Abstract

Background:

Headache diaries and recall questionnaires are frequently used to assess headache frequency and severity in clinical and research settings.

Methods:

Using 20 weeks of data from an intervention trial with 182 participants, we evaluated concordance between an electronic headache diary administered on a daily basis and designed to capture the presence and severity of headaches on an hourly basis (the headache diary) and a recall questionnaire, with retrospective estimation of the number of headache days assessed on a monthly basis. We further examined whether the duration or severity of headaches assessed by the electronic diary impacted concordance between these two measures.

Results:

Over the course of four 28-day periods, people with migraine participating in a dietary intervention reported an average of 13.7 and 11.1 headache days in the headache diary and recall questionnaire, respectively.

Conclusion:

Over time, the concordance between headache days reported in these two measures tended to increase; however, the recall questionnaire headache estimates were lower than the diary measures in all four periods. When analysis was restricted to headaches lasting 8 hours or more, the number of headache days was more closely aligned with days reported in the recall questionnaire, indicating that the accuracy of recall estimates is likely to be influenced by headache duration. Restriction of analyses to moderate-to-severe headaches did not change results as much as headache duration. The findings indicate that recall questionnaires administered on a monthly basis may underestimate headache frequency and therefore should not be used interchangeably with headache diaries.

Clinical Trials.gov Identifier:

Keywords: Migraine, headache, electronic diary, questionnaire, self-report, recall bias

Introduction

Self-reported measures of headache frequency and duration are considered to be the gold standard for measuring and understanding the burden of chronic headaches. The best way to ask about headache frequency and duration is unclear. Daily headache diaries – which can capture data on a daily, or even hourly, basis – are frequently used in clinical practice to follow trends in headache frequency and severity and their relationship to triggering factors such as the menstrual cycle and intermittent environmental exposures (1). This granular nature of headache diaries can potentially be leveraged in randomized controlled trials to more precisely capture effects of interventions on headache frequency and severity. Electronic diaries reduce error and are reportedly easy to use and less burdensome for study participants (2).

Previous research has suggested that headache frequency reported in daily headache diaries has high agreement with headache recall at 4 weeks (3), and that headache intensity may be a factor influencing reported headaches, with people more likely to remember severe compared to mild headaches (4). Researchers have compared diaries to questionnaire recall and found that recalled pain intensity is higher than average pain intensity reported in diaries (5). Retrospective overestimation of pain and underestimation of pain have both been documented in a variety of populations including chronic pain patients, patients undergoing surgery and research participants undergoing laboratory pain stimuli (6). However, none of these studies followed participants for repeated measurement over time. Hence, in the current study, we compared responses for four successive 4-week periods to the question “How many days in the past 4 weeks did you have a headache?” (the recall questionnaire), with a daily headache diary for the same periods.

The daily headache diary data were recorded each day by the same individuals in an electronic format designed to capture the presence and severity of headaches on an hourly basis (the headache diary).

Since the electronic daily headache diary captured the presence and severity of headaches on an hourly basis with short recall intervals, we considered headache diary data to be the gold standard in this study. We hypothesized that recall estimates of headaches over the previous 4 weeks (the recall questionnaire) would not differ from headache days summed from the daily diary. The completion and analysis of the recall questionnaire require less participant and researcher burden, respectively, compared to the daily headache diary. Therefore, if the daily diary and 4-week recall questionnaire demonstrate a high level of agreement as predicted, we would conclude that the recall questionnaire is preferable to daily diaries. However, if the daily headache diary and 4-week recall questionnaire estimates do not provide similar data, the conclusion would be that the more granular headache diary is preferable despite increased burden.

The aims of the present study are to assess: (1) Agreement between headache frequencies reported in the daily headache diary versus those estimated using the monthly recall questionnaire; (2) whether agreement between these two measures changes over the course of the 20-week study; and (3) whether participants are more likely to accurately recall severe or long-duration headaches compared to mild or brief headaches.

Materials and methods

Study design

This research is secondary data analysis of individuals enrolled in a randomized controlled dietary intervention trial for migraine.

All participants met International Headache Society criteria for migraine (7) and were under the care of a physician for migraine treatment.

For this secondary analysis, intervention groups were combined and all randomized participants were included.

Setting

The setting was a university hospital research center, with participants recruited from academic and private practice clinics in central North Carolina.

