Highlights

-

•

Photovoice as novel strategy exploring concerns of those left behind to migration.

-

•

Economic opportunity, violence and access to education are driving immigration.

-

•

Changes in societal structure and values are responsible for many health concerns.

-

•

Mental health challenges, sadness and loss are experienced by children and adults.

-

•

Increased substance use as coping mechanism and young adults vulnerable to gangs.

Keywords: Migration, Mental health, Guatemala, Photovoice, Central America, Transnational

Abstract

Migration from Central America to the United States has become a strategy to escape economic poverty, exclusionary state policies and violence for people of Mayan descent. Under the principles Community Based Participatory Research, we explored the health concerns of Indigenous Mayans in rural migrant-sending communities of Guatemala using their own visual images and narratives through a Social Constructivist lens. Half of households in the study region have at least one member emigrated to the United States, making many “transnational families.” Focus groups and photographs and narratives from 20 Photovoice participants, aged 16–65, revealed significant health challenges related to conditions of poverty. Drivers of immigration to the United States included lack of access to healthcare, lack of economic opportunity, and an inability to pay for children's education. Health implications of living in communities “left-behind” to immigration centered around changes in societal structure and values. Mental health challenges, sadness and loss were experienced by both children and adults left behind. An increase in substance use as a coping mechanism is described as increasingly common, and parental absence leaves aging grandparents raising children with less guidance and supervision. Lack of economic opportunity and parental supervision has left young adults vulnerable to the influence of cartel gangs that are well-established in this region. Findings from this study provide insight into challenges driving immigration, and the health impacts faced by rural, Indigenous communities left behind to international immigration. Results may inform research and interventions addressing disparities and strategies to cope with economic and health challenges.

1. Introduction

Guatemalan Mayan people in the rural highlands emigrate to the United States at high rates as a result of economic poverty, exclusionary state policies, and gang violence. For many Indigenous Guatemalans, their current circumstances of extreme poverty are tied to years of government oppression, a violent civil war, and genocide (Diskin, 1985; Black et al., 1984). Guatemala's recent history includes a 36-year civil war that ended in 1996. The Ladino government and military, with support from the United States, was responsible for the deaths of more than 200,000 people from some of the poorest areas of Guatemala (Schlesigner and Kinzer, 2005; Science, 1999). In highland Maya communities, the military was involved in more than 90% of 669 massacres of Indigenous people with many of these attacks being forcibly carried out in part by members within their own communities (Carmack, 1988; Guatemala, 1988; Ross, 2006).

Immigrants from Guatemala fled to the United States as refugees during the war, setting off the first waves of immigration north in the 1960s (Davy, 2006; Hamilton, 2001; Menjivar and Abrego, 2009). The civil war and subsequent economic policies that favor large-scale agricultural exports like the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) have resulted in financial pressure on rural Indigenous families (Cohen, 2006; WOLA, 2003). As with many areas that suffer from severe poverty, exclusionary policies, and weak government, gang violence and murder rates postwar have escalated, making Guatemala one of the most violent and dangerous countries in the world (Achiume, 2017; Achiume, 2019).

Drug trafficking and cartels in Guatemala became one of the dominant power structures in the postwar period in the 1990s, and was connected with the drug trade in Mexico and Colombia and exported into the United States (Martinez, 2016). Cartels began working with corrupt military officials and law enforcement to create transport channels through Guatemala. This resulted in the rise of Guatemalan gangs and cartel groups with their own power structures in rural and border areas where drug trafficking routes emerged (McGuire and Martin, 2007). These structures are still in force today in rural regions surrounding the border between Guatemala and Mexico and continue to lure and force participation of rural farming communities.

In addition to violence, financial issues are often stated as the top reason for households to incur substantial debt and send family members as undocumented workers to the United States (Jonas and Rodriguez, 2014). The lack of economic opportunities and ongoing violence have prompted decisions to leave home to risk dangerous and expensive passage to the United States, creating “transnational families.” Remittances from the United States to Guatemala accounted for more than 12% of GDP in 2018 (Orozco et al., 2018). Despite the advances in economic stability that these remittances create for many families, research has documented that separation due to out-migration result in negative psychosocial consequences for those left behind (Jones et al., 2004; Suarez-Orozco et al., 2002). Transnational families face a unique set of challenges, including negative psychological and social impacts, feelings of isolation and sadness from separation, and financial and other stresses that result from the threat of deportation from the US (Brabeck and Qingwen, 2010; Brabeck et al., 2011).

According to the US Customs and Border Protection Agency, in FY 2021 there were 235,035 individuals with origins in Guatemala apprehended trying to cross the Southwest border of the United States (United States, 2021). The border region between Guatemala and Mexico is one of the largest outmigration regions (Jonas and Rodriguez, 2014) in all of Central America and Mexico (O'Conner et al., 2019). The rural highlands within the departments of San Marcos and Huehuetenango, which are located in this border region, are the largest migrant sending areas in all of Guatemala (O'Conner et al., 2019). The specific setting for this research is in rural highland communities of the Tajumulco municipality, within the department of San Marcos. People living in Tajumulco are of mostly Indigenous Maya descent, and have been through civil war and genocide, and continue to experience institutionalized structural violence and discrimination by the state (McNeish and Rivera, 2009; Manz, 2008). Many Indigenous Maya in this region reside in rural communities without paved roads and basic social services, usually several hours away from medical care, and without sufficient economic opportunity to sustain their families (Chamarbagwala and Morán, 2011).

Mayan people in the rural areas of Guatemala use immigration to the United States as a strategy in response to lack of opportunity, to alleviate conditions of poverty (Taylor et al., 2006), and to escape violence; however, research suggests there are health and social consequences for Mayan communities left-behind to international emigration (Brabeck et al., 2011; Lykes, 2010; Crosby and Lykes, 2011; Hershberg and Lykes, 2013). The overwhelming breadth of immigration research focuses on those that have settled in an international destination. While there are consequences for both those that have emigrated and those that are left behind, scholarship often focuses on the economic necessity and sacrifice of those who have left home (Lykes and Sibley, 2013). Much less is known about the impacts of immigration on those living in communities of origin. This study begins to fill that gap in literature, focusing instead on the health and well-being of those left behind in rural Indigenous communities with drastically and rapidly changing social structures as a result of emigration.

While their social structures at home are changing, they are building new familial and network structures as “transnational families.” Many of the residents in the study region, including most of our participants have some kind of transnational relationships they are negotiating. Transnational families navigate relationships, make decisions, and share risk from across borders as a strategy of economic and social mobility (Bryceson, 2019; Oso and Suarez-Grimalt, 2017; Oso and Suarez-Grimalt, 2018). They use migration as an investment for the whole family unit, generating resources to provide education for children and further mobility for future generations (Oso and Suarez-Grimalt, 2017; Oso and Suarez-Grimalt, 2018). Transnational families are held together because of the need for collective welfare (Bryceson, 2019). However, literature has documented that maintaining those relationships at a distance comes at high emotional costs to both those that have emigrated and those left behind (Bryceson, 2019; Graham and Jordan, 2011; Dillon and Walsh, 2012; Boccagni, 2015; Graham et al., 2015; Fan and Parreñas, 2018). Transnational families are also changing the landscape of parenting and emotional support, with advances in communication technology allowing families to maintain contact without being present for even decades at a time (Bryceson, 2019).

