Abstract

The basic treatment of leishmaniasis consists in the administration of pentavalent antimonials. The mechanisms that contribute to pentavalent antimonial toxicity against the intracellular stage of the parasite (i.e., amastigote) are still unknown. In this study, the combined use of several techniques including DNA fragmentation assay and in situ and cytofluorometry terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling methods and YOPRO-1 staining allowed us to demonstrate that potassium antimonyl tartrate, an Sb(III)-containing drug, was able to induce cell death associated with DNA fragmentation in axenic amastigotes of Leishmania infantum at low concentrations (10 μg/ml). This observation was in close correlation with the toxicity of Sb(III) species against axenic amastigotes (50% inhibitory concentration of 4.75 μg/ml). Despite some similarities to apoptosis, nuclease activation was not a consequence of caspase-1, caspase-3, calpain, cysteine protease, or proteasome activation. Altogether, our results demonstrate that the antileishmanial toxicity of Sb(III) antimonials is associated with parasite oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation, indicative of the occurrence of late events in the overall process of apoptosis. The elucidation of the biochemical pathways leading to cell death could allow the isolation of new therapeutic targets.

Leishmaniasis is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in several countries. A vertebrate host is infected with flagellated extracellular promastigote forms via the bite of a sand fly. Promastigotes are rapidly transformed into nonflagellated amastigotes dividing actively within the mononuclear phagocytes of the vertebrate host. The basic treatment consists in the administration of sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam), meglumine (Glucantime), pentamidine, or amphotericin B. Treatment failure, especially for kala-azar, mucosal leishmaniasis, and diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis is becoming a common problem in many areas where leishmaniasis is endemic. Immunological, physiological, or pharmacological deficiencies in the host are possible explanations for variations in clinical response (29). But there is evidence that inherent lack of susceptibility and (or) the development of resistance can also contribute to parasite unresponsiveness to drugs (13, 18, 23, 28, 39, 40). The mode of action of pentavalent antimonials remains poorly understood (3, 4, 5). An in vivo metabolic conversion of pentavalent antimonial [Sb(V)] into trivalent ones [Sb(III)] was suggested more than 50 years ago by Goodwin and Page (15, 16). This hypothesis was supported by the high toxicity of trivalent antimony against both parasite stages of different Leishmania species (10, 14, 26, 31, 34). Recently, we and other investigators have shown that axenically grown amastigotes of Leishmania represent a powerful model to investigate drug activity on the active and dividing population of the mammalian parasite stage (7, 34). We have shown that potassium antimonyl tartrate [containing Sb(III)] was generally more toxic than pentavalent antimony [Sb(V)] for both parasite stages of different Leishmania species and demonstrated that the extracellular amastigotes of Leishmania infantum were the Leishmania species most susceptible to Sb(III) (35). Moreover, in vitro-selected Sb(III)-resistant axenic amastigotes expressed a strong cross-resistance to meglumine when growing in THP-1 cells (37). A stage-specific susceptibility of amastigotes towards antimonials has also been proposed. This hypothesis is based on the assumption that amastigotes of Leishmania donovani are able to reduce pentavalent antimonial into a trivalent one (11, 12).

There are now increasing numbers of reports of single-celled organisms that kill themselves by a mechanism whose activation is not obligatory but can be used in threatening situations (i.e., apoptosis) (2). Drugs, toxins, and physical injuries could also provoke apoptosis in mammalian cells (1, 9, 41). Interestingly, arsenite-mediated apoptosis has been characterized and extensively studied in mammalian cells (8, 20, 24, 43, 44). As antimonials share several chemical properties with arsenicals, trivalent antimonial-mediated apoptosis has been studied and reported in NB4 and NB4R4 cells (27). In order to more precisely clarify the mode of action of antimonials against the amastigote forms of L. infantum, we have investigated the type of cell death induced by antimonials.

