Abstract

Background

Chronic cough, i.e., cough lasting longer than eight weeks, affects approximately 10% of the population and is a common reason for outpatient medical consultation. Its differential diagnosis is extensive, and it is generally evaluated in poorly structured fashion with a variety of diagnostic techniques. The German Clinical Practice Guideline on Acute and Chronic Cough was updated in 2021 and contains a description of the recommended stepwise, patient-centered, and evidence-based procedure for the management of chronic cough.

Methods

The guideline has been updated in accordance with the findings of a systematic search of the literature for international guidelines and systematic reviews. All recommendations were developed in an interdisciplinary manner and agreed upon by formal consensus. The target group consists of adult patients with cough.

Results

History-taking, after the exclusion of red flags, should include questioning about smoking status, medications, and relevant present and past illnesses (COPD, asthma). Subsequent diagnostic testing should include a chest x-ray and pulmonary function tests. If the patient is taking an ACE inhibitor, a test of drug discontinuation can be carried out first. Radiologically detected pulmonary masses or evidence of rare diseases (interstitial lung diseases, bronchiectasis) are an indication for chest CT or for direct referral to an appropriate specialist. If the imaging studies and pulmonary function tests are normal, the patient is most likely suffering from a disease entity that can be treated empirically, such as upper airway cough syndrome or cough variant asthma. Any patient with an unexplained or refractory cough must receive proper patient education; individual therapeutic trials of physiotherapeutic or speech-therapeutic methods are possible, as is the off-label use of gabapentin or morphine.

Conclusion

Chronic cough should be evaluated according to an established diagnostic algorithm in collaboration with specialists. Treatments such as inhaled corticosteroids should be tested exhaustively in accordance with the guidelines, and the possibility of multiple causes as well as the role of patient compliance should be kept in mind before a diagnosis of unexplained or intractable cough is assigned.

Cough is the symptom responsible for almost one in ten primary care consultations (1). The internationally established classification of cough is based on duration. It is distinguished between acute cough (up to 8 weeks in duration) and chronic cough (> eight weeks in duration). In addition, cough that lasts for three to eight weeks is classified as subacute cough by some authors (2). Given the lack of comprehensive prevalence and incidence data, it is estimated that about 10% of the adult population suffers from chronic cough (3).

Chronic cough can be debilitating as the resulting distress significantly impairs the patient’s quality of life (4). While most cases of acute cough are related to infection, the diagnostic work-up of chronic cough is made difficult by the long list of differential diagnoses. This can lead to both over-treatment and under-treatment. Key differential diagnoses include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in smokers, bronchial asthma, drug-related cough, and empirically treated conditions such as upper airway cough syndrome (UACS), cough variant asthma, eosinophilic bronchitis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), while diseases such as tuberculosis and interstitial lung diseases are among the rare causes (5).

The diagnosis “unexplained or refractory cough “ is typically assigned hastily and without a structured approach. On the other hand, even after numerous consultations with specialists many patients with chronic cough have still not been diagnosed and consequently miss out on adequate treatment (6). Nonpharmacological management options are not widely known, and off-label therapeutic trials can compromise patient safety if not carried out properly.

Under the leadership of the German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemein- und Familienmedizin), the update of the S3-level Clinical Practice Guideline on Acute and Chronic Cough of the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF, Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften) was completed in June 2021 with the participation of the German Society for Infectious Diseases, the German Respiratory Society and the German Society for Phytotherapy.

