Abstract

Background

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many mothers and fathers have spent more time at home with their children, warranting consideration of parenting practices around food during the pandemic as influences on obesogenic eating behaviors among children. Structure-related feeding practices, particularly around snacking, may be particularly challenging yet influential in the pandemic setting. Parent sex and levels of feeding-related co-operation among parents (co-feeding) are understudied potential influences on parent-child feeding relationships.

Methods

We investigated relationships between structure-related parent feeding and child food approach behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic, while considering potential moderating influences of parent sex and co-feeding levels. An online survey was completed by 318 parents (206 mothers and 112 fathers) of 2-12-year-olds who were living in states with statewide or regional lockdowns in May/June 2020 within the US. Mothers and fathers were drawn from different families, with each survey corresponding to a unique parent-child dyad. Parental stress/mental health, co-feeding (Feeding Coparenting Scale), structure-related food and snack parenting (Feeding Practices and Structure Questionnaire and Parenting around SNAcking Questionnaire), and child eating behaviors (Child Eating Behaviour Questionnaire) were assessed. Relationships of parents’ structure-related food and snack parenting practices with their child's emotional overeating and food responsiveness behaviors were examined using structural equation modelling. Further, we investigated whether these relations were moderated by parent sex or level of co-feeding.

Results

Parent sex differences were seen in parental stress, mental health, and co-feeding, but not in structure-related food and snack parenting or child food approach eating behaviors. Structure-related food parenting was negatively associated with emotional overeating. However, structure-related snack parenting was positively associated with emotional overeating and food responsiveness. While regression paths varied between mothers vs. fathers, as well as by co-feeding levels, neither parent sex nor co-feeding levels significantly moderated relationships between parent feeding and child eating variables.

Conclusions

Future studies of food and snack parenting and co-operation in relation to feeding among mothers and fathers within a familial unit may be critical to identify intervention strategies that draw on all family resources to better navigate future disruptive events such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, Mothers, Fathers, Structure-related feeding, Co-feeding, Child eating

1. Introduction

1.1. Food parenting and child eating behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic caused unprecedented changes to familial routines in the US and globally [1,2]. Mandatory lockdowns and business/school closures [3] required many parents to stay at home with their children for a prolonged time, especially during the early stages of the pandemic [3]. As a consequence, parents and children spent more time together during meals than they usually would [4,5], increasing the potential impact of food parenting practices, especially in the home environment, on obesogenic behaviors among children such as overeating or excess consumption of unhealthy foods [6], [7], [8]. Food parenting practices have been shown to impact children's current and future weight status as well as child eating behaviors [9], [10], [11]. Importantly, food parenting practices represent modifiable factors, being responsive to situational and psychosocial factors such as pandemic-related stress [12] but also to change via intervention [13,14], making them a potential leverage point for decreasing obesogenic impacts of pandemic-associated disruption on children.

1.1.1. Studies of food parenting and child eating behavior during the pandemic

Several studies have investigated food parenting and child eating during the pandemic. One study found that more than 50% of a sample of parents with children aged 18 months – 5 years indicated changed eating and meal routines since the beginning of the pandemic [5]. Eating more snack foods and spending more time cooking were reported as the most frequent changes. Philippe et al. [12] additionally reported that parents of children aged 3-12 years cooked more (home-made meals, with their child). Adams et al. [15] found that in parents of children aged 5-18 years, coercive practices, such as restrictive feeding and pressure to eat, but also monitoring of children's food intake, a less controlling practice, increased from pre-COVID to a first pandemic assessment point and then either returned to pre-COVID levels (restrictive feeding, pressure to eat) or plateaued (monitoring) at a second pandemic assessment point, highlighting the pronounced impact of the early pandemic period. Notably the majority of research (either during the pandemic or before) on this topic thus far has focused on coercive practices, i.e., practices that are less responsive to children's hunger and satiety cues.

1.1.2. Structure-related food parenting practices as a potential influence on child eating behavior during the pandemic

Far fewer studies of food parenting either during the pandemic or pre-pandemic have taken a strength-based approach (i.e. focusing on practices associated with positive outcomes rather than those associated with negative outcomes) by investigating the role of structure-related food parenting practices [16]. Structure within the meal environment has been proposed as beneficial for the development of healthy eating patterns [17,18], especially in combination with responsive feeding [19] (i.e., authoritative feeding). Structure-related food parenting practices, such as Structured Meal Setting (e.g. insisting child eats at table), Structured Meal Timing (e.g. parent decides on timing of meals) and Family Meal Setting (i.e. child eats same meals as rest of family) assessed with the Feeding Practices and Structure Questionnaire (FPSQ) [20,21], have been previously associated with child eating behaviors including lower food fussiness and higher self-regulation in eating [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]. However, less is known about relationships with the food approach behaviors food responsiveness and emotional overeating, those eating behaviors characterized by a greater interest in food.

Consistent with a recognition that structure is generally beneficial for children, UNICEF published Coronavirus (COVID-19) parenting tips [27,28] recommending the provision of daily structured routines for children. Yet, in the study by Philippe et al. [12], the authors found that parents reported adopting more permissive food parenting practices since the start of the pandemic which included having fewer rules, allowing children to be more autonomous, and greater use of food for soothing. The authors additionally reported that during the lockdown, significant increases in child appetite, food enjoyment, food responsiveness and emotional overeating were seen. These results suggest that structure-related food and snack parenting could influence children's food approach during the pandemic. However, structure-related food and snack parenting were not distinguished in this study, and relationships between food parenting and child eating not directly tested.

1.2. Parent sex and co-operation around feeding: potential modifiers of parent-child feeding relationships during the COVID pandemic

Pandemic-associated disruption has not affected all individuals equally. For example, evidence suggests that stress and mental health struggles may have been uniquely exacerbated for parents [29,30] and children [31], [32], [33]. Parents, especially mothers [34,35], have assumed additional child care and schooling responsibilities [3,36], resulting in increased parenting-related exhaustion and decreased parental resilience [37,38]. For some families, the pandemic has highlighted or altered relations within co-parenting partnerships, by increasing or otherwise altering the time that partners spend together parenting their children, and/or foregrounding unequal or sub-optimal dynamics around caregiving responsibilities from one or both partner's perspective [39]. When considering relationships between food parenting practices and child outcomes, it may therefore be important to recognize the contribution of potential sex differences in pandemic experience, and of within-family cooperation around feeding, to parent-child feeding relationships.

1.2.1. Parent sex differences in food parenting

A limited number of studies have reported differences between mothers and fathers in the use of structure-related food parenting practices or other positive parent-child mealtime interactions (e.g., autonomy support practices). Pratt et al. [17] reported that mothers of children aged 2.5-7.5 years indicated higher engagement in both structure-related (e.g., clear rules) and autonomy supportive (e.g., responsive feeding) food parenting practices and more responsibility for food parenting compared to fathers, while fathers were more likely to use coercive food parenting practices (e.g., emotion regulation) than mothers. Hendy et al. [40] also found that fathers (child mean age 4.5 years) were more likely to use coercion/forceful food parenting practices (e.g., insisting on eating) than mothers, while mothers were more likely to provide structure and autonomy support (i.e., limit snacks, make fruits and vegetables available, encourage balance and variety in eating, use persuasion positively to convince children to eat their meals).

