Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

The association between menopause and incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) is controversial. We evaluated the relationships of estrogen deficiency (ovarian reproductive aging) assessed by age at natural menopause (ANM), chronological aging, and antecedent CVD risk factors (biological aging) with left ventricular (LV) structure and function among women transitioning from pre- to postmenopause.

METHODS:

We studied 771 premenopausal women (37% Black) from the CARDIA Study with echocardiographic data in 1990-1991 (mean age: 32 years) who later reached natural menopause by 2015-2016 and had repeated echocardiographic measurements. Linear regression models were used to evaluate the association of ANM with parameters of LV structure and function.

RESULTS:

Mean ANM was 50 (± 3.8) years and the average time from ANM to the last echocardiograph was 7 years. In cross-sectional analyses, a one-year increase in ANM was significantly associated with lower postmenopausal LV mass (LVM), LVM indexed to body surface area (LVMI), LV mass-to-volume ratio, and relative wall thickness. In age-adjusted longitudinal analyses, higher ANM was inversely associated with pre- to postmenopausal changes in LVM (β= −0.97; 95%CI: −1.81 to −0.13, p=0.024) and LVMI (β= −0.48; 95%CI: −0.89 to −0.07, p=0.021). Controlling for baseline LV structure parameters and traditional CVD risk factors attenuated these associations. Further adjustment for hormone therapy uses didn’t alter these results.

CONCLUSION:

In this study, premenopausal CVD risk factors attenuated the association of ANM with changes in LV structure parameters. These data suggest that premenopausal CVD risk factors may predispose women to elevated future CVD risk more than ovarian aging.

Keywords: Left ventricles, echocardiography, epidemiology, menopause, women

INTRODUCTION

The independent association between natural menopause and incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) is controversial, and the underlying mechanisms are not well understood 1.. The unique and interrelated roles that endogenous estrogen deficiency (ovarian reproductive aging) indicated by age at menopause, chronological aging, and antecedent CVD risk factors (biological aging) in the pathophysiology of CVD are not well studied.

Several studies have shown an inverse association of age at natural menopause (ANM) with incident coronary heart disease 2, stroke 2,3 and heart failure 4-6. A greater proportion of women than men are diagnosed with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, a condition that represents about half of all heart failure cases and has no known proven effective management 7,8. Echocardiographic parameters of left ventricular (LV) structure and function are known to be important predictors of several future CVD events, especially heart failure 9-11. However, evidence for the long-term effect of ANM on changes in cardiac structure and function, a marker of subclinical CVD, as women transition through menopause are lacking. A few studies, mostly of small samples suggest that postmenopausal women have more LV systolic and diastolic dysfunction than premenopausal women 12-15. Exploratory analysis from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) showed that higher ANM was associated with lower LV mass to volume ratio among 272 Chinese-Americans postmenopausal women 5. All these studies reported cross-sectional associations with some of them matching postmenopausal women to premenopausal women by chronological age.

Further evidence from longitudinal studies is needed to clarify whether pre- to postmenopausal changes in cardiac structure and function are primarily due to either endogenous estrogen deficiency (ovarian aging), chronological aging or cardiovascular disease risk factors occurring in the premenopausal years (biological aging). The objective of this study was to investigate the association of ANM with changes in markers of subclinical cardiovascular disease, namely LV structure and function, during pre- to postmenopausal transition, while controlling for chronological age and antecedent (premenopausal) and time-varying changes in CVD risk factors.

METHODS

Study population

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study is an ongoing multi-center longitudinal study conducted at four US communities (Birmingham, Alabama; Chicago, Illinois; Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Oakland, California) to study cardiovascular disease risk trends and clinical sequelae from young adulthood. At year 0 (1985 to 1986), 5115 healthy adults were recruited from the general population to be balanced on sex, race (White or Black), age (18-24 or 25-30 years) and education (high school or less, or more than high school). Since then, eight follow-up examinations have occurred at years 2, 5, 7, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 with 71% of the surviving cohort attending the year 30 exam. Data collection and follow-up protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each field center with all participants providing written informed consent. Details of the study design, recruitment, methodology, and baseline characteristics are described elsewhere 16.

Measures

At every CARDIA exam, standardized protocols were used to collect information on demographics (CARDDIA Sociodemographic Questionnaire), anthropometrics, lifestyle and behavioral factors (CARDIA Tobacco and Alcohol Use Questionnaires), medical history (CARDIA Medical History Questionnaire), family history of heart disease (CARDIA Family History Questionnaire), chemistries, and medication use (CARDIA Medical History Questionnaire) from participants. Women were additionally asked if they were currently pregnant or breastfeeding, number of births, their age at menarche, regularity of their menstrual period, gynecological surgeries and use of oral contraceptives or hormone therapy for menopausal symptoms (CARRDIA Women's Reproductive Health Questionnaire). Women reporting no menstrual cycles within the previous 12 months prior to their follow-up exam were considered postmenopausal in accordance with the World Health Organization criteria 17. Among postmenopausal women, those who reported cessation of menstrual bleeding not preceded by bilateral oophorectomy, hysterectomy, radiation or chemotherapy were classified as having natural menopause. ANM was defined as self-reported age at natural cessation of menstruation.

