Abstract

Background:

This study aims to understand how criminal-legal involved women from three U.S. cities navigate different health resource environments to obtain cervical cancer screening and follow-up care.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional study of women with criminal-legal histories from Kansas City KS/MO; Oakland, CA; and Birmingham, AL. Participants completed a survey that explored influences on cervical cancer prevention. Responses from all women with/without up-to-date cervical cancer screening and women with abnormal Pap testing who did/did not obtain follow-up care were compared. Proportions and associations were tested with chi-square or analysis of variance tests. Multivariable regression was performed to identify variables independently associated with up-to-date cervical cancer screening and reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results:

There were n = 510 participants, including n = 164 Birmingham, n = 108 Kansas City, and n = 238 Oakland women. Criminal-legal involved women in Birmingham (71.3%) and Kansas City (68.9%) were less likely to have up-to-date cervical cancer screening than women in Oakland (84.5%, p = 0.01). More women in Birmingham (14.6%) and Kansas City (16.7%) needed follow-up for abnormal Pap than women in Oakland (6.7%, p = 0.003), but there were no differences in follow-up rates. Predictors for up-to-date cervical cancer screening included access to a primary care provider (OR: 3.3, 95% CI: 1.4–7.7), health literacy (OR: 0.3, 95% CI: 0.2–0.7), and health behaviors, including avoiding tobacco (OR: 0.4, 95% CI: 0.1–0.9) and HPV vaccination (OR: 3.4, 95% CI: 1.0–10.9).

Conclusions:

Cervical cancer screening and follow-up varied by study site. The results suggest that patient level factors coupled with the complexity of accessing care in different health resource environments impact criminal-legal involved women's cervical cancer prevention behaviors.

Keywords: cervical cancer prevention, criminal-legal involved women, cervical cancer screening, abnormal Pap follow-up

Introduction

Cervical cancer is a preventable disease, yet women with criminal-legal histories have cervical cancer rates that are four to five times higher than the general population.1,2 The disparate incidence of cervical cancer in the criminal-legal population is largely driven by the higher prevalence of risk factors for cervical dysplasia, including tobacco use, multiple sex partners, and infection with HPV and/or HIV.3 Furthermore, women with criminal-legal histories return to their communities after release from jail or prison with no income, limited health insurance, and the constant threat of reincarceration—all of which make it challenging for these women to seek preventive cervical care.4–6 Consequently, up to 60% of incarcerated women have high grade dysplasia on routine Pap testing, and only 21%–66% of these women obtain recommended follow-up.3,6–8

Women with criminal-legal involvement include women who are living in correctional facilities, supervised under probation, parole, or a community-based monitoring system, as well as women with a history of incarceration and no ongoing legal oversight. Previous investigators have found that cervical cancer prevention behaviors in this population are influenced by individual risk factors, such as sociodemographic variables and health literacy. Less is known about the role of community infrastructure, access to health resources, and health policy in determining whether criminal-legal involved women are able to seek preventive cervical care in their communities.6–12 The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (BMVP) is an expanded version of Andersen's behavioral model that provides a framework for understanding influences on health service utilization and health outcomes among criminal-legal involved populations.13 The model not only describes how predisposing characteristics (e.g., race, age, education), enabling resources (e.g., health insurance), and health needs (e.g., perceived illness and need for medical care) can influence health behaviors and outcomes but also considers the unique vulnerabilities found among criminal-legal involved women such as their mental health history, substance use experience, and history of interpersonal violence.14–17 Thus, the BMVP provides a more comprehensive framework that could have important implications for understanding cervical cancer screening and follow-up care among criminal-legal involved women.

In addition to the characteristics described in the BMVP, an important structural element influencing health care utilization is State-level Medicaid access. Previous investigators found that formerly incarcerated people who obtained Medicaid coverage were more likely to obtain preventive health services in their communities.18 However, eligibility for Medicaid is largely dependent on whether a state elected to expand their Medicaid program through the Affordable Care Act. California is 1 of 39 states that implemented Medicaid expansion, whereas Alabama and Kansas did not; Missouri only recently voted for expansion as of August 2020.19,20 Consequently, up to 31% of nonelderly women in California have obtained health insurance through Medicaid compared to only 15% of women in Alabama and Missouri and 10% of women in Kansas.21 Differences in state-level health policy environments will likely affect rates of cervical cancer screening and follow-up among criminal-legal involved women living in different parts of the United States.22

The purpose of this study was to understand how women with criminal-legal histories from three U.S. cities—Birmingham, AL; Kansas City, KS/MO; and Oakland, CA—maintain their cervical health once they reenter their communities. These sites represent three regions of the United States with varying infrastructures and health care systems, which allow for comparison of cervical cancer screening and follow-up in different resource environments. Using the BMVP as an investigative framework, the primary objective was to compare cervical cancer prevention behaviors in the three study sites, and the secondary objective was to identify predictors of up-to-date cervical cancer screening. The study also included an exploratory objective to identify predictors for follow-up care among criminal-legal involved women with abnormal Pap results. Understanding barriers and facilitators to cervical cancer screening and abnormal Pap follow-up may guide future interventions that aim to reduce cervical cancer disparities in women with criminal-legal histories.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional cohort study of criminal-legal involved women from three U.S. cities. Data were obtained from a survey administered from March 2019 to June 2020 in the first year of an ongoing longitudinal (2019–2024) study with criminal-legal involved women, the Tri-City Cervical Cancer Prevention Study. Criminal-legal involvement was defined as a prior history of incarceration in jail or prison with no further contact with the criminal system, ongoing probation, or ongoing surveillance through a case manager. All participants were women age 18 or older that were identified from preexisting samples of criminal-legal involved women in ongoing separate studies at each location and are now enrolled in the longitudinal Tri-City study. Women in the Kansas City sample were recruited from 3/2019 to 4/2020 at city/county jails and have since been released. The Birmingham participants, recruited 5/2019 to 5/2020, came from an outpatient community corrections facility that provides monitoring and case management services. The Oakland participants were recruited from the County probation office and community settings between 5/2019 and 5/2020, and all had a history of being on probation. By merging three samples, the investigative team was able to capitalize on existing groups of hard to reach women and follow a robust multisite cohort. All who agreed to participate provided informed consent. The Tri-City protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Kansas Medical Center with reliance agreements from the other participating study sites.