1.2.2. Parent sex differences in food parenting during the pandemic

As far as we are aware, no studies have reported on parent sex differences relating to food parenting as measured during the COVID pandemic, similar to non-pandemic times where the majority of related investigations focuses on mothers [41,42]. Due to pandemic-associated factors, fathers may spend more time at home and become more involved in child feeding responsibilities [39]. Alternatively, they may become less involved in feeding if they work more or outside the home, or are unable to fulfill childcare responsibilities due to pandemic-related stressors and mental health issues [43,44]. In terms of structure-related feeding practices, Pratt et al. [17] speculated that a parent with lower food parenting responsibility potentially has less experience or knowledge about implementing positive practices, such as structure and autonomy support. Additionally, when mothers and fathers take on greater responsibility for food parenting, they might exercise preferences for different levels of structure-related food parenting. Furthermore, it is possible that effects of structure on children's eating behavior may differ depending on the parent. For example, fathers may implement structure differently in terms of specific practices, and/or children may respond differently to structure as imposed by fathers compared to mothers due to the child's differing relationship and non-food related experiences with their father as opposed to their mother. Further investigation of food parenting during the COVID-19 pandemic in fathers and mothers is therefore warranted.

1.2.3. Cooperation in food parenting

Implementing structure within the home environment and around mealtimes requires that parents are cooperative and coordinated, share leadership/tasks, work as team and support each other in setting up routines, rules, and limits, all of which form the key characteristics of coparenting [45,46] or coparenting in the feeding context more specifically (i.e., co-feeding) [47], [48], [49], [50], [51]. Two recent publications have shown that co-parenting quality is related to food parenting practices [52,53]. However, neither study examined how feeding co-parenting or ‘co-feeding’ is related to structure-related food parenting practices, or if it is a moderator of relationships between food parenting and child eating behaviors. Since pandemic-associated alterations to the family landscape and parental role-sharing have the potential to turn into long lasting habits, an examination of this kind in pandemic times may have extended relevance to child outcomes.

1.3. The current study

The overarching goal of the current study was to investigate relationships between structure-related parent feeding and child food approach behaviors in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic while considering potential moderating influences of parent sex and co-feeding levels on these relationships. For this analysis we used an online survey (see [54], [55], [56] for further details) that collected data from mothers and fathers drawn from different families, with each survey corresponding to a unique parent-child dyad.

In our first investigation of parent-child interactions [57] using this survey data, we found that higher parental COVID-19-specific stress was associated with more non-nutritive use of food and snacks (e.g., using food to reinforce behavior), more positive food-related parent-child interactions (e.g., eating together with child), and more structure-related snack parenting practices. COVID-19-specific stress was also associated with greater child intake frequency of snacks (sweet and savory), with some evidence for mediation by snack parenting practices [57].

For the current study we adopted a strength-based approach, with a focus on structure-related practices. Our rationale was that these results could inform as to which feeding practices parents should use, rather than which to avoid. Further, rather than child diet, we examined obesogenic child eating behaviors, which are hypothesized to be enduring predictors of dietary intake [58,59]. We assessed both general food parenting and parenting around snacks, which may be particularly pertinent during unstructured pandemic time at home. Finally, we included two moderators, parent sex and parent co-feeding level, which were not considered in our previous publication [57] , or other pandemic research.

We first explored as a preliminary step any reported parent sex differences during the COVID-19 pandemic in co-feeding, structure-related food and snack parenting practices, and perception of child eating behaviors in a sample of parents with children aged 2-12 years (Aim 1). Differences in parental stress/mental health, demographic, socioeconomic and anthropometric characteristics were also examined (Aim 1). Next, we investigated if structure-related food and snack parenting practices were related to food approach eating behaviors in children (i.e., food responsiveness and emotional overeating) during the pandemic (Aim 2). Finally, we tested whether these relationships differed by parent sex and/or reported levels of co-feeding (Aim 3). We hypothesized that provision of structure (e.g., having rules and routines) would be associated with lower food approach eating behaviors in children.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study procedure and sample

Data presented here were gleaned from a larger study investigating the impact of COVID-19 on familial health behaviors via an online survey (Qualtrics) on Amazon's Mechanical Turk (MTurk) and social media from May 26, 2020 to June 29, 2020. Sample recruitment and survey procedures have been previously described in detail [55], [56], [57]. Briefly, parents (18+ years of age) with a child or children ages 2-12 years answered questions regarding parental health, feeding behaviors and child eating behaviors, amongst others. If respondents had more than one child in this age range, they were instructed to answer the questions regarding their youngest child. Respondents were instructed to only complete one survey per family. Initially residents were targeted from states in the US that were under lockdown orders on the date the survey was disseminated (i.e., New Jersey, Delaware, District of Columbia, and Illinois). The survey distribution was then expanded to include states with regional lockdowns (i.e., California, Maine, Michigan, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Washington). Of the 467 participants completing the survey, 325 self-reported being a parent of a child aged 2-12. Of these parents, 318 (206 mothers and 112 fathers) were eligible (7 were omitted due to their child being under the age of 2). All participants provided their informed consent and the study was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board (REF NO. CIR00056262).

2.2. Measures

One parent within a household completed the online survey and provided information about themselves and their children on the following measures.

2.2.1. Demographic, socioeconomic, and anthropometric information, stress and mental health

Parents reported on their own and their child's age and sex, parent employment status, education level, annual household income, relationship status, and race/ethnicity. Participants indicated whether their own work was considered ‘essential’, what effect the pandemic had on regular childcare, and current information relating to food insecurity and receipt of public assistance (e.g., food support/stamps). A socioeconomic disadvantage score was created based on responses for education level, household income, current food insecurity and receipt of public assistance. The socioeconomic disadvantage score ranged from 0 (least disadvantage) to 4 (most disadvantage) [55]. Additionally, parents reported on their own and their child's weight and height, based on which parental BMI and child BMI z-scores and percentiles were calculated using the CDC reference data [60]. Next, parents indicated how stressed they were in general right now and before the pandemic (“In general, how would you rate your level of stress … [before the COVID-19 crisis], [right now]?”). Responses were scored between 0-10, with higher scores indicating more stress. Parents responded to 16 COVID-19-specific stress items (e.g., “How stressed are you about the following in relation to the COVID-19 crisis? - Losing my job, I will get COVID-19, My child will fall behind in school”, Cronbach's α = 0.91) (for specific items, see [57]). Response options ranged from 1 = “Not at all” to 5 = “Extremely”. The scores of all items were averaged with higher scores indicating higher stress levels. Four items were selected from the Parenting Stress Scale [61] to assess both the rewarding (i.e., “I enjoy spending time with my child[ren]”, “I feel close to my children”) and challenging aspects of parenting (i.e., “Caring for my child[ren] sometimes takes more time and energy than I have to give”, “I sometimes worry whether I am doing enough for my child[ren]”) during the pandemic. Response options ranged from 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly agree”. Internal reliability for these 4 items was low (Cronbach's α = 0.54) but item deletion did not produce improvements. The scores were therefore averaged, with higher scores indicating higher stress levels. Finally, parents indicated how often they felt anxious, depressed, lonely or hopeless about the future within the past week, with response options ranging from 1 = “Not at all” to 4 = “5-7 days” [62]. Following recommended scoring methods for the source instruments [63,64], a sum score was calculated across the four items (Cronbach's α = 0.87).

2.2.2. Co-feeding (feeding co-parenting)

One parent within a partnered or married relationship completed two of the three subscales from the Feeding Coparenting Scale [50] to assess how they are working together with their partner/spouse in the child feeding domain: ‘shared positive views and values in child feeding’ (5 items, e.g., “My spouse/partner and I both see family mealtimes as a time to feed our child healthy food”, Cronbach's α = 0.86) and ‘active engagement in child feeding’ (4 items, e.g., “In my household, my spouse/partner and I frequently discuss how we manage feeding tasks”, Cronbach's α = 0.89). Response options ranged from 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly agree”. Mean scores for both subscales were calculated by averaging items with higher scores indicating better feeding co-parenting. Additionally, all nine items were summed, and due to the relatively high average score (mean = 34.2 out of a possible range of 9-45), tertiles were used to create a dichotomous co-feeding category which was used as moderator in multigroup analysis, with parents scoring in the lowest tertile of co-feeding representing the low co-feeding group.