This study builds upon previous participatory research with Indigenous Maya in different language and geographical subgroups. No known study has utilized methods of Photovoice and Focus Groups with Mam to draw upon native voices and images to address health challenges faced as high-volume “sending” communities. While there have been qualitative studies done with left behind populations of K'iche speaking Maya in the central highland region of Guatemala, (Brabeck et al., 2011; Lykes, 2010; Crosby and Lykes, 2011; Hershberg and Lykes, 2013; Lykes and Scheib, 2015; Sánchez Ares and Lykes, 2016; Lykes et al., 2020) the experiences of those linguistically, geographically and culturally distinct groups cannot be assumed to be the same as those of Mam speaking Maya in the western highlands living in proximity to a heavily trafficked international border. This study allows us to hear and see the perspectives of this distinct Indigenous population that has not previously been represented in literature concerning “left behind” populations. The Maya Mam of the Western Highlands share a common Mayan ancestry with Indigenous communities in the Central Highlands but are recognized as a different ethnic group, with their own variant of the Mayan language, cultural practices, and traditional style of dress. The experience of one Indigenous linguistic ethnic group cannot be generalized to that of another, despite the shared common linguistic ancestry; furthermore, we do not know if the health concerns of those living in a migrant sending community on a heavily trafficked international border are shared with those living in the central region of Guatemala. This study builds upon the small body of literature that explores the experiences and health concerns of Indigenous Maya that have lived through oppression and genocide and that are now surviving in communities experiencing rapid changes from out-migration.

The overall objective of this study is to provide a platform by which Indigenous members of a high-volume migrant sending area in Guatemala can share their own narratives about the current and future challenges they perceive to the health and well-being of their own communities. This study was designed and implemented using principles of Community Based Participatory Research. CBPR requires that participants are involved in data production, as their health status can only be understood through the lens of their own life contexts (Castleden et al., 2008). Community leadership and community members were involved in every step of the design and implementation, including the topics covered in Focus Groups, the use of Photovoice techniques, and the narrowing of information learned in Focus Groups to inform the Photovoice research question. Interpretation of data in this study follows Social Constructivist Theory. In social constructivism, subjective meanings of the world in which an individual lives are varied and multiple, with the goal of relying on the participants’ views of their own surroundings. Questions are broad and general, and the goal is to rely on the participants’ views (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011; Crotty, 1998; Mertens, 2015; Burr, 2015; Lincoln and Guba, 2000; Schwandt, 2007).

2. Methods

This research explores the challenges to health and prosperity of rural Indigenous Guatemalan communities through open ended interviews. Through this process, Indigenous Maya narrate their concerns for the future of their communities, the changes occurring as they adapt to out-migration, and the health consequences, as they understand them, of these shifts in culture and practice. Data informing this manuscript was collected in two rounds of field research. Focus groups were conducted in August of 2016 to identify health concerns held by the communities in this study. Secondly, focus group data informed the research question addressed by participants using Photovoice and interviews in January of 2018. Preliminary themes were also shared in discussion with both interview participants and community leaders to validate findings, and are included where appropriate in the results presented here. The use of these methods have been successfully incorporated in previous research documenting the experiences and consequences of migration for Indigenous Maya that has taken place since the end of the civil war in Guatemala. (Brabeck et al., 2011; Lykes, 2010; Crosby and Lykes, 2011; Hershberg and Lykes, 2013; Lykes and Scheib, 2015; Sánchez Ares and Lykes, 2016; Lykes et al., 2020)

2.1. Focus groups

Two gender-separate focus groups were conducted with twenty participants each, using a series of semi-structured open-ended questions. Question content areas included: (1) perceptions of important health issues: (2) challenges facing young people, and; (3) the future of their community. Holding more than one group with each gender, and with only 10 participants each would have allowed for more time and space for each participant's views, and allowed for evolution of the group moderation; however, given the physical constraints on travel in this region, the burden on participants to walk great distances from household and work duties, and to accommodate the many residents that showed up to take part in groups, it was decided upon to allow entry to 20 participants in each group. Genders were separated because of cultural concerns about perception of others’ spouses and community members, and cultural gender differences in employment, mobility, and household roles. Genders were also conducted separately to account for and contrast differences between men and women with regard to the content areas addressed. Focus group participants ranged in age from 18 to 65 years in order to account for and compare the different viewpoints across age sets, and were recruited non-randomly. Leaders facilitated communication about focus group participation to residents across 11 communities. Focus group participation was offered across all 11 communities in the region to encompass the possible differences in opinions about the topic areas between different communities. Focus groups were held concurrently at a central health facility and a central church salon. These locations are the standard meeting commons for all matters involving the 11 communities in the area. Communities were informed that the first twenty participants to arrive at the specified time would be included in the study. Participants were compensated for the time equivalency of hours of work missed (20 Quetzales). This amount was decided upon by the author and community leaders as an amount that was fair for time away from work and not a large enough amount to be considered coercive for participation. Focus group participants were each informed of their rights and of confidentiality procedures, and consent was obtained from each. Focus groups were conducted in Spanish, with a trained bi-lingual assistant, fluent in both Mam and Spanish present at each group to address any linguistic or cultural confusion. Focus groups were each moderated by a native Spanish speaker and assisted by a fluent Spanish speaker. To respect cultural gender norms and comfort of participants, the women's focus group was conducted by a female moderator and assistant, and the men's group by males. Moderators and assistants for both groups each have 15+ years of experience working with communities in the area.

2.1.1. Philosophical assumptions and frameworks

The use of focus groups with a marginalized, Indigenous population is only appropriate when culturally relevant, and depends on the level of cultural expertise of researchers when coding and theming responses (Perez and Brett, 2017). Previous research in Guatemala has successfully utilized culturally relevant focus groups as part of a sequential research design of community-based research to address health issues in rural migrant sending areas (Cooper and Yarbrough, 2010).

Given the content area, focus group interviews were designed for the narrative voice to be incorporated, exploring the shared and individual experiences and opinions of being a member of a rapidly changing Indigenous culture. Experiences are expressed in the lived and told stories of individuals within the specific context of their shared history, geographic space, and cultural heritage (Clandinin, 2013). Philosophical assumptions are ontological, as focus groups explore the nature of reality in terms of current and future health, and the forces impacting them (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011; Crotty, 1998). Ontological assumptions consider that there are multiple realities for lived experiences, and employs various forms of evidence to develop themes using the words of individuals and their differing perspectives. Focus groups were interpreted through a social constructivist lens, through which participants construct their own narratives based on their perceived experience of the world in which they live (Denzin and Lincoln, 2003). However, some aspects of transformative interpretation are also present, as focus groups serve as an empowering force for participants in vocalizing shared experiences and opinions, and findings are used to uncover what is most important to community members for the next stage of research. Transformative interpretation recognizes that knowledge is not neutral and reflects power and social relationships in society, with a purpose of aiding in improving it, especially for marginalized groups (Mertens, 2003; Mertens et al., 2013).

