Abstract

Despite treatment advances, patients with multiple myeloma (MM) often progress through standard drug classes including proteasome inhibitors (PIs), immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), and anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). LocoMMotion (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04035226) is the first prospective study of real-life standard of care (SOC) in triple-class exposed (received at least a PI, IMiD, and anti-CD38 mAb) patients with relapsed/refractory MM (RRMM). Patients (N = 248; ECOG performance status of 0–1, ≥3 prior lines of therapy or double refractory to a PI and IMiD) were treated with median 4.0 (range, 1–20) cycles of SOC therapy. Overall response rate was 29.8% (95% CI: 24.2–36.0). Median progression-free survival (PFS) and median overall survival (OS) were 4.6 (95% CI: 3.9–5.6) and 12.4 months (95% CI: 10.3–NE). Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported in 83.5% of patients (52.8% grade 3/4). Altogether, 107 deaths occurred, due to progressive disease (n = 74), TEAEs (n = 19), and other reasons (n = 14). The 92 varied regimens utilized demonstrate a lack of clear SOC for heavily pretreated, triple-class exposed patients with RRMM in real-world practice and result in poor outcomes. This supports a need for new treatments with novel mechanisms of action.

Subject terms: Myeloma, Targeted therapies

Introduction

Despite advances in medical treatment that have improved survival, multiple myeloma (MM) remains incurable [1]. Most patients with MM eventually progress or become refractory to treatment with standard drug classes including proteasome inhibitors (PIs), immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), and others [2]. Currently, there is an incomplete understanding of how heavily pretreated triple-class exposed (received at least a PI, IMiD, and anti-CD38 mAb) MM patients are treated in a real-world setting and their outcomes.

Findings from the MAMMOTH study, a retrospective study of treatment outcomes in patients in the United States with MM, reported an overall response rate (ORR) of 31% with median overall survival (OS) of 9.3 months in refractory patients who were triple-class exposed [3]. These data highlight the poor outcomes in this heavily pretreated group of patients and suggest the need for more effective therapies.

However, to date there have been no multinational prospective studies examining outcomes of the standard of care (SOC) used in everyday clinical practice for heavily pretreated triple-class exposed patients. Here, we present results from the LocoMMotion study (NCT04035226), the first prospective, non-interventional, multinational study to assess the effectiveness of real-life SOC treatments in patients with RRMM who have been previously treated with a PI, an IMiD, and an anti-CD38 mAb.

Subjects and Methods

Study design and treatment

LocoMMotion is an ongoing, prospective, non-interventional study detailing the use of real-life current SOC in the treatment of RRMM patients who have received ≥3 prior lines of therapy (LOT) or were double refractory to a PI and an IMiD; received a PI, IMiD, and anti-CD38 mAb; and have documented disease progression during or after their last LOT. There were no exclusion criteria for prior therapies received by patients. It was conducted across 76 sites including 63 in Europe (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Russia, Spain, and the United Kingdom) and 13 in the United States; 248 patients were enrolled between August 2, 2019 and October 26, 2020. Eligible patients were ≥18 years old and had a documented diagnosis of MM per International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) criteria [4–6]; measurable disease, assessed by M-protein (≥1.0 g/dL [serum] or ≥ 200 mg/24 h [urine]) or serum free light chain (≥10 mg/dL and abnormal ratio), and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of 0 or 1.

The study included a 28-day screening phase (including first day of SOC treatment, where baseline patient and disease characteristics were collected), an SOC treatment phase (time from the first day of SOC treatment until progressive disease, unacceptable toxicity, or initiation of subsequent antimyeloma therapy, where efficacy and safety data were collected), and a follow-up phase until study completion (where patients were followed for survival and subsequent therapies). Study completion was defined as 24 months after first dose of the last patient enrolled in the study. Patient-reported outcomes were also collected (not reported in this article). SOC treatments were defined as those used in local clinical practice for the treatment of adult patients with RRMM, experimental drugs were not allowed. A Response Review Committee (RRC) composed of three leading hematologists in the field of MM reassessed responses per IMWG criteria, in a blinded manner, to ensure consistency of the assessments.