2.2.3. Structure-related food and snack parenting

Three subscales from the Feeding Practices and Structure Questionnaire (FPSQ) [21] were used to assess structure-related feeding practices during mealtimes: Structured Meal Timing (3 items, e.g., “I decide the time when my child eats his/her meals”, Cronbach's α = 0.61), Structured Meal Setting (3 items, e.g., “I insist my child eats meals at the table”, Cronbach's α = 0.75) and Family Meal Setting (1 item, e.g., “My child eats the same meals as the rest of the family”). Response options ranged from 1 = “Never” to 5 = “Always”. Mean scores were calculated by averaging items, where higher scores indicated more structure provided during mealtimes. A latent variable was created that included all three subscales to reflect parental structure-related food parenting. Two subscales were selected from the Parenting around SNAcking Questionnaire (P-SNAQ) [65] to assess structure-related snack parenting practices: Snack planning and routines (3 items, e.g., “I give my child snacks at about the same time each day”, Cronbach's α = 0.78), and Snack rules and limits (4 items, e.g., “I tell my child when she can have a snack”, Cronbach's α = 0.86). Response options ranged from 1 = “Really not like me”, 2 = “Sort of not like me”, 3 = “Sort of like me”, to 4 = “Really like me”. A latent variable was created that included both subscales to reflect parental structure-related snack parenting.

2.2.4. Child eating behaviors

Two subscales from the Child Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (CEBQ) [66] were used to assess children's food approach eating behaviors. These included Food Responsiveness (4 items, e.g., “If allowed to, my child would eat too much”, α = 0.80) and Emotional Overeating (4 items, e.g., “My child eats more when worried”, α = 0.87). Although one item was omitted from the original Food Responsiveness scale due to clerical error (“If given the chance, my child would always have food in his/her mouth”), we decided to use our four-item version based on the good internal reliability. Response options ranged from 1 = “Never” to 5 = “Always”. Mean scores were calculated by averaging items with higher scores indicating more child food approach eating behaviors. Two latent variables were used to examine structural paths in multigroup analysis.

2.3. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among study variables, as well as group comparisons across parent sex (Table 1 ) and co-feeding levels (Supplemental Table 1), were examined using SPSS 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York). For Aim 1, we used analyses of variance (ANOVA) to test sex differences across continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. Significance was considered at p-value < 0.05. For Aims 2 and 3, path analysis, including multigroup analysis, were conducted in Mplus v.6.12 using maximum likelihood estimation [67]. Structure-related food and snack parenting practices, as well as the child eating behaviors Food Responsiveness (FR) and Emotional Overeating (EOE), were entered as latent variables. Correlations amongst the parenting practices and child eating behaviors respectively were added. For Aim 2 we tested our model presented in Fig. 1 using the whole study sample. Paths between structure-related food and snack parenting and child eating behavior outcomes were examined simultaneously. Model fit was assessed using the chi-square statistic, the Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), interpreted using recommendations of Hu and Bentler [68] (RMSEA value < 0.08, TLI and CFI value > 0.95). For Aim 3, multigroup analyses were conducted to test differences in relationships between structure-related food and snack parenting and child eating behavior across parent sex. To this end, the model was estimated separately for mothers and fathers. We examined unconstrained (paths are freely estimated) and constrained models (all paths are fixed to be equal for mothers and fathers). Using the combined fit indices, these nested models were compared utilizing the chi-square difference test (Δχ2). A p-value greater or equal to 0.05 indicated that the model fit did not worsen when constraining path estimates to be equal across groups and therefore there is no moderation due to these groups. This procedure was repeated using co-feeding groups as a moderator, instead of parental sex.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics and key study variables stratified by parent sex.

| Mothers (n=206) | Fathers (n=112) | |||||

| Mean or N | SD or % | Mean or N | SD or % | p-value | ||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Parent age | 37.32 | 7.04 | 38.39 | 5.62 | 0.166 | |

| Child age | 6.80 | 3.23 | 6.41 | 2.94 | 0.290 | |

| Child sex | Female Male Prefer not to say |

100 105 1 |

48.5 51.0 0.5 |

53 58 1 |

47.3 51.8 0.9 |

0.894 |

| Total children in household (current) | 2.21 | 1.19 | 1.99 | 0.87 | 0.088 | |

| Relationship status | Single Partnered/married Divorced/separated |

15 178 13 |

7.3 86.4 6.3 |

4 102 6 |

3.6 91.1 5.4 |

0.375 |

| Race | Black/African American Indian American/Native Alaskan Native Hawaiian/ Pacific Islander Asian Hispanic/Latin White Other More than one race |

15 2 0 17 6 156 1 9 |

7.3 1.0 0 8.3 2.9 75.7 0.5 4.4 |

3 3 0 6 4 90 2 4 |

2.7 2.7 0 5.4 3.6 80.4 1.8 3.6 |

0.358 |

| Employment | Student Self-employment Part-time Full-time Homemaker/full-time parent Unemployed Retired |

3 12 33 98 50 10 0 |

1.5 5.8 16.0 47.6 24.3 4.9 0 |

1 1 2 106 0 1 1 |

0.9 0.9 1.8 94.6 0 0.9 0.9 |

<0.001 |

| Essential worker | Yes No |

52 154 |

25.2 74.8 |

48 64 |

42.9 57.1 |

0.001 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||

| Education | No or partial college 4-year college Graduate degree |

90 80 36 |

43.7 38.8 17.5 |

27 45 40 |

24.1 40.2 35.7 |

<0.001 |

| 2019 household income | <$50,000 $50,000+ |

60 141 |

29.9 70.1 |

14 98 |

12.5 87.5 |

0.001 |

| Food insecurity (current) | Insecure Secure | 55 148 |

27.1 72.9 |

21 90 |

18.9 81.1 |

0.106 |

| Receipt of public assistance (current) | Yes No |

53 153 |

25.7 74.3 |

9 101 |

8.2 91.8 |

<0.001 |

| Socioeconomic disadvantage index | 1.25 | 1.23 | 0.63 | 0.75 | <0.001 | |

| Anthropometrics | ||||||

| Parent BMI | 27.93 | 6.62 | 28.08 | 5.12 | 0.843 | |

| Child BMIz (CDC) | 0.57 | 1.78 | 0.53 | 1.59 | 0.837 | |

| Child BMI percentile (CDC) | 63.29 | 35.36 | 61.08 | 34.40 | 0.604 | |

| Stress & mental health* | Possible range | |||||

| Stress rating (pre-COVID) | 0-10 | 4.10 | 2.23 | 3.61 | 2.27 | 0.064 |

| Stress rating (current) | 0-10 | 5.22 | 2.65 | 4.52 | 2.71 | 0.025 |

| COVID-19 related stress | 1-5 | 2.82 | 0.85 | 2.47 | 0.94 | 0.001 |

| Parenting stress | 1-5 | 2.57 | 0.64 | 2.37 | 0.70 | 0.011 |

| Poor mental health | 4-16 | 8.31 | 3.48 | 6.91 | 3.00 | <0.001 |

| Food parenting & co-feeding | Possible range | |||||

| Snack planning and routines | 1-5 | 2.15 | 0.88 | 2.27 | 0.81 | 0.255 |

| Snack rules and limits | 1-5 | 2.72 | 0.91 | 2.80 | 0.73 | 0.418 |

| Structured meal setting | 1-5 | 3.79 | 0.95 | 3.85 | 0.86 | 0.620 |

| Structured meal timing | 1-5 | 3.34 | 0.84 | 3.45 | 0.78 | 0.275 |

| Family meal setting | 1-5 | 3.85 | 0.97 | 3.71 | 1.03 | 0.217 |

| Shared positive views and values in child feeding | 1-5 | 3.76 | 0.84 | 4.05 | 0.65 | 0.002 |

| Active engagement in child feeding | 1-5 | 3.34 | 0.96 | 3.81 | 0.80 | <0.001 |

| Child eating behaviors | Possible range | |||||

| Food responsiveness | 1-5 | 2.72 | 0.88 | 2.58 | 0.86 | 0.190 |

| Emotional overeating | 1-5 | 2.10 | 0.84 | 2.21 | 0.91 | 0.306 |

* Correlations between the socioeconomic disadvantage index and the stress and poor mental health (anxiety, depression, loneliness, hopelessness) variables are presented in Supplemental Table 2.

