Abstract

Objectives

Housing is a social determinant of health that impacts the health and well-being of children and families. Screening and referral to address social determinants of health in clinical and social service settings has been proposed to support families with housing problems. This study aims to identify housing screening questions asked of families in healthcare and social services, determine validated screening tools and extract information about recommendations for action after screening for housing issues.

Methods

The electronic databases MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Ovid Emcare, Scopus and CINAHL were searched from 2009 to 2021. Inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed literature that included questions about housing being asked of children or young people aged 0–18 years and their families accessing any healthcare or social service. We extracted data on the housing questions asked, source of housing questions, validity and descriptions of actions to address housing issues.

Results

Forty-nine peer-reviewed papers met the inclusion criteria. The housing questions in social screening tools vary widely. There are no standard housing-related questions that clinical and social service providers ask families. Fourteen screening tools were validated. An action was embedded as part of social screening activities in 27 of 42 studies. Actions for identified housing problems included provision of a community-based or clinic-based resource guide, and social prescribing included referral to a social worker, care coordinator or care navigation service, community health worker, social service agency, referral to a housing and child welfare demonstration project or provided intensive case management and wraparound services.

Conclusion

This review provides a catalogue of housing questions that can be asked of families in the clinical and/or social service setting, and potential subsequent actions.

Keywords: paediatrics, social medicine, community child health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The first systematic review to catalogue housing questions asked of families in clinical and social service settings, including information on validity of screening tools.

Independent review of study selection, quality assessment and data extraction.

Search terms may have been too narrow and may not have captured relevant papers that included information on housing questions in broader social screening tools.

The quality of studies varied across the studies.

Heterogeneity in study design, sample size, participant age, housing questions asked across studies, limiting ability to compare studies.

Introduction

Social determinants of health are the environments and conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live and age.1 The role of housing as a social determinant of health is well-established.2 3 Healthy housing is described by WHO as ‘shelter that supports a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being’ and ‘provides a feeling of home, including a sense of belonging, security and privacy’.3 Adequate housing is more than shelter and provision of quality physical dwelling conditions.4–6 Housing tenure and housing affordability are important factors in supporting psychological and developmental well-being.6–11 Similar to other Western countries, in Australia, where this review was conducted, almost 1 million people reside in housing considered to be in poor condition and there is an over-representation of young people, people in low-income households and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in poor housing conditions.12

There is growing evidence that housing aspects such as housing quality and environments materially affect health, well-being and developmental trajectories well into adulthood.13–16 Housing issues in childhood have a particularly detrimental effect on health and well-being. Poor housing conditions in childhood have been predicted to lead to poorer health and increased mortality later in life, after controlling for the confounding effect of socioeconomic conditions.13 14 Material and social factors that impact on children’s well-being include poor physical housing quality (mould and damp, utilities, toxicants, disrepair, lack of heating, injury hazards), crowding, lack of outdoor space for children to play, accessibility within the home, housing affordability, tenure type, frequent residential moves, homelessness, lack of cultural appropriateness and complex neighbourhood quality.6 16–23 Psychological and emotional distress, as well as behavioural problems, have been independently associated with children living in poor housing conditions and experiencing housing instability.20 24–29 Housing instability, frequent moving and homelessness also negatively affect children’s health30 and children’s educational outcomes.31 A range of physical health issues such as asthma, acute respiratory symptoms and low birth weight have been independently associated with damp and mouldy housing,22 32 33 and living in crowded conditions has been found to lead to infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, meningococcal disease, acute rheumatic fever and otitis media and gastrointestinal infections in New Zealand and Australia.34–41 Multiple forms of housing problems can coexist and have a compounded, cumulative impact on physical and mental health, particularly after prolonged exposure during childhood.11 42

Improving the quality of housing and the immediate environment around the home ‘can save lives, prevent disease and increase quality of life’.3 There is evidence to support screening and social prescribing for social determinants in healthcare, including housing issues, to address basic resource needs, inequity and improve child health.29 43–50 Screening involves incorporating standardised tools, such as surveys or questionnaires, completed with families in paediatric or primary care practices.51 52 Social prescribing, sometimes known as community referral, is a mechanism for clinicians to link or refer patients to non-medical sources of support, such as to the community sector, to address social determinants of health and improve community well-being.49 53–56 Social prescribing has been recognised as a pathway to ‘address physiological, physical, psychological, psychosocial or socioeconomic issues, as well as enhancing community well-being and social inclusion’.55 There is evidence to show that caregivers in the paediatric healthcare setting are interested in assistance if screening positively to housing instability.57 Screening for housing issues has been demonstrated to increase the occurrence of social prescribing. Screening increases referral of families to appropriate professionals or providing families with resources,58 59 and can lead to improved child health.44 While many social screening tools addressing housing issues do exist,60 61 to date there are no widely accepted guidelines for health and social service professionals to systematically identify specific housing problems for children and address them.29 59 62 The aims of this systematic review were to catalogue housing screening questions asked of families in healthcare and social service settings, as described in the international literature; determine if any validated screening tools exist; and extract information about any recommendations for action after screening described in the literature, including social prescribing such as referral through health, housing and social care pathways.

Findings from this review will inform the development of an integrated detection, referral and action pathway to be used in healthcare and social service settings with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and families who may be experiencing poor health due to housing problems in Australia. The detection, referral and action pathway will also be used with non-Aboriginal patients and clients who are experiencing housing-related health issues.

Methods

Search strategy

A study protocol was developed, registered with the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (PROSPERO) and updated on 28 April 2020, registration number CRD42020159816 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/). A search of the international peer-reviewed and grey literature was conducted using the following inclusion criteria: studies that include questions about housing being asked of the population group, children or young people aged 0–18 years and their families, accessing any health or social service. There were no restrictions on study type, design or method, and studies were not limited by country. Studies were limited to the English language and to published literature in the 10-year period 1 January 2009 to 14 December 2021. Studies about health assessment conducted with clients of housing services were excluded. Review papers were excluded.

The electronic databases MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Ovid Emcare, Scopus and CINAHL from 2009 to 2021 inclusive were systematically searched. The search strategy and key search terms are included in online supplemental table 1, in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. A secondary search of citations from bibliographies of related peer-reviewed articles, and an additional search of the grey literature using the search terms ‘social needs screening tool’; ‘housing screening tool for children’ in Google Scholar were undertaken.

bmjopen-2021-054338supp001.pdf (93.7KB, pdf)

All study titles and abstracts were reviewed independently in Covidence by two reviewers, this task was shared across six reviewers (NW, JA, SW, MA, KH and CKS). Disagreements about inclusion of studies were discussed and decisions made by consensus with four authors (JA, SW, MA and KH). Full texts of papers were reviewed independently by three reviewers (JA, SW and KH). Divergences were discussed with three reviewers (JA, SW and KH) and agreement reached.

Data extraction and analysis

Data were extracted from included papers using a standardised data extraction tool by three reviewers (JA, SW and CKS). The data extracted included specific details about the study types, aims and methods, populations, screening tools, housing questions, descriptions of actions, such as referral to appropriate services, to address housing issues and other items pertaining to the review question and specific objectives. If housing questions were not available in the papers, but the name of a screening tool was provided, the authors accessed the specific tool through a web search to extract the housing screening questions. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion.

Quality assessment

Three reviewers (JA, KH and SW) assessed the quality of each study using two separate tools, dependent on study type. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) tool63 was used to appraise quantitative randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quantitative non-randomised trials, quantitative descriptive and mixed methods studies. Quality improvement (QI) studies were appraised using the QI Minimum Quality Criteria Set (QI-MQCS) V.1.0.64 The reviewers did not give studies an overall score for methodological quality, as it is discouraged to calculate an overall quality score using the MMAT tool.63 Consensus on quality was reached through discussion.