2.2. Photovoice

Findings from focus group meetings were discussed with community leaders, and the use of Photovoice was decided upon as an effective tool for allowing residents the opportunity to decide what was important for them to share about their own communities. The main research question for the Photovoice phase was decided upon in partnership between the author and the community. Using Photovoice was chosen to give ownership to participants, honoring the interpretations they deem important. This phase was undertaken to understand the lived experiences of cultural change due to out-migration, and how this impacts health in rural Indigenous communities. Twenty community members, ages 16–65 were chosen non-randomly from within all 11 communities in the study region. Community leaders informed their constituents of the study and those interested were invited to retrieve a camera from the investigator at a specified date and time. The first twenty people to arrive were included in the study (all participants were able to speak Spanish). While allowing more participants across all 11 communities would have been more inclusive, the number was decided upon between community leaders and the author as a manageable sample size that would still allow for a generous cross-section of socio-demographic characteristics. Photovoice participants were each informed of their rights and of confidentiality procedures, and consent was obtained from each. Participants were then given the following general research question to explore through photographs over a one-week period: “Document images that represent any changes in your community that may impact the health and future of your community.” Cameras were collected again after one week and photographs were developed and coded numerically for discussion. Participants returned to discuss between 5 and 10 photographs from their collection through semi-structured individual interviews conducted in Spanish. Photovoice participants were compensated for the time equivalency of hours of work missed (50 Quetzales). This amount was also decided upon by the author and community leaders as an amount that was fair for time away from work and not a large enough amount to be considered coercive for participation.

2.2.1. Philosophical assumptions and framework

Photovoice technique involves the use of photographs taken by the participants themselves as a visual tool during their individual interviews (Wang and Burris, 1997; Nykiforuk et al., 2011). Photovoice is different from standard photo elicitation because it is typically used in participatory action research in which participants are the agent of documentation (Sutton-Brown, 2014; Dockett et al., 2017). Photovoice combines photography, dialog and experiential knowledge to allow participants to communicate community concerns, social problems and to inspire social change (Sutton-Brown, 2014). The photovoice technique allows participants to use photographs as a place to externalize emotions felt during experiences, using the personal photographs as a focal point for dialog (Nykiforuk et al., 2011). This technique has been successful as a tool to support Indigenous individuals in contextualizing experiences, and positions Indigenous peoples’ own knowledge and values at the center of research (Shea et al., 2011; McHugh et al., 2013; Goodman et al., 2018; Novak, 2010). The methodology is intended to create an environment whereby participants are able to describe and discuss distressing or traumatizing events by referencing those emotions through a photograph. Rather than confine their experiences to structured interview questions, this method allows individuals to share their perceptions and lived experiences using their own visual perception of the world around them. It would be impossible to assume the perspective of a rural Indigenous person living in the circumstances of poverty without having lived that experience. This methodology does not accomplish such insight; rather, the methodology provides a more equitable and less manipulated expression by participants.

The photovoice technique and subsequent interviews follow narrative approaches. Narratives collect stories from individuals as well as documents, photographs, and group conversations, and occur within specific places or situations. Contexts include descriptions of physical, emotional and social situations, and using visual narrative inquiry can create a more complex understanding (Riessman, 2008).

Philosophical assumptions using photovoice include the theory of community-based participatory research (CBPR), in which knowledge development is democratized and community members themselves are involved in data production, ensuring data authentic to community experiences (Castleden et al., 2008). CBPR assumes that the health status of a group can only be understood from the group's own knowledge of its values, priorities, responses to life disruptions, perceptions of health, help-seeking behaviors, and context in which they live (Castleden et al., 2008). As stated by Wallerstein and Duran (2006), “More than a set of research methods, CBPR is an orientation to research that focuses on relationships between academic and community partners, with principles of co-learning, mutual benefit, and long-term commitment and incorporates community theories, participation, and practices into the research efforts” (Wallerstein and Duran, 2006). CBPR focuses on collaboration with participants in an effort to prevent further marginalization (Kemmis and Wilkinson, 1998).

2.2.2. Ethical considerations

The privacy and safety of participants were considered and protected in each phase of research. Particularly when using Photovoice, there are risks to anonymity of participants and other community members that might be captured in photographs. When designing this project, we took great care to ensure the safety of community members. Participants were given detailed instructions on omitting identifiable images, including geographic location and other individuals. Prior, during, and following the photovoice project, participants discussed confidentiality and consent with project facilitators. All participants indicated clear understanding of procedures for confidentiality and were ensured that their participation was voluntary, could be terminated by them at any time, or could be terminated by facilitators if confidentiality issues should arise. They were informed that in the case of termination of participation, photographs in possession of facilitators would be destroyed, as well as any other materials from their participation. Anonymity and safety of participants were discussed with International Review Board representatives at length, and it was agreed that the risk was minimal. The extremely rural nature of this region and the lack of technology to access collected data, make it virtually impossible for any individual participant to be identified and located. For those few photographs where human faces can be made out, appropriate consent was obtained from the individual. All participants were assigned a protected identification number and alias only accessible to the first author prior to project inception. No other identifying information was collected from participants beyond their age and first name.

2.3. Analysis

Analyses were performed using NVivo 12 software, version 12.2.0. Recordings were transcribed in Spanish and translated to English by two fluent Spanish speakers, with discussions to mitigate translation discrepancies. Focus groups and Photovoice interviews were transcribed and analyzed using an interpretive framework (Huberman and Miles, 1994; Bazely, 2013). Major themes were coded following a traditional process of coding and classification for major themes (Bazely, 2013). Iterative interpretation was followed to locate patterns, stories, summaries, statements, and axial relationships among the community (Marshall and Rossman, 2015). Discussions of preliminary findings with community leaders and Photovoice participants were also recorded, transcribed and translated under the same process as interviews. Segments were then organized under the major themes being addressed in that discussion segment.

2.4. Researcher community embeddedness

In qualitative research, the researcher serves as the primary instrument of data collection (Denzin and Lincoln, 2003). The first author has an 18-year history living and working with communities in the Tajumulco municipality. As a result, she has built trust with leaders and community members that positioned her to carry out the sensitive aspects of this study that might not otherwise have been feasible or as accurate. Many elements of this study required high levels of trust between community leaders, research participants, and researchers that are a result of decades of trauma and exploitation. While the main investigator is a white woman from the United States, she is fluent in Spanish and is a frequent and trusted presence within the homes of those living in the study site communities. In addition, a fluent speaker of both Maya Mam and Spanish was always present during data collection to clarify any language or cultural confusion with questions.

3. Results

3.1. Focus groups

Focus group participants described their current health challenges, revealing the difficulty of living in conditions of poverty. Both male and female focus group participants spoke about the difficulty of living without economic resources or opportunity in the rural highlands. Discussion crossed several subthemes, including specific illnesses faced by their communities and problems arising from lack of infrastructure, including access to clean water and healthcare. Though focus group discussions addressed an array of community health challenges, a concurrent thread running through the major themes and several subthemes within those, is their status as a migrant sending area, where more than half of households have at least one person that has emigrated to the United States undocumented. Participants addressed both the lack of resources that cause residents to seek economic opportunity elsewhere, and the vast changes occurring within communities as the population structure shifts. The major thematic axis that emerged in the focus groups was “changes in values, culture, and community structure,” and included “migration” and “mental health.” Major thematic axes within the Photovoice narratives included: “poverty and migration”; negative consequences of migration”; “the experience of migration,”; and “community changes.”

