Abstract

Antagonism of aminoglycosides by divalent cations is well documented for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and is regarded as one of the problems in aminoglycoside therapy. It is generally considered that divalent cations interfere with uptake of aminoglycosides at both the outer and inner membranes. It has been demonstrated recently that aminoglycosides can be removed from cells of P. aeruginosa by the three-component multidrug resistance efflux pump MexXY-OprM. We sought to investigate the interplay between efflux and uptake in resistance to aminoglycosides in P. aeruginosa. To do so, we studied the effects of the divalent cations Mg2+ and Ca2+ on susceptibility to aminoglycosides in a wild-type strain of P. aeruginosa and in mutants either overexpressing or lacking the MexXY-OprM efflux pump. MICs of gentamicin, streptomycin, amikacin, apramycin, netilmicin, and arbekacin were determined in Mueller-Hinton broth in the presence of cations added at concentrations that varied from 0.125 to 8 mM. We found, unexpectedly, that while both Mg2+ and Ca2+ antagonized aminoglycosides (up to a 64-fold decrease in susceptibility at 8 mM), antagonism was seen only in the strains of P. aeruginosa that contained the functional MexXY-OprM efflux pump. Our results indicate that inhibition of the MexXY-OprM efflux pump should abolish the antagonism of aminoglycosides by divalent cations, regardless of its precise mechanism. This may significantly increase the therapeutic index of aminoglycosides and improve the clinical utility of this important class of antibiotics.

Aminoglycosides are among the few classes of antibiotics that are useful in the treatment of infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antagonism of aminoglycosides by divalent cations is well documented for this organism (6, 21, 41) and is regarded as one of the problems in aminoglycoside therapy. It is a general understanding that (i) divalent cations interfere with uptake of aminoglycosides, and (ii) this interference occurs at both outer and inner membranes (3, 5, 41). It was demonstrated that polycationic aminoglycosides interact with divalent cation binding sites positioned on cell surface lipopolysaccharides (1, 7). Since aminoglycosides are much larger than the native divalent cations that normally stabilize the outer membrane, their binding causes a disruption which apparently results in permeabilization of the outer membrane, facilitating uptake of aminoglycosides in the periplasmic space. Accordingly, uptake across the outer membrane was termed “self-promoted uptake” (9–11). It was suggested that divalent cations might prevent (antagonize) self-promoted uptake by competing with aminoglycosides for the binding to lipopolysaccharides (9–11).

Entry of aminoglycosides into the cytoplasm across the inner membrane involves an energy-dependent transport (3, 4). It is presumed that cations may antagonize this transport by competing with antibiotics for binding to some membrane component (3). It was also shown that cations appeared to inhibit uptake of aminoglycosides in Staphylococcus aureus and in spheroplasts of Escherichia coli, confirming the hypothesis that the inner membrane may indeed be a site for cation antagonism (3).

Until recently, aminoglycosides were among the rare classes of antibiotics for which no active extrusion due to activity of multidrug resistance (MDR) pumps (26–28, 30) had been demonstrated. This was changed by the discovery of the MDR pump AmrAB-OprA in Burkholderia pseudomallei (23). It has been shown that inactivation of either amrA or amrB resulted in a significant increase in susceptibility to various aminoglycosides. Like many previously discovered MDR pumps from gram-negative bacteria, AmrAB-OprA appears to be a three-component structure containing a transporter (AmrB) located in the cytoplasmic membrane, an outer membrane channel (OprA), and a periplasmic linker protein (AmrA), which is thought to bring the other two components into contact (37–39). This structural organization allows extrusion of substrates, such as aminoglycosides, directly into the external medium, thus bypassing the periplasm (37). More recently, two other aminoglycoside pumps were discovered: single-component AcrD in E. coli (35) and tripartite MexXY-OprM in P. aeruginosa (2, 36). In addition to aminoglycosides, the latter pump can also extrude fluoroquinolones, macrolides, and tetracyclines (2, 20). Thus, MexXY-OprM has become the fourth MDR pump to be identified in P. aeruginosa (30). Interestingly, this tripartite pump employs as its outer membrane component the protein OprM, which was previously found to function as an essential part of another MDR system, MexAB-OprM (31, 32). The gene oprM is located immediately downstream of the mexAB genes and can be transcribed either together with them or independently (33, 40). In the latter case, transcription is initiated from the promoter located inside the mexB sequence. In contrast to the mexAB genes, the mexXY genes are not located near oprM in the chromosome.

The mexXY operon appears to be negatively regulated by the upstream, divergently transcribed gene mexZ (also called amrR), since insertional inactivation of mexZ results in the increased expression of mexXY (36). It also appears that additional genes may be involved in the regulation of mexXY since several reported spontaneous aminoglycoside resistant mutants with elevated expression of mexXY isolated under laboratory conditions did not contain mutations in mexZ (36).

Importantly, the clinical relevance of the MexXY-OprM-mediated efflux of aminoglycosides has been established: elevated expression of the mexXY genes has been detected in clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa exhibiting the impermeability-type resistance, which can be defined as panaminoglycoside resistance in the absence of modifying enzymes (36). It is noteworthy that in the case of P. aeruginosa, impermeability is the most common mechanism of resistance to these antibiotics (22). While it appears that the impermeability type of resistance is a multifactorial phenomenon, the MexXY-OprM efflux pump may prove to be its essential component.

