Abstract

The widespread COVID-19 pandemic, caused by novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, has emanated as one of the most life-threatening transmissible diseases. Currently, the repurposed drugs such as remdesivir, azithromycine, chloroquine, and hydroxychloroquine are being employed in the management of COVID-19 but their adverse effects are a matter of concern. In this regard, alternative treatment options i.e., traditional medicine, medicinal plants, and their phytochemicals, which exhibit significant therapeutic efficacy and show a low toxicity profile, are being explored. The current review aims at unraveling the promising medicinal plants, phytochemicals, and traditional medicines against SARS-CoV-2 to discover phytomedicines for the management of COVID-19 on the basis of their potent antiviral activities against coronaviruses, as demonstrated in various biochemical and computational chemical biology studies. The review consists of integrative and updated information on the potential traditional medicines against COVID-19 and will facilitate researchers to develop traditional medicines for the management of COVID-19.

Keywords: Coronavirus, COVID-19, Traditional medicines, Ayurveda, Phytochemicals

1. Introduction

The incessant COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease) pandemic, caused by a novel coronavirus strain namely, severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), has perturbed the entire human race globally since its inception in December 2019 (Ratten, 2020). The number of cases infected with COVID-19 and reported deaths have been perpetually increasing to date due to its rapid transmission and high mortality rate (Zhu et al., 2019). Presently, COVID-19 patients are being treated by providing symptomatic treatments including the use of repurposed antiviral drugs and by giving oxygen support. Since the pathophysiology of COVID-19 is complicated and no repurposed drug has provided a sure shot cure against the disease, various therapies targeting the therapeutic targets of the virus, systemic inflammation, and enhancement of the immune response would prove to be more fruitful for patients (Li et al., 2021). The current uncontrolled surge in COVID-19 cases, consequent fatalities and a dearth of potent antiviral therapy devoid of detrimental effects against SARS-CoV-2 necessitate the integration of traditional medicinal systems with modern medicine (Ahmad et al., 2021; Vellingiri et al., 2020). Since time immemorial, traditional medicine, medicinal plants, and natural products have provided an indispensable cure against the majority of ailments. Herbal medicines have also exhibited remarkable potency against innumerable viruses including Coronaviruses, Influenza virus, Human immunodeficiency virus, Zika Virus with barely any deleterious effects (Akram et al., 2018; Das et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2018; Saxena et al., 2016). The secondary metabolites derived from medicinal plants have also been reported to exhibit biological functions such as antiviral, anti-inflammatory, antifungal, antibacterial, antidiabetic, analgesic, and immunomodulatory activities (Das et al., 2021). Since the emergence of the epidemic caused by SARS-CoV-2, various medicinal plants and phytochemicals have been examined for their therapeutic potential against β-coronavirus-associated diseases (Das et al., 2021; Jin et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). It has been reported that SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 exhibit genomic homology and similarities in the pathophysiological processes therefore the effect of medicinal plants and traditional medicine on SARS-CoV may also assist in combat against COVID-19 (Li et al., 2021). The aim of the current review is to provide comprehensive information on herbal flora, traditional medicine, and phytochemicals exhibiting antiviral activities that have been investigated via in silico, in vivo, in vitro, preclinical, clinical studies and have been found to be potent against coronavirus especially, SARS-CoV-2 .

2. Methodology

A number of reports and research articles on the medicinal significance of various herbs and traditional medicines on coronavirus attracted us to compile a detailed review. In the present review, a detailed examination of medicinal herbs, their phytochemicals, and traditional medicine including their pharmacological activities with the idea of investigating the potent herbs for COVID-19 has been performed. The available information of various herbs on in vitro, in vivo, and in silico research was collected via a library and electronic searches in Sci-Finder, Pub-Med, Science Direct, ACS, RSC, Springer, Taylor & Francis, Willey & Sons, Google Scholar, etc. for the period up to 12 July 2021. Various keywords including coronavirus, COVID-19, coronavirus and natural products, coronavirus and phytomedicines, coronavirus, medicinal plants, and traditional medicineswere used to search the appropriate data and literature.

3. Structural features of SARS-CoV-2

The structural studies revealed that SARS-CoV-2 is a single-stranded, spherical, enveloped, positive-sense RNA virus with an approximate size of 125 nm and a genome size ranging from 27 kb to 32 kb (Vellingiri et al., 2020). There are four major structural proteins present in SARS-CoV-2, namely nucleocapsid protein (N), membrane protein (M), an envelope protein (E), and spike protein (S) as represented in Fig. 1 . The nucleocapsid consists of a viral genome and has a shell of an envelope surrounding it. This envelope has M, S, and E structural proteins associated with it. The membrane protein is a transmembrane glycoprotein that aids the virus in developing capsid and structure assembly. The envelope protein is responsible for the virus packaging while the spike protein aids in the entry of the virus into host cells (Naqvi et al., 2020). Although there is a similarity between the sequence homology of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, there is a difference in the transmission efficiencies of these two viruses and these contrast inefficiencies can be attributed to the difference in nucleotide sequences in spike protein and receptor binding domain (Tang et al., 2020). In a study carried out by Gordon et al. (2020), 332 interactions have been identified between SARS-CoV-2 proteins and human proteins.

Fig. 1.

Structure of SARS-CoV-2.

4. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of COVID-19

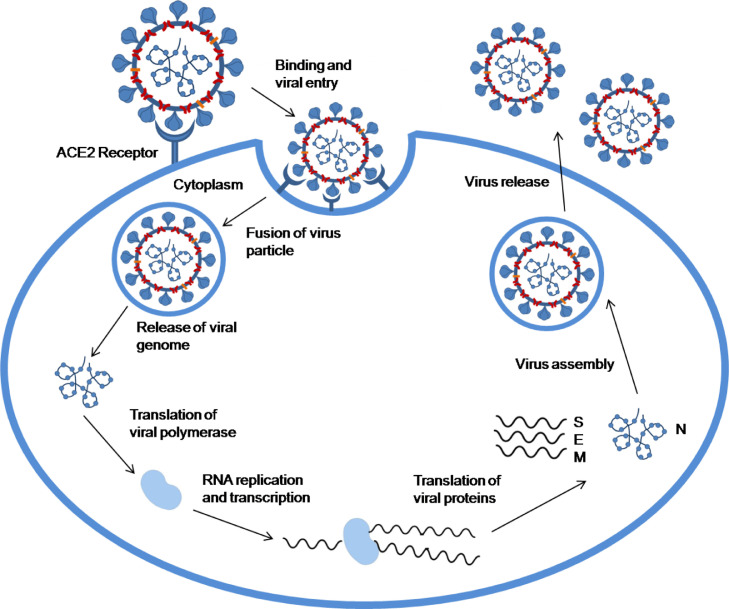

The structural studies have revealed that there is a sequence homology between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 but an appreciable difference in their transmission potential and infection range has been observed due to the difference in nucleotide sequences (Belouzard et al., 2012). Some of the major structural differences in SARS-CoV-2 as compared to SARS-CoV are longer 8b segments, shorter 3b segments, and absence of 8a segments along with a difference in Nsp-2 and −3 proteins (Vellingiri et al., 2020). The main entry of SARS-CoV-2 into host cells is similar to that of SARS-CoV i.e., recognition and binding of S proteins to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor of host cells (Fig. 2 ) (Hoffmann et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020).

Fig. 2.

Pathogenesis of COVID-19.

The Cryo-EM structure analysis revealed that SARS-CoV-2 exhibits a 10-to-20-fold higher affinity of S-protein to the human ACE2 receptor than that of SARS-CoV and thus produces more pathogenicity and has a higher infection transmission rate (Wrapp et al., 2020). Therefore, the widespread COVID-19 disease is perceived to be more dangerous with no specific treatment. The finding of ACE2 as the receptor of SARS-CoV-2 also indicates that human organs with high ACE2 expression levels, such as lung alveolar epithelial cells and enterocytes of the small intestine, are potentially the target of SARS-CoV-2 (Zhou et al., 2020). After binding, the fusion of virus particles with the host cell membrane takes place due to the conformational changes taking place in the spike protein. The process of fusion is dependent on two factors viz. proteolytic activation and pH acidification (Belouzard et al., 2012; Das et al., 2021). Once fusion takes place, cleavage of fusion protein takes place to continue the process of infection. The S-protein is homotrimeric and each of its subunits has two domains; the receptor-binding domain (S1) and the membrane fusion domain (S2) that enables the entry of the virus into the host cell. The cleavage of S protein takes place by proteases into S1 and S2 domains that facilitate the entry of the virus into the host cell (Belouzard et al., 2012). Proteases such as human airway trypsin-like protease and transmembrane protease serine family instigate the fusion of SARS-CoV-2. Some coronaviruses like SARS-CoV and MHV-2 do not require cleavage of S proteins to enter the host cells and can directly enter the host cells in the presence of exogenous proteases (Shulla et al., 2011). After the process of fusion, the fusion protein enters the host cell which results in the cleavage of ACE-2. The cleavage of ACE-2 is responsible for the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II that is a negative regulator of the renin-angiotensin pathway. Also, the reduction of ACE-2 is accountable for respiration-related diseases (Li and De Clercq, 2020). The subsequent step to the fusion of virus particles is the release of viral genome into the cytoplasm which further leads to the translation of viral polymerase namely, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Fig. 2) (RdRp). Further, the replication and transcription of viral RNA takes place resulting in the translation of accessory and structural proteins of the virus (Zhou et al., 2021). After the translation of viral protein into the host cell, numerous copies of the virus are transported by the host cell to the cell surface which further allows the virus to infect other cells (Li et al., 2021). Once the SARS-CoV-2 has infected the host cells, a well-coordinated and prompt ingrained immune response is activated (Vabret et al., 2020). The pattern recognition receptor (PRR) on the membrane of the host cells recognizes pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) of the virus which is responsible for the activation of innate immune cells such as dendritic cells, neutrophils, macrophages, and monocytes to instigate the synthesis and secretion of inflammatory cytokines (Vabret et al., 2020). In the course of viral infection, IL-6 and IL-1β, the prime pro-inflammatory cytokines that coordinate the systemic inflammation in infected individuals, facilitate inflammation in the alveoli and bronchi. The overproduction of cytokines and uncontrolled inflammatory responses are responsible for acute lung injury, respiratory disorders, the spread of infection and might contribute to the impaired immune system (Vellingiri et al., 2020). Apart from lung injury and respiratory disorders, COVID-19 is considered to be a disease affecting multiple organs including the liver, heart, and kidney that might lead to multiple organ dysfunction as SARS-CoV-2 disperses to other crucial tissues and organs after the onset of initial infection in the respiratory system. This dispersion of SARS-CoV-2 to other organs activates a complex spectrum of pathophysiological changes and symptoms (Zaim et al., 2020).

