Abstract

Study Objectives:

Cultural sleep practices and COVID-19 mitigation strategies vary worldwide. The sleep of infants and toddlers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States is understudied.

Methods:

Caregivers of children aged < 3 years responded to a cross-sectional survey during 2020 (divided into quarters, with the year quarter 1 being largely prelockdown). We assessed the global effect of year quarter on parent-reported total sleep time (hours) and sleep onset latency (hours) using an analysis of variance. We used multivariable linear regression to assess the adjusted effect of year quarter on total sleep time, sleep onset latency, and parental frustration. We used logistic regression to assess the adjusted effect of year quarter on nap consistency.

Results:

Of 594 children, the mean age was 18.5 ± 9.7 months; 52% were female. In the adjusted analyses, the reference categories were as follows: quarter 1 (year quarter), ≤ 6 months (age category), and < $25,000 (annual household income). Total sleep time was associated with age category (ages 12 to ≤ 24 months: β = −2.86; P = .0004; ages 24 to ≤ 36 months: β = −3.25; P < .0001) and maternal age (β = –0.04; P = .05). Sleep onset latency was associated with year quarter (year quarter 3: β = 0.16; P = .04), age category (ages 24 to ≤ 36 months: β = 0.28; P < .0001), annual household income ($100,000–$150,000: β = –0.15; P = .03; > $150,000: β = –0.19; P = .01), and lack of room-sharing (β = –0.09; P = .05). Parental frustration with sleep increased with age (all P < .05) and lack of room-sharing (P = .01). The effect of lack of room-sharing on nap consistency approached significance (adjusted odds ratio, 1.88; 95% confidence interval, 0.95–3.72).

Conclusions:

Social factors such as lower household income and room-sharing affected the sleep of U.S. infants and toddlers as opposed to the COVID-19 lockdown itself.

Citation:

Gupta G, O’Brien LM, Dang LT, Shellhaas RA. Sleep of infants and toddlers during 12 months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the midwestern United States. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18(5):1225–1234.

Keywords: pediatric, sleep, COVID-19, infant, toddler, social determinants of health

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: The economic and social burden caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the daytime and nighttime schedules of infants, toddlers, and their families. Little is known about how the sleep of infants and toddlers in the United States was affected during this time or how the sleep characteristics of infants and toddlers compared between the pre-and postlockdown periods of 2020.

Study Impact: This study highlights how the sleep of U.S. infants and toddlers who are from families with a lower household income and who do not have their own room was differentially impacted during the COVID-19 pandemic. A prelockdown status did not have a protective effect on sleep; rather, social determinants of health had the most significant impact.

INTRODUCTION

The daytime and sleep routines of infants, toddlers, and their parents were disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic. The sleep of infants and toddlers is critical for their neurodevelopment, 1– 3 growth, 4 and physical health. 5 Brain maturation and the development of circadian rhythms occur during infancy and early childhood. 6 Sufficient sleep, regular sleep time, and development of sleep habits are essential during this developmental stage. 7 In addition to having a long-term effect on the mental health of the children and their parents, the sleep of infants and toddlers can also have a profound effect on family dynamics. 8, 9

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the daytime and nighttime schedule of children and their parents was affected by social distancing measures, occupational changes, and the consequent economic stressors that have occurred in many households. 10 Not only has the employment of parents been affected, but the use of at-home space has also been modified by virtual learning for school-aged children and remote work for adult household members. 11 These changes have affected the sleep, well-being, and general functioning of the entire family. Most of the literature on the effect of the pandemic on sleep describes how the sleep of school-aged children and adults was affected by pandemic measures and the COVID-19 virus itself. There are few studies that describe the sleep of infants and young children during times when there have been strict COVID-19 public health measures.

Cultural and geographic differences affect the sleep of infants and toddlers. 12 The effect of the pandemic on children’s sleep in Italy, 13– 16 Spain, 17, 18 China, 19 Singapore, 20 Japan, 21 Chile, 22 and Israel 23 has been described; notably, many of these studies do not include infants, and most include older children in their analyses. The sleep of infants and toddlers living in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic is understudied. Two studies of videosomnography data from the Nanit baby monitor (Nanit, New York, NY) have assessed the sleep of U.S. infants and toddlers during the COVID-19 pandemic. 24, 25 One compared the sleep of U.S. infants whose parents have worked from home during the pandemic compared to those who have maintained their traditional work schedule. 24 The second compared the sleep characteristics and screen time of infants and toddlers between November and December 2019 to the same months in 2020, along with data on parental sleep. 25 Although these studies provide important information, neither of them assessed sleep throughout the first year (2020) of the pandemic. Notably, data from these studies were collected from users of the Nanit baby monitor and may overrepresent a higher-income demographic. Other studies that included children from the United States compared the sleep of children in high-, middle-, and low-income countries in aggregate, 26 and another compared the sleep of children from North America, South America, the Middle East, and Europe in aggregate. 27 Yet gaps remain, and these have implications for long-term societal recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Anecdotally, some of the parents of our patients have described an increase in symptoms of behavioral sleep problems during the COVID-19 pandemic. These concerns include an increase in symptoms of behavioral insomnia of childhood (ie, the requirement of caregiver or parental presence during sleep initiation when adults work from home), poor sleep hygiene, difficulty with naps, and increased frustration with sleep in the parent-child dyad. Changes in the use of home space have often included the conversion of a bedroom to a home office or the use of multipurpose shared living space for adults to supervise naps while working remotely. Parents have reported that changes in their home environment led to daytime nap difficulty, an increase in room-sharing, and an increase in bed-sharing. Such parental concerns led us to conduct the present study.

The goal of this study was to objectively characterize the sleep of infants and toddlers over the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. We also aimed to understand how these attributes differed between the prelockdown and postlockdown periods of 2020.

