Abstract

Background

Using data from the ulcerative colitis (UC) narrative Greece survey, part of a global survey of patients and physicians, we aimed to identify the impact of UC on patients’ lives and to compare patients’ and gastroenterologists’ responses to questions relating to communication during the management of UC in our country.

Methods

The survey was conducted online by The Harris Poll, and included 95 patients and 51 gastroenterologists. Eligible were adult UC patients who had seen a gastroenterologist in the past 12 months and had at some time taken a prescription medication (excluding those who had only ever taken 5-aminosalicylates). Patients with mild UC were capped at 20% of total survey respondents to focus the survey on patients with moderate-to-severe disease.

Results

The mean time between first experienced symptoms and diagnosis of UC was 0.89 years. Most patients (82%) considered their UC to be in remission, while 98% felt satisfied with their communication with their treating gastroenterologist. However, the disease affected patients’ daily life and employment adversely, with 78% reporting their UC to be mentally exhausting. Although nearly 7 in 10 physicians (69%) reported having taken steps to improve their communication skills, many patients (60%) wished they had more time at appointments with their physician, while 44% still felt uncomfortable talking about their sex life and personal relationships.

Conclusions

Greek UC patients appear to be satisfied with their physicians and their disease management. Gaps in patient-physician communication relating to quality of life, emotional, and sexual/relationship concerns need to be addressed.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, quality of life, patient-physician communication

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic, idiopathic inflammatory bowel disorder characterized by a relapsing/remitting and less often by a chronic active course [1]. Patients with UC most often deal with unpredictable, unpleasant and potentially embarrassing gastrointestinal symptoms, in addition to treatment-related side effects [2]. However, the burden of disease extends far beyond the clinical signs and symptoms from the gastrointestinal tract and/or extraintestinal sites of involvement, since many other aspects of patients’ lives are affected [3]. Several studies have shown that patients’ employment opportunities, work productivity and social interaction are disturbed [4]. Such issues lead to anxiety and/or depression, which in turn negatively affect patients’ quality of life [5]. This is why the recent initiative of the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), STRIDE-II, has included the absence of disability and the restoration of quality of life as long-term treatment targets in patients with IBD [6].

Our group reported in 2013 that the health-related social life, emotional status, and work productivity of Greek IBD patients were severely affected and that patients complained of a lack of information regarding their therapy [7]. Although these unmet needs called for immediate action by healthcare providers and society, still today physicians often underestimate the disease burden and associated suffering [8], while they may fail to recognize issues important to patients [9].

The present study aimed to examine the perspectives of Greek patients with UC, using data from the UC Narrative Greek survey. This survey aimed to identify the impact of UC on patients’ lives and compare patients’ and physicians’ responses to questions regarding the management of UC. Understanding gaps in patient–physician communication and acknowledging that bridging these gaps will inevitably improve patients’ quality of life and adherence to treatment, we also aimed to compare our findings with those of a similar survey dating back to 2013, during the first period of biologic therapy in Greece.

Materials and methods

The UC Narrative was a global initiative created by Pfizer to engage the UC community to help identify the impact of living with this disease on patients’ lives. The UC Narrative Greece survey findings represent a subset of the UC Narrative global survey, developed with input from the Global UC Narrative Advisory Panel. The initiative involved 2 related global surveys, one patient-based, and one physician-based. The survey of Greek patients and gastroenterologists was conducted online by The Harris Poll between June 25 and August 31, 2020. The patient and physician questionnaires can be found in Supplementary Materials 1 (423.9KB, pdf) and 2 (423.9KB, pdf) , respectively.

Eligible were adult patients with UC who: i) were >18 years of age; ii) resided in Greece; iii) had been diagnosed with UC (confirmed by histological assessment of ileo-colonoscopic biopsies); iv) had visited a gastroenterologist in the past 12 months; v) had at some time taken a prescription medication for their UC (excluding those who had only ever taken 5- aminosalicylates [ASAs]); and vi) provided informed consent to their inclusion in the survey. Patients who had only ever taken 5-ASAs or had undergone a total colectomy were excluded. Patients who had taken corticosteroids in the past (for a period of less than 4 months during the last 12 months) and were on 5-ASAs at the time of the survey were included in the study.