Instrument and measures

A 288-item survey informed by the BMVP was developed to investigate cervical cancer prevention behaviors (Fig. 1). To determine whether participants had up-to-date cervical cancer screening and follow-up for abnormal results, the study included open-ended questions that were adapted from the National Cancer Institute Health Information National Trends Survey (NCI HINTS) Cervical Cancer Section and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists (ACOG), American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP), and United States Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines on cervical cancer screening and follow-up.23–25 Up-to-date cervical cancer screening was defined according to ASCCP and USPSTF guidelines: (1) cytology every 3 years in women age 21–29 and (2) cytology every 3 years in women age 30–65 or (3) cytology/HPV cotesting every 5 years in women age 30–65.24–26 This was assessed by asking women multiple-choice questions about the timing of their last Pap and HPV testing. Combined responses that were considered up-to-date for cervical cancer screening included: (1) Pap test “within the past 3 years” for women age 21–29, (2) Pap test “within the past 3 years” for women age 30–65, or (3) Pap test “within the past 5 years” and “yes” to HPV cotesting for women age 30–65. The survey was designed before the 2018 update to USPSTF guidelines that also allows for HPV testing alone every 5 years, so this option was not reflected in the survey responses. Criminal-legal involved women did not have an up-to-date cervical cancer screen if they gave the following responses: (1) “I have never had a Pap test,” (2) “5 or more years ago” since last Pap test, (3) Pap test “within the past 5 years” for women age 21–29, and (4) Pap test “within the past 5 years” and “no” to HPV cotesting for women age 30–65.

FIG. 1.

Behavioral model for vulnerable populations adapted for cervical cancer prevention among community-based criminal legal-involved women.

The second dependent variable, abnormal Pap follow-up, was assessed with open ended questions. Participants were asked, “The last time you had a Pap test, did you get an “abnormal” result? In other words, did they say that they needed you to follow up for more testing?” and “Did you get the recommended follow-up after your Pap test?”23–27 Responses were coded numerically as “yes,” “no,” “don't know or prefer not to answer,” or blank. Coded responses were tabulated, and women who self-reported that they needed follow-up were then stratified according to whether they responded “yes” or “no” for obtaining recommended follow-up.

To identify independent variables that predict up-to-date cervical cancer screening and abnormal Pap follow-up among women with criminal-legal histories, the survey assessed predisposing, enabling, and need factors, as well as related health practices based on the BMVP framework. Variables were selected based on their association with preventive health seeking behaviors in previous studies of women with and without criminal-legal histories. All questions were adapted from validated surveys, including NCI HINTS, and were designed to be population specific and assess needs that are unique to women with a criminal-legal history.23,27–36 See Supplementary Data S1 for additional information on specific measures and scaled items.

The survey was administered via individual telephone or in-person interviews, through a web-based survey sent to the participant's email, or on a hardcopy survey that was mailed to the participant. The participant selected the survey format as per their preference, but all interviews took ∼45 minutes to complete. In Birmingham, 32 women completed the survey via weblink, 57 via phone interview, and 71 via in-person interview. In Kansas City, 43 women completed the survey via weblink, 6 via hardcopy survey, 54 via telephone interview, and 5 women completed in-person interviews. Finally, in Oakland 26 women did telephone interviews and 212 did in-person interviews. Women were offered 50 dollars as compensation for their participation. Oakland women were given cash, and the women in Birmingham and Kansas City were given a Greenphire ClinCard. These differences in compensation were because of existing institutional payment permissions at each study site.

Data interpretation and analysis

A convenience sample was utilized given the challenge of maintaining contact with criminal-legal involved women in community settings. Data on cervical cancer screening history and follow-up were stratified according to study site and summarized using descriptive statistics. Comparisons were made between participants with/without up-to-date cervical cancer screening and with/without follow-up for abnormal Pap results. For these comparisons, categorical variables from the survey were reported as frequencies and analyzed using chi-square test. Continuous data from scaled survey items were reported as means and compared using t-tests or analysis of variance. For each comparison, effect size was calculated, and statistical significance was determined at 0.05 alpha level.

A series of logistic regression models were fitted to identify independent predictors for up-to-date cervical cancer screening. After controlling for study location, those variables with significance in the bivariate analysis were included for comparison in the multivariable model. Odds ratios (ORs) with Wald 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and corresponding p-values were reported, along with a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve to demonstrate the performance of the fitted model at all classification thresholds (true positive rates and false positive rates). There were a total of 344 observations included in the final model, excluding 166 observations that had missing values for responses. The most commonly excluded responses were substance use (14% missing data) and HPV vaccination (12% missing data), but all other data points had ≥95% response rate. The multivariable analysis did not involve a model selection procedure because our exploratory approach aimed to estimate the unique contribution of each variable accounting for other relevant variables. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS Software Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, 2002–2012).

Results

Cervical cancer prevention behaviors by study site

Women were recruited from three ongoing longitudinal studies. Of the women invited, 89% of Birmingham, 91% of Kansas City, and 84% of Oakland women agreed to participate. This gave a total of n = 510 criminal-legal involved women, including n = 164 Birmingham, n = 108 Kansas City, and n = 238 Oakland women. Demographic information and cervical cancer screening history of the cohort are shown in Table 1. Women in Kansas City were younger compared to the other two sites (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.06). The Oakland cohort consisted primarily of Black women, whereas the largest proportions of women in Birmingham and Kansas City were White (p < 0.001, Cramer's V = 0.35). More women in Oakland had health insurance compared to Birmingham or Kansas City (p < 0.001, V = 0.54).

Table 1.

Cervical Cancer Screening History and Results of the Cohort by Study Site, n = 510

| Variable | Total (N = 510) | Birmingham (N = 164) | Kansas City (N = 108) | Oakland (N = 238) | p a | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 42.4 ± 11.7 | 40.6 ± 11.3 | 38.7 ± 9.4 | 45.4 ± 12.2 | <0.001 | 0.060 |

| Race/Ethnicity | <0.001 | 0.354 | ||||

| African American or Black/not Hispanic | 292 (57.3%) | 63 (38.4%) | 37 (34.3%) | 192 (80.7%) | ||

| Caucasian or White/not Hispanic | 157 (30.8%) | 87 (53.0%) | 47 (43.5%) | 23 (9.7%) | ||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 21 (4.1%) | 2 (1.2%) | 8 (7.4%) | 11 (4.6%) | ||

| Other (more than 1 race) | 4 (6.7%) | 7 (4.3%) | 15 (13.9%) | 12 (5.0%) | ||

| Education | 0.374 | 0.065 | ||||

| Less than high school | 122 (23.9%) | 34 (20.7%) | 22 (20.4%) | 66 (27.7%) | ||

| High school or GED | 195 (38.2%) | 68 (41.5%) | 40 (37.0%) | 87 (36.6%) | ||

| Some college or more | 187 (36.7%) | 57 (34.8%) | 45 (41.7%) | 85 (35.7%) | ||

| Health insurance | <0.001 | 0.544 | ||||

| Yes | 345 (67.6%) | 64 (39.0%) | 56 (51.9%) | 225 (94.5%) | ||

| No | 154 (30.2%) | 92 (56.1%) | 51 (47.2%) | 11 (4.6%) | ||

| History of cervical cancer screening | 0.505 | 0.052 | ||||

| Yes | 487 (95.5%) | 153 (93.3%) | 102 (94.4%) | 232 (97.5%) | ||

| No | 12 (2.4%) | 4 (2.4%) | 4 (3.7%) | 4 (1.7%) | ||

| Date of last cervical cancer screen | 0.011 | 0.117 | ||||

| Less than 3 years ago | 391 (76.7%) | 113 (68.9%) | 77 (71.3%) | 201 (84.5%) | ||

