Abstract

The American Society for Preventive Cardiology (ASPC) "Ten things to know about ten cardiovascular disease risk factors – 2022" is a summary document regarding cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors. This 2022 update provides summary tables of ten things to know about 10 CVD risk factors and builds upon the foundation of prior annual versions of "Ten things to know about ten cardiovascular disease risk factors” published since 2020. This 2022 version provides the perspective of ASPC members and includes updated sentinel references (i.e., applicable guidelines and select reviews) for each CVD risk factor section. The ten CVD risk factors include unhealthful dietary intake, physical inactivity, dyslipidemia, pre-diabetes/diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, considerations of select populations (older age, race/ethnicity, and sex differences), thrombosis (with smoking as a potential contributor to thrombosis), kidney dysfunction and genetics/familial hypercholesterolemia. Other CVD risk factors may be relevant, beyond the CVD risk factors discussed here. However, it is the intent of the ASPC "Ten things to know about ten cardiovascular disease risk factors – 2022” to provide a tabular overview of things to know about ten of the most common CVD risk factors applicable to preventive cardiology and provide ready access to applicable guidelines and sentinel reviews.

Key words: Adiposopathy, Blood pressure, Cardiovascular disease risk factors, Diabetes, Genetics/familial hypercholesterolemia, Glucose, Kidneys, Lipids, Obesity, Nutrition, Physical activity, Preventive cardiology, Sex, Smoking, Thrombosis

1. Introduction

The American Society for Preventive Cardiology (ASPC) "Ten things to know about ten cardiovascular disease risk factors – 2022" is intended to help both primary care clinicians and specialists be informed about the latest advances in cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention. This 2022 update summarizes ten things to know about ten important CVD risk factors, listed in tabular formats, and reflects updates by ASPC Fellowship in Training or Early Career section authors. These CVD risk factors include unhealthful dietary intake, physical inactivity, dyslipidemia, pre-diabetes/diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, considerations of select populations, sex differences, and race/ethnicity, thrombosis (with smoking as a potential contributor to thrombosis), kidney dysfunction, and family history/genetics/familial hypercholesterolemia. The intent is not to create a comprehensive discussion of all aspects of preventive cardiology. Instead, the intent is to focus on fundamental clinical considerations in preventive cardiology. For a more detailed discussion of any of these CVD risk factors, this "Ten things to know about ten cardiovascular disease risk factors – 2022" also provides updated guidelines and other selected references in the applicable tables.

Within the individual, not all CVD risk factors share the same etiology. However, factor analyses and clinical experience supports that in many cases, the clustering of the most common metabolic diseases managed by clinicians is due to an underlying “common soil” causality.[1] The obesity epidemic and its adiposopathic consequences are leading contributors to major CVD risk factors such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia that increase CVD risk, as well as other effects that directly increase CVD risk,[2, 3] Central adiposity is the only physical exam component of the metabolic syndrome.[4] A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association states:

“Obesity contributes directly to incident cardiovascular risk factors, including dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and sleep disorders. Obesity also leads to the development of cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular disease mortality independently of other cardiovascular risk factors. More recent data highlight abdominal obesity, as determined by waist circumference, as a cardiovascular disease risk marker that is independent of body mass index [469].”

In some countries, increased adiposity has overtaken cigarette smoking as the leading cause of preventable death. [5] The two most common causes of non-accidental and non-infectious preventable deaths are CVD and cancer. It is therefore perhaps not surprising that CVD and cancer share similar modifiable risk factors, with cancer being a potential risk factor for CVD.[6] Recognition and examination of “adiposopathy” has emerged in the cancer literature, due to: “the tremendous growing implication of ‘sick fat’ in the initiation and development of important pathopysiological events in the human body, which result in severe (chronic) diseases and possible early mortality,” including an important role in cancer and (cardio)metabolic diseases. [7] Regarding cardiovascular prevention, cardio-oncology is a subspecialty of cardiology originally created to address adverse cardiac effects of cancer treatments. An important component of global care within cardio-oncology is addressing the multiple risk factors shared by CVD and cancer, such as obesity and tobacco use, and other related risk factors. [8]

A focus on both CVD treatment and prevention is not unique to the cardio-oncologist. Many patients with CVD have multiple CVD risk factors, which requires a multifactorial management approach. Patients with CVD, or who are at risk for CVD, benefit from global CVD risk reduction, with appropriate attention given to all applicable CVD risk factors. It may therefore be helpful for clinicians to have an overview of core principles applicable to the multiple CVD risk factors that often occur within the same patient who has CVD, or who is at risk for CVD. Finally, this version of the "Ten Things to Know About Ten CVD Risk Factors" includes updates and different perspectives from different authors. Interested readers may elect to review prior versions of ASPC "Ten Things to Know About Ten CVD Risk Factors" publications for different perspectives on these same topics, and to see how thinking and priorities may have evolved. [9, 10]

1.1. Unhealthful dietary intake

1.1.1. Definition

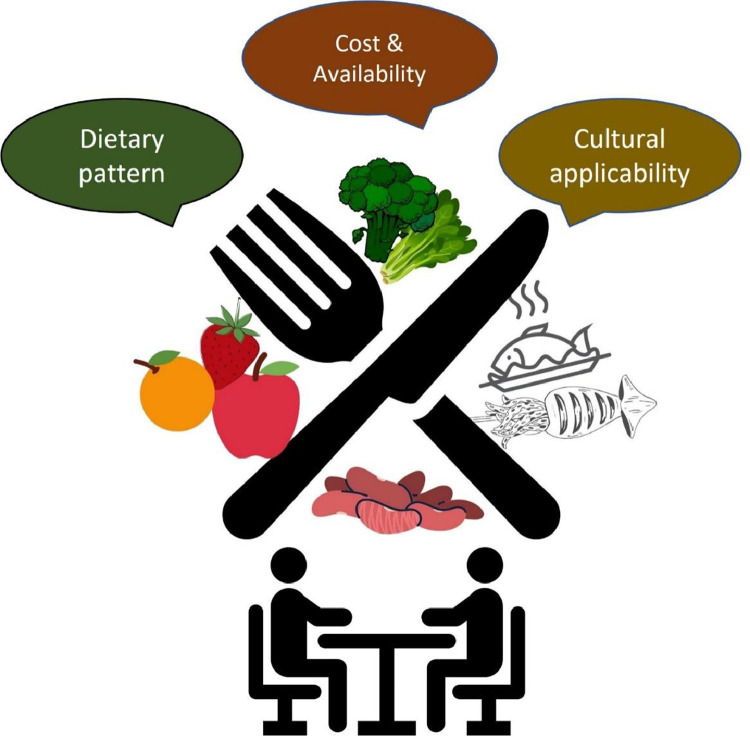

Healthful nutrition is a cornerstone of CVD prevention; yet it is often among the most challenging of CVD risk factors to manage. Despite these challenges, even small targeted healthful changes in dietary intake have the potential to improve CV health. [11] The primary components of nutritional screening and medical nutrition therapy for CVD prevention include qualitative composition, energy content, and food consumption timing. A healthful nutrition plan is best crafted utilizing evidenced-based dietary patterns and shared decision-making between clinician and patient. [12] Considerations include social background, cultural applicability, cost, availability, and prioritization of nutritional goals as determined by the patient's health status (Figure 1) and the presence of metabolic diseases and cardiometabolic risk factors (e.g., high blood sugar, high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, and increased body fat). [12] The most healthful dietary strategy incorporates evidence-based nutrition and feeding patterns. [13] Dietary patterns most associated with reduced CVD risk are those that: [6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

• Prioritize:

-

○

Vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, whole grains, seeds, and fish

-

○

Foods rich in monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids such as fish, nuts, and non-tropical vegetable oils

-

○

Soluble fiber

•Limit:

-

○

Saturated fat, such as tropical oils, as well as ultra-processed meats preserved by smoking, curing, or salting or addition of chemical preservatives, such as bacon, salami, sausages, hot dogs, or processed deli or luncheon meats, which in addition to containing saturated fats, may also have increased sodium, nitrate, and other components which might account for an increase CVD risk compared to unprocessed red meat [14]

-

○

Excessive sodium

-

○

Cholesterol, especially in patients at high risk for CVD with known increases in cholesterol blood levels with increased cholesterol intake

-

○

Ultra-processed carbohydrates

-

○

Sugar-sweetened beverages

- ○

-

○

Trans fats

Figure 1.

