Abstract

Background

Over time, a large body of knowledge on acupoint selection patterns has accumulated. This study compared the main acupoint selection patterns between ancient and current acupuncture treatments.

Methods

Data on the 10 most frequently used acupoints were obtained from a current medical database, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and the ancient medical text Donguibogam. Network analysis was used to identify the most commonly used major points across various diseases.

Results

The most commonly used acupoints in both ancient and current acupuncture were ST36, SP6, LR3, LI4, and GV20. Acupoints CV3, CV4, CV6, CV8, and CV12 were more widely used in ancient acupuncture, while in current acupuncture, HT7, PC6, KI3, GB34, and EX-HN3 were more prevalent.

Conclusions

Ancient and current acupuncture practice had similar and distinct acupoint selection patterns. Diachronic analysis sheds light on how patterns of acupoint selection have changed.

Keywords: Acupoint, Data mining, Donguibogam, Network analysis

Abbreviations

- CDSR

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

1. Introduction

Classic medical texts have amassed empirical clinical data on acupuncture treatment.1 Over time, a vast amount of knowledge about acupoint selection patterns has accumulated and subsequently been lost.2 In 1613, the Korean royal physician Heo Jun wrote Donguibogam, which described the theory and contemporary experiences of acupuncture treatments in East Asia at that time.3 Acupuncture spread throughout Europe and other territories after Wilhelm ten Rhijne published a paper that introduced acupuncture to Europe in 1683.4 In 1979, the Food and Drug Administration allowed licensed practitioners to use acupuncture in therapeutic settings, after it had been widely embraced by Western societies.5 Over the last 20 years, i.e., in the era of evidence-based medicine, more than 3000 articles on acupuncture clinical trials have been published,6 and the clinical efficacy of acupuncture treatment for various illnesses has been proven by numerous studies.7,8

Data mining has revealed the acupoints targeted for certain conditions, such as dysmenorrhea and visceral pain.9,10 Some acupoints are used only for specific problems, whereas others like ST36, SP6, LI4, and LR3 are used for a variety of diseases.11 Practitioners participating in a virtual diagnostic procedure typically recommended needling these major acupoints.12 Network analysis also revealed that the major acupoints tended to have a high degree of centrality and have been used frequently in diverse pain conditions.13 Needling major acupoints has various neurological effects, such as descending analgesia and central regulatory effects.14,15 Needling of the main acupoints has been advocated to increase the overall efficacy of acupuncture, based on Western notions of anatomy and physiology.15 However, scant research has addressed the differences in acupoints selection patterns between ancient and current acupuncture treatment.

Therefore, this study compared acupoint selection patterns between ancient literature and current acupuncture treatments. We collected acupoint data from Donguibogam, a famous, classical Korean medical text, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), which is a contemporary medical database containing studies on acupoints.

2. Methods

2.1. Data extraction and processing

Donguibogam and CDSR contain data on acupoint selection. The “Acupuncture and Moxibustion Methods” of all subchapters of Donguibogam contained acupoints combinations for each disorders. The data source was gathered from the medical classics database website (https://mediclassics.kr/books/8). The names of acupoints from historical medical texts in Chinese were renamed with Standard acupuncture nomenclature. Criteria for CDSR studies have previously been detailed in full. The Acusynth database comprised acupoint combinations for 30 disorders from 30 CDSRs.12,16, 17, 18 Studies have described the major acupoint selection patterns in both ancient and modern practice.3,17

2.2. Data analysis

The acupuncture treatments described in Donguibogam used 471 acupoint combinations, while those in the articles in the CDSR used 413 combinations. The 10 most frequently used acupoints in Donguibogam and the CDSR studies were identified. We determined the most commonly used sets of acupoints for different diseases.

In addition, network analysis was conducted to uncover hubs of acupoints combinations both in Donguibogam and CDSR using Gephi (an open source software for graph and network analysis, version 0.9.2, http://gephi.org). The degree and betweenness centrality of each acupoint were calculated and visualized using Event Graph Layout. The position of the nodes on the Y-axis was determined using a rank order based on the number of degrees.

3. Results

3.1. Common and distinct major acupoints between ancient and current acupuncture treatments

Of the 294 acupoints in Donguibogam, 82 were used more than five times, while 106 of 262 acupoints were used more than five times in articles in the CDSR. We determined the top 10 most frequently used acupoints for both data sources (Table 1).

Table 1.

