current literature on housing instability during pregnancy. Housing instability during pregnancy was significantly associated with adverse perinatal outcomes, such as preterm birth, low birthweight neonates, neonatal intensive care unit admission, and delivery complications.

What does this add to what is known?

The evaluation and development of a standardized definition and measurement of housing instability among pregnant individuals is warranted to conduct and assess future interventions targeted to housing instability during pregnancy.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

This systematic review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews under identifier CRD42020219945.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100477.

Contributor Information

Julia D. DiTosto, Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL.

Kai Holder, Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL.

Elizabeth Soyemi, Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL.

Molly Beestrum, Galter Health Sciences Library & Learning Center, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL.

Lynn M. Yee, Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cutts DB, Coleman S, Black MM, et al. Homelessness during pregnancy: a unique, time-dependent risk factor of birth outcomes. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:1276–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richards R, Merrill RM, Baksh L. Health behaviors and infant health outcomes in homeless pregnant women in the United States. Pediatrics 2011;128:438–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henry M, Watt R, Rosenthal L, Shivji A. The 2017 Annual homeless assessment report (AHAR) to congress.The US Department of Housing and Urban Development; Office of Community Planning and Development; 2017. Available at: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2017-AHAR-Part-1.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Housing insecurity and the COVID-19 pandemic. Available at: https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_Housing_insecurity_and_the_COVID-19_pandemic.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2020.

- 5.Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Tracking the COVID-19 recession’s effects on food, housing, and employment hardships. COVID hardship watch. Available at: https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/tracking-the-covid-19-recessions-effects-on-food-housing-and. Accessed January 11, 2020.

- 6.Kushel MB, Gupta R, Gee L, Haas JS. Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:71–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor L Housing and health: an overview of the literature. Available at: 10.1377/hpb20180313.396577/full/. Accessed January 11, 2020. [DOI]

- 8.Auerswald CL, Lin JS, Parriott A. Six-year mortality in a street-recruited cohort of homeless youth in San Francisco, California. PeerJ 2016;4:e1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandel M, Sheward R, Ettinger de Cuba S, et al. Unstable housing and caregiver and child health in renter families. Pediatrics 2018;141:e20172199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frederick TJ, Chwalek M, Hughes J, Karabanow J, Kidd S. How stable is stable? Defining and measuring housing stability. J Commun Psychol 2014;42:964–79. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson A, Meckstroth A. “Ancillary services to support welfare-to-work,” Mathematica Policy Research Reports 0aa15be44f8b4caeb7be1a2fe, Mathematica Policy Research; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yee LM, Simon MA, Grobman WA, Rajan PV. Pregnancy as a “golden opportunity” for patient activation and engagement. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021;224:116–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith GN, Saade G, for the SMFM Health Policy Committee. SMFM White Paper: pregnancy as a window to future health. 2020. Available at: www.smfm.org/publications/141-smfm-white-paper-pregnancy-as-a-window-to-future-health. Accessed January 11, 2020.

- 14.Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 729: importance of social determinants of health and cultural awareness in the delivery of reproductive health care. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:e43–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang E, Glazer KB, Howell EA, Janevic TM. Social determinants of pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity in the United States: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2020;135:896–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pantell MS, Baer RJ, Torres JM, et al. Associations between unstable housing, obstetric outcomes, and perinatal health care utilization. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2019;1:100053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Little M, Shah R, Vermeulen MJ, Gorman A, Dzendoletas D, Ray JG. Adverse perinatal outcomes associated with homelessness and substance use in pregnancy. CMAJ 2005;173:615–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark RE, Weinreb L, Flahive JM, Seifert RW. Homelessness contributes to pregnancy complications. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38:139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrews JC, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, et al. GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation-determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:726–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Study quality assessment tools. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed January 11, 2020.

- 21.Khatana SAM, Wadhera RK, Choi E, et al. Association of homelessness with hospital readmissions-an analysis of three large states. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35:2576–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reilly KH, Zimmerman R, Huynh M, Kennedy J, McVeigh KH. Characteristics of mothers and infants living in homeless shelters and public housing in New York City. Matern Child Health J 2019;23:572–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rhee J, Fabian MP, Ettinger de Cuba S, et al. Effects of maternal homelessness, supplemental nutrition programs, and prenatal PM 2.5 on birthweight. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merrill RM, Richards R, Sloan A. Prenatal maternal stress and physical abuse among homeless women and infant health outcomes in the United States. Epidemiol Res Int 2011;2011:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leifheit KM, Schwartz GL, Pollack CE, et al. Severe housing insecurity during pregnancy: association with adverse birth and infant outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:8659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein JA, Lu MC, Gelberg L. Severity of homelessness and adverse birth outcomes. Health Psychol 2000;19:524–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chavkin W, Kristal A, Seabron C, Guigli PE. The reproductive experience of women living in hotels for the homeless in New York City. N Y State J Med 1987;87:10–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pantell MS, Baer RJ, Torres JM, et al. Associations between unstable housing, obstetric outcomes, and perinatal health care utilization. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2019;1:100053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carrion BV, Earnshaw VA, Kershaw T, et al. Housing instability and birth weight among young urban mothers. J Urban Health 2015;92:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LaGuardia KD, Druzin ML, Eades C. Maternity shelter care for adolescents: its effect on incidence of low birth weight. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989;161:303–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tucker CM, Berrien K, Menard MK, et al. Predicting preterm birth among women screened by North Carolina’s pregnancy medical home program. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:2438–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Housing instability. Available at https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health/interventions-resources/housing-instability. Accessed January 11, 2020.

- 33.Giano Z, Williams A, Hankey C, Merrill R, Lisnic R, Herring A. Forty years of research on predictors of homelessness. Community Ment Health J 2020;56:692–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chhabra M, Sorrentino AE, Cusack M, Dichter ME, Montgomery AE, True G. Screening for housing instability: providers’ reflections on addressing a social determinant of health. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34:1213–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.D’Alton ME, Friedman AM, Bernstein PS, et al. Putting the ”M” back in maternal-fetal medicine: a 5-year report card on a collaborative effort to address maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221:311–317.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.