This study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent. An independent ethics committee/institutional review board at each center approved the study protocol.

To account for potential missing assessments in real-world clinical practice that are required for response evaluation, per strict IMWG criteria [6], additional measures were applied, as follows. The study was designed to collect all available data necessary for response evaluation at a minimum of each cycle of treatment (including serum protein electrophoresis, serum immunofixation electrophoresis, serum-free light chains, serum quantitative immunoglobulins, 24-hour urine M-protein quantitation by electrophoresis, urine immunofixation electrophoresis, as well as plasmacytomas, bone lesion, and bone marrow assessments). RRC reassessment of the response for each cycle of treatment was blinded to ensure consistency of assessment. The RRC used the strict IMWG criteria [6] with limited flexibility to mitigate potential missing information and avoid underestimation of the response.

Endpoints and assessments

The primary endpoint was ORR, defined as the proportion of patients who achieved partial response (PR) or better according to the IMWG criteria, as assessed by the RRC. Secondary clinical assessments included rates of stringent complete response (sCR), complete response (CR), very good partial response (VGPR), duration of response (DOR), progression-free survival (PFS), and OS. Safety assessments included incidence and severity of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs). Incidence of secondary primary malignancies was also collected.

Statistical analyses

Given the observational nature of the study, no direct hypothesis was tested; sample size was based on clinically acceptable precision of the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the primary objective. When the sample size was 230, using the large sample normal approximation, the width of a two-sided 95% CI varied from 0.107 to 0.130 for an expected proportion varying from 0.20 to 0.40. A sample size of 230 patients was assumed sufficient to investigate secondary objectives. Continuous variables were summarized using the number of observations, mean, standard deviation, coefficient of variation, median, and range. Time-to-event data were summarized by 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles with two-sided 95% CIs. Categorical values were summarized using the number of observations and percentages.

Results

Patients

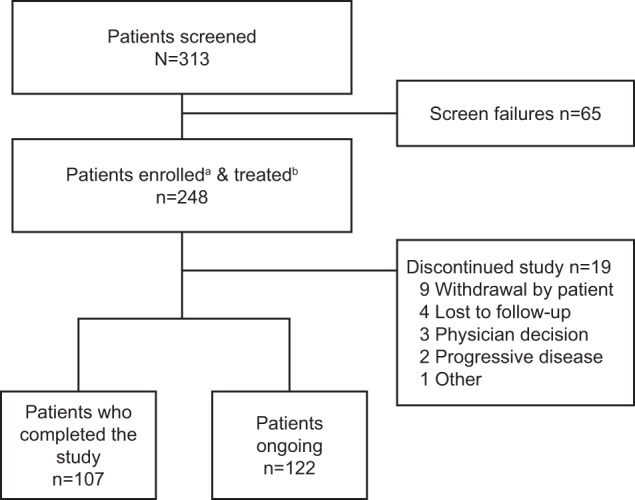

Of the 248 patients enrolled and treated, 225 (90.7%) were from Europe and 23 (9.3%) from the United States. As of the data cut-off date of May 21, 2021, representing a median follow-up of 11.01 months (range, 0.1–19.2), 107 (43.1%) patients had completed the study due to death, 122 (49.2%) patients were ongoing, and 19 (7.7%) patients had discontinued (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Study disposition.

aEnrolled patients are those who signed informed consent and were formally enrolled into the study. bTreated patients are those who were enrolled in the study and received at least one standard of care treatment.

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Median age was 68 years (range, 41–89), and 135 patients (54.4%) were male; 180 (72.9%) had a baseline ECOG PS score of 1. Median time since initial MM diagnosis was 6.3 years (range, 0.3–22.8). Patients had received a median of 4.0 prior LOTs (range, 2–13); 16 (6.5%) patients had received 2 prior LOTs and were eligible for this study due to double-refractoriness to PI and IMiD. Nearly half of the patients (122; 49.2%) had received ≥5 prior LOTs. All patients were triple-class exposed, 183 (73.8%) were triple-class refractory, and 230 (92.7%) were refractory to their last line of therapy. Seventy (32.3%) patients each presented as International Staging System (ISS) stages I and II at study entry, and 77 (35.5%) as stage III. Extramedullary plasmacytomas were present in 33 (13.3%) patients. Overall, 160 patients (64.5%) had undergone previous stem cell transplant (160 [64.5%] autologous, 11 [4.4%] allogeneic).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | N = 248 |

