Abstract

Objective

To systematically identify and describe approaches to prioritise primary research topics in any health-related area.

Methods

We searched Medline and CINAHL databases and Google Scholar. Teams of two reviewers screened studies and extracted data in duplicate and independently. We synthesised the information across the included approaches by developing common categorisation of relevant concepts.

Results

Of 44 392 citations, 30 articles reporting on 25 approaches were included, addressing the following fields: health in general (n=9), clinical (n=10), health policy and systems (n=10), public health (n=6) and health service research (n=5) (10 addressed more than 1 field). The approaches proposed the following aspects to be addressed in the prioritisation process: situation analysis/ environmental scan, methods for generation of initial list of topics, use of prioritisation criteria, stakeholder engagement, ranking process/technique, dissemination and implementation, revision and appeal mechanism, and monitoring and evaluation. Twenty-two approaches proposed involving stakeholders in the priority setting process. The most commonly proposed stakeholder category was ‘researchers/academia’ (n=17, 77%) followed by ‘healthcare providers’ (n=16, 73%). Fifteen of the approaches proposed a list of criteria for determining research priorities. We developed a common framework of 28 prioritisation criteria clustered into nine domains. The criterion most frequently mentioned by the identified approaches was ‘health burden’ (n=12, 80%), followed by ‘availability of resources’ (n=11, 73%).

Conclusion

We identified and described 25 prioritisation approaches for primary research topics in any health-related area. Findings highlight the need for greater participation of potential users (eg, policy-makers and the general public) and incorporation of equity as part of the prioritisation process. Findings can guide the work of researchers, policy-makers and funders seeking to conduct or fund primary health research. More importantly, the findings should be used to enhance a more coordinated approach to prioritising health research to inform decision making at all levels.

Keywords: Public Health, Health systems, Health policy, Health services research, Review

Key questions.

What is already known?

Although there is a growing number of reports on approaches to primary health research prioritisation, we are not aware of any systematic synthesis of that body of evidence irrespective of research topic, geographical or institutional setting.

What are the new findings?

We created a common framework of prioritisation criteria and stakeholder types that respectively captured all criteria and stakeholders mentioned in each of the 25 identified approaches.

Less than half of the identified approaches proposed involving potential users (eg, policy-makers, government and the general public) or incorporated equity-related criteria as part of the prioritisation process.

What do the new findings imply?

We provide specific suggestions for which approaches to consider when emphasis is on patients and public engagement, equity, a specific field of research, or the availability of time and resources.

Introduction

Health research can strengthen health systems, accelerate progress on the Sustainable Development Goals and improve population health.1–4 The past few years have witnessed increased global calls to make better use of health research in policy-making and practice.5–7

The global COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced the importance of appropriately identifying the health issues that must be prioritised for research.8–11 Hydroxychloroquine represents a notorious example of inappropriate research investment and duplication of efforts. While initially haled as a miracle drug for treating patients with COVID-19, the ensuing research showed that this drug is ineffective and potentially harmful.12 13 In spite of that fact, numerous primary studies continued to be conducted on the effectiveness and safety of hydroxychloroquine in treating COVID-19 patients.14–16

The large number of competing topics for health research is coupled with limited available resources. Therefore, prioritisation processes are increasingly recognised as essential for the optimal allocation of resources to areas of greatest need and impact, especially in resource-poor environments.17–20 In particular, priority setting can maximise the likelihood that potentially impactful research is funded,21 and that research outputs reflect the needs of a broad range of stakeholders.22 23 It could also ensure more efficient and equitable use of limited resources and less duplication of research efforts.24–26 This aligns with global efforts to reduce research waste and avoid duplication of research efforts.27

A systematic and transparent prioritisation approach to assist decision-makers and research funding agencies in making investment decisions is critical.28 Although there is a growing number of reports on approaches to primary health research prioritisation, we are not aware of any comprehensive synthesis of that body of evidence; previous systematic reviews on prioritisation for primary research did not specifically explore the approaches used, and were restricted to geographic areas such as selected high-income countries23 or selected low-income and middle-income countries.24 More recent reviews examined approaches and exercises conducted to prioritise topics or questions specifically for systematic reviews29 or practice guidelines.30 31

Therefore, the aim of this study was to systematically identify and describe approaches to prioritise primary research topics in any health-related area, irrespective of geographical or institutional setting. Findings will enable a better understanding of the landscape of approaches used to prioritise primary health research.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review on approaches to prioritise primary research topics in health related areas, addressing the following broad areas: steps of the development process of the prioritisation approaches; aspects proposed to be addressed in the prioritisation process; methods for generation of initial list of topics; prioritisation criteria and stakeholder involvement.

We opted for a scoping review, which is typically used to present ‘a broad overview of the evidence pertaining to a topic, irrespective of study quality, to examine areas that are emerging, to clarify key concepts and to identify gaps’.32 Scoping reviews are an ideal tool to convey the breadth and depth of a body of literature on a given topic and give clear indication of the volume of literature and studies available as well as an overview of its focus.33 In contrast to a systematic review, it ‘is less likely to seek to address very specific research questions nor, consequently, to assess the quality of the included studies’.34

We followed standard methodology and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines for reporting scoping reviews35 (online supplemental file 1). This study is based on a protocol available in online supplemental file 2.

bmjgh-2021-007465supp001.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

bmjgh-2021-007465supp002.pdf (116.3KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria

Type of study: We included all types of study designs except for commentaries, news, editorials, correspondences, letters to editors, viewpoints, abstracts and reviews. While we excluded reviews, we planned to assess for eligibility the studies that they included.

-

Scope: We included studies describing approaches for prioritising topics for primary research in any health-related area.

We considered ‘approach’ as an umbrella term for frameworks, checklists, models, and methods used to set health research priorities. The description of the approach should have been detailed enough to allow for reproducibility, practically using at least one section dedicated to that description. We excluded studies describing the output of a prioritisation exercise (ie, the priorities) without describing the approach. We excluded studies describing individual prioritisation items or criteria (eg, burden of disease and cost) but not describing a prioritisation approach or model. Additionally, we excluded studies that looked at ranking techniques (such as Delphi and nominal group techniques) in isolation of a broader prioritisation approach.

Health-related areas included clinical, public health, health service and/or health systems and policy research. We did not limit the review to any specific health topic. We excluded animal studies and studies on genetics.

We considered primary research as quantitative or qualitative research that requires the researcher to engage directly in primary data-gathering process as opposed to depending on already existing data (ie, secondary research). We excluded priority setting approaches focusing on healthcare or service delivery priorities (ie, not specific to research).

Setting: We did not limit study eligibility to any geographical setting (eg, low-income, middle-income or high-income countries) or prioritisation level (institutional, subnational, national, regional or international).

Search strategy

We searched Medline and CINAHL electronic databases up until January 2021. We developed the search strategy with the help of an information specialist. The search combined various terms for health prioritisation and included both medical subject headings and free-text words. We did not restrict the search to any dates or languages. The detailed search strategy is provided in online supplemental file 3. We also manually searched Google Scholar as well as screened the reference lists of included studies and other relevant reviews to retrieve additional studies.

bmjgh-2021-007465supp003.pdf (123.8KB, pdf)

Study selection

We completed the selection process in two stages:

Title and abstract screening: Three teams of two reviewers used the above eligibility criteria to screen titles and abstracts of identified citations in duplicate and independently for potential eligibility. They obtained the full texts for citations judged as potentially eligible by at least one of the two reviewers.

