Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this evaluation is to understand whether introducing stabilisation rooms equipped with pulse oximetry and oxygen systems to frontline health facilities in Ikorodu, Lagos State, alongside healthcare worker (HCW) training improves the quality of care for children with pneumonia aged 0–59 months. We will explore to what extent, how, for whom and in what contexts the intervention works.

Methods and analysis

Quasi-experimental time-series impact evaluation with embedded mixed-methods process and economic evaluation. Setting: seven government primary care facilities, seven private health facilities, two government secondary care facilities. Target population: children aged 0–59 months with clinically diagnosed pneumonia and/or suspected or confirmed COVID-19. Intervention: ‘stabilisation rooms’ within participating primary care facilities in Ikorodu local government area, designed to allow for short-term oxygen delivery for children with hypoxaemia prior to transfer to hospital, alongside HCW training on integrated management of childhood illness, pulse oximetry and oxygen therapy, immunisation and nutrition. Secondary facilities will also receive training and equipment for oxygen and pulse oximetry to ensure minimum standard of care is available for referred children. Primary outcome: correct management of hypoxaemic pneumonia including administration of oxygen therapy, referral and presentation to hospital. Secondary outcome: 14-day pneumonia case fatality rate. Evaluation period: August 2020 to September 2022.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval from University of Ibadan, Lagos State and University College London. Ongoing engagement with government and other key stakeholders during the project. Local dissemination events will be held with the State Ministry of Health at the end of the project (December 2022). We will publish the main impact results, process evaluation and economic evaluation results as open-access academic publications in international journals.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12621001071819; Registered on the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry.

Keywords: COVID-19, education & training (see medical education & training), health economics, health services administration & management, paediatric A&E and ambulatory care, paediatric infectious disease & immunisation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

INSPIRING-Lagos is a multisite study involving a range of public and private primary care facilities in urban Nigeria that will provide robust data on the impact of introducing pulse oximetry and oxygen-equipped stabilisation rooms to primary care settings.

The impact evaluation will involve time-series analysis of quantitative data on pulse oximetry and oxygen practices, providing robust evidence of impact.

We use qualitative data from healthcare workers and community members to understand perceptions and experience with pulse oximetry and oxygen therapy.

We will also conduct a theory-informed mixed-methods process evaluation to understand how the intervention worked, for whom, and in what contexts, and an economic evaluation to estimate cost-effectiveness in the urban Nigerian context.

The main limitation is on the strength of our impact data due to lack of randomly selected controls and unpredictable influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on sample size and participant characteristics.

Introduction

In 2019, Nigeria ranked as the country with the highest under-5 mortality rate (117.2 per 1000 live births).1 Pneumonia is the leading cause of child death in Nigeria and globally, causing approximately 134 000 and 800 000 deaths in 2017, respectively.1 The under-5 mortality in Lagos State is around half the national average, at 50 per 1000 live births, representing an urban population with lower relative poverty levels (1.1% live in severe poverty).2

From November 2018 to June 2019, we conducted a situational analysis of paediatric pneumonia in Lagos and Jigawa states of Nigeria, to inform the design of an intervention programme to reduce paediatric mortality. We found that while protective and preventive factors, such as vaccine coverage and clean cooking fuel, were high in Lagos, care-seeking and health facility service readiness were poor.3–6 Therefore, taking an approach that targets improved quality of care for pneumonia diagnosis and treatment could achieve mortality impact. In the context of the emerging COVID-19 pandemic, in consultation with local stakeholders, we decided to focus on healthcare worker (HCW) capacity-building and enhancement of pulse oximetry and oxygen systems.

Pulse oximetry is a standard of care for identifying hypoxaemia (low blood oxygen levels) and guiding oxygen therapy in hospitalised patients. The WHO’s Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) guidelines also recommend pulse oximetry for identifying severely ill patients with hypoxaemia in primary care settings, requiring referral to hospital.7–9 Despite their potential for reducing mortality, pulse oximeters are rarely available in frontline facilities in low-income and middle-income countries.6 10–12 Indeed, our survey of 58 Lagos health facilities in 2020 found pulse oximeters in none of the primary health facilities, 56% (15/27) of private health facilities and exclusively on the paediatric ward of three secondary health facilities.13

