Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has disrupted health care globally with dramatic impacts on cancer care delivery in addition to adverse economic and psychological effects. This study examined impacts of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on young adult colorectal cancer (CRC) survivors diagnosed age 18–39 years. Nearly 40% reported delays in cancer-related care, loss of income, and poorer mental health during the pandemic. Impacts were greater for survivors aged 20–29 years, with nearly 60% reporting cancer care delays and 53% experiencing income loss. Such impacts may result in detrimental downstream outcomes for young CRC survivors, requiring specific support, resources, and continued monitoring.

Keywords: colon, rectum, SARS-CoV-2, health services, quality of life

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has disrupted health care globally with dramatic impacts on cancer care delivery, including decreases and delays in diagnoses of incident cancers and in treatment of existing disease, clinical trial enrollment, surveillance, and survivorship care.1–4 In-person care for cancer patients and survivors has been suspended or provided intermittently throughout the course of the pandemic and the accessibility of needed services has been significantly curtailed.5

Colorectal cancer (CRC) requires multimodal therapy, including a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and irradiation. Owing to high rates of recurrence (between 30% and 40%), CRC also requires active disease surveillance in survivorship.6 CRC-related care delivery has been significantly disrupted by the pandemic with decreases of 40% in CRC services, including screening and diagnostic colonoscopy, surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy in the United States in April 2020 versus April 2019.3 Among 20 surgical societies surveyed internationally, 71% reported disruptions in CRC-related care.3,7

CRC is also associated with deficits in health-related quality of life, including psychological impairments.8,9 In addition, due to social distancing measures that attenuated social support networks during the pandemic, CRC patients and survivors may also experience heightened psychosocial distress, including increased anxiety, depression, and reduced coping. Thus, the impacts from the SARS-CoV-2 are likely to be substantial for these patients.

Adolescent and young adult cancer survivors (AYAs; diagnosed age 18–39 years) are a vulnerable population who face delays in diagnosis, often forgo care due to financial issues, and experience adverse psychological outcomes.10 Impacts of the pandemic may, therefore, be amplified for AYAs. We documented impacts of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on AYA CRC survivors regarding their experiences with health care, finances, and mental health. Because younger adults (under age 30 years) may be disproportionately burdened in line with national data that show significant impacts among this age group in the general population,11 we stratified by age to examine whether survivors under age 30 years experienced greater impacts. Overall, understanding the experiences of these survivors can identify areas of highest impact to aid in preparing for the long-term consequences of the pandemic on this at-risk population.

Methods

A cross-sectional online survey was administered on the Facebook page of a national CRC advocacy organization, The Colon Club, between August 31 and September 3, 2020. The Colon Club was founded in 2003 to raise awareness, educate, and help those with early-onset CRC and the organization has a highly active public Facebook page with >7000 followers. Eligible participants were colon or rectal cancer survivors age 18–39 years at diagnosis, between 6 and 36 months from diagnosis or relapse, and based in the United States. The focus of the study was on those in early survivorship as these individuals are most likely to have more closely managed health care interactions, whereas those >36 months from diagnosis or relapse have likely transitioned to a more chronic care plan. Upon survey completion, participants received a $20 electronic gift card. The study was approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board (IRB).

To ensure validity and integrity of data and reduce potential fraudulent responses encountered in social media recruitment, participants were first asked questions regarding eligibility to eliminate automated software or “bots.”12 Additional steps to reduce fraudulent responses included prohibition of duplicate emails; removal of respondents whose survey completion was <5 minutes given average completion time of 17 minutes; and removal of respondents reporting “highly improbable” medical treatment patterns (e.g., patients who reported stage 1 colon cancer and reported receiving immunotherapy) as reviewed by a medical oncologist (A.B.).

Questions from The Pandemic Stress Index (PSI) were used to assess pandemic impacts.13 Participants were presented with a list of issues, including health care delay, financial and job loss, and psychological/emotional distress and asked to endorse all that apply (see Supplementary Appendix SA1 for survey questions).

