Abstract

Objectives: To systematically review literature and identify mother-to-child transmission rates of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus among pregnant women with single, dual, or triplex infections of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus in Nigeria. PRISMA guidelines were employed. Searches were on 19 February 2021 in PubMed, Google Scholar and CINAHL on studies published from 1 February 2001 to 31 January 2021 using keywords: “MTCT,” “dual infection,” “triplex infection,” “HIV,” “HBV,” and “HCV.” Studies that reported mother-to-child transmission rate of at least any of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus among pregnant women and their infant pairs with single, dual, or triplex infections of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus in Nigeria irrespective of publication status or language were eligible. Data were extracted independently by two authors with disagreements resolved by a third author. Meta-analysis was performed using the random effects model of DerSimonian and Laird, to produce summary mother-to-child transmission rates in terms of percentage with 95% confidence interval. Protocol was prospectively registered in PROSPERO: CRD42020202070. The search identified 849 reports. After screening titles and abstracts, 25 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility and 18 were included for meta-analysis. We identified one ongoing study. Pooled mother-to-child transmission rates were 2.74% (95% confidence interval: 2.48%–2.99%; 5863 participants; 15 studies) and 55.49% (95% confidence interval: 35.93%–75.04%; 433 participants; three studies), among mother–infant pairs with mono-infection of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B virus, respectively, according to meta-analysis. Overall, the studies showed a moderate risk of bias. The pooled rate of mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus was 2.74% and hepatitis B virus was 55.49% among mother–infant pairs with mono-infection of HIV and hepatitis B virus, respectively. No data exists on rates of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus on mono-infection or mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus among mother–infant pairs with dual or triplex infection of HIV, hepatitis B virus and HCV in Nigeria.

Keywords: Hepatitis B, hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus, infectious diseases, mother-to-child transmission, Nigeria

Introduction

Every child deserves to start life free from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and other infectious diseases transmissible from mother-to-child during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding. 1 Single, dual, or triplex infections of these viruses are common in pregnant woman due to shared means of transmission including blood transfusion, sharing of sharp objects, and unsafe sex, among others. 2 Maternal dual or triplex co-infection with these potentially deadly viruses not only worsens maternal outcomes but is also associated with increased risk of mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of each infection.2–5 In a Nigerian pediatric HIV program, 7.7% and 5.2% of the HIV-infected children were co-infected with HBV and HCV, respectively. 6

Fortunately, the MTCT of these infections of public health importance can be prevented or eliminated through simple interventions involved in prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) programs. 7 However, these programs are poorly coordinated. The result is that large numbers of children continue to be born with these life-threatening infections every day. 7

The global target of eliminating new HIV infections among children by reducing the number of children newly infected to less than 20,000 per annum by year 2020 fell way below the target. 1 About 150,000 children in 2019 became newly infected with HIV and more than two-third of these estimated infections occurred in 21 focus African countries, including Nigeria. 1 Among these Focus Countries, Nigeria had the second highest MTCT rate (22%) and the largest MTCT burden. More than 90% of these new pediatric infections occur during pregnancy, childbirth, and the breastfeeding. Without any intervention, about 15%–30% of infants born to HIV-positive mothers will become HIV-infected in utero or during delivery while another 5%–15% will become infected through breastfeeding. 1

However, MTCT of HBV during pregnancy or delivery accounts for more than one-third of chronic HBV infections globally. 7 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 8 infection in infancy and early childhood leads to chronic hepatitis in about 95% of cases. Without post exposure immune-prophylaxis, approximately 40% of infants born to HBV-infected mothers in the United States will develop chronic HBV infection, approximately one-fourth of whom will eventually die from chronic liver disease. 8 In Nigeria, MTCT rates of HBV vary from 8.3% to 12.8%. 6 There are limited reports on MTCT rates of HCV in Nigeria as it is often not routinely screened. However, the burden of HIV/HCV MTCT may also be significant given the reported rate of 5.2% of pediatric HIV/HCV co-infections. 5

The similarity of the PMTCT interventions for HIV, HBV, and HCV makes it feasible to use an integrated approach to eliminate MTCT of these diseases. 9 The 2016 World Health Assembly endorsed three interlinked global health sector strategies on HIV, viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infections, which set ambitious targets for elimination of MTCT of HIV, hepatitis B, and syphilis by 2030. 9 However, these integrated services are not fully implemented in Nigeria. Moreso, coordinated HBV PMTCT services are not in existent in Nigeria despite the huge HBV burden in the country. This may be due to lack of evidence-based research on MTCT of these viruses. The WHO has recommended that there is a need to improve country level surveillance of MTCT of dual or triplex infections across different population groups in all regions.3–5

There is dearth of scholarly works examining the MTCT rates of single, dual, or triplex infections of HIV, HBV, and HCV in Nigerian population despite her high burden of these diseases. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to document the MTCT rates of HIV, HBV, and HCV among pregnant women with single, dual, or triplex infections of HIV, HBV, and HCV in Nigeria. Results will guide stakeholders and policy makers in adopting strategies that will ensure the achievement of elimination of MTCT targets. The systematic review question is: what is the best available evidence on the MTCT rates of HIV, HBV, HCV, or their co-infections among pregnant women with single, dual, or triplex infections of HIV, HBV, and HCV in Nigeria?

Methods

Overview

We did a systematic review of studies on the mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) rates of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) among pregnant women with single, dual, or triplex infections of HIV, HBV, and HCV in Nigeria. The review was registered prospectively with PROSPERO (CRD42020202070) and reported according to PRISMA 2020 guidelines. 10

Search strategy

Extensive online search was conducted using PubMed, Google Scholar, and CINAHL. The PubMed search strategy is presented in Figure 1. Medical subject headings (MeSH) and free text words were combined using the Boolean operators “OR” and “AND.” The reference lists of included studies were screened to identify additional publications. The Google Scholar search string is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PubMed and Google Scholar search strategies.

In this systematic review, we searched for studies that reported the MTCT of HIV, HBV, and HCV. We limited the search to studies conducted within the last 20 years to obtain recent data on the rate of MTCT since the Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health commenced PMTCT of HIV program in 2002. 11 The searches were done with no language restrictions on 19 February 2021, in PubMed, Google Scholar, and CINAHL. Search terms included were “HIV OR Human immunodeficiency virus,” “OR Hepatitis-C OR HCV,” “OR Hepatitis-B OR HBV,” AND “prevalen* OR inciden* OR seroprevalen* OR screening OR surveillance OR population* OR survey* OR epidem* OR data collection OR population sample* OR community survey* OR pregnant women* OR mother-to-child transmission* OR cohort OR cross-sectional OR longitude* OR follow-up.” Searches were tailored to each database. Reference lists were screened for additional sources. The search focused on published medical literature as well as gray literature.