METHODS

From January 17, 2020, to December 7, 2020, we used an electronic questionnaire to survey parents of children younger than age 3 years about their children’s sleep. The questionnaire items were selected based on validated instruments designed for older children (the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire, 28 the Child Sleep Habits Questionnaire, 29 the OSA-18, 30 and the Tayside Children’s Sleep Questionnaire 31), existing screening tools for disordered sleep in infants (the Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire 32 and the Sleep and Settle Questionnaire 33), and consensus from a clinical expert panel that included sleep medicine physicians, a developmental-behavioral pediatrician, a pediatric psychologist, and pediatric neurologists. Additional questions included demographic and medical history information.

One parent per child completed the questionnaire; each participated one time. Participants were recruited both in-person from University of Michigan pediatric subspecialty and general pediatrics clinics and online via Facebook posts and flyers placed on hospital announcement boards. The respondents were primarily from the midwestern United States. The data were collected as part of a larger study, which had begun prepandemic, to validate a novel questionnaire for infant and toddler sleep. Questionnaire details are described in the supplemental material. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Michigan.

We used a cross-sectional design to assess the sleep characteristics of infants and toddlers over 2020. The year was divided into quarters: quarter 1 spanned from January–March, quarter 2 spanned from April–June, quarter 3 spanned from July–September, and quarter 4 spanned from October–December. We compared parental reports of total sleep time (TST), sleep onset latency (SOL), parental frustration with sleep, and nap consistency in each quarter. Of particular interest was a comparison between sleep in quarter 1 (which was primarily a prelockdown period in the midwestern United States) and the subsequent quarters. Stay-at-home orders began in mid- to late March in the midwestern United States. Age was categorized as ≤ 6 months, 6 to ≤ 12 months, 12 to ≤ 24 months, and 24 to ≤ 36 months. Annual household income was categorized in U.S. dollars as ≤ $25,000, $25,000 to ≤ $50,000, $50,000 to ≤ $100,000, $100,000 to ≤ $150,000, and > $150,000.

Descriptive statistics were employed to characterize the study sample. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) analyses were performed to compare mean TST, mean SOL, and parental frustration with sleep in each year quarter. Two-way ANOVA analyses were used to compare mean TST and mean SOL in each year quarter when adjusted for age category.

Multivariable linear regression included TST, SOL, and parental frustration with sleep (on a scale of 1–5, where 1 was “strongly disagree” and 5 was “strongly agree”) as dependent variables and year quarter, child’s age category, prematurity, child’s comorbidities, maternal age (at the time of the child’s birth), parenting experience (first-time caregiver), household income, and room-sharing status (children had their own room) as independent variables. These variables were included in the model because of the biological plausibility that they might influence the dependent variables of interest.

Logistic regression included nap consistency (napping at the same time daily) as the dependent variable, and year quarter (reference quarter 1), child’s age (reference age category ≤ 6 months), prematurity, comorbidity, maternal age, parenting experience, annual household income (reference ≤ $25,000), and room-sharing as independent variables. These variables were included in the model because of the biologic plausibility that they might influence nap consistency.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.; Cary, NC). Plots were generated using RStudio Version 1.3.1093 (Integrated Development for R, RStudio, PBC; Boston, MA).

RESULTS

Of the 594 children reflected in the sample, the mean age was 18.5 ± 9.7 months and 52% were female (Table 1). Prematurity and medical comorbidities (excluding a sleep disorder) were reported for 8% and 15% of children, respectively. The mean maternal age at the time of birth of the child described in the questionnaire was 31.8 ± 4.5 years. Approximately half of the respondents (52%) were first-time parents.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical profile of 594 participants in the sample.

| Year Quarter 1 (n = 36) | Year Quarter 2 (n = 238) | Year Quarter 3 (n = 269) | Year Quarter 4 (n = 51) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mo, mean (SD) | 13.04 (8.5) | 18.51 (9.7) | 19.32 (9.5) | 17.84 (10.0) | .003a |

| Maternal age at the time of the child’s birth, y, mean (SD) | 32.42 (3.8) | 31.82 (4.5) | 31.82 (4.3) | 30.76 (5.5) | .34a |

| Age category, n (%) | .004b | ||||

| ≤ 6 months | 12 (33.3) | 34 (14.3) | 30 (11.2) | 5 (9.8) | |

| 6 to ≤ 12 months | 6 (16.7) | 36 (15.1) | 40 (14.9) | 14 (27.5) | |

| 12 to ≤ 24 months | 14 (38.9) | 83 (34.8) | 104 (38.7) | 14 (27.5) | |

| 24 to ≤ 36 months | 4 (2.0) | 85 (35.7) | 95 (35.3) | 18 (35.3) | |

| Sex, n (%) | .54b | ||||

| Female | 16 (44.4) | 119 (50.6) | 146 (54.5) | 24 (47.1) | |

| Race, n (%) | .14c | ||||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 (3.6) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Asian | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Black or African American | 2 (7.1) | 7 (3.3) | 5 (2.1) | 4 (9.3) | |

| More than 1 race | 4 (14.3) | 19 (8.8) | 19 (8.1) | 7 (16.3) | |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| White | 21 (75.0) | 183 (85.1) | 207 (87.7) | 32 (74.4) | |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Prefer not to disclose | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | .27c | ||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 (12.0) | 15 (7.2) | 11 (4.8) | 4 (9.3) | |

| Prematurity, n (%) | 3 (8.3) | 21 (8.8) | 22 (8.2) | 3 (6.0) | .93b |

| Presence of comorbidity, n (%) | 9 (25.0) | 42 (17.7) | 30 (11.2) | 10 (20.0) | .04b |

| Parenting experience, participant is the parent’s first child, n (%) | 24 (66.7) | 125 (53.2) | 130 (49.2) | 26 (51.0) | .25b |

| Annual household income, n (%) | .0008b | ||||

| < $25,000 | 0 (0.0) | 15 (7.1) | 3 (1.3) | 4 (9.5) | |

| $25,000–$50,000 | 4 (15.4) | 40 (19.0) | 24 (10.3) | 6 (14.3) | |

| $50,000–$100,000 | 8 (30.8) | 81 (38.4) | 77 (33.2) | 17 (40.5) | |

| $100,000–$150,000 | 7 (26.9) | 48 (22.8) | 80 (34.5) | 6 (14.3) | |

| > $150,000 | 7 (26.9) | 27 (12.8) | 48 (20.7) | 9 (21.4) | |

| Room-sharing, participant has his or her own room, n (%) | 25 (73.5) | 154 (65.8) | 214 (81.1) | 37 (75.5) | .0018b |

aOne-way ANOVA. bChi-square test. cFisher exact test. ANOVA = analysis of variance, SD = standard deviation.

