Abstract

Metabolic dysfunction exacerbates Alzheimer’s disease (AD) incidence and progression. Here we report that activation of the AMPK pathway, a common target in the management of diabetes, results in gender-divergent cognitive effects in a murine model of the disease. Specifically, our results show that activation of AMPK increases memory dysfunction in males but is protective in females, suggesting that gender considerations may constitute an important factor in medical intervention of diabetes as well as AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, AMPK, metformin, type 2 diabetes mellitus

INTRODUCTION

Epidemiological data indicate that obesity and diabetes more than double the risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1, 2], while factors that improve metabolic health, such as exercise, show promise in combating the disease [3, 4]. Consistent with these findings from human patients, murine models of AD subjected to metabolic stress in the form of high fat or high sugar diet exhibit an accelerated disease phenotype [5, 6] and, conversely, exercise or caloric restriction reduces AD-like cognitive impairments [7, 8]. Despite these connections, little is known about the molecular mechanisms that underlie this effect.

At a physiological level, a feature common to both exercise and caloric restriction is a lowered energetic status. At the cellular level, this energy reduction is apparent as a decrease in the ratio of ATP:AMP and detected by the ubiquitously-expressed AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [9, 10]; a central sensor of intracellular energetic status and regulator of metabolic processes. We hypothesized that AMPK activation may therefore serve as an exercise- or caloric restriction-mimetic and thereby provide protection against the development of AD. To address this possibility, we used both pharmacological and genetic means to activate AMPK in AβPP mice and tested their cognitive function by Morris water maze.

METHODS

Mice

We used the previously characterized PDAPP (J9) mouse model of AD [11, 12] (AβPP mice) on a C57Bl/6 background. Mice were treated with 2 mg/ml metformin (Sigma, cat# D150959) in their drinking water (approximately 350 mg/kg/day), a dose and mode of delivery successfully used in another neurodegenerative mouse model [13] and within the wide range of doses that have shown efficacy as anti-hyperglycemic in diabetic models [14]. Control animals received standard drinking water. Treatment began between 6–8 weeks of age, except for a small group of animals in our pilot study that began treatment at 6–8 months of age and continued for all mice until completion of the study at approximately 14–16 months of age.

For our genetic model of peripheral AMPK activation, we crossed the AβPP mice with a transgenic model expressing constitutively active (CA)-AMPK-alpha1 in the liver under the human ApoE promoter with a similar genetic background (C57Bl/6). These mice were reported to have resistance against obesity, lower fasting blood glucose levels, and improved insulin sensitivity [15].

All animal procedures met NIH animal care guidelines and were approved by The Salk Institute animal committee.

Insulin tolerance test

Mice were fasted for six hours and fasted body weight and baseline blood glucose measurements were made. Blood glucose levels were measured using a NovaMax glucose meter and test strips. Insulin (Eli Lilly, Humulin R, Hi-210) was administered at 1 U/kg fasted body weight and glucose measurements were made over the subsequent two hours. Only male mice were used to avoid variability due to hormonal fluctuations in females. Mice were tested at 13–15 months of age. Data were analyzed with a two factor (genotype × treatment) repeated measures ANOVA.

Morris water maze

Learning and memory were assessed using the Morris water maze with a 14 consecutive day, three-phase protocol: 1) Visible Platform training: 3 days to acclimate to the test and confirm that no motor or visual disability existed; 2) Hidden Platform training: 10 days for learning ability and memory acquisition; and 3) Probe Test: final day to measure memory retention. Mouse movements were tracked and parameters calculated by Ethovision software (Noldus). Each mouse was given 4 training trials each day during phases 1 and 2. Animals that failed to find the platform >50% of trials on the final day of the Visible Platform phase were excluded from further testing. Additionally, six mice passed the Visible Platform test and qualified at that time for inclusion, but in later trials would not swim and spent the duration of testing trials floating. It was decided to exclude these mice since there was no way to determine if and to what extent any learning or memory deficit contributed to the refusal to participate. No link was found to any gender, genotype, or treatment condition. Data were analyzed with a three factor ANOVA (gender × genotype × treatment or 2nd genotype) with repeated measures for the hidden platform phase and univariate analysis for the probe test. SPSS software with Advanced Statistics module was used, GLM command and MANOVA for pairwise comparisons.