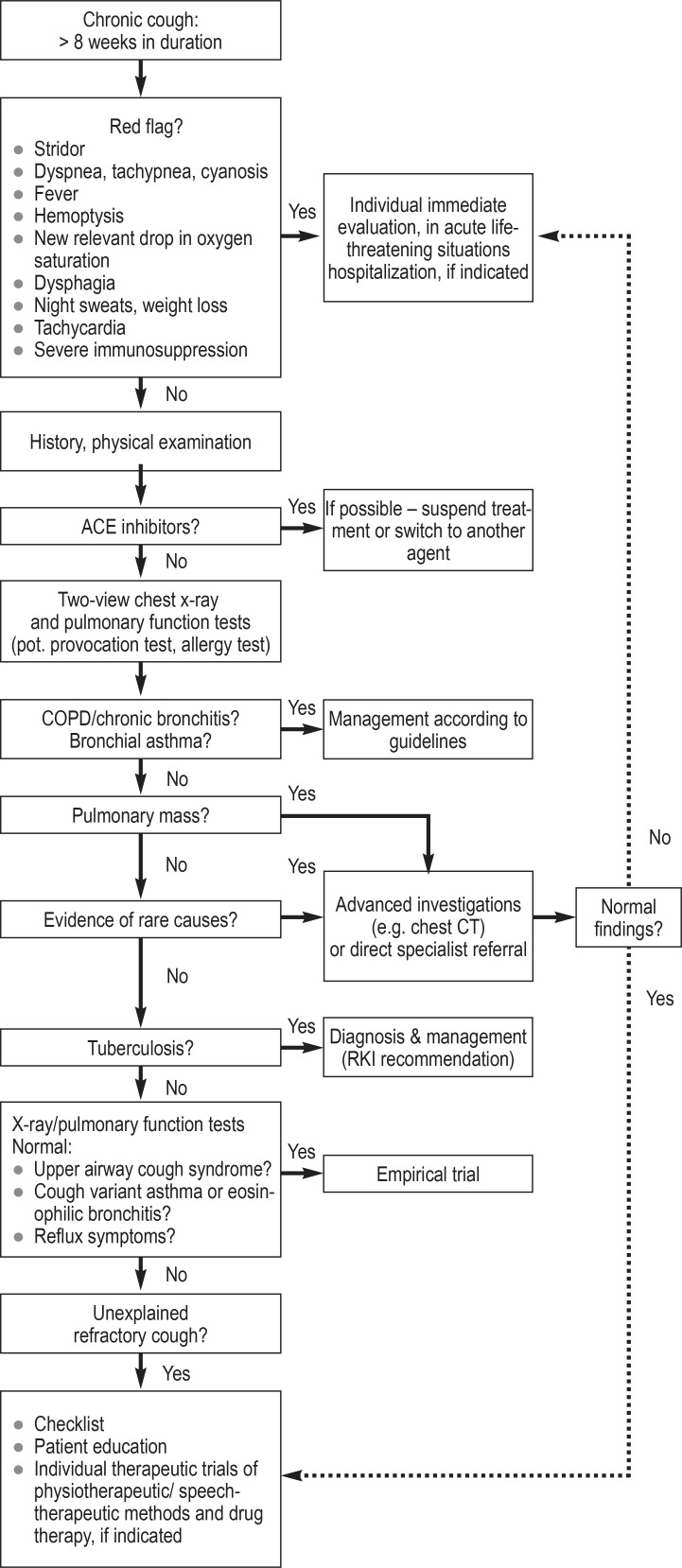

In the elaborations on chronic cough, a stepwise clinical approach with targeted diagnostic testing, empirical treatments, patient-centered consultations, and a structured procedure for unexplained or refractory cough (Checklist) was developed and summarized in a clinical algorithm (figure).

Figure.

Algorithm for structured process in patients with chronic or refractory cough

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CT, computed tomography; RKI, Robert Koch Institute

Methods

In order to establish the existing evidence base, a systematic search of the literature was conducted in Medline (via PubMed) and in the guideline portals. In addition, a search for updates of the source guidelines of the 2014 version of the AWMF guideline was carried out. The AGREE II tool was used to assess the quality of the guidelines included (5).

Furthermore, a systematic search for reviews was conducted and the methodological quality was assessed using the AMSTAR-2 tool. The search strategies and evaluations are described in the eMethods. In terms of patient involvement, a search of the literature on the patient perspective in people living with chronic cough was conducted. In the AWMF-coordinated consensus conference, the recommendations were discussed and agreed upon. All stakeholders involved in the guideline development are listed in the eBox.

eBOX. Contributors to the development of the guideline.

The following persons were responsible for the evidence-based revision of the guideline:

Dr. med. Karen Krüger, Dr. med. Sabine Gehrke-Beck, Dr. med. Felix Holzinger, Prof. Dr. med. Christoph Heintze, Dr. med. Janina Trauth, Dr. med. Myriam Koch, Dr. med. Peter Kardos, Prof. Dr. med. Jost Langhorst

The authors and collaborators of the guideline report were:

Dr. med. Karen Krüger, Dr. med. Sabine Gehrke-Beck, Dr. med. Felix Holzinger, Prof. Dr. med. Christoph Heintze

The following persons were involved in the consensus process:

Dr. med. Sabine Gehrke-Beck (German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians, DEGAM)

Prof. Dr. med. Christoph Heintze MPH, M.A. (German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians, DEGAM)

Dr. med. Janina Traut (German Society for Infectious Diseases, DGI)

Dr. med. Felix Holzinger MPH (German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians, DEGAM)

Dr. med. Karen Krüger (German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians, DEGAM)

Dr. med. Peter Kardos (German Respiratory Society, DGP)

Dr. med. Myriam Koch (German Respiratory Society, DGP)

Prof. Dr. med. Jost Langhorst (German Society for Phytotherapy, GPT)

Chair: Dr. rer. hum. Cathleen Muche-Borowski

Additional advisers included:

PD Dr. med. Guido Schmiemann, Prof. Dr. med. Thomas Kühlein

Results

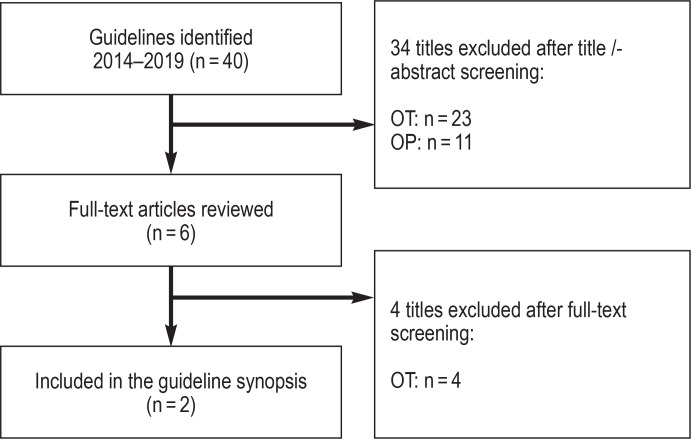

Seven source guidelines, 20 guidelines identified by the search of the guideline portals and 40 guidelines identified by the systematic search in Medline (via PubMed) were evaluated (efigure). A total of three guidelines of high methodological quality and relevance for the key questions were identified (2, 7, 8). An additional guideline was later included by consensus (6).

eFigure.

