Abstract

Reports, studies, and surveys have demonstrated telehealth provides opportunities to make health care more efficient, better coordinated, convenient, and affordable. Telehealth can also help address health income and access disparities in underserved communities by removing location and transportation barriers, unproductive time away from work, childcare expenses, and so on. Despite evidence showing high-quality outcomes, satisfaction, and success rates (e.g., 95% patient satisfaction rate and 84% success rate in which patients were able to completely resolve their medical concerns during a telehealth visit), nationwide adoption of telehealth has been quite low due to policy and regulatory barriers, constraints, and complexities.

Keywords: pandemic, policy, telemedicine, regulatory

Introduction

Reports, studies, and surveys have demonstrated telehealth provides opportunities to make health care more efficient, better coordinated, convenient, and affordable. Telehealth can also help address health income and access disparities in underserved communities by removing location and transportation barriers, unproductive time away from work, childcare expenses, and so on.1–4 Despite evidence showing high-quality outcomes, satisfaction, and success rates (e.g., 95% patient satisfaction rate and 84% success rate in which patients were able to completely resolve their medical concerns during a telehealth visit),5 nationwide adoption of telehealth has been quite low due to policy and regulatory barriers, constraints, and complexities.

Health care services delivered through telehealth and other communications technologies are regulated at both the federal and state levels. Coverage and reimbursement policies vary among the different payers/plans (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers) and may be defined by state telehealth parity laws. Restrictions placed on provider reimbursement have been cited as the number one barrier to adoption.6,7 Licensure, privacy and security, remote prescribing of controlled substances, and other related policy, legal and regulatory matters are subject to myriad rules and guidelines promulgated by various regulatory bodies (see details below). However, with the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, the crisis triggered rapid federal and state-level temporary policy changes that lifted many of the legacy coverage and payment barriers and accelerated adoption during the outbreak. With relaxed regulations, the number of Medicare beneficiaries using telehealth skyrocketed in the early weeks of the pandemic. According to Medicare claims data, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) reported an increase in utilization of ∼12,000% in just a month and a half between early March and mid-April 2020.8 As the pandemic took hold, many states also took action to expand broad coverage and payment of telehealth services under Medicaid and allow out-of-state providers to treat their residents using telehealth.9,10 Approximately 34.5 million telehealth services were delivered to Medicaid and CHIP beneficiaries from March through June 2020, which represents an increase of 2,632% compared with March through June 2019.11 Commercial plans expanded their policies, which also resulted in increased utilization with some plans implementing payment parity, removing copays, and offering telehealth services for free.9 CMS also allowed Medicare Advantage plans to add more telehealth benefits during the crisis without going through the normal application review process.

Removing long-standing regulatory constraints on payment for telehealth services resulted in high adoption rates across the nation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, to be prepared for any future pandemic, sustained adoption of telehealth is needed. Therefore, it is the opinion of the members of this Think Tank that permanent policy changes that allow broad coverage and payment of telehealth services, as well as, cross-state licensing reforms are essential to incentivize providers to continue to invest in national telehealth and telecommunications infrastructure. Policies that enable coverage and payment parity for telehealth services should be implemented in the short term beyond the public health emergency (PHE) to allow time for adoption of telehealth services to become sustainable. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic presents an exceptional opportunity for data collection and analysis since it is the first broad implementation of telemedicine in the United States. For the first time, providers, patients, and policymakers can see and measure the impact of telemedicine on care delivery, health care access disparities, and cost. Keeping the current relaxation of restrictions and payment parity for the short term (2–3 years) will allow time to gather appropriate data to drive appropriate policy development.

Building national infrastructure for providers to deliver telehealth services will also provide the necessary framework to keep businesses in operation, provide distance education, and for other purposes during any future pandemic. In addition, a national infrastructure will foster health and digital equity and transformation of the health care system from fee-for-service to value-based care.

Telehealth Coverage and Payment (Pre-COVID-19)

Restrictions on coverage and payment of telehealth services exist today. At the federal level, coverage and reimbursement rules for telehealth under the Medicare program are defined in §1834(m) of the Social Security Act (4) (42 U.S.C. 1395m(m)(4)), which was enacted >20 years ago and remains in effect today. The law limits payment for telehealth services to rural geographic areas, certain types of facility-based originating sites, certain types of providers, limited types of services, and audiovisual technologies. Legislative actions in 201812,13 removed the geographic and originating site restrictions to create nationwide payment for telestroke, end-stage renal disease, and substance use disorder treatments.

