Abstract

Background

Limited real-world data exist on the effectiveness and safety of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone (abiraterone hereafter) in the treatment of patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) naive to chemotherapy. Most of the few available studies had a retrospective design and included a small number of patients. In the interim analysis of the ABItude study, abiraterone showed good clinical effectiveness and safety profile in the chemotherapy-naive setting over a median follow-up of 18 months.

Patients and methods

We evaluated clinical and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) of chemotherapy-naive mCRPC patients treated with abiraterone as for clinical practice in the Italian, observational, prospective, multicentric ABItude study. mCRPC patients were enrolled at abiraterone start (February 2016-June 2017) and followed up for 3 years; clinical endpoints and PROs, including quality of life (QoL) and pain, were prospectively collected. Kaplan–Meier curves were estimated.

Results

Of the 481 patients enrolled, 454 were assessable for final study analyses. At abiraterone start, the median age was 77 years, with 58.6% elderly patients and 69% having at least one comorbidity (57.5% cardiovascular diseases). Visceral metastases were present in 8.4% of patients. Over a median follow-up of 24.8 months, median progression-free survival (any progression reported by the investigators), time to abiraterone discontinuation, and overall survival were, respectively, 17.3 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 14.1-19.4 months], 16.0 months (95% CI 13.1-18.2 months), and 37.3 months (95% CI 36.5 months-not estimable); 64.2% of patients achieved ≥50% reduction in prostate-specific antigen. QoL assessed by Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Prostate, the European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Level, and European Quality of Life Visual Analog Scale remained stable during treatment. Median time to pain progression according to Brief Pain Inventory data was 31.1 months (95% CI 24.8 months-not estimable). Sixty-two patients (13.1%) had at least one adverse drug reaction (ADR) and 8 (1.7%) one serious ADR.

Conclusion

With longer follow-up, abiraterone therapy remains safe, well tolerated, and active in a large unselected population.

Key words: abiraterone acetate, metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, prospective study, real-world evidence

Highlights

-

•

A prospective real-life study of abiraterone acetate in mCRPC patients.

-

•

In 481 chemotherapy-naive mCRPC patients (median follow-up: 25 months), abiraterone plus prednisone was effective and safe.

-

•

QoL, measured with various tools, remained stable during treatment with abiraterone plus prednisone.

-

•

The median time to pain progression was 31.1 months.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second most frequent cancer in men.1 At early stages, it has an extremely favorable prognosis (5-year survival rate approaching 100%), but it remains a lethal disease when metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) develops.2

Since 2011, considerable progress has been made in the treatment of mCRPC, including the approval of multiple agents showing benefit in terms of survival in landmark phase III trials.3,4 Particularly, the enhanced understanding of the central role of androgen receptor (AR) pathway in prostate cancer cells has led to the development of novel AR-axis targeted therapies,5 which have become first-line options in the treatment of mCRPC patients.6

Abiraterone acetate is a prodrug of abiraterone, which is a CYP17A1 inhibitor blocking androgen production in the adrenals and testes as well as in prostate cancer cells.7 Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone/prednisolone (hereafter referred to as abiraterone) was initially approved by the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of mCRPC patients treated with docetaxel (2011)8,9 and subsequently (2013) for those naive to chemotherapy.10, 11, 12 In the COU-AA-302 randomized trial of chemotherapy-naive asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic mCRPC patients, abiraterone plus low-dose prednisone significantly delayed radiographic progression, clinical decline, and chemotherapy initiation, and improved health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and pain outcomes compared to placebo plus prednisone.10,11,13 Moreover, the final trial analysis at a median follow-up of 49 months demonstrated a significant improvement in the overall survival (OS).

Little is known about the effectiveness of first-line abiraterone for mCRPC outside the controlled clinical trial setting. Indeed, while some real-life investigations have explored the issue,14,15 these were mostly retrospective and included a relatively small number of patients. In addition, the impact of mCRPC treatments, including abiraterone, on tumor-related perceived symptoms and HRQoL under real-world conditions has been scantily reported.

The A prospective oBservatIonal sTUdy of patients with metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer progressing after stanDard hormonal therapy suitable for abiraterone acetate trEatment (ABItude) is a multicentric, observational, and prospective study with 36 months follow-up including over 450 mCRPC patients starting first-line abiraterone as per clinical practice after androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) failure. Collecting prospectively hard oncologic endpoints and relevant patient-reported outcomes (PROs) on a large cohort of unselected patients, it represents a unique opportunity to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of abiraterone in the treatment of chemotherapy-naive mCRPC patients in routine clinical practice. Results from interim analyses at 18 months16 of median follow-up showed favorable patient outcomes and no safety-related concerns. Herein, we have reported the final 36-month results of the ABItude study.

Patients and methods

ABItude is an Italian, multicentric, observational, prospective study of mCRPC patients progressing after standard hormonal therapy with ADT, starting a first-line treatment with abiraterone as for clinical practice.16 Enrollment took place between February 2016 and June 2017 in 49 participating Italian sites (urological, radiotherapy, and oncological units). Main selection criteria were as follows: men aged ≥18 years with histologically confirmed metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate, naive to chemotherapy, asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic according to clinical judgment, surgically or medically castrated, who had progressed on ADT, and in whom chemotherapy was not clinically indicated. Patients had to start treatment with abiraterone within 30 days after the baseline visit as for clinical practice. Patients already treated in all stages with chemotherapy for prostate cancer or participating in experimental clinical trials were excluded.

Patients were followed up for a 36-month period regardless of abiraterone treatment interruption. Data were collected around every 6 months, but the assessment was carried out as clinically indicated. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and principles of good clinical practice, with the approval of the ethics committees of all participating centers. All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study before any study-related procedures.