Flowchart for the systematic search for guidelines in Medline (via PubMed)

OT, other topic; OP, other publication type

The search for reviews and meta-analyses on unexplained or refractory cough carried out in Medline (via PubMed) yielded 16 hits; of these, two systematic reviews of high quality and relevance were included (etable). As the evidence base compiled from guidelines and reviews was adequate, no systematic search for original articles was performed.

eTable. Search strategy for PubMed.

| No. | Search term | Number |

| #1 | Search (treatment-resistant* or idiopathic* or intract* or refract* or unexplain* or idiopath*) and (cough*[Title/Abstract]) AND (Guideline[ptyp] OR Meta-Analysis[ptyp] OR systematic[sb]) AND „last 5 years“[PDat]) | 16 |

www.pubmed.org (18 June 2019)

The guideline recommendations cited below are stated with strength of recommendation and levels of evidence, while statements are accompanied by levels of evidence.

Guideline content and recommendations

Preventable high-risk disease courses and red flags

Identifying red flags during history-taking and examinations (figure) is crucial as a vital threat may be present or imminent. The following high-risk disease course must be identified or ruled out:

Left heart failure with cardiac asthma: Many of these patients have known cardiac disease and experience increasing signs and symptoms of backward heart failure, such as tachypnea and dyspnea on exertion, culminating in orthopnea with pulmonary congestion.

Neoplasms: Lung cancer is most common among smokers and may be associated with unintended weight loss, night sweats, hemoptysis, chest pain, and hoarseness.

Foreign body aspiration: If unnoticed, foreign body aspiration may cause prolonged cough and occasionally recurrent pneumonia, especially in children and the elderly.

Small recurrent pulmonary embolisms: Warning signs include exertional dyspnea and exercise intolerance, especially in patients with coagulation disorders and malignancies.

Consequently, the following evidence-based clinical management recommendations for chronic cough should only be followed after the red flags (figure) have been ruled out.

History, physical examination and consultation

According to the established nomenclature, chronic cough is defined as a cough that lasts more than eight weeks (statement, evidence level IV). If red flags are present in patients with subacute cough of three to eight weeks’ duration or if the cough is not associated with respiratory tract infection, a differential diagnostic work-up of causes of chronic cough is useful even before eight weeks have passed. Other distinctions, such as between productive and dry cough, are not relevant.

A systematic approach based on the medical history (table 1) and physical examination is useful. In the majority of cough-related consultations, an accurate diagnosis can be established in this way (9). Questioning about tobacco consumption (including e-cigarettes/nebulizer) is key (strength of recommendation A, level of evidence Ia), as tobacco use increases the likelihood of cough due to smoking and of cough due to tobacco-associated differential diagnoses, such as chronic (obstructive) bronchitis and lung cancer (2). Patient with a history of currently smoking should be motivated with personal relevance to stop smoking (A, Ia). After initial worsening, cough reduction can be expected within a few months. (10, 11). Cough is also more prevalent among patients smoking cannabis (12). Further questions to be asked include the long-term medication (especially ACE inhibitors [ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme]), allergies, present and past illnesses, as well as occupational and private exposures (8).

Table 1. Symptom-focused history in patients with chronic cough.

| Cardinal symptom: cough | ● Duration (>8 weeks) ● Start/trigger |

● Current triggers ● Sputum |

| Other symptoms | ● Dyspnea (on exertion) ● Pain: Chest, head, throat ● Reflux symptoms |

● Hypersensitivity: fragrances, cold ● Voice changes ● Cough while eating, drinking, lying down |

| Present and past illnesses | ● Previous infections ● Chronic diseases: bronchitis/ COPD, asthma, sinusitis ● Allergies ● Gastroesophageal reflux disease |

● Heart disease ● Status post surgery with intubation ● Pre-existing neurological conditions: aspiration possible? |

| Exposure | ● Smoking of tobacco/cannabis ● Occupational toxins ● Animal contact |

● Infections among close contacts ● History of migration and travel |

| Drugs | ● Cough-triggering: ACE inhibitors ● Bronchoconstrictive: β blockers |

● Prothrombotic: contraceptives ● Pulmonary toxicity: cytostatic agents, amiodarone |

| Patient-specific factors | ● Risk group for tuberculosis? ● Psychological situation: fear of cancer? |

● Vocally demanding profession ● Old age and frailty |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Besides inspection of the upper airways (nose, throat) and auscultation of the chest, the physical examination should pay attention to signs of respiratory insufficiency (increased respiratory rate, clammy, bluish skin) and decompensated heart failure (crackles on auscultation, leg edema). Targeted technical equipment-based investigations contribute to establishing the diagnosis in an additional almost one quarter of cases (13).

In an online survey on chronic cough with 1120 respondents from 29 European countries, nearly half of the patients reported that they had never received a diagnosis. Only one-third of the respondents thought they had been thoroughly examined, and fewer than 10% of patients reported relief from medication. More than 90% of the respondents frequently felt depressed and joyless due to the cough (4). Consequently, the aim should be to provide early patient-centered medical advice, addressing the most common causes of cough and the further diagnostic procedures.

Differential diagnosis, investigation and treatment

The steps of the clinical management of chronic cough are summarized in an algorithm (figure). The first step of the diagnostic work-up comprises a 2-view chest x-ray and pulmonary function tests (with provocation and allergy testing, if indicated) to rule out common diseases of the respiratory system, such as asthma and chronic (obstructive) bronchitis (2). If the patient is taking an ACE inhibitor and has a cough which is unlikely caused by an underlying pulmonary disease, the medication can be discontinued or the patient can be switched to another medication (e.g. an AT1 receptor blocker) prior to the chest x-ray; subsequently, the cough should subside completely within four weeks (14). If the chest x-ray shows a pulmonary mass or masses or if an underlying rare disease is suspected (table 2), the next step is either to obtain a chest CT scan or direct referral to an appropriate specialist.