In this study, we demonstrate that the cell death mediated by antimonials presents some features previously shown to be induced by heat shock in the promastigote forms of Leishmania amazonensis (25), by antibiotic G418 in the epimastigote forms of Trypanosoma cruzi (1), and by reactive oxygen species in Trypanosoma brucei (30, 45). Trivalent antimonials (tartar emetic) species were able to kill amastigotes with a cell death phenotype presenting some homologies with the programmed cell death observed in metazoans (i.e., DNA fragmentation). The term apoptosis, which was originally defined purely on morphological grounds, has been recently redefined as “caspase-mediated cell death with associated apoptotic morphology” (32, 42). Our study suggests that nuclease activation does not depend on caspase-1, caspase-3, calpain, cystein protease, or proteasome activation. These results suggest that the cell death pathway involved in antimonial toxicity should be different from those involved in metazoan apoptosis. The implication of these observations on the antimonial mode of action is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Meglumine (Glucantime, batch no. 331-2, which does not contain m-chlorocresol as preservative) was supplied by Rhône Poulenc Specia. Z-DEVD-CMK, Z-VAD-FMK, calpain I inhibitor, E-64 (2S,3S)-trans-epoxy-epoxysuccinyl-l-leucylamido-3-methylbutane ethyl ester, lactacystin, potassium antimonyl tartrate trihydrate, geneticin, and amphotericin B were supplied from Sigma.

Parasites and cultures.

A cloned line of L. infantum (MHOM/MA/67/ITMAP-263) was used in all experiments. Axenically grown amastigote forms of L. infantum were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 by weekly subpassages in a cell-free medium called MAA/20 (medium for axenically grown amastigotes) in 25-cm2 flasks as previously described (25, 26, 43, 44). From a starting inoculum of 5 × 105 amastigote forms/ml, cell density of about 5 × 107 parasites/ml was obtained on day 7. MAA/20 consisted of modified medium 199 (Gibco BRL) with Hanks' balanced salt solution supplemented with 0.5% soy trypto-casein (Pasteur Diagnostics, Marne la Coquette, France), 0.01 mM bathocuproine disulphonic acid, 3 mM l-cysteine, 15 mM d-glucose, 5 mM l-glutamine, 4 mM NaHCO3, 0.023 mM bovine hemin, and 25 mM HEPES to a final pH of 6.5 and supplemented by 20% pretested fetal calf serum (21, 22, 33, 36).

Selection of antimonyl Sb(III)-resistant amastigote forms.

Cloned wild-type amastigote forms of L. infantum (designated as LdiWT) were subjected to stepwise-increasing drug pressure until cell lines resistant to 120 μg of potassium antimonyl tartrate trihydrate per ml were established. Fifty-percent-inhibitory concentrations were determined using the micromethod previously described (34, 35, 37). All amastigote populations [wild-type and Sb(III)-resistant clones] were subjected to similar in vitro culture subpassages.

In situ TUNEL assay.

DNA fragmentation was analyzed in situ using a colorimetric detection system (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Slides containing treated and untreated infected macrophages and axenic amastigotes were fixed for 20 min with formaldehyde (4%; Sigma), washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (0.01 M, pH 7.2), and stored at −20°C until used. The terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) protocol involved a 10-min preincubation period with terminal transferase (TdT) buffer. The reaction was carried out in a 50-μl final volume with terminal transferase (0.5 μl) and biotinylated dUTP (0.5 μl) in 1× TdT buffer containing CoCl2. After 60 min of incubation at 37°C in humidified chambers, slides were washed with 0.01 M PBS, pH 7.2, and the reaction was stopped by incubation of the slides in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) for 15 min. The endogenous peroxidase was blocked by incubation of the slides in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 5 min. After being washed, the slides were incubated for 30 min in a solution of streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (1/500). Then peroxidase activity was revealed using the peroxidase substrate (hydrogen peroxide) and the chromogen diaminobenzidine. After an extensive washing in PBS, the preparations were analyzed using a microscope at a magnification of ×1,000. Apoptotic nuclei were visualized and appeared dark brown.

Flow cytofluorometry analysis using TUNEL assay.

