Abstract

Social corbiculate bees are major pollinators. They have characteristic bacterial microbiomes associated with their hives and their guts. In honeybees and bumblebees, worker guts contain a microbiome composed of distinctive bacterial taxa shown to benefit hosts. These benefits include stimulating immune and metabolic pathways, digesting or detoxifying food, and defending against pathogens and parasites. Stressors including toxins and poor nutrition disrupt the microbiome and increase susceptibility to opportunistic pathogens. Administering probiotic bacterial strains may improve the health of individual bees and of hives, and several commercial probiotics are available for bees. However, evidence for probiotic benefits is lacking or mixed. Most bacterial species used in commercial probiotics are not native to bee guts. We present new experimental results showing that cultured strains of native bee gut bacteria colonize robustly while bacteria in a commercial probiotic do not establish in bee guts. A defined community of native bee gut bacteria resembles unperturbed native gut communities in its activation of genes for immunity and metabolism in worker bees. Although many questions remain unanswered, the development of natural probiotics for honeybees, or for commercially managed bumblebees, is a promising direction for protecting the health of managed bee colonies.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Natural processes influencing pollinator health: from chemistry to landscapes’.

Keywords: apiculture, foulbrood, Nosema, Snodgrassella, Gilliamella, microbiome engraftment

1. Introduction

Animal-associated microbial communities often benefit their hosts, and hosts therefore benefit from efforts to protect microbiomes, by limiting adverse impacts of toxins or poor nutrition. In addition to protecting native microbiomes, host health might be enhanced through the application of beneficial, live microorganisms, that is, probiotics [1]. In this article, we explore using probiotics to bolster the health of managed colonies of honeybees and bumblebees. We first review work on the naturally occurring microbial communities associated with social bees, including the considerable evidence on beneficial effects of the native adult gut microbiota. We then summarize investigations on the potential for probiotics in honeybees, with emphasis on probiotics composed of bacterial strains native to honeybee guts. A major unanswered question is whether probiotics establish and persist in recipient hosts. We present new experimental results showing that non-native bacterial strains from a commercial probiotic product fail to establish in the worker bee gut, but a mixture of native gut bacterial strains colonizes robustly and resembles a natural microbiota in eliciting expression of bee genes related to immunity and metabolism. Finally, we discuss future prospects for probiotics in managed bee colonies, including natural strains isolated from bees and natural strains genetically engineered to protect bees.

2. Background on microbiomes of social corbiculate bees

Recent research has revealed that naturally occurring microbiomes of social corbiculate bees which include honeybees (genus Apis), stingless bees (tribe Meliponini) and bumblebees (genus Bombus) are distinctive, have evolved long term with hosts and play positive roles in host health. We summarize these studies and refer readers to other reviews for more details [2–4].

(a) . Adult worker gut microbiomes

Most work has focused on the distinctive communities in guts of workers of the western honeybee Apis mellifera. These communities are dominated by five to eight bee-restricted bacterial lineages [5,6]. Bumblebees and stingless bees harbour communities composed of closely related bacterial lineages, with some exceptions in stingless bee groups that have lost particular gut bacterial lineages [6,7].

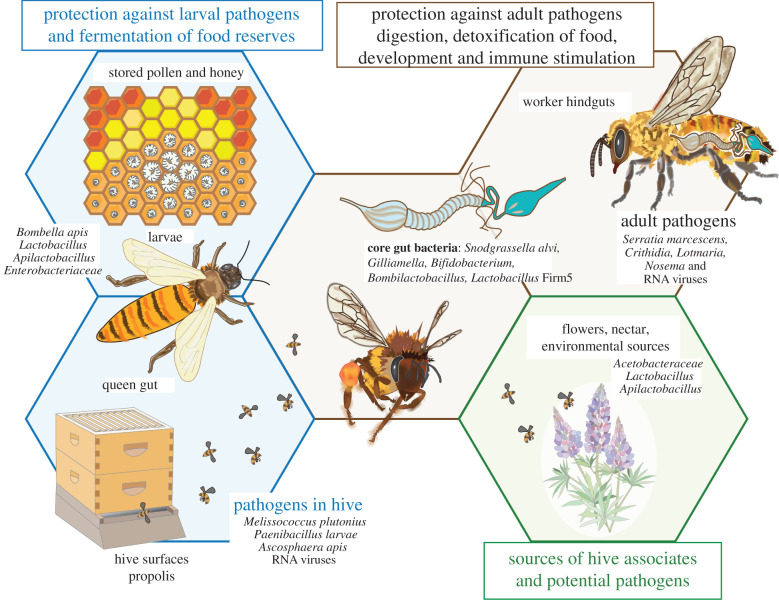

In Apis and Bombus, the main bacterial gut symbionts are acquired via social contact within colonies. Apis mellifera workers are colonized soon after emergence as adults, through contact with other workers [8]. The transmitted bacteria grow to a stable community, with a characteristic composition and size, of about 108 cells per worker [9], with similar numbers in bumblebees [6]. Each bacterial species has a characteristic distribution in the ileum or rectum of the hindgut [5,9] (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Microorganisms associated with honeybees and their hives. Distinct microbial communities occupy different niches, including a distinct community in hindguts of adult worker bees and a set of microbes exchanged between hive surfaces, food reserves, larval guts, queen guts and worker foreguts. These communities have been shown to confer benefits for bees and hives, but they also include pathogens of larvae and/or adults. Some of these microbes are acquired from or exchanged at environmental sources including nectar and plant surfaces.

For both honeybees and bumblebees, native gut communities have been shown to support adult worker development and health [2,3]. In experiments that compared workers with or without a normal gut microbiota, the former enjoy a range of benefits that include protection against bacterial, viral, and eukaryotic pathogens [10,11], digestion of components of pollen cell walls [12,13], microbial detoxification of certain sugars [14], stimulation of insulin signalling, appetite, gut development, and weight gain [15] and enhanced production of bee-encoded P450 enzymes that can neutralize dietary toxins [16], although the gut microbiota does not protect against widely used insecticides [17]. In bumblebees, the gut microbiota appears to protect against selenate toxicity [18]. Most experiments in bumblebees (Bombus terrestris and Bombus impatiens) have focused on protection against parasites and have repeatedly shown that the gut microbiota can defend against trypanosomatid parasites [19–21].

The most widely documented benefit of the adult gut microbiota is protection against invasion by pathogens and parasites. Such protection called ‘colonization resistance’ is a feature of mammalian gut communities [22]. This protective effect may partly reflect enhanced bee immune responses, as the gut microbiota stimulates immune pathways [11,23,24]. However, direct microbe–microbe interactions also appear to contribute, as individual strains vary in protective capacity [20] and possess varying mechanisms for inter-bacterial antagonism [25]. The establishment of biofilms within bee guts also may impose a physical barrier to pathogenic invasion [26,27].

