Abstract

The transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), a ligand-gated nonselective cation channel, is well known for mediating heat and pain sensation in the periphery. Increasing evidence suggests that TRPV1 is also expressed at various central synapses, where it plays a role in different types of activity-dependent synaptic changes. Although its precise localizations remain a matter of debate, TRPV1 has been shown to modulate both neurotransmitter release at presynaptic terminals and synaptic efficacy in postsynaptic compartments. In addition to being required in these forms of synaptic plasticity, TRPV1 can also modify the inducibility of other types of plasticity. Here, we highlight current evidence of the potential roles for TRPV1 in regulating synaptic function in various brain regions, with an emphasis on principal mechanisms underlying TRPV1-mediated synaptic plasticity and metaplasticity. Finally, we discuss the putative contributions of TRPV1 in diverse brain disorders in order to expedite the development of next-generation therapeutic treatments.

Keywords: vanilloid receptor, endocannabinoids, synaptic function, brain, neurotransmision

Introduction

TRPV1 is a nonselective ligand-gated cation channel predominantly expressed in peripheral endings of small diameter nociceptive primary afferent neurons, where its activation is associated with nociception and pain sensation including thermal hyperalgesia (Caterina et al., 2000; Davis et al., 2000; Brederson et al., 2013). This homotetrameric receptor can be activated by a wide range of stimuli, including heat, changes in pH, exogenous compounds such as capsaicin (Caterina et al., 1997) and endogenous lipid ligands including endovanilloids/endocannabinoids such as anandamide (AEA) (Ross, 2003; Toth et al., 2009). Also, TRPV1 channels are located on the central endings of nociceptive neurons in the spinal cord that make synaptic contact with second order neurons (Caterina et al., 1997; Hwang et al., 2004). Pharmacological activation of presynaptic TRPV1 channels modulates glutamatergic transmission by increasing the frequency of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) and by inhibiting evoked EPSCs (Tognetto et al., 2001; Baccei et al., 2003; Medvedeva et al., 2008).

Although first identified and cloned in peripheral afferent fibers (Caterina et al., 1997), accumulating evidence using diverse experimental approaches indicates that TRPV1 is also expressed in different brain regions including prefrontal cortex, amygdala, brainstem, hypothalamus, cerebellum and the hippocampal formation (Sasamura et al., 1998; Mezey et al., 2000; Sanchez et al., 2001; Roberts et al., 2004; Toth et al., 2005; Cristino et al., 2006; Starowicz et al., 2008; Kauer and Gibson, 2009; Huang et al., 2014; Kumar et al., 2018). While brain TRPV1 is seemingly expressed at lower levels than the peripheral counterparts (Cavanaugh et al., 2011), its activation has been linked to different forms of synaptic plasticity and metaplasticity. Moreover, TRPV1 likely modulates anxiety, fear and panic responses in vivo (Almeida-Santos et al., 2013; Aguiar et al., 2014; Terzian et al., 2014) and also the severity of neurological and cognitive disorders, including epilepsy, depression and Alzheimer’s Disease (Chen et al., 2017; Balleza-Tapia et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019, 2020a; Du et al., 2020). However, the mechanisms by which brain TRPV1 regulates synaptic function and behavior remains far from being completely understood.

Presynaptic Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 Channels in the Brain

Capsaicin, the pungent ingredient in hot chili peppers, acts as an exogenous TRPV1 agonist, and it has been shown to enhance transmitter release in the spinal cord (Gamse et al., 1979; Baccei et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2009), supporting the presence of TRPV1 on presynaptic nerve terminals (Tominaga et al., 1998; Cortright et al., 2007). Consistent with this idea, TRPV1 has also been reported at excitatory presynaptic terminals in various brain regions, including the striatum, substantia nigra, hypothalamus, hippocampus, dorsolateral periaqueductal gray and medial prefrontal cortex (Karlsson et al., 2005; Xing and Li, 2007; Musella et al., 2009; Anstotz et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020). In these regions, its pharmacological activation facilitated spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) frequency but not amplitude, consistent with a presynaptic site of action. In the hypothalamus, hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, TRPV1 activation also increased the frequency of spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs; Banke, 2016). These results support a presynaptic localization of TRPV1 channels in glutamatergic and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) ergic nerve terminals, whose activation presumably increases intracellular calcium, resulting in enhanced synaptic transmission.

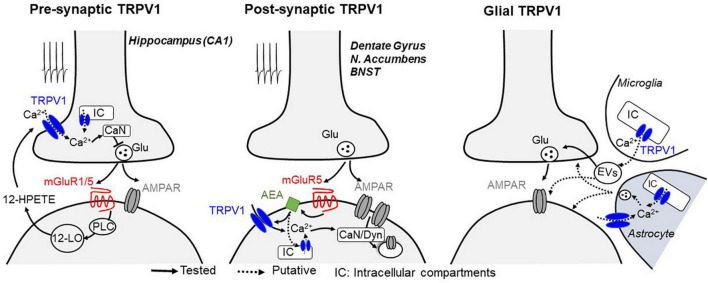

Although seemingly contradictory, TRPV1 activation has also been shown to reduce the release of GABA and glutamate (Gibson et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2020). In the hippocampus, TRPV1 mediates a form of long-term depression (LTD) at excitatory inputs onto GABAergic interneurons in the CA1 area of the hippocampus (Gibson et al., 2008). Such synaptic plasticity is dependent on presynaptic TRPV1 that are activated by the postsynaptically produced arachidonic acid metabolite 12-HPETE. At the presynaptic site, TRPV1 opening likely permeates calcium and subsequent activation of calcium-sensitive pathways to persistently depress transmitter release (Jensen and Edwards, 2012; Figure 1). It is noteworthy that a similar form of presynaptic LTD, involving a TRPV-like channel, has also been described in invertebrates (Yuan and Burrell, 2010, 2013), suggesting evolutionary conservation of this synaptic regulatory mechanism.

FIGURE 1.

Mechanisms described for TRPV1-mediated plasticity at central synapses. Glutamate release during synaptic stimulation activates Gq-coupled mGluRs, leading to the activation of phospholipase C (PLC) and downstream calcium-regulated enzymes, which likely triggers the biosynthesis of lipids including 12-HPETE (presynaptic TRPV1-LTD, left) or AEA (postsynaptic TRPV1-LTD, middle), two endocannabinoid/endovanilloid known to activate TRPV1 receptors. At presynaptic terminals, activation of TRPV1 on plasma membrane or intracellular compartments (IC) leads to a calcium (Ca2+)-dependent long-term depression of synaptic vesicle release, whereas when located at postsynaptic compartments, TRPV1 activation promotes a long-lasting, clathrin- and dynamin (Dyn)-dependent endocytosis of AMPA receptors. Notably, stimulation of calcium-sensitive phosphatase calcineurin (CaN) resulting from TRPV1 activation is likely to be a common mechanism to promote both pre and postsynaptic long-term changes of synaptic efficacy. TRPV1 channels are also expressed in glial cells (right), where its activation can modulate synaptic efficacy presumably through the production and release of inflammatory mediators through microglia-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) or by Ca2+-dependent release of gliotransmitters from astrocytes.

