Abstract

Background

COVID-19 survivors face the risk of long-term sequelae including fatigue, breathlessness, and functional limitations. Pulmonary rehabilitation has been recommended, although formal studies quantifying the effect of rehabilitation in COVID-19 patients are lacking.

Methods

We conducted a prospective observational cohort study including consecutive patients admitted to an outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation center due to persistent symptoms after COVID-19. The primary endpoint was change in 6-min walk distance (6MWD) after undergoing a 6-week interdisciplinary individualized pulmonary rehabilitation program. Secondary endpoints included change in the post-COVID-19 functional status (PCFS) scale, Borg dyspnea scale, Fatigue Assessment Scale, and quality of life. Further, changes in pulmonary function tests were explored.

Results

Of 64 patients undergoing rehabilitation, 58 patients (mean age 47 years, 43% women, 38% severe/critical COVID-19) were included in the per-protocol-analysis. At baseline (i.e., in mean 4.4 months after infection onset), mean 6MWD was 584.1 m (±95.0), and functional impairment was graded in median at 2 (IQR, 2–3) on the PCFS. On average, patients improved their 6MWD by 62.9 m (±48.2, p < 0.001) and reported an improvement of 1 grade on the PCFS scale. Accordingly, we observed significant improvements across secondary endpoints including presence of dyspnea (p < 0.001), fatigue (p < 0.001), and quality of life (p < 0.001). Also, pulmonary function parameters (forced expiratory volume in 1 s, lung diffusion capacity, inspiratory muscle pressure) significantly increased during rehabilitation.

Conclusion

In patients with long COVID, exercise capacity, functional status, dyspnea, fatigue, and quality of life improved after 6 weeks of personalized interdisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation. Future studies are needed to establish the optimal protocol, duration, and long-term benefits as well as cost-effectiveness of rehabilitation.

Keywords: Coronavirus disease 2019, Dyspnea, Exercise training, Long coronavirus disease, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Sequelae, Outpatient, Pulmonary rehabilitation, Quality of life

Introduction

Over 100 million people have been infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and a significant proportion of patients experience severe symptoms leading to hospitalization due to COVID-19, of which some develop acute respiratory disease syndrome (ARDS) and many venous and arterial thromboembolic complications [1, 2]. The majority of patients survive but COVID-19 is not a time-limited disease, as COVID-19 survivors face the risk of long-term sequelae including respiratory, neuropsychiatric, cardiovascular, hematologic, gastrointestinal, renal, and endocrine manifestations, also referred to as “long COVID” [3, 4, 5]. The pathological mechanisms underlying the disease and its differences in clinical symptoms still remain largely unknown. Persistent inflammation, however, is considered a key mediator in the multifactorial genesis of the long-term sequelae [5, 6].

Consensus to define long COVID or post-acute COVID-19 syndrome has not been reached yet [5, 7]. Fatigue, breathlessness, muscle weakness, and psychological distress rank among the most frequent symptoms reported by hospitalized COVID-19 patients after discharge [3, 8, 9]. Notably, also a considerable proportion of low-risk individuals with mild COVID-19 experience prolonged symptoms affecting work, social, and home life [3, 10, 11, 12]. In light of a fast-increasing disease burden of long COVID, strategies to improve long-term outcomes of patients are urgently needed. Currently, guidance statements and position papers propose acute and long-term rehabilitation [13, 14, 15, 16]. However, these recommendations are based on expert consensus only without evidence from dedicated studies evaluating the beneficial effects of inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation in patients suffering from long-term health impairments after COVID-19. To address this lack of evidence, we conducted a prospective study with the aim to characterize the effectiveness and safety of outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with persistent or progressive respiratory and/or functional limitations after COVID-19.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

We included all consecutive adult patients admitted between May 2020 and April 2021 to an outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation center (Vienna, Austria) due to persistent or progressive symptoms after laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 in a single-center prospective study. All patients included in the analysis provided written informed consent for study participation. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (Nr. 1539/2020) and conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Procedures

Data on patient demographics (i.e., age, sex, body mass index, education level, cigarette smoking), comorbidities, medications, and COVID-related information (date of positive PCR test, severity, clinical course and complications, signs and symptoms of long COVID) were collected in a face-to-face interview by the treating physician. Clinical data on the acute phase of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 were retrieved from electronic medical records. The severity of COVID-19 was categorized into 3 categories: mild to moderate (outpatients with flu-like illness or suspected pneumonia), severe (hospitalized patients treated in a general ward), and critical (hospitalized patients treated in an intensive care unit) [17].

