Abstract

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), a ligand-activated nuclear receptor critical for systemic lipid homeostasis, has been shown closely related to cardiac remodeling. However, the roles of cardiomyocyte PPARα in pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling remains unclear because of lacking a cardiomyocyte-specific Ppara-deficient (PparaΔCM) mouse model. This study aimed to determine the specific role of cardiomyocyte PPARα in transverse aortic constriction (TAC)-induced cardiac remodeling using an inducible PparaΔCM mouse model. PparaΔCM and Pparafl/fl mice were randomly subjected to sham or TAC for 2 weeks. Cardiomyocyte PPARα deficiency accelerated TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. Transcriptome analysis showed that genes related to fatty acid metabolism were dramatically downregulated, but genes critical for glycolysis were markedly upregulated in PparaΔCM hearts. Moreover, the hypertrophy-related genes, including genes involved in extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, cell adhesion, and cell migration, were upregulated in hypertrophic PparaΔCM hearts. Western blot analyses demonstrated an increased HIF1α protein level in hypertrophic PparaΔCM hearts. PET/CT analyses showed an enhanced glucose uptake in hypertrophic PparaΔCM hearts. Bioenergetic analyses further revealed that both basal and maximal oxygen consumption rates and ATP production were significantly increased in hypertrophic Pparafl/fl hearts; however, these increases were markedly blunted in PparaΔCM hearts. In contrast, hypertrophic PparaΔCM hearts exhibited enhanced extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) capacity, as reflected by increased basal ECAR and glycolysis but decreased glycolytic reserve. These results suggest that cardiomyocyte PPARα is crucial for the homeostasis of both energy metabolism and ECM during TAC-induced cardiac remodeling, thus providing new insights into potential therapeutics of cardiac remodeling-related diseases.

Keywords: cardiac remodeling, PPARα, lipid metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, glycolysis, fibrosis

Introduction

Pathological remodeling of the heart in response to pressure or volume overload includes the development of cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, and inflammation. Although cardiac remodeling provides short-term benefits, such as reducing wall stress and preserving cardiac function, it becomes maladaptive and progresses to heart failure in the long term [1].

Cardiac metabolism changes are the substantive bases for the development of cardiac remodeling [2]. The heart is an organ with high energy demands to meet sustained cardiac contractile function. Under physiological conditions, the majority (60%–90%) of myocardial energy sources are derived from fatty acid oxidation (FAO), and the remaining 10%–40% come from glucose, pyruvate, and lactate [3]. Under pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling, the energy source switches from FAO to an increased reliance on glucose utilization, which is also known as metabolic reprogramming [4]. However, how metabolic reprogramming is precisely governed during cardiac remodeling remains largely unknown [5].

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) is a master regulator of FAO and systemic metabolic homeostasis and belongs to the nuclear receptor superfamily. For example, when binding with its ligands, endogenous ligand fatty acids (FAs), and exogenous ligand fibrate drugs, PPARα is activated, heterodimerizes with the retinoid X receptor, binds to the PPAR response element on the promoter of target genes, and subsequently promotes FA uptake, transport, and β-oxidation [6, 7]. Numerous studies have shown that PPARα downregulation results in impaired FAO in heart failure. However, there is a reason to believe that the regulatory mechanisms of PPARα in cardiac remodeling are extremely complex. First, impaired FAO in heart failure does not always in parallel with PPARα expression levels [8–12]. Second, the role of PPARα in cardiac function seems controversial. Studies using PPARα whole-body-knockout (Ppara–/–) mice showed that PPARα deficiency led to impaired FAO and exacerbated cardiac dysfunction upon transverse aortic constriction (TAC) challenge, whereas cardiomyocyte-specific constitutive overexpression of PPARα also induced cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure, similar to diabetic cardiomyopathy [13–15]. Third, the effects of exogenous agonists, such as Wy-14643, on cardiac function seemed to be dependent on the pathological stage of heart failure [16, 17]. Hence, the molecular mechanisms through which PPARα regulates cardiac remodeling remain to be elucidated. Use of cardiac-specific Ppara-deficient mice may help in determining the precise role of cardiomyocyte PPARα in TAC-induced cardiac remodeling.

In this study, to better investigate the effects of cardiomyocyte PPARα during cardiac remodeling, an inducible cardiomyocyte-specific Ppara-deficient (PparaΔCM) mouse strain was generated and subjected to TAC. PparaΔCM mice exhibited exacerbated cardiac remodeling in response to TAC. Transcriptome analysis delineated impaired FAO but enhanced glucose metabolism and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling in hypertrophic PparaΔCM mice, which was confirmed by PET/CT analysis of glucose utilization and bioenergetic analysis of mitochondrial function. Taken together, the results of this study reveal the precise roles of cardiomyocyte PPARα in maintaining both cardiac energy metabolism and ECM homeostasis in response to pressure overload.

Materials and methods

Animals and treatment

C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) mice were purchased from Charles River Company (Beijing, China). Pparafl/fl mice with a C57BL/6J background were described previously [18]. For temporal cardiomyocyte-specific Ppara disruption, Pparafl/fl mice were crossed with mice harboring the Cre-ERT2 recombinase driven by the Myh6 promoter (designated Myh6-ERT2Cre) [19], which were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (JAX, Bar Harbor, ME, USA), to generate Pparafl/fl; Myh6-ERT2Cre mice and littermate control Pparafl/fl mice. For activation of Myh6-ERT2Cre-driven Cre recombinase, 6- to 7-week-old male Pparafl/fl; Myh6-ERT2Cre and Pparafl/fl mice were intraperitoneally injected with tamoxifen (TAM, 20 mg·kg–1·d–1 in corn oil, T5648, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 5 days. Two weeks after the completion of tamoxifen injection, all mice were randomly subjected to sham or TAC surgery. Pparafl/fl; Myh6-ERT2Cre mice treated with TAM were designated PparaΔCM mice. All mice were kept on a standard 12-h light/dark cycle with free access to a normal chow diet and water. All experimental procedures conformed to the US National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved under a project license (AEEI-2018-127) granted by the ethics board of Capital Medical University.

Transverse aortic constriction (TAC)-induced cardiac remodeling model

To confirm the changes in the PPARα pathway in TAC-induced cardiac remodeling, 8- to 10-week-old male WT mice were randomized to receive TAC or sham surgery. To study the role of cardiac PPARα in cardiac remodeling, 8- to 10-week-old male Pparafl/fl and PparaΔCM mice, for which tamoxifen injections had been completed for 2 weeks, were randomized to receive TAC or sham surgery. A minimally invasive TAC method without standard chest opening has been established [20]. Mice were anesthetized with a single intraperitoneal injection of supersaturated tribromoethanol (T48402, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) saline solution at a dose of 10–13 μL/g and fixed on an operation plate. Adequate sedation was determined by a lack of toe-pinch reflex. A topical depilatory agent was applied to the neck and chest, and the area was cleaned with 75% alcohol. Under a dissecting microscope (Model SZ2-ILST, OLYMPUS Corporation, TOKYO, Japan), the mouse was placed in the supine position, and a midline cervical incision was made to expose the sternocleidomastoid muscle above the trachea by microsurgical techniques. Then, the sternocleidomastoid muscles were bluntly dissociated and separated. Next, the sternum stem was cut along the midline and slightly bluntly separated, and the thymus covering the aortic arch was bluntly separated from the aortic arch. Finally, the aortic arch was fully exposed by a hook. TAC was performed by placing a 7-0 nylon suture between the innominate and left common carotid artery ligatures with a 25-gauge needle to yield a narrowing 0.5 mm in diameter when the needle was removed. The skin was closed, and the mice were allowed to recover on a warming pad until they were fully awake. The sham group was subjected to an identical operation in which the aortic arch was visualized but not banded. Aortic flow peak velocity (AV Peak Vel) at the TAC constriction band site was measured using PW Doppler (Vevo 2100; VisualSonics, Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada) to confirm significant aortic constriction (AV Peak Vel >2800 mm/s). The mortality of the mice in the perioperative period (24 h) and 1 week after surgery was <1% using the TAC method.