Adoption of healthful nutrition is a shared decision process between clinician and patient, with priorities based upon evidence-based dietary patterns, nutrition goals, cultural applicability, cost, and availability. While potentially counterintuive, patient preference is not consistently associated with improved health outcomes when implemeting medical nutrition therapy [17], [18], [19]. Healthful food choices made after medical nutrition therapy may differ from “preferred” food choices made before medical nutrition therapy.

1.1.2. Epidemiology

-

•

From 2015–2018, 17.1% of U.S. adults > 20 years of age were on a “special diet” on a given day. More females were on a special diet than males, and more adults aged 40–59 and > 60 years of age were on a special diet than adults aged 20–39. The most common type of special diet reported among all adults was a weight loss or low-calorie diet. From 2007–2008 through 2017–2018, the percentage of adults on any special diet, weight loss or low-calorie diets, and low carbohydrate diets increased, while the percentage of adults on low-fat or low-cholesterol diets decreased.[20]

-

•

Positive caloric balance and increased body fat increase the risk of CVD.[21]Atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) is rare among hunter-gatherers populations, whether the nutritional intake is higher or lower in fat, and irrespective of variations in plant vs meat intake. [22, 23, 24] Despite higher levels of physical activity, total energy expenditure among rural hunter-gatherers may be like adults living in European or US cities with high rates of obesity. [23] The reduced rate of CVD among hunter-gatherers may be attributable to lower body fat, with the BMI of hunter-gatherer populations typically being < 20 kg/m2, [25] which is substantially below the BMI of many industrialized nations where CVD is the #1 cause of death. The reduced potential for adiposopathic consequences helps explain why hunter-gatherer populations have lower blood pressure, and a total cholesterol level of ∼ 100 mg/dL, compared to a total cholesterol level of ∼ 200 mg/dL in adult Americans. [26] In addition to lower BMI, the reduction in CVD risk factors and reduction in CVD events among hunter-gatherer populations may be partially related to their preferential consumption of whole foods and fiber, as well as their dependence on daylight for feeding and, therefore, eating patterns better aligned with natural circadian rhythms. [25]

1.1.3. Diagnosis and Treatment

Table 1 lists ten things to know about nutrition and CVD prevention.

Table 1.

Ten things to know about nutrition and cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention.

|

Sentinel Guidelines and References.

2021 Dietary Guidance to Improve Cardiovascular Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association [91].

2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020 – 2025 [92].

2019 A Clinician's Guide to Healthy Eating for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention [38].

2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guideline [93].

2018 Clinician's Guide for Trending Cardiovascular Nutrition Controversies: Part II [21].

1.2. PHYSICAL INACTIVITY

1.2.1. Definition and Physiology

Physical activity is any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure. [94, 95] The intensity of physical activity is defined in terms of metabolic equivalent units (METS). One MET is defined as the oxygen consumed while sitting at rest and is equal to 3.5 ml O2 per kg body weight x minutes. [96] Light activity (e.g., slow walking) is 1.6-2.9 METS, moderate-intensity activity (e.g., moderate speed walking) is 3.0-5.9 METS and vigorous activity (e.g., moderate jogging) is ≥6 METS. As a frame of reference, patients who undergo cardiac stress testing and able to achieve ≥ 10 METS (e.g., high moderate to fast jogging) on a treadmill without ST-depression are generally at very-low risk for clinical CVD. [97] Sedentary behavior refers to any waking activity with a low level of energy expenditure while sitting or lying down (1-1.5 METS).[98, 99]

Physical exercise is a subcategory of physical activity that is “planned, structured, repetitive, and aims to improve or maintain one or more components of physical fitness.” [94] Physical activity also includes muscle activity during leisure time, for transportation, and as part of a person's work – often termed non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT).[94] Among two individuals of similar size, NEAT can be the single greatest inter-individual difference in daily energy expenditure, with variances of up to 2000 kcal per day; [100] the energy expenditure due to NEAT physical activity often exceeds the daily energy expenditure due to physical exercise.[101] Physical inactivity increases the risk of CVD, [102, 103] not unlike other risk factors such as cigarette smoking and dyslipidemia. [104]

1.2.2. Epidemiology

-

•

Only 50% of adults get sufficient physical activity to reduce the risk of many chronic diseases such as CVD [105]

-

•

Roughly $117 billion in US healthcare costs yearly and 10% of premature mortality is associated with inadequate physical activity [105]

-

•

Only 26% of US adult males and 19% of adult females obtain guideline-directed activity levels according to federal physical activity monitoring data. [106]

-

•

Worldwide, approximately 3.9 million premature deaths annually might be prevented with adequate physical activity. [107]

1.2.3. Diagnosis and Treatment

One example of clinically implementing physical activity is a physical exercise prescription that includes frequency, intensity, time spent, type, and enjoyment (FITTE). [108, 27, 109] Table 2 lists ten things to know about the diagnosis and treatment of physical inactivity and CVD prevention.

Table 2.

Ten things to know about physical inactivity and cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention.

|

|

Sentinel Guidelines and References 2020 World Health Organization Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior [127] 2020 Top 10 Things to Know about the Second Edition of the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans [128] 2020 ESC Guidelines on sports cardiology and exercise in patients with cardiovascular disease: The Task Force on sports cardiology and exercise in patients with cardiovascular disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) [109] 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [93] 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee [98] |

1.3. DYSLIPIDEMIA

1.3.1. Definition and Physiology

Lipids include fats, steroids, phospholipids, steroids, triglycerides, and cholesterol that are important cellular components of body tissues and organs. Lipids are carried in the blood by lipoproteins. Except for cholesterol carried by HDL particles (and in some cases, possibly chylomicrons), other lipoproteins that carry cholesterol are atherogenic. Increased cholesterol blood levels reflect the presence of increased atherogenic lipoproteins that may become entrapped within the subendothelial space, where they may undergo oxidation and scavenging by arterial macrophages, resulting in endothelial dysfunction, foam cells, fatty streaks, and atherosclerotic plaque formation. [129] Progressive enlargement of the atherosclerotic plaque may produce chronic hemodynamically significant narrowing of the artery resulting in angina or claudication; acute plaque rupture may cause myocardial infarction and/or stroke.

Atherogenesis is promoted by increased numbers of atherogenic lipoproteins. Apolipoprotein B (apoB) levels and non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDL-C) are predictors of ASCVD risk and superior to measuring the cholesterol carried by atherogenic lipoproteins low density lipoprotein (LDL-C) in predicting atherosclerotic CVD risk. [130] One molecule of apolipoprotein (apo) B is found on each atherogenic lipoprotein. The collection of all cholesterol carried by atherogenic lipoproteins (i.e., except HDL cholesterol) is termed non-HDL cholesterol (calculation of non-HDL cholesterol = total cholesterol – HDL cholesterol). [131] Because apo B and non-HDL cholesterol better reflect ASCVD risk (compared to LDL-C alone), measurement of these biomarkers may provide additional useful information regarding risk for CVD events and are sometimes included in lipid management guidelines and societal recommendations. [132, 133] This is especially true when atherogenic lipoprotein particle numbers are discordant with atherogenic lipoprotein cholesterol levels, [131] as may occur with diabetes mellitus or adiposopathic dyslipidemia. [27, 134]

Largely because of convention, and because CVD outcomes trials of lipid-altering drugs have specified LDL-C as the primary lipid efficacy parameter, LDL-C remains the primary lipid treatment target in most dyslipidemia management guidelines. While LDL-C can be measured directly, it is often reported as a calculated value according to the Friedewald formula (LDL-C = total cholesterol – HDL-C – triglyceride/5). The Friedewald calculation is less accurate when triglycerides are elevated (i.e., ≥ 400 mg/dL) or LDL-C levels are low (i.e., < 70 mg/dL), and in these cases, LDL-C levels may be more accurately calculated using the Martin Hopkins equation. [135]

Remnant lipoproteins are formed in the circulation via triglyceride-rich lipoproteins that undergo lipolysis by various lipases, such as chylomicrons and very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), leading to small VLDL and intermediate density lipoproteins (IDL). Lipoprotein remnant cholesterol is the cholesterol carried by lipoprotein remnants and is a marker of ASCVD risk. Remnant cholesterol is sometimes defined as blood cholesterol not contained in LDL and HDL particles. The methodology of measuring and reporting lipoprotein remnants vary, often do not correlate well with one another. [136] Measurement of remnant lipoprotein cholesterol is not included in most major lipid management guidelines.