3.1.1. Changes in values, culture, and community structure

The majority of focus group discussions centered around a central theme of changes in values and family structures, and among young people in particular. The youth are becoming exposed to and involved with gang activity and substance use, including alcohol and drug abuse, and cigarette smoking. These were identified as marked changes in the cultural norms within these communities, within a timespan of just a few years. There was frequent mention of the presence of gang affiliation and associated drug use by youth in the area. Substance use was identified in children as young eight years old, with some participants suggesting that it is because, “they do not have any parents,” referring to children left behind by emigrant parents.

3.1.2. Migration

Many participants spoke about the impact of emigration from their communities to the United States. Men discussed the ages of those that migrate and why, “they are fifteen, eighteen, twenty. There is no work.” Women talked of the difficult journey and financial burden of crossing through Mexico undocumented to the United States, and the fears they had for their own children and family members attempting to cross. They spoke of the disappointment that comes with being apprehended during an attempt to cross and being returned to Guatemala with the financial debt accrued during the attempt. The male group in particular highlighted community changes that are taking place, especially among young people left behind by parents that have emigrated to the United States. They spoke of problems at home between children and care givers due to lack of guidance because of one or more missing parental figures. They also discussed the impacts this has on substance use by young people, and girls resorting to partnering and becoming young mothers themselves to survive. Women mentioned that girls, “some of twelve, some of thirteen and fourteen,” become pregnant because of the lack of guidance for young women and their exposure to technology like cell phones and television where they learn about sex very young. One male participant, age 56 gave the following example:

“…what I am seeing in these times, some children here their fathers or mothers have been sent. Because sometimes there are parents who have gone north. And when they come home to the children, they are already grown up. They never had advice from their father, they no longer respect it. Sometimes, on the contrary, you do not see your child until they have a child. He's even a father. He comes home and is no longer a father but a grandfather. Why? Because there is a lack of work here…they raise themselves, nobody guides them…But here we see that the girls are not able to work, they do not study. What they do is marry older people because there is no work…So, when the father comes back, the girl already has a child or the boy has a child.”

Migration away from home is considered both a necessity and a dream, but there is often a desire to return once enough money is made for a better life.

3.1.3. Mental health

Emerging instances of suicide and mental health struggles were of great concern to many participants. There was significant discussion of young people beginning to take their own lives, including one person remarking that, “five or six have already died.” One participant, age 45 whose nephew had died by hanging addressed the difficulties associated with a desperation that comes from living in a place without economic opportunity or choices. He spoke of leaving children behind to cross to the United States undocumented to provide for them, but leaving them without parental guidance, linking mental health problems and emigration:

“He was fourteen years old. He was still a child…Although we are sad — As we say, one struggles to provide for the children. You risk your life to cross in the desert. It's like us here, we are not the same as you there. You come here anytime you want. You go in and out, but we do not. And we get to where you live, and we stay a few years, five years or six, seven years. When we arrive, we think that our children are going to do well with their studies or that they are old so that they do not suffer from hunger. But when we come back, the children are grown up and one never knows where they are …”

Women spoke particularly of economic pressures and the lack of work as contributing to mental health stresses, especially if young people feel like they have to help provide for the family, “So they feel like they have to be older, of being very old when they are young and they do not have the ability to handle everything. They say, “my mom has no resources. My mommy does not have this. I'm going to be asking for it and it hurts to ask. I better go to work.” It is a lot of responsibility for a young man.” The frequency with which participants spoke of community changes related to emigration inspired the visual and descriptive documentation of those changes during the Photovoice project.

3.2. Photovoice

Based on the issues affecting community health identified by participants in focus groups, the general research question for the photovoice project was agreed upon by community leaders, participants, and the author. Photovoice participants were asked to document and describe changes that may impact the health and future of their communities through visual images and discussion.

Echoing themes identified in focus groups, participants felt compelled to document living conditions that make it difficult to thrive within their own communities. Narratives describing photographs of struggle and the desire to live with dignity centered around the impacts of emigration to the United States. Perceived impacts from emigration were both positive and negative, including economic opportunity, sacrifice and loss of family, and the mental health challenges of being left behind in a migrant sending community. Participants frequently documented major changes happening within their communities as social network structures shift from out migration. Narratives of these photographs describe changing values, increased substance use, and growing gang involvement among youth because of parental absence and lack of opportunity.

3.2.1. Poverty and migration

When contemplating photographs depicting conditions of poverty, several participants went on to relate those conditions to the necessity of migration to the United States. Men spoke of their own struggles, and of seeing their neighbors building homes that are safe, that they are proud of, and of wanting those things for their own families. Carlos, 34 described this feeling as making you, “want to leave your family, your mom or dad, your brothers, to have something like that. That is the reason why many people have immigrated from Guatemala to here [United States]. The poverty that is lived.” (Fig. 1) Brigida, 16 compared their own existence living in poverty to stray dogs sifting through dangerous garbage, alluding to their desire to live with dignity under different circumstances (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Carlos’ representation of the poverty in his community.

Fig. 2.

Brigida represents the desire to live with dignity with an image of stray dogs digging through garbage.

Men, who had experienced migration to the United States and returned, spoke about the great sacrifice they make when forced to leave their families to provide for them, and the loneliness they feel. One man quoted his uncle, who was living undocumented in the United States, as saying, “If it were not for damn poverty, I would not be here. I was with my children. But poverty is the need to make one come here and leave the family far away. It is the reality that we are living right now.”

Carlos, who was interviewed by the first author in the United States after crossing, gave an emotional testimony about being forced to leave all that he knew to support his family in a foreign land. With tears in his eyes and looking out in the distance, he said, “Because if I had money, I would have had my family. Well, I was with them. I was with them. I was not here. You think I do not miss my dad, my mom, my brothers. I want to walk on rainy afternoons over there. I want to play soccer, which is what I like to do. Then again, poverty makes you leave your family and look for an opportunity to survive. Not to get rich, not to make you a millionaire, but to survive.”

There was hope expressed in the discussions of themes in addition to acknowledging fears and challenging living conditions. Oscar, 25 felt it was important to tell us that the children are the future of his community and of his country. But with the lack of resources and lack of employment, he does not think their potential can be reached. He feared that the many beautiful traditions, the meals, the work they do in growing coffee, is in jeopardy. The population is increasing and there is no land for them to cultivate like there was in the past. Families of up to eight, ten children or more have limited access to education and there is no economic opportunity to support this growth with things as they are in his community.

3.2.2. Economic opportunity

All but two of the total 20 participants discussed emigration to the United States when reflecting on their photographs. Photographs offering comparisons between families that had people on the “other side” and those who did not have emigrant relatives were prevalent across all participants. Photographs depicting poverty, as well as those showing more expensive homes made of “block” and “cement” elicited comparisons between them in narratives. Participants emphasized the necessity for emigration to the United States for economic opportunity, as in their own communities there is little to no work, and education beyond primary school must be paid for.

When talking about emigration, participants realized the positive benefits of having someone who has crossed. Access to economic resources, the ability to construct safer, more beautiful homes, and being able to send children to school beyond the sixth grade were identified as positive changes they have experienced. Some relayed their own life experiences of making the dangerous journey across the desert in Mexico and crossing into the United States, or being the spouse of someone who has.