Full-text screening: The same three teams of two reviewers screened the full texts in duplicate and independently for eligibility. They resolved disagreement by discussion or with the help of a third reviewer when consensus could not be reached. They used a standardised and pilot-tested screening form.

Prior to proceeding with the selection process, we conducted two rounds of calibration exercises using a randomly selected sample of 100 citations for the first round, and a random sample of 50 citations for the second round. The calibration exercise allowed us to pilot the eligibility criteria to ensure they are applied in the same way across reviewers, thus enhancing the validity of the selection process.

Data abstraction

Two teams of two reviewers abstracted data from eligible studies in duplicate and independently using a standardised and pilot-tested data abstraction form. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, and when needed, with the help of a third reviewer. We conducted a calibration exercise on a random sample of three studies to ensure the data abstraction variables are clear and interpreted in the same way across reviewers, thus enhancing the validity of the data abstraction process.

We abstracted the following information from each included approach:

General characteristics: authors; location; year of publication; name of the approach; lead entity; target audience; field (eg, clinical, public health or health systems); level of prioritisation (institutional, subnational, national, international); funding agency; output of prioritisation and type of publication.

Steps of the development process of the prioritisation approaches, we used the abstracted data to create a common categorisation of the steps used in the development process (eg, use of a pre-existing framework/approach; literature review; consensus building; stakeholder input; pilot-testing). We collected this information as it reflects the thoroughness of the development process.

Aspects proposed to be addressed in the prioritisation process; we used the abstracted data to create a common categorisation of the aspects proposed by the approaches (eg, situation analysis/environmental scan; methods for generating initial list of research topics; use of prioritisation criteria; stakeholder engagement (types of stakeholders proposed to be involved and the role of the different proposed stakeholders); ranking process/technique; dissemination and implementation; revision or appeal mechanism; and monitoring and evaluation). We collected this information as it reflects the breadth of the aspects of prioritisation covered by the approach.

We did not conduct a formal assessment of the risk of bias within or across studies given the descriptive nature of the included studies Furthermore, we are not aware of, and could not identify tools to critically appraise the types of studies retrieved.

Data synthesis

Given the nature of data, we synthesised the findings in a semiquantitative way. We used the abstracted data to come up with common categorisations of relevant concepts (eg, steps of the development process of the approach, aspects proposed to be addressed in the prioritisation process, prioritisation criteria, type and level of stakeholder involvement, methods for generation of initial list of topics), using an iterative process of review and refinement. As part of this process, the content of each study was analysed at least twice; once when drafting the initial categories, and after producing an advanced draft. Throughout this process, team members with subject expertise were consulted to validate categorisation decisions and discuss emerging concepts. We reported the results in both narrative and tabular formats.

The concepts we addressed in our analysis were the following (with the analytical approach that we followed included in brackets):

Steps of the development process of the prioritisation approaches (content analysis).

Aspects proposed to be addressed in the prioritisation process(content analysis).

Methods for generation of initial list of topics (descriptive analysis).

Prioritisation criteria: we used as an initial list of criteria derived from a framework of prioritisation criteria for evidence synthesis topics.29 Two reviewers (RF and ND) independently matched the criteria reported in the included studies to the initial list of criteria derived from the framework. The criteria for which consensus could not be reached were independently reviewed and validated by a third reviewer (AE-H). We subsequently revised the list of criteria to capture those not already captured and drop those that may not apply. Multiple meetings were held to finalise the list of prioritisation domains and criteria.

Stakeholder involvement: we adopted the categories we developed for a recent systematic review on prioritisation for evidence synthesis29 which is based on the 7Ps framework36 as a starting point. We subsequently revised the list of categories to capture those not already captured; for stakeholder roles, we applied content analysis; one reviewer (AE-H) generated an initial list of stakeholder roles from the included studies (based on the data on stakeholder roles abstracted independently by two reviewers). Another researcher (RF) verified the resulting list to improve its clarity and relevance. The two reviewers then met to finalise the list of stakeholder roles through discussion and consensus.

We concluded the results section with a subsection on considerations relevant to selecting an approach.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design and conduct of this scoping review. However, findings have implications for patient and public involvement in the prioritisation of topics for primary health research.

Results

Study selection

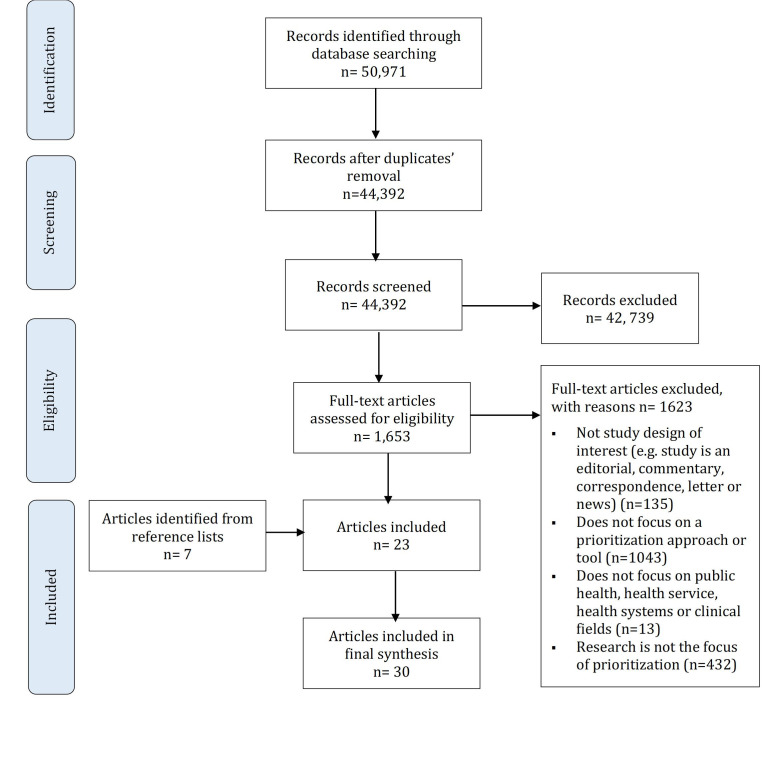

Figure 1 shows the study flow diagram which summarises the selection process. Out of the 44 392 citations identified, we included 30 articles reporting on 25 approaches, with each of 2 approaches reported in 2 articles37–40 and 1 approach reported in 3 articles.41–43 The articles were published between 1997 and 2020 inclusive. Seven of the included articles were obtained from the reference list/bibliography.37 44–49 We excluded 1623 articles at the full-text screening phase for the following reasons: not study design of interest (n=135); focus is not on a prioritisation approach or tool (n=1043); focus is not on research (n=432); and focus is not on public health, health service, health systems or clinical fields (n=13) (see online supplemental file 4 for reasons for exclusion).

Figure 1.