At baseline, patients underwent a detailed and structured initial functional capacity, respiratory function, dyspnea, and quality of life assessment. Thereafter, patients underwent a multi-professional and individualized rehabilitation according to the Austrian guidelines for outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation [18]. In brief, participants completed individualized endurance, strength, and inspiratory muscle training over a 6 weeks period, 3 times per week for 3–4 h each, under the supervision of physicians, physiotherapists, and sports scientists. A fundamental aspect of the program consisted of individualized patient education, psychosocial counseling by a psychologist, nutritional education by a dietologist, and smoking cessation sessions (online suppl. File and Table S1; see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000522118 for all online suppl. material).

Measurements and Outcomes

The primary study endpoint was the change in 6-min walk distance (6MWD) after 6 weeks of rehabilitation. The 6-min walk test, a well-established tool to evaluate functional capacity, was performed according to the European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines. Based on the European Respiratory Society guidelines and a systematic review of patients with cardiopulmonary diseases, we predefined that an improvement of 30.5 m would be the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) [19].

Secondary outcomes comprise change in the post-COVID-19 functional status (PCFS) scale (which ranges from 0 to 4, with 0 representing no functional limitation and 4 severe functional limitations; a separate category of 5 is usually added for patients who expire) [20], the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale at rest (which ranges from 0 to 4, with 0 representing no dyspnea and 4 maximal dyspnea), Borg dyspnea scale assessed at maximal exertion on cycle ergometer (which ranges from 0 to 10, with 0 representing no dyspnea and 10 maximal dyspnea), 1-min sit to stand test (1-MSTST) and maximal workload in watt measured on a cycle ergometer.

Over the course of the study, due to the concurrently increasing knowledge about long-term consequences of COVID-19, two additional questionnaires were amended to the study protocol to assess changes in fatigue, as assessed by the Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS, which ranges from 10 to 50, with >21 indicating substantial fatigue, MCID was defined as a change of ≥4) [21], and quality of life measured by the EuroQol Group 5-dimension 5-level (EQ-5D-5L) questionnaire. Results on quality of life are presented as EQ-index scores (in which scores range from −0.6 to 1.0, with higher scores indicating a better quality of life) and visual analog scale (VAS, which range from 0 to 100%). Further, changes in pulmonary function tests between pre- and post-rehabilitation assessments were explored including forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), maximal inspiratory muscle strength, and lung diffusion capacity (DLCO).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are presented as frequencies (percentage) and continuous data as mean (±standard deviation) or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. Missing values were not imputed and presented accordingly in the results.

To detect a mean difference from baseline (i.e., admission to rehabilitation center) of 30.5 m in the 6MWD, at a power of 80%, we calculated that a sample size of 55 patients was required when using a paired sample t test with a 5% two-sided significance level and assuming a 5% dropout rate. The primary efficacy analysis was performed with data from the per-protocol population, which was defined as patients who completed at least 70% of the rehabilitation sessions. An intention-to-treat analysis was not possible due to the lack of outcome data in patients who did not complete rehabilitation. The secondary efficacy endpoints were analyzed similarly when the mean change from baseline was normally distributed. In the case of semicontinuous scales (e.g., Borg dyspnea scale) or skewed distributions, Wilcoxon matched-pairs sign rank test was used alternatively.

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and an alpha value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Due to the explorative nature of the study, we did not adjust for multiple testing. Statistical analysis was conducted using R (Version 3.6.2; R Core Team, 2019).

Results

Study Population

In total, 64 consecutive patients were admitted to the outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation center due to persistent or progressive respiratory symptoms or functional limitations after confirmed COVID-19. Of those, 6 patients discontinued rehabilitation prematurely, all of whom completed less than 28% of rehabilitation sessions. Reason for termination included positive retesting for SARS-CoV-2, fear of infection at the rehabilitation center, injury at home, fever with suspected pneumonia but negative SARS-CoV-2 test, death of a close family member, and one participant mentioned personal issues.