Echocardiography

Two weeks after surgery, cardiac function was evaluated by echocardiography using a high-resolution small-animal imaging system (Vevo 2100; VisualSonics, Toronto, ON, Canada) as described [21]. Briefly, mice were shaved and anesthetized with isoflurane (2%–4% for induction, 1%–1.5% for maintenance) and were placed in the supine position on a heated platform with ECG electrodes attached to monitor the heart rate (HR). B-Mode and M-Mode of parasternal long and short axis were measured at the level of the papillary muscles, and the following parameters were measured digitally from the M-mode tracings: HR, diastolic and systolic left ventricular anterior wall, diastolic and systolic left ventricular internal dimensions, diastolic and systolic left ventricular posterior wall using Vevo LAB 2.1.0 software. Based on these measurements, diastolic and systolic left ventricular volume, left ventricular ejection fraction (EF), and left ventricular fractional shortening (FS) were calculated. AV Peak Vel at the TAC constriction band site was also measured using PW Doppler.

FDG-PET/CT scanning

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scanning was performed at 2 weeks post surgery after the mice were fasted for 12 h with free access to water. After initial kinetic data were obtained, mice were administered 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) 7.86 ± 0.40 MBq via lateral tail vein injection and then returned to individual holding cages. Following the determination of body weight (25.58 ± 0.51 g), the mice were anesthetized using isoflurane (4% for induction, 1%–1.5% for maintenance) after a 45 min 18F-FDG uptake period. Subsequently, 20 min of scans were obtained using an Inveon small-animal PET/CT/SPECT imaging system (Siemens Molecular Imaging, Knoxville, TN, USA). In the same workflow, a CT image was acquired for attenuation correction purposes. Images were reconstructed using a three-dimensional OP-MAP algorithm (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc., Malvern, PA, USA). Scanner reconstruction using this algorithm was calibrated to a National Institute of Standards and Technology traceable positron-emitting dose calibrator source to ensure quantitative accuracy. The mean standardized uptake values of the mouse hearts were calculated using Inveon Research Workplace 4.2 (Siemens Molecular Imaging, Knoxville, TN, USA) [22].

Bioenergetic flux assessment

To assess the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) in Pparafl/fl and PparaΔCM hearts upon TAC, heart slices were obtained. Hearts were isolated and placed in a sterile container with cold (4 °C) oxygenated modified Tyrode’s cutting solution (NaCl, 130 mM; KCl, 5 mM; NaH2PO4, 0.5 mM; MgCl2, 1 mM; HEPES, 10 mM; 2,3-butanedione monoxime (BDM), 10 mM; CaCl2, 1.4 mM; and glucose, 10 mM; pH 7.4). Then, the left ventricle was separated and placed on a 4% agar bed on top of the specimen holder with the epicardium glued to the agar bed using Histoacryl blue tissue glue with the endocardium facing up. The tissue block holder was placed on the cutting chamber of a vibrating microtome (DTK-1000N; DOSAKA, Japan). The cutting chamber was filled with modified cold (4 °C) oxygenated Tyrode’s cutting solution. Prior to tissue slicing, the vibrating microtome was preset to cut a slice with 250 μm thickness at 0.07 mm/s advance speed and 80 Hz vibration frequency at 2 mm horizontal vibration amplitude [23]. Following heart slicing, each slice was transferred immediately to a sterile container with oxygenated washout Tyrode’s solution maintained at room temperature (NaCl, 130 mM; KCl, 5 mM; NaH2PO4, 0.5 mM; MgCl2, 1 mM; HEPES, 10 mM; CaCl2, 1.4 mM; glucose, 10 mM; pH 7.4) and then punched with a 2 mm diameter tissue puncher. Heart slices that were 2 mm in diameter were maintained in Tyrode’s washing solution for at least 40 min to wash out the BDM and warm the tissue to room temperature.

The bioenergetics of heart slices were measured using an Agilent Seahorse Bioscience XFe24 Analyzer with Seahorse XFe24 Islet Capture FluxPak (Agilent Technologies Inc., California, USA) according to the manufacturers’ instructions [24, 25]. The 2-mm-diameter slices were transferred to an Islet Capture Plate and incubated with 500 μL of prewarmed assay medium (for the OCR measurement, XF DMEM base medium supplemented with 5.55 mM glucose and 0.7 mM L-glutamine, and for the ECAR measurement, XF DMEM base medium supplemented with 0.7 mM L-glutamine; pH 7.4) in a non-CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 1 h. Meantime, 50 µM oligomycin, 20 µM 4-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP), 20 µM rotenone/antimycin A (Rot/AA) (for the OCR measurement), 30 mM glucose, 50 µM oligomycin, and 50 mM 2-deoxyglucose (for the ECAR measurement) were prepared and loaded into the injection ports in the XFe24 sensor cartridge. Following microplate insertion, the XFe24 protocol consisted of baseline and stepwise injection measurements (3 min for mixture, 4 min for incubation, and 3 min for measurement for a total of six cycles). Datasets were processed using XFe24 software and analyzed with GraphPad Prism software.

Morphological analyses

Heart tissues were fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin and sectioned (4 μm). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson’s trichrome, and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) staining were performed on the sections using standard procedures as previously described [21]. Images were obtained using a high-capacity digital slide scanner (Pannoramic SCAN, 3DHISTECH, Budapest, HUN). The fibrotic area dyed by Masson’s trichrome staining (collagen area/total area) and cross-sectional area of the cardiomyocytes were determined using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA in the heart tissues was extracted by the TRIzol reagent method (Invitrogen, New York, USA). The first strand of cDNA was synthesized from 2 µg of total RNA using the GoScriptTM Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Southampton, UK). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan) with CFX Connect Real-Time System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Amplification was performed at 95 °C for 3 min, 95 °C for 45 s, and 60 °C for 40 s for each step of 40 cycles. The mRNA levels were normalized to the level of the endogenous housekeeping gene Actb and calculated with the comparative cycle threshold (ΔΔCT) method. All primers are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Western blot analysis

For nuclear extracts, heart tissues were lysed by NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The protein concentration was determined using a PierceTM BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Fifty micrograms of protein lysates were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) using a Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat milk and incubated overnight with primary antibodies against PPARα (1:1000, ab97609; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) or hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α, 1:1000, 14179; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) at 4 °C. The membranes were then washed three times with TBST and incubated with anti-mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (7076S, 7074S; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were visualized with a chemiluminescence detection kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) on a FluorChem E imaging system (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA, USA). The relative protein levels of PPARα and HIF1α were quantified with Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA) and normalized to the level of LAMIN B1 (1:5000, ab133741; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA).