Patient and public involvement

This study was conceptualised, in part, with community members who have experienced housing issues, and people who are in regular patient contact with families experiencing housing issues impacting on health and well-being.

Results

Papers identified

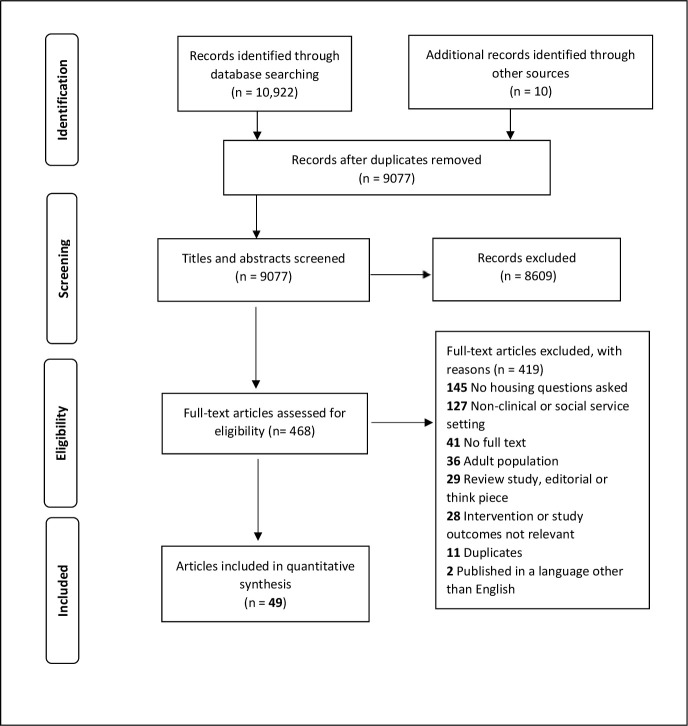

The search strategy identified 10 922 titles (excluding duplicates) and an additional 10 papers were found through a grey literature search and through citations. A total of 9077 titles and abstracts were screened, and 8609 of these were excluded, as these titles and abstracts did not provide any information that led screeners to believe that the full-text papers would have questions about housing being asked of people aged 0–18 years and their families accessing healthcare or social services. Four hundred sixty-eight full-text papers were identified as potentially meeting inclusion criteria and were assessed for eligibility, and 419 were excluded. Reasons for exclusion are provided in figure 1. The two most common reasons for exclusion were that housing questions were being asked outside of a clinical or social service setting (n=127) and there were no questions about housing being asked (n=145). A total of 49 papers were included representing 42 studies.

Figure 1.

Search flow chart.

Included papers

The 49 included papers are listed in table 1. All papers were published in peer-reviewed journals. Studies were primarily conducted in clinical settings (n=39); paediatric primary care clinics, children’s hospitals and emergency departments, urban community health centres, general paediatric centres, ambulatory healthcare practices and antenatal clinics. Three studies were conducted in social service settings including a disability service, a government child welfare unit and a government-funded housing and health support service. All studies were based in high-income countries, with 39 studies conducted in the USA, 1 study in Australia, 1 in New Zealand and 1 study conducted in Spain.

Table 1.

Included study characteristics

| Study | Country | Study type | Participants (age) | Sample size | Name of tool and source of housing questions | Validity, feasibility and/or acceptability of tool | Housing questions (if available) |

| Arbour et al 94 | USA | Quality improvement | Newborns and their families | 692 | Not provided | Used validated, standardised screening questions | Housing instability; unhealthy housing. |

| Badia et al 99 | Spain | Quantitative—tool translation, adaptation, validation | Parents of children and adolescents with cerebral palsy (8–18 years) | 221 | European Child Environment Questionnaire, based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health | Construct validity, translation, adaptation and validation of tool conducted specifically for the Spanish context | Enlarged rooms at home (need/availability?); adapted toilet at home (need/availability?); modified kitchen at home (need/availability?); walking aids (need/availability?); hoists at home (need/availability?) |

| Beck et al 100 | USA | Quantitative—retrospective review | Newborns and families (age not specified) | 639 | Developed based on literature review, in consultation with medical staff, social services and medical-legal staff and adapted from the USA’s Survey on Income and Program Participation | Food security and domestic violence questions validated; housing questions not validated | “[Are you having] Problems with housing conditions (overcrowding, evictions, lead, utilities, mold, rodents)? Have you spoken with your landlord?” |

| Bottino et al 65 | USA | Quantitative—cross-sectional | Children (3–10 years) | 340 | Adapted from the American Housing Survey | Food questions validated; no information on housing question validity | “What best describes your current living situation?” (Rent apartment; rent room(s) within another person’s home; own home; homeless or living in a shelter; doubled up with another family; live with parents/other family; other). Selecting ‘rent apartment’ or ‘own home’ triggered a follow-up item: “In the last 12 months, has the electric or gas company shut off the electricity or gas in your home or threatened to shut off the utilities in your home?” and “Are you concerned about a possible eviction (being ‘kicked out’ from your home?” |

| Bovell-Ammon et al 84 | USA | Quantitative—RCT | Medically complex families with children under 11 years of age | 78 | No information provided | No information provided | Experience of one or more adverse housing circumstances: homelessness in previous year, having moved two or more times in previous year (multiple moves), behind on rent in the previous year and paying >50% of family income on rent. |

| Colvin et al 59 | USA | Quantitative—postintervention only design | Children (median age 3 years) | 45 | Income, Housing, Education, Legal status, Language/Immigration, Personal Safety (IHELLP), IHELLP social history tool adapted from Kenyon et al 110 | Validity, sensitivity and specificity | “Do you have any concerns about poor housing conditions like mice, mold, cockroaches? Do you have any concerns about being evicted or not being able to pay the rent? Do you have any concerns about not being able to pay your mortgage?” |

| Costich et al 87 | USA | Quantitative—retrospective pre-post analysis | Caregivers of children (4–12 years) with special healthcare needs | 80 | US Department of Agriculture 18-item Household Food Security Survey and Food Insecurity screening tool by Hager et al 118 |

Sensitivity, specificity and convergent validity | “Is it hard for you to access any of the following: food, housing, medical care?” |

| De Marchis et al 72 | USA | Quantitative—cross-sectional | Adult caregivers of paediatric patients | 969 | See De Marchis et al 71 | See De Marchis et al 71 | See De Marchis et al. 71 |

| De Marchis et al 57 | USA | Quantitative—cross-sectional | Adult caregivers of paediatric patients | 1021 | See De Marchis et al 71 | See De Marchis et al 71 | See De Marchis et al. 71 |

| De Marchis et al 71 | USA | Quantitative—cross-sectional | Adult caregivers of paediatric patients | 835 | Accountable Health Communities (AHC) social risk screening tool and Children’s HealthWatch (CHW) Housing Stability Vital Sign questions | First two AHC housing questions adapted from the validated Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks and Experiences tool108; CHW questions validated119 | AHC: “Think about the place you live. Do you have problems with any of the following? (Check all that apply). Answers: (a) pests such as bugs, ants or mice; (b) mould; (c) lead paint or pipes; (d) lack of heat; (e) oven or stove not working; (f) smoke detectors missing or not working; (g) water leaks; (h) none of the above”; “What is your housing situation today? (a) I have a steady place to live; (b) I have a place to live today, but I am worried about losing it in the future; (c) I do not have a steady place to live (I am temporarily staying with others, in a hotel, in a shelter, living outside on the street, on a beach, in a car, abandoned building, bus or train station or in a park”. CHW: “In the past 12 months, was there a time when you were not able to pay the mortgage or rent on time?”; “In the past 12 months, how many times have you moved where you were living?”; “At any time in the past 12 months, were you homeless or living in shelter (including now)?” |