While most evidence for beneficial effects of the bee microbiota comes from laboratory-based studies, experimental and observational evidence supports similar effects in field colonies and populations. In bumblebee populations, microbiota-conferred protection against parasites is supported by lower parasite incidence in individuals with an intact gut microbiota [27]. In honeybees, exposure to antibiotic chemicals disrupts the microbiota and lowers worker survivorship both within hives and following laboratory challenge with opportunistic bacterial or eukaryotic pathogens [16,28–31].

(b) . Queen, larval and hive-associated microbiomes

Honeybee queens have gut communities drastically different from those of workers; they lack the core species present in workers, are more erratic in composition and size, and largely consist of environmentally widespread bacterial species [32–34]. By contrast, bumblebee queens have a gut microbiota similar to that of workers and dominated by the characteristic bacterial lineages found in guts of adult corbiculate bees broadly [35].

Microbial communities are also associated with larvae, food reserves and hive surfaces, and these may also affect vigour of the overall colony. In honeybees, all of these communities differ dramatically from those found in adult worker guts [36]. One of the most abundant bacterial species associated with honeybee larvae is a cluster of Acetobacteraceae initially recovered at very low abundance from adult workers [37,38] and later found to be frequent in larval guts and queen guts [32–34,39]. It was initially called ‘Alpha 2.2’, then described as Parasaccharibacter apium [36] and more recently placed in its own genus as Bombella apis [40]. Several strains isolated from larvae are able to persist in larvae, royal jelly, hypopharyngeal glands and nurse crops [36].

Host-associated communities also can include organisms that are deleterious for hosts [41]. In honeybees, these include viruses such as deformed wing vrus and others [42], bacterial pathogens of larvae such as American and European foulbrood (Paenibacillus larvae and Melissococcus plutonius) [43], microsporidians in the genus Nosema [44], trypanosomatids including Crithidia [45] and Lotmaria [45], fungal pathogens such as chalkbrood (Ascosphaera apis) [46] and opportunistic bacterial pathogens such as Serratia marcescens [47,48]. These deleterious organisms tend to be invasive and sporadic, but when they dominate, their harmful effects can overpower any benefits of the usual community.

(c) . Threats to bee microbiomes

The gut microbiota is key to honeybee health, but it is subject to disruption. For example, the gut community composition is drastically affected by exposure to antibiotics [29,49] or to some herbicides [28,30,50]. Bee gut communities can be impacted by diet, including nutrient quantity, nutrient composition and phytochemicals present in nectar, pollen and propolis [51], and by temperature [52,53]. In honeybees, perturbed gut communities are more susceptible to invasion by pathogens, as observed in challenge experiments with S. marcescens [28] and Nosema [10,54]. Honeybee workers with dysbiosis, defined as unhealthy disruption of the normal microbiota, have higher mortality rates within hives [28,29]. Bumblebees also are subject to gut dysbiosis [27,55], which can increase their susceptibility to pathogens [21].

3. Approaches and challenges for probiotic treatments

The mounting evidence that the native microbiota is key to bee health but vulnerable to disruption raises the question of whether managed colonies of these insects might be strengthened through probiotic treatments that deliver beneficial bacteria. Such treatments might prevent, or cure dysbiosis. One type of probiotic consists of bacteria that are intended to promote health and a stable microbiome without themselves persisting in the host [1]. Much of the human probiotic industry is based on ingesting organisms such as Lactobacillus or Bifidobacterium used in fermenting food; these do not colonize guts but may still promote a healthy microbiome although evidence for this is mixed [56].

A second probiotic strategy involves inoculation with microbial strains that are themselves native to the host gut and that could establish and persist long term in the host. For example, hosts experiencing dysbiosis can be treated through the direct transfer of native microbial communities from healthy individuals. In humans, such treatments, called faecal microbiota transplants, have shown efficacy for the treatment of some bowel disorders.

Both approaches are potentially beneficial in bees. Most commercial probiotics currently contain only non-native bacteria from the food industry as in human probiotic mixtures; however, some incorporate a mixture of non-native and native bacteria [57]. Published analyses of persistence in bee guts are not available. However, experimental work has shown that transfers of native gut bacteria between worker honeybees, accomplished by providing homogenate from donor guts to recipient bees, result in stable colonization, typical community composition and host benefits (e.g. [15]). However, direct transfers between hosts carry the risk of introducing pathogenic organisms, potentially causing more harm than benefit, as occasionally observed in human faecal transfers (e.g. [58]).

Below we summarize studies of bee probiotics (electronic supplementary material, table S1). A recent publication provides an exhaustive compilation [57].

(a) . Probiotics for larvae, queen and hive health

The most evident bee pathogens affect larvae, a vulnerable stage of development for honeybees and the stage most visible to beekeepers, since affected bees die in the hive. Larval parasites and pathogens include Varroa mites, the bacteria P. larvae and M. plutonius [43], the chalkbrood fungus As. apis and several RNA viruses.

Several investigators have sought to directly protect larvae with probiotics. A strain of Bombella apis enhanced larval survival in vitro and was investigated as a probiotic hive supplement, delivered in custom-made pollen patties [59]. However, Bombella apis had no effect on colony-level measures of brood area, food storage or foraging rate. Bees from hives supplemented with Bombella apis appeared to resist Nosema infection better, as fewer Nosema spores were present after an in vitro challenge. Later tests of whether Bombella apis inoculation could protect larvae against M. plutonius did not reveal protective effects [60]. Miller et al. [61] recently demonstrated that some Bombella apis strains produce a metabolite that inhibits fungal growth both in vitro and in vivo. Nosema is a microsporidian, a group closely related to fungi, so potentially the same mechanism underlies this fungal suppression and the reduced Nosema loads in treated colonies. These experiments were performed in the laboratory, so it remains to be tested if providing these strains as probiotics to hives will be beneficial.

Recently, researchers have also tested commercially available probiotic formulations at the hive scale. Daisley et al. [62] focused on hive supplementation with a mixture of two non-bee-associated Lactobacillus strains (Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus rhamnosus) and one hive-associated strain: Apilactobacillus kunkeei. They found that supplementation helped hives resist P. larvae. By contrast, Stephan et al. [63] provided a probiotic mixture of several hive- and gut-associated strains of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium to hives infected with P. larvae and treated or not with antibiotics, but found no improvements in colony fitness. Differences in the design and execution of these experiments, or in the status of the study hives, can explain the different outcomes. These two studies illustrate the persistent issues of reproducibility that face honeybee probiotics research.