5. Therapeutic targets for identification of medicinal plants and phytochemicals against SARS-CoV-2

The identification of potent medicinal plants and phytochemicals is done on the basis of their capability to interfere with the pathogenesis of the virus and identifying their therapeutic targets (Pandey et al., 2020). Since there are two crucial stages in the coronavirus pathogenesis i.e., entry of the virus to its host cells and its replication, the potential antiviral drug must be capable of interfering either with the entry of the virus into the host cell or with one or more stages of its replication (Fig. 3 ) (Jalali et al., 2021). Some of the reported potential therapeutic targets of SARS-CoV-2 include ACE-2, 3-chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro), transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2), papain-like protease (PLpro), RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), and S proteins (Hoffmann et al., 2020; Mani et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020).

Fig. 3.

A schematic representation illustrating the role of phytochemicals in interfering with the pathogenesis of COVID-19.

Since the attachment of S-proteins of SARS-CoV-2 with ACE-2 receptor of the host cells is the entry pathway of the virus into the cell, it has been reported that ACE-2 could be one of the potential therapeutic targets as it can block the binding of the virus into the host cells (D. hai Zhang et al., 2020b). In addition to ACE-2, TMPRSS2 is also accountable for the viral cell entry as it activates the S-protein of the virus by cleaving it into two subunits namely, S1 and S2 (Belouzard et al., 2012). Both the subunits exhibit different functions as S1 binds with the surface receptor of the host cell while S2 aids in the fusion of viral cell and host cell (Belouzard et al., 2012). In various studies, it has been communicated that the inactivation of TMPRSS2 could be responsible for the inhibition of viral infection (Hoffmann et al., 2020). RdRp, also known as Nsp12, is the vital protein present in coronavirus which is responsible for the replication of virus and transcription. RdRp binds with cofactors namely, nsp7 and nsp8 and produces viral genomic RNA (Kirchdoerfer and Ward, 2019). Main protease Nsp5, also called 3CLpro or Mpro, is auto-cleaved from the polyproteins and further cleaves the nsps at 11 sites, viz., nsp4-nsp16 which is a crucial step in the mechanism of viral infection (Snijder et al., 2016). Since 3CLpro plays a crucial role in viral replication and transcription, it is regarded as one of the important therapeutic targets for COVID-19 (Khodadadi et al., 2020). Papain-like protease (PLpro) is a polypeptide that is involved in the cleavage of the N terminal region of polyprotein which results in the formation of nsp1, nsp2, and nsp3 that are required for correction of viral replication (Wu et al., 2020c). Cathepsin, a lysosomal protease, has an important role to play in cellular protein turnover (Zhou et al., 2016). Numerous studies have communicated that cathepsin B is involved in the life cycle of coronavirus and facilitates the viral entry into the cytoplasm through endosomes by undergoing fusion with viral envelope and endosomal membrane (Das et al., 2021).

6. Necessity to incorporate medicinal plants to combat COVID-19

At present, no specific and effective treatment has been discovered for this novel coronavirus disease and infected patients are being treated on the basis of symptomatic treatment protocol (Khan and Al-Balushi, 2021). The World Health organisation (WHO) has recommended preventive measures like social distancing, use of face masks and sanitizers, washing hands properly, timely diagnosis, quarantine for infected people and symptom-based treatment to curb and contain the spread of this life-threatening virus and COVID-19 disease (Khan and Al-Balushi, 2021). The uncontrolled transmission and soaring cases of morbidity and mortality due to this pandemic have put the development of effective vaccines and antiviral therapy into focus but the development of potential antiviral drugs against COVID-19 may take months or years and only a few vaccines have obtained the provisional license for their emergency use (Saggam et al., 2021). Currently, the repurposed drugs such as antivirals (e.g., remdesivir), antibiotics (e.g., azithromycin), antimalarials (e.g., chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine), and immunomodulators (e.g., tocilizumab) are being employed in the management of COVID-19 but their adverse effects are a matter of concern (Saggam et al., 2021). Therefore, in order to reduce the pressure on hospitals and healthcare infrastructure, there is a need to employ medicinal plants and traditional medicines as an alternative measure. Medicinal plants and natural products derived from them, which show a low toxicity profile, are economical and readily available, are considered to treat both principal and secondary aspects of disease in traditional medicine systems. There are innumerable medicinal plants that follow multi-component and multi-target approaches and could produce remarkable results in the prevention and management of COVID-19 (Li et al., 2021). Since SARS-CoV-2 demonstrates homology with SARS-CoV in terms of epidemiology, genomic and its pathogenesis, the medicinal plants that are proven to be effective against SARS-CoV might aid in the management of COVID-19. The low toxicity and accessibility of medicinal plants and their phytochemicals targeting SARS-CoV-2 or the host targets could be a prospective approach for managing COVID-19 (Li et al., 2021).

7. Experimental studies on traditional medicinal plants against coronaviruses

A plethora of evidence is available on the medicinal significance of various herbs and traditional medicines against coronaviruses including SARS CoV and MERS-CoV indicating their pharmacological activities (Das et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2021). For instance, medicinal plants and herbal formulations belonging to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) played an indispensable role in the prevention of SARS transmission (Ho et al., 2007; Li et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020). During 2003, the Chinese government employed the Traditional Chinese Medicines (TCM) to treat SARS-CoV disease and it has been reported that TCM was successful against SARS-CoV owing to their immune-boosting actions (Yu et al., 2012). From the literature search, it has been comprehended that phytochemicals such as flavonoids, alkaloids, anthraquinones, stilbenes, essential oils, etc. exhibit antiviral activities against SARS-CoV-2 (Das et al., 2021; Jena et al., 2021).

In an attempt to identify natural compounds associated with antiviral activities against SARS-CoV (summarized in Table 1 ), Li et al. (2005) have investigated ethanol/ chloroform extracts of 200 herbs to examine their virus-induced cytopathic effect (CPE). Out of 200 herbs, 4 herbs (Artemisia annua (whole plant), Lindera aggregate (roots), Pyrrosia lingua (leaves), and Lycoris radiata (Stem cortex) were found to be potent against SARS-CoV exhibiting 50% effective concentration (EC50) values in the range of 2.4 to 88.2 µg/ml (Li et al., 2005). In the study, Lycoris radiata was found to be the most potent against SARS-CoV and therefore its extract was further subjected to purification techniques to discover the molecule responsible for anti-coronavirus activities where an alkaloid namely, Lycorine (1), having EC50 value of 15.7 µg/ml was isolated from the ethanolic extract of Lycoris radiata (EC50 value 2.4 µg/ml) (Li et al., 2005).

Table 1.