Thus, the per-protocol study population consisted of 58 patients (43% female). Patients were 46.8 (±12.6) years old and had a body mass index of 26.2 (±5.3) kg/m2. Twenty-two patients (38%) had been hospitalized due to COVID-19, while 36 (62%) patients were quarantined at home with mild to moderate symptoms of which 5 (14%) had clinically defined pneumonia. In Table 1, additional patient demographics, comorbidities, and specific information on COVID-19 and long-term symptoms are presented. In brief, preexisting conditions included arterial hypertension (22%), asthma (19%), diabetes mellitus type II (10%), and coronary artery disease (5%). Patients started rehabilitation 4.4 (±2.0, range 1.9–11.1) months after testing positive for SARS-CoV-2. Mean baseline 6MWD was 584.1 (±95.0) m (87.7% of predicted). The median PCFS scale was 2 (IQR, 1–3). All patients reported signs and symptoms of long COVID such as functional limitations (94%), exertional dyspnea (71%), and substantial fatigue (64%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Total (N = 58) | Home care (N = 36) | Hospitalized COVID-19 patients (N = 22) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years | 46.8 (±12.6) | 43.2 (±12.7) | 52.7 (±11.4) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 25 (43.1) | 22 (61.1) | 3 (13.6) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.2 (±5.3) | 25.3 (±5.3) | 27.6 (±4.8) |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| Lower secondary | 19 (32.3) | 8 (22.3) | 11 (50.0) |

| Upper secondary | 10 (17.2) | 7 (19.4) | 3 (13.6) |

| Higher | 29 (50.0) | 21 (58.3) | 8 (36.4) |

| Smoking, n (%) | |||

| Current | 2 (3.4) | 2 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Former | 20 (34.5) | 10 (27.8) | 10 (45.5) |

| Never | 36 (62.1) | 24 (66.7) | 12 (54.5) |

| COVID-19-specific characteristics | |||

| Severity, n (%) | |||

| Mild/moderate | 36 (62.1) | 36 (100.0) | − |

| Severe | 11 (19.0) | − | 11 (50.0) |

| Critical | 11 (19.0) | − | 11 (50.0)* |

| Length of hospitalization, days | − | − | 19.6 (±10.1) |

| Time to rehabilitation after confirmed COVID-19, | 4.4 (±2.0) | 4.4 (±2.1) | 4.3 (±1.8) |

| months | |||

| PCFS scale (5) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (2–3) |

| Signs and symptoms of long COVID, n (%) | |||

| Dyspnea | 41 (70.7) | 25 (69.4) | 16 (72.7) |

| Fatigue | 37 (63.8) | 23 (63.9) | 14 (63.7) |

| Neurocognitive sequelae | 22 (37.9) | 13 (36.1) | 9 (40.9) |

| Lung residues | 10 (17.2) | 3 (8.3) | 7 (31.8) |

| Cardiac sequelae | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.5) |

| Gastrointestinal sequelae | 5 (8.6) | 3 (8.3) | 2 (9.1) |

| Hematologic sequelae | 6 (10.3) | 4 (11.1) | 2 (9.1) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Emphysema | 2 (3.4) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (4.5) |

| Asthma | 11 (19.0) | 9 (25.0) | 2 (9.1) |

| Coronary artery disease | 3 (5.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (13.6) |

| Arterial hypertension | 13 (22.4) | 5 (13.9) | 8 (36.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus II | 6 (10.3) | 1 (2.8) | 5 (22.7) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.5) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 18 (31.0) | 4 (11.1) | 14 (63.6) |

| Hyperuricemia | 5 (8.6) | 1 (2.8) | 4 (18.2) |

| Thyroid disease | 5 (8.6) | 3 (8.3) | 2 (9.1) |

| Renal disease | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Liver disease (steatosis hepatis) | 3 (5.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (13.6) |

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| Corticosteroids (oral or inhaled)# | 17 (29.3)# | 12 (33.3)# | 5 (22.7) |

| Long acting β-agonists | 14 (24.1) | 10 (27.8) | 4 (18.2) |

| Psychoactive agents | 10 (17.2) | 7 (19.4) | 3 (13.6) |

| Antihypertensive drugs | 13 (22.4) | 6 (16.7) | 7 (31.8) |

| Statins | 7 (12.1) | 1 (2.8) | 6 (27.3) |

| Oral antidiabetics | 5 (8.6) | 0 (0) | 5 (22.7) |

| Antithrombotic agents | 4 (6.9) | 0 (0) | 4 (18.2) |

| Thyroxine | 3 (5.2) | 2 (5.6) | 1 (4.5) |

| Antihistamines | 4 (6.9) | 2 (5.6) | 2 (9.1) |

| Supplements (vitamin D, calcium, etc.) | 8 (13.8) | 6 (16.7) | 2 (9.1) |

Number in brackets indicate missing values

Of those, 7 patients were mechanically ventilated.

One patient was on oral corticosteroids.