“Advanced lipid testing” may provide additional information regarding how circulating lipids and lipoproteins may impact ASCVD risk. As with apoB (a measure of atherogenic lipoprotein particle number), an increase in LDL particle number increases the risk for ASCVD. Smaller, more dense LDL particles are also associated with increased ASCVD risk; however, sole reliance on LDL particle size may be misleading, [137] and LDL particle size analyses are not recommended for ASCVD risk estimation. [131, 138, 139]

Regarding definitions, lipid treatment “targets” are often defined as the lipid parameter being treated (e.g., LDL-C), lipid “goals” are the desired lipid parameter level, and lipid “threshold” being the level by which if exceeded, may prompt the addition or intensification of lipid-lowering therapy. [31] While some prior lipid guidelines were interpreted as suggesting lipid “goals” were no longer clinically justified, [140, 141, 142], many current inter-societal and international lipid guidelines have reaffirmed goals or thresholds in the management of patients with dyslipidemia. [31, 139] For example, the 2018 ACC/AHA Lipid Guidelines recommend additional lipid-altering therapies when LDL-C ≥ 70 mg/dL for patients at very high ASCVD risk and ≥100 mg/dL for patients at high ASCVD risk). [31] The 2018 ESC/EAS guideline recommends an LDL-C goal of < 70 mg/dL for patients at high ASCVD risk, < 55 mg/dL in patients at very high ASCVD risk, and < 40 mg/dL in patients with second CVD event within 2 years.[139] Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia have marked elevations in cholesterol levels and represent a uniquely challenging patient population discussed in Section “10 Familial Hypercholesterolemia.” No treatment goals exist for most other lipid parameters, such as high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and lipoprotein (a), with lipoprotein (a) discussed in sections “3 Dyslipidemia,” “7 Selected Populations,” and Section “10 Familial Hypercholesterolemia.”

1.3.2. Epidemiology

According to the US Centers for Disease Control:[143]

-

•

Data reported from 2015–2016 suggests that more than 12% of adults age 20 and older had total cholesterol higher than 240 mg/dL

-

•

Only slightly more than half of U.S. adults (55%, or 43 million) who could benefit, are taking cholesterol-lowering pharmacotherapy

-

•

The number of U.S. adults age 20 or older who have total cholesterol levels higher than 200 mg/dL is approximately 95 million, with nearly 29 million adult Americans having total cholesterol levels higher than 240 mg/dL

1.3.3. Diagnosis and Treatment

Table 3 lists ten things to know about the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia and CVD prevention.

Table 3.

Ten things to know about lipids and cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention

| |

| Risk Category | 10-Year ASCVD Risk |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Sentinel Guidelines and References 2021 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Management of ASCVD Risk Reduction in Patients With Persistent Hypertriglyceridemia [175] 2020 Consensus Statement By The American Association Of Clinical Endocrinologists And American College Of Endocrinology On The Management Of Dyslipidemia And Prevention Of Cardiovascular Disease [147] 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [93] 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. [139] 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. [31] | |

1.4. PRE-DIABETES/DIABETES

1.4.1. Definition and Physiology

Diabetes mellitus is a pathologic condition characterized by high blood glucose. Type 1 diabetes results from an absolute deficiency of insulin secretion. The early stages of T2DM are often characterized by insulin resistance, that when accompanied by an inadequate insulin secretory response, results in hyperglycemia leading to pre-diabetes or type 2 diabetes mellitus. Among patients with T2DM, the degree of insulin resistance and insulin secretion can substantially vary. [179] Diabetes mellitus can be diagnosed [180] with one of the following measurements:

-

•

Hemoglobin A1c level ≥ 6.5%

-

•

Fasting (at least 8 hours) plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL on two successive measurements

-

•

Random glucose level of ≥ 200 mg/dL in a patient with symptoms of hyperglycemia

-

•

Oral glucose tolerance test (75 grams glucose in water) with 2-hour glucose value ≥ 200 mg/dL

Diabetes mellitus contributes to both microvascular disease (e.g., retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy) and macrovascular disease (e.g., cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular events). Hyperglycemia may contribute to atherosclerosis via direct and indirect mechanisms. Direct adverse effects of elevated circulating glucose levels include endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, heightened systemic inflammation, activation of receptors of advanced glycosylated end products, increased LDL oxidation, and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) dysfunction. Indirect adverse effects of elevated glucose levels include platelet hyperactivity. While insulin resistance (i.e., as might be mediated by mechanisms involving adiposopathic responses associated with obesity) often leads to hyperglycemia, hyperglycemia may conversely contribute to insulin resistance via glucotoxicity. [181] Similarly, hyperinsulinemia may be both the consequence and driver of insulin resistance. [182] Normalizing hyperglycemia and reducing glucotoxicity (without promoting insulin release) is one proposed mechanism how sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2 inhibitors) may increase peripheral insulin sensitivity. [183] Insulin resistance may increase non-esterified circulating free fatty acids and worsen dyslipidemia, (e.g., increased very low-density lipoprotein hepatic secretion, reduced HDL-C levels, and increased small, more dense LDL particles). [184]

Females with a prior history of gestational diabetes are at increased risk for the development of T2DM. [185] Many risk factors for CVD are also risk factors for gestational diabetes (e.g., increased body fat, physical inactivity, increased age, nonwhite race, hypertension, reduced HDL-C, triglycerides ≥ 250 mg/dL). A history of gestational diabetes mellitus also doubles the risk for CVD. [186] Diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) includes a 75-gram oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) performed at 24 – 28 weeks of gestation. GDM is diagnosed when fasting glucose levels are ≥ 92 mg/dL, or 2-hour glucose levels ≥ 153 mg/dl. The diagnosis of GDM is also made when during an OGTT, the 1 hour glucose levels is ≥ 180 mg/dL.[187] Other complications of pregnancy that may increase CVD risk include preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, preterm delivery, small for gestational age, large for gestational age, placental abruption, miscarriage, or stillbirths. [188]

1.4.2. Epidemiology

T2DM is associated with double the risk for death and a 10-fold increase in hospitalizations for coronary heart disease. [189] According to the US Centers for Disease Control: [190]

-

•

About 30.3 million US adults have diabetes mellitus; 1 in 4 may be unaware

-

•

About 2% to 10% of yearly pregnancies in the United States are affected by gestational diabetes.

-

•

Diabetes mellitus is the 7th leading cause of death in the US

-

•

Diabetes mellitus is the most common cause of kidney failure, lower-limb amputations, and adult-onset blindness

-

•

In the last 20 years, the number of adults diagnosed with diabetes mellitus has more than doubled

1.4.3. Diagnosis and Treatment

Table 4 lists ten things to know about the diagnosis and treatment of diabetes mellitus and CVD prevention.

Table 4.

Ten things to know about diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention.

|

|

Sentinel Guidelines and References 2022 Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes [191] 2022 Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes[193] 2021 Cardiorenal Protection With the Newer Antidiabetic Agents in Patients With Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association [204] 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. [205] 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease [93] |

1.5. HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE

1.5.1. Definition and Physiology

Hypertension (HTN) can be defined as arterial blood pressure (BP) readings that, when persistently elevated above ranges established by medical organizations, adversely affect patient health. African Americans have a higher prevalence of HTN than White individuals, helping to account for a higher rate myocardial infarction, stroke, chronic and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), and congestive heart failure among African Americans. [206, 207]

A challenge with diagnosis of HTN is ensuring accurate BP measurement: [208, 209]

-

•

Patients should avoid caffeine, physical exercise, stress, and/or smoking for 30 minutes prior to BP measurement.

-

•

Patients should have an empty bladder, have clothing removed from the arm, be seated with feet flat on the floor, relaxed and quiet for 5 minutes prior to BP measurement.

-

•

BP should be obtained by properly validated and calibrated BP measurement device, with proper cuff size, and taken by trained medical personnel.

-

•

On first measurement date, BP should be measured in both arms by repeated values separated by at least one minute, with a record of the values and respective arms (left and right).

-

•

Longitudinally, future BP measurement should be on the same arm previously recorded as having the highest BP measurement.