Eligible gastroenterologists were those who: saw ≥10 UC patients each month (of whom ≥10% were taking a biologic); did not mostly practice in an institution for the chronically ill/chronic pain/palliative care; and had a license to practice as a gastroenterologist in Greece. All participating physicians provided informed consent to their inclusion in the survey.

Disease severity in this study was defined using a novel patient-reported medication history. Patients with moderate to severe UC were defined as those who had taken an immunosuppressant or a biologic for their UC at any time, or had taken corticosteroids for ≥4 months in the last 12 months. Patients with mild UC were defined as those who had never taken a biologic or immunosuppressant and those who had taken corticosteroids for ≤3 of the past 12 months. Patients with mild UC were capped at 20% of total survey respondents to focus the survey on patients with moderate-to-severe UC. This was deemed necessary, since the primary goal of the survey was to characterize the experiences of UC patients believed to be living with moderate-to-severe disease or those who may be living with poorly controlled disease. The choice to focus on these patient types assumed that these groups (vs. those with milder disease) are more likely to be in need of support and resources, which the survey could help better identify. Remission was self-reported by patients and was defined as disease being controlled with few to no symptoms

The surveys were designed to assess: i) patients’ symptoms; ii) the impact of UC on mental health and daily life; iii) the impact of the disease on employment and education; iv) communication between patients and physicians; v) knowledge of the disease; and vi) medication preference and satisfaction. The physician questionnaire mirrored the patient questionnaire where applicable. Physicians were asked to base their survey responses on their experiences of treating patients with moderate-to-severe UC, as defined previously. Questions in both patient and physician questionnaires required respondents to provide a numeric response, to select a single option or multiple options from a list, or to indicate their level of agreement with a statement (ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”).

Statistical analysis

Survey responses were analyzed globally and by country. Descriptive statistics were used to assess patient and physician responses. Analyses were primarily conducted in IBM SPSS. The raw data were analyzed by The Harris Poll. Given the nature of the survey, there was no formal statistical hypothesis or predetermined sample size.

Ethical considerations

The surveys were non-interventional, were not intended to provide clinical data for treatment decisions and were not conducted as a clinical trial for any endpoints; ethics approval was therefore not required. All respondents provided their informed consent and were compensated by Harris Poll on behalf of the sponsor.

Results

Demography

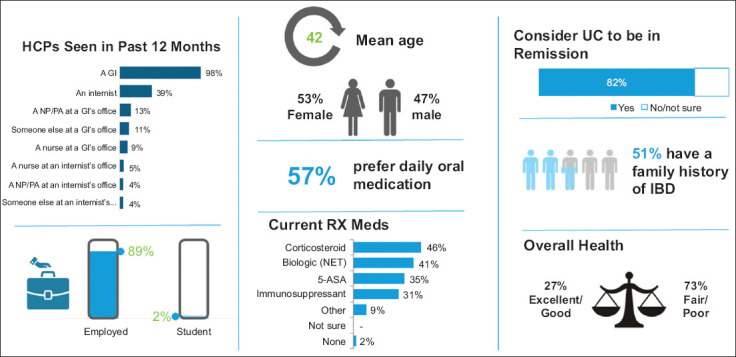

Overall, 95 adults (47% male), with a mean age of 42±13.69 years, participated in the survey. All respondents resided in Greece, 57% were employed full time and 5% part time, 20% were self-employed full time, and 1% part time, 7% were a stay-at-home spouse or partner, 6% were not employed but looking for work, 2% were retired and 1% were students. As regards their family status, 36% reported that they did not have any children, while the remaining 64% reported being a parent of 1 child (21%), 2 children (33%), 3 children (7%) or 4 or more children (3%). Further information regarding patient demographics can be seen in Fig. 1. The physicians’ study sample consisted of 51 gastroenterologists (76% male), with a mean age of 52±10.21 years, of whom 29% worked exclusively in a hospital or a clinic, 12% worked exclusively in a private doctor’s office, while the remaining 57% worked both in a hospital/clinic and in a private doctor’s office. Most of them (88%) had more than 10-year experience in specialty practice, while 2% had 0-5-year, and 10% had 6-9-year experience in specialty practice.