Demographic and clinical data were extracted mainly from medical records and entered in an electronic case report form. At screening visit, the following information was collected: demographic and anthropometric characteristics, relevant medical history, and historical data on prostate cancer, including previous prostate cancer treatments. Details on abiraterone and prednisone treatments, subsequent therapies to abiraterone (if any), concomitant therapies (including analgesic and opioid use), vital signs, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), prostate-specific antigen (PSA) measurements, clinical and radiographic disease progression, treatment adherence, adverse events (AEs), and survival details were recorded during the observation period. In particular, PSA measurement and imaging were carried out at the discretion of the treating physician, at variable timing. Furthermore, data on patient-reported pain and on HRQoL at baseline and during the observation period were collected every 6 months. The pain score was evaluated using the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), which measures pain intensity and interference of pain with daily living activities (e.g. sleep, mood, and activity); it includes several individual items rated on a scale from 0 (‘no pain’) to 10 (‘pain as bad as you can imagine’). ‘Pain intensity’ is the arithmetic mean of the scores on the four items related to maximum, minimum, mean, and present pain intensity; ‘pain interference’ is the arithmetic mean of the scores on the seven items relating to interference of pain with activities of daily living; ‘worst pain intensity’ is the scored value of the maximum pain intensity item.17 Pain intensity, pain interference, and worst pain intensity range from 0 to 10, with higher scores for greater pain. Asymptomatic patients were those with a baseline score of 0-1 on the worst pain item of the BPI, mildly symptomatic those with a score of 2-3, and symptomatic those with a score >3.13 Increased pain intensity, worst pain, and pain interference during treatment with abiraterone were defined according to score changes previously shown to be clinically relevant to patients, as in Basch et al.13 HRQoL was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Prostate (FACT-P) and the European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Level (EQ-5D-3L) instrument. FACT-P measures patient’s functional status during the past 7 days.18 The questionnaire includes the 27-item FACT—general (FACT-G) questionnaire [4 domains, i.e. physical (7 items), social or family (7 items), emotional (6 items), and functional well-being (7 items)], which measures HRQoL in cancer patients, and a 12-item prostate cancer subscale, designed to measure prostate cancer-specific HRQoL. Each item is rated from 0 (‘not at all’) to 4 (‘very much’). The FACT-P total score is calculated by summing up scores of all the items; it thus ranges from 0 to 156, with higher scores representing better HRQoL. The FACT-G score is computed as the sum of the scores on the physical, social or family, emotional, and functional domains (range: 0-108). The EQ-5D-3L is a non-cancer-specific measure of generic health status including a descriptive system of five dimensions (i.e. mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression), each with three levels of functioning (e.g. no problems, some problems, and extreme problems).19 A unique health index score is calculated through an algorithm that attaches coefficients to each of the levels in each dimension; we used the Italian model to estimate the EQ-5D-3L index score.20 In addition, the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire includes a visual analog scale (EQ VAS) which measures the patient’s overall health status from 0 (worse imaginable health) to 100 (best imaginable health).

Adherence to treatment with abiraterone was evaluated by means of the ©Morisky Medication Adherence Scale eight-item version (MMAS-8),21, 22, 23 the Italian version of which has been linguistically validated.24 It is a generic self-reported, medication-taking behavior scale, validated for hypertension but used for a wide variety of medical conditions. The score ranges from 0 to 8, with higher scores for higher medication adherence.21,22 Low, medium, and high medication adherence were defined as an MMAS-8 score of <6, 6-7, and 8, respectively.21

Permission to use the MMAS-8 scale was granted by Donald Morisky, the copyright holder of the instrument. Patients were administered with this questionnaire until on treatment with abiraterone.

This report followed the ‘Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology’ guidelines for reporting.25

Statistical analysis

Radiographic progression-free survival (rPFS) on abiraterone treatment was defined as the time from abiraterone treatment initiation to radiographic progression or death, whichever occurred first. PFS considering any progression reported by the investigator, including biochemical, radiographic, and clinical progression, or death was also defined. Events that occurred during abiraterone treatment and within 30 days from abiraterone discontinuation were considered. For patients alive and without signs of progression during abiraterone treatment, rPFS/PFS was defined as the time from abiraterone treatment initiation to the last follow-up carried out during the treatment (patients were censored at abiraterone discontinuation). OS was defined as the time from abiraterone treatment start to patient’s death from any cause. PSA response was defined as a decline in PSA >50% from baseline during abiraterone treatment.

For the BPI, FACT-P, and EQ-5D-3L data, only questionnaires completed while the patient was still on treatment with abiraterone were considered. Using established meaningful change thresholds, time to pain progression was computed as the time from abiraterone treatment initiation to the increase in pain intensity, worst pain, or pain interference, whichever came first.

For the safety analysis, AEs that occurred starting from abiraterone treatment until 30 days after drug permanent discontinuation were considered. AEs that occurred after starting a subsequent treatment for mCRPC were not evaluated.

Continuous variables were presented as mean values ± standard deviations or median values (interquartile ranges), and categorical variables were reported as numbers and percentages. Survival curves for rPFS, PFS, OS, and pain progression were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. The median time to event, with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI), and the 1- and 2-year probability of surviving were also calculated.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of the 481 mCRPC patients suitable for abiraterone treatment enrolled in the ABItude study, 474 receiving at least one dose of abiraterone were included in the safety analysis set; 454 patients with no violation of the eligibility criteria were included in the analyses on drug effectiveness (Supplementary Figure S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100431). Of them, 332 (73.1%) were recruited in oncology, 64 (14.1%) in urology, and 58 (12.8%) in radiotherapy sites. Most patients received medical castration (94%), while a small fraction underwent surgical castration (6%). Prior treatment for mCRPC included ADT (93%), radiotherapy (17%), and surgery (8%). In 26% of cases, the decision to treat patients with abiraterone was discussed and taken by a multidisciplinary team.

At abiraterone start, the median age was 77 years (q1-q3: 71-82 years), and 58.6% of patients were ≥75 years old (Table 1). About 42% of patients had bone metastases only and 22% lymph node metastases only; visceral metastases were detected in 8.4% of patients. Among patients with bone metastases, about 22% had 10 or more lesions. The large majority of patients (94.8%) had ECOG PS of 0 or 1. Comorbidities were frequently detected, with cardiovascular disorders (stable and well compensated) reported in 57.5% of patients; metabolic conditions and disorders of the central nervous system were observed in 23.1% and 5.3% of patients, respectively. Median (q1-q3) baseline FACT-P, EQ-5D-3L, and EQ VAS scores were, respectively, 110 (95-120), 0.9 (0.8-1.0), and 70 (50-80).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical patients’ characteristics at baseline

| Patients (n = 454) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Median (q1-q3) | 77 (71-82) |

| ≥75 years, n (%) | 266 (58.6) |

| Gleason score ≥8 at tumor diagnosisa | 233 (59.0) |

| Metastasis at first prostate cancer diagnosis,bn (%) | 65 (14.3) |

| Time from first prostate cancer diagnosis to abiraterone (years), median (q1-q3) | 5.2 (2.2-9.3) |

| Time from castration to abiraterone (years), median (q1-q3) | 2.9 (1.1-6.0) |

| Time from mCRPC to abiraterone (months), median (q1-q3) | 1.6 (1.0-2.9) |

| PSA (ng/ml) at baseline, median (q1-q3) | 15.3 (5.0-44.1) |

| Location of metastases at baseline visit, n (%) | |

| Bone metastases only | 190 (41.9) |

| Lymph node metastasis only | 100 (22.0) |

| Bone + lymph node metastasis only | 103 (22.7) |

| At least one visceral metastasis | 38 (8.4) |

| Other | 23 (5.1) |

| No. of bone metastases at baseline visit,cn (%) | |

| 1-3 | 114 (39.6) |

| 4-9 | 111 (38.5) |

| ≥10 | 63 (21.9) |

| Not available | 32 |

| ECOG PS at baseline, n (%) | |

| 0 | 251 (56.8) |

| 1 | 168 (38.0) |

| ≥2 | 21 (4.8) |

| Not available | 12 |

| No. of comorbidities, n (%) | |

| 0 | 142 (31.3) |

| 1 | 139 (30.6) |

| ≥2 | 173 (38.1) |

| Type of comorbidity,dn (%) | |

| Cardiovascular disorders | 261 (57.5) |

| Hypertension | 221 (48.7) |

| History of myocardial infarction | 25 (5.5) |

| Arrhythmia | 20 (4.4) |

| Metabolic disorders | 105 (23.1) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 52 (11.5) |