Participants

Participants were recruited from academic, private practice clinics, and the surrounding community. For more details about recruitment and participant screening, the published study protocol (8). Ethics approval was provided by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of North Carolina (IRB# 13–3284) and all participants provided written informed consent. Participants in the study included adults with 5–20 migraines per month with a history of migraines for two or more years who were willing to be randomized to intervention diets.

Participants were permitted to take migraine prevention and abortive medications and recorded the dose and frequency in the daily diary. Details are available in the published protocol.

Data sources and variables

Number of headache days: For the recall questionnaire, participants were asked “On how many days in the past 4 weeks did you have a headache? (if a headache lasted more than one day, count each day)”, at 4, 8, 14, and 20-week study visits. For the electronic headache diary, the number of headache days was calculated by summing the number of days with any headache in the 28 days immediately preceding administration of the recall questionnaire at each time point.

Participants were instructed to complete the electronic headache diary on the study website. This required reporting of headache presence and severity and medication use for a 24-hour period from midnight to midnight. Headaches were rated as mild, moderate or severe using a standard 10-point scale: mild (1–3), moderate (4–6), severe (7–10).

Statistical analyses

Number of days with headache in the past 28 days was calculated from the daily diary by creating a binary variable for each daily diary entry. This variable denoted whether the person experienced a headache or not on that day. The date of the questionnaire administration was paired with the matching headache diary date or the most recent entry prior to the date of questionnaire administration. Entries from 28 days prior to the visit were used to calculate a sum of headache days over the time period. If participants did not complete the diary on a day, headache frequency was calculated using the available data. For example, if a participant completed only 20 diary entries in a 28-day period, the corresponding headache frequency would reflect the proportion of headache days reported in the 20 days of completed entries. This number of headache days was compared with the headache days sum variable from the diary for the 28-day periods preceding each of the four time-points.

Completeness of data, mean, minimum, and maximum headache days and completed diary days were calculated. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (Cary, North Carolina).

After generating univariate statistics to summarize the data, we conducted three separate analyses for each study period. First, we calculated the mean difference between the two measures (diary vs. recall) with 95% CIs. We decided a priori that if the 95% CIs did not include zero, we would explore further using the Bland-Altman method. We visually examined the difference between the diary plotted against the recall response. To assess agreement between the two measures, we used the Bland-Altman method (9) to calculate the 95% limits of agreement (difference + 2* SD of the difference). We made the a priori decision that 95% limits of agreement that included a difference of ±10 headache days would be of clinical significance and indicate questionable reliability of the recall questionnaire.

Second, to test the hypothesis of no bias comparing the diary to questionnaire, we performed paired t-tests comparing the number of headache days reported using each measure. With a significance level set to 0.05, 95% confidence intervals that do not include the null value, representing no bias, would suggest that there is disagreement between the two measures.

Third, to compare headache frequency reported in the diary and by recall, we calculated both the Spearman rank correlation coefficients and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for each study period. We used a two-way mixed model with absolute agreement to calculate the ICC to assess between person differences. Since there is not an established cut-off point for test-retest reliability using the ICC (10) due to variability within the sample, we observed trends in the correlation coefficient and ICC over time and relied on the Bland-Altman analyses for assessing concordance.

Additional analyses

We assessed the possibility that headache duration or severity would contribute to agreement between the two measures. To test this hypothesis, we performed the same analysis described above using two different definitions of a headache day to capture a long duration headache and moderate-to-severe headache as reported in the diary. The two definitions of headache were as follows: Long-lasting headache was defined as headache lasting 8 hours or more regardless of the severity; moderate/severe headache was defined as headache rated moderate or severe and lasting at least 2 hours.

By measuring agreement over multiple 4-week intervals, we assessed recall ability among participants over the duration of a 20-week trial, in order to determine whether participants became more or less accurate over time at matching their self-report to their daily diaries.

Sensitivity analyses were performed using data restricted to participants who had complete data for all four time periods. Analyses were repeated using the diary time period of 30 days prior to the recall questionnaire as opposed to the 28 days. To understand how the proportion of diary days completed might impact the number of headache days reported in the diary, the proportion of headache days from the 28-day period was divided by the number of diary entries completed during that period by each participant. By multiplying this proportion of headache days by 28, we calculated the expected diary headache days based on the reported proportion of headache from the diary. We repeated analyses with this data from the diary.