Primary Endpoint

The primary endpoint 6MWD had increased from baseline to end of rehabilitation by 62.9 (±48.2) meters, which is twice the MCID (Table 2); overall, 36 (70.6%) patients increased their 6MWD with more than 30.5 m, 11 (21.6%) patients improved but below the MCID, and 4 (7.8%) patients did not improve their 6MWD during rehabilitation (Fig. 1). The number needed to treat (NNT) to improve the 6MWD by the MCID was 1.42.

Table 2.

Change from baseline to end of 6-week-rehabilitation in primary and secondary end points and in pulmonary function testing

| Patients, n | Baseline | Discharge | Change | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint | |||||

| 6MWD, m | 51 | 584.1 (±95.0) | 647.0 (±99.5) | 62.9 (±48.2) | <0.001 |

| Secondary endpoints | |||||

| PCFS scale | 53 | 2 (2–3) | 1 (0–2) | − | <0.001 |

| Borg dyspnea score at max exertion | 49 | 7 (6–8) | 7 (4–7) | − | <0.001 |

| mMRC scale | 56 | 1 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | − | <0.001 |

| 1-MSTST, count | 48 | 33.3 (±10.4) | 42.5 (±13.7) | 9.2 (±7.7) | <0.001 |

| Maximal workload, watt | 57 | 156.4 (±80.4) | 178.3 (±61.0) | 21.8 (±74.0) | 0.030 |

| EQ-5D index score | 34 | 0.89 (0.81–0.91) | 0.91 (0.84–1.00) | - | 0.075 |

| EQ-5D VAS | 35 | 63.7 (±17.9) | 78.6 (±13.9) | 14.9 (±13.2) | <0.001 |

| Fatigue assessment scale | 39 | 26 (20–32) | 20 (16–25) | − | <0.001 |

| Exploratory endpoints − pulmonary function tests | |||||

| FEV1, % predicted | 58 | 82.6 (±18.4) | 89.5 (±16.2) | 6.9 (±20.0) | 0.011 |

| FEV1/FVC, % predicted | 58 | 77.7 (±10.1) | 78.6 (±9.5) | 0.9 (±10.0) | 0.502 |

| DLCO, % predicted | 42 | 83.9 (±19.9) | 88.0 (±16.9) | 4.1 (±11.3) | 0.037 |

| Maximal inspiratory pressure, mbar | 54 | 90.2 (±30.1) | 115.6 (±30.0) | 25.4 (±18.1) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as mean (± standard deviation) or median (interquartile range). For semicontinuous scales, Wilcoxon matched-pairs sign rank test was used: PCFS scale (which ranges from 0 to 4, with 0 representing no functional limitation and 4 severe functional limitations), Borg dyspnea scale (which ranges from 0 to 10, with 0 representing no dyspnea and 10 maximal dyspnea), mMRC scale (which ranges from 0 to 4, with 0 representing no dyspnea and 4 maximal dyspnea), EQ-5D index score (in which scores range from −0.6 to 1.0, with higher scores indicating a better quality of life), FAS (which ranges from 10 to 50, with >21 indicating substantial fatigue, MCID was defined as a change of ≥4).

Fig. 1.

Change in 6MWD between baseline and end of rehabilitation. The number needed to treat (NNT) to improve the 6MWD by the minimal clinical important difference of 30.5 m was 1.42.