| Diabetes | 49 (10.8) |

| CNS disorders | 24 (5.3) |

| Renal disorders | 16 (3.5) |

| Hepatic disorders | 9 (2) |

| Other disorders | 94 (20.7) |

| Baseline FACT-P, median (q1-q3) | 110 (95-120) |

| Baseline EQ-5D-3L, median (q1-q3) | 0.9 (0.8-1.0) |

| EQ VAS, median (q1-q3) | 70 (50-80) |

| BPI item #3 (worst pain intensity) | |

| 0-1 | 195 (50.0) |

| 2-3 | 70 (17.9) |

| >3 | 125 (32.1) |

| Not available | 64 |

BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; CNS, central nervous system; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; EQ-5D-3L, European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Level; EQ VAS, European Quality of Life Visual Analog Scale; FACT-P, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Prostate; mCRPC, metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Information not available for 59 patients.

Information not available for nine patients.

Percentages were calculated over the number of patients with bone metastases.

Patient could have more than one medical condition.

The median follow-up of patients was 24.8 months (q1-q3: 12.7-35.1 months).

Treatment exposure and compliance

The median time from the diagnosis of prostate cancer to abiraterone start was 5.2 years (q1-q3: 2.2-9.3 years); 25% of patients started abiraterone 2.9 months after the diagnosis of mCRPC. The drug was administered together with corticosteroids, typically prednisone (99.1%); in a few cases, dexamethasone or methylprednisolone was preferred.

Three hundred and thirty-four patients (73.6%) permanently discontinued the drug during the study period: 219 patients (65.6%) for disease progression, 17 patients (5.1%) for adverse drug reaction (ADR), 16 patients (4.8%) for own choice, and 67 (20.1%) for other reasons not related to the drug (reason for permanent discontinuation was not available for 15 patients, i.e. 4.5%). Of the 334 patients who discontinued abiraterone, 176 received second-line therapy for mCRPC within the study: 126 subjects received cytotoxic chemotherapy (median duration: 7.2 months), 29 enzalutamide (median duration: 7.1 months), and 21 patients other therapies. Of the remaining 158 patients, 152 withdrew prematurely from the study after drug interruption (including 79 patients who died and 49 who were lost to follow-up) and 6 reached the end of study on abiraterone.

According to the MMAS-8 scale, the proportion of patients with low adherence to abiraterone therapy was 5.5% (18 out of 331 with available information) at 6, 5.4% (12/222) at 12, 10.3% (14/138) at 18, 6.9% (7/101) at 24, 1.4% (1/73) at 30, and 0% (0/40) at 36 months.

Clinical effectiveness

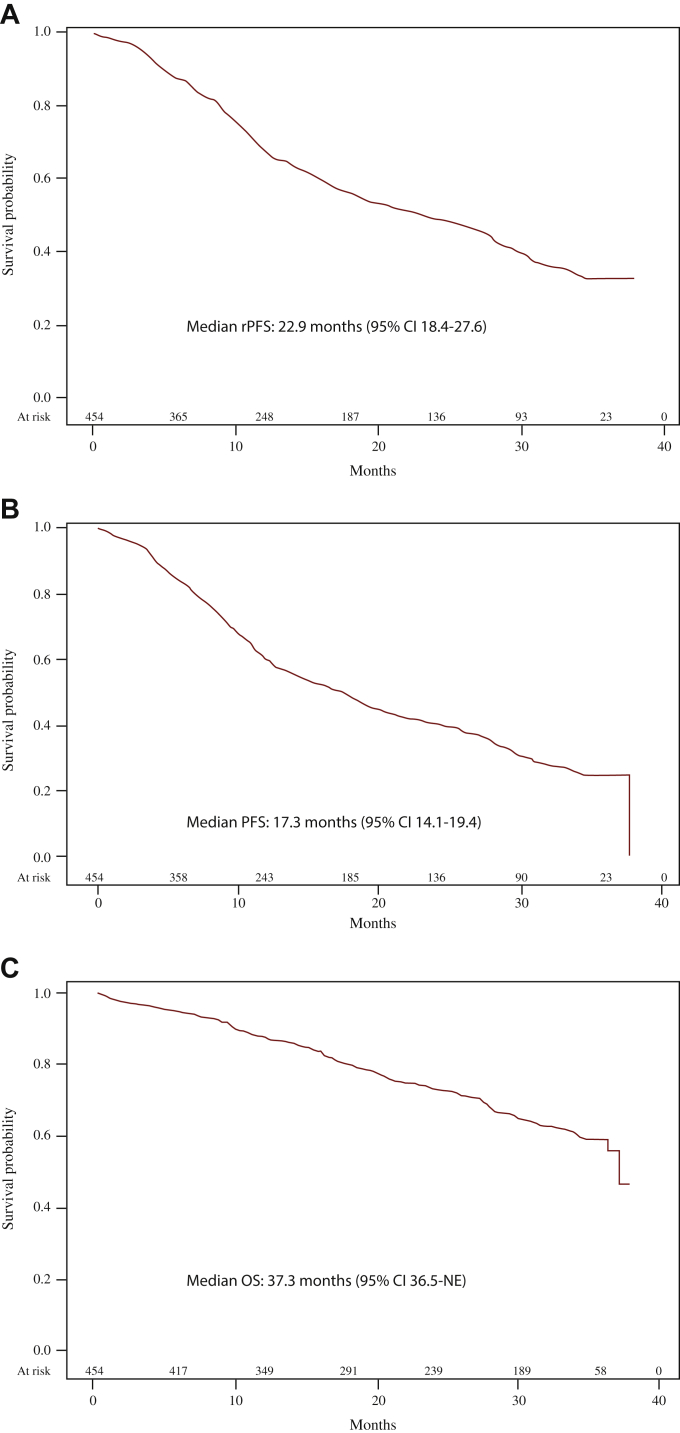

Median rPFS was 22.9 months (95% CI 18.4-27.6 months), and 1- and 2-year rPFS rates were 67.3% and 48.5%, respectively (Figure 1A). Corresponding values for PFS were 17.3 months (95% CI 14.1-19.4 months), and 59.6% and 40.0%, respectively (Figure 1B). In subgroup analyses, rPFS was similar in patients <75 years of age (median time: 23.2 months) and in those ≥75 years of age (22.6 months), in patients with (21.8 months) and without (23.2 months) cardiovascular comorbidities, and in patients with (20.7 months) and without (23.7 months) metabolic conditions. Estimated median time to abiraterone discontinuation was 16 months (95% CI 13.1-18.2 months).