Results

Participants

One hundred and thirty-one out of 182 people (72%) completed recall questions for all four study periods and had diary records for the corresponding time-frame. The final 4-week period included 135 participants (75% of the original sample) who remained in the study (see Supplemental Figure 1 for flowchart of study participation).

Descriptive data

The mean age of participants was 38.3 (SD = 12.0) years, 89% of the sample was female and 76% of the sample self-identified as white. The mean age of first headache onset was 16.6 (SD = 9.5) years (Table 1). Among included participants, compliance with the headache diary was very good, with 95% and 86% of the sample completing at least 20 entries during the first and last study periods, respectively. Over the course of the study, participants completed an average of 24.3 (SD = 4.5) days per 28-day period. Twenty-one people completed 14 or fewer entries in one or more study periods. This data was retained in the final sample.

Table 1.

Démographie and clinical information for the n = 182 study participants.

| Variable | n (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Sex | ||

| Female | 162 (89.0) | |

| Male | 20 (10.0) | |

| Race | ||

| White | 138 (75.8) | |

| Black | 33 (18.2) | |

| Other | 11 (6.0) | |

| Symptoms preceding headache* | ||

| Nothing (no aura) | 100 (54.9) | |

| Flashing lights | 44 (24.2) | |

| Other (blind spot, numbness, weakness) | 26 (14.3) | |

| Missing | 12 (6.5) | |

| Mean age of onset of first headache (years) | 16.6 (9.5) | |

| Mean HIT-6+ score | 62.7 (5.3) | |

| Age (years) | 38.3 (12.0) | |

| Number of headaches in an average week* | 3.7 (1.7) | |

| Medication use during study≠ | ||

| NSAIDs/acetaminophen | 135 (74.6) | |

| Triptans | 96 (53.0) | |

| Opioid | 10 (5.5) | |

| None | 4 (2.2) | |

Obtained from headache history self-report.

HIT-6: six-item Headache Impact Test (11).

Medication percent totals exceed 100% due to participants taking more than one type of medication.

Outcome data

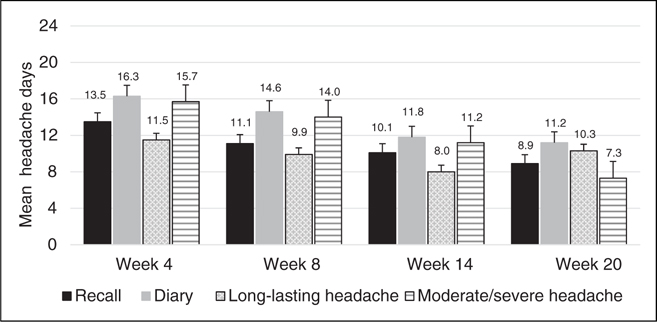

At the first assessment visit, 4 weeks after enrollment, daily diary entries showed an average of 16.3 headache days, compared with 13.5 headache days in the recall questionnaire (Figure 1). The mean difference between the diary and questionnaire was 2.8 (95% CI 1.9, 3.7) days, and the 95% limits of agreement between these two measures were −9.8 to 15.4 (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Comparison of mean headache days from the headache diary and recall questionnaire. Long-lasting headache: diary headache hours restricted to headaches lasting eight or more hours; moderate/severe headache: headache lasting two or more hours and reported as moderate or severe regardless of duration.

Table 2.

Results from comparison of 28 diary days with recall questionnaire.

| Week 4 | Week 8 | Week l4 | Week 20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| n | 182 | 159 | 150 | 135 |

| Diary mean (SD) | 16.3 (6.3) | 14.6 (6.6) | 11.8 (7.3) | 11.2 (7.6) |

| Number of diary days completed (SD) | 25.2 (3.3) | 24.7 (3.7) | 23.6 (5.0) | 23.5 (5.3) |

| Questionnaire mean (SD) | 13.5 (7.2) | ll.l (7.4) | 10.1 (7.9) | 8.9 (7.7) |

| Mean difference (95% CI) | 2.8 (l.9, 3.7)* | 3.4 (2.6, 4.2)* | 1.7 (0.7, 2.7)* | 2.2 (l.27, 3.2)* |