Figure 1.

Profile of patients with ulcerative colitis in Greece

HCP, healthcare practitioner; GI, gastroenterologist; NP, nurse practitioner; PA, physician assistant; UC, ulcerative colitis: RX, prescription; 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylate acid; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease

Time to diagnosis and access to care

The mean time between first experienced symptoms and the diagnosis of UC was 0.89 years (interquartile range=2); more specifically, in 58% of patients it was less than 1 year, whereas in 15%, 17%, 3%, 3% and 4% it was 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 or more years, respectively. Most patients (94%) had direct access to a gastroenterologist, 32% to a nutritionist/dietician, and 20% to a psychiatrist or psychologist.

Symptoms and medications

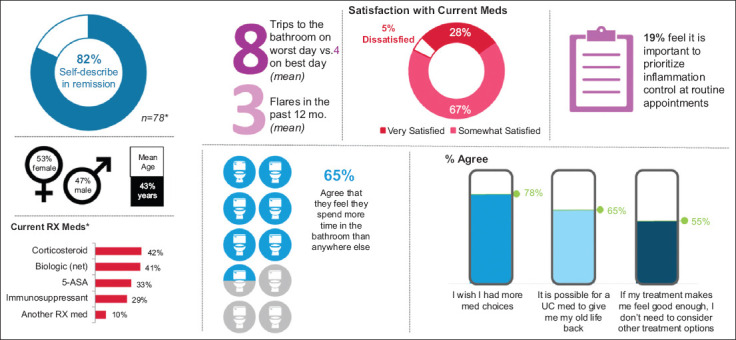

Most patients (82%) considered their UC to be in remission, whereas the proportion of patients that the treating physicians believed to be in remission was 68%. Despite the medication used, patients still reported symptoms (Fig. 2). Specifically, when they were asked about the number of bathroom visits for any reason other than to urinate (e.g., to pass stool, air, blood, or mucus) on their best day, 17% reported one bathroom visit, 34% reported 2-3 bathroom visits, 40% 4-9 bathroom visits, and 9% ≥10 bathroom visits. Meanwhile, most patients (95%) reported having had at least 1 flare in the past 12 months; more specifically, 15% reported 1 flare, 27% 2 flares, 22% 3 flares, 9% 4 flares, 8% 5 flares, 7% 6-9 flares, and 5% ≥10 flares.

Figure 2.

Patients who self-report remission still experience disease symptoms and impacts

UC, ulcerative colitis; RX, prescription, 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylate

Impact of UC on mental health and daily life

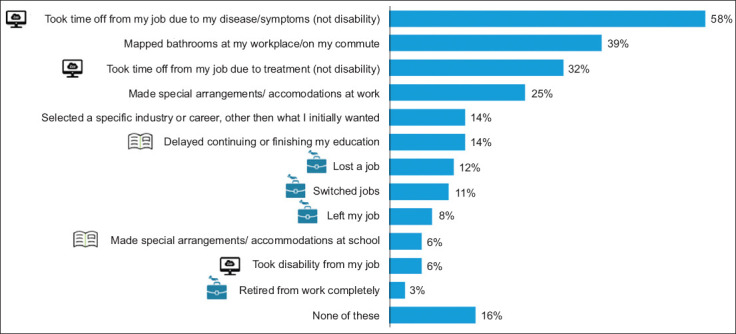

Nearly 4 in 5 patients (78%) found their UC to be mentally exhausting, even among patients with milder disease or those who self-reported to be in remission. More than 2 in 3 UC patients (68%) felt that the disease controlled their life, rather than themselves. Patients experienced a variety of emotions during a UC flare, mostly increased fatigue (74%), as can be seen in Table 1. When patients were asked about their top 5 worries due to UC, they mentioned the potential risk of developing cancer (54%), or the need for a colectomy or a stoma in the future (51%), the fear that UC might get worse (47%) or cause other long-term health problems (32%), and the risk of passing on the disease to their children (25%). Patients reported missing a variety of events due to their UC, including their children’s events (54%), social events (46%) or travel plans (60%). One third of patients reported specific family impacts due to their UC, such as postponing having children (14%), and ending romantic relationships or avoiding marriage (14%). Meanwhile, many physicians (51%) felt that the majority of their patients had accepted the fact that having UC meant settling for a reduced quality of life. Furthermore, while physicians did appear aware of patients’ top UC-related worries, only 16% of them said discussing cancer risk was a top priority during routine appointments.