As is evident from the facts described above, multiple intrinsic mechanisms affecting susceptibility to aminoglycosides may coexist in a single cell of P. aeruginosa. In our study we sought to investigate interplay between decreased uptake and increased efflux. To do so, we studied the effects of divalent cations, Mg2+ and Ca2+, on susceptibility to aminoglycosides in the wild-type strain of P. aeruginosa and in mutants overexpressing or lacking the MexXY-OprM efflux pump. Unexpectedly, antagonism of aminoglycosides by divalent cations was seen only in the strains of P. aeruginosa that contained the functional MexXY-OprM efflux pump. We have concluded that such antagonism occurs only in the presence of active efflux of aminoglycosides.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

All strains used in this study (Table 1) are derivatives of PAM1020 (17). The laboratory bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacterial cells were grown in L broth (1% [wt/vol] tryptone, 0.5% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 0.5% [wt/vol] NaCl) or L agar (L broth plus 1.5% agar) at 37°C. Levofloxacin was synthesized at Daiichi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Arbekacin was from Meiji Seika (Osaka, Japan), and netilmicin was a gift from Schering-Plough. MC-207,110 was from the synthetic compound library of Microcide Pharmaceuticals, Inc. MC-005,556 (alanine β-naphthylamide [Ala-Nap]) was synthesized at Microcide Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotypea | Construction, selection, source, or referenceb |

|---|---|---|

| PAM1020 | PAO1 prototroph | 17 |

| PAM1154 | oprM::ΩHg | 17 |

| HN1020 | PAO1 mexX::Tn501 | 2 |

| PAM2378 | mexX::Tn501 | PAM1020 × (HN1020); HgCl2 |

| PAM1106 | mexA::Tet | 17 |

| PAM2380 | mexA::Tet mexX::Tn501 | PAM1106 × (HN1020); HgCl2 |

| PAM2391 | pMexXY | PAM1020/pMexXY; Cb |

| PAM2394 | mexA::Tet mexX::Hg pMexXY | PAM2380/pXY; Cb |

| PAM1032 | nalB | 17 |

| PAM1147 | nalB mxyR1 | Selection on LBA + levofloxacin at 1 μg/ml and MC-207, 110c at 10 μg/ml from PAM1032 |

| PAM1660 | oprM::ΩHg mxyR1 | PAM1147 × (PAM1154); HgCl2 |

| PAM2381 | mexX::Tn501 mxyR1 | PAM1147 × (PAM2378); HgCl2 |

| PAM1174 | mexA::Tet mxyR1 | PAM1147 × (PAM1106); Tc |

| PAM1415 | amr1 | Selection on LBA + gentamicin at 5 μg/ml from PAM1020 |

| PAM2573 | amr1 oprM::ΩHg | PAM1415 × (PAM1154); HgCl2 |

| PAM2574 | amr1 mexX::Tn501 | PAM1415 × (PAM2378); HgCl2 |

Tn501, transposon which confers resistance to HgCl2; ΩHg, HgCl2 resistance derivative of interposon Ω; mxyR1, unidentified mutation resulted in up-regulation of the mexXY operon; amr1, unidentified mutation resulted in the mexXY-independent resistance to aminoglycosides.

In descriptions of transduction experiments, the first strain is the recipient, and the strain in parentheses is the source of a transducing lysate. The antibiotic used for selection of transductants or transformants is shown. Cb, carbenicillin resistance; Tc, tetracycline resistance; LBA, L agar.

MC-207,110 is an inhibitor of Mex pumps from P. aeruginosa.

The strains lacking a functional MexXY-OprM efflux pump were obtained by insertional inactivation of the mexX or oprM genes by transducing the mexX::Hg or oprM::Hg constructs. All transductions were performed using phage F116F (12).

MIC determinations.

MIC determinations were carried out in 96-well microtiter plates using a twofold standard broth microdilution method (25) in Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco). Inocula in all experiments were 104 to 105 cells/ml. Interactions between antibiotics and Mg2+, Ca2+, or MC-207,110 were assessed using twofold dilution schemes in both directions. Aminoglycosides or levofloxacin was dispensed alone in the first row and was combined with either cations or MC-207,110 in the remaining rows. Cations or MC-207,110 was also dispensed alone in the first column. The highest concentrations of both divalent cations and MC-207,110 were 8 mM and 64 μg/ml, respectively. Results are presented for the four concentrations of cations and MC-207,110.

MC-005,556 (Ala-Nap) uptake assays.