| SD | 6.3 | 5.2 | 6.2 | 5.7 |

| 95% limits of agreement | −10.0, 15.5 | −7.0, 13.8 | −10.7, 14.2 | −9.2, l3.7 |

| Min, Max difference | −13, 21 | −l2, l7 | −23, l9 | −l2, 2l |

| Spearman correlation | 0.53 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.69 |

| ICC+ (95% CI) | 0.51 (0.34, 0.63) | 0.65 (0.35, 0.80) | 0.65 (0.53, 0.74) | 0.69 (0.56, 0.79) |

| Long headache≠ | 11.5 (6.6) | 9.9 (6.7) | 8.0 (7.0) | l0.3 (7.6) |

| Moderate/severe headache§ | 15.7 (6.3) | 14.0 (6.6) | 11.2 (7.2) | 7.3 (7.2) |

p-value < 0.001 for paired t-test comparing mean headache days from the diary and questionnaire with the null hypothesis that there is no difference, indicating no bias.

ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient, calculated by two-way mixed model with absolute agreement; SD: standard deviation; CI: confidence interval.

Diary headache hours restricted to headaches lasting eight or more hours.

Headache lasting two or more hours and reported as moderate or severe regardless of duration.

Comparison of headache days

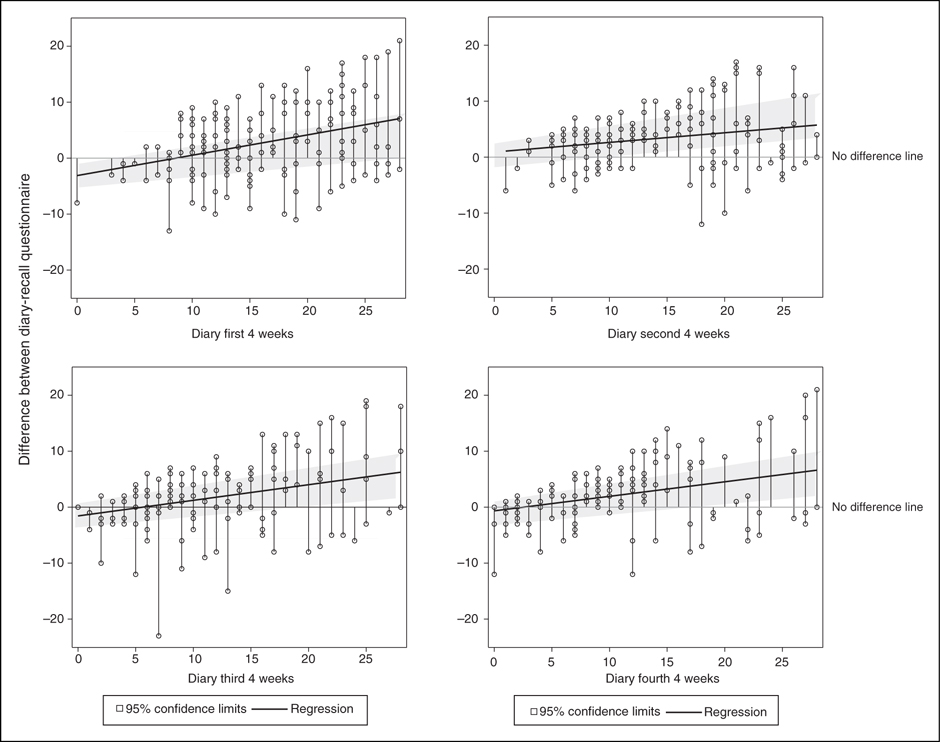

The recall questionnaire had questionable agreement with the daily diary, as evidenced by mean differences ranging from 1.7 to 3.4 days, 95% CIs that did not include the null value 0, and statistically significant p-values for all t-tests comparing means from the two methods of assessing headache days (Table 2). Assuming the diary as the gold standard indicator of whether or not a participant experienced a headache, 95% limits of agreement from the Bland Altman analyses showed poor agreement between the two measures, ranging from an underreporting of 23 headache days to an overreporting of 21 headache days (Figure 2). The enhanced Bland-Altman plots show the regression line estimating the difference between the diary and recall questionnaire with 95% confidence limits. The regression line crosses the “no difference line” (indicating perfect agreement between the diary and recall questionnaire) in the Bland-Altman plots for the first, third, and fourth 4-week periods but none show overlap in the no difference line and the regression line beyond day 11. The positive slope of the line shows increasing disagreement between the two methods as the number of headache days reported in the diary increased.