Blood pressure was measured with participants seated and after 5 minutes of rest. The average of the second and third consecutive measurements was used for analysis. Cigarette smoking was assessed by means of an interviewer-administered tobacco questionnaire 18. Body mass index was calculated by dividing measured weight in kilograms by height in meters squared. Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm at the level of the umbilicus. Physical activity level was assessed using a modified version of the Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire, with total scores representing total moderate-to-vigorous activity expressed in exercise units 19. Lipid levels were assessed from fasting blood. Plasma total cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol were measured enzymatically by Northwest Lipid Research Laboratories (Seattle, Washington). Diabetes was defined by one or more of the following: fasting serum glucose levels ≥ 126 mg/dL, oral glucose tolerance test ≥ 200 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1C ≥ 6.5%; or self-reported use of diabetes medications.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed on the entire cohort at the year 5 (1990-1991), year 25 (2010-2011) and year 30 (2015-2016) exams. Echocardiography was performed using standardized protocols based on the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines 20. At year 5, echocardiography was performed using an ACUSON cardiac ultrasound system (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Malvern, Pennsylvania) while Artida™ ultrasound system (Toshiba Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan) was used at follow-up exams. At the follow-up exams, both two-dimensional and three-dimensional imaging were performed. Three-dimensional images were obtained using a matrix array PST-25SX 2.0-4.0 MHz transducer in a single breath hold over four consecutive cardiac cycles. Quality control and reproducibility profile of the CARDIA echocardiography exams have been previously described 21-23. Left ventricular mass (LVM) was calculated using the Devereux formula 24 and indexed to body surface area (LVMI). LV mass-to-volume ratio (LVMVR) was calculated by dividing LVM by LV end-diastolic volume. Cardiac output was determined as the product of stroke volume and heart rate. LV ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated as the ratio of stroke volume to end-diastolic volume. E/A ratio was calculated as the ratio of mitral peak early (E) to late (A) diastolic filling velocity. Left atrial volume was derived using the formula LA volume = π/6 × MMLAD × A4LAAD, where MMLAD is the M-mode LA diameter and A4LAAD is the 2-dimensional area of the left atrium in the apical 4-chamber view 25. Left atrial volume was indexed to body surface area (LAVI). These parameters of LV structure and function were selected a priori for the current study.

Sample selection

Premenopausal women who attended the 1990-1991 visit and had any other follow-up visits where echocardiography was performed were eligible for the current study. For women who did not attend the year 30 exam but were post-menopausal at the year 25 exam, echocardiographic information obtained at the year 25 exam were assigned as their end of follow-up measurements. Of the 2787 women enrolled in 1985-1986, 1720 non-pregnant premenopausal women without valvular disease at the year 5 (1990-1991) exam (baseline for this analysis) met the above eligibility criteria. The following exclusions were made: women who were premenopausal the time of their last echocardiography exam (n=314), women with surgical menopause or unknown menopausal status (n=561), and women with irregular menses or no menses due to other conditions such as chemotherapy, endometrial ablation or long-acting injectable contraception (n=74). This resulted in an analytic sample of 771 premenopausal women with echocardiographic data in 1990-1991 who later reached natural menopause by 2015-2016 and had additional echocardiographic assessments at either Year 25 or Year 30.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics at baseline (premenopause) and end of follow-up (post-menopause) were described using McNemar's test for categorical variables and paired t test for continuous variables. Cross-sectional analysis at the end of follow-up were performed to evaluate the association of ANM with echocardiography parameters of LV structure and function. Longitudinal analyses of the association of ANM with changes in echocardiography parameters of LV structure and function from premenopause to post-menopause were also conducted. Both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses were performed using general linear regression models. In all analyses, age-adjusted and multivariable-adjusted models were performed. Age adjusted analysis also included adjustment for time elapsed between echocardiographic scans to account for chronological age. Multivariable models were adjusted for LV structure and function parameters measured at baseline, age, time elapsed between echocardiographic scans, race, center, education, smoking status, oral contraceptive use, parity, age at menarche, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, physical activity, total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol. Further adjustment for postmenopausal hormone therapy use, and pre- to postmenopausal changes in systolic blood pressure, body mass index and total cholesterol were also made. Additional analyses were performed comparing parameters of LV structure and function between women who reached menopause <50 years of age and those who reported ANM ≥ 50 years. ANM of 50 years was chosen since that was the mean age women reached natural menopause in this cohort. Tests for interaction between ANM and race for each echocardiography parameter were undertaken and found to not meet statistical significance (p > 0.05). Potential nonlinear relations between ANM and echocardiography parameters were evaluated using restricted cubic splines. Because all hypothesized tests were prespecified, adjustment for multiple testing was not performed. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the mediation for ANM on the association of premenopausal parameters of LV structure and function with postmenopausal LV structure and function, adjusting for baseline, age, race, center, education, smoking status, oral contraceptive use, parity, age at menarche, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, physical activity, total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol. Statistical significance of the indirect effects of ANM were determined if the 95% confidence intervals estimated using non-parametric bootstrap methods with 10,000 samples did not contain zero 26. All statistical tests were two-sided and performed at the 0.05 level of significance using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Description of study participants at baseline and follow-up