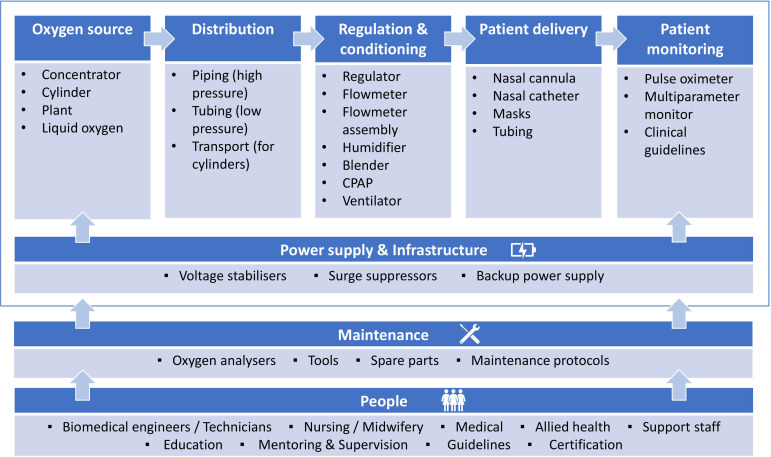

Oxygen therapy is required for stabilisation and treatment of severely ill patients with conditions such as COVID-19, pneumonia and sepsis and is listed by the WHO as an Essential Medicine.14–16 Effective oxygen systems require (1) reliable oxygen supply and delivery devices, (2) rational use by skilled HCWs guided by pulse oximetry and (3) supportive infrastructure, management and biomedical support (eg, power supply, procurement and planning, skilled technicians with tools and spare parts; figure 1).17 Our situational analysis revealed opportunities to improve patient access to oxygen through improved equipment selection and installation, repair and maintenance, and training and support for HCWs and technicians.6 18 19 Subsequently, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of hospital oxygen systems and exacerbated existing deficiencies.8 20–23

Figure 1.

Hospital oxygen systems require a range of medical devices and other equipment and supplies (Adapted from WHO-UNICEF Technical Specifications and Guidance for Oxygen Therapy Devices). CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure.

The Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health has demonstrated its commitment to improving paediatric survival and oxygen access, with updated medicine, equipment and treatment guidelines.24–28 Pulse oximetry and oxygen therapy were identified as priority areas for intervention in the context of Lagos by both local and international stakeholders.5 However, there is a need for evidence on the impact and cost-effectiveness of these interventions when delivered routinely in frontline care, especially understanding the contextual mechanisms within government and private facilities, to facilitate effective adoption at scale.

This protocol outlines the mixed-methods evaluation plan for integrated HCW training, pulse oximetry and oxygen implementation in government and private health facilities in Lagos.

Methods and analysis

Research questions and study design

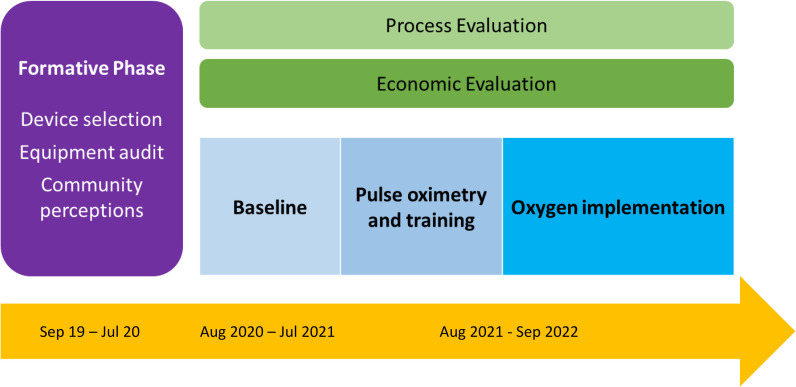

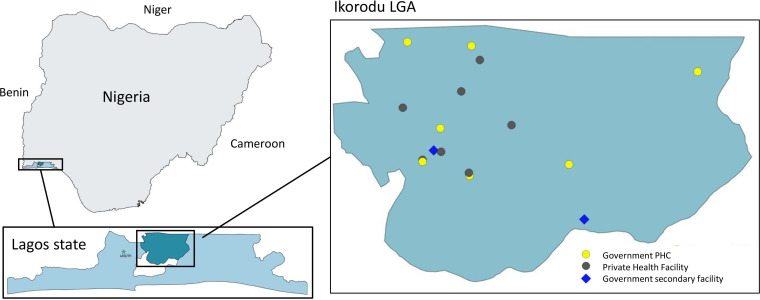

The overall aim of this evaluation is to understand whether introducing pulse oximetry and oxygen systems to health facilities in Lagos, alongside HCW training, improves the quality of care for children with pneumonia aged 0–59 months. We will explore to what extent, how, for whom and in what contexts this intervention package works. This aim will be addressed through specific research questions (table 1) using a quasiexperimental time-series impact evaluation with embedded mixed-methods process and economic evaluation. The study period will be August 2020—September 2022 and will be conducted in Ikorodu local government area (LGA), Lagos State (figure 2).

Table 1.

Evaluation domains and key research questions

| Domain | Research question |

| Impact |

|

| Process |

|

| Economic |

|

LGA, local government area.

Figure 2.

Overall INSPIRING Lagos evaluation design.

The impact evaluation will estimate the intervention effect on hypoxaemic pneumonia management and 14-day mortality among children aged 0–59 months, using a time-series approach. We anticipate a baseline period lasting between 2 months and 12 months, depending on the facility, and that intervention components may be implemented at different time points (eg, IMCI training occurring before oxygen installation).

The process evaluation will use a theory-informed mixed-methods study design, with qualitative data from HCWs and caregivers, and quantitative monitoring and evaluation data to understand what worked, how, for whom and in what contexts.

The economic evaluation will involve a time-motion study, together with analysis of administrative financial data and caregiver surveys to assess the economic cost of the intervention from the provider (Ministry of Health) and consumer (patient/caregiver) perspectives. Together with the impact evaluation data, we will assess the cost-effectiveness and affordability of the intervention.