Figure 1.

Clinical effectiveness of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone for the treatment of patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) naive to chemotherapy.

Radiographic progression-free survivala (rPFS) (A), PFSa (B), and overall survival (OS) (C) in the ABItude study.

CI, confidence interval; NE, not estimable.

aDuring abiraterone treatment.

One hundred and forty-seven patients died during the observation period; median OS was 37.3 months (95% CI 36.5 months-not estimable), and the estimated survival was 87.2% at 1 year and 73.3% at 2 years (Figure 1C). A PSA response (≥50%) during abiraterone treatment was achieved by 272 patients (64.2% of 424 patients with available information; 59.9% of all 454 patients enrolled in the study).

During abiraterone treatment, 22 patients received denosumab, 33 zoledronic acid, 3 alendronate, 1 pamidronate, 49 vitamin D supplementation, and 22 calcium; 23 (5.1%) patients had skeletal-related events (including 11 patients with pathological fractures, 8 requiring bone radiation, and 1 receiving surgery to bone). Eleven patients (2.4%) developed new visceral metastases in the course of treatment.

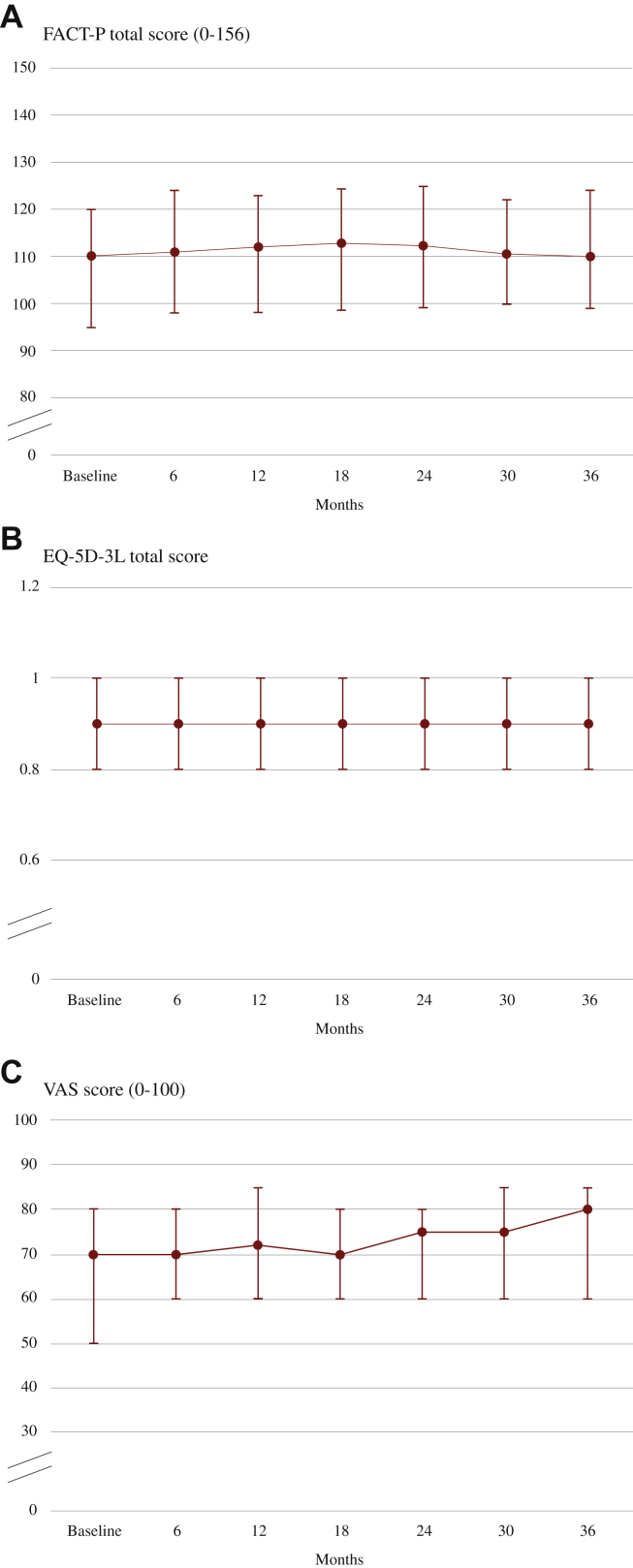

Quality of life, pain, and opiate use

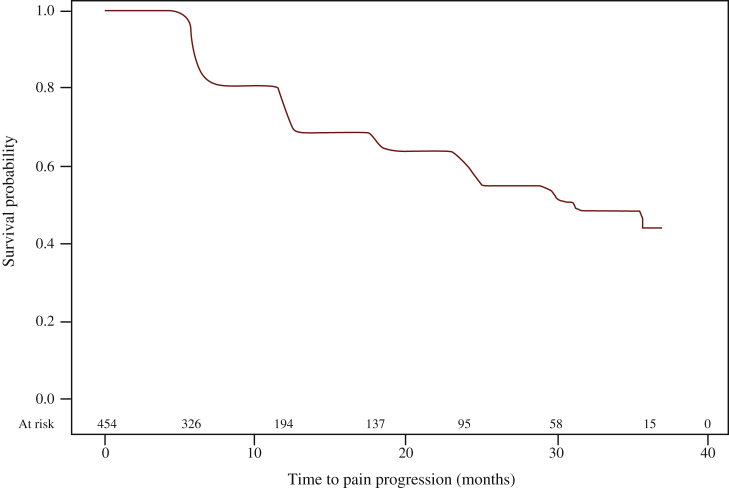

The total scores for FACT-P, EQ-5D-3L, and EQ VAS remained stable during treatment with abiraterone (Figure 2). Similar stable trends were observed for FACT-G and FACT-P subdomain scores (data not shown). Based on BPI data, 107 patients (23.6%) reported increased pain intensity, 102 (22.5%) increased worst pain intensity, and 83 (18.3%) increased pain interference during treatment with abiraterone. Median time to pain progression during abiraterone treatment was 31.1 months (95% CI 24.8 months-not estimable; based on 135 events of any type of pain progression) (Figure 3). Twenty-seven patients (6.3% of those naive to opiates) started opiate therapy for cancer-related pain while in treatment with abiraterone.

Figure 2.

Quality of life for abiraterone acetate plus prednisone.

Median (IQR) FACT-P total (A), EQ-5D-3L (B), and EQ VAS scores (C) during treatment with abiraterone.

EQ VAS, European Quality of Life Visual Analog Scale; EQ-5D-3L, European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Level; FACT-P, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Prostate; IQR, interquartile range.

Figure 3.