| Denny et al 91 | USA | Quality improvement | Children (0–1 years and 1–5 years) | 667 | Injury prevention (IP)+The Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) tool, IP tool adapted from Gittelman et al,120 and SEEK tool adapted from Dubowitz121 | IP tool tested for reliability | “Do you have trouble paying utilities or maintaining a safe place to live?”; “Do you use safety gates to protect your child at the top and bottom of all stairways in your house?”; “Are all potentially harmful household cleaners and pesticides either in locked storage OR out of the reach of children?”; “Is the hot water heater in your house adjusted to less than 120 degrees?” |

| Farrell et al 97 | USA | Quantitative—mixed methods population survey | Families with open child welfare cases | 6828 | Quick Risks and Assets for Family Triage (QRAFT), adapted from Risks and Assets for Family Triage assessment instrument | Some indication of content, construct and predictive validity, however inconclusive information | Current Housing, Housing Condition, and Housing History, with 5-item risk scale for each, measuring level of housing instability and homelessness. |

| Fiori et al 95 | USA | Quality improvement | Paediatric patients (37–144 months) | 7266 | Adapted from the Health Leads USA screening toolkit109 | Validity | Exact questions used were not provided. |

| Fiori et al 89 | USA | Quantitative—prospective pragmatic | Paediatric patients (2–13 years) | 4948 | Adapted from the Health Leads USA screening toolkit109 | Validity | Exact questions used were not provided. |

| Fiori et al 104 | USA | Quantitative | Children (0–17 years) | 15 503 | Adapted from the Health Leads USA screening toolkit109 | Validity | Exact questions used were not provided. |

| Garg et al 66 | USA | Quantitative—cross-sectional descriptive | Parents of children 2 months old to 10 years | 100 | Well Child Care, Evaluation, Community Resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education (WE CARE), developed collaboratively among paediatric clinic staff and initially guided by Bright Futures paediatric intake form29 | Face validity | “Do you think you are at risk of becoming homeless?” |

| Garg et al 43 | USA | Quantitative—cluster RCT | Families of infants <6 months old | 336 | WE CARE, adapted from a larger psychosocial screening instrument; three housing instability questions derived from the Children’s HealthWatch survey119 | Validity | Home heating and Housing instability (housing instability questions: having a steady place to sleep; household crowding, ie, >2 people per bedroom, or having moved >2 times in the past year). |

| Gottlieb et al 80 | USA | Quantitative—RCT | Caregivers of paediatric emergency department patients | 538 | Some items adapted from the Medical Advocacy Screening questionnaire; other items adapted from other existing validated surveys | Neighbourhood safety question validated | Concerns about the physical condition of your housing; concerns about the cost or stability of your housing; threats to your child’s safety at school or in the neighbourhood. |

| Gottlieb et al 44 | USA | Quantitative—RCT | Children (mean age 5 years) | 1809 | Used survey instrument from 2014 RCT | Neighbourhood safety question validated | Not having a place to live; unhealthy living environment; other concerns with housing. |

| Gottlieb et al 81 | USA | Quantitative—RCT | Children (mean age 5 years) and families in acute care setting | 718 | Used survey instrument from 2014 RCT | Neighbourhood safety question validated | Not having a place to live; unhealthy living environment; other concerns with housing. |

| Hardy et al 88 | USA | Quantitative—retrospective pre-post | Children and youth (0–21 years) | 56 253 | Social need domains informed by what are known to affect patients/families and selected based on the consensus of institutional stakeholders | No information provided | “Do you think you are at risk of becoming homeless?”; “Are you currently homeless?” |

| Hassan et al 67 | USA | Quantitative—cross-sectional | Young adult patients (15–25 years) | 401 | The Online Advocate, adapted from the American Housing Survey | Used previously validated survey questions | Major: homeless; utilities shut off; structural problems such as leaking roof, non-functional plumbing or rodent infestation. Minor: need fuel/heating assistance; threat of utilities shut off in past 12 months; if renting or receiving subsidised housing, concern about transfer or eviction. |

| Hassan et al 47 | USA | Quantitative—prospective intervention | Young adult patients (15–25 years) | 401 | The Online Advocate, adapted from the American Housing Survey | Used previously validated survey questions | Homeless; having utilities shut off; or having existing structural problems such as leaking roof, non-functional plumbing or rodent infestation. |

| Heller et al 73 | USA | Quantitative—cross-sectional | Children under 18 years, and adults | 24 633 | Tool derived from modified version of Health Leads screening toolkit109 and homegrown tool | Validity (Health Leads only) | “Are you worried that the place you are living now is making you sick? (has mold, bugs/rodents, water leaks, not enough heat)?”; “Are you worried that in the next 2 months, you may not have a safe or stable place to live? (eviction, being kicked out, homelessness)” |

| Hensley et al 92 | USA | Quality improvement | Paediatric patients and families | 114 | HealthBegins Upstream Risks Screening Tool | Feasibility | “In the last month, have you slept outside, in a shelter, or in a place not meant for sleeping? Y/N; In the last month, have you had concerns about the condition or quality of your housing? Y/N; In the last 12 months, how many times have you or your family moved from one home to another?” |

| Hershey et al 90 | USA | Quantitative—prospective | Caregivers of children and youth (4–18 years) with a diagnosis of T1D for >1 year and poor glycaemic control or high care utilisation | 53 | Health Leads USA questionnaire | Validity | “Are you worried that, in the next 2 months, you may not have stable housing?” |

| Higginbotham et al 93 | USA | Quality improvement | Children (1 week to 5 years old) | 53 | Aligned with US Department of Housing and Urban Development housing insecurity definition and previous cross-sectional study by Cutts et al 122 | Feasibility | Crowding ‘within the past 12 months there were two or more people per bedroom?‘; doubling up “within the past 12 months we were temporarily staying with another family or had another family staying with us?“; and frequent moving “within the past 12 months we moved more than once?” |

| Koita et al 98 | USA | Quantitative—validation of tool | Caregivers of children <12 years | 28 | BARC* Pediatric Adversity and Trauma Questionnaire, modified from Oakland Children’s Hospital Family Information and Navigation Desk needs assessment survey | Face validity | "Has your child/family ever been homeless? Has your child ever had problems with housing (for example not having a stable place to live, faced eviction or foreclosure, or lived with multiple families)?" |

| Kumar et al 82 | USA | Quantitative—RCT follow-up | Pregnant adolescents <17 years | 106 | Modified from the Treatment Services Review assessment tool | No information provided | Residential mobility (number of moves made in the year before prenatal survey, duration of stay, number of people living at their current home, and cohabitation with parents, husband or boyfriend and other relatives); need for housing resources at 3 months and 6 months post partum. |

| Matiz et al 101 | USA | Quantitative—retrospective chart review | Children with hearing loss (0.6–7.9 years) | 30 | No information provided | No information provided | “Is it hard for you to access any of the following: food, housing, medical care, N/A?” |

| Messmer et al 83 | USA | Quantitative—RCT | Parents of children with social needs | 414 | WE CARE | Validity | See WE CARE questions. |

| Molina et al 68 | USA | Quantitative—cross-sectional | Children and families | 276 | Adapted from health-related social needs questions from the National Academy of Medicine | No information provided | “In the last month, have you slept outside, in a shelter or in a place not meant for sleeping? In the last month, have you had concerns about the condition or quality of your housing? In the last 12 months, how many times have you or your family moved from one home to another? Are you worried that in the next 2 months, you may not have stable housing? In the past 12 months, have you had any utility (electric, gas, water or oil) shut off for not paying your bills? Do you have any concerns about safety in your neighbourhood? Are you afraid you might be hurt in your apartment building or house?” |