Many participants took photographs of homes that were built with the “fruits from the United States.” Comparisons of household resources for those who have people in the United States were also common. Forty-two-year-old Roberto, when discussing a photograph he took depicting a wooden house reflected in the rearview mirror of his truck, said, “Previously, many people had these little houses. Because there is not much money to buy blocks, to buy iron and cement. That is why they use wood. Because economic resources are needed.” He explained why some people still have homes constructed in this way: “The difference is that we still use the wood if they do not have money to build. They are poor people and years have passed and they have never had a family member that has gone to the United States to earn more money, so they continue to use that house and they can not do anything else but use that house.” (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Roberto describes a home that is possible with family in the United States.

Thirty-six-year-old Hector, while examining a photograph of a house he admired, also reflected on the perceived necessity of emigration to make a better life for your family, “Well, what I see is that, to have that in this community, I think for each person, if you want a house you have to save little by little or migrate there to the US. Here, we do not earn much. We only have enough for food, to support the family. One has to risk it all to immigrate there so that they can have a house like that. Because I imagine that the person who paid for this house has been in the United States for about ten or eight years. But yes, you can see that there is fruit from them.”

Men spent significant time discussing the desire to give to your family what others have been able to give through the sacrifice of leaving the family to emigrate north. Hector shared a photograph of his sister's house. He described that ten years ago there was no house like this, but that his brother-in-law, “built his house to support the family with the fruits from going to the United States…I liked taking a photo because I thought that one day, maybe God will be able to make me a house just like him. That I can have a house like this too…Before they did not have that and now they do. And for them it has improved because he migrated to North America.”

Several people also reflected on their own children making their way to the United States. Hugo, 35 felt that children have all set their sights on going to the United States, “Because there is not much possibility here. It's convenient and a little dangerous. They say, I am going to the United States to work, to bring money, to do better." Agustin, 37 said that his children already have the goal of going to the United States, and that most young people he knows have the goal to immigrate. He said it is because they suffer in Guatemala, and they want to prosper in their lives. He expressed, as other men had, that seeing others with resources from the United States is a driving force for young people to emigrate: “If God wants, my son or my children can, they will migrate there [to the US]…because at the moment, as it is, it is a bit sad because I have seen in other places the kitchens are more equipped, a normal kitchen. But I am waiting on God and God with us and with our children, they can migrate there and that is the hope we have for the future.” Thirty-year-old Teresa, whose husband was in the United States for many years and had since returned, would be happy to see her children go to the United States, because they can have their own things, their own houses, though she would prefer they are there with her in Guatemala. She expressed fear about them going, saying, “Perhaps, for example, they die there in the desert, you do not know if they will arrive or not. These are the risks you take as a mother with your children, but maybe, at the same time I would be happy and support them.”

The motivation to provide education for children was a pervasive theme when participants discussed emigration. Thirty-five-year-old Catarina, who is a primary school teacher in her community, shared a photograph of the school where she teaches. She explained that it represented the place where, thanks for parents who are in the United States, children are able to improve their lives. “It is a very important issue because many children only reach primary school. They cannot enter high school because they do not have enough money to continue. But thanks to many parents who travel to the United States to give their children the best, they are the ones who get ahead. Now the parents who stay here in this country are the children who can no longer advance with their studies.”

Community leaders confirmed that emigration out of their communities was indeed a central theme representing future health of their constituents. One community leader felt that a lot of problems were happening as a result of emigration, as people are leaving in large numbers, “looking for a life.” He felt that necessity was driving people away from their families, and that there “are many parents or families where there is always pain, there is sadness– Why? When one goes, it's very healthy, good. But sometimes they do not come back. They do not go back home, they no longer live there. It's the hardest thing for a family to be left without — no one is responsible for them anymore.” One leader spoke about families living in “severe poverty,” because they have been left behind by family members in the United States, and have not had resources sent to them. “Sometimes they do not have anything, nor do they have a roof to live in, malnourished children, and a wife worried that she will eat every day. And being here, we do not have any studies…but there is no work. That is why they migrate.” He expressed concern in his role of community leadership to support the young people, some of seventeen and younger, that already have families and are trying to make lives for themselves without leaving for the United States (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Catarina's depiction of children with the opportunity to study because of parents that have emigrated.

3.2.3. Positive impacts of migration

Participants recognized the many positive changes they experience because of having people in the United States. Simple things like having the ability to send money to build a bathroom for your home (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Carlos shares a bathroom in a home without someone in the United States.

Teresa, 30 was hopeful for children going to school in her community because parents have migrated and can now give them, “uniforms, supplies, and all that.” She described that in the past, parents worked their own land for subsistence but did not have other employment, and so only had enough money to support the family and not send children to school. She went on to talk about her own experience of being a spouse left behind to emigration. When her husband was gone in the United States, she was happy at one point because she was able to improve her house from lamina to block, and now she has a safer home during hurricanes and they do not suffer as much. However, at the same time she is sad because her children ask about their father and, “…they want to live together and you can not because, how beautiful everything is when you live together, parents and children. But no, sometimes it is difficult to explain to them, because they ask questi“Why is not my dad here?” or “Why did he leave?” Or sometimes they do not understand. At the same time, yes, but thank God that if they are in the United States, they can help us here.”

3.2.4. Negative consequences of migration

In addition to discussing the reasons for and positive benefits reaped from emigration, participants spoke frequently about the negative consequences of being part of communities left behind by emigrant family members. Sacrifice and suffering from the loss of family was a commonly cited consequence of emigration to the United States. Mental health challenges attributed to emigration of close social ties, as well as a dearth in parenting for children and teenagers were of particular concern.

Men and women both expressed the negative consequences associated with family and other network members leaving for the United States. Women in particular shared photographs and narratives depicting the suffering endured by those left behind in their communities. Carmen, 31 chose a photograph of an abandoned home to talk about. She said that the family that had lived there was broken apart, and now the home is broken apart as well, with water streaming in. She said it brought her great sadness to see homes like this, and families like this because some of them have gone to the United States (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Carmen represents a family broken apart.

3.2.5. Sacrifice and family loss

The theme of sacrifice and loss of family was common when discussing images related to emigration. The ability to send back resources was shadowed by the absence of important relationships in people's lives. Carlos, 34 recognized that most of the men in his community are leaving, and that most men he knew are now in the United States, leaving women alone back home. He shared a photograph of a very large home, and explained that only an older woman and her granddaughter live there, as everyone else is in the United States. Now they have a lovely home, but they suffer great sadness because none of the family is together. He said that the woman's hope is that the family will eventually return from the United States to live there with her, but this is not guaranteed. He explained that it is common for people to leave to make their money and then return home, but that often they never return: “Sometimes they do not come back. There are some who left fifteen, twenty years ago and have never returned. And the families, the abandoned children, are without parents and nothing. Women have gone with other men and so on, it is a lot of family destruction.”

Participants also recognized that when children are left behind to be raised by grandparents and other relatives, it has a negative impact on their behavior. Children raised without a father, and sometimes without either parent, face emotional burden and are not given the guidance they need to navigate life in their own communities. Catarina, a 35-year-old primary school teacher who sees this scenario often in her work put it best: “…it's difficult for a child to grow up with parents separated. The child always wants to see mom and dad together…It impacts the children, a lot, the separation and growing up without the love, the affection of a father. Well, those are the negative things that I look at.”