Transcriptome and bioinformatics analyses

For microarray profiling, total RNA was harvested from heart tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Canada) and purified using a RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The amount and quality of the RNA were determined using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo, NanoDrop 2000, USA) at an absorbance of 260 nm. mRNA expression profiling was performed using a mouse transcriptome array (Affymetrix GeneChip, Santa Clara CA, USA), which contained 65,957 gene-level probe sets. The microarray analysis was performed with Affymetrix Expression Console Software (version 1.2.1). Raw data (CEL files) were normalized at the transcript level using the robust multiarray average method (RMA workflow). The median of transcript expression was calculated. Gene-level data were then filtered such that only those probe sets in the “core” meta probe list, which represents Ref-Seq genes, were retained. For the microarray data analysis, differentially expressed mRNAs were identified based on a random variance model t-test [21]. The differentially expressed genes had a |fold change| > 1.5 and P value <0.05. Messenger RNAs with similar expression patterns often facilitate overlapping functions. Accordingly, cluster analysis of gene expression patterns was performed with by Cluster and Java Tree viewer software. Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed to identify the main functions of the differentially expressed genes according to the GO project. Pathway analysis was performed to determine the significant pathways enriched with differentially expressed genes according to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database. Fisher’s exact test was performed to determine the significant GO terms and pathways, and the threshold of significance was considered to be a P value <0.05.

Statistical analyses

All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM and were calculated and plotted using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). For statistical comparisons, the determination of normal distributed data was first evaluated. Then potentially similar variances were evaluated in normally distributed data. Student’s t-tests were performed for two-group comparisons, and ANOVAs were performed for the comparison of groups for which similar variance tests were passed. Nonparametric tests were used where data were not normally distributed. To compare multiple groups with more than one variable, two-way ANOVAs followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test were performed. In all cases, significance was attributed to differences for which the two-tailed probability was <0.05.

Results

The expression of PPARα and its classical target genes was decreased during TAC-induced cardiac remodeling

PPARα has a high expression level and plays a critical role in energy metabolism during pathological cardiac remodeling. To confirm the expression of PPARα in short-term TAC-induced cardiac remodeling, WT mice were subjected to TAC or sham surgery for 2 weeks. As expected, the level of Ppara mRNA was decreased in the heart after TAC treatment compared with the level in the sham-operated heart (Supplementary Fig. S1a). The expression of PPARα classical target genes CD36 molecule (Cd36), carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1b (Cpt1b), and acyl-CoA oxidase 1 (Acox1) mRNAs was also decreased after TAC (Supplementary Fig. S1b). These results are consistent with those in previous reports [8].

Generation of temporal cardiomyocyte-specific Ppara-deficient mice

To distinguish the cardiomyocyte-specific effects of PPARα from the systemic effects of PPARα, inducible cardiomyocyte-specific Ppara-deficient (PparaΔCM) mice were generated by crossing Pparafl/fl mice with Myh6-ERT2Cre mice (Supplementary Fig. S2a). Six- to seven-week-old male Pparafl/fl; Myh6-ERT2Cre and littermate control Pparafl/fl mice were intraperitoneally injected with tamoxifen (20 mg·kg–1d–1) or vehicle (corn oil) for 5 days. Two weeks after completion of the injection series, only the heart tissues from PparaΔCM mice, not the other tissues, exhibited diminished Ppara mRNA (Supplementary Fig. S2b) and PPARα protein levels (Supplementary Fig. S2c), indicating the successful construction of an inducible cardiomyocyte-specific Ppara-deficient mouse model.

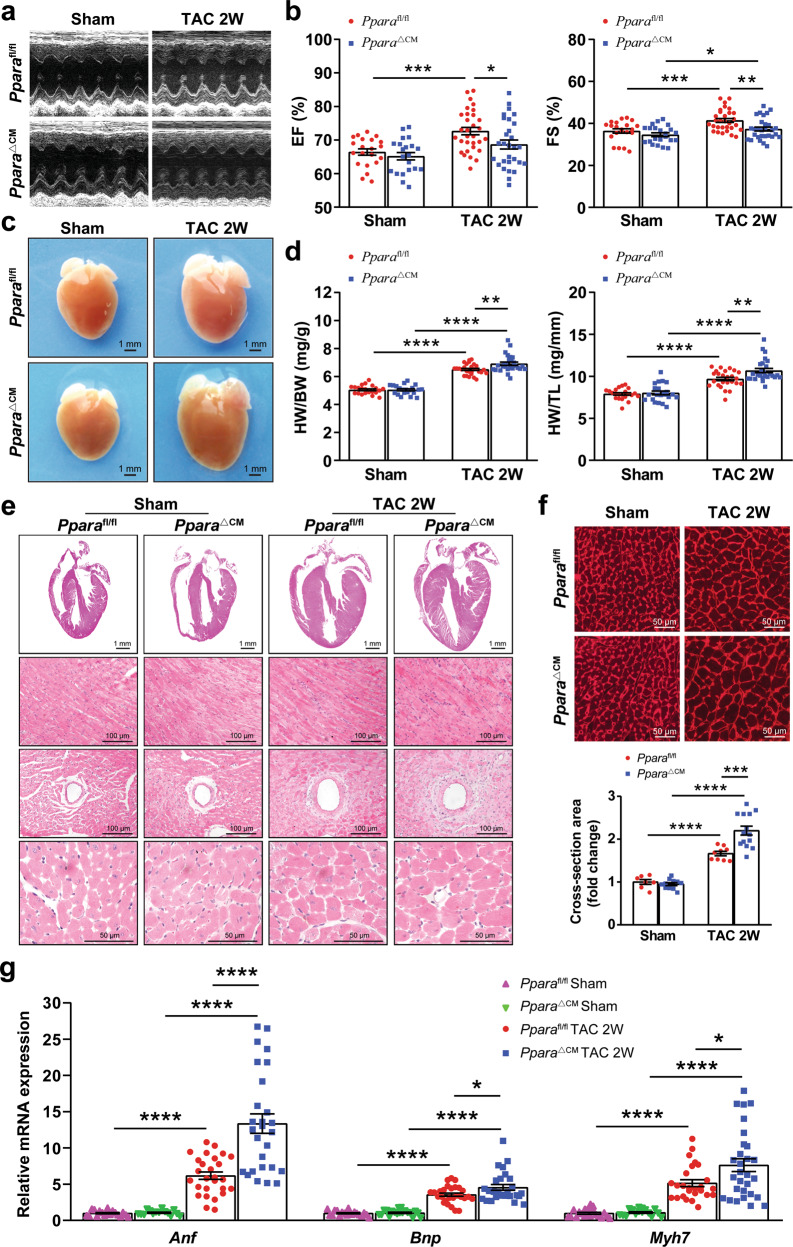

Cardiomyocyte PPARα deficiency accelerated TAC-induced cardiac remodeling and contractile dysfunction