Table 2. Relevant conditions in the differential diagnosis of chronic cough.

| Frequency | Bronchopulmonary causes | Extrapulmonary causes |

| Common | ● Chronic (obstructive) bronchitis ● Cough variant asthma ● Bronchial asthma |

● Upper airway cough syndrome ●G astroesophageal reflux disease |

| Uncommon | ● Bronchial/lung cancer (primary and secondary) ● Pertussis ● Eosinophilic bronchitis |

● Drugs (especially ACE inhibitors) ● Cough of unexplained origin ● Chronic left heart failure ● Vocal cord dysfunction |

| Rare | ● Infections: tuberculosis, opportunistic (immunosuppression) ● Tracheobronchial collapse ● Bronchiectasis ● Interstitial lung disease ● Cystic fibrosis |

● Hodgkin‘s lymphoma ● Esophageal diverticulum |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme

Which approach is chosen to treat chronic cough depends on the underlying disease. For the most common disease entities, such as asthma and COPD, pertinent guidelines are available (see 15, 16). If imaging studies and lung function testing are normal, other disease entities are likely to be present which are treated empirically and thus diagnosed secondarily, based on the alleviation of cough (figure). For example, after an infection a patient may develop cough variant asthma and experience persistent dry and nocturnal cough triggered by temperature changes, airway stimuli, laughter, and exercise. Cough variant asthma should be treated with an inhaled corticosteroid over a period of four weeks (B, Ib). However, while it usually takes several weeks for the cough to resolve, symptoms may improve in the first week of treatment (6). If the cough is not alleviated by the treatment, it is recommended to refer the patient to a pulmonologist. The differential diagnosis includes eosinophilic bronchitis, a condition which is also treated empirically in therapeutic trials.

In patients with chronic cough and concomitant symptoms characteristic of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), a therapeutic trial with a proton pump inhibitor ought to be made under the assumption that the cough is caused by GERD (B, Ib). In many cases, high-dose long-term treatment is required (17). Alleviation of the cough occurs after a few weeks at the earliest.

Chronic disorders of the upper respiratory tract, such as inflammatory nasal and sinus conditions as well as pharyngitis sicca, can trigger, or in some patients cause, an upper airway cough syndrome (18). If, based on clinical and/or radiographic findings, chronic rhinosinusitis is suspected to trigger such a cough syndrome, patients ought to be treated with nasal corticosteroids for at least six weeks (B, Ib). If the diagnosis is unclear or in refractory cases, it is recommended that the patient is seen by an office-based ENT specialist.

While approximately 10% of patients taking ACE inhibitors experience a dry, irritating cough (19), other substances may also cause chronic cough via various mechanisms, although at much lower rates. Examples include antiarrhythmic agents, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, anti-infective agents, methotrexate, tricyclic antidepressants, and cholinesterase inhibitors (20).

Unexplained or refractory chronic cough

An unexplained cough is present if, despite a structured approach, no cause can be determined (8). If treatment of one or more suspected causes has been unsuccessful, the cough is classified as refractory. Since the above mentioned empirical treatment attempts are part of the standard diagnostic strategies, a clear distinction cannot always be made. The proportion of unexplained or refractory cases in specialized outpatient clinics varies widely, with reports ranging from 0 to 46% (21). No data are available for the primary care setting. It is common that patients with unexplained or refractory cough report high levels of psychological distress, are more frequently nervous and show symptoms of depression (22, 23). Their suffering can be severe. Middle-aged women are especially vulnerable as they are more commonly affected by both chronic cough with resulting distress (e.g. increased levels of stress incontinence due to the cough) and comorbidities such as depression (24).

One of the suspected causes is increased cough reflex sensitivity following an initial trigger, such as an infection. In addition, cough may represent a distinct disease entity that is diagnosed clinically. Before that, patients with chronic cough should be evaluated according to an established diagnostic algorithm in collaboration with specialists. During the process, empirical treatments should be tested exhaustively in accordance with the guidelines, and the possibility of multiple causes as well as the role of patient compliance should be considered (A, V). A pragmatic checklist has been developed in the updated guideline to support the implementation of this recommendation in everyday clinical practice (box).

BOX. Checklist for unexplained or refractory cough.

Have all conditions in the differential diagnosis, including investigations, been addressed?

Re-evaluation of medications for potential to cause dry, irritating cough

Multi-factorial approach: Are there multiple causes acting together?

In case of refractory suspected diagnosis: Treatment optimization?

Patient compliance with present drugs/treatments?

Psychological causes, such as tics?

Documentation: e.g. using the Hull Cough Hypersensitivity questionnaire

Regular follow-up

Consider referral to pulmonologist and/or ENT specialist

History of vocal strain

Treatment options include pharmacotherapy (mainly off-label treatments) as well as physiotherapeutic or speech-therapeutic methods. Patients can already be educated about basic cough suppression techniques during the medical consultation (table 3).