1.5.2. Epidemiology

According to the US Centers for Disease Control: [210]

-

•

Uncontrolled HTN rates are rising in the US, with nearly half of adults in the US (108 million, or 45%) having HTN defined as a systolic BP ≥ 130 mm Hg or a diastolic BP ≥ 80 mm Hg or are taking medication for hypertension.

-

•

Approximately 1 in 4 adults (24%) with HTN have their BP under control.

-

•

At least half of adults (30 million) with BP ≥140/90 mm Hg who should be taking medication to control their BP are not prescribed or are not taking medication.

1.5.3. Diagnosis and Treatment

Diagnosing HTN requires accurate assessment and measurement. In a medical office setting, BP should be obtained by properly validated and calibrated BP measurement devices, with proper cuff size, and taken by trained medical personnel. [93, 211] Regarding BP self-monitoring outside of a medical office setting (e.g., home, workplace), validated BP measuring devices can be found at the US BP Validated Listing (VDL™ at https://www.validatebp.org), which is an American Medical Association web-based independent review initiative that determines which BP measuring devices available in the U.S. meet the Validated Device Listing Criteria. Most guidelines and scientific statements do not recommend the routine use of finger devices and wrist cuffs because of higher likelihood of incorrect positioning. [211]

Ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) is often performed out of the office setting via a BP cuff device that records BP readings every 15 – 30 minute intervals, typically for 24 to 48 hours. Because of repeated BP measurements over an extended time, ABPM is superior to a single office BP measurement in the overall assessment of BP, with implications regarding assessment of target organ damage and CVD risk. Some believe ABPM is the gold standard measurement for any patient with high BP. Selected patients who may especially benefit from ABPM include patients with otherwise variable BP readings or patients with suspected “white coat” or “masked” hypertension. [212]

Lowering BP reduces CVD risk, reduces the progression of kidney disease, and reduces overall mortality among a range of patients otherwise at risk for CVD. [213, 214, 215, 213, 214, 216, 217, 208] Table 5 lists ten things to know about the diagnosis and treatment of HTN and CVD prevention.

Table 5.

Ten things to know about hypertension and cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention.

|

| Sentinel Guidelines and References 2020 International Society of Hypertension Guideline [218] 2020 Self-Measured Blood Pressure Monitoring at Home: A Joint Policy Statement From the American Heart Association and American Heart Association [211] 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease [93] 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension [209] 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults [208] |

1.6. PRE-OBESITY AND OBESITY

1.6.1. Definition and Physiology

Overweight is defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 and < 30 kg/m2. Obesity is defined as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2. An increase in BMI is associated with an increase in coronary artery calcium, carotid intimal medial thickness, left ventricular thickness, [236, 237] and increased lifetime CVD risk, [238, 236] all substantially mediated by obesity-promoted CVD risk factors. [239, 27] Obesity can be subcategorized into different classes, based upon BMI: [240]

-

•

Class I (BMI 30-34.9 kg/m2)

-

•

Class II (BMI 35-39.9 kg/m2)

-

•

Class III (or “severe;” BMI ≥40 kg/m2)

Overall, BMI is an acceptable criterion to assess adiposity for populations and most patients. BMI is often the first step in evaluating the patient with potential increased body fat. However, among individuals, relying upon BMI alone may be misleading. An increase in BMI among patients with increased muscle mass (“body builders”) might erroneously suggest an increase in body fat. Conversely, a “normal” BMI in patients with decreased muscle mass (sarcopenia) might underestimate body fat. [27] Especially in the individual, percent body fat more accurately assesses body fat than BMI.

While percent body fat analysis may provide diagnostic clarity, measures of percent body fat differ in their accuracy and reproducibility. Dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is often considered a “gold standard” for clinical body composition analysis, with other common clinical techniques to measure percent body fat including bioelectrical impedance analysis, air-displacement plethysmography, underwater weighing, and calipers. Other more research-oriented techniques to measure percent body fat include computerized tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and deuterium dilution hyrometry [241]. Pre-obesity can be defined as a percent body fat of 30 – 34% for females and 25 – 29% for males, with obesity defined as ≥ 35% body fat for females and ≥ 30% body fat for males [241].

Although percent body fat assessment (via a reliable method) is more accurate than BMI alone in assessing body fat, percent body fat is more diagnostic than prognostic. From a cardio-preventive standpoint, at least since the 1940’s, the risk of CVD is known to correlate to android fat. [1] Android fat includes the visceral adipose tissue (VAT) surrounding intra-abdominal body organs plus the abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT). [242] Males described as having an “apple” distribution of body fat are at increased risk of CVD compared with females having a “pear” distribution of body fat. [1, 242] Increased waist circumference is the only physical finding criteria of the metabolic syndrome. The metabolic syndrome [243] is an LDL-C-independent clustering of CVD risk factors that include 3 or more of the following:

-

•

Elevated waist circumference [males ≥ 40 inches (102 cm); females ≥ 35 inches (88 cm)]

-

•

Different waist circumference diagnostic criteria may apply to different races or ethnicities (e.g., Asian males ≥ 40cm; Asian females ≥ 80 cm) [244]

-

•

Elevated triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L), or use of medications for high triglycerides

-

•

Reduced HDL-C (males < 40 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L); females < 50 mg/dL (1.29 mmol/L), or use of medications for low HDL-C

-

•

Elevated blood pressure (≥ 130/85 mm Hg or use of medication for HTN)

-

•

Elevated fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or use of medication for hyperglycemia (i.e., prediabetes or type 2 diabetes mellitus).

But just as with BMI and percent body fat, measuring waist circumference alone has its prognostic limitations. From a CVD perspective, it is the specific collection of visceral adipose tissue that is thought to most reflect the pathogenic state of increased adiposity. Both VAT and SAT can be pathogenic. [242] During positive caloric balance, if SAT is limited in its ability to store energy via adipocyte proliferation and differentiation, then energy overflow may occur with increased circulating fatty acid delivery to body organs, and potentially contributing to fatty muscle and liver (contributing to insulin resistance) and fatty heart. Energy overflow can also increase VAT, as well as epicardial adipose tissue (EAT), with EAT considered the visceral fat of the heart. [242] Thus, central obesity is a clinical marker of adiposopathy and increased visceral adiposity is a surrogate marker for global fat dysfunction. [121] Assessment of visceral fat requires that it be measured, in ways beyond waist circumference alone. That is because the correlation of waist circumference with visceral adiposity is highly dependent on factors such as sex and ethnicity. [242, 245] Optimally, visceral fat should be < one pound and android fat < 3 pounds (as assessed by DXA for example). Values greater than these are associated with increased risk of cardiometabolic abnormalities such as increased blood glucose, increased blood pressure, and increased blood lipids.[241]

In short, increased body fat can result in “fat mass disease” and “sick fat disease.” [246] Examples of the adverse biomechanical aspects of obesity (“fat mass disease”) include compromise of cardiac function via pericardial mechanical restraint, impaired left ventricular expansion, impaired left ventricular filling, diastolic heart failure, sleep apnea, and immobility. [27] Additionally, an increase in body fat can also lead to adipocyte and adipose tissue dysfunction (“sick fat”). Adiposopathy is defined as pathogenic disturbance in adipose tissue anatomy and function that is promoted by positive caloric balance in genetically and environmentally susceptible individuals that result in adverse endocrine and immune responses that may directly promote CVD, and may cause or worsen metabolic disease. [2, 246, 241] Beyond the indirect increased CVD risk with obesity (e.g., promotion of metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia – all major CVD risk factors), [247, 248, 249] obesity may also result in adiposopathic consequences that directly increase CVD risk. [2] Epicardial and visceral fat share the same mesodermal embryonic origin, both are associated with increased CVD risk, and both are highly correlated with increased coronary calcification. Epicardial adipose tissue can directly contribute to heart failure (e.g., especially heart failure with preserved ejection fraction or HFpEF), atherosclerosis, cardiac dysrhythmias, fatty infiltration of the heart, and increased coronary calcium through the physical increase in fat mass surrounding the heart, as well as pathogenic paracrine and vasocrine signaling and transmission of inflammatory factors, fatty acids, and possibly transport of atherogenic lipoproteins (i.e., “outside to in” model of atherosclerosis) [27]

1.6.2. Epidemiology

According to the US Centers for Disease Control: [250]

-

•

Data from 2015∼2016 suggests the prevalence of obesity (body mass index/BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) was ∼ 40% of United States (US) adults. [250] Projections suggest that most of today's children (∼ 60%) will develop obesity at the age of 35 years, and roughly half of the projected prevalence will occur during childhood. [251]