RESULTS

We used both pharmacological and genetic approaches to activate AMPK in the AβPP mice and assessed their AD-related behavioral phenotypes. First, we treated AβPP mice with the anti-diabetic, AMPK-activating drug metformin, which was dissolved in their drinking water at 2 mg/ml. We found no alteration in water consumption or body weight with treatment (Supplementary Figure 1). Since metformin is an insulin-sensitizing drug, we measured blood glucose responses following insulin administration. Metformin-treated mice responded to the insulin challenge with a greater drop in blood glucose levels suggesting the drug was effective in improving insulin sensitivity at this dose (Supplementary Figure 1).

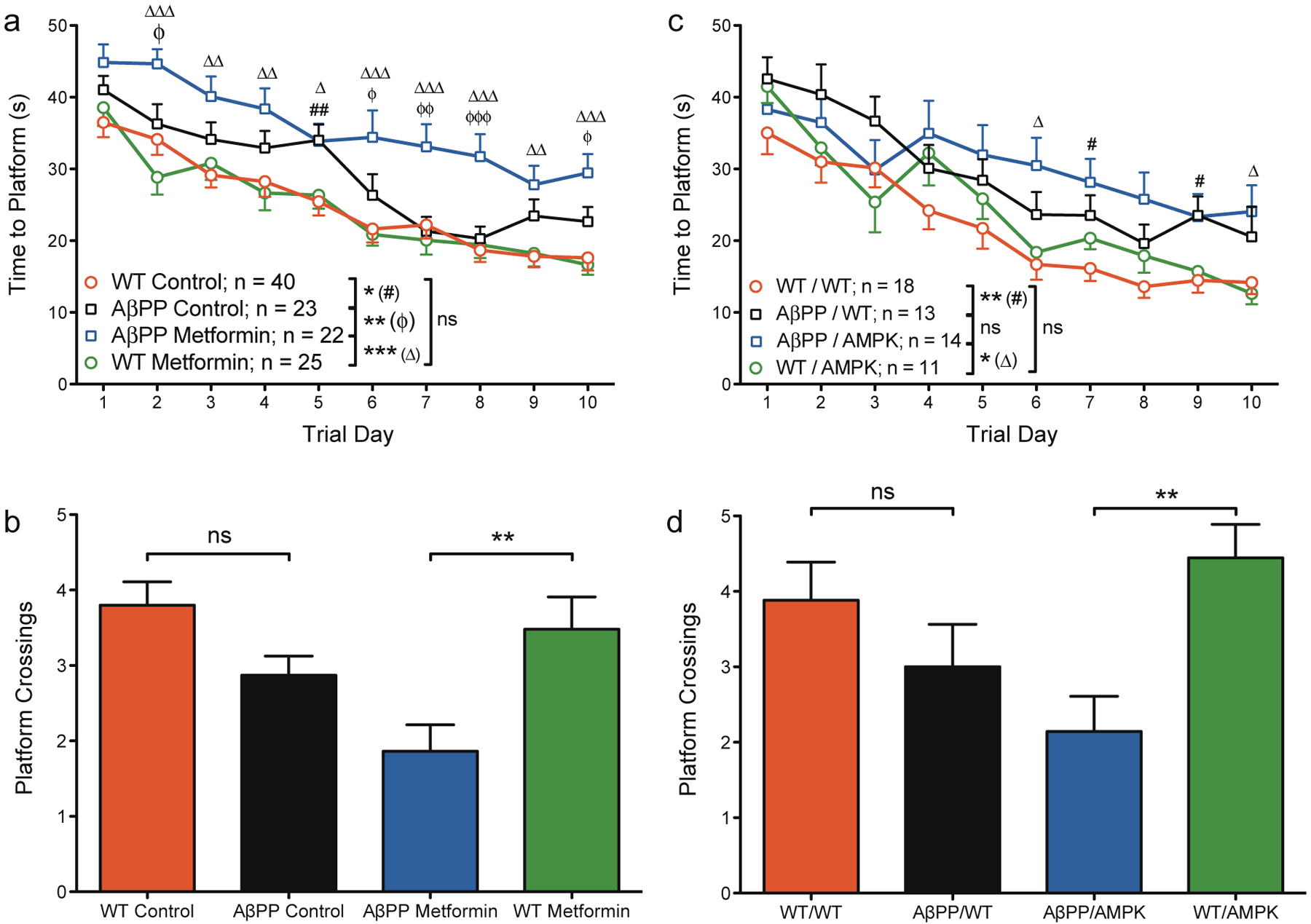

To determine if metformin treatment resulted in a cognitive consequence, we tested the mice on the Morris water maze. Contrary to our hypothesis, male AβPP mice treated with metformin consistently required more time to find the escape platform than AβPP mice in the control group during training (Fig. 1a) and, during the probe trial, crossed the area where the platform had previously been located fewer times than controls (Fig. 1b). We first observed these phenomena in a small pilot study of just 5–6 mice per group, and have since confirmed the finding in three additional cohorts totaling over 20 mice per group. We reasoned that this surprising finding could be due to non-AMPK-related activities of metformin, or, despite having beneficial metabolic effects within the periphery, AMPK activation in the brain may lead to disruptions of memory function [16]. To circumvent these possibilities, we sought to activate AMPK specifically and to limit activation to the periphery in hopes of improving metabolic status without negative impacts to cognitive function. Thus, we bred the AβPP mice with mice expressing a constitutively active version of AMPK specifically in the liver [15] and again tested the mice for learning and memory function. Despite the specificity of our genetic model, we observed similar results to the metformin study. During the hidden platform phase of the Morris water maze, AβPP/AMPK double transgenic mice performed slightly worse than AβPP/wildtype (WT) mice from day four onwards (Fig. 1c) and again displayed impairment in the probe trial (Fig. 1d) with remarkable similarity in outcome to the metformin study.