|---|---|

| Median age (range), years | 68 (41–89) |

| Male, n (%) | 135 (54.4) |

| Geographic region, n (%) | |

| United States | 23 (9.3) |

| Europe | 225 (90.7) |

| Race,a n (%) | N = 190 |

| White | 182 (95.8) |

| Black | 5 (2.6) |

| Other | 1 (0.5) |

| Unknown | 2 (1.1) |

| Baseline ECOG score,b n (%) | |

| 0 | 63 (25.5) |

| 1 | 180 (72.9) |

| 2 | 3 (1.2) |

| 3 | 1 (0.4) |

| Time from initial MM diagnosis, median (range) years | 6.3 (0.3–22.8) |

| Number of prior lines of therapy, median (range) | 4.0 (2–13) |

| Prior lines of therapy, n (%) | |

| 2 | 16 (6.5) |

| 3 | 48 (19.4) |

| 4 | 62 (25.0) |

| ≥5 | 122 (49.2) |

| ISS Stage (at study entry), n (%) | |

| I | 70 (32.3) |

| II | 70 (32.3) |

| III | 77 (35.5) |

| Presence of extramedullary plasmacytomas | |

| Yes | 33 (13.3) |

| No | 215 (86.7) |

| Type of measurable disease | |

| Serum only | 123 (49.6) |

| Serum and urine | 19 (7.7) |

| Urine only | 22 (8.9) |

| Serum free light chain | 82 (33.1) |

| Not evaluable | 2 (0.8) |

| Previous stem cell transplant, n (%) | |

| Autologous | 160 (64.5) |

| Allogeneic | 11 (4.4) |

| LDH (U/L) | |

| ≤245 | 114 (61.3) |

| >245 | 72 (38.7) |

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min) | |

| ≤60 | 94 (40.0) |

| >60 | 141 (60.0) |

| Triple-class exposed,c n (%) | 248 (100) |

| Refractory status, n (%) | |

| Any PI | 197 (79.4) |

| Any IMiD | 234 (94.4) |

| Any anti-CD38 mAb | 228 (91.9) |

| Triple-class refractory | 183 (73.8) |

| Penta-drug refractory | 44 (17.7) |

| Refractory to last line of prior therapy, n (%) | 230 (92.7) |

ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, IMiD immunomodulatory drug, ISS International Staging System, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, mAb monoclonal antibody, MM multiple myeloma, PI proteasome inhibitor.

aRace was not reported for 58 patients.

bScreening ECOG scores were 0 or 1 only.

cAny PI, any IMiD, and any anti-CD38 mAb.

Treatment summary

SOC treatment regimens are summarized in Table 2. Overall, 92 unique SOC treatment regimens were used in the enrolled population, including corticosteroids, PIs, IMiDs, alkylating agents, and anti-CD38 mAbs and various combinations thereof, with 160 (64.5%) patients treated with a combination of ≥3 drugs (Supplementary Table 1). The most frequent used PI, IMiD, and anti-CD38 mAb were carfilzomib (25.4%), pomalidomide (29.8%), and daratumumab (9.3%), respectively. Patients received a median of 4.0 (range, 1–20) cycles of SOC therapy and spent a median of 3.9 months (range, <1.0–18.0) on treatment. Six (2.4%) patients underwent autologous transplant, and no patients underwent allogeneic transplant. The most common reason for treatment discontinuation was disease progression in 112 (45.2%) patients.

Table 2.