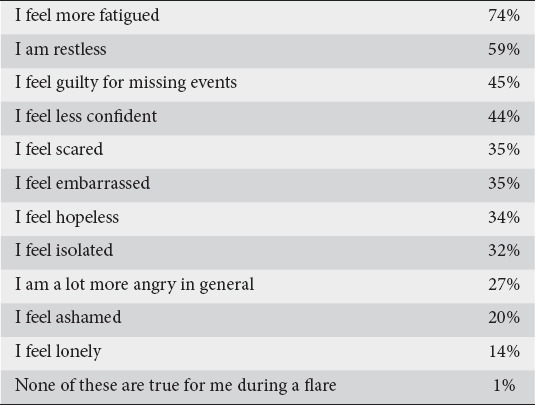

Table 1.

Emotions experienced during an ulcerative colitis flare

Impact of UC on employment and education

Overall, UC had a negative impact on patients’ employment (Fig. 3). Four in 5 (81%) patients felt they would be more successful if they did not have UC. Most employed patients (88%) reported having missed at least 1 day of work because of their disease/symptoms, while 79% had missed work because of treatment or medical appointments. Although most patients (65%) agreed that their employer was understanding, more than one-third (36%) had not reported that they were suffering from UC, for fear of repercussions. Three in 5 patients (61%) said their UC had a negative effect on their confidence at work; however, despite the added difficulties, over three quarters of employed patients (78%) felt their UC had made them better at managing workloads. Physicians appeared to appreciate the negative impact UC has on their patient’s employment, since 65% of them agreed that patients would approach their career or education differently if they did not have UC.

Figure 3.

Work- and education-related actions as a result of ulcerative colitis

Communication between patients and physicians

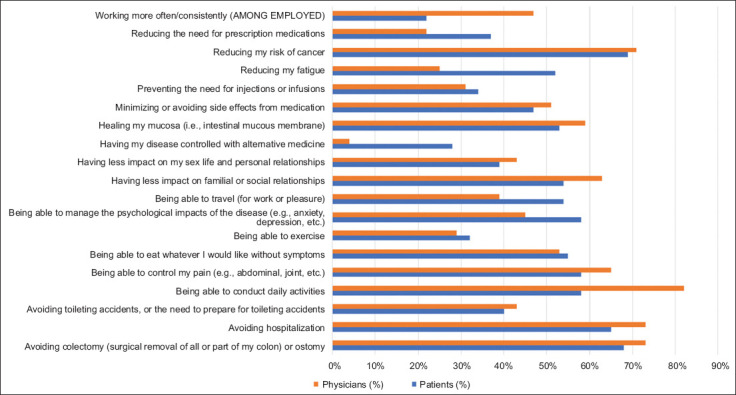

Most patients (98%) felt satisfied with the patient–physician communication. Patients were most satisfied with discussion of disease control and medications (98% and 96%, respectively), while mental/emotional impacts fell lower on their priority list (80%). Though high satisfaction was reported, the same patients still mentioned areas for improvement related to communication. Many of them (60%) agreed they wished they had more time at appointments with their physician, 57% wished they could talk more about goals with the physician, 44% felt uncomfortable talking to their physician about their sex life and personal relationships, while 30% worried that if they asked too many questions they would be seen as a difficult patient, something that would affect the quality of their care. On the other hand, physicians’ perception of patients’ satisfaction with their communication about UC tracked below patient-reported satisfaction (84%). Physicians identified a variety of items that would help improve their patient relationships, such as discussion of whether they took their medication exactly as prescribed (55%) and better access to colonoscopies (43%). Nearly 7 in 10 physicians (69%) reported having taken steps to improve their communication skills with their patients. Physicians appeared fairly aligned on what is most important to patients when managing UC, since reducing cancer risk ranked high (71%) and ability to conduct daily activities ranked first (82%) in the list (Fig. 4). Both patients and physicians in Greece (58% and 63%, respectively) agreed that there is need for more discussion about goals for managing or treating UC. Furthermore, both patients and physicians (57% and 51%, respectively) expressed a desire for greater discussion of patients’ fears about medical treatments. A significant barrier for greater conversations during scheduled appointments was lack of time, since 36% of patients and 35% of physicians agreed that they rarely had time to raise or respond to all questions and concerns. Furthermore, nearly half of the patients (53%) regretted not saying more during appointments.