Postsynaptic Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 Channels in the Brain

TRPV1 also mediates postsynaptic forms of LTD (Chavez et al., 2010; Grueter et al., 2010; Puente et al., 2011), strongly suggesting that these channels are also present postsynaptically. In the dentate gyrus and nucleus accumbens, repetitive stimulation of glutamatergic afferents triggers TRPV1-mediated LTD of excitatory synaptic efficacy through a mechanism that involves metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) signaling and clathrin-dependent endocytosis of the α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionate-type glutamate receptors (AMPARs; Chavez et al., 2010; Grueter et al., 2010). In the nucleus accumbens, mild pharmacological activation of muscarinic M1 receptors can also trigger persistent excitatory depression that requires TRPV1 (Neuhofer et al., 2018). It remains to be determined whether M1 receptors can play a role in activity-dependent TRPV1-mediated LTD. Interestingly, in the extended amygdala, TRPV1-mediated LTD selectively required mGluR5 but not mGluR1 (Puente et al., 2011), suggesting that not all G-protein coupled receptors can equally activate TRPV1 at synapses. Notably, TRPV1 activation also induces clathrin-dependent internalization of type A GABA receptors (GABAARs), showing a preference for somatic over dendritic compartments of dentate granule cells (Chavez et al., 2014). Because TRPV1 may be expressed in distinct intracellular compartments (Gallego-Sandin et al., 2009; Dong et al., 2010; Samie and Xu, 2011), it is possible that this synapse-specificity of TRPV1-mediated suppression of inhibition arise from channel expression in specific subcellular domains. Moreover, it remains unclear how TRPV1 can be endogenously activated to modulate GABAergic synaptic plasticity.

Although diverse forms of TRPV1-mediated LTD can be induced in the hippocampus (Table 1, i.e., CA1 vs dentate gyrus), TRPV1 channels themselves may be acting in the same way (Figure 1). For instance, calcium influx may be triggered by activation of either pre- or postsynaptic TRPV1, resulting in the recruitment of calcium-sensitive enzymes such as calcineurin (also known as protein phosphatase 2B), the predominant calcium/calmodulin-dependent serine/threonine phosphatase that maintains the appropriate phosphorylation status of many ion channels present at presynaptic and postsynaptic sites (Huang et al., 2021). Indeed, several forms of pre and postsynaptic forms of TRPV1-mediated LTD require calcineurin (Gibson et al., 2008; Chavez et al., 2010; Grueter et al., 2010; Yuan and Burrell, 2010, 2013; Jensen and Edwards, 2012). Thus, it is possible that TRPV1 may initiate an important negative feedback via calcineurin in response to increased neuronal activity. Further investigations are required to determine whether calcineurin is the main actor in TRPV1-mediated LTD. The presence of multiple phosphorylation sites in TRPV1 implies possible regulatory actions by different kinases, including calcium calmodulin, protein kinase A and C (Rosenbaum et al., 2004; Rosenbaum and Simon, 2007) as well as Src kinase (Jin et al., 2004). Their contribution to TRPV1-mediated plasticity remains unclear.

TABLE 1.

TRPV1-mediated synaptic plasticity in the mammalian brain.

| Brain area | Synapse type | Synaptic plasticity | Induction protocol | Expression mechanism | Endogenous agonist | References |

| Hippocampus | Excitatory inputs to GABAergic interneurons | LTD | HFS | Presynaptic Ca2+ Calcineurin |

Endovanilloid 12-HPETE |

Gibson et al., 2008

Jensen and Edwards, 2012 |

| Dentate gyrus | medial perforant path to dentate granule cells excitatory inputs | LTD | 1Hz Paired Protocol | Postsynaptic Ca2+ Calcineurin AMPA receptor endocytosis |

Anandamide | Chavez et al., 2010 |

| Nucleus accumbens | Excitatory inputs to D2+ neurons | LTD | LFS | Postsynaptic AMPA receptor endocytosis |

Anandamide | Grueter et al., 2010 |

| Amygdala, stria terminalis | Excitatory inputs | LTD | LFS | Postsynaptic | Anandamide | Puente et al., 2011 |

| Superior colliculus | Excitatory inputs* | LTD | HFS | Presynaptic? | Endovanilloid 12-HPETE | Maione et al., 2009 |

LFS, low frequency stimulation; HFS, high frequency stimulation; LTD, long-term depression. *Transiently in juvenile but not in adult.

Glial Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 Channels in the Brain

Modulation of synaptic transmission could also be the result of activation of TRPV1 in glia (Figure 1). For instance, proinflammatory molecules such as the bioactive phospholipid lysophosphatidic acid has been shown to activate TRPV1 by directly binding to its C-terminal (Nieto-Posadas et al., 2011). While microglial TRPV1 is primarily localized in mitochondrial but not plasma membranes (Miyake et al., 2015), its activation indirectly enhances glutamatergic transmission in cortical neurons (Marrone et al., 2017), presumably through the production and release of inflammatory mediators (Miyake et al., 2015; Marrone et al., 2017; Kong et al., 2019). TRPV1 may also be expressed in astrocytes (Toth et al., 2005; Marinelli et al., 2007), although most of the recent evidence suggests that this is induced in response to brain injury. For example, TRPV1 activation in substantia nigral astrocytes produces the ciliary neurotrophic factor, which prevents the active degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in rat models of Parkinson’s disease (Nam et al., 2015). Hypoxic ischemia also reportedly triggers the expression of astrocytic TRPV1 and consequent release of pro-inflammatory cytokines from astrocytes to neighboring neurons in epileptogenesis (Wang et al., 2019). However, whether TRPV1 in astrocytes can modify synaptic function and plasticity in neurons under physiological conditions remains unclear. It is also important to note that capsaicin has been reported to exert direct effects on voltage-sensitive ion channels (Hagenacker et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2014; Pasierski and Szulczyk, 2020) and thus may modulate neurotransmitter release in a TRPV1-independent manner in cases where TRPV1 antagonists or knockouts were not assessed. For example, in the lateral amygdala (LA), capsaicin reportedly modifies LTD through activation of TRPM1 (Gebhardt et al., 2016). Last but not least, activation of postsynaptic TRPV1 may induce the production of calcium dependent retrograde signaling molecules to suppress neurotransmitter release (see below).

Interaction Between Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 and the Endocannabinoid System

Within the hippocampus, inhibition of TRPV1 dramatically reduces glutamatergic input to oriens-lacunosum-moleculare (OLM) interneurons (Hurtado-Zavala et al., 2017) and can block presynaptic LTD of excitatory synapses at inhibitory GABAergic interneurons but not pyramidal neurons (Gibson et al., 2008). Notably, this TRPV1-dependent presynaptic modulation of synaptic plasticity is similar in many ways to that reported for endocannabinoid (eCB)-mediated LTD that involves the activation of presynaptic type 1 cannabinoid (CB1) receptors (Castillo et al., 2012; Katona and Freund, 2012). For instance, in both forms of LTD, postsynaptic mGluRs are involved in promoting the production of a lipid messenger that then acts retrogradely to suppress transmitter release in a long-term manner. In postsynaptic TRPV1-LTD, mGluR activation promotes the production of anandamide (AEA), a major endocannabinoid (Chavez et al., 2010; Grueter et al., 2010; Puente et al., 2011). In this case, AEA likely acts directly on postsynaptic TRPV1 to induce endocytosis of AMPARs expressed on dendritic spines, reducing their number and consequently the long-term reduction in excitatory synaptic strength. Given the ability of eCBs like AEA to activate TRPV1, it has been suggested that TRPV1 may act as an ionotropic eCB receptor (De Petrocellis et al., 2017; Muller et al., 2018; Storozhuk and Zholos, 2018) with central neuromodulatory effects that either mimic or oppose those exerted by CB1 receptors.