| Less than 5 years ago | 40 (7.8%) | 14 (8.5%) | 9 (8.3%) | 17 (7.1%) | ||

| More than 5 years ago | 49 (9.6%) | 25 (15.2%) | 11 (10.2%) | 13 (5.5%) | ||

| Location of cervical cancer screening | <0.001 | 0.241 | ||||

| Hospital-affiliated clinic or doctor's office | 199 (39.0%) | 72 (43.9%) | 45 (41.7%) | 82 (34.5%) | ||

| Community based clinic or health department | 189 (37.1%) | 43 (26.2%) | 25 (23.1%) | 121 (50.8%) | ||

| Emergency room | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | ||

| Jail or prison | 47 (9.2%) | 14 (8.5%) | 15 (13.9%) | 18 (7.6%) | ||

| Other | 20 (3.9%) | 8 (4.9%) | 10 (9.3%) | 2 (0.8%) | ||

| Reason for cervical cancer screening | <0.001 | 0.307 | ||||

| Well woman examination in community | 306 (60.0%) | 69 (42.1%) | 45 (41.7%) | 192 (80.7%) | ||

| Screening at jail/prison | 36 (7.1%) | 13 (7.9%) | 13 (12.0%) | 10 (4.2%) | ||

| Last pap abnormal | 16 (3.1%) | 6 (3.7%) | 8 (7.4%) | 2 (0.8%) | ||

| Prenatal/postpartum care | 41 (8.0%) | 26 (15.9%) | 10 (9.3%) | 5 (2.1%) | ||

| Having another problem/symptom | 37 (7.3%) | 17 (10.4%) | 10 (9.3%) | 10 (4.2%) | ||

| Requested by patient | 27 (5.3%) | 15 (9.1%) | 8 (7.4%) | 4 (1.7%) | ||

| Other | 18 (3.5%) | 5 (3.0%) | 6 (5.6%) | 7 (2.9%) | ||

| Abnormal Pap follow-up needed | 0.003 | 0.156 | ||||

| No | 416 (81.6%) | 121 (73.8%) | 82 (75.9%) | 213 (89.5%) | ||

| Yes | 58 (11.4) | 24 (14.6%) | 18 (16.7%) | 16 (6.7%) | ||

| Abnormal Pap follow-up obtained | 0.144 | 0.259 | ||||

| Yes | 40 (69.0%) | 14 (58.3%) | 12 (66.7%) | 14 (87.5%) | ||

| No | 18 (31.0%) | 10 (41.7%) | 6 (33.3%) | 2 (12.5%) | ||

| Reason for not following up | ||||||

| Follow-up appointment has not occurred yet | 5 (27.8%) | 2 (20.0%) | 2 (33.3%) | 1 (50.0%) | 0.425 | 0.058 |

| Forgot about the appointment | 3 (16.7%) | 2 (20.0%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.255 | 0.073 |

| Didn't have a ride | 1 (5.6%) | 1 (10.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.348 | 0.064 |

| Didn't have health insurance or couldn't afford it | 4 (22.2%) | 2 (20.0%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.145 | 0.87 |

| My drug or alcohol use got in the way | 1 (5.6%) | 1 (10.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.348 | 0.64 |

| Went to jail or prison | 3 (16.7%) | 3 (30.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.041 | 0.112 |

M ± SD; n (column %); ES (Cramer's V for chi-square test or η2 for ANOVA).

p-values <0.05 are in boldface.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; ES, effect size; M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

Regarding cervical cancer screening history, most participants had screening during their lifetime, and there were no significant differences according to site. However, participants in Oakland were more likely to have cervical cancer screening within the last 3 years, whereas a larger proportion of women in Birmingham and Kansas City had their last cervical cancer screen more than 5 years ago (p = 0.01, V = 0.12). We also found that more Oakland women had cervical cancer screening as part of a routine well-woman examination, whereas larger proportions of women in Birmingham and Kansas City had their screening test for other reasons, which included screening in jail/prison, antenatal care, or having another problem or symptom (p < 0.001, V = 0.31). There was a corresponding variation in cervical cancer screening location, as the proportion of women who sought care at a community-based clinic in Oakland was double that of Birmingham or Kansas City (p < 0.001, V = 0.24).

Overall, 11.4% of the cohort reported that they needed follow-up for abnormal Pap results after their last cervical cancer screen. More criminal-legal involved women in Birmingham and Kansas City needed follow-up for abnormal Pap results than women in Oakland (p = 0.003, V = 0.16), although ultimately there were no differences in follow-up rates at the three sites. When asked about reasons for not having follow-up for an abnormal Pap result, more women in Birmingham cited reincarceration (p = 0.04, V = 0.11).

Predictors for up-to-date cervical cancer screening

To identify correlates of up-to-date cervical cancer screening, we compared criminal-legal involved women with and without up-to-date cervical cancer screening using the BMVP framework (Table 2). A larger proportion of Black women had an up-to-date cervical cancer screening compared to other races (p < 0.001, V = 0.25). Women with up-to-date cervical cancer screening were also more likely to have a history of stable housing and reported lower rates of living in jail/prison or on the streets (p = 0.01, V = 0.00). In addition, women with up-to-date cervical cancer screening reported lower belief scores when asked about barriers to screening (p < 0.001, Cohen's d = 0.68), with a lower score indicating that these women perceived less barriers to obtaining cervical cancer screening. There were no significant differences in age, education, employment, number of children, cumulative time in jail, cervical cancer screening knowledge, or psychosocial history between women who did and did not have up-to-date cervical cancer screening.

Table 2.