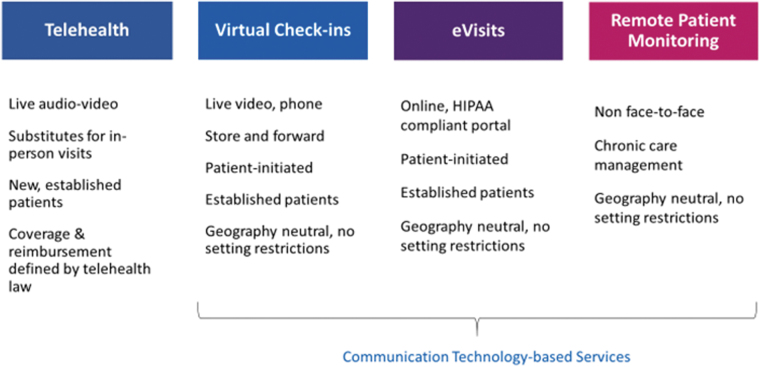

At the regulatory level for Medicare, CMS implements regulatory policy changes for telehealth and other communication technology-based services (CTBSs) through the annual physician fee schedule (PFS) process. A telehealth visit must substitute for an in-person visit (e.g., patient present) and be furnished through real-time two-way audio–video technologies. For CY 2020, there are 112 billing codes on the Medicare telehealth list.14 CMS also reimburses providers for CTBSs furnished to Medicare beneficiaries through synchronous (phone and video) and asynchronous (store and forward) brief virtual check-ins, e-visits (digital visits through an online portal), and remote patient monitoring (RPM). CMS does not consider CTBS to be “telehealth”15; therefore, payment for these services is not constrained or subject to the rural geographic, originating site, and other requirements defined in the statute (see CMS types of services in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CMS types of services. CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

In the shift to value-based care, CMS has targeted Medicare Advantage plans, accountable care organizations (ACOs), and bundled payments that reimburse providers based on their ability to improve quality of care in a cost-effective manner or lower costs while maintaining standards of care. Under value-based payment models, CMS offers more flexible rules for using telehealth to deliver care (no geographic restrictions, the home may serve as a qualified originating site, etc.).16

At the state level, states have great flexibility in shaping their own rules for telehealth coverage and reimbursement under Medicaid. Thus, policies for telehealth vary from state to state, with 51 different sets of rules and requirements including Washington, DC.10 Some states also adopt laws for how telehealth is covered and reimbursed by the private payers. These laws are oftentimes referred to as the “telehealth private payer parity laws.” These type of laws also vary widely from state to state with some states addressing only “coverage” parity, which requires private payers to cover telehealth services to the same extent that the plan covers services for in-person care, whereas other states address both coverage and payment. Today, all 50 states and DC reimburse for live audio–video telehealth under Medicaid fee-for-service and the vast majority of states have a coverage parity law in place.17 The Center for Connected Health Policy's Fall edition of “State Telehealth Laws and Reimbursement Policies” summarizes current telehealth policies, laws, and regulations across the nation. States and private payers are also adopting value-based models under both fee-for-service and managed care.

COVID-19 PHE Policy Changes

When the COVID-19 pandemic arrived, policymakers took action aimed at removing many of the restrictions on telehealth, to drive rapid adoption and utilization during the crisis. At the federal level, the U.S. Congress quickly passed three pieces of historic legislation with major policy changes for telehealth and substantial funding for telehealth infrastructure through grants and funding awards. These legislative changes and the emergency authorities granted to the Department of Health and Human Services and at the state level set the ball in motion for a series of major policy changes that enabled broad reimbursement of telehealth in the Medicare program during the PHE. Following are key interim temporary rule changes for telehealth services during the COVID-19 PHE:

Removes the geographic and originating site restrictions to allow providers to serve patients in all areas of the country and in all settings including at home.

Provides reimbursement for telehealth services at the same rate as in-person visits for all diagnoses, not just services related to COVID-19 (e.g., pays both facility and nonfacility rates).

Expands range of eligible providers who can be paid for furnishing telehealth services, including federally qualified health center (FQHCs), rural health clinic (RHCs), physical therapists (PTs), occupational therapists (OTs), and speech-language pathologists (SLPs).