The factors that determine whether eCBs act on TRPV1 or CB1 receptors to regulate synaptic transmission remain unclear. Interestingly, in the bed nucleus of stria terminalis, L-type calcium channel activation in dendrites leads to production and secretion of 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) that acts on presynaptic CB1 receptors in short-term depression, whereas AEA secretion following mGluR5 activation acts on postsynaptic TRPV1 in LTD (Puente et al., 2011). Additionally, other eCBs such as N-arachidonoyl-dopamine (Huang et al., 2002), can also activate both TRPV1 and CB1R, producing opposing actions on synaptic transmission (Marinelli et al., 2007). Moreover, it has been proposed that postsynaptic TRPV1 activation by AEA can regulate the magnitude of 2-AG-mediated tonic inhibition of perisomatic GABAergic transmission in CA1 pyramidal neurons (Lee et al., 2015), putatively through TRPV1-induced reduction of 2-AG levels (Maccarrone et al., 2008).

Spike-timing-dependent long-term potentiation (tLTP) in the striatum and neocortex, important for acquiring new associative memories, requires both TRPV1 and CB1 receptors (Cui et al., 2015, 2018). Notably, capsaicin activation of TRPV1 alone in the neocortex suppressed excitatory transmission (Cui et al., 2018). The mechanisms underlying TRPV1 and CB1 receptor co-dependency and their conversion from depressive to potentiating effects remain to be investigated. The signaling pathways downstream of TRPV1 and CB1 receptor activation may be dynamically inter-regulated. Indeed, the lack of TRPV1 reportedly modifies the expression and localization of different components of the eCB system, causing a shift from CB1 receptor-mediated LTD to LTP in the dentate gyrus (Egana-Huguet et al., 2021). While these results suggest an ability of eCBs to act through both CB1 and TRPV1 receptors, the factors that determine directionality of synaptic plasticity and functional consequences in behavior need to be determined.

Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 in Metaplasticity

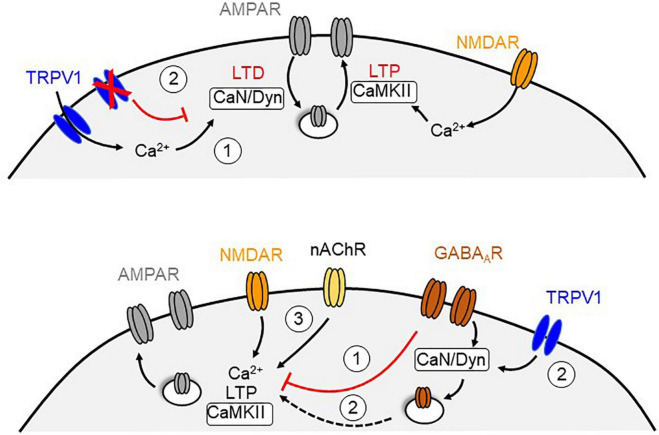

TRPV1 activity can alter the inducibility of long-term synaptic plasticity (Table 2). In the entorhinal cortex, LTP does not occur unless TRPV1 is blocked (Banke, 2016). Similarly, activation of TRPV1 with capsaicin attenuates the magnitude of LTP in the LA (Zschenderlein et al., 2011). Given the ability of TRPV1 activation to induce endocytosis of AMPARs, it is possible that the simultaneous expression of TRPV1-mediated LTD occludes or opposes LTP under these conditions (Figure 2, top). In contrast, TRPV1 knockout mice show deficits in LTP at the Schaffer collateral–commissural pathway to CA1 hippocampal neurons (Marsch et al., 2007), which can be rescued by activating OLM neurons with nicotine (Hurtado-Zavala et al., 2017). Moreover, these TRPV1 deficient mice reportedly show impaired hippocampal-dependent learning, fear conditioning and anxiety, effects that cannot be explained by alterations in nociception. Additionally, capsaicin exposure in wildtype mice enhances CA1 LTP and spatial memory (Li et al., 2008; Bennion et al., 2011), potentially by decreasing inhibition via TRPV1-mediated iLTD (Figure 2, bottom). Hippocampal TRPV1 activation also enables spatial memory retrieval under stressful conditions and rescues LTP in slices derived from swim-stressed mice (Kulisch and Albrecht, 2013). Although these findings support a role for brain TRPV1 in regulating synaptic function and behavior, it remains unclear how TRPV1 is able to bidirectionally modulate metaplasticity.

TABLE 2.

TRPV1 metaplasticity in the mammalian brain.

| Brain area | Synapse type | Effects | Induction protocol | References |

| Hippocampus | Schaffer collateral to CA1 Schaffer collateral to CA1 Schaffer collateral to CA1 |

Reduced LTP Enhanced LTP and reduced LTD Enhanced LTP |

HFS HFS-LFS TBS-HFS |

Marsch et al., 2007

Li et al., 2008 Bennion et al., 2011 |

| Entorhinal cortex | Excitatory Inputs to layer II/III |

TRPV1 blockade enables LTP | HFS | Banke, 2016 |

| Lateral amygdala | Cortical Excitatory inputs | Depressed LTP in ether Enhanced LTP in isoflurane Depressed LTP in ether Blocked stress-induced impairment of LTP |

HFS HFS |

Zschenderlein et al., 2011

Kulisch and Albrecht, 2013 |

| Dorsolateral striatum | Excitatory inputs | Co-dependent CB1-TRPV1 LTP | STDP | Cui et al., 2015 |

| Neocortex | Excitatory inputs | Co-dependent CB1-TRPV1 LTP | STDP | Cui et al., 2018 |

LFS, low frequency stimulation; HFS, high frequency stimulation; TBS, theta-burst stimulation; STDP, spike-timing dependent plasticity; LTP, long-term potentiation; LTD, long-term depression.

FIGURE 2.

Potential mechanisms for TRPV1-dependent metaplasticity at central synapses. Top, Calcium influx through TRPV1 channels triggers a form of postsynaptic LTD that require endocytosis of AMPARs, which may counterbalance the level of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) dependent LTP (1). In contrast, blockade or genetic deletion of TRPV1 channels recovers NMDAR-mediated LTP that may be due to the absence of TRPV1-LTD (2). Bottom, NMDAR-dependent LTP can be reduced by activation of GABAARs (1). Activation of TRPV1 channels could triggers a calcineurin (CaN) and dynamin (Dyn)-dependent endocytosis of GABAARs that remove the inhibitory suppression of the LTP (2). Exogenous activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) may oppose the influence of GABAergic inhibition and rescue LTP in the absence of TRPV1 likely by increasing calcium levels (3).

Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 Might Regulate Hippocampal Development/Circuit Maturation

In addition to regulating synaptic function, a role for TRPV1 in development is indicated by the ability of capsaicin to activate these channels in hippocampal Cajal-Retzius cells (Anstotz et al., 2018). These cells are a major source of the extracellular matrix protein reelin, which is essential for development (Del Rio et al., 1997; Frotscher, 1997). Indeed, Cajal-Retzius cells can powerfully excite GABAergic interneurons of the molecular layer in the dentate gyrus via TRPV1 activation (Anstotz et al., 2018), supporting the idea that TRPV1 may shape layer-specific interneuron connectivity in hippocampal development. Interestingly, the density of Cajal-Retzius cells decreases during postnatal development, raising that possibility that functional TRPV1 receptors may drive this progressive reduction by calcium-dependent apoptosis. Consistent with this idea, in the mouse hippocampus, it has been suggested that the expression of both the messenger (mRNA) and the protein are low in the early stages (<P15), increasing from the eighth postnatal week and then decreasing towards postnatal week 16 (Huang et al., 2014). Whether changes in the expression and activation of TRPV1 in early stages of development (P < 20) play a role in circuit maturation remain unclear. Notably, TRPV1 is transiently expressed in retinal afferents to principal neurons in the superior colliculus, where excitatory synapses onto them show a form of activity-dependent LTD that is dependent on TRPV1 in juvenile but not adult animals (Maione et al., 2009).

Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 in Mental Disorders and Neurological Diseases

TRPV1 has been linked to numerous neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders, with channel desensitization and blockade as primary therapeutic objectives (Edwards, 2014; Weng et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2019; Escelsior et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020b; Allain et al., 2021; Asth et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021; Akhilesh et al., 2022). Emerging evidence indicates that TRPV1 expression is increased following diverse forms of stress (Li et al., 2008; Rubino et al., 2008; Kulisch and Albrecht, 2013; Saffarzadeh et al., 2015; Garami et al., 2020; Aghazadeh et al., 2021) to likely drive maladaptive responses. For example, chronic exposition to heat can upregulate TRPV1 channels in the brain, probably by the generation of reactive oxygen species (Aghazadeh et al., 2021), but the functional effect of this expression in regulating neuronal function has not been studied. Interestingly, TRPV1 antagonists have been shown to induce hyperthermia in human clinical trials (Garami et al., 2020), suggesting that TRPV1 channels may play a role in regulating core body temperature. The central mechanisms are unknown but may involve TRPV1 channels in the hypothalamus (Iida et al., 2005; Sharif-Naeini et al., 2008; Sudbury and Bourque, 2013; Zaelzer et al., 2015; Molinas et al., 2019). Notably, TRPV1 blockers act through different mechanisms depending on animal model, specifically targeting proton-activated TRPV1 domains in rodents, but heat and proton-activated TRPV1 regions in humans (Garami et al., 2020). In neuropathic pain, nerve damage alters synaptic circuits in the spinal cord, brainstem and cortex, involving neurons and glial cells, that leads to persistent amplification of pain signals (Giordano et al., 2012; Tsuda et al., 2017; Arribas-Blazquez et al., 2019). It is unclear whether heightened TRPV1 function in these cell types contribute to such plasticity. However, in support of this idea, activation of microglial TRPV1 enhances glutamatergic neurotransmission and the presence of neuronal TRPV1 increases action potential firing, which could enhance cortical activity and be crucial for the emotional alteration in chronic pain (Marrone et al., 2017).

Moreover, TRPV1 may tonically modulate emotional defensive responses such as anxiety, fear and panic (Millan, 2003; Mcnaughton and Corr, 2004; Terzian et al., 2009; Canteras et al., 2010; Casarotto et al., 2012; Aguiar et al., 2015; Gobira et al., 2017). Stress conditioning is accompanied by augmented TRPV1 levels in both the hippocampus and LA (Kulisch and Albrecht, 2013; Navarria et al., 2014). Intracranial injection of TRPV1 antagonists or its genetic deletion in these limbic brain regions promotes anxiolytic and antidepressant states as well as decrease cue and contextual fear conditioning (Kasckow et al., 2004; Marsch et al., 2007; Rubino et al., 2008; Aguiar et al., 2009; Terzian et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2017). It has been proposed that blocking TRPV1 may be antidepressive by consequently increasing serotonin levels (Manna and Umathe, 2012). On the other hand, some reports indicate that activation of TRPV1 rescued stress-induced impairment of hippocampal LTP and spatial memory retrieval (Li et al., 2008). In contrast, activation of TRPV1 in control conditions suppresses LTP in LA by modulation of the nitric oxide system (Zschenderlein et al., 2011). More work is needed to understand how the blockade or deletion of TRPV1 promotes anxiolytic and anti-depressive states, while its overexpression rescues cognitive deficiencies caused by stress.

Interestingly, TRPV1 expression is reduced in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD; Du et al., 2020), which is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by memory and learning deficits. Disrupted TRPV1-mediated synaptic plasticity and metaplasticity may be involved, but this remains a matter of debate. For instance, TRPV1 activation or reinsertion prevents the shift in excitatory/inhibitory balance and restores normal brain oscillatory activity (Balleza-Tapia et al., 2018), rescues hippocampal LTP and improves memory performance (Chen et al., 2017; Du et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020a,2021). However, a recent report suggests that the absence of TRPV1 rescues memory deficits in AD (Kim et al., 2020). The diverse influences of TRPV1 channels in pathological condition may reflect cause or consequence of brain disorders. More time-lapse studies are needed to fully understand the exact contribution of TRPV1 in disease etiology and pathophysiology.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Accumulating evidence indicate that, in addition to its well-known role in modulating pain transduction, TRPV1 seems to play an important role in regulating brain synaptic transmission and plasticity. TRPV1 can be expressed both presynaptically and postsynaptically, and depending on the specific synapse, it can either increase or decrease neurotransmission. The impact of glial TRPV1 function on central synapses requires further investigation. Given the ubiquitous expression of TRPV1 throughout the brain, it is not surprising that TRPV1 has been implicated in several neurological and psychiatric disorders such as epilepsy, anxiety, and depression as well as drug-addiction disorders (Edwards, 2014; Singh et al., 2019; Escelsior et al., 2020; Allain et al., 2021; Asth et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021). Future work will expand our appreciation of the role and the exact mechanism underlying TRPV1-mediated changes in synaptic transmission and plasticity at central synapses in health and disease. For example, it is unknown whether TRPV1-mediated plasticity is present at GABAergic synapses and how it influences circuit function. It is also unclear under what conditions AEA acts on TRPV1 or CB1 receptors to modify synaptic function and behavior. Whether glial TRPV1 can be activated by AEA or other vanilloids is unclear as well. Moreover, different neuromodulators including serotonin, histamine, or prostaglandins are known to stimulate TRPV1 in the periphery (Cesare et al., 1999; Premkumar and Ahern, 2000; Vellani et al., 2001). Whether neuromodulation regulates brain function and behavior in a TRPV1-dependent manner remains unknown.

Author Contributions

AEC and CQC conceived of the general ideas presented in this review and supervised the work. CA-G and RM contributed equally to all sections and helped with figure and table construction. All authors made significant contributions to the information content and writing of this final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Funding

This work was supported by the Chilean government through FONDECYT Regular #1201848 (AEC), #1171840 (CQC), and by ANID Millennium Science Initiative Program (ACE210014 to CQC and AEC). RM was supported by a FONDECYT postdoc #3190793, and CA-G with Ph.D. fellowship from ANID.