Queens remain in the hive and are vital to hive health, and queen longevity and productivity have declined recently, potentially owing in part to hive treatments for mites [64]. The queen's own gut microbiome may influence her health and productivity, but studies of queen microbiomes have not addressed links to fecundity or colony productivity [32,34]. Some probiotic applications appear to improve egg-laying in hives [65,66], potentially owing to impacts on the queen microbiome. Further work is needed to determine if microbiota manipulations in queens can improve hive health.

(b) . Probiotics for adult workers

Workers comprise the vast majority of individuals in hives and are responsible for all hive-level functions except for egg-laying. Colony declines, particularly those associated with classic colony collapse disorder, are often associated with the disappearance of workers from a colony [67]. Since sick workers tend to leave the hive to avoid the spread of disease [68,69], they are less obvious to beekeepers than are sick larvae. Thus, opportunistic pathogens of adult workers are probably underappreciated as factors in overall colony health [48].

Many recent studies indicate that the native worker gut microbiota is perturbed by agrochemicals, such as antibiotics that are used in hives to treat larval infections and in fields to control crop pathogens, and other pesticides, sprayed in areas near colonies. These perturbations are linked to increased susceptibility of workers to infections by opportunistic pathogens [28,29,31,50,54]. For example, workers are more likely to die from S. marcescens strains present in hives following microbiota perturbation by antibiotics or glyphosate [28,47]. Potentially, probiotic treatment with natural gut strains from the native microbiota could replenish perturbed gut communities. Recent experimental studies have shown that bees mono-colonized with single or multiple strains of native gut bacteria can control the overproliferation of S. marcescens in the bee gut [11,70]. Similar overproliferation is observed in microbiota-deprived bees or antibiotic-treated bees [70].

To date, almost all studies on the use of probiotics to control infections in workers have investigated non-native strains [71,72] In one such study, Daisley et al. [62] saw shifts in microbial composition in the guts of worker bees and found that probiotic supplementation, besides increasing the expression of bee immunity genes, such as defensin-1, had a negative correlation with the abundance in guts of Commensalibacter, Frischella and P. larvae, but did not change overall bacterial loads. A follow-up study [73] reported that antibiotic-induced dysbiosis in workers could be countered by providing the same probiotic mixture to hives, and that the probiotic bacterial strains were detected in workers post-supplementation.

Native gut probiotics, consisting of isolates from bee guts, could potentially replenish perturbed gut communities and provide sustained protection against pathogens and parasites of workers. Powell et al. [31] found that hive treatment with recommended levels of tylosin (antibiotic used against P. larvae) results in severe disruption of worker gut communities and in higher mortality when challenged with S. marcescens. This increased susceptibility was lessened by treatment with a probiotic mixture of strains of native gut bacteria, suggesting that native gut probiotics can replenish perturbed worker gut communities and thereby reduce pathogenic infections.

Nosema also takes advantage of microbial perturbations induced by antibiotics to cause disease in adult workers [54] and can itself perturb the native worker microbiota [74–76]. Many recent probiotic studies in adult honeybees have focused on Nosema and have supplemented caged bees or hives with mixtures of bacteria originating from sources other than the native bee microbiota (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1). While some of these experiments reported beneficial effects, such as reduction in Nosema spore counts and/or higher survival rates of bees [71,72,77–79], others reported a completely opposite outcome, with increases in spore counts and/or lower survival rates of bees after supplementation [80–82]. A few studies have investigated the effects of probiotics in the control of Varroa, showing a reduction in Varroa in supplemented hives [66,72,83]. However, these studies did not investigate whether these non-native bacteria persist in the bee gut or affect the native microbiota. To date, clear evidence that probiotics protect workers is lacking.

(c) . What should bee probiotics look like?

Most probiotic efforts in honeybees have not verified the basic mechanisms that contribute to probiotic usefulness. Do probiotic strains establish in bee guts? Also, do probiotics have sustained effects on bee physiology and immune responses?

Native probiotic mixtures should be standardized to contain only a beneficial community, eliminating the risk of introducing harmful entities while including the necessary community diversity to restore a stable, healthy community. Powell et al. [31] provided preliminary evidence that a defined community consisting of native gut bacteria can help to ameliorate microbiota perturbation and pathogen susceptibility.

4. New experimental results

We performed experiments aimed at addressing questions regarding probiotics for worker gut communities. We tested a defined community of native gut bacteria to examine the ability to establish and persist in the bee gut, comparing this to a commercial probiotic currently in use in apiculture. We also examined the ability of this defined community to stimulate changes in gene expression that are typically induced by the native gut community.

(a) . Natural gut bacteria, but not commercial probiotics, robustly colonize bee guts

To explore the ability of probiotic strains to persist in the bee gut, we placed newly emerged adults directly in sterile cup cages with sugar syrup and sterile pollen. We divided workers into four treatments (approx. 15 bees cup−1): no microbial exposure (NP, no probiotic), inoculation with a commercial probiotic (ProB), inoculation with a defined community of co-cultured bee gut microbiota members (DC) or inoculation with a mixture of commercial probiotic with the defined community (ProB + DC). After 5 days, we extracted total gut RNA to produce complementary DNA; thus, dead cells in the gut do not contribute to our assays. We estimated the total load of metabolically active bacteria using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and the taxonomic composition using sequencing of 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) amplicons. Detailed methods are included in the electronic supplementary material, methods.