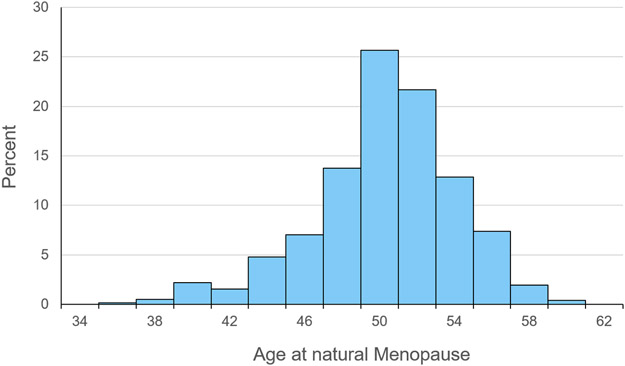

Descriptive statistics for the cohort are presented in Table 1. At baseline, the mean age of the participants was 31.8 ±2.9 years, with 37% of them reporting Black race. The average age at menarche of participants was 12.6 ±1.7 years, with 23.0% of them reporting current use of oral contraceptives at baseline. As expected, the prevalence of anti-hypertensive medication use, lipid-lowering medication use, diabetes and family history of heart attack was low at baseline. The average age at natural menopause was 50 ± 3.8 years with almost 10% of participants reaching menopause at ≤ 45 years of age (Figure 1). The average time from the onset of menopause to the last echocardiography assessment during the postmenopausal years was 6.8 ±4.2 years. While levels of systolic blood pressure, body mass index, waist circumference, HDL- and total cholesterol as well as the proportion of participants using lipid-lowering and anti-hypertensive medications increased significantly from pre- to postmenopause, the proportion of participants who were nulliparous or current smokers decreased, as did mean physical activity levels, from the premenopausal years to the postmenopausal years. Approximately 9% of women reported currently using hormone therapy at the end of follow-up.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 771 participants at baseline and at the end of follow-up, CARDIA study 1990-91 to 2015-16 a

| Characteristics | Baseline (Premenopausal) |

End of follow-up (Postmenopausal) |

|---|---|---|

| Race, black % | 36.5 | 36.5 |

| Age, years | 31.8 (2.9) | 56.4 (3.1) |

| > High school education | 75.6 | 80.9 |

| Current smoker, % | 24.6 | 12.3 |

| Parity, % | ||

| 0 | 48.4 | 29.1 |

| 1 | 22.6 | 20.0 |

| 2 | 17.3 | 29.3 |

| 3+ | 11.8 | 21.7 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 103.4 (10.4) | 117.7 (17.2) |

| Anti-hypertensive medication use, % | 1.7 | 28.5 |

| Family history of heart attack. % | 1.2 | 32.8 |

| Diabetes, % | 0.1 | 11.8 |

| Physical activity, exercise units | 330 (250) | 292 (241) |

| Body mass Index, kg/m2 | 25.5 (6.4) | 29.9 (7.8) |

| Waist circumference, com | 76.9 (12.5) | 90.8 (16.9) |

| Lipid-lowering medication use, % | 0.3 | 17.8 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL | 58.4 (13.6) | 67.8 (18.7) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 176.5 (30.6) | 201.1 (35.6) |

Values are mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables.

Pre- to postmenopausal differences for all factors listed were statistically significant (p<0.001)

Figure 1.

The distribution of age at natural menopause among the 771 participants, the study 1990-91 to 2015-16.

Cross-sectional analyses

Table 2 provides a description of the parameters of LV structure and function measured at baseline (premenopause) when all participants were premenopausal as well as at the end of follow-up when all participants had reached natural menopause (postmenopause). There was no significant association between ANM with parameters of LV structure and function at baseline (Supplemental Digital Content 1). However, ANM was associated with parameters of LV structure at the end of follow-up. After controlling for age and time elapsed between echocardiographic scans, a one-year increase in ANM was associated with reduced LVM (β = −0.98, 95% CI: −1.83 to −0.13, p = 0.024), LVMI (β = −0.48, 95% CI: −0.86 to −0.10, p=0.013), LV mass/ volume ratio (β = −0.012, 95% CI: −0.020 to −0.004, p=0.002) and relative wall thickness (β = −0.002, 95% CI: −0.004 to −0.001, p=0.011) (Supplemental Digital Content 1). Additional adjustment for factors measured at baseline (race, center, education, smoking status, oral contraceptive use, parity, age at menarche, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, physical activity, total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol) resulted in the associations of ANM with LV structure parameters being no more statistically significant (Supplemental Digital Content 1).

Table 2.

Unadjusted mean (standard error) echocardiographic parameters of left ventricular structure and function at premenopause, postmenopause and pre- to postmenopausal change (25-year change on average), CARDIA study 1990-91 to 2015-16

| Premenopause | Postmenopause | Pre- to postmenopausal change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | P value a | |

| LV Structure | ||||

| LV Mass (g) | 129.6 (1.3) | 140 (1.6) | 19.6 (1.6) | < 0.001 |

| LV Mass Index (g/m2) | 74.0 (0.6) | 79.6 (0.7) | 5.9 (0.8) | < 0.001 |

| LV Mass/ Volume Ratio | 1.20 (0.01) | 1.44 (0.01) | 0.23 (0.02) | < 0.001 |

| Relative Wall Thickness | 0.34 (0.00) | 0.37 (0.00) | 0.04 (0.00) | < 0.001 |

| LV Systolic Function | ||||

| Cardiac Output (L/min) | 4.62 (0.07) | 4.73 (0.05) | −0.50 (0.08) | 0.679 |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 63.9 (0.4) | 61.0 (0.2) | −2.7 (0.4) | < 0.001 |

| LV Diastolic Function | ||||

| E/A Ratio | 1.79 (0.02) | 1.15 (0.05) | −0.64 (0.02) | < 0.001 |

| LA Volume Index (ml/m2) | 15.4 (0.2) | 25.5 (0.3) | 10.3 (0.4) | < 0.001 |

P value comparing changes in measures from premenopause to postmenopause

E/A: mitral ratio of peak early (E) to late (A) diastolic filling velocity; LV: Left ventricular.; LA: Left atrial, SE: Standard error.