Study selection process.

bmjgh-2021-007465supp004.pdf (1.5MB, pdf)

General characteristics of the prioritisation approaches

Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the 25 identified approaches (see online supplemental file 5 for detailed overview and description of each approach). The majority of the approaches originated from high-income countries, with government as the main funding source (n=10, 40%). Eighteen of the 25 (or 72%) approaches were published in peer reviewed articles. The included approaches addressed the following fields: health in general (n=9, 36%); clinical (n=10, 40%), health policy and systems (n=10, 40%); public health (n=6, 24%) and health service research (n=5, 20%); Ten of the approaches addressed more than one field. The approaches are applicable to the following levels of prioritisation: national (n=20, 80%) international (n=7, 28%), institutional (n=7, 28%), regional (n=5, 20%) and subnational (n=7, 28%); ten of the approaches addressed more than one level of prioritisation. As for prioritisation outputs, these included research topics (n=10, 40%), specific research questions (n=6, 24%), or research themes (n=1, 4%); in nine of the approaches, the output was not specific. Seventeen of the approaches proposed ranking the priorities and the remaining eight proposed listing them (without ranking). Only one approach (reported by three papers) also proposed prioritising outcomes for the priority research questions.41–43 Seven of the approaches had an explicit focus on promoting patient participation,45 46 50–54 and three (reported by four papers) incorporated an equity dimension to health research priority setting.38 49 55 56

Table 1.

General characteristics of the 25 included approaches

| Characteristics | Description | N (%) | Referencing |

| Setting | High income | 17 (68) | 37 41 43 45 46 49–61 64 67 * |

| Middle income | 2 (8) | 44 63 | |

| Low income | – | – | |

| Not reported | 6 (24) | 38–40 47 48 62 65 75 * | |

| Field† | Clinical | 10 (40) | 41 43–45 49 51 53 54 56 59 60 65 67 * |

| Health policy and systems | 9 (36) | 37 44 49 51–56 60 65 * | |

| Public health | 6 (24) | 37 49 53 54 56 58 65 * | |

| Health in general | 9 (36) | 38–40 47 48 50 57 61–63 75 * | |

| Health services research | 5 (20) | 46 49 56 58 59 64 * | |

| Level of prioritisation† | Institutional | 7 (28) | 37 38 41 43 46–48 62 64 67 * |

| Subnational | 7 (28) | 39 40 47 49 52 54 56 59 62 * | |

| National | 20 (80) | 37–41 43–48 50 51 53 55 57–59 61–65 67 * | |

| Regional | 5 (20) | 37 38 46–48 62 * | |

| International | 7 (28) | 37–40 46 48 60 62 65 75 * | |

| Funding† | Governmental | 10 (40) | 41 43 51–53 55 57 59 60 63 64 67 * |

| Intergovernmental | 2 (8) | 37 75 | |

| Private not for profit | 6 (24) | 49–51 53–56 * | |

| Private for profit | – | – | |

| Not reported | 10 (40) | 38–40 44–48 58 61 62 65 * | |

| Type of publication | Peer review | 18 (72) | 37 44 46 49–56 58–65 * |

| Grey literature | 7 (28) | 41 44–46 48 53 54 57 62 63 67 * |

*More than one study reporting on the same approach.

†Percentages add up to more than 100% as more than one option applies.

bmjgh-2021-007465supp005.pdf (362KB, pdf)

Development process of the prioritisation approaches

Table 2 provides a description of the steps followed for the development process of the different prioritisation approaches. In three approaches (reported by four papers), the development process was not described.39 40 57 58 We categorised the steps as follows: use of a pre-existing approach, literature review, consensus building, stakeholder input and pilot-testing. The most frequently reported steps used in the development process were reviewing the literature (n=14, 64%) and building on a pre-existing approach (n=14, 64%). Eleven (or 50%) of the approaches were pilot-tested.

Table 2.

Steps of the development of the prioritisation approaches (N=22)

| Use of a pre-existing approach | Literature review | Consensus building | Stakeholder input | Pilot-testing | |

| N (%) approaches reporting the step* | 14 (64) | 14 (64) | 3 (14) | 7 (32) | 11 (50) |

| Abma, 201050 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Ball, 201664 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Bennett, 2010; Bennett, 2012; Saldanha, 201341–43 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Berra, 201059 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Chang, 201260 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Chapman, 201365 | ✓ | ||||

| Cowan, 201345 | ✓ | ||||

| Dubois, 201161 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Edwards, 201952 | ✓ | ||||

| Franck, 2018; Franck, 202049 56 | ✓ | ||||

| Ghaffar, 2009; 200938 48† | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Hacking, 201644 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Kapiriri, 201863 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Lomas, 200346 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Montorzi, 201047 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Pratt, 201655 | ✓ | ||||

| Rudan, 2006, 200837 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Somanadhan, 202053 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Viergever, 201062 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Wald, 201451 | ✓ | ||||

| WHO, 199675 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Yan, 202054 | ✓ | ✓ |

*The denominator reflects the total number of approaches that described the steps of the development of the approach.

†The tool has now been further refined into a Three-Dimensional Combined Approach Matrix which is described in this document.

Eight of the approaches (reported by nine studies)38 50 59–64 covered more than half of the steps identified in the development process, with one following all of the steps in the development process.59

Aspects to be addressed in the prioritisation process

Table 3 shows the aspects to be addressed when prioritising primary research topics, as proposed by the different approaches. The vast majority of approaches (n=23, 92%) included the involvement of stakeholders as one aspect of prioritisation. Most approaches also proposed the following as key aspects to be addressed in the prioritisation process: methods for generation of initial list of topics (n=19, 76%), use of prioritisation criteria (n=18, 72%), description of ranking process/technique (n=18; 72%) and dissemination & implementation of prioritisation outputs (n=16, 64%). Less than half of the approaches proposed monitoring and evaluation (n=10; 40%).

Table 3.

Aspects to be addressed in the prioritisation process, as proposed by the approaches (N=25)

| Situation analysis/environmental scan | Methods for generation of initial list of topics | Use of prioritisation criteria | Stakeholder engagement | Description of ranking process/ technique | Dissemination and implementation | Revision or appeal mechanism | Monitoring and evaluation | |

| N (%) approaches reporting the aspect | 7 (28) | 19 (76) | 18 (72) | 23 (92) | 18 (72) | 16 (64) | 10 (40) | 10 (40) |

| Abma, 201050 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Ball, 201664 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Bennett, 2010; Bennett, 2012; Saldanha, 201341–43 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Berra, 201059 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Carson, 200058 | ✓ | |||||||

| Chang, 201260 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Chapman, 201365 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Cowan, 201345 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Dubois 201161 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Edwards, 201952 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Franck, 2018; Franck, 202049 56 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Ghaffar, 2009; 200938 48 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Hacking, 201644† | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Kapiriri, 201863 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓* | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Lomas, 200346 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Montorzi, 201047 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| NIH 200157 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Okello, 2000; Lansang 199739 40 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Pratt, 201655† | ✓ | ✓* | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Rudan, 200837 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Somanadhan, 2020 53 * | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Viergever, 201062 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Wald, 201451 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| WHO, 199675 |

✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Yan, 202054 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

*In this approach, ‘ importance’ and ‘feasibility’ were proposed as prioritisation criteria, but authors only considered the score for ‘importance’ when generating the top priorities.

†These approaches indicated the use of prioritisation criteria but did not propose criteria.