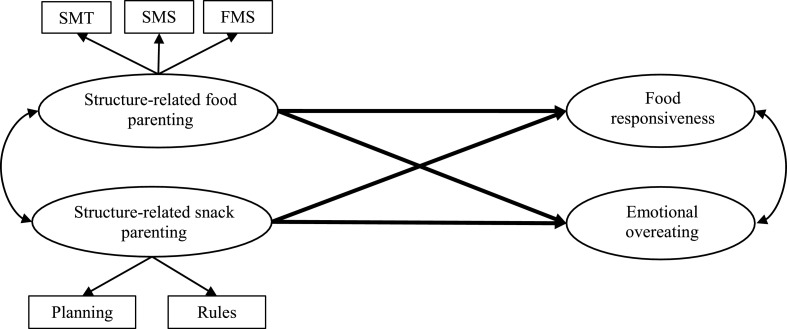

Fig. 1.

Conceptual path model highlighting the proposed regression paths between structure-related food and snack parenting and child food approach eating behaviors. Separate multigroup analyses were conducted for the two moderators, parent sex (mothers vs fathers) and co-feeding level (low vs. high).

Abbreviations: Planning = Snack planning and routines, Rules = Snack rules and limits, both subscales were assessed with the Parenting around SNAcking Questionnaire (P-SNAQ) [65]; SMT = Structured Meal Timing, SMS = Structured Meal Setting, FMS = Family Meal Setting, all 3 subscales were assessed with the Feeding Practices and Structure Questionnaire (FPSQ) [21].

3. Results

3.1. Parent sex differences

Participant characteristics, stratified by parent sex, are presented in Table 1. Few differences were seen for parent and child demographics, and none for anthropometrics. Mothers were more socioeconomically disadvantaged relative to fathers within the sample. That is, mothers were more likely to be unemployed, working part-time or a homemaker/full-time parent; more mothers had a lower education level than fathers; mothers had a lower household income and were currently more likely to receive public assistance although there was no difference in current reported food insecurity. Fathers were more likely to be an essential worker. Sex differences were also seen on all stress and mental health variables with higher scores for mothers than fathers, except the general pre-COVID stress rating. Controlling for these differences in stress, mental health issues, or SES disadvantage did not substantially impact most of the sex-related differences in parent characteristics. However, ratings of general stress during COVID were no longer different between mothers and fathers once we adjusted for SES disadvantage (Estimated marginal means: mothers = 5.14 vs. fathers = 4.66; p = 0.134).

Differences were found in the two co-feeding perceptions. Here fathers had higher scores compared to mothers, indicating that fathers considered their feeding behaviors as more cooperative and aligned with their partner. Interestingly, no parent sex differences were seen in their structure-related food and snack parenting practices or child eating behaviors.

In response to the pandemic, 70 mothers (34%) and 52 fathers (46%) indicated that they or their spouse/partner had to change their work schedule to care for their children themselves (32 [16%] and 85 [41%] of mothers said their childcare was not affected or they did not have a child in childcare compared to 19 [17%] and 29 [26%] of fathers respectively). Before the pandemic, 20 (10%) mothers and 8 (7%) fathers ate meals together with all or most of their family members for 3 or more times per day. During the pandemic this increased to 28 (14%) mothers and 18 (16%) fathers.

3.2. Relationships of structure-related food and snack parenting with child eating behaviors

Fit indices for the model presented in Fig. 1 and tested for the whole sample were good (see Table 2 ). Structure-related food parenting practices were significantly negatively associated with emotional overeating but not food responsiveness (β = -0.221, p = 0.061). On the other hand, structure-related snack parenting practices were positively associated with both child eating behaviors, with a stronger association seen for emotional overeating.

Table 2.

Model fit indices and structural path estimates for the whole sample (n=318), by parent sex and co-feeding level.

| Model | Groups | χ2 | Df | p-value | RMSEA | 95% CI | p-value | CFI | TLI | Food parenting → FR | Food parenting → EOE | Snack parenting → FR | Snack parenting → EOE |

| Whole sample | 128.46 | 59 | <.001 | .061 | .046-.075 | .103 | .960 | .947 | -.221 (.061) | -.494 (<.001) | .240 (.040) | .354 (.003) | |

| By sex (unconstraint) |

Mothers (n=206) | 229.75 | 136 | <.001 | .066 | .051-.080 | .042 | .947 | .940 | -.211 (.217) | -.536 (.003) | .340 (.044) | .398 (.024) |

| Fathers (n=112) | -.227 (.132) | -.434 (.004) | -.011 (.942) | .262 (.109) | |||||||||

| Constraint model | 235.41 | 140 | <.001 | .065 | .051-.080 | .044 | .946 | .940 | |||||

| Model comparison | Chi-square difference test | ∆ =6 |

∆ =4 |

∆ =.226 |

|||||||||

| By co-feeding (unconstraint) |

Low (n=86) | 214.32 | 136 | <.001 | .064 | .047-.081 | .080 | .96 | .938 | .138 (.564) | -.516 (.040) | -.007 (.978) | .311 (.226) |

| High (n=194) | -.334 (.014) | -.481 (<.001) | .246 (.068) | .323 (.015) | |||||||||

| Constraint model | 218.86 | 140 | <.001 | .063 | .047-.079 | .090 | .946 | .939 | |||||

| Model comparison | Chi-square difference test | ∆ =5 |

∆ =4 |

∆ =.338 |

|||||||||

Abbreviations: χ2 = Chi-square, Df = degrees of freedom, RMSEA = Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation, CFI = Comparative Fit Index, TLI = Tucker Lewis Index, FR = food responsiveness, EOE = emotional overeating

3.3. Multigroup models – moderation by parent sex and co-feeding level

Paths for models conducted separately for mothers and fathers are presented in Table 2. For both mothers and fathers, structure-related food parenting practices were negatively associated with emotional overeating but not food responsiveness. For mothers only, structure-related snack parenting practices were positively associated with both child eating behaviors, while for fathers neither of the relationships was significant. However, the chi-square difference test was not significant (p = 0.226) and moderation by parent sex is thus not statistically apparent.

Paths for models conducted separately for low and high co-feeding groups are presented in Table 2. For the low co-feeding group, structure-related food parenting practices were negatively associated with emotional overeating but not food responsiveness. For the high co-feeding group, structure-related food parenting practices were negatively associated with both child eating behaviors. While structure-related snack parenting practices were positively associated with emotional overeating in the high co-feeding group, there were no associations with either child eating behavior in the low co-feeding group. Again, the chi-square difference test was not significant (p = 0.338) and moderation by co-feeding level is thus not statistically apparent.