| Oldfield et al 74 | USA | Quantitative—cross-sectional | Parents of children of all ages, and adolescents (>13 years) | 154 | WE CARE tool and the AHC instrument | Validity (WE CARE); AHC housing questions adapted from the validated Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences tool108 | WE CARE: “Do you think you are at risk of becoming homeless?”; “Do you have trouble paying your heating bill and/or electricity bill?”; AHC: “What is your living situation today? (I have a steady place to live, I have a place to live today, but I am worried about losing it in the future, I do not have a steady place to live (I am temporarily staying with others, in a hotel, in a shelter, living outside on the street, on a beach, in a car, abandoned building, bus or train station, or in a park)”; “Think about the place you live. Do you have problems with any of the following? (pests, mold, lead paint or pipes, lack of heat, oven or stove not working, smoke detectors missing or not working, water leaks, none)” |

| Patel et al 85 | USA | Quantitative—pre-intervention and post-intervention intervention retrospective chart review | Patients at well-child visit (0–20 years) | 322 | IHELLP110 | No information provided | "Housing, utilities: What kind of housing do you live in (apartment, house)? Do you receive any type of housing subsidy (Section 8, public housing, shelter)? Do you have heat and hot water? Do you have trouble paying rent or utilities at the end of the month?” “Personal safety: Do you feel safe in your neighbourhood?” |

| Pierse et al 106 | New Zealand | Quantitative | Low-income families with children (0–14), hospitalised for health conditions attributable to home environment, and pregnant women with newborns | 895 | Housing Concerns Survey; developed in partnership with researchers to identify areas of housing need | No information provided | “Is your home usually colder than you would like?”; “During the winter months, was your house so cold that you shivered inside?”; “Does your home smell moldy or musty?”; “Is there mold on the walls in bedrooms or living areas of your home?”; “Are there damp walls in the bedrooms or living areas of your home?” |

| Polk et al 75 | USA | Quantitative—cross-sectional evaluation | Low-income families | 10 916 households | Health Leads universal social needs screener109 | Validity | “Would you like help with any of the following: finding housing search resources and emergency shelters?” |

| Power-Hays et al 96 | USA | Quality improvement | Families of children with sickle cell disease | 132 | WE CARE | Validity | “Do you currently live in a shelter or have no steady place to sleep at night?”; “Do you think you are at risk of becoming homeless? If yes, is this an emergency?“; “Would you like help connecting to resources? Housing/shelter”. |

| Ray et al | USA | Quantitative—observational | Caregivers accompanying a child (<5 years) who received a low-acuity triage score | 146 | WE CARE and Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks and Experiences (PRAPARE) | Validity | See WE CARE and PRAPARE questions. |

| Razani et al 77 | USA | Quantitative—observational | Adult caregivers of paediatric patients | 890 | 14-item social and mental health needs screening questionnaire44 | Neighbourhood safety question validated | ‘Not having a place to live, eg, concerns about eviction, foreclosure, staying with friends/family and current homelessness’; ‘Unhealthy living environments, eg, problems such as mould, insects, rats or mice, excess trash’; ‘Other concerns with your housing’. |

| Rhodes et al 69 | Australia | Quantitative—cross-sectional | Children (4–8 years) | 162 | Family Psychosocial Resources tool, adapted from the Family Resources Scale123 | No information provided | Basic living needs. |

| Sandel et al 30 | USA | Quantitative—cross-sectional | Caregivers of children (0–48 months of age) in renter households | 22 324 families | Not provided | Not tested | "During the last 12 months, was there a time when you were not able to pay the mortgage or rent on time?“; “In the past 12 months, how many places has the child lived?”; “What type of housing does the child live in?”; “Since the child was born, has she or he ever been homeless or lived in a shelter?” |

| Sandoval et al 102 | USA | Quantitative—retrospective chart review | Mother-child dyads | 268 | MAMA’s neighbourhood programme prenatal screening questionnaire; postnatal housing insecurity measured using Homelessness Screening Clinical Reminder Tool | No information provided | Exact questions used were not provided. |

| Selvaraj et al 70 | USA | Quantitative—cross-sectional | Children and adolescents (2 weeks to 17 years) | 2569 | Addressing Social Key Questions for Health Questionnaire (ASK tool), developed by staff of four academic institutions and literature review of validated paediatric questionnaires on adverse childhood experiences and unmet social needs | Validity and feasibility | Housing and bill insecurity; witnessed violence in the home or neighbourhood. |

| Semple-Hess et al 105 | USA | Quantitative—cross-sectional | English-speaking and Spanish-speaking caregivers | 768 | Questions developed through existing screening tools reported in literature and from paediatric and social worker’ knowledge of common needs of patients | Survey tested and refined | “Which of the following services have you/your child ever used?” and “In the next 12 months, which of the following services will you/your child need?” Housing options included: ‘(6) temporary housing and shelters; (7) safe housing services’. |

| Sokol et al (2021)107 | USA | Quantitative—evaluation | Outpatient paediatric patients (0–18 years) | 30 485 | Developed from PRAPARE108 | Housing question validity; no testing for referral question | “In the next 2 months, are you worried that you may not have stable housing?” For referral and resource support: “Do you want to be contacted by the assistance programme for help on any of your responses?” |

| Spencer76 | USA | Quantitative—cross-sectional | Caregivers of school-age children | 943 | WE CARE | Face and content validity | “Do you think you are at risk of becoming homeless?“; “Do you have trouble paying your heating bill for the winter?” |

| Uwemedimo and May103 | USA | Secondary data analysis | Caregivers of children <18 years | 148 | Family Wellness Screen (FAMNEEDS), developed from previously published Social Determinants of Health (SDH) screening tools124 | Validity | “Do you worry that in the next 2 months, you/your family may not have a safe or stable place to live? Y/N. Where is your child living now, Options provided: private house/apartment, room (in apartment/house), shelter, hotel/motel, no regular place, car, other. Do you worry that the place you're living now is making you sick? Y/N. If YES choose all that apply: Cigarette smoke, mold or dampness, rodents/bugs, peeling paint, broken appliances, open cracks/holes/wires, not enough heat, water leaks, none” Other questions: “Do you need help from a lawyer with housing, immigration, custody or child support problems? Y/N”. |

| Vaz et al 79 | USA | Quantitative—observational | Child-caregiver dyads | 249 | Social risk questionnaire based on the National Survey of Child Health, Children’s HealthWatch, social risk tools created by Gottlieb et al 80 and Harris et al 125 | Children’s HealthWatch questions validated119; Gottlieb neighbourhood safety questions validated80 | Exact questions used were not provided. |

| Zielinski et al 86 | USA | Quantitative—pre-post | Children | 602 | WE CARE tool29 | Validity, feasibility and acceptability | Housing insecurity. |

*Bay Area Research Consortium on Toxic Stress and Health.

RCT, randomised controlled trial; T1D, type 1 diabetes.

Studies were heterogenous in terms of method, design, sample size, age of participants, social screening tools and housing questions included in screening tools. Study types varied; cross-sectional,30 47 57 65–79 randomised controlled trials,43 44 80–84 pre and post studies,85–88 prospective,89 90 QI,59 91–96 mixed methods,97 98 tool adaptation and validation,99 retrospective100–102 and secondary data analysis.103 Sample sizes ranged from 45 to 56 253 participants. Participants were newborns, children, adolescents and/or their families or caregivers. Age ranges of children varied from study to study, and some studies only included children with specific characteristics, such as children with cerebral palsy, children with a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes, children with hearing loss and children with open child welfare cases. See table 1 for characteristics of included papers. An action, such a provision of a resource or a social prescribing activity was found in 27 of the 42 included studies, see table 2 for social prescribing for housing issues.