To explore the role of cardiomyocyte PPARα in the early stage of pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling, PparaΔCM and Pparafl/fl mice were subjected to TAC or sham surgery for 2 weeks. Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) and Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon tests were performed to compare the survival rate between Pparafl/fl and PparaΔCM mice upon surgery; however, no difference was found between these groups (Supplementary Fig. S3). Echocardiographic analyses showed that the compensation of cardiac contractile function was impaired in the PparaΔCM mice compared with that in the Pparafl/fl mice in response to TAC, as reflected by a trend toward a decompensatory decrease in EF% and FS% in the PparaΔCM mice (Fig. 1a, b and Supplementary Table S2). Morphologically, the PparaΔCM hearts were visually larger than the Pparafl/fl hearts upon TAC (Fig. 1c), consistent with the increased heart weight/body weight ratio and heart weight/tibial length ratio (Fig. 1d). Histologically, H&E and WGA staining showed that cardiomyocytes were larger in the hypertrophic PparaΔCM hearts than in the hypertrophic Pparafl/fl hearts (Fig. 1e, f). Furthermore, qPCR analysis revealed that fetal genes reflecting cardiac hypertrophy, such as atrial natriuretic factor (Anf), brain natriuretic peptide (Bnp), and β-myosin heavy chain (Myh7), were dramatically augmented in the hypertrophic PparaΔCM hearts (Fig. 1g), indicating that cardiomyocyte PPARα deficiency accelerates TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy.

Fig. 1. Cardiomyocyte PPARα deficiency accelerated TAC-induced cardiac remodeling and contractile dysfunction.

Pparafl/fl and PparaΔCM mice were subjected to TAC or sham surgery for 2 weeks. a Representative two-dimensional guided M-mode echocardiogram of the left ventricle. b Quantification of ejection fraction (EF%) and fractional shortening (FS%) (n = 21–31). c Representative gross heart of the mice. d Heart weight/body weight (HW/BW) ratios and heart weight/tibial length (HW/TL) ratios (n = 21–28). e Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of heart sections. f Representative images of wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) staining of heart sections (top). Quantification of cross-sectional areas of cardiomyocytes (bottom, n = 7–14). g Expression of the fetal genes atrial natriuretic factor (Anf), brain natriuretic peptide (Bnp), and β-myosin heavy chain (Myh7) in mouse hearts was quantified by qPCR (n = 15–29). The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

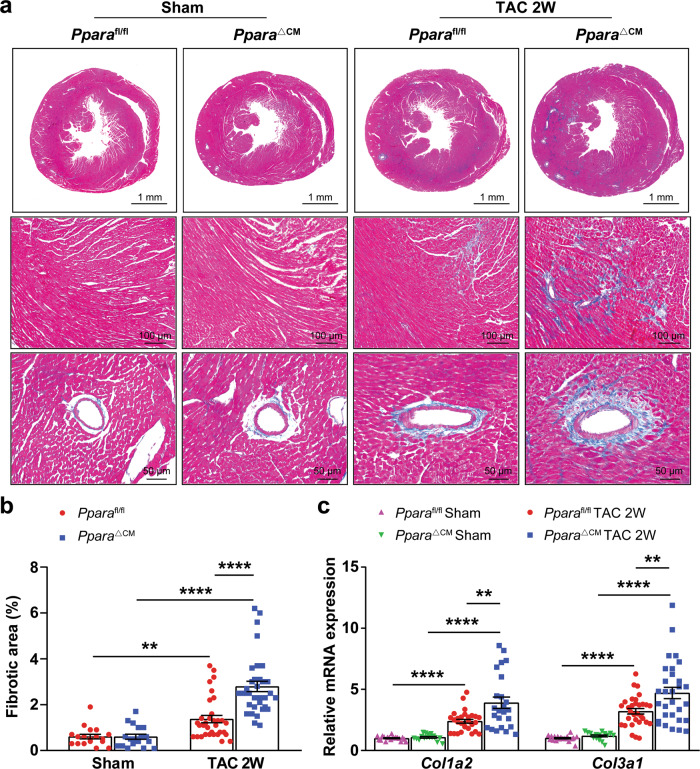

Fibrosis also contributes to cardiac remodeling and dysfunction. Masson’s trichrome staining revealed that the levels of both myocardial and interstitial fibrosis were markedly increased in the TAC-challenged PparaΔCM mice (Fig. 2a, b), consistent with upregulated mRNA levels of the fibrotic markers collagen type I (Col1a2) and collagen type III (Col3a1) (Fig. 2c). Taken together, these results indicate that cardiomyocyte PPARα disruption facilitates TAC-induced cardiac remodeling and contractile dysfunction.

Fig. 2. Cardiomyocyte PPARα deficiency aggravated TAC-induced cardiac fibrosis.

Pparafl/fl and PparaΔCM mice were subjected to TAC or sham surgery, and analyses were performed 2 weeks later. a Representative images of Masson’s trichrome staining of heart sections. b Quantification of the fibrotic area (n = 18–33). c Expression of the fibrosis-related genes collagen type I alpha2 (Col1a2) and collagen type III alpha1 (Col3a1) in mouse hearts was detected by qPCR (n = 16–31). The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001.

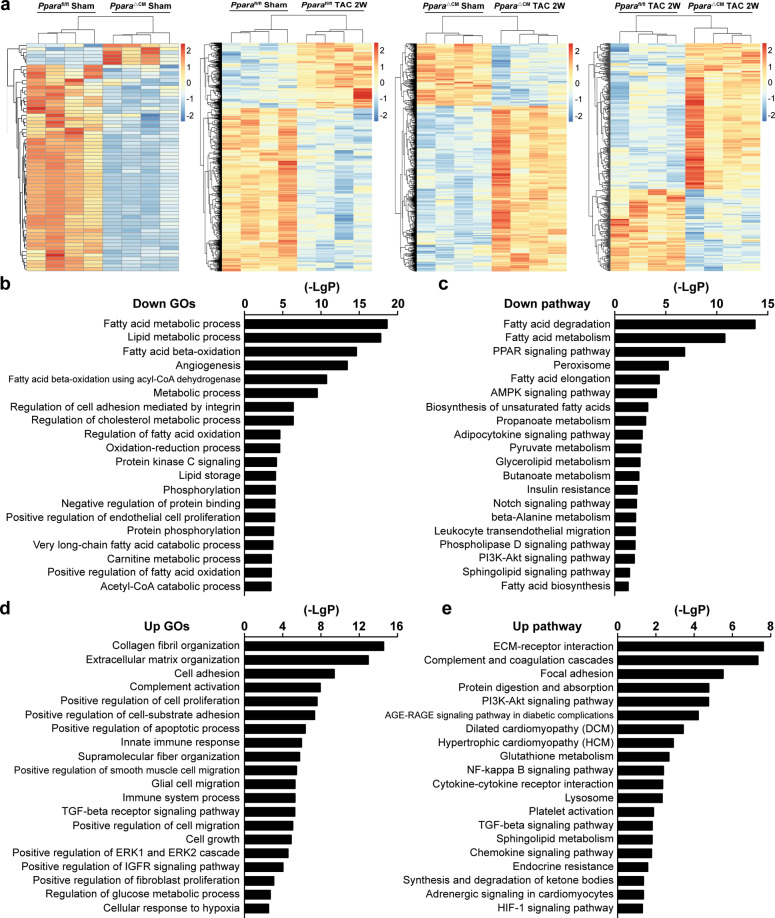

Cardiomyocyte PPARα deficiency contributed to the dysregulation of transcriptomes