Overall, at least 87% of our participants were recruited from a nonclinical setting. Most participants were recruited from Facebook and Instagram posts (n = 320) or from a website for people interested in participation in research at the University of Michigan (https://umhealthresearch.org; n = 254). Other participants were recruited when they responded to a poster in the hospital cafeteria or hallway (n = 68), the sleep clinic (n = 8), the sleep laboratory during a polysomnogram (n = 51), the general pediatrics clinic (n = 13), or the pediatric neurology clinic (n = 8), or through a mailed invitation (n = 7).

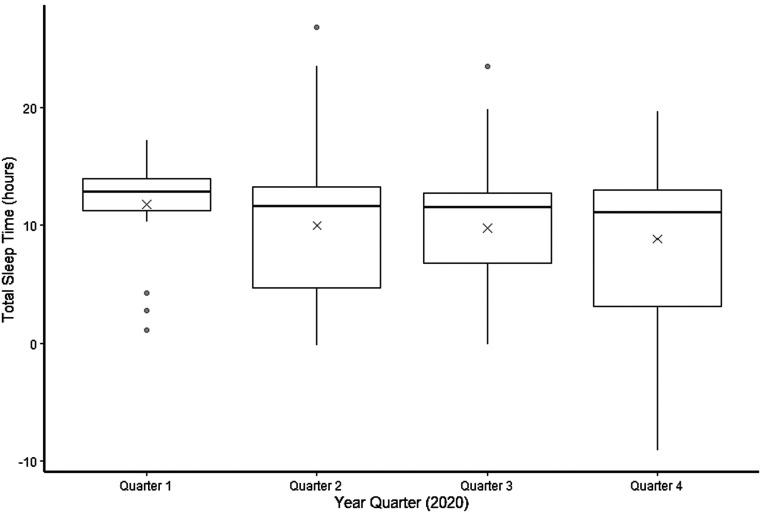

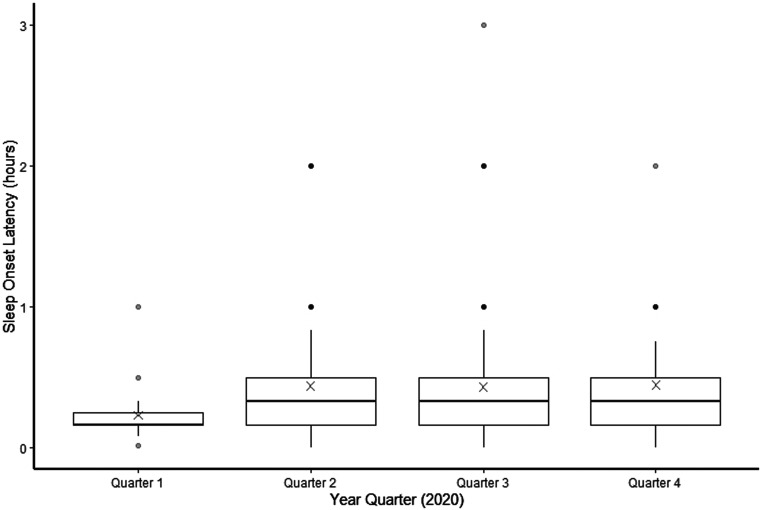

One-way ANOVA analyses showed no difference in parent-reported mean TST (P = .19) or parent-reported mean SOL across all year quarters (P = .06), although there was a significant decrease in the mean TST from quarter 1 (11.75 ± 4.27 hours) to quarter 4 (8.83 ± 5.87 hours; P = .03). There was a significant increase in mean SOL from quarter 1 (0.23 ± 0.18 hours) to the subsequent quarters: quarter 2 (0.44 ± 0.41 hours; P = .009), quarter 3 (0.43 ± 0.39 hours; P = .01), and quarter 4 (0.45 ± 0.39 hours; P = .02). There was no change in mean SOL from quarters 2–4 (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Outlier values of TST > 24 hours and < 0 hours reflected instances when parents made comments such as “my child sleeps for days” or “my child hasn’t slept for days.” An unadjusted 1-way ANOVA did not indicate a significant effect of year quarter on parental frustration with sleep (P = .21), and a chi-square test did not show a significant effect of year quarter on nap consistency (P = .06; Table 2).

Figure 1. Cross-sectional depiction of the distribution of TST at each year quarter.

In a 2-way ANOVA, the effect of year quarter was not significant (P = .49) and the effect of age category was significant (P = .003). The bottom of a box represents the 25th percentile value of TST during that year quarter, and the top of the box represents the 75th percentile of TST. The horizontal line in the center of the box represents the median value. The X represents the mean value. The IQR is the difference between the 75th and 25th percentile values. The tips of the whiskers represent a value of 1.5 × IQR in either direction. The circles represent outliers. ANOVA = analysis of variance, IQR = interquartile range, TST = total sleep time.

Figure 2. Cross-sectional depiction of the distribution of SOL at each year quarter.

In a 2-way ANOVA, the effect of year quarter was not significant (P = .29) and the effect of age category was significant (P < .0001). The bottom of a box represents the 25th percentile value of SOL during that year quarter, and the top of the box represents the 75th percentile of SOL. The horizontal line in the center of the box represents the median value. The X represents the mean value. The IQR is the difference between the 75th and 25th percentile values. The tips of the whiskers represent a value of 1.5 × IQR in either direction. The circles represent outliers. ANOVA = analysis of variance, IQR = interquartile range, SOL = sleep onset latency.