Expands modalities that can be used to provide telehealth to include audio-only/telephone services.

Expands eligible telehealth services that can be billed (over 120+ acute, ambulatory, and other services added to the list).

Enforcement discretion of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) requirements allows flexibility for telehealth through popular video chat applications such as FaceTime or Skype.

Allowances for providers to reduce or waive cost-sharing requirements for telehealth visits.

The full listing of covered Medicare telehealth services during the COVID-19 PHE and those services that are reimbursed using audio-only technologies may be found here.

Expanded coverage and payment policies for FQHCs and RHCs during the COVID-19 crisis may be found here.

CMS also expanded coverage and reimbursement policies for use of other digital health tools during the PHE, including virtual check-ins, e-visits, telephone visits, and RPM. Key policy changes included the following:

Expansion of services to both new and established patients

Expansion of eligible providers who can bill for services

Expansion to both acute and chronic conditions for RPM.

States also took rapid action that temporarily removed policy barriers to telehealth to address the COVID-19 PHE. Similar to CMS, Medicaid and the private insurers expanded coverage and reimbursement policies for telehealth, including use of audio-only/telephone and allowed cost-sharing waivers of co-pays and other fees.

Coverage and reimbursement policy changes implemented by both governmental programs and private plans during the PHE will expire unless policymakers take action to make changes permanent. At the federal level, temporary policies for telehealth will end when the PHE period expires unless Congress takes action to pass legislation and/or CMS adopts new rules. Some states and private plans have already taken steps to adopt COVID-19 PHE changes on a permanent basis, whereas others have reverted back to pre-COVID policies and rules (Table 1).

Table 1.

Medicare Billing: Place of Service, Modifiers, and Frequency

| MEDICARE | PRE-COVID-19 PHE | DURING COVID-19 PHE |

|---|---|---|

| Telehealth | Use POS (02) telehealth No modifier Billing frequency limitations Inpatient hospital subsequent care, once every 3 days Inpatient critical care, once per day Inpatient SNF subsequent care, once every 30 days |

Indicate POS where the service would have been furnished in-person (e.g., office POS 11, ED POS 23, inpatient POS 21) Use modifier 95 Billing frequency limitations removed for inpatient critical care and hospital/SNF subsequent care |

| Virtual check-ins, e-visits, RPM | Use POS where the patient is located No modifier |

No change |

State Medicaid programs and private payer policies and guidance on telehealth and other types of technology-enabled services can be found on their respective websites.

ED, emergency department; PHE, public health emergency; POS, place of service; RPM, remote patient monitoring; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Sources:

-

CMS

○ CMS MLN Medicare Telehealth

○ CMS General Telehealth Information

○ CMS Chronic Care Management

○ CMS MLN Use of Modifier for Telestroke

○ CMS Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 12

○ CMS Interim Final Rule with Comments 1

○ CMS Interim Final Rule with Comments 2

○ CMS MLN CY 2020 Physician Fee Schedule PHE Interim Final Rules

○ CMS MLN Summary of Policies During PHE

○ CMS FAQs on Medicare FFS Billing

○ Listing Medicare Telehealth Codes COVID-19

○ HHS Telehealth

○ CMS Telehealth Video: Medicare Coverage and Payment of Virtual Services

Center for Connected Health Policy—www.cchpca.org

American Telemedicine Association—www.americantelemed.org

Policy Recommendations

-

Providers

○ Stay apprised of coverage and reimbursement policy changes and timelines and plan for a postpandemic policy landscape when temporary changes may expire.

○ Keep team informed and provide training (virtual) on policy changes, reimbursement opportunities, documentation, compliance, appropriate use of telehealth (e.g., when to use video vs. audio), and so on.

○ Leverage all opportunities for billing telehealth and CTBS.

○ Create plans/strategies that position telehealth for long-term sustainability.

○ Implement telehealth infrastructure/programs to learn how to do telehealth, build team, expertise, and so on to be prepared for any future pandemic. Make telemedicine part of normal day-to-day operations.

-

Policymakers

○ Adopt/maintain continued broad coverage and payment policies for telehealth and other CTBSs to incentivize provider investment in infrastructure/drive adoption to be ready for any future pandemic, as well as to enable equity in health care access and connectivity and transformation to value-based care.