4. Discussion

The context of the pandemic provided a unique opportunity to examine food and snack parenting among fathers and mothers, how couples negotiate feeding, and how the provision of structure in the meal environment is implemented and related to child eating behaviors.

4.1. Parent sex differences

Mothers and fathers participating in our study were drawn from different families, with each survey corresponding to a unique parent-child dyad. This means we cannot rule out the possibility that unmeasured between-family differences drove any observed differences in variables of interest by parent sex. Nevertheless, as a preliminary step, and following the methods of other studies [69], we tested for differences by parent sex in co-feeding, structure-related food and snack parenting practices, and perception of child eating behaviors, as well as in parental stress/mental health, demographic, socioeconomic and anthropometric characteristics. We found differences between mothers and fathers in stress and mental health measures, with mothers indicating experiencing more stress and mental health issues during the early months of the pandemic than fathers. This is in line with previous findings, which show increases in stress and mental health issues such as depression and anxiety during the pandemic [30,70], especially among mothers compared to fathers [71]. There are two possible explanations. One, mothers have taken on more of the additional childcare responsibilities resulting from school and childcare closures [72]. Many have been home-schooling while also working, either from home or out of the house [71], thus experiencing greater strain due to the pandemic while missing many of the usual support systems. Alternatively, these results may be driven by reporting bias in relation to mental health issues, since men are less likely to report on these issues and/or seek help [73], [74], [75]. Mothers and fathers in our sample also differed on socioeconomic indicators, with mothers reporting greater disadvantage, including lower household income, lower education level, and a higher percentage receiving public assistance, and almost double as many fathers in full-time employment (94.6%) as compared to mothers (47.6%).

Interestingly, differences by parent sex were seen on the two co-feeding subscales, while no differences were found on the structure-related food and snack parenting practices or any other child variable, including eating behaviors, weight or age. Fathers had higher scores on ‘shared positive views and values in child feeding’ and ‘active engagement in child feeding’, indicating that they perceived the feeding tasks as more equally shared with their spouse/partner, compared to mothers who were more likely to see themselves as primary caregiver and responsible for feeding tasks. This is partially in line with findings by Tan et al. [50] who found that fathers reported higher scores on the total Feeding Coparenting Scale and the Active Engagement subscale. However, the score for the Shared Views subscale did not differ in their sample of 178 mothers and 129 fathers of 3-5-year-old children. As the authors outlined, variable perceptions of responsibilities around feeding complicate assessment of the co-feeding construct, and varying expectations for active engagement between mothers and fathers might also lead to the differences observed. Although not specific to the feeding context, Douglas and colleagues [53] also found that fathers scored higher than mothers on coparenting quality when examined in cohabiting parents. This suggests that fathers may in general rate the cooperation with their spouse as more positive than mothers.

Structure-related food and snack-parenting practices did not differ by parent sex. In a previous study using the Feeding Practices and Structure Questionnaire, Searle and colleagues [25] found that in mother-father pairs of preschoolers, there was no difference in Structured Meal Setting or Family Meal Setting. Structured Meal Timing was significantly higher in mothers compared to fathers [25] although this difference might not be clinically significant. In both the current study and Searle's, the difference in Structured Meal Timing was 0.1 on a 5-point scale. Douglas and colleagues [53] did not provide statistical testing but reported that mothers had higher scores on ‘providing a healthy home environment’ and ‘modeling healthy eating behaviors’, while fathers had higher scores on ‘allowing the child to control his/her food intake’ (unstructured practice) and ‘monitoring unhealthy foods’. Similarities of mothers and fathers in the relatively high level of structure provided in the current sample might be due to changed feeding responsibilities during the pandemic where both parents might be around for feeding occasions more and thus both have more opportunities to implement rules, routines, and limits throughout the day. Indeed, a posteriori analyses in the current sample found that 35.4% of mothers and 32.1% of fathers indicated that compared to before the COVID-19 crisis, they were now more often eating meals together as a family.

Few previous studies have reported on sex differences in parent-reported child eating behaviors. Similar to our null finding, Vollmer [69] reported no differences between mothers (n=127) and fathers (n=112) of children aged 3–10 years in emotional overeating (mothers = 1.5, fathers = 1.6) or food responsiveness (mothers = 2.1, fathers = 2.2), among other eating behaviors. Notably, the means presented in the current study and collected during the pandemic were higher for emotional overeating and food responsiveness by about 0.6 points, compared to previously reported means by Vollmer [69].

4.2. Child age differences

Given the large age range of children in our study, we additionally wanted to verify if food parenting practices, co-feeding or child eating behaviors differed across pre-school aged and school aged children. As reported in our previous paper [57], age differences were seen in all but one structure-related parenting practice (i.e., Family Meal Setting). For all, structure was higher in parents of pre-school aged compared to school aged children. Active engagement in child feeding was significantly higher in parents of preschool aged children, compared to school aged children (3.64 vs. 3.39, p=0.015), while no difference was seen in shared positive views and values in child feeding (3.93 vs. 3.80, p=0.159). No age differences were seen either for the child eating behaviors Food Responsiveness (2.65 vs. 2.69, p=0.695) or Emotional Overeating (2.12 vs. 2.16, p=0.690). Based on these findings it is warranted to examine differences in relationships between structure-related food and snack parenting practices and child eating behaviors across child developmental stages. To this end, longitudinal studies are needed with multiple assessments of these parent practices and child behaviors at varying child ages.

4.3. Relationships between structure-related food and snack parenting and child eating behaviors

This is the first study to simultaneously examine relationships between structure-related food and snack parenting and child food approach eating behaviors. In the overall sample, we found that the snack parenting practices (including implementation of snack planning and routines as well as having snack rules and limits) were positively associated with emotional overeating and food responsiveness. This is somewhat contradictory to our expectations and to the finding that structure-related food parenting practices were negatively associated with emotional overeating. We hypothesize that the expression of food responsiveness and emotional overeating is probably more likely to occur or is more noticeable to parents during snack time rather than a meal; thus, ratings of food approach may be disproportionately driven by parents’ perceptions of their children's behavior around snacks, producing the relationship we observed between food approach and snack parenting practices. While this unexpected finding warrants further investigation, it is notable that, in a posteriori analyses of the current sample, both eating behaviors were positively correlated with children's intake of snacks, except fruits and vegetables (data not shown). Snack items included chocolate/candy, cookies/cake/pie, donuts/danish/muffin, ice cream, regular and low-fat chips or savory snacks. Emotional overeating was also positively correlated with fast food intake. Given the cross-sectional nature of the data in the current study, it is also likely that higher food approach by the child leads to parents implementing more structure-related snack parenting practices (i.e., more routines and rules) in order to manage intake of high energy-dense snack items, especially during pandemic times where parents might now be more often responsible for providing snacks than during times when their children are attending school or childcare (while less might have changed for breakfast and dinner times).

Along the same lines, we saw that both types of parenting practices were more likely associated with emotional overeating (structure-related snack parenting practices positively, structure-related food parenting practices negatively) than food responsiveness (no relationship with structure-related food parenting practices). One reason could be differences in heritability of the two appetitive characteristics. Emotional overeating is more environmentally driven [76,77], while food responsiveness is more heritable [78] and potentially less influenced by parental practices. Additionally, structure provided around eating occasions may be more important for children's emotional eating. For example, family meals have been shown to be beneficial for children's mental health/self-regulation [79], [80], [81], and may help children manage or regulate their emotions, reducing the likelihood of emotional eating. In contrast, food restriction/exposure, rather than structure of the meal environment, might be more relevant in influencing children's responsiveness to food cues.