Longitudinal analyses

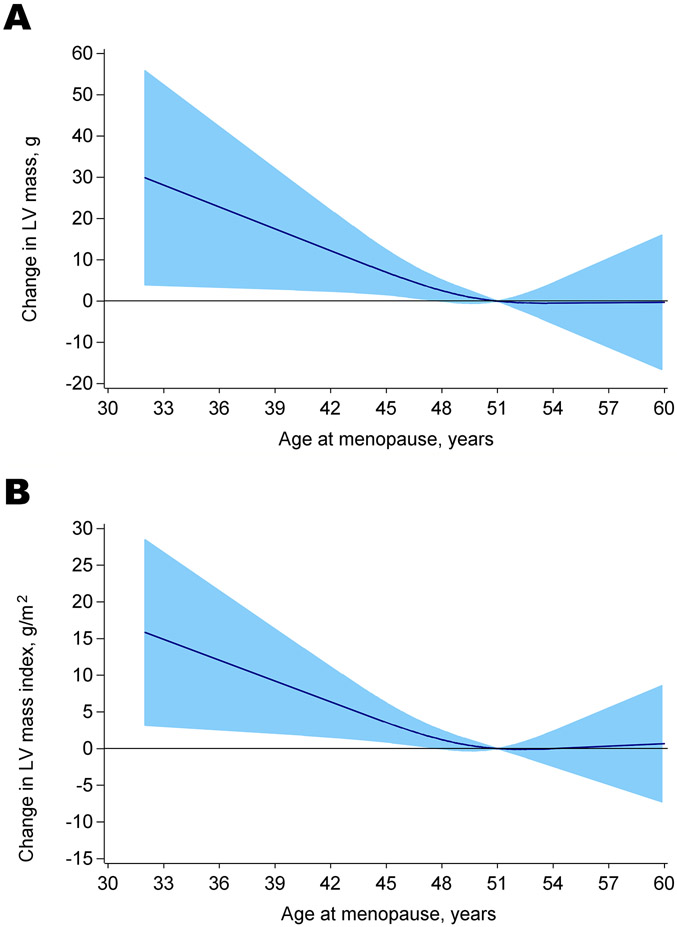

With the exception of cardiac output, all of the other echocardiographic parameters of LV structure and function changed significantly from baseline to the end of follow-up (Table 2). LVM, LVMI, LV mass/ volume ratio, relative wall thickness and LAVI all increased from pre- to postmenopause while LV ejection fraction and E/A ratio decreased from pre- to postmenopause. In models adjusted for age and time elapsed between echocardiographic scans, ANM was inversely associated with greater change in LV structure parameters. For instance, a one-year increment in ANM was associated with 0.97 g decrease in LVM and 0.48 g/m2 decrease in LVMI. (Table 3). ANM was not associated with other measures of LV structure, or with systolic or diastolic function measures. The association of ANM with LVM and LVMI was fairly linear, with results from restricted cubic spline analysis confirming these findings (Figure 2). The p value for the test for departure from linearity was 0.267 for LVM and 0.179 for LVMI. After adjusting for baseline measures of LV structure and function parameters, significant associations of ANM were still observed with LVM and LVMI, as well as LVMVR (Table 3). Further adjustment for baseline (premenopause) education, center, race, smoking status, oral contraceptive use, parity, age at menarche, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, physical activity, total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol, attenuated the association of ANM with these LV structure parameters, with the exception of Left atrial volume index (Table 3). Additional adjustment for hormone therapy use, and pre- to postmenopausal changes in systolic blood pressure, body mass index, and total cholesterol menopause did not significantly alter these results (Supplemental Digital Content 2). Similar findings were observed when changes in parameters of LV structure and function were compared between women who reached natural menopause before 50 years and women who reached menopause at or after 50 years of age (Table 4). In models adjusted for age and time elapsed between echocardiographic scans, women with ANM < 50 years had greater changes in LVM and LVMI than women with ANM ≥ 50 years. However, these differences were attenuated and were no more statistically significant with adjustment of baseline traditional CVD risk factors and measures of LV structure and function (Supplemental Digital Content 3). Results of the longitudinal analyses were largely consistent with results from the sensitivity analyses where there was no significant mediation of ANM on the association of premenopausal parameters of LV structure and function with postmenopausal LV structure and function, adjusting for baseline covariates (Supplemental Digital Content 4).

Table 3.

Adjusted associations of age at natural menopause with pre- to postmenopausal 25-year changes in parameters of left ventricular structure and function, CARDIA study 1990-91 to 2015-16

| Age-adjusted Δ a | Age a +baseline cardiac measure Δ | Multivariable-adjusted Δ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95%CI) | P value | β (95%CI) | P value | β (95%CI) | P value | |

| LV Structure | ||||||

| LV Mass (g) | −0.97 (−1.81 to −0.13) | 0.024 | −0.95 (−1.73 to −0.18) | 0.016 | −0.24 (−1.01 to 0.53) | 0.537 |

| LV Mass Index (g/m2) | −20.48 (−0.89 to −0.07) | 0.021 | −0.46 (−0.83 to −0.10) | 0.012 | −0.21 (−0.58 to 0.17) | 0.281 |