▪ Remove geographic and originating site restrictions to enable health care access equity and care into the home.

▪ Expand range of authorized providers (FQHCs, RHCs, PTs, etc.) who can receive payment for telehealth and other services.

▪ Allow a valid practitioner–patient relationship to be established by telehealth without requiring an in-person encounter.

▪ Hold providers to the same standard of care as in-person care and allow providers to decide when/if a service is clinically appropriate for audio–video, audio-only, store and forward, and so on.

▪ Align reimbursement rates to modalities (e.g., video vs. audio-only).

▪ Redefine “telehealth” as audio–video only to allow use of audio-only technologies when clinically appropriate.

▪ Remove supervision and frequency limitations attached to reimbursement of telehealth services for inpatient critical care and inpatient subsequent care (hospital and skilled nursing facilities).

▪ Create telehealth reimbursement for home health agencies.

○ Adopt/maintain coverage and payment parity policies in the short term beyond the COVID-19 PHE to maintain financial incentives to allow adoption levels to stick, build infrastructure, expand the period of time to collect data from which to base future payment policy changes.

○ Create funding opportunities through grants and other mechanisms to provide support for telehealth/telecommunications infrastructure to be ready for any pandemic.

○ Establish rules and guiding principles for hospitals to remain open during a pandemic.

○ Align policies, standardize billing codes and modifiers among payers to reduce complexity/confusion, and make it easier on providers to react to pandemics in the future.

○ Provide clear accessible guidance/resources on telehealth rules and regulations during a pandemic.

Licensure

A major policy barrier inhibiting the adoption of telehealth is licensing. Licensing of health care professionals falls under the purview of each state. Providers must follow state laws regarding licensing that require providers to hold a current and valid license, certification, or registration to practice in their specialty in every state in which they will provide care and/or render services. Therefore, for a telehealth encounter, the provider must adhere to the licensing rules and regulations of the state where the patient is located. The licensing rules vary significantly from state to state. A few states issue special licenses or certificates related to telehealth that allow out-of-state providers to render services through telehealth when certain conditions are met. Other states have laws that make allowances for practicing in contiguous states or in certain situations where a temporary license might be issued under certain conditions.18 However, the vast majority of states require telehealth providers to secure individual state licenses for multistate practices. The cost in time, money, and resources of applying for licenses in each state in which a physician seeks to practice is a major barrier to expanding access to medical services across state lines. Because of these challenges, states are joining interstate licensing compacts such as the Interstate Medical Compact (IMLC) and Nursing Licensure Compact. These compacts strive to ensure state-based regulation of the medical profession while easing barriers; however, these strategies remain inadequate. For example, although the IMLC expedites the licensing process, it still requires a physician to apply and pay the full cost for a separate license in every state. These state-by-state approaches ultimately create disincentives for providers to adopt telehealth, thus preventing patients from receiving critical, often life-saving medical services that may be available to their neighbors living just across the state line. Regulatory restrictions also create economic trade barriers and artificially protect markets from competition.

During the PHE, Medicare and Medicaid requirements to be licensed in the state where services are being provided were temporarily waived under certain conditions, although state licensing requirements still apply.19 All 50 states and DC introduced licensure and renewal flexibilities to expand medical personnel during the PHE. To ensure the benefits of telehealth continue to be accessible by providers and patients across the nation, licensing reforms are needed.

Source: FSMB U.S. States and Territories Modifying Requirements for Telehealth in Response to COVID-19.

Policy Recommendations

-

Providers

○ Stay apprised of licensure policy changes during a pandemic.

○ Keep team informed/trained to stay compliant.

○ Be aware of licensure compacts and take advantage of these vehicles for cross-state telehealth practice.

-

Policymakers

○ Permanently remove barriers to interstate licensing requirements for telehealth providers during any pandemic or emergency.

○ Stakeholders to collaborate to create an interstate telehealth framework that removes barriers, lays out the rules of the road, spurs health care innovation, and enables the provision of health care across the country.

○ Take lessons learned and make process improvements to make participation in a licensing compact easier and less costly for providers.

