Abstract

Human papillomavirus is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the world and had been linked to both anogenital and oropharyngeal cancers. It causes nearly 100% of cervical cancers and an increasing portion of oropharyngeal cancers. The geographical burden of cervical HPV infection and associated cancers is not uniform and is mainly found in low middle income countries in South America, Africa, and Asia. However, HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer is rapidly becoming more prevalent in high middle income countries. With the development of vaccines which prevent HPV infection, the World Health Organization has designated the extirpation of HPV and its associated cancers a priority. Countries that have implemented adequate vaccine programs have shown a decrease in HPV prevalence. Understanding the epidemiology of HPV and its associated cancers is fundamental in improving vaccine programs and other health programs.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections in the world, with greater than 80% of people infected at some point in their lifetime.1 Numerous strains of HPV (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58 and 59) are oncogenic, causing anogenital and oropharyngeal cancers.2 While most individuals will clear an HPV infection within one to two years, roughly 10% to 20% of infected women will have persistent infection.3 Such persistent oncogenic infection is the cause of nearly 100% of cervical cancers, a significant driver of other anogenital cancers, and increasingly a cause of squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx (OPSCC).4,5

HPV causes several forms of anogenital cancers aside from cervical cancer including vulvar, penile, and anal cancers.6 However, the population level impact of these cancers is small when compared to cervical cancer. It is estimated that there are 60,000 incident non-cervical anogenital cancers per year, significantly less than the half a million incident cervical cancers worldwide (Fig. 1).7 Compounding the effect of cervical cancer is that it has significantly greater years of life lost per mortality than many other cancers because of its younger age of onset.8

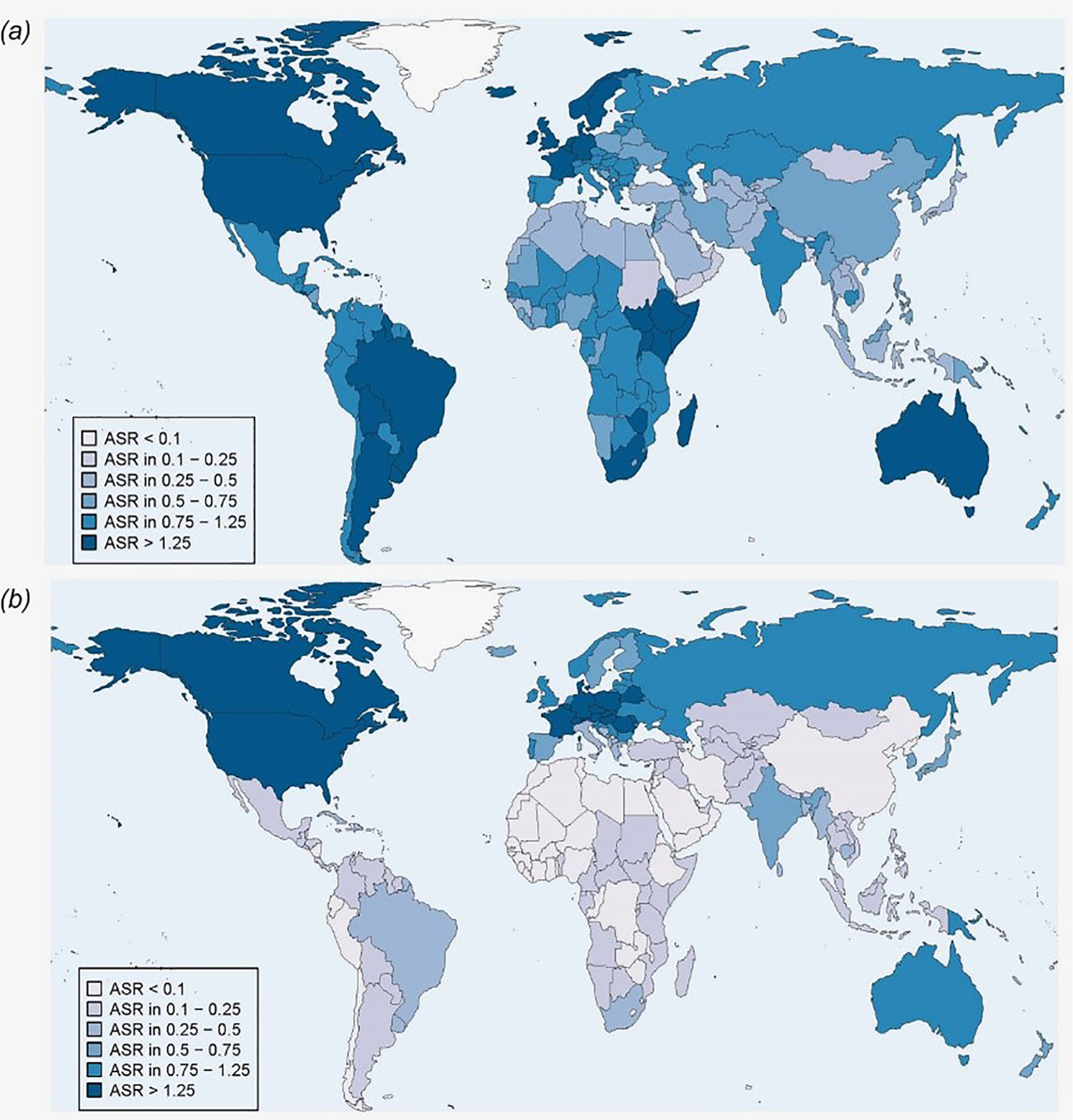

Figure 1.

Age standardized (world) incidence rates (per 100,000) of cancer cases attributable to HPV in 2012, both sexes. Panel (A) Anogenital cancer cases (vulvar, vaginal, anal and penile). Panel (B) Head and neck cancer cases (oropharynx, oral cavity and larynx).From Martel et al. International Journal of Cancer, Volume: 141, Issue: 4, Pages: 664–670, First published: 01 April 2017, DOI: (10.1002/ijc.30716)

While most HPV-associated cancers are cervical, in certain parts of the world there is a growing epidemic in HPV driven OPSCC. Oral HPV infection is acquired by oral-genital infection and can lead to persistent infection.9 The unique histology of both the cervix and the oropharynx help to explain their propensity for infection by HPV. The cervix represents a transition zone between the squamous cells of the vaginal epithelium and the columnar epithelium of the uterus, and after abrasion of this area, the virus has access to the basement membrane of the tissue allowing for infection.10 The oropharynx contains unique lymphoid tissue, known as Waldeyer’s ring. The palatine tonsils are part of this ring and have invaginations or crypts, which are covered with a reticulated epithelium. This epithelium facilitates the transmission of lymphocytes and antigen presenting cells as part of the immune system, but it also allows HPV to access the basement membrane of the tissue in a manner similar to the cervix and can lead to malignancy.11,12

This article will explore the epidemiology of HPV as it relates to both cervical and oropharyngeal cancer and the prevalence of both cervical and oropharyngeal-related “oral” HPV infections. While global statistics about HPV and its associated malignancies show the magnitude of the disease, its burden is not equally distributed (Fig. 2).7 This heterogeneity is in part due to the introduction of routine cervical cancer screening in high middle income countries (HMIC), which has reduced the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer. However, in low middle income countries (LMIC) that lack the resources to implement such screening programs the incidence and mortality have either increased or remained virtually unchanged.13 In addition to screening, the development of HPV vaccines in 2006 has/will drastically alter the epidemiology of HPV infection, as well as its associated cancers. While over 200 million doses have been given, there is still a significant burden of infection and the epidemiology of the disease should continue to be studied to facilitate public health efforts.14