Table 3. Management options for unexplained or refractory cough.

| Patient education and self-management | ||

| ● Reassure: No serious underlying organ disease is found upon thorough investigation. ● Increased cough reflex sensitivity: An event (e.g. infection) triggers “hypersensitivity“, resulting in unnecessary coughing. ● Triggers: dry air, smoke or other irritants ● Basic methods for cough suppression: such as distraction, candies, chewing gum ● Measures for mucosal humidification: unobstructed nasal breathing, adequate fluid intake, inhalation | ||

| Non-pharmacological treatments | ||

| Treatment modalities | Side effects/ special features | State of the evidence |

| ● Physiotherapy: Techniques for cough suppression and breathing exercises, prescription of breathing therapy, indication group AT1a/AT2a ● Speech therapy: Voice therapy for compulsive coughing/throat clearing, prescription: “functional voice disorder“ Indication group ST2 |

● None ● Limited availability of qualified therapists! |

● Two controlled studies with small sample sizes ● Further treatment optimization and lasting effects in controlled trials in combination with pharmaceutical agents |

| Drug treatments | ||

| ● Morphine, sustained release: 5–10 mg orally 1–2x daily ● Gabapentin orally: Start: E.g., 1 x 300 mg daily; then up-dosing guided by individual response/side effects up to 1800 mg daily |

● Opioids: respiratory depression, constipation, dependence – however, moderate side effect profile in the low-dose range! ● Gabapentin: dizziness, confusion, vision changes, dry mouth |

● Several controlled trials with small sample sizes ● Proven effectiveness of morphine in the low-dose range ● No sustained effect after discontinuation ● Off-label use of both active substances! |

Following consultation and patient education, nonpharmacological management strategies, such as physiotherapeutic or speech-therapeutic methods, are trained in two to four sessions, including exercises and postures which help to suppress an increased urge to cough and reduce compulsive throat clearing (25). Given the few controlled studies with small sample sizes, the available evidence is limited. The most commonly used instrument in studies on cough is the Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ) which defines an improvement by 1.3 points as a clinically relevant change (26). One of the two available randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the nonpharmacological treatment of cough showed a clinically significant LCQ score improvement for cough symptoms (mean difference: 1.53 points; 95% confidence interval [0.21; 2.85]; p = 0.024) (25). The other trial also demonstrated an improvement, based on a less established score (27). Overall, this treatment strategy requires a limited effort with few treatment sessions and the level of patient safety is high. Thus, in adult patients with unexplained or refractory chronic cough associated with high levels of symptom-related distress, speech therapy or physiotherapy (primarily respiratory physiotherapy) may be offered (0, V). This can be received alongside drug treatment for unexplained or refractory cough (0, V).

Drug treatment options with proven efficacy include only agents for off-label therapeutic trials (table 3). Based on the currently available study data, long-term improvements after discontinuation of these substances are unlikely to be seen.

In the included guidelines and systematic reviews, studies with the active ingredients gabapentin, pregabalin, morphine, amitriptyline, erythromycin, azithromycin, tramadol, and various receptor antagonists (NMDA, TRPV1, P2X3, NK1) were analyzed with regard to their effectiveness in treating chronic cough (2, 6, 9, 28, 29). In most of the underlying controlled trials, the sample size was small. In these studies, the substances morphine, gabapentin and pregabalin showed clinically relevant effectiveness in treating chronic cough.

In some of the patients, opioids can alleviate chronic cough, starting from a dose of 5 mg morphine per day (6, 8, 29). In a frequently cited RCT (30), responders had a rapid onset of action, with the maximum benefit being seen on day five (improved LCQ score, mean difference: 2 points [0.93; 3.07]; p = 0.02). In patients with subtherapeutic response, the dose was increased to 10 mg twice daily, resulting in a further decrease in cough severity, but also an increased occurrence of sleepiness. In the low-dose range used here, the risk of serious side effects is considered to be comparatively low (6).

Gabapentin has a favorable side-effect profile with regard to tolerance development and addiction potential. Furthermore, its efficacy and safety has been evaluated extensively in trials (8, 31). Two RCTs included in a review without meta-analysis (28) showed a clinically significant LCQ score improvement in patients treated with gabapentin compared to placebo within a period of eight weeks, with maximum daily doses of up to 1800 mg (improved LCQ score, mean difference: 1.8 points [0.56; 3.04], p = 0.004, number needed to treat [NNT]: 3.6) (32). Side effects (table 3) were dose-dependent and occurred in 31–40% of patients in the intervention group and in 10–23% in the placebo group (28).

Pregabalin is a related substance, but because it can produce feelings of euphoria and relaxation, misuse is common (29, 33). Adverse events, such as blurred vision, cognitive changes, dizziness or weight gain, were reported by 75% of subjects. At the same time, the rate of placebo effects was comparatively high. On the other hand, studies evaluating pregabalin showed that in combination with speech therapy it helped to optimize the treatment of chronic cough (improved LCQ score versus placebo plus speech therapy; mean difference: 3.5 points [1.11; 5.89]; p = 0.024, NNT: 20). The sustained effectiveness noted after discontinuation of pregabalin was attributed to speech therapy (34).

Codeine and noscapine can be prescribed for the treatment of cough, but have not been systematically evaluated in patients with refractory cough. Given its side-effect profile and the inter-individual genetic variability in the breakdown (CYP2D6) of the substance to morphine and the thus difficult to control response to treatment, codeine is not recommended.

In summary, patients with unexplained or refractory cough associated with high levels of distress can be offered at their request treatment with gabapentin or low-dose morphine after comprehensive discussion of potential side effects (0, Ia).

There is still little experience with novel drugs such as gefapixant, a P2X3 receptor antagonist. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 2b trial showed comparatively high placebo effects in patients with chronic cough. Dysgeusia was the most relevant side effect (35).

Need for research

The update of the guideline resulted in the following additional research questions:

What relevant comorbidities are associated with chronic cough?