Eligibility criteria

Studies that reported or described MTCT rate of at least any of HIV, HBV, and HCV among pregnant women and their infant pairs with single, dual, or triplex infections of HIV, HBV, and HCV in Nigeria irrespective of publication status or language were eligible. Studies were excluded if they were abstracts only or published prior to February 2001. Studies published between February 2001 and January 2021 were considered for inclusion. The titles and abstracts were used to screen the articles. However, where the suitability was in doubt, the full texts were reviewed. Online search included primary studies which reported maternal HIV single or co-infection with HBV and or HCV, MTCT rates of such maternal infections and determinants of MTCT in Nigeria.

Study population

The study population was defined as pregnant women and their infant pairs with single, dual, or triplex infections of HIV, HBV, and HCV in Nigeria.

Study area

Only studies conducted in Nigeria were eligible for inclusion.

Study design

Studies selected were prospective, retrospective, cross-sectional, or case control in nature. Relevant clinical trials were also eligible for inclusion.

Language

Studies reported were not restricted in English language.

Publication condition

Studies which meet the eligibility criteria were included regardless of their publication status (published, unpublished, or gray literature).

Exclusion criteria

We excluded editorials or reviews containing no primary data, no samples of HIV, HBV, HCV or HIV-HBV or HBV-HCV or HIV–HCV-infected individuals, or samples relying on self-reported infection status. Conference presentations, case reports, and review articles were also excluded from the study. Where the full text was not available, the articles were excluded from the study.

Data extraction

Data extraction was done by two independent reviewers (C.O. and R.E., with discrepancies resolved by a third reviewer (I.M.)) using a pretested data extraction form which was prepared in Microsoft Excel. The reviewers independently extracted relevant information, including first author, year of publication and period of participants’ recruitment, study location, study design, eligibility criteria, sample size, type of infection, and number of participants with HIV I and II, HBsAg, HBeAg, HCVAb, and HCV detectable viral load, and MTCT rate. Infection was defined as the presence of HIV I and II, HBsAg or HCVAb for HIV, HBV, and HCV, respectively.

Main outcomes

The main outcome measure was MTCT rates of single, dual, and triplex infections of HIV, HBV, and HCV measured using antibody test and/or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) at birth and/or at 6 weeks to 18 months using antibody test and PCR. We defined MTCT rate as the proportion of tested HIV or HBV or HCV-exposed infants who tested HIV or HBV or HCV positive, respectively.

Analysis of subgroups or subsets

We performed subgroup analysis involving studies that published the population of northern region versus southern region of Nigeria as well as publication from 2001 to 2015 versus publication from 2016 to 2021. However, we planned to perform the subgroup analyses in the following areas: asymptomatic versus symptomatic individuals; and mothers with dual infection versus mothers with triplex infection mothers.

Selection of studies

We downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching to the reference management software Endnote 6.0. We removed duplicates and two review authors (C.O., I.O.) independently examined the remaining references. We excluded studies that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria and obtained copies of the full text of potentially relevant studies. Two review authors (C.O., I.O.) independently assessed the eligibility of the retrieved papers and resolved any disagreements by discussion or recourse to third review author (G.E. or I.M.). We documented reasons for exclusions.

Methodological quality and risk of bias assessment

The quality of the included studies was assessed using a valid and reliable tool designed by Munn et al., 12 which has been used to measure rates in observational studies in various systematic reviews globally. The instrument consisted of nine questions to assess the quality of methodology, including sample frame, sample population representativeness, sample size, sampling method, reporting subjects’ characteristics, data analysis coverage, method of measurement/diagnosis, appropriateness of statistical analysis, and response rate. For each question, an answer of “yes” was given a score of 1, while an answer of “no,” or “unclear” was given a score of 0. As a result, the score for each study ranged from 0 to 9. 12 Studies were rated as low risk, moderate risk or high risk if the overall score ranged from 7–9, 4–6, and 0–3, respectively. The details are shown in Appendices S1A, S1B, and S1C. Quality assessment was performed independently by two researchers (G.E. and I.O.). The opinion of a third researcher (C.O.) was used in the case of disagreement. We assessed the risk of bias in the studies using the Risk of Bias tool designed by Munn et al. 12

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using RevMan 5.4.1 (The Nordic Cochrane Center, Copenhagen, Denmark). We pooled data about the mother–infant pairs population of MTCT rates of HIV and HBV infection and percentage (with 95% confidence interval (CI)) was used as the effect size, and then the inverse variance method (Generic Inverse Variance) was selected to calculate the pooled effect. In this statistical procedure, the rates difference (RD) and its standard error are noted to be equivalent to the effect of a single rate and the standard error. 13 Meta-analysis was performed using the random effects model of DerSimonian and Laird.

Cochran’s (Q) statistic test and I2 statistic were used to assess for heterogeneity between studies. The p-value less than 0.1 was considered statistically significant for the Q-statistics test and an I2 value above 50% was considered to represent significant heterogeneity. For all other tests, except heterogeneity testing, p-value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Role of the funding source

This work was funded by TETFund National Research Fund 2019 (Grant number TETFund/DR&D/CE/NRF/STI/33). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the TETFund. The funders had no role in the design of the study or writing of the article. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search strategy identified 33 references in PubMed, 800 in Google Scholar, 10 in CINAHL, and 6 references following additional records identified through other sources (see Figure 2). When the search results were merged into Endnote and duplicates were removed, there were 486 unique records. Two review authors (C.O., I.O.) independently read the titles and abstracts and excluded 567 studies because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Two review authors (G.E. and I.M.) independently searched the gray literature (National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria website, Federal Ministry of Health of Nigeria website and The United States Agency for International Development website); these searches also did not identify any relevant study. The full texts of the remaining 25 articles were screened, and 18 studies (15 studies for HIV; 3 studies for HBV) that analyzed only the MTCT on mono-infection population were identified. We identified one relevant ongoing study by Eleje et al. 14 The ongoing study is a multicenter prospective cohort study aimed at determining the seroprevalence, seroconversion rate, the rate and risk factors for MTCT of the dual, and triplex infection in pregnancy using PCR at birth and 6 weeks post-delivery in Nigeria (see Table 1).