To comprehensively understand the gene profiles controlled by cardiomyocyte PPARα in TAC-induced cardiac remodeling, transcriptome analysis was performed (the data are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus website under accession number GSE127954). Hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes in the heart showed that cardiomyocyte PPARα deficiency contributed to the dysregulation of transcriptome expression (Fig. 3a). GO analysis and KEGG analysis demonstrated that the FA metabolic process, lipid metabolic process, FA β-oxidation, FA degradation, and glycerolipid and sphingolipid metabolism were downregulated in the PparaΔCM hearts upon TAC (Fig. 3b, c). In contrast, GO and KEGG analyses revealed that the glucose metabolic process, hypoxia, and activation of the PI3K-Akt and HIF1 signaling pathways were increased in the hypertrophic PparaΔCM heart (Fig. 3d, e). Moreover, fibrosis-related events, such as collagen fibril organization, ECM organization, ECM-receptor interaction, and TGF-β signaling pathway activation, were markedly increased in the hypertrophic PparaΔCM hearts (Fig. 3d, e). All these results indicate that cardiomyocyte PPARα mediates energy metabolism and ECM homeostasis during TAC-induced cardiac remodeling.

Fig. 3. Transcriptome analyses of the mouse heart.

Pparafl/fl and PparaΔCM mice were subjected to TAC or sham surgery, and analyses were performed 2 weeks later. a Hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes in mouse hearts (n = 4). b, c Reduced enrichment of differentially expressed genes in hypertrophic PparaΔCM heart compared with hypertrophic Pparafl/fl hearts in Gene Ontology (GO) and pathway analyses. d, e Upregulated GO and pathway enrichment of differentially expressed genes in hypertrophic PparaΔCM hearts compared with that in hypertrophic Pparafl/fl hearts.

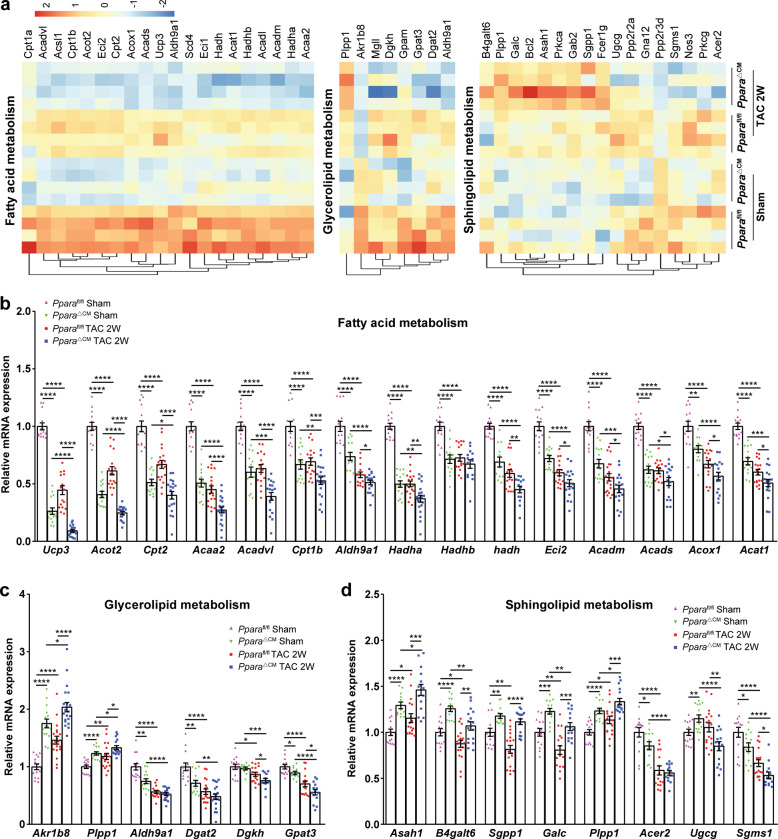

Cardiomyocyte PPARα is crucial for myocardial energy metabolism and homeostasis

Transcriptome bioinformatics analysis indicated that cardiomyocyte PPARα played a crucial role in regulating lipid metabolism-related gene events. Among these genes, FA metabolism-related genes, glycerolipid metabolism-related genes, and sphingolipid metabolism-related genes were profiled (Fig. 4a). The qPCR analysis revealed that the expression of FA metabolism-related genes (Cd36, Cpt1b, Cpt2, Acox1, Acaa2, Acadm, Acads, Acadvl, Hadh, Hadha, Hadhb, Acat1, Aldh9a1, Eci2, Ucp3, and Acot2) (Fig. 4b) was decreased in the hypertrophic PparaΔCM hearts. In addition, glycerolipid metabolism-related genes (Akr1b8, Plpp1, Aldh9a1, Dgat2, Dgkh, and Gpat3) (Fig. 4c) and sphingolipid metabolism-related genes (Asah1, B4galt6, Sgpp1, Galc, Plpp1, Acer2, Ugcg, and Sgms1) (Fig. 4d) were also dysregulated in the hypertrophic PparaΔCM hearts. These results demonstrate that cardiomyocyte PPARα deficiency leads to a decreased capacity for myocardial lipid metabolism, especially FA metabolism, during short-term TAC-induced cardiac remodeling.

Fig. 4. Lipid metabolism-related genes were differentially dysregulated in Ppara△CM hearts.

a Hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes in fatty acid metabolism, glycerolipid metabolism, and sphingolipid metabolism. b Expression of fatty acid metabolism-related genes in mouse hearts was verified by qPCR (n = 11–20). c Expression of glycerolipid metabolism-related genes in mouse hearts was verified by qPCR (n = 11–20). d Expression of sphingolipid metabolism-related genes in mouse hearts was verified by qPCR (n = 11–20). The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