-

•

Positive caloric balance may result in enlargement of adipocytes and adipose tissue, resulting in adiposopathy (i.e., adipose tissue intracellular and intercellular stromal dysfunction leading to pathogenic adipose tissue endocrine and immune responses) that contribute to metabolic diseases – most being major risk factors for CVD. [2, 27] Some of the most common adiposopathic metabolic consequences of obesity are major CVD risk factors such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and hypertension. [27, 252] Over the past decades, along with the obesity epidemic, the rates of T2DM and hypertension have also dramatically increased. [252]

-

•

Concomitant with the increased prevalence of obesity and metabolic CVD risk factors is the intake of energy dense foods with low nutritional value, eating dealignment with circadian rhythms, [253] and consumption of fast foods. [254]

-

•

The prevalence and severity of obesity in US adults has significantly increased from 1999-2000 through 2017-2018 [250]

-

•

In 2017∼2018, the age-adjusted prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) was ∼ 40% of US adults [250]

-

•

In 2017-2018, non-Hispanic Black adults (49.6%) - especially non-Hispanic Black females (56.9%) - had the highest age-adjusted prevalence of obesity compared with other race and Hispanic-origin groups [250]

-

•

In 2017-2018, the age-adjusted prevalence of severe obesity (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2) was 9.2% of US adults [250]

-

•

Complications of obesity include heart disease and stroke

-

•Other CVD-related complications of obesity include adiposopathic alterations in:[27]

-

○CVD risk factors (e.g., diabetes mellitus, HTN, dyslipidemia)

-

○Cardiovascular hemodynamics and heart function

-

○Heart, heart cells, and structure (which can result in electrocardiogram tracing abnormalities)

-

○Atherosclerosis and myocardioal infarction

-

○Adiposopathic immunopathies that promote CVD risk factors and CVD

-

○Adiposopathic endocrinopathies that promote CVD risk factors and CVD

-

○Thrombosis

-

○

While current antiobesity drug treatments can improve CVD risk factors, their clinical use is limited to only ∼ 1% of eligible patients. [255] Importantly, no current anti-obesity drug has CVD outcomes data to support the use of anti-obesity drugs to reduce CVD events. However, drugs such as GLP-1 receptor agonists have cardiovascular outcome study findings supporting a reduction in CVD among patients with diabetes mellitus, with most study participants having pre-obesity or obesity. [199] Higher doses of some of these same GLP-1 receptor agonists are approved for treatment of obesity (i.e., ligraglutide and semaglutide). Ongoing CVD outcomes trials are ongoing to determine if existing or future anti-obesity drugs will likewise reduce CVD events. [27, 256]

Bariatric surgery continues to evolve as a treatment for obesity. [27] Bariatric surgery not only reduces CVD risk factors (i.e., T2DM, HTN and dyslipidemia [257]), but also reduces the risk of MI, stroke, and all-cause mortality. [258, 259] Similar to anti-obesity drugs, bariatric surgery is performed in less than 1% of appropriate patients for which it is indicated. [260] Among the few medically eligible patients who receive treatment with bariatric surgery, significant disparities exist according to race, income, education level, and insurance type. [261]

1.6.3. Diagnosis and Treatment

Table 6 lists ten things to know about the diagnosis and treatment of increased body fat and CVD prevention.

Table 6.

Ten things to know about increased body fat and cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention

|

|

Sentinel Guidelines and References 2022 Anti-Obesity Medications and Investigational Agents: An Obesity Medicine Association Clinical Practice Statement [470]. 2020 Obesity in Adults: A Clinical Practice Guideline [272] 2015 Pharmacological Management of Obesity: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline [273] 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS Guideline for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults [240] |

1.7. CONSIDERATIONS OF SELECTED POPULATIONS (OLDER AGE, RACE/ETHNICITY, SEX DIFFERENCES)

1.7.1. Definition and Physiology

1.7.1.1. Older individuals

Older individuals (i.e., ≥ 75 years of age) vary considerably in their future risk for CVD and life expectancy. This variance in CVD risk and mortality is largely dependent on underlying co-morbidities, genetic predisposition, and degree of frailty. [274] Given the limitation of evidenced-based data among older individuals for the primary prevention of CVD, treatment recommendations are best determined by shared decision-making utilizing a patient-centered approach. [274, 31] Clinicians should tailor discussions to individual CVD risk factors, complexity of concurrent illnesses, considerations of the quality of life, and cost issues related to polypharmacy.[274] (Chart 1)

Chart 1.

Primary CVD prevention recommendations of statin use and diagnostic testing for adults ≥ 75 years of age: [31]

| 75 years or older | If LDL-C 70 – 189 mg/dL, then it may be reasonable to start with a moderate-intensity statin. If patients have demonstrable functional decline, multimorbidity, frailty, or reduced life-expectancy, then it may be reasonable to stop statin therapy in some cases |

| 75 – 80 years | If LDL-C 70 – 189 mg/dL, then it may be reasonable to measure coronary calcium to potentially reclassify those with CAC of zero to a lower ASCVD risk to potentially avoid statin therapy |

Race/Ethnicity

1.7.2. South Asian persons

make up over 20% of the world population. South Asian persons can be defined as those with ethnic roots originating from the Indian subcontinent (e.g., India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bangladesh). [275] That said, persons included in the term “South Asians” represents a heterogeneous population, with differences in diet, culture, and lifestyle among different South Asian populations and religions. Nonetheless, multiple studies have confirmed that South Asian persons have a 3- to 5-fold increase in the risk for myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death as compared with other ethnic groups. [276, 277] South Asian persons may be at increased CVD risk, largely due to increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome (even at a lower BMI), insulin resistance and adiposopathic dyslipidemia (sometimes called ‘‘atherogenic dyslipidemia”), which can be defined as elevated triglycerides, reduced HDL-C levels, increased LDL particle number, with an increased prevalence of smaller, more dense LDL particles, and increased lipoprotein(a), all which may increase CVD risk. [1] (See Chart 2) Those of Asian descent may also have increased risk of thrombosis as evidenced by increased plasminogen activator inhibitor, fibrinogen, lipoprotein (a), and homocysteine. Asian persons may have other factors that increase CVD risk such as impaired cerebrovascular autoregulation and sympathovagal activity, increased arterial stiffness, and endothelial dysfunction, [278, 279]

Chart 2.

| Metrics: physical exam and biomarkers | Desirable goal |

| Hemoglobin A1c | < 6% |

| Waist circumference | Female: < 31 inches (<80cm) Male: < 35 inches (< 90 cm) |

| Body mass index | < 23 kg/m2 |

| Lipoprotein (a) | < 100 nmol/L |

| Total cholesterol | < 160 mg/dL |

| Low density lipoprotein cholesterol | High risk: < 70 mg/dL Very high risk: <50 mg/dL Extreme risk: < 30 mg/dL |

| High density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) | Females: > 50 mg/dL Males: > 40 mg/dL |

| Triglycerides | < 150 mg/dL |

| Non-HDL-C | High risk: <100 mg/dL Very high risk: < 80 mg/dL Extreme risk: < 60 mg/dL |

* While the listed metrics are considered “desirable,” the cardiovascular disease benefits of drug therapy to improve some of these metrics await cardiovascular outcomes trials.