What is the age- and sex-dependent incidence of unexplained or refractory cough in the primary care setting in Germany?

What are the long-term effects of speech-therapeutic and physiotherapeutic treatments in patients with chronic cough, and what duration/intensity of treatment is required to achieve an effect?

What long-term effects (sustained symptom relief, patient compliance, side effects, habituation effects, quality of life) are associated with pharmacological treatments for unexplained or refractory cough?

Supplementary Material

eMethods

Systematic guideline search

During the update of the original version of the 2014 AWMF S3-level guideline (AWMF register no. 053–013), a systematic search for new source guidelines was performed. The search was limited to clinical guidelines in English and German.

Search for updates of source guidelines of the original version

First, the source guidelines (n = 7) mentioned in the original 2014 guideline version were evaluated for up-to-dateness. The inclusion criterion regarding up-to-dateness was defined as a publication date of less than five years to the date of the updating systematic search, i.e. 25 June 2018.

Search in guideline portals

Furthermore, a search with the search terms “cough“ / “Husten“ + publication year: 2014 to 2019 was carried out in the following guideline portals:

Search in databases

An additional search in Medline via PubMed (www.pubmed.org) was performed using the following search strategy (flowchart in the eFigure):

Search strategy for PubMed (www.pubmed.org), accessed on 28 June 2018:

Search (guideline*[TI] OR recommendation*[TI] OR consensus[TI] OR standard*[TI] OR „position paper“ [TI] OR „clinical pathway*“ [TI] OR „clinical protocol*“ [TI] OR „good clinical practice“ [TI]) AND (cough [TI])”last 5 years”[PDat]

Included source guidelines

The search in guideline portals and databases identified three evidence-based clinical guidelines:

After completion of the systematic search, one further evidence-based guideline was included by consensus in the group of authors, due to its up-to-dateness and topical relevance:

Evaluation of the methodological quality of the source guidelines included

The methodological quality of the source guidelines identified was evaluated by two authors of the guideline report (5), using the AGREE II instrument (36). An overall rating of == 50% was defined as the cut-off value for inclusion of the guidelines as source guidelines. The complete guideline synopsis is available in Appendix A of the Guideline Report (5).

Systematic search for systematic reviews

For the update of the original version of the guideline, a systematic search for systematic reviews on unexplained and refractory cough (UCC) was performed in Medline via PubMed (etable). Given a satisfactory guideline search, we only searched for the treatment of UCC in the past five years (18 June 2014 to 18 June 2019).

PICO(S) process used:

Evaluation of the methodological quality of the systematic reviews included

The methodological quality of the systematic reviews identified was evaluated by two authors of the guideline report, using the AMSTAR-2 instrument (37). The 16 questions of AMSTAR-2 regarding methodological quality were answered with “yes“, “partial yes“ or “no“/ “not applicable“. A cut-off value of at least eight „yes“ or „partial yes“ was set for the inclusion of a systematic review. With this approach, a total of two systematic reviews were included in the synthesis. The complete evidence tables are available in Appendix B of the guideline report of the S3-level Clinical Practice Guideline on Acute and Chronic Cough (5).

Coding of the grade of recommendation, level of evidence and consensus

The recommendation of this guideline were systematically evaluated based on the quality of the underlying studies. Roman numerals (I-V) inserted in parentheses in the text indicate the level of evidence based on the study design. For simplification and a better overview, levels of „grade of recommendation“ (A = should, B = ought to, 0 = may) are derived from this. Evidence levels were coded according to the Oxford evidence grading system (2009 version, available at www.cebm.net).

In the consensus conference, six statements und ten recommendations could be adopted unanimously, while three guideline recommendations had one abstention. The voting results can be viewed in the long version of the updated guideline (5).

Literature search on patient perspective

In order to obtain insight into the perspective of patients with chronic cough, a systematic literature search was conducted on this topic. The search in the databases Medline (via PubMed) and Embase identified 7361 articles which were reduced to 13 articles after duplicate, full-text and abstract screening as well as evaluation of methodological quality (AMSTAR-2) (5). The contents of the studies evaluated were included in the free text of the guideline at the appropriate place for the respective chapter.

National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC)

Guidelines International Network (GIN)

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

New Zealand Guidelines Group (NZGG)

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC)

American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST)

European Respiratory Society (ERS)

British Thoracic Society (BTS)

Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF)

Leitlinien.de of the German Agency for Quality in Medicine (ÄZQ, Ärztliche Zentrum für Qualität in der Medizin) under the joint sponsorship of the German Medical Association (Bundesärztekammer) and the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung)

Drug Commission of the German Medical Association (AkdÄ, Arzneimittelkommission der deutschen Ärzteschaft)

Gibson P, et al.: Treatment of unexplained chronic cough: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2016 (8).

Irwin RS, et al.: Classification of cough as a symptom in adults and management algorithms: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2018 (2).

Malesker MA, et al.: Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment for acute cough associated with the common cold. CHEST Expert Panel Report 2017 (7).

Morice AH, et al.: ERS guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in adults and children. European Respiratory Journal 2020 (6).

Population: adult patients with chronic cough

Intervention: no restrictions

Comparison: no restrictions

Study type: systematic reviews and guidelines

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ralf Thoene, MD.

Clinical guidelines are not peer-reviewed in the Deutsche Ärzteblatt, as well as in many other journals, because clinical (S3-level) guidelines are texts which have already been repeatedly evaluated, discussed and broadly consented by experts (peers).