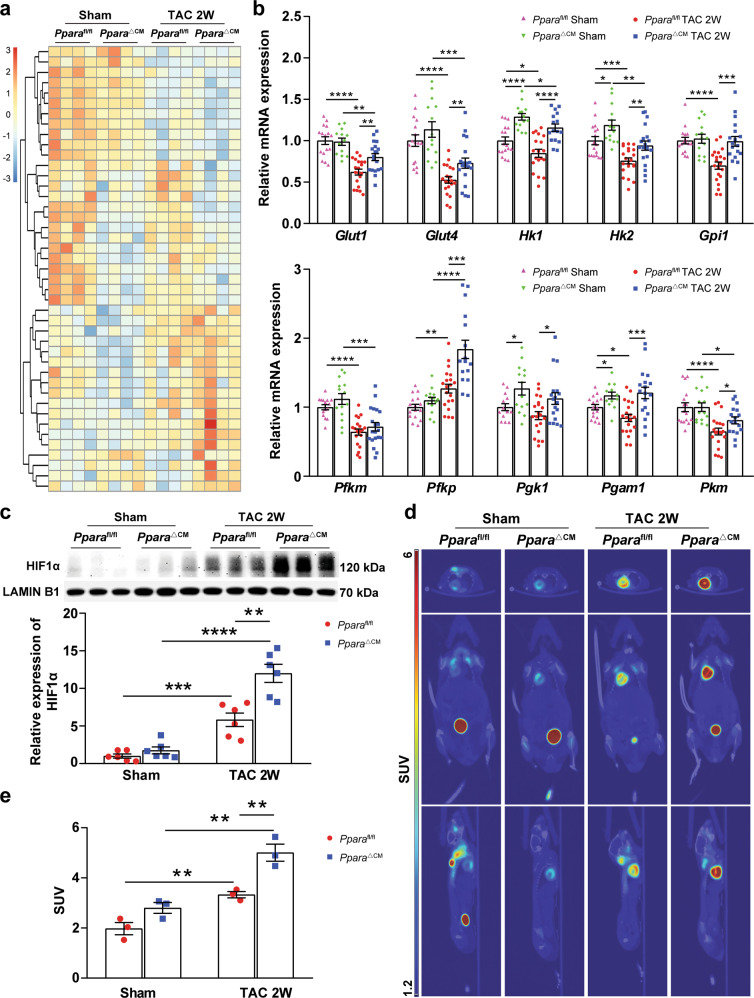

The transcriptome analysis also revealed that cardiomyocyte PPARα deficiency contributed to the upregulation of glucose metabolism-related gene events, and glycolysis-related genes were profiled (Fig. 5a). The expression of these genes, including Glut1, Glut4, Hk1, Hk2, Gpi1, Pfkm, Pfkp, Pgkl, Pgam1, and Pkm, was upregulated in the Ppara△CM hearts upon TAC (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, the expression of HIF1α, which regulates glycolysis in the heart, was also increased in the hypertrophic PparaΔCM hearts (Fig. 5c). As indicated by PET/CT, the uptake of glucose (18F-FDG) was also obviously increased in the TAC-challenged PparaΔCM hearts (Fig. 5d, e), which was favorable for myocardial energy compensatory generation. These results suggest that glucose metabolism is enhanced in PparaΔCM hearts.

Fig. 5. The expression of glycolysis-related genes was upregulated in PparaΔCM hearts.

Pparafl/fl and PparaΔCM mice were randomized to receive TAC or sham surgery, and analyses were performed 2 weeks later. a Gene profiles during glycolysis. b Expression of glycolysis-related genes in mouse hearts was detected by qPCR (n = 14–21). c Expression of HIF1α in nuclear extracts from Pparafl/fl and Ppara△CM hearts was detected by Western blot analysis. Quantification of HIF1α expression (bottom, n = 6). d Representative PET/CT images of mouse hearts. e Quantification of the standard uptake value (SUV) for the mouse hearts (n = 3). The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

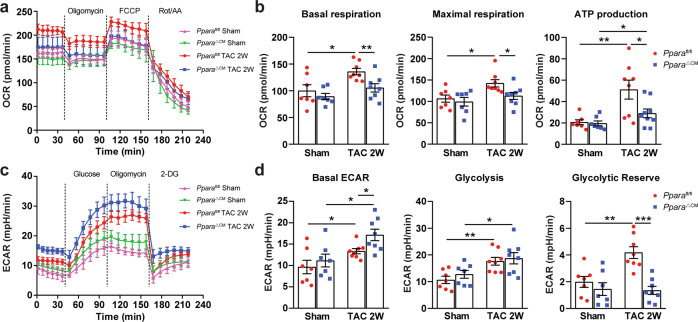

To assess whether the observed energy metabolism-related gene dysregulation was correlated with mitochondrial respiration function, metabolic flux analysis was performed, and the mitochondrial OCR and the ECAR were measured in Pparafl/fl and PparaΔCM heart slices using a Seahorse XFe24 analyzer. The results showed that 2 weeks of TAC significantly increased mitochondrial respiration (including basal OCR, maximal OCR and ATP production) in the Pparafl/fl hearts; however, this increase was markedly blunted in the PparaΔCM hearts (Fig. 6a, b). In contrast, the hypertrophic PparaΔCM hearts exhibited enhanced ECAR capacity, as reflected by increased basal ECAR and glycolysis but decreased glycolytic reserve (Fig. 6c, d). These results indicate that cardiomyocyte PPARα deficiency impairs mitochondrial respiratory function and energy metabolism.

Fig. 6. Cardiomyocyte PPARα deficiency impaired mitochondrial respiration function.

Pparafl/fl and PparaΔCM mice were randomized to receive TAC or sham surgery, and analyses were performed 2 weeks later. a The oxygen consumption rates (OCRs) in heart slices were measured under basal, oligomycin- (50 µM), FCCP- (20 µM), or rotenone/antimycin A-stimulated (20 µM) conditions at the indicated time points. b Quantification of the mitochondrial basal respiration rate, maximal respiration rate, and ATP production (n = 7–8). c Extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) in heart slices was measured under basal, glucose- (30 mM), oligomycin- (50 µM) or 2-DG-stimulated (50 mM) conditions at the indicated time points. d Quantification of the basal ECAR, glycolysis and glycolytic reserve (n = 7–8). The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

Cardiomyocyte PPARα deficiency exacerbated TAC-induced ECM remodeling

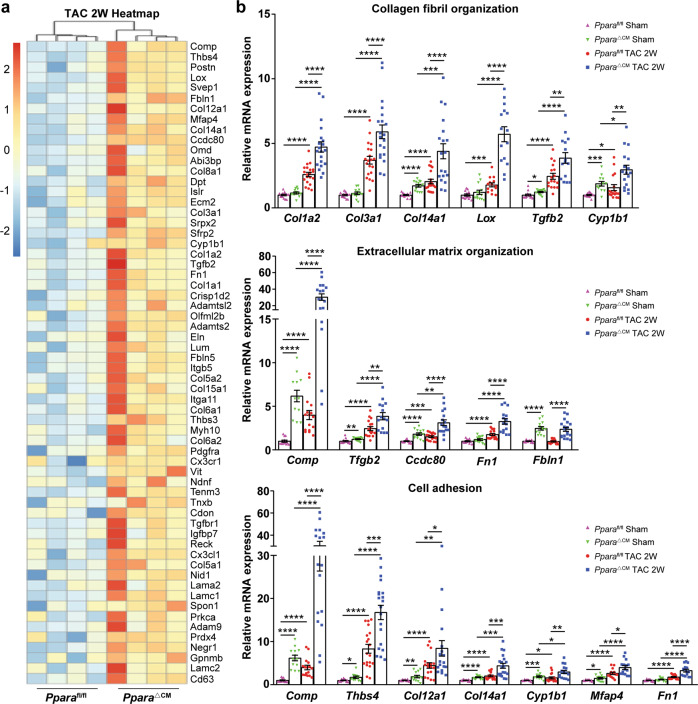

In addition to the regulation of myocardial energy metabolism, PPARα might also be involved in the regulation of ECM remodeling [26]. However, the ECM remodeling-related transcriptomic events critical for cardiomyocyte PPARα have not been identified. Gene profile analysis showed that ECM remodeling-related gene expression was greatly upregulated in the PparaΔCM hearts upon TAC, including collagen fibril organization-related genes Col1a2, Col3a1, Col14a1, Lox, Tgfb2, and Cyp1b1, ECM organization-related genes Comp, Tgfb2, Ccdc80, Fn1, and Fbln1, and cell adhesion-related genes Comp, Thbs4, Col12a1, Col14a1, Cyp1b1, Mfap4, and Fn1, which were differentially upregulated in the TAC-challenged PparaΔCM hearts (Fig. 7a). qPCR analyses validated the upregulation of these genes in the PparaΔCM hearts upon TAC (Fig. 7b). Collectively, these data suggest that cardiomyocyte PPARα inhibits TAC-induced ECM remodeling.