While some differences in the significance and strength of paths were seen in analyses split by parent sex and co-feeding, multigroup analysis were not significant and therefore we did not find strong evidence that either parent characteristic moderated the relationships between structure-related feeding practices and child food approach. In contrast, we observed similar directions of effects for mothers and fathers, suggesting that fathers may exert similar influences compared to mothers on children's eating and therefore arguing that they should not be excluded from research on parent feeding. However, several potential reasons why moderation was not observed in the current study should also be noted. First, the sample size might have been too small to detect effects. The smaller sample size highlights challenges with recruitment of fathers in such research, which we have reported in a previous publication [82]. Second, measures of co-feeding used in the current study may not be sensitive enough to distinguish a true high vs. low co-feeding group. As noted above, the sample mean was high which suggests that most parents reported high levels of co-feeding. Although to address this issue we compared the lowest co-feeding tertile to the remaining parents, no moderation was detected. Issues with self-report on the co-feeding construct and differences in expectations by partners have been reported by other authors [50]. It is unclear how parent report would compare to objective measures of co-feeding. Additionally, reports of only one family member were assessed here so no information is available to determine how the partner would rate the couple's level of co-feeding and thus what the level of agreement between both partners is. Also, fathers reported better co-feeding (i.e., higher mean scores) than the mothers in this sample and while they were not part of the same family, this could indicate that parents potentially vary in quantity and/or quality of co-feeding. With expanded assessment of the co-feeding construct, future studies will be able to determine if consistency and cooperation between parents impact how they work together to feed their children and facilitate the implementation of structure, especially in meals. Douglas and colleagues have previously highlighted that in order to implement structure around meals (e.g., regular meal routine), an organized environment and a shared or supportive feeding approach by both parents is necessary, while this is not the case for the more individualistic coercive food parenting practices such as pressuring a child to eat or using food as reward [53].

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted stress and mental health, especially for parents [29,30]. Parenting stress [83], maternal psychological distress [84,85], economic/financial stress, and food insecurity [86] have been shown to impact parental food parenting practices [87]. Overall, parents experiencing higher levels of stress may be more likely to use coercive practices [88]. However, stress may also be associated with more positive food parenting practices encompassing structure and autonomy support or promotion. We previously reported findings in this sample that higher COVID-19-specific stress was associated with more positive interactions (e.g. engaging with child around mealtimes) and providing structure around snacks (e.g. having snack rules, limits and routines) [57]. Given the positive association seen between a) COVID-19-specific stress and structure-related snack parenting practices, and b) structure-related snack parenting practices and food approach eating behaviors, it is conceivable that structure around snacks might mediate the relationship between COVID-19-specific stress and child food approach. Thus, testing more complex or expanded path models with large sample sizes in all groups seems warranted to further our understanding about likely mechanisms. For example, such models could test simultaneous relationships between COVID-19-specific stress, structure-related parenting practices (snack and food), other types of food parenting practices (e.g., coercive control), child eating behaviors, and dietary intake.

4.4. Limitations and considerations for interpretation

Limitations of our study should be acknowledged and considered when interpreting our findings. First, using parental self-report may be subject to recollection, selection, and single informant (i.e., perspective of only one caregiver) bias, although these biases are likely to be somewhat equivalent between mothers and fathers and thus unlikely to substantively alter our findings. Second, given the online format of data collection, ‘having internet access’ was indirectly an eligibility criteria and verification of data was not feasible. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic this was the safest option to collect data, and internet use is extremely common in the US, lessening some concerns about consequences for generalizability. Third, due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, it is unknown if reported appetitive traits/characteristics and living conditions had changed at the time of data collection compared to pre-pandemic circumstances. Therefore, the impact of changes in these factors and directionality of associations could not be determined. Fourth, recruitment through MTurk resulted in our sample being more heavily weighted toward individuals with less socioeconomic disadvantage and higher levels of education, as well as being predominantly white. Caution in generalizing these results to families with other racial/ethnic or socioeconomic backgrounds is warranted. Fifth, children of parents included in the current sample reflect a large age range (2-12 years) which can lead to differences in parent food parenting practices. We have discussed the existing differences above, and the wider age range could be considered to increase the applicability of our findings to more families, rather than being constrained to families with children in a narrow developmental stage. Finally, data were collected in an unbalanced sample of mothers and fathers drawn from different families. The aim of the overall study was to enroll adults and as such we did not recruit mother-father dyads. Comparing responses from mothers and fathers within the same family would ensure an equal number of mothers and fathers, and also shed light on differences in perceptions of co-parenting practices and roles between the sexes with the same reference point, with control for potential confounding factors that could create differences between families, and is therefore warranted for future research.

5. Conclusions

Despite the disruptions endured during the COVID-19 pandemic, parents were largely able to provide structure within the meal environment and this appears to be associated with children's food approach eating behaviors. Structure-related food parenting practices were related to lower levels of obesity-associated eating behaviors in children (especially emotional overeating), which could contribute to healthier profiles of food intake and body weight. This finding was apparent for mothers as well as fathers. However, there seem to be differential pathways for structure-related practices specifically focused on snacks and a distinction with the ‘regular’ structure-related food parenting practices such that higher levels of structure around snacks was associated with greater food approach. The direction of association is not clear in this cross-sectional study but the possibility that structured snacking might increase food responsivity within the pandemic warrants further investigation. Although non-significant, we noted small variations in the relationships between structure-related food and snack parenting practices and child eating behaviors based on parental co-feeding levels. Examining not only how mothers and fathers uniquely interact with their children around eating but also how they cooperate and work as a team (or not) will be essential in the future and might provide opportunities to draw on all resources within the family when facing the next pandemic or stressful life event.

Authors' contributions

EJ, KS, GT, AA and SC conceptualized the study. EJ, KS, GT, JS, AA and SC collected the data. EJ conducted all analyses and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed conceptually, reviewed, critiqued and approved this manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by Dalio Philanthropies, with additional support from the NIH [grant numbers R01DK113286, R01DK117623 and UG3OD023313]. The funding sources had no involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Declaration of Competing interests

None.