References

- Aghazadeh A., Feizi M. A. H., Fanid L. M., Ghanbari M., Roshangar L. (2021). Effects of hyperthermia on TRPV1 and TRPV4 channels expression and oxidative markers in mouse brain. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 41 1453–1465. 10.1007/s10571-020-00909-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar D. C., Almeida-Santos A. F., Moreira F. A., Guimaraes F. S. (2015). Involvement of TRPV1 channels in the periaqueductal grey on the modulation of innate fear responses. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 27, 97–105. 10.1017/neu.2014.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar D. C., Moreira F. A., Terzian A. L., Fogaca M. V., Lisboa S. F., Wotjak C. T., et al. (2014). Modulation of defensive behavior by transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1 (TRPV1) channels. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 46 418–428. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar D. C., Terzian A. L., Guimaraes F. S., Moreira F. A. (2009). Anxiolytic-like effects induced by blockade of transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) channels in the medial prefrontal cortex of rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 205 217–225. 10.1007/s00213-009-1532-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhilesh, Uniyal A., Gadepalli A., Tiwari V., Allani M., Chouhan D., et al. (2022). Unlocking the potential of TRPV1 based siRNA therapeutics for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain. Life Sci. 288:120187. 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.120187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allain A. E., Aribo O., Medrano M. C., Fournier M. L., Bertrand S. S., Caille S. (2021). Impact of acute and chronic nicotine administration on midbrain dopaminergic neuron activity and related behaviours in TRPV1 knock-out juvenile mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 55 697–713. 10.1111/ejn.15577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida-Santos A. F., Moreira F. A., Guimaraes F. S., Aguiar D. C. (2013). Role of TRPV1 receptors on panic-like behaviors mediated by the dorsolateral periaqueductal gray in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 105 166–172. 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anstotz M., Lee S. K., Maccaferri G. (2018). Expression of TRPV1 channels by cajal-retzius cells and layer-specific modulation of synaptic transmission by capsaicin in the mouse hippocampus. J. Physiol. 596 3739–3758. 10.1113/JP275685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arribas-Blazquez M., Olivos-Ore L. A., Barahona M. V., Sanchez De La Muela M., Solar V., Jimenez E., et al. (2019). Overexpression of P2X3 and P2X7 receptors and TRPV1 channels in adrenomedullary chromaffin cells in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:155. 10.3390/ijms20010155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asth L., Iglesias L. P., De Oliveira A. C., Moraes M. F. D., Moreira F. A. (2021). Exploiting cannabinoid and vanilloid mechanisms for epilepsy treatment. Epilepsy Behav. 121:106832. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.106832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccei M. L., Bardoni R., Fitzgerald M. (2003). Development of nociceptive synaptic inputs to the neonatal rat dorsal horn: glutamate release by capsaicin and menthol. J. Physiol. 549 231–242. 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.040451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balleza-Tapia H., Crux S., Andrade-Talavera Y., Dolz-Gaiton P., Papadia D., Chen G., et al. (2018). TrpV1 receptor activation rescues neuronal function and network gamma oscillations from abeta-induced impairment in mouse hippocampus in vitro. Elife 7:e37703. 10.7554/eLife.37703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banke T. G. (2016). Inhibition of TRPV1 channels enables long-term potentiation in the entorhinal cortex. Pflugers Arch. 468 717–726. 10.1007/s00424-015-1775-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennion D., Jensen T., Walther C., Hamblin J., Wallmann A., Couch J., et al. (2011). Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 agonists modulate hippocampal CA1 LTP via the GABAergic system. Neuropharmacology 61 730–738. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brederson J. D., Kym P. R., Szallasi A. (2013). Targeting TRP channels for pain relief. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 716 61–76. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canteras N. S., Resstel L. B., Bertoglio L. J., Carobrez Ade P., Guimaraes F. S. (2010). Neuroanatomy of anxiety. Curr. Top Behav. Neurosci. 2, 77–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casarotto P. C., Terzian A. L., Aguiar D. C., Zangrossi H., Guimaraes F. S., Wotjak C. T., et al. (2012). Opposing roles for cannabinoid receptor type-1 (CB(1)) and transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1 channel (TRPV1) on the modulation of panic-like responses in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 37, 478–486. 10.1038/npp.2011.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo P. E., Younts T. J., Chavez A. E., Hashimotodani Y. (2012). Endocannabinoid signaling and synaptic function. Neuron 76 70–81. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina M. J., Leffler A., Malmberg A. B., Martin W. J., Trafton J., Petersen-Zeitz K. R., et al. (2000). Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science 288 306–313. 10.1126/science.288.5464.306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina M. J., Schumacher M. A., Tominaga M., Rosen T. A., Levine J. D., Julius D. (1997). The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature 389 816–824. 10.1038/39807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh D. J., Chesler A. T., Jackson A. C., Sigal Y. M., Yamanaka H., Grant R., et al. (2011). Trpv1 reporter mice reveal highly restricted brain distribution and functional expression in arteriolar smooth muscle cells. J. Neurosci. 31 5067–5077. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6451-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesare P., Moriondo A., Vellani V., Mcnaughton P. A. (1999). Ion channels gated by heat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 7658–7663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez A. E., Chiu C. Q., Castillo P. E. (2010). TRPV1 activation by endogenous anandamide triggers postsynaptic long-term depression in dentate gyrus. Nat. Neurosci. 13 1511–1518. 10.1038/nn.2684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez A. E., Hernandez V. M., Rodenas-Ruano A., Chan C. S., Castillo P. E. (2014). Compartment-specific modulation of GABAergic synaptic transmission by TRPV1 channels in the dentate gyrus. J. Neurosci. 34 16621–16629. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3635-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Huang Z., Du Y., Fu M., Han H., Wang Y., et al. (2017). Capsaicin attenuates amyloid-beta-induced synapse loss and cognitive impairments in mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. 59 683–694. 10.3233/JAD-170337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortright D. N., Krause J. E., Broom D. C. (2007). TRP channels and pain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1772 978–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristino L., De Petrocellis L., Pryce G., Baker D., Guglielmotti V., Di Marzo V. (2006). Immunohistochemical localization of cannabinoid type 1 and vanilloid transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 receptors in the mouse brain. Neuroscience 139 1405–1415. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., Paille V., Xu H., Genet S., Delord B., Fino E., et al. (2015). Endocannabinoids mediate bidirectional striatal spike-timing-dependent plasticity. J. Physiol. 593 2833–2849. 10.1113/JP270324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., Perez S., Venance L. (2018). Endocannabinoid-LTP mediated by CB1 and TRPV1 receptors encodes for limited occurrences of coincident activity in neocortex. Front. Cell Neurosci. 12:182. 10.3389/fncel.2018.00182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J. B., Gray J., Gunthorpe M. J., Hatcher J. P., Davey P. T., Overend P., et al. (2000). Vanilloid receptor-1 is essential for inflammatory thermal hyperalgesia. Nature 405 183–187. 