List of major phytochemicals that exhibit antiviral activity against coronavirus screened via experimental and in silico studies.

| Phytochemical | Structure of Phytochemical | Virus | Activity | Source | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lycorine (1) |  |

SARS-CoV | EC50 value 15.7 µg/ml. | Lycoris radiate | (Li et al., 2005) |

| Saikosaponins A (2) |  |

HCoV-22E9 | Inhibition of viral attachment and penetration stages with an EC50 value of 8.6 µg/ml. | Bupleurum spp., Heteromorpha spp. and Scrophularia scorodonia | (Cheng et al., 2006) |

| Saikosaponins B2 (3) |  |

HCoV-22E9 | Inhibition of viral attachment and penetration stages with an EC50 value of 1.7 µg/ml. | Bupleurum spp., Heteromorpha spp. and Scrophularia scorodonia | (Cheng et al., 2006) |

| Saikosaponins C (4) |  |

HCoV-22E9 | Inhibition of viral attachment and penetration stages with an EC50 value of 19.9 µg/ml. | Bupleurum spp., Heteromorpha spp. and Scrophularia scorodonia | (Cheng et al., 2006) |

| Saikosaponins D (5) |  |

HCoV-22E9 | Inhibition of viral attachment and penetration stages with an EC50 value of 13.2 µg/ml. | Bupleurum spp., Heteromorpha spp. and Scrophularia scorodonia | (Cheng et al., 2006) |

| Indigo (6) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 752 µM. | Isatis indigotica root | (Lin et al., 2005) |

| β-sitosterol (7) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 1210 µM. | Isatis indigotica root | (Lin et al., 2005) |

| Sinigrin (8) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 217 µM. | Isatis indigotica root | (Lin et al., 2005) |

| Aloeemodin (9) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 366 µM. | Isatis indigotica root | (Lin et al., 2005) |

| Hesperetin (10) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 8.3 µM. | Isatis indigotica root | (Lin et al., 2005) |

| 18-hydroxyferruginol (11) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 220.8 µM. | Torreya nucifera leaves | (Ryu et al., 2010a) |

| Hinokiol (12) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 233.4 µM. | Torreya nucifera leaves | (Ryu et al., 2010a) |

| Ferruginol (13) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 49.6 µM. | Torreya nucifera leaves | (Ryu et al., 2010a) |

| 18-oxoferruginol (14) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 163.2 µM. | Torreya nucifera leaves | (Ryu et al., 2010a) |

| O-acetyl-18-hydroxyferruginol (15) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 128.9 µM. | Torreya nucifera leaves | (Ryu et al., 2010a) |

| Methyl dehydroabietate (16) |  |

SARS—CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 207 µM. | Torreya nucifera leaves | (Ryu et al., 2010a) |

| Isopimaric acid (17) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 283.5 µM. | Torreya nucifera leaves | (Ryu et al., 2010a) |

| Kayadiol (18) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 137.7 µM. | Torreya nucifera leaves | (Ryu et al., 2010a) |

| Amentoflavone (19) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 8.3 µM. | Torreya nucifera leaves | (Ryu et al., 2010a) |

| Bilobetin (20) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 72.3 µM. | Torreya nucifera leaves | (Ryu et al., 2010a) |

| Ginkgetin (21) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 32.0 µM. | Torreya nucifera leaves | (Ryu et al., 2010a) |

| Sciadopitysin (22) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 38.4 µM. | Torreya nucifera leaves | (Ryu et al., 2010a) |

| Myricetin (23) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of helicase nsP13 with an IC50 value of 2.71 µM. | Chromadex | (Yu et al., 2012) |

| Scutellarein (24) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of helicase nsP13 with an IC50 value of 0.86 µM. | Scutellaria baicalensis | (Yu et al., 2012) |

| Ferruginol (25) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition activity with an EC50 value of 1.39 µM. | Chamaecyparis obtuse var. formosana | (Wen et al., 2007) |

| 8β-hydroxyabieta-9(11),13‑dien-12-one (26) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition activity with an EC50 value of 1.57 µM. | Chamaecyparis obtuse var. formosana | (Wen et al., 2007) |

| Savinin (27) |  |

SARS-CoV | Competitive inhibition of 3CLpro with an EC50 value of 1.13 µM. | Chamaecyparis obtuse var. formosana | (Wen et al., 2007) |

| 3β,12-diacetoxyabieta-6,8,11,13-tetraene (28) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition activity with an EC50 value of > 10 µM. | Juniperus formosana | (Wen et al., 2007) |

| Betulinic acid (29) |  |

SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 | Competitive inhibition of 3CLpro of SARS-CoV with an EC50 value of 0.63 µM.In silico study based on the binding of phytochemical with major SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins (PLpro, 3CLpro and S-protein as a target point). | Juniperus formosana | (Wen et al., 2007; D. hai Zhang et al., 2020a) |

| 7β-hydroxydeoxy-cryptojaponol (30) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition activity with an EC50 value of 1.15 µM. | Cryptomeria japonica | (Wen et al., 2007) |

| Celastrol (31) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 10.3 µM. | Triterygium regelii | (Ryu et al., 2010b) |

| Pristimerin (32) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 5.5 µM. | Triterygium regelii | (Ryu et al., 2010b) |

| Tingenone (33) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 9.9 µM. | Triterygium regelii | (Ryu et al., 2010b) |

| Iguesterin (34) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with an IC50 value of 2.61 µM. | Triterygium regelii | (Ryu et al., 2010b) |

| N-trans-caffeoyltyramine (35) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of PLpro with an IC50 value of 44.4 µM. | Tribulus terrestris | (Song et al., 2014) |

| N-trans-coumaroyltyramine (36) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of PLpro with an IC50 value of 38.8 µM. | Tribulus terrestris | (Song et al., 2014) |

| N-trans-feruloyltyramine (37) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of PLpro with an IC50 value of 70.1 µM. | Tribulus terrestris | (Song et al., 2014) |

| Terrestriamide (38) |  |

SARS—CoV | Inhibition of PLpro with an IC50 value of 21.5 µM. | Tribulus terrestris | (Song et al., 2014) |

| N-trans-feruloyloctopamine (39) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of PLpro with an IC50 value of 26.6 µM. | Tribulus terrestris | (Song et al., 2014) |

| Terrestrimine (40) |  |

SARS—CoV | Inhibition of PLpro with an IC50 value of 15.8 µM. | Tribulus terrestris | (Song et al., 2014) |

| Xanthoangelol E (41) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro and PLpro with IC50 values of 11.4 µM and 1.2 µM respectively. | Angelica keiskei | (Park et al., 2016) |

| Cis/trans -dieckol (42) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CLpro with IC50 values of 2.7 µM (trans form) and 68.1 µM (cis form). | Ecklonia cava | (Park et al., 2013) |

| Procyanidin A2 (43) |  |

SARS-CoV | Antiviral activity with an IC50 value of 29.9 µM. | Cinnamomi Cortex | (Zhunag et al., 2009) |

| Procyanidin B1 (44) |  |

SARS-CoV | Antiviral activity with an IC50 value of 41.3 µM. | Cinnamomi Cortex | (Zhunag et al., 2009) |

| Emodin (45) |  |

SARS-CoV | Inhibition of the interaction between ACE2 and S-protein of SARS-CoV; IC50 values of various extracts ranging from 1 to 10 µg/ml. | Radix et Rhizoma Rhei, Radix Polygoni multiflori | (Ho et al., 2007) |

| Glycyrrhizin (46) |  |

SARS-CoV | Antiviral activity with an EC50 value >350 µg/ml. | Glycyrrhiza glabra | (Hoever et al., 2005) |

| Glycyrrhizic acid (47) |  |

SARS-CoV | Antiviral activity with an EC50 value >20 µg/ml. | Glycyrrhiza glabra | (Cinatl et al., 2003) |

| Broussochalcone A (48) |  |

SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CL pro and PLpro | Broussonetia papyrifera | (Park et al., 2017) |

| Broussochalcone B (49) |  |

SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CL pro and PLpro | Broussonetia papyrifera | (Park et al., 2017) |

| Papyriflavonol A (50) |  |

SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CL pro and PLpro | Broussonetia papyrifera | (Park et al., 2017) |

| 4-hydroxyisolonchocarpin (51) |  |

SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CL pro and PLpro | Broussonetia papyrifera | (Park et al., 2017) |

| Kazinol A (52) |  |

SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CL pro and PLpro of SARS-CoV and PLpro of MERS-CoV. | Broussonetia papyrifera | (Park et al., 2017) |

| Kazinol B (53) |  |

SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CL pro and PLpro of SARS-CoV and PLpro of MERS-CoV. | Broussonetia papyrifera | (Park et al., 2017) |

| Kazinol F (54) |  |

SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CL pro and PLpro | Broussonetia papyrifera | (Park et al., 2017) |

| Kazinol J (55) |  |

SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CL pro and PLpro | Broussonetia papyrifera | (Park et al., 2017) |

| Broussoflavan A (56) |  |

SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV | Inhibition of 3CL pro and PLpro | Broussonetia papyrifera | (Park et al., 2017) |

| Withanone (57) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Downregulates mRNA of TMPRSS2 in MCF7 cells.Interrupts the electrostatic interactions between the RBD and ACE2 | Withania somnifera | (Kumar et al., 2020c; Balkrishna et al., 2020) |

| Coumaroyltyramine (58) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | In silico study based on the binding of phytochemical with major viral proteins (PLpro, 3CLpro and S-protein as a target point). | Possible Source: Helianthus tuberosus | (D. hai Zhang et al., 2020) |

| Cryptotanshinone (59) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | In silico study based on the binding of phytochemical with major viral proteins (PLpro, 3CLpro and S-protein as a target point). | Possible Source: Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge | (D. hai Zhang et al., 2020a) |

| Desmethoxyreserpine (60) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | In silico study based on the binding of phytochemical with major viral proteins (PLpro, 3CLpro and S-protein as a target point). | Possible Source: Rauwolfia Serpentina | (D. hai Zhang et al., 2020a) |

| Dihomo-α-linolenic acid (61) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | In silico study based on the binding of phytochemical with major viral proteins (PLpro, 3CLpro and S-protein as a target point). | Possible Source: Borage | (D. hai Zhang et al., 2020a) |