Figure 2.

PRISMA flowchart.

Table 1.

Characteristics of ongoing study.

| Variable | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Title | Prevalence, seroconversion, and mother-to-child transmission of dual and triplex infections of HIV, HBV, and HCV among pregnant women in Nigeria: study protocol. |

| Methods | A multicenter prospective cohort study will be conducted in six tertiary health facilities randomly selected from the six geopolitical zones of Nigeria. |

| Participants | All eligible pregnant women are to be tested at enrollment after informed consent for HIV, Hepatitis B and C virus infections. While those positive for at least two of the infections in any combination will be enrolled into the study and followed up to 6 weeks post-delivery, those negative for the three infections or positive for only one of the infections at enrolment will be retested at delivery using a rapid diagnostic test. All exposed newborns will be tested for HIV, HBV, or HCV infection at birth and 6 weeks using PCR technique. |

| Outcomes | 1. Seroprevalence of the dual and triplex infection among pregnant women. 2. Hepatic enzyme status and patterns among pregnant women with dual/triplex infections. 3. New infection rate (seroconversion) and risk factors for seroconversion of dual and triplex infections. 4. Rate of mother-to-child transmission of dual/triplex infections using polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) at 6 weeks post-delivery. |

| Starting date | 1 July 2020 |

| Contact information | Dr George Eleje, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria. Email: georgel21@yahoo.com |

| Notes | The protocol was published by Eleje et al. It is also available at this link: https://rdcu.be/b7Js0 |

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

Apart from the ongoing study, we excluded six articles that we retrieved; as they did not meet the inclusion criteria6,15–19 (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of excluded studies.

| Study ID | Reasons for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Sadoh et al. 5 | The study population was not pregnant women and their infant pairs with dual and triplex infections of HIV, HBV, and HCV in Nigeria but consisted of consecutive children aged 2 months to 17 years who were confirmed to be HIV infected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in those older than 18 months or by DNA polymerase chain reaction if younger than 18 months. |

| Nwolisa et al. 15 | The study population was not pregnant women and their infant pairs with dual and triplex infections of HIV, HBV, and HCV in Nigeria but consisted of HIV infected children ⩾18 months of age attending the Pediatric HIV Care and treatment unit of the clinic. |

| Offor et al. 16 | The study population was not pregnant women and their infant pairs with dual and triplex infections of HIV, Hepatitis B and C viruses in Nigeria but consisted of 492 systematic blood samples (made up of 246 maternal and cord blood pairs) collected during delivery at the labor ward and theater of the University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Nigeria and was published prior to 2001. |

| Lawal et al. 17 | The study population was not pregnant women and their infant pairs with dual and triplex infections of HIV, Hepatitis B and C viruses in Nigeria but consisted of HIV infected children aged 2 months to 13 years in Lagos, Nigeria. |

| Okechukwu et al. 18 | The study population was not pregnant women and their infant pairs with dual and triplex infections of HIV, HBV, and HCV in Nigeria but consisted of HIV infected children and adolescents aged 2 months to 18 years on antiretroviral therapy at the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. |

| Audu et al. 19 | The study population was not pregnant women and their infant pairs with dual and triplex infections of HIV, Hepatitis B and C viruses in Nigeria but consisted of infants aged less than 18 months and were either (1) known HIV-exposed infants referred from the PMTCT program or other settings in the facility or (2) sick infants whose HIV status was not necessarily known but who presented with signs and/or symptoms suggestive of HIV. |

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; DNA: deoxyribonucleic acid; PMTCT: prevention of mother-to-child transmission.

Table 3 presents the main characteristics of the 18 included studies.20–37 Majority of the studies were “retrospective cohort studies” (retrospective chart reviews) 8/18 (44.5%)20,21,23,25,27,32–34 or prospective cohort studies 6/18 (33.3%),24,26,28,31,35,37 while only 4/18 (22.2%) were cross-sectional studies.22,29,30,36 Majority of the studies included in our meta-analysis (17/18; 94.4%) were published from 2011 to 202120–34,36,37 and one study (1/18; 5.6%) was conducted between 2001 and 2010. 35

Table 3.

Characteristics of included mono-infection population studies.

| Study ID | Study location (Region) | Study design | Sample size | Type of infection | MTCT rate at birth | MTCT rate at 6 weeks to 18 months | Quality assessment score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eleje et al. 20 | Nnewi (South) | Retrospective cohort | 22 | HIV | – | 0.0% | 5 |

| Okafor et al. 21 | Enugu (South) | Retrospective cohort | 182 | HIV | 0.0% | 6 | |

| Ben and Yusuf 22 | Sokoto (North) | Cross-sectional | 88 | HIV | – | 0.0% | 5 |

| Sagay et al. 23 | Jos (North) | Retrospective cohort | 856 | HIV | – | 0.4% | 7 |

| Onubogu et al. 24 | Nnewi (South) | Prospective cohort | 142 | HIV | – | 1.0% | 5 |

| Chukwuemeka et al. 25 | Abuja (North) | Retrospective cohort | 397 | HIV | – | 1.3% | 6 |

| Kalu et al. 26 | Nnewi (South) | Prospective cohort | 58 | HIV | – | 1.7% | 5 |

| Isah et al. 27 | Enugu (South) | Retrospective cohort | 367 | HIV | – | 2.18% | 6 |

| Ikechebelu et al. 28 | Nnewi (South) | Prospective cohort | 726 | HIV | – | 2.8% | 7 |

| Oluwayemi et al. 29 | Ekiti (South) | Cross-sectional | 88 | HIV | – | 3.4% | 5 |

| Markson and Umoh 30 | Oron, Akwa Ibom (South) | Cross-sectional | 398 | HIV | – | 4.0% | 6 |

| Afolabi et al. 31 | Ibadan (South) | Prospective cohort | 44 | HIV | – | 4.5% | 5 |

| Anoje et al. 32 | Cross River and Akwa Ibom (South) | Retrospective cohort | 434 | HIV | – | 4.8% | 6 |

| Itiola et al. 33 | Adamawa (North) | Retrospective cohort | 1651 | HIV | – | 5.4% | 7 |

| Afe et al. 34 | Lagos (South) | Retrospective case-control | 410 | HIV | – | 9.6% | 6 |

| Onakewhor et al. 35 | Benin City (South) | Prospective cohort | 320 | HBV | 42.86% | – | 5 |

| Eke et al. 36 | Nnewi (South) | Cross-sectional | 40 | HBV | 51.6% | – | 5 |

| Olaleye et al. 37 | Ife (South) | Prospective cohort | 73 | HBV | 72.0% | – | 7 |

MTCT: mother-to-child transmission; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HBV: hepatitis B virus.