DNA fragmentation was analyzed by cytofluorometry using the apoptosis detection system (Promega). Briefly, 3 × 106 to 5 × 106 axenic amastigotes were washed twice with PBS (0.01 M) and fixed with methanol-free formaldehyde (1%) for 20 min at 4°C followed by 70% ethanol, which makes cells permeable in the TUNEL procedure. The fixed cells were washed with TdT buffer and incubated in the presence of terminal transferase (0.5 μl) and biotinylated dUTP (0.5 μl) in TdT buffer containing CoCl2. After 30 min of incubation at 37°C, the biotin-labeled cells were stained with avidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate. The DNA was stained with 1 μg of propidium iodide per ml before analysis on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Ivry, France).

Flow cytofluorometry analysis using YOPRO-1.

The percentage of apoptotic cells was quantitated by flow cytofluorometry analysis using the impermeant DNA intercalating YOPRO-1 (YP) as previously described (19). Briefly, 106 L. infantum axenic amastigotes were incubated with 10 μM YP for 10 min. Cells were immediately analyzed on the FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) using an argon-ion laser tuned to 488 nm. Green cell fluorescence, gated on forward and side-light scatter, was collected using a band-pass filter (525 ± 10 nm) and displayed using a logarithmic amplification (FL-1).

DNA agarose gel electrophoresis.

Qualitative analysis of DNA fragmentation was performed as previously described (1) by agarose gel electrophoresis of DNA extracted from 5 × 108 amastigotes. Cell pellets were incubated in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, pH 7.4) for 30 min at 4°C. The mixture was then submitted to proteolysis (proteinase K, 20-μg/ml final concentration; Boehringer Mannheim) for 2 h at 50°C, and lysates were centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. DNA from supernatants, purified by the phenol-chloroform extraction method, was precipitated in the presence of 0.5 M NaCl (final concentration) and 1 volume of isopropanol. After a washing by 70% ethanol, DNA was air dried and dissolved in 10 μl of distilled water and 10 μg of DNA from Sb(III)-treated and untreated parasites was electrophoresed in the presence of 1 μl of migration buffer (40 mM Tris, 20 mM sodium acetate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.5 [Tris-borate-EDTA], 50% glycerol) on a 2% agarose gel in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer for 2 h at 100 V. DNA was then visualized under UV light after gel staining with ethidium bromide.

RESULTS

Antimonial-mediated DNA fragmentation on axenic amastigotes of L. infantum.