10.1038/35012076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Petrocellis L., Nabissi M., Santoni G., Ligresti A. (2017). Actions and regulation of ionotropic cannabinoid receptors. Adv. Pharmacol. 80 249–289. 10.1016/bs.apha.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rio J. A., Heimrich B., Borrell V., Forster E., Drakew A., Alcantara S., et al. (1997). A role for cajal-retzius cells and reelin in the development of hippocampal connections. Nature 385 70–74. 10.1038/385070a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X. P., Wang X., Xu H. (2010). TRP channels of intracellular membranes. J. Neurochem. 113 313–328. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06626.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y., Fu M., Huang Z., Tian X., Li J., Pang Y., et al. (2020). TRPV1 activation alleviates cognitive and synaptic plasticity impairments through inhibiting AMPAR endocytosis in APP23/PS45 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Cell 19 e13113. 10.1111/acel.13113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J. G. (2014). TRPV1 in the central nervous system: synaptic plasticity, function, and pharmacological implications. Prog. Drug Res. 68 77–104. 10.1007/978-3-0348-0828-6_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egana-Huguet J., Saumell-Esnaola M., Achicallende S., Soria-Gomez E., Bonilla-Del Rio I. (2021). Lack of the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 shifts cannabinoid-dependent excitatory synaptic plasticity in the dentate gyrus of the mouse brain hippocampus. Front. Neuroanat 15:701573. 10.3389/fnana.2021.701573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escelsior A., Sterlini B., Belvederi Murri M., Valente P., Amerio A., Di Brozolo M. R., et al. (2020). Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 antagonism in neuroinflammation, neuroprotection and epigenetic regulation: potential therapeutic implications for severe psychiatric disorders treatment. Psychiatr Genet 30 39–48. 10.1097/YPG.0000000000000249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frotscher M. (1997). Dual role of cajal-retzius cells and reelin in cortical development. Cell Tissue Res. 290 315–322. 10.1007/s004410050936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Sandin S., Rodriguez-Garcia A., Alonso M. T., Garcia-Sancho J. (2009). The endoplasmic reticulum of dorsal root ganglion neurons contains functional TRPV1 channels. J. Biol. Chem. 284 32591–32601. 10.1074/jbc.M109.019687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamse R., Molnar A., Lembeck F. (1979). Substance P release from spinal cord slices by capsaicin. Life Sci. 25 629–636. 10.1016/0024-3205(79)90558-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garami A., Shimansky Y. P., Rumbus Z., Vizin R. C. L., Farkas N., Hegyi J., et al. (2020). Hyperthermia induced by transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV1) antagonists in human clinical trials: insights from mathematical modeling and meta-analysis. Pharmacol. Ther. 208:107474. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt C., Von Bohlen Und Halbach O., Hadler M. D., Harteneck C., Albrecht D. (2016). A novel form of capsaicin-modified amygdala LTD mediated by TRPM1. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 136 1–12. 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson H. E., Edwards J. G., Page R. S., Van Hook M. J., Kauer J. A. (2008). TRPV1 channels mediate long-term depression at synapses on hippocampal interneurons. Neuron 57 746–759. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano C., Cristino L., Luongo L., Siniscalco D., Petrosino S., Piscitelli F., et al. (2012). TRPV1-dependent and -independent alterations in the limbic cortex of neuropathic mice: impact on glial caspases and pain perception. Cereb Cortex 22 2495–2518. 10.1093/cercor/bhr328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobira P. H., Lima I. V., Batista L. A., De Oliveira A. C., Resstel L. B., Wotjak C. T., et al. (2017). N-arachidonoyl-serotonin, a dual FAAH and TRPV1 blocker, inhibits the retrieval of contextual fear memory: Role of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor in the dorsal hippocampus. J. Psychopharmacol. 31, 750–756. 10.1177/0269881117691567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grueter B. A., Brasnjo G., Malenka R. C. (2010). Postsynaptic TRPV1 triggers cell type-specific long-term depression in the nucleus accumbens. Nat. Neurosci. 13 1519–1525. 10.1038/nn.2685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagenacker T., Ledwig D., Busselberg D. (2011). Additive inhibitory effects of calcitonin and capsaicin on voltage activated calcium channel currents in nociceptive neurones of rat. Brain Res. Bull. 85 75–80. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. M., Bisogno T., Trevisani M., Al-Hayani A., De Petrocellis L., Fezza F., et al. (2002). An endogenous capsaicin-like substance with high potency at recombinant and native vanilloid VR1 receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 8400–8405. 10.1073/pnas.122196999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W. X., Min J. W., Liu Y. Q., He X. H., Peng B. W. (2014). Expression of TRPV1 in the C57BL/6 mice brain hippocampus and cortex during development. Neuroreport 25 379–385. 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Chen S. R., Pan H. L. (2021). Calcineurin regulates synaptic plasticity and nociceptive transmissionat the spinal cord level. Neuroscientist. [Online ahead of print], 10.1177/10738584211046888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado-Zavala J. I., Ramachandran B., Ahmed S., Halder R., Bolleyer C., Awasthi A., et al. (2017). TRPV1 regulates excitatory innervation of OLM neurons in the hippocampus. Nat. Commun. 8:15878. 10.1038/ncomms15878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S. J., Burette A., Rustioni A., Valtschanoff J. G. (2004). Vanilloid receptor VR1-positive primary afferents are glutamatergic and contact spinal neurons that co-express neurokinin receptor NK1 and glutamate receptors. J. Neurocytol. 33 321–329. 10.1023/B:NEUR.0000044193.31523.a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida T., Shimizu I., Nealen M. L., Campbell A., Caterina M. (2005). Attenuated fever response in mice lacking TRPV1. Neurosci. Lett. 378 28–33. 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen T., Edwards J. G. (2012). Calcineurin is required for TRPV1-induced long-term depression of hippocampal interneurons. Neurosci. Lett. 510 82–87. 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X., Morsy N., Winston J., Pasricha P. J., Garrett K., Akbarali H. I. (2004). Modulation of TRPV1 by nonreceptor tyrosine kinase, c-Src kinase. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 287 C558–C563. 10.1152/ajpcell.00113.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson U., Sundgren-Andersson A. K., Johansson S., Krupp J. J. (2005). Capsaicin augments synaptic transmission in the rat medial preoptic nucleus. Brain Res. 1043 1–11. 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.10.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasckow J. W., Mulchahey J. J., Geracioti T. D., Jr. (2004). Effects of the vanilloid agonist olvanil and antagonist capsazepine on rat behaviors. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 28 291–295. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona I., Freund T. F. (2012). Multiple functions of endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. Ann. Rev. Neurosci. 35 529–558. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauer J. A., Gibson H. E. (2009). Hot flash: TRPV channels in the brain. Trends Neurosci. 32 215–224. 10.1016/j.tins.2008.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Cui L., Kim J., Kim S. J. (2009). Transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 receptor regulates glutamatergic synaptic inputs to the spinothalamic tract neurons of the spinal cord deep dorsal horn. Neuroscience 160 508–516. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Lee S., Kim J., Ham S., Park J. H. Y., Han S., et al. (2020). Ca2+-permeable TRPV1 pain receptor knockout rescues memory deficits and reduces amyloid-beta and tau in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 29 228–237. 10.1093/hmg/ddz276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong W., Wang X., Yang X., Huang W., Han S., Yin J., et al. (2019). Activation of TRPV1 contributes to recurrent febrile seizures via inhibiting the microglial M2 phenotype in the immature brain. Front. Cell Neurosci. 