Setting

A summary of Ikorodu LGA is presented in table 2. We will be working in both government and private healthcare facilities, including 7 of the 28 government primary health centres (PHCs), 7 private health facilities and both government secondary care facilities in Ikorodu LGA (figure 3). There are no tertiary facilities in Ikorodu LGA.

Table 2.

Summary characteristics of Ikorodu LGA

| Characteristic | Number |

| Estimated population | 890 000 |

| Estimated under-5 population | 160 000 |

| Under-5 mortality ratio | 50 per 1000 live births (Lagos State) |

| Government primary care facilities | 28 |

| Private primary care facilities | 148 |

| Government secondary facilities | 2 |

| Private secondary facilities | 1 |

Source: Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2016–2017, Survey Findings Report. Abuja, Nigeria: National Bureau of Statistics and United Nations Children’s Fund, 2017. Facility number obtained from Ministry of Health in November 2019.

LGA, local government area.

Figure 3.

Map of Nigeria, Lagos State, and Ikorodu LGA. LGA, local government area; PHC, primary health centre.

Selection

We will cover the whole LGA geographically but will not include all facilities in the study. Save the Children, in collaboration with LGA leaders, purposively selected seven government PHCs as ‘flagship’ facilities for the programme, targeting government facilities that have greatest need (Annex 1). Each PHC was then matched based on geographical location to a private health facility, which had consented to take part in the programme during the formative phase and provides care for children under-5 years of age.13 We also included the two government secondary care facilities.

Population

The intervention and impact evaluation will focus on children aged 0–59 months attending the outpatient areas of participating facilities for an acute illness and who are diagnosed with clinical pneumonia defined according to the 2014 WHO IMCI guidelines and/or suspected or confirmed COVID-19 (table 3).29 However, the intervention will be available to benefit all children and adults receiving care from participating facilities.

Table 3.

Clinical case definitions of acute lower respiratory infections, and recommended primary care treatment according to WHO IMCI guidelines

| Category | Signs and symptoms | Treatment |

| Pneumonia | Cough and/or difficulty breathing AND Fast breathing for age AND/OR Chest indrawing |

Home treatment with oral antibiotics |

| Severe pneumonia | Cough and/or difficulty breathing AND General danger sign AND/OR Hypoxaemia |

Hospital inpatient treatment with IV antibiotics (and oxygen for those with SpO2 <90%) |

| Suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 | Clinician diagnosis AND/OR RT-PCR positive test |

Not specifically addressed in IMCI. Local guidelines adapted from WHO guidelines.41 |

IMCI, Integrated Management of Childhood Illness.

Intervention

Stabilisation rooms

The project will establish ‘stabilisation rooms’ within the outpatient areas of participating primary facilities, designed to allow for short-term oxygen delivery for children with hypoxaemia prior to transfer to hospital (or admission to the ward). These stabilisation rooms are intended to support both short-term COVID-19 and long-term paediatric pneumonia care needs and will consist of the following intervention components:

Pulse oximeters, equipped with both paediatric and adult re-usable probes.

Medical oxygen supply delivered through newly installed oxygen concentrators powered from mains supply, generators and/or solar power.

Clinical guidelines, job aids and clinical training.

Secondary health facilities that admit children will also be supported with pulse oximeters and oxygen concentrators for use on the wards to support safe care of patients referred for inpatient care. The intervention does not include portable oxygen for transport or direct referral support.

Selection of devices was based on national and international technical guidance and experience with similar devices in Nigeria and elsewhere.21 22 25 To facilitate a substudy comparing the usability and acceptability of two oximeters, facilities will be randomly allocated, with a 1:1 ratio using a random number generator, to receive either Lifebox (Acare Technology, New Taipei City, Taiwan) or Masimo RadG (Masimo, Irvine California) oximeters.

We anticipate a 1–6-month delay in receiving both oxygen and oximetry equipment, given the global supply chain challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic; therefore, the evaluation design will need to be adaptive and flexible. The intervention will be delivered by Save the Children Nigeria, with technical support provided by private non-profit oxygen for life Initiative (OLI), working closely with local government.

Training and supervision

The stabilisation rooms will be implemented alongside broader capacity-building activities targeting primary care HCW practices (preventive and curative). This will include training on WHO’s IMCI guidelines, pulse oximetry and oxygen therapy, immunisation and nutrition (table 4). This includes guidance to conduct pulse oximetry on all acutely unwell children, provide oxygen using nasal prongs to those with low blood oxygen levels (SpO2 <90%), prescribe appropriate antibiotics and arrange transfer to an admission facility for those requiring inpatient care (typically by private vehicle) as per WHO IMCI guidelines.

Table 4.

Summary of training activities

| Training | Location and duration | Target |

| IMCI | In primary facilities, 6 days. | Community health extension worker, community health officers, nurses, |

| Pulse oximetry and oxygen therapy | In primary and secondary care facilities, 3 days. | Community health extension worker, community health officers, nurses, midwives, doctors,±technicians |

| Immunisation ‘Reaching Every District’ | In primary care facilities, 2–3 days. | Vaccinators, immunisation focal persons, facility officer in charge |

| IYCF, CMAM | In training centre and primary care facilities, 3 days. Repeated after 1 year for new staff. |

Community health extension worker, community health officers, nurses, nutrition focal person |

CMAM, Community Management of Acute Malnutrition; IMCI, Integrated Management of Childhood Illness; IYCF, Nutrition—Infant and Young Child Feeding.