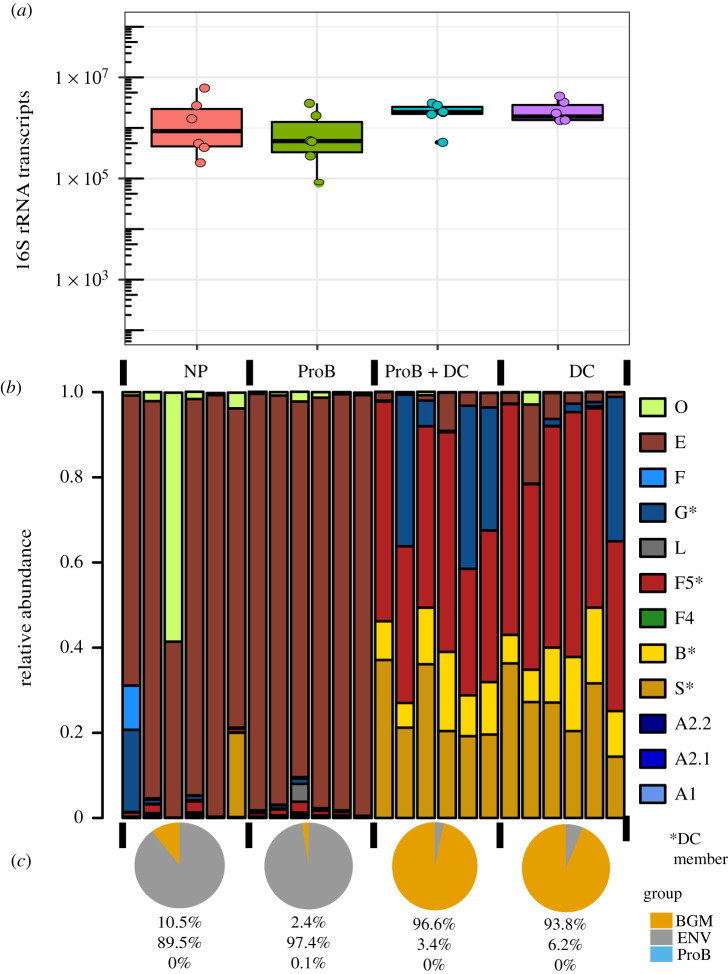

Bees in all of the treatments achieved similar bacterial loads (figure 2a). The presence of high levels of bacteria in the NP group suggests inoculation from frame surfaces as the young bees emerged, as previously observed [8]. Communities from bees in the NP group and the ProB group have a very similar taxonomic composition (figure 2b). Both groups had large components of Enterobacteriaceae, including genera that are opportunistic pathogens. An evaluation of bacteria by probable source (environment/commercial probiotic/native bee gut community) showed that the NP and ProB conditions were dominated by environmentally acquired bacteria (figure 2c). In the ProB treatment, the component probiotic taxa were present at less than 1% on average. Thus, bacteria from a non-bee gut origin establish poorly in the gut, enabling increases in opportunistic environmentally acquired taxa, largely Enterobacteriaceae. By contrast, in both treatments where native gut bacteria were used (ProB + DC and DC), native gut strains dominated (greater than 93% on average) and limited proliferation of environmentally acquired bacteria. Native strains dominated at 5 days when bees were harvested and the experiment terminated. Previous experiments showed persistence for at least 10 days following inoculation of microbiota-free bees with bee gut homogenates and further showed that the characteristic bee gut microbiota persists for the life of the adult worker under natural conditions [3,8,9]. Thus, the DC community is probably stable for longer periods.

Figure 2.

Establishment of commercial probiotic bacteria versus native bee gut bacteria 5 days post-inoculation. (a) Total bacterial load estimated by qPCR as 16S rRNA copies per 100 ng RNA. Abbreviations: NP, no probiotic; ProB, probiotic; DC, defined community of native bee gut bacteria; or ProB + DC, mixture of ProB plus DC. All conditions have similar bacterial loads (p > 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis). (b) Relative abundances of bacterial lineages as determined by 16S V4 sequencing. Abbreviations: A1, Bartonella apis; A2.1, Commensalibacter spp.; A2.2, Bombella apis; S, Snodgrassella alvi; B, Bifidobacterium spp.; F4, Bombilactobacillus spp.; F5, Lactobacillus nr. melliventris; L, environmental Lactobacilli; G, Gilliamella spp.; F, Frischella perrara; E, Enterobacteriaceae; O, other uncategorized. NP and ProB groups are dominated by Enterobacteriaceae, and both groups fed DC are dominated by core bee gut bacteria present in the DC. (c) Average percentages of bacterial taxa grouped by origin. BGM, taxa of bee gut microbiota; ENV, environmentally associated taxa; ProB, taxa in commercial probiotic mixture. Data are available online in the electronic supplementary material.

(b) . Defined native probiotics mimic effects of natural communities on host gene expression

Natural gut communities have been shown to modulate the expression of honeybee genes, including key genes involved in immunity, metabolism and development, and bees lacking a normal gut community have abnormal immune function, metabolism and weight gain [10,11,15,16]. We thus investigated if a defined community of native gut bacteria resembles complex natural gut communities in effects on host gene expression.

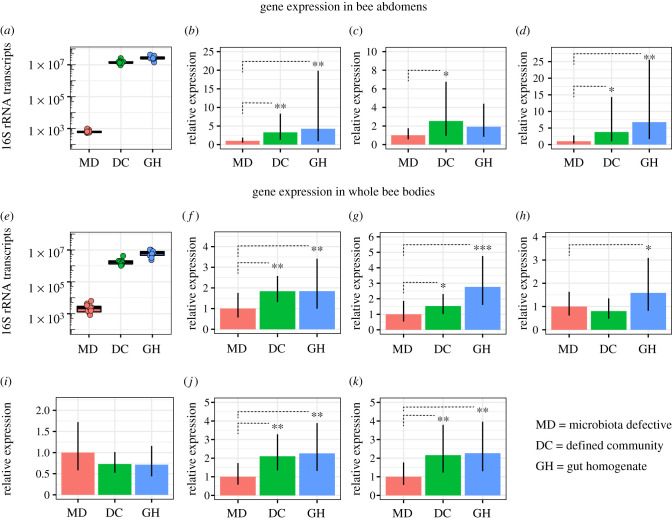

Late-stage pupae were removed from a frame and placed in plastic chambers in incubators as in [8], allowed to eclose as adults, then placed in cup cages with sugar syrup and sterile pollen. Previous work shows that this yields bees devoid or nearly devoid of gut bacteria [3,8]. We divided bees into three sets. One set (MD, microbiota deprived) was not exposed to bacteria, one set (DC, defined community of native strains) was fed a mixture of native gut strains, and one set (GH, gut homogenate) was fed fresh gut homogenate from hive workers, containing the full natural gut community. We measured expression of genes previously shown to be induced by colonization with the full gut community, including genes involved in development [15] and immunity [11,23]. In one experiment, we assayed genes for several antimicrobial peptides (apidaecin, abaecin, defensin and hymenoptaecin) known to be expressed in specific tissues. In a second experiment, we assayed genes involved in hormonal signalling (vitellogenin, insulin receptors and insulin-like peptides) and expected to be expressed throughout the body. We also assayed bacterial loads using qPCR.

DC and GH bees achieved similar bacterial loads, which were far higher than those of MD bees (figure 3a,e). The higher loads correspond to pronounced activation of key bee genes in abdomen samples (higher expression of genes encoding abaecin, apidaecin and hymenoptaecin in DC and GH bees than in MD bees) (figure 3b–d) and in whole-body samples (higher expression of genes encoding defensin-2, vitellogenin, and insulin receptors 1 and 2 in DC and GH bees, and insulin-like peptide 1 in GH bees) (figure 3f–k). Thus, the defined community mimics the native full microbiota in inducing the expression of bee genes involved in immunity and metabolism.

Figure 3.