| LV Mass/ Volume Ratio | −0.009 (−0.022 to 0.004) | 0.162 | −0.010 (−0.022 to 0.001) | 0.077 | −0.003 (−0.015 to 0.010) | 0.692 |

| Relative Wall Thickness | −0.001 (−0.002 to 0.001) | 0.465 | −0.002 (−0.003 to −0.000) | 0.040 | −0.001 (−0.002 to 0.001) | 0.304 |

| LV Systolic Function | ||||||

| Cardiac Output (L/min) | −0.000 (−0.043 to 0.043) | 0.999 | −0.012 (−0.044 to 0.019) | 0.437 | −0.008 (−0.041 to 0.026) | 0.660 |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 0.07 (−0.18 to 0.31) | 0.587 | −0.10 (−0.26 to 0.05) | 0.199 | −0.05 (−0.22 to 0.13) | 0.578 |

| LV Diastolic Function | ||||||

| E/A Ratio | 0.002 (−0.008 to 0.011) | 0.745 | 0.001 (−0.005 to 0.007) | 0.694 | −0.002 (−0.008 to 0.004) | 0.541 |

| LA Volume Index (ml/m2) | −0.16 (−0.34 to 0.03) | 0.102 | −0.17 (−0.35 to 0.01) | 0.058 | −0.20 (−0.40 to −0.01) | 0.040 |

E/A: mitral ratio of peak early (E) to late (A) diastolic filling velocity; LV: Left ventricular.; LA: Left atrial

Adjusted for age and time in-between echocardiographic measures to account for chronological age

Multivariable model adjusted for baseline measures (corresponding cardiac measure, age, race, center, education, smoking status, oral contraceptive use, parity, age at menarche, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, physical activity, total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol).

Figure 2.

Restricted cubic spline depicting age-adjusted relationships between age at natural menopause and pre- to postmenopausal changes (25-year change on average) in (A) left ventricular mass and (B) left ventricular mass indexed to body surface area

Table 4.

Unadjusted mean (standard error) in echocardiographic parameters of left ventricular structure and function according to age at natural menopause, CARDIA study 1990-91 to 2015-16

| Premenopause | Postmenopause | Pre- to postmenopause 25-year change |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 50 Mean (SE) |

≥ 50 Mean (SE) |

P value | < 50 Mean (SE) |

≥ 50 Mean (SE) |

P value | < 50 Mean (SE) |

≥ 50 Mean (SE) |

P value | |

| LV Structure | |||||||||

| LV Mass (g) | 128.9 (2.0) | 130.1(1.7) | 0.652 | 151.0 (2.5) | 146.0 (2.1) | 0.133 | 24.0 (2.5) | 16.6 (2.1) | 0.023 |

| LV Mass Index (g/m2) | 73.7 (0.9) | 74.3 (0.8) | 0.650 | 81.1 (1.1) | 78.6 (0.9) | 0.091 | 7.9 (1.2) | 4.5 (1.0) | 0.036 |

| LV Mass/ Volume Ratio | 1.20 (0.02) | 1.19 (0.02) | 0.813 | 1.48 (0.02) | 1.42 (0.02) | 0.024 | 0.25 (0.04) | 0.22 (0.03) | 0.536 |

| Relative Wall Thickness | 0.34 (0.00) | 0.34 (0.00) | 0.911 | 0.38 (0.00) | 0.37 (0.00) | 0.121 | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.03 (0.00) | 0.226 |

| LV Systolic Function | |||||||||

| Cardiac Output (L/min) | 4.63 (0.11) | 4.61 (0.09) | 0.911 | 4.83 (0.08) | 4.66 (0.06) | 0.105 | −0.56 (0.10) | −0.46 (0.12) | 0.511 |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 64.2 (0.6) | 63.7 (0.5) | 0.503 | 60.9 (0.3) | 61.1 (0.3) | 0.673 | −2.7 (0.7) | −2.6 (0.6) | 0.909 |

| LV Diastolic Function | |||||||||

| E/A Ratio | 1.80 (0.03) | 1.78 (0.02) | 0.477 | 1.15 (0.02) | 1.15 (0.02) | 0.852 | −0.65 (0.03) | −0.63 (0.02) | 0.430 |

| LA Volume Index (ml/m2) | 15.8 (0.3) | 15.1 (0.3) | 0.083 | 25.9 (0.4) | 25.3 (0.4) | 0.226 | 9.9 (0.6) | 10.5 (0.5) | 0.426 |

E/A: mitral ratio of peak early (E) to late (A) diastolic filling velocity; LV: Left ventricular; LA: Left atrial; SE: Standard error

DISCUSSION

In this study in which echocardiographic assessments were conducted approximately 25 years apart, significant changes in LV structure and function were observed when comparing premenopausal to postmenopausal assessments. ANM was inversely associated with changes in parameters of LV structure after adjusting for baseline age and parameters of LV structure and function. However, this association was not statistically significant after adjustments were made for premenopausal traditional CVD risk factors. These findings suggest that premenopausal CVD risk factors (biological aging) may predispose women to elevated future CVD risk more so than ANM, a marker of ovarian aging.