All training activities will be coordinated by Save the Children Nigeria using the ADDIE model (A=analysis, D=design, D=develop training materials, I=implement/delivery and E=evaluation). Save the Children Nigeria will conduct a Training Needs Assessments using their ‘Task Analysis’ tools, assessing a HCW’s actual skills and knowledge compared with the skills and knowledge they are meant to have based on their job descriptions. The training will be adapted from existing standard training packages to the local context with the assistance of local facilitators selected from the State Ministry of Health (SMOH) and partners (eg, WHO, UNICEF, OLI).

Local facilitators who lead the training will also act as coaches, mentors and supervisors after the training has been completed and the participants have been deployed. They will visit each facility every 4–6 weeks and maintain interim contact using mobile phone-based group messaging. The Ikorodu LGA health team will also contribute to supervision through existing immunisation supportive supervision arrangements.

Control

The control period—before the interventions are delivered in study facilities—will consist of routine clinic operation with existing material resources.

Impact evaluation

Outcome

The primary outcome is the correct management of hypoxaemic pneumonia among children aged 0–59 months who present to a participating health facility. ‘Correct management’ is defined as the child receiving oxygen treatment and being referred to and subsequently attending hospital (all three criteria need to be met). Clinical pneumonia is defined according to the 2014 IMCI guidelines (table 3).9 29 COVID-19 is defined as either PCR-test confirmed or based on a clinical diagnosis according to local guidelines. At the time of developing this protocol, we knew little about the epidemiology or clinical features of COVID-19 in children and, while many presented with signs of respiratory infection, there had been reports of ‘silent/happy hypoxia’. Therefore, we elected to include any children with suspected COVID-19 infection irrespective of respiratory signs. Oxygen treatment and referral decision will be recorded at recruitment, and hospital attendance, treatment and deaths will be confirmed by telephone interview at 2 weeks and via medical records where available. Secondary outcomes include 14-day mortality and process outcomes (see the Process evaluation section).

Data collection

Study employed clinical data collectors will be responsible for recruitment and data collection in participating facilities. Each data collector will be responsible for one to two clinics, visiting each clinic at scheduled times each week according to a monthly roster that ensures we recruit at different times and days in each facility to maximise representativeness of data. During scheduled clinic visits, data collectors will screen all children under-5 who present to the clinic with an acute infection for eligibility before they have been routinely assessed by the HCW. This assessment involves a directed history and physical examination to identify clinical features of pneumonia and COVID-19, including pulse oximetry and auscultation (using standard and digital stethoscopes). After identifying those who meet eligibility criteria, data collectors will obtain consent, complete an additional medical and socioeconomic questionnaire and arrange for phone follow-up. Following the HCW consultation, data collectors will enquire about caregiver intentions for onward care and extract routine clinical data from the HCW’s clinical notes (including diagnosis, treatment and referral decision, vital signs and clinical observations). The data collector will inform the HCW if they find any signs that meet referral criteria and document whether this results in any change in patient management.

Data collectors will conduct follow-up interviews 14 days after recruitment, by telephone. The follow-up interview will confirm survival of the child and record details of any onward care and oxygen received after their initial presentation, the cost of care and treatment adherence. Where a child has died, the interview will be stopped and the study staff will attempt to conduct a verbal autopsy (VA), using the COVID-19-adapted WHO 2016 VA tool and additional social autopsy questions around care-seeking.30

Data collection will be conducted between August 2020 and September 2022 (24 months), and exact timing of baseline and intervention periods will depend on intervention implementation at different facilities.

Sample size

We had originally calculated a sample size based on the case fatality rate (CFR) as a primary outcome, assuming a baseline CFR of 4% and 1920 eligible children recruited. In this scenario, we had 72% power to detect a 50% reduction in CFR31 but recognised this was uncertain given the COVID-19 context and lack of baseline data. We, therefore, reviewed the data from August 2020 to January 2021 and found lower than expected CFR making this scenario unfeasible. We used this data to update the sample size for the new primary outcome of ‘correct management of hypoxaemic pneumonia cases’, based on using a pre–post analysis. Using the following numbers extracted from the 6-month baseline data, we will be able to detect a minimum 15% increase in correct management: 75 children with completed follow-up per month; 24-month data collection period; intracluster correlation 0.05; 10% hypoxaemic; 5% correctly managed preintervention. This means we should be able to detect a significant difference if the intervention results in ≥20% of hypoxaemic children being correctly managed.

Analysis

The primary analysis will be a time-series analysis, using a change point model. In this analysis, an intervention time point is not prespecified; therefore, given the challenges we will face in defining clean ‘pre’ and ‘post’ intervention periods, this method allows more flexibility and fewer assumptions than interrupted time-series analysis. We will be able to assess whether care has improved and identify the most likely time for the change point, which we can link to the intervention and other key events.32

Sensitivity analyses will include: stratification by age-group and sex of the child; stratification by clinic type and stratification by pneumonia severity classification. We will account for clustering of outcomes at clinic level in analyses and explore the role of intervention dose-effects.