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank all other authors and stakeholders of the DEGAM S3-level Clinical Practice Guideline on Acute and Chronic Cough: Prof. Dr. med. Jost Langhorst, Dr. med. Peter Kardos, PD Dr. med. Guido Schmiemann, Prof. Dr. med. Thomas Kühlein, Dr. rer. hum. Cathleen Muche-Borowski

Financial support

The guideline was financed by DEGAM’s own funds as well as funds of the Institute of General Practice and Family Medicine, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Heuer J, Kerek-Bodden H, Koch DH. Die 50 häufigsten ICD-10-Schlüsselnummern nach Fachgruppen. Zentralinstitut für die kassenärztliche Versorgung (Zi) 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irwin RS, French CL, Chang AB, Altman KW. CHEST Expert Cough Panel: Classification of cough as a symptom in adults and management algorithms: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2018;153:196–209. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song WJ, Chang YS, Faruqi S, et al. The global epidemiology of chronic cough in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:1479–1481. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00218714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chamberlain SA, Garrod R, Douiri A, et al. The impact of chronic cough: a cross-sectional European survey. Lung. 2015;193:401–408. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9701-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krüger K, Holzinger F, Heintze C, Gehrke-Beck S. DEGAM S3-Leitlinie Nr 11: Akuter und chronischer Husten AWMF-Register-Nr. 053-013. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/053-013l_S3_akuter-und-chronischer-Husten_2021-06.pdf (last accessed on 14 November 2021) 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morice AH, Millqvist E, Bieksiene K, et al. ERS guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in adults and children. Eur Respir J. 2020;55 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01136-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malesker MA, Callahan-Lyon P, Ireland B, et al. Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment for acute cough associated with the common cold: CHEST Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2017;152:1021–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibson P, Wang G, McGarvey L, et al. Treatment of unexplained chronic cough: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149:27–44. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gehrke-Beck S, Holzinger F. Abklärung und Behandlung von chronischem und refraktärem Husten. AVP. 2017;44:2–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kardos P, Dinh QT, Fuchs K-H, et al. Leitlinie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Pneumologie und Beatmungsmedizin zur Diagnostik und Therapie von erwachsenen Patienten mit Husten. Pneumologie. 2019;73:143–180. doi: 10.1055/a-0808-7409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andreas S, Batra A, Behr J, et al. Tabakentwöhnung bei COPD. Pneumologie. 2014;68:237–258. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ribeiro LI, Ind PW. Effect of cannabis smoking on lung function and respiratory symptoms: a structured literature review. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2016;26:1–8. doi: 10.1038/npjpcrm.2016.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalal B, Geraci SA. Office management of the patient with chronic cough. Am J Med. 2011;124:206–209. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dicpinigaitis PV. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced cough: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129:169S–173S. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.169S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bundesärztekammer (BÄK), Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Asthma - Langfassung, 4. Auflage. Version 1. www.leitlinien.de/themen/asthma/pdf/asthma-4aufl-vers1-lang.pdf (last accessed on 14 November 2021) 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bundesärztekammer (BÄK), Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie COPD - Teilpublikation der Langfassung, 2. Auflage. Version 1. www.kbv.de/media/sp/copd-2aufl-vers1.pdf (last accessed on 14 November 2021) 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Irwin RS. Chronic cough due to gastroesophageal reflux disease: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129:80S–94S. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.80S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu L, Xu X, Lv H, Qiu Z. Advances in upper airway cough syndrome. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2015;31:223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vukadinović D, Vukadinović AN, Lavall D, Laufs U, Wagenpfeil S, Böhm M. Rate of cough during treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;105:652–660. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ukena D. Drug-induced pulmonary diseases. Pneumologe (Berl) 2007;4:201–212. doi: 10.1007/s10405-007-0149-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung KF, Pavord ID. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and causes of chronic cough. Lancet. 2008;371:1364–1374. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birring SS. Controversies in the evaluation and management of chronic cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:708–715. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201007-1017CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hulme K, Deary V, Dogan S, Parker SM. Psychological profile of individuals presenting with chronic cough. ERJ Open Res. 2017;3:00099–02016. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00099-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young EC, Smith JA. Quality of life in patients with chronic cough. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2010;4:49–55. doi: 10.1177/1753465809358249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chamberlain S, Birring SS, Garrod R. Nonpharmacological interventions for refractory chronic cough patients: systematic review. Lung. 2014;192:75–85. doi: 10.1007/s00408-013-9508-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmit KM, Coeytaux RR, Goode AP, et al. Evaluating cough assessment tools: a systematic review. Chest. 2013;144:1819–1826. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vertigan AE, Theodoros DG, Gibson PG, Winkworth AL. Efficacy of speech pathology management for chronic cough: a randomised placebo controlled trial of treatment efficacy. Thorax. 2006;61:1065–1069. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.064337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi G, Shen Q, Zhang C, Ma J, Mohammed A, Zhao H. Efficacy and safety of Gabapentin in the treatment of chronic cough: a systematic review. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2018;81:167–174. doi: 10.4046/trd.2017.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryan NM, Vertigan AE, Birring SS. An update and systematic review on drug therapies for the treatment of refractory chronic cough. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19:687–711. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2018.1462795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morice AH, Menon MS, Mulrennan SA, et al. Opiate therapy in chronic cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:312–315. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-892OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi G, Shen Q, Zhang C, Ma J, Mohammed A, Zhao H. Efficacy and safety of Gabapentin in the treatment of chronic cough: a systematic review. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2018;81:167–174. doi: 10.4046/trd.2017.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryan NM, Birring SS, Gibson PG. Gabapentin for refractory chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:1583–1589. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60776-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Köberle U, Stammschulte T, Acquarone D, Bonnet U. Abhängigkeitspotenzial von Pregabalin. Arzneiverordnung in der Praxis. 2020;47:62–65. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vertigan AE, Kapela SL, Ryan NM, Birring SS, McElduff P, Gibson PG. Pregabalin and speech pathology combination therapy for refractory chronic cough: a randomized controlled trial. Chest. 2016;149:639–648. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith JA, Kitt MM, Morice AH, et al. Gefapixant, a P2X3 receptor antagonist, for the treatment of refractory or unexplained chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, controlled, parallel-group, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:775–785. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30471-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1308–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Systematic guideline search