Included studies

Eighteen studies were included in a meta-analysis on rates of MTCT of HIV or HBV mono-infections,20–37 as this forms the only evidence base in these viral infections of pregnancy in Nigeria (see Table 3).

Excluded studies

We excluded seven references after obtaining the full-text paper for the following reasons: One reference was an ongoing study 14 and the other six references reported on studies whose study population did not include mother–infant pairs with single, dual or triplex infections of HIV, HBV, and HCV6,15–19 and one Offor et al. 16 was published prior to February 2001, a time prior to the routine use of antiretroviral therapy in Nigerian hospitals 12 (see Table 2).

Risk of bias in included studies

Only studies that reported on mono-infections of HIV and HBV were included and were subjected to risk of bias assessment.

Data collection and analysis

MTCT rates of HIV-HBV co-infections

No data were available for analysis.

MTCT rates of HIV-HCV co-infections

No data were available for analysis.

MTCT rates of HBV-HCV co-infections

No data were available for analysis.

MTCT rates of HIV-HBV-HCV triplex infections

No data were available for analysis.

Rates of MTCT of HIV mono-infection

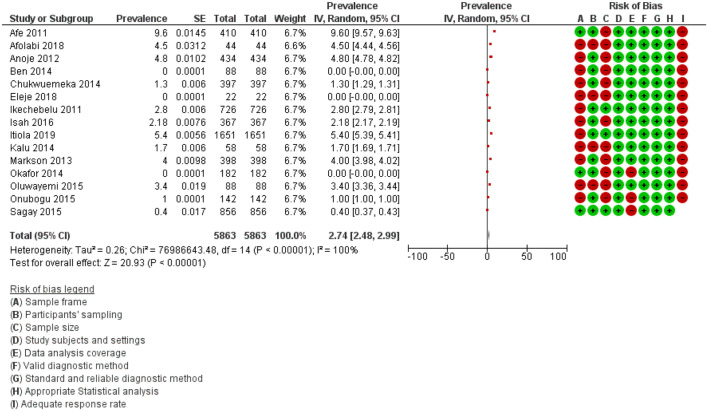

We combined data in meta-analysis for rates of MTCT of HIV. Figure 3 shows the meta-analysis revealing the pooled MTCT rate of HIV mono-infection in the included studies.

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis showing the pooled MTCT rate of HIV mono-infection in the included studies.

Fifteen studies involving 5863 participants reported on the MTCT rate of HIV in mother–infant pair with HIV mono-infection when all the pregnant women living with HIV received triple antiretroviral therapy, as treatment or prophylaxis, regardless of breastfeeding habit.20–34 The MTCT rates for HIV were reported to be 0.0% by Eleje et al., 20 Okafor et al., 21 and Ben and Yusuf, 22 0.4% by Sagay et al., 23 1.0% by Onubogu et al., 24 1.3% by Chukwuemeka et al., 25 1.7% by Kalu et al., 26 2.18% by Isah et al., 27 2.8% by Ikechebelu et al., 28 3.4% by Oluwayemi, 29 4.0% by Markson and Umoh, 30 4.5% by Afolabi et al., 31 4.8% by Anoje et al., 32 5.4% by Itiola et al., 33 and 9.6% by Afe et al. 34 at 6 weeks to 18 months following PCR analysis. The results of our meta-analysis revealed that the pooled MTCT rates for HIV mono-infections as seen in the 15 included studies that reported on HIV mono-infections was 2.74% (95% CI: 2.48%–2.99%; 5863 participants; 15 studies; I2 = 100%; p-value < 0.001) (Figure 3).

Rates of MTCT of HBV mono-infection

We combined data in meta-analysis for rates of MTCT of HBV because the studies included were on mono-infection population. Figure 4 shows the meta-analysis showing the pooled MTCT rate of HBV mono-infection in the included studies.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis showing the pooled MTCT rate of HBV mono-infection in the included studies.

Three studies involving 433 participants reported on the MTCT rate of HBV in mother–infant pair with HBV mono-infection confirmed using PCR technique.35–37 The MTCT rate for HBV were reported to be 42.86% by Onakewhor et al., 35 51.6% by Eke et al., 36 and 72.0% by Olaleye et al. 37 among newborns at birth. The results of our meta-analysis revealed that the overall MTCT rates for HBV mono-infections as seen in the three included studies that reported on HBV mono-infections was 55.49% (95% CI: 35.93%–75.04%; 433 participants; three studies, I2 = 100%; p-value < 0.001) (Figure 4).

Rates of MTCT of HCV mono-infection

No data were available for analysis.

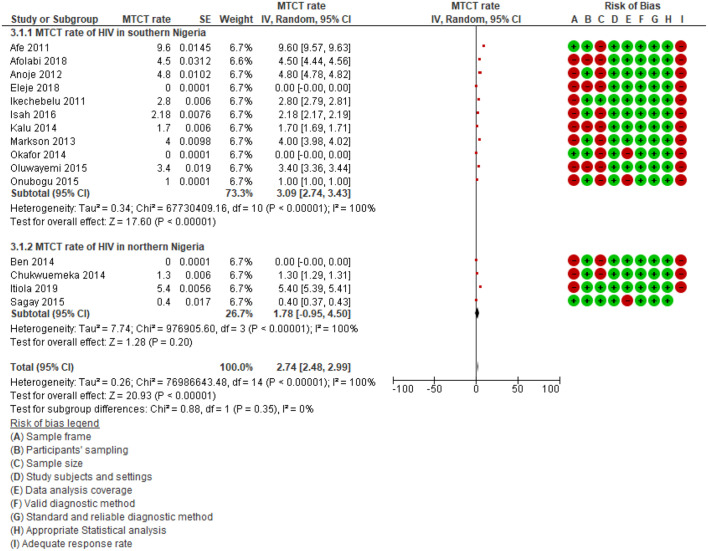

Subgroup analyses

We performed subgroup analyses of MTCT rates for HIV in the southern region versus northern regions of Nigeria. The subgroup analyses revealed that the MTCT rate of HIV in the southern region of Nigeria (3.09%; 95% CI: 2.74%–3.43%, p < 0.001; I2 = 100.0%; 11 studies) was higher than in Northern Nigeria (1.78%; 95% CI: −0.95% to 4.50%, p < 0.001; I2 = 100.0%; four studies) (Figure 5). However, tests for subgroup differences showed no significant difference (p = 0.35, I2 = 0%).