Fig. 7. The expression of cardiac fibrosis-related genes was upregulated in PparaΔCM hearts after TAC.

Pparafl/fl and PparaΔCM mice were randomized to receive TAC or sham surgery, and analyses were performed 2 weeks later. a Fibrosis-related genes profiles. b Expression of collagen fibril organization-, ECM organization-, and cell adhesion-related genes in mouse hearts was detected by qPCR (n = 13–20). The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

Discussion

PPARα plays an essential role in cardiac homeostasis; however, its precise role in pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling is unclear due to the lack of tissue-specific PPARα-knockout models [27, 28]. In this study, inducible cardiomyocyte-specific PPARα-deficient mice were developed for the first time and used to determine the role of cardiomyocyte PPARα in TAC-induced cardiac remodeling. PPARα deficiency in cardiomyocytes accelerated TAC-induced cardiac remodeling and contractile dysfunction. Transcriptome analysis identified impaired FAO but enhanced glucose metabolism and ECM remodeling in hypertrophic PparaΔCM hearts. PET/CT scanning for 18F-FDG uptake demonstrated an increased reliance on glucose utilization in PparaΔCM mice upon TAC. Moreover, bioenergetic analysis revealed impaired oxidative phosphorylation but increased glycolysis in PparaΔCM hearts. Taken together, these data indicate that cardiomyocyte PPARα is essential for maintaining normal energy metabolism and ECM homeostasis during pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling.

PPARα is a master regulator of cardiac metabolism and plays an important role in the maintenance of cardiac homeostasis [27, 28]. Several studies have suggested that PPARα is expressed at various levels in pathological cardiac remodeling and heart failure [8–12, 17]. However, the role of PPARα seemed controversial. Disruption and overexpression of PPARα in the mouse heart can lead to cardiac dysfunction and heart failure [15, 29]. In the current study, pathological cardiac remodeling was dramatically aggravated in the cardiomyocyte-specific PPARα-deficient hearts during short-term TAC-induced cardiac remodeling. This result was consistent with a report indicating that cardiac hypertrophy was enhanced in PPARα-whole-body-knockout mice [13].

Energy metabolism is critical for cardiac homeostasis. Impaired FAO accelerates the development of pathological cardiac remodeling and heart failure [3–5]. PPARα is a master regulator of FAO and belongs to the nuclear receptor superfamily [27]. In this study, transcriptome analysis demonstrated that the aspects of FAO, such as the FA metabolic process, FA β-oxidation, and FA degradation, were diminished in cardiomyocyte-specific PPARα-deficient hearts during TAC-induced cardiac remodeling. In contrast, glycolysis-related processes were enhanced in hypertrophic PparaΔCM hearts, which was mainly attributed to increased HIF1α protein level. This finding supports that of previous studies showing that energy sources are primarily switched from FAs to glucose because of high HIF activity in pathological cardiac remodeling [30–34]. However, further investigations are still needed to explore how the interaction between PPARα and HIF1α is coordinated during TAC-induced cardiac remodeling and heart failure.

Cardiac fibrosis and inflammation contribute to cardiac remodeling [1, 2]. Previous studies have shown that PPARα activation by fibrates or Wy-14643 can attenuate TAC-induced cardiac fibrosis and inflammation in rodents [13, 16, 35–41]. In this study, cardiomyocyte PPARα deficiency aggravated TAC-induced cardiac fibrosis and inflammation and augmented the mRNA levels of numerous genes involved in ECM remodeling. Although the occupation of the cardiomyocyte genome by PPARα remains to be further investigated, the mechanisms by which PPARα suppresses genes might be attributed to the “trans-repression” activity of PPARα [42–44]. Another possibility suggests that lncRNAs or miRNAs may be involved in the process by which cardiomyocyte PPARα inhibits cardiac fibrosis [45], which needs further investigation.

In summary, cardiomyocyte PPARα is crucial for cardiac homeostasis because it regulates myocardial energy metabolism and ECM remodeling during TAC-induced cardiac remodeling. This study suggests that cardiomyocyte PPARα may serve as a potential therapeutic target to inhibit cardiac remodeling.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82070474, 81670400, and 91739120), the Key Science and Technology Project of Beijing Municipal Institutions (KZ202010025032), Supportive Project of High-Level Teachers in Beijing Municipal Universities in the Period of 13th Five-Year Plan (CIT&TCD20190332) to Aijuan Qu. Xia Wang was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81800233), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2017M620830), and the Beijing Postdoctoral Research Foundation (2018-22-113).

Author contributions

XW designed the study, performed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. XXZ, SYJ, DQ, BQY, GMX, YL, and YTS performed the experiments and analyzed the data. QX participated in the echocardiography. JD and XMW participated in the initial elaboration of the project. QBX and FJG designed the experimental plan, and supervised the study. AJQ conceived and supervised the study, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and edited the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41401-021-00743-z.