Ala-Nap, which is not fluorescent in solution, is cleaved enzymatically inside the cells to produce highly fluorescent β-naphthylamine (18, 34). The more Ala-Nap that enters the cells, the more fluorescence is produced. To assess uptake of Ala-Nap, cultures of P. aeruginosa were grown in L broth to an optical density at 600 nm of ∼1, washed, and resuspended in buffer at pH 7.0 containing 50 mM K2HPO4 and 0.4% glucose. Assays were performed in 96-well flat-bottom black plates (Applied Scientific or Costar) in a final volume of 200 μl and were initiated by the addition of Ala-Nap to suspensions of intact cells to a final concentration of 128 μg/ml. Fluorescence was measured on an fMAX spectrofluorometer (Molecular Devices) using an excitation wavelength of 320 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm. To measure the effects of Mg2+ (MgSO4) on the rate of Ala-Nap uptake, cells were preincubated with different concentrations of Mg2+ prior to the addition of Ala-Nap.

RESULTS

Creation of isogenic strains containing or lacking a functioning MexXY-OprM efflux pump.

We have constructed a set of isogenic strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa expressing various levels of the MexXY-OprM efflux pump. All strains have been derived from the wild-type strain PAM1020 (17). The strains PAM2378 and PAM1154 contained mexX::Hg and oprM::Hg insertions, respectively. As expected, both mutants demonstrated increased susceptibility to aminoglycosides compared to PAM1020 (Table 2), indicating that the MexXY-OprM efflux pump in the mutants was indeed nonfunctional.

TABLE 2.

Effect of Mg2+ on susceptibility to aminoglycosides in various strainsa

| Drug | Strain | Description | MIC (μg/ml) with Mg2+ at:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 mM | 2 mM | 0.5 mM | 0 mM | |||

| Gentamicin | PAM1020 | Wild type | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| PAM1032 | nalB | 4 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | |

| PAM1154 | PAM1020 oprM::ΩHg | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.13 | |

| PAM2378 | PAM1020 mexX::Tn501 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |

| PAM1147 | PAM1032 mxyR1 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 4 | |

| PAM1660 | PAM1147 oprM::ΩHg | 0.5 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.25 | |

| PAM2381 | PAM1147 mexX::Tn501 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |

| Arbekacin | PAM1020 | wild type | 4 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| PAM1032 | nalB | 2 | 0.5 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |

| PAM1154 | PAM1020 oprM::ΩHg | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |

| PAM2378 | PAM1020 mexX::Tn501 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |

| PAM1147 | PAM1032 mxyR1 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| PAM1660 | PAM1147 oprM::ΩHg | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |

| PAM2381 | PAM1147 mexX::Tn501 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| Apramycin | PAM1020 | wild type | 32 | 4 | 1 | 0.5 |

| PAM1032 | nalB | 16 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | |

| PAM1154 | PAM1020 oprM::ΩHg | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| PAM2378 | PAM1020 mexX::Tn501 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| PAM2391 | PAM1020/pMexXY | 64 | 8 | 1 | 0.5 | |

| PAM1147 | PAM1032 mxyR1 | 32 | 8 | 4 | 4 | |

| PAM2381 | PAM1147 mexX::Tn501 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| Amikacin | PAM1020 | wild type | 8 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 |

| PAM1032 | nalB | 8 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | |

| PAM1154 | PAM1020 oprM::ΩHg | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| PAM2378 | PAM1020 mexX::Tn501 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| PAM2391 | PAM1020/pMexXY | 32 | 4 | 1 | 0.5 | |

| PAM1147 | PAM1032 mxyR1 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 4 | |

| PAM1660 | PAM1147 oprM::ΩHg | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| PAM2381 | PAM1147 mexX::Tn501 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| Netilmicin | PAM1020 | wild type | 16 | 4 | 1 | 0.5 |

| PAM1032 | nalB | 16 | 4 | 1 | 0.5 | |

| PAM1154 | PAM1020 oprM::ΩHg | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| PAM2378 | PAM1020 mexX::Tn501 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| PAM2391 | PAM1020/pMexXY | 16 | 16 | 2 | 1 | |

| PAM1147 | PAM1032 mxyR1 | 32 | 8 | 4 | 4 | |

| PAM1660 | PAM1147 oprM::ΩHg | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | |

| PAM2381 | PAM1147 mexX::Tn501 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | |

| PAM1415 | PAM1020 amr1 | >16 | >16 | 4 | 2 | |

| PAM2573 | PAM1415 oprM::ΩHg | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| PAM2574 | PAM1415 mexX::Tn501 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

Mg2+ antagonized aminoglycosides only in strains of P. aeruginosa that contain a functioning MexXY-OprM efflux pump.

To obtain a strain overexpressing mexXY, we attempted selection on plates containing aminoglycosides (gentamicin and netilmicin). However, mutants obtained during such selection apparently had an increased resistance to aminoglycosides that was not due to overexpression of mexXY. A typical representative of the mutants was the strain PAM1415 (selected from PAM1020 on L-agar plates containing gentamicin at 5 μg/ml). This strain was resistant to multiple aminoglycosides after multiple passages on nonselective media. However, inactivation of the mexX (PAM2574) or oprM (PAM2573) gene in this strain did not completely reverse resistance to aminoglycosides (Table 2). This indicated that increased resistance to aminoglycosides in this strain was not due to overproduction of MexXY-OprM. Some decrease in resistance after inactivation of MexXY-OprM appears to be due to a decrease in the intrinsic resistance conferred by the MexXY-OprM pump operating in the PAM1415 background.