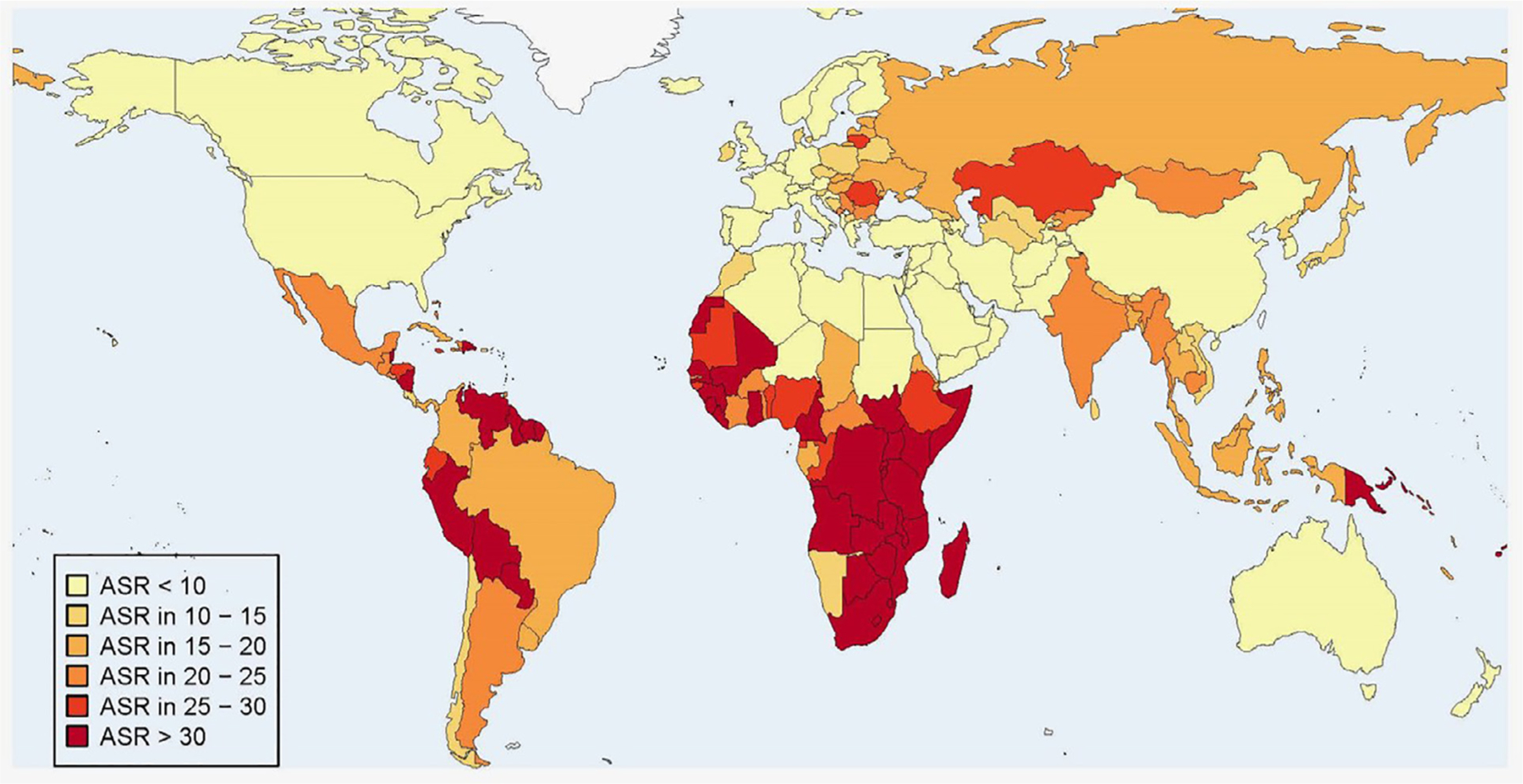

Figure 2.

Age standardized (world) incidence rates (per 100,000) of cervical cancer cases attributable to HPV in 2012. From Martel et al. International Journal of Cancer, Volume: 141, Issue: 4, Pages: 664–670, First published: 01 April 2017, DOI: (10.1002/ijc.30716)

Worldwide HPV Infection and HPV Associated Cancers

The worldwide prevalence of cervical HPV infection is estimated to be 11.7%(95% CI:11.6%−11.7%) in women with normal cytological findings and is significantly higher for women with abnormal cytology.15 The age distribution of HPV infection shows an early peak of prevalence in the teens and twenties and then a decrease over time; however, some countries show a second peak later in life.16 Globally, the most common HPV strains infecting women with normal cytology are HPV 16, 52, 31, and 53; for cervical cancer the major strains are HPV 16 and 18 with over 55% and 14% of cervical cancers associated with each respectively.17

The best overall estimates when studying the global impact of HPV come from the GLOBOCAN 2018 data. The methodology behind this data has been described previously.18 As of 2018, the overall age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) for HPV attributed cancers was 8.0 per 100,000 with a total of 690,00 cases of cancer worldwide.19 It is important to recognize that the majority of cancers associated with HPV affect women and therefore sex-stratified estimates are considered. As such, the global ASIR rate for cervical cancer is 13.1 with a mortality rate of 6.9 per 100,000.20 Overall, cervical cancer is the second most common cancer for women under 50 and fourth most common cancer for women of any age.21 Over the past 30 years, HPV has become the major driver of OPSCC in HMIC countries and is now the main driver of HPV related cancer having overtaken cervical cancer (Fig. 3). However, in LMIC countries there is little evidence to support a similar trend. In addition, while some oral cavity tumors are HPV positive it is still debated if HPV is a major driver of these.

