Abstract

Objective

To study the relationship between clinical characteristics and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) fusions, c‐ros oncogene 1, receptor tyrosine kinase (ROS1) gene fusions, and epidermic growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations in non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients to distinguish these different types.

Methods

Both ALK, ROS1 gene rearrangements and EGFR mutations testing were performed. The clinical characteristics and associated pulmonary abnormalities were investigated.

Results

Four hundred fifty‐three NSCLC patients were included for analysis. One hundred seventy (37.5%), 32 (7.1%), and 9 cases (2.0%) with EGFR mutations, ALK gene fusions, and ROS1 gene fusions were identified, respectively. The EGFR‐positive and ALK&ROS1‐positive were more common in female (χ 2 = 61.934, P < 0.001 and χ 2 = 28.152, P < 0.001), non‐smoking (χ 2 = 59.315, P < 0.001 and χ 2 = 11.080, P = 0.001), and adenocarcinoma (χ 2 = 44.864, P < 0.001 and χ 2 = 12.318, P = 0.002) patients; proportion of patients with emphysema was lower (χ 2 = 35.494, P < 0.001 and χ 2 = 15.770, P < 0.001) than the wild‐type patients. The results of logistic regression analysis indicated that female (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 1.834, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.069–3.144, P = 0.028), non‐smoking (adjusted OR 2.504, 95% CI 1.456–4.306, P = 0.001), lung adenocarcinoma (adjusted OR 4.512, 95% CI 2.465–8.260, P < 0.001), stage III–IV (adjusted OR 2.232, 95% CI 1.066–4.676, P = 0.033), and no symptoms of emphysema (adjusted OR 2.139, 95% CI 1.221–3.747, P = 0.008) were independent variables associated with EGFR mutations. Young (adjusted OR 3.947, 95% CI 1.873–8.314, P < 0.001) and lung adenocarcinoma (adjusted OR 2.950, 95% CI 0.998–8.719, P = 0.050) were associated with ALK/ROS1 fusions.

Conclusions

EGFR mutations were more likely to occur in non‐smoking, stage III–IV, and female patients with lung adenocarcinoma, whereas ALK&ROS1 gene fusions were more likely to occur in young patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Emphysema was less common in patients with EGFR mutations.

Keywords: ALK, clinical characteristics, EGFR, emphysema, ROS1

Abbreviations

- ALK

anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- ARMS

amplification refractory mutation system

- EGFR

epidermic growth factor receptor

- EML4

echinoderm microtubule associated protein‐like 4

- NSCLC

non‐small cell lung cancer

- ROS1

proto‐oncogene protein tyrosine kinase ROS

1. INTRODUCTION

With the increasing morbidity and mortality, lung cancer has become the first malignant tumor. Lung cancer has the highest morbidity and mortality among men in China. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 The morbidity of lung cancer among women in China ranks second and the mortality rate of lung cancer among women is the first. 5 Non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for more than 80% of all patients with lung cancer. 6 , 7

In recent years, personalized molecular targeted therapy as the core has become a research hotspot in the treatment of lung cancer. 8 , 9 , 10 Currently, the most commonly used treatment of NSCLC is molecular targeted drugs targeting at mutations of epidermic growth factor receptor (EGFR), also known as small‐molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), which have obvious clinical efficacy on NSCLC patients with EGFR sensitive mutations. 11 EGFR is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor, expressed in a variety of epithelial tumors, and regulates tumor cell growth, invasion, transformation, angiogenesis, and metastasis by activating downstream signal transduction proteins. 12 The main mechanism of EGFR‐TKI is to selectively bind ATP binding sites in the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR in cells, block the phosphorization and activation of tyrosine itself in EGFR molecules through the Akt‐MAPK pathway, and inhibit RAS/RAF/MAPK, PI3K‐Akt, and other downstream signaling pathways and lead to apoptosis of tumor cells. 13

Echinoderm microtubule associated protein‐like 4 (EML4) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) fusion gene EML4‐ALK and proto‐oncogene protein tyrosine kinase ROS (ROS1) were found after EGFR mutations in NSCLC. 14 , 15 , 16 ALK and ROS1 rearrangements define important molecular subgroups of NSCLC. After discovery of ALK rearrangements in NSCLC, it was recognized that these confer sensitivity to ALK inhibition. 17 For NSCLC patients with ALK gene fusion and ROS1 gene fusion, targeted therapy with Crizotinib could achieve better efficacy. 18 Therefore, the detection of EGFR, ALK, and ROS1 (ALK&ROS1) gene mutations before targeted therapy is of great significance for the prediction of the efficacy of targeted therapy and the appropriate patient screening.