Time to pain progression during abiraterone treatment.

Safety

Among the 474 patients evaluated for safety, 244 (51.5%) had at least one AE and 93 (19.6%) at least one serious AE during abiraterone treatment. Sixty-two patients (13.1%) developed AEs related to abiraterone according to clinical judgment (a total of 94 events); eight patients (1.7%) had a serious ADR. Table 2 shows details of AEs occurred in >3% of the study sample according to severity.

Table 2.

Adverse events (AEs) occurred in >3% of patients during abiraterone treatmenta

| Total number of patients with AEs (n = 244) n (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Total | |

| Asthenia | 31 (12.7) | 5 (2.0) | 2 (0.8) | 38 (15.6) |

| Diarrhea | 17 (7.0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (7.4) |

| Edema | 13 (5.3) | 5 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (6.6) |

| Fatigue | 12 (4.9) | 3 (1.2) | 1 (0.4) | 16 (6.6) |

| Fever | 13 (5.3) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 16 (6.6) |

| Anemia | 9 (3.7) | 4 (1.6) | 3 (1.2) | 15 (6.1) |

| Dyspnea | 11 (4.5) | 4 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (6.1) |

| Nausea | 10 (4.1) | 4 (1.6) | 1 (0.4) | 13 (5.3) |

| Cough | 10 (4.1) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (4.5) |

| Constipation | 7 (2.9) | 3 (1.2) | 1 (0.4) | 10 (4.1) |

| Pain | 9 (3.7) | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (4.1) |

| Death unexpected | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (3.7) | 9 (3.7) |

Including AEs with onset within 30 days after abiraterone permanent discontinuation.

Discussion

Using an unselected cohort of patients from several oncology, urology, and radiotherapy sites across Italy, the final analysis of the ABItude study over a 36-month study period showed the real-world effectiveness and safety of abiraterone for the treatment mCRPC patients naive to chemotherapy, confirming results from the interim analysis.16

The favorable results of first-line abiraterone in men with mCRPC emerged in previous relatively small retrospective real-life investigations26, 27, 28, 29, 30 are here confirmed in a prospective large study with long follow-up.

In our real-life study, response to abiraterone treatment was comparable to that observed in the COU-AA-302 trial,10,12 despite the different patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics. Our patients were older (median age: 77 versus 71 years) and had a high burden of comorbidities; 8% of them had visceral metastases and 32% were symptomatic at baseline as per BPI (the trial excluded patients with visceral disease and symptomatic as per BPI). Despite such poor conditions, the median OS was ∼37 months in the present study and 34.7 months in the COU-AA-302 trial.12 rPFS in the ABItude was even greater than that observed in the trial (i.e. median time: 16.5 months).10 Our rPFS is likely to be overestimated due to missing imaging data on almost half of our patients over the study period. When we considered any progression as per physician’s definition, the median PFS decreased to 17.3 months, in line with that estimated in the trial. The observation that treatment duration is more similar to PFS than rPFS indicates that not only radiographic imaging but also other clinical data support clinicians in therapeutic choices in their everyday practice. Moreover, the proportion of patients achieving a >50% PSA decline in the present study was 64%, very similar to that observed in the interventional trial (i.e. 62%).

As disease progresses and metastases spread, many patients with mCRPC experience skeletal-related events, with subsequent pain and HRQoL deterioration. Pain is a significant predictor of OS in mCRPC.31 The Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group 3 underscored the importance of reporting patient experience in prostate cancer studies.32 PRO assessment, including self-reported symptom burden and HRQoL, has been well established in prostate cancer trials to complement efficacy and safety data,13,33 but PRO data in real-life setting are scant. Collecting PRO data prospectively, the ABItude study has allowed to explore patients’ perspective on their HRQoL and cancer-related pain during treatment. Here, we have reported that men with mCRPC naive to chemotherapy and treated with abiraterone preserve their HRQoL as measured by FACT-P score, EQ-5D-3L, and EQ VAS and experience slow pain progression. Time to pain progression in our study is consistent with data from the COU-AA-302 trial,13 despite 32% of our patients being already symptomatic at baseline based on BPI. In addition, only a small fraction of patients developed skeletal-related events and started opiate use for cancer pain during a median of 16 months of abiraterone treatment. Our results, therefore, highlight the value of abiraterone not only in terms of traditional oncologic outcomes, but also in terms of HRQoL preservation and palliative effects. Our findings support recent data from the large Canadian real-world Canadian Observational Study in Metastatic Cancer of the Prostate study.34 The study, which involved 254 mCRPC chemotherapy-naive patients starting abiraterone treatment, found that PROs, including FACT-P scores and pain assessed by BPI, were well maintained throughout the 72-week study period. Favorable HRQoL and pain outcomes have been described for other mCRPC therapies, including enzalutamide and radium-223.35 In the final 12-month analyses of the AQUARiUS observational study36 and in a two-phase trial with a 24-week study timeframe, PROs among chemotherapy-naive mCRPC patients favored abiraterone over enzalutamide.37 Conversely, Salem et al. found similar symptom-perceived burden in mCRPC men treated first line with abiraterone and enzalutamide.38

The effectiveness of self-administered oral medications relies on patients’ adherence to dosing and administration patterns. Despite the older age and high burden of comorbidities, in our study the rate of therapy compliance, as assessed by the MMAS-8 scale, was high across all assessment time points, and a small fraction of patients interrupted abiraterone for reasons other than disease progression or lack of clinical benefits. Such results suggest that non-adherence to abiraterone is not a relevant issue when treating mCRPC patients. Previous studies found favorable rates of medication adherence for abiraterone39, 40, 41 as well as for other anti-androgens.41,42

We reported a relatively low use of bone-protecting agents in spite of over 60% of patients with bone metastases. This observation is likely explained by the fact that recommendations from international scientific societies on the use of bone-protective agents in mCRPC patients were delivered in the final period of the study (in particular, those from the Italian Association of Medical Oncology were published in 2019, after the end of the study) and by the time lag in implementing treatment guidelines into everyday clinical practice.

Abiraterone was safe and well tolerated in our elderly mCRPC patients with an elevated burden of comorbidities (including controlled cardiac disorders), with reported AEs mostly mild to moderate in severity. Overall, only 5% of the patients interrupted the drug due to AE, 13% had an AE related to the drug, and 1.7% a serious ADR. The rate of abiraterone discontinuation due to AE was 10% in the interim (median follow-up: 22 months)10 and 13% in the final analyses (median follow-up: 49 months)12 of the COU-AA-302 trial, and was 12.8% (95% CI 11.4% to 14.2%) in a meta-analysis including randomized clinical trials of abiraterone in different prostate cancer disease states.43 The safety of abiraterone treatment in mCRPC patients with underlying cardiac disorders/risk factors has been widely studied with reassuring results.44, 45, 46

The evolving management options for prostate cancer has increased the need for a deep collaboration between urologists, medical oncologists, and radiation therapists to optimize patient care.47 Although multidisciplinary management of advanced prostate cancer is endorsed and it is recommended by international committees and associations,48, 49, 50 a recent study suggested a lower (but increasing) rate of referral to a multidisciplinary team for prostate cancer, compared to other types of cancers, in clinical practice.51 We reported a prevalence of multidisciplinary specialist care of 26% in the ABItude, in which several sites across Italy have participated.52 To our knowledge, this is the first study providing an estimate of the proportion of (advanced) prostate cancer patients receiving multidisciplinary management within the Italian National Health System.