Comparison of Women With Versus Without Up-to-Date Cervical Cancer Screening Using a Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Population Framework, n = 471

| Variable | N | Pap up to date (N = 403) | Pap not up to date (N = 68) | p a | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predisposing factors | |||||

| Sociodemographics | |||||

| Age | 471 | 42.5 ± 11.6 | 44.8 ± 10.9 | 0.112 | 0.198 |

| Race/Ethnicity | <0.001 | 0.248 | |||

| African American or Black/not Hispanic | 274 | 252 (92.0%) | 22 (8.0%) | ||

| Caucasian or White/not Hispanic | 147 | 107 (72.8%) | 40 (27.2%) | ||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 20 | 18 (90.0%) | 2 (10.0%) | ||

| Other (more than 1 race) | 30 | 26 (86.7%) | 4 (13.3%) | ||

| Education | 0.107 | 0.097 | |||

| Less than high school | 113 | 103 (91.2%) | 10 (8.8%) | ||

| High school or GED | 184 | 157 (85.3%) | 27 (14.7%) | ||

| Some college or more | 174 | 143 (82.2%) | 31 (17.8%) | ||

| Employment | |||||

| Unemployed | 164 | 136 (82.9%) | 28 (17.1%) | 0.234 | 0.000 |

| Full time work | 80 | 72 (90.0%) | 8 (10.0%) | 0.215 | 0.057 |

| Part-time work | 60 | 53 (88.3%) | 7 (11.7%) | 0.513 | 0.030 |

| Illegal work | 55 | 48 (87.3%) | 7 (12.7%) | 0.720 | 0.017 |

| TANF/cash assistance, Supplemental security income, Child support, food stamps, disability | 281 | 243 (86.5%) | 38 (13.5%) | 0.492 | 0.032 |

| Other | 55 | 47 (85.5%) | 8 (14.5%) | 0.981 | 0.000 |

| Number of children | 464 | 0.62 ± 1.04 | 0.48 ± 1.10 | 0.343 | 0.132 |

| Living situation | |||||

| Personal, permanent home | 272 | 238 (87.5%) | 34 (12.5%) | 0.162 | 0.064 |

| Rented room or hotel | 71 | 59 (83.1%) | 12 (16.9%) | 0.522 | 0.000 |

| Friend/family's home | 170 | 139 (82.2%) | 31 (18.2%) | 0.078 | 0.000 |

| Shelter | 98 | 81 (82.7%) | 17 (17.3%) | 0.357 | 0.000 |

| Jail/prison | 78 | 60 (76.9%) | 18 (23.1%) | 0.018 | 0.000 |

| Street, park, or abandoned house/building, vehicle | 83 | 64 (77.1%) | 19 (22.9%) | 0.016 | 0.000 |

| Other | 79 | 63 (79.7%) | 16 (20.3%) | 0.107 | 0.000 |

| Cumulative time spent in city/county jail and state/federal prison | 0.406 | 0.110 | |||

| Less than 1 year | 3 | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | ||

| 1–5 years | 161 | 139 (86.3%) | 22 (13.7%) | ||

| 6–10 years | 38 | 35 (92.1%) | 3 (7.9%) | ||

| More than 10 years | 38 | 35 (92.1%) | 3 (7.9%) | ||

| Health knowledge/beliefs | |||||

| CCS knowledge | 470 | 8.19 ± 1.83 | 8.38 ± 1.50 | 0.344 | 0.108 |

| CCS beliefs | |||||

| Susceptibility | 445 | 2.11 ± 0.87 | 2.25 ± 1.03 | 0.286 | 0.162 |

| Severity of disease | 470 | 3.29 ± 0.93 | 3.35 ± 1.04 | 0.647 | 0.065 |

| Motivations for health | 470 | 3.01 ± 1.08 | 2.90 ± 0.98 | 0.437 | 0.095 |

| Barriers to screening | 469 | 1.87 ± 0.53 | 2.24 ± 0.68 | <0.001 | 0.678 |

| Psychosocial history | |||||

| History of childhood violence or sexual abuse | 0.520 | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 273 | 231 (84.6%) | 42 (15.4%) | ||

| No | 196 | 170 (86.7%) | 26 (13.3%) | ||

| Partner abuse | 0.988 | 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 138 | 118 (85.5%) | 20 (14.5%) | ||

| No | 330 | 282 (85.5%) | 48 (14.5%) | ||

| Neighborhood violence | 0.876 | 0.007 | |||

| Yes | 204 | 175 (85.8%) | 29 (14.2%) | ||

| No | 258 | 220 (85.3%) | 38 (14.7%) | ||

| Enabling factors | |||||

| Personal resources | |||||

| Health insurance | <0.001 | 0.181 | |||

| Yes | 325 | 292 (89.8%) | 33 (10.2%) | ||

| No | 142 | 108 (76.1%) | 34 (23.9%) | ||

| Self-efficacy | 467 | 3.61 ± 0.84 | 2.97 ± 0.80 | <0.001 | 0.765 |

| Community resources | |||||

| Primary care provider | <0.001 | 0.197 | |||

| Yes | 305 | 276 (90.5%) | 29 (9.5%) | ||

| No | 162 | 123 (75.9%) | 39 (24.1%) | ||

| Medical home | <0.001 | 0.203 | |||

| Yes | 393 | 348 (88.5%) | 45 (11.5%) | ||

| No | 70 | 48 (68.6%) | 22 (31.4%) | ||

| Needs | |||||

| Perceived health | |||||

| Quality of life/health | 465 | 2.81 ± 1.01 | 2.57 ± 0.91 | 0.053 | 0.240 |

| Evaluated health | |||||

| Diagnosis of STIs | 0.515 | 0.203 | |||

| Yes | 276 | 239 (86.6%) | 37 (13.4%) | ||

| No | 193 | 163 (84.5%) | 30 (15.5%) | ||

| Diagnosis of mental illness | 0.279 | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 381 | 322 (84.5%) | 59 (15.5%) | ||

| No | 83 | 74 (89.2%) | 9 (10.8%) | ||

| Past abnormal Pap smear | 0.306 | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 161 | 134 (83.2%) | 27 (16.8%) | ||

| No | 309 | 268 (86.7%) | 41 (13.3%) | ||

| Past HPV positive test | 0.369 | 0.203 | |||

| Yes | 49 | 44 (89.8%) | 5 (10.2%) | ||

| No | 414 | 352 (85.0%) | 62 (15.0%) | ||

| Past cancer diagnosisb | 0.569 | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 40 | 33 (82.5%) | 7 (17.5%) | ||

| No | 430 | 369 (85.8%) | 61 (14.2%) | ||

| Health practices | |||||

| Tobacco use | 0.033 | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 337 | 281 (83.4%) | 56 (16.6%) | ||

| No | 134 | 122 (91.0%) | 12 (9.0%) | ||

| Substance use | 0.004 | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 154 | 121 (78.6%) | 33 (21.4%) | ||

| No | 256 | 228 (89.1%) | 28 (10.9%) | ||

| Condom use | 0.717 | 0.038 | |||

| Yes | 165 | 142 (86.1%) | 23 (13.9%) | ||

| No | 182 | 159 (87.4%) | 23 (12.6%) | ||

| Other | 119 | 100 (84.0%) | 19 (16.0%) | ||

| Hormonal birth control use | 0.151 | 0.129 | |||

| Yes | 60 | 55 (91.7%) | 5 (8.3%) | ||

| No | 65 | 54 (83.1%) | 11 (16.9%) | ||

| Other birth control use | 0.388 | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 91 | 78 (85.7%) | 13 (14.3%) | ||

| No | 35 | 32 (91.4%) | 3 (8.6%) | ||

| Received HPV vaccine | 0.041 | 0.099 | |||

| Yes | 66 | 62 (93.9%) | 4 (6.1%) | ||

| No | 359 | 303 (84.4%) | 56 (15.6%) | ||

M ± SD; n (row %); ES (Cramer's V for chi-square test or Cohen's d for t-test); CCS.