Menopause, which marks the end of ovarian reproductive aging is characterized by physiological changes that adversely influence the cardiovascular system. However, studies comparing cardiac structure and function from the premenopausal years to the postmenopausal years among the same individuals are lacking. To date, the few studies investigating the role of menopause on cardiac structure and function have often consisted of small sample and have often been cross-sectional studies 13,14,27-30. These studies report that menopause is associated with adverse myocardial structure, myocardial performance index and myocardial velocities 13,14,27-30. However, menopause is known to be associated with other metabolic factors that influence CVD risk. Despite these studies comparing pre- and postmenopausal women with similar chronological age, the possibility of residual confounding influencing these findings cannot be ruled out. In the current study comparisons of pre- to postmenopausal changes in cardiac structure and function were performed among the same women over 25 years of follow-up. With this reducing the impact of residual confounding on the observed results, we observed higher measures of LV structure in the post-menopausal years compared to the premenopausal years independent of chronological age but not independent of other CVD risk factors such as blood pressure and body mass index.

The relationships of ovarian aging thus cessation of ovarian estrogen production, chronological aging, and CVD risk factors with cardiac remodeling are complex. Studies evaluating the roles of all these interrelated pathways on cardiac structure and function are scarce. The role of exogenous estrogen replacement on the relation of ovarian aging with cardiac remodeling and overt heart failure has been explored in both observational and clinical trials, with results ranging from favorable to no appreciable effect of hormone therapy on cardiac structure and function among postmenopausal women 31-34. Some studies assessing the relation of ovarian aging with cardiac remodeling have found no evidence of confounding by an indication of early age at menopause 34. Accordingly, in the current study, age at natural menopause did not significantly mediate pre- to postmenopausal changes in parameters of cardiac structure and function. This suggests that the observed association of ovarian aging with cardiac remodeling reported in some prior studies may not be solely due to decreased cumulative exposure to endogenous estrogen in women with early onset of menopause 34.

Ovarian aging, and chronological aging are closely linked. However, the independent association of chronological aging on the relation of ovarian aging with cardiac remodeling has not been well studied. In a cross-sectional study of 50 postmenopausal women with age at menopause ranging from 29 to 55 years, Kaur et al 14 reported that those who reached menopause before age 40 years had significant impairment in LV systolic function compared to women with onset of menopause at ages ≥50 years. Another study of women aged 45-84 years enrolled in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis showed that earlier ANM was associated with higher LV mass to volume ratio in a subsample of 272 postmenopausal Chinese-Americans 5. Among 14,550 postmenopausal women aged 50–75 years in the UK Biobank, earlier age at menopause was observed to be associated with accelerated LV remodeling as indicated by smaller left ventricular end-diastolic volume and smaller stroke volume 34. All these reports from cross-sectional analyses did not distinguish between the type of menopause (i.e., natural or surgical) that is known to have differential relationships on cardiac structure and function 35,36. Therefore, it is unknown how much of these reported associations are due to the natural process of ovarian aging or CVD risk factors.

Different lines of evidence indicate that premenopausal CVD risk factors such as obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia and smoking are inversely related to age at natural menopause (ovarian aging) 37-39 as well as positively related to subclinical and overt CVD 40,41. Accordingly, adverse CVD risk profiles in premenopausal women resulting in early onset of CVD events are reported to be associated with the early onset of natural menopause 42. The abrupt ending of ovarian function among women with bilateral oophorectomy occurring before the average age at natural menopause is known to be related to CVD risk factor profiles long before such women undergo surgery 38. Accordingly, these adverse CVD risk factors have been shown to be associated with indications for surgical menopause 37,43. Thus, adverse CVD risk factors may be drivers of accelerated ovarian aging.

In support of this, ours and other longitudinal studies 39 previously reported that premenopausal antecedent CVD risk factor levels are directly related to postmenopausal levels for all type of menopause 38, and accounting for premenopausal CVD risk factor levels attenuates the significant differences in postmenopausal CVD risk factor levels and subclinical cardiovascular disease between women with natural and surgical menopause (33, 34). In the current study, ANM was inversely associated with changes in LV structure parameters independent of chronological age. However, after adjustment for antecedent CVD risk factors, the relation of ANM with changes in cardiac structure parameters was no longer statistically significant. Additional control of hormone therapy use did not change these findings. Taken together, these findings suggest that other processes such as antecedent CVD risk factors that contribute to ovarian aging may play a greater role in cardiac structure and function among postmenopausal women than ovarian aging. Therefore, the underlying pathology for the higher incidence of CVD events among postmenopausal women reported in previous studies 44 may have existed long before the onset of menopause.

A recent report from the CARDIA study observed that compared to premenopausal women, postmenopausal women had higher LV mass, LV mass index, left atrial volume and left atrial volume index after adjusting for confounders 15. In the current study, an inverse association was observed between ANM and LAVI, but was not present when women with onset of natural menopause at age 50 or less were compared to women with onset of menopause after 50 years of age. Differences in the results between the current study and the study by Ying et al 15 is primarily due to differences in the exposure or predictor of the two Studies. Ying et al 15 evaluated the relation of menopausal status with LV structure and function while the current study evaluated the association of ANM with LV structure and function. Additionally, the sample in the study by Ying et al 15 have different characteristics to that of the current study. Unlike the current study that used information on only women who naturally transitioned from premenopause to postmenopause, the study by Ying et al15, included women who did and did not transition to menopause, increasing the possibility of residual confounding potentially influencing the observed results. Additionally, the study by Ying et al15 included women who had natural or surgical menopause. As shown in a previous CARDIA study 35, women who have surgical menopause tend to have adverse parameters of LV structure and function compared to women who reached natural menopause.