Secondary analyses will include: assessing impact on 14-day mortality; describing the epidemiology of hypoxaemia among children; predictive modelling of pneumonia mortality and hypoxaemia; analysis of changes in clinical attendance rates, referral decision-making and referral attendance over time; description of suspected COVID-19 epidemiology.

Process evaluation

Process data will cover the context, intervention delivery (including fidelity and reach) and mechanisms of impact (Annex 2).33

Context

We will add to the contextual information from our situational analysis, with particular view on how COVID-19 alters health structures, community perceptions and care-seeking behaviours.

Health system

A biomedical engineer will conduct annual oxygen and pulse oximetry equipment checks, including the location, use, functionality and maintenance. A baseline assessment of existing equipment was conducted during the formative research phase (January–August 2020) and the full methods reported.13

To understand the evolving health facility context, we will periodically measure: essential medicine stock-outs of tracer drugs (eg, AmoxDT); availability of PPE and IPC materials; staff turnover, balance of cadres, experience and gender. These data will be collected quarterly, by phone by study staff or if circumstances permit, during quarterly supervisory visits to the clinics.

Community

To provide an understanding of the community context in which the intervention is being implemented, we will collect data on the sociodemographic characteristics of caregivers and children and their care-seeking patterns.

Intervention delivery

Intervention delivery will be evaluated according to fidelity to the original design of the intervention, noting adaptations, reach and the change in knowledge of participants.

Clinical practices

The clinical data collectors will conduct case note reviews at each facility, on a quarterly basis, to determine the standard of IMCI assessment, diagnosis and treatment decision-making. The data collector will go back in time from the date of data collection in the patient registers/case notes until the prespecified target number of cases have been identified (eg, target for PHCs is 50 eligible children).

Intervention fidelity

The training delivered by Save the Children Nigeria will be independently observed by a member of the research staff, who will record whether the training was delivered as intended. On-going supervision and functioning of pulse oximeters will be recorded using routine supervision logs and work plans. Data collectors and HCWs will be asked to keep diaries to collect their everyday perceptions and experiences in relation to the intervention.34

Reach

Intervention reach will be assessed by tracking the coverage of trained staff and functional equipment throughout the duration of the project. These data will be routinely collected quarterly, by phone by study staff or if circumstances permit, during quarterly supervisory visits to the clinics.

Mechanisms of impact

The mechanism of impact will be measured from the health provider and community perspectives.

Health provider

Data collected during recruitment will provide data on diagnoses made, treatments given and referral decision-making. We will extract data from a subset of these case notes to check for compliance to guidelines and track this over time.

We will conduct focus group discussions (FGDs) and in-depth interviews (IDIs) with HCWs to understand their perceptions about pulse oximetry and oxygen therapy and understand changes over time (Annex 3). FGD/IDIs will be held with the healthcare providers before the intervention has been implemented, and then at select time periods throughout the study period. IDIs will be organised around story completion activities, a method that is designed to create safe spaces for participants to reveal processes of sense making and things about themselves that they may otherwise feel uncomfortable doing in group or public situations (such as disclosure of sensitive issues).35

Community

Our situational analysis, alongside studies from other contexts, has revealed considerable misconceptions about oxygen among HCWs and patients/families. We will conduct interviews and FGDs with caregivers, to understand perceptions about oxygen and behavioural responses to the intervention (Annex 4,5). We will triangulate this qualitative data with quantitative data collected in the follow-up surveys to understand changes in care-seeking behaviours following the intervention. Specific indicators include: the delay in deciding to first seek care; the location of first seeking care; the decision to attend a referral and delay in attending a referral. In addition, data from narratives taken during verbal autopsies will be used to explore how care pathways differed between those children who survived and who died from an acute infection.36

Analysis

We will report findings descriptively. Where appropriate, data will be stratified by healthcare provider cadre and facility type and differences evaluated with Χ2 and t-tests.

FGD and interview data will be analysed using a pragmatic framework approach that blends inductive and deductive analytical approaches.37 Predefined and agreed themes based on the topic guide will guide an initial analysis, with any emerging themes coded during the analysis. All qualitative data will be coded and analysed by two researchers, and interpretation and conclusions will be shared and discussed with the core project team.

Economic evaluation

We will conduct a prospective costing of the interventions, which will include financial (capital set-up and recurrent expenditures) and economic costs (time-motion studies),38–40 based on the provider (Ministry of Health) perspective. We will also consider the household perspective, via surveys of financial and time (opportunity) costs to caregivers.

Excel budget tool

We will use the accounts of the implementing partner to determine actual capital and recurrent expenditure on the interventions, including equipment and maintenance, training, mentoring and supportive supervision, travel and allowances and salaries of project staff, using an ingredients approach.38 All costs required to replicate the intervention will be included. Cost data from the accounts will be extracted to an Excel template adapted from one used by Batura et al for costing complex public health interventions.38

Timesheet and observation checklist

We will conduct a time-use study of HCWs managing childhood pneumonia cases at primary health facilities to determine how much time is spent by HCWs on the use of pulse oximetry and oxygen per case. This study will be done at government PHCs as our economic evaluation is focused on the Ministry of Health provider perspective. We will collect data on time-use via a researcher observed time-motion study (if deemed safe to do so) of 30 pneumonia and 30 severe pneumonia cases (Annex 6).40 For both the timesheet and observational studies, we will time: communication, documentation, vital signs assessment, physical examination, use of pulse oximetry, medication given, oxygen setup and adjustment, feeding, suctioning, medication administration. We will use time use data and the HCW cadre to estimate the healthcare provider cost of delivering pneumonia care.