Having South Asia heritage is considered an ASCVD risk enhancing factor. [31] The “Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA)” evaluated a longitudinal cohort of South Asian persons in the United States. This study showed a disproportionately higher prevalent and incidence of T2DM in South Asian persons compared with other ethnic groups. [280] The same applies to ASCVD. After adjusting for ASCVD risk factors, South Asian persons may have greater coronary artery calcification progression than Chinese, Black males and Latino males but similar change to that of White males. [281]

1.7.3. African Americans

Have among the highest CVD rates of any US ethnic or racial group. African Americans often have more favorable selected lipid parameters compared with White Americans (e.g., higher HDL-C levels and lower triglyceride levels), and lower coronary artery calcium (CAC) than Whites. Conversely, African Americans have a higher prevalence of HTN, (including young African American females), [284] left ventricular hypertrophy, obesity, T2DM, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and elevated lipoprotein (a) levels. [285]

1.7.4. Hispanic/Latino individuals

often have elevated triglyceride and reduced HDL-C levels, and increased risk for insulin resistance. A ‘‘Hispanic Mortality Paradox’’ is sometimes described wherein the Hispanic/Latino population is reported as having a lower overall risk of mortality than non-Hispanic Whites and non-Hispanic Black persons (albeit higher risk of mortality than Asian Americans). [286] Nonetheless, CVD is the leading cause of death among Hispanics and the “Hispanic Paradox” may not apply to all Hispanic/Latino subpopulations. [287] Thus, to reduce CVD risk, Hispanic/Latino individuals should undergo diagnosis and treatment of CVD risk factors similar to other ethnicities / races. [288]

1.7.5. Native Americans

are defined as members of indigenous peoples of North, Central, and South America, with American Indians and Alaskan Natives often residing in North America. [289] In 2018, American Indians / Alaska Natives were 50% more likely to be diagnosed with CVD compared to White individuals, which may be related to a higher prevalence of CVD risk factors such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, HTN, and higher rates of cigarette smoking. [289] Pima (Akimel O'odham or “river people”) Indians are a subset of American Indians located in southern Arizona and northern Mexico. Pima Indians are reported to have a high rate of CVD risk factors (e.g., high prevalence of obesity, insulin resistance, T2DM, higher triglyceride levels, reduced HDL-C levels, and higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome).[290] Older literature suggests incident CVD events among Pima Indians may not be as high as predicted. [291] This is, in part, because in some cases compared to White individuals, untreated LDL-C levels may be lower among Pima males older than 30 and in females older than 25 years of age. [290] Despite a potential lower CVD risk compared to White persons, heart disease remains a major cause of mortality among Pima Indians, especially among those with concomitant renal failure.[292]

1.7.6. Females

with CVD risk factors are at increased risk for CVD events, directionally similar to males. CVD is the leading cause of mortality among females.[293] CVD accounts for up to 4 times as many deaths in females compared to breast cancer.[294] Compared to males, females are at higher risk for bleeding after invasive cardiac procedures, and are more predisposed to autoimmune/inflammatory disease, and fibromuscular dysplasia. This may potentially predispose females to myocardial infarction in the absence of atherosclerotic obstructive coronary arteries - especially among younger females. [295] According to the 2018 American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol, premature menopause and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (i.e., preeclampsia) are CVD risk enhancers. [31] Gestational diabetes and preterm delivery are also recognized as increasing lifetime CVD risk.

1.7.7. Epidemiology

-

•

Due to insufficient data (many CVD outcomes trials excluded older patients), the treatment recommendations for primary CVD risk reduction in individuals ≥ 75 years old often have less scientific support than treatment recommendations for younger age groups. Also, due to the population makeup of the supporting databases, CVD risk scores are only validated for individuals at or below 65, 75, or 80 years of age, depending upon the CVD risk assessment calculator. For example, the ACC/AHA ASCVD Risk Calculator includes an age range of 40 – 79 years. [296]

-

•

Many CVD risk calculators do not take into full account the influence of race on CVD risk. The ACC/AHA ASCVD Heart Risk Calculator is limited to the races of “Other” and African Americans. [296] Conversely, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) 10-year CHD risk tool includes Caucasians/Whites, Chinese, African Americans, and Hispanics individuals 45–85 years of age as data input, along with coronary artery calcification. [297]

-

•

CVD is the leading cause of death for females and males across most racial and ethnic groups in the US, accounting for ∼20% of deaths per year. [298]

-

•

African Americans ages 35-64 years are 50% more likely to have high blood pressure than Whites. African Americans ages 18-49 are 2 times as likely to die from heart disease than Whites. [299]

-

•

Compared to Whites , Hispanic/Latino individuals have 35% less heart disease, but a 50% higher death rate from diabetes, 24% more poorly controlled high blood pressure, and 23% more obesity.

-

•

Compared with US-born Hispanics/Latinos, foreign-born Hispanic/Latino individuals have about half as much heart disease; 29% less high blood pressure; and 45% more high total cholesterol. [300]

-

•

Compared to White adults, American Indians/Alaska Native adults have a higher prevalence of CVD risk factors such as obesity, high blood pressure, and current cigarette smoking. In 2018, American Indians/Alaska Natives had a 50 percent greater risk for coronary heart disease compared to non-Hispanic Whites.[289]

-

•

Heart disease is the leading cause of death for African American and White females in the US. Among American Indian and Alaska Native females, heart disease and cancer cause roughly the same number of deaths each year. [301]

-

•

Age and sex are important risk factors for stroke. One in 5 US females between 55 – 75 years of age will have a stroke in their lifetime. Stroke kills twice as many females as breast cancer. [302] Greater longevity in females helps account for strokes occurring more frequently in females than males; however, females may also have sex-specific stroke risk factors (e.g., exogenous hormones, and pregnancy-related hormone exposures). [303]

1.7.8. Diagnosis and Treatment

Table 7 lists ten things to know about the diagnosis and treatment of patients of older age, different races/ethnicities, and females.

Table 7.

Ten things to know about select populations (older age, race/ethnicity, sex differences) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention.

|

| Sentinel Guidelines and References 2020 The Use of Sex-Specific Factors in the Assessment of Women's Cardiovascular Risk [321, 31] 2020 US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. Minority Population Profiles. [289] 2017 Cardiovascular Health in African Americans: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. [285] 2016 Cardiovascular Disease in Women: Clinical Perspectives [293] 2014 American Heart Association Council on E, Prevention, American Heart Association Council on Clinical C, American Heart Association Council on C, Stroke N. Status of cardiovascular disease and stroke in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: a science advisory from the American Heart Association [288] |

1.8. THROMBOSIS

1.8.1. Definition and Physiology

Thrombosis is the intravascular (arterial or venous) coagulation of blood, resulting in a “blood clot” which may cause local or downstream obstruction of a vessel (i.e., thromboembolism). Atherosclerosis may lead to chronic luminal narrowing that obstructs on-demand blood flow, resulting in angina or claudication. Thromboembolic acute obstruction of a femoral vein may lead to an acute deep vein thrombosis and potential pulmonary embolism. Plaque rupture and acute thrombus formation obstructing a coronary artery may lead to a myocardial infarction; acute obstruction of a carotid artery may lead to a stroke. [322]

Risk factors for thrombosis include cigarette smoking, older age, atrial fibrillation, prosthetic heart valves, blood clotting disorders, trauma/fractures, physical inactivity (including prolonged bed rest / immobility), obesity, diabetes mellitus, HTN, dyslipidemia, certain drug treatments, [323] pregnancy, and cancer. Due to higher hormonal components, older oral contraceptives were associated with increased risk of thrombotic stroke. But even current combination oral contraceptives may somewhat increase the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke, especially oral contraceptives containing > 50 micrograms of estrogens. [324] Similarly, while the risk is small with currently recommended doses, long-term hormone therapy (i.e., estrogen with or without progestins) may mildly increase the risk of thromboembolism. [325] Anabolic androgenic steroid use for athletic “body building” increases the risk of increase of erythrocytes and hemoglobin concentration, thromboembolism, intracardiac thrombosis, stroke, cardiac dysrhythmias, atherosclerosis, concentric left-ventricular myocardial hypertrophy with impaired diastolic function and sudden cardiac death. [326] The data regarding stroke risk with testosterone replacement therapy in hypogonadal males is inconsistent, and thus the relationship of testosterone replacement therapy to stroke is unclear. [327]

One of the most common preventable contributors to thrombosis is tobacco cigarette smoking, [328]which is a well-known, major contributor to overall CVD morbidity and mortality, not just due to thrombosis alone.[329] Tobacco cigarette smoking increases CVD risk via inflammation, free radical formation, carbon monoxide-mediated increases in carboxyhemoglobin formation, increase in sympathetic activity (with increased myocardial oxygen demand and potential promotion of dysrhythmias), reduced nitric oxide with endothelial dysfunction, and oxidation of LDL-C. [329] Tobacco and tobacco-related products may also trigger pro-thrombotic processes, such as inflammation, oxidative stress, platelets reactivity, coagulation, and adverse effects upon the vascular endothelium. [328]