Figure 2.

Enhanced Bland-Altman plots comparing diary measure with difference between the diary and recall measures, regression line, and 95% confidence limits.

ICC values ranged from 0.51 to 0.69 with wide confidence intervals around the estimate. The ICC was lowest in the first 4-week period and highest in the last 4-week period, but the 95% confidence intervals for each measurement overlap (Table 2). The Spearman correlation coefficient followed the same pattern with a correlation coefficient of 0.54 for the first study period and 0.69 for the final study period.

Comparison of severe headache days

To determine the potential influence of headache duration and severity on accuracy of the recall questionnaire, we re-ran analyses with two different definitions of a “headache day” from the headache diary (see Figure 1). Identifying headache days based on duration (long-duration headache day defined as a day when headache was reported for eight or more hours), the mean number of headache days ranged from 8.0 to 11.5, which was closer to the headache days reported in the recall questionnaire and resulted in a lower estimate for all time periods except the week 20 visit, indicating this definition was not consistently similar to the recall questionnaire response. When a headache day was based on severity as a day with a headache lasting two or more hours and rated as moderate or severe, headache days ranged from 7.3 to 15.7. This was consistently higher than the recall questionnaire report with the exception of week 20, when long-duration headache days were lower compared to the recall questionnaire.

When the period of daily diary entries was extended from 28 to 30 days prior to the study visit, results were more extreme. The mean number of days completed in 30 days prior to the study visit was 26.6 (SD = 3.8). The mean differences between the diary and questionnaire responses ranged from 2.7 to 4.5 days, with the lowest mean difference in the third study period (see supplementary Table 1). As predicted, the upper limit of the 95% limits of agreement was increased by 2 days when the diary period was extended. The results of the inclusion of two additional days uniformly resulted in an increase of an average of one headache day, moving the diary average even further from the recall questionnaire response.

When diary headache days were calculated using the proportion of headache days in the reporting period ([number of headache days/number of diary entries completed]828), the diary mean increased by between 1.7 and 2.3 days, leading to a mean difference in the diary and questionnaire data of at least 4 days’ difference in reported headache in each time period (results shown in Supplementary Table 2).

Between 57% and 72% of individuals demonstrated higher diary headache days compared to the recall questionnaire when individual-level data was compared (results shown in Supplementary Table 3). Forty-seven people completing all periods of comparison had higher diary estimates compared to recall questionnaires in all four time periods (results shown in Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

The mean number of headache days estimated on a monthly basis using the recall questionnaire was substantially lower than the number of headache days captured on a daily basis with an electronic headache diary. Over the course of four 28-day periods, with retrospective estimation on a monthly basis, participants recalled an average of 1.7 to 3.4 fewer headache days when queried about the previous 4 weeks compared to summary data from an electronic headache diary. Thus, retrospective estimation can lead to clinically meaningful underestimation of headache frequency. Our findings indicate that recall questionnaires administered on a monthly basis may underestimate headache frequency and therefore should not be used interchangeably with headache diaries.

At every time point, participants reported fewer headache days on the questionnaire than they reported in their daily electronic headache diaries. Agreement increased slightly as the study went on, reflected by the increasing ICCs from 0.51 to 0.69, but there was not consistent improvement.

This study has the unique aspect of including a 4-week period of monitoring while participants were not receiving any study intervention. The first study period with the highest number of participants reflects the baseline period of data collection before participants were randomized to a dietary intervention, eliminating any potential for treatment to influence the observed findings as might happen once people were assigned to a study group.

These findings are important for several reasons. The validity of pain-recall ratings has been studied in many settings, but to our knowledge this is the first study to examine changes in agreement of headache-day measurements over a long period of time with multiple testing points.

Higher variability in pain levels has been shown in prior research to affect the recall of pain, while recalled pain levels tend to be higher than average momentary recordings (5,12). After 2 weeks of multiple daily pain reports, 68 chronic pain patients were asked to recall their pain and consistently overestimated their pain intensity, while individual differences in the magnitude of overestimation could be predicted based on pain variability (5).