Five approaches (reported by six papers) covered all aspects of prioritisation, and were, thus, considered the most comprehensive and detailed.39 40 45 52 62 63

Methods proposed for generating initial list of topics

Nineteen approaches proposed methods for generating an initial list of topics for subsequent prioritisation (see table 4). The most frequently used method was seeking input from stakeholders (n=16, 84%) followed by reviewing the literature (n=9, 47%) and assessing research gaps from existing systematic reviews (n=7, 37%). The majority of approaches (n=15, 79%) used more than one method to generate initial list of topics. Four approaches relied on stakeholder inputs alone to generate initial list of topics.37 52 54 55

Table 4.

Methods proposed for generating initial list of topics (N=19)

| Literature review/scan | Research gaps from existing systematic reviews/guidelines | Health information system | Stakeholder inputs | Previous priority-setting exercises | |

| N (%) approaches reporting the method† | 9 (47) | 7 (37) | 4 (21) | 16 (84) | 3 (16) |

| Abma, 201050 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Ball, 201664 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Bennett, 2010; Bennett, 2012; Saldanha, 201341–43 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Chang, 201260 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Chapman, 201365 | ✓ | ||||

| Cowan, 201345 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Ghaffar, 2009; 200938 48 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Edwards, 201952 | ✓ | ||||

| Franck, 2018; Franck, 202049 56 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Kapiriri, 201863 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Lomas, 200346 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Montorzi, 201047 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Okello, 2000; Lansang, 199739 40 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Pratt, 201655 | ✓ | ||||

| Rudan, 200837 | ✓ | ||||

| Somanadhan, 202053 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Viergever, 201062 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Wald, 201451 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Yan, 202054 | ✓ |

*Percentages add up to more than 100% as more than one option applies.

†Initial topics were generated from existing systematic reviews and guidelines.

Prioritisation criteria

Fifteen of the 25 identified approaches (60%) proposed a list of criteria for determining research priorities. There was a total of 135 mentions of criteria across the approaches (range: 3–28). In some of the approaches, there was flexibility in terms of using the prioritisation criteria, that is, criteria were presented as a menu option to select from depending on context. In four approaches (reported by five papers), the proposed criteria constituted different steps of a process or model for prioritisation.23 38 44 58 Three approaches gave weight to the criteria,37 59 63 while two approaches (reported by three papers) proposed weighting of criteria as optional.39 40 62 The remaining approaches did not suggest weighting the criteria. Three approaches proposed that the criteria need to be applied by research experts.37 46 58

We attempted to match the 135 criteria to a published framework of 25 prioritisation criteria classified into 10 domains (online supplemental file 6). In the process, we merged the two domains ‘existing systematic reviews’ and ‘existing primary studies’ into a single domain ‘existing research base’, and revised the criteria accordingly, in alignment with the included studies for this review. Table 5 shows the classification of the identified 28 prioritisation criteria according to the new framework, clustered in nine domains: (1) problem-related considerations; (2) practice considerations; (3) existing research base; (4) amenability to research; (5) urgency; (6) interest of the topic at different levels; (7) implementation considerations; (8) expected impact of applying evidence and (9) ethical, human rights and moral considerations. The criterion most frequently mentioned by the identified approaches was ‘health burden’ (n=12, 80%), followed by ‘availability of resources’ (n=11, 73%), and ‘economic outcomes’ (n=10, 67%). Only one approach (reported by two papers) incorporated more than half of the 28 criteria listed in the framework.39 40

Table 5.

Framework for prioritisation domains and criteria (N=15)

| Prioritization domains (n=9) and criteria (n=28) |

N (%)* | Berra59 2010 |

Carson58 2000† |

Chang60 2012 |

Chapman65 2013 |

Dubois61 2011 |

Ghaffar38 48 2009 | Hacking44 2016 |

Lomas46 2003‡ |

NIH57 2001 |

Okello39 2000 |

Rudan37 2008 |

Somanadhan53 2020§ |

Viergever62 2010 |

Wald51 2014 |

WHO75 1996 |

| Problem-related considerations | ||||||||||||||||

| Health burden | 12 (80%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Economic burden | 3 (20%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Equity considerations | 4 (27%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Determinants of problem | 2 (13%) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Practice considerations | ||||||||||||||||

| Variation in practice | 2 (13%) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Uncertainty for decision-makers/ practitioners practitioners | 0 (0%) | |||||||||||||||

| Existing research base | ||||||||||||||||

| Availability of research on topic | 8 (53%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Usefulness of available research on topic | 1 (7%) | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Potential to change conclusions/advance research | 1 (7%) | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Amenability to research | ||||||||||||||||

| Topic amenability to research | 3 (20%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Urgency | ||||||||||||||||

| Urgency | 5 (33%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Interest of the topic to: | ||||||||||||||||

| Health professionals | 3 (20%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Patients/consumers | 4 (27%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| National stakeholders | 2 (13%) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Regional/global stakeholders | 2 (13%) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Implementation considerations | ||||||||||||||||

| Research capacity | 5 (33%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Applicability / utilization of research | 7 (47%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Availability of resources | 11 (73%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Political will | 3 (20%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Sustainability | 3 (20%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Community engagement | 2 (13%) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Expected impact of applying evidence on | ||||||||||||||||

| Health policy & practice | 3 (20%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Health outcomes | 9 (60%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Economic outcomes¶ | 10 (67%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Patient experience of care | 2 (13%) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Equity | 4 (27%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Development & broader society | 1 (7%) | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Ethical, human rights & moral considerations | ||||||||||||||||

| Ethical, human rights & moral considerations | 4 (27%) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

*The denominator reflects the total number of approaches that proposed specific criteria to be used as part of the priority setting.

†This approach listed some examples of criteria considered by Steering Groups to help reduce a list of indicative questions to a more manageable size for ‘interim’ prioritisation by external stakeholders.

‡Criteria were used by research experts to translate priority issues identified by stakeholders during consultations into priority research themes.

§While two criteria were proposed ‘importance’ and ‘feasibility’, authors only considered the score for ‘importance’ when generating the top priorities.

¶This encompasses cost-effectiveness of interventions.

bmjgh-2021-007465supp006.pdf (322KB, pdf)

The remaining approaches that did not propose using criteria relied on a variety of processes to rank priorities (eg, Delphi technique, nominal group techniques, ranking using a 10-point scale, simple voting), the most common being the Delphi technique.41–43 50 One approach presented a range of ranking techniques, including comparison in pairs; anchored rating scale; Hanlon method and Essential National Health Research (ENHR) method.47 Another approach highlighted several different methods to decide on priorities that broadly fall into two groups: consensus based approaches and metrics based approaches.62

Stakeholder involvement

All but three approaches proposed involving stakeholders in the priority setting process44 47 58 (table 6). The stakeholder category most frequently proposed for involvement was ‘researchers/academia’ (n=17; 77%), followed by ‘healthcare providers’ (n=16, 73%). While slightly more than half of the approaches proposed involving ‘patients and their representatives’ (n=13, 59%), less than half proposed involving ‘members of the public’ (n=9, 41%), ‘caregivers’ (n=7, 32%), ‘NGOs and adovacy groups’ (n=8; 36%) or ‘government/policy-makers’ (n=10; 45%) in the prioritisation process.

Table 6.