Secondary Endpoints

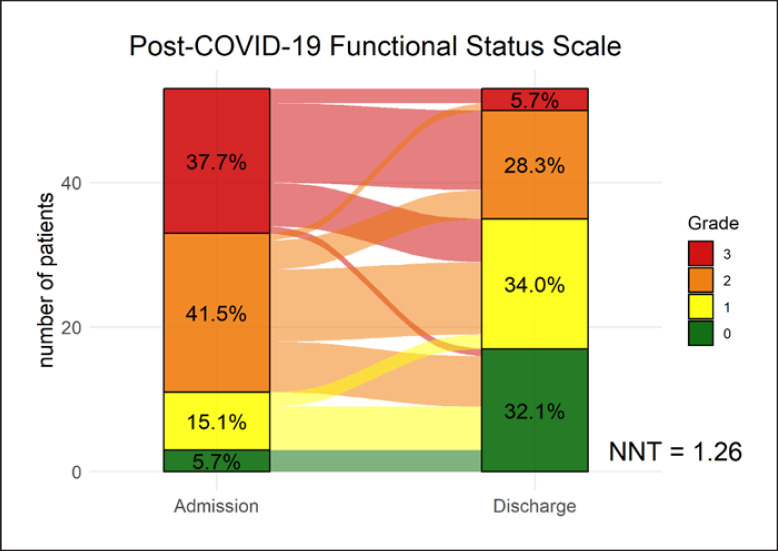

After 6 weeks of pulmonary rehabilitation, the PCFS scale decreased from a median of 2 (IQR, 2–3) to 1 (IQR, 0–2; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). NNT to improve 1 PCFS scale grade was 1.26. The Borg dyspnea score, measured at maximal exertion during cycle ergometer, decreased to 7 (IQR, 4–7; p < 0.001). Similarly, dyspnea measured with the mMRC scale decreased to 1 (IQR, 0–1; p < 0.001). Further, patients improved in maximal workload and endurance capacity represented by an increase of 21.8 W (±74.0; p = 0.03) on the cycle ergometer and 9.2 more repetitions at the 1-MSTST (±7.7; p < 0.001). As the FAS and EQ-5D-5L, questionnaires were amended during the study, fewer patients completed the 2 questionnaires (N = 39 and N = 35). At discharge, patients reported a median decrease of 6.0 points on the FAS (p < 0.001) indicating a clinically significant improvement. Quality of life increased when assessed with the EuroQol Group 5-dimension visual analog scale by 14.9 percent points (±13.2; p < 0.001). The EQ-5D index score increased with 0.04 points (±0.14; p = 0.075).

Fig. 2.

Change in PCFS scale from baseline to end of rehabilitation. The number needed to treat (NNT) to reduce functional limitations by 1 grade was 1.26.

Exploratory Endpoints and Safety

Changes in pulmonary function and respiratory muscle strength were explored after initial data analysis. At baseline, patients presented with a decreased FEV1 (82.6% ± 18.4) and DLCO (84.6% ± 18.5) from their age, sex, and height-specific expected value. Both parameters improved by 6.9 (±20.0; p = 0.011) and 4.1 (±11.3; p = 0.037) percent points, while the FEV1/FVC ratio remained constant (mean change of 0.9 ± 10.0 percent points; p = 0.50). Further, maximal inspiratory mouth pressure increased by 28% (25.4 ± 18.1 mbar; p < 0.001) from 90.2 (±30.1) to 115.6 (±30.0) mbar.

No adverse events were recorded during rehabilitation. In particular, no patients had a blood oxygenation level below 90% (at rest and maximal exertion) and no usage of oxygen therapy was required during rehabilitation.

Discussion

In this study, a 6-week outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation significantly improved exercise capacity of patients with long COVID. On average, we observed a lowering of one grade on the PCFS scale. Notably, we saw an increase in pulmonary function (i.e., FEV1 and DLCO) and inspiratory muscle strength. Furthermore, significant improvements were also observed in secondary endpoints, including dyspnea, fatigue, and quality of life.

In this cohort, most patients suffered from mild to moderate COVID-19 but had substantial limitations in form of persistent symptoms including reduced exercise capacity, dyspnea, fatigue, and functional impairment. In the baseline evaluation, these complaints were substantiated, with patients on average reaching only 88% of their predicted 6MWD and a median impairment grade of 2 on the PCFS scale. Such findings are well-known in survivors of critical illness, who face the risk of substantial impairment due to the post-intensive care syndrome [22]. This condition includes ICU-acquired weakness, critical illness polyneuropathy, and myopathy [23]. Often, recovery is slow and incomplete. In a 5-year follow-up study on 109 ARDS survivors, the 6MWD was at 76% of the predicted capacity with patients reporting physical and psychological sequelae [24]. Predominantly, restrictive pulmonary alterations and decreased diffusion capacity after acute lung injury contribute to long-term functional limitations and lead to a decreased health-related quality of life [25]. Taken together, these aspects might explain the long-term sequelae of COVID-19 associated ARDS patients and provide reasonable evidence to support rehabilitation for this patient group [26]. However, there is also extensive data on the dismal long-term health impact on patients with COVID-19 with only mild to moderate disease and without COVID-19-related hospitalization [8, 27, 28]. Similarities to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS) epidemic of 2003 and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus outbreak of 2012 could be recognized [29, 30, 31]. In a study on 97 SARS survivors at 1-year, 6MWD and DLCO were lowered compared to normal healthy subjects [32]. The complexity and severity of the sequelae led to the definition of the post-SARS syndrome, to which the long COVID/post-acute COVID-19 syndrome shows similarities [33]. Lessons learned from those 2 outbreaks may now guide health care strategies including exercise training and rehabilitation programs in patients at risk for long-term sequelae [34, 35, 36].