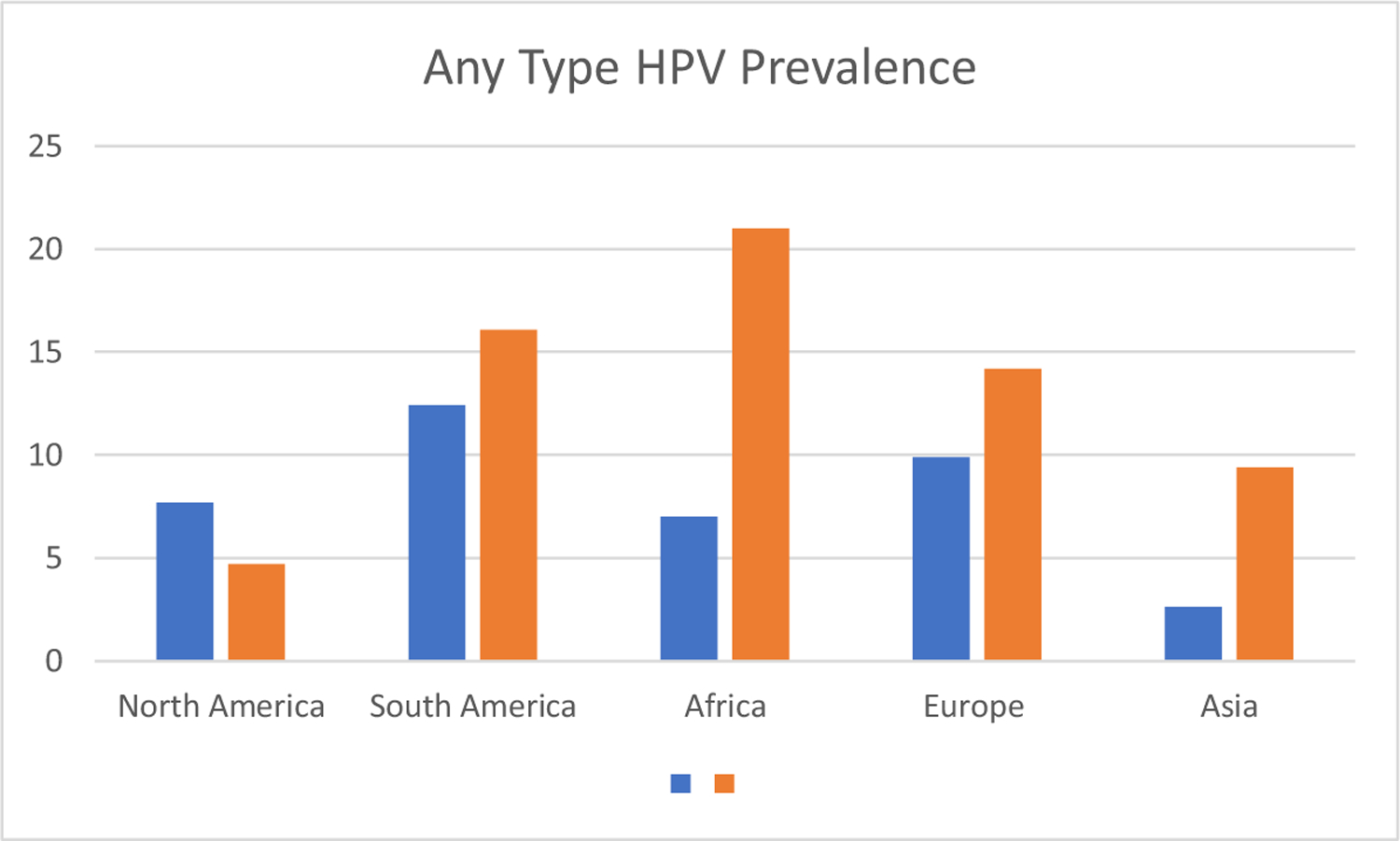

Figure 3.

Percent prevalence of any type HPV grouped by continent.

Data extracted from:

Tam, S., et al., The epidemiology of oral human papillomavirus infection in healthy populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncology, 2018. 82: p. 91–99.

Bruni, L., et al., Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2010. 202(12): p. 1789–1799.

North America

Cervical HPV

The overall prevalence of cervical HPV infection in cytologically normal women in North America ranges from 4% to 20% in various meta-analyses with an age adjusted prevalence of 4.6% (95% CI:4.6%−4.7%) and the highest level of prevalence for women in their 20’s with a steady decrease thereafter.22

Since 2007 the vaccination of young women in the United States has significantly decreased the prevalence of HPV burden. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from two time periods 2003–2006 and 2009–2012 showed a 63% decrease in HPV types covered by vaccine for the 14–19- years old age group and a 34% decrease among women in the 20–24 age group.23 Further studies from 2018 have shown a continued reduction in the prevalence of HPV, with a decrease of 86% among those aged 14–19 and 71% among those aged 20–24 year.24 There is also evidence that vaccination may be inducing a reduction in the prevalence of HPV even in unvaccinated individuals and is possibly evidence of herd immunity.25,26 This decrease in HPV infection in conjunction with successful secondary prevention strategies will lead to a decrease in HPV related malignancies. Already, cervical cancer incidence has decreased among vaccinated populations; a recent study found that there was a 29% decrease in the incidence of cervical cancer for those aged 15–25 and a 13% decrease for those aged 25–34 in the 6 years after the start of vaccination.27

Cervical Cancer

North America has a relatively low ASIR of cervical cancer at 7.1 cases per 100,00 women, almost half the world average.20 Cervical cancer in North America represents just 1.7 % of all new cancers and the mortality for the disease is even lower with only 5,000 women dying of the disease each year, an adjusted mortality rate of only 1.9 deaths per 100,000 women.28 This low mortality rate is believed to be a consequence of the widespread implementation of cervical cancer screening.

Oral & Oropharyngeal HPV

The prevalence of oral HPV infection is North America is estimated to be between 5% and 8% for any HPV type.29–31 Some studies show that older men have a significantly higher burden of infection at roughly 10%.32 Certain populations have a greater prevalence such as those with HIV, with prevalence as high as 40%.33 Other risk factors for increased prevalence, especially oncogenic types of HPV, include number of lifetime oral sexual partners and tobacco use.34–37 Importantly, there is also evidence that the prevalence of oral HPV infection is decreasing with vaccination.38 Comparing oral HPV prevalence to cervical, it is clear that oral HPV infection is becoming more prevalent than cervical and that the population with highest oncogenic prevalence is older rather than younger.

Oropharyngeal Cancer

While the prevalence of oral HPV is relatively low, there is a growing epidemic of HPV driven oropharyngeal cancer. While the overall incidence of head and neck cancer decreased during the latter half of 20th century, there was an increase in the proportion of OPSCC.39,40 There was a also a concomitant increase in OPSCC positive for HPV infection; the rate of HPV-positivity in OPSCC was 16.3% during 1984–1989 and rose to 72.7% during 2000–2004.41 The prevalence of HPV-positive OPSCCC has continued to increase and is estimated to be between 70% and 90%.42,43 The prevalence in Canada showed a similar pattern of increase.44 The ASIR of head and neck cancer attributable to HPV infection in the United States is 1.72 per 100,000, the highest in the world.7 There is also new evidence that the demographics of those affected by HPV-OPSCC is changing. Early in the HPV epidemic for head and neck cancer, individuals were generally younger, white males.43,45,46 Over the past ten years, the prevalence of HPV driven OPSCC has increased markedly among older age groups, shifting the median age higher, and among several different racial groups and in women.47–51

Europe

Cervical HPV Prevalence

Pre-vaccination prevalence of cervical HPV infection in Western Europe were similar those in North America. Northern Europeans countries had a slightly higher prevalence over of 10% (95% CI: 9.8%−10.2%) compared with Southern and Western Europe which had prevalence rates of approximately 9% (95% CI: 8.8%−9.2%).22 Eastern Europe though has significantly higher HPV prevalence of 29.1% (95%CI: 24.3%−34.4%) and 21.4% (95% CI: 22.1%−22.7%).22,52 Though there are significant discrepancies between different countries and between studies in similar countries.53,54 For instance, one study in Hungary had a prevalence of just 5% while another had a prevalence of 21%, though both had similar mean ages of women in the studies.55 Therefore, there appears to be heterogeneity in estimates of cervical HPV prevalence in Europe.

Cervical Cancer

Unlike North America, which has a homogeneous epidemiological profile for cervical cancer, Europe has significant differences between regions. While Western Europe is comparable to North America, with a low incidence of and mortality from cervical cancer, the same is not true for Eastern Europe. Eastern Europe, including Russia, had seen a significant increase in the incidence of cervical cancer and mortality in the past 30 years.56,57 In Eastern Europe, the ASIR for cervical cancer is 16 per 100,000, while the rest of Europe has an ASIR of between 6.8 and 9.5 per 100,000.20 There is a similar difference in mortality from cervical cancer with a mortality rate with Eastern Europe having a rate of 6.1 per 100,000 vs. a rate of 2 for the rest of Europe.20

Oral & Oropharyngeal HPV

The average prevalence in Europe for oral HPV infection of any type was between 6% (95% CI:3.4%−10.5%) and 10% (95% CI: 7.2%−10.5%) in various meta-analyses, slightly higher than estimates in North America.29,30 One of these meta-analyses found that Southern Europe had a higher prevalence than Northern Europe: 9.5% (95% CI: 3.3%−18.1%) compared to 4.9% (95% CI: 0.9%−11.5%).29 A cohort in Sweden had an overall prevalence of 9.3% and prevalence of 7.2% for high risk oral HPV types.58 Unvaccinated groups appear to have a higher prevalence of oral HPV. One study from central Europe showed a difference of 8.8% to 2% prevalence when comparing unvaccinated vs. vaccinated individuals.59 Young, unvaccinated women in Scotland had a 13% prevalence of any oral HPV type.60 Unfortunately, the lack of studies from Eastern Europe prohibit making any conclusions about the effect of Eastern Europe’s high cervical HPV prevalence and its relationship to oral HPV prevalence.