Up-to-date pap was defined as per ASCCP/USPSTF guidelines: age 21–29 cytology alone every 3 years, age 30–65 cytology alone every 3 years, or cytology/HPV cotesting every 5 years.

p-values <0.05 are in boldface.

Excluding past diagnosis of cervical cancer.

ASCCP, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology; CCS, cervical cancer screening; USPSTF, United States Preventive Service Task Force.

In the enabling factors domain of the BMVP, criminal-legal involved women with an up-to-date cervical cancer screen were more likely to have health insurance (p < 0.001, V = 0.18), a primary care provider (p < 0.001, V = 0.20), and a medical home (p < 0.001, V = 0.20). Furthermore, criminal-legal involved women with up-to-date cervical cancer screening were more likely to hold a belief that they had the ability to obtain cervical care in their community, indicated by higher self-efficacy scores (p < 0.001, d = 0.77). Finally, women with criminal-legal histories and up-to-date cervical cancer screening reported other positive health practices such as not using tobacco (p = 0.03, V = 0.00) or substances (p = 0.004, V = 0.00) and having a history of HPV vaccination (p = 0.04, V = 0.10). There were no significant associations between criminal-legal involved women's Pap status and their perceived health or past medical history, including history of abnormal Pap, HPV, or sexually transmitted infections.

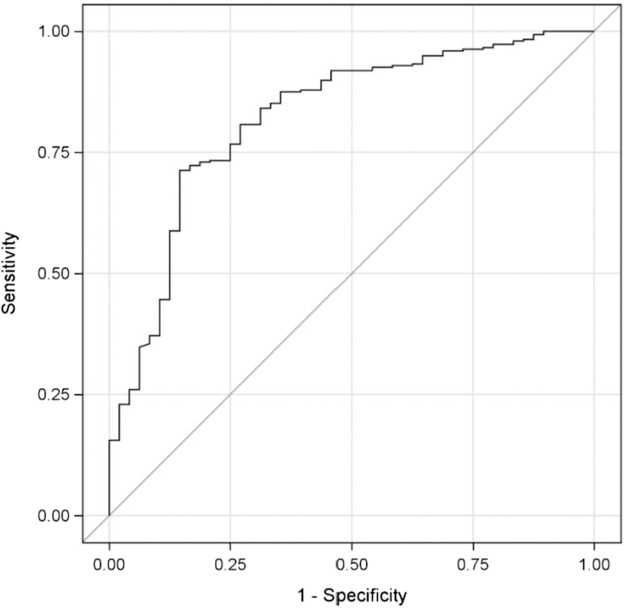

Logistic regression showing factors independently associated with up-to-date cervical cancer screening is shown in Table 3. After controlling for study site, having a primary care provider (OR: 3.38, 95% CI: 1.45–7.86, p = 0.005) and a lower mean belief score for barriers to cervical cancer screening (OR: 0.33, 95% CI: 0.16–0.67, p = 0.002) were significant independent predictors of up-to-date cervical cancer screening. In addition, those women with established positive health practices, including HPV vaccination (OR: 3.37, 95% CI: 1.04–10.91, p = 0.043) and avoiding tobacco (OR: 0.38, 95% CI: 0.15–0.98, p = 0.044), were more likely to engage in timely cervical cancer screening. The overall quality of the model prediction was deemed adequate, with the area of 0.82 under the ROC curve (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Predictors for Up-to-Date Cervical Cancer Screening, n = 471

| Variable | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Citya | ||

| Kansas City | 0.441 | 0.137–1.425 |

| Birmingham | 0.383 | 0.134–1.098 |

| Predisposing factors | ||

| Sociodemographics | ||

| Race | ||

| African American or Black/not Hispanic | 1.891 | 0.426–8.402 |

| Caucasian or White/not Hispanic | 0.961 | 0.223–4.137 |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 1.168 | 0.134–10.149 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 1.220 | 0.755–1.972 |

| Living situation | ||

| Jail/prison | 1.612 | 0.651–3.993 |

| Street, park, or abandoned house/building, vehicle | 0.694 | 0.294–1.634 |

| Health knowledge/beliefs | ||

| CCS beliefs | ||

| Barriers to screening | 0.326 | 0.158–0.673 |

| Enabling factors | ||

| Personal resources | ||

| Health insurance | 1.155 | 0.463–2.881 |

| Self-efficacy | 1.042 | 0.630–1.725 |

| Community resources | ||

| Primary care provider | 3.378 | 1.451–7.863 |

| Medical home | 1.020 | 0.415–2.510 |

| Health practices | ||

| Tobacco use | 0.379 | 0.147–0.975 |

| Substance use | 0.852 | 0.396–1.834 |

| Received HPV vaccine | 3.369 | 1.040–10.910 |

Reference category was Oakland participants. Variables that achieved statistical significance in Table 2 were included in the multivariable analysis.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

FIG. 2.

Receiver operator curve for logistic regression model.

Predictors for abnormal pap follow-up

Variables in the BMVP model that predicted follow-up for abnormal Pap results are shown in Table 4. In the predisposing factors domain of the BMVP, women who obtained follow-up for abnormal Pap results reported lower mean scores for both cervical cancer susceptibility (p = 0.007, d = 0.83) and severity (p = 0.008, d = 0.76), indicating that these women had higher cervical health literacy. Abnormal Pap follow-up did not vary according to age, race, education, employment, number of children, living situation, cumulative time spend in jail/prison, or psychosocial history. The only enabling factor associated with abnormal Pap follow-up was having a primary care provider (p = 0.005, V = 0.37). Health insurance status and having a medical home did not correlate with obtaining recommended follow-up. When looking at health practices, criminal-legal involved women who used hormonal birth control (p = 0.048, V = 0.45) were more likely to obtain follow-up, whereas women who used condoms (p = 0.047, V = 0.33) were not. Interestingly, those criminal-legal involved women with a history of HPV vaccination were less likely to complete follow-up (p = 0.046, V = 0.00). Once again, there were no associations between criminal-legal involved women's follow-up status and their perceived health or past medical history. A multivariable analysis was performed to identify factors independently associated with abnormal Pap follow-up; however, none of the variables had a unique association (data not shown).

Table 4.