Figure 4.

Top priorities in ulcerative colitis management for patients and physicians Small base site (n<100); results should be interpreted with caution

Knowledge of disease – patient advocacy groups

Most patients (86%) wished for more information about medications and support when they were first diagnosed. Misconceptions still exist pertaining to inflammation, since 47% of patients stated that if their symptoms were under control there is no active disease or inflammation, 25% were not sure or incorrectly thought that uncontrolled inflammation is not a risk factor for colorectal cancer, while 13% thought that keeping the disease under control does not reduce the risk for long-term complications. More importantly, a third of patients (33%) were not aware that UC may be associated with out-of-gut manifestations, and 25% of physicians did not feel their patients had understood this well. Both patients and physicians agreed on the importance of patients’ associations (91% and 86%, respectively); however, 4 in 5 physicians (80%) wished there were resources they could refer their patients to for more information and support. Finally, on average, physicians only reported recommending these groups to a third of their patients and similarly, despite reported importance, less than half of the patients (45%) had interacted with patients’ organizations in some way. The top type of information patients would be interested in receiving from a patients’ association was how to live better with UC (80%).

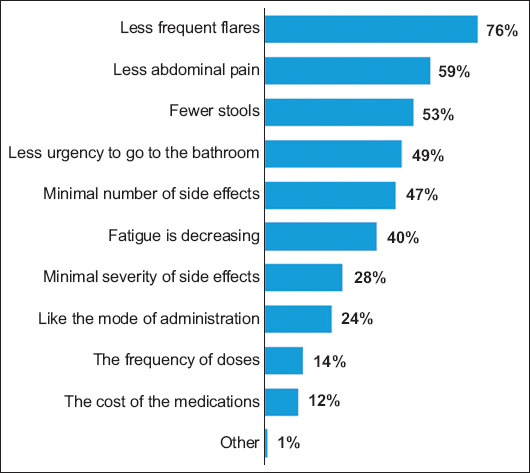

Medication preference and satisfaction

Patients’ satisfaction with current UC medications appeared to be high (92%); however, the physicians’ perspective on what proportion of their patients were satisfied was somewhat lower (69%). Decreased frequency of flares was the top reason for medication satisfaction (76%) (Fig. 5). Half of the patients (51%) wished for earlier discussion of all medication options and physicians wished they had time to do so (61%). Nearly 9 in 10 patients (88%) felt their gastroenterologist was prescribing the very best available medication for their unique experiences; however, 55% of them stated that if the treatment they received made them feel good enough, they did not see a need to consider other treatment options, even if this change might make them feel even better. Nearly 4 in 5 patients (78%) wish they had more medication choices, while daily oral medication was the preferred treatment among most patients (57%) and the physicians agreed (98%). As regards adherence to treatment, a quarter of the patients (25%) hesitated to disclose non-adherence to their physician, while most physicians (94%) believed that more than half of their patients took their medication exactly as prescribed. More than half of the patients (56%) were not aware of the risks of using steroids over the long term, and 2 in 3 patients currently taking steroids (66%) said they were afraid they would immediately flare if they stopped taking them. About 3 in 4 patients (74%) wished they had moved to biologics sooner, while more than 2 in 5 patients (44%) did not know that it is possible for biologics to exhibit a secondary loss of response. Finally, although most patients (68%) believed that the benefit of biologics outweighs the risks, nearly 1 in 5 patients (18%) currently taking a biologic were not happy with this treatment.

Figure 5.