Oropharyngeal Cancer

Europe has also seen an increase in the incidence and prevalence of HPV positive OPSCC. The ASIR for HPV driven head and neck cancers in Europe is high but with some variation. Large western European countries universally have ASIR such as France (1.88), Germany (1.79), and England (0.99). Some Eastern European countries also have high values such as the Czech Republic (1.44), Hungary (3.04), and Slovenia (2.8). Other Eastern European countries ASIRs are lower, such as Macedonia (0.42), Estonia (0.86), and Russia (0.99).7 In addition, many of the eastern European countries have poor data behind these ASIR estimates.

Although lower magnitude than the U.S., in some populations, the incidence of OPSCC has doubled.61 The prevalence of HPV found in oropharyngeal tumors has also increased and is between 50% and 60% depending on population tested.62–65 In some Northern European countries the prevalence is as high as 70%.66 This increase is also present in areas that were previously thought to have lower levels of OPSCC, such as Southern Europe.67,68 Eastern Europe has significantly lower prevalence of HPV-positive OPSCC: 30% or less.69,70 Overall, it appears that Western Europe is following a similar epidemiological path as North America for OPSCC, while Eastern Europe has not reliably seen increases of same magnitude in HPV driven OPSCC.

Africa

Cervical HPV

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has some of the highest burdens of cervical HPV prevalence in the world. In East Africa the prevalence is 33% (95% CI: 30.2%−37.1%), in West Africa it is 29% (95%CI: 18.5%−20.8%), and in Southern Africa it is 17% (95% CI: 15.9%−18.9%); all are above the global average of 11%.22 One of the major issues in SSA is that there is the greater prevalence of HPV co-infection and cervical cancer with women who are HIV positive.71,72 Women with HIV are less likely to clear HPV infections and have a decreased immune response against and so are more likely to develop cervical cancer.73 The high rates of cervical HPV infection in SSA are not seen in North Africa possibly due to either difference in sexual practices or HIV infection. However, the prevalence of HPV in North Africa is increasing and is above the world average, with different meta-analysis placing the overall prevalence between 15% and 21%.74–76

Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer is the leading cause of cancer specific mortality in African women.77 SSA has the highest incidents rates in the world, 7 to 10 times those of HMIC. Overall, there are 90,000 new cases of cervical cancer and 57,000 deaths each year from the disease and in a number of countries the burden of disease is increasing.78 While data is sparse, several countries have shown an unfortunate increase in cervical cancer rates over the past several decades.79,80 Most countries in SSA do not have the resources to promote robust screening programs, as such cervical cancer is a significant health problem for women in these countries.81 While there are high levels of HPV in SSA and concordantly high levels of cervical cancer, over the past ten years that has also been a large effort to develop national immunization programs. Two countries stand out, Rwanda and Burundi, where vaccination rates of adolescent girls are greater than 89%, and have already shown a decrease in HPV prevalence after implementation.82

Oral & Oropharyngeal HPV

There is a lack of studies evaluating oral HPV prevalence in Africa.29 Only one meta-analysis included multiple results from Africa, and all of those results were from South Africa; the overall prevalence was roughly 7%(95%CI: 5.3% to 8.6%) for any HPV type.30 There was significant heterogeneity among these studies both in terms of prevalence as well as the patient populations that the studies drew from. Some studies had rates as high as 20%−25% in more at risk populations.83,84 Other studies have found lower rates between 1% and 5%.85–87 Few other studies have look at the prevalence of oral HPV infection in other African countries, but they generally show low rates.88 With the paucity of studies and their disparate results, it is difficult to interpret the broad ranges of prevalence estimates of HPV in Africa. However, given that there lower rate of participation in oral sex, the lower prevalence in oropharyngeal HPV found in these studies is logical in spite of the high prevalence of cervical HPV infection.89

Oropharyngeal Cancers

Studies regarding HPV tumor status in OPSCC in these regions are limited. However, from the limited studies available there seems to be a distinct lack of prevalence and low incidence of HPV-positive OPSCC in a variety of countries including Cameroon, Mozambique, Senegal, and Nigeria.88,90–93 The ASIR of HPV attributable head and neck cancers in African countries is low: South Africa has the highest ASIR of the continent with 0.28 per 100,000; most other countries in Africa have an ASIR less than half that.7 In regards to prevalence, there are two possible exceptions to this trend: South Africa and Sudan. Some of the studies from South Africa show a low prevalence of HPV in OPSCC (5%) while others show nearly all OPSCC are HPV-positive (94%).91,94 Interestingly, one study from the Sudan showed 65% HPV-positivity in OPSCC; however, other studies from that region recorded 25% prevalence.95,96 The reason for the discrepancy between the high incident rates of cervical HPV and a lack of OPSCC may be due to different sexual behaviors in SSA, specifically lower oral rather than genital exposure to HPV, as opposed to other countries which have a growing proportion of HPV related cancer found the in the oropharynx.88

Asia & Oceania

Cervical HPV

Overall, any type HPV prevalence for women with normal cytology is estimated at 9.4% (95% CI: 9.2% to 9.6%), with the highest prevalence in Oceania, Mongolia, and Korea.17,52 A recent meta-analysis of HPV, any type, in China found a prevalence of 11% to 15% for cytologically normal women.97 Australia’s prevalence is 9.25%; prior to vaccination its prevalence was 21% in cytologically normal females.98,99 Australia has also shown significant reductions in infection and dysplasia after implementing vaccination program.100 India has a prevalence rate of only 5% in women with normal cytology though certain populations have a prevalence of twice that. 101,102 It should be noted that this is a relatively low prevalence rate given the high ASIR of cervical cancer in India. Complicating India’s efforts to decrease HPV infection was that its early vaccine programs were suspended due to several deaths in 2010 but it has since restarted and shows promise.103

Cervical Cancer

Asian accounts for the greatest number of cervical cancer cases in the world. While several HMIC form this region have low ASIR of cervical cancer, such as Australia (6), New Zealand (6), and Korea (8.4); such a tendency was not uniform as Japan, had a relatively high ASIR of 14.7 per 100,000. Several other countries in the area had high ASIR including Mongolia (23.5) Myanmar (21.5), and Papua New Guinea (29.1).17 In spite of these high incidence rates, most countries in Asia have decreasing incidence of cervical cancer.13

Two countries deserve special commentary: China and India. Despite being classified as a LMIC, China has a relatively low rate of cervical cancer with ASIR of 10.7 cases per 100,000 women.20 However, the incident rate in China is increasing.104 Two possible explanations for this are a lack of screening for cervical cancer in Chinese women and the late approval of and low usage of HPV vaccines.105,106 India accounts for nearly a fifth of the cervical cancer cases in the world.103 It has a ASIR of 14.7 per 100,000.17. Its incidence is falling by roughly 1 to 2 % per year.107 Still, its adjusted mortality rate is nearly 1.5 times the world average.17 Given the large populations of these two countries the continued progress in public health programs will be crucial in helping eliminate HPV driven cancers.

Oral & Oropharyngeal HPV

The prevalence of any type oral HPV infection is 2.6% (95%CI:0.7%−6.8%) in Asia and 4.6% (95% CI: 2.3%−6.8%) for Oceania.30 Only two studies looked at oral HPV prevalence in India and found rates of 0% and 4%.29 In Japan, the prevalence was variable with a some studies reporting less than 1% 108 while another reported 5.7%.109 In Australia, the prevalence was 2.3% in a cohort of university students.110 Women in New Zealand showed a similar prevalence rate of 3.2%, though less than 1% had high risk HPV types.111 China had low prevalence for any HPV at 3% and for high risk types a prevalence of less than 1%.112,113 Given the heterogeneity of the region, there are few conclusions that can be drawn from this data other than that more studies are needed in order to better understand the epidemiology of oral HPV infection in Asia.