Vaping devices (electronic cigarettes or “e-cigarettes”) are battery-operated nicotine (as well as flavoring and other chemicals) delivery devices that generate an aerosol that is intended to be inhaled. Vitamin E acetate, an additive in some tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) - containing e-cigarette, or vaping, products, is strongly linked to “E-cigarette or Vaping product use-associated Lung Injury” (EVALI). Nicotine alone has the potential to adversely affect the cardiovascular system via an acute increase in the sympathetic nervous system, increase in blood pressure, decrease in coronary blood flow, increase in myocardial remodeling/fibrosis, promotion of dysrhythmias and promotion of thrombosis, with longer-term adverse effects on endothelial function, inflammation, lipid levels (i.e., reduced high density lipoprotein and increased LDL-C levels), blood pressure, and insulin resistance.[330]

Regarding primary prevention, it is uncertain if the benefits of aspirin exceed its risks. Guidelines recommend low-dose aspirin in select adults 40 – 70 years of age at high ASCVD risk, but not at increased risk of bleeding. [93] Regarding secondary prevention, a prior CVD event increases the risk of a future CVD event, often involving a thromboembolic component. Thus, patients with an acute coronary syndrome benefit from well-managed anti-thrombotic therapy as secondary prevention to reduce the risk of future CVD events. As a component of comprehensive cardiovascular secondary prevention, aspirin 81 – 325 mg per day is often beneficial and indicated for patients with history of CVD, stroke, or peripheral artery disease. [331] In addition to aspirin, a second anti-platelet agent may be warranted (i.e., dual antiplatelet therapy or DAPT). Overriding concepts and recommendations for DAPT cited by the “2016 ACC/AHA Guideline Focused Update on Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease” [332] include:

-

•

Unless contraindicated or otherwise not tolerated, aspirin therapy should be continued indefinitely in patients with coronary artery disease. Lower daily doses of aspirin, including in patients treated with DAPT, are associated with lower bleeding complications and comparable ischemic protection than higher doses of aspirin. The recommended daily dose of aspirin in patients treated with DAPT is 81 mg (range, 75 mg to 100 mg).

-

•

The addition of a P2Y12 inhibitor to aspirin monotherapy, as well as prolongation of DAPT, necessitates a fundamental tradeoff between decreasing ischemic risk and increasing bleeding risk.

-

•

Shorter-duration DAPT can be considered for patients at lower ischemic risk with high bleeding risk; longer-duration DAPT may be reasonable for patients at higher ischemic risk with lower bleeding risk. In most clinical settings, DAPT is recommended for at least 6–12 months after a coronary artery event.

1.8.2. Epidemiology

According to the US Centers for Disease Control: [333, 334, 335, 336, 337]

-

•

Stroke is a leading cause of serious long-term disability, reducing mobility in more than half of stroke survivors age 65 and over.

-

•

In the US, stroke is responsible for 1 out of 20 deaths.

-

•

About 90% of all strokes are ischemic strokes.

-

•

The risk of having a first stroke is nearly twice as high for Black as for White persons, and Black patients have the highest rate of death due to stroke.

-

•

Smoking is a leading cause of preventable death, accounting for 480,000 deaths a year.

-

•

In 2018, 13.7% of all adults (34.2 million people) smoked cigarettes: 15.6% of males and 12.0% of females.

-

•

Cigarette smoking has a dose-response relationship with stroke. [338]

-

•

E-cigarettes are the most frequently used tobacco product among youths. Roughly 5% of middle school students and 20% of high school students report using e-cigarettes. [337]

1.8.3. Diagnosis and Treatment

Table 8 lists ten things to know about the diagnosis and treatment of thrombosis and CVD prevention.

Table 8.

Ten things to know about thrombosis and cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention

|

|

Sentinel Guidelines and References 2022 Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes [191] 2020 Smoking Cessation. A Report from the Surgeon General [376] 2020 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-Update: A Report From the American Heart Association [377] 2018 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Tobacco Cessation Treatment [378] 2016: 2016 ACC/AHA Guideline Focused Update on Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease [332] |

1.9. KIDNEY DYSFUNCTION

1.9.1. Definition and Physiology

According to the “Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes” (KDIGO) guidelines, [379] chronic kidney disease (CKD) is defined as persistently elevated urine albumin excretion [≥30 mg/g (≥3mg/mmol) creatinine], persistently reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2), or both, for greater than 3 months . [380]

A bidirectional relationship exists between CVD and CKD, with each worsening the status of the other. Both have similar “traditional” risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and cigarette smoking. Beyond these shared risk factors, CKD remains an independent risk factor for CVD. This is likely due to the CKD-mediated adverse effects on the cardiovascular system, such as worsened endothelial dysfunction, accelerated atherosclerosis,[381] increased inflammation, vascular calcification and other vasculopathies, [382] left ventricular hypertrophy, anemia, abnormal calcium-phosphate metabolism, and increased systemic toxins such as elevated urate levels (i.e., uremia). [383]

Over 2/3rd of patients over 65 years with CKD have concomitant CVD. [384] Both eGFR < 60 mg/min/1.73 m2 and albuminuria are independent predictors of CVD events and CVD mortality. [385] CVD incidence is inversely related to eGFR. Generally, CKD and ESKD are associated with a 5 – 10 fold higher risk for developing CVD compared to aged matched controls. [386] Specifically, patients with CKD having eGFR 15-60 mg/min/1.73 m2 have about two to three times higher risk of CVD mortality, compared to patients without CKD. [385, 387] As such, CKD is considered a “risk enhancing factor” that places patients at high risk for CVD. [31]

1.9.2. Epidemiology

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and The Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics 2021 Update from the American Heart Association: [388, 389, 390]

-

•

Generally, more than 1 in 7 (approximately 15% of US adults or 37 million people) are estimated to have CKD. Specifically, the overall prevalence of chronic kidney disease (estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL•min−1•1.73 m−2 or albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g) was 14.8% in 2013–2016.

-

•

As many as 9 in 10 adults with CKD do not know they have CKD.

-

•

About 2 in 5 adults with severe CKD do not know they have CKD.

-

•

CKD is more common in people aged 65 years or older (38%) than in people aged 45–64 years (12%) or 18–44 years (6%).

-

•

CKD is more common in non-Hispanic Black adults (16%) than in non-Hispanic White adults (13%) or non-Hispanic Asian adults (13%).

-

•

About 14% of Hispanic adults have CKD.

-

•

Incidence of end-stage kidney disease in the United States is projected to increase 11% to 18% through 2030.

-

•

In US adults aged 18 years or older, diabetes mellitus and high blood pressure are the main reported causes of ESKD and the prevalence of CKD is about 37% of adults with diabetes mellitus and 31% among adults with high blood pressure. [204]

-

•

In US children and adolescents younger than 18 years, polycystic kidney disease and glomerulonephritis (inflammation of the kidneys) are the main causes of ESKD.

-

•

CKD may be associated with an increased risk of heart failure. The excess risk of heart failure is especially increased African American and Hispanic individuals. [391]

-

•

Creatinine-based estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and/or albuminuria (either by semi-quantitative dipstick for proteinuria or albumin-to-creatinine ratio) may improve cardiovascular risk classification. [392]

-

•

CKD is often associated with low rates of standard preventive therapies directed towards CVD risk reduction (e.g., adequate control of glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol). [393] For example, in an analysis of patients with CKD evaluated from 2003 – 2007, only 50% were taking statins, and 42% who had statins recommended were not taking them. [394] Even when treated with statins, patients with CKD rarely achieve LDL-C treatment goals. [395]

1.9.3. Diagnosis and Treatment

Table 9 lists ten things to know about the diagnosis and treatment of kidney dysfunction and CVD prevention.

Table 9.