The mutation status of targeted therapy driver gene in NSCLC is closely related to its pathological classification. The differences between different pathological subtypes of lung cancer are of great significance for clinical treatment and prognosis of lung cancer patients. The relationship between the mutation status of targeted therapeutically driven genes and clinicopathology in NSCLC has not been consistent. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the clinical characteristics of NSCLC patients in order to distinguish ALK&ROS1 gene rearrangements, EGFR mutations, and non‐ALK&ROS1/EGFR (no mutations and rearrangements), so as to distinguish these different types, to assist clinicians to assess the NSCLC patients with these genetic abnormalities.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Specimen collection

Test specimens of NSCLC patients were collected from the Meizhou People's Hospital (Huangtang Hospital) (Meizhou, Guangdong, China) between April 2018 and August 2019. All protocols were approved by the Human Ethics Committees of Meizhou People's Hospital, Meizhou Academy of Medical Sciences. The medical records of each patient were reviewed and the corresponding clinical characteristics were extracted.

2.2. DNA and RNA extraction

Ten pieces of formalin‐fixed and paraffin‐embedded (FFPE) slices (5 μm thick per slice) were placed into a 1.5‐ml EP tube. After FFPE slices were deparaffinized, DNA and RNA were extracted by AmoyDx® Tissue DNA/RNA Co‐separation Kit (Spin Column) (Amoy Diagnostics, Xiamen, China), following the manufacturers' instructions, and the quantity and quality of extracted DNA and RNA were evaluated.

2.3. Detection of EGFR gene mutations by ARMS PCR

EGFR gene mutations were detected by real‐time amplification refractory mutation system (ARMS)‐PCR, and the 29 mutational hotspots from exon 18 to 21 in this gene were covered with the EGFR Gene Mutations Fluorescence Polymerase Chain Reaction Diagnostic Kit (Amoy Diagnostics, Xiamen, China). PCR was performed with initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 15 cycles of first amplification (at 95°C for 25 s, 64°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 20 s) and 31 cycles of second amplification (at 95°C for 25 s, 60°C for 35 s, and 72°C for 20 s). Positive results were defined as Ct (sample) − Ct (control) < Ct (cut‐off) according to the criteria defined by the manufacturer's instructions.

2.4. Detection of ALK and ROS1 gene fusions by RT‐PCR

The fusion genes of ALK and ROS1 were analyzed by RT‐PCR according to the manufacturer's protocol of AmoyDx® ALK Gene Fusions and ROS1 Gene Fusions Detection Kit (Amoy Diagnostics, Xiamen, China) with the LightCycler 480 real‐time PCR system. The detection range included the fusions of ALK gene with EML4, KIF5B, TFG, and KLC1 genes, and the fusions of ROS1 gene with SLC34A2, CD74, SDC4, EZR, TPM3, LRIG3, and GOPC genes. Reverse transcription reaction system: reverse transcriptase 0.5 μl, RNA template 6 μl (total RNA 0.5–5.0 μg), 42°C for 1 h, and 95°C for 5 min. PCR amplification: 1.5 μl ALK&ROS1 mixed enzyme was respectively taken to ALK cDNA and ROS1 cDNA of the samples to be tested, 5 μl was successively transferred to the eight‐tube strip PCR reaction system, and negative and positive controls were set up. The detection instrument and circulating conditions were the same as EGFR mutation detection, and Ct values were also interpreted.

2.5. Statistical analysis

All analysis was conducted using SPSS statistical software Version 21.0. Fisher's exact test and the Student's t‐test were performed in this study. EGFR‐positive group, ALK&ROS1‐positive group, and non‐ALK&ROS1/EGFR group, pairwise comparisons were performed. The relationship between EGFR, ALK, and ROS1 genes mutations and clinical characteristics, various types of mutations in the EGFR gene, and clinical characteristics were analyzed. Logistic regression analysis was applied to assess the variables independently associated with EGFR and ALK/ROS1 genes mutations. P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Population characteristics