The strain with apparently higher levels of MexXY-OprM activity was found among the mutants isolated in an independent project. This strain, PAM1147, was originally selected from PAM1032 (nalB, overexpressing the MexAB-OprM pump) in the course of isolating mutants of P. aeruginosa that were resistant to levofloxacin potentiation by an efflux pump inhibitor, MC-207,110 (18, 34). Mutants were selected on L-agar plates containing levofloxacin at 1 μg/ml and MC-207,110 at 10 μg/ml. (It is noteworthy that 10 μg of MC-207,110/ml is capable of decreasing the MIC of levofloxacin for PAM1032 from 2 to 0.125 μg/ml [18, 34].) Not only was PAM1147 resistant to potentiation (O. Lomovskaya, unpublished data), but also MICs of various aminoglycosides for this strain were increased (Table 2). Inactivation of mexX (PAM2381) or oprM (PAM1660) in PAM1147 reversed observed resistance to the level seen for the strains PAM2378 (PAM1020 mexX::Hg) and PAM1154 (PAM1020 oprM::Hg). These results implicated MexXY-OprM in the aminoglycoside resistance seen in PAM1147. Interestingly, the mexX::Hg derivative of PAM1147 (PAM2381) was still resistant to potentiation by MC-207,110 (W. Mao and O. Lomovskaya, unpublished data), indicating that it was not the MexXY-OprM pump that conferred resistance to potentiation with MC-207,110 on this strain. The most likely explanation is that a single regulatory mutation is responsible for the two independent phenotypes.

To obtain another strain with an increased MexXY activity, we transformed PAM1020 with the multicopy plasmid pMexXY containing the cloned mexXY operon (also called pAGH97; kindly provided by P. Plesiat and H. Nikaido). For the resulting strain, PAM2391, MICs of aminoglycosides and levofloxacin were slightly increased compared to those for PAM1020, indeed indicating higher activity of MexXY (Tables 2 to 4).

TABLE 4.

Effect of MC-207,110 on susceptibility to levofloxacin and aminoglycosides in various strainsa

| Drug | Strain | Description | MIC (μg/ml) with MC-207,110 at:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 μg/ml | 16 μg/ml | 4 μg/ml | 0 μg/ml | |||

| Levofloxacin | PAM1020 | Wild type | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.13 |

| PAM1032 | nalB | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.06 | 1 | |

| PAM1147 | PAM1032 mxyR1 | 0.03 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| PAM2381 | PAM1147 mexX::Tn501 | 0.03 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| PAM2391 | PAM1020/pMexXY | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.03 | 0.25 | |

| PAM1154 | PAM1020 oprM::ΩHg | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.015 | |

| Amikacin | PAM1020 | wild type | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| PAM2391 | PAM1020/pMexXY | 2 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.25 | |

| PAM1154 | PAM1020 oprM::ΩHg | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.13 | |

| Netilmicin | PAM1020 | wild type | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| PAM2391 | PAM1020/pMexXY | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | |

| PAM1154 | PAM1020 oprM::ΩHg | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

MC-207,110 potentiated levofloxacin and antagonized aminoglycosides. An antagonistic effect was seen only in strains of P. aeruginosa that contain a functioning MexXY-OprM efflux pump. Similar results were obtained for apramycin and arbekacin.

Effect of divalent cations on susceptibility to aminoglycosides in strains containing or lacking a functioning MexXY-OprM efflux pump.

Next, we determined the impact of various concentrations of Mg2+ and Ca2+ on the MICs of gentamicin, streptomycin, amikacin, apramycin, netilmicin, and arbekacin in the strains containing or lacking a functioning MexXY-OprM efflux pump. We unexpectedly found that both Mg2+ and Ca2+ antagonized all tested aminoglycosides only in the strains of P. aeruginosa that contained a functioning MexXY-OprM efflux pump: almost no antagonism was seen at concentrations of Mg2+ and Ca2+ up to 8 mM for the mexX::Hg or oprM::Hg derivatives of any of the mutants (Tables 2 and 3). This was the case regardless of other mutations present in these strains. For example, in the strain PAM1415, an increase in resistance to aminoglycosides was not due to elevated production of MexXY-OprM. Still, introduction of either mexX::Hg or oprM::Hg in PAM1415 prevented Mg2+ antagonism (Table 2). Deleting mexX::Hg or oprM::Hg was also sufficient to prevent Mg2+ and Ca2+ antagonism in PAM1147.

TABLE 3.

Effect of Ca2+ on susceptibility to gentamicin in various strains

| Strain | Description | MIC of gentamicin (μg/ml) with Ca2+ at:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 mM | 2 mM | 0.5 mM | 0 mM | ||

| PAM1020 | Wild type | >16 | 8 | 1 | 0.25 |

| PAM1032 | nalB | 16 | 4 | 1 | 0.25 |

| PAM1154 | PAM1020 oprM::ΩHg | 0.5 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| PAM2378 | PAM1020 mexX::Tn501 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| PAM1147 | PAM1032 mxyR1 | >16 | 16 | 8 | 2 |

| PAM1660 | PAM1147 oprM::ΩHg | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| PAM2381 | PAM1147 mexX::Tn501 | 0.5 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

Effect of Mg2+ on uptake of Ala-Nap (MC-005,556) in strains containing or lacking a functioning MexXY-OprM efflux pump.