HIPAA Privacy/Security

Health care providers furnishing care through telehealth or in-person must comply with federal and state laws regarding privacy and security of patient health care information (e.g., HIPAA). During the COVID-19 PHE, the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) issued a public notice stating it would not impose penalties for noncompliance with regulatory requirements under the HIPAA rules for “…healthcare providers that serve patients in good faith through everyday communications technologies, such as FaceTime or Skype…” In addition, states may have laws that exceed the requirements and may not necessarily have been waived during the pandemic.

Source: OCR Guidance on HIPAA.

Policy Recommendations

-

Providers

○ Stay apprised of policy changes during a pandemic.

○ Keep team informed/trained to stay compliant.

-

Policymakers

○ After PHE, remove enforcement discretion to reinstate pre-COVID HIPAA policies.

Remote Prescribing

Remote prescribing of drugs and controlled substances must comply with applicable state and federal requirements. The majority of states permit a physician to prescribe after a telehealth examination. To prescribe a controlled substance, providers must also navigate state practice laws, pharmacy board laws, state-controlled substance diversion laws, and federal laws and regulations under the Drug Enforcement agency (DEA). During the COVID-19 PHE, the DEA is allowing DEA registered practitioners to prescribe controlled substances to patients without having conducted an initial in-person medical evaluation, provided certain conditions are met20:

The prescription is issued for a legitimate medical purpose by a practitioner acting in the usual course of his/her professional practice.

The telemedicine communication is conducted using an audiovisual real-time two-way interactive communication system.

The practitioner is acting in accordance with applicable federal and state law.

In addition, the DEA is allowing practitioners to prescribe buprenorphine to new and existing patients with opioid use disorders through telephone without requiring practitioners to first conduct an examination of the patient in-person or through telehealth.21

Sources: (1) DEA; (2) DEA State License Requirements and (3) DEA Prescribing During COVID-19.

Policy Recommendations

-

Providers

○ Stay apprised of policy changes during a pandemic.

○ Keep team informed/trained to stay compliant.

-

Policymakers

○ Remove barriers to enable remote prescribing through telehealth at federal and state levels.

○ Make PHE policies permanent that enable remote prescribing of controlled substances through telehealth without an initial in-person examination.

○ Practitioners should be able to prescribe a legend drug based on a telehealth visit, including a controlled substance, if the practitioner is authorized to prescribe such legend drug under applicable state and federal laws and the prescription is issued for a legitimate medical purpose by a practitioner acting in the usual course of the practitioner's professional practice.

Other Policy Considerations

Health care providers must address these other policy, legal, and regulatory issues when providing health care through telehealth during a pandemic.

Consent

Health care providers furnishing telehealth services must have procedures in place to comply with varying payer rules and federal and state laws and regulations regarding patient consent and documentation in the record. During the COVID-19 PHE, CMS allows consent at the same time that the CTBS is being furnished. For RPM, CMS allows beneficiary consent to be obtained by auxiliary staff in addition to the billing clinician. These policies should be made permanent.

Source: Physicians and Other Clinicians: CMS Flexibilities to Fight COVID-19.

Supervision

Current rules allow general supervision to be performed virtually, whereas direct supervision requires the supervising clinician be on site with the billing clinician when the service is provided. Physician supervision requirements have traditionally been a barrier to the delivery of telehealth services. During the COVID-19 pandemic, CMS allows virtual direct supervision of incident-to and diagnostic services to be done through telehealth using real-time audio–video technologies. These policies should be made permanent.

Sources: (1) CMS COVID-19 FAQs (2) Physicians and Other Clinicians: CMS Flexibilities to Fight COVID-19.

Hospital Telehealth Credentialing/Privileging

CMS and the Joint Commission require hospitals to have a credentialing and privileging process in place for providers furnishing services to the hospital through telehealth. Federal regulations allow “credentialing by proxy” that allows the originating site hospital to rely on the privileging and credentialing decisions made by the distant site hospital or entity furnishing the telehealth services, provided certain requirements are met. The privileging process that involves verifying licenses and qualifications creates a barrier for telehealth providers who must go through the process at every health care organization for which they plan to provide services. CMS requires participating hospitals to maintain a “comprehensive emergency preparedness program” under its Conditions of Participation to address “…the use of volunteers in an emergency and other emergency staffing strategies, including the process and role for integration of State and Federally designated health care professionals to address surge needs during an emergency.” Hospitals that are accredited by the Joint Commission can refer to the Commission's standards for issuing temporary and disaster privileges, both of which should be addressed in accordance with the medical staff bylaws. Hospitals must also follow The Joint Commission, federal, and state requirements for focused professional practice evaluation/ongoing professional practice evaluation peer review processes, in accordance with the medical staff bylaws.