Reason for satisfaction with current treatment for ulcerative colitis

Discussion

The results of this study show encouraging levels of satisfaction among Greek patients with UC, as regards both their perception of being in remission (82%) and their communication with their treating gastroenterologist (98% felt satisfied). Despite these favorable responses, the disease seems to affect patients’ daily life and employment adversely, with 78% reporting that they found their UC to be mentally exhausting. Although remission rates seem high, it has to be noted that remission was self-reported by patients and defined as disease being controlled with few to no symptoms. Equally high remission percentage rates have been reported in other published UC Narrative Surveys [9,10]. Furthermore, in the UC NORMAL Survey the majority of patients (58%) indicated that, for them, remission meant living with UC symptoms, so as mentioned in this paper, patients probably had a lower standard for what remission meant for them personally than physicians [11].

In the present study, the mean time between first experienced symptoms and diagnosis of UC was 0.89 months. This is in accordance with previous studies documenting significant delays between first symptoms and diagnosis in IBD in general and UC in particular [12,13]. In the Swiss IBD cohort study, the median diagnostic delay in patients with UC was 4 months [14], while similar findings have also been presented from a recently published Austrian cohort, where the median diagnostic delay in UC was 3 months (1-10 months) [15].

Back in 2013, our group reported that IBD adversely affected patients’ daily lives, since most patients (55%) had to cancel their participation in social events and felt depressed or disappointed because of the disease [7]. Similar results appear to apply 8 years later, even though today gastroenterologists have more choices available for treating their patients. Considering that 68% of UC patients in Greece feel that the disease impacts their lives negatively, while at the same time 8 of 10 patients (78%) wish they had more medication choices, there is clearly a treatment gap in current UC management that needs to be seriously addressed. Although 68% of all patients believe that the benefit of biologics outweighs the risks, and 7 of 10 patients currently on biologics wished they had moved to this therapy sooner, adherence is still a key issue that affects treatment success. According to our findings, a quarter of patients hesitate to disclose non-adherence to their physician, which emphasizes the need for better patient–physician communication. Medication preference is particularly important, and patients’ choices should be taken into account when we decide about the best medical therapy for them. Patients do seem to have a clear preference for oral administration (57%) and this is also supported by other studies [16-21], something that should be definitely taken into account if adherence to treatment needs to be increased.

In 2013, the vast majority of Greek IBD patients (88%) reported overwhelming support from their family and friends and appeared to be hesitant to participate in patients’ groups. Interestingly, this has not changed over the years, since although 85.1% of patients in the current survey agreed that patients’ associations are important for the management of UC, only 69.9% had interacted with a patients’ association in any way. Although this emphasizes the still strong supporting role of the Greek family for its suffering members, a vital issue in Greek culture, our findings should nevertheless encourage all physicians to provide information on patients’ associations to their patients at an early stage.

Communication is the backbone of chronic disease management, and the present study showed that physicians are fairly aligned on what is most important to patients when managing UC. Previous studies have emphasized the need for symptom control and normalization of quality of life [22,23], and indeed physicians do consider the ability to conduct daily activities as the most desirable treatment goal. It is of interest, though, that patients’ most desirable treatment goals are reducing cancer risk and avoiding colectomy. Many studies have reported on the need for better patient–physician communication [24-28], and indeed a significant percentage of Greek gastroenterologists (69%) report having taken steps to improve their communication skills with their patients. Empowering patients through information and support facilitates shared decision-making and a treat-to-target approach, in which physicians and patients are partners [29].

On the other hand, our results also highlight areas where changes can be made to enhance patient–physician interaction. More time should be allocated during scheduled appointments to discuss UC and treatment options. Most physicians tend to focus on treating the disease rather than treating the patient, and as a consequence not all gastroenterologists discussed lifestyle issues with their patients. It is of interest that 44% of the patients surveyed here were not comfortable discussing their sex life and personal relationships with their physician, results similar to those of previous studies [24,30]. These findings do highlight the importance of implementing multidisciplinary teams for better management of UC patients, with the participation of trained psychologists/psychiatrists. Indeed, 20% of our UC patients participating in this survey were already consulting a psychologist/psychiatrist. The participation of an IBD nurse—which unfortunately is not common practice in Greece—can help with management and improve patient relationships. Apart from that, online forums can provide information and support to patients in addition to those provided by the treating physician.

