Abstract

Level of education can impact access to healthcare and health outcomes. Increasing rates of depression are a major public health concern, and vulnerability to depression is compounded for individuals with a lower level of education. Assessment of depression is integral to many domains of healthcare including primary care and mental health specialty care. This investigation examined the degree to which education influences the psychometric properties of self-report items that measure depressive symptoms. This study was a secondary data analysis of three large internet panel studies. Together, the studies included the BDI-II, CES-D, PHQ-9, and PROMIS measures of depression. Using a differential item functioning (DIF) approach, we found evidence of DIF such that some items on each questionnaire were flagged for DIF (i.e., different psychometric properties across education groups); effect sizes ranged, McFadden’s Pseudo R2 = .005 to .022. For example, education influenced psychometric properties for several double-barreled questions (i.e., questions that ask about more than one concept). Depression questionnaires vary in complexity, interacting with the respondent’s level of education. Measurement of depression should include consideration of possible educational disparities, to identify people who may struggle with a written questionnaire, or may be subject to subtle psychometric biases associated with education.

Keywords: education, depression, differential item functioning (DIF), self-report, assessment

Depression is a common and increasing public health concern (Vos et al., 2016). The lifetime risk for depression in US adults has previously been reported as 29.9% (Kessler, Petukhova, Sampson, Zaslavsky, & Wittchen, 2012). Individuals with lower levels of education face socioeconomic challenges, including poorer access to healthcare (Goldman & Smith, 2011). Therefore, individuals with lower educational attainment and depression are vulnerable on multiple levels— people with lower levels of education may have less access to screening and treatment for depression. Effective treatment begins with accurate and appropriate assessment. Thus, assessment should be precise and unbiased across levels of education. We investigated the influence of educational attainment on the psychometric properties of commonly used measures of depression. Simply stated, it is important to know how education affects individuals’ responses to questions about depression.

Educational Attainment, Depression, and Health Outcomes

The literature suggests many associations between depression and education. Unsurprisingly, higher rates of depression are observed among individuals with lower levels of education, relative to people with higher levels of education (Bauldry, 2015). Relatedly, several studies have demonstrated that a higher level of education is associated with lower levels of depression (Fletcher, 2010; Lorant et al., 2003). The connection between depression and education is likely bidirectional. Fletcher (2008) found that females with depressive symptoms are more likely to drop out of high school, not enroll in college, and are less likely to enroll in a 4-year college. Bjelland et al. (2008) found that a higher level of education was associated with lower levels of anxiety and depression over time. Moreover, having a psychiatric diagnosis in general has been associated with school termination from primary school through college (Breslau et al., 2009). It is important to note that the relationship between level of education and depression may be unique to the United States, as this association was not found in 11 other countries studied; this finding may be related to other sociodemographic factors such as gender (Andrade et al., 2003).

Level of education has been associated with overall health and well-being, including health conditions such as diabetes and hypertension. Interestingly, Mezuk, Eaton, Golden, and Ding (2008) found that education moderated the association between type II diabetes and major depressive disorder. Level of education is related to level of literacy, consistent with findings that both lower educational attainment and limited literacy significantly predict poorer knowledge about hypertension and poorer control of symptoms, with literacy having mediated the relationship between education and knowledge about one’s hypertension (Pandit et al., 2009). Thus, literacy and education have the potential to impact health outcomes, with education being a distal variable that influences factors that are more proximal to health, including literacy (and perhaps more specifically health literacy; Paasche-Orlow & Wolf, 2007). Importantly, education is negatively associated with higher mortality risk (Baker, Leon, Smith Greenaway, Collins, & Movit, 2011). For example, individuals with lower education have higher mortality risk related to worse kidney health, dialysis complications, and poorer kidney transplant outcomes (Green & Cavanaugh, 2015). Given the complex relationships among depression, health outcomes, and education, depression assessments should be accurate across levels of education.

Level of Education and Assessment

Educational attainment influences psychological assessment and self-reporting on questionnaires. This is widely known, such that standard cognitive assessments such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale IV (WAIS IV) provide supplemental scoring norms based on demographics such as level of education (Brooks, Holdnack, & Iverson, 2011). Among healthy adults, education moderated the association between depressive symptoms and performance on tests of immediate and delayed verbal memory. Individuals with greater educational attainment performed well regardless of depressive symptomology, but those with lower education and depression demonstrated poorer performance (McLaren, Szymkowicz, Kirton, & Dotson, 2015). Thus, accurate and equitable assessment in research and the clinic should consider the effect of educational attainment on individuals’ understanding of questionnaires.