Expression of genes underlying immunity and hormonal signalling in bees lacking a native microbiota (MD), colonized with a defined community of native bee gut strains (DC), or colonized with gut homogenate from a donor bee (GH). (a) Bacterial load estimated as bacterial 16S rRNA copies and (b–d) relative transcript levels of genes encoding abaecin (b), apidaecin (c) and hymenoptaecin (d) in bee abdomens across groups (n = 11 per group). (e) Bacterial 16S rRNA copies and (f–k) relative transcript levels of genes encoding defensin 2 (f), vitellogenin (g), insulin-like peptides 1 (h) and 2 (i), and insulin receptors 1 (j) and 2 (k) in whole bee bodies across groups (n = 10 per group). The linear regression ‘lm’ option in the pcr package in R was applied to estimate differences between groups. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Data are available online in the electronic supplementary material. (Online version in colour.)

5. Engineered probiotics in bees

Native gut bacteria could also be genetically engineered to better enhance bee health. Synthetic biologists have engineered probiotic bacteria to perform additional functions and express new traits, and these engineered probiotics represent the newest frontier for manipulating microbiomes. Because bee gut bacteria can be grown in the laboratory and genetically manipulated, researchers have begun to create and test engineered probiotics [84–86]. Engineered bee probiotics could be enhanced to perform a new function (degradation of pesticides or other harmful xenobiotic compounds), gain resistance to a specific stressor (resistance to pesticides), or even manipulate bee behaviour and immunity. Engineered strains would then be reintroduced into honeybees and hives where they would coexist with natural strains and perform their desired function. This approach mirrors recent efforts to engineer the human microbiome by modifying commensal bacteria from human guts to fight pathogens and treat disease [87–89], and similar efforts are underway to modify gut communities associated with other insects [90], plants and other animals [91].

While microbiome engineering to improve bee health remains in its infancy, a recent study demonstrated the feasibility of this approach [92]. In this study, researchers engineered the symbiotic bee gut bacterium S. alvi to express double-stranded RNA in the gut of honeybees which then triggers the bee RNA-interference immune response. In laboratory experiments, this approach successfully altered bee gene expression and limited damage from deformed wing virus and Varroa mites.

The feasibility and effectiveness of the approach has not been tested under field conditions, and it is not yet known if engineered strains would persist in an actual hive, and whether genetic constructs would stably function or need to be periodically reintroduced. Another unknown is how engineered strains might affect the natural ecosystem and bacterial community in bees. Appropriate risk assessments would be required to assess potential for negative impact. While no engineered bacteria have been used in bumblebees or other social bees, similar approaches to those used in honeybees are plausible.

6. Future prospects for honeybee probiotics

Despite efforts to develop honeybee probiotics, no probiotic formulations have been demonstrated to be reliably effective in honeybees. Currently available probiotic formulations for bees include strains of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium used in fermenting dairy products and incorporated into human probiotic formulations; these are foreign to bee guts. Results presented here, and general surveys of bee gut microbiota, indicate that these bacteria do not establish to high titers or persist in bee guts. Even Apilactobacillus strains that are associated with diverse bees, honey or nectar, may not stably colonize guts of Apis or Bombus species. Potentially, probiotics can provide benefits without establishing in hosts, but robust evidence is not available. Ingesting substantial quantities of live bacteria that do not occur naturally in hosts has the potential to do harm, so rigorous experiments that evaluate effects are needed.

We found that naturally occurring strains of bee gut bacteria can be administered as a defined community to bees where they re-establish and persist, whereas a commercial probiotic formulation composed of non-native bacteria does not establish in bee hosts (figure 2). Furthermore, the communities established by native strains resemble natural bee gut communities in composition and in their activation of bee genes related to immunity and development (figure 3). These results are consistent with preliminary trials showing that the administration of natural isolates can restore microbiota disrupted by antibiotics and can defend against infection by opportunistic bacterial pathogens [31,70]. Although promising, establishment does not imply efficacy in promoting host health, and the benefits of native bee gut strains remain untested at the hive level. The use of natural gut isolate strains would also require methods to grow these bacteria at scale, combine them into communities and deliver them to hives. Since even closely related strains may vary in their metabolic capabilities, and related bee gut strains vary in responses to chemical stressors such as antibiotics and glyphosate, it also would be useful to identify the specific strains that maximize benefits to bees.

Though some questions are unanswered, the future of probiotics for honeybees is bright. It may be possible to design specific communities of natural gut isolates that stably replenish gut communities disrupted by the many stressors bees face and that are economical and efficient for use in apiaries.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kim Hammond for her work on figure 1 and for assistance in management of bee hives used in experiments.

Data accessibility

Data for figures 2 and 3 are provided in the electronic supplementary material [93].

Authors' contributions

J.E.P. and E.V.S.M. performed experimental work, all authors contributed to writing. All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Competing interests

S.P.L., J.E.P., and N.A.M. are authors on a United States patent application involving use of native bee gut bacteria as probiotics to improve bee health.

Funding

This work was supported by the United States Department of Agriculture, National Institute for Food and Agriculture (award no. 2017-06473) and the US National Institutes of Health (award no. R35GM131738).