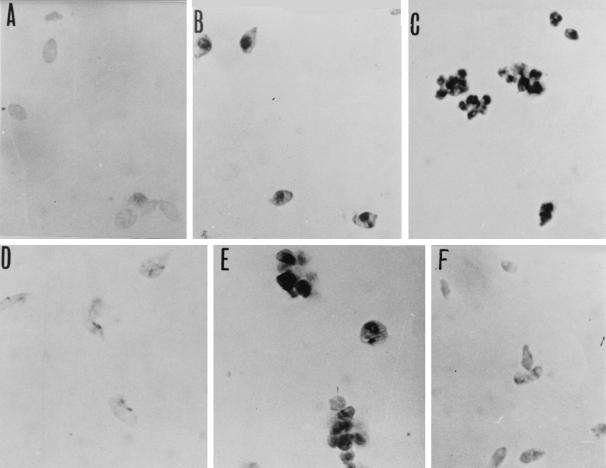

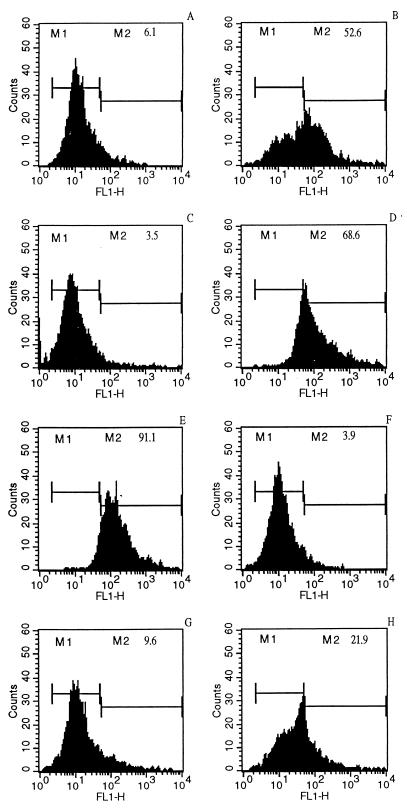

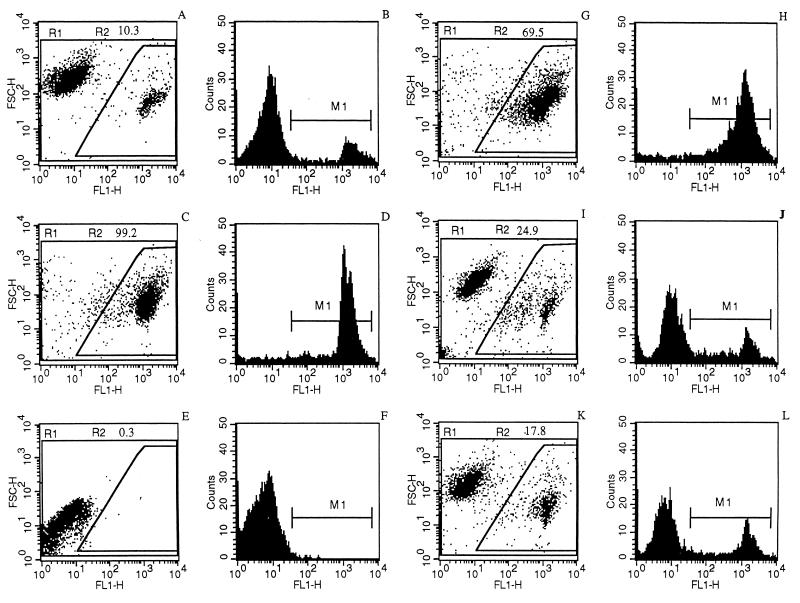

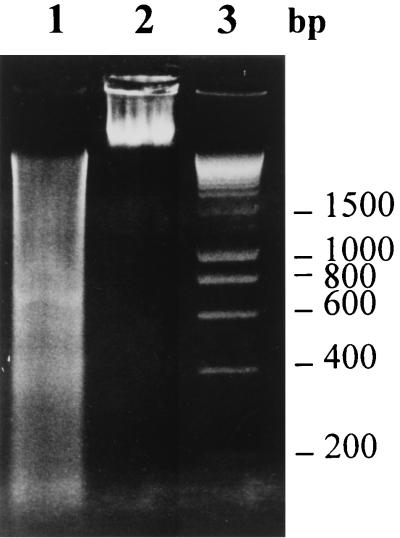

When LdiWT axenic amastigotes were treated with 10 μg of trivalent antimonials per ml for 24 h (50% inhibitory concentration after 3 days, about 4.75 μg/ml), DNA fragmentation could be detected via the evaluation of endonuclease activity, by using the TUNEL method (Fig. 1C), compared to control untreated parasites, for which DNA fragmentation was not detected (Fig. 1A). Nuclei of Sb(III)-treated parasites were stained dark brown as observed with positive control (Fig. 1B). Geneticin was also able to promote DNA fragmentation on axenic amastigotes of L. infantum at a concentration of 1 mg/ml (Fig. 1E). By contrast, nuclei of the chemoresistant mutants (LdiR120) treated with 50 μg of Sb(III) antimonials per ml were not labeled by the TUNEL technique (Fig. 1F) like the nuclei of wild-type parasites treated with 160 mg of meglumine Sb(V) (Fig. 1D). These results were confirmed using the flow cytometry TUNEL assay. First, geneticin at a concentration of 2 mg/ml induced apoptosis-like changes as shown by the increase in yellow-green fluorescence intensity gated on FL1 (Fig. 2B), unlike what is seen for the untreated cells (Fig. 2A). The specificity of the reaction was monitored by performing a negative control on the geneticin-treated amastigotes (Fig. 2C). Wild-type amastigotes incubated in the presence of 10 or 50 μg of Sb(III) per ml expressed a large increase in the FL1 fluorescence (Fig. 2D and E) compared to the untreated control (Fig. 2A). LdiR120 mutants treated with 50 μg of Sb(III) per ml showed only a slight increase in FL1 fluorescence compared to untreated parasites LdiR120 (Fig. 2G and H). These results strongly suggest that trivalent antimonials were able to readily induce DNA fragmentation on the clinically relevant stage of the parasite. To confirm this observation, a YOPRO-1 staining method was used to monitor the Sb(III)-mediated cell death. YOPRO-1 has been shown to permit the cytofluorometric analysis of programmed cell death (apoptosis) in mammalian cells (19). It has been used by Ameisen et al. (1) for monitoring the complement-induced apoptosis-like changes in T. cruzi epimastigotes. As shown in Fig. 3C and D, cells submitted to geneticin-mediated cell death were easily distinguished from living (Fig. 3A and B) or necrotic (Fig. 3E and F) ones by using the combined analysis of their different patterns of forward and side-light scatter properties and YOPRO-1 staining. Susceptible wild-type amastigotes of L. infantum treated with 50 μg of Sb(III) per ml expressed the cytofluorometry features of geneticin-treated cells. More than 60% of the parasite population presents apoptotic-like features (Fig. 3G and H). The apoptosis-like death which has been shown to occur in