Table 2.

Social prescribing for housing issues

| Study | Screening tool name (if available) | Action as a result of screening | Referral rates and outcome (if available) |

| Arbour et al 94 | – | Provision of resource information for concrete supports. | 86% of families screening positively for general health-related social needs were provided resources information for concrete supports. |

| Bovell-Ammon et al 84 | – | Intervention group provided with intensive case management and wraparound services to meet specific needs, for example, support with housing search, eviction prevention, legal or financial services and if eligible, a public housing unit; control group provided with a list of resources detailing housing services available in the family’s community, as well as hospital-based social work and care navigation services. | Significant decreases between baseline and 6 months in homelessness (30.3% intervention vs 37.9% control) and multiple moves (2.9% intervention vs 7.1% control) at 6 months follow-up. Being behind on rent decreased significantly in the intervention group (29.4%) but not the control group (44.8%) at 6 months follow-up. Significant changes in child health status and parental anxiety among the intervention group compared with control group: at 6-month follow-up. |

| Colvin et al 59 | Income, Housing, Education, Legal status, Language/ Immigration, Personal Safety | Social work referral or resources provided to families who screened positively to unmet social needs. | 77.8% of families screening positively for unmet social needs were provided social work resources or referrals; 13.3% already had social needs addressed; <10% had an unmet social need but were unable to be connected with a resource or referral. |

| Costich et al 87 | – | Social service referral, goal setting and resource navigation on screening and participating in the Special Kids Achieving Their Everything Community Health Worker programme. | The number of caregivers reporting that it was hard to access housing was reduced from 23% to 9.5%. |

| Farrell et al 97 | Quick Risks and Assets for Family Triage | Assess eligibility to a housing and child welfare demonstration project, a supportive housing intervention, and for broader supportive housing referrals. Eligibility criteria: client scoring a 3 (significant risk) or 4 (severe risk) on any of the three housing items. | 5.4% of families scored 3 or 4 on housing items and on further assessment, 5.3% were referred to the housing and child welfare demonstration project. |

| Fiori et al 89; Fiori et al 95 | Adapted from Health Leads Screening Toolkit | For non-urgent issues: handoff with Community Health Worker who provides resources and schedule a follow-up. For urgent issues: referral to onsite social worker. | Not reported. |

| Garg et al 43 | Well Child Care, Evaluation, Community Resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education (WE CARE) | Referral made by clinician using the WE CARE Family Resource Book containing tear-out information sheets listing two to four free community resources available for each need. The information sheets contain the programme name, a brief description, contact information, programme hours and eligibility criteria. Follow-up 1 month after visit; staff telephoned mothers to assess contact of resources and update notes in the child’s medical record. | Mothers receiving WE CARE screening and referral had lower odds of being in a homeless shelter (aOR=0.2; 95% CI 0.1 to 0.9) and more mothers had enrolled in a new community resource at the 12-month visit (39% vs 24%; aOR=2.1; 95% CI 1.2 to 3.7) compared with families who did not receive WE CARE screening and referral. |

| Gottlieb et al 44; Gottlieb et al 81 | – | Caregivers who indicated at least one social need received either written information on relevant community resources (active control group) or received support from an in-person navigator immediately after the child’s visit and offered follow-up meetings (navigation intervention group). | Both groups showed improved child health after receiving either written information or an in-person navigator; child global health scores (lower scores indicate better health) improved a mean (SE) of −0.36 (0.05) in the navigator group and a mean (SE) of −0.12 (0.05) in the active control group. |

| Hardy et al 88 | – | A resource sheet on community resource linkages was provided if general social need identified. Any urgent social need received a social work consult. | Not reported. |

| Hassan et al 47; Hassan et al 67 | The Online Advocate | Resource specialist reviewed referrals; if questionnaire responses indicated acute concerns regarding homelessness, results were immediately shared with the provider and social worker to facilitate urgent intervention. | 75% of participants screened had at least one referral need; 27% required referral relating to housing problem and 14% received referral relating to housing problem; 85% of participants with housing problems reached for follow-up at 1 or 2 months, and 30% of those with housing problems selected that the problem was ‘completely’ or ‘mostly’ resolved. |

| Heller et al 73 | – | Providers offered to connect patients to clinic-based resources. | Not reported. |

| Hensley et al 92 | HealthBegins Upstream Risks Screening Tool | Patients with at-risk results were provided a community resources guide with an educational handout, in order to identify local agencies and programmes that addressed social needs. The guide listed supporting programmes or agencies, and included resource eligibility requirements, contact information. Patients were helped in contacting listed community resources. | Not reported. |

| Hershey et al 90 | Health Leads USA | Families asked if they would like assistance with any reported needs and if the need was urgent, and connected to community health worker. Goals were set with families with support from a community health worker. Housing related goals included: Access affordable housing or affordable home renovations; Help parent enrol in first-time homeowners’ programme; assist in negotiating rental arrears. | 41% of families requested assistance with housing; 16% of families selected goals relating to living situation. |

| Higginbotham et al 93 | – | Families screening positively for food insecurity and/or housing insecurity were provided a community resource guide to facilitate referral. | Of 13 families screening positive for food insecurity and/or housing insecurity, 85% were given a resource guide. |

| Matiz et al 101 | – | Referral to a community health worker. Community health workers supported caregivers to navigate the complexities of social services, education and healthcare after initial assessment. | 93% of patients required social service referrals. |

| Messmer et al 83 | WE CARE | In-person or offsite patient navigator referral to community-based health and social services. | 27.2% of families screening positively to housing as unmet need referred by on-site patient navigator, 30.7% of families screening positively to housing as unmet need referred by remote patient navigator. |

| Oldfield et al 74 | WE CARE and Accountable Health Communities | Positive screens added to patient’s medical record, notifying patients’ primary paediatrician of positive screens, allowing paediatrician to make targeted referrals as needed. | Not reported. |

| Pierse et al 106 | Housing Concerns Survey | Provision of information for families on how best to keep their home warm, dry, and safe, provision of a housing-related intervention, for example, mould kit, heater and/or referral for a housing relocation, or health or social referral | A total of 5537 interventions were delivered; bedding, heaters and draft stopping delivered over 90% of the time. |

| Polk et al 75 | Health Leads | Depending on category of need, patient provided rapid resource referral, that is, information only or enrolled in Health Leads programme where patient is contacted by a Health Leads advocate. | 6.3% of successful resource connection for housing. |

| Power-Hays et al 96 | WE CARE | Provision of relevant resource sheet and referral to local community organisations for the specific needs endorsed. Providers and patients decided whether families also required referral to social worker; social workers called families with positive screens 2–3 weeks after their visit. | 80% of patients were referred to a relevant community organisation; 45% of patients available via follow-up phone call reached out to the community organisation; 69% of patients who reached out stated that the community organisation was helpful. |

| Ray et al 78 | WE CARE and Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks and Experiences (PRAPARE) | Universal provision of community resource packet at 2-week follow-up. | Resource packet used by 37% of those who had reported a social need. |

| Sandoval et al 102 | MAMA’s neighbourhood programme prenatal screening questionnaire | Care coordinator providers referral or facilitates contact with agencies or community organisations. | Not reported. |

| Selvaraj et al 70 | Addressing Social Key Questions for Health Questionnaire | Referral made to community resources in relation to unmet social needs, including referrals made in relation to housing/bill insecurity. | 284 (11%) total referrals made in relation to unmet social needs; 111 (4.3%) referrals made in relation to housing/bill insecurity. |

| Semple-Hess et al 105 | Questions developed through existing screening tools | Caregivers with any emergent unmet need provided a social work consultation, as per institutional practice. | Not reported. |

| Sokol et al 107 | Developed from PRAPARE | Referral to a social worker to provide support with identified need. | 14% of parents and youths requested a referral for identified needs. |

| Uwemedimo and May103 | Family Wellness Screen | Referral to local community resources by trained navigators and follow-up to ensure linkage to resource. Trained navigators either searched online social service databases or referred to social service case managers at designated partner community organisations. | Approximately one-third (30.9%) successfully used programme-provided resources at 12-week follow-up. |

| Zielinski et al 86 | WE CARE screening tool | Provision of additional resources on homelessness and/or social work referral relating to homelessness. | 14 (93%) provision of additional resources on homelessness; 11 (73%) social work referral relating to homelessness. |

aOR, adjusted OR.