Fig. 1.

AMPK activation impairs spatial learning and memory retention in male AβPP mice. 12- to 14-month old mice received four trials per day for 10 days of training to find a hidden platform in the Morris water maze followed by a single probe trial on the final day of testing in which the platform was removed. a, b) Metformin study: a) AβPP mice in both the control group and the metformin group require more time to find the platform than their WT counterparts. Metformin-treated AβPP mice perform significantly worse than control-treated AβPP mice. b) On the probe trial, AβPP mice crossed the location where the platform had previously been located fewer times than WT mice on average, but the difference did not quite meet the criteria for statistical significance (p = 0.0696). Within the metformin-treated group, AβPP mice demonstrated significantly impaired spatial memory retention (p = 0.005). c,d) AMPK Study: c) In the presence or absence of AMPK, AβPP mice perform worse than WT mice. AβPP/AMPK mice were not statistically distinguishable from AβPP/WT mice although a slight but consistent trend toward impaired performance with AMPK expression was apparent from day four through the end of training. d) Although on average AβPP/WT mice crossed the platform location fewer times than WT/WT mice, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.333). With AMPK expression, AβPP mice demonstrated significantly impaired spatial memory retention. For the hidden platform (a, c): data represent the average latencies for four trials for the mice in each group to locate the escape platform; error bars represent SEM; ns, not significant; asterisks in the reference legend of each graph represent significance of the entire curve by repeated measures ANOVA: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; symbols on the graph represent significance of individual points on the curve: #WT control versuss AβPP control; ϕAβPP control vrsus AβPP metformin; #,ϕp < 0.05, ##,ϕϕp < 0.01, ϕϕϕp < 0.001. For the probe trial (b, d): data represent the average number of times the mice in each group crossed the area where the platform had previously been located; error bars represent SEM; ns, not significant; **p < 0.01. Sample sizes are identical to the training phase.