Table 2.

Summary of outcomes by year quarter.

| Quarter 1 (n = 36) | Quarter 2 (n = 238) | Quarter 3 (n = 269) | Quarter 4 (n = 51) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TST, h, mean (SD) | 11.75 (4.27) | 9.97 (5.30) | 9.74 (4.77) | 8.83 (5.87) | .19a |

| SOL, h, mean (SD) | 0.23 (0.18) | 0.44 (0.41) | 0.43 (0.39) | 0.45 (0.39) | .06a |

| Parental frustration with sleep, mean (SD)* | 2.14 (1.43) | 2.06 (1.37) | 1.83 (1.14) | 1.98 (1.42) | .21a |

| Nap consistency, napping at the same time daily, n (%) | 23 (79.31) | 188 (87.85) | 222 (92.50) | 35 (83.33) | .06b |

*On a scale from 1–5 where 1 is least frustrated and 5 is most frustrated. aOne-way ANOVA. bChi-square test. ANOVA = analysis of variance, SD = standard deviation, SOL = sleep onset latency, TST = total sleep time.

A 2-way ANOVA with year quarter and age category as factors showed a significant effect of age category on TST (P = .003). The differences were most pronounced between the ≤ 6 months group and the 12 to ≤ 24 months group (difference in means, 2.8 hours; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.9–4.8; P = .0013), and between the ≤ 6 months group and the 24 to ≤ 36 months group (difference in means, 3.2 hours; 95% CI, 1.2–52.2; P = .0003). A 2-way ANOVA with year quarter and age category as factors showed a significant effect of age category on SOL (P < .0001). The differences were most pronounced between the ≤ 6 months group and the 24 to ≤ 36 months group (difference in means, –0.2 hours; 95% CI, –0.4 to –0.1; P < .0001), the 6 to ≤ 12 months and 24 to ≤ 36 months groups (difference in means, –0.2 hours; 95% CI, –0.3 to –0.04; P = .004), and the 12 to ≤ 24 months and 24 to ≤ 36 months groups (difference in means, –0.2 hours; 95% CI, –0.3 to −0.07; P = .0001).

Multivariable linear regression showed no significant difference in TST between year quarter 1 and the subsequent year quarters when adjusted for child’s age category, prematurity, presence of a comorbidity, maternal age at the time of the child’s birth, parenting experience, household income, and room-sharing (quarter 1: reference; quarter 2: β = 1.15, P = .33; quarter 3: β = –1.17, P = .32; quarter 4: β = −2.33, P = .10). There was a difference in SOL of 9.6 minutes between year quarter 3 and year quarter 1 (P = .04).

Children aged 6 to ≤ 12 months had a TST that was 2 hours and 52 minutes less than that of children aged ≤ 6 months old (P = .0004). Children aged 24 to ≤ 36 months had a TST that was 3 hours and 15 minutes less than that of children aged ≤ 6 months (P < .0001). SOL was 16.8 minutes more in children aged 24 to ≤ 36 months compared to children aged ≤ 6 months (P < .0001). Parental frustration with sleep was markedly greater in children aged > 6 months compared to children aged ≤ 6 months (quarter 2: β = 0.52, P = .01; quarter 3: β = 0.36, P = .05; quarter 4: β = 0.52, P = .005).

Each year increase in maternal age was associated with a 2.4-minute decrease in TST (P = .05).

Children whose caregivers had an annual household income of $100,000–150,000 had a 9-minute shorter SOL than children whose caregivers had an annual household income of < $25,000 (P = .03). Children whose caregivers had an annual household income of > $150,000 had an 11.4-minute shorter SOL than children whose caregivers had an annual household income of < $25,000 (P = .01).

Children with their own room had a 5.4-minute shorter SOL compared to children who shared a room. Parents of children who had their own room were less frustrated with sleep than parents of children who shared a room (β = –0.35, P = .01).

Neither parenting experience nor the presence of a comorbidity had a significant effect on TST or SOL; however, the association between the presence of a comorbidity and parental frustration with sleep approached significance (β = 0.26, P = .09; Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable linear regression models of TST, SOL, and parental frustration with sleep.

| TST (h) | SOL (h) | Parental Frustration with Sleep* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter Estimate (β) | P | Parameter Estimate (β) | P | Parameter Estimate (β) | P | |

| Year quarter | ||||||

| 1 | Reference | n/a | Reference | n/a | Reference | n/a |

| 2 | −1.15 | .33 | 0.14 | .07 | −0.26 | .32 |

| 3 | −1.17 | .32 | 0.16 | .04* | −0.40 | .12 |

| 4 | −2.33 | .10 | 0.12 | .21 | −0.33 | .30 |

| Age category | ||||||

| ≤ 6 mo | Reference | n/a | Reference | n/a | Reference | n/a |

| 6 to ≤ 12 mo | −1.78 | .06 | 0.08 | .20 | 0.52 | .01** |

| 12 to ≤ 24 mo | −2.86 | .0004** | 0.10 | .07 | 0.36 | .05** |

| 24 to ≤ 36 mo | −3.25 | < .0001** | 0.28 | < .0001** | 0.52 | .005** |

| Prematurity | −0.14 | .91 | −0.09 | .16 | 0.20 | .32 |

| Presence of a comorbidity | 0.18 | .68 | 0.23 | .54 | 0.26 | .09 |

| Maternal age (at the time of the child’s birth) | −0.04 | .05** | −0.002 | .54 | −0.02 | .12 |

| Parenting experience (first-time caregiver) | −0.36 | .51 | 0.05 | .16 | −0.06 | .64 |

| Annual household income | ||||||

| < $25,000 | Reference | n/a | Reference | n/a | Reference | n/a |

| $25,000–$50,000 | −0.73 | .51 | −0.009 | .91 | 0.43 | .10 |

| $50,000–$100,000 | −0.84 | .38 | −0.11 | .10 | 0.28 | .22 |

| $100,000–$150,000 | −1.10 | .27 | −0.15 | .03** | 0.22 | .38 |

| > $150,000 | −1.05 | .32 | −0.19 | .01** | 0.12 | .63 |

| Room-sharing (child has his or her own room) | 0.29 | .61 | −0.09 | .05** | −0.35 | .01** |

TST: R2 = 0.06, F(15,430) = 1.78, P = .004. SOL: R2 = 0.12, F(15,466) = 4.28, P < .0001. Parental frustration: R2 = 0.06, F(15,500) = 2.29, P = .004. *On a scale from 1–5 where 1 is least frustrated and 5 is most frustrated. **P < .05. SOL = sleep onset latency, TST = total sleep time.