Differential Item Functioning by Education

Differential Item Functioning (DIF) exists when there is a difference in the relationship between a questionnaire item and a construct (e.g., depression) across groups (e.g., more vs. less education). Previous studies that have examined DIF by education have illuminated potentially biased or problematic items in the questionnaire development process. For example, the Mini-Mental State Exam was found to include significant DIF by education for 4–5 items, which led to overestimation of cognitive errors for individuals with a lower level of education (Crane et al., 2006; Jones & Gallo, 2002; Murden, McRae, Kaner, & Bucknam, 1991; Ramirez, Teresi, Holmes, Gurland, & Lantigua, 2006). The Mattis Dementia Rating Scale was found to contain four items with DIF by education; one item demonstrated a large effect of DIF (digit span backwards; Teresi, Kleinman, & Ocepek-Welikson, 2000). Teresi et al. (2009) investigated DIF by several demographic factors including education for 32 PROMIS Depression items; one item demonstrated DIF by education such that individuals with higher education had a larger item slope. We built upon this prior work by examining PROMIS Depression and other items used to assess depression in the current study.

The Present Study

This study is unique because we had the opportunity to examine DIF in PROMIS measures as well as three other measures of depression. We hypothesized that DIF would be observed across levels of educational attainment for complex items on legacy measures of depression: the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). When an item is flagged for DIF, it means that one or more of its item response theory (IRT) parameters are not equivalent across groups, which may suggest the possibility of a problematic and/or biased item. In the context of education, we hypothesized that different levels of education might lead to non-equivalent understanding of the items, potentially undermining the precision of depression assessment across the full range of education. Legacy measures of depression often include complicated wording and long items, which may be difficult for people with lower education to comprehend, which in turn could make it difficult for them to choose a response option that matches their experience. Taple, Griffith, and Wolf (2019) found DIF by health literacy on a PROMIS Depression short form, such that individuals with limited health literacy had lower item slopes. Similarly, we hypothesized that individuals with lower educational attainment would have lower item slopes on items with DIF, meaning that the item is not as informative. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the broad impact of educational attainment on the PHQ-9, CES-D, BDI-II, and PROMIS Depression items using DIF analysis.

Methods

Participants

The present study included data from three internet panel samples (for details see Choi, Schalet, Cook, & Cella, 2014). All three samples were recruited by independent companies. The first sample, PROMIS 1 Wave 1 (N = 744; ages 18–88) was recruited by Polimetrix online. The second sample, was originally recruited for the calibration of NIH Toolbox (N = 748; ages 18–92) by Greenfield Online. Note that Greenfield Online is now called Toluna. Finally, the company Op4G recruited the third sample, PROsetta Stone (N = 1,104, ages 18–88).

Procedure

This study is a secondary data analysis of data from a study linking PROMIS to legacy measures of depression (see Choi et al., 2014 for details). This study was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. Participants completed a battery of measures online, mostly for the purpose of calibrating IRT parameters and examining other psychometric properties; the other measures are beyond the scope of the current investigation. The three samples included in the present study were recruited online from the general US population.

Measures

This study investigates the effect of education on four separate measures of depression – three questionnaires commonly used to assess depressive symptoms in the clinical setting, as well as items measuring depression from subsets of the NIH Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) item bank. Subsets from the PROMIS Depression item bank were administered to each sample, and included 28, 20, and 15 items, with fewer items selected to minimize participant burden. Fourteen PROMIS items were consistent across all three samples. Collectively we refer to the BDI-II, CES-D, and PHQ-9 as “legacy measures” of depression (Choi et al., 2014). Cronbach’s alpha for all four measures of depression have been previously reported as exceeding 0.9 (Choi et al., 2014). Table 1 presents a detailed breakdown of which measures were administered to each sample.

Table 1.

Measures Administered by Sample

| Measures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Sample | PROMIS Depression (Cella et al., 2010) | BDI-II (Beck et al., 1996) | PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001) | CES-D (Radloff, 1977) |

|

| ||||

| NIH Toolbox Calibration | X (20 items) | X | X | |

|

| ||||

| PROMIS 1 Wave 1 | X (28 items) | X | ||

|

| ||||

| PROsetta Stone | X (15 items) | X | ||

Note.

indicates that the measure was administered to the sample

Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II).

The BDI-II is a questionnaire that assesses symptoms of depression. It contains 21 items (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), each with response options ranging from 0 to 3; each response option contains the full item stem, in addition to the severity or frequency of the symptom. For example, the response options for an item assessing sadness include: “0: I do not feel sad; 1: I feel sad much of the time; 2: I am sad all the time; 3: I am so sad or unhappy that I can’t stand it” (Beck et al., 1996). Respondents are instructed to endorse the option that describes their experiences over the past two weeks. Internal consistency for the BDI-II has been previously described as Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .73 to .92 for non-clinical populations (Dozois, Dobson, & Ahnberg, 1998).

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).

The CES-D was designed for depression assessment in the general population (Choi et al., 2014; Zimmerman & Coryell, 1994). The CES-D is comprised of 20 items (Radloff, 1977). Possible responses range from 0 (Rarely or none of the time) to 3 (Most or all of the time). Internal consistency has been reported at Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85 in the general population, and other studies have supported its construct validity (Radloff, 1977; Zimmerman & Coryell, 1994).