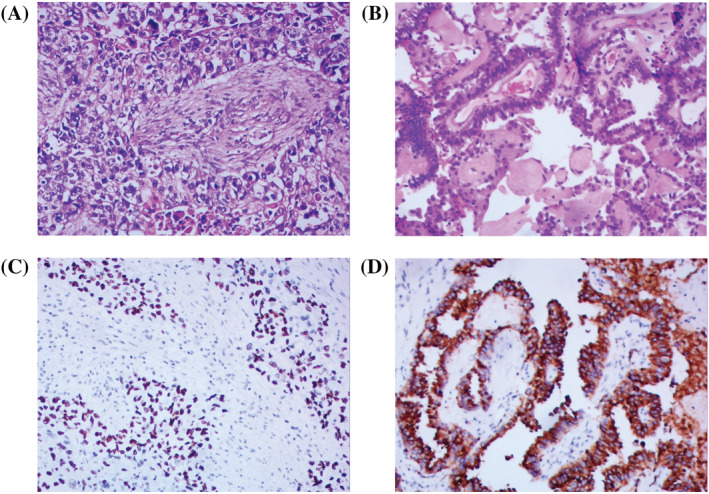

This study involved 453 Chinese NSCLC patients who performed with EGFR mutation and ALK&ROS1 fusion test. A total of 308 patients were male and 145 were female. There were 341 (341/453, 75.3%) patients with lung adenocarcinoma, 106 (106/453, 23.4%) patients with lung squamous cell carcinoma, and 6 (6/453, 1.3%) patients with lung adenosquamous cell carcinoma, respectively. Hematoxylin–eosin (HE) staining and immunohistochemical staining for squamous cell carcinoma and lung adenocarcinoma are shown in Figure 1. Most of these patients, 248 (248/453, 54.7%) were nonsmokers and 269 (269/453, 59.4%) were older than 60 years old. Thirty‐three (7.3%), 17 (3.8%), 90 (19.9%), and 313 (69.1%) patients were in stage I, II, III, and IV, respectively. The clinical characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Pathological features of non‐small cell lung cancer. (A) Hematoxylin–eosin (HE) staining of squamous cell carcinoma; (B) HE staining of adenocarcinoma; (C) immunohistochemical staining of P63 expression in squamous cell carcinoma; (D) immunohistochemical staining of Napsin A expression in adenocarcinoma; scale bar, 100 μm

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patients with lung cancer included in this study

| Parameter | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| ≤60 | 184 (40.6) |

| >60 | 269 (59.4) |

| Mean ± SD | 61.92 ± 10.24 |

| Range | 27–87 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 308 (68.0) |

| Female | 145 (32.0) |

| Smoking status | |

| No smoking | 248 (54.7) |

| Smoking | 205 (45.3) |

| Pathology | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 341 (75.3) |

| Squamous | 106 (23.4) |

| Adenosquamous | 6 (1.3) |

| Disease stage | |

| I | 33 (7.3) |

| II | 17 (3.7) |

| III | 90 (19.9) |

| IV | 313 (69.1) |

3.2. Comparisons of characteristics between EGFR‐positive and ALK&ROS1‐positive cases, ALK&ROS1‐positive and non‐ALK&ROS1/EGFR cases, and EGFR‐positive and non‐ALK&ROS1/EGFR cases in NSCLC patients

A total of 170 cases with EGFR mutations in exons 18, 19, 20, or 21 (170/453, 37.5%) were identified in the 453 patients. The G719X mutation (in exon 18) was identified in 1 case (0.6%); exon 19 deletion were identified in 90 cases (57.0%), exon 20 insertion were detected in 2 cases (1.3%), L858R mutation (in exon 21) were detected in 60 cases (38.0%), and L861Q mutation (in exon 21) were detected in 5 cases (3.2%). ALK gene fusions were identified in 32 cases (32/453, 7.1%) and ROS1 gene fusions were identified in 9 cases (9/453, 2.0%).

Compared with the EGFR‐positive group, the significant differences in ALK&ROS1‐positive group were younger (P < 0.001). There were no significant differences in gender, smoking history, histologic type, clinical stage, and computed tomography characteristics (lymphangitis, lymphadenopathy, emphysema, fibrosis, and pleural effusion).

The characteristics of patients with EGFR‐positive and non‐ALK&ROS1/EGFR (wild type) were compared. In the EGFR‐positive group, the majority were female (χ 2 = 61.934, P < 0.001), non‐smoking (χ 2 = 59.315, P < 0.001), and adenocarcinoma (χ 2 = 44.864, P < 0.001) patients. In addition, there were significant differences in clinical stage (χ 2 = 14.642, P = 0.002), proportion of patients with emphysema (χ 2 = 35.494, P < 0.001), and pulmonary fibrosis (χ 2 = 4.529, P = 0.038). There were no significant differences in age, lymphangitis, lymphadenopathy, and pleural effusion.

Compared with the non‐ALK&ROS1/EGFR cases in NSCLC patients, the ALK&ROS1‐positive group that significantly differed from the non‐ALK&ROS1/EGFR group was younger (χ 2 = 19.920, P < 0.001); the majority were female (χ 2 = 28.152, P < 0.001), non‐smoking (χ 2 = 11.080, P = 0.001), and adenocarcinoma (χ 2 = 12.318, P = 0.002) patients; proportion of patients with lymphangitis was higher (χ 2 = 4.647, P = 0.046); and proportion of patients with emphysema was lower (χ 2 = 15.770, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Comparisons of characteristics between EGFR‐positive and ALK/ROS1‐positive cases, ALK/ROS1‐positive and non‐ALK&ROS1/EGFR cases, and EGFR‐positive and non‐ALK/ROS1/EGFR cases in non‐small cell lung cancer patients

| Patient characteristic | EGFR (+) (n = 170) | ALK/ROS1 fusion (+) (n = 41) | Non‐ALK/ROS1/EGFR (wild type) (n = 244) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR (+) versus ALK/ROS1 fusion (+) | EGFR (+) versus wild type | ALK/ROS1 fusion (+) versus wild type | ||||