Despite their young age and rather high baseline 6MWD, participants improved their 6MWD by twice the MCID, which is substantially higher compared to rehabilitation data in other respiratory diseases [37, 38]. Similar improvements in exercise capacity were observed in maximal workload and the 1-MSTST. Functional status improved as indicated by an NNT of 1.26 to lower the PCFS by 1 grade. Further, patients improved their level of dyspnea during daily activities (mMRC scale) and at maximal exertion (Borg scale). We observed a 14.9 percent point increase in quality of life on the EuroQol Group 5-dimension visual analog scale. The impact on quality of life was not statistically significant when measured with the EQ-5D index score, which is likely due to the lower number of patients completing this questionnaire. Furthermore, we noted a clinically significant reduction in fatigue (i.e., change in FAS) between baseline and end of rehabilitation. In line with previous data on post-COVID-19, patients showed a reduced FEV1 and DLCO of 82.6% and 84.6% at baseline [39, 40, 41]. Of note, both parameters (i.e., DLCO and FEV1) significantly improved over the 6-week-rehabilitation period, which is reassuring as impaired diffusion capacity was the most common anomaly reported at discharge in a study on noncritical COVID-19 cases [41].

Beneficial effects of rehabilitation have been clearly demonstrated in a broad range of health conditions. In patients with pulmonary diseases (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension), rehabilitation reduces dyspnea, increases exercise, and improves health-related quality of life [42]. Thus and based on our and previous findings, rehabilitation might be a valuable treatment option in patients with persistent symptoms after COVID-19 [13, 14, 15, 43]. Two previous studies investigated acute or post-acute inpatient rehabilitation in patients with COVID-19. The first study retrospectively analyzed rehabilitation after acute care and provided feasibility data on 28 COVID-19 survivors [39]. The second study prospectively followed up 24 mild to moderate and 26 severe to critical cases [40]. To the best of our knowledge, our study provides the first results on outpatient rehabilitation on patients with long COVID. The patients in our study were substantially younger compared to the inpatient rehabilitation population described in the previous study but had a fairly similar age distribution when compared to a prior study of our outpatient rehabilitation center [38]. A possible explanation here is that older patients are more likely to choose inpatient rehabilitation, while younger patients attend outpatient rehabilitation likely due to better compatibility of outpatient rehabilitation with duties at home or work. Taken together, pulmonary rehabilitation was found to have short-term benefits in exercise capacity and patient-reported outcomes and no adverse events in all 3 studies. To ensure long-term effects, maintenance of physical activity and healthy lifestyles should be enforced by generating personalized home-based rehabilitation plans or transition patients into phases of long-term rehabilitation at an outpatient center.

Several limiting aspects need to be considered when interpreting our study findings. First, no causal role of rehabilitation can be assumed with certainty due to our observational study design. However, the conduct of a randomized controlled study on the effect of rehabilitation was considered unethical due to the lack of clinical equipoise as highlighted in the corresponding guidance statements [13, 14, 15]. Therefore, the observed improvement in the primary and secondary endpoints might also be due to the normal recovery process or regression to the mean. However, given that patients went through outpatient rehabilitation in mean 4.4 months after the infection, causal beneficial effects of this 6-weeks individualized rehabilitation program seem to be a reasonable assumption. Second, our study is limited by missing values for some of the secondary outcomes. Third, our results cannot be generalized to the total population of COVID-19 survivors, as the study population was relatively young and had a high proportion of highly educated people who likely had a good health care provider network that referred them to outpatient rehabilitation without clear guidelines at that time. Fourth, the limited number of patients hindered subgroup analysis to examine differences in outcome and course of the disease stratified by patient characteristics (e.g., severity of COVID-19 or primary symptom of long COVID). However, in conjunction with prior reports on acute and post-acute inpatient rehabilitation [39, 40, 43], multi-professional individualized pulmonary rehabilitation appears to be an important treatment strategy for COVID-19 survivors with persistent or progressive symptoms.

The cause of long-term sequelae in COVID-19 is currently unknown. However, it is evident now that not only the majority of COVID-19 survivors discharged from hospital but also patients with home treatment need an integrated model of care to recognize and treat long-term consequences of this multi-organ disease. Therefore, clinicians should monitor COVID-19 patients and evaluate a potential need for rehabilitation. Rehabilitation service providers should be aware of deconditioning as seen in chronic fatigue syndrome and should focus on individualized rehabilitation plans in contrast to a one-model-fits-all approach. As more patients accrue, identification of specific subgroups would be of high relevance to tailor specific therapies to each subgroup. Future rehabilitation studies may shed more light on the optimal treatment of patients with long COVID and evaluate cost-effectiveness (NCT04649918, NCT04365738, NCT04406532, NCT04642040).