This study has notable strengths that include the use of a large population-based biracial cohort with repeated echocardiography measurements, and the extensive assessment of CVD risk factors long before the onset of menopause. Limitations for the study are as follows. First, ANM was self-reported and may be subject to recall error. Moderate reliability in the recall of ANM after several years have been reported 45. Second, serial yearly measurements of CVD risk factors and changes in endogenous sex hormones during the menopause transition period, often considered to begin about 2 years before the final menstrual period, are not available. Third, echocardiographic measurements were undertaken about 25 years apart using different equipment, sonographers and reading centers, which may affect comparability of the parameters of LV structure and function. However, the CARDIA quality control and reliability studies report good agreement between repeated echocardiographic measurements 21-23. Fourth, results of the present study may or may not be generalizable to women of other races and ethnicities.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, this population-based longitudinal study that aimed to disentangle the associations of ovarian aging, chronological aging and biological aging with changes in cardiac structure and function over a long period of follow-up suggests that premenopausal CVD risk factors (biological aging) may predispose women to elevated future CVD risk more so than ANM, a marker of ovarian aging independent of chronological aging. These findings have important clinical and public health significance. With some lifestyle prevention trials showing promise for long-term interventions in reducing CVD risk factor levels among women transitioning to menopause 46,47, implementation of lifestyle or medical therapy should begin early in women’s lives to reduce their future risk of subclinical and overt CVD events during the postmenopausal period.

Supplementary Material

Sources of funding:

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) is conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham (HHSN268201800005I & HHSN268201800007I), Northwestern University (HHSN268201800003I), University of Minnesota (HHSN268201800006I), and Kaiser Foundation Research Institute (HHSN268201800004I). This manuscript has been reviewed by CARDIA for scientific content.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures/conflicts of interest: Cora E Lewis receives funding from Rush University Medical Center. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Some of the results for this manuscript were presented as a poster at the American Heart Association’s Epidemiology and Prevention/ Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health Scientific Session, Houston, TX (March 5, 2019) and the abstract was published in Circulation, 139, Suppl_1, p411.