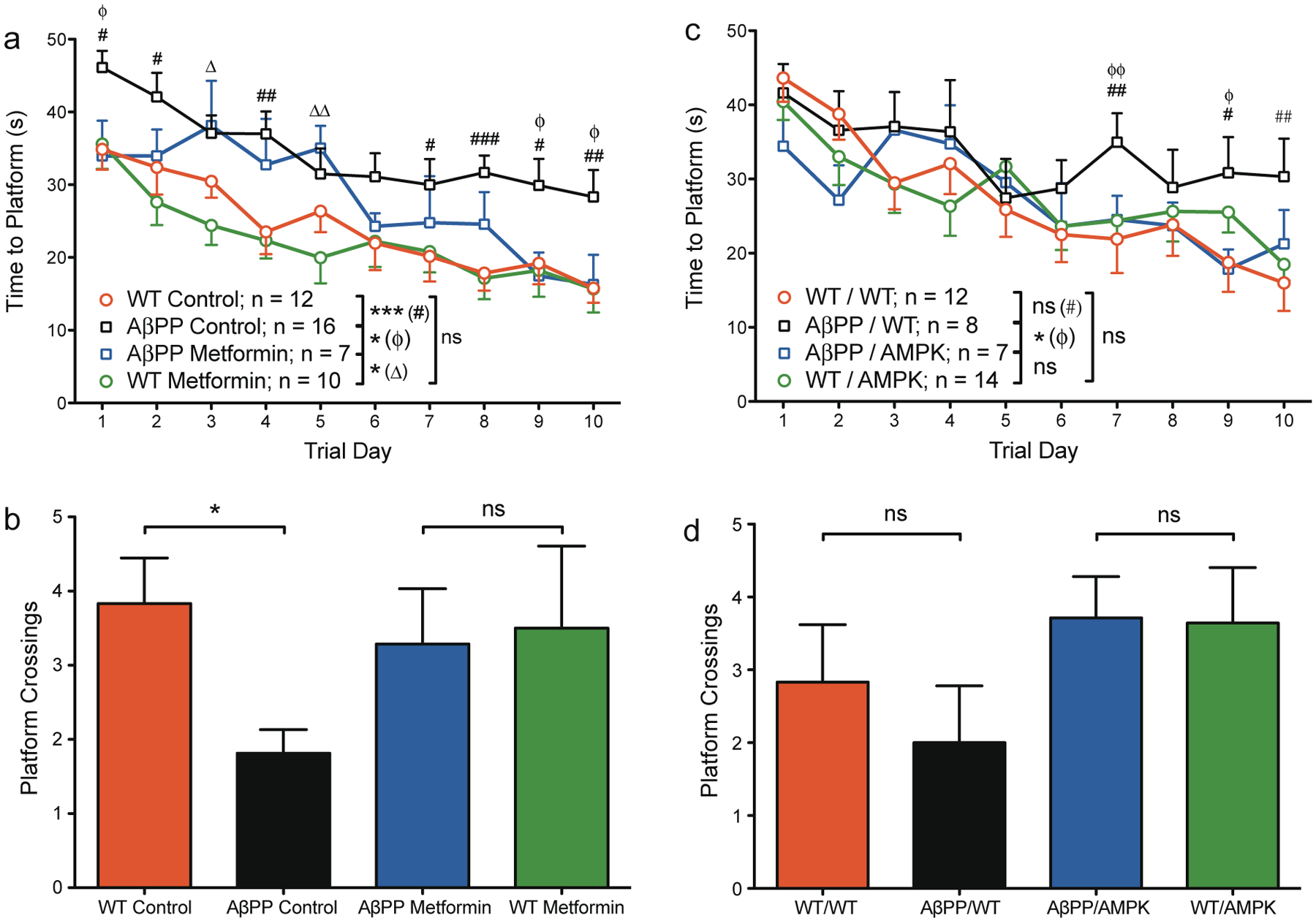

To a greater extent than the males, female AβPP mice in the control group also exhibited difficulties learning to find the platform as compared to WT mice (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Figure 1). Consistent with this larger deficit, female AβPP mice were unable to remember the platform location as well as WT mice when tested on the probe test (Fig. 2b). However, contrary to the findings in the male mice treated with metformin, female AβPP mice receiving metformin treatment out-performed the control-treated AβPP mice (Fig. 2a). During the probe trial, female AβPP mice that had received metformin treatment were rescued of the deficit observed in the female AβPP control mice (Fig. 2b). This result is consistent with our initial hypothesis and was again replicated in the genetic model of AMPK activation (Fig. 2c, d, Supplementary Figure 1).

Fig. 2.

AMPK activation improves learning and memory function in female AβPP mice. 12- to 14-month old mice received four trials per day for 10 days of training to find a hidden platform in the Morris water maze followed by a single probe trial on the final day of testing in which the platform was removed. a, b) Metformin study: a) Training phase: female AβPP mice had longer latencies to find the escape platform than WT mice in the control group. Within the metformin-treated groups, AβPP mice took longer to find the platform in the early days of testing; however, metformin-treated AβPP mice were significantly improved over control-treated AβPP mice. b) Probe trial: within the control treatment group, AβPP mice crossed the platform location fewer times than WT mice. AβPP mice in the metformin treatment group, however, were indistinguishable from WT mice. c, d) AMPK study: c) Training phase: female AβPP/WT mice had longer latencies to find the escape platform than WT/WT mice in the later part of training. AβPP/AMPK mice were significantly improved over AβPP/WT mice and were in fact statistically indistinguishable from WT/AMPK mice. d) Probe trial: by the measure of platform crossings, AβPP/WT mice performed poorly, but were not statistically different from WT/WT mice (by time spent in the target quadrant, these groups were distinguishable, see Supplementary Figure 1). AβPP/AMPK mice demonstrated no memory impairment. For the hidden platform (a, c): data represent the average latencies for four trials for the mice in each group to locate the escape platform; error bars represent SEM; ns, not significant; asterisks in the reference legend of each graph represent significance of the entire curve by repeated measures ANOVA: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; symbols on the graph represent significance of individual points on the curve: #WT control versus AβPP control; ϕAβPP control versus AβPP metformin; #,ϕp < 0.05, ##,ϕϕp < 0.01, ###p < 0.001. For the probe trial (b, d): data represent the average number of times the mice in each group crossed the area where the platform had previously been located; error bars represent SEM; ns, not significant; *p < 0.05. Sample sizes are identical to the training phase.