Frequencies and percentages were calculated for sample demographics and PSI items. Analyses were conducted for the overall sample and then stratified by age group (current age 20–29 vs. 30–42 years). Statistical analysis was performed using Stata (Version 14.2; StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Overall, 371 survey responses were received. After eliminating respondents who did not meet eligibility criteria or who were deemed potentially fraudulent, n = 196 (53%) were retained.

Table 1 presents sample characteristics. Mean age (standard deviation) was 32.1 (4.5); 116 (59%) were male; and tumor location was colon or rectal in 39% and 61%, respectively. The majority (56%) were diagnosed with stage 2 disease. Relapsed disease was reported by 58% of respondents, and 30% had an ostomy. The majority of respondents were non-Latino white (79%).

Table 1.

Characteristic of the Sample Overall and by Age Category

| Total |

Current age |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 196 | 20–29 (n = 56) | 30–42 (n = 140) | |

| Mean age (SD) | 32.1 (4.5) | 26.7 (2.3) | 34.3 (3.1) |

| Cancer type | |||

| Colon | 75 (39.3) | 23 (42.6) | 52 (38.0) |

| Rectal | 116 (60.7) | 31 (57.4) | 85 (62.0) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 116 (59.9) | 33 (61.1) | 83 (59.3) |

| Female | 78 (40.1) | 21 (38.9) | 57 (40.7) |

| Stage at diagnosis | |||

| Stage 1 | 43 (22.1) | 18 (32.1) | 25 (18.0) |

| Stage 2 | 110 (56.4) | 23 (41.1) | 87 (62.6) |

| Stage 3 | 36 (18.4) | 13 (23.2) | 23 (16.5) |

| Stage 4 | 6 (3.1) | 2 (3.6) | 4 (2.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 20 (10.4) | 8 (14.5) | 12 (8.7) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 153 (79.3) | 41 (74.5) | 112 (81.2) |

| Black/African American | 13 (6.7) | 3 (5.5) | 10 (7.3) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander/other | 7 (3.6) | 3 (5.5) | 4 (2.8) |

| Region | |||

| Midwest | 37 (19.0) | 6 (10.9) | 31 (22.1) |

| Northeast | 28 (14.4) | 8 (14.6) | 20 (14.3) |

| South | 70 (35.9) | 27 (49.1) | 43 (30.7) |

| West | 60 (30.7) | 14 (25.4) | 46 (32.9) |

| Relapse | |||

| Yes | 112 (57.7) | 23 (42.6) | 89 (63.6) |

| Ostomy | |||

| Yes | 57 (29.7) | 11 (20.0) | 46 (33.6) |

| Income per year | |||

| <$35,000 | 32 (16.3) | 14 (25.0) | 18 (12.9) |

| $35,000–$74,999 | 118 (60.2) | 26 (46.4) | 92 (65.7) |

| $75,000–$149,999 | 43 (22.0) | 15 (26.8) | 28 (20.0) |

| >$150,000 | 3 (1.5) | 1 (1.8) | 2 (1.4) |

SD, standard deviation.

Impacts of the pandemic in the overall sample

Table 2 presents percentages of those endorsing pandemic-related impacts. Overall, 43% of survivors reported delays in cancer-related health care. Thirty-seven percent and 41% of respondents reported delays in general medical care and obtaining prescription medication, respectively. Forty-two percent experienced income loss, whereas 30% reported lacking basic supplies (food, water, medications, or a place to stay). Job loss was reported by 25% of respondents.

Table 2.