Comparison of Women with Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Who Did/Did Not Obtain Follow-Up Care by Study Site Using a Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Population Framework, n = 58

| Variables | N | Obtained follow-up (N = 40) | No follow-up (N = 18) | p a | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predisposing factors | |||||

| Sociodemographics | |||||

| Age | 58 | 42.8 ± 10.6 | 37.7 ± 7.1 | 0.140 | 0.067 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.151 | 0.302 | |||

| African American or Black/not Hispanic | 22 | 17 (77.3%) | 5 (22.7%) | ||

| Caucasian or White/not Hispanic | 30 | 20 (66.7%) | 10 (33.3%) | ||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 4 | 1 (25.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | ||

| Other (more than 1 race) | 2 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Education | 0.298 | 0.206 | |||

| Less than high school | 20 | 16 (80.0%) | 4 (20.0%) | ||

| High school or GED | 21 | 15 (71.4%) | 6 (28.6%) | ||

| Some college or more | 16 | 9 (56.3%) | 7 (43.8%) | ||

| Employment | |||||

| Unemployed | 25 | 16 (64.0%) | 9 (36.0%) | 0.477 | 0.000 |

| Full time work | 12 | 6 (50.0%) | 6 (50.0%) | 0.111 | 0.000 |

| Part-time work | 7 | 5 (71.4%) | 2 (28.6%) | 0.881 | 0.020 |

| Illegal work | 13 | 10 (76.9%) | 3 (23.1%) | 0.545 | 0.080 |

| TANF/cash assistance, Supplemental security income, Child support, Food stamps, disability | 33 | 23 (69.7%) | 10 (30.3%) | 0.890 | 0.018 |

| Other | 8 | 7 (87.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0.222 | 0.160 |

| Number of children | 58 | 0.75 ± 1.06 | 0.72 ± 1.36 | 0.939 | 0.024 |

| Living situation | |||||

| Personal, permanent home | 29 | 19 (65.5%) | 10 (34.5%) | 0.570 | 0.000 |

| Rented room or hotel | 14 | 11 (78.6%) | 3 (21.4%) | 0.372 | 0.117 |

| Friend/family's home | 25 | 20 (80.0%) | 5 (20.0%) | 0.114 | 0.208 |

| Shelter | 16 | 8 (50.0%) | 8 (50.0%) | 0.054 | 0.000 |

| Jail/prison | 22 | 15 (68.2%) | 7 (31.8%) | 0.920 | 0.000 |

| Street, park, or abandoned house/building, vehicle | 10 | 8 (80.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 0.407 | 0.109 |

| Other | 10 | 5 (50.0%) | 5 (50.0%) | 0.154 | 0.000 |

| Cumulative time spent in city/county jail and state/federal prison | 0.735 | 0.197 | |||

| Less than 1 year | 2 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| 1–5 years | 19 | 12 (63.2%) | 7 (36.8%) | ||

| 6–10 years | 7 | 5 (71.4%) | 2 (28.6%) | ||

| More than 10 years | 5 | 3 (60.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | ||

| Health knowledge/beliefs | |||||

| CCS knowledge | 58 | 8.38 ± 1.37 | 8.83 ± 1.25 | 0.218 | 0.343 |

| CCS beliefs | |||||

| Susceptibility | 55 | 2.35 ± 0.94 | 3.14 ± 0.96 | 0.007 | 0.830 |

| Severity of disease | 57 | 3.30 ± 0.94 | 3.99 ± 0.84 | 0.008 | 0.761 |

| Motivations for health | 57 | 3.06 ± 1.14 | 2.64 ± 1.11 | 0.191 | 0.377 |

| Barriers to screening | 57 | 2.10 ± 0.73 | 2.19 ± 0.68 | 0.675 | 0.117 |

| Psychosocial history | |||||

| History of childhood violence or sexual abuse | 0.950 | 0.008 | |||

| Yes | 39 | 27 (69.2%) | 12 (30.8%) | ||

| No | 19 | 13 (68.4%) | 6 (31.6%) | ||

| Partner abuse | 0.838 | 0.027 | |||

| Yes | 26 | 18 (69.2%) | 8 (30.8%) | ||

| No | 30 | 20 (66.7%) | 10 (33.3%) | ||

| Neighborhood violence | 0.088 | 0.228 | |||

| Yes | 24 | 20 (83.3%) | 4 (16.7%) | ||

| No | 32 | 20 (62.5%) | 12 (37.5%) | ||

| Enabling factors | |||||

| Personal resources | |||||

| Health insurance | 0.149 | 0.191 | |||

| Yes | 27 | 21 (77.8%) | 6 (22.2%) | ||

| No | 30 | 18 (60.0%) | 12 (40.0%) | ||

| Self-efficacy | 56 | 3.38 ± 0.91 | 2.98 ± 0.83 | 0.110 | 0.455 |

| Community resources | |||||

| Primary care provider | 0.005 | 0.370 | |||

| Yes | 32 | 27 (84.4%) | 5 (15.6%) | ||

| No | 26 | 13 (50.0%) | 13 (50.0%) | ||

| Medical home | 0.468 | 0.097 | |||

| Yes | 43 | 31 (72.1%) | 12 (27.9%) | ||

| No | 13 | 8 (61.5%) | 5 (38.5%) | ||

| Needs | |||||

| Perceived health | |||||

| Quality of life/health | 56 | 2.39 ± 0.79 | 2.61 ± 1.04 | 0.440 | 0.247 |

| Evaluated health | |||||

| Diagnosis of STIs | 0.739 | 0.045 | |||

| Yes | 38 | 27 (71.1%) | 11 (28.9%) | ||

| No | 18 | 12 (66.7%) | 6 (33.3%) | ||

| Diagnosis of mental illness | 0.307 | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 51 | 34 (66.7%) | 17 (33.3%) | ||

| No | 7 | 6 (85.7%) | 1 (14.3%) | ||

| Past abnormal Pap smear | 0.222 | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 50 | 33 (66.0%) | 17 (34.0%) | ||

| No | 8 | 7 (87.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | ||

| Past HPV positive test | 0.457 | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 18 | 11 (61.1%) | 7 (38.9%) | ||

| No | 38 | 27 (71.1%) | 11 (28.9%) | ||

| Past cancer diagnosisb | 0.943 | 0.010 | |||

| Yes | 13 | 9 (69.2%) | 4 (30.8%) | ||

| No | 44 | 30 (68.2%) | 14 (31.8%) | ||

| Health practices | |||||

| Tobacco use | 0.819 | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 44 | 30 (68.2%) | 14 (31.8%) | ||

| No | 14 | 10 (71.4%) | 4 (28.6%) | ||

| Substance use | 0.201 | 0.328 | |||

| Yes | 21 | 13 (61.9%) | 8 (38.1%) | ||

| No | 28 | 22 (78.6%) | 6 (21.4%) | ||

| Condom use | 0.047 | 0.454 | |||

| Yes | 30 | 18 (60.0%) | 12 (40.0%) | ||

| No | 19 | 17 (89.5%) | 2 (10.5%) | ||

| Other | 8 | 4 (50.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | ||

| Hormonal birth control use | 0.048 | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 11 | 9 (81.8%) | 2 (18.2%) | ||

| No | 8 | 3 (37.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | ||

| Other birth control use | 0.149 | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 16 | 9 (56.3%) | 7 (43.8%) | ||

| No | 3 | 3 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Received HPV vaccine | 0.046 | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 10 | 4 (40.0%) | 6 (60.0%) | ||

| No | 41 | 30 (73.2%) | 11 (26.8%) | ||

M ± SD; n (row %); ES (Cramer's V for chi-square test or Cohen's d for t-test).

p-values <0.05 are in boldface.