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).

The PHQ-9 is used frequently in mental health settings as well as in primary care. The PHQ-9 consists of nine items based on the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode. Each item has four possible response options, 0 (Not at all) to 3 (Nearly every day). Internal consistency of the PHQ-9 has been previously reported with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .86 to .89 (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001). The PHQ-9 has demonstrated high criterion validity when compared to clinical interviews by mental health professionals (Kroenke et al., 2001).

PROMIS Depression.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) supported the development of the PROMIS system of standardized assessments of patient-reported outcomes (PROs; Cella et al., 2007, 2010; Fries, Bruce, & Cella, 2005; Hays, Bjorner, Revicki, Spritzer, & Cella, 2009; Liu et al., 2010). PROMIS has item banks for computer adaptive testing, as well as static short forms created from the item banks. For depression the items are rated on a five-point frequency scale with response options from 1 (never) to 5 (always; Pilkonis et al., 2011). The depression item bank includes items such as, “In the past 7 days…I felt worthless” and “In the past 7 days…I felt I had nothing to look forward to.” Scores are expressed as T scores. Internal consistency of PROMIS Depression scales has been reported, Cronbach’s alpha = .95. Moreover, convergent validity with the CES-D has been previously reported as r = .83 (Pilkonis et al., 2011).

Differential Item Functioning (DIF)

DIF analysis is a method used to statistically quantify whether group membership (e.g., level of education) affects the relationship that a questionnaire item has with the construct it measures (e.g., depression). One method for detecting DIF is Item Response Theory (IRT; Cho, Suh, & Lee, 2016). If DIF is present, an item has different IRT properties across groups, even at the same level of the latent construct (Reeve & Fayers, 2005; Shealy & Stout, 1993). In the current analyses, if an item shows DIF, then the level of depression may be under- or overestimated in individuals with a lower level of education. It is important to note that DIF with small effect size for individual items can cumulatively affect the entire test or measure (Shealy & Stout, 1993). Discrepancies at the test level can influence construct validity, such that interpretations across groups may be inaccurate (Taple et al., 2019).

Analytical Strategy

Descriptive statistics were conducted with the pastecs package (Grosjean & Ibanez, 2014) in R (R Core Team, 2013). DIF analyses were carried out for each item from the measures described above, in each sample separately, using the lordif package in R (Choi, Gibbons, & Crane, 2011). A similar methodology was used and recommended by Taple et al. (2019). lordif employs a graded response model (GRM), a type of IRT model, which was well suited to the measures in this study because each item had several ordinal response options (Reeve & Fayers, 2005; Samejima, 2016). Within lordif, items were flagged for DIF based on McFadden’s pseudo R2. Given concerns about Type 1 errors with chi-square detection tests (Choi et al., 2011), we opted for McFadden’s pseudo R2, an indicator of effect size.

DIF analyses were conducted using three levels of education: high school and below, some college or technical school, and college graduate and above. Educational attainment was split into these three groups so that each education group comprised roughly one-third of each sample. We used effect sizes rather than statistical significance to determine the presence and magnitude of DIF. McFadden’s pseudo R2 was used to indicate the cutoff for flagging items for DIF. We chose to analyze DIF with cutoffs specifically chosen for each sample and measure. To determine the final cutoffs, we ran DIF across a wide range of effect sizes then inspected the output for where the number of items flagged for DIF stabilized. We then chose the largest (i.e., the most stringent) effect size where the number of items flagged remained consistent. That chosen effect size was used to determine how many items were flagged for each scale in each sample. The cutoffs used in the present study are larger than cutoffs determined by Monte Carlo simulations, which create a distribution of observed effect sizes based on a no-DIF null hypothesis. Thus, our observed effect sizes are more conservative than the results of the Monte Carlo simulations, because the simulations determine the minimum effect size that would be considered indicative of DIF.

Using the procedure described above, the cutoffs used to determine if an item would be flagged for DIF were selected for each measure in each sample. Effect size cutoffs by sample and measures are detailed in Table 2. If an item had an effect size larger than the appropriate cutoff, it was flagged for DIF. It is important to distinguish the McFadden Pseudo R2 cutoffs listed here from the observed pseudo R2 values from the DIF analyses (see results below); the latter pseudo R2 values are the observed impact of DIF (i.e., the observed impact of education on IRT parameters for depression items).

Table 2.

McFadden Pseudo R2 Cutoffs by Sample and Measure

| Measure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Sample | PROMIS Depression | BDI-II | PHQ-9 | CES-D |

|

| ||||

| NIH Toolbox Calibration | .009 | - | .004 | .010 |

| PROMIS 1 Wave 1 | .007 | - | - | .008 |

| PROsetta Stone | .008 | .010 | - | - |

Note.

indicates that the measure was not administered in that sample

We examined IRT parameters across groups for all items flagged for DIF. Looking at the IRT parameters visually with item characteristic curves (ICCs) provides additional information about the nature of the DIF for that item. ICCs are determined by two types of IRT parameters – item slopes and item thresholds. Item slopes indicated how strongly an item relates to the construct (depression in this case) for each group. Item thresholds demonstrate the level of the construct (i.e., depression) for someone from an educational group to choose a particular response to the item. We examined ICCs for all items flagged for DIF.