Our study was conducted before the approval of abiraterone for de novo high-risk metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC), following the results of the LATITUDE and STAMPEDE clinical trials.53,54 Besides abiraterone, other options currently exist in the guidelines for the treatment of mHSPC, including docetaxel chemotherapy, enzalutamide, and apalutamide; abiraterone will still be largely used in the mCRPC setting in patients who will receive other drugs in the hormone-sensitive state. Our results cannot be directly transferred into the mHSPC setting, but they contribute to understand the toxicity profile of the drug in the real-world setting.

Being one of the largest real-life prospective investigation of abiraterone treatment in mCRPC patients failing ADT, the ABItude study is an invaluable source of information on the effectiveness and safety of the drug in the chemotherapy-naive mCRPC setting under real-world conditions. Besides the prospective design, the long follow-up period, and the high number of enrolled patients, major study strengths include the inclusion of patients encountered in routine clinical practice from several oncology, urology, and radiotherapy sites across the country, which ensure the generalizability of the study findings to the mCRPC Italian patient population. An additional strength is the ad hoc prospective collection of hard oncologic endpoints and PROs through the observation period, including HRQoL, pain, and medication adherence. In the ABItude study, radiological imaging was carried out as per physician’s discretion, at variable timing, without any central radiological review. Since a considerable proportion of our real-world patients (46%) did not undergo any radiographic assessment during treatment with abiraterone, rPFS is likely to be overestimated. The use of a PFS endpoint considering any type of progression reported by the investigator (including radiographic progression) should have overcome the limitation.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the final long-term analysis of the large, prospective ABItude study confirmed that first-line abiraterone treatment has favorable oncologic outcomes and that it is safe and well tolerated in clinical practice in older mCRPC patients with heterogeneous characteristics, including underlying comorbidities.

Acknowledgements

Study design, site monitoring, data management, and statistical analysis were carried out by MediNeos (Modena, Italy) following the Italian rules. Thanks to Christian Amici, Rosalba Domanico, Fabio Ferri, Giovanni Fiori, Nicole Lanci, Alessandra Ori, Roberto Patanè, Chiara Pennati, Barbara Roncari, Saide Sala, Lucia Simoni, and Francesca Trevisan (MediNeos Observational Research, Modena, Italy). The authors also thank Carlotta Galeone, who provided medical writing services on behalf of Statinfo srl. Use of the ©MMAS is protected by US copyright laws. Permission for use is required. A license agreement is available from: Donald E. Morisky, ScD, ScM, MSPH, Professor, 294 Lindura Court, Las Vegas, NV 89138-4632, USA; dmorisky@gmail.com.

Funding

This study was funded by Janssen-Cilag SpA.

Disclosure

GP has an honoraria/consulting or advisory role for AZ, Bayer, BMS, Ipsen, Janssen, Merk, MSD, Pfizer, and Novartis. VEC is an Advisory Board member and speaker for BMS, Ipsen, Janssen, and Pfizer. RB has an honoraria/consulting or advisory role/speaker’s bureau for Bayer, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Novartis, Amgen, Roche, Pfizer, Janssen Cilag, and Bristol Mayer Squibb. SDP is an Advisory Board member and invited speaker for Novartis, Roche, Celgene, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Eisai, Lilly, Pfizer, and Gentili. PB is an employee of Janssen. The remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

P. Beccaglia, Email: pbeccagl@its.jnj.com.

ABItude Study Group:

Giuseppe Procopio, Vincenzo Chiuri, Giovanna Mantini, Roberto Maisano. Roberto Bordonaro, Saverio Cinieri, Sabrina Rossetti, Sabino De Placido, Mario Airoldi, Luca Galli, Donatello Gasparro, Giuseppe Mario Ludovico, Pamela Francesca Guglielmini, Daniele Santini, Emanuele Naglieri, Daniele Fagnani, Massimo Aglietta, Lorenzo Livi, Luigi Schips, Rodolfo Passalacqua, Michele Fiore, Rolando Maria D'Angelillo, Giovanni Luca Ceresoli, Stefano Magrini, David Rondonotti, Vincenzo Mirone, Maria Consiglia Ferriero, Alessandro Sciarra, Mirko Acquati, Francesco Boccardo, Giorgio Vittorio Scagliotti, Manlio Mencoboni, Ugo De Giorgi, Gennaro Micheletti, Gaetano Lanzetta, Donata Sartori, Paolo Carlini, Hector Josè Soto Parra, Michele Battaglia, Francesco Uricchio, Antonio Bernardo, Antonello De Lisa, Giuseppe Carrieri, Antonio Ardizzoia, Michele Aieta, Salvatore Pisconti, Paolo Marchetti, and Fabiola Paiar

Appendix—ABItude Study Group Members

Dott. Giuseppe Procopio (S.S. Oncologia Medica Genitourinaria, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milano)

Dott. Vincenzo Chiuri (U.O. Oncologia Medica, P.O. V. Fazzi, Lecce)

Dott.ssa Monica Giordano (Oncologia, A.O. Sant’ Anna, San Fermo della Battaglia)

Prof.ssa Giovanna Mantini (Radioterapia oncologica, Policlinico Gemelli, Roma)

Dott. Roberto Maisano (Oncologia, A.O. Bianchi Melacrino Morelli, Reggio Calabria)

Dott. Roberto Bordonaro (S.C. Oncologia Medica, ARNAS Garibaldi–Nesima, Catania)

Prof. Saverio Cinieri (Oncologia Medica, P.O. Antonio Perrino, Brindisi)

Dott.ssa Sabrina Rossetti (Oncologia Medica Uro Ginecologica, Istituto Nazionale Tumori Pascale, Napoli)

Prof. Sabino De Placido (Oncologia D.A.I. Medicina Clinica, A.O.U. Federico II, Napoli)

Dott. Mario Airoldi (S.C. Oncologia Medica 2, AOU Città della Salute e della Scienza, Torino)

Dott. Luca Galli (U.O. Oncologia Medica 2 Univ., A.O.U. Pisana, Pisa)

Dott. Donatello Gasparro (U.O.C. Oncologia Medica, Azienda Ospedaliera di Parma, Parma)

Dott. Giuseppe Mario Ludovico (Urologia, Ospedale Generale Regionale F.Miulli, Acquaviva delle Fonti)