Antimyeloma standard of care therapy.

| SOC treatment, n (%)a | N = 248 |

|---|---|

| Glucocorticoid | 220 (88.7) |

| PI | 133 (53.6) |

| Carfilzomib | 63 (25.4) |

| Bortezomib | 48 (19.4) |

| Ixazomib | 22 (8.9) |

| IMiD | 117 (47.2) |

| Pomalidomide | 74 (29.8) |

| Lenalidomide | 36 (14.5) |

| Thalidomide | 7 (2.8) |

| Alkylating agent | 107 (43.1) |

| Cyclophosphamide | 79 (31.9) |

| Bendamustine | 16 (6.5) |

| Melphalan | 15 (6.0) |

| Anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody | 24 (9.7) |

| Daratumumab | 23 (9.3) |

| Isatuximab | 1 (0.4) |

| Anthracyclines | 18 (7.3) |

| Topoisomerase inhibitor | 16 (6.5) |

| Other antineoplastic agentb | 15 (6.0) |

| Histone deacetylase inhibitor | 12 (4.8) |

| Anti-SLAMF7 monoclonal antibody | 9 (3.6) |

| BCMA-targeted antibody-drug conjugate | 7 (2.8) |

| Bcl-2 inhibitor | 6 (2.4) |

| Autologous stem cell transplant | 6 (2.4) |

| Mitotic inhibitor | 2 (0.8) |

| Selective inhibitor of nuclear export | 2 (0.8) |

BCMA B-cell maturation antigen, Bcl B-cell lymphoma, IMiD immunomodulatory drug, PI proteasome inhibitor, SLAM signaling lymphocytic activation molecule, SOC standard of care.

aThere was a large amount of heterogeneity in the combination therapies. Patients may have been counted in more than one regimen.

bOther antineoplastic agents included cisplatin and rituximab.

At the time of the data cut-off, 123 (49.6%) patients were exposed to subsequent antimyeloma therapies (Supplementary Table 2). Seventy-eight (31.5%) patients received 1 subsequent LOT and 45 (18.2%) patients received >1 subsequent LOT. Between 2020 and 2021, 99 unique regimens were used in subsequent LOTs, reflecting the existing variety of real-life antimyeloma treatments and absence of preferred SOC treatment in this population.

Efficacy

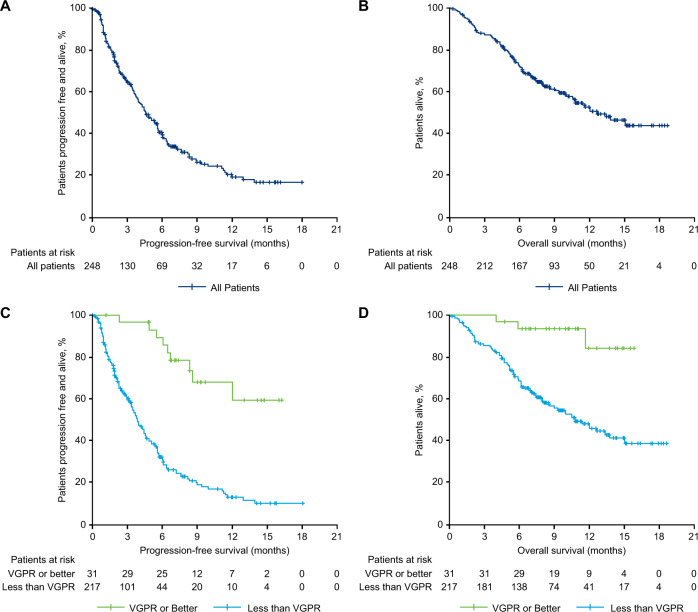

The ORR for patients treated with real-life SOC therapy was 29.8% (95% CI: 24.2–36.0) (Table 3). Median DOR was 7.4 months (95% CI: 4.7–12.5). None of the patients achieved sCR; 1 patient (0.4%) achieved CR, 30 patients (12.1%) achieved VGPR, 43 (17.3%) achieved PR, 13 patients (5.2%) achieved minimal response, 77 patients (31.0%) had stable disease, and 46 patients (18.5%) had progressive disease. Thirty-eight (15.3%) patients were considered not evaluable, of which 14 were due to death (<2 months after starting SOC therapy) and 12 to stopping or switching SOC therapy (most often due to rapid disease progression, based on investigator analysis). Median PFS was 4.6 months (95% CI: 3.9–5.6), and median OS was 12.4 months (95% CI: 10.28–NE; Fig. 2A, B). The 12-month PFS and OS rates were 19.9% (95% CI: 13.6–27.0) and 51.8% (95% CI: 44.1–58.8), respectively.