Caregivers’ perspectives

We will determine the cost to patients during the follow-up interviews with caregivers. In a random subsample of 100 caregivers, we will administer a longer questionnaire, which includes: the time taken to seek care as well as the resources spent on travel, childcare, opportunity costs of business or other activities forgone (estimated by potential lost earnings or opportunities). We will monitor the costs of essential items every quarter using a basic market survey (eg, fuel, food supplies) to monitor the wider economic impact on household costs related to changing oil prices and COVID-19.

Data management

We will collect data in several formats: audio; paper forms and notes; electronic data using a custom-built CommCare app; teleconference recordings and text messages; paper consent forms. Data collection, storage and processing will be compliant with the European Union General Data Protection Regulations. We will collect minimal personal identifiable information, including: age, date of birth, sex, education, religion, location and job title.

Personal information gathered as part of interviews and FGDs will be pseudo-anonymised with study ID numbers. Participants will be informed of the use of their data during informed consent and will be reminded that they do not have to participate. Personal identifiable information obtained during the recruitment questionnaire to enable a follow-up at 14 days will be deleted before data are stored and archived, and not be shared outside the team.

Interviews and FGDs will be audio-recorded, using a digital voice recorder, with individual informed consent. Audio files and video files will be stored on the local researcher’s computer while being processed in an encrypted folder and will be stored by the responsible investigators on university secure servers at University College London and Karolinska Institutet.

Electronic data will be collected on Android devices, using CommCare (Dimagi, Cambridge, Massachusetts). Each data collector will use a password-protected device for data collection. Electronic data will be stored in raw instance files, and.csv and Stata.dta formats, on password-protected devices and deleted from the audio recorders and android tablets at the end of the study period. The app includes child case logic to allow follow-up and recruitment forms to be linked with a unique and anonymised ID, and in-built cleaning rules and branching logic will be used to ensure data quality. Data checks will be done throughout the project, and major errors (eg, eligibility and outcome) will be verified in the field. All data management and processing will be done using Stata SE14 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Completed paper consent forms will be stored in a locked filing cabinet in a guarded office compound at University College Hospital Ibadan and will be archived for 10 years, then disposed of securely by burning.

Patient and public involvement

This project benefited from codesign activities from early in its genesis, including a codesign workshop in April 2019 involving representatives from civil society, local and national government and professional organisations, together with Save the Children, GlaxoSmithKline and evaluation partners (Annex 7). Selection of the facilities was conducted in partnership with the Ikorodu Local Government. Community perspectives were sought during the situational analysis but community members were not consulted in the design of the intervention or evaluation.

Ethics and dissemination

Given the rapidly changing COVID-19 situation, we have embedded adaptive methods for data collection and will continuously monitor risks. The protocol is based on the following assumptions: we will be able to collect data within health facilities; project staff will be able to move around Lagos State; the project will end in December 2022.

This study has received ethical approval from the University of Ibadan (REF UI/EC/19/0551), Lagos State (REF LS/PHCB/MS/1128/VOL.V1/005) and University College London (REF 3433/005). We will seek individual written consent for FGDs/IDIs and verbal consent for other questionnaires. We will obtain facility-level approvals for equipment audits and case note reviews. All interviews, FGDs and questionnaires completed by healthcare providers will be anonymous.

We do not anticipate any serious negative impacts to participants taking part in this research, and the intervention should benefit children and healthcare providers directly. The main ethical challenge presented by the impact evaluation is the management of cases with discrepant diagnoses between routine care and clinical research assessments. We decided that in cases where a child meets the criteria for referral from primary to secondary-level care according to our research assessment, we will notify the responsible HCW immediately.

Due to COVID-19, there may be a risk posed to study staff based in clinics while community transmission is on-going. We will ensure that staff are supplied with adequate PPE and IPC training, and we will discuss with the clinics leads how we can best support efforts to maintain hygiene and distancing practices. We will provide study staff with transport to and from clinics and assign data collection rotas to minimise travel.

Interviews, FGDs and surveys will take between 15 min and 90 min. To mitigate the time burden, data collection will be conducted in private locations that are convenient to the participants and we will reimburse participants for transport cost and provide a refreshment. For the recruitment questionnaires, we will monitor the duration of these interviews to ensure they do not delay a severely sick child leaving the clinic to attend hospital.

The topics of discussions, interviews and surveys may result in some participants being upset, due to recent personal experiences of a sick child, or if the discussion raises questions about their professional capacity. We will ensure that questions are asked in a neutral tone, the researchers collecting the data are sensitive to these issues, and that participants are provided with a list of currently available services relating to a range of health concerns in their local areas. In order to minimise any distress from verbal autopsies, they will be conducted no sooner than 14 days after the death (as recommended by WHO), will be done at a time and location which allows privacy for the family, and questionnaires will be pilot tested to ensure cultural sensitivity.