The 10 most frequently used acupoints in ancient and current acupuncture.

| Rank | Donguibogam | Number of uses (percentage) | Rank | CDSR | Number of uses (percentage) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ST36 | 53 (11.3%) | 1 | SP6 | 176 (42.6%) | |

| 2 | LI4 | 37 (7.9%) | 2 | ST36 | 149 (36.1%) | |

| 3 | CV6 | 35 (7.4%) | 3 | LI4 | 137 (33.2%) | |

| 4 | CV12 | 29 (6.2%) | 4 | LR3 | 137 (33.2%) | |

| 5 | GV20 | 27 (5.7%) | 5 | GV20 | 134 (32.4%) | |

| 6 | CV4 | 25 (5.3%) | 6 | PC6 | 118 (28.6%) | |

| 7 | SP6 | 24 (5.1%) | 7 | HT7 | 73 (17.7%) | |

| 8 | CV3 | 21 (4.5%) | 8 | EX-HN3 | 63 (15.3%) | |

| 9 | LR3 | 21 (4.5%) | 9 | GB34 | 62 (15.0%) | |

| 10 | CV8 | 20 (4.2%) | 10 | KI3 | 59 (14.3%) | |

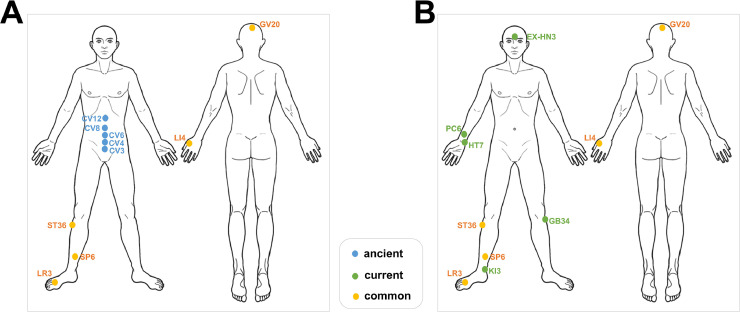

The most commonly used major acupoints in both Donguibogam and CDSR articles were ST36 (n = 53, 11.3% and n = 149, 36.1%, respectively), SP6 (n = 24, 5.1% and n = 176, 42.6%), LR3 (n = 21, 4.5% and n = 137, 33.2%), LI4 (n = 37, 7.9% and n = 137, 33.2%), and GV20 (n = 27, 5.7% and n = 134, 32.4%). Acupoints CV6 (n = 35, 7.4%), CV12 (n = 29, 6.2%), CV4 (n = 25, 5.3%), CV3 (n = 21, 4.5%), and CV8 (n = 20, 4.2%) were used frequently only in Donguibogam, whereas PC6 (n = 118, 28.6%), HT7 (n = 73, 17.7%), EX-HN3 (n = 63, 15.3%), GB34 (n = 62, 15.0%), and KI3 (n = 59, 14.3%) were used frequently only in CDSR articles (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of major acupoints between ancient and current acupuncture treatments. ST36, SP6, LR3, LI4, and GV20 were the most commonly used acupoints in both ancient and current acupuncture (in yellow). A) In traditional acupuncture, acupoints CV3, CV4, CV6, CV8, and CV12 were used more frequently (shown in blue). B) In current acupuncture, acupoints HT7, PC6, KI3, GB34, and EX-HN3 are used more frequently (shown in green). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

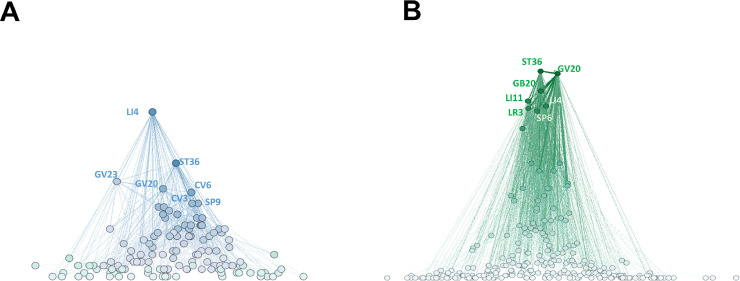

3.2. Network analysis of acupoints used in ancient and current acupuncture treatments

We identified important acupoints for acupuncture treatment of a diverse range of illnesses through network analysis of acupoint selection patterns (Table 2). Network analysis revealed that 257 nodes and 2478 edges were found in Donguibogam, and 266 nodes and 891 edges were observed in CDSR articles. Acupoints LI4 (Degree = 48), ST36 (34), GV23 (29), GV20 (27), and CV6 (26) had the most links among all acupoints in Donguibogam, while ST36 (84), GV20 (83), GB20 (76), LI11 (72), and LI4 (70) had the most links among all acupoints in CDSR articles (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