Impacts of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 on Young Adult Colorectal Cancer Survivors (n = 196)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Delay in cancer-related care | 84 (42.9) |

| Delay in general health care | 72 (36.7) |

| Delay in prescription meds | 81 (41.3) |

| Lack of basic supplies | 59 (30.1) |

| Job loss | 49 (25.0) |

| Loss of income | 82 (41.8) |

| More anxiety | 78 (39.8) |

| More depression | 71 (36.2) |

| More substance use | 27 (13.8) |

Forty percent of AYA CRC survivors experienced more anxiety as a result of the pandemic, whereas 36% experienced more depression. Increased substance use was reported by 14% of respondents.

Impacts of the pandemic stratified by age group

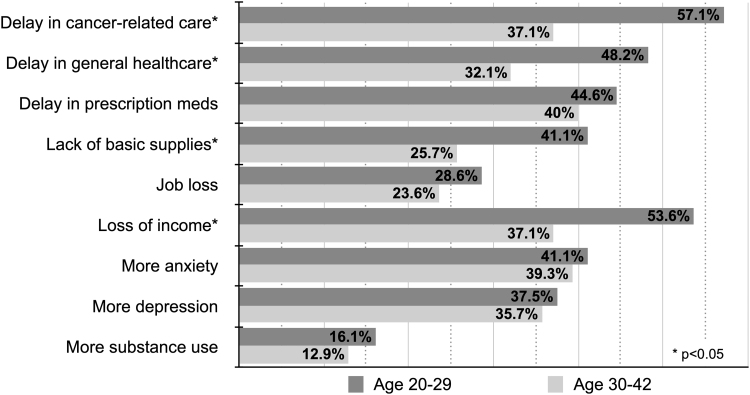

Figure 1 presents results stratified by age group (20–29 vs. 30–42 years). Delays in cancer-related care were reported by 57% of those ages 20–29 years versus 37% age 30–42 years (p = 0.01). Delays in general medical care followed a similar pattern (48% in younger group vs. 32% in the older; p = 0.04). A significantly higher percentage of younger CRC survivors reported lacking basic supplies versus older (41% vs. 26%; p = 0.03), and younger survivors reported higher rates of income loss versus older (54% vs. 37%; p = 0.04).

FIG. 1.

Impacts of SARS-CoV-2 on young adult CRC survivors stratified by age group (n = 196). CRC, colorectal cancer; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Discussion

Common to many AYA cancer patients and survivors, young adult CRC survivors experience delays in care, financial hardship, and reduced quality of life.14 This study found substantial impacts from the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on this already at-risk population across several domains, resulting in delayed health care, economic loss, and psychological burden.

Reasons for gaps in health care resulting from the pandemic may include patient avoidance due to fears of contracting COVID, health care system closures, loss of insurance coverage, or having contracted COVID. For AYA CRC survivors who require vigilant surveillance, such delays may lead to poorer outcomes and increased mortality. CRC survivors age 20–29 years were particularly affected in this sample, with nearly 60% reporting pandemic-related delays in cancer-related care.

A high percentage of respondents reported economic impacts due to the pandemic. Survivors in the younger age category were disproportionately burdened, with more than half experiencing income loss. Such data correspond with United States economic trends as young adults accounted for 16% of job losses during February–June of 2020 and experienced high rates of uninsurance.15 Many young adults' income is tied to the “gig economy” (e.g., temporary or short-term work) where the pandemic has severely disrupted demand. As CRC survivors may already experience financial toxicity due to cancer care costs, impacts of the pandemic may present severe economic sequelae, with youngest age survivors at greatest risk.16

Respondents also endorsed negative psychological impacts. These findings are in keeping with a study by Košir et al. conducted within the first weeks of the pandemic where one-third of AYA-aged cancer patients and survivors reported clinical levels of psychological distress. Our findings, collected later in the pandemic, document the continued mental distress of AYA survivors.