Figure 5.

Subgroup analysis according to regions in Nigeria.

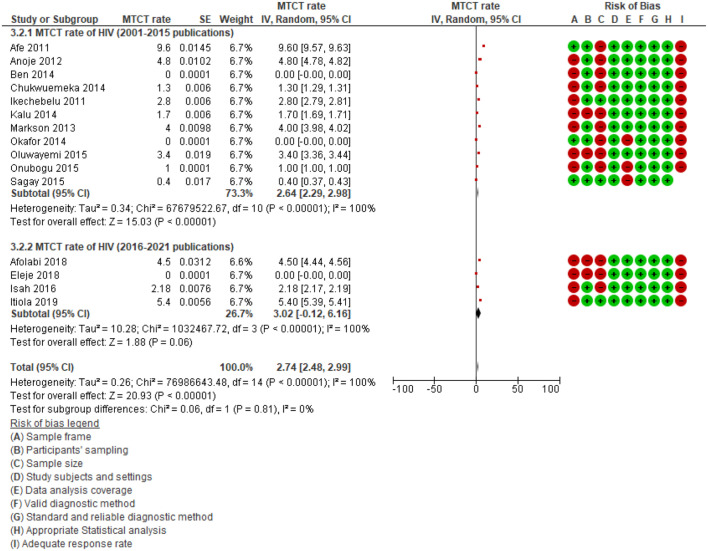

In addition, a subgroup analysis of studies published between 2001 and 2015 and those published between 2016 and 2021 revealed that the MTCT rate of HIV among studies published between 2001 and 2015 (2.64%; 95% CI: 2.29%–2.98%, p < 0.001; I2 = 100.0%; 11 studies) was lower than those published between 2016 and 2021 (3.02%; 95% CI: −0.12% to 6.16%, p < 0.001; I2 = 100.0%; four studies) (Figure 6). Tests for subgroup differences showed no significant difference (p = 0.81, I2 = 0%). The subgroup analysis did not reduce the heterogeneity, indicating that the year of publication is not the source of heterogeneity (I2 = 100.0% vs 100.0%).

Figure 6.

Subgroup analysis according to year of publications.

Meanwhile, we could not perform the subgroup analyses in the other areas: asymptomatic versus symptomatic individuals; and mothers with dual infection versus mothers with triplex infection, because the needed data were not reported by any of the included studies.

Risk of bias and study quality

Most studies (14/18) were assessed to be at moderate risk of bias. There were four studies at low risk of bias. The domain on which studies most often scored poorly were on adequacy of sample size and adequacy of response rate. The details of the quality and risk of bias of each included study was described in Appendices S1A, S1B, and S1C. Overall, the studies showed a moderate risk of bias.

Publication bias

Funnel chart and Egger test were done to evaluate for possible publication bias. Figure 7 shows the Funnel plot of the included studies on HIV mono-infections. The funnel chart revealed symmetrical funnel plot and the test level was α = 0.50.

Figure 7.

Funnel plot showing the symmetry of the studies included for HIV mono-infection population.

Discussion

The motivation for this systematic review was that despite the World Health Organization (WHO) global ambition of eliminating HIV and viral hepatitis infection by 2030, there has been major gaps in this global hepatitis elimination effort that continuously threaten achievement of the WHO targets. Experts in HIV and viral hepatitis have identified these gaps and challenges and have pointed that there should be priorities on epidemiological and MTCT rate studies. The principal findings in this systematic review were that the rate of MTCT of HIV was 2.74% and HBV was 55.49% among mother–infant pairs with mono-infection of HIV and HBV respectively. We identified no completed studies examining MTCT rates and factors associated with MTCT of HIV, HBV, and HCV among mother–infant pairs with dual or triplex infections of HIV, HBV, and HCV in Nigeria. However, limited data are available on the rates of MTCT of HIV and HBV among mother–infant pairs with mono-infections of HIV or HBV in Nigeria, indicating the need for further investigation of the rate of MTCT of HIV, HBV, and HCV among pregnant women with dual or triplex infections of HIV, HBV, and HCV in Nigeria.

The pooled MTCT rate of 2.74% for HIV was lower than 3.6% reported in Swaziland, 38 3.5% in Romania, 39 3·1% in Israel, 40 but higher than 1% reported in Oman 41 and 0% reported in Brazil. 42 Although the pooled MTCT rate of 2.74% is reported in this study, this is not a reflection of good PMTCT program in Nigeria because Nigeria still accounts for the highest number of new pediatric HIV infections in the world. 43 However, current WHO Option B+ for HAART-based PMTCT interventions require that breastfeeding is allowed for up to 12 months with the mother on the lifetime use of antiretroviral (ARV) therapy and the commencement of ARV regardless of the CD4 count, and the infant on daily nevirapine in the first 6 weeks. This is anticipated to have a positive impact on MTCT reduction especially in breastfeeding population like Nigeria.23–25

In addition, the pooled low HIV MTCT rate could probably be due to the fact that high number of women attending antenatal care usually receive ARV therapy. These combined interventions when followed effectively can reduce the risk of MTCT to low as 2%. Without intervention, 30%–45% of all infants born to HIV-positive mothers may be infected and 10%–20% will be infected through breastfeeding.26,27 This finding has become necessary so as to ensure that Nigeria meets its target since their commencement of PMTCT of HIV program in 2002 in tertiary health institutions spread across the country. 12