Our study has several strengths and some limitations. This study provides important data on UC patients’ most common worries and fears. The questionnaire administered to the patients was detailed, and gathered valuable information about patients’ daily quality of life, employment, and mental status. By comparing these results to our previous findings, we had the opportunity to see what changes, if any, our UC patients had experienced regarding their disease management over the years. Also, for the first time, patients’ answers were matched with those given by their physicians, something that adds value to the results. Among the limitations is the fact that the authors were not aware of the criterion on which the original questionnaire was sent out, because the vendor responsible for the execution of the survey classified this information as confidential. Furthermore, voluntary participation creates a response bias and the results from the UC Narrative patient sample survey may therefore not reflect the experiences of the broader UC population. The interpretation of patient survey findings was limited by those patients who self-reported a diagnosis of UC, and by relying upon patients’ accurate recall of UC management and their understanding of the survey questions. Furthermore, disease severity was determined by patient-reported medication history, with no clinical assessment to determine disease activity, while an endoscopic and biochemical assessment to determine disease activity was lacking. Finally, the comparison between patients’ and physicians’ perspectives did not include patients with mild disease, since these patients only made up 20% of the total survey responders.

In conclusion, Greek UC patients appear to be satisfied with their physicians and their disease management. Gaps in patient–physician communication relating to quality of life, emotional, and sexual/relationship concerns should be considered. Allocating more time during scheduled appointments and tackling these challenges can lead to improved patient-to-physician communication and implementation of a shared decision-making approach, thus enhancing patient experience and improving disease outcomes.

Summary Box.

What is already known:

Patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) most often deal with unpredictable, unpleasant and potentially embarrassing gastrointestinal symptoms, in addition to treatment-related side effects

The burden of disease extends far beyond the clinical signs and symptoms, and several studies have shown that patients’ employment opportunities, work productivity and social interaction are disturbed, leading to anxiety and/or depression that in turn affect negatively patients’ quality of life

The recent initiative of the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), the STRIDE-II, has included the absence of disability and the restoration of quality of life as long-term treatment targets in patients with IBD

What the new findings are:

The results of our study show encouraging levels of satisfaction among Greek UC patients as regards both their perception of being in remission (82%) and their communication with their treating gastroenterologist (98% felt satisfied)

UC seems to affect patients’ daily life and employment adversely, with 78% reporting that they found their disease to be mentally exhausting

Gaps in patient–physician communication relating to quality of life, emotional, and sexual/relationship concerns should be considered

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the patients and the physicians involved in the UC Narrative Surveys

Biography

“Evangelismos-Polykliniki” General Hospital of Athens; Pfizer Hellas, Athens, Greece

Footnotes

Supported by: The UC Narrative Surveys were sponsored by Pfizer, Inc.

Conflict of Interest: Anastasia Stefanidou is an employee of Pfizer Hellas. All other authors have no disclosures.