Quality assessment and risk of bias

Assessing studies using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool, the four RCTs scored highly. One RCT met all the criteria44 81 and three studies scored highly, meeting the majority of the criteria. It was unclear whether cluster RCT randomisation by Garg et al 43 was adequately performed and whether participants adhered to the assigned intervention. The study by Gottlieb et al 80 did not provide adequate information on blinding, and the RCT by Bovell-Ammon et al did not provide information on participant adherence to the intervention, randomisation and blinding.84 There were three robust quantitative non-randomised studies, scoring highly against most criteria.65 83 85 The study by Patel et al did not provide complete outcome data,85 and it was unclear in the study by Bottino et al whether participants were representative of the target population or whether there was complete outcome data.65 Twenty-nine studies were categorised as quantitative descriptive, and quality scores were mixed. A common issue related to the representative sample of the target population, with the sample size not being representative in 7 of the 29 studies, and another 5 studies providing insufficient information to assess whether the sample size was representative. The risk of non-response bias was low in 16 of the quantitative descriptive studies.30 73 75 76 79 82 86–89 99 104–106 The two mixed methods studies were of good quality however both did not adequately address inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results and did not adhere to the tradition of each method.97 98 There were seven QI studies, assessed using the QI-MQCS. Five of the seven studies scored highly, scoring well in 10 of the 15 criteria.59 91 94–96 Issues with QI studies included adherence, reporting data on health-related outcomes, organisational readiness and spread. See tables 3 and 4 for quality assessment of included studies.

Table 3.

Quality assessment using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool tool

| Study | Category of study design | Are there clear research questions? | Do collected data allow to address research question? | Is randomisation adequately performed? | Are groups comparable at baseline? | Are there complete outcome data? | Are outcome assessors blinded to intervention provided? | Did participants adhere to the assigned intervention? |

| Bovell-Ammon et al 84 | Quantitative RCT | Y | Y | Unclear | Y | Y | Unclear | Unclear |

| Garg et al 43 | Quantitative RCT | Y | Y | Unclear | Y | Y | Y | Unclear |

| Gottlieb et al 44 81 | Quantitative RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Gottlieb et al 80 | Quantitative RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Unclear | Y |

| Study | Category of study design | Are there clear research questions? | Do collected data allow to address research question? | Are participants representative of target population? | Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? | Are there complete outcome data? | Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? | During study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? |

| Bottino et al 65 | Quantitative non-randomised | Y | Y | Unclear | Y | Unclear | Y | Y |

| Messmer et al 83 | Quantitative non-randomised | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Patel et al 85 | Quantitative non-randomised | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Study | Category of study design | Are there clear research questions? | Do collected data allow to address research question? | Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? | Is the sample representative of the target population? | Are the measurements appropriate? | Is the risk of non-response bias low? | Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? |

| Badia et al 99 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Beck et al 100 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Unclear | Unclear | Y | Unclear | Y |

| Costich et al 87 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| De Marchis et al 57 71 72 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y |

| Garg et al 66 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y |

| Hardy et al 88 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hassan et al 47 67 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Unclear | Y | Unclear | Y |

| Heller et al 73 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hershey et al 90 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Unclear | Y | Unclear | Y |

| Fiori et al 89 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fiori et al 104 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Kumar et al 82 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Matiz et al 101 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | |

| Molina et al 68 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Unclear | Unclear | Y | Unclear | Unclear |

| Oldfield et al 74 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Pierse et al 106 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Unclear | Y |

| Polk et al 75 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Ray et al 78 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Razani et al 77 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Unclear | Y | Unclear | Y |

| Rhodes et al 69 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y |

| Sandel et al 30 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Unclear | Y |

| Sandoval et al 102 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Selvaraj et al 70 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Unclear | Y |

| Semple-Hess et al 105 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Sokol et al 118 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Spencer et al 76 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Uwemedimo and May103 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y |

| Vaz et al 79 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Zielinski et al 86 | Quantitative descriptive | Y | Y | Unclear | Unclear | Y | Y | Y |

| Study | Category of study design | Are there clear research questions? | Do collected data allow to address research question? | Is there adequate rationale for using a mixed methods design to address the research question? | Are there different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? | Are the outputs of integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? | Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? | Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? |

| Farrell et al 97 | Mixed methods | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Koita et al 98 | Mixed methods | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

Table 4.

Quality assessment using the Quality Improvement Minimum Quality Criteria Set V.1.0

| Study | Organisational motivation | Intervention rationale | Intervention description | Organisational characteristics | Implementation | Study design | Comparator | Data source | Timing | Adherence | Health outcomes | Organisational readiness | Sustainability | Spread | Limitations |

| Arbour et al 94 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Colvin et al 59 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Unclear | Unclear | Y | N | Y |

| Fiori et al 95 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hensley et al 92 | Unclear | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y |

| Higginbotham et al 93 | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Unclear | Y | Y | N | Unclear | N | N | N | Y |

| Denny et al 91 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Unclear | Y | N | Y |

| Power-Hays et al 96 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y |

Screening tools and housing questions

Our systematic review found 29 social screening tools that include housing questions. The tools used in clinical and social service settings varied widely. The purpose of all tools was to screen for health-related or well-being-related social needs among children, adolescents and/or families. The tools were used by healthcare or social service workers to facilitate asking patients or clients questions about social needs, including housing. There were two distinct approaches to screening; one approach was a general social determinants of health screening where housing was one of multiple domains among other social needs, and a second approach was to focus on housing as one domain, and only ask detailed housing-related questions. In the first approach, social needs assessed in tools included housing, food security, income, employment, education, childcare needs, transportation needs, healthcare access, legal concerns, medical insurance, violence, social connection and isolation.

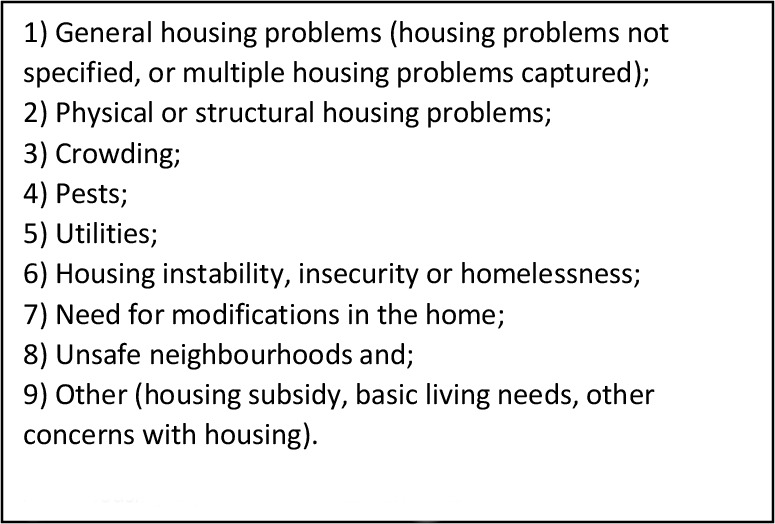

The housing questions asked of participants varied across studies. Housing questions extracted from the included studies were divided into nine categories (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Housing aspects asked in screening tools.