References

- 1.Nakamura M, Sadoshima J. Mechanisms of physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15:387–407. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0007-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu QQ, Xiao Y, Yuan Y, Ma ZG, Liao HH, Liu C, et al. Mechanisms contributing to cardiac remodelling. Clin Sci (Lond) 2017;131:2319–45. doi: 10.1042/CS20171167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertero E, Maack C. Metabolic remodelling in heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15:457–70. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warren JS, Oka SI, Zablocki D, Sadoshima J. Metabolic reprogramming via PPARalpha signaling in cardiac hypertrophy and failure: From metabolomics to epigenetics. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;313:H584–96. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00103.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibb AA, Hill BG. Metabolic coordination of physiological and pathological cardiac remodeling. Circ Res. 2018;123:107–28. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.312017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huss JM, Kelly DP. Nuclear receptor signaling and cardiac energetics. Circ Res. 2004;95:568–78. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000141774.29937.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson E, Grieve DJ. Significance of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in the cardiovascular system in health and disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;122:246–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barger PM, Brandt JM, Leone TC, Weinheimer CJ, Kelly DP. Deactivation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha during cardiac hypertrophic growth. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1723–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI9056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bugger H, Schwarzer M, Chen D, Schrepper A, Amorim PA, Schoepe M, et al. Proteomic remodelling of mitochondrial oxidative pathways in pressure overload-induced heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:376–84. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanda H, Nohara R, Hasegawa K, Kishimoto C, Sasayama S. A nuclear complex containing PPARalpha/RXRalpha is markedly downregulated in the hypertrophied rat left ventricular myocardium with normal systolic function. Heart Vessels. 2000;15:191–6. doi: 10.1007/s003800070022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oka S, Alcendor R, Zhai P, Park JY, Shao D, Cho J, et al. PPARalpha-Sirt1 complex mediates cardiac hypertrophy and failure through suppression of the ERR transcriptional pathway. Cell Metab. 2011;14:598–611. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osorio JC, Stanley WC, Linke A, Castellari M, Diep QN, Panchal AR, et al. Impaired myocardial fatty acid oxidation and reduced protein expression of retinoid X receptor-alpha in pacing-induced heart failure. Circulation. 2002;106:606–12. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000023531.22727.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smeets PJ, Teunissen BE, Willemsen PH, van Nieuwenhoven FA, Brouns AE, Janssen BJ, et al. Cardiac hypertrophy is enhanced in PPAR alpha-/- mice in response to chronic pressure overload. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;78:79–89. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loichot C, Jesel L, Tesse A, Tabernero A, Schoonjans K, Roul G, et al. Deletion of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha induces an alteration of cardiac functions. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H161–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01065.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finck BN, Lehman JJ, Leone TC, Welch MJ, Bennett MJ, Kovacs A, et al. The cardiac phenotype induced by PPARalpha overexpression mimics that caused by diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:121–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI0214080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaimoto S, Hoshino A, Ariyoshi M, Okawa Y, Tateishi S, Ono K, et al. Activation of PPAR-alpha in the early stage of heart failure maintained myocardial function and energetics in pressure-overload heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;312:H305–13. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00553.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young ME, Laws FA, Goodwin GW, Taegtmeyer H. Reactivation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha is associated with contractile dysfunction in hypertrophied rat heart. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44390–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103826200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brocker CN, Yue J, Kim D, Qu A, Bonzo JA, Gonzalez FJ. Hepatocyte-specific PPARα expression exclusively promotes agonist-induced cell proliferation without influence from nonparenchymal cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2017;312:G283–99. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00205.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sohal DS, Nghiem M, Crackower MA, Witt SA, Kimball TR, Tymitz KM, et al. Temporally regulated and tissue-specific gene manipulations in the adult and embryonic heart using a tamoxifen-inducible Cre protein. Circ Res. 2001;89:20–25. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.092687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaw AM, Williams CM, Law HK, Chow BK. Minimally invasive transverse aortic constriction in mice. J Vis Exp. 2017; 2017: e55293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Wang X, Wang HX, Li YL, Zhang CC, Zhou CY, Wang L, et al. MicroRNA Let-7i negatively regulates cardiac inflammation and fibrosis. Hypertension. 2015;66:776–85. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Z, Gupte AA, Zhang A, Hamilton DJ. Pet imaging and its application in cardiovascular diseases. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2017;13:29–33. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-13-1-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ou Q, Jacobson Z, Abouleisa RRE, Tang XL, Hindi SM, Kumar A, et al. Physiological biomimetic culture system for pig and human heart slices. Circ Res. 2019;125:628–42. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.314996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai Y, Liu H, Song E, Wang L, Xu J, He Y, et al. Deficiency of telomere-associated repressor activator protein 1 precipitates cardiac aging in mice via p53/PPARalpha signaling. Theranostics. 2021;11:4710–27. doi: 10.7150/thno.51739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peoples JNR, Maxmillian T, Le Q, Nadtochiy SM, Brookes PS, Porter GA, et al. Metabolomics reveals critical adrenergic regulatory checkpoints in glycolysis and pentose-phosphate pathways in embryonic heart. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:6925–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujita K, Maeda N, Sonoda M, Ohashi K, Hibuse T, Nishizawa H, et al. Adiponectin protects against angiotensin II-induced cardiac fibrosis through activation of PPAR-alpha. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:863–70. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.156687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montaigne D, Butruille L, Staels B. PPAR control of metabolism and cardiovascular functions. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021. 10.1038/s41569-021-00569-6 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Liao HH, Jia XH, Liu HJ, Yang Z, Tang QZ. The role of PPARs in pathological cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Curr Pharm Des. 2017;23:1677–86. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666160928150040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watanabe K, Fujii H, Takahashi T, Kodama M, Aizawa Y, Ohta Y, et al. Constitutive regulation of cardiac fatty acid metabolism through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha associated with age-dependent cardiac toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22293–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ritterhoff J, Young S, Villet O, Shao D, Neto FC, Bettcher LF, et al. Metabolic remodeling promotes cardiac hypertrophy by directing glucose to aspartate biosynthesis. Circ Res. 2020;126:182–96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.315483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mirtschink P, Krek W. Hypoxia-driven glycolytic and fructolytic metabolic programs: pivotal to hypertrophic heart disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863:1822–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taegtmeyer H. Switching metabolic genes to build a better heart. Circulation. 2002;106:2043–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000036760.42319.3F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lehman JJ, Kelly DP. Transcriptional activation of energy metabolic switches in the developing and hypertrophied heart. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2002;29:339–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lopaschuk GD, Collins-Nakai RL, Itoi T. Developmental changes in energy substrate use by the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 1992;26:1172–80. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.12.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu SC, Ma ZG, Wei WY, Yuan YP, Tang QZ. Bezafibrate attenuates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. PPAR Res. 2017;2017:5789714. doi: 10.1155/2017/5789714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zou J, Le K, Xu S, Chen J, Liu Z, Chao X, et al. Fenofibrate ameliorates cardiac hypertrophy by activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha partly via preventing p65-NFkappaB binding to NFATc4. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;370:103–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smeets PJ, Teunissen BE, Planavila A, de Vogel-van den Bosch H, Willemsen PH, van der Vusse GJ, et al. Inflammatory pathways are activated during cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and attenuated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors PPARalpha and PPARdelta. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29109–18. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802143200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duhaney TA, Cui L, Rude MK, Lebrasseur NK, Ngoy S, De Silva DS, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha-independent actions of fenofibrate exacerbates left ventricular dilation and fibrosis in chronic pressure overload. Hypertension. 2007;49:1084–94. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.086926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Irukayama-Tomobe Y, Miyauchi T, Sakai S, Kasuya Y, Ogata T, Takanashi M, et al. Endothelin-1-induced cardiac hypertrophy is inhibited by activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha partly via blockade of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase pathway. Circulation. 2004;109:904–10. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000112596.06954.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diep QN, Benkirane K, Amiri F, Cohn JS, Endemann D, Schiffrin EL. PPAR alpha activator fenofibrate inhibits myocardial inflammation and fibrosis in angiotensin II-infused rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;36:295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iglarz M, Touyz RM, Viel EC, Paradis P, Amiri F, Diep QN, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha and receptor-gamma activators prevent cardiac fibrosis in mineralocorticoid-dependent hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:737–43. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000083511.91817.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barlaka E, Galatou E, Mellidis K, Ravingerova T, Lazou A. Role of pleiotropic properties of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in the heart: focus on the nonmetabolic effects in cardiac protection. Cardiovasc Ther. 2016;34:37–48. doi: 10.1111/1755-5922.12166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Delerive P, De Bosscher K, Besnard S, Vanden Berghe W, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha negatively regulates the vascular inflammatory gene response by negative cross-talk with transcription factors NF-kappaB and AP-1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32048–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen L, Li L, Chen J, Li L, Zheng Z, Ren J, et al. Oleoylethanolamide, an endogenous PPAR-alpha ligand, attenuates liver fibrosis targeting hepatic stellate cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:42530–40. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chuppa S, Liang M, Liu P, Liu Y, Casati MC, Cowley AW, et al. MicroRNA-21 regulates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha, a molecular mechanism of cardiac pathology in Cardiorenal Syndrome Type 4. Kidney Int. 2018;93:375–89. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.