It was important to know whether a functioning MexXY-OprM pump was required for Mg2+ effects on other substrates of this pump. Fluoroquinolones and tetracycline are among these substrates (2, 20); however, in these cases the interpretation of Mg2+ effects could be difficult, since these compounds are known to chelate divalent cations (13, 14).

We have previously demonstrated that Ala-Nap (MC-005,556) is a substrate of the MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, and MexEF-OprN pumps from P. aeruginosa and the AcrAB-TolC pump from E. coli (18). This compound proved to be very useful for real-time uptake assays, since it is easily detected inside the cell. It is not fluorescent in solution but is cleaved enzymatically inside the cells to produce the highly fluorescent β-naphthylamine. The rate of production of β-naphthylamine (recorded as an increase in fluorescence) is limited only by the net rate of appearance of Ala-Nap inside the cytoplasm. This net rate in turn reflects the difference between the rate of influx and the rate of efflux. Consequently, the strains overexpressing efflux pumps produced fluorescent β-naphthylamine at much lower rates than the strains lacking efflux pumps (18).

We sought to determine whether Ala-Nap is a substrate of the MexXY-OprM efflux pump and, if so, to study the effect of Mg2+ on its uptake. To do so we compared the rate of uptake of Ala-Nap in PAM2380, which lacks both the MexAB-OprM and the MexXY-OprM efflux pumps, and in PAM2394, which is PAM2380 containing the pMexXY plasmid.

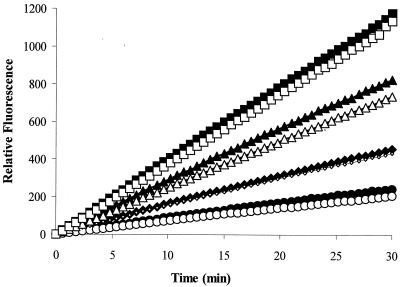

When no external Mg2+ was added, no difference in Ala-Nap uptake between the two strains was detected over a wide range of Ala-Nap concentrations (Fig. 1). This indicated that either Ala-Nap was not extruded by MexXY-OprM at all or its rate of uptake was simply higher than that of MexXY-OprM-mediated efflux.

FIG. 1.

Uptake of MC-005,556 (Ala-Nap) with no Mg2+ added by cells of P. aeruginosa overexpressing or lacking the MexXY-OprM efflux pump. Ala-Nap was added to intact cells of P. aeruginosa either overexpressing MexXY-OprM (PAM2394, open symbols) or lacking this pump (PAM2380, filled symbols). A similar linear increase in fluorescence with time due to intracellular hydrolysis of MC-005,556 (Ala-Nap) is seen over a wide range of Ala-Nap concentrations (32 [circles], 64 [diamonds], 128 [triangles], and 256 [squares] μg/ml) for both cell types.

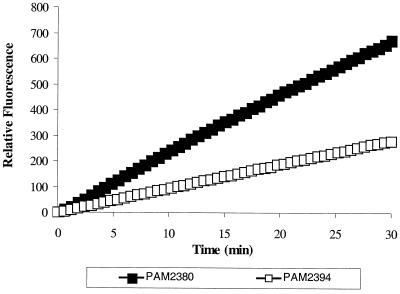

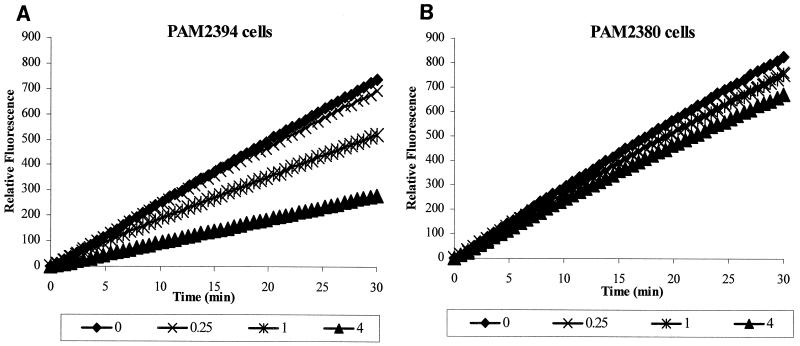

Next, we repeated uptake experiments in the presence of Mg2+. Under these conditions, the rate of Ala-Nap uptake was lower for the pMexXY-containing strain PAM2394, indicating MexXY-OprM-mediated efflux of Ala-Nap (Fig. 2). Importantly, while the addition of Mg2+ was capable of decreasing the uptake of Ala-Nap (antagonized uptake) in the strain containing a functioning MexXY-OprM efflux pump, no significant impact of Mg2+ on Ala-Nap was seen in the MexXY-OprM-lacking strain (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Uptake of MC-005,556 in the presence of 4 mM Mg2+ by cells of P. aeruginosa overexpressing or lacking the MexXY-OprM efflux pump. Differential rates of uptake of Ala-Nap between cells overexpressing the pump (PAM2394) and those lacking it (PAM2380) are seen.