As described above, we hypothesized that people with a lower level of education would have lower item slopes. We anticipated that the particular items flagged in this way would require a higher level of vocabulary. Therefore, we conducted several post-hoc readability analyses, using the readability package in R (Rinker, 2017), to gain more information about the various measures of depression. These commonly used readability statistics demonstrate the average grade level required to read a passage (Coleman & Liau, 1975; Flesch, 1948; Gunning, 1952; McLaughlin, 1969; Smith & Senter, 1967).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics of demographics for each sample are displayed in Table 3. Level of education was evenly dispersed across all samples. In the NIH Toolbox sample, age ranged from 18 to 92 years (Mean ± SD = 47.2 ± 15.2). Fifty six percent of the Toolbox participants identified as female. PROMIS 1 Wave 1 participants ranged in age from 18 to 88 years (Mean ± SD = 51.0 ± 18.8). Roughly half of the sample (52%) was female. Lastly, the PROsetta Stone sample comprised individuals from ages 18 to 88 years (Mean ± SD = 46.3 ± 17.5). Fifty two percent of the PROsetta Stone participants were female.

Table 3.

Sample Characteristics

| NIH Toolbox N = 748 | PROMIS 1 Wave 1 N = 744 | PROsetta Stone N = 1104 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age, Mean (SD) | 47.2 (15.2) | 51.0 (18.8) | 46.3 (17.5) |

| Gender, N (%) | |||

| Male | 328 (44) | 357 (48) | 528 (48) |

| Female | 420 (56) | 386 (52) | 576 (52) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Education, N (%) | |||

| High school or less | 205 (27) | 171 (23) | 465 (42) |

| Some college/technical school | 326 (44) | 334 (45) | 305 (28) |

| College graduate or above | 217 (29) | 239 (32) | 334 (30) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic/Non-Latinx | 634 (85) | 670 (90) | 929 (84) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 114 (15) | 70 (9) | 175 (16) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 4 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Race, N (%) | |||

| White/Caucasian | 585 (78) | 592 (80) | 793 (72) |

| Black/African American | 67 (9) | 72 (10) | 124 (11) |

| Asian | 16 (2) | 3 (<1) | 58 (5) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 13 (2) | 6 (<1) | 7 (1) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 5 (1) | 0 (0) | 7 (1) |

| Biracial/Multiracial | 16 (2) | 71 (10) | 33 (3) |

| Other | 46 (6) | N/A | 82 (7) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Differential Item Functioning (DIF)