During the update of the original version of the 2014 AWMF S3-level guideline (AWMF register no. 053–013), a systematic search for new source guidelines was performed. The search was limited to clinical guidelines in English and German.

Search for updates of source guidelines of the original version

First, the source guidelines (n = 7) mentioned in the original 2014 guideline version were evaluated for up-to-dateness. The inclusion criterion regarding up-to-dateness was defined as a publication date of less than five years to the date of the updating systematic search, i.e. 25 June 2018.

Search in guideline portals

Furthermore, a search with the search terms “cough“ / “Husten“ + publication year: 2014 to 2019 was carried out in the following guideline portals:

Search in databases

An additional search in Medline via PubMed (www.pubmed.org) was performed using the following search strategy (flowchart in the eFigure):

Search strategy for PubMed (www.pubmed.org), accessed on 28 June 2018:

Search (guideline*[TI] OR recommendation*[TI] OR consensus[TI] OR standard*[TI] OR „position paper“ [TI] OR „clinical pathway*“ [TI] OR „clinical protocol*“ [TI] OR „good clinical practice“ [TI]) AND (cough [TI])”last 5 years”[PDat]

Included source guidelines

The search in guideline portals and databases identified three evidence-based clinical guidelines:

After completion of the systematic search, one further evidence-based guideline was included by consensus in the group of authors, due to its up-to-dateness and topical relevance:

Evaluation of the methodological quality of the source guidelines included

The methodological quality of the source guidelines identified was evaluated by two authors of the guideline report (5), using the AGREE II instrument (36). An overall rating of == 50% was defined as the cut-off value for inclusion of the guidelines as source guidelines. The complete guideline synopsis is available in Appendix A of the Guideline Report (5).

Systematic search for systematic reviews

For the update of the original version of the guideline, a systematic search for systematic reviews on unexplained and refractory cough (UCC) was performed in Medline via PubMed (etable). Given a satisfactory guideline search, we only searched for the treatment of UCC in the past five years (18 June 2014 to 18 June 2019).

PICO(S) process used:

Evaluation of the methodological quality of the systematic reviews included

The methodological quality of the systematic reviews identified was evaluated by two authors of the guideline report, using the AMSTAR-2 instrument (37). The 16 questions of AMSTAR-2 regarding methodological quality were answered with “yes“, “partial yes“ or “no“/ “not applicable“. A cut-off value of at least eight „yes“ or „partial yes“ was set for the inclusion of a systematic review. With this approach, a total of two systematic reviews were included in the synthesis. The complete evidence tables are available in Appendix B of the guideline report of the S3-level Clinical Practice Guideline on Acute and Chronic Cough (5).

Coding of the grade of recommendation, level of evidence and consensus

The recommendation of this guideline were systematically evaluated based on the quality of the underlying studies. Roman numerals (I-V) inserted in parentheses in the text indicate the level of evidence based on the study design. For simplification and a better overview, levels of „grade of recommendation“ (A = should, B = ought to, 0 = may) are derived from this. Evidence levels were coded according to the Oxford evidence grading system (2009 version, available at www.cebm.net).

In the consensus conference, six statements und ten recommendations could be adopted unanimously, while three guideline recommendations had one abstention. The voting results can be viewed in the long version of the updated guideline (5).

Literature search on patient perspective

In order to obtain insight into the perspective of patients with chronic cough, a systematic literature search was conducted on this topic. The search in the databases Medline (via PubMed) and Embase identified 7361 articles which were reduced to 13 articles after duplicate, full-text and abstract screening as well as evaluation of methodological quality (AMSTAR-2) (5). The contents of the studies evaluated were included in the free text of the guideline at the appropriate place for the respective chapter.

National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC)

Guidelines International Network (GIN)

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

New Zealand Guidelines Group (NZGG)

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC)

American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST)

European Respiratory Society (ERS)

British Thoracic Society (BTS)

Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF)

Leitlinien.de of the German Agency for Quality in Medicine (ÄZQ, Ärztliche Zentrum für Qualität in der Medizin) under the joint sponsorship of the German Medical Association (Bundesärztekammer) and the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung)

Drug Commission of the German Medical Association (AkdÄ, Arzneimittelkommission der deutschen Ärzteschaft)

Gibson P, et al.: Treatment of unexplained chronic cough: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2016 (8).

Irwin RS, et al.: Classification of cough as a symptom in adults and management algorithms: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2018 (2).

Malesker MA, et al.: Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment for acute cough associated with the common cold. CHEST Expert Panel Report 2017 (7).

Morice AH, et al.: ERS guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in adults and children. European Respiratory Journal 2020 (6).

Population: adult patients with chronic cough

Intervention: no restrictions

Comparison: no restrictions

Study type: systematic reviews and guidelines