FIG. 3.

Effect of Mg2+ on uptake of MC-005,556 in intact cells of P. aeruginosa overexpressing or lacking the MexXY-OprM efflux pump. (A) Decrease in rates of fluorescence production by cells of P. aeruginosa overexpressing the MexXY-OprM pump (PAM2394) is seen in the presence of different concentrations of Mg2+. (B) No effect of Mg2+ is observed for cells of PAM2380, which lack constitutively expressed MexAB-OprM and MexXY-OprM efflux pumps.

Effect of MC-207,110 on susceptibility to aminoglycosides in strains containing or lacking a functioning MexXY-OprM efflux pump.

MC-207,110 has been recently identified as an inhibitor of MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, and MexEF-OprN efflux pumps from P. aeruginosa and the AcrAB-TolC pump from E. coli (18, 34). This compound has been shown to potentiate multiple antibiotics, which are substrates of these pumps.

To learn whether this compound could also inhibit MexXY-OprM, we studied the impact of this compound on susceptibility to aminoglycosides in strains either lacking or overexpressing this efflux pump. Checkerboard experiments demonstrated that instead of synergy, which would be expected in the case of pump inhibition, there was clear antagonism between aminoglycosides (as exemplified by apramycin and netilmicin) and MC-207,110. Furthermore, MC-207,110, similar to Mg2+, antagonized the activity of aminoglycosides only in the strains that contained a functioning MexXY-OprM efflux pump (Table 4). The degree of antagonism was higher in strains with an elevated level of MexXY-OprM expression.

DISCUSSION

This work was inspired by our long-standing interest in relationships between different mechanisms of resistance to a particular antibiotic that can coexist in the same bacterial cell. Studies performed both by us and by others demonstrated that the combined presence of two mechanisms might confer either multiplicative (the fold increase in MIC due to combined presence is close to the product of individual fold increases) or additive (the fold increase in MIC is a sum of the individual fold increases) effects on drug resistance. Examples of the multiplicative case include interplay between efflux-based and target-mediated resistance to fluoroquinolones in P. aeruginosa (17) and E. coli (29) and between multicomponent and single-component efflux pumps in resistance to antibiotics, which are substrates of these pumps (15). The additive case is exemplified by the interplay between efflux pumps and β-lactamases in resistance to various β-lactam antibiotics (19, 24). In this particular study we sought to investigate the interplay between increased efflux and decreased uptake in resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics in P. aeruginosa. It is noteworthy that active extrusion of aminoglycosides from bacterial cells was discovered quite recently: tripartite pumps, AmrAB-OprA (23) and MexXY-OprM (2, 36), were identified in B. pseudomallei and P. aeruginosa, respectively, and a single-component pump, AcrD, was found in E. coli (35).

To determine the effects of decreased permeability on the observed susceptibility to aminoglycosides in the strains either lacking or containing the functional MexXY-OprM pump, we decided to vary the concentration of divalent cations in the test media. This approach was based on numerous literature reports indicating that the well-known antagonistic effect between divalent cations, such as Mg2+ and Ca2+, and aminoglycosides occurs due to the interference of cations with the uptake of aminoglycosides at the level of both outer and inner membranes (3, 5, 41). Our results demonstrated that divalent cations antagonized aminoglycosides only when the MexXY-OprM efflux pump was functional. An analogous effect was seen in accumulation assays with a different substrate of the MexXY-OprM pump, Ala-Nap. Like Mg2+, MC-207,110, a cationic dipeptide which was previously identified as an inhibitor of Mex pumps (18, 34), antagonized aminoglycosides in a MexXY-OprM-dependent manner.

There seem to be two different explanations for the requirement of an efflux pump for the antagonism between divalent metals (or MC-207,110) and aminoglycosides. The simplest possibility is that divalent metals and the cationic compound MC-207,110 compete with cationic aminoglycosides for binding at the outer membrane, and inhibit antibiotic penetration into the periplasm. However, this inhibition of antibiotic penetration is observed only when an opposing active efflux via an MDR pump is present. In the absence of an MDR pump, the rate of accumulation of the aminoglycoside can be decreased by another cation, but this will not affect the final concentration of the antibiotic in the cytoplasm and will have no effect on the MIC. Indeed, the outer membrane barrier is functional only in the presence of MDR pumps that extrude compounds across this barrier. For example, inhibition of efflux pumps or their mutational inactivation renders cells hypersensitive to antibiotics even in the presence of an intact outer membrane. The opposite is also true. In the case of many compounds that are substrates of Mex pumps, permeabilization of the outer membrane of P. aeruginosa dramatically increases the susceptibility (16) and/or increases the rates of uptake of these compounds (8), regardless of the presence of functioning efflux pumps. These results confirmed the now generally accepted paradigm of a synergistic interaction between increased efflux due to tripartite multidrug resistance pumps, extruding antibiotics in the external medium, and decreased uptake though the outer membrane to confer resistance to some antibiotics (37).