The pooled MTCT rate for HBV of 55.49% is higher than a recent study in Ethiopia by Kiros et al. 44 and in Ghana by Dun-Dery et al. 45 which reported an MTCT rate of 30.9% and 34.7% respectively for HBV. This might be due to inadequate treatment for HBsAg carrier mothers and inadequate vaccination coverage for pregnant mothers. 46 Therefore, preventing MTCT is essential to achieving the WHO goal of HBV elimination by 2030.8,9 This can be achieved through the birth dose vaccination for newborns from HBsAg carrier mothers and antiviral prophylaxis of HBeAg-positive pregnant women and those with high viral load as well as antenatal hepatitis B immunoglobulins.47,48 However, the pooled MTCT rate of HBV of 55.49% (95% CI: 35.93%–75.04%) at birth is high and may not reflect the actual vertical transmission rate. This is because passively acquired maternal antibody may persist in the neonate for up to 6 months. 48 However, the occurrence of neonatal HBV-antibody in the presence of high maternal plasma viral DNA may suggest a higher risk of perinatal infection. 48

There was no recorded MTCT rate for HCV even for mono-infections in Nigeria. Previous Cameroonian study documented an MTCT rate of HCV to be 0.0% at 6 weeks and 6 months of age, 49 while another study that reported vertical transmission rate that was restricted to infants born to viremic mothers revealed an MTCT rate of HCV to be 3.6% (95% CI: 0.004–0.123) using HCV-RNA PCR analysis in Greece. 50 The failure to detect any publication for HCV vertical transmission in Nigeria suggests that there are still research gaps on the area. 51

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of the literature to identify MTCT rates of HIV and HBV among pregnant women and their infant pairs with single, dual, and triplex infections of HIV, HBV, and HCV in Nigeria. We could not identify any previous systematic review on the topic except the one on preventive cascade theory on HIV-AIDS. 52 Elimination of MTCT of HIV and hepatitis in Nigeria will require the implementation of feasible, culturally acceptable, and sustainable interventions to address the health system-related challenges.8,9 In this study, risk factors were not evaluated. Therefore, further studies assessing risk factors are needed.

This study has a sort of strength in that it used multiple databases with no language restriction in order not to miss any eligible study. We performed a comprehensive search, including a thorough search of the gray literature, and two review authors independently sifted all references (double review process). We were restrictive in our inclusion criteria with regards to population of studies and country of studies, as we planned to include only studies whose mother–infant pairs had single, dual, and triplex infections of HIV, HBV, and HCV in Nigeria. Given the high burden of HIV, HBV, and HCV in Nigeria, the study is relevant as the findings can inform interventions for the control and prevention of these diseases.

However, the study is not free from potential limitations as it may have been affected by the lack of published completed studies. However, we identified one ongoing study on dual and triplex infections examining the seroprevalence, seroconversion rate, the rate and risk factors for MTCT of the dual or triplex infection in pregnancy using PCR at birth and 6 weeks post-delivery in Nigeria. 14

Conclusion

The pooled rate of MTCT of HIV was 2.74% and HBV was 55.49% among mother–infant pairs with mono-infection of HIV and HBV, respectively. No data exists on rates of MTCT of HCV on mono-infection or MTCT of HIV, HBV, and HCV among mother–infant pairs with dual or triplex infection of HIV, HBV, and HCV in Nigeria. Researchers need to be pro-active in this area as there is currently a substantial research gap in the evidence on MTCT rates of HIV, HBV, and HCV among mother–infants pairs with dual or triplex infection of HIV, HBV, and HCV in Nigeria.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-smo-10.1177_20503121221095411 for Mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus among pregnant women with single, dual or triplex infections of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus in Nigeria: A systematic review and meta-analysis by George Uchenna Eleje, Chinyere Ukamaka Onubogu, Preye Owen Fiebai, Ikechukwu Innocent Mbachu, Godwin Otuodichinma Akaba, Olabisi Morebise Loto, Hadiza Abdullahi Usman, Ayyuba Rabiu, Moriam Taiwo Chibuzor, Rebecca Chinyelu Chukwuanukwu, Ngozi Nneka Joe-Ikechebelu, Chike Henry Nwankwo, Stephen Okoroafor Kalu, Chukwuanugo Nkemakonam Ogbuagu, Shirley Nneka Chukwurah, Chinwe Elizabeth Uzochukwu, Ijeoma Chioma Oppah, Aishat Ahmed, Richard Obinwanne Egeonu, Chiamaka Henrietta Jibuaku, Samuel Oluwagbenga Inuyomi, Bukola Abimbola Adesoji, Ubong Inyang Anyang, Uchenna Chukwunonso Ogwaluonye, Ekene Agatha Emeka, Odion Emmanuel Igue, Ogbonna Dennis Okoro, Prince Ogbonnia Aja, Chiamaka Perpetua Chidozie, Hadiza Sani Ibrahim, Fatima Ele Aliyu, Aisha Ismaila Numan, Solace Amechi Omoruyi, Osita Samuel Umeononihu, Chukwuemeka Chukwubuikem Okoro, Ifeanyi Kingsley Nwaeju, Arinze Anthony Onwuegbuna, Eric Okechukwu Umeh, Sussan Ifeyinwa Nweje, Lydia Ijeoma Eleje, Ifeoma Clara Ajuba, David Chibuike Ikwuka, Emeka Philip Igbodike, Chisom God’swill Chigbo, Uzoamaka Rufina Ebubedike, Chigozie Geoffrey Okafor, Nnaedozie Paul Obiegbu, Ibrahim Adamu Yakasai, Oliver Chukwujekwu Ezechi and Joseph Ifeanyichukwu Ikechebelu in SAGE Open Medicine

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Moriam Chibuzor of Cochrane Nigeria for her role in developing the search strategy and electronic searching of databases.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Conceptualization: George Eleje; Data curation: George Eleje, David Ikwuka, Chisom Chigbo and Chinyere Onubogu; Formal analysis: George Eleje; Funding acquisition: George Eleje; Investigation: All authors; Methodology: All authors; Project administration: All authors; Resources: George Eleje; Software: George Eleje; Supervision: George Eleje; Validation: George Eleje, Emeka Igbodike, Ijeoma Oppah, Uchenna Ogwaluonye and Chinyere Onubogu; Visualization: All authors; Writing—original draft: All authors; Writing—review and editing: All authors; George Eleje, Richard Egeonu, Ikechukwu Mbachu and Chinyere Onubogu accessed and verified the data underlying the study.

Disclosure statement for publication: All authors have made substantial contributions to: conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version submitted. This manuscript has not been submitted for publication in another journal.