| Dihydrotanshinone I (62) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | In silico study based on the binding of phytochemical with major viral proteins (PLpro, 3CLpro and S-protein as a target point). | Possible Source: Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge | (D. hai Zhang et al., 2020a) |

| Kaempferol (63) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | In silico study based on the binding of phytochemical with major viral proteins (PLpro, 3CLpro and S-protein as a target point). | Possible Source: Saffron, Aloe vera, Moringa oleifera | (D. hai Zhang et al., 2020a) |

| Lignan (64)Basic Structure |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | In silico study based on the binding of phytochemical with major viral proteins (PLpro, 3CLpro and S-protein as a target point). | Possible Source: Flaxseed and Sesame seed | (D. hai Zhang et al., 2020a) |

| Moupinamide (65) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | In silico study based on the binding of phytochemical with major viral proteins (PLpro, 3CLpro and S-protein as a target point). | Possible Source: Piper nigru | (D. hai Zhang et al., 2020a) |

| N-cis-feruloyltyramine (66) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | In silico study based on the binding of phytochemical with major viral proteins (PLpro, 3CLpro and S-protein as a target point). | Possible Source: Bell peppers | (D. hai Zhang et al., 2020a) |

| Quercetin (67) |  |

SARS—CoV-2 | In silico study based on the binding of phytochemical with major viral proteins (PLpro, 3CLpro and S-protein as a target point). | Possible Source: Broccoli, red onions, peppers, apples, grapes, black tea, green tea etc. | (D. hai Zhang et al., 2020a) |

| Sugiol (68) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | In silico study based on the binding of phytochemical with major viral proteins (PLpro, 3CLpro and S-protein as a target point). | Possible Source: Metasequoia glyptostroboides | (D. hai Zhang et al., 2020a) |

| TanshinoneIIa (69) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | In silico study based on the binding of phytochemical with major viral proteins (PLpro, 3CLpro and S-protein as a target point). | Possible Source: Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge | (D. hai Zhang et al., 2020a) |

| Platycodin D (70) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards PLpro. | Platycodon grandiflorus | (Wu et al., 2020b) |

| Baicalin (71) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards PLpro. | Scutellaria baicalensis | (Wu et al., 2020b) |

| Phaitanthrin D (72) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards PLpro. | Isatis indigotica | (Wu et al., 2020b) |

| 2,2-di(3-indolyl)−3-indolone (73) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards PLpro. | Isatis indigotica | (Wu et al., 2020b) |

| Catechin (74) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards PLpro. | Camellia sinensis, Green tea and foods etc. | (Wu et al., 2020b) |

| (–)-epigallocatechin gallate (75) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards PLpro. | Camellia sinensis, Green tea and foods etc. | (Wu et al., 2020b) |

| Chrysin-7-O-β-glucuronide (76) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards 3CLpro. | Scutellaria baicalensis | (Wu et al., 2020b) |

| Betulonal (77) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards 3CLpro and RdRp. | Cassine xylocarpa | (Wu et al., 2020b) |

| Isodecortinol (78) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards 3CLpro. | Viola diffusa | (Wu et al., 2020b) |

| Cerevisterol (79) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards 3CLpro. | Viola diffusa | (Wu et al., 2020b) |

| Hesperidin (80) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards 3CLpro. | Citrus aurantium | (Wu et al., 2020b) |

| Neohesperidin (81) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Insilico high binding affinity towards 3CLpro. | Citrus aurantium | (Wu et al., 2020b) |

| Kouitchenside I (82) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards 3CLpro. | Swertia genus | (Wu et al., 2020b) |

| Deacetylcentapicrin (83) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards 3CLpro. | Swertia genus | (Wu et al., 2020b) |

| Tinosporide (84) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards 3CLpro. | Tinospora cordifolia | (Thakkar et al., 2021) |

| Amritoside A (85) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards 3CLpro. | Tinospora cordifolia | (Thakkar et al., 2021) |

| Amritoside B (86) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards 3CLpro. | Tinospora cordifolia | (Thakkar et al., 2021) |

| Amritoside C (87) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards 3CLpro. | Tinospora cordifolia | (Thakkar et al., 2021) |

| Columbin (88) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards 3CLpro. | Tinospora cordifolia | (Thakkar et al., 2021) |

| Palmatoside F (89) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards 3CLpro. | Tinospora cordifolia | (Thakkar et al., 2021) |

| Palmatoside G (90) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards 3CLpro. | Tinospora cordifolia | (Thakkar et al., 2021) |

| Tinocordifolin (91) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | High in silico binding affinity towards 3CLpro. | Tinospora cordifolia | (Thakkar et al., 2021) |

| Tinocordiside (92) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Inhibition activity against 3CLpro and RdRp. | Tinospora cordifolia | (Sagar and Kumar, 2020) |

| Berberine (93) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Inhibition activity against 3CLpro and RdRp. | Tinospora cordifolia | (Sagar and Kumar, 2020) |

| Magnoflorine (94) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Inhibition activity against 3CLpro and RdRp. | Tinospora cordifolia | (Sagar and Kumar, 2020) |

| Isocolumbin (95) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Inhibition activity against 3CLpro and RdRp. | Tinospora cordifolia | (Sagar and Kumar, 2020) |

| Withaferin A (96) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Blocks Mpro and TMPRSS2 enzyme Inhibits RdRp with a higher binding energy than hydroxychloroquine. | Withania somnifera | (Kumar et al., 2020c; Sharma and Deep, 2020) |

| Withacoagin (97) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Exhibits higher binding affinity with viral S-protein and RdRp enzyme | Withania somnifera | (Borse et al., 2020) |

| Withanolide B (98) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Exhibits higher binding affinity with viral S-protein and RdRp enzyme | Withania somnifera | (Borse et al., 2020) |

| 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid (99) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Interaction with 3CLpro with appreciable docking score | Cressa cretica | (Shah et al., 2021a) |

| Chrysin-7-O-glucuronide (100) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Inhibits Mpro | Oroxylum indicum | (Shah et al., 2021b) |

| Scutellarein (101) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Inhibits Mpro | Oroxylum indicum | (Shah et al., 2021b) |

| Oroxindin (102) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Inhibits Mpro | Oroxylum indicum | (Shah et al., 2021b) |

| Baicalein-7-O-diglucoside (103) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Inhibits Mpro | Oroxylum indicum | (Shah et al., 2021b) |

| Andrographolide (104) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Higher docking affinity than some of the repurposed synthetic drugs | Andrographis paniculata | (Liu et al., 2020) |

| Mangiferin (105) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Exhibits high binding affinity with Mpro | Mangifera indica | (Umar et al., 2021) |

| Catechin (106) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Exhibits high binding affinity with the S-protein | Green tea | (Jena et al., 2021) |

| (–)-epigallocatechin gallate (107) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Exhibits high binding affinity with the S-protein | Green tea | (Jena et al., 2021) |

| Curcumin (108) |  |

SARS-CoV-2 | Exhibits strong binding affinity with the ACE2 of the host cell, the RBD of viral S-protein and also with the RBD-ACE2 complex. | Curcuma longa | (Jena et al., 2021) |

| Piceatannol (109) |  |

SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 | Higher binding affinity to the spike protein and ACE-2 complex | – | (Wahedi et al., 2021) |

| Resveratrol (110) |  |

SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 | Higher binding affinity to the spike protein and ACE-2 complex | – | (Wahedi et al., 2021) |

Cheng et al. (2006) examined the antiviral activity of Saikosaponins (A, B2, C, D) (2–5) isolated from three plants namely Bupleurum spp., Heteromorpha spp., and Scrophularia scorodonia and found that the selected Saikosaponins were potent against the coronavirus strain HCoV-22E9. The EC50 values of the Saikosaponins lie in the range of 1.7 to 19.9 µg/ml and Saikosaponin B2 (3) was found to be most potent with an EC50 value of 1.7 µg/ml. The mode of action of Saikosaponin B2 (3) against HCoV-22E9 strain was reported to be the inhibition of viral attachment and penetration stages (Cheng et al., 2006). Several research groups have also investigated the antiviral activity of saikosaponins against other viruses like hepatitis B viru,. herpes simplex virus, HIV, and cytomegalovirus (Bahbah et al., 2006; Cheng et al., 2006). Therefore, saponins are a class of interest among researchers to be explored for their therapeutic potential against COVID-19. The antiviral activity of saponins is attributed to their property to interact with viral envelope and capsid protein resulting in the disruption of viral particles and also, to their interaction with host cell membrane which leads to the inhibition of attachment of viral cell to the host cells which further prevents the fusion by coating the cell surface and minimizes the proliferation of infection (Das et al., 2021). In a study on the antiviral activity of saponins, it has been reported that Quillaja saponaria extract consisting of triterpenoid saponins was found to be effective against HIV-1 and HIV-2 (Roner et al., 2007). On similar lines, to explore the antiviral activities of saponins and triterpene saponin extracted from Anagallis arvensis exhibited antiviral activity against poliovirus and HSV1 (Amoros et al., 1987).