3.2.6. Mental health challenges

Participants identified the many mental health challenges they have noticed in their colleagues with family emigrated to the United States. Women are suffering with sadness at the loss of their husbands, and children are rebelling without proper guidance. Some are turning to destructive behaviors like drinking and using drugs, while others are struggling with depression and even suicide. Sixty-five-year-old Gilberto told us that, “so many young people are losing their health.” He went on to describe, just five days past, that a boy hanged himself, and that “There were several that have happened, like four have hanged themselves here. It was one here, a girl here on the fence. And another on the other side…Young, they are young. About fourteen. One of sixteen. One of seventeen. Yes, they are minors. Another twenty, it seems. So that is what happens now with the health of the entire community.”

In the discussion about themes, twenty-five-year-old Oscar talked about the pressures that are felt by men when they see their neighbors building their homes out of block with resources from the United States, compelling them to send their own relatives to cross. He also spoke of the pressure of cost to reach the United States, which causes another kind of mental distress: “We are talking about the cheapest that a trip can cost for a migrant to the United States is eighty thousand quetzals, the cheapest. There are even young people who will pay up to one hundred thousand, one hundred and twenty thousand for a trip. There are young people who do not make it on the first attempt. They have to try two, three, four times. Normally, like coyotes, as they are usually called - those who are in charge of taking people to the United States. They only give you two or three chances. There are people who lose those three attempts and do not arrive and continue spending.”

Gilberto, 65 agreed that the pressure for some families is overwhelming because they lack the means to send anyone across. He also spoke of the mental stress on children who are abandoned and grow up without an education because their fathers have left and do not send resources. One community leader explained this, saying, “Well, in many of the cases we have realized that there are men who leave for the United States and as soon as they arrive, they forget their wives that are here. And so they create a new family there. Abandoning his relatives who are here, his wife, his children.” All of the participants agreed that there is a sadness that comes from having family gone in the United States, even when that affords them a better life.

Community leaders agreed that there are more men than women away in the United States, and that women left behind “go through a depression. Because they are not with their husbands…they are not living together as a family.” The group recognized that in some instances, depression became so difficult that suicidal thoughts were common: “There are some who believe the idea if they are not with their husbands, then life has no meaning and some have even killed themselves.” Another committee member agreed, saying, “…then, there comes a time when they believe that it no longer makes sense to continue living because of all the problems and they have even committed suicide.”

Participants also recognized that men face mental health challenges around migration in their communities. Men who do not have the resources to make it to the United States themselves face great pressure and often turn to alcohol to escape their feelings of inadequacy. Men who do make it to the United States and then are deported back to Guatemala also suffer mental health consequences. The high price paid for passage puts families in debt to other families in their community, and when someone is deported and returned before they have paid that debt, there is a feeling of hopelessness and despair. Participants said that they fall into depression and instead of using their money to support their families, they “drown their sorrows.” Maria, 26 gave the example of one of her neighbors who she saw struggle with this. He was detained and deported three times attempting to cross, and began to drink more each time. With each attempt, the severity of the crime is worsened, and by his third deportation and detention, his wife was forced to attempt to cross into the United States herself. Maria said this man now lives in deep depression and alcoholism, alone in his house, as his wife has gone to the United States.

In discussion of themes, community leaders were concerned with how many men had gone to the United States and left children and women alone. They described men leaving when children are just four or five years old, and not returning for fifteen years. “And what do they do? They put the noose around the neck and hang themselves. And there they die. But it is the responsibility of the father or the mother for abandoning them.” According to one man on the committee, “…for lack of love and affection from parents, they feel alone.”

3.2.7. Experience of migration

Carlos, 34 shared his own “dangerous” journey traveling to the United States through Mexico. He described how he was beaten if he did not have the money to pay off officials he ran into along the way. He discussed how difficult it is to come up with the necessary fourteen thousand dollars required to cross undocumented, and what a momentous decision it is for them to leave: “In my mind, it's a very difficult decision for people. To use that money to cross. It is very difficult. It is the biggest decision you can make in your life. Especially if you have a wife, children, or a husband. Whatever is. That is difficult…I said, “I'm going to go. I'm going to help my family… And I have been able to help my family.” He emotionally conveyed the conflicted nature of being able to leave the family to help financially, but at the great cost of being without them: “At the same time, I am happy and sad because I can not be with my family. For example, important dates. Now that Christmas is coming and all that. One would like to be there. Who would not want to be with the family? To give everyone a hug. Receive midnight. I cannot.”

Thirty-five-year-old Catarina, whose husband left for the United States many years ago, wanted to share her story so that others would understand the great sacrifice that comes with economic opportunity in the United States: “Well, my husband and I got married, we had a child, but we did not have a home. We lived with the in-laws, with the brothers-in-law, and all there in the same house. We decided that he had to travel in order to build a house. Unfortunately, he found another woman there. Thank God he built the house for me. I stayed with my son, but he built my house. That was our wish, to have a nice house…but the negative, is that I lost my husband. So, there are positive and negative things that migration brings us…He stayed in the United States with another woman. But I am grateful to God and to him because he built my house…In other words, the price of that house was losing my husband.”

3.2.2. Community changes

Substance use: Of particular concern for community participants was the rising substance use in their communities. Several photographs were shared of cigarette butts and empty bottles of alcohol. To participants, this represented a significant change, and reflected the pain and sadness experienced by their neighbors. It was also a hallmark of the changing behavior of children lacking parental guidance because of emigration. Twenty-five-year-old Oscar, when talking about his photograph of discarded cigarettes, said that he knows children as young as ten years old that already smoke because their fathers are gone. He said he thinks these children feel smoking makes them look older and “command respect.” They are trying to fill a hole that is within them for lack of proper guidance and confidence from their parents.

Thirty-one-year-old Carmen, who had to pause during her narration because she began to cry, shared a photograph of an empty bottle of liquor and blamed adults for displaying this behavior in front of children. She also shared a photograph of a refrigerator in a small tienda. Now it was full of beer, but she said that in the past it had juices and no beer. She worries about what this is doing to her community, and said that the store owners put in juke boxes next to the refrigerators, so at night people gather there and drink next to the primary school. They are awake all night, and in the morning can be found sleeping in front of the children at school. Carmen explained that she became emotional while looking at this photograph, because it not only showed the problems in her community, but she was seeing the beauty of it as well for perhaps the last time. Carmen was leaving for the United States with her baby daughter in tow the following morning, and feared she was seeing her home for the last time in these photographs.

Marta, 22 took a photograph of a man that wanders the street drunk. It affected her emotionally because she felt like she could see this man as a child whose future would be like this. She wanted to understand what had happened to make him this way, and speculates that it he did not have opportunities and turned to drugs and alcohol. She sees this same problem arising in several children in her community, and it worries her for the future. (Fig. 7) Theme discussions with participants confirmed the rise in substance use issues. They were sorry to say that previously only some adults were seen smoking, and now children of ten years old are using tobacco and marijuana. Maria, 26 offered that there used to be more respect and discipline in her community, “But not anymore. I think it's also because right now there are several parents who traveled there (the US), they leave the mother here alone in Guatemala with three or four children.”

Fig. 7.

Marta fears the children in her community may end up in the streets.