It is noteworthy that in E. coli, which possesses its own aminoglycoside pump, AcrD, antagonism of aminoglycosides by 5 mM Mg2+ was not increased in the presence of AcrD compared to that in its absence (35). AcrD most probably is a single-component pump, extruding aminoglycosides in the periplasmic space. If antagonism occurs mainly at the level of the outer membrane, then one should not expect that such a pump would be essential for the manifestation of an antagonistic effect.

Another possibility is that divalent metals or MC-207,110 directly activates efflux of aminoglycosides and Ala-Nap by MexXY-OprM. In the case of Ala-Nap, we measured the effect of Mg2+ on its uptake kinetics. Interestingly, we did not detect the MexXY-OprM-dependent efflux of Ala-Nap when no external Mg2+ was added to the assay buffer: strains lacking and expressing MexXY-OprM converted Ala-Nap at the same rate. The difference between the two strains became apparent in the presence of Mg2+, but only because it decreased the apparent initial rate of Ala-Nap uptake in the strain containing the MexXY-OprM pump: no Mg2+ effect was seen in the absence of the pump.

To assess the possibility that Mg2+ can directly facilitate efflux of aminoglycosides, we are planning to study the effects of Mg2+ on accumulation kinetics of aminoglycosides using the strains lacking or overexpressing MexXY-OprM. We are also attempting to isolate mutants containing changes in the pump genes resulting in an altered response to Mg2+.