Engagement and dissemination

Engagement with key stakeholders, including HCWs, communities and SMOH officials will be done continuously during the project. Local healthcare providers and caregivers will be recruited as participants, and alongside the formal data collection, will be encouraged to share thoughts and experiences around paediatric pneumonia.

The protocol was developed through round-table discussions with project partners and will be shared with key stakeholders in the Ministry of Health and implementing partner Save the Children Nigeria. Local dissemination events will be held with the SMOH at the end of the project (December 2022), to share the findings and present the plans for future implementation with regular progress meetings prior.

We will publish the main impact results, process evaluation and economic evaluation results as academic publications in international journals. We will also submit abstracts to present findings at both local Nigerian conferences and international conferences on child health and pneumonia throughout the project.

bmjopen-2021-058901supp001.pdf (244.3KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank representatives from the Lagos Ministry of Health and Ikorodu District Health Office for their on-going support and participation in the co-design process for this study.

Footnotes

Twitter: @grahamhamish, @tinylungsglobal, @timcolbourn, @CarinaTKing

Collaborators: INSPIRING Consortium members: Carina King (Karolinska); Tim Colbourn, Rochelle Ann Burgess, Agnese Iuliano (UCL); Hamish R Graham (Melbourne); Eric D McCollum (Johns Hopkins); Tahlil Ahmed, Samy Ahmar, Christine Cassar, Paula Valentine (Save the Children UK); Adamu Isah, Adams Osebi, Ibrahim Haruna, Abdullahi Magama (Save the Children Nigeria); Temitayo Folorunso Olowookere (GSK Nigeria); Matt MacCalla (GSK UK); Adegoke G Falade, Ayobami Adebayo Bakare, Obioma Uchendu, Julius Salako, Funmilayo Shittu, Damola Bakare, and Omotayo Olojede (University of Ibadan).

Contributors: TC, CK, RAB, HRG, EDM, AI, TA, SA, TFO, MM, AAAB, AGF conceived of the study. HRG wrote the first manuscript draft with major input from CK, OEO, TC, EDM, AGF, AAAB. HG, OEO, AAAB, EDM, AI, AI, AO, IS, TA, SA, CC, PV, TFO, MM, OU, RAB, TC, CK, AGF contributed to refinement of the study protocol and approved the final manuscript. TC, CK and AGF are grant holders. HRG and OO are joint first authors. CK and AGF are joint senior authors.

Funding: This work was supported by the GlaxoSmithKline (GSK)-Save the Children Partnership (grant reference: 82603743). Employees of both GSK and Save the Children contributed to the design and oversight of the study as part of a co-design process. Any views or opinions presented are solely those of the authors/publisher and do not necessarily represent those of Save the Children or GSK, unless otherwise specifically stated.

Map disclaimer: The inclusion of any map (including the depiction of any boundaries therein), or of any geographic or locational reference, does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. Any such expression remains solely that of the relevant source and is not endorsed by BMJ. Maps are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: HG, EDM, CK are advisors to Lifebox Foundation on pulse oximetry. AAAB, AGF, HG are board members for Oxygen for Life Initiative (OLI), a private non-profit that provides implementation services to the INSPIRING project. AI, AO, IS, TA, SA, CC, PV are employed by Save the Children UK who are part of the partnership funding the research. TFO, MM are employees of and stockholders in GSK, a multinational for-profit pharmaceutical company that produces pharmaceutical products for childhood pneumonia, including a SARS-CoV2 vaccine, and no direct financial interests in oxygen or pulse oximeter products.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributor Information

on behalf of the INSPIRING Project Consortium:

Carina King, Tim Colbourn, Rochelle Ann Burgess, Agnese Iuliano, Hamish R Graham, Eric D McCollum, Tahlil Ahmed, Samy Ahmar, Christine Cassar, Paula Valentine, Adamu Isah, Adams Osebi, Ibrahim Haruna, Abdullahi Magama, Temitayo Folorunso Olowookere, Matt MacCalla, Adegoke G Falade, Ayobami Adebayo Bakare, Obioma Uchendu, Julius Salako, Funmilayo Shittu, Damola Bakare, and Omotayo Olojede