References

- 1.Cunningham M, et al. 2021. Shaping the future of probiotics and prebiotics. Trends Microbiol. 29, 667-685. ( 10.1016/j.tim.2021.01.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engel P, et al. 2016. The bee microbiome: impact on bee health and model for evolution and ecology of host-microbe Interactions. mBio 7, e02164-15. ( 10.1128/mBio.02164-15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng H, Steele MI, Leonard SP, Motta EVS, Moran NA. 2018. Honey bees as models for gut microbiota research. Lab. Anim. 47, 317-325. ( 10.1038/s41684-018-0173-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romero S, Nastasa A, Chapman A, Kwong WK, Foster LJ. 2019. The honey bee gut microbiota: strategies for study and characterization. Insect Mol. Biol. 28, 455-472. ( 10.1111/imb.12567) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwong WK, Moran NA. 2016. Gut microbial communities of social bees. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 374-384. ( 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.43) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwong WK, Medina LA, Koch H, Sing KW, Soh EJY, Ascher JS, Jaffé R, Moran NA. 2017. Dynamic microbiome evolution in social bees. Sci. Adv. 3, e1600513. ( 10.1126/sciadv.1600513) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerqueira AES, Hammer TJ, Moran NA, Santana WC, Kasuya MCM, da Silva CC. 2021. Extinction of anciently associated gut bacterial symbionts in a clade of stingless bees. ISME J. 9, 2813-2816. ( 10.1038/s41396-021-01000-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powell JE, Martinson VG, Urban-Mead K, Moran NA. 2014. Routes of acquisition of the gut microbiota of the honey bee Apis mellifera. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 7378-7387. ( 10.1128/AEM.01861-14) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinson VG, Moy J, Moran NA. 2012. Establishment of characteristic gut bacteria during development of the honeybee worker. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 2830-2840. ( 10.1128/AEM.07810-11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu Y, Zheng Y, Chen Y, Chen G, Zheng H, Hu F. 2020. Apis cerana gut microbiota contribute to host health though stimulating host immune system and strengthening host resistance to Nosema ceranae. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7, 192100. ( 10.1098/rsos.192100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horak RD, Leonard SP, Moran NA. 2020. Symbionts shape host innate immunity in honeybees. Proc. R. Soc. B 287, 20201184. ( 10.1098/rspb.2020.1184) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng H, Perreau J, Powell JE, Han B, Zhang Z, Kwong WK, Tringe SG, Moran NA. 2019. Division of labor in honey bee gut microbiota for plant polysaccharide digestion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 25 909-25 916. ( 10.1073/pnas.1916224116) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kešnerová L, Mars RAT, Ellegaard KM, Troilo M, Sauer U, Engel P. 2017. Disentangling metabolic functions of bacteria in the honey bee gut. PLoS Biol. 15, e2003467. ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.2003467) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng H, Nishida A, Kwong WK, Koch H, Engel P, Steele MI, Moran NA. 2016. Metabolism of toxic sugars by strains of the bee gut symbiont Gilliamella apicola. mBio 7, e0132616. ( 10.1128/mBio.01326-16) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng H, Powell JE, Steele MI, Dietrich C, Moran NA. 2017. Honeybee gut microbiota promotes host weight gain via bacterial metabolism and hormonal signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 4775-4780. ( 10.1073/pnas.1701819114) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu Y, Zheng Y, Chen Y, Wang S, Chen Y, Hu F, Zheng H. 2020. Honey bee (Apis mellifera) gut microbiota promotes host endogenous detoxification capability via regulation of P450 gene expression in the digestive tract. Microb. Biotechnol. 13, 1201-1212. ( 10.1111/1751-7915.13579) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raymann K, Motta EVS, Girard C, Riddington IM, Dinser JA, Moran NA. 2018. Imidacloprid decreases honey bee survival rates but does not affect the gut microbiome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84, e0054518. ( 10.1128/AEM.00545-18) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothman JA, Leger L, Graystock P, Russell K, McFrederick QS. 2019. The bumble bee microbiome increases survival of bees exposed to selenate toxicity. Environ. Microbiol. 21, 3417-3429. ( 10.1111/1462-2920.14641) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koch H, Schmid-Hempel P. 2011. Socially transmitted gut microbiota protect bumble bees against an intestinal parasite. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 19 288-19 292. ( 10.1073/pnas.1110474108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koch H, Schmid-Hempel P. 2012. Gut microbiota instead of host genotype drive the specificity in the interaction of a natural host-parasite system. Ecol. Lett. 15, 1095-1103. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01831.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mockler BK, Kwong WK, Moran NA, Koch H. 2018. Microbiome structure influences infection by the parasite Crithidia bombi in bumble bees. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84, e02335-17. ( 10.1128/AEM.02335-17) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawley TD, Walker AW. 2013. Intestinal colonization resistance. Immunology 138, 1-11. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2012.03616.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwong WK, Mancenido AL, Moran NA. 2017. Immune system stimulation by the native gut microbiota of honey bees. R. Soc. Open Sci. 4, 170003. ( 10.1098/rsos.170003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Näpflin K, Schmid-Hempel P. 2016. Immune response and gut microbial community structure in bumblebees after microbiota transplants. Proc. R. Soc. B 283, 20160312. ( 10.1098/rspb.2016.0312) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steele MI, Kwong WK, Whiteley M, Moran NA. 2017. Diversification of Type VI secretion system toxins reveals ancient antagonism among bee gut microbes. mBio 8, e0163017. ( 10.1128/mBio.01630-17) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson KE, Ricigliano V, Anderson KE, Ricigliano VA. 2017. Honey bee gut dysbiosis : a novel context of disease ecology. Curr. Opin. Ins. Sci. 22, 125-132. ( 10.1016/j.cois.2017.05.020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cariveau DP, Elijah Powell J, Koch H, Winfree R, Moran NA. 2014. Variation in gut microbial communities and its association with pathogen infection in wild bumble bees (Bombus). ISME J. 8, 2369-2379. ( 10.1038/ismej.2014.68) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Motta EVS, Mak M, De Jong TK, Powell JE.. 2020. Oral or topical exposure to glyphosate in herbicide formulation impacts the gut microbiota and survival rates of honey bees. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 86, e01150-20. ( 10.1128/AEM.01150-20) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raymann K, Shaffer Z, Moran NA. 2017. Antibiotic exposure perturbs the gut microbiota and elevates mortality in honeybees. PLoS Biol. 15, e2001861. ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.2001861) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Motta EVS, Moran NA. 2020. Impact of glyphosate on the honey bee gut microbiota: effects of intensity, duration, and timing of exposure. mSystems 5, e00268-20. ( 10.1128/mSystems.00268-20) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Powell JE, Carver Z, Leonard SP, Moran NA. 2021. Field-realistic tylosin exposure impacts honey bee microbiota and pathogen susceptibility, which Is ameliorated by native gut probiotics. Microbiol. Spectr. 9, e0010321. ( 10.1128/Spectrum.00103-21) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tarpy DR, Mattila HR, Newton ILG. 2015. Development of the honey bee gut microbiome throughout the queen-rearing process. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 3182-3191. ( 10.1128/AEM.00307-15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kapheim KM, Rao VD, Yeoman CJ, Wilson BA, White BA, Goldenfeld N, Robinson GE. 2015. Caste-specific differences in hindgut microbial communities of honey bees (Apis mellifera). PLoS ONE 10, e0123911. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0123911) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Powell JE, Eiri D, Moran NA, Rangel J. 2018. Modulation of the honey bee queen microbiota: effects of early social contact. PLoS ONE 13, e0200527. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0200527) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L, et al. 2019. Dynamic changes of gut microbial communities of bumble bee queens through important life stages. mSystems 4, e0063119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corby-Harris V, Snyder LA, Schwan MR, Maes P, McFrederick QS, Anderson KE. 2014. Origin and effect of Alpha 2.2 Acetobacteraceae in honey bee larvae and description of Parasaccharibacter apium gen. nov., sp. nov. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 7460-7472. ( 10.1128/aem.02043-14) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinson VG, Danforth BN, Minckley RL, Rueppell O, Tingek S, Moran NA. 2011. A simple and distinctive microbiota associated with honey bees and bumble bees. Mol. Ecol. 20, 619-628. ( 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04959.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Babendreier D, Joller D, Romeis J, Bigler F, Widmer F. 2007. Bacterial community structures in honeybee intestines and their response to two insecticidal proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 59, 600-610. ( 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00249.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vojvodic S, Rehan SM, Anderson KE. 2013. Microbial gut diversity of Africanized and European honey bee larval instars. PLoS ONE 8, e72106. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0072106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yun JH, Lee JY, Hyun DW, Jung MJ, Bae JW. 2017. Bombella apis sp. nov., an acetic acid bacterium isolated from the midgut of a honey bee. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 67, 2184-2188. ( 10.1099/ijsem.0.001921) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evans JD, Schwarz RS. 2011. Bees brought to their knees: microbes affecting honey bee health. Trends Microbiol. 19, 614-620. ( 10.1016/j.tim.2011.09.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beaurepaire A, et al. 2020. Diversity and global distribution of viruses of the western honey bee, Apis mellifera. Insects 11, 239. ( 10.3390/insects11040239) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Genersch E. 2010. American foulbrood in honeybees and its causative agent, Paenibacillus larvae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 103(Suppl. 1), S10-S19. ( 10.1016/j.jip.2009.06.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grupe AC II, Quandt CA. 2020. A growing pandemic: a review of Nosema parasites in globally distributed domesticated and native bees. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008580. ( 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008580) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwarz RS, Bauchan GR, Murphy CA, Ravoet J, de Graaf DC, Evans JD.. 2015. Characterization of two species of Trypanosomatidae from the honey bee Apis mellifera: Crithidia mellificae Langridge and McGhee, and Lotmaria passim n. gen., n. sp. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 62, 567-583. ( 10.1111/jeu.12209) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aronstein KA, Murray KD. 2010. Chalkbrood disease in honey bees. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 103(Suppl 1), S20-S29. ( 10.1016/j.jip.2009.06.018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raymann K, Coon KL, Shaffer Z, Salisbury S, Moran NA. 2018. Pathogenicity of Serratia marcescens strains in honey bees. mBio 9, e0164918. ( 10.1128/mBio.01649-18) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burritt NL, Foss NJ, Neeno-Eckwall EC, Church JO, Hilger AM, Hildebrand JA, Warshauer DM, Perna NT, Burritt JB. 2016. Sepsis and hemocyte loss in honey bees (Apis mellifera) infected with Serratia marcescens strain Sicaria. PLoS ONE 11, e0167752. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0167752) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raymann K, Bobay LM, Moran NA. 2018. Antibiotics reduce genetic diversity of core species in the honeybee gut microbiome. Mol. Ecol. 27, 2057-2066. ( 10.1111/mec.14434) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Motta EVS, Raymann K, Moran NA. 2018. Glyphosate perturbs the gut microbiota of honey bees. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 10 305-10 310. ( 10.1073/pnas.1803880115) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saelao P, Borba RS, Ricigliano V, Spivak M, Simone-Finstrom M. 2020. Honeybee microbiome is stabilized in the presence of propolis. Biol. Lett. 16, 20200003. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2020.0003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palmer-Young EC, Ngor L, Burciaga Nevarez R, Rothman JA, Raffel TR, McFrederick QS. 2019. Temperature dependence of parasitic infection and gut bacterial communities in bumble bees. Environ. Microbiol. 21, 4706-4723. ( 10.1111/1462-2920.14805) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hammer TJ, Le E, Moran NA.. 2021. Thermal niches of specialized gut symbionts: the case of social bees. Proc. R. Soc. B 288, 20201480. ( 10.1098/rspb.2020.1480) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li JH, Evans JD, Li WF, Zhao YZ, DeGrandi-Hoffman G, Huang SK, Li ZG, Hamilton M, Chen YP. 2017. New evidence showing that the destruction of gut bacteria by antibiotic treatment could increase the honey bee's vulnerability to Nosema infection. PLoS ONE 12, e0187505. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0187505) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li J, Powell JE, Guo J, Evans JD, Wu J, Williams P, Lin Q, Moran NA, Zhang Z. 2015. Two gut community enterotypes recur in diverse bumblebee species. Curr. Biol. 25, R652-R653. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.031) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suez J, Zmora N, Segal E, Elinav E. 2019. The pros, cons, and many unknowns of probiotics. Nat. Med. 25, 716-729. ( 10.1038/s41591-019-0439-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chmiel JA, Pitek AP, Burton JP, Thompson GJ, Reid G. 2021. Meta-analysis on the effect of bacterial interventions on honey bee productivity and the treatment of infection. Apidologie 52, 960-972. ( 10.1007/s13592-021-00879-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.DeFilipp Z, et al. 2019. Drug-resistant E. coli bacteremia transmitted by fecal microbiota transplant. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 2043-2050. ( 10.1056/NEJMoa1910437) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Corby-Harris V, Snyder L, Meador CAD, Naldo R, Mott B, Anderson KE. 2016. Parasaccharibacter apium, gen. nov., sp. nov., improves honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) resistance to Nosema. J. Econ. Entomol. 109, 537-543. ( 10.1093/jee/tow012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Floyd AS, Mott BM, Maes P, Copeland DC, McFrederick QS, Anderson KE. 2020. Microbial ecology of European foul brood disease in the honey bee (Apis mellifera): towards a microbiome understanding of disease susceptibility. Insects 11, 555. ( 10.3390/insects11090555) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miller DL, Smith EA, Newton ILG. 2021. A bacterial symbiont protects honey bees from fungal disease. mBio 12, e0050321. ( 10.1128/mBio.00503-21) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Daisley BA, Pitek AP, Chmiel JA, Al KF, Chernyshova AM, Faragalla KM, Burton JP, Thompson GJ, Reid G.. 2020. Novel probiotic approach to counter Paenibacillus larvae infection in honey bees. ISME J. 14, 476-491. ( 10.1038/s41396-019-0541-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stephan JG, Lamei S, Pettis JS, Riesbeck K, de Miranda JR, Forsgren E.. 2019. Honeybee-specific lactic acid bacterium supplements have no effect on American foulbrood-infected honeybee colonies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 85, e0060619. ( 10.1128/AEM.00606-19) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rangel J, Tarpy DR. 2016. In-hive miticides and their effect on queen supersedure and colony growth in the honey bee (Apis mellifera). J. Environ. Anal. Toxicol. 