Table 3.

Response to standard of care treatment.

| Variable | Total (N = 248) |

|---|---|

| Overall response rate, % (95% CI) | 29.8 (24.2–36.0) |

| Best response, rate, % | |

| Stringent complete response | 0 |

| Complete response | 0.4 |

| Very good partial response | 12.1 |

| Partial response | 17.3 |

| Minimal response | 5.2 |

| Stable disease | 31.0 |

| Progressive disease | 18.5 |

| Not evaluable | 15.3 |

| Median duration of response (95% CI), months | 7.4 (4.7–12.5) |

| Median time to first response (range), months | 1.9 (0.7–9.5) |

| Median time to best response (range), months | 2.4 (0.7–12.2) |

CI confidence interval.

Fig. 2. Kaplan–Meier plots for survival outcomes.

Progression-free survival and overall survival based on RRC assessment in all patients (A, B) and in patients who achieved VGPR or better versus those who did not (C, D). RRC Response Review Committee, SOC standard of care, VGPR very good partial response.

Patients who did not achieve VGPR had a median DOR of 4.5 months (95% CI: 3.5–7.3), a median PFS of 3.9 months (95% CI: 3.4–4.6), and a median OS of 10.9 months (95% CI: 8.4–14.2). For the 31 patients who achieved VGPR or better, median DOR (95% CI: 7.7–NE) and median OS (95% CI: NE–NE) were not estimable, and median PFS was not reached (95% CI: 8.54–NE; Fig. 2C, D). Patients who were triple-class refractory at baseline (n = 183) had an ORR of 25.1% (95% CI: 19.0–32.1), median DOR of 4.5 months (95% CI: 3.7–NE), median PFS of 3.9 months (95% CI: 3.4–4.6), and median OS of 11.1 months (95% CI: 8.8–14.2). Patients who were not triple-class refractory (n = 65) had an ORR of 43.1% (95% CI: 30.8–56.0), median DOR of 9.1 months (95% CI: 7.3–NE), median PFS of 8.2 months (95% CI: 5.7–12.0), and median OS was not estimable (95% CI: 12.4–NE).

Safety

Within routine clinical practice, TEAEs were reported in 207 (83.5%) patients, with grade 3/4 TEAEs in 131 (52.8%) patients (Table 4). The most common hematologic AEs (any grade) were anemia (25.8%), thrombocytopenia (23.0%), and neutropenia (15.7%), and the most common grade 3/4 hematologic TEAEs were thrombocytopenia (17.7%), neutropenia (13.3%), and anemia (10.9%; Table 5). Overall, grade 3/4 cytopenia was reported in 85 (34.3%) patients; however, when the incidence of this TEAE was derived from laboratory data, grade 3/4 cytopenia was observed in 158 (64.8%) patients (Supplementary Table 3). This twofold discrepancy between reported cytopenic adverse events and toxicities derived from the laboratory data suggest an overall underreporting of adverse events in this study. The most common (≥10%) non-hematologic AEs of any grade were infections/infestations (28.6%), nervous system disorders (19.8%), diarrhea (15.3%), metabolism/nutrition disorders (12.5%), pyrexia (12.5%), fatigue (12.1%), and dyspnea (11.3%; Table 5). No non-hematologic TEAEs were observed at grade 3/4 at a rate of ≥10%. Second primary malignancies were reported in 6 patients. A total of 107 (43.1%) patients had died by the time of data cut-off, with disease progression being the leading cause of death (n = 74; 29.8%). Nineteen (7.7%) patients died due to TEAEs during the study, most commonly due to infection (n = 11).

Table 4.