Housing instability, insecurity or homelessness were the most common housing-related screening questions across the studies, with questions about homelessness, risk of homelessness, sleeping in a shelter, sleeping outside or in a place not meant for sleeping, sleeping in unsafe housing, frequent moving and temporary or unsafe housing.30 43 44 57 65 67 68 71–80 82–84 86–90 92–97 101 102 105 107 Utilities as an unmet need, especially in relation to home heating, were included as a common housing issue captured in the social screening tools of studies in this review. Problems with utilities, such as utilities being shut off, threats of utilities being shut off or concern about not being able to pay for utilities and in relation to heating the home,43 73 was asked as part of social screening in eighteen (n=18) studies.43 47 65–68 70 71 74–76 78 79 88 90 91 100 106 The questions about utilities were often asked alongside broader housing question in screening tools, for example, “[Are you having] problems with housing conditions (overcrowding, evictions, lead, utilities, mold, rodents)?”100 and “Do you have trouble paying utilities or maintaining a safe place to live?”91

Crowding was a common item in the social screening tools, with the following terms being used: ‘overcrowding’,100 ‘doubled up or overcrowded in an unsustainable way’97 and ‘need enlarged rooms at home’99 Crowding was considered a part of housing instability in one tool, that is, ‘housing instability: doubled up with another family’.65 Some tools asked families about general housing problems and either did not specify the nature of the housing problem, or asked about multiple housing-related issues within the one general question.44 47 59 66 67 97 100 Structural and physical housing problems67 included questions specific to the quality or condition of the home,68 73 80 89 92 95 106 mould or damp59 100 103 106 and unhealthy living environments.77 See table 1 for further detail on the housing questions asked in screening tools.

Validity, feasibility and acceptability

Fourteen (n=14) screening tools had been validated, including the Family Wellness Screening tool,103 Well Child Care, Evaluation, Community Resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education (WE CARE) tool,66 The Online Advocate,47 The Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks and Experiences (PRAPARE) tool,108 The Health Leads Screening Toolkit109 as well as other tools used across studies.43 66 77 80 94 98 99 108 The studies included in this review did not provide detailed information on validity. It is not clear whether any of the screening tools are robust in producing their intended result, and to what extent the housing questions in particular are suitable for their aims.

The Addressing Social Key Questions for Health questionnaire had been tested for validity and feasibility.70 The WE CARE tool used across multiple studies included in this review had been validated and tested for feasibility and acceptability.29 86 The Income, Housing, Education, Legal status, Language/Immigration, Personal Safety tool was tested for validity, sensitivity and specificity.59 110 Some tools were not validated however underwent other forms of testing such as feasibility, reliability or sensitivity. The screening tool used in the study by Higginbotham et al was tested for feasibility,93 as was the HealthBegins Upstream Screening tool by Hensley et al.92 The Injury Prevention tool was tested for reliability.91 Insufficient information was provided on the validity, feasibility or acceptability of the tools used in 14 studies.30 65 68 69 73 82 85 88 91 93 100–102 105 The information provided for the Quick Risks and Assets Family Triage tool showed some indication of content, construct and predictive validity, however it is unclear whether it was validated.97 The tool used in the study by Beck et al did not validate the housing questions, however other questions in the tool were validated.100 The first two housing questions of the Accountable Health Communities instrument, used in two studies,71 74 had been adapted from the validated PRAPARE tool.108

The studies did not explore testing the cultural acceptability or appropriateness of the screening tools. The study by Badia et al analysed the cultural acceptability of the European Child Environment Questionnaire in order to adapt it to the Spanish context. The study by Uwemedimo and May took into consideration unique challenges faced by immigrant families when screening for social needs and recommended screening tools to be culturally sensitive through availability in multiple languages and for bilingual or multilingual patient navigators to support patients from immigrant backgrounds. Some studies involved screening in languages other than English, for example, in Spanish.68 70 74 77 79 80 98 99 The study by Power-Hays et al offered screening in English, Spanish and Haitian Creole, and, provided patients with low literacy to have the screener read to them.96

Social prescribing

Twenty-seven studies reported provision of information, and/or social prescribing, that is, a linking or referral occurred after identifying a social need as part of screening. Several studies provided patients with a community resource guide, a list of local housing services, community resource information or clinic-based resources43 44 57 59 70–73 75 78 84 87–89 92–95 after screening for housing and other social needs. Social prescribing was also common, with patients screening positively being referred to a social worker, care coordinator, care navigation service, community health worker or advocate,59 67 75 83 84 86 88 90 95 96 101 102 107 social service agency or community organisation,87 96 103 referral to a housing and child welfare demonstration project97 or provided intensive case management in the form of wraparound services relating directly to a family’s specific needs.84 In the study by Pierse et al families were referred from healthcare settings to the Well Homes programme and asked about their perception of their housing conditions, leading to all families receiving information about keeping warm, dry and safe and some being offered an intervention such as a mould kit, or a housing relocation referral.106 The RCT by Bovell-Ammon et al on medically complex families experiencing housing instability or homelessness provided the intervention group with intensive case management and wraparound services, such as support with searching for housing, eviction prevention, legal or financial services and if eligible, provision of a public housing unit.84 The study by De Marchis et al 57 offered information about local services and resources to all patients, regardless of whether the patient participated in their study on social risk screening. In several studies, a patient navigator helped patients with contacting resources or community-based health and social services.44 81 83 92 103 The study by Messmer et al investigated the impact of on-site versus remote patient navigators to address parent’s unmet social needs, finding that referrals for housing were similar when an on-site patient navigator was present versus a remote patient navigator (27.2% vs 30.7).83 Actions specific to housing-related problems, such as a social work referral specific to homelessness, were evident in 11 of the 27 studies. In the study of children with high-risk type 1 diabetes by Hershey et al, families screened for social needs were offered assistance in the form of goal-setting with the support of a community health worker.90 Housing-specific goals included access affordable housing or affordable home renovations, help parent enrol in first-time homeowners’ programme and assist in negotiating rental arrears.90 Screening for social needs resulted in an increase in referrals to appropriate services or resources, and some studies found that screening and subsequent referral led to an improvement in the housing-related issue,43 87 or an improvement in child health.44 81 84 Interestingly, social screening and social prescribing studies appear to be increasing, with the majority of studies found to be published from 2019 onwards. See table 2 for a summary of information relating to actions as a result of screening for housing issues, or social prescribing.

Discussion

This systematic review provides a synthesis of housing-related screening questions asked of families in healthcare and social service settings, and the subsequent actions taken to support families with housing problems as part of screening. This synthesis demonstrates that the housing questions asked in screening tools are highly variable and there is no standard way to ask families about housing in the healthcare and social service setting. Not all housing screening tools are designed with provision of a resource or social prescribing embedded, for example, some housing screening tools are simply a set of questions to ask families about housing and practitioners using these tools are not prompted to provide information, referral or links to the community sector after screening. This raises ethical considerations in relation to screening and social prescribing. For example, is it ethical for health professionals and social service workers to collect information about a patient’s housing without providing support if the housing condition is affecting the patient’s health? Another question raised is what is the benefit of screening for housing, especially if there is no subsequent action taken to address housing issues? Based on our findings, we provide some recommendations for screening and social prescribing for families experiencing housing issues, however it is important to note that screening and social prescribing for social determinants of health is an emerging area of healthcare and there is limited information on the validity of the screening tools included in this review. Furthermore, the evidence base for social prescribing is currently lacking due to difficulties in the generation of robust studies evaluating social prescribing in healthcare.111 To our knowledge, this is the first time a systematic review has been conducted to catalogue the social screening tools used by healthcare and social service staff to ask patients or clients about their housing and address housing problems through an action such as provision of information or social prescribing.