DISCUSSION

In summary, we report that male mice treated with metformin at a dose that improves insulin sensitivity had worsened AD-related behavioral phenotypes. Female mice receiving treatment demonstrated improvements by the same measures. These findings were also observed in a genetic model of AMPK activation, suggesting that some unknown systemic factor must be downstream of liver AMPK activation and affecting AD-related cognitive function in these animals.

Recently, female mice have been reported to exhibit lifespan extension and delayed deterioration of the estrous cycle with metformin treatment [17, 18]. Additionally, reduced malignant tumor formation has been observed [18, 19]. Collectively, these reports as well as those of the current study support general anti-aging effects of metformin treatment with application to diseases of aging in female mice. On the contrary, male mice were reported to have shortened lifespan with metformin treatment [18], which would be consistent with the worsened outlook for AD-related phenotypes reported herein. A handful of previous studies have looked at the effect of metformin treatment in various measures of AD-relevant neuronal changes with mixed results but generally favoring a beneficial effect [20–23]. The gender differences reported here and previously suggest an added layer of complexity in whole animal physiology that may help to explain these differing results. In contrast, epidemiological analyses have begun to look at the relationship between metformin and AD and early indications side with a detrimental effect of the drug in terms of disease risk [24, 25]. These studies included males and females in equal numbers; it would be interesting to see if the overall effect is more pronounced in the males or if both males and females were equally affected. It is also important to note that in these studies, AD risk with metformin treatment was assessed in the context of existing diabetes, which was not part of our model. It is possible, therefore, that metformin treatment in otherwise healthy, non-diabetic females may have therapeutic potential. Nevertheless, obesity and diabetes rates have been increasing steadily, and as our population ages the diagnosis of AD is expected to increase as well. The convergence of these factors suggest that the effects of metformin treatment on cognitive function and AD in human patients may have growing importance in the years to come and the cognitive effects may need to be balanced against the benefits of this drug when considering options for the treatment of diabetes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Bangyan Stiles for providing the CA-AMPK mice, Russell Nofsinger for training and advice regarding the insulin tolerance test, and Eliezer Masliah for use of equipment and thoughtful discussions. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant P01 AG010436 (to S.F.H.); K.D. was supported in part by the Neuroplasticity of Aging Training Grant AG000216.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://www.jalz.com/disclosures/view.php?id=2497)

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

The supplementary figure is available in the electronic version of this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-141332.