Sb(III)-treated amastigotes using either the TUNEL technique or YOPRO-1 staining was also detected by monitoring the genomic DNA status of treated versus untreated parasites. As shown in Fig. 4 (lane 1), DNA fragmentation into fragments of about 200 bp, close to the oligonucleosome-sized fragment observed during apoptosis, was readily visible in the case of the Sb(III)-treated amastigotes. No fragmentation was detected in the case of the untreated LdiWT amastigotes (Fig. 4, lane 2).

FIG. 1.

In situ analysis of L. infantum axenic amastigote DNA fragmentation (TUNEL). Shown are positive-control untreated wild-type amastigotes (A), wild-type untreated parasites whose DNA was digested by DNase I for 10 min (B), wild-type parasites treated with 10 μg of potassium antimonyl tartrate [Sb(III)] per ml for 24 h (C), with 160 μg of meglumine [Sb(V)] per ml for 24 h (D), or with 1 mg of geneticin per ml for 24 h (E), and LdiR120 mutants treated with 50 μg of potassium antimonyl tartrate [Sb(III)] per ml for 24 h (F). DNA fragmentation was determined using the TUNEL method and analyzed under a microscope at a magnification of ×1,600.

FIG. 2.

Cytofluorometry (TUNEL) analysis of the antimonial-induced DNA fragmentation in axenic amastigotes. Results are shown for untreated wild-type parasite control (A) and wild-type amastigotes incubated for 24 h with medium in the presence of 2 mg of geneticin per ml (B), 2 mg of geneticin per ml without terminal transferase enzyme (negative control) (C), 10 and 50 μg of potassium antimonyl tartrate [Sb(III)] per ml (D and E, respectively), or 160 μg of meglumine [Sb(V)] per ml (F). Results for untreated LdiR120 amastigotes (G) and LdiR120 amastigotes incubated in medium containing 50 μg of potassium antimonyl tartrate per ml (H) are shown. After the incubation period, parasites were processed by the TUNEL technique and analyzed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson). The increase in FL1 fluorescence intensity was monitored. The percentage of apoptotic cells which corresponds to an increase of FL1 fluorescence (M2) is indicated for each experimental condition.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of the antimonial-induced death of axenic amastigotes using the cytofluorometry YOPRO-1 differential-staining technique. Parasites were incubated in the absence (A and B) or presence of 2 mg of geneticin per ml (C and D), for 10 min in the presence of saponin (E and F), for 24 h in medium containing 50 μg of potassium antimonyl tartrate per ml (G and H) and in the presence of 160 μg of meglumine [Sb(V)] for 24 h (I and J) or for 5 days (K and L). The percentages of cells presenting apoptosis-like changes and corresponding to both reduced forward scatter and high fluorescence intensity (R2) are indicated in each experimental condition. M1 (panels B, D, F, H, J, and L), peak of fluorescence intensity.