The hub acupoints from network analysis in ancient and current acupuncture.

| Rank | Donguibogam | Degree | Betweenness centrality | Rank | CDSR | Degree | Betweenness centrality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LI4 | 48 | 6693 | 1 | ST36 | 84 | 4746 | |

| 2 | ST36 | 34 | 3680 | 2 | GV20 | 83 | 4641 | |

| 3 | GV23 | 29 | 3282 | 3 | GB20 | 76 | 4849 | |

| 4 | GV20 | 27 | 3331 | 4 | LI11 | 72 | 4661 | |

| 5 | CV6 | 26 | 1557 | 5 | LI4 | 70 | 2401 | |

| 6 | CV3 | 23 | 1936 | 6 | LR3 | 69 | 2362 | |

| 7 | SP9 | 23 | 1261 | 7 | SP6 | 68 | 1878 | |

| 8 | GV16 | 22 | 1292 | 8 | BL23 | 61 | 2110 | |

| 9 | GV26 | 22 | 1812 | 9 | CV4 | 47 | 1012 | |

| 10 | CV22 | 21 | 1433 | 10 | GV24 | 47 | 1604 | |

Fig. 2.

Network analysis of acupuncture point selection in ancient and current acupuncture treatments. A) In ancient acupuncture, acupoints LI4, ST36, GV23, GV20, and CV6 had the most connections (shown in blue). B) In current acupuncture, acupoints ST36, GV20, GB20, LI11, and LI4 had the most connections (shown in green). The network analysis was done using Gephi. The position of the nodes on the Y-axis was determined using a rank order based on the number of degrees. The color of node was visualized based on the number of degrees. Acupoints with greater degree were darker, and the weight was illustrated by the width of the edges. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

LI4, ST36, and GV20 were shown to be common network hubs in both ancient and modern acupuncture treatments in the network analysis. In ancient acupuncture treatment, GV23, CV6, and CV3 were unique network hubs, whereas in modern acupuncture treatment, GB20 and LI11 were unique network hubs.

4. Discussion

By comparing the most frequently used acupoints between ancient and current acupuncture treatments, we discovered shared acupoints between the two eras (ST36, SP6, LR3, LI4, and GV20). Thus, these frequently used acupoints can be regarded as the major ones targeted by acupuncture practitioners. These findings were in line with prior findings that acupoints such as ST36, SP6, LI4, and LR3 are commonly used across a variety of disorders.11,12 These major acupoints, the use of which can be traced back 400 years, differ in terms of indications.13 Most major acupoints are distal to the knees and elbows, and produce an intense deqi sensation when needled. Given their locations and deqi sensations, the needling of these major acupoints may promote descending analgesia and central regulation of pain.15

In this study, acupoints CV3, CV4, CV6, CV8, and CV12 (in the belly) were found to be used more commonly in ancient acupuncture therapy. In Donguibogam, these acupoints were considered as the foundation of the five viscera and six intestines, and the source of the life force (qi). Accordingly, these acupoints were commonly the targets of moxibustion in ancient times. In comparison, HT7, PC6, KI3, GB34, and EX-HN3 are more commonly used in contemporary acupuncture. These acupoints, particularly HT7, PC6, and KI3, are the most important for emotional regulation and treating visceral dysfunction, and share many characteristics with other acupoints.16 The changes in acupuncture practice between ancient and modern times can be attributed to the philosophical and empirical differences between the two periods. For example, there have been changes in the most common diseases (e.g., qi deficiency may have been more common in ancient times) and clinical approaches (e.g., moxibustion is now used more often than acupuncture for acupoints on the CV meridian).