Sources: (1) Federal Code Governing Body Conditions of Participation, (2) Federal Code Medical Staff Conditions of Participation, and (3) Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC).

Telehealth Malpractice Insurance

Many insurers provide malpractice coverage for providers furnishing telehealth services to their patients; however, some plans expressly deny coverage. Since malpractice insurance is regulated at the state level, barriers exist for providers with multistate telehealth practices. Providers should confirm with their carriers that their current malpractice insurance covers services provided through telehealth and if the provider is practicing across state lines, that their coverage extends into the other state(s). Malpractice coverage should not exclude services provided through telehealth.

Source: Center for Connected Health Policy.

Crisis Standard Operating Procedures

Health care providers must comply with applicable state and federal laws and regulations, as well as CMS Conditions for Participation that require a comprehensive emergency preparedness program and Joint Commission requirements, as applicable. Health care providers should develop crisis standard operating procedures (SOPs) for the use of telehealth to prepare for any pandemic. Guidelines for clinical practice, training, and data collection for telehealth applications should be included.

Source: (1) Federal Code Governing Body Conditions of Participation and (2) Federal Code Medical Staff Conditions of Participation.

Fraud and Abuse

Telehealth arrangements involving federal health care program dollars must comply with applicable federal fraud and abuse laws such as the Anti-kickback and Stark laws. State-level fraud and abuse laws must also be followed. During the COVID-19 PHE, CMS issued blanket waivers of certain provisions in the Stark law regulations regarding remuneration and referrals related to COVID-19. Some states also took action during the pandemic. Policies that remove barriers to innovation and use of telehealth technologies should remain in place.

Source: Physicians and Other Clinicians: CMS Flexibilities to Fight COVID-19.

Medical Devices (FDA)

FDA regulates food, drugs, medical devices (i.e., includes definitions for both hardware and software), biologics, and a host of other products. During the COVID-19 PHE, FDA has supported development of medical countermeasures and provided regulatory advice, guidance, and technical assistance to advance the development and availability of vaccines, therapies, diagnostic tests, and other medical devices for use in diagnosing, treating, and preventing the coronavirus. FDA has also issued emergency use authorizations to provide more timely access to critical medical products. Providers must stay apprised of any related federal and state regulatory changes during the PHE. For example, during the COVID-19 PHE, CMS requires any device used for RPM to meet the FDA's definition of a medical device. Policies that remove barriers to innovation and use of telehealth technologies should remain in place.

Sources: (1) CMS COVID-19 FAQs, (2) FDA Medical Devices, and (3) FDA Digital Health.

Connectivity

Telehealth requires adequate telecommunications infrastructure over which remote services can be delivered to patients. Video-based services, store and forward services, and other mobile technologies require a range of bandwidths to transfer health care data for different applications. Adequate IT/broadband is also needed for distance education, teleworking, and other online services. As people sheltered in place during the COVID-19 crisis, it placed more reliance on technology in the home. Lack of affordable technology and broadband connectivity for many low-income families, seniors, and residents living in rural areas was exacerbated during this crisis and brought to light digital inequities that have always existed. Implementing a national IT/broadband infrastructure to close the digital divide is necessary for preparedness and emergency response in the next pandemic. Providing funding support for providers to build telehealth and telecommunications infrastructure will help create provider incentives to adopt and expand health care service delivery through telehealth. Eliminating cost-sharing requirements (e.g., co-payments) or offering other financial incentives to patients could help encourage use of telehealth and enable access to care for vulnerable and at-risk populations during or before a pandemic.

Sources: (1) FCC and (2) FCC's Connected Care Pilot.

Transportation

The transportation and logistics industry performs vital services in today's modern globalized interconnected world. The COVID-19 PHE demonstrated the need for creative solutions to address transportation/distribution of supplies (e.g., drones to deliver medications regulated by the Federal Aviation Administration) and health care delivery outside the hospital walls (e.g., through telehealth or wherever the patient is located). Providers need to be aware of relevant federal, state, and local requirements or regulatory changes issued during a pandemic. Pandemic preparedness requires a coordinated effort involving government, private sector, and other stakeholders. Telemedicine eliminates the need for patient transportation and, in many cases, provider transportation as well (e.g., policies allowing emergency medical services personnel to provide health care at the patient's home or through telehealth would help divert patients from being transported to the hospital emergency department and spread of the virus, e.g., CMS Emergency Triage, Treat and Transport model, ET3.).