Excluding past diagnosis of cervical cancer.

Discussion

Our study provides insight into barriers and facilitators to obtaining preventive cervical care among criminal-legal involved women from three U.S. cities. In our cohort, rates of cervical cancer screening (76.7%) were similar to previous reports of incarcerated women in the United States in which 66%–77% of women had a Pap test within the previous 3 years.3,6,15,16 However, cervical cancer screening varied by study site, which suggests that differences in access to health resources may impact criminal-legal involved women's ability to seek preventive cervical care once they are released from incarceration and reenter their communities. Our study identified independent predictors for up-to-date cervical cancer screening within domains of the BMVP, and there were associations with abnormal Pap follow-up. These variables may serve as potential targets for interventions that aim to mitigate cervical cancer risk among criminal-legal involved women.

The highest rates of cervical cancer screening and follow-up were seen in Oakland, which is not surprising given that California is 1 of 39 states that implemented Medicaid expansion, whereas Alabama and Kansas did not; Missouri only recently voted for expansion as of August 2020.19,20 A recent study of national data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey found that women who live in states without Medicaid expansion have significantly lower odds of receiving Pap testing (OR: 0.87, 95% CI: 0.79–0.95), with an even larger difference seen among the uninsured (OR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.65–0.94).18 Similarly, investigations among underserved populations have found that insurance status also impacts rates of follow-up for abnormal Pap results.37–39 Our study was not designed to formally test the relationship between state-level Medicaid access and cervical cancer prevention behaviors, but we found that the women in sites without Medicaid expansion (Birmingham and Kansas City) were less likely to have up-to-date cervical cancer screening. In addition, we found that health insurance was a facilitator in the BMVP associated with up-to-date cervical cancer screening, although ultimately not an independent predictor. Additional data are needed to further elucidate the relationship between Medicaid access and cervical cancer prevention behaviors in criminal-legal involved women. There are ongoing efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act in the Supreme Court, which may have dire consequences for criminal-legal involved women who rely on Medicaid coverage for access to preventive health care. Reversing Medicaid expansion could limit criminal-legal involved women's ability to seek routine cervical care and potentially widen the cervical cancer disparity gap.

Criminal-legal involved women who had access to a primary care provider were also more likely to report up-to-date cervical cancer screening. When criminal-legal involved women first enter their communities following incarceration they often have no income, scarce housing options, and the challenge of reuniting with their children and families, which make the initial re-entry period a particularly challenging time to prioritize navigating the health care system.4,5,37 Finding a source of routine care is critical, as data show that this is one of the most important predictors for cancer screening use among women, regardless of other socioeconomic factors.40 Criminal-legal involved women rarely receive community health care coordination through jail and instead must establish a provider and medical home through other means.41 Interestingly, the women in Oakland, who had the highest rates of cervical cancer screening and follow-up, also reported obtaining Pap testing as part of routine well-woman examination and sought care at community-based clinics. Public health programs that provide linkages between criminal-legal involved women and providers in their community, along with efforts to coordinate health insurance enrollment, may be a potential target to address barriers to accessing cervical care. This strategy has been effective among other underserved populations.42–44 Given that several women cited reincarceration as a barrier to completing abnormal Pap follow-up, another potential strategy to increase preventive cervical care among criminal-legal involved women would be to expand cervical health care programs in jail and/or prison settings. Previous authors have found that criminal-legal involved women had increased adherence to abnormal pap follow-up recommendations when colposcopy was available within jail or prison facilities.7

When looking at predisposing factors in the BMVP, we found that criminal-legal involved women's cervical cancer beliefs were associated with cervical cancer screening, which highlights the importance of cervical health literacy as a facilitator for preventive cervical care. In previous work by the authors, incarcerated women with up-to-date Pap testing had lower (more positive) scores for cervical cancer screening beliefs, and the current study confirmed this finding as an independent predictor.15,45 There was also an association between cervical health beliefs and abnormal Pap follow-up in the bivariate analysis, although health beliefs were ultimately not an independent predictor. Additional health practices independently associated with cervical cancer screening were avoidance of tobacco and HPV vaccination. Taken together, these findings suggest that when women with criminal-legal histories feel empowered to navigate the health care system and access routine preventive care, they are more likely to have visits that put them in contact with health care system which results in positive health behaviors, including routine, timely cervical cancer screening.

The major strength of the current study is that it is one of the first investigations to provide data from a multisite cohort of demographically diverse women with criminal-legal histories using the BMVP as a theoretical framework. Providing data from cities with different health resource environments allows us to investigate the interactions of policy, community, and patient-level factors across study sites, accounting for variation in cities and increasing generalizability to other urban settings. An additional strength is that our data were drawn from women who are living outside of the carceral setting, which is rare in public health research given the challenges of maintaining contact with criminal-legal involved women.46 The primary limitation is that the data set was collected over 15 months, so we may not know which women were “due” for screening and received care for abnormal results since we only followed up for a limited time. A longitudinal data set would provide a more comprehensive picture of cervical cancer prevention over time, which is the aim of our ongoing study with this cohort. The self-reported Pap history data may be limiting, although previous studies using self-reported data have shown high accuracy compared to validated test results among criminal-legal involved women.47

Conclusions

These data show that differences in health resource environments will influence cervical cancer prevention behaviors among criminal-legal involved women. Using the BMVP framework, we provide a comprehensive assessment that addresses gaps in what we know about the barriers that determine whether criminal-legal involved women obtain timely cervical cancer screening and follow-up care. Our data demonstrate that health insurance policies, access to community providers, and individual differences in health behaviors and health beliefs will all influence cervical cancer screening and follow-up care among criminal-legal involved women. Therefore, to truly address the disparate cervical cancer incidence among criminal-legal involved women, we must think beyond each woman's individual risk and consider the broader context of how these women obtain health insurance coverage and access to a regular source of care once they reenter their communities.

Supplementary Material

Authors' Contributions

C.S.: data interpretation, writing—original draft, writing—review, and editing; J.Lee: conceptualization, formal analysis, data analysis and data interpretation, writing—review, and editing; J. Lorvick: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review, and editing; M.C.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review, and editing; K.C.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review, and editing; S.S.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review, and editing; A.E: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review, and editing; MR: supervision, funding acquisition, conceptualization, methodology, writing—review, and editing.