Data availability: All data underlying the results are available as part of the article and no additional source data are required.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval and consent to participate: Ethical approval was not applicable because it is a systematic review of primary studies.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was funded by TETFund National Research Fund 2019 (Grant number TETFund/DR&D/CE/NRF/STI/33). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the TETFund. The funders had no role in the design of the study or writing of the manuscript. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

ORCID iDs: George Uchenna Eleje  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0390-2152

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0390-2152

Lydia Ijeoma Eleje  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8587-289X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8587-289X

Uzoamaka Rufina Ebubedike  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1682-4728

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1682-4728

Joseph Ifeanyichukwu Ikechebelu  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2515-8464

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2515-8464

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)/United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Progress towards the start free, stay free, AIDS free targets 2020 report. Geneva: UNAIDS, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ezechi OC, Kalejaiye OO, Gab-Okafor CV, et al. Sero-prevalence and factors associated with hepatitis B and C co-infection in pregnant Nigerian women living with HIV infection. Pan Afr Med J 2014; 17: 197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sherman KE, Rouster SD, Chung RT, et al. Hepatitis C virus prevalence among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: a cross-sectional analysis of the US adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 34(6): 831–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Soriano V, Barreiro P, Nuñez M. Management of chronic hepatitis B and C in HIV-coinfected patients. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006; 57(5): 815–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sadoh AE, Sadoh WE, Iduoriyekemwen NJ. HIV co-infection with hepatitis B and C viruses among Nigerian children in an antiretroviral treatment programme. S Afr J Child Health 2011; 5(1): 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eke CB, Onyire NB, Amadi OF. Prevention of mother to child transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in Nigeria: a call to action. Niger J Paediatr 2016; 43(3): 201–208. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Olakunde BO, Adeyinka DA, Olawepo JO, et al. Towards the elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Nigeria: a health system perspective of the achievements and challenges. Int Health 2019; 11(4): 240–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization (WHO). Hepatitis B, 2021, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b (accessed 10 March 2022).