Dott.ssa Pamela Francesca Guglielmini (S.C. Oncologia, Ospedale SS Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo, Alessandria)

Prof. Daniele Santini (Oncologia, Università Campus Bio Medico, Roma)

Dott. Emanuele Naglieri (SSD Oncologia Medica per la patologia toracica, Istituto Tumori Giovanni Paolo II, Bari)

Dott. Daniele Fagnani (S.C. Oncologia Medica, ASST Vimercate, Vimercate)

Prof. Massimo Aglietta (Oncologia Medica, FPO IRCCS Candiolo, Candiolo)

Prof. Lorenzo Livi (Radioterapia Oncologica, A.O.U. Careggi, Firenze)

Prof. Luigi Schips (Urologia, Ospedale S.Pio da Pietrelcina, Vasto)

Dott. Rodolfo Passalacqua (Oncologia, ASST Cremona, Cremona)

Dott. Michele Fiore (Radioterapia oncologica, Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico, Roma)

Prof. Rolando Maria D'Angelillo (U.O.C. Radioterapia, Policlinico Tor Vergata, Roma)

Dott. Giovanni Luca Ceresoli (Oncologia, Humanitas Gavazzeni, Bergamo)

Prof. Stefano Magrini (Istituto del Radio, ASST Spedali Civili, Brescia)

Dott. David Rondonotti (S.C.D.U. Oncologia Medica, A.O.U. Maggiore della Carità, Novara)

Prof. Vincenzo Mirone (Clinica Urologica, A.O.U. Federico II, Napoli)

Dott.ssa Maria Consiglia Ferriero (S.C. Urologia Oncologica, I.F.O. Regina Elena, Roma)

Prof. Alessandro Sciarra (Urologia, Policlinico Umberto I Univ La Sapienza, Roma)

Dott. Mirko Acquati (Oncologia Medica, ASST Monza, Monza)

Prof. Francesco Boccardo (Clinica Oncologia Medica, IST Istituto nazionale per la ricerca sul cancro, Genova)

Prof. Giorgio Vittorio Scagliotti (S.S.D. Oncologia Polmonare, A.O.U. San Luigi Gonzaga, Orbassano)

Dott. Manlio Mencoboni (U.O.S. Oncologia, A.O. Villa Scassi, Genova)

Dott. Ugo De Giorgi (Dipartimento di Oncologia, IRST di Meldola, Meldola)

Dott. Gennaro Micheletti (Urologia, Ospedale San G. Moscati, Avellino)

Dott. Gaetano Lanzetta (Oncologia, Casa di Cura INI, Grottaferrata)

Dott.ssa Donata Sartori (UOC Oncologia ed Ematologia oncologica, Ospedale di Mirano, Mirano)

Dott. Paolo Carlini (Oncologia Medica 1, I.F.O. Regina Elena, Roma)

Prof. Hector Josè Soto Parra (U.O.C. Oncologia, A.O.U. Policlinico-Vittorio Emanuele PO Rodolico, Catania)

Dott. Michele Battaglia (Urologia I univ, A.O.U. Policlinico Consorziale, Bari)

Dott. Francesco Uricchio (Urologia, A.O.R.N. Monaldi, Napoli)

Dott. Antonio Bernardo (USD Oncologia Medica, Fondazione Maugeri, Pavia)

Prof. Antonello De Lisa (Urologia, Ospedale SS Trinità, Cagliari)

Prof. Giuseppe Carrieri (U.O. Urologia, A.O.U. Riuniti Foggia, Foggia)

Dott. Antonio Ardizzoia (Oncologia Medica, ASST Lecco, Lecco)

Dott. Michele Aieta (Oncologia Medica, CROB Ospedale Oncologico Regionale, Rionero in Vulture)

Dott. Salvatore Pisconti (Oncologia Medica, Ospedale San G. Moscati, Taranto)

Prof. Paolo Marchetti (U.O.C. Oncologia Medica, A.O.U. Sant’Andrea, Roma)

Prof.ssa Fabiola Paiar (Radioterapia univ., A.O.U. Pisana, Pisa)