| No. (total 453) | 170 (37.5) | 41 (9.0) | ||||

| Age | <0.001 (χ 2 = 14.612) | 0.471 (χ 2 = 0.660) | <0.001 (χ 2 = 19.920) | |||

| ≤60 | 68 (40.0) | 30 (73.2) | 88 (36.1) | |||

| >60 | 102 (60.0) | 11 (26.8) | 156 (63.9) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 61.85 ± 9.79 | 55.49 ± 12.62 | 62.97 ± 9.76 | <0.001 | 0.254 | <0.001 |

| Range | 27–86 | 30–85 | 28–87 | |||

| Gender | 0.996 | <0.001 (χ 2 = 61.934) | <0.001 (χ 2 = 28.152) | |||

| Male | 83 (48.8) | 20 (48.8) | 207 (84.8) | |||

| Female | 87 (51.2) | 21 (51.2) | 37 (15.2) | |||

| Smoking | 0.162 (χ 2 = 1.955) | <0.001 (χ 2 = 59.315) | 0.001 (χ 2 = 11.080) | |||

| No smokingc | 130 (76.5) | 27 (65.9) | 93 (38.1) | |||

| Smoking | 40 (23.5) | 14 (34.1) | 151 (61.9) | |||

| Histologic type | 0.636 (χ 2 = 0.906) | <0.001 (χ 2 = 44.864) | 0.002 (χ 2 = 12.318) | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 154 (90.6) | 37 (90.2) | 152 (62.3) | |||

| Squamous | 13 (7.6) | 4 (9.8) | 89 (36.5) | |||

| Adenosquamous | 3 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.2) | |||

| Disease stage | 0.269 (χ 2 = 3.932) | 0.002 (χ 2 = 14.642) | 0.403 (χ 2 = 2.926) | |||

| I | 16 (9.4) | 4 (9.8) | 13 (5.3) | |||

| II | 10 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 7 (2.9) | |||

| III | 20 (11.8) | 8 (19.5) | 62 (25.4) | |||

| IV | 124 (72.9) | 29 (70.7) | 162 (66.4) | |||

| Lymphangitis | 28 (16.5) | 10 (24.4) | 29 (11.9) | 0.259 (χ 2 = 1.403) | 0.194 (χ 2 = 1.774) | 0.046 (χ 2 = 4.647) |

| Lymphadenopathy | 119 (70.0) | 29 (70.7) | 185 (75.8) | 0.927 (χ 2 = 0.008) | 0.214 (χ 2 = 1.739) | 0.558 (χ 2 = 0.486) |

| Emphysema | 25 (14.7) | 4 (9.8) | 103 (42.2) | 0.613 (χ 2 = 0.683) | <0.001 (χ 2 = 35.494) | <0.001 (χ 2 = 15.770) |

| Fibrosis | 15 (8.8) | 2 (4.9) | 39 (16.0) | 0.535 (χ 2 = 0.694) | 0.038 (χ 2 = 4.529) | 0.089 (χ 2 = 3.515) |

| Pleural effusion | 71 (41.8) | 15 (36.6) | 91 (37.3) | 0.598 (χ 2 = 0.367) | 0.413 (χ 2 = 0.840) | 0.931 (χ 2 = 0.008) |

3.3. The association between EGFR, ALK&ROS1 genes status and clinical characteristics

Compared with EGFR‐negative cases, the most were female (χ 2 = 45.938, P < 0.001), non‐smoking (χ 2 = 51.838, P < 0.001), and adenocarcinoma (χ 2 = 37.731, P < 0.001) patients in the EGFR‐positive group. In addition, there were significant differences in clinical stage (χ 2 = 14.554, P = 0.002) and proportion of patients with emphysema (χ 2 = 27.454, P < 0.001). There were no significant differences in age, lymphangitis, lymphadenopathy, fibrosis, and pleural effusion.

Compared with the ALK&ROS1‐negative group, the ALK&ROS1‐positive group was younger than the ALK&ROS1‐negative group (χ 2 = 19.805, P < 0.001). In the ALK&ROS1‐positive group, the most were female (χ 2 = 7.644, P = 0.008) patients, and proportion of patients with emphysema was lower (χ 2 = 8.202, P = 0.003) than the ALK&ROS1‐negative group. There were no significant differences in smoking history, histologic type, clinical stage, lymphangitis, lymphadenopathy, fibrosis, and pleural effusion between the ALK&ROS1‐negative group and the ALK&ROS1‐positive group (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Analysis of the relationship between EGFR and ALK/ROS1 genes status and clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | EGFR mutation | ALK/ROS1 fusion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | P value | + | − | P value | |