Lin et al. (2005) investigated the antiviral activity of major phytochemicals isolated from Isatis indigotica root aqueous extract against coronavirus strain SARS-CoV by utilizing cell-free and cell-based cleavage assays. The observed IC50 values of main phytochemicals namely, indigo (6), β-sitosterol (7), sinigrin (8), aloe emodin (9), and hesperetin (10) were 752 µM, 1210 µM, 217 µM, 366 µM, and 8.3 µM respectively. The mode of action proposed for Isatis indigotica root extract and its phytochemicals against SARS-CoV was the inhibition of 3CLpro (Lin et al., 2005).

Ryu et al. (2010a) examined the ethanolic extract of Torreya nucifera leaves and 12 phytochemicals isolated from it for their anti-SARS-CoV activities. The diterpenoid species namely 18-hydroxyferruginol (11), hinokiol (12), ferruginol (13), 18-oxoferruginol (14), O-acetyl-18-hydroxyferruginol (15), methyl dehydroabietate (16), isopimaric acid (17) and kayadiol (18) were isolated by the fractionation of ethanolic extract of Torreya nucifera with hexane. The observed SARS-CoV-3CLpro inhibitory activities were reported to be significant with IC50 values ranging from 49 to 284 µM. In ethyl acetate fraction, four biflavonoids were identified as amentoflavone (19), bilobetin (20), ginkgetin (21), and sciadopitysin (22) with IC50 values ranging from 8 to 39 µM. All the 12 phytochemicals exhibited appreciable inhibitory activities towards 3CLpro of SARS-CoV and out of all 12 isolated phytochemicals, amentoflavone (19) was reported to be the most potent in the inhibition of 3CLpro with a significant IC50 value of 8.2 µM and hence potent against SARS-CoV (Ryu et al., 2010a).

Yu et al. (2012) examined the inhibitory effects of 64 natural products against the activity of nsP13, SARS helicase by performing an in vitro study. Out of 64 selected phytochemicals, Myricetin (23) and Scutellarein (24) affect the ATPase activity and thus inhibit the SARS-CoV helicase nsP13. The observed IC50 values for myricetin and scutellarin isolated from Chromadex and Scutellaria Baicalensis were 2.71 µM and 0.86 µM respectively (Yu et al., 2012).

In an in vitro study, performed by Wen et al. (2007), 226 phytochemicals were assessed for anti-SARS-CoV activities. Out of the selected 226 phytochemicals, 22 were found to be potent inhibitors and the phytochemicals namely, ferruginol (25), 8β-hydroxyabieta-9(11),13‑dien-12-one (26), and savinin (27) (present in Chamaecyparis obtuse var. formosana), 3β,12-diacetoxyabieta-6,8,11,13-tetraene (28), betulinic acid (29) (from Juniperus formosana), and 7β-hydroxydeoxycryptojaponol (30) (present in Cryptomeria japonica) were demonstrated to be the most potent phytochemicals against SARS-CoV-2. In the indicated study, the concentration of 22 screened-out phytochemicals required to inhibit 50% of Vero E6 cell proliferation (CC50) and viral replication (EC50) were calculated. The observed EC50 values for SARS-CoV replication inhibition ranged from 0.63 to 1.57 µM. The inhibitory activities of the 22 phytochemicals on SARS-CoV 3CLpro were investigated and it was concluded that only savinin (27) and betulinic acid (29) exhibited significant inhibition activity on 3CLpro (Wen et al., 2007).

In 2010, Ryu and his teammates isolated four quinone-methide based triterpenes from Tripterygium regelii and evaluated them for their SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitory activities. The isolated terpenes namely, celastrol (31), pristimerin (32), tingenone (33), and iguesterin (34) exhibited appreciable SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitory activities displaying IC50 values of 10.3, 5.5, 9.9, and 2.6 l µM, respectively (Ryu et al., 2010b).

In an in vitro study conducted by Song et al. (2014), it has been manifested that the methanolic extract of Tribulus terrestris fruits exhibits potent SARS-CoV-PLpro inhibitory activity. In order to probe the phytochemicals responsible for the SARS-CoV-PLpro inhibitory activity of the extract, six cinnamic amides namely, N-trans-caffeoyltyramine (35), N-trans-coumaroyltyramine (36), N-trans-feruloyltyramine (37), terrestriamide (38), N-trans-feruloyloctopamine (39), terrestrimine (40) were isolated from the methanolic extract of Tribulus terrestris fruits. All the isolated compounds were found to be capable of inhibiting PLpro of SARS-CoV with IC50 values ranging from 15.8 to 70. l µM and amongst all, terrestrimine (40) was discovered to be the most potent inhibitor SARS-CoVPLpro with an IC50 value of 15.8 µM (Song et al., 2014).

Park et. al. (2015) isolated 9 alkylated chalcones and 4 coumarins from Angelica keiskei and examined their inhibitory activities towards 3CLpro and PLpro by using cell-free and cell-based cleavage assay. Among the isolated thirteen phytochemicals, xanthoangelol E (41), which contains perhydroxyl group, demonstrated the most potent inhibitory activities against PLpro and 3CLpro with IC50 values of 1.2 µM and 11.4 µM respectively (Park et al., 2016).

Park et al. (2013) evaluated SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitor activities of nine phlorotannins isolated from the edible brown algae Ecklonia cava. Out of nine compounds, ether-linked dieckol (42) exhibited the most potent inhibition activity towards SARS-CoV 3CLpro in cis and trans form with IC50 value 2.7 µM (trans) and 68.1 µM (cis) respectively (Park et al., 2013).

Zhunag et al. (2009) evaluated the hydro-ethanolic (50:50) extract of Cinnamomi Cortex herb and its phytochemicals isolated from butanol fractions for their antiviral activities against wild type SARS-CoV. Amongst the phytochemicals isolated from Cinnamomi Cortex, procyanidin A2 (43) and procyanidin B1 (44) exhibited moderate anti-SARS-CoV activity with IC50 values 29.9 and 41.3 µM (Zhunag et al., 2009).

Ho et al. (2007) screened 312 TCM herbs and found that three herbs belonging to Polygonacea family namely, Radix et RhizomaRhei, Radix Polygoni Multiflori, and Caulis Polygoni multiflori inhibit the interaction between S protein of SARS-CoV and ACE2. The extracts of the above-mentioned herbs demonstrated anti-SARS-CoV activity with IC50 values ranging from 1 to 10 µg/ml (Ho et al., 2007). Emodin (45), commonly found anthraquinone in Rheum and Polygonum is also responsible for the inhibition of the interaction between ACE2 and S-protein of SARS-CoV and therefore, it has been suggested in the study that Emodin (45) could be responsible for the anti-SARS-CoV activities (Ho et al., 2007).

In literature, it has been reported that phytochemicals of Glycyrrhiza glabra are potent against SARS-CoV. The two major phytochemicals namely, glycyrrhizin (46) and glycyrrhizic acid (47) exhibit more potent antiviral activity against SARS-CoV (Cinatl et al., 2003; Hoever et al., 2005). Further studies have revealed that the addition of 2-acetamido-β-D-glucopyranosylamine into the glycoside chain of glycyrrhizin (46) produced a ten-fold potency against SARS-CoV (Hoever et al., 2005).

In an in vitro study carried out to evaluate the inhibitory activity of polyphenols derived from Broussonetia papyrifera, against 3CLpro and PLpro of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, Park et al. (2017) reported that the isolated compounds i.e., broussochalcone A (48), broussochalcone B (49), papyriflavonol A (50), 4-hydroxyisolonchocarpin (51), kazinol A (52), kazinol B (53), kazinol F (54), kazinol J (55) and broussoflavan A (56) are more potent against PLpro than against 3CLpro. In the study, papyriflavonol A (50) has been concluded to exhibit the greatest inhibitory activity against PLpro demonstrating an IC50 value of 3.7 μM (Park et al., 2017).

Withania somnifera is a well-renowned medicinal herb that is known to exhibit antiviral and immunomodulatory activities (Singh et al., 2021). In literature, various researchers have examined the therapeutic potential of withanolides, the principal phytochemicals of Withania somnifera, against SARS-CoV-2 (Kumar et al., 2020c; Saggam et al., 2021). Withanolides belong to the steroidal lactone terpenoid class of compounds and include withanolide A, B, and D, withaferin A, withanone, withanoside IV and V, withasomniferin A, sitoindoside IX and X, etc. (Saggam et al., 2021). In an in vitro study carried out by Kumar et al. (2020c), it has been revealed that withanone (57) downregulates mRNA of TMPRSS2 in MCF7 cells (Kumar et al., 2020c).

The majority of studies mentioned in the review have been in vitro. The in vitro studies have been proven to be advantageous due to a number of reasons including reduction in variability of results, cost-effectiveness, and rapidity (Arora et al., 2012). The major limitations of in vitro studies include variation in biokinetics parameters and application of results to human, owing to their lesser reliability as compared to in vivo studies (Saeidnia et al., 2015). But since in vivo studies are cumbersome to carry out, screening of phytochemicals and medicinal plants on the basis of in vitro studies is appropriate and provide a roadmap for in vivo studies and further clinical studies.