Strengths of the study include a large sample recruited from a well-known national advocacy organization. Limitations include the cross-sectional design limiting the ability to infer causality and self-reported data that are subject to bias. Similarly, prepandemic levels of variables included in this study were not able to be measured. Despite rigorous attempts to reduce fraudulent responses, social media sampling prevents full verification of respondents' patient status. Relatedly, a social media sample may not be representative of the overall patient population as respondents were connected to an online resource and may represent a more motivated sample. In addition, respondents were predominantly non-Latino white. Finally, we aimed to provide a snapshot of COVID-related impacts and respondents were not queried in-depth regarding reasons for specific impacts.

In summary, this study administered during the middle of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic found considerable impacts across health care, economic, and mental health domains for AYA CRC survivors based in the United States, particularly affecting those under age 30 years. Such impacts may have long-lasting effects for young CRC survivors and by extension, other AYA cancer survivors, as disruptions in care, financial distress, and mental health challenges may compromise quality of life, lead to forgoing medical care, and increase psychological burden for an already vulnerable group. In addition, these impacts may disproportionately affect younger AYAs who experience greater economic and employment instability. As the pandemic continues to evolve, young adult CRC survivors and other AYA cancer survivors may require specific supports, resources, and continued monitoring to mitigate its impacts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Priscilla Marin for her research support and extend appreciation to all of the Colon Club survivors who participated in the study.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This study was supported by The Aflac Archie Bleyer Young Investigator Award in Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology from the Children's Oncology Group. Additional support was provided by the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA014089 from the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Manso L, De Velasco G, Paz-Ares L. Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on cancer patient flow and management: experience from a large university hospital in Spain. ESMO Open. 2020;4(Suppl 2):e000828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Richards M, Anderson M, Carter P, Ebert BL, Mossialos E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care. Nat Cancer. 2020:1:565–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. London JW, Fazio-Eynullayeva E, Palchuk MB, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer-related patient encounters. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2020;4:657–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. Accessed January 30 2020 from: COVID-19 significantly impacts health services for noncommunicable diseases. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/01-06-2020-covid-19-significantly-impacts-health-services-for-noncommunicable-diseases.

- 5. Jammu AS, Chasen MR, Lofters AK, Bhargava R. Systematic rapid living review of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer survivors: update to August 27, 2020. Support Care Cancer. 2020. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1007/s00520-020-05908-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(3):145–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Santoro GA, Grossi U, Murad-Regadas S, et al. DElayed COloRectal cancer care during COVID-19 Pandemic (DECOR-19): global perspective from an international survey. Surgery. 2021;169(4):796–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ratjen I, Schafmayer C, Enderle J, et al. Health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of colorectal cancer and its association with all-cause mortality: a German cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sprangers MA, Taal BG, Aaronson NK, te Velde A. Quality of life in colorectal cancer. Stoma vs. nonstoma patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38(4):361–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith AW, Keegan T, Hamilton A, et al. Understanding care and outcomes in adolescents and young adult with Cancer: a review of the AYA HOPE study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(1):e27486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. The Century Foundation. Young People Will Bear the Brunt of COVID-19's Economic Consequences. Accessed January 30 2021 from: https://tcf.org/content/commentary/young-people-will-bear-brunt-covid-19s-economic-consequences/?agreed=1. 2020.

- 12. Pozzar R, Hammer MJ, Underhill-Blazey M, et al. Threats of bots and other bad actors to data quality following research participant recruitment through social media: cross-sectional questionnaire. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(10):e23021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harkness A, Behar-Zusman V, Safren SA. Understanding the impact of COVID-19 on Latino sexual minority men in a US HIV hot spot. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(7):2017–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parsons HM, Harlan LC, Lynch CF, et al. Impact of cancer on work and education among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(19):2393–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. The Commonwealth Fund. How Many Americans Have Lost Jobs with Employer Health Coverage During the Pandemic? Accessed January 30, 2021 from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/oct/how-many-lost-jobs-employer-coverage-pandemic. 2020.

- 16. Desai A, Gyawali B. Financial toxicity of cancer treatment: moving the discussion from acknowledgement of the problem to identifying solutions. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;20:100269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.