McKenzie and Cutrer (3) compared survey questionnaires about headache frequency and intensity and diaries from 209 migraine patients with data in a Headache Electronic database. The authors found that patients reported an average of 14.7 days with headache on the questionnaire and 15.1 days with headache in the diary (p = 0.056). The authors reported that there was no change in the level of difference in headache frequency reported by the two methods as headache frequency increased. This finding supported the authors’ conclusion that headache frequency was captured adequately by survey compared to diaries. Our findings are inconsistent with this study in the difference between diary and recall as well as the magnitude of the difference. Potential reasons for this difference could be that the daily diaries in the prior study were handwritten, meaning they could have been completed at any time point, whereas in our study, participants completed the diary online with a time stamped entry and entries could not be completed more than 1 day retrospectively. Another limitation in McKenzie and Cutrer’s study was the exclusion of 90 participants due to missing or illegible questionnaires or diaries (3). Our use of electronic daily diaries prevented loss of paper forms or uninterpretable reporting due to handwriting.

In another study of 393 randomly selected adolescents, researchers found that participants were more likely to report headaches in headache diaries compared with interviews (13). Contrary to our findings, van den Brink and colleagues reported overestimation of headache frequency among a sample of 181 children aged 9 – 16 years completing 4 weeks of headache diary and a retrospective headache questionnaire. The authors found depression, age, and headache severity were associated with the size of recall error (14). Among 40 people reporting at least one headache a month, Niere and Jerak (15) compared daily headache diary with questionnaire response after 4 weeks. The authors concluded, based on Spearman rank correlation coefficients for headache frequency of 0.80, that the diary data had reasonably good agreement compared with recall questionnaire data. However, the mean number of headaches per month for the diary was 8.9 and the recall questionnaire mean was 6.7, indicating underestimation in the recall questionnaire.

Limitations

The largest limitation of the present study was the loss to follow-up during the study period. With the loss of 46 participants, people who remained in the study may have been more diligent in reporting headaches in the daily diary. Missing data in the daily diary is a limitation that could result in lower or higher proportion of headache days reported. It is important to acknowledge that we do not know if participants are more likely to complete the diary on days when they experienced a headache and not complete the diary on headache-free days.

Missing daily diary data could also impact counts of participants who remained in the study. However, if participants failed to submit their headache diary online, they were contacted the following afternoon with a reminder, and were allowed to enter diary data for the previous day. Participants were not able to view their headache data once they had successfully recorded it in the diary. This approach prevented participants from looking back at their headache diaries before answering the recall question estimating headache frequency. Low compliance with paper diaries has been well documented (16). The method of calculating the number of headache days used in this paper was dependent on high compliance in the daily diary and when calculation of headache days was defined by proportion of headache days, the number of headache days increased by 2 days. Shorter recall time periods may result in improved agreement between diary and recall measures. Researchers comparing daily pain ratings with 3-day, 7-day and 28-day among patients in a rheumatology practice found 7-day recall measures were highly correlated with daily measures (17).

Additionally, as this was a treatment study, there may be some treatment effect on headache reporting in the study groups. Our analysis was conducted with treatment group masked and not used as a variable, but it is possible that the number of headaches experienced was related to both treatment group and expectation of treatment. However, any such between-group differences should have no effect on comparisons of the two headache measures.

Generalizability

An important implication of our findings is that recall measures and daily headache diary reports may not be measuring the same construct. If people systematically underreport headache days when asked about the previous 28 days, it is vital to understand what may be driving this trend to determine if the issue is one of validity or bias. Validity refers to ratings that are not accurately reflective of the person’s experience while biased estimates are different due to another factor that impacts recollection of headache. Jensen’s work in this area has found bias from pain at the time of recall and the worst pain experienced during the recall period is small in 24-hour recall ratings in the post-surgical setting (18). Not all individuals reported higher headache days compared to recall measures, indicating there may be factors that influence this discrepancy. Anxiety and positive affect have been shown to predict memories of pain intensity and unpleasantness in a study of 313 women with headache (19). Thus, a logical next step is to measure anxiety and positive affect and determine if either of these variables explain the discrepancy between diary and recall measures.

Conclusion

Our findings are consistent with recommendations from Houle et al., based on 24,000 surveys of headache frequency for 15,976 participants, that use of daily diaries may improve accuracy and allow more precise estimates among people with chronic migraine (20). Based on the data from our sample of people with migraine who completed both daily diary monitoring and recall questionnaires, we conclude that the use of recall questionnaires led to meaningful underestimates of the number of headache days. Future treatment studies should be aware of discordance between diary measures and recall questionnaires and rely on diaries for more accurate reporting of headache days.