8. In silico studies on phytochemicals and traditional medicinal plants against SARS-CoV-2

Numerous research groups have carried out in silico investigations on various phytochemicals of different medicinal plants exhibiting antiviral activity by docking them as ligands against therapeutic targets in the pathogenesis of SARS CoV-2 in order to explore whether the screened phytochemicals can be employed as novel agents to control SARS-CoV-2 or not so that further in vitro and in vivo studies can be conducted on their therapeutic potency and efficacy (Sagar and Kumar, 2020; Shah et al., 2021a, 2021b; Thakkar et al., 2021; D. hai Zhang et al., 2020).

In an in silico study performed to examine and explore the anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities of 125 Chinese herbs, the interaction of major SARS-CoV-2 proteins involved in its entry and replication like PLpro, 3CLpro, and S-protein was investigated against the phytochemicals of the selected herbs (D. hai Zhang et al., 2020). The preliminary step in the screening of the plants was the selection of phytochemicals proven to be effective against either SARS or MERS and their presence in the Traditional Chinese Medicine System Pharmacology Database. Further, Chinese herbal databases were searched to identify plants consisting of two or more selected phytochemicals followed by the network pharmacology analysis to predict the generally known in vivo effects of the screen out drugs. Since SARS-CoV-2 exhibits certain mutations in comparison to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, the screened phytochemicals might not be as efficacious as against the other two coronaviruses (D. hai Zhang et al., 2020). In this study, it was revealed that herbs consisting of two or more compounds like Betulinic acid (29), Coumaroyltyramine (58), Cryptotanshinone (59), Desmethoxyreserpine (60), Dihomo-α-linolenic acid (61), Dihydrotanshinone I (62), Kaempferol (63), Lignan (64), Moupinamide (65), N-cis-feruloyltyramine (66), Quercetin (67), Sugiol (68), and TanshinoneIIa (69) may be effective against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Out of 125 herbs, 26 herbs comprising two or more screened phytochemicals were found to be promising candidates against SARS-CoV-2 infection and can be classified in six categories i.e., category A to F on the basis of their possible time for usage. Category A consisted of herbs used for full course viz., Forsythiae fructus (Antipyretic detoxifying), Licorice (Qi-reinforcing), Mori cortex (Antitussive antiasthmatics), Chrysanthemi Flos (Pungent cool diaphoretics), Farfarae Flos (Antitussive antiasthmatics), Lonicerae Japonicae Flos (Antipyretic-detoxifying drugs), Mori folium (Pungent cool diaphoretics), Peucedani radix (Phlegm-resolving medicine), and Rhizomafagopyricymosi (Antipyretic detoxifying) whereas category B consisted of herbs for the early-stage course such as Radix bupleuri (Pungent cool diaphoretics), Tamaricis cacumen (Pungent-warm exterior-releasing medicine) and Erigeron breviscapus (Pungent-warm exterior-releasing medicine). Category C comprised of herbs for middle stage course include Coptidis rhizome (Heat-clearing and dampness drying medicine), Houttuynia eherba (Antipyretic-detoxifying), Hovenia Dulcis semen (Antipyretic-detoxifying), and Inulaeflos (Phlegm resolving medicine) whereas category D includes herbs for middle and later stages course such as Eriobotryae folium (Antitussive antiasthmatics), Hedysarum Multi Jugum maxim (Qi-reinforcing), Lepidii semen descurainiae semen (Antitussive antiasthmatics), Ardisia Japonica Herba (Antitussive antiasthmatics), Asteris radix et rhizoma (Antitussive antiasthmatics), Euphorbiae helioscopia herba (Diuretic dampness-excreting), and Ginkgo semen (Antitussive antiasthmatics). Category E contains herbs for later stages namely, AnemarrhenaeRhizoma (Fire-purging), and EpimediiHerba (Yang-reinforcing) and category F includes herbs for prevention namely, Fortunes boss fern rhizome (Warming interior) (D. hai Zhang et al., 2020). In another in silico study, 1066 phytochemicals including 78 frequently used antiviral drugs were screened by using the 3CLpro, PLpro, and RNA polymerase, targets with the intention to provide a pathway to develop an antidote for SARS-CoV-2 (Wu et al., 2020b). The structure of important phytochemicals 70–83 are mentioned under Table 1.

Thakkar et al. (2021) conducted an in silico study to discover the efficacy of various phytochemicals present in Tinospora cordifolia against SARS-CoV-2 main protease in comparison to the standard repurposed drugs recommended in the management of COVID-19 namely Remedesivir, Favipiravir, Chloroquine, Hydroxychloroquine and Azithromycin by docking the ligands (selected phytochemicals and repurposed drugs) to target i.e., SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Amongst the selected repurposed drugs in the study, Remdesivir and Favipiravir exhibited the highest docking score i.e., −5.85 and −6.27 respectively and hence exhibit the highest binding affinity with the target, therefore, these are considered to be the most potent molecules. In the indicated study, some of the phytochemicals of Tinospora cordifolia including Tinosporide (84), Amritoside A (85), Amritoside B (86), Amritoside C (87), Columbin (88), Palmatoside F (89), Palmatoside G (90) and Tinocordifolin (91) displayed docking scores in the range of −5.02 to 5.72 that are very close to that of Remdesivir and Favipiravir (Thakkar et al., 2021).

Sagar et al. (2020) examined the binding affinity and efficacy of four important phytochemicals of Tinospora cordifolia namely, Tinocordiside (92), Berberine (93), Magnoflorine (94) and Isocolumbin (95) against four therapeutic targets of SARS CoV-2 involved in its attachment and replication via an in silico study. The study communicated that the efficacy of the selected phytochemicals is comparable to that of renowned antiviral drugs such as Remdesivir, Lopinavir and Favipiravir (Sagar and Kumar, 2020).

A number of molecular docking studies have been carried out on the phytochemicals of Withaniasomnifera attributing to its antiviral and immunomodulatory activities in order to examine their binding affinity with therapeutic targets in the management of COVID-19 and their therapeutic potential against SARS-CoV-2 (Balkrishna et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2020c). In an in silico study carried out by Balkrishna et al., 2020 on withanone (57), it has been reported that withanone blocks the entry of SARS-CoV–2 by interrupting the electrostatic interactions between the RBD and ACE2 (Balkrishna et al., 2020). Kumar et al., 2020c carried out an in silico study using a computational molecular docking tool and concluded that withanone (57) and withaferin A (96) block Mpro and TMPRSS2 enzyme which leads to inhibition in the viral entry and replication (Kumar et al., 2020c; Sharma and Deep, 2020).

In one of the molecular docking analyses carried out by Borse et al., 2020, withacoagin (97) and withanolide B (98) have been predicted to exhibit higher binding affinity with viral S-protein and RdRp enzyme (Borse et al., 2020). In another in silico investigation, withaferin A (96) is predicted to inhibit host receptor glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78) which is found to be upregulated in COVID-19 patients (Sudeep et al., 2020). Although an ample amount of in silico studies have been carried out on the potential of withanolides in SARS-CoV-2 viral inhibition, there is limited experimental and clinical data available on the efficacy of withanolides in the management of COVID-19. Therefore, there is a need to carry out comprehensive pharmaco-mechanistic studies and systematic experiments on withanolides to examine their potency as antiviral agents in COVID-19.

Shah et al. (2021a) investigated the potential of the active chemical constituents from Cressa cretica against the SARS-CoV-2 virus by examining their binding potential to Mpro of the virus and exploring the vast conformational space of protein-ligand complexes by molecular dynamics simulations. The study highlighted those two active phytochemicals of Cressa cretica namely, 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid (99) and quercetin (67) are effective against COVID-19 in comparison to Remdesivir. These two chemical constituents displayed appreciable docking scores and interact with binding site residues of Mpro via hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds (Shah et al., 2021a).

In a molecular docking study conducted by Shah et al. (2021b), active phytochemicals present in Oroxylum indicum were examined for their binding affinity with Mpro of SARS-CoV-2. The study demonstrated that four phytochemicals namely, chrysin-7-O-glucuronide (100), scutellarein (101), oroxindin (102) and baicalein-7-O-diglucoside (103) exhibited a docking score consistent with that of Remdesivir and therefore can act as potential inhibitors of Mpro of SARS-CoV-2 (Shah et al., 2021b).

Andrographis paniculata, also known as Kariyat, is a medicinal plant commonly harvested in India and is reported to exhibit antiviral activity (Singh et al., 2021). Enmozhi et al. (2020) conducted an in silico study on andrographolide (104), an extract of Andrographis paniculata and discovered that fitted efficiently with the Mpro of SARS-CoV-2 virus thereby, inhibiting its pathogenesis (Enmozhi et al., 2020). Andrographolide (104) scored high in the docking study and its docking affinity was established to be appreciably higher than the repurposed synthetic drugs used against SARS-CoV-2 like tideglusib and a combination of lopinavir, oseltamivir, and ritonavir. Andrographolide also demonstrated notably high druggability, solubility, permeability and target accuracy in the in silico study. It has also been reported that Andrographis paniculatainhibits the elevated levels of some of the molecules involved in the SARS-CoV mechanism including caspase-1, interleukin-1β and NOD-like receptor protein-3 (NLRP3) (Liu et al., 2020).