6, 2161-0525. ( 10.4172/2161-0525.1000377) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chmiel JA, Daisley BA, Pitek AP, Thompson GJ, Reid G. 2020. Understanding the effects of sublethal pesticide exposure on honey bees: a role for probiotics as mediators of environmental stress. Front. Ecol. Evol. 8, 22. ( 10.3389/fevo.2020.00022) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Audisio MC, Sabaté DC, Benítez-Ahrendts MR. 2015. Effect of Lactobacillus johnsonii CRL1647 on different parameters of honeybee colonies and bacterial populations of the bee gut. Beneficial Microbes 6, 687-695. ( 10.3920/BM2014.0155) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.vanEngelsdorp D, et al. 2009. Colony collapse disorder: a descriptive study. PLoS ONE 4, e6481. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0006481) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Evans JD, Spivak M. 2010. Socialized medicine: individual and communal disease barriers in honey bees. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 103(Suppl. 1), S62-S72. ( 10.1016/j.jip.2009.06.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Baracchi D, Fadda A, Turillazzi S. 2012. Evidence for antiseptic behaviour towards sick adult bees in honey bee colonies. J. Insect Physiol. 58, 1589-1596. ( 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2012.09.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Steele MI, Motta EVS, Gattu T, Martinez D, Moran NA. 2021. The gut microbiota protects bees from invasion by a bacterial pathogen. Microbiol. Spectr. 9, e0039421. ( 10.1128/Spectrum.00394-21) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Borges D, Guzman-Novoa E, Goodwin PH. 2021. Effects of prebiotics and probiotics on honey bees (Apis mellifera) infected with the microsporidian parasite Nosema ceranae. Microorganisms 9, 481. ( 10.3390/microorganisms9030481) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tejerina MR, Benítez-Ahrendts MR, Audisio MC. 2020. Lactobacillus salivarius A3iob reduces the incidence of Varroa destructor and Nosema spp. in commercial apiaries located in the northwest of Argentina. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 12, 1360-1369. ( 10.1007/s12602-020-09638-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Daisley BA, et al. 2020. Lactobacillus spp. attenuate antibiotic-induced immune and microbiota dysregulation in honey bees. Commun. Biol. 3, 534. ( 10.1038/s42003-020-01259-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Paris L, Peghaire E, Moné A, Diogon M, Debroas D, Delbac F, El Alaoui H. 2020. Honeybee gut microbiota dysbiosis in pesticide/parasite co-exposures is mainly induced by Nosema ceranae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 172, 107348. ( 10.1016/j.jip.2020.107348) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rubanov A, Russell KA, Rothman JA, Nieh JC, McFrederick QS. 2019. Intensity of Nosema ceranae infection is associated with specific honey bee gut bacteria and weakly associated with gut microbiome structure. Sci. Rep. 9, 3820. ( 10.1038/s41598-019-40347-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huang SK, et al. 2018. Influence of feeding type and Nosema ceranae infection on the gut microbiota of Apis cerana workers. mSystems 3, e00177-18. ( 10.1128/mSystems.00177-18) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Arredondo D, Castelli L, Porrini MP, Garrido PM, Eguaras MJ, Zunino P, Antúnez K. 2018. Lactobacillus kunkeei strains decreased the infection by honey bee pathogens Paenibacillus larvae and Nosema ceranae. Beneficial Microbes 9, 279-290. ( 10.3920/BM2017.0075) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.El Khoury S, et al. 2018. Deleterious interaction between honeybees (Apis mellifera) and its microsporidian intracellular parasite Nosema ceranae was mitigated by administrating either endogenous or allochthonous gut microbiota strains. Front. Ecol. Evol. 6, e58. ( 10.3389/fevo.2018.00058) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Klassen SS, VanBlyderveen W, Eccles L, Kelly PG, Borges D, Goodwin PH, Petukhova T, Wang Q, Guzman-Novoa E. 2021. Nosema ceranae infections in honey bees (Apis mellifera) treated with pre/probiotics and impacts on colonies in the field. Vet. Sci. China 8, 107. ( 10.3390/vetsci8060107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Andrearczyk S, Kadhim MJ, Knaga S. 2014. Influence of a probiotic on the mortality, sugar syrup ingestion and infection of honeybees with Nosema spp. under laboratory assessment. Med. Weter. 70, 762-765. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ptaszyńska AA, Borsuk G, Zdybicka-Barabas A, Cytryńska M, Małek W. 2016. Are commercial probiotics and prebiotics effective in the treatment and prevention of honeybee nosemosis C? Parasitol. Res. 115, 397-406. ( 10.1007/s00436-015-4761-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ptaszyńska AA, Borsuk G, Mułenko W, Wilk J. 2016. Impact of vertebrate probiotics on honeybee yeast microbiota and on the course of nosemosis. Med. Weter. 72, 430-434. ( 10.21521/mw.5534) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sabaté DC, Cruz MS, Benítez-Ahrendts MR, Audisio MC. 2012. Beneficial effects of Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis Mori2, a honey-associated strain, on honeybee colony performance. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 4, 39-46. ( 10.1007/s12602-011-9089-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Leonard SP, et al. 2018. Genetic engineering of bee gut microbiome bacteria with a toolkit for modular assembly of broad-host-range plasmids. ACS Synthetic Biol. 7, 1279-1290. ( 10.1021/acssynbio.7b00399) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rangberg A, Diep DB, Rudi K, Amdam GV. 2012. Paratransgenesis: an approach to improve colony health and molecular insight in honey bees (Apis mellifera)? Integr. Comp. Biol. 52, 89-99. ( 10.1093/icb/ics089) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rangberg A, Mathiesen G, Amdam GV, Diep DB. 2015. The paratransgenic potential of Lactobacillus kunkeei in the honey bee Apis mellifera. Beneficial Microbes 6, 513-523. ( 10.3920/bm2014.0115) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sonnenburg JL. 2015. Microbiome engineering. Nature 518, S10. ( 10.1038/518S10a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Isabella VM, et al. 2018. Development of a synthetic live bacterial therapeutic for the human metabolic disease phenylketonuria. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 857-864. ( 10.1038/nbt.4222) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Puurunen MK, et al. 2021. Safety and pharmacodynamics of an engineered E. coli Nissle for the treatment of phenylketonuria: a first-in-human phase 1/2a study. Nat. Metab. 3, 1125-1132. ( 10.1038/s42255-021-00430-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Elston KM, Leonard SP, Geng P, Bialik SB, Robinson E, Barrick JE. 2021. Engineering insects from the endosymbiont out. Trends Microbiol. 30, 79-96. ( 10.1016/j.tim.2021.05.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mueller UG, Sachs JL. 2015. Engineering microbiomes to improve plant and animal health. Trends Microbiol. 23, 606-617. ( 10.1016/j.tim.2015.07.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Leonard SP, et al. 2020. Engineered symbionts activate honey bee immunity and limit pathogens. Science 367, 573-576. ( 10.1126/science.aax9039) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Motta EVS, Powell JE, Leonard SP, Moran NA. 2022. Prospects for probiotics in social bees. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.5910619) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Motta EVS, Powell JE, Leonard SP, Moran NA. 2022. Prospects for probiotics in social bees. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.5910619) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

Data for figures 2 and 3 are provided in the electronic supplementary material [93].