| No. (total 453) | 170 (37.5) | 283 (62.5) | 41 (9.1) | 412 (90.9) | ||

| Age | 0.844 (χ 2 = 0.043) | <0.001 (χ 2 = 19.805) | ||||

| ≤60 | 68 (40.0) | 116 (41.0) | 30 (73.2) | 154 (37.4) | ||

| >60 | 102 (60.0) | 167 (59.0) | 11 (26.8) | 258 (62.6) | ||

| Gender | <0.001 (χ 2 = 45.938) | 0.008 (χ 2 = 7.644) | ||||

| Male | 83 (48.8) | 225 (79.5) | 20 (48.8) | 288 (69.9) | ||

| Female | 87 (51.2) | 58 (20.5) | 21 (51.2) | 124 (30.1) | ||

| Smoking | <0.001 (χ 2 = 51.838) | 0.142 (χ 2 = 2.245) | ||||

| No smoking | 130 (76.5) | 118 (41.7) | 27 (65.9) | 221 (53.6) | ||

| Smoking | 40 (23.5) | 165 (58.3) | 14 (34.1) | 191 (46.4) | ||

| Histologic type | <0.001 (χ 2 = 37.731) | 0.063 (χ 2 = 5.525) | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 154 (90.6) | 187 (66.1) | 37 (90.2) | 304 (73.8) | ||

| Squamous | 13 (7.6) | 93 (32.9) | 4 (9.8) | 102 (24.8) | ||

| Adenosquamous | 3 (1.8) | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 6 (1.5) | ||

| Disease stage | 0.002 (χ 2 = 14.554) | 0.554 (χ 2 = 2.090) | ||||

| I | 16 (9.4) | 17 (6.0) | 4 (9.8) | 29 (7.0) | ||

| II | 10 (5.9) | 7 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 17 (4.1) | ||

| III | 20 (11.8) | 70 (24.7) | 8 (19.5) | 82 (19.9) | ||

| IV | 124 (72.9) | 189 (66.8) | 29 (70.7) | 284 (68.9) | ||

| Lymphangitis | 28 (16.5) | 39 (13.8) | 0.495 (χ 2 = 0.610) | 10 (24.4) | 57 (13.8) | 0.102 (χ 2 = 3.297) |

| Lymphadenopathy | 119 (70.0) | 212 (74.9) | 0.275 (χ 2 = 1.302) | 29 (70.7) | 302 (73.3) | 0.714 (χ 2 = 0.125) |

| Emphysema | 25 (14.7) | 107 (37.8) | <0.001 (χ 2 = 27.454) | 4 (9.8) | 128 (31.1) | 0.003 (χ 2 = 8.202) |

| Fibrosis | 15 (8.8) | 41 (14.5) | 0.079 (χ 2 = 3.145) | 2 (4.9) | 54 (13.1) | 0.209 (χ 2 = 2.331) |

| Pleural effusion | 71 (41.8) | 105 (37.1) | 0.370 (χ 2 = 0.972) | 15 (36.6) | 161 (39.1) | 0.867 (χ 2 = 0.097) |

3.4. The relationship between various types of mutations in the EGFR gene and clinical characteristics

Patients with mutations at 2 or more locations of the EGFR gene and with T790M resistance mutation were excluded from this analysis. Among the exon 19 deletion, L858R, L861Q, G719X mutations, and exon 20 insertion in EGFR, there were no significant differences in age and gender. The NSCLC patients with exon 19 deletion (73.3%) and L858R (85.0%) most were non‐smokers, whereas patients with L861Q (60.0%) most were smokers (Table 4). But the sample size of patients with L861Q, G719X mutations, and exon 20 insertion in our study is relatively small, and this result cannot represent the actual situation and we need a large sample size to analyze this problem.

TABLE 4.

Analysis of the relationship between various types of mutations in the EGFR gene and clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | Exon 19 deletion | L858R | L861Q | G719X | Exon 20 insertion | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (total 158) | 90 (56.9) | 60 (38.0) | 5 (3.2) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Age | 0.058 (χ 2 = 9.145) | |||||

| ≤60 | 44 (48.9) | 17 (28.3) | 2 (40.0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| >60 | 46 (51.1) | 43 (71.7) | 3 (60.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | |

| Gender | 0.368 (χ 2 = 4.289) | |||||

| Male | 46 (51.1) | 25 (41.7) | 4 (80.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50.0) | |

| Female | 44 (48.9) | 35 (58.3) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (50.0) | |

| Smoking | 0.102 (χ 2 = 7.725) | |||||

| No smoking | 66 (73.3) | 51 (85.0) | 2 (40.0) | 1 (100) | 1 (50.0) | |

| Smoking | 24 (26.7) | 9 (15.0) | 3 (60.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50.0) | |

| Lymphangitis | 15 (16.7) | 7 (11.7) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (100) | 1 (50.0) | 0.093 (χ 2 = 7.966) |

| Lymphadenopathy | 56 (62.2) | 46 (76.7) | 4 (80.0) | 1 (100) | 1 (50.0) | 0.334 (χ 2 = 4.569) |

| Emphysema | 18 (20.0) | 6 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.366 (χ 2 = 4.304) |

| Fibrosis | 7 (7.8) | 6 (10.0) | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.864 (χ 2 = 1.287) |

| Pleural effusion | 38 (42.2) | 26 (43.3) | 3 (60.0) | 1 (100) | 1 (50.0) | 0.746 (χ 2 = 1.944) |