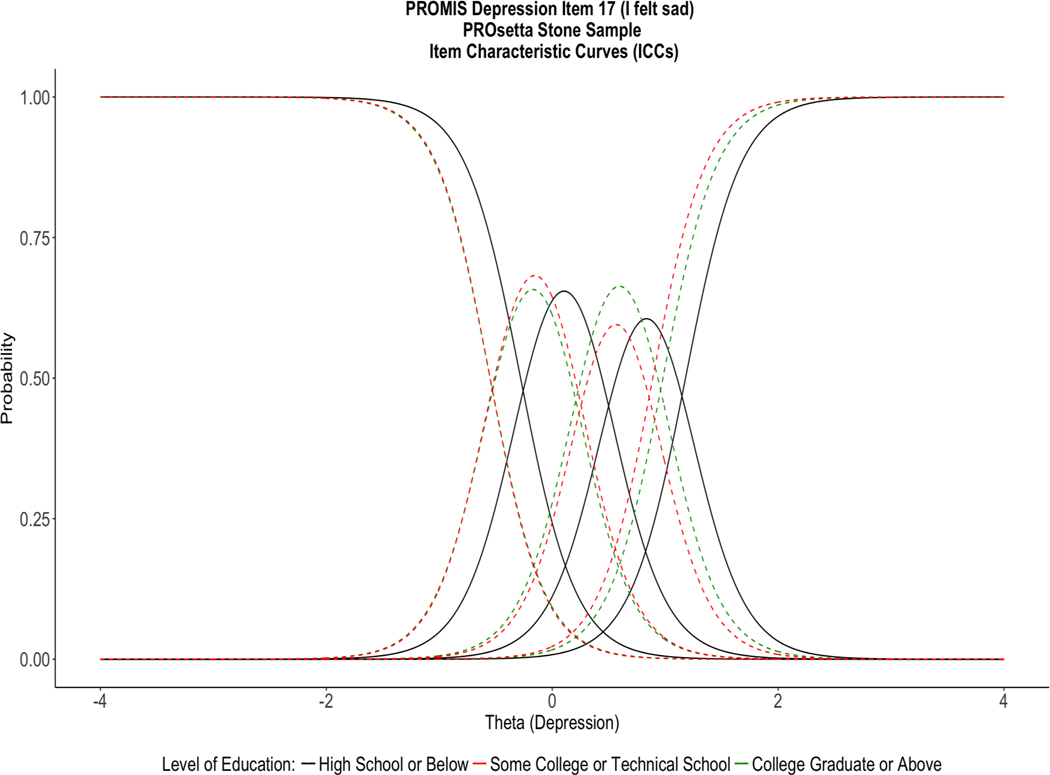

At least one item on each questionnaire in each sample showed DIF. Effect sizes for all items flagged for DIF are displayed in Table 4. Content of item stems for all items flagged for DIF is presented in Table 5. Of the measures administered in the NIH Toolbox sample, PROMIS Depression had one item with DIF, two items on the PHQ-9 were flagged, and one item on the CES-D (item 17; “I had crying spells”) demonstrated DIF with the largest effect size of items flagged in this sample (R2 = .017). In the PROMIS 1 Wave 1 sample, PROMIS Depression demonstrated four items with DIF, and the CES-D showed five items with DIF. Again, one of the items flagged on the CES-D (item 10; “I felt fearful”) had the largest effect size (R2 = .022). One item from the BDI-II was flagged for DIF in the third sample, PROsetta Stone, and four items from PROMIS Depression. One of the items flagged from PROMIS Depression (item 17; “In the past 7 days, I felt sad”) had the largest effect size in this sample (R2 = .02). ICCs for these items with the largest effect sizes in each sample are displayed in Figures 1a–1c.

Table 4.

Differential Item Functioning (DIF) Results

| Measure | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Sample | PROMIS Depression | BDI-II | PHQ-9 | CES-D | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Item # | R 2 | Item # | R 2 | Item # | R 2 | Item # | R 2 | |

|

| ||||||||

| NIH Toolbox Calibration | 46 | .01 | - | - | 5 8 |

.005 .007 |

17 | .017 |

|

| ||||||||

| PROMIS 1 Wave 1 | 4 9 14 22 |

.009 .008 .009 .01 |

- | - | - | - | 1 2 10 15 19 |

.011 .013 .022 .011 .013 |

|

| ||||||||

| PROsetta Stone | 17 26 36 45 |

.02 .011 .013 .008 |

9 | .012 | - | - | - | - |

Note. Numbers displayed are the McFadden Pseudo R2 effect sizes for each item flagged for DIF. – indicates that the measure was not administered in that sample. Item # refers to which items from each questionnaire were flagged for DIF.

Table 5.

Item Stems of Items Flagged for DIF

| Measure | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Sample | PROMIS Depression | BDI-II | PHQ-9 | CES-D | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Item # | Stem | Item # | Stem | Item # | Stem | Item # | Stem | |

|

| ||||||||

| NIH Toolbox Calibration | 46 | I felt pessimistic | - | - | 5 | Poor appetite or overeating | 17 | I had crying spells |

|

| ||||||||

| 8 | Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed? Or the opposite - being so fidgety or restless that you have been moving around a lot more than usual | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| PROMIS 1 Wave 1 | 4 | I felt worthless | - | - | - | - | 1 | I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me |

|

|

|

|||||||

| 9 | I felt that nothing could cheer me up | 2 | I did not feel like eating; my appetite was poor | |||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| 14 | I felt that I was not as good as other people | 10 | I felt fearful | |||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| 22 | I felt like a failure | 15 | People were unfriendly | |||||

|

|

||||||||

| 19 | I felt that people disliked me | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| PROsetta Stone | 17 | I felt sad | 9 | [0 = I don’t have any thoughts of killing myself. 1 = I have thoughts of killing myself, but I would not carry them out. 2 = I would like to kill myself. 3 = I would kill myself if I had the chance] | - | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||||

| 26 | I felt disappointed in myself | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 36 | I felt unhappy | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 45 | I felt that nothing was interesting | |||||||

Note. – indicates that the measure was not administered in that sample. Item # refers to which items from each questionnaire were flagged for DIF. Item content is included in the response options for the BDI-II.

Figure 1a.

Item characteristic curves (ICCs) for PROMIS Depression Item 17. Theta, displayed on the X axis, is the depression metric transformed to a standardized scale (Mean = 0, SD = 1). The Y axis shows the probability of response type. As shown the curves are non-overlapping across groups.

Figure 1c.

Item characteristic curves (ICCs) for CES-D Item 10. Theta, displayed on the X axis, is the depression metric transformed to a standardized scale (Mean = 0, SD = 1). The Y axis shows the probability of response type. Thresholds are collapsed when fewer than five participants use certain response categories.