From a practical point of view, our findings indicate that inhibition of the MexXY-OprM efflux pump from P. aeruginosa should abolish antagonism of aminoglycosides by divalent cations regardless of its precise mechanism. This should significantly improve the clinical utility of this important class of antibiotics. We attempted to demonstrate this directly by using our recently identified efflux pump inhibitor, MC-207,110. Unfortunately, instead of synergy, we observed an antagonistic effect of MC-207,110, most probably due to a similar mechanism to that for divalent cations. Our studies indicate that identifying a MexXY-OprM inhibitor that will block the efflux of aminoglycosides will be of significant therapeutic value.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to George Miller, Mike Dudley, and Pat Martin for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Hiroshi Nikaido and Patrick Plesiat for providing the plasmid pAGH97 (pMexXY) and the mexX::Hg mutant. We are also indebted to Hiroshi Nikaido for sharing his acrD results prior to publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdel-Sayed S, Gonzalez M, Eagon R. The role of the outer membrane of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the uptake of aminoglycoside antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1982;10:173–183. doi: 10.1093/jac/10.3.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aires J R, Kohler T, Nikaido H, Plesiat P. Involvement of an active efflux system in the natural resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to aminoglycosides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2624–2628. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.11.2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryan L E, Van Den Elzen H M. Effects of membrane-energy mutations and cations on streptomycin and gentamicin accumulation by bacteria: a model for entry of streptomycin and gentamicin in susceptible and resistant bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1977;12:163–177. doi: 10.1128/aac.12.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryan L E, Van Den Elzen H M. Streptomycin accumulation in susceptible and resistant strains of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1976;9:928–938. doi: 10.1128/aac.9.6.928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell B, Kadner R J. Relation of aerobiosis and ionic strength to the uptake of dihydrostreptomycin in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;593:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(80)90002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Amato R F, Thornsberry C, Baker C N, Kirven L A. Effect of calcium and magnesium ions on the susceptibility of Pseudomonas species to tetracycline, gentamicin, polymyxin B, and carbenicillin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1975;7:596–600. doi: 10.1128/aac.7.5.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Day D. Gentamicin-lipopolysaccharide interactions in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Curr Microbiol. 1980;4:277–281. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Germ M, Yoshihara E, Yoneyama H, Nakae T. Interplay between the efflux pump and the outer membrane permeability barrier in fluorescent dye accumulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;261:452–455. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hancock R, Bell A. Antibiotic uptake in gram-negative bacteria. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1988;7:713–720. doi: 10.1007/BF01975036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hancock R, Raffle V, Nicas T. Involvement of the outer membrane in gentamicin and streptomycin uptake and killing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981;19:777–785. doi: 10.1128/aac.19.5.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hancock R E. Resistance mechanisms in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other nonfermentative gram-negative bacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(Suppl. 1):S93–S99. doi: 10.1086/514909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishnapillai V. A novel transducing phage. Its role in recognition of a possible new host-controlled modification system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Gen Genet. 1972;114:134–143. doi: 10.1007/BF00332784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambs L, Venturini M, Decock-Le Reverend B, Kozlowski H, Berthon G. Metal ion-tetracycline interactions in biological fluids. Part 8. Potentiometric and spectroscopic studies on the formation of Ca(II) and Mg(II) complexes with 4-dedimethylamino-tetracycline and 6-desoxy-6- demethyl-tetracycline. J Inorg Biochem. 1988;33:193–210. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(88)80049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lecomte S, Baron M H, Chenon M T, Coupry C, Moreau N J. Effect of magnesium complexation by fluoroquinolones on their antibacterial properties. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2810–2816. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.12.2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee A, Mao W, Warren M, Mistry A, Hoshino K, Okumura R, Ishida H, Lomovskaya O. Interplay between efflux pumps may provide either additive or multiplicative effects on drug resistance. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3142–3150. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.11.3142-3150.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X, Zhang L, Poole K. Interplay between the MexA-MexB-OprM multidrug efflux system and the outer membrane barrier in the multiple antibiotic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;45:433–436. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lomovskaya O, Lee A, Hoshino K, Ishida H, Mistry A, Warren M S, Boyer E, Chamberland S, Lee V J. Use of a genetic approach to evaluate the consequences of inhibition of efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1340–1346. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.6.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lomovskaya O, Warren M, Lee A, Galazzo J, Fronko R, Lee M, Blais J, Cho D, Chamberland S, Renau T, Leger R, Hecker S, Watkins W, Ishida H, Hoshino K, Lee V. Identification and characterization of efflux pump inhibitors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2001;45:105–116. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.1.105-116.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masuda N, Gotoh N, Ishii C, Sakagawa E, Ohya S, Nishino T. Interplay between chromosomal beta-lactamase and the MexAB-OprM efflux system in intrinsic resistance to beta-lactams in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:400–402. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masuda N, Sakagawa E, Ohya S, Gotoh N, Tsujimoto H, Nishino T. Contribution of the MexXY-OprM efflux system to intrinsic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2242–2246. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.9.2242-2246.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medeiros A, O'Brien T, Wacker W, Yulug N. Effect of salt concentration on the apparent in vitro susceptibility of Pseudomonas and other gram-negative bacilli to gentamicin. J Infect Dis. 1971;124:59–64. doi: 10.1093/infdis/124.supplement_1.s59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller G H, Sabatelli F J, Hare R S, Glupczynski Y, Mackey P, Shlaes D, Shimizu K, Shaw K J. The most frequent aminoglycoside resistance mechanisms—changes with time and geographic area: a reflection of aminoglycoside usage patterns? Aminoglycoside Resistance Study Groups. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24(Suppl. 1):S46–S62. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.supplement_1.s46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore R A, DeShazer D, Reckseidler S, Weissman A, Woods D E. Efflux-mediated aminoglycoside and macrolide resistance in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:465–470. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.3.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakae T, Nakajima A, Ono T, Saito K, Yoneyama H. Resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics in Pseudomonas aeruginosa due to interplay between the MexAB-OprM efflux pump and beta-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1301–1303. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 4th ed. Approved standards. NCCLS document M7–A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nikaido H. Antibiotic resistance caused by gram-negative multidrug efflux pumps. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(Suppl. 1):S32–S41. doi: 10.1086/514920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikaido H. Multidrug efflux pumps of gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5853–5859. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.5853-5859.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nikaido H. Multiple antibiotic resistance and efflux. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1998;1:516–523. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(98)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oethinger M, Kern W V, Jellen-Ritter A S, McMurry L M, Levy S B. Ineffectiveness of topoisomerase mutations in mediating clinically significant fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli in the absence of the AcrAB efflux pump. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:10–13. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.1.10-13.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poole K. Efflux-mediated resistance to fluoroquinolones in gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2233–2241. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.9.2233-2241.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poole K, Heinrichs D E, Neshat S. Cloning and sequence analysis of an EnvCD homologue in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: regulation by iron and possible involvement in the secretion of the siderophore pyoverdine. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:529–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poole K, Krebes K, McNally C, Neshat S. Multiple antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: evidence for involvement of an efflux operon. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7363–7372. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.22.7363-7372.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poole K, Tetro K, Zhao Q, Neshat S, Heinrichs D E, Bianco N. Expression of the multidrug resistance operon mexA-mexB-oprM in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mexR encodes a regulator of operon expression. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2021–2028. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.9.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renau T E, Leger R, Flamme E M, Sangalang J, She M W, Yen R, Gannon C L, Griffith D, Chamberland S, Lomovskaya O, Hecker S J, Lee V J, Ohta T, Nakayama K. Inhibitors of efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa potentiate the activity of the fluoroquinolone antibacterial levofloxacin. J Med Chem. 1999;42:4928–4931. doi: 10.1021/jm9904598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenberg E, Ma D, Nikaido H. AcrD of Escherichia coli is an aminoglycoside efflux pump. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1754–1756. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1754-1756.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westbrock-Wadman S, Sherman D R, Hickey M J, Coulter S N, Zhu Y Q, Warrener P, Nguyen L Y, Shawar R M, Folger K R, Stover C K. Characterization of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa efflux pump contributing to aminoglycoside impermeability. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2975–2983. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.12.2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zgurskaya H, Nikaido H. Multidrug resistance mechanisms: drug efflux across two membranes. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:219–225. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zgurskaya H I, Nikaido H. AcrA is a highly asymmetric protein capable of spanning the periplasm. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:409–420. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zgurskaya H I, Nikaido H. Bypassing the periplasm: reconstitution of the AcrAB multidrug efflux pump of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7190–7195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao Q, Li X Z, Srikumar R, Poole K. Contribution of outer membrane efflux protein OprM to antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa independent of MexAB. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1682–1688. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zimelis V, Jackson G. Activity of aminoglycoside antibiotics against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: specificity and site of calcium and magnesium antagonism. J Infect Dis. 1973;127:663–669. doi: 10.1093/infdis/127.6.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]