Oropharyngeal Cancer

There were significant differences in the ASIR of HPV attributable head and neck cancer between Asian and Oceania. Large Asian countries had lower ASIR; China’s ASIR was 0.07 and India’s was 0.63, while Australia was 0.95.7 There are also differences in HPV prevalence in OPSCC in Asia and Oceania. In Australia, there was an increase from 20% to 63% between 1987 and 2010.114 In recent meta-analysis the highest rate of prevalence in Asia and Oceania were found in Korea (69%) and Australia (49%), while there is a less prevalence of HPV in OPSCC in India (25%) and Japan (40%). It also appears that in countries in Southeast Asia, such as India and Thailand, the prevalence of HPV in OPSCC is increasing.115–117 Still, this trend is not present in all countries. A recent meta-analysis from China showed a rate of 30% HPV-positive OPSCC.118 As such it appears that in more westernized nations, such as Australia and Korea there, is an increase in HPV-positive OPSCC, but this trend is not present in all Asian countries, including China and its large population.

South America & Latin America

Cervical HPV Prevalence

HPV prevalence in Latin American populations is high at 12.3% (95% CI: 11.2%−13.4%) for South America and 20.4% (95% CI:19.3%−21.4%) for Central America.52 Other studies which combined the 2 regions found similarly high prevalence of 16.1%(95% CI: 15.8%−16.4%).22 However, there is significant variation between different countries and a lack of studies overall. The age distribution of infection in most Latin American countries shows a U shaped curve where in there is a high prevalence at a young age and then a decrease with a second peak in the mid-fifties.119–122 While secondary screening programs have not decreased the incidence and mortality of HPV driven cancers to the same degree as other more developed areas, the current vaccination programs in numerous countries show encouraging results in decreasing prevalence of HPV.123

Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer is a significant risk to women’s health in the Latin America and South America. The total number of cervical cancers diagnosed in 2018 were estimated at 56,000 or 10% of the global burden, most of these being in South America. The most recent ASIR for these regions respectively are 13, and 15.2 per 100,000; and there is significant mortality associated with them.20 There is also significant heterogeneity in the incidence of cervical cancer with some countries having incident rates of cervical cancer closer to those of Sub-Saharan Africa, at nearly 30 per 100,000.124 Overall, the incidence and mortality for cervical cancer is decreasing in almost every country in Latin and South America.125 The only exception to these decreasing trends are in Argentina and Uruguay where the incidence has increased over the past 20 years.13,126

Oral & Oropharyngeal HPV Infection

Meta-analyses of HPV prevalence in Latin and South America show disparate results; one found a prevalence of 12% (95% CI: 5.7% to 19.1%) while a later study found it at 4.6% (95% CI:2.2% to 7.7%).29,30 One explanation for this discrepancy is that the number of studies included in the second meta-analysis had more than doubled. It should also be noted that all of the studies which had greater than 10% prevalence the patients were drawn from convenient outpatient samples and case matched controls which could artificially inflate the prevalence.127 The studies for these meta-analyses are mainly from Brazil which may introduce bias. However, other studies from South America show a lower prevalence with 3% for Argentina and 6% for Peru.128,129 Overall, the higher rates seen in some of these studies is likely an effect of publication bias and the true prevalence of oral HPV in the region is lower.

Oropharyngeal Cancer

There is a lack of studies looking at HPV-positive OPSCC in South and Latin America, and those that are published are often contradictory. Most of the literature is from Brazil and while some studies report HPV prevalence in OPSCC of 15% to 20%, other studies found only 4%.130–133 Generally, there does not appear to be an increase of OPSCC incidence in South America.134 The ASIR for HPV attributable head and neck cancer in South America is low. Brazil, the most populous country, had an ASIR of 0.34 per 100,000; other large countries also had low values, such as Colombia(0.12) and Argentina (0.14).7 In Colombia, studies show paradoxically that HPV is more often found in oral cavity tumors rather than oropharyngeal tumors 23% vs. 13%.135 Peru did not show an increased incidence and instead has had significant increase in non-HPV related cancer and only moderate increase in HPV OPSC among older males.136 Other Latin American countries also show a low prevalence for the disease in tumors.70 This heterogeneity is not limited to single country studies, one large meta-analysis found that Latin and South America had the least prevalence HPV positive-OPSCC, while an international cross-sectional study found that Latin and South American had the highest.137,138 More research is needed to properly assess the effect of HPV on OPSCC in Latin and South America.

Conclusion

Cervical cancer represents a significant cause of mortality among women, especially those in LMIC in SSA, East Asia, and South America. Vaccination programs will decrease the burden of HPV in cytologically normal women, which will help to decrease persistent infection and eventually decrease the rates of cervical and other anogenital cancer rates. While the effects of the vaccine are promising, there is significant lag time before onset of the disease, and it will still be decades before there is adequate inoculation to decrease to the rates of cervical cancer. Efforts should be made both to increase vaccination among at risk populations, as well as to improve screening programs.

There is clear evidence that in North America, Australia, and Western Europe, most OPSCC cancer are now caused by HPV. There is also some evidence that this trend is also present in certain Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand and India. There does not appear to be an increase in most African countries, and given the lack of studies, it is unclear if there is a similar trend in Latin and South America. A high prevalence of cervical HPV may not directly correlate to high rate of HPV-positive OPSCC, and other factors such as cultural values and sexual practices likely influence the trends seen in HPV driven OPSCC.

Funding:

P50DE019032 and 5T32DC000027–29

References

- 1.Winer RL, Koutsky LA: The Epidemiology of Human Papillomavirus Infections. In: Shah TERKV (ed). Cercival Cancer: From Etiology to Prevention, Dordrecht: Springer, 143–187, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. : Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. The Journal of pathology 189:12–19, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moscicki AB, Shiboski S, Broering J, et al. : The natural history of human papillomavirus infection as measured by repeated DNA testing in adolescent and young women. The Journal of pediatrics 132:277–284, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muñoz N, Bosch FX, De Sanjosé S, et al. : Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. New England journal of medicine 348:518–527, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallbillich JJ, Rhodes H, Milbourne A, et al. : Vulvar intraepithelial neo-plasia (VIN 2/3): comparing clinical outcomes and evaluating risk factors for recurrence. Gynecologic oncology 127:312–315, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moscicki A-B, Schiffman M, Burchell A, et al. : Updating the Natural History of Human Papillomavirus and Anogenital Cancers. Vaccine 30:F24–F33, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Martel C, Plummer M, Vignat J, Franceschi S: Worldwide burden of cancer attributable to HPV by site, country and HPV type. International journal of cancer 141:664–670, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang BH, Bray FI, Parkin DM, Sellors JW, Zhang ZF: Cervical cancer as a priority for prevention in different world regions: an evaluation using years of life lost. International journal of cancer 109:418–424, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drake VE, Fakhry C, Windon MJ, et al. : Timing, number, and type of sexual partners associated with risk of oropharyngeal cancer. Cancer 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts JN, Buck CB, Thompson CD, et al. : Genital transmission of HPV in a mouse model is potentiated by nonoxynol-9 and inhibited by carrageenan. Nature medicine 13:857–861, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pai SI, Westra WH: Molecular pathology of head and neck cancer: implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Annu Rev Pathol 4:49–70, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, Franceschi S: Human Papillomavirus Types in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas Worldwide: A Systematic Review. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 14:467–475, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaccarella S, Lortet-Tieulent J, Plummer M, Franceschi S, Bray F: Worldwide trends in cervical cancer incidence: impact of screening against changes in disease risk factors. Eur J Cancer 49:3262–3273, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garland SM, Kjaer SK, Muñoz N, et al. : Impact and effectiveness of the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: a systematic review of 10 years of real-world experience. Reviews of Infectious Diseases 63:519–527, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clifford G, Gallus S, Herrero R, et al. : Worldwide distribution of human papillomavirus types in cytologically normal women in the International Agency for Research on Cancer HPV prevalence surveys: a pooled analysis. The Lancet 366:991–998, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franceschi S, Herrero R, Clifford GM, et al. : Variations in the age-specific curves of human papillomavirus prevalence in women world-wide. International journal of cancer 119:2677–2684, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruni L, Barrionuevo-Rosas L, Albero G, Serrano B: ICO/IARC Information Centre on Papillomavirus and Cancer (HPV Information Centre 17 June 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, et al. : Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. International journal of cancer 144:1941–1953, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Martel C, Georges D, Bray F, Ferlay J, Clifford GM: Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: a worldwide incidence analysis. The Lancet Global health 8:e180–ee90, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arbyn M, Weiderpass E, Bruni L, et al. : Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis. The Lancet Global health 8:e191–e203, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serrano B, Brotons M, Bosch FX, Bruni L: Epidemiology and burden of HPV-related disease. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 47:14–26, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruni L, Diaz M, Castellsagué M, Ferrer E, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S: Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. Journal of Infectious Diseases 202:1789–1799, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markowitz LE, Liu G, Hariri S, Steinau M, Dunne EF, Unger ER: Prevalence of HPV After Introduction of the Vaccination Program in the United States. Pediatrics 137, 2016:e20151968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McClung NM, Lewis RM, Gargano JW, Querec T, Unger ER, Markowitz LE: Declines in Vaccine-Type Human Papillomavirus Prevalence in Females Across Racial/Ethnic Groups: Data From a National Survey. J Adolesc Health 65:715–722, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kahn JA, Brown DR, Ding L, et al. : Vaccine-type human papillomavirus and evidence of herd protection after vaccine introduction. Pediatrics 130:e249–e256, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berenson AB, Hirth JM, Chang M: Change in human papillomavirus prevalence among US women aged 18−59 years, 2009−2014. Obstetrics & Gynecology 130:693–701, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo F, Cofie LE, Berenson AB: Cervical Cancer Incidence in Young U.S. Females After Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Introduction. Am J Prev Med 55:197–204, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arbyn M, Xu L, Simoens C, Martin-Hirsch PP: Prophylactic vaccination against human papillomaviruses to prevent cervical cancer and its precursors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 5, 2018:Cd009069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mena M, Taberna M, Monfil L, et al. : Might oral human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in healthy individuals explain differences in HPV-Attributable fractions in oropharyngeal cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of infectious diseases 219:1574–1585, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tam S, Fu S, Xu L, et al. : The epidemiology of oral human papillomavirus infection in healthy populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral oncology 82:91–99, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanders AE, Slade GD, Patton LL: National prevalence of oral HPV infection and related risk factors in the U.S. adult population. Oral Diseases 18:430–441, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gillison ML, Broutian T, Pickard RK, et al. : Prevalence of oral HPV infection in the United States, 2009–2010. Jama 307:693–703, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beachler DC, Weber KM, Margolick JB, et al. : Risk factors for oral HPV infection among a high prevalence population of HIV-positive and at-risk HIV-negative adults. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers 21:122–133, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D’Souza G, Agrawal Y, Halpern J, Bodison S, Gillison ML: Oral sexual behaviors associated with prevalent oral human papillomavirus infection. The Journal of infectious diseases 199:1263–1269, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kreimer AR, Pierce Campbell CM, Lin HY, et al. : Incidence and clearance of oral human papillomavirus infection in men: the HIM cohort study. Lancet (London, England) 382:877–887, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.D’Souza G, McNeel TS, Fakhry C: Understanding personal risk of oropharyngeal cancer: risk-groups for oncogenic oral HPV infection and oropharyngeal cancer. Annals of Oncology 28:3065–3069, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fakhry C, Gillison ML, D’Souza G: Tobacco Use and Oral HPV-16 Infection. Jama 312:1465–1467, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaturvedi AK, Graubard BI, Broutian T, et al. : Effect of Prophylactic Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination on Oral HPV Infections Among Young Adults in the United States. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 36:262–267, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carvalho AL, Nishimoto IN, Califano JA, Kowalski LP: Trends in incidence and prognosis for head and neck cancer in the United States: a site-specific analysis of the SEER database. International journal of cancer 114:806–816, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ernster JA, Sciotto CG, O’Brien MM, et al. : Rising incidence of oropharyngeal cancer and the role of oncogenic human papilloma virus. The Laryngoscope 117:2115–2128, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. : Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 29:4294–4301, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Young D, Xiao CC, Murphy B, Moore M, Fakhry C, Day TA: Increase in head and neck cancer in younger patients due to human papillomavirus (HPV). Oral oncology 51:727–730, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.D’Souza G, Westra WH, Wang SJ, et al. : Differences in the Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancers by Sex, Race, Anatomic Tumor Site, and HPV Detection Method. JAMA Oncol 3:169–177, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nichols AC, Palma DA, Dhaliwal SS, et al. : The epidemic of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer in a Canadian population. Current oncology (Toronto, Ont) 20:212–219, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Settle K, Posner MR, Schumaker LM, et al. : Racial survival disparity in head and neck cancer results from low prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in black oropharyngeal cancer patients. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa) 2:776–781, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rettig EM, D’Souza G: Epidemiology of head and neck cancer. Surgical oncology clinics of North America 24:379–396, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zandberg DP, Liu S, Goloubeva OG, Schumaker LM, Cullen KJ: Emergence of HPV16-positive oropharyngeal cancer in Black patients over time: University of Maryland 1992–2007. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa) 8:12–19, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Faraji F, Rettig EM, Tsai HL, et al. : The prevalence of human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal cancer is increasing regardless of sex or race, and the influence of sex and race on survival is modified by human papillomavirus tumor status. Cancer 125:761–769, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zumsteg ZS, Cook-Wiens G, Yoshida E, et al. : Incidence of Oropharyngeal Cancer Among Elderly Patients in the United States. JAMA Oncol 2:1617–1623, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rettig EM, Zaidi M, Faraji F, et al. : Oropharyngeal cancer is no longer a disease of younger patients and the prognostic advantage of Human Papillomavirus is attenuated among older patients: Analysis of the National Cancer Database. Oral oncology 83:147–153, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Windon MJ, D’Souza G, Rettig EM, et al. : Increasing prevalence of human papillomavirus−positive oropharyngeal cancers among older adults. Cancer 124:2993–2999, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Sanjosé S, Diaz M, Castellsagué X, et al. : Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 7:453–459, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alexandrova YN, Lyshchov AA, Safronnikova NR, Imyanitov EN, Hanson KP: Features of HPV infection among the healthy attendants of gynecological practice in St. Petersburg, Russia. Cancer Lett 145:43–48, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rogovskaya SI, Shabalova IP, Mikheeva IV, et al. : Human papillomavirus prevalence and type-distribution, cervical cancer screening practices and current status of vaccination implementation in Russian Federation, the Western countries of the former Soviet Union, Caucasus region and Central Asia. Vaccine 31(Suppl 7):H46–H58, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poljak M, Seme K, Maver PJ, et al. : Human papillomavirus prevalence and type-distribution, cervical cancer screening practices and current status of vaccination implementation in Central and Eastern Europe. Vaccine 31(Suppl 7):H59–H70, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kesic V, Poljak M, Rogovskaya S: Cervical cancer burden and prevention activities in Europe. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 21:1423–1433, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A: Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68:394–424, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Du J, Nordfors C, Ahrlund-Richter A, et al. : Prevalence of oral human papillomavirus infection among youth. Sweden. Emerg Infect Dis 18:1468–1471, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Malerova S, Hejtmankova A, Hamsikova EVA, et al. : Prevalence and Risk Factors for Oral HPV in Healthy Population, in Central Europe. Anticancer research 40:1597, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dalla Torre D, Burtscher D, Sölder E, Widschwendter A, Rasse M, Puelacher W: The impact of sexual behavior on oral HPV infections in young unvaccinated adults. Clinical oral investigations 20:1551–1557, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schache AG, Powell NG, Cuschieri KS, et al. : HPV-Related Oropharynx Cancer in the United Kingdom: An Evolution in the Understanding of Disease Etiology. Cancer Res 76:6598–6606, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stjernstrøm KD, Jensen JS, Jakobsen KK, Grønhøj C, von Buchwald C: Current status of human papillomavirus positivity in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in Europe: a systematic review. Acta oto-laryngologica 139:1112–1116, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carlander AF, Grønhøj Larsen C, Jensen DH, et al. : Continuing rise in oropharyngeal cancer in a high HPV prevalence area: A Danish population-based study from 2011 to 2014. Eur J Cancer 70:75–82, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zamani M, Grønhøj C, Jensen DH, et al. : The current epidemic of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer: An 18-year Danish population-based study with 2,169 patients. Eur J Cancer 134:52–59, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abogunrin S, Di Tanna GL, Keeping S, Carroll S, Iheanacho I: Prevalence of human papillomavirus in head and neck cancers in European populations: a meta-analysis. BMC cancer 14:968, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fossum GH, Lie AK, Jebsen P, Sandlie LE, Mork J: Human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in South-Eastern Norway: prevalence, genotype, and survival. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology: official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS): affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery 274:4003–4010, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mena M, Frias-Gomez J, Taberna M, et al. : Epidemiology of human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal cancer in a classically low-burden region of southern. Europe. Scientific reports 10:13219, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Melchers LJ, Mastik MF, Samaniego Cameron B, et al. : Detection of HPV-associated oropharyngeal tumours in a 16-year cohort: more than meets the eye. British journal of cancer 112:1349–1357, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brauswetter D, Birtalan E, Danos K, et al. : p16(INK4) expression is of prognostic and predictive value in oropharyngeal cancers independent of human papillomavirus status: a Hungarian study. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology: official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS): affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery 274:1959–1965, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ribeiro KB, Levi JE, Pawlita M, et al. : Low human papillomavirus prevalence in head and neck cancer: results from two large case−control studies in high-incidence regions. International Journal of Epidemiology 40:489–502, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ndizeye Z, Vanden Broeck D, Lebelo RL, Bogers J, Benoy I, Van Geertruyden JP: Prevalence and genotype-specific distribution of human papillomavirus in Burundi according to HIV status and urban or rural residence and its implications for control. PloS one 14, 2019: e0209303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Castle PE, Varallo JE, Bertram MM, Ratshaa B, Kitheka M, Rammipi K: High-risk human papillomavirus prevalence in self-collected cervico-vaginal specimens from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative women and women living with HIV living in Botswana. PloS one 15, 2020:e0229086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stelzle D, Tanaka LF, Lee KK, et al. : Estimates of the global burden of cervical cancer associated with HIV. The Lancet Global health 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Obeid DA, Almatrrouk SA, Alfageeh MB, Al-Ahdal MNA, Alhamlan FS: Human papillomavirus epidemiology in populations with normal or abnormal cervical cytology or cervical cancer in the Middle East and North Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Public Health 13:1304–1313, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Seoud M: Burden of Human Papillomavirus−Related Cervical Disease in the Extended Middle East and North Africa—A Comprehensive Literature Review. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease 16:106–120, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ali MAM, Bedair RN, Abd El Atti RM: Cervical high-risk human papillomavirus infection among women residing in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries: Prevalence, type-specific distribution, and correlation with cervical cytology. Cancer Cytopathology 127:567–577, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cohen PA, Jhingran A, Oaknin A, Denny L: Cervical cancer. The Lancet 393:169–182, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Black E, Richmond R: Prevention of Cervical Cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Advantages and Challenges of HPV Vaccination. Vaccines (Basel) 6, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chokunonga E, Borok M, Chirenje Z, Nyakabau A, Parkin D: Trends in the incidence of cancer in the black population of Harare, Zimbabwe 1991−2010. International journal of cancer 133:721–729, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wabinga HR, Nambooze S, Amulen PM, Okello C, Mbus L, Parkin DM: Trends in the incidence of cancer in Kampala, Uganda 1991−2010. International journal of cancer 135:432–439, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sankaranarayanan R, Anorlu R, Sangwa-Lugoma G, Denny LA: Infrastructure requirements for human papillomavirus vaccination and cervical cancer screening in sub-Saharan Africa. Vaccine 31(Suppl 5): F47–F52, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Baussano I, Sayinzoga F, Tshomo U, et al. : Impact of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination, Rwanda and Bhutan. Emerging Infectious Disease journal 27:1, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vogt SL, Gravitt PE, Martinson NA, Hoffmann J, D’Souza G: Concordant Oral-Genital HPV Infection in South Africa Couples: Evidence for Transmission. Frontiers in oncology 3:303, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Richter KL, Van Rensburg EJ, Van Heerden WFP, Boy SC: Human papilloma virus types in the oral and cervical mucosa of HIV-positive South African women prior to antiretroviral therapy. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine 37:555–559, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Davidson CL, Richter KL, Van der Linde M, Coetsee J, Boy SC: Prevalence of oral and oropharyngeal human papillomavirus in a sample of South African men: a pilot study. South African medical journal = Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde 104:358–361, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chikandiwa A, Pisa PT, Chersich MF, Muller EE, Mayaud P, Delany-Moretlwe S: Oropharyngeal HPV infection: prevalence and sampling methods among HIV-infected men in South Africa. International journal of STD & AIDS 29:776–780, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wood NH, Makua KS, Lebelo RL, et al. : Human Papillomavirus Prevalence in Oral and Oropharyngeal Rinse and Gargle Specimens of Dental Patients and of an HIV-Positive Cohort from Pretoria, South Africa. Advances in virology 2020, 2020:2395219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rettig EM, Gooi Z, Bardin R, et al. : Oral Human Papillomavirus Infection and Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Rural North-west Cameroon. OTO open 3, 2019. 2473974×18818415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Morhason-Bello IO, Kabakama S, Baisley K, Francis SC, Watson-Jones D: Reported oral and anal sex among adolescents and adults reporting heterosexual sex in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reproductive Health 16:48, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Blumberg J, Monjane L, Prasad M, Carrilho C, Judson BL: Investigation of the presence of HPV related oropharyngeal and oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma in Mozambique. Cancer Epidemiol 39:1000–1005, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sekee TR, Burt FJ, Goedhals D, Goedhals J, Munsamy Y, Seedat RY: Human papillomavirus in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas in a South African cohort. Papillomavirus Res 6:58–62, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Oga EA, Schumaker LM, Alabi BS, et al. : Paucity of HPV-Related Head and Neck Cancers (HNC) in Nigeria. PloS one 11, 2016:e0152828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ndiaye C, Alemany L, Diop Y, et al. : The role of human papillomavirus in head and neck cancer in Senegal. Infectious agents and cancer 8:14, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Paquette C, Evans MF, Meer SS, Rajendran V, Adamson CS, Cooper K: Evidence that alpha-9 human papillomavirus infections are a major etiologic factor for oropharyngeal carcinoma in black South Africans. Head and neck pathology 7:361–372, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jalouli J, Jalouli MM, Sapkota D, Ibrahim SO, Larsson PA, Sand L: Human papilloma virus, herpes simplex virus and epstein barr virus in oral squamous cell carcinoma from eight different countries. Anti-cancer research 32:571–580, 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jalouli J, Ibrahim SO, Sapkota D, et al. : Presence of human papilloma virus, herpes simplex virus and Epstein−Barr virus DNA in oral biopsies from Sudanese patients with regard to toombak use. Journal of oral pathology & medicine 39:599–604, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Li K, Li Q, Song L, Wang D, Yin R: The distribution and prevalence of human papillomavirus in women in mainland China. Cancer 125:1030–1037, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Brotherton JML, Hawkes D, Sultana F, et al. : Age-specific HPV prevalence among 116,052 women in Australia’s renewed cervical screening program: A new tool for monitoring vaccine impact. Vaccine 37:412–416, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tabrizi SN, Brotherton JML, Stevens MP, et al. : HPV genotype prevalence in Australian women undergoing routine cervical screening by cytology status prior to implementation of an HPV vaccination program. Journal of Clinical Virology 60:250–256, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Brotherton JML, Fridman M, May CL, Chappell G, Saville AM, Gertig DM: Early effect of the HPV vaccination programme on cervical abnormalities in Victoria, Australia: an ecological study. The Lancet 377:2085–2092, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Srivastava S, Gupta S, Roy JK: High prevalence of oncogenic HPV-16 in cervical smears of asymptomatic women of eastern Uttar Pradesh, India: a population-based study. Journal of biosciences 37:63–72, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sowjanya AP, Jain M, Poli UR, et al. : Prevalence and distribution of high-risk human papilloma virus (HPV) types in invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix and in normal women in Andhra Pradesh. India. BMC infectious diseases 5:116, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sankaranarayanan R, Basu P, Kaur P, et al. : Current status of human papillomavirus vaccination in India’s cervical cancer prevention efforts. The Lancet Oncology 20:e637–ee44, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lu Y, Li P, Luo G, Liu D, Zou H: Cancer attributable to human papillomavirus infection in China: Burden and trends. Cancer 126:3719–3732, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wang B, He M, Chao A, et al. : Cervical cancer screening among adult women in China, 2010. The oncologist 20:627, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. : Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 66:115–132, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Asthana S, Chauhan S, Labani S: Breast and cervical cancer risk in India: An update. Indian journal of public health 58:5, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kurose K, Terai M, Soedarsono N, et al. : Low prevalence of HPV infection and its natural history in normal oral mucosa among volunteers on Miyako Island, Japan. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics 98:91–96, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cho H, Kishikawa T, Tokita Y, et al. : Prevalence of human papillomavirus in oral gargles and tonsillar washings. Oral oncology 105, 2020:104669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Antonsson A, Cornford M, Perry S, Davis M, Dunne MP, Whiteman DC: Prevalence and risk factors for oral HPV infection in young Australians. PloS one 9:e91761, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lucas-Roxburgh R, Benschop J, Dunowska M, Perrott M: Prevalence of human papillomaviruses in the mouths of New Zealand women 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chen F, Yan L, Liu F, et al. : Oral human papillomavirus infection, sexual behaviors and risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma in southeast of China: A case-control study. Journal of Clinical Virology 85:7–12, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hang D, Liu F, Liu M, et al. : Oral human papillomavirus infection and its risk factors among 5,410 healthy adults in China, 2009−2011. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers 23:2101–2110, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hong A, Lee CS, Jones D, et al. : Rising prevalence of human papillomavirus−related oropharyngeal cancer in Australia over the last 2 decades. Head & neck 38:743–750, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Argirion I, Zarins KR, McHugh J, et al. : Increasing prevalence of HPV in oropharyngeal carcinoma suggests adaptation of p16 screening in Southeast Asia. Journal of clinical virology: the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology 132, 2020:104637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Argirion I, Zarins KR, Defever K, et al. : Temporal Changes in Head and Neck Cancer Incidence in Thailand Suggest Changing Oropharyngeal Epidemiology in the Region. Journal of Global Oncology 1–11, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nair D, Mair M, Singh A, D’Cruz A: Prevalence and Impact of Human Papillomavirus on Head and Neck Cancers: Review of Indian Studies. Indian J Surg Oncol 9:568–575, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Guo L, Yang F, Yin Y, et al. : Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus Type-16 in Head and Neck Cancer Among the Chinese Population: A Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in oncology 8, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Herrero R, Hildesheim A, Bratti C, et al. : Population-based study of human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia in rural Costa Rica. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 92:464–474, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lazcano-Ponce E, Herrero R, Muñoz N, et al. : Epidemiology of HPV infection among Mexican women with normal cervical cytology. International journal of cancer 91:412–420, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ferreccio C, Prado RB, Luzoro AV, et al. : Population-based prevalence and age distribution of human papillomavirus among women in Santiago, Chile. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 13:2271–2276, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Molano M, Posso H, Weiderpass E, et al. : Prevalence and determinants of HPV infection among Colombian women with normal cytology. British journal of cancer 87:324–333, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sichero L, Picconi MA, Villa LL: The contribution of Latin American research to HPV epidemiology and natural history knowledge. Braz J Med Biol Res 53:e9560, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Roue T, Nacher M, Fior A, et al. : Cervical cancer incidence in French Guiana: South American. International journal of gynecological can cer: official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society 22:850–853, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Murillo R, Herrero R, Sierra MS, Forman D: Cervical cancer in Central and South America: Burden of disease and status of disease control. Cancer Epidemiol 44, 2016(Suppl 1). S121–s30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Capote Negrin LG: Epidemiology of cervical cancer in Latin America. Ecancermedicalscience 9:577, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Araújo MVdA, Pinheiro HHC, Pinheiro JdJV, Quaresma JAS, Fuzii HT, Medeiros RC: Prevalência do papilomavírus humano (HPV) em Belém, Pará, Brasil, na cavidade oral de indivíduos sem lesões clinicamente diagnosticáveis. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 30:1115–1119, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Criscuolo M, Belardinelli P, Morelatto R, et al. : Prevalence of oral human papillomavirus (HPV) in the adult population of Córdoba, Argentina. Translational Research in Oral Oncology 3, 2018. 2057178X18757334 [Google Scholar]