Conclusion

In summary, our findings support personalized rehabilitation as an integrated model of care for patients with long COVID. In our study, functional limitations and fatigue, the 2 most commonly reported long-term sequelae in patients with COVID-19, improved after the 6-week period of outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation. Long-term effects of rehabilitation and the observed improvement of pulmonary function need to be addressed in future trials.

Statement of Ethics

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna, approval number 1539/2020. All patients included in the analysis provided written informed consent for study participation.

Conflict of Interest Statement

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources

The authors have no funding to report.

Author Contributions

S.N. and R.H.Z. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, including and especially any adverse effects. S.N., F.M., F.A.K., D.G., M.P., K.V., A.R.K., and R.H.Z. contributed substantially to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and the writing of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, S.N.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers DAMPJ, Kant KM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–7. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nopp S, Moik F, Jilma B, Pabinger I, Ay C. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4((7)):1178–91. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halpin SJ, McIvor C, Whyatt G, Adams A, Harvey O, McLean L, et al. Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID-19 infection: a cross-sectional evaluation. J Med Virol. 2021;93((2)):1013–22. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polastri M, Nava S, Clini E, Vitacca M, Gosselink R. COVID-19 and pulmonary rehabilitation: preparing for phase three. Eur Respir J. 2020;55((6)):2001822. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01822-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27((4)):601–15. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maltezou HC, Pavli A, Tsakris A. Post-COVID syndrome: an insight on its pathogenesis. Vaccines. 2021;9((5)):497. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mandal S, Barnett J, Brill SE, Brown JS, Denneny EK, Hare SS, et al. Long-COVID': a cross-sectional study of persisting symptoms, biomarker and imaging abnormalities following hospitalisation for COVID-19. Thorax. 2021;76((4)):396–8. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michelen M, Manoharan L, Elkheir N, Cheng V, Dagens D, Hastie C, et al. Characterising long-term covid-19: a rapid living systematic review. medRxiv. 2020 Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Gu X, et al. 6-Month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397((10270)):220–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324((6)):603–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnold DT, Hamilton FW, Milne A, Morley AJ, Viner J, Attwood M, et al. Patient outcomes after hospitalisation with COVID-19 and implications for follow-up: results from a prospective UK cohort. Thorax. 2021;76((4)):399–401. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meys R, Delbressine JM, Goërtz YMJ, Vaes AW, Machado FVC, Van Herck M, et al. Generic and respiratory-specific quality of life in non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Clin Med. 2020;9((12)):3993. doi: 10.3390/jcm9123993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spruit MA, Holland AE, Singh SJ, Tonia T, Wilson KC, Troosters T. COVID-19: interim guidance on rehabilitation in the hospital and post-hospital phase from a European Respiratory Society- and American Thoracic Society-coordinated international task force. Eur Respir J. 2020;56((6)):2002197. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02197-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barker-Davies RM, O'Sullivan O, Senaratne KPP, Baker P, Cranley M, Dharm-Datta S, et al. The Stanford Hall consensus statement for post-COVID-19 rehabilitation. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54((16)):949–59. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas P, Baldwin C, Bissett B, Boden I, Gosselink R, Granger CL, et al. Physiotherapy management for COVID-19 in the acute hospital setting: clinical practice recommendations. J Physiother. 2020;66((2)):73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vitacca M, Carone M, Clini EM, Paneroni M, Lazzeri M, Lanza A, et al. Joint statement on the role of respiratory rehabilitation in the COVID-19 crisis: the Italian position paper. Respiration. 2020;99((6)):493–9. doi: 10.1159/000508399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization . COVID-19 clinical management: living guidance, 25 January 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vonbank K, Zwick RH, Strauss M, Lichtenschopf A, Puelacher C, Budnowski A, et al. [Guidelines for outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation in Austria] Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2015;127((13–14)):503–13. doi: 10.1007/s00508-015-0766-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohannon RW, Crouch R. Minimal clinically important difference for change in 6-minute walk test distance of adults with pathology: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23((2)):377–81. doi: 10.1111/jep.12629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klok FA, Boon GJAM, Barco S, Endres M, Geelhoed JJM, Knauss S, et al. The post-COVID-19 functional status (PCFS) scale: a tool to measure functional status over time after COVID-19. Eur Respir J. 2020;56((1)):2001494. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01494-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michielsen HJ, De Vries J, Van Heck GL, Van de Vijver FJR, Sijtsma K. Examination of the dimensionality of fatigue: the construction of the fatigue assessment scale (FAS) Eur J Psychol Assess. 