A multivariable logistic regression model of nap consistency across the year quarters showed a significant effect of age category on nap consistency. The adjusted odds of having consistent naps in the 6 to ≤ 12 months age group compared to the ≤ 6 months age group was 5.2 (95% CI, 1.81–14.82). The adjusted odds of having consistent naps in the 12 to ≤ 24 months age group compared to the ≤ 6 months age group was 6.6 (95% CI, 2.8–16.0). The adjusted odds of having consistent naps in the 24 to ≤ 36 months age group was 3.4 (95% CI, 1.5–7.4). The adjusted association between a child having his or her own room and nap consistency approached significance (adjusted odds ratio, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.0–3.7; Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression model with nap consistency as the dependent variable.

| OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Year quarter | |

| 1 | Reference |

| 2 | 1.5 (0.5–4.7) |

| 3 | 2.2 (0.7–7.3) |

| 4 | 0.8 (0.2–3.2) |

| Child’s age | |

| ≤ 6 mo | Reference |

| 6 to ≤ 12 mo | 5.2 (1.8–14.8) |

| 12 to ≤ 24 mo | 6.6 (2.8–16.0) |

| 24 to ≤ 36 mo | 3.4 (1.5–7.4) |

| Annual household income | |

| ≤ $25,000 | Reference |

| $25,000 to ≤ $50,000 | 1.0 (0.3–3.9) |

| $50,000 to ≤ $100,000 | 1.2 (0.3–4.4) |

| $100,000 to ≤ $150,000 | 2.7 (0.6–11.9) |

| > $150,000 | 1.1 (0.3–4.4) |

| Maternal age | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) |

| Parenting experience (respondent’s first child) | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) |

| Presence of child’s comorbidity | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) |

| Prematurity | 3.3 (0.7–15.7) |

| Room-sharing (child has his or her own room) | 1.9 (1.0–3.7) |

Model fit statistics: c = 0.776; the percentage of concordance between the observed values and predicted probability from the model is 77.6%. Model statistics: intercept: β = 0.13, P = .92; year quarter 2: β = 0.39, P = .52; year quarter 3: β = 0.80, P = .18; year quarter 4: β = −0.22, P = .76. Child’s age category: 6 to ≤ 12 months, β = 1.65, P = .002; 12 to ≤ 24 months, β = 1.89, P < .0001; 24 to ≤ 36 months, β = 1.21, P = .003. Annual household income: $25,000 to ≤ $50,000, β = −0.01, P = .98; $50,000 to ≤ $100,000, β = 0.19, P = .77; $100,000 to ≤ $150,000, β = 0.99, P = .19; > $150,000, β = 0.07, P = .92. Maternal age: β = −0.004, P = .92. Parenting experience: β = −0.48, P = .15. Presence of child’s comorbidity: β = −0.56, P = .14. Prematurity: β = 1.21, P = .13. Room-sharing: β = 0.63, P = .07. CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

DISCUSSION

Sleep is one of the many facets of life impacted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the many changes that occurred during the lockdown period, the factors that had the most significant effect on sleep were related to social determinants of health and not the time of the lockdown period itself. Year quarter did not retain a significant effect on TST after we adjusted for key factors such as the child’s age, history of prematurity, presence of a comorbidity, maternal age at the time of the child’s birth, parenting experience, household income, and room-sharing. However, reported SOL increased in quarter 3 (July–September 2020) by 9.6 minutes. The increase in SOL during quarter 3 may have been attributed to a convergence of economic, social, and political unrest that affected families in the midwestern United States during that time—this is a topic that requires further study.

Sociological factors contributed to the parent-reported sleep times and sleep characteristics. A lower household income was associated with an increase in SOL. Children whose caregivers had an annual household income of $100,000–150,000 had a 9-minute shorter SOL than children whose caregivers had an annual household income of < $25,000. Children whose caregivers had an annual household income of > $150,000 had a 11.4-minute shorter SOL than children whose caregivers had an annual household income of < $25,000. For context, in adults, the mean reduction in SOL with zolpidem 10 mg is 14.8 minutes, with zaleplon 5–20 mg it is 9.9 minutes, with zolpidem ER 12.5 mg it is 9 minutes, and with suvorexant 15–20 mg it is 6 minutes. 34

Unsurprisingly, TST and SOL were most associated with a child’s age. Parental frustration with sleep was most associated with a child’s age and if the child shared a bedroom. Parental frustration with sleep was not affected by year quarter, when adjusted for maternal age, parenting experience, and household income. The presence of a comorbidity approached significance in having an effect on parental frustration with sleep: This effect may not have been prominent in our sample because of the limited number (15%) of children in our sample with a comorbidity. The pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on low-income families, 35 who also tend to have a higher incidence of room-sharing. 36 Our results show how social determinants of health differentially impact sleep, which has added to the burden of inequity experienced with COVID-19 transmission. 37

In the adjusted analysis, with each year increase in maternal age, TST decreased by 2.4 minutes. The literature on the effect of maternal age on infant sleep time is limited; further investigation in this area is warranted to understand this result in the appropriate context.

We found that naps were more consistent in older children compared to younger children and that the effect of room-sharing approached significance in the odds of parents reporting that their child had consistent naps. Napping constitutes approximately 1–9 hours of TST each day between infancy and toddlerhood 38; therefore, consideration of how this aspect of sleep was affected during the lockdown phase of the pandemic is important to gain a more holistic perspective on this topic.