- 9. Woodring J, Ishikawa N, Nagai M, et al. Integrating HIV, hepatitis B and syphilis screening and treatment through the Maternal, Newborn and Child Health platform to reach global elimination targets. Western Pac Surveill Response J 2017; 8(4): 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372: n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eleje G, Ele P, Okocha E, et al. Epidemiology and clinical parameters of adult human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome at the initiation of antiretroviral therapy in South eastern Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2014; 4(2): 217–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, et al. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015; 13(3): 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen Y, Du L, Geng X, et al. Implement meta-analysis with non-comparative binary data in RevMan software. Chin J Evid Based Med 2014; 14: 889–896. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eleje GU, Mbachu II, Ogwaluonye UC, et al. Prevalence, seroconversion and mother-to-child transmission of dual and triplex infections of HIV, hepatitis B and C viruses among pregnant women in Nigeria: study protocol. Reprod Health 2020; 17(1): 144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nwolisa E, Mbanefo F, Ezeogu J, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B co-infection amongst HIV infected children attending a care and treatment centre in Owerri, South-eastern Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J 2013; 14: 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Offor E, Onakewhor JU, Okonofua FE. Maternal and neonatal seroprevalence of human immunodeficiency virus antibodies in Benin City, Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol 2000; 20(6): 589–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lawal MA, Adeniyi OF, Akintan PE, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for hepatitis B and C viral co-infections in HIV infected children in Lagos, Nigeria. PLoS One 2020; 15(12): e0243656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Okechukwu AA, Thairu Y, Dalili MS. HIV co-infection with hepatitis B and C and liver function in children and adolescents on antiretroviral therapy in a Tertiary Health Institution in Abuja. West Afr J Med 2020; 37(3): 260–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Audu R, Onwuamah C, Salu O, et al. Development and implementation challenges of a quality assured HIV infant diagnosis program in Nigeria using dried blood spots and DNA polymerase chain reaction. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2014; 31(4): 433–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eleje GU, Edokwe ES, Ikechebelu JI, et al. Mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) among HIV-infected pregnant women on highly active anti-retroviral therapy with premature rupture of membranes at term. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2018; 31(2): 184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Okafor I, Ugwu E, Obi S, et al. Virtual elimination of mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus in mothers on highly active antiretroviral therapy in Enugu, South-Eastern Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2014; 4(4): 615–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ben O, Yusuf T. PCR pattern of HIV-exposed infants in a tertiary hospital. Pan Afr Med J 2014; 18: 345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sagay AS, Ebonyi AO, Meloni ST, et al. Mother-to-child transmission outcomes of HIV-exposed infants followed up in Jos North-central Nigeria. Curr HIV Res 2015; 13(3): 193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Onubogu CU, Ugochukwu EF, Egbuonu I, et al. Adherence to infant-feeding choices by HIV-infected mothers at a Nigerian tertiary hospital: the pre-“rapid advice” experience. S Afr J Clin Nutr 2015; 28(4): 180–186. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chukwuemeka IK, Fatima MI, Ovavi ZK, et al. The impact of a HIV prevention of mother to child transmission program in a Nigerian early infant diagnosis centre. Niger Med J 2014; 55(3): 204–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kalu S, Reynolds F, Petra G, et al. Infant feeding choices practiced among HIV positive mothers attending a Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission (PMTCT) of HIV program in Nnewi, Nigeria. J AIDS Clin Res 2014; 5(5): 1000300. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Isah AM, Igboeli NU, Adibe MO, et al. Evaluation of prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV in a tertiary health institution in south-eastern Nigeria. J AIDS HIV Res 2016; 8(8): 114–120. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ikechebelu JI, Ugboaja JO, Kalu SO, et al. The outcome of prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV infection programme in Nnewi, southeast Nigeria. Niger J Med 2011; 20(4): 421–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Oluwayemi IO, Olatunya SO, Ogundare EO. PCR results and PMTCT treatment outcomes among HIV-exposed infants in a Tertiary Hospital in Nigeria, 2010-2014. Int J MCH AIDS 2015; 3(2): 168–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Markson JA, Umoh AV. Evaluation of PMTCT programme implementation in general hospital, Iquita Oron, Akwa-Ibom state, Nigeria. Ibom Med J 2013; 6(1): 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Afolabi AY, Bakarey AS, Kolawole OE, et al. Investigation of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in pregnancy and among HIV-exposed infants accessing care at a PMTCT clinic in southwest Nigeria. J Immunoassay Immunochem 2018; 39(4): 403–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Anoje C, Aiyenigba B, Suzuki C, et al. Reducing mother-to-child transmission of HIV: findings from an early infant diagnosis program in south-south region of Nigeria. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Itiola AJ, Goga AE, Ramokolo V. Trends and predictors of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in an era of protocol changes: findings from two large health facilities in North East Nigeria. PLoS One 2019; 14(11): e0224670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Afe AJ, Adewum N, Emokpa A, et al. Outcome of PMTCT services and factors affecting vertical transmission of HIV infection in Lagos, Nigeria. HIV AIDS Rev 2011; 10(1): 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Onakewhor JU, Offor E, Okonofua FE. Maternal and neonatal seroprevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in Benin City, Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol 2001; 21(6): 583–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Eke AC, Eke UA, Okafor CI, et al. Prevalence, correlates and pattern of hepatitis B surface antigen in a low resource setting. Virol J 2011; 8: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Olaleye OA, Kuti O, Makinde NO, et al. Perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in Ile-Ife, South Western, Nigeria. J Neonatal Perinatal Med 2013; 6(3): 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chouraya C, Machekano R, Mthethwa S, et al. Mother-to-child transmission of HIV and HIV-free survival in Swaziland: a community-based household survey. AIDS Behav 2018; 22(suppl. 1): 105–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Marcu EA, Dinescu SN, Pădureanu V, et al. Perinatal exposure to HIV infection: the experience of Craiova Regional Centre, Romania. Healthcare 2022; 10(2): 308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mor Z, Sheffer R, Chemtob D. Mother-to-child HIV transmissions in Israel, 1985-2011. Epidemiol Infect 2017; 145(9): 1913–1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Elgalib A, Al-Hinai F, Al-Abri J, et al. Elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Oman: a success story from the Middle East. East Mediterr Health J 2021; 27(4): 381–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gouvêa ADN, Trajano AJB, Monteiro DLM, et al. Vertical transmission of HIV from 2007 to 2018 in a reference university hospital in Rio de Janeiro. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2020; 62: e66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Omonaiye O, Kusljic S, Nicholson P, et al. Post Option B+ implementation programme in Nigeria: determinants of adherence of antiretroviral therapy among pregnant women with HIV. Int J Infect Dis 2019; 81: 225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kiros KG, Goyteom MH, Tesfamichael YA, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus infection, mother-to-child transmission, and associated risk factors among delivering mothers in Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Infect Dis Ther 2020; 9(4): 901–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dun-Dery F, Adokiya MN, Walana W, et al. Assessing the knowledge of expectant mothers on mother-to-child transmission of viral hepatitis B in Upper West region of Ghana. BMC Infect Dis 2017; 17(1): 416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eleje GU, Akaba GO, Mbachu II, et al. Pregnant women’s hepatitis B vaccination coverage in Nigeria: a national pilot cross-sectional study. Ther Adv Vaccines Immunother. Epub ahead of print 29 July 2021. DOI: 10.1177/25151355211032595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ugwu EO, Eleje GU, Ugwu AO, et al. Antivirals for prevention of hepatitis B virus mother-to-child transmission in human immunodeficiency virus positive pregnant women co-infected with hepatitis B virus (Protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; 2020(6): CD013653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Eke AC, Eleje GU, Eke UA, et al. Hepatitis B immunoglobulin during pregnancy for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 2017(2): CD008545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Njouom R, Pasquier C, Ayouba A, et al. Low risk of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus in Yaounde, Cameroon: the ANRS 1262 study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005; 73(2): 460–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Syriopoulou V, Nikolopoulou G, Daikos GL, et al. Mother to child transmission of hepatitis C virus: rate of infection and risk factors. Scand J Infect Dis 2005; 37(5): 350–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Eleje GU, Rabiu A, Mbachu II, et al. Awareness and prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among pregnant women in Nigeria: a national pilot cross-sectional study. Womens Health. Epub ahead of print 14 July 2021. DOI: 10.1177/17455065211031718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Joe-Ikechebelu NN, Azuike EC, Nwankwo BE, et al. HIV prevention cascade theory and its relation to social dimensions of health: a case for Nigeria. HIV AIDS 2019; 11: 193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-smo-10.1177_20503121221095411 for Mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus among pregnant women with single, dual or triplex infections of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus in Nigeria: A systematic review and meta-analysis by George Uchenna Eleje, Chinyere Ukamaka Onubogu, Preye Owen Fiebai, Ikechukwu Innocent Mbachu, Godwin Otuodichinma Akaba, Olabisi Morebise Loto, Hadiza Abdullahi Usman, Ayyuba Rabiu, Moriam Taiwo Chibuzor, Rebecca Chinyelu Chukwuanukwu, Ngozi Nneka Joe-Ikechebelu, Chike Henry Nwankwo, Stephen Okoroafor Kalu, Chukwuanugo Nkemakonam Ogbuagu, Shirley Nneka Chukwurah, Chinwe Elizabeth Uzochukwu, Ijeoma Chioma Oppah, Aishat Ahmed, Richard Obinwanne Egeonu, Chiamaka Henrietta Jibuaku, Samuel Oluwagbenga Inuyomi, Bukola Abimbola Adesoji, Ubong Inyang Anyang, Uchenna Chukwunonso Ogwaluonye, Ekene Agatha Emeka, Odion Emmanuel Igue, Ogbonna Dennis Okoro, Prince Ogbonnia Aja, Chiamaka Perpetua Chidozie, Hadiza Sani Ibrahim, Fatima Ele Aliyu, Aisha Ismaila Numan, Solace Amechi Omoruyi, Osita Samuel Umeononihu, Chukwuemeka Chukwubuikem Okoro, Ifeanyi Kingsley Nwaeju, Arinze Anthony Onwuegbuna, Eric Okechukwu Umeh, Sussan Ifeyinwa Nweje, Lydia Ijeoma Eleje, Ifeoma Clara Ajuba, David Chibuike Ikwuka, Emeka Philip Igbodike, Chisom God’swill Chigbo, Uzoamaka Rufina Ebubedike, Chigozie Geoffrey Okafor, Nnaedozie Paul Obiegbu, Ibrahim Adamu Yakasai, Oliver Chukwujekwu Ezechi and Joseph Ifeanyichukwu Ikechebelu in SAGE Open Medicine