Acknowledgements

We thank all families for participating in our study, especially during the early stages of the pandemic.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2022.113837.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Aymerich-Franch L. COVID-19 lockdown: impact on psychological well-being and relationship to habit and routine modifications. PsyArXiv. 2020 https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/9vm7r. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flesia L., Monaro M., Mazza C., Fietta V., Colicino E., Segatto B., Roma P. Predicting perceived stress related to the Covid-19 outbreak through stable psychological traits and machine learning models. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9:3350. doi: 10.3390/jcm9103350. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9103350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fegert J.M., Vitiello B., Plener P.L., Clemens V. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health. 2020;14:20. doi: 10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkins J.L. Challenges and Opportunities Created by the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020;52:669–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2020.05.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll N., Sadowski A., Laila A., Hruska V., Nixon M., Ma D.W.L., Haines J. On Behalf Of The Guelph Family Health Study, The Impact of COVID-19 on Health Behavior, Stress, Financial and Food Security among Middle to High Income Canadian Families with Young Children. Nutrients. 2020;12:2352. doi: 10.3390/nu12082352. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiefner-Burmeister A.E., Hoffmann D.A., Meers M.R., Koball A.M., Musher-Eizenman D.R. Food consumption by young children: A function of parental feeding goals and practices. Appetite. 2014;74:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.11.011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orrell-Valente J.K., Hill L.G., Brechwald W.A., Dodge K.A., Pettit G.S., Bates J.E. Just three more bites”: An observational analysis of parents’ socialization of children's eating at mealtime. Appetite. 2007;48:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.06.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Strien T., van Niekerk R., Ouwens M.A. Perceived parental food controlling practices are related to obesogenic or leptogenic child life style behaviors. Appetite. 2009;53:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.05.011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farrow C.V., Blissett J. Controlling Feeding Practices: Cause or Consequence of Early Child Weight? Pediatrics. 2008;121 doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3437. e164 LP-e169https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodgers R.F., Paxton S.J., Massey R., Campbell K.J., Wertheim E.H., Skouteris H., Gibbons K. Maternal feeding practices predict weight gain and obesogenic eating behaviors in young children: a prospective study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013:10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-24. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ventura A.K., Birch L.L. Does parenting affect children's eating and weight status? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Philippe K., Chabanet C., Issanchou S., Monnery-Patris S. Child eating behaviors, parental feeding practices and food shopping motivations during the COVID-19 lockdown in France: (How) did they change? Appetite. 2021;161 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniels L.A., Mallan K.M., Nicholson J.M. Outcomes of an early feeding practices intervention to prevent childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e109–e118. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2882. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniels L.A., Mallan K.M., Jansen E., Nicholson J.M., Magarey A.M., Thorpe K. Comparison of Early Feeding Practices in Mother-Father Dyads and Possible Generalization of an Efficacious Maternal Intervention to Fathers’ Feeding Practices: A Secondary Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:6075. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176075. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-2882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams E.L., Caccavale L.J., Smith D., Bean M.K. Longitudinal patterns of food insecurity, the home food environment, and parent feeding practices during COVID-19. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2021;7:415–424. doi: 10.1002/osp4.499. https://doi.org/10.1002/osp4.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balantekin K.N., Anzman-Frasca S., Francis L.A., Ventura A.K., Fisher J.O., Johnson S.L. Positive parenting approaches and their association with child eating and weight: A narrative review from infancy to adolescence. Pediatr. Obes. 2020;15:e12722. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12722. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pratt M., Hoffmann D., Taylor M., Musher-Eizenman D. Structure, coercive control, and autonomy promotion: A comparison of fathers’ and mothers’ food parenting strategies. J. Health Psychol. 2017;24:1863–1877. doi: 10.1177/1359105317707257. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317707257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rollins B.Y., Savage J.S., Fisher J.O., Birch L.L. Alternatives to restrictive feeding practices to promote self-regulation in childhood: a developmental perspective. Pediatr. Obes. 2016;11:326–332. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12071. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Black M.M., Aboud F.E. Responsive feeding is embedded in a theoretical framework of responsive parenting. J. Nutr. 2011;141:490–494. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.129973. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.110.129973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jansen E., Mallan K.M., Nicholson J.M., Daniels L.A. The feeding practices and structure questionnaire : construction and initial validation in a sample of Australian first-time mothers and their 2-year olds. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014:11. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-72. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-11-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jansen E., Williams K.E., Mallan K.M., Nicholson J.M., Daniels L.A. The Feeding Practices and Structure Questionnaire (FPSQ-28): A parsimonious version validated for longitudinal use from 2 to 5 years. Appetite. 2016;100:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frankel L.A., Powell E., Jansen E. The Relationship between Structure-Related Food Parenting Practices and Children's Heightened Levels of Self-Regulation in Eating. Child. Obes. 2018;14:81–88. doi: 10.1089/chi.2017.0164. https://doi.org/10.1089/chi.2017.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finnane J.M., Jansen E., Mallan K.M., Daniels L.A. Mealtime Structure and Responsive Feeding Practices Are Associated With Less Food Fussiness and More Food Enjoyment in Children. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017;49 doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2016.08.007. 11-18e1https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powell F., Farrow C., Meyer C., Haycraft E. The importance of mealtime structure for reducing child food fussiness. Matern. \& Child Nutr. 2017;13:e12296. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12296. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Searle B.-R.E., Harris H.A., Thorpe K., Jansen E. What children bring to the table: The association of temperament and child fussy eating with maternal and paternal mealtime structure. Appetite. 2020;151 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruggiero C.F., Hohman E.E., Birch L.L., Paul I.M., Savage J.S. INSIGHT responsive parenting intervention effects on child appetite and maternal feeding practices through age 3 years. Appetite. 2021;159 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.105060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.105060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cluver L., Lachman J.M., Sherr L., Wessels I., Krug E., Rakotomalala S., Blight S., Hillis S., Bachman G., Green O., Butchart A., Tomlinson M., Ward C.L., Doubt J., McDonald K. Parenting in a time of COVID-19. Lancet (London, England) 2020;395:e64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30736-4. e64https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30736-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.UNICEF, Coronavirus (COVID-19) parenting tips: Expert tips to help you deal with COVID-19 parenting challenges., (2020). https://www.unicef.org/coronavirus/covid-19-parent (accessed July 13, 2021).