Our findings have similarities and differences compared with studies conducted both domestically and abroad during the pandemic, along with studies that were conducted over both short and long time courses. One study from the United States found that the sleep of babies whose parents maintained a normal work routine was less impacted by lockdown measures than the sleep of babies whose parents worked from home. 24 Although TST increased in the “work from home” babies, the number of parental visits to the bed increased as well. Our study did not account for whether the parent was working from home. A U.S. study using similar videosomnography data compared sleep from the end of 2019 to the end of 2020 and reported that infants from the 2020 group slept approximately 40 minutes more per night and had a delay in their sleep period. 25 The study also found that parental depression symptoms increased in 2020 compared to 2019. These 2 studies found that TST in U.S. infants and toddlers either stayed the same or increased, whereas ours found that TST either stayed the same or decreased after lockdown measures were instituted. Notably, these studies assessed postlockdown sleep over 2- and 3-month periods; the long-term impact of this alteration in parent-child interaction is uncertain. Increased nocturnal parental interaction is associated with fragmented sleep and the development of behavioral sleep disorders in infants. 39

The effect of the pandemic on the sleep of infants and toddlers outside of the United States seems to have varied. A Chilean study 22 of children ages 1–5 years conducted over a 2-month period found that the TST of older children decreased after their lockdown but that their screen time increased. Similar to our study, higher income was a protective factor in children’s sleep quality, and children who had 4 or more people living in their household had a greater reduction in sleep quality during the height of COVID-19 lockdowns. Children who lived in larger dwellings or in rural areas with more space had a lesser decrease in sleep quality compared to children who lived in a more confined environment. Those findings are aligned with our findings that room-sharing and lower household income may have had a negative effect on the sleep of U.S. infants and toddlers.

Cross-sectional Japanese and Spanish studies of infants and toddlers 17, 21 have reported that generally there was no difference in bedtime, wake time, or nocturnal sleep duration during lockdown; however, they found that children who stayed at home had increased screen time, less physical activity, increased SOL, and decreased TST compared to those who went to daycare and spent more time outdoors. Screen time and physical activity were not measured in our study.

An Italian longitudinal study 15 of children ages 3–6 years over the first 4 weeks of the lockdown in Italy reported that bedtime routines were initially more challenging and that sleep quality was poor. Bedtime routine and TST eventually stabilized; however, sleep quality remained poor. This result is consistent with our finding that mean SOL was stable during year quarters 2–4.

The results from several studies that included older children in addition to infants and toddlers suggest that sleep in older children was impacted differently during the lockdown phase of the COVID-19 pandemic than sleep in infants and toddlers. 14, 18, 20 These studies found that bedtime and wake time became delayed in older children and that TST increased in older school-aged children. Younger children did not experience an increase in TST and in fact were more likely to experience disorders of sleep initiation and maintenance than older children after the lockdown. Our unadjusted findings also showed an increase in SOL after the lockdown; however, we found that SOL significantly increased in the 24 to ≤ 36 months age group, whereas the increase in SOL in the 12 to ≤ 24 months age group approached significance.

Our results should be interpreted in the context of the study limitations. Our data were collected using a cross-sectional approach. Ideally, repeated measures collected through a longitudinal approach would have provided more accurate information on how sleep changed within individual children over the course of 2020, before and after the lockdown. Given that we examined 4 quarters of a single year, the role of seasonality could not be assessed. There were fewer participants in the reference prepandemic quarter than in the following year quarters; the same was true for the reference income category. A lower number of data points makes any analysis of the smaller-sized group more vulnerable to the effects of outliers or extreme deviations from the mean compared to groups with more participants. Although our results illustrate how social determinants of health such as household income and the presence of room-sharing (a proxy for the number of rooms per family member in a home) affected sleep during lockdown measures, we were not able to determine the effect of race on the sleep of infants and toddlers during this period because we had a limited number of Asian, Black, Indigenous, and Latino participants. Finally, we used parent-reported sleep estimates in our analyses as opposed to actigraphy or polysomnography, which are more objective measures of sleep. This method may have resulted in a less accurate representation of TST and SOL over the successive year quarters in 2020.

There are also notable strengths of this study. Our study period spanned a year and captured a pre- and postlockdown period. Many prior studies collected their sleep data over the duration of a few days to a few months. 13– 18, 20– 23, 25– 27, 41, 42 Among the studies that examined both a pre- and postlockdown period, there are a limited number that captured data collected during the prelockdown period itself 21, 24– 26 (as opposed to recall of prelockdown sleep characteristics 13, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 23, 27). Sleep in the early stages of childhood is different than that of older children, 38 and our study focused specifically on the infant and toddler period as opposed to children of those ages as part of a larger pediatric cohort. Our study also captured people from a range of economic backgrounds, potentially unlike the home videosomnography studies, 24, 25 which likely reflect the sleep of infants whose families can afford the device. Last, our study illustrates how the sleep of infants and toddlers was specifically impacted in the United States. Not only did countries across the globe implement COVID-19 precautions in their own unique manner, but there are also social and cultural norms that impact sleep behaviors. The current understanding of how lockdown measures impacted U.S. infants, toddlers, and their families is limited 24 because most data from U.S. infants and toddlers included in other studies were analyzed as part of an aggregate economic or geographic group. 26, 27

Not only is sleep critical for the long-term neurodevelopment, 1– 3 growth, 4 and physical health 5 of infants and toddlers, but it can also have a profound effect on family dynamics. 8, 9 Higher socioeconomic status has been associated with increased nocturnal sleep time, increased TST, better sleep hygiene, and decreased daytime napping 43– 45 during prepandemic times. Maternal cognition about setting limits, anger at infant demands, and doubts about parenting competence are significantly associated with infant sleep problems: A disruption in parent-child interactions leads to impairments in infant self-regulation and ultimately leads to disordered infant sleep. 39, 46 Our study notes that these factors were affected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Social determinants of health such as household income and dwelling size and the presence of a comorbidity differentially affected the sleep and parental attitudes toward sleep of midwestern U.S. infants in our study. The social and economic stress induced by the pandemic may have exacerbated these known relationships.