3.5. Logistic regression analysis of variables associated with EGFR mutations and ALK/ROS1 gene fusions

Logistic regression analysis was performed to determine independent variables associated with EGFR mutations and ALK/ROS1 gene fusions. The results indicated that female (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 1.834, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.069–3.144, P = 0.028), non‐smoking (adjusted OR 2.504, 95% CI 1.456–4.306, P = 0.001), lung adenocarcinoma (adjusted OR 4.512, 95% CI 2.465–8.260, P < 0.001), stage III–IV (adjusted OR 2.232, 95% CI 1.066–4.676, P = 0.033), and no symptoms of emphysema (adjusted OR 2.139, 95% CI 1.221–3.747, P = 0.008) were independent variables associated with EGFR mutations (Table 5). Young (adjusted OR 3.947, 95% CI 1.873–8.314, P < 0.001) and lung adenocarcinoma (adjusted OR 2.950, 95% CI 0.998–8.719, P = 0.050) were independent variables associated with ALK/ROS1 gene fusions (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Logistic regression analysis of variables associated with EGFR mutations and ALK/ROS1 gene fusions

| Variables | EGFR mutations | ALK/ROS1 gene fusions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted values | Adjusted values | Unadjusted values | Adjusted values | |||||

| P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Age (≤60/>60) | 0.836 | 0.960 (0.651–1.414) | 0.083 | 0.672 (0.428–1.054) | <0.001 | 4.569 (2.226–9.378) | <0.001 | 3.947 (1.873–8.314) |

| Gender (female/male) | <0.001 | 4.066 (2.680–6.169) | 0.028 | 1.834 (1.069–3.144) | 0.007 | 2.439 (1.276–4.660) | 0.153 | 1.923 (0.784–4.714) |

| Smoking (no/yes) | <0.001 | 4.544 (2.968–6.958) | 0.001 | 2.504 (1.456–4.306) | 0.137 | 1.667 (0.850–3.270) | 0.489 | 0.718 (0.281–1.835) |

| Histologic type (adenocarcinoma/non‐adenocarcinoma) | <0.001 | 4.941 (2.793–8.743) | <0.001 | 4.512 (2.465–8.260) | 0.027 | 3.286 (1.145–9.435) | 0.050 | 2.950 (0.998–8.719) |

| Disease stage (III–IV/I–II) | 0.027 | 1.948 (1.079–3.519) | 0.033 | 2.232 (1.066–4.676) | 0.784 | 0.860 (0.293–2.523) | 0.437 | 0.606 (0.171–2.143) |

| Lymphangitis (no/yes) | 0.435 | 0.811 (0.478–1.374) | 0.838 | 0.938 (0.506–1.738) | 0.074 | 0.498 (0.231–1.070) | 0.340 | 0.661 (0.282–1.548) |

| Lymphadenopathy (no/yes) | 0.254 | 1.280 (0.837–1.956) | 0.988 | 0.996 (0.589–1.683) | 0.724 | 1.136 (0.560–2.304) | 0.281 | 1.580 (0.688–3.625) |

| Emphysema (no/yes) | <0.001 | 3.526 (2.165–5.743) | 0.008 | 2.139 (1.221–3.747) | 0.008 | 4.169 (1.455–11.943) | 0.087 | 2.696 (0.866–8.389) |

| Fibrosis (no/yes) | 0.079 | 1.751 (0.937–3.270) | 0.378 | 1.386 (0.671–2.864) | 0.145 | 2.941 (0.690–12.533) | 0.405 | 1.906 (0.418–8.692) |

| Pleural effusion (no/yes) | 0.325 | 0.823 (0.558–1.213) | 0.661 | 0.903 (0.573–1.425) | 0.755 | 1.112 (0.571–2.163) | 0.460 | 1.314 (0.636–2.714) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

4. DISCUSSION

The number of lung cancer patients and death cases in China has ranked first among all malignant tumors. 3 , 19 , 20 In the past decade, as the development of tumor molecular diagnosis and the continuous discovery of targeted drugs, the treatment of NSCLC has entered an era of individualized molecular targeted therapy. With the discovery of therapeutic targets EGFR, ALK, and ROS1 and the advent of corresponding targeted drugs, targeted therapy has become a very effective way to treat NSCLC clinically. 21 Studies have shown that NSCLC patients with EGFR sensitive mutations and ALK&ROS1 gene fusions can benefit from corresponding targeted therapy. 10 , 22 , 23 Therefore, detection of EGFR, ALK&ROS1 gene mutations have important clinical significance in screening patients suitable for targeted therapy. In the present study, the clinical characteristics of NSCLC with ALK&ROS1 gene rearrangement and EGFR mutations were investigated. Distinguishing the clinical characteristics of different molecular subtypes will be beneficial to the diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer.