Ten things to know about kidney disease and cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention

|

|

Sentinel Guidelines and References 2021 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics – Update: A Report from the American Heart Association [377, 390] 2020 Cardiorenal Protection With the Newer Antidiabetes Agents in Patients with Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease: A Statement from the American Heart Association [204] 2019 Clinical Pharmacology of Antihypertensive Therapy for the Treatment of Hypertension in CKD [407] 2019 Chronic Kidney Disease Diagnosis and Management: A Review. [436] 2019 Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease [399] |

1.10. FAMILY HISTORY, GENETIC ABNORMALITIES, AND FAMILIAL HYPERCHOLESTEROLEMIA

1.10.1. Definition and Physiology

Obtaining a family history of cardiovascular disease helps identify and stratify CVD risk. Beyond atherosclerotic CVD, among the more common inherited causes of other forms of CVD among younger individuals include genetic abnormalities leading to vasculopathies, valvulopathies, aneurysmal disorders, and coagulopathies. [437] Regarding atherosclerosis, underlying genetic disorders may contribute to atherosclerotic CVD. Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia (HeFH) is the most common genetic disorder resulting in severe elevations in LDL-C (i.e., typically with LDL-C levels ≥ 190 mg/dL), with a reported U.S. prevalence of 1/200 to 1/500. Patients with FH are at high risk for premature CVD, attributable not only to the degree of elevation in atherogenic lipoprotein cholesterol levels, but also because of the cumulative lifetime exposure to increased LDL-C levels. [438]Management of HeFH includes aggressive cholesterol lowering at an early age, usually involving statin therapy. [439]

Laboratory diagnosis of inherited dyslipidemias may involve sequencing the entire human genome or custom sequencing of one or more genes. In some countries, it is common for patients with marked elevations in LDL-C levels to undergo genetic evaluation for FH to identify pathogenic variants of the LDL receptor (i.e., most common), apolipoprotein B (APOB), or proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9). [440, 441] However, in addition to laboratory genetic testing, the diagnosis of Familial Hypercholesterolemia can also be made clinically. In the US, FH is more commonly assessed via one or more clinical diagnostic criteria for FH such as The American Heart Association, Simon Broome, and/or Dutch Lipid Clinic Network criteria (see tables 10a–b, 10c). [442, 443, 444, 445, 446]

Table 10a.

American Heart Association Clinical Criteria for the Diagnosis of Heterozygous FH [443]

| • Low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) ≥190 mg/dL (5 mmol/L) among adults or LDL-C ≥ 160mg/dL (4 mmol/L) among children |

| PLUS EITHER |

| • First degree relative with LDL-C ≥190 mg/dL |

| OR |

| • First degree relative with known premature coronary heart disease (<55 years among males; <60 years among females) |

| OR |

| • First degree relative with positive genetic testing for an LDL-C-raising gene defect (LDL receptor, apoB, or PCSK9) |

Table 10b.

| Definite Familial Hypercholesterolemia: |

| • Adult with total cholesterol levels ≥ 290 mg/dL (> 7.5 mmol/L) or LDL-C ≥ 190 mg/dL (> 4.9 mmol/L) |

| • Child < 16 years of age with total cholesterol levels ≥ 260 mg/dL (> 6.7 mmol/L) or LDL-C ≥ 155 mg/dL (> 4.0 mmol/L) |

| PLUS EITHER |

| • Tendon xanthomas in the patient, or tendon xanthomas in a first degree relative (parent, sibling or child) or second degree relative (grandparent, aunt, or uncle) |

| OR |

| • Deoxynucleic acid based evidence of an LDL receptor mutation, familial defective apo B-100, or a PCSK9 mutation |

| Possible Familial Hypercholesterolemia: |

| • Adult with total cholesterol levels ≥ 290 mg/dL (>7.5 mmol/L) or LDL-C ≥ 190 mg/dL (>4.9 mmol/L) |

| • Child < 16 years of age with total cholesterol levels ≥ 260 mg/dL (>6.7 mmol/L) or LDL-C ≥ 155 mg/dL (>4.0 mmol/L) |

| PLUS AT LEAST ONE OF THE FOLLOWING: |

| • Family history of myocardial infarction in first degree relative < age 60 years |

| or second-degree relative < age 50 years |

| • Family history of an adult first- or second-degree relative with elevated total cholesterol ≥ 290 mg/dL (>7.5 mmol/L) or a child, brother or sister aged < 16 years with total cholesterol ≥ 260 mg/dL (> 6.7 mmol/L) |

Table 10c.

Dutch Lipid Clinic Network diagnostic criteria for Familial Hypercholesterolemia [451, 446, 444, 446]

|

Points |

|||

| Criteria | |||

| Family history | |||

| First-degree relative with known premature* coronary and vascular disease, OR | 1 | ||

| First-degree relative with known LDL-C level above the 95th percentile | |||

| First-degree relative with tendinous xanthomata and/or arcus cornealis, OR | 2 | ||

| Children aged less than 18 years with LDL-C level above the 95th percentile | |||

| Clinical history | |||

| Patient with premature* coronary artery disease | 2 | ||

| Patient with premature* cerebral or peripheral vascular disease | 1 | ||

| Physical examination | |||

| Tendinous xanthomata | 6 | ||

| Arcus cornealis prior to age 45 years | 4 | ||

| Untreated Cholesterol levels mg/dl (mmol/liter) | |||

| LDL-C ≥ 330 mg/dL (≥ 8.5) | 8 | ||

| LDL-C 250 – 329 mg/dL (6.5–8.4) | 5 | ||

| LDL-C 190 – 249 mg/dL (5.0–6.4) | 3 | ||

| LDL-C 155 – 189 mg/dL (4.0–4.9) | 1 | ||

| DNA analysis | |||

| Functional mutation in the LDLR, apo B or PCSK9 gene | 8 | ||

| Diagnosis (diagnosis is based on the total number of points obtained) | |||

| Definite Familial Hypercholesterolemia | >8 | ||

| Probable Familial Hypercholesterolemia | 6 – 8 | ||

| Possible Familial Hypercholesterolemia | 3 – 5 | ||

| Unlikely Familial Hypercholesterolemia | <3 | ||

* Premature coronary and vascular disease = < 55 years in males; < 60 years in females

LDL-C = low - density lipoprotein cholesterol

DNA = Deoxynucleic acid

LDL-R = low - density lipoprotein receptor

Apo B = apolipoprotein B

PCSK9 = Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9

Among patients without FH, an elevated lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] level is an independent CVD risk factor [152] and a prominent monogenic cause of atherosclerotic CVD, with 70 - > 90% of interindividual heterogeneity being genetically determined. [447] The worldwide prevalence of elevated Lp(a) levels is estimated at approximately 20%, is independent of nutrition or physical activity (i.e., elevated Lp(a) levels are often described as > 50 mg/dL or >125 nmol/L), [448] and remains stable over a patient's lifetime. [152, 447] The European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemias suggest that Lp(a) measurement should be considered at least once in each adult person's lifetime to identify those with very high inherited Lp(a) levels >180 mg/dL (>430 nmol/L), who may have a lifetime risk of ASCVD equivalent to the risk associated with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. [139] Table 3 summarizes current therapeutic considerations for elevated Lp(a) levels.

Measurement of Lp(a) is superior to genetic testing for an LPA variant, as current genetic testing for this variant is not a reliable predictor of elevated Lp(a) levels in all ethnic groups. In addition to identification of monogenic disorders, genetic testing may allow for the calculation of a “polygenic risk score” to complement clinical risk scores used to predict ASCVD events. [449, 450, 440] However, the role of these “polygenic risk scores” in primary and secondary prevention of CVD is still evolving.

1.10.2. Epidemiology

-

•

The worldwide prevalence of FH is estimated as 1:313 among subjects in the general population, 10-fold higher among those with ischemic heart disease (IHD), 20-fold higher among those with premature IHD, and 23-fold higher among those with severe hypercholesterolemia. [452]

-

•

In the US, heterozygous FH (as defined by the Dutch Lipid Clinic criteria) occurs in approximately 1:250 individuals, [453] with an increased rate among those having Lebanese, South African Afrikaner, South African (Ashkenazi) Jewish, South African Indian, French Canadian, Finland, Tunisia, and Denmark population backgrounds. [454]

-

•

The risk of premature coronary heart disease (CHD) is increased by 20 fold among untreated FH patients [455] and CHD typically occurs before age 55 and 60 among females and males with FH respectively. [446]

-

•

Myocardial infarction occurs about 20 years earlier among those with FH compared to those without FH,[456] and occurs in up to 1 in 7 of patients having acute coronary syndrome < 45 years of age. [457]

1.10.3. Diagnosis and Treatment

Table 10d lists ten things to know about the diagnosis and treatment of family history/genetics/familial hypercholesterolemia and CVD prevention.

TABLE 10d.

Ten things to know about family history/genetics/familial hypercholesterolemia and cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention

|

|

Sentinel Guidelines and References 2020 Genetic Testing in Dyslipidemia: A Scientific Statement from the National Lipid Association [441] 2018 Clinical Genetic Testing for Familial Hypercholesterolemia: JACC Scientific Expert Panel [440] 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. [31] 2018 Familial hypercholesterolemia treatments: Guidelines and new therapies. [439] 2017 Cascade Screening for Familial Hypercholesterolemia and the Use of Genetic Testing [461] |

1.10.4. Conclusion