REFERENCES

- 1.El Khoudary SR, Aggarwal B, Beckie TM, et al. Menopause Transition and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: Implications for Timing of Early Prevention: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142(25):e506–e532 doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wellons M, Ouyang P, Schreiner PJ, Herrington DM, Vaidya D. Early menopause predicts future coronary heart disease and stroke: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Menopause. 2012;19(10):1081–1087 doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182517bd0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lisabeth LD, Beiser AS, Brown DL, Murabito JM, Kelly-Hayes M, Wolf PA. Age at natural menopause and risk of ischemic stroke: the Framingham heart study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2009;40(4):1044–1049 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.542993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appiah D, Schreiner PJ, Demerath EW, Loehr LR, Chang PP, Folsom AR. Association of Age at Menopause With Incident Heart Failure: A Prospective Cohort Study and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2016;5(8) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebong IA, Watson KE, Goff DC Jr., et al. Age at menopause and incident heart failure: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Menopause. 2014;21(6):585–591 doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahman I, Akesson A, Wolk A. Relationship between age at natural menopause and risk of heart failure. Menopause. 2015;22(1):12–16 doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bui AL, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC. Epidemiology and risk profile of heart failure. Nature reviews Cardiology. 2011;8(1):30–41 doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Appiah D, Winters SJ. Hormone Therapy for Preventing Heart Failure in Postmenopausal Women. J Card Fail. 2020;26(1):13–14 doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2019.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kane GC, Karon BL, Mahoney DW, et al. Progression of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and risk of heart failure. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;306(8):856–863 doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuznetsova T, Herbots L, Jin Y, Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Staessen JA. Systolic and diastolic left ventricular dysfunction: from risk factors to overt heart failure. Expert review of cardiovascular therapy. 2010;8(2):251–258 doi: 10.1586/erc.10.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bluemke DA, Kronmal RA, Lima JA, et al. The relationship of left ventricular mass and geometry to incident cardiovascular events: the MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;52(25):2148–2155 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duzenli MA, Ozdemir K, Sokmen A, et al. Effects of menopause on the myocardial velocities and myocardial performance index. Circulation journal : official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society. 2007;71(11):1728–1733 doi: 10.1253/circj.71.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duzenli MA, Ozdemir K, Sokmen A, et al. The effects of hormone replacement therapy on myocardial performance in early postmenopausal women. Climacteric : the journal of the International Menopause Society. 2010;13(2):157–170 doi: 10.3109/13697130902929567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaur M, Singh H, Ahuja GK. Cardiac performance in relation to age of onset of menopause. Journal of the Indian Medical Association. 2011;109(4):234–237. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22187793. Published 2011/December/23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ying W, Post WS, Michos ED, et al. Associations between menopause, cardiac remodeling, and diastolic function: the CARDIA study. Menopause. 2021;28(10):1166–1175 doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, et al. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1988;41(11):1105–1116 doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Research on the menopause in the 1990s. Report of a WHO Scientific Group. World Health Organization technical report series. 1996;866:1–107. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8942292. Published 1996/January/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagenknecht LE, Cutter GR, Haley NJ, et al. Racial differences in serum cotinine levels among smokers in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults study. American journal of public health. 1990;80(9):1053–1056 doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.9.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobs DR Jr., Hahn LP, Haskell WL, Pirie P, Sidney S. Validity and Reliability of Short Physical Activity History: Cardia and the Minnesota Heart Health Program. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 1989;9(11):448–459. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29657358. Published 1989/November/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28(1):1–39 e14 doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armstrong AC, Ricketts EP, Cox C, et al. Quality Control and Reproducibility in M-Mode, Two-Dimensional, and Speckle Tracking Echocardiography Acquisition and Analysis: The CARDIA Study, Year 25 Examination Experience. Echocardiography. 2015;32(8):1233–1240 doi: 10.1111/echo.12832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vasconcellos HD, Moreira HT, Ciuffo L, et al. Cumulative blood pressure from early adulthood to middle age is associated with left atrial remodelling and subclinical dysfunction assessed by three-dimensional echocardiography: a prospective post hoc analysis from the coronary artery risk development in young adults study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19(9):977–984 doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jey086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gidding SS, Liu K, Colangelo LA, et al. Longitudinal determinants of left ventricular mass and geometry: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Circulation Cardiovascular imaging. 2013;6(5):769–775 doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.000450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Lutas EM, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: comparison to necropsy findings. The American journal of cardiology. 1986;57(6):450–458 doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90771-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desai CS, Colangelo LA, Liu K, et al. Prevalence, prospective risk markers, and prognosis associated with the presence of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in young adults: the coronary artery risk development in young adults study. American journal of epidemiology. 2013;177(1):20–32 doi: 10.1093/aje/kws224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bindu Garg GKK, Harsha Vardhan, Nirmal Yadav. Cardiovascular disease risk in pre- and postmenopausal women. Pakistan Journal of Physiology. 2017;13(2):11–14 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nio AQX, Rogers S, Mynors-Wallis R, et al. The Menopause Alters Aerobic Adaptations to High-Intensity Interval Training. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2020;52(10):2096–2106 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schillaci G, Verdecchia P, Borgioni C, Ciucci A, Porcellati C. Early Cardiac Changes After Menopause. Hypertension. 1998;32(4):764–769 doi:doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.32.4.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hinderliter AL, Sherwood A, Blumenthal JA, et al. Changes in hemodynamics and left ventricular structure after menopause. The American journal of cardiology. 2002;89(7):830–833 doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02193-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schierbeck LL, Rejnmark L, Tofteng CL, et al. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on cardiovascular events in recently postmenopausal women: randomised trial. BMJ. 2012;345:e6409 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanghvi MM, Aung N, Cooper JA, et al. The impact of menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) on cardiac structure and function: Insights from the UK Biobank imaging enhancement study. PloS one. 2018;13(3):e0194015 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu L, Klein L, Eaton C, et al. Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Risks of First Hospitalized Heart Failure and its Subtypes During the Intervention and Extended Postintervention Follow-up of the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Trials. J Card Fail. 2020;26(1):2–12 doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2019.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Honigberg MC, Pirruccello JP, Aragam K, et al. Menopausal age and left ventricular remodeling by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging among 14,550 women. American heart journal. 2020;229:138–143 doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2020.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Appiah D, Schreiner PJ, Nwabuo CC, Wellons MF, Lewis CE, Lima JA. The association of surgical versus natural menopause with future left ventricular structure and function: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Menopause. 2017;24(11):1269–1276 doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaur M, Ahuja GK, Singh H, Walia L, Avasthi KK. Evaluation of left ventricular performance in menopausal women. Indian journal of physiology and pharmacology. 2010;54(1):80–84. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21046925. Published 2010/November/05. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kok HS, van Asselt KM, van der Schouw YT, et al. Heart disease risk determines menopausal age rather than the reverse. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;47(10):1976–1983 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Appiah D, Schreiner PJ, Bower JK, Sternfeld B, Lewis CE, Wellons MF. Is Surgical Menopause Associated With Future Levels of Cardiovascular Risk Factor Independent of Antecedent Levels? The CARDIA Study. American journal of epidemiology. 2015;182(12):991–999 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matthews KA, Gibson CJ, El Khoudary SR, Thurston RC. Changes in cardiovascular risk factors by hysterectomy status with and without oophorectomy: Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;62(3):191–200 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Kat AC, Dam V, Onland-Moret NC, Eijkemans MJ, Broekmans FJ, van der Schouw YT. Unraveling the associations of age and menopause with cardiovascular risk factors in a large population-based study. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):2 doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0762-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sowers M, Zheng H, Tomey K, et al. Changes in body composition in women over six years at midlife: ovarian and chronological aging. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2007;92(3):895–901 doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu D, Chung HF, Pandeya N, et al. Premenopausal cardiovascular disease and age at natural menopause: a pooled analysis of over 170,000 women. European journal of epidemiology. 2019;34(3):235–246 doi: 10.1007/s10654-019-00490-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He Y, Zeng Q, Li X, Liu B, Wang P. The association between subclinical atherosclerosis and uterine fibroids. PloS one. 2013;8(2):e57089 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Atsma F, Bartelink ML, Grobbee DE, van der Schouw YT. Postmenopausal status and early menopause as independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Menopause. 2006;13(2):265–279 doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000218683.97338.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodstrom K, Bengtsson C, Lissner L, Bjorkelund C. Reproducibility of self-reported menopause age at the 24-year follow-up of a population study of women in Goteborg, Sweden. Menopause. 2005;12(3):275–280 doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000135247.11972.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simkin-Silverman LR, Wing RR, Boraz MA, Kuller LH. Lifestyle intervention can prevent weight gain during menopause: results from a 5-year randomized clinical trial. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(3):212–220 doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2603_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuller LH, Simkin-Silverman LR, Wing RR, Meilahn EN, Ives DG. Women's Healthy Lifestyle Project: A randomized clinical trial: results at 54 months. Circulation. 2001;103(1):32–37 doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.