2004;20((1)):39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rawal G, Yadav S, Kumar R. Post-intensive care syndrome: an overview. J Transl Int Med. 2017;5((2)):90–2. doi: 10.1515/jtim-2016-0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kress JP, Hall JB. ICU-acquired weakness and recovery from critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2014;370((17)):1626–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1209390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matté A, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Cooper A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364((14)):1293–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burnham EL, Hyzy RC, Paine R, 3rd, Coley C, 2nd, Kelly AM, Quint LE, et al. Chest CT features are associated with poorer quality of life in acute lung injury survivors. Crit Care Med. 2013;41((2)):445–56. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31826a5062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanekom S, Gosselink R, Dean E, van Aswegen H, Roos R, Ambrosino N, et al. The development of a clinical management algorithm for early physical activity and mobilization of critically ill patients: synthesis of evidence and expert opinion and its translation into practice. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25((9)):771–87. doi: 10.1177/0269215510397677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tenforde MW, Kim SS, Lindsell CJ, Billig Rose E, Shapiro NI, Files DC, et al. Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network: United States, March–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69((30)):993–8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6930e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goërtz YMJ, Van Herck M, Delbressine JM, Vaes AW, Meys R, Machado FVC, et al. Persistent symptoms 3 months after a SARS-CoV-2 infection:the post-COVID-19 syndrome? ERJ Open Res. 2020;6((4)):00542–2020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00542-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lam MH, Wing YK, Yu MW, Leung CM, Ma RC, Kong AP, et al. Mental morbidities and chronic fatigue in severe acute respiratory syndrome survivors: long-term follow-up. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169((22)):2142–7. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SH, Shin HS, Park HY, Kim JL, Lee JJ, Lee H, et al. Depression as a mediator of chronic fatigue and post-traumatic stress symptoms in middle east respiratory syndrome survivors. Psychiatry Investig. 2019;16((1)):59–64. doi: 10.30773/pi.2018.10.22.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ong KC, Ng AW, Lee LS, Kaw G, Kwek SK, Leow MK, et al. Pulmonary function and exercise capacity in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2004;24((3)):436–42. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00007104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hui DS, Wong KT, Ko FW, Tam LS, Chan DP, Woo J, et al. The 1-year impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on pulmonary function, exercise capacity, and quality of life in a cohort of survivors. Chest. 2005;128((4)):2247–61. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moldofsky H, Patcai J. Chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, depression and disordered sleep in chronic post-SARS syndrome; a case-controlled study. BMC Neurol. 2011;11((1)):37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tansey CM, Louie M, Loeb M, Gold WL, Muller MP, de Jager J, et al. One-year outcomes and health care utilization in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167((12)):1312–20. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan KS, Zheng JP, Mok YW, Li YM, Liu YN, Chu CM, et al. SARS: prognosis, outcome and sequelae. Respirology. 2003;8 Suppl((Suppl 1)):S36–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00522.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lau HM, Ng GY, Jones AY, Lee EW, Siu EH, Hui DS. A randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of an exercise training program in patients recovering from severe acute respiratory syndrome. Aust J Physiother. 2005;51((4)):213–9. doi: 10.1016/S0004-9514(05)70002-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lacasse Y, Martin S, Lasserson TJ, Goldstein RS. Meta-analysis of respiratory rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A Cochrane systematic review. Eura Medicophys. 2007;43((4)):475–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nopp S, Klok FA, Moik F, Petrovic M, Derka I, Ay C, et al. Outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with persisting symptoms after pulmonary embolism. J Clin Med. 2020;9((6)):1811. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hermann M, Pekacka-Egli AM, Witassek F, Baumgaertner R, Schoendorf S, Spielmanns M. Feasibility and efficacy of cardiopulmonary rehabilitation after COVID-19. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;99((10)):865–9. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gloeckl R, Leitl D, Jarosch I, Schneeberger T, Nell C, Stenzel N, et al. Benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation in COVID-19: a prospective observational cohort study. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7((2)):00108–2021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00108-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao YM, Shang YM, Song WB, Li QQ, Xie H, Xu QF, et al. Follow-up study of the pulmonary function and related physiological characteristics of COVID-19 survivors three months after recovery. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;25:100463. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, ZuWallack R, Nici L, Rochester C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188((8)):e13–64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1634ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ceravolo MG, Arienti C, de Sire A, Andrenelli E, Negrini F, Lazzarini SG, et al. Rehabilitation and COVID-19: the cochrane rehabilitation 2020 rapid living systematic review. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2020;56((5)):642–51. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, S.N.