Severity of standard of care treatment-emergent adverse events.

| TEAE, n (%)a | N = 248 |

|---|---|

| Any TEAE | 207 (83.5) |

| Any serious TEAE | 84 (33.9) |

| Maximum severity of TEAE | |

| Grade 1 | 16 (6.5) |

| Grade 2 | 52 (21.0) |

| Grade 3 | 78 (31.5) |

| Grade 4 | 44 (17.7) |

| Grade 5 | 17 (6.9) |

| TEAE with outcome death | 19 (7.7) |

TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event.

aPercentages are calculated with the all-treated analysis set as denominator.

Table 5.

Hematologic and non-hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events.

| TEAE | Total (N = 248) | |

|---|---|---|

| Any grade, n (%)a | Grade 3/4, n (%)a | |

| Hematologic TEAEsb | ||

| Total patients with hematologic TEAE | 106 (42.7) | 85 (34.3) |

| Anemia | 64 (25.8) | 27 (10.9) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 57 (23.0) | 44 (17.7) |

| Neutropenia | 39 (15.7) | 33 (13.3) |

| Leukopenia | 18 (7.3) | 12 (4.8) |

| Lymphopenia | 16 (6.5) | 14 (5.6) |

| Non-hematologic TEAEsb | ||

| Infections and infestations | 71 (28.6) | 16 (6.5) |

| Nervous system disorders | 49 (19.8) | 8 (3.2) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | ||

| Pyrexia | 31 (12.5) | 6 (2.4) |

| Fatigue | 30 (12.1) | 2 (0.8) |

| Asthenia | 23 (9.3) | 2 (1.2) |

| Peripheral edema | 19 (7.7) | 1 (0.4) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | ||

| Diarrhea | 38 (15.3) | 2 (0.8) |

| Nausea | 23 (9.3) | 3 (1.2) |

| Constipation | 14 (5.6) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 14 (5.6) | 2 (0.8) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 31 (12.5) | 9 (3.6) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | ||

| Back pain | 20 (8.1) | 4 (1.6) |

| Arthralgia | 15 (6.0) | 3 (1.2) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | ||

| Dyspnea | 28 (11.3) | 6 (2.4) |

| Investigations | 25 (10.1) | 6 (2.4) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 22 (8.9) | 3 (1.2) |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 22 (8.9) | 13 (5.2) |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | 21 (8.5) | 6 (2.4) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 20 (8.1) | 1 (0.4) |

| Cardiac disorders | 18 (7.3) | 9 (3.6) |

| Vascular disorders | 18 (7.3) | 7 (2.8) |

TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event.

aPercentages are calculated with the all-treated analysis set as denominator.

bReported in ≥5% of patients.

Discussion

Results of this first, prospective study of real-life SOC treatment in triple-class exposed patients with RRMM demonstrate poor outcomes with currently available treatments and confirm rapid disease progression after application of salvage therapy. ORR (29.8%) was low, and median PFS (4.6 months) and median OS (12.4 months) were short for these patients. None of the patients evaluated reached sCR and only 1 patient achieved CR, indicating responses were not deep. Responses were not durable, particularly for patients that did not achieve VGPR, who had a median DOR of 4.5 months (95% CI: 3.5–7.3). At the time of enrollment in the study, the majority of patients (74%) were refractory to three classes of antimyeloma drugs, which appeared to be an important prognostic factor of worse outcomes with current SOC treatments. This was indicated by median PFS with SOC treatment of 3.9 months (95% CI: 3.4–4.6) in patients who were triple-class refractory at baseline and 8.2 months (95% CI: 5.7–12.0) in patients who were not triple-class refractory. These data are consistent with several retrospective studies in heavily pretreated patients with RRMM, including the MAMMOTH study, that have generally shown low OS rates and rapid disease progression [3, 7, 8]. Poor outcomes in triple-class exposed patients demonstrate an unmet need for improved treatments in this heavily pretreated group.

As evidenced by the 92 combinations of SOC treatments received by patients, there is not a clearly defined SOC for triple-class exposed patients in real-world practice. This lack of SOC therapy not only leaves patients with few options for well-established treatment, but also complicates the design of clinical trials to compare SOC with new treatments. Data from this study may serve as a benchmark for future comparisons with emerging therapies, as has been the case for the MAMMOTH study in patients who were refractory to anti-CD38 mAbs, which has been used as an indirect comparator against clinical trials lacking a direct comparator arm [9, 10].