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R.L., Torre L.A., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller K.D., Nogueira L., Mariotto A.B., et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(5):363–385. doi: 10.3322/caac.21565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nuhn P., De Bono J.S., Fizazi K., et al. Update on systemic prostate cancer therapies: management of metastatic castration-resistant prostate Ccncer in the era of precision oncology. Eur Urol. 2019;75(1):88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ritch C.R., Cookson M.S. Advances in the management of castration resistant prostate cancer. BMJ. 2016;355:i4405. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karantanos T., Evans C.P., Tombal B., Thompson T.C., Montironi R., Isaacs W.B. Understanding the mechanisms of androgen deprivation resistance in prostate cancer at the molecular level. Eur Urol. 2015;67(3):470–479. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sartor O., de Bono J.S. Metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(7):645–657. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1701695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potter G.A., Barrie S.E., Jarman M., Rowlands M.G. Novel steroidal inhibitors of human cytochrome P45017 alpha (17 alpha-hydroxylase-C17,20-lyase): potential agents for the treatment of prostatic cancer. J Med Chem. 1995;38(13):2463–2471. doi: 10.1021/jm00013a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Bono J.S., Logothetis C.J., Molina A., et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(21):1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fizazi K., Scher H.I., Molina A., et al. Abiraterone acetate for treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: final overall survival analysis of the COU-AA-301 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(10):983–992. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70379-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryan C.J., Smith M.R., de Bono J.S., et al. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):138–148. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rathkopf D.E., Smith M.R., de Bono J.S., et al. Updated interim efficacy analysis and long-term safety of abiraterone acetate in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients without prior chemotherapy (COU-AA-302) Eur Urol. 2014;66(5):815–825. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan C.J., Smith M.R., Fizazi K., et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus placebo plus prednisone in chemotherapy-naive men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (COU-AA-302): final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(2):152–160. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basch E., Autio K., Ryan C.J., et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus prednisone alone in chemotherapy-naive men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: patient-reported outcome results of a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(12):1193–1199. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70424-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchioni M., Sountoulides P., Bada M., et al. Abiraterone in chemotherapy-naive patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a systematic review of ‘real-life’ studies. Ther Adv Urol. 2018;10(10):305–315. doi: 10.1177/1756287218786160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chowdhury S., Bjartell A., Lumen N., et al. Real-world outcomes in first-line treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: the Prostate Cancer Registry. Target Oncol. 2020;15(3):301–315. doi: 10.1007/s11523-020-00720-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Procopio G., Chiuri V.E., Giordano M., et al. Effectiveness of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in chemotherapy-naive patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in a large prospective real-world cohort: the ABItude study. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2020;12 doi: 10.1177/1758835920968725. 1758835920968725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cleeland C.S., Ryan K.M. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singap. 1994;23(2):129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esper P., Mo F., Chodak G., Sinner M., Cella D., Pienta K.J. Measuring quality of life in men with prostate cancer using the functional assessment of cancer therapy-prostate instrument. Urology. 1997;50(6):920–928. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00459-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.EuroQol Group EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scalone L., Cortesi P.A., Ciampichini R., et al. Italian population-based values of EQ-5D health states. Value Health. 2013;16(5):814–822. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morisky D.E., Ang A., Krousel-Wood M., Ward H.J. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10(5):348–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 22.Berlowitz D.R., Foy C.G., Kazis L.E., et al. Effect of intensive blood-pressure treatment on patient-reported outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(8):733–744. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morisky D.E., DiMatteo M.R. Improving the measurement of self-reported medication nonadherence: response to authors. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(3):255–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.002. ; discussion 8-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fabbrini G., Abbruzzese G., Barone P., et al. Adherence to anti-Parkinson drug therapy in the “REASON” sample of Italian patients with Parkinson’s disease: the linguistic validation of the Italian version of the “Morisky Medical Adherence Scale-8 items”. Neurol Sci. 2013;34(11):2015–2022. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1438-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573–577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan J., Yap S.Y., Fong Y.C., et al. Real-world outcome with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in Asian men with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer: the Singapore experience. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2020;16(1):75–79. doi: 10.1111/ajco.13241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koninckx M., Marco J.L., Perez I., Faus M.T., Alcolea V., Gomez F. Effectiveness, safety and cost of abiraterone acetate in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a real-world data analysis. Clin Transl Oncol. 2019;21(3):314–323. doi: 10.1007/s12094-018-1921-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cavo A., Rubagotti A., Zanardi E., et al. Abiraterone acetate and prednisone in the pre- and post-docetaxel setting for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a mono-institutional experience focused on cardiovascular events and their impact on clinical outcomes. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10 doi: 10.1177/1758834017745819. 1758834017745819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cindolo L., Natoli C., De Nunzio C., et al. Safety and efficacy of abiraterone acetate in chemotherapy-naive patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: an Italian multicenter “real life” study. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):753. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3755-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyake H., Hara T., Terakawa T., Ozono S., Fujisawa M. Comparative assessment of clinical outcomes between abiraterone acetate and enzalutamide in patients with docetaxel-naive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: experience in real-world clinical practice in Japan. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15(2):313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halabi S., Vogelzang N.J., Kornblith A.B., et al. Pain predicts overall survival in men with metastatic castration-refractory prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15):2544–2549. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scher H.I., Morris M.J., Stadler W.M., et al. Trial design and objectives for castration-resistant prostate cancer: updated recommendations from the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group 3. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(12):1402–1418. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harland S., Staffurth J., Molina A., et al. Effect of abiraterone acetate treatment on the quality of life of patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer after failure of docetaxel chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(17):3648–3657. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.07.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gotto G., Drachenberg D.E., Chin J., et al. Real-world evidence in patient-reported outcomes (PROs) of metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) patients treated with abiraterone acetate + prednisone (AA+P) across Canada: final results of COSMiC. Can Urol Assoc J. 2020;14(12):E616–E620. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.6388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kretschmer A., Ploussard G., Heidegger I., et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with advanced prostate cancer: a systematic review. Eur Urol Focus. 2021;7:742–751. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2020.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thiery-Vuillemin A., Hvid Poulsen M., Lagneau E., et al. Impact of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone or enzalutamide on patient-reported outcomes in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: final 12-mo analysis from the observational AQUARiUS study. Eur Urol. 2020;77(3):380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khalaf D.J., Sunderland K., Eigl B.J., et al. Health-related quality of life for abiraterone plus prednisone versus enzalutamide in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: results from a phase II randomized trial. Eur Urol. 2019;75(6):940–947. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salem S., Komisarenko M., Timilshina N., et al. Impact of abiraterone acetate and enzalutamide on symptom burden of patients with chemotherapy-naive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2017;29(9):601–608. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lafeuille M.H., Grittner A.M., Lefebvre P., et al. Adherence patterns for abiraterone acetate and concomitant prednisone use in patients with prostate cancer. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20(5):477–484. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.5.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Behl A.S., Ellis L.A., Pilon D., Xiao Y., Lefebvre P. Medication adherence, treatment patterns, and dose reduction in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer receiving abiraterone acetate or enzalutamide. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2017;10(6):296–303. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fallara G., Lissbrant I.F., Styrke J., Montorsi F., Garmo H., Stattin P. Observational study on time on treatment with abiraterone and enzalutamide. PLoS One. 2020;15(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grundmark B., Garmo H., Zethelius B., Stattin P., Lambe M., Holmberg L. Anti-androgen prescribing patterns, patient treatment adherence and influencing factors; results from the nationwide PCBaSe Sweden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68(12):1619–1630. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1290-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu J., Liao R., Su C., et al. Toxicity profile characteristics of novel androgen-deprivation therapy agents in patients with prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18(2):193–198. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2018.1419871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prati V., Ruatta F., Aversa C., et al. Cardiovascular safety of abiraterone acetate in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients: a prospective evaluation. Future Oncol. 2018;14(5):443–448. doi: 10.2217/fon-2017-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verzoni E., Grassi P., Ratta R., et al. Safety of long-term exposure to abiraterone acetate in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and concomitant cardiovascular risk factors. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2016;8(5):323–330. doi: 10.1177/1758834016656493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Procopio G., Grassi P., Testa I., et al. Safety of abiraterone acetate in castration-resistant prostate cancer patients with concomitant cardiovascular risk factors. Am J Clin Oncol. 2015;38(5):479–482. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3182a790ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sciarra A., Gentile V., Panebianco V. Multidisciplinary management of prostate cancer: how and why. Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2013;1(1):12–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cornford P., Bellmunt J., Bolla M., et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of relapsing, metastatic, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2017;71(4):630–642. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saad F., Aprikian A., Finelli A., et al. 2021 Canadian Urological Association (CUA)-Canadian Uro Oncology Group (CUOG) guideline: management of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) Can Urol Assoc J. 2021;15(2):E81–E90. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.7074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parker C., Castro E., Fizazi K., et al. Prostate cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(9):1119–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Atwell D., Vignarajah D.D., Chan B.A., et al. Referral rates to multidisciplinary team meetings: is there disparity between tumour streams? J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2019;63(3):378–382. doi: 10.1111/1754-9485.12851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Magnani T., Valdagni R., Salvioni R., et al. The 6-year attendance of a multidisciplinary prostate cancer clinic in Italy: incidence of management changes. BJU Int. 2012;110(7):998–1003. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.10970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fizazi K., Tran N., Fein L., et al. Abiraterone plus prednisone in metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(4):352–360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.James N.D., de Bono J.S., Spears M.R., et al. Abiraterone for prostate cancer not previously treated with hormone therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(4):338–351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.