Disclaimer

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01CA226838 to PI Ramaswamy.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Binswanger IA, Krueger PM, Steiner JF. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009;63:912–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moghissi KS, Mack HC. Epidemiology of cervical cancer: Study of a prison population. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1968;100:607–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Binswanger IA, Mueller S, Clark CB, et al. Risk factors for cervical cancer in criminal justice settings. J Womens Health 2011;20:1839–1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gonnerman J. Life on the outside: The prison odyssey of Elaine Bartlett. 1st ed. New York, NY: Picador, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Colbert AM, Goshin LS, Durand V, et al. Women in transition: Experiences of health and health care for recently incarcerated women living in community corrections facilities. Res Nurs Health 2016;39:426–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brousseau EC, Ahn S, Matteson KA. Cervical cancer screening access, outcomes, and prevalence of dysplasia in correctional facilities: A systematic review. J Womens Health 2019;28:1661–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clarke J, Phipps M, Rose J, et al. Follow-up of abnormal pap smears among incarcerated women. J Correct Health Care 2007;13:22–26. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martin, R, Hislop T, Moravan V, et al. Three-year follow-up study of women who participated in a cervical cancer screening intervention while in orison. Can J Public Health 2004;99:262–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Correctional populations in the United States, 2017–2018. Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2020. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=7026 Accessed September 30, 2020.

- 10. Staton M, Leukefeld C, Webster JM. Substance use, health, and mental health: Problems and service utilization among incarcerated women. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 2003;47:224–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Narevic E, Garrity TF, Schoenberg NE, et al. Factors predicting unmet health services needs among incarcerated substance users. Subst Use Misuse 2006;41:1077–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Plugge E, Fitzpatrick R. Factors affecting cervical screening uptake in prisoners. J Med Screen 2004;11:48–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? J Health Soc Behav 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: Application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res 2000;34:1273–1302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kelly PJ, Allison M, Ramaswamy M. Cervical cancer screening among incarcerated women. PLoS One 2018;13:e0199220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ramaswamy M, Lee J, Wickliffe J, et al. Impact of a brief intervention on cervical health literacy: A waitlist control study with jailed women. Prev Med Rep 2017;6:314–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ramaswamy M, Kelly PJ, Koblitz A, et al. Understanding the role of violence in incarcerated women's cervical cancer screening and history. Women Health 2011;51:423–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sabik LM, Tarazi WW, Bradley CJ. State Medicaid expansion decisions and disparities in women's cancer screening. Am J Prev Med 2015;48:98–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision. KFF. Available at: https://www.kff.org/health-reform Accessed October 5, 2020.

- 20. United States Census Bureau. State-by-State health Insurance Coverage in 2018. Available at: https://www.census.gov/library/stores/state-by-state-health-insurance-coverage Accessed October 5, 2020.

- 21. Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid's Role for Women. KFF. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/medicaids-role-for-women Accessed July 1, 2021.

- 22. Guyer J, Serafi K, Bachrach D, et al. State strategies for establishing connections to health care for justice-involved populations: The central role of medicaid. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2019;2019:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. National Cancer Institute. Health Information National Trends Survey, Methodology Reports. Available at: https://hints.cancer.gov/data/methodology-reports.aspx Accessed September 29, 2020.

- 24. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists. Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Test Results. Available at: https://www.acog.org/Patients/FAQs/Abnormal-Cervical-Cancer-Screening-Test-Results Accessed October 5, 2020.

- 25. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Cervical Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2018;320:674–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Perkins RB, Guido RS, Castle PE, et al. 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2020;24:102–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. National Cancer Institute. Health Information National Trends Survey. NIH. Available at: https://hints.cancer.gov/instrument.aspx Accessed September 29, 2020.

- 28. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O'Brien CP. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: The Addiction Severity Index. J Nerv Ment Dis 1980;168:26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fernández ME, Gonzales A, Tortolero-Luna G, et al. Effectiveness of Cultivando la Salud: A breast and cervical cancer screening promotion program for low-income Hispanic women. Am J Public Health 2009;99:936–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li XQ, et al. HITS: A short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam Med 1998;30:508–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Walsh CA, MacMillan HL, Trocmé N, et al. Measurement of victimization in adolescence: Development and validation of the Childhood Experiences of Violence Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl 2008;32:1037–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hogenmiller JR, Atwood JR, Lindsey AM, et al. Self-efficacy scale for Pap smear screening participation in sheltered women. Nurs Res 2007;56:369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mays G. National Longitudinal Survey of Public Health Systems Instrument, 2012. Public Health PBRN. Available at: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.874.4274&rep=rep1&type=pdf Accessed September 29, 2020.

- 34. Ramaswamy M, Chen HF, Cropsey KL, et al. Highly effective birth control use before and after women's incarceration. J Womens Health 2015;24:530–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. University of Pennsylvania. Downloadable Instrument & Scoring: Risk Assessment Battery. U Penn. Available at: www.med.upenn.edu/hiv/rab_download.html Accessed September 29, 2020.

- 36. Guvenc G, Akyuz A, Açikel CH. Health belief model scale for cervical cancer and Pap smear test: Psychometric testing. J Adv Nurs 2011;67:428–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kelly PJ, Hunter J, Daily EB, et al. Challenges to Pap smear follow-up among women in the criminal justice system. J Community Health 2017;42:15–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Peterson NB, Han J, Freund KM. Inadequate follow-up for abnormal Pap smears in an urban population. J Natl Med Assoc 2003;95:825–832. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Eggleston KS, Coker AL, Das IP, et al. Understanding barriers for adherence to follow-up care for abnormal pap tests. J Womens Health 2007;16:311–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Selvin E and Brett KM. Breast and cervical cancer screening: Sociodemographic predictors among White, Black, and Hispanic women. Am J Pub Health 2003;93:618–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Patel K, Boutwell A, Brockmann BW, et al. Integrating correctional and community health care for formerly incarcerated people who are eligible for Medicaid. Health Affairs 2014;33:468–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Engelstad LP, Stewart SL, Nguyen BH, et al. Abnormal Pap smear follow-up in a high-risk population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2001;10:1015–1020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bharel M, Santiago ER, Forgione SN, et al. Eliminating health disparities: Innovative methods to improve cervical cancer screening in a medically underserved population. Am J Public Health 2015;105 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S438–S442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ely GE, White C, Jones K, et al. Cervical cancer screening: Exploring Appalachian patients' barriers to follow-up care. Soc Work Health Care 2014;53:83–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ramaswamy M, Kelly PJ. “The Vagina is a Very Tricky Little Thing Down There”: Cervical Health Literacy among Incarcerated Women. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2015;26:1265–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chandler R, Gordon MS, Kruszka B, et al. Cohort profile: Seek, test, treat and retain United States criminal justice cohort. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2017;12:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Webb S, Kelly PJ, Wickliffe J, et al. Validating self-reported cervical cancer screening among women leaving jails. PLoS One 2019;14:e0219178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.