- 129.Rosen BJ, Walter L, Gilman RH, Cabrerra L, Gravitt PE, Marks MA: Prevalence and correlates of oral human papillomavirus infection among healthy males and females in Lima, Peru. Sexually Transmitted Infections 92:149, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Girardi FM, Wagner VP, Martins MD, Abentroth AL, Hauth LA: Prevalence of p16 expression in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in southern Brazil. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 130:681–691, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.De Cicco R, de Melo Menezes R, Nicolau UR, Pinto CA, Villa LL, Kowalski LP: Impact of human papillomavirus status on survival and recurrence in a geographic region with a low prevalence of HPV-related cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Head & neck 42:93–102, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Anantharaman D, Abedi-Ardekani B, Beachler DC, et al. : Geographic heterogeneity in the prevalence of human papillomavirus in head and neck cancer. International journal of cancer 140:1968–1975, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hauck F, Oliveira-Silva M, Dreyer JH, et al. : Prevalence of HPV infection in head and neck carcinomas shows geographical variability: a comparative study from Brazil and Germany. Virchows Arch 466:685–693, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Curado MP, Johnson NW, Kerr AR, et al. : Oral and oropharynx cancer in South America: incidence, mortality trends and gaps in public databases as presented to the Global Oral Cancer Forum. Translational Research in Oral Oncology 1, 2016. 2057178X16653761 [Google Scholar]

- 135.Quintero K, Giraldo GA, Uribe ML, et al. : Human papillomavirus types in cases of squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck in Colombia. Brazilian journal of otorhinolaryngology 79:375–381, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Walter L, Vidaurre T, Gilman RH, et al. : Trends in head and neck cancers in Peru between 1987 and 2008: Experience from a large public cancer hospital in Lima. Head Neck 36:729–734, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Ndiaye C, Mena M, Alemany L, et al. : HPV DNA, E6/E7 mRNA, and p16INK4a detection in head and neck cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Oncology 15:1319–1331, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Castellsagué X, Alemany L, Quer M, et al. : HPV Involvement in Head and Neck Cancers: Comprehensive Assessment of Biomarkers in 3680 Patients. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 108:djv403, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]