In conclusion, some of the most vulnerable children in our society are also the most vulnerable to developing disordered or insufficient sleep. This relationship has persisted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mitigation techniques such as behavioral sleep interventions can improve the sleep of infants and toddlers with and without comorbidities along with maternal mood. 47, 48 Our results illustrate that close attention (and possibly early intervention) must be focused on the sleep of infants and toddlers in these special populations both now and especially if another period of prolonged confinement should become necessary in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Dawn Dore-Stites (clinical psychology), Dr. Barbara Felt (developmental and behavioral pediatrics), Dr. Fauziya Hassan (pediatric pulmonology and sleep medicine), and Dr. Lisa Matlen (pediatric neurology and sleep medicine), who were part of our clinical expert panel.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CI

confidence interval

- SOL

sleep onset latency

- TST

total sleep time

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have seen and approved the manuscript. Work for this study was performed at the University of Michigan. This study was funded by National Institutes of Health 2T32HL110952-06. The Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research, funded by National Institutes of Health UL1TR002240, assisted with the online recruitment of participants. Consultants at Consulting for Statistics, Computing and Analytics Research at the University of Michigan assisted with statistical analyses. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Weisman O , Magori-Cohen R , Louzoun Y , Eidelman AI , Feldman R . Sleep-wake transitions in premature neonates predict early development . Pediatrics. 2011. ; 128 ( 4 ): 706 – 714 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shellhaas RA , Burns JW , Hassan F , Carlson MD , Barks JDE , Chervin RD . Neonatal sleep-wake analyses predict 18-month neurodevelopmental outcomes . Sleep. 2017. ; 40 ( 11 ): zsx144 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Page J , Lustenberger C , Fröhlich F . Social, motor, and cognitive development through the lens of sleep network dynamics in infants and toddlers between 12 and 30 months of age . Sleep. 2018. ; 41 ( 4 ): zsy024 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lampl M , Johnson ML . Infant growth in length follows prolonged sleep and increased naps . Sleep. 2011. ; 34 ( 5 ): 641 – 650 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miller AL , Lumeng JC , LeBourgeois MK . Sleep patterns and obesity in childhood . Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2015. ; 22 ( 1 ): 41 – 47 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brooks E , Canal MM . Development of circadian rhythms: role of postnatal light environment . Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013. ; 37 ( 4 ): 551 – 560 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ednick M , Cohen AP , McPhail GL , Beebe D , Simakajornboon N , Amin RS . A review of the effects of sleep during the first year of life on cognitive, psychomotor, and temperament development . Sleep. 2009. ; 32 ( 11 ): 1449 – 1458 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cook F , Conway LJ , Giallo R , Gartland D , Sciberras E , Brown S . Infant sleep and child mental health: a longitudinal investigation . Arch Dis Child. 2020. ; 105 ( 7 ): 655 – 660 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sadeh A , Mindell JA , Owens J . Why care about sleep of infants and their parents? Sleep Med Rev. 2011. ; 15 ( 5 ): 335 – 337 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics . Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on the employment situation news release and data . https://www.bls.gov/covid19/effects-of-covid-19-pandemic-and-response-on-the-employment-situation-news-release.htm . Accessed January 18, 2022. .

- 11. Digital Learning Collaborative . Snapshot 2019: a review of K-12 online, blended, and digital learning. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59381b9a17bffc68bf625df4/t/5cae3c05652dea4d690f5315/1554922508490/DLC-KP-Snapshot2019_040819.pdf . Accessed January 18, 2022. .