13:442. 10.3389/fncel.2019.00442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulisch C., Albrecht D. (2013). Effects of single swim stress on changes in TRPV1-mediated plasticity in the amygdala. Behav. Brain Res. 236 344–349. 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Singh O., Singh U., Goswami C., Singru P. S. (2018). Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1-6 (Trpv1-6) gene expression in the mouse brain during estrous cycle. Brain Res. 1701 161–170. 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. H., Ledri M., Toth B., Marchionni I., Henstridge C. M., Dudok B., et al. (2015). Multiple forms of endocannabinoid and endovanilloid signaling regulate the tonic control of GABA release. J. Neurosci. 35 10039–10057. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4112-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. B., Mao R. R., Zhang J. C., Yang Y., Cao J., Xu L. (2008). Antistress effect of TRPV1 channel on synaptic plasticity and spatial memory. Biol. Psychiatry 64 286–292. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C. W., Lin T. Y., Hsie T. Y., Huang S. K., Wang S. J. (2017). Capsaicin presynaptically inhibits glutamate release through the activation of TRPV1 and calcineurin in the hippocampus of rats. Food Funct. 8 1859–1868. 10.1039/c7fo00011a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccarrone M., Rossi S., Bari M., De Chiara V., Fezza F., Musella A., et al. (2008). Anandamide inhibits metabolism and physiological actions of 2-arachidonoylglycerol in the striatum. Nat. Neurosci. 11 152–159. 10.1038/nn2042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maione S., Cristino L., Migliozzi A. L., Georgiou A. L., Starowicz K., Salt T. E., et al. (2009). TRPV1 channels control synaptic plasticity in the developing superior colliculus. J. Physiol. 587 2521–2535. 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.171900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna S. S., Umathe S. N. (2012). A possible participation of transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 channels in the antidepressant effect of fluoxetine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 685 81–90. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli S., Di Marzo V., Florenzano F., Fezza F., Viscomi M. T., Van Der Stelt M., et al. (2007). N-arachidonoyl-dopamine tunes synaptic transmission onto dopaminergic neurons by activating both cannabinoid and vanilloid receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology 32 298–308. 10.1038/sj.npp.1301118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrone M. C., Morabito A., Giustizieri M., Chiurchiu V., Leuti A., Mattioli M., et al. (2017). TRPV1 channels are critical brain inflammation detectors and neuropathic pain biomarkers in mice. Nat. Commun. 8:15292. 10.1038/ncomms15292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch R., Foeller E., Rammes G., Bunck M., Kossl M., Holsboer F., et al. (2007). Reduced anxiety, conditioned fear, and hippocampal long-term potentiation in transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 receptor-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 27 832–839. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3303-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcnaughton N., Corr P.J. (2004). A two-dimensional neuropsychology of defense: fear/anxiety and defensive distance. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 28, 285–305. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedeva Y. V., Kim M. S., Usachev Y. M. (2008). Mechanisms of prolonged presynaptic Ca2+ signaling and glutamate release induced by TRPV1 activation in rat sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. 28 5295–5311. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4810-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezey E., Toth Z. E., Cortright D. N., Arzubi M. K., Krause J. E., Elde R., et al. (2000). Distribution of mRNA for vanilloid receptor subtype 1 (VR1), and VR1-like immunoreactivity, in the central nervous system of the rat and human. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 3655–3660. 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan M. J. (2003). The neurobiology and control of anxious states. Prog. Neurobiol. 70, 83–244. 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00087-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake T., Shirakawa H., Nakagawa T., Kaneko S. (2015). Activation of mitochondrial transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 channel contributes to microglial migration. Glia 63 1870–1882. 10.1002/glia.22854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinas A. J. R., Desmoulins L. D., Hamling B. V., Butcher S. M., Anwar I. J., Miyata K., et al. (2019). Interaction between TRPV1-expressing neurons in the hypothalamus. J. Neurophysiol. 121 140–151. 10.1152/jn.00004.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller C., Morales P., Reggio P. H. (2018). Cannabinoid ligands targeting TRP channels. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11:487. 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musella A., De Chiara V., Rossi S., Prosperetti C., Bernardi G., Maccarrone M., et al. (2009). TRPV1 channels facilitate glutamate transmission in the striatum. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 40 89–97. 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam J. H., Park E. S., Won S. Y., Lee Y. A., Kim K. I., Jeong J. Y., et al. (2015). TRPV1 on astrocytes rescues nigral dopamine neurons in Parkinson’s disease via CNTF. Brain 138 3610–3622. 10.1093/brain/awv297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarria A., Tamburella A., Iannotti F. A., Micale V., Camillieri G., Gozzo L., et al. (2014). The dual blocker of FAAH/TRPV1 N-arachidonoylserotonin reverses the behavioral despair induced by stress in rats and modulates the HPA-axis. Pharmacol. Res. 87 151–159. 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhofer D., Lassalle O., Manzoni O. J. (2018). Muscarinic M1 receptor modulation of synaptic plasticity in nucleus accumbens of wild-type and fragile X mice. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 9 2233–2240. 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto-Posadas A., Picazo-Juarez G., Llorente I., Jara-Oseguera A., Morales-Lazaro S., Escalante-Alcalde D., et al. (2011). Lysophosphatidic acid directly activates TRPV1 through a C-terminal binding site. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8 78–85. 10.1038/nchembio.712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasierski M., Szulczyk B. (2020). Capsaicin inhibits sodium currents and epileptiform activity in prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons. Neurochem. Int. 135:104709. 10.1016/j.neuint.2020.104709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar L. S., Ahern G. P. (2000). Induction of vanilloid receptor channel activity by protein kinase C. Nature 408 985–990. 10.1038/35050121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puente N., Cui Y., Lassalle O., Lafourcade M., Georges F., Venance L., et al. (2011). Polymodal activation of the endocannabinoid system in the extended amygdala. Nat. Neurosci. 14 1542–1547. 10.1038/nn.2974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts J. C., Davis J. B., Benham C. D. (2004). [3H]Resiniferatoxin autoradiography in the CNS of wild-type and TRPV1 null mice defines TRPV1 (VR-1) protein distribution. Brain Res. 995 176–183. 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum T., Simon S. A. (2007). “TRPV1 receptors and signal transduction,” in TRP Ion Channel Function in Sensory Transduction and Cellular Signaling Cascades, eds Liedtke W. B., Heller S.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum T., Gordon-Shaag A., Munari M., Gordon S. E. (2004). Ca2+/calmodulin modulates TRPV1 activation by capsaicin. J. Gen. Physiol. 123 53–62. 10.1085/jgp.200308906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R. A. (2003). Anandamide and vanilloid TRPV1 receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 140 790–801. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino T., Realini N., Castiglioni C., Guidali C., Vigano D., Marras E., et al. (2008). Role in anxiety behavior of the endocannabinoid system in the prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex 18 1292–1301. 