References

- 1.Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389:1756–1770. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32126-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormick JB, Hammer RR, Farrell RM, et al. Experiences of patients with chronic gastrointestinal conditions:in their own words. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:25. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yarlas A, Rubin DT, Panés J, et al. Burden of ulcerative colitis on functioning and well-being:a systematic literature review of the SF-36®health survey. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:600–609. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Regueiro M, Greer JB, Szigethy E. Etiology and treatment of pain and psychosocial issues in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:430–439. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mikocka-Walus A, Knowles SR, Keefer L, Graff L. Controversies revisited:a systematic review of the comorbidity of depression and anxiety with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:752–762. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, et al. International Organization for the Study of IBD. STRIDE-II:an update on the selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE) initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD):determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1570–1583. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viazis N, Mantzaris G, Karmiris K, et al. Hellenic Foundation of Gastroenterology and Nutrition. Inflammatory bowel disease:Greek patients'perspective on quality of life, information on the disease, work productivity and family support. Ann Gastroenterol. 2013;26:52–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghosh S, Sensky T, Casellas F, et al. A global, prospective, observational study measuring disease burden and suffering in patients with ulcerative colitis using the pictorial representation of illness and self-measure tool. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;15:228–237. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubin DT, Hart A, Panaccione R, et al. Ulcerative colitis narrative global survey findings:communication gaps and agreements between patients and physicians. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:1096–1106. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izaa257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molander P, Ylänne K. Impact of ulcerative colitis on patients'lives:results of the Finnish extension of a global ulcerative colitis narrative survey. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:869–875. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2019.1635637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubin DT, Siegel CA, Kane SV, et al. Impact of ulcerative colitis from patients'and physicians'perspectives:Results from the UC:NORMAL survey. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:581–588. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romberg-Camps MJ, Hesselink-van de Kruijs MA, Schouten LJ, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in South Limburg (the Netherlands) 1991-2002:incidence, diagnostic delay, and seasonal variations in onset of symptoms. J Crohns Colitis. 2009;3:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nahon S, Lahmek P, Lesgourgues B, et al. Diagnostic delay in a French cohort of Crohn's disease patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:964–969. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vavricka SR, Spigaglia SM, Rogler G, et al. Swiss IBD Cohort Study Group. Systematic evaluation of risk factors for diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:496–505. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novacek G, Gröchenig HP, Haas T, et al. Austrian IBD Study Group (ATISG) Diagnostic delay in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Austria. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2019;131:104–112. doi: 10.1007/s00508-019-1451-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al Khoury A, Balram B, Bessissow T, et al. Patient perspectives and expectations in inflammatory bowel disease:a systematic review. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;21:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10620-021-07025-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denesh D, Carbonell J, Kane JS, Gracie D, Selinger CP. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) prefer oral tablets over other modes of medicine administration. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;15:1091–1096. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2021.1898944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuoka K, Ishikawa H, Nakayama T, et al. Physician –patient communication affects patient satisfaction in treatment decision making:a structural equation modelling analysis of a web based survey in patients with ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2021;56:843–855. doi: 10.1007/s00535-021-01811-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubinsky MC, Watanabe K, Molander P, et al. Ulcerative colitis narrative global survey findings:the impact of living with ulcerative colitis-patients'and physicians'view. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:1747–1755. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izab016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connor SJ, Sechi A, Andrade M, Deuring JJ, Witcombe D. Ulcerative Colitis Narrative findings:Australian survey data comparing patient and physician disease management views. JGH Open. 2021;5:1033–1040. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagelund LM, Elkjær Stallknecht S, Jensen HH. Quality of life and patient preferences among Danish patients with ulcerative colitis - results from a survey study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36:771–779. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2020.1716704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jelsness-Jørgensen LP, Moum B, Bernklev T. Worries and concerns among inflammatory bowel disease patients followed prospectively over one year. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2011;2011:492034. doi: 10.1155/2011/492034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calvet X, Argüelles-Arias F, López-Sanromán A, et al. Patients'perceptions of the impact of ulcerative colitis on social and professional life:results from the UC-LIFE survey of outpatient clinics in Spain. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1815–1823. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S175026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubin DT, Dubinsky MC, Martino S, Hewett KA, Panés J. Communication between physicians and patients with ulcerative colitis:reflections and insights from a qualitative study of in-office patient-physician visits. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:494–501. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands B, et al. Selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE):determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324–1338. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubin DT, Krugliak Cleveland N. Using a treat-to-target management strategy to improve the doctor-patient relationship in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1252–1256. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai C, Sceats LA, Qiu W, Park KT, Morris AM, Kin C. Patient decision-making in severe inflammatory bowel disease:the need for improved communication of treatment options and preferences. Colorectal Dis. 2019;21:1406–1414. doi: 10.1111/codi.14759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boeri M, Myers K, Ervin C, et al. Patient and physician preferences for ulcerative colitis treatments in the United States. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2019;12:263–278. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S206970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siegel CA. Shared decision making in inflammatory bowel disease:helping patients understand the tradeoffs between treatment options. Gut. 2012;61:459–465. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.López-Sanromán A, Carpio D, Calvet X, et al. Perceived emotional and psychological impact of ulcerative colitis on outpatients in Spain:UC-LIFE survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:207–216. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4363-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.