Housing screening questions asked in healthcare and social service settings

There was variation in the wording of screening questions and type of housing issues asked about when screening for housing problems. None of the included studies commented on standard ways to ask about housing. These findings indicate that there are no standards for asking families about housing problems in healthcare and social services. This is an unsurprising finding, as screening and social prescribing to address social determinants of health in the healthcare and social service context is an emerging practice.53 112 As more screening tools emerge and are validated, clinicians and social service staff may be more likely to choose from a range of predeveloped validated screening tools rather than design their own. This is evident in the use of the WE CARE tool, with seven studies included in this review utilising this tool. A complexity with screening for housing is that definitions and measurements of housing issues are highly variable, inconsistent and/or are rarely defined explicitly across the literature, leading to problems with their adequate measurement and capture. As an example, housing insecurity is measured, defined and characterised in many different ways. Varying definitions of housing insecurity capture dimensions of housing stability, affordability, quality, safety and/or homelessness, and the inconsistency and incompleteness of these definitions mean that people actually experiencing housing insecurity may not be captured within existing housing insecurity measures.113 This is likely to be true of other housing measures in clinical and social service settings and calls for greater consistency, completeness and standardisation of housing issues.113

While it is widely recognised that social determinants such as housing, education, income and food security have an impact on health and well-being, the best way to ask about social needs in healthcare remains unclear.48 49 53 112 There was no rationale provided for the choice of housing questions, and for subsequent actions. Twenty-five papers (n=25) in this review provided the exact wording of housing questions used in their studies, while some studies only provided prompts rather than the exact questions, for example, ‘home heating’,43 ‘residential mobility’,82 ‘concerns about the physical condition of your housing’80 or ‘unhealthy housing’.94 In the latter examples it was not clear how the questions were asked, for example, whether healthcare and social service staff asked questions word-for-word, or used the screening tool questions as prompts or as a guide. Some studies reported the name of the screening tool they used, but did not list the questions. The screening tools captured different housing aspects, from physical housing conditions to the social conditions of housing instability, housing affordability and neighbourhood safety. These different aspects align with the four pillars of housing and health equity: cost, conditions, consistency and context,114 however each screening tool asked a different combination of questions, and sometimes asked several questions within one broad housing question.

Validated housing screening tools

Most screening tools used in the studies had been tested for construct validity, face validity, feasibility, reliability, sensitivity, specificity and/or acceptability. Limited information was provided on the testing of the specific housing questions embedded in screening tools. Some studies provided information on the validity of housing questions, however the majority did not. It is unclear whether the housing questions used in the screening tools of this review are rigorously tested and robust in producing the intended result of screening. Housing questions were often adapted from existing surveys such as the American Household Survey and were not necessarily validated, which provides some concern for the robustness of the tools. Future research should rigorously test the quality of housing questions embedded in social screening tools and ensure cultural appropriateness and validity in the specific contexts and among the populations the tools are being used.

Recommendations for practice and research

While all screening tools aimed to identify one or more housing issues, 27 of the 42 studies (64%) included in this review offered a subsequent action as a result of identifying a social need. This finding is important, as it shows that not all screening tools for social determinants of health are designed to facilitate provision of information or subsequent social prescribing by the healthcare or social service provider. There was no information provided in the studies as to why some tools included an action and others did not.

Most studies focused on testing social screening in the healthcare or social service setting and did not aim to examine social prescribing after screening. Several studies highlighted the need for appropriate resources to be provided to families,66 74 91 92 103 a finding consistent with the literature which highlights the need for clinicians to be aware of community resources available for the effective and appropriate treatment of social determinants of health.115 This raises an ethical issue of screening and referral, versus screening only; identifying an issue without offering an action to support a family experiencing housing issues may be considered unethical. However, if appropriate resources are not available, or providers are unclear whether the action they offer is effective, it may be preferable not to offer an action. Identifying a housing issue without providing support may be acceptable in cases where a suitable pathway to address the issue is unavailable. In the study by Hardy et al, the tool was developed based on the social worker’s capacity to adequately address the identified social need.88 While research has found that providing an action on screening for social determinants of health may lead to addressing social issues, health and social service providers should ensure that the actions and referral pathways are appropriate for their patients and clients.

Regarding the type of information provided to patients who screened positively to general social needs or housing, studies did not provide details on the information provided. Oldfield et al found that parents prefer to receive information on social needs through email, text message or a paper print-out, rather than an in-person consult with a community health worker, however this was a small sample size and may not be generalisable.74

Several screening practices led to the automatic referral of patients to community services when a patient indicated an unmet need. Garg et al 116 suggests avoiding this approach. It is critical that healthcare providers gauge whether patients wish to be assisted.116 As screening for social determinants of health and social prescribing is an emerging area of practice, and those screened are often from ‘disadvantaged’ groups, services are encouraged to ensure patients are provided ample opportunity to share decision-making in the screening process, including decision-making on any subsequent material assistance. Furthermore, it is recommended to tailor questions to specific communities by identifying the most common problems experienced by that community.60 Understanding the needs and unique context of the population group being screened is vital to increase the potential for a housing screening and referral tool to effectively support patients or clients with their housing needs.

Screening for social needs such as housing is considered sensitive. It is worth noting that several studies discussed the need for clinicians to be adequately trained in asking sensitive questions.59 67 100 Selvaraj et al 70 suggested clinicians establish relationships with families before screening for social needs. Some screening tools provided introductory framing to social screening to provide context behind a clinician asking sensitive questions, to ensure the patient does not feel targeted or singled out, and to ensure the patient understands that the health worker is asking so they can help address any issues. For example, the HealthBegins Upstream Risks Screening Tool and Guide begins with the opening sentence: “Everyone deserves the opportunity to have a safe, healthy place to live, work, eat, sleep, learn and play. Problems or stress in these areas can affect health. We ask our patients about these issues because we may be able to help”. The Safe Environment for Every Kid tool frames screening in the following way: “Being a parent is not always easy. We want to help families have a safe environment for kids. So, we’re asking everyone these questions. They are about problems that affect many families. If there’s a problem, we’ll try to help”. Introducing social screening with reasoning, specifically linking screening to action, may support patients in answering sensitive questions and alleviate stigma associated with experiencing social hardship.

The majority of studies screened high-risk populations, such as families on low incomes, children with a disability, teenage parents, families with open child welfare cases, medically complex families and immigrant families. This indicates that it may be important to screen those who may be more likely to experience housing problems. Tailoring screening to specific communities by identifying the most common problems experienced by that community is considered a critical element of screening for social determinants of health.60 It is possible that the housing screening questions in the identified screening tools are highly variable because they are tailored to local contexts. The study by Semple-Hess et al, for example, attempted to address the most commonly occurring issues experienced by their patients.105 Unfortunately, this approach may mean that less common housing aspects are not captured. While most studies captured race and/or ethnicity of study participants, only two studies specifically examined the cultural acceptability and appropriateness of the screening tool used with families. This is interesting given the high proportion of Hispanic/Latino participants65 73 74 77 80 84 87 94 98 101 and African-American participants in multiple studies,30 65–67 70 76 83 84 88 and the over-representation of Maori and Pacific people in one study.106 However, Garg et al 116 suggests screening all patients rather than targeting families based on demographic characteristics, as screening only those at increased risk may reinforce preconceived ideas about particular groups and lead to stigmatisation. Further research is needed to ascertain a targeted versus a general approach to screening.

Studies did not report whether people with lived experience of housing problems were consulted in the development of questions. Rather, it was common for research teams, healthcare and social workers and institutional stakeholders to develop questions. Engaging directly with people who have lived experience of housing problems may lead to more appropriate and acceptable questions to specific communities.