FIG. 4.

Oligonucleosomal-DNA fragmentation analysis. Agarose gel electrophoresis of DNA is shown. Lane 1, Sb(III)-treated LdiWT (50 μg/ml for 24 h); lane 2, untreated LdiWT amastigote parasites; lane 3, molecular size markers.

The results presented so far demonstrate that cell death in amastigote forms of L. infantum could be associated with endonuclease activity, which is responsible for the DNA fragmentation that occurs as a result of apoptosis. In mammalian cells, cysteine proteases of the caspase family, Ca+-sensitive calpains, or proteasome can initiate cell death. However, we report that inhibitors of caspase-3 (inhibitory peptide Z-DEVD-CMK, 5 μM) and caspase-1 (inhibitory peptide Z-VAD-FMK, 5 μM), calpain (calpain I inhibitor, 20 μM), cysteine proteases [E-64, (2S,3S)-trans-epoxy-epoxysuccinyl-l-leucylamido-3-methylbutane ethyl ester, 20 μM] or proteasome (lactacystin, 10 μM) were without effect on cell death brought about by trivalent antimonial on axenic amastigotes of L. infantum (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Apoptosis-like changes have been reported for T. cruzi in response to conditioned medium or the antibiotic G418 (1). A shift in the distribution of elongation factor 1-alpha (EF-1α) to a nuclear localization was reported as one of the changes accompanying cell death (6). In L. amazonensis, apoptosis-like changes were reported in response to heat shock (25). In this study, we demonstrate that antimonials in clinical use were able to induce cell death with features of apoptosis (i.e., DNA fragmentation) on the clinically relevant stage of L. infantum.

The combined use of several techniques including YOPRO-1 staining, DNA fragmentation assay and in situ and cytofluorometry TUNEL methods demonstrated that the toxicity of Sb(III) species against axenic amastigotes is associated with oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation, indicative of the occurrence of late events in the overall process of apoptosis. The death, mediated by Sb(III) species on axenic amastigotes, is massive even after a short incubation period (1 day) and at low concentration (10 μg/ml). These observations were in agreement with previous reports showing a relatively high efficacy of trivalent antimonials against axenic amastigotes of various Leishmania species (12, 13, 37, 38). We show that meglumine has no effect either on the viability (37) or on the DNA status of axenic amastigotes, suggesting that macrophages probably play an important role in pentavalent antimonial toxicity against intracellular amastigotes.