EGFR is a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase, and the activation or phosphorylation of this region is of great significance for the signaling of proliferation and growth of cancer cells. EGFR mutation mainly includes four types: deletion mutations in exon 19, point mutations in exon 21, point mutations in exon 18, and insertion mutations in exon 20, among which exon 19 deletion mutation and exon 21 L858R are the most common mutations sensitive to EGFR‐TKI therapy. 24 In concordance with previous reports, EGFR mutations were mainly 19 exon deletion mutations and exon 21 L858R mutation in 453 NSCLC patients of this study. A number of researches have shown that the incidence of EGFR mutation is higher in women, non‐smokers, and adenocarcinoma. 25 , 26 This study found that the incidence of EGFR mutation in women, adenocarcinoma, and non‐smokers is significantly higher than that in men, squamous cell carcinoma, and smokers, and the differences between these groups are statistically significant.

Since Soda et al. 27 first discovered a new EML4‐ALK gene fusion in NSCLC patients in 2007, many scholars have conducted studies on it. Regarding the mutation rate of EML4‐ALK in NSCLC, different literatures reported slight differences. Domestic and foreign research data showed that the incidence of ALK gene fusion in NSCLC patients was 3%–7%. 28 , 29 , 30 The positive rate of ROS1 gene fusion in NSCLC was 1.0%–3.4%, 31 and the clinical characteristics of ALK and ROS1 gene fusion lung cancer were also very similar. The results of this study showed that the positive rate of ALK and ROS1 genes fusions was 9.1%, and the incidence of ALK and ROS1 gene fusions were relatively high in female patients and those less than 60 years old. ALK gene fusions were identified in 32 cases (33/453, 7.3%) and ROS1 gene fusions were identified in 9 cases (9/453, 2.0%). Our work also confirms the low incidence of the ALK&ROS1 fusion among unselected NSCLC patients.

In this study, compared with non‐ALK&ROS1/EGFR mutations in NSCLC patients, patients with EGFR mutation had a lower incidence of pulmonary emphysema. And it reflected that most of NSCLC patients with EGFR mutation had a history of non‐smoking. A plausible reason for this is that EGFR mutation status have a stronger association with non‐emphysema status. Among the deletions in exon 19, L858R, L861Q, G719X, S768I mutations, and insertions in exon 20 of EGFR, there were no significant differences in age and gender. The NSCLC patients with deletions in exon 19 (74.7%) and L858R (86.4%) most were non‐smokers, whereas patients with L861Q (62.5%) and G719X (66.7%) most were smokers. But the sample size of patients with L861Q, G719X, S768I mutations, and insertions in exon 20 in our study is relatively small, and this result cannot represent the actual situation and we need a large sample size to analyze this problem.

According to reports, the incidence of ALK gene rearrangement in NSCLC patients is about 3%–7%, 10 whereas the incidence of EGFR mutation is 40%–80% 32 ; the sample size of patients with ALK&ROS1 gene rearrangement is small in our study. This is one of the limitations in this study. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the clinical characteristics of NSCLC patients to distinguish between ALK&ROS1 gene rearrangement, EGFR mutation, and non‐ALK&ROS1/EGFR mutation. These results may assist clinicians to assess the NSCLC patients with these genetic abnormalities.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this study suggests that EGFR mutations were more likely to occur in non‐smoking, stage III–IV, and female patients with lung adenocarcinoma, whereas ALK&ROS1 gene rearrangements were more likely to occur in young patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Emphysema was less common in patients with EGFR mutations.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Qinghua Liu and Heming Wu designed the study. Heming Wu and Zhikang Yu performed the experiments. Qinghua Liu recruited subjects and collected clinical data. Qingyan Huang and Zhikang Yu helped to analyze the data. Heming Wu prepared the manuscript. All authors were responsible for critical revisions, and all authors read and approved the final version of this work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All protocols were approved by the Human Ethics Committees of Meizhou People's Hospital, Meizhou Academy of Medical Sciences.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank other colleagues whom were not listed in the authorship of Center for Precision Medicine, Meizhou People's Hospital (Huangtang Hospital), Meizhou Academy of Medical Sciences for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

This study was supported by the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Precision Medicine and Clinical Translation Research of Hakka Population (Grant No. 2018B030322003), the Science and Technology Program of Meizhou (Grant No. 2019B0202001), and Key Scientific and Technological Project of Meizhou People’s Hospital (Grant No. MPHKSTP‐20190102).

Liu Q, Huang Q, Yu Z, Wu H. Clinical characteristics of non‐small cell lung cancer patients with EGFR mutations and ALK&ROS1 fusions. Clin Respir J. 2022;16(3):216-225. doi: 10.1111/crj.13472

Qinghua Liu and Qingyan Huang contributed equally to this work.