Types of stakeholders proposed to be involved in prioritising primary research topics (N=22)

| Approach | Types of stakeholders | |||||||||||||

| Governments/ policy-makers | Healthcare providers | Researchers/ academia | Members of the public | Patients and their representatives | Caregivers | Health system payers | Healthcare managers | Intergovernmental agencies/ Research funders | Product makers/Industry | Press and media organisations | NGOs and advocacy groups | Internal staff | Other | |

| % of approaches reporting* | n=10 45% |

n=16 73% |

n=17 77% |

n=9 41% |

n=13 59% |

n=7 32% |

n=4 24% |

n=2 9% |

n=6 27% |

n=3 18% |

n=1 6% |

n=8 36% |

n=3 18% |

n=6 27% |

| Abma, 201050 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Ball, 201664 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Bennett, 2010; Bennett, 2012; Saldanha, 201341–43 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Berra, 201059 |

✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Chang, 201260 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Chapman, 201365 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Okello, 2000; Lansang 199739 40 | ✓ | ✓* | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Cowan, 201345 | ✓* | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Dubois, 201161 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Edwards, 2019 (52) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Franck, 2018; Franck, 2020 49 56 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Ghaffar, 2009; 200938 48 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Kapiriri, 201863 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Lomas, 200346 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Montorzi, 201047 | ✓** | |||||||||||||

| NIH, 200157 | ✓ | ✓† | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Pratt, 201655 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Rudan, 200837 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Somanadhan, 202053 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Viergever, 201062 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Wald, 201451 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Yan, 202054 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

*The denominator reflects the total number of approaches that proposed stakeholder involvement as part of the priority setting.

†Includes professional associations.

We identified nine distinct roles for stakeholder involvement in the priority setting process (table 7): executive committee/coordination; theme identification phase; establishment of initial list of topics/questions; refinement of topics/questions; prioritisation/ranking of topics/questions; selection of prioritisation criteria and weighting method; validation of prioritisation outputs; dissemination and process evaluation. Across the different stakeholder categories, the most commonly mentioned role was prioritisation/ranking of topics/questions followed by establishment of initial list of topics/questions and theme identification.

Table 7.

The roles for the different types of stakeholders proposed to be involved in prioritising primary research topics (N=25)

| Types of stakeholders | Executive committee/ coordination | Theme identification phase | Establishment of initial list of topics | Refinement of topics/questions | Prioritisation/ Ranking of topics/questions | Selection of criteria and weighting method | Validation of prioritisation output | Process evaluation | Dissemination | Other |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Public policy-makers | 3 (12%) 39 57 62 |

3 (12%) 38 46 57 |

3 (12%) 38 46 60 |

1 (4%) 46 |

6 (24%) 37 46 47 60 62 65 |

1 (4%) 38 |

1 (4%) 46 |

1 (4%)57 | ||

| Healthcare providers | 5 (20%)39 45 57 62 53 | 10 (40%) 38 41 50 51 53 54 57 59 61 64 |

10 (40%) 38 41 45 59 60 61 62 64 53 54 |

1 (4%) 41 |

13 (52%) 41 45 47 50–54 59–62 64 |

3 (12%) 38 59 64 |

2 (8%) 46 52 |

1 (4%) 41 |

1 (4%) 62 |

1 (4%)57 |

| Researchers/academia | 7 (28%) 39 51 57 62 63 64 53 |

8 (32%) 38 41 46 50 53–55 57 |

7 (28%) 38 41 55 65 64 53 54 |

3 (12%) 41 46 52 |

10 (40%) 37 41 46 47 50 55 62 65 53 54 |

3 (12%) 38 55 64 |

1 (4%) 46 |

1 (4%) 41 |

1 (4%)57 | |

| Members of the public | 3 (12%) 39 57 62 |

3 (12%) 49 55–57 |

3 (12%) 49 55 56 64 |

1 (4%) 49 56 |

7 (28%) 37 47 55 62 64 49 56 54 |

2 (8%) (55)(64) |

1 (4%)57 | |||

| Patients and their representatives | 5 (20%) 57 65 64 52 53 |

9 (36%) 41 49–54 56 61 64 |

10 (40%) 41 45 60 61 65 52 64 49 56 53 54 |

2 (8%) 41 49 56 |

12 (48%) 41 45 50 51 60 61 65 52 64 49 56 53 54 |

1 (4%) 64 |

1 (4%) 52 |

1 (4%) 41 |

1 (4%) 45 |

1 (4%)57 |

| Caregivers | 1 (4%) 53 |

3 (12%) 50 51 53 |

4 (16%) 45 65 64 53 |

5 (20%) 45 50 51 53 54 65 |

1 (4%) 64 |

|||||

| Health system payers | 1 (4%) 62 |

2 (8%) 51 61 |

2 (8%) 61 62 |

4 (16%) 47 51 61 62 |

1 (4%) 62 |

|||||

| Research funders | 3 (12%)37 39 62 | 3 (12%) 38 41 46 |

3 (12%) 38 41 60 |

2 (8%) 41 46 |

5 (20%) 37 41 46 60 62 |

2 (8%) 37 38 |

1 (4%)41 | |||

| Product makers/Industry | 2 (8%) 39 62 |

2 (8%) 37 62 |

1 (4%)47 | |||||||

| Press & media organisations | 1 (4%)37 | |||||||||

| NGOs and advocacy groups | 4 (16%) 45 57 62 53 |

3 (12%) 38 53 57 |

4 (16%) 38 60 62 53 |

5 (20%) 37 45 54 60 62 |

1 (4%) 38 |

1 (4%) 62 |

1 (4%) 57 |

|||

| Internal staff | 1 (4%) 57 |

2 (8%) 57 59 |

1 (4%) 59 |

1 (4%) 59 |

2 (8%) 37 59 |

1 (4%)57 | ||||

| Healthcare managers | 1 (4%) 46 |

1 (4%) 46 |

1 (4%) 46 |

|||||||

| Other | 3 (12%) 38 39 63 |

2 (8%) 38 63 |

4 (16%) 38 61 63 64 |

1 (4%) 63 |

2 (8%) 61 63 |

1 (4%) 38 |

1 (4%) 63 |

1 (4%) 63 |

1 (4%)47 |

Eleven approaches described stakeholder recruitment methods, and these ranged from announcement in journal and newspapers, on website, by letter and distribution of brochures; to use of emails and established contacts; mapping stakeholders; checklist for identification of stakeholders; and organisational and personal contacts.37 45 47 50 51 63 Additional methods to recruit representatives of patients and the general public included social media (Twitter, Facebook), radio ads and leveraging existing community-based partnerships. Stakeholders were engaged both via online platforms (eg, online surveys, email discussions, teleconference) and in-person (eg, workshops, smaller meetings) in eleven approaches (reported by 14 papers).37 39–43 45 51–53 61 63–65

Considerations relevant to selecting an approach

Below, we provide considerations relevant to selecting a prioritisation approach when the emphasis is on one of the following: patients and public engagement, equity, a specific field of research, or the availability of time and resources.

Groups seeking to engage patients and the public in prioritisation would benefit from adopting one of the following seven approaches that have highly structured patient and public engagement planning activities45 46 50–54 : the James Lind Alliance (JLA) method (UK), Listening Model (England and Canada), Dialogue Model (Netherlands), The PRioritiEs For Research project informed by the Dialogue model (Canada), Rare Disease Research Partnership approach (Ireland), storytelling approach to identify patient-centred research priorities (USA) and the Approach informed by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute framework (USA).