One limitation of this study was our comparison of only two data sources. However, around 400 years ago, Donguibogam was the standard for acupuncture practice. The acupoint patterns described therein can thus be considered equivalent to clinical practice guidelines, where the book was written by a royal physician (Heo Jun) based on the most up-to-date findings published in East Asia at that time. We did, however, only look at one sample medical classic. It will be necessary to combine acupoints from diverse data sources throughout various time windows. The Acusynth database,17 which describes the frequency of use of acupoints for 30 diseases based on CDSR studies, has the highest level of empirical evidence, and well-represents current trends in clinical acupuncture. Donguibogam and CDSR both cover a wide spectrum of disorders and the amount of data provided on acupoint selection is comparable between them. Therefore, the information on important acupoints provided by these data sources is useful for comparing ancient and modern acupuncture treatments. In conclusion, this study highlighted the similarities and differences in acupoint selection patterns between ancient literature and current acupuncture treatment. Future study is required to identify reasons for the changes in practice; we believe that further diachronic analysis will provide more information on how acupoint selection has changed over time.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yeonjoo Yoo: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Yeonhee Ryu: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. In-Seon Lee: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Younbyoung Chae: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by 2021 Undergraduate Research Program of Kyung Hee University, Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (KSN1812181) and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (No. 2021R1F1A1046705 & 2021R1F1A1050116).

Ethical statement

Not applicable.

Data availability

The authors can provide the data upon reasonable request.

Contributor Information

In-Seon Lee, Email: inseon.lee@khu.ac.kr.

Younbyoung Chae, Email: ybchae@khu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Ma K.W. Acupuncture: its place in the history of Chinese medicine. Acupunct Med. 2000;18(2):88–99. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basser S. Acupuncture: a history. Sci Rev Altern Med. 1999;3:34–41. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee T., Jung W.M., Lee I.S., Lee Y.S., Lee H., Park H.J., et al. Data mining of acupoint characteristics from the classical medical text: DongUiBoGam of Korean Medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/329563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bivins R. The needle and the lancet: acupuncture in Britain, 1683-2000. Acupunct Med. 2001;19(1):2–14. doi: 10.1136/aim.19.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammerschlag R. Funding of acupuncture research by the national institutes of health: a brief history. Clin Acupunct Oriental Med. 2000;1:133–138. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeon S.H., Lee I.S., Lee H., Chae Y. A bibliometric analysis of acupuncture research trends in clinical trials. Kor J Acu. 2019;36(4):281–291. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee I.S., Lee H., Chen Y.H., Chae Y. Bibliometric analysis of research assessing the use of acupuncture for pain treatment over the past 20 years. J Pain Res. 2020;13:367–376. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S235047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vickers A.J., Cronin A.M., Maschino A.C., Lewith G., MacPherson H., Foster N.E., et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(19):1444–1453. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee I.S., Cheon S., Park J.Y. Central and peripheral mechanism of acupuncture analgesia on visceral pain: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/1304152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu S., Yang J., Ren Y., Chen L., Liang F., Hu Y. Characteristics of acupoints selection of moxibustion for primary dysmenorrhea based on data mining technology. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2015;35(8):845–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang Y.C., Lee I.S., Ryu Y., Lee M.S., Chae Y. Exploring traditional acupuncture point selection patterns for pain control: data mining of randomised controlled clinical trials. Acupunct Med. 2020:184–191. doi: 10.1177/0964528420926173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee Y.S., Ryu Y., Yoon D.E., Kim C.H., Hong G., Hwang Y.C., et al. Commonality and specificity of acupuncture point selections. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/2948292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee I.S., Chae Y. Identification of major traditional acupuncture points for pain control using network analysis. Acupunct Med. 2021;39(5):553–554. doi: 10.1177/0964528420971309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chae Y., Chang D.S., Lee S.H., Jung W.M., Lee I.S., Jackson S., et al. Inserting needles into the body: a meta-analysis of brain activity associated with acupuncture needle stimulation. J Pain. 2013;14(3):215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White A. Elsevier; New York: 2018. An Introduction to Western Medical Acupuncture. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi D.H., Lee S.Y., Lee I.S., Ryu Y., Chae Y. Characteristics of Source acupoints: data mining of clinical trials database. Kor J Acu. 2021;28(2):100–109. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang Y.C., Lee I.S., Ryu Y., Lee Y.S., Chae Y. Identification of acupoint indication from reverse inference: data mining of randomized controlled clinical trials. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9) doi: 10.3390/jcm9093027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee S., Ryu Y., Park H.J., Lee I.S., Chae Y. Characteristics of five-phase acupoints from data mining of randomized controlled clinical trials followed by multidimensional scaling. Integr Med Res. 2022;11(2) doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2021.100829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors can provide the data upon reasonable request.