One limitation of the observational nature of the LocoMMotion study is that the incidence of TEAEs was likely underestimated. While TEAEs within routine clinical practice were common, occurring in 83.5% of patients, with about half of patients (52.8%) experiencing grade 3/4 TEAEs, it is likely that this is an underestimation that may be attributed to the tendency for physicians to more frequently report adverse events that are clinically relevant or require prescription of additional medications. However, the prospective design of the study enabled collection of all available hematology laboratory results, allowing for calculation of toxicity grades based on the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for adverse events, providing a more realistic representation of the toxicity observed with SOC treatments.

In summary, the findings of the LocoMMotion study clearly demonstrate that there is no well-established real-world SOC treatment for triple-class exposed patients with RRMM. The SOC treatments currently being utilized result in poor outcomes and often fail to prevent disease progression. Although the SOC for myeloma will continue to evolve, especially as accessibility and use of BCMA-targeting therapies increases, this study highlights the urgent need for new treatment approaches with novel therapies to improve outcomes in this group of patients.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Janssen Research & Development, LLC and Legend Biotech, Inc. Medical writing support was provided by Julie Nowicki, PhD, of Eloquent Scientific Solutions, and funded by Janssen Global Services, LLC.

Author contributions

M-VM, PM, and KW performed the role of Response Review Committee for the study. All authors contributed to the study design, study conduct, and data analysis and interpretation. All authors participated in drafting and revising the manuscript and approved the final version for submission. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests

M-VM: honoraria/member on the board of directors/advisory committees (Amgen, Adaptive Biotechnologies, BMS Celgene, Janssen, Oncopeptides, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, Sea-Gen, Takeda). KW: honoraria (Roche); consultant/honoraria (Adaptive Biotech, Karyopharm, Takeda); honoraria/membership on board of directors/advisory committees (BMS, Celgene, Amgen, GSK, Janssen, Oncopeptides, Sanofi). VDS: honoraria (Abbvie, Alexion, Amgen, AOP Pharmaceutical, BMS Celgene, Grifols, GSK, Sanofi, SOBI, Takeda); honoraria/research funding (Novartis). HG: honoraria (GSK); consultant (Adaptive Biotech); research funding (Incyte, Johns Hopkins University, Molecular Partners, MSD, Mundipharma); honoraria/research funding (Novartis); honoraria/research funding (Chugai); consultant/ honoraria/research funding (Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Sanofi). MD: honoraria/research funding (Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Sanofi). MM: honoraria (Amgen, Astellas, BMS, Gilead, Takeda, Novartis, Pfizer, Adaptive Biotech); honoraria/research funding (Celgene, Sanofi). MC: honoraria (Novartis); honoraria/consultant (GSK, Adaptive Biotech); honoraria/consultant, membership on board of directors/advisory committees/speakers bureau (BMS, Sanofi, AbbVie, Amgen, Takeda); honoraria/consultant/member of board of directors/advisory and speakers bureaus/travel accommodations and expenses (Janssen, Celgene). DD: employee/consultant/ honoraria/member of board of directors/advisory committees (Janssen Cilag); member of board of directors/advisory committees/research funding (Celgene). AuP: honoraria (AbbVie, Amgen, BMS Celgene, GSK); honoraria/research funding (Sanofi); honoraria/member of board of directors/advisory committees (Janssen); honoraria/research funding/member of board of directors/advisory committees (Takeda). RB: honoraria/research funding (Allogene, Janssen, BMS, Gilead, Servier). NWCJvdD: research funding (Cellectis), consultant (Takeda, Roche, Novartis, Bayer, Servier); research funding/consultant (Janssen, Amgen); consultant/honoraria (BMS Celgene). EMO: consultant (Sanofi, Oncopeptides); consultant/honoraria (Janssen, Takeda); consultant/honoraria/research funding (Amgen, BMS Celgene). ChS: honoraria (AbbVie); consultant (Roche); honoraria/member of board of directors/advisory committees (Novartis, Takeda); consultant/honoraria/member of board of directors/advisory committees (Amgen, BMS, Janssen). FG: honoraria (BMS); consultant/honoraria (Sanofi); member of board of directors/advisory committees (Roche, Adaptive Biotech, Oncopeptides, Bluebird Bio); honoraria/member of board of directors/advisory committees (Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Takeda, AbbVie, GSK). PR-O: honoraria/speaker bureaus (BMS Celgene, Janssen, Amgen, GSK, Sanofi, Regeneron, Oncopeptides). AB: honoraria (Amgen, BMS Celgene, Janssen, Sanofi). AnP, JMS: employees and holders of stock options at Janssen. CaS, MS, RW: employees of Janssen. SK: employee of Janssen R&D. VS: employee of Janssen Pharmaceutica NV. MV: employee of Janssen Global Services, LLC. TN: employee of Legend Biotech USA. JS-M: consultant/member of board of directors/advisory committees (AbbVie, Amgen, BMS Celgene, GSK, Janssen, Karyopharm, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Novartis, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, Secura Bio, Takeda). PS: honoraria/research funding (SkylineDx); consultant/honoraria/research (Amgen, BMS Celgene, Janssen, Karyopharm, Takeda). PM: honoraria (AbbVie, Amgen, Janssen, Sanofi, Celgene/BMS, Oncopeptides). RV, JL-H, EA, WR, and HE: no relationships to disclose. Funded by Janssen Research & Development, LLC and Legend Biotech, Inc.; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT04035226.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Maria-Victoria Mateos, Katja Weisel.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41375-022-01531-2.