Sources: (1) FAA Unmanned Aircraft Systems and (2) CMS ET3 Model.

Surveillance/Reporting

Public health surveillance and reporting are essential tools for decision-makers to lead and manage effectively in a pandemic. However, inadequate funding for resources and critical infrastructure at both federal and state levels, a lack of standardized data collection methodologies, politicization of public health, and other challenges have hindered public health's response during the COVID-19 pandemic. Changes are needed to strengthen the nation's public health surveillance and reporting functions to protect and improve public health during any pandemic. Standards, systems and infrastructure for electronic collection, reporting, and data sharing are critical in an effective pandemic response.

Sources: (1) CDC Public Health Professionals Gateway, (2) Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB), and (3) Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC).

Recommendations for Section E: Other Policy Considerations

Providers

Industry to create standardized terminology, evidence-based practice guidelines for use cases/modalities to ensure quality care/patient safety during a pandemic.

Stay apprised of federal, state, and local policy changes during a pandemic.

Keep team informed/trained to stay compliant.

Integrate telehealth into day-to-day delivery of care.

Policymakers

Remove barriers/restrictions placed on telehealth to incentivize adoption, improve access to care and preparedness for future pandemics.

Remove administrative barriers/streamline credentialing and enrollment procedures.

-

Crisis SOPs

○ Make the implementation of telehealth capabilities a required element of hospital emergency preparedness programs.

○ Provide opportunities for funding telehealth infrastructure.

-

Connectivity

○ Establish national pandemic response preparedness effort to implement telecommunications infrastructure for remote health care delivery/telehealth, remote work (teleworking), and remote education (remote classrooms).

○ Upgrade the nation's IT and broadband infrastructure, which has remained unresolved for decades.

○ Solve access inequity and the digital divide.

○ Stimulate the economy and economic capabilities of the country.

○ Create jobs in building out this infrastructure.

○ Significantly improve national preparedness and flexibility for the next pandemic.

-

Transportation

○ Establish policies that remove barriers to health care through telemedicine.

○ Allow EMS personnel to provide emergency health care services at the patient's home or through telehealth instead of bringing the patient to the hospital ED.

-

Surveillance/reporting

○ Increase funding for public health at the federal, state, and local levels as a sustainable function across the nation.

○ Fund and implement critical infrastructure to modernize systems, technologies for the collection/reporting of public health data.

○ Set national data collection standards.

○ Expand data collection beyond the ED to modern care entry points (urgent care, convenience clinics, online on-demand telehealth, etc.).

○ Depoliticize the role of public health agencies, information disseminated, and so on.

○ Establish meeting rules to reduce public health meeting disruption and to address threats against public health officials.

Conclusions

Provider adoption of telehealth services before the COVID-19 pandemic was very low due to legacy legislative and regulatory restrictions on coverage and payment of services. As policymakers removed these constraints on payment during the PHE, adoption skyrocketed. To prepare for any future pandemic, sustained adoption of telehealth is needed. Therefore, it is the opinion of the members of this Think Tank that permanent policy changes that allow broad coverage and payment of telehealth services, as well as cross-state licensing reforms are essential to incentivize providers to continue to invest in national telehealth and telecommunications infrastructure. Policies that enable coverage and payment parity for telehealth services should be implemented in the short term beyond the PHE to allow sufficient time for adoption of telehealth services to become sustainable and data collection from which to base payment policy changes in the future.

Building national infrastructure for providers to deliver telehealth services will also provide the necessary framework to keep businesses in operation, provide distance education, and for other purposes during any future pandemic. Furthermore, a national infrastructure will foster health care and digital equity and transformation of the health care system from fee-for-service to value-based care.