- 29.Gloster A.T., Lamnisos D., Lubenko J., Presti G., Squatrito V., Constantinou M., Nicolaou C., Papacostas S., Aydın G., Chong Y.Y., Chien W.T., Cheng H.Y., Ruiz F.J., Garcia-Martin M.B., Obando-Posada D.P., Segura-Vargas M.A., Vasiliou V.S., McHugh L., Höfer S., Baban A., Dias Neto D., da Silva A., Monestès J.-L., Alvarez-Galvez J., Paez-Blarrina M., Montesinos F., Valdivia-Salas S., Ori D., Kleszcz B., Lappalainen R., Ivanović I., Gosar D., Dionne F., Merwin R.M., Kassianos A.P., Karekla M. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health: An international study. PLoS One. 2021;15:1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244809. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nochaiwong S., Ruengorn C., Thavorn K., Hutton B., Awiphan R., Phosuya C., Ruanta Y., Wongpakaran N., Wongpakaran T. Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:10173. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89700-8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89700-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nearchou F., Flinn C., Niland R., Subramaniam S.S., Hennessy E. Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health Outcomes in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:8479. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu J.J., Bao Y., Huang X., Shi J., Lu L. Mental health considerations for children quarantined because of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc. Heal. 2020;4:347–349. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30096-1. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30096-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang G., Zhang Y., Zhao J., Zhang J., Jiang F. Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet. 2020;395:945–947. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30547-X. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30547-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minello A. The pandemic and the female academic. Nature. 2020;17:2020. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alon T.M., Doepke M., Olmstead-Rumsey J., Tertilt M. The impact of COVID-19 on gender equality. NBER Working Papers 26947. National Bureau of economic research. 2020 https://doi.org/10.3386/w26947. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Giorgio E., Di Riso D., Mioni G., Cellini N. The interplay between mothers’ and children behavioral and psychological factors during COVID-19: an Italian study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01631-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01631-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerr M.L., Fanning K.A., Huynh T., Botto I., Kim C.N. Parents’ Self-Reported Psychological Impacts of COVID-19: Associations With Parental Burnout, Child Behavior, and Income. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2021;46:1162–1171. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsab089. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsab089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marchetti D., Fontanesi L., Mazza C., Di Giandomenico S., Roma P., Verrocchio M.C. Parenting-Related Exhaustion During the Italian COVID-19 Lockdown. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2020;45:1114–1123. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa093. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petts R.J., Carlson D.L., Pepin J.R. A gendered pandemic: Childcare, homeschooling, and parents’ employment during COVID-19, Gender. Work Organ. 2021;28:515–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12614. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hendy H.M., Williams K.E., Camise T.S., Eckman N., Hedemann A. The Parent Mealtime Action Scale (PMAS). Development and association with children's diet and weight. Appetite. 2009;52:328–339. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.11.003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davison K.K., Gicevic S., Aftosmes-Tobio A., Ganter C., Simon C.L., Newlan S., Manganello J.A. Fathers’ Representation in Observational Studies on Parenting and Childhood Obesity: A Systematic Review and Content Analysis. Am. J. Public Health. 2016;106:e14–e21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303391. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davison K.K., Kitos N., Aftosmes-Tobio A., Ash T., Agaronov A., Sepulveda M., Haines J. The forgotten parent: Fathers’ representation in family interventions to prevent childhood obesity. Prev. Med. (Baltim). 2018;111:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.02.029. https://doi.org/doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cameron E.E., Joyce K.M., Rollins K., Roos L.E. Paternal Depression & Anxiety During the COVID-19 Pandemic. PsyArXiv. 2020 https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/drs9u. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Westrupp E., Bennett C., Berkowitz T.S., Youssef G.J., Toumbourou J., Tucker R., Andrews F., Evans S., Teague S., Karantzas G., Melvin G.A., Olsson C., Macdonald J.A., Greenwood C., Mikocka-Walus A., Hutchinson D., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M., Stokes M.A., Olive L., Wood A., McGillivray J., Sciberras E. Child, parent, and family mental health and functioning in Australia during COVID-19: Comparison to pre-pandemic data. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2021:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01861-z. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01861-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feinberg M.E. The Internal Structure and Ecological Context of Coparenting: A Framework for Research and Intervention. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2003;3:95–131. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maršanić V.B., Kusmić E. Coparenting within the family system: review of literature. Coll. Antropol. 2013;37(4):1379–1383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khandpur N., Charles J., Davison K.K. Fathers’ Perspectives on Coparenting in the Context of Child Feeding. Child. Obes. 2016;12:455–462. doi: 10.1089/chi.2016.0118. https://doi.org/10.1089/chi.2016.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thullen M., Majee W., Davis A.N. Co-parenting and feeding in early childhood: Reflections of parent dyads on how they manage the developmental stages of feeding over the first three years. Appetite. 2016;105:334–343. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.05.039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walsh A.D., Hesketh K.D., van der Pligt P., Cameron A.J., Crawford D., Campbell K.J. Fathers’ perspectives on the diets and physical activity behaviours of their young children. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179210. e0179210–e0179210https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan C.C., Lumeng J.C., Miller A.L. Development and preliminary validation of a feeding coparenting scale (FCS) Appetite. 2019;139:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.04.020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tan C.C., Domoff S.E., Pesch M.H., Lumeng J.C., Miller A.L. Coparenting in the feeding context: perspectives of fathers and mothers of preschoolers. Eat. Weight Disord. - Stud. Anorexia, Bulim. Obes. 2020;25:1061–1070. doi: 10.1007/s40519-019-00730-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00730-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tan C.C., Herzog N.K., Mhanna A. Associations between supportive and undermining coparenting and controlling feeding practices. Appetite. 2021;165 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Douglas S., Darlington G., Beaton J., Davison K., Haines J. O.B.O. The Guelph Family Health Study, Associations between Coparenting Quality and Food Parenting Practices among Mothers and Fathers in the Guelph Family Health Study. Nutrients. 2021;13:750. doi: 10.3390/nu13030750. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aghababian A.H., Sadler J.R., Jansen E., Thapaliya G., Smith K.R., Carnell S. Binge Watching during COVID-19: Associations with Stress and Body Weight. Nutrients. 2021;13:3418. doi: 10.3390/nu13103418. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith K.R., Jansen E., Thapaliya G., Aghababian A.H., Chen L., Sadler J.R., Carnell S. The influence of COVID-19-related stress on food motivation. Appetite. 2021;163 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sadler J.R., Thapaliya G., Jansen E., Aghababian A.H., Smith K.R., Carnell S. COVID-19 Stress and Food Intake: Protective and Risk Factors for Stress-Related Palatable Food Intake in U.S. Adults. Nutrients. 2021;13:901. doi: 10.3390/nu13030901. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jansen E., Thapaliya G., Aghababian A., Sadler J., Smith K., Carnell S. Parental stress, food parenting practices and child snack intake during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appetite. 2021;161 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carnell S., Benson L., Pryor K., Driggin E. Appetitive traits from infancy to adolescence: Using behavioral and neural measures to investigate obesity risk. Physiol. Behav. 2013;121:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.02.015. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carnell S., Pryor K., Mais L.A., Warkentin S., Benson L., Cheng R. Lunch-time food choices in preschoolers: Relationships between absolute and relative intakes of different food categories, and appetitive characteristics and weight. Physiol. Behav. 2016;162:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.03.028. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuczmarski R.J. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development, National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2002;11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berry J.O., Jones W.H. The Parental Stress Scale: Initial Psychometric Evidence. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 1995;12:463–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407595123009. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Department of Mental Health Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health . 2020. COVID-19 and mental health measurement working group. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/departments/mental-health/research-and-practice/mental-health-and-covid-19 (accessed August 5, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 63.Radloff L.S. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977;1:385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B.W., Löwe B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Davison K.K., Blake C.E., Kachurak A., Lumeng J.C., Coffman D.L., Miller A.L., Hughes S.O., Power T.G., Vaughn A.F., Blaine R.E., Younginer N., Fisher J.O. Development and preliminary validation of the Parenting around SNAcking Questionnaire (P-SNAQ) Appetite. 2018;125:323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.01.035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wardle J., Guthrie C. Development of the children's eating behaviour questionnaire. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2001;42:963–970. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00792. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Muthén B., Muthén L. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2017. Mplus user's guide. eight edition. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hu L., Bentler P. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6:1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vollmer R.L. The relationship between parental food parenting practices & child eating behavior: A comparison of mothers and fathers. Appetite. 2021;162 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.American Psychological Association, Stress in AmericaTM 2020. Stress in the Time of COVID-19, Volume One., (2020). https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2020/report (accessed July 13, 2021).

- 71.Zamarro G., Prados M.J. Gender differences in couples’ division of childcare, work and mental health during COVID-19. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2021;19:11–40. doi: 10.1007/s11150-020-09534-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-020-09534-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xue B., McMunn A. Gender differences in unpaid care work and psychological distress in the UK Covid-19 lockdown. PLoS One. 2021;16:1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247959. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sigmon S.T., Pells J.J., Boulard N.E., Whitcomb-Smith S., Edenfield T.M., Hermann B.A., LaMattina S.M., Schartel J.G., Kubik E. Gender differences in self-reports of depression: The response bias hypothesis revisited. Sex Roles. 2005;53:401–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-6762-3. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mackenzie C.S., Gekoski W.L., Knox V.J. Age, gender, and the underutilization of mental health services: The influence of help-seeking attitudes. Aging Ment. Health. 2006;10:574–582. doi: 10.1080/13607860600641200. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860600641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Möller-Leimkühler A.M. Barriers to help-seeking by men: a review of sociocultural and clinical literature with particular reference to depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2002;71:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00379-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00379-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Herle M., Fildes A., Rijsdijk F., Steinsbekk S., Llewellyn C. The Home Environment Shapes Emotional Eating. Child Dev. 2018;89:1423–1434. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12799. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Herle M., Fildes A., Llewellyn C. Emotional eating is learned not inherited in children, regardless of obesity risk. Pediatr. Obes. 2018;13:628–631. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12428. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Carnell S., Haworth C.M.A., Plomin R., Wardle J. Genetic influence on appetite in children. Int. J. Obes. 2008;32:1468–1473. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.127. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fiese B.H. Routines and Rituals: Opportunities for Participation in Family Health. OTJR Occup. Particip. Heal. 2007;27:41S–49S. https://doi.org/10.1177/15394492070270S106. [Google Scholar]