DIF findings were as follows. In the Toolbox Calibration sample, the ICCs for PROMIS Depression Item 46 (EDDEP46) and PHQ-9 items 5 and 8 showed that individuals with the highest level of education (college graduate or above) had steeper item slopes than the other two education groups, and thresholds varied. Similarly, BDI-II Item 9 in the PROsetta Stone sample showed that individuals with the highest level of education had steeper item slopes. In contrast, the ICCs for the items flagged for DIF in the PROMIS 1 Wave 1 sample, with the exception of PROMIS Depression Item 9 (EDDEP9) and CES-D Item 2, showed that individuals with the lowest level of education had the steepest item slopes. Within PROsetta Stone, slopes of PROMIS items flagged for DIF showed mixed results, varying in strength among the groups. Three of the four PROMIS items flagged demonstrated that individuals with a high school education or below had higher response thresholds than the other two educational groups.

Post-hoc Readability Analyses

We found that the PHQ-9, as shown by readability indices, requires the highest reading level of the questionnaires studied. The BDI-II also required a high reading level across most indices. High readability scores indicate that a higher reading level is needed to understand the item. Readability analyses are presented in detail in Table 6. The CES-D demonstrated moderate difficulty based on readability statistics. Readability analyses revealed low to moderate difficulty of PROMIS Depression items.

Table 6.

Readability Statistics Findings

| Statistic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Measure | Flesch-Kincaid | Gunning-Fog Index | Coleman-Liau | SMOG | Automated Readability Index | Average Grade Level |

|

| ||||||

| BDI-II | 3.8 | 7.0 | 3.2 | 8.2 | 0 | 4.4 |

|

| ||||||

| CES-D | 2.0 | 4.7 | 2.5 | 6.4 | 0 | 3.1 |

|

| ||||||

| PHQ-9 | 5.6 | 7.4 | 8.8 | 8.4 | 5 | 7.0 |

|

| ||||||

| PROMIS Depression(15 items) | 1.5 | 4.5 | 3.1 | 6.0 | 0 | 3.0 |

|

| ||||||

| PROMIS Depression (20 items) | 2.0 | 4.9 | 3.9 | 6.4 | 1 | 3.6 |

|

| ||||||

| PROMIS Depression (28 items) | 1.9 | 4.8 | 3.2 | 6.1 | 0 | 3.2 |

Note. Numbers indicate estimated grade level required to read and comprehend the text

Discussion

Across all samples, on several items flagged for DIF, individuals with high school education or below (the lowest educational attainment category) had higher item slopes than the other two education groups. Teresi et al. (2009) found a similar item slope pattern on one PROMIS Depression item that demonstrated DIF by education. For individuals with higher levels of education, some items with DIF had lower item slopes (e.g., EDDEP 14: “I felt that I was not as good as other people”). It is possible that individuals with high education spent more time thinking about the content of the items leading to more variability in interpretation of the items. In contrast, perhaps individuals with lower education took a more literal interpretation. The pattern of DIF was not always in a consistent direction, however. Some items were flagged for DIF with individuals with the highest level of education (college or above) having the steepest item slopes. For example, PHQ-9 item 5 asks about “poor appetite or overeating”– opposite responses within one item. For these items, it is likely that responses for people with higher education are more closely related to their level of depression because they were able to understand these items more clearly than people with less educational attainment.

In the present study, items with DIF had small effect sizes. These small effect size can have a cumulative effect, however, on overall survey scores (Crane et al., 2007). If one looks at the proportion of items flagged, PROMIS does as well or better than legacy measures of depression in terms of equitable assessment across levels of education. In other words, PROMIS items were flagged for DIF at the lowest rate. Moreover, in the PROsetta Stone sample, the IRT parameters (i.e., slope and thresholds) of the PROMIS items flagged for DIF were large in an absolute sense, and relative to BDI-II item 9. Despite being flagged for DIF, this finding indicates that these PROMIS items were closely related to the latent construct of depression.

At the item level, educational attainment impacted participant responses on at least one item for each measure in all three samples. Given that DIF was found across all measures and that there is wide variability within levels of education, health literacy may have a stronger influence on IRT parameters than education for items measuring depression (e.g., Paasche-Orlow & Wolf, 2007; Taple et al., 2019). For instance, all 4-year college programs do not consist of equivalent content – there is likely different coverage of depression, for example, in a psychology major versus an engineering or fine-arts major. Thus, people within the college graduate and above education stratum could vary in their exposure to health information including depression. Nonetheless, these findings demonstrate that examining questionnaires for DIF can be a valuable tool to illuminate items that are challenging for some respondents, as well as items that are subject to variable interpretation. Researchers and clinicians should be cognizant of the effects of level of education on questionnaire responses, especially when new questionnaires are being developed and psychometric analyses are being used to select and remove items.