Mapping Topic Areas to Policy, Legal & Regulatory Considerations During a Pandemic (Supplementary Table ST1 and Supplementary Data S1).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Center for Connected Health Policy provided source materials and feedback for the policy section in this Plan. This document does not represent the opinion of Health Resources and Services Administration, Federal Office of Rural Health Policy, Office for the Advancement of Telemedicine, the Telemedicine Resource Centers or any other grant funded entity. It comprises suggestions and opinions of experts in the fields of telehealth, epidemiology, public health, nursing, hospital administration and policy/regulatory who worked together to comprise this Action Plan for a Pandemic response. For more information regarding this publication, or to learn more about telehealth, please contact TTAC at www.telehealthtechnology.org, or your regional Telehealth Resource Center or the National Policy Telehealth Resource Center. The 12 regional and 2 national Telehealth Resource Centers (TRCs) provide assistance, education, and information to organizations and individuals who are actively providing or interested in providing health are at a distance. You can find your regional or national Telehealth Resource Center through the National Consortium of Telehealth Resource Centers (NCTRC), which comprises all 14 Telehealth Resource Centers. The NCTRC website is www.telehealthresourcecenter.org.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This publication (report, briefing paper, document, etc.) was made possible by grant number GA5RH37463 from the Office for the Advancement of Telehealth, Health Resources and Services Administration, DHHS.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Totten AM, Hansen RN, Wagner J, et al. Comparative Effectiveness Review Number 216. AHRQ Publication No. 19-EFC012-EF, 2019. Available at https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/cer-216-telehealth-final-report.pdf (last accessed December 28, 2020).

- 2. Yang NH, Dharmar M, Yoo BK, Leigh JP, et al. . Economic evaluation of pediatric telemedicine consultations to rural emergency departments. Med Decis Making 2015;35:773–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Narasimhan M, Druss BG, Hockenberry JM, et al. . Impact of a telepsychiatry program at emergency departments statewide on the quality, utilization, and costs of mental health services. Psychiatr Serv 2015;66:1167–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grabowski DC, O'Malley AJ. Use of telemedicine can reduce hospitalizations of nursing home residents and generate savings for Medicare. Health Affairs 2014;33:244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Available at https://www.jdpower.com/system/files/legacy/assets/2019212%2520U.S.%2520Telehealth%2520Study.pdf (last accessed December 28, 2020).

- 6. U.S. Government Accounting Office, GAO. Health Care: Telehealth and Remote Patient Monitoring Use in Medicare and Selected Federal Programs. 2017-365. Available at www.gao.gov/assets/690/684115.pdf (last accessed December 28, 2020).

- 7. Brooks E, Turvey C, Augusterfer EF. Provider barriers to telemental health: obstacles overcome, obstacles remaining. Telemed J E Health 2013;19:433–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. HealthcareDive. Available at www.healthcaredive.com (last accessed December 28, 2020).

- 9. FairHealth. Available at https://www.fairhealth.org/states-by-the-numbers/telehealth (last accessed December 28, 2020).

- 10. Center for Connected Healthcare Policy. Available at www.cchpca.org (last accessed December 28, 2020).

- 11. Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services. Available at https://www.medicaid.gov/resources-for-states/downloads/medicaid-chip-beneficiaries-COVID-19-snapshot-data-through-20200630.pdf (last accessed December 28, 2020).

- 12. US Congress. Available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1892 (last accessed December 28, 2020).

- 13. US Congress. Available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/6 (last accessed December 28, 2020).

- 14. Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services. Available at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-General-Information/Telehealth (last accessed December 28, 2020).

- 15. Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services. Available at https://www.cms.gov/files/document/03092020-covid-19-faqs-508.pdf (last accessed December 28, 2020).

- 16. Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services. Available at https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models#views=models (last accessed December 28, 2020).

- 17. Center for Connected Healthcare Policy. Available at https://www.cchpca.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/CCHP_%2050_STATE_REPORT_SPRING_2020_FINAL.pdf (last accessed December 28, 2020).

- 18. Center for Connected Healthcare Policy. Available at https://www.cchpca.org/sites/default/files/2019-02/TELEHEALTH%20POLICY%20BARRIERS%202019%20FINAL.pdf (last accessed November 1, 2020).

- 19. Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services. Available at https://www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf (last accessed December 28, 2020).

- 20. US Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration, Diversion Control Division. Available at https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/coronavirus.html (last accessed November 1, 2020).

- 21. US Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration, Diversion Control Division. Available at https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/GDP/(DEA-DC-022)(DEA068)%20DEA%20SAMHSA%20buprenorphine%20telemedicine%20%20(Final)%20+Esign.pdf (last accessed November 1, 2020).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.