References

- 1.Ravi P, Kumar SK, Cerhan JR, Maurer MJ, Dingli D, Ansell SM, et al. Defining cure in multiple myeloma: a comparative study of outcomes of young individuals with myeloma and curable hematologic malignancies. Blood Cancer J. 2018;8:26. doi: 10.1038/s41408-018-0065-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franssen LE, Mutis T, Lokhorst HM, van de Donk N. Immunotherapy in myeloma: how far have we come? Ther Adv Hematol. 2019;10:2040620718822660. doi: 10.1177/2040620718822660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gandhi UH, Cornell RF, Lakshman A, Gahvari ZJ, McGehee E, Jagosky MH, et al. Outcomes of patients with multiple myeloma refractory to CD38-targeted monoclonal antibody therapy. Leukemia. 2019;33:2266–75. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0435-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durie BG, Miguel JF, Blade J, Rajkumar SV. Clarification of the definition of complete response in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2015;29:2416–7. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar S, Paiva B, Anderson KC, Durie B, Landgren O, Moreau P, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e328–e46. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30206-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajkumar SV, Harousseau JL, Durie B, Anderson KC, Dimopoulos M, Kyle R, et al. Consensus recommendations for the uniform reporting of clinical trials: report of the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 1. Blood. 2011;117:4691–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-299487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar SK, Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E, Terpos E, Nahi H, Goldschmidt H, et al. Natural history of relapsed myeloma, refractory to immunomodulatory drugs and proteasome inhibitors: a multicenter IMWG study. Leukemia. 2017;31:2443–48. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Usmani S, Ahmadi T, Ng Y, Lam A, Desai A, Potluri R, et al. Analysis of real-world data on overall survival in multiple myeloma patients with >/=3 prior lines of therapy including a proteasome inhibitor (PI) and an immunomodulatory drug (IMiD), or double refractory to a PI and an IMiD. Oncologist. 2016;21:1355–61. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa LJ, Lin Y, Martin TG, Chhabra S, Usmani SZ, Jagannath S, et al. Cilta-cel versus conventional treatment in patients with relapse/refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:8030–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.8030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blade Creixenti J, Mateos M-V, Oriol A, Larocca A, Cavo M, Rodríguez-Otero P, et al. HORIZON (OP-106) Versus MAMMOTH: an indirect comparison of efficacy outcomes for patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma refractory (RRMM) to anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody therapy treated with melflufen plus eexamethasone versus conventional agents. Blood. 2020;136:2–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2020-137164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.