Numerous virtual screening studies have demonstrated that a variety of flavonoids namely, kaempferol (64), mangiferin (105), amentoflavone, quercetin, isoquercetin, diosmin, hidrosmin, gallocatechin gallate exhibit strong binding affinities with Mpro enzyme, one of the most prominent therapeutic targets, and therefore, these flavonoids could be employed to treat COVID-19 patients (Anand et al., 2021; Das et al., 2021; Umar et al., 2021). Quercetin (67), a flavonoid present in fruits and vegetables, is reported to exhibit antiviral properties in numerous studies (Harwood et al., 2007). The co-administration of quercetin and vitamin C is disclosed to exert a synergistic effect in treating COVID-19 patients and this can be attributed to the synergistic antiviral, immunomodulatory and antioxidant activities along with the potential of ascorbate to recycle quercetin which leads to an increase in efficacy of quercetin against SARS-CoV-2 (ColungaBiancatelli et al., 2020). On the basis of the structural features of kaempferol (63), it is reported to exhibit greater binding stability with the N3 site in Mpro of SARS-CoV-2 (Owis et al., 2020). Some of the flavonoids including myricetin, hesperetin and caflanone demonstrate high binding affinities with the ACE-2 receptor which is responsible for viral entry into the host cells (Ngwa et al., 2020). The binding affinities of catechin (106) and (–)-epigallocatechin gallate (107), polyphenols present in green tea, have also been evaluated with SARS-Cov-2 in recent studies (Jena et al., 2021). (–)-epigallocatechin gallate is also reported to exhibit the highest binding affinity with the S-protein of SARS-CoV-2 (Anand et al., 2021). In an in silico study carried out by Jena et al. (2020), it has been communicated for the first time that catechin (106) and curcumin (108) display a strong binding affinity with the ACE2 receptor of the host cell, the receptor-binding domain of viral S-protein and also with the complex (receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the viral S-protein of SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 and thus can be considered as a prospective therapeutic agent against COVID-19 (Jena et al., 2021). It has also been revealed in the study that curcumin directly binds to the receptor-binding domain of viral S-protein whereas catechin binds with amino acid residues present near the receptor-binding domain of viral S-protein resulting in fluctuation in the amino acid residues of the receptor-binding domain and its near proximity (Jena et al., 2021).

It has also been demonstrated in numerous virtual screening studies that stilbenes disrupt the interface of spike protein and ACE-2 receptor complex resulting in the inhibition of complex formed between spike protein and ACE-2 receptor which further blocks the entry of viral cell into the host cell. There are certain stilbenes namely, piceatannol (109) and resveratrol (110) that have a higher binding affinity to the spike protein and ACE-2 complex whereas stilbenes such as pterostilbene, pinosylvin and trans-resveratrol also exhibit antiviral activity but have comparatively lower binding affinity to this complex (Wahedi et al., 2021).

The results for the application of phytochemicals against SARS-CoV-2 carried out by in silico studies the results might not always be consistent due to the significant differences in the cellular environment and the one that created in silico studies. Therefore, rigorous in vitro and in vivo studies along with the clinical trials need to be carried out in order to corroborate these predictions and comprehend their role in the management of COVID-19.

9. Traditional medicines with the possibilities to combat against COVID-19

The present scenario of the COVID-19 pandemic is an arduous challenge to the whole healthcare system since no well-established treatment protocol is available for the disease. The insufficiency of current antiviral therapy employed in the management of COVID-19 has compelled the researchers to explore therapeutic alternatives in order to provide long-term preventative and curative measures against the deadly pandemic (Patel et al., 2021). Numerous research studies have demonstrated the effectiveness and potency of various phytochemicals, herbal medicines and their formulations against viral infections and in antiviral therapy. Recent experimental studies and in silico investigations on the potency of traditional medicines against SARS-CoV-2 suggest that traditional medicines may have potential application against the COVID-19 outbreak (World Health Organization, 2004; Wu et al., 2020a).

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, various studies have supported the employment of traditional Chinese medicines (TCM) in symptom management therapy against COVID-19. China has used TCM to treat the patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 where TCM in combination with allopathic drugs were administered to more than 85% of patients infected from SARS-CoV-2 (Jin et al., 2020). The National Health Commission of China has also outlined that TCM was found to be potent in more than 60,000 COVID-19 cases (National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China, 2020). The inhibition effects of a herbal formulation named Shuanghuanglian (oral liquid) against the SARS-CoV-2 have been evaluated in a combined investigation performed by Wuhan Institute of Virology and Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica. The presence of phytochemicals like forsythin, chlorogenic acid, and baicalin, in Shuanghuanglian, has shown convincing inhibitory effects against the wide range of viruses and bacteria (Li, 2002; Lu et al., 2000). Shuanghuanglian is an immunomodulator and antiviral that can reduce the inflammation caused by viruses and bacteria (Chen et al., 2002). Another Chinese herbal formulation used against the SARS-CoV-2 was Lianhuaqingwen (capsules) that demonstrate the same medicinal properties (antiviral and anti-inflammatory) as that of Shuanghuanglian (Ding et al., 2017). It has been reported that Lianhuaqingwen significantly inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication in Vero E6 cells and markedly reduces the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, CXCL-10/IP-10 and CCL-2/MCP-1) at the mRNA levels (Runfeng et al., 2020). In the COVID-19 outbreak, the most potent and frequently used herbs are Radix glycyrrhizae (Gancao), Radix astragali (Huangqi), Radix saposhnikoviae (Fangfeng), LoniceraeJaponicaeFlos (Jinyinhua), RhizomaAtractylodisMacrocephalae (Baizhu) and Fructus forsythia (Lianqiao). It has been mentioned that the selection of herbs and herbal formulations utilized during the COVID-19 outbreak was done on the basis of the history of herbs against the SARS-CoV and H1N1 influenza (Lin et al., 2020).

Total 28 government guidelines (26 Chinese and 2 Korean) were used to recognize the herbs/ formulations for COVID-19 treatment (Lin et al., 2020). The standardized terminology approved pattern identifications (PI) and compositions of herbal drugs were used in this study. In Chinese guidelines, 8 PI and 21 herbal formulations are valid for severe stage, 8 PI and 23 herbal formulations are valid for mild stage, 11 PI and 31 herbal formulations are valid for moderate stage, and 6 PI and 23 herbal formulations are valid for the recovery stage. The Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma was the herb used at the highest level at all stages in Chinese guidelines followed by Armeniacae Semen Amarumand EpimediiHerba. In the case of Korean guidelines, 3 PI and 3 herbal formulations are valid for the severe stage, 4 PI and 15 herbal formulations are valid for the mild stage, and 2 PI and 2 herbal formulations are valid for the recovery stage (Lin et al., 2020).

On similar lines, the Indian traditional medicine system encompassing Ayurveda, Yoga, Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, Sowa-Rigpa, and Homeopathy (AYUSH), which is more than 5000 years old and well-documented system, consists of ample traditional formulations and is anticipated to exhibit more satisfactory results against COVID-19 than any other traditional medicine system (Ahmad et al., 2021). These traditional medicine systems find their basis on medical philosophies and follow a holistic treatment approach. Since the AYUSH systems have aided the nation in the management of health crises like plague, cholera and other ailments, the incorporation of Indian medicinal plants and formulations can provide new strategies towards the management of the ongoing global pandemic. In literature, innumerable medicinal plants native to India and employed in Indian Systems of Medicine have been reported to exhibit potent antiviral, anti-asthmatic, immunomodulatory and antiallergic activities. Such medicinal plants constitute an integral part of many traditional AYUSH formulations that have been used to treat respiratory disorders for centuries (Ahmad et al., 2021). The Ministry of AYUSH has recommended such traditional formulations as a prophylactic measure in the management of COVID-19. In an advisory issued by the Ministry of AYUSH, a list of drugs/ herbs/ plants relying on a three-step approach that comprises preventive and prophylactic management, symptom management of COVID-19 and add-on interventions to the conventional care has been issued (Vellingiri et al., 2020). In India, various such formulations have undergone clinical trials and some are in the clinical trial phase initiated by the Ministry of AYUSH, Ministry of Health and Family Welfares and the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) in collaboration Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) (Ahmad et al., 2021).

Ayurveda is a very renowned and ancient traditional medicinal system of India which has been curing the world for thousands of years. It is based on the ideas of “Dinacharya” - daily regimes and “Ritucharya” - seasonal regimes in order to sustain a healthy life. It provides both preventive and curative aspects of treatment for most diseases. Ayurveda's classical scriptures emphasize the upliftment and maintenance of immunity. In Ayurveda, the basic concept of treatment of any disease is the understanding of the symptomatic stages of the three Dosha i.e., body humors (Vata, Pitta and Kapha) and treating them accordingly and making them into a balancing stage which indicates the healthy condition (MN et al., 2020). Along with the prevention, Ayurveda has the potency to manage the pathophysiological condition of the patient infected with COVID-19 having mild to moderate symptoms (Kumar et al., 2020a; MN et al., 2020).