Priority setting exercises that value the principles of equity should consider one of three approaches (reported by four papers) that explicitly incorporate an equity dimension to health research priority setting.48 49 55 56 The deep inclusion model developed by Pratt et al has been developed for use where research priority-setting is conducted in the context of power inequalities.55 In the three-dimensional (3D) Combined Approach Matrix, the equity dimension facilitates comparison of different social groups in relation to particular health-related or health systems-related problems, ultimately resulting in informed policy decisions that are aimed at improving not only the average level of health, but also its distribution and hence, equity. Social groups can be defined on the basis of gender, income level, race or ethnicity, religion or sexual orientation, depending on the context.48 The Research Priorities of Affected Communities protocol is designed to elicit research questions and achieve consensus on priority research topics directly from members of members of under-represented communities that bear the burden of health disparities related to the health condition of interest. The method is based on a pedagogical framework of Research Justice that seeks to equalise the political power and legitimacy of knowledge generation.49 56

Additionally, the particular field of research should be considered when selecting the priority setting approach to use. While many of the existing approaches (9 approaches reported by 11 papers) address health in general,38–40 47 48 50 57 61–63 66 others are applicable to more specific fields: clinical (10 approaches reported by 12 papers),41 43–45 49 51 53 54 56 59 60 65 67 health systems and policy (10 approaches reported by 11 papers),37 44 49 51–56 60 65 public health (6 approaches reported by 7 papers)37 49 53 54 56 58 65 and health service research (5 approaches reported by 6 papers).46 49 56 58 59 64 For instance, the disability-adjusted life-year-based amended model adopts a clinical lens to define research priorities, which excludes a health systems perspective.44 Similarly, the JLA method has a narrow focus on clinical settings and is overly biased to treatment needs, as opposed to system needs.45 On the other hand, the Seven ‘I’s model does not explicitly encompass a specific disease or injury component as a criterion for priority setting as doing so would focus attention on the ‘wrong end of the health outcomes and risk factor spectrum’; the model encourages the link to population health gains.58

In terms of time and resource constraints, multicomponent approaches have been found to be resource intensive, requiring the involvement and coordination of many participants across multiple stages. This has been described for the 3D Combined Approach Matrix,48 the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative37 and the eight-step process for identifying and prioritising clinically important research needs.41 43 67 In contrast, the developers of the CAHTA method describe it as a relatively agile, low-cost, participatory process that allows for priority-setting over a wide range of topics.59

Discussion

We systematically reviewed the literature on prioritisation approaches for primary research topics in any health-related area. We identified and described 25 prioritisation approaches. The majority of approaches addressed clinical and health policy and systems research topics, were applicable at the national-level, were published by independent researchers and targeted a broad range of stakeholders.38 45 46 50 51 55 None of the included studies reflected on the additional applicability of the identified approaches to other types of health research (eg, evidence synthesis).

There were variabilities in the steps adopted to develop the approaches and the aspects proposed to be addressed in the prioritisation process. Eight approaches (reported by nine papers)38 50 59–64 covered more than half of the steps identified in the development process. Five approaches (reported by six papers)39 40 45 52 62 63 covered all aspects of the prioritisation process (and are, thus, considered the most comprehensive and detailed), namely: situation analysis/environmental scan, methods for generation of initial list of topics, use of prioritisation criteria, stakeholder engagement, ranking process/technique, dissemination and implementation, revision or appeal mechanism, and monitoring and evaluation. Stakeholder involvement and the use of prioritisation criteria represented key aspects of most of the prioritisation approaches.

There was also wide variation across approaches in the prioritisation criteria. To address this, we synthesised the information across the included approaches by developing common categorisation of relevant concepts. This resulted in a common framework of 28 prioritisation criteria clustered in 9 domains. Equity was an infrequent dimension of the priority setting, as reflected by the low number of studies incorporating equity-related prioritisation criteria.

We also developed a common categorisation of 13 stakeholder types and nine distinct stakeholder roles in the priority setting process. The most commonly proposed stakeholder type was researchers/academia followed by healthcare providers, and the most commonly mentioned stakeholder role was prioritisation/ranking of topics/questions.

Despite increased calls for involving research users in the priority setting process, less than half of the approaches involved governments and policy-makers. Engaging governments and policy-makers in research priority-setting exercises can enhance alignment of research production to policy priorities and needs, which in turn, can increase the relevance and likelihood of utilisation of research to inform decisions.19 68 While slightly more than half of the approaches proposed involving patients and their representatives, less than half proposed involving members of the public, caregivers or NGOs and advoacy groups in the prioritisation process. The rising trend in patient involvement may reflect the growing number of patient-centred approaches, particularly within the most recent years. Patient and public participation in priority setting makes research tangible, relevant and valuable for patients and their relatives, enhances the legitimacy and fairness of decision making,69 improves trust and confidence in the health system70 and strengthens the quality of decision making.71 72 Without such engagement from the earliest stages, researchers and healthcare providers may ultimately miss the priority needs of the end users. While the involvement of a wide range of stakeholders can increase the legitimacy, transparency and acceptability of the identified priorities, it also raises challenges in terms of capacity, coordination, communication and resources.63 73 Unfortunately, none of the identified approaches examined these issues in-depth.

Although the global COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced the importance of health research prioritisation, none of the identified approaches focused on identifying research topics or questions in the context of emergencies or public health crisis. Existing priority setting related to COVID-19 pandemic focused largely on prioritisation of patients or healthcare interventions (eg, medications) as opposed to research topics or questions. A recent study on informing Canada’s health system response to COVID-19 conducted a rapid-cycle priority identification process to identify seven COVID-19 priorities for health services and policy research. However, no sufficient details were reported on the methodology applied to generate the priorities.74

To our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively review approaches for prioritising primary research topics in any health-related area, irrespective of geographical or institutional setting. Previous reviews have mainly focused on specific geographic settings23 24 or specific research types.29 In line with our findings, these reviews reported variabilities in priority setting methodologies with inconsistent application of methods and outcomes generated. On the other hand, our findings provide a comprehensive description of approaches for primary research topics in any health-related area, with a more in-depth analysis of relevant characteristics such as the steps, criteria and stakeholders for prioritisation, which enables a better understanding of the landscape of approaches used to prioritise primary health research.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of our methodology include applying a rigorous and transparent process, following standard methods for reporting scoping reviews and including different types of study designs and settings. We also followed an iterative process of review and refinement to create a common framework of prioritisation criteria and stakeholders that respectively captured all criteria and stakeholders mentioned in each of the 25 identified approaches. This denotes progress toward standardising the terminology for prioritisation and enhancing the clarity of criteria for decision making.

Despite our attempt to identify all priority setting approaches for primary health research topics, we could have missed on potentially relevant information, particularly those in specialised data sources (eg, organisational websites). Our review did not seek published data on the implementation of the identified approaches. Additionally, no assessment of risk of bias was conducted given no tool is available for this type of studies; however, this is consistent with the scoping review methodology.35

Implications for practice and policy

The findings of this scoping review can guide the work of researchers, policy-makers, funders and other stakeholders in the field of health research. Those involved should select the approach that best fits their needs, taking into consideration the purpose of priority setting as well as available resources and time constraints. For example, groups can consider our list of prioritisation criteria as a menu of options to select from, as deemed appropriate to the context, with considerations to incorporate equity-related criteria. Efforts should also be invested to ensure greater participation of potential users (eg, policy-makers, government and the general public) as part of the prioritisation process.