- 12. Lin QM , Spruyt K , Leng Y , et al . Cross-cultural disparities of subjective sleep parameters and their age-related trends over the first three years of human life: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Sleep Med Rev. 2019. ; 48 : 101203 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dondi A , Fetta A , Lenzi J , et al . Sleep disorders reveal distress among children and adolescents during the Covid-19 first wave: results of a large web-based Italian survey . Ital J Pediatr. 2021. ; 47 ( 1 ): 130 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bruni O , Malorgio E , Doria M , et al . Changes in sleep patterns and disturbances in children and adolescents in Italy during the Covid-19 outbreak [published online ahead of print, 2021. Feb 9. Sleep Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dellagiulia A , Lionetti F , Fasolo M , Verderame C , Sperati A , Alessandri G . Early impact of COVID-19 lockdown on children’s sleep: a 4-week longitudinal study . J Clin Sleep Med. 2020. ; 16 ( 9 ): 1639 – 1640 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Di Giorgio E , Di Riso D , Mioni G , Cellini N . The interplay between mothers’ and children behavioral and psychological factors during COVID-19: an Italian study . Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021. ; 30 ( 9 ): 1401 – 1412 . . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cachón-Zagalaz J , Zagalaz-Sánchez ML , Arufe-Giráldez V , Sanmiguel-Rodríguez A , González-Valero G . Physical activity and daily routine among children aged 0-12 during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain . Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. ; 18 ( 2 ): 703 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ventura PS , Ortigoza AF , Castillo Y , et al . Children’s health habits and COVID-19 lockdown in Catalonia: implications for obesity and non-communicable diseases . Nutrients. 2021. ; 13 ( 5 ): 1657 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tso WWY , Wong RS , Tung KTS , et al . Vulnerability and resilience in children during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print, 2020. Nov 17]. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lim MTC , Ramamurthy MB , Aishworiya R , et al . School closure during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic—impact on children’s sleep . Sleep Med. 2021. ; 78 : 108 – 114 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shinomiya Y , Yoshizaki A , Murata E , Fujisawa TX , Taniike M , Mohri I . Sleep and the general behavior of infants and parents during the closure of schools as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic: comparison with 2019 data . Children (Basel). 2021. ; 8 ( 2 ): 168 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aguilar-Farias N , Toledo-Vargas M , Miranda-Marquez S , et al . Sociodemographic predictors of changes in physical activity, screen time, and sleep among toddlers and preschoolers in Chile during the COVID-19 pandemic . Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. ; 18 ( 1 ): 176 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zreik G , Asraf K , Haimov I , Tikotzky L . Maternal perceptions of sleep problems among children and mothers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Israel . J Sleep Res. 2021. ; 30 ( 1 ): e13201 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kahn M , Barnett N , Glazer A , Gradisar M . Infant sleep during COVID-19: longitudinal analysis of infants of US mothers in home confinement vs working as usual . Sleep Health. 2021. ; 7 ( 1 ): 19 – 23 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kahn M , Barnett N , Glazer A , Gradisar M . COVID-19 babies: auto-videosomnography and parent reports of infant sleep, screen time, and parent well-being in 2019 vs 2020 . Sleep Med. 2021. ; 85 : 259 – 267 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Okely AD , Kariippanon KE , Guan H , et al . Global effect of COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep among 3- to 5-year-old children: a longitudinal study of 14 countries . BMC Public Health. 2021. ; 21 ( 1 ): 940 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kaditis AG , Ohler A , Gileles-Hillel A , et al . Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on sleep duration in children and adolescents: a survey across different continents . Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021. ; 56 ( 7 ): 2265 – 2273 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chervin RD , Hedger K , Dillon JE , Pituch KJ . Pediatric sleep questionnaire (PSQ): validity and reliability of scales for sleep-disordered breathing, snoring, sleepiness, and behavioral problems . Sleep Med. 2000. ; 1 ( 1 ): 21 – 32 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Owens JA , Spirito A , McGuinn M . The Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children . Sleep. 2000. ; 23 ( 8 ): 1043 – 1051 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Franco RA Jr , Rosenfeld RM , Rao M . First place—resident clinical science award 1999. Quality of life for children with obstructive sleep apnea . Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000. ; 123 ( 1 ): 9 – 16 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McGreavey JA , Donnan PT , Pagliari HC , Sullivan FM . The Tayside Children’s Sleep Questionnaire: a simple tool to evaluate sleep problems in young children . Child Care Health Dev. 2005. ; 31 ( 5 ): 539 – 544 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sadeh A . A brief screening questionnaire for infant sleep problems: validation and findings for an Internet sample . Pediatrics. 2004. ; 113 ( 6 ): e570 – e577 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Matthey S . The sleep and settle questionnaire for parents of infants: psychometric properties . J Paediatr Child Health. 2001. ; 37 ( 5 ): 470 – 475 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Matheson E , Hainer BL . Insomnia: pharmacologic therapy . Am Fam Physician. 2017. ; 96 ( 1 ): 29 – 35 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sharma SV , Chuang RJ , Rushing M , et al . Social determinants of health-related needs during COVID-19 among low-income households with children . Prev Chronic Dis. 2020. ; 17 : 200322 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Blake K , Kellerson R , Simic A . Measuring overcrowding in housing. Prepared for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. https://www.huduser.gov/publications/pdf/measuring_overcrowding_in_hsg.pdf . Accessed January 18, 2022. .

- 37. Chang HY , Tang W , Hatef E , Kitchen C , Weiner JP , Kharrazi H . Differential impact of mitigation policies and socioeconomic status on COVID-19 prevalence and social distancing in the United States . BMC Public Health. 2021. ; 21 ( 1 ): 1140 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Iglowstein I , Jenni OG , Molinari L , Largo RH . Sleep duration from infancy to adolescence: reference values and generational trends . Pediatrics. 2003. ; 111 ( 2 ): 302 – 307 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sadeh A , Tikotzky L , Scher A . Parenting and infant sleep . Sleep Med Rev. 2010. ; 14 ( 2 ): 89 – 96 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wearick-Silva LE, Richter SA, Viola TW, Nunes ML; COVID-19 Sleep Research Group. Sleep quality among parents and their children during COVID-19 pandemic in a Southern - Brazilian sample [published online ahead of print, 2021 Aug 23]. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2021;S0021-7557(21)00112-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41. Sismanlar Eyuboglu T , Aslan AT , Ramaslı Gursoy T , et al . Sleep disturbances in children with cystic fibrosis, primary ciliary dyskinesia and typically developing children during COVID-19 pandemic . J Paediatr Child Health. 2021. ; 57 ( 10 ): 1605 – 1611 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Markovic A , Mühlematter C , Beaugrand M , Camos V , Kurth S . Severe effects of the COVID-19 confinement on young children’s sleep: a longitudinal study identifying risk and protective factors . J Sleep Res. 2021. ; 30 ( 5 ): e13314 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tomfohr-Madsen L , Cameron EE , Dhillon A , et al . Neighborhood socioeconomic status and child sleep duration: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Sleep Health. 2020. ; 6 ( 5 ): 550 – 562 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jones CH , Ball H . Exploring socioeconomic differences in bedtime behaviours and sleep duration in English preschool children . Infant Child Dev. 2014. ; 23 ( 5 ): 518 – 531 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nevarez MD , Rifas-Shiman SL , Kleinman KP , Gillman MW , Taveras EM . Associations of early life risk factors with infant sleep duration . Acad Pediatr. 2010. ; 10 ( 3 ): 187 – 193 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Morrell JM . The role of maternal cognitions in infant sleep problems as assessed by a new instrument, the Maternal Cognitions About Infant Sleep Questionnaire . J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999. ; 40 ( 2 ): 247 – 258 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hiscock H , Wake M . Randomised controlled trial of behavioural infant sleep intervention to improve infant sleep and maternal mood . BMJ. 2002. ; 324 ( 7345 ): 1062 – 1065 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tsai SY , Lee WT , Lee CC , Jeng SF , Weng WC . Behavioral-educational sleep interventions for pediatric epilepsy: a randomized controlled trial . Sleep. 2020. ; 43 ( 1 ): zsz211 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]