The Ministry of AYUSH has recommended various ayurvedic formulations including AYUSH-64, AYUSH Kwath, Samshamani Vati, Agasthaya Hareetaki, every now and then for the management of COVID-19. AYUSH-64, a polyherbal formulation developed by Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic Sciences (CCRAS), New Delhi, is repurposed for the management of asymptomatic, mild to moderate cases of COVID-19 owing to its antimalarial activity. The components of AYUSH-64 are Alstonia scholaris (bark), Picrorhiza kurroa (rhizome), Swertia chirayita (whole plant) and Caesalpinia crista (seed pulp) (Kumar et al., 2020b). The efficacy of AYUSH-64 has manifested to be remarkable on the basis of clinical trials conducted under joint initiative of Ministry of AYUSH and CSIR and is under the process of commercialization. In a study, conducted by Gundeti et al., 2020, it has been reported that administration of AYUSH-64 for one week manifested appreciable improvement in the symptoms of influenza without exhibiting any adverse effects (Gundeti et al., 2020).

AYUSH Kwath, a ready-made formulation in the form of powder and tablets, consists of four herbs responsible to boost immunity i.e., Cinnamomum verum J. Presl. (stem bark), Ocimum sanctum L. (leaves), Piper nigrum L. (fruit) and Zingiber officinale Roscoe (rhizome) (Gautam et al., 2020). The formulation is marketed by other names such as ‘AYUSH Joshanda’ and ‘AYUSH Kudineer’ as well. The formulation exhibits remarkable biological functions including antiviral, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory and thrombolytic activities (Singh et al., 2021).

Samshamani vati, also renowned as Guduchighanavati, is an ayurvedic formulation prepared from an aqueous extract of Tinospora cordifolia which is reported to be an immunomodulator that exhibits anti-inflammatory and antipyretic activity due to the synergistic effect of various phytochemicals (Patgiri et al., 2014). AgasthavaHareetaki, consisting of more than fifteen medicinal plants, is also being employed in the management of COVID-19 symptoms as its ingredients exhibit antiviral, immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory and anti-asthmatic activities (Ahmad et al., 2021).

The Unani system of medicine, also called Greco-Arab Medicine, is based on the concept of four conditions of living (hot, frosty, sodden and dry) and four humors of Hippocratic hypothesis viz., mucus, blood, yellow bile and dark bile (Ahmad et al., 2021). The Ministry of AYUSH has issued recommendations on various Unani formulations including Triyaq-e-Araba, Roghan-e-Baboona, Khamira-e-Banafsha, etc. from time to time for the management of COVID-19 symptoms (Ahmad et al., 2021). Triyaq-e-Araba, one of the foremost Unani formulations, comprises Bergenia ciliata (stem), Laurus nobilis (berries), Commiphoramyrrha and Aristolochia indica (root) and is reported to exhibit remarkable antiviral activity against SARS-CoV (Loizzo et al., 2008). Roghan-e-Baboona, an Unani remedy, consists of flowers of Matricaria chamomilla and is employed as an antiasthmatic and is utilized to treat inflammatory complaints because of the potency of M. chamomilla flowers against sore throat (Kyokong et al., 2002). Khamira-e-Banafsha, a semi-solid Unani formulation, consists of decoction of flowers of Viola odorata as a principal ingredient and is widely used to treat acute respiratory ailments. Another significant Unani polyherbal formulation, Sharbat-e-Sadar, comprising Trachyspermum ammi as a chief ingredient, is commonly used to treat acute respiratory diseases (Ahmad et al., 2021). Roy et al. (2015) have reported that Trachyspermum ammi neutralizes antibodies for the Japanese encephalitis virus (Roy et al., 2015). Asgandh Safoof has also been recommended in the Unani system of medicine as the root powder of Asgand (Withania somnifera) is reported to exhibit immunomodulatory activity and its extract enhances CD4+ and CD8+ counts and improves blood profile, especially platelet and WBC counts (Agarwal et al., 1999). The aqueous suspension of Withania somnifera disturbs the binding between the ACE2 receptor and host viral S-protein binding domain and thus prevents the viral entry into the host cell (Balkrishna et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2020c).

Numerous formulations renowned in the Siddha system of medicines including Kabasura Kudineer, Nilavembu Kudineer, and Ahatodai Manapagu, have also been suggested by the Ministry of AYUSH for the management of COVID-19 symptoms (Mahadevan andPalraj, 2016). Kabasura Kudineer is a conventional Siddha polyherbal formulation used in the management of various acute respiratory ailments. It consists of more than ten medicinal plant ingredients that individually are used to treat respiration-related diseases. Kabasura Kudineer has also been recommended by the Ministry of AYUSH, India for the prevention and management of COVID-19 (Ahmad et al., 2021).

Ramaswamy et al. (2021) conducted a single-center and retrospective study on the patients infected with COVID-19 admitted to SRM Medical College Hospital and Research centre, Chennai, in order to investigate the effects of integrated therapy for COVID-19 using Kabasura Kudineer on the virological clearance and length of stay in hospital. The results of the study communicated that the administration of Kabasura Kudineer along with the standard treatment protocol exhibited striking outcomes in terms of virologic clearance, reduction in the hospital stay length and did not possess any significant adverse effect on the patients (Meenakumari et al., 2021). Nilavembu Kudineer, another polyherbal Siddha formulation, is reported to act as an immunomodulator and exhibits antiviral and antimicrobial activities as its constituents are potent antiviral and immune booster agents (Mahadevan and Palraj, 2016).

10. Conclusion and future prospects

In the present review, various medicinal plants, traditional medicines and phytochemicals that can interfere with the COVID-19 pathogenesis via inhibition of entry of SARS-CoV-2 into the host cell and replication have been summarized in an attempt to explore phytomedicine resources for the prevention and management of COVID-19. In a short span of time, numerous research studies have been carried out on various traditional medicines and phytochemicals using computational chemical biology techniques and biochemical techniques in order to screen out potent therapeutics against SARS-CoV-2. Since the inception of COVID-19 outbreak, various countries with a rich traditional medication history including China, India, and South Korea have recommended traditional medicines for the management of COVID-19. SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 exhibit genomic homology and similarities in the pathophysiological processes, therefore, the effect of medicinal plants and traditional medicine on SARS-CoV has also been included as they may also assist in combat against COVID-19. In silico studies may be inadequate evidence of direct SARS-CoV-2 activities of the phytochemicals. The application of phytochemicals against SARS-CoV-2 is deciphered by carrying out molecular docking studies and network pharmacology analysis; the results might not always be consistent. Therefore, rigorous in vitro and in vivo studies along with the clinical trials need to be carried out in order to corroborate these predictions and comprehend their role in the management of COVID-19.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

Central Ayurveda Research Institute, Jhansi and Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic Sciences, New Delhi – 110058, India are highly acknowledged for the facilities like library and internet provided to compile this study.

Edited by Dr S. Nile

References

- Agarwal R., Diwanay S., Patki P., Patwardhan B. Studies on immunomodulatory activity of Withaniasomnifera (Ashwagandha) extracts in experimental immune inflammation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999;67:27–35. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(99)00065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad S., Zahiruddin S., Parveen B., Basist P., Parveen A., Gaurav Parveen R., Ahmad M. Indian medicinal plants and formulations and their potential against COVID-19–preclinical and clinical research. Front. Pharmacol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.578970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akram M., Tahir I.M., Shah S.M.A., Mahmood Z., Altaf A., Ahamd K., Munir N., Daniyal M., Nasir S., Mehboob H. Antiviral potential of medicinal plants against HIV, HSV, influenza, hepatitis, and coxsackievirus: a systematic review. Phytother. Res. 2018;32:811–822. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoros M., Fauconnier B., Girre R.L. In vitro antiviral activity of a saponin from Anagallis arvensis, Primulaceae, against herpes simplex virus and poliovirus. Antiviral Res. 1987;8:13–25. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(87)90084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand A.V., Balamuralikrishnan B., Kaviya M., Bharathi K., Parithathvi A., Arun M., Senthilkumar N., Velayuthaprabhu S., Saradhadevi M., Al-Dhabi N.A., Arasu M.V., Yatoo M.I., Tiwari R., Dhama K. Medicinal plants, phytochemicals, and herbs to combat viral pathogens including sars-cov-2. Molecules. 2021;26:1775. doi: 10.3390/molecules26061775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora S., Rahwade J.M., Paknikar K.M. Nanotoxicology and in vitro studies: the need of the hour. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2012;258:151–165. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkrishna, A., POKHREL, S., Singh, J., Varshney, A., 2020. Withanone from Withaniasomnifera May Inhibit Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Entry by Disrupting Interactions between Viral S-Protein Receptor Binding Domain and Host ACE2 Receptor. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-17806/v1.

- Belouzard S., Millet J.K., Licitra B.N., Whittaker G.R. Mechanisms of coronavirus cell entry mediated by the viral spike protein. Viruses. 2012;4:1011–1033. doi: 10.3390/v4061011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borse S., Joshi M., Saggam A., Bhat V., Walia S., Sagar S., Chavan-Gautam P., Tillu G. Ayurveda botanicals in COVID-19 management: an in silico- multitarget approach. PLoS ONE. 2020;16 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-30361/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Zack Howard O.M., Yang X., Wang L., Oppenheim J.J., Krakauer T. Effects of Shuanghuanglian and Qingkailing, two multi-components of traditional Chinese medicinal preparations, on human leukocyte function. Life Sci. 2002;70:2897–2913. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(02)01541-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]