During the meeting of community leaders to discuss emerging themes, the issue of rising substance use was of great importance to elected officials. Stores selling beer and cane liquor, and providing loud music were of concern. They find that men are using all of their earnings in these activities, causing distress to wives and children. One member shared his own experience being deported three times from the United States and finding himself in heavy debt, using all of his earnings on “drink and smoke.” He was able to find his way out of his suffering, but he and the committee were unsure of how to deal with such a rapidly growing problem. One member likened it to the branch of a tree: “We remove a leaf, but after a week it already has another new leaf.”

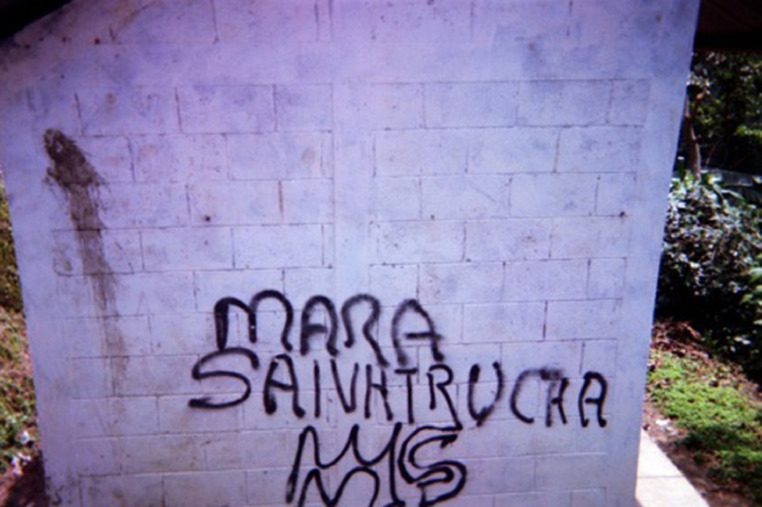

Gang activity: Younger participants, as well as the community nurse, took photographs representing a rise in gang affiliation among young people in the area. They identified the lack of opportunity and parental guidance as causes for gang activity among young adults. Several photographs show graffiti on walls and carved into hillsides depicting the names of gangs that historically had stayed confined to larger towns near the border. Fifty-year-old Ernesto, the community nurse, said he just began noticing this activity about six years ago. He said he has witnessed them fighting with one another and heard of attempts at rape of young girls, as well as participating in public drug use. The most frightening thing for him was the involvement of younger children now, “from eleven to twelve years. Much younger than people of sixteen or eighteen.” He also shared that a couple months back in a nearby community, “they raped a nine-year-old girl and killed her.”

Oscar, 25 shared a photograph of graffiti reading, Mara 13, representing the gang MS 13, which has a presence on the border near this area. He spoke about emerging territories for different factions of the groups, with a photograph he took depicting an “18″ replaced by a “13″ indicating, he said, that “MS-13 came and took it away, like it took over this wall. As seen elsewhere, Mara 18 are no longer allowed to enter because it is now the territory of Mara 13.” He fears for his own two-year-old son growing up in this environment, saying, “If we are like this now, what will happen in five or ten, fifteen years? How will our society be?” (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Oscar shares graffiti representing MS 13 in his community.

Otto, a 17-year-old young man, is afraid to walk in his own community at night, because “it would be very dangerous risking your life.” He believes this activity is the result of parents leaving children behind with no guidance. Many of the young women in the project felt it was important to document the graffiti symbols they see on walls. They recognize the meaning of the symbols and they are fearful that this dangerous activity has made it to the rural communities from the border. They are aware that these groups may pose a danger to them as young women, as Carmen, 31 recalled a story of a group of them that had “crossed out people,” and “sometimes even raped women” when they were out drinking. Twenty-two-year-old Marta, who reported she had learned about child psychology in school, believed this happened with children “who do not have a father, sometimes they just have a mom, because the father abandoned them.” She says drugs are an escape, and believes the children who become involved with these groups are doing so because of internal problems and from being without family (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Marta is afraid of the growing presence of known gangs in her community.

4. Discussion and conclusions

Focus group participants and photovoice participants spoke frequently about living in conditions of poverty that prompt and perpetuate emigration to the United States. They described the health consequences of living without adequate resources and access to healthcare, and their inability to meet basic needs. These narratives echo the struggles and reasoning for emigration in current scholarship with people in migrant sending communities of other regions in Guatemala (Brabeck et al., 2011; Hershberg and Lykes, 2013; Lykes and Sibley, 2013; Lykes et al., 2020). Conditions of poverty as described in this research have been identified by social scholars as a continued form of structural violence experienced by vulnerable populations (Benson et al., 2008). Structural violence is produced through historical and political systems that oppress sectors of the population through economic and social structures. These forms of oppression create and perpetuate disparities in areas including health and education (Farmer, 2009; Bourgois, 2001; Scheper-Hughes and Bourgois, 2004; Tyner and Inwood, 2014). Engineered disparities incite racism, gender inequality, and suppress the power and socioeconomic mobility of society's most vulnerable (Tyner and Inwood, 2014).

Studies with migrant sending communities in Guatemala have documented conditions of poverty suffered by Indigenous Maya as a catalyst for emigration to the United States (Brabeck et al., 2011; Hershberg and Lykes, 2013; Cooper and Yarbrough, 2010). Narratives among our participants centered around economic hardship and the desire to live with dignity as driving factors for international migration. This is in line with existing scholarship that cites the lack of economic resources as one of the most powerful forces driving emigration across the Southern border of the United States (Taylor et al., 2006; Hershberg and Lykes, 2013). The use of migration as a strategy to provide education for their children with remittances was a pervasive theme among the participants in this study. Previous research describes a consequence of the lack of economic opportunity that necessitates sending children to work instead of school (Cooper and Yarbrough, 2010). Many narratives addressed this reality in our study, as children from families without migrant ties cannot attend school beyond free primary education; and often those children do not attend even to that level because of their need to contribute to the household economy. Consistent with research in other migrant sending communities of Guatemala, remittances sent home from immigrant household members provides the opportunity for children's education, more secure homes, and a life with dignity (Brabeck et al., 2011; Hershberg and Lykes, 2013; Lykes and Sibley, 2013; Sánchez Ares and Lykes, 2016; Lykes et al., 2020). Migration has become a normalized strategy for building transnational families that diversify the risks and opportunities for the whole family unit across borders. A study in the Central Highlands regions with Maya Ixil women found that being left behind to migration is part of a life course for making a better future for themselves and their children (Lykes, 2010); however, being left behind was also a representation of why they leave, including living in rural poverty and lack of access to education (Lykes, 2010).