Funding information Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Precision Medicine and Clinical Translation Research of Hakka Population, Grant/Award Number: 2018B030322003; Science and Technology Program of Meizhou, Grant/Award Number: 2019B0202001; Key Scientific and Technological Project of Meizhou People’s Hospital, Grant/Award Number: MPHKSTP‐20190102

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Didkowska J, Wojciechowska U, Mańczuk M, Łobaszewski J. Lung cancer epidemiology: contemporary and future challenges worldwide. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(8):150‐160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359‐E386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang L. SC17.02 lung cancer in China: challenges and perspectives. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(1):S113‐S114. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shen X, Wang L, Zhu L. Spatial analysis of regional factors and lung cancer mortality in China, 1973–2013. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(4):569‐577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Han X, Guo Y, Gao H, et al. Estimating the spatial distribution of environmental suitability for female lung cancer mortality in China based on a novel statistical method. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2019;26(10):10083‐10096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yano S, Matsumori Y, Ikuta K, Ogino H, Doljinsuren T, Sone S. Current status and perspective of angiogenesis and antivascular therapeutic strategy: non‐small cell lung cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2006;11(2):73‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Román M, Baraibar I, López I, et al. KRAS oncogene in non‐small cell lung cancer: clinical perspectives on the treatment of an old target. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non‐small‐cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(25):2380‐2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):104‐105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, et al. First‐line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK‐positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(23):2167‐2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gelatti ACZ, Drilon A, Santini FC. Optimizing the sequencing of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation‐positive non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Lung Cancer. 2019;137:113‐122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. London M, Gallo E. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) involvement in epithelial‐derived cancers and its current antibody‐based immunotherapies. Cell Biol Int. 2020;44(6):1267‐1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hegi ME, Rajakannu P, Weller M. Epidermal growth factor receptor: a re‐emerging target in glioblastoma. Curr Opin Neurol. 2012;25(6):774‐779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kwak EL, Bang Y‐J, Camidge DR, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(18):1693‐1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Metro G, Tazza M, Matocci R, Chiari R, Crinò L. Optimal management of ALK‐positive NSCLC progressing on crizotinib. Lung Cancer. 2017;106(Complete):58‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhu Q, Hu H, Weng DS, et al. Pooled safety analyses of ALK‐TKI inhibitor in ALK‐positive NSCLC. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sgambato A, Casaluce F, Maione P, Gridelli C. Targeted therapies in non‐small cell lung cancer: a focus on ALK/ROS1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18(1):71‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhao Y, Wang S, Zhang B, et al. Clinical management of non‐small cell lung cancer with concomitant EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements: efficacy of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors and crizotinib. Target Oncol. 2019;14(2):169‐178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. She J, Yang P, Hong Q, Bai C. Lung cancer in China: challenges and interventions. Chest. 2013;143(4):1117‐1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hong QY, Wu GM, Qian GS, et al. Prevention and management of lung cancer in China. Cancer. 2015;121(S17):3080‐3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Domvri K, Zarogoulidis P, Darwiche K, et al. Molecular targeted drugs and biomarkers in NSCLC, the evolving role of individualized therapy. J Cancer. 2013;4(9):736‐754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Song A, Kim TM, Kim DW, et al. Molecular changes associated with acquired resistance to crizotinib in ROS1‐rearranged non‐small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(10):2379‐2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sequist LV, Martins RG, Spigel D, et al. First‐line gefitinib in patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer harboring somatic EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15):2442‐2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu G, Xu Z, Ge Y, et al. 3D radiomics predicts EGFR mutation, exon‐19 deletion and exon‐21 L858R mutation in lung adenocarcinoma. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2020;9(4):1212‐1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Keedy VL, Temin S, Somerfield MR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation testing for patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer considering first‐line EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;29(15):2121‐2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liang Z, Zhang J, Zeng X, Gao J, Wu S, Liu T. Relationship between EGFR expression, copy number and mutation in lung adenocarcinomas. BMC Cancer. 2010;10(1):376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4‐ALK fusion gene in non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448(7153):561‐566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shackelford RE, Vora M, Mayhall K, Cotelingam J. ALK‐rearrangements and testing methods in non‐small cell lung cancer: a review. Genes Cancer. 2014;5(1–2):1‐14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vidal J, Clavé S, de Muga S, et al. Assessment of ALK status by FISH on 1000 Spanish non‐small cell lung cancer patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9(12):1816‐1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pan Y, Zhang Y, Li Y, et al. ALK, ROS1 and RET fusions in 1139 lung adenocarcinomas: a comprehensive study of common and fusion pattern‐specific clinicopathologic, histologic and cytologic features. Lung Cancer. 2014;84(2):121‐126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim HR, Lim SM, Kim HJ, et al. The frequency and impact of ROS1 rearrangement on clinical outcomes in never smokers with lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(9):2364‐2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non‐small‐cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(350):2129‐2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.