Supplementary Material

Clinical implications.

We evaluated agreement between an electronic daily headache diary and 4-week recall questionnaire asking about the number of headache days per month over four study visits with 16 weeks of daily diary entries.

The recall questionnaire underestimated headache frequency compared to the more granular daily headache diaries (mean differences ranged from 1.7 days to 3.4 days). Bland Altman analyses resulted in 95% limits of agreement from −10 to 15 days.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the study participants for their time and effort as well as the numerous staff involved in recruitment, data collection and project management during the original study. We also wish to acknowledge the Intramural Programs of the National Institute on Aging and Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by funding from the National Institute of Health’s (NIH) National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NICCH) grant RO1-AT007813-01A1. VM is supported by a Research Fellowship in Complementary and Integrative Healthcare (NIH NCCIH grant T32-AT003378).

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Nappi G, Jensen R, Nappi RE, et al. Diaries and calendars for migraine. A review. Cephalalgia 2006; 26: 905–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandarian-Balooch S, Martin PR, McNally B, et al. Electronic-diary for recording headaches, triggers, and medication use: Development and evaluation. Headache 2017; 57: 1551–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKenzie JA and Cutrer FM. How well do headache patients remember? A comparison of self-report measures of headache frequency and severity in patients with migraine. Headache 2009; 49: 669–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kikuchi H, Yoshiuchi K, Miyasaka N, et al. Reliability of recalled self-report on headache intensity: Investigation using ecological momentary assessment technique. Cephalalgia 2006; 26: 1335–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone AA, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE, et al. Variability of momentary pain predicts recall of weekly pain: A consequence of the peak (or salience) memory heuristic. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2005; 31: 1340–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salovey P, Smith AF, Turk DC, et al. The accuracy of memory for pain. Not so bad most of the time. APS J 1993; 2: 184–191. [Google Scholar]

- 7.The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004; 24: 9–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mann JD, Faurot KR, MacIntosh B, et al. A sixteen-week three-armed, randomized, controlled trial investigating clinical and biochemical effects of targeted alterations in dietary linoleic acid and n-3 EPA+DHA in adults with episodic migraine: Study protocol. Prostaglandins, Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2018; 128: 41–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bland JM and Altman DG. Measuring agreement in method comparison studies. Stat Meth Med Res 1999; 8: 135–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weir JP. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J Strength Cond Res 2005; 19: 231–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, Bjorner JB, et al. A six-item short-form survey for measuring headache impact: The HIT-6. Qual Life Res 2003; 12: 963–974. doi: 10.1023/a:1026119331193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stone AA, Broderick JE, Shiffman SS, et al. Understanding recall of weekly pain from a momentary assessment perspective: Absolute agreement, between- and within-person consistency, and judged change in weekly pain. Pain 2004; 107: 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krogh AB, Larsson B, Salvesen O, et al. Assessment of headache characteristics in a general adolescent population: A comparison between retrospective interviews and prospective diary recordings. J Headache Pain 2016; 17: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Brink M, Bandell-Hoekstra EN and Abu-Saad HH. The occurrence of recall bias in pediatric headache: A comparison of questionnaire and diary data. Headache 2001; 41: 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niere K and Jerak A. Measurement of headache frequency, intensity and duration: Comparison of patient report by questionnaire and headache diary. Physiother Res Int 2004; 9: 149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone AA, Shiffman S, Schwartz JE, et al. Patient non-compliance with paper diaries. BMJ 2002; 324: 1193–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broderick JE, Schwartz JE, Vikingstad G, et al. The accuracy of pain and fatigue items across different reporting periods. Pain 2008; 139: 146–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen MP, Mardekian J, Lakshminarayanan M, et al. Validity of 24-h recall ratings of pain severity: Biasing effects of “Peak” and “End” pain. Pain 2008; 137: 422–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babel P Memory of pain and affect associated with migraine and non-migraine headaches. Memory (Hove, England) 2015; 23: 864–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houle TT, Turner DP, Houle TA, et al. Rounding behavior in the reporting of headache frequency complicates headache chronification research. Headache 2013; 53: 908–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.