Of note, items 5 and 8 on the PHQ-9 were flagged for DIF in the NIH Toolbox Calibration sample; both items are double-barreled, meaning that the item asks about two separate concepts within a single item. In the field of test development there is wide consensus that double-barreled items are problematic, and should be avoided, because they can evoke confusion (Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, 2014). Moreover, different responders may focus on different aspects of the item (Gehlbach, 2015; Gideon, 2012; Sinkowitz-Cochran, 2013). In addition to DIF, we also examined the difficulty of items with readability analyses. It is worth noting that readability analyses are intended to evaluate larger blocks of texts, rather than single statements like a survey item, and do not consider the context of reading or individual differences in reading. Nonetheless, it was interesting to compare these findings with the DIF analyses. PROMIS Depression items in the NIH Toolbox sample were flagged for DIF at the lowest rate (in terms of total number of items on the questionnaire), which was consistent with PROMIS items being easier to read than the other questionnaires according to readability indices. Moreover, because readability analyses may fail to detect certain problems, it is helpful to use psychometric tools (e.g., DIF analysis) as a context and person-sensitive adjunctive tool for evaluating questionnaires items used in healthcare.

Our findings have implications for clinical practice. The legacy measures studied are widely used in clinical settings. If questionnaires have several items with DIF, this sets the stage for inaccurate assessment of depressive symptoms in patients with lower educational attainment. Downstream, depression questionnaires have the potential to influence referrals to specialty care, diagnostic decisions, treatment planning, and the assessment of change during treatment. DIF methodology is informative for any clinical assessment, given that respondents (e.g., patients) are likely to have a range of education. Questionnaires should be equally applicable across levels of education, so that all individuals may be accurately assessed. The fact that DIF by education is observed for all depression measures in this study suggests that the overall experience of completing the questionnaire may also be different (e.g., perhaps people with low levels of education find the questionnaires more intimidating); this should be assessed in future studies so that comfort as well as accuracy during questionnaire testing is maintained.

Limitations and Future Directions

We acknowledge that this study had limitations. First, the three samples were Internet based, and thus, were self-selecting and subject to the sampling procedures used by the panel companies. Second, the number of PROMIS Depression items, and thereby the content of some items, was not consistent across the three samples. Third, although several racial groups were represented in this research, the samples were predominantly White. Efforts should be made to recruit more diverse samples in future research to ensure that effects are generalizable. Fourth and finally, the Internet panels were individuals from the general US population. Effects of DIF may be even greater in a clinical sample (e.g., patients with major depression), and different results may be obtained in other countries. Future studies that investigate the impact of education on questionnaires assessing symptoms of depression in a sample with more moderate to severe symptomatology would be informative.

Future research can explore other methods for analyzing DIF. It may be useful to examine and compare the IRT parameters of different measures (e.g., PROMIS Depression compared to PHQ-9). It is possible, for example, that even if more PROMIS Depression items were flagged for DIF, PROMIS Depression as a questionnaire may be more strongly related to the construct of depression (e.g., larger item slopes). Ideally, questionnaire items would be free of DIF with large item slopes.

Conclusion

All measures displayed DIF by education for at least one item. Overall, findings were mixed such that item slopes were sometimes higher for individuals with high school education or below; for other items slopes were lower for people with less educational attainment. Therefore, depending on the item content, some items are less informative of a person’s actual symptoms depending on their level of educational attainment. Level of education needs to be considered during development and administration of instruments measuring depression. DIF is a useful tool to indicate which items may be more difficult for individuals with lower educational attainment.

Figure 1b.

Item characteristic curves (ICCs) for CES-D Item 17. Theta, displayed on the X axis, is the depression metric transformed to a standardized scale (Mean = 0, SD = 1). The Y axis shows the probability of response type. Thresholds are collapsed when fewer than five participants use certain response categories.