10.1093/cercor/bhm161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffarzadeh F., Eslamizade M. J., Ghadiri T., Modarres Mousavi S. M., Hadjighassem M., Gorji A. (2015). Effects of TRPV1 on the hippocampal synaptic plasticity in the epileptic rat brain. Synapse 69 375–383. 10.1002/syn.21825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samie M., Xu H. (2011). “Studying TRP channels in intracellular membranes,” in TRP Channels, ed. Zhu M. X.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez J. F., Krause J. E., Cortright D. N. (2001). The distribution and regulation of vanilloid receptor VR1 and VR1 5’ splice variant RNA expression in rat. Neuroscience 107 373–381. 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00373-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasamura T., Sasaki M., Tohda C., Kuraishi Y. (1998). Existence of capsaicin-sensitive glutamatergic terminals in rat hypothalamus. Neuroreport 9 2045–2048. 10.1097/00001756-199806220-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif-Naeini R., Ciura S., Bourque C. W. (2008). TRPV1 gene required for thermosensory transduction and anticipatory secretion from vasopressin neurons during hyperthermia. Neuron 58 179–185. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R., Bansal Y., Parhar I., Kuhad A., Soga T. (2019). Neuropsychiatric implications of transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV) channels in the reward system. Neurochem. Int. 131 104545. 10.1016/j.neuint.2019.104545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starowicz K., Cristino L., Di Marzo V. (2008). TRPV1 receptors in the central nervous system: potential for previously unforeseen therapeutic applications. Curr. Pharm. Des. 14 42–54. 10.2174/138161208783330790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storozhuk M. V., Zholos A. V. (2018). TRP channels as novel targets for endogenous ligands: focus on endocannabinoids and nociceptive signalling. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 16 137–150. 10.2174/1570159X15666170424120802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudbury J. R., Bourque C. W. (2013). Dynamic and permissive roles of TRPV1 and TRPV4 channels for thermosensation in mouse supraoptic magnocellular neurosecretory neurons. J. Neurosci. 33 17160–17165. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1048-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzian A. L., Aguiar D. C., Guimaraes F. S., Moreira F.A. (2009). Modulation of anxiety-like behaviour by Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid Type 1 (TRPV1) channels located in the dorsolateral periaqueductal gray. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 19, 188–195. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzian A. L., Dos Reis D. G., Guimaraes F. S., Correa F. M., Resstel L. B. (2014). Medial prefrontal cortex transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) in the expression of contextual fear conditioning in Wistar rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 231 149–157. 10.1007/s00213-013-3211-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tognetto M., Amadesi S., Harrison S., Creminon C., Trevisani M., Carreras M., et al. (2001). Anandamide excites central terminals of dorsal root ganglion neurons via vanilloid receptor-1 activation. J. Neurosci. 21 1104–1109. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01104.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M., Caterina M. J., Malmberg A. B., Rosen T. A., Gilbert H., Skinner K., et al. (1998). The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron 21 531–543. 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80564-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth A., Blumberg P. M., Boczan J. (2009). Anandamide and the vanilloid receptor (TRPV1). Vitam Horm 81 389–419. 10.1016/s0083-6729(09)81015-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth A., Boczan J., Kedei N., Lizanecz E., Bagi Z., Papp Z., et al. (2005). Expression and distribution of vanilloid receptor 1 (TRPV1) in the adult rat brain. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 135 162–168. 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M., Koga K., Chen T., Zhuo M. (2017). Neuronal and microglial mechanisms for neuropathic pain in the spinal dorsal horn and anterior cingulate cortex. J. Neurochem. 141 486–498. 10.1111/jnc.14001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellani V., Mapplebeck S., Moriondo A., Davis J. B., Mcnaughton P. A. (2001). Protein kinase C activation potentiates gating of the vanilloid receptor VR1 by capsaicin, protons, heat and anandamide. J. Physiol. 534 813–825. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00813.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Huang W., Lu J., Chen H., Yu Z. (2021). TRPV1-mediated microglial autophagy attenuates Alzheimer’s disease-associated pathology and cognitive decline. Front. Pharmacol. 12:763866. 10.3389/fphar.2021.763866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Sun B. L., Xiang Y., Tian D. Y., Zhu C., Li W. W., et al. (2020a). Capsaicin consumption reduces brain amyloid-beta generation and attenuates Alzheimer’s disease-type pathology and cognitive deficits in APP/PS1 mice. Trans. Psychiatry 10:230. 10.1038/s41398-020-00918-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Tu S., Zhang J., Shao A. (2020b). Roles of TRP channels in neurological diseases. Oxid Med. Cell Longev 2020:7289194. 10.1155/2020/7289194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. E., Ko S. Y., Jo S., Choi M., Lee S. H., Jo H. R., et al. (2017). TRPV1 regulates stress responses through HDAC2. Cell Rep. 19 401–412. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Yang X. L., Kong W. L., Zeng M. L., Shao L., Jiang G. T., et al. (2019). TRPV1 translocated to astrocytic membrane to promote migration and inflammatory infiltration thus promotes epilepsy after hypoxic ischemia in immature brain. J. Neuroinf. 16:214. 10.1186/s12974-019-1618-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng H. J., Patel K. N., Jeske N. A., Bierbower S. M., Zou W., Tiwari V., et al. (2015). Tmem100 is a regulator of TRPA1-TRPV1 complex and contributes to persistent pain. Neuron 85 833–846. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing J., Li J. (2007). TRPV1 receptor mediates glutamatergic synaptic input to dorsolateral periaqueductal gray (dl-PAG) neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 97 503–511. 10.1152/jn.01023.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R., Xiong Z., Liu C., Liu L. (2014). Inhibitory effects of capsaicin on voltage-gated potassium channels by TRPV1-independent pathway. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 34 565–576. 10.1007/s10571-014-0041-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Burrell B. D. (2010). Endocannabinoid-dependent LTD in a nociceptive synapse requires activation of a presynaptic TRPV-like receptor. J. Neurophysiol. 104 2766–2777. 10.1152/jn.00491.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Burrell B. D. (2013). Nonnociceptive afferent activity depresses nocifensive behavior and nociceptive synapses via an endocannabinoid-dependent mechanism. J. Neurophysiol. 110 2607–2616. 10.1152/jn.00170.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaelzer C., Hua P., Prager-Khoutorsky M., Ciura S., Voisin D. L., Liedtke W., et al. (2015). DeltaN-TRPV1: a molecular co-detector of body temperature and osmotic stress. Cell Rep. 13 23–30. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Ruwe D., Saffari R., Kravchenko M., Zhang W. (2020). Effects of TRPV1 activation by capsaicin and endogenous n-arachidonoyl taurine on synaptic transmission in the prefrontal cortex. Front. Neurosci. 14:91. 10.3389/fnins.2020.00091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Xu W., An D., Sha S., Men C., Li Y., et al. (2021). Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 activation inhibits the delayed rectifier potassium channels in hippocampal pyramidal neurons: an implication in pathological changes following pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. J. Neurosci. Res. 99 914–926. 10.1002/jnr.24749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zschenderlein C., Gebhardt C., Von Bohlen Und Halbach O., Kulisch C., Albrecht D. (2011). Capsaicin-induced changes in LTP in the lateral amygdala are mediated by TRPV1. PLoS One 6:e16116. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]