The biochemical pathways that mediate or regulate the endonuclease activity in trypanosomatids are still unknown. In multicellular organisms, protease activation is an important component of the cell death process (17). Recent studies have demonstrated that in T. brucei brucei reactive oxygen species initiate a Ca+-dependent sequence of events associated with endonuclease activity which culminates in cell death (30). In order to clarify more precisely the implication of protease in the DNA fragmentation induced by antimonials, we used several inhibitors. Although inhibitors of some caspases were not tried, the inhibitors used are known at least to block the caspases directly and indirectly responsible for the activation of endonuclease activity (caspase-1 and caspase-3). The lack of involvement of calpains, proteasome, and cysteine proteases suggests that some specific proteins, distinct from those in metazoans, are involved in the cell death promoted by antimonials as has been suggested for T. brucei brucei (30). Finally, as antimonials have been in clinical use since 1940 and continue to be the mainstay of antileishmanial therapy, it could be reasonably assumed that a better understanding of the mechanisms that regulate the cell death in chemoresistant mutants may help us to design new therapeutic strategies against Leishmania parasites.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ameisen J C, Idziorek T, Billaut-Mullot O, Tissier J P, Potentier A, Ouaissi A. Apoptosis in a unicellular eukaryote (Trypanosoma cruzi): implication for the evolutionary origin and role of programmed cell death in the control of cell proliferation, differentiation and survival. Cell Death Differ. 1995;2:285–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ameisen J C. The origin of programmed cell death. Science. 1996;272:1278–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5266.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berman J D. Chemotherapy for leishmaniasis: biochemical mechanisms, clinical efficacy and future strategies. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:560–586. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman J D, Waddell D, Hanson B D. Biochemical mechanisms of the antileishmanial activity of sodium stibogluconate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;27:916–920. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.6.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berman J D, Gallalee J V, Best J M. Sodium stibogluconate (pentostam) inhibition of glucose catabolism via the glycolytic pathway, and fatty acid beta oxidation in Leishmania mexicana amastigotes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1987;36:197–201. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(87)90689-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billaut-Mulot O, Fernandez-Gomez R, Loyens M, Ouaissi A. Trypanosoma cruzi elongation factor 1-alpha: nuclear localization in parasites undergoing apoptosis. Gene. 1996;174:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callahan H L, Portal A C, Devereaux R, Grögl M. An axenic amastigote system for drug screening. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:818–822. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.4.818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y C, Lin-Shiau S Y, Lin J K. Involvement of reactive oxygen species and caspase 3 activation in arsenite-induced apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 1998;177:323–333. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199811)177:2<324::AID-JCP14>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen J J. Apoptosis. Immunol Today. 1993;14:126–130. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coombs G H, Craft J A, Hart D T. A comparative study of Leishmania mexicana amastigotes and promastigotes. Enzyme activities and subcellular locations. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1982;5:199–211. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(82)90021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ephros M, Bitnun A, Shaked P, Waldman E, Zilberstein D. Stage-specific activity of pentavalent antimony against Leishmania donovani axenic amastigotes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:278–282. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ephros M, Waldman E, Zilberstein D. Pentostam induces resistance to antimony and the preservative chlorocresol in Leishmania donovani promastigotes and axenically grown amastigotes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1064–1068. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faraut-Gambarelli F, Piarroux R, Deniau M, Giusano B, Marty P, Michel G, Faugère B, Dumon H. In vitro and in vivo resistance of Leishmania infantum to meglumine antimoniate: a study of 37 strains collected from patients with visceral leishmaniasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:827–830. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.4.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gebre-Hiwot A, Tadesse G, Croft S L, Frommel D. An in vitro model for screening antileishmanial drugs: the human leukemia monocyte cell line, THP-1. Acta Trop. 1992;51:237–245. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(92)90042-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodwin L G, Page J E. A study of the excretion of organic antimonials using a polarographic procedure. Biochem J. 1943;22:236–240. doi: 10.1042/bj0370198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodwin L C. Pentostam (sodium stibogluconate); a 50-year personal reminiscence. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:339–341. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(95)90572-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green D, Kroemer G. The central executioners of apoptosis: caspases or mitochondria? Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:267–271. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grögl M, Thomason T N, Franke E. Drug resistance in leishmaniasis: its implication in systemic chemotherapy of cutaneous and mucocutaneous disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:117–126. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Idzioreck T, Estaquier J, De Bels F, Ameisen J C. YOPRO-1 permits cytofluorometric analysis of programmed cell death (apoptosis) without interfering with cell viability. J Immunol Methods. 1995;185:249–258. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larochette N, Decaudin D, Jacobot E, Brenner C, Marzo I, Susin S A, Zamzami N, Reed Z, Kroemer G. Arsenite induces apoptosis via direct effect on the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Exp Cell Res. 1999;249:413–421. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemesre, J. L. May 1994. Methods for the culture in vitro of different stages of tissue parasites. International publication no. WO 94/26899.