References

- Andrade L, Caraveo-Anduaga JJ, Berglund P, Bijl RV, De Graaf R, Vollebergh W, … Wittchen HU (2003). The epidemiology of major depressive episodes: Results from the International Consortium of Psychiatric Epidemiology (ICPE) Surveys. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 12(1), 3–21. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12830306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DP, Leon J, Smith Greenaway EG, Collins J, & Movit M. (2011). The education effect on population health: A reassessment. Population and Development Review, 37(2), 307–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00412.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauldry S. (2015). Variation in the protective effect of higher education against depression. Society and Ment Health, 5(2), 145–161. doi: 10.1177/2156869314564399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bjelland I, Krokstad S, Mykletun A, Dahl AA, Tell GS, & Tambs K. (2008). Does a higher educational level protect against anxiety and depression? The HUNT study. Social Science & Medicine, 66(6), 1334–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Miller E, Breslau N, Bohnert K, Lucia V, & Schweitzer J. (2009). The impact of early behavior disturbances on academic achievement in high school. Pediatrics, 123(6), 1472–1476. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks BL, Holdnack JA, & Iverson GL (2011). Advanced clinical interpretation of the WAIS-IV and WMS-IV: Prevalence of low scores varies by level of intelligence and years of education. Assessment, 18(2), 156–167. doi: 10.1177/1073191110385316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SJ, Suh Y, & Lee WY (2016). After differential item functioning is detected: IRT item calibration and scoring in the presence of DIF. Applied Psychological Measurement, 40(8), 573–591. 10.1177/0146621616664304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SW, Schalet B, Cook KF, & Cella D. (2014). Establishing a common metric for depressive symptoms: Linking the BDI-II, CES-D, and PHQ-9 to PROMIS depression. Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 513–527. doi: 10.1037/a0035768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M, & Liau TL (1975). A computer readability formula designed for machine scoring. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(2), 283–284. doi: 10.1037/h0076540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crane PK, Gibbons LE, Jolley L, van Belle G, Selleri R, Dalmonte E, & De Ronchi D. (2006). Differential item functioning related to education and age in the Italian version of the Mini-Mental State Examination. International Psychogeriatrics, 18(3), 505–515. doi: 10.1017/S1041610205002978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman DA, Smyth JD, & Christian LM (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DJ, Dobson KS, & Ahnberg JL (1998). A psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory–II. Psychological Assessment, 10(2), 83–89. 10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.83 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flesch R. (1948). A new readability yardstick. Journal of Applied Psychology, 32(3), 221–233. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18867058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JM (2010). Adolescent depression and educational attainment: Results using sibling fixed effects. Health Economics, 19(7), 855–871. doi: 10.1002/hec.1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlbach H. (2015). Seven survey sins. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 35(5–6), 883–897. doi: 10.1177/0272431615578276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gideon L. (2012). The art of question phrasing. In Handbook of survey methodology for the social sciences (pp. 91–107). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman D, & Smith JP (2011). The increasing value of education to health. Social Science & Medicine, 72(10), 1728–1737. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JA, & Cavanaugh KL (2015). Understanding the influence of educational attainment on kidney health and opportunities for improved care. Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease, 22(1), 24–30. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning R. (1952). The technique of clear writing. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Jones RN, & Gallo JJ (2002). Education and sex differences in the Mini-Mental State Examination: Effects of differential item functioning. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57(6), P548–P558. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.P548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Wittchen H-U (2012). Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 21(3), 169–184. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JBW (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorant V, Deliege D, Eaton W, Robert A, Philippot P, & Ansseau M. (2003). Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157(2), 98–112. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12522017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren ME, Szymkowicz SM, Kirton JW, & Dotson VM (2015). Impact of education on memory deficits in subclinical depression. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 30(5), 387–393. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acv038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin GH (1969). SMOG grading: A new readability formula. Journal of Reading, 12(8), 639–646. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40011226 [Google Scholar]

- Murden RA, McRae TD, Kaner S, & Bucknam ME (1991). Mini-Mental State exam scores vary with education in Blacks and Whites. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 39(2), 149–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01617.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paasche-Orlow MK, & Wolf MS (2007). The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. American Journal of Health Behavior, 31 Suppl 1, S19–26. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.supp.S19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandit AU, Tang JW, Bailey SC, Davis TC, Bocchini MV, Persell SD, … Wolf MS (2009). Education, literacy, and health: Mediating effects on hypertension knowledge and control. Patient Education and Counseling, 75(3), 381–385. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez M, Teresi JA, Holmes D, Gurland B, & Lantigua R. (2006). Differential item functioning (DIF) and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE): Overview, sample, and issues of translation. Medical Care, 44(11, Suppl 3). doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000245181.96133.db [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeve BB, & Fayers P. (2005). Applying item response theory modeling for evaluating questionnaire item and scale properties. In Assessing quality of life in clinical trials: Methods of Practice (pp. 55–73). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rinker T. (2017). Readability: Tools to calculate readability scores (Version 0.1.0) [Software]. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.31950 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samejima F. (2016). Graded Response Models. In Handbook of Item Response Theory (Vol. 1: Models, pp. 95–107). CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shealy R, & Stout W. (1993). A model-based standardization approach that separates true bias/DIF from group ability differences and detects test bias/DTF as well as item bias/DIF. Psychometrika, 58(2), 159–194. doi: 10.1007/bf02294572 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkowitz-Cochran RL (2013). Survey design: To ask or not to ask? That is the question…. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 56(8), 1159–1164. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EA, & Senter RJ (1967). Automated readability index. AMRL TR, Aerospace Medical Research Laboratories (US), 1–14. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5302480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taple BJ, Griffith JW, & Wolf MS (2019). Interview administration of PROMIS depression and anxiety short forms. Health Literacy Research and Practice, 3(3), e196–e204. 10.3928/24748307-20190626-01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teresi JA, Kleinman M, & Ocepek-Welikson K. (2000). Modern psychometric methods for detection of differential item functioning: Application to cognitive assessment measures. Statistics in Medicine, 19(11–12), 1651–1683. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10844726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, … Incidence, G. D. I. (2016). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet, 388(10053), 1545–1602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, & Coryell W. (1994). Screening for major depressive disorder in the community: A comparison of measures. Psychological Assessment, 6(1), 71–74. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.1.71 [DOI] [Google Scholar]