Application of the approaches can help support evidence-informed policy-making by aligning research production to policy priorities and needs. They can also help avoid research waste by directing limited resources to areas of highest priority and impact (eg, several of the identified approaches proposed the assessment of research gaps from systematic reviews and subsequent use of such information to generate initial list of primary research topics for prioritisation in order to avoid duplication of work). This is especially relevant in the context of low-income and middle-income countries where resources are already scarce and capacity for research production is limited and often misaligned with policy priorities and needs.

Implications for research

Further rigorous research is needed to examine the feasibility, effectiveness and transparency of several of the identified approaches. This kind of research would allow a better understanding of the potential barriers and facilitators to prioritisation using the existing approaches. It is also essential to evaluate the impact of those approaches on research agenda setting and broader health outcomes. Future work should use the findings of this review as well those of similar reviews addressing other types of health research (eg, evidence synthesis and guideline development) as the building blocks to produce an overarching approach to prioritising topics across the health research spectrum. The ultimate goal should be to inform the decision making of different stakeholders, including government, organisations, professionals and citizens.

Additionally, given the majority of the approaches were developed by researchers from high-income countries, future research can assess the applicability of the approaches in middle-income and low-income countries. Similar research is needed on the applicability and adaptability of the identified approaches beyond the health sector. For example, there is growing interest in approaches to prioritise research topics during pandemics where resources, infrastructure and government capacity to respond are particularly constrained.8–11 The applicability of the identified approaches in the context of emergencies and crises warrants further exploration.

More rigorous research is also needed to assess effective ways of involving stakeholders in different aspects of prioritisation with a focus on promoting greater participation of potential users (eg, policy-makers, government and the general public) including better reporting of operational details of stakeholder engagement. Findings also highlight the need for more research on how to promote equity in priority-setting.

More generally, and given the variability in the identified prioritisation approaches, there is a need for guidance for developing priority-setting approaches and reporting their findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Ms. Aida Farha for her help in developing and validating the search strategy.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Stephanie M Topp

Contributors: EAA and RF conceived and designed the study. FE-J contributed to the conceptualisation of the study. RF coordinated the study throughout. RF, EAA, AE-H and TL ran the search. RF, ND, AE-H, RH, HB, LBK, LCL, GA, IK, SB, AY and TL conducted the study selection processes (title and abstract screening followed by full text screening). RF, ND, AE-H. RH, HB extracted the data. RF, ND, AE-H and EAA. analysed and interpreted the data. RF wrote the first draft of the manuscript with EAA. ND contributed to writing of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version. EAA will act as guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Koon AD, Rao KD, Tran NT, et al. Embedding health policy and systems research into decision-making processes in low- and middle-income countries. Health Res Policy Syst 2013;11:30. 10.1186/1478-4505-11-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavis JN, Ross SE, Hurley JE, et al. Examining the role of health services research in public policymaking. Milbank Q 2002;80:125–54. 10.1111/1468-0009.00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell DM, Redman S, Jorm L, et al. Increasing the use of evidence in health policy: practice and views of policy makers and researchers. Aust New Zealand Health Policy 2009;6:21. 10.1186/1743-8462-6-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO) . Strategy on health policy and systems research: changing the mindset, 2012. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/77942/9789241504409_eng.pdf