- 22.Lemesre J L, Sereno D, Daulouède S, Veyret B, Brajon N, Vincendeau P. Leishmania spp: nitric oxide-mediated metabolic inhibition of promastigote and axenically-grown amastigote forms. Exp Parasitol. 1997;86:58–68. doi: 10.1006/expr.1997.4151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lira R, Sundar S, Makharia A, Kenney R, Gam A, Saraiva E, Sacks D. Evidence that the high incidence of treatment failures in Indian kala-azar is due to the emergence of antimony-resistant strains of Leishmania donovani. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:564–567. doi: 10.1086/314896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma D C, Sun Y H, Chang K Z, Ma X F, Huang S L, Bai Y H, Kang J, Liu Y G, Chu J J. Selective induction of apoptosis of NB4 cells from G2+M phase by sodium arsenite at lower doses. Eur J Haematol. 1998;61:27–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1998.tb01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moreira M E, Del Portillo H A, Milder R V, Balanco J M, Barcinski M A. Heat shock induction of apoptosis in promastigotes of the unicellular organism Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis. J Cell Physiol. 1996;167:305–313. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199605)167:2<305::AID-JCP15>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mottram J C, Coombs G H. Leishmania mexicana: enzyme activities of amastigotes and promastigotes and their inhibition by antimonials and arsenicals. Exp Parasitol. 1985;59:151–160. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(85)90067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Müller S, Miller W H, Dejean A. Trivalent antimonials induce degradation of the PML-RARα oncoprotein and reorganization of the promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies in acute leukemia NB4 cells. Blood. 1998;92:4308–4316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouellette M, Papadopoulou B. Mechanisms of drug resistance in Leishmania. Parasitol Today. 1993;9:150–153. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(93)90135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peters B S, Fish D, Golden R, Evans D A, Bryceson A D M, Pinching A J. Visceral leishmaniasis in HIV infection and AIDS: clinical features and response to therapy. Q J Med. 1990;77:1101–1111. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/77.2.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ridgley E L, Xiong Z H, Ruben L. Reactive oxygen species activate a Ca2+-dependent cell death pathway in the unicellular organism Trypanosoma brucei brucei. Biochem J. 1999;340:33–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts W L, Berman J D, Rainey P M. In vitro antileishmanial properties of tri- and pentavalent antimonial preparations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1234–1239. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samali A, Zhivotovsky B, Jones D, Nagata S, Orrenius S. Apoptosis: cell death defined by caspase activation. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:495–496. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sereno D, Lemesre J L. In vitro life cycle of pentamidine-resistant amastigotes: stability of the chemoresistant phenotypes is dependent on the level of resistance induced. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1898–1903. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.9.1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sereno D, Lemesre J L. Axenically cultured amastigote forms as an in vitro model for investigation of antileishmanial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:972–976. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sereno D, Lemesre J L. Use of an enzymatic in vitro micromethod to quantify amastigote stage of axenically grown amastigote forms of Leishmania amazonensis. Parasitol Res. 1997;83:401–403. doi: 10.1007/s004360050272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sereno D, Michon P, Brajon N, Lemesre J L. Phenotypic characterization of Leishmania mexicana pentamidine-resistant promastigotes: modulation of the resistance during developmental life cycle. C R Acad Sci. 1997;320:981–987. doi: 10.1016/s0764-4469(97)82471-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sereno D, Cavaleyra M, Zemzoumi K, Maquaire S, Ouaissi A, Lemesre J L. Axenically-grown amastigotes of Leishmania infantum used as an in vitro model to investigate the pentavalent antimony mode of action. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3097–3102. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.12.3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sereno D, Roy G, Lemesre J L, Papadopoulou B, Ouellette M. DNA transformation of Leishmania infantum axenic amastigote and their use in drug screening. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:1168–1173. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1168-1173.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ullman B. Multidrug resistance and P-glycoproteins in parasitic protozoa. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1995;27:77–84. doi: 10.1007/BF02110334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ullman B, Carrero-Valenzuella E, Coons T. Leishmania donovani: isolation and characterization of sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam)-resistant cell lines. Exp Parasitol. 1989;69:157–163. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(89)90184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vaux D L, Strasser A. The molecular biology of apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2239–2244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaux D L. Caspases and apoptosis–biology and terminology. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:493–494. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang T S, Kuo C F, Jan K Y, Huang H. Arsenite induces apoptosis in chinese hamster ovary cells by generation of reactive oxygen species. J Cell Physiol. 1996;169:256–268. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199611)169:2<256::AID-JCP5>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watson R W, Redmond H P, Wang J H, Bouchler-Hayes D. Mechanisms involved in sodium arsenite-induced apoptosis of human neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;60:625–632. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.5.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Welburn S C, Barcinski M A, Williams G T. Programmed cell death in trypanosomatids. Parasitol Today. 1997;13:22–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(96)10076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]