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . WHO global health observatory data repository. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2021. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/ [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) . Multiple indicator cluster survey 2016-17, survey findings report. Abuja, Nigeria: National Bureau of Statistics and United Nations Children’s Fund, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bakare AA, Graham H, Agwai IC, et al. Community and caregivers' perceptions of pneumonia and care-seeking experiences in Nigeria: a qualitative study. Pediatr Pulmonol 2020;55:S104–12. 10.1002/ppul.24620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Iuliano A, Aranda Z, Colbourn T, et al. The burden and risks of pediatric pneumonia in Nigeria: a desk-based review of existing literature and data. Pediatr Pulmonol 2020;55:S10–21. 10.1002/ppul.24626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. King C, Iuliano A, Burgess RA, et al. A mixed-methods evaluation of stakeholder perspectives on pediatric pneumonia in Nigeria-priorities, challenges, and champions. Pediatr Pulmonol 2020;55:S25–33. 10.1002/ppul.24607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shittu F, Agwai IC, Falade AG, et al. Health system challenges for improved childhood pneumonia case management in Lagos and Jigawa, Nigeria. Pediatr Pulmonol 2020;55:1–13. 10.1002/ppul.24660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Duke T, Subhi R, Peel D, et al. Pulse oximetry: technology to reduce child mortality in developing countries. Ann Trop Paediatr 2009;29:165–75. 10.1179/027249309X12467994190011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. WHO . Oxygen therapy for children. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. WHO . Pocket book of hospital care for children: guidelines for the management of common childhood illnesses. 2nd edn. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Floyd J, Wu L, Hay Burgess D, et al. Evaluating the impact of pulse oximetry on childhood pneumonia mortality in resource-poor settings. Nature 2015;528:S53–9. 10.1038/nature16043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fashanu C, Mekonnen T, Amedu J, et al. Improved oxygen systems at hospitals in three Nigerian states: an implementation research study. Pediatr Pulmonol 2020;55:S65–77. 10.1002/ppul.24694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Graham H, Bakare AA, Fashanu C, et al. Oxygen therapy for children: a key tool in reducing deaths from pneumonia. Pediatr Pulmonol 2020;55:S61–4. 10.1002/ppul.24656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Graham HR, Olojede OE, Bakare AA. Measuring oxygen access: lessons from health facility assessments in Nigeria. medRxiv 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Duke T, Graham SM, Cherian MN. Oxygen is an essential medicine: a call for international action. Int J Tubercul Lung Dis 2010;14:1362–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization . World Health organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization . WHO model list of essential medicines for children: 7th list. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Graham H, Tosif S, Gray A, et al. Providing oxygen to children in hospitals: a realist review. Bull World Health Organ 2017;95:288–302. 10.2471/BLT.16.186676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bakare AA, Graham H, Ayede AI, et al. Providing oxygen to children and newborns: a multi-faceted technical and clinical assessment of oxygen access and oxygen use in secondary-level hospitals in Southwest Nigeria. Int Health 2020;12:60–8. 10.1093/inthealth/ihz009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Graham HR, Bakare AA, Gray A, et al. Adoption of paediatric and neonatal pulse oximetry by 12 hospitals in Nigeria: a mixed-methods realist evaluation. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000812. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baker T, Schell CO, Petersen DB, et al. Essential care of critical illness must not be forgotten in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020;395:1253–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30793-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. WHO, UNICEF . WHO-UNICEF technical specifications and guidance for oxygen therapy devices. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22. WHO . Technical specifications for oxygen concentrators. In: WHO medical device technical series. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23. WHO . Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) technical guidance: essential resource planning. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/covid-19-critical-items [Google Scholar]

- 24. Olowu A, Elusiyan JBE, Esangbedo D, et al. Management of community acquired pneumonia (CAP) in children: clinical practice guidelines by the paediatrics association of Nigeria (Pan). Niger J Paediatr 2015;42:283. 10.4314/njp.v42i4.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nigeria FMoH . National strategy for the scale-up of medical oxygen in health facilities 2017-2022. Abuja, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nigeria FMoH . National policy on medical oxygen in health facilities. Abuja, Nigeria: Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nigeria FMoH . National integrated pneumonia control strategy and implementation plan. Abuja, Nigeria: Federal Ministry of Health, Government of Nigeria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nigeria FMoH . Essential medicines list. 5th edn. Abuja, Nigeria: Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29. WHO . Integrated management of childhood illness - chart booklet. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO), 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30. WHO . Verbal autopsy instrument. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Graham HR, Bakare AA, Ayede AI, et al. Oxygen systems to improve clinical care and outcomes for children and neonates: a stepped-wedge cluster-randomised trial in Nigeria. PLoS Med 2019;16:e1002951. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kürüm E, Warren JL, Schuck-Paim C, et al. Bayesian model averaging with change points to assess the impact of vaccination and public health interventions. Epidemiology 2017;28:889–97. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h1258. 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mannell J, Davis K. Evaluating complex health interventions with randomized controlled trials: how do we improve the use of qualitative methods? Qual Health Res 2019;29:623–31. 10.1177/1049732319831032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Clarke V, Hayfield N, Moller N. Once upon a time…: story completion methods. In: Press CU, ed. Collecting qualitative data: a practical guide to Textual, media and virtual techniques. Cambridge, 2017: 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- 36. King C, Banda M, Bar-Zeev N, et al. Care-seeking patterns amongst suspected paediatric pneumonia deaths in rural Malawi. Gates Open Res 2020;4:178. 10.12688/gatesopenres.13208.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Batura N, Pulkki-Brännström A-M, Agrawal P, et al. Collecting and analysing cost data for complex public health trials: reflections on practice. Glob Health Action 2014;7:23257. 10.3402/gha.v7.23257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bozzani FM, Arnold M, Colbourn T, et al. Measurement and valuation of health providers' time for the management of childhood pneumonia in rural Malawi: an empirical study. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:314. 10.1186/s12913-016-1573-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sessions KL, Mvalo T, Kondowe D, et al. Bubble CPAP and oxygen for child pneumonia care in Malawi: a CPAP IMPACT time motion study. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:533. 10.1186/s12913-019-4364-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. WHO . Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection is suspected 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-058901supp001.pdf (244.3KB, pdf)