Indigenous Mayans living in the rural highlands have lived through civil war and forced to flee to increasingly rural areas to escape genocide and other forms of violence. Identity as Indigenous in Guatemala carries with it an historical experience of oppression and inequality, and those forms of violence continue now, as reported by those involved in this study. This continued oppression and violence is described by people living in these communities as the major force driving emigration from the rural highlands of Guatemala to the United States. Research across several disciplines has also characterized the conditions of poverty experienced in this region as continued structural violence against Indigenous people following the civil war (Benson et al., 2008). A study in the southern K'iche region of Guatemala described forms of violence that impact the lives of Indigenous people living in migrant sending areas, including violence in villages, with family members and neighbors forced to participate or to flee to the rural mountains (Lykes et al., 2020). Accounts of domestic violence, Indigenous oppression and poverty have marked the struggles of those left behind, as well as the basis for emigration by their family members (Lykes et al., 2020). A study with Maya Ixil women described intergenerational fear and discrimination from the civil war and genocide, and past and current human rights violations (Lykes, 2010). Indigenous women in Guatemala that endured gendered crime during the civil war are still subject to many forms of violence in their home communities (Stephen, 2019; Duffy, 2017). Gendered experiences of violence and migration in the Southern K'iche region contribute to pushing Maya women northward to the US along with a feeling of responsibility to support others left behind in communities (Sánchez Ares and Lykes, 2016). For women in the Southern K'iche region, the lack of economic and educational opportunity is a form of structural oppression (Sánchez Ares and Lykes, 2016).

As frequently as people discussed the challenges of poverty, they also described the opportunities for advancement that come from emigration to the United States. However, along with the opportunity and economic mobility that come with remittances, the impacts of losing people to emigration carry social consequences that affect individuals, families, and entire community structures. While remittances received from family members emigrated to the United States provide economic advantages, there is evidence from a national-level survey that parental emigration has negative consequences on child social-emotional development not mitigated by remittance income (Davis and Brazil, 2016). Participants also spoke about the difficult choice to make the dangerous and expensive journey to the United States, which always carries with it the possibility of having to turn back or being deported. Previous literature describes fear about the immense debt that must be incurred to migrate, though remittances have made basic living expenses possible for families in Guatemala (Lykes et al., 2020). Findings from a survey by Lykes (2020) included overwhelming debt of up to $31,000 accrued from sending family members to the United States, but also the ability to build larger homes and have purchasing power once that debt was paid (Lykes et al., 2020).

Several people discussed the changes in values and family dynamics experienced as a result of parents having emigrated away, and the void in raising children being filled by aging grandparents and other relatives. Some of these changes were described as manifesting in young peoples’ affiliation with gang activity. The dangerous influence of “maras” in this border region has been evident since before the end of the civil war in 1996; however, community participants believe that the lack of opportunity and void left by absent parents is leaving space for desperate young people searching for a sense of belonging. Children left behind recognize the reasoning and importance of their parents’ absence for many years, and of being raised by aging grandparents; however, research with Mayan adolescents suggests harmful socioemotional consequences for these children regardless of advantages gained from remittances (Lykes and Sibley, 2013; Lykes and Hershberg, 2015).

In addition to the loss of parental influence, narratives in this study described sacrifice and loss felt by those left behind by emigrated friends and family. Photographs and stories illustrated the sadness felt by those that have lost spouses and children to “el otro lado,” though they are grateful for the remittances those losses facilitate. Some described the loss of their loved ones as “the price they paid” for economic survival. Focus group accounts and some narratives described the extent to which this sadness can manifest as serious mental health struggles and even instances of suicide by those left behind to emigration. Dramatic socio-emotional effects from the loss of family to emigration is documented in transnationalism research (Lykes and Sibley, 2013; Dreby, 2006a, 2006b). Previous literature describes emotional losses due to the absence of loved ones as a significant consequence of being left behind for women. Stories of the lack of economic opportunity, abuse, poverty and alcoholism are compounded by the responsibility of having to care for households alone (Hershberg and Lykes, 2013). Psychological costs of the transnational distance between family members include disabling sadness because of prolonged separations, and visits back home once a migrant has made it to the US are impossible (Lykes et al., 2020).

One of the major changes documented by participants was the increase in substance use among both adults and young people. Qualitative research in the Central Highland regions with Maya K'iche also identified a rise in alcoholism and mental health issues as a result of being left behind to emigration to the United States (Cooper and Yarbrough, 2010). Participants attributed a cultural shift from a changing social structure as responsible for the increased use of alcohol, drugs and tobacco by community youth. Narratives also described the use of alcohol by adults as a coping mechanism for those experiencing sadness from loss, and being deported from the United States after incurring debt. Community members and leaders during discussion of results also felt that substances are used by those who cannot migrate; those individuals may be dealing with the hopelessness of their own economic immobility in a rural area with declining opportunity. Witnessing others’ ability to send children to school and build larger homes is a pressure on both men and women as providers. Narratives suggest this pressure is a motivation for community members to acquire what others in their network have been able to through family emigration. Studies with left behind populations in other areas of the world have found significant mental health impacts on those who have lost someone to emigration, including in children, and in older and middle-aged adults (Roy and Nangia, 2005; Hu et al., 2014; Liang et al., 2017; Bohme et al., 2015; Altman et al., 2018; Antman, 2010; Wilkerson et al., 2009; Paudyal and Tunprasert, 2018). Narratives in this study suggest that similar struggles are being felt by those in migrant-sending communities of rural Guatemala.

The findings in this exploratory study provide a jumping off point for understanding the experiences of and motivations for migration among those left behind in rural Guatemala. Future research should focus on specific relationship factors that may motivate or facilitate emigration away from one's community. These findings have also suggested there are mental health concerns for those left behind to emigration. Future studies should examine the mental health impacts from the loss of relationships in one's social network, as well as the possible protective effect of having remaining social ties available. Although the number of women migrating to the United States is rising, current cultural norms in these communities still favor the immigration of men; therefore, exploration of gender differences in both the motivation to emigrate, and the mental health impacts of losing social ties to emigration may be important.

5. Limitations

This research is not without significant limitations. There were only two focus groups held as part of the initial phase of this research, and each group included 20 participants. In addition, focus group recruitment relied on verbal communication from community leaders to their constituents, and only allowed for participation of those that arrived first. Unfortunately, verbal communication from leaders may not have reached all residents in the 11 included communities, and inevitably there were residents interested in participating that may not have received word of the meetings, that did not make the long trip in time, or that did arrive but could not be accommodated. However, given these limitations, moderators and observers, having lived and worked in these communities for almost two decades, took every effort to ensure the groups were representative of the larger population, and that all voices were represented in the data.

Photovoice interviews faced similar limitations. Recruitment was done through verbal communication by community leaders to constituents in 11 communities. Only the first 20 participants to arrive were included in this phase of the project. There was more interest in participation than could be accommodated due to resources and time constraints; therefore, it cannot be known for sure if participants adequately represent people across the 11 communities in this region. However, photovoice participants included both genders, varying ages, and members of differing socioeconomic statuses, therefore the authors are confident in the range of perspectives that are represented in the data.

Funding

This study was funded by travel and research grants from the UCSD Center for Latin American and Iberian Studies, Tinker Foundation, the Global Health Institute at UCSD, the International Institute at UCSD, UCSD Friends of the International Center, the Inamori Fellowship at SDSU, and the John and Mary Anderson Memorial Endowed Scholarship in Public Health from SDSU. Funders had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study was undertaken with the support of the Ministry of Health in Guatemala, the National Hospital of Guatemala, and local leadership. Special acknowledgement to the community members that facilitated and participated in this study. This study was approved by the University of California, San Diego Human Subjects Review Board. IRB#181152S.

References

- Achiume E.T. Reimagining international law for global migration: migration as decolonization? AJIL Unbound. 2017;111:142–146. [Google Scholar]