Abstract

Purpose

The specific underlying mechanisms supporting the association between erectile dysfunction (ED) and premature ejaculation (PE) are still not completely clarified. To summarize and discuss all available data supporting the relationship between PE and ED.

Methods

A comprehensive narrative review was performed. In addition, to better clarify the specific factors underlining ED and PE, a meta-analytic approach of the selected evidence was also performed. In particular, the meta-analytic method was selected in order to minimize possible sources of bias derived from a personal interpretation of the data.

Results

Current data confirm the close association between ED and PE and the bidirectional nature of their relationship. In particular, PE was associated with a fourfold increased risk of ED independently of the definition used. In addition, the risk increased in older patients and in those with lower education, and it was associated with higher anxiety and depressive symptoms. Conversely, ED-related PE was characterized by lower associations with organic parameters such as diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia and with smoking habit. Finally, when ED was defined according to the International Index of Erectile Function questionnaire, the presence of a stable relationship increased the risk.

Conclusions

ED and PE should be considered in a dimensional prospective way considering the possibility that both clinical entities can overlap and influence each. Correctly recognizing the underlying factors and sexual complaint can help the clinician in deciding the more appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic work-up.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40618-022-01793-8.

Keywords: Premature ejaculation, Erectile dysfunction, Couple, Sexual desire, PDE5i

Introduction

Erectile dysfunction (ED) and premature ejaculation (PE) are frequently reported as the most common male sexual problems observed in the general population [1–4]. In particular, PE has been considered for a long time the most prevalent type of male sexual dysfunction occurring in around 30% of men aged 40–80 years [5]. However, it is important to recognize that there is a huge difference in the reported prevalence of PE worldwide ranging from 3% to more than 30% [2, 6]. The latter represents the result of the use of different PE definitions [6]. According to the International Society of Sexual Medicine (ISSM), three main aspects should be considered when defining PE: latency time (LT), inability to control and distress about the condition [7]. The 1-min criterion for life-long and 2-min threshold for acquired PE were introduced by ISSM a long time ago [7]: Similar considerations have been more recently released by the European Association of Urology (EAU; [8]) and by the Italian Society of Andrology and Sexual Medicine (SIAMS; [1]). Conversely, the American Psychiatric Association, although it has recognized the LT of 1 min, it did not specifically recognize the difference between life-long and acquired PE [9], whereas the World Health Organization (ICD-11) did not clarify a latency criterion (https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f361151087). Finally, emerging evidence supports the necessity of extending the LT from 1 to 2 min with a limited difference between acquired and life-long PE [6, 10]. The method used to quantify LT constitutes another source of bias. A huge disparity in the prevalence of PE has been recognized when stopwatch intraejaculatory latency time (IELT) has been compared to self-reported PE [6, 11]. To overcome all these problems, the concepts of variable PE and subjective PE have been proposed [12]. The real clinical significance of these new entities has not yet been universally recognized [6]. Besides LT, personal bother and distress represent other crucial points to adequately consider in subjects reporting PE