- 5.Ghaffar A, Langlois EV, Rasanathan K, et al. Strengthening health systems through embedded research. Bull World Health Organ 2017;95:87. 10.2471/BLT.16.189126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanson K, Rasanathan K, George A. The state of health policy and systems research: reflections from the 2018 5th global symposium. Health Policy Plan 2019;34:ii1–3. 10.1093/heapol/czz113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Lancet . The Bamako call to action: research for health. Lancet 2008;372:1855. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61789-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siddaway AP. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:e43. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30220-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization (WHO) . World experts and funders set priorities for COVID-19 research. WHO, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gulick RM, Sobieszczyk ME, Landry DW, et al. Prioritizing clinical research studies during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from New York City. J Clin Invest 2020;130:4522–4. 10.1172/JCI142151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parvin L, Valdés D, Sinfield C. Health policy and systems research for health system strengthening and pandemic preparedness: challenges, innovations and opportunities, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cortegiani A, Ingoglia G, Ippolito M, et al. A systematic review on the efficacy and safety of chloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. J Crit Care 2020;57:279–83. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiolet T, Guihur A, Rebeaud ME, et al. Effect of hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin on the mortality of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2021;27:19–27. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.08.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abella BS, Jolkovsky EL, Biney BT, et al. Efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine vs placebo for pre-exposure SARS-CoV-2 prophylaxis among health care workers: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2021;181:195–202. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gasmi A, Peana M, Noor S, et al. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19: the never-ending story. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2021;105:1333–43. 10.1007/s00253-021-11094-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vainio PJ, Hietasalo P, Koivisto A-L, et al. Hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of adult patients with Covid-19 infection in a primary care setting (liberty): a structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2021;22:44. 10.1186/s13063-020-04989-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chanda-Kapata P, Ngosa W, Hamainza B, et al. Health research priority setting in Zambia: a stock taking of approaches conducted from 1998 to 2015. Health Res Policy Syst 2016;14:72. 10.1186/s12961-016-0142-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitton C, Donaldson C. Priority setting toolkit: guide to the use of economics in healthcare decision making. John Wiley & Sons, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uneke CJ, Ezeoha AE, Ndukwe CD, et al. Research priority setting for health policy and health systems strengthening in Nigeria: the policymakers and stakeholders perspective and involvement. Pan Afr Med J 2013;16:10. 10.11604/pamj.2013.16.10.2318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viergever RF, Terry R, Matsoso M. Health research prioritization at WHO: an overview of methodology and high level analysis of WHO led health research priority setting exercises. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ranson MK, Bennett SC. Priority setting and health policy and systems research. Health Res Policy Syst 2009;7:27. 10.1186/1478-4505-7-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baltussen R, Niessen L. Priority setting of health interventions: the need for multi-criteria decision analysis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2006;4:14. 10.1186/1478-7547-4-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGregor S, Henderson KJ, Kaldor JM. How are health research priorities set in low and middle income countries? A systematic review of published reports. PLoS One 2014;9:e108787. 10.1371/journal.pone.0108787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bryant J, Sanson-Fisher R, Walsh J, et al. Health research priority setting in selected high income countries: a narrative review of methods used and recommendations for future practice. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2014;12:23. 10.1186/1478-7547-12-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kapiriri L, Martin DK. Successful priority setting in low and middle income countries: a framework for evaluation. Health Care Anal 2010;18:129–47. 10.1007/s10728-009-0115-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nasser M, Welch V, Tugwell P, et al. Ensuring relevance for Cochrane reviews: evaluating processes and methods for prioritizing topics for Cochrane reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:474–82. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet 2009;374:86–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60329-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshida S. Approaches, tools and methods used for setting priorities in health research in the 21st century. J Glob Health 2016;6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fadlallah R, El-Harakeh A, Bou-Karroum L, et al. A common framework of steps and criteria for prioritizing topics for evidence syntheses: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 2020;120:67–85. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Harakeh A, Lotfi T, Ahmad A, et al. The implementation of prioritization exercises in the development and update of health practice guidelines: a scoping review. PLoS One 2020;15:e0229249. 10.1371/journal.pone.0229249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Harakeh A, Morsi RZ, Fadlallah R, et al. Prioritization approaches in the development of health practice guidelines: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:692. 10.1186/s12913-019-4567-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P. The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers' manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:143. 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Concannon TW, Meissner P, Grunbaum JA, et al. A new taxonomy for stakeholder engagement in patient-centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:985–91. 10.1007/s11606-012-2037-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rudan I, Gibson JL, Ameratunga S, et al. Setting priorities in global child health research investments: guidelines for implementation of CHNRI method. Croat Med J 2008;49:720–33. 10.3325/cmj.2008.49.720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghaffar A. Setting research priorities by applying the combined approach matrix. Indian J Med Res 2009;129:368–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okello D, Chongtrakul P. A manual for research priority setting using the ENHR strategy. COHRED, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lansang . Essential National Health Research and Priority Setting: Lessons Learned. In: COHRED workshop on research priority setting, 1997: 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bennett W, Nicholson W, Saldanha I. Future research needs for the management of gestational diabetes. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bennett WL, Robinson KA, Saldanha IJ, et al. High priority research needs for gestational diabetes mellitus. J Womens Health 2012;21:925–32. 10.1089/jwh.2011.3270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saldanha IJ, Wilson LM, Bennett WL, et al. Development and pilot test of a process to identify research needs from a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:538–45. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hacking D, Cleary S. Setting priorities in health research using the model proposed by the world Health organization: development of a quantitative methodology using tuberculosis in South Africa as a worked example. Health Res Policy Syst 2016;14:1–11. 10.1186/s12961-016-0081-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cowan K, Oliver S. The James Lind alliance guidebook. Southampton, UK: National Institute for Health Research Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lomas J, Fulop N, Gagnon D, et al. On being a good listener: setting priorities for applied health services research. Milbank Q 2003;81:363–88. 10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montorzi G, De Haan S, IJsselmuiden C. Council on Health Research for Development (COHRED). In: Priority setting for research for health: a management process for countries, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghaffar A, Collins T, Matlin S, eds. The 3D combined approach matrix: An improved tool for setting priorities in research for health. Geneva: Global Forum for Health Research, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Franck LS, McLemore MR, Cooper N, et al. A novel method for involving women of color at high risk for preterm birth in research priority setting. J Vis Exp 2018;131:e56220. 10.3791/56220 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abma TA, Broerse JEW. Patient participation as dialogue: setting research agendas. Health Expect 2010;13:160–73. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00549.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wald HL, Leykum LK, Mattison MLP, et al. Road map to a patient-centered research agenda at the intersection of hospital medicine and geriatric medicine. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:926–31. 10.1007/s11606-014-2777-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Edwards L, Monro M, Butterfield Y, et al. What matters most to patients about primary healthcare: mixed-methods patient priority setting exercises within the prefer (priorities for research) project. BMJ Open 2019;9:e025954. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025954 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Somanadhan S, Nicholson E, Dorris E, et al. Rare disease research partnership (RAinDRoP): a collaborative approach to identify research priorities for rare diseases in Ireland. HRB Open Res 2020;3:13. 10.12688/hrbopenres.13017.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yan A, Millon-Underwood S, Walker A, et al. Engaging young African American women breast cancer survivors: a novel storytelling approach to identify patient-centred research priorities. Health Expect 2020;23:473–82. 10.1111/hex.13021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pratt B, Merritt M, Hyder AA. Towards deep inclusion for equity-oriented health research priority-setting: a working model. Soc Sci Med 2016;151:215–24. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Franck LS, McLemore MR, Williams S, et al. Research priorities of women at risk for preterm birth: findings and a call to action. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20:1–17. 10.1186/s12884-019-2664-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.National Institutes of Health . Setting research priorities at the National Institutes of health: US department of health and human services. National Institutes of Health, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carson N, Ansari Z, Hart W. Priority setting in public health and health services research. Aust Health Rev 2000;23:46–57. 10.1071/AH000046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berra S, Sánchez E, Pons JMV, et al. Setting priorities in clinical and health services research: properties of an adapted and updated method. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2010;26:217–24. 10.1017/S0266462310000012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chang SM, Carey TS, Kato EU, et al. Identifying research needs for improving health care. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:439–45. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-6-201209180-00515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dubois RW, Graff JS. Setting priorities for comparative effectiveness research: from assessing public health benefits to being open with the public. Health Aff 2011;30:2235–42. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Viergever RF, Olifson S, Ghaffar A, et al. A checklist for health research priority setting: nine common themes of good practice. Health Res Policy Syst 2010;8:36. 10.1186/1478-4505-8-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kapiriri L, Chanda-Kapata P. The quest for a framework for sustainable and institutionalised priority-setting for health research in a low-resource setting: the case of Zambia. Health Res Policy Syst 2018;16:11. 10.1186/s12961-017-0268-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ball J, Ballinger C, De Iongh A, et al. Determining priorities for research to improve fundamental care on hospital wards. Res Involv Engagem 2016;2:1–17. 10.1186/s40900-016-0045-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chapman E, Reveiz L, Chambliss A, et al. Cochrane systematic reviews are useful to map research gaps for decreasing maternal mortality. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:105–12. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ad Hoc Committee on Health Research Relating to Future Intervention Options, World Health Organization . Investing in health research and development: report of the AD hoc Committee on health research relating to future intervention options, Convened under the auspices of the world Health organization. Vol. 96. World Health Organization, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bennett WL, Robinson KA, Saldanha IJ, et al. High priority research needs for gestational diabetes mellitus. J Womens Health 2012;21:925–32. 10.1089/jwh.2011.3270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.El-Jardali F, Makhoul J, Jamal D, et al. Eliciting policymakers' and stakeholders' opinions to help shape health system research priorities in the middle East and North Africa region. Health Policy Plan 2010;25:15–27. 10.1093/heapol/czp059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fleck LM. Just caring: Oregon, health care rationing, and informed Democratic deliberation. J Med Philos 1994;19:367–88. 10.1093/jmp/19.4.367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hunter DJ. Rationing health care: the political perspective. Br Med Bull 1995;51:876–84. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a073002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ham C. Priority setting in the NHS: reports from six districts. BMJ 1993;307:435–8. 10.1136/bmj.307.6901.435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Piil K, Jarden M. Patient involvement in research priorities (PIRE): a study protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010615. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Manafò E, Petermann L, Vandall-Walker V, et al. Patient and public engagement in priority setting: a systematic rapid review of the literature. PLoS One 2018;13:e0193579. 10.1371/journal.pone.0193579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McMahon M, Nadigel J, Thompson E, et al. Informing Canada's health system response to COVID-19: priorities for health services and policy research. Healthc Policy 2020;16:112–24. 10.12927/hcpol.2020.26249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.World Health Organization (WHO) . Ad Hoc Committee on Health Research Relating to Future Intervention Options, & World Health Organization. Investing in Health Research and Development: Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Health Research Relating to Future Intervention Options, Convened Under the Auspices of the World Health Organization. Vol. 96. WHO, 1996. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2021-007465supp001.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

bmjgh-2021-007465supp002.pdf (116.3KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2021-007465supp003.pdf (123.8KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2021-007465supp004.pdf (1.5MB, pdf)

bmjgh-2021-007465supp005.pdf (362KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2021-007465supp006.pdf (322KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.