REFERENCES

- [1].Kivipelto M, Ngandu T, Fratiglioni L, Viitanen M, Kareholt I, Winblad B, Helkala EL, Tuomilehto J, Soininen H, Nissinen A (2005) Obesity and vascular risk factors at midlife and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 62, 1556–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ott A, Stolk RP, van Harskamp F, Pols HA, Hofman A, Breteler MM (1999) Diabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia: The Rotterdam Study. Neurology 53, 1937–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Stevens J, Killeen M (2006) A randomised controlled trial testing the impact of exercise on cognitive symptoms and disability of residents with dementia. Contemp Nurse 21, 32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rolland Y, Pillard F, Klapouszczak A, Reynish E, Thomas D, Andrieu S, Riviere D, Vellas B (2007) Exercise program for nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s disease: A 1-year randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 55, 158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Maesako M, Uemura K, Iwata A, Kubota M, Watanabe K, Uemura M, Noda Y, Asada-Utsugi M, Kihara T, Takahashi R, Shimohama S, Kinoshita A (2013) Continuation of exercise is necessary to inhibit high fat diet-induced beta-amyloid deposition and memory deficit in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. PloS One 8, e72796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cao D, Lu H, Lewis TL, Li L (2007) Intake of sucrose-sweetened water induces insulin resistance and exacerbates memory deficits and amyloidosis in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem 282, 36275–36282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Parachikova A, Nichol KE, Cotman CW (2008) Short-term exercise in aged Tg2576 mice alters neuroinflammation and improves cognition. Neurobiol Dis 30, 121–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Halagappa VK, Guo Z, Pearson M, Matsuoka Y, Cutler RG, Laferla FM, Mattson MP (2007) Intermittent fasting and caloric restriction ameliorate age-related behavioral deficits in the triple-transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 26, 212–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jiang W, Zhu Z, Thompson HJ (2008) Dietary energy restriction modulates the activity of AMP-activated protein kinase, Akt, and mammalian target of rapamycin in mammary carcinomas, mammary gland, and liver. Cancer Res 68, 5492–5499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ruderman NB, Park H, Kaushik VK, Dean D, Constant S, Prentki M, Saha AK (2003) AMPK as a metabolic switch in rat muscle, liver and adipose tissue after exercise. Acta Physiol Scand 178, 435–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hsia AY, Masliah E, McConlogue L, Yu GQ, Tatsuno G, Hu K, Kholodenko D, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA, Mucke L (1999) Plaque-independent disruption of neural circuits in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96, 3228–3233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dziewczapolski G, Glogowski CM, Masliah E, Heinemann SF (2009) Deletion of the alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene improves cognitive deficits and synaptic pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 29, 8805–8815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ma TC, Buescher JL, Oatis B, Funk JA, Nash AJ, Carrier RL, Hoyt KR (2007) Metformin therapy in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Neurosci Lett 411, 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Meglasson MD, Wilson JM, Yu JH, Robinson DD, Wyse BM, de Souza CJ (1993) Antihyperglycemic action of guanidinoalkanoic acids: 3-guanidinopropionic acid ameliorates hyperglycemia in diabetic KKAy and C57BL6Job/ob mice and increases glucose disappearance in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 266, 1454–1462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Yang J, Maika S, Craddock L, King JA, Liu ZM (2008) Chronic activation of AMP-activated protein kinase-alpha1 in liver leads to decreased adiposity in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 370, 248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Potter WB, O’Riordan KJ, Barnett D, Osting SM, Wagoner M, Burger C, Roopra A (2010) Metabolic regulation of neuronal plasticity by the energy sensor AMPK. PloS One 5, e8996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Anisimov VN, Berstein LM, Egormin PA, Piskunova TS, Popovich IG, Zabezhinski MA, Tyndyk ML, Yurova MV, Kovalenko IG, Poroshina TE, Semenchenko AV (2008) Metformin slows down aging and extends life span of female SHR mice. Cell Cycle 7, 2769–2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Anisimov VN (2010) Metformin for aging and cancer prevention. Aging 2, 760–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Anisimov VN, Berstein LM, Egormin PA, Piskunova TS, Popovich IG, Zabezhinski MA, Kovalenko IG, Poroshina TE, Semenchenko AV, Provinciali M, Re F, Franceschi C (2005) Effect of metformin on life span and on the development of spontaneous mammary tumors in HER-2/neu transgenic mice. Exp Gerontol 40, 685–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chen Y, Zhou K, Wang R, Liu Y, Kwak YD, Ma T, Thompson RC, Zhao Y, Smith L, Gasparini L, Luo Z, Xu H, Liao FF (2009) Antidiabetic drug metformin (GlucophageR) increases biogenesis of Alzheimer’s amyloid peptides via up-regulating BACE1 transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 3907–3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Greco SJ, Sarkar S, Johnston JM, Tezapsidis N (2009) Leptin regulates tau phosphorylation and amyloid through AMPK in neuronal cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 380, 98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gupta A, Bisht B, Dey CS (2011) Peripheral insulin-sensitizer drug metformin ameliorates neuronal insulin resistance and Alzheimer’s-like changes. Neuropharmacology 60, 910–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kickstein E, Krauss S, Thornhill P, Rutschow D, Zeller R, Sharkey J, Williamson R, Fuchs M, Kohler A, Glossmann H, Schneider R, Sutherland C, Schweiger S (2010) Biguanide metformin acts on tau phosphorylation via mTOR/protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 21830–21835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Moore EM, Mander AG, Ames D, Kotowicz MA, Carne RP, Brodaty H, Woodward M, Boundy K, Ellis KA, Bush AI, Faux NG, Martins R, Szoeke C, Rowe C, Watters DA (2013) Increased risk of cognitive impairment in patients with diabetes is associated with metformin. Diabetes Care 36, 2981–2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Imfeld P, Bodmer M, Jick SS, Meier CR (2012) Metformin, other antidiabetic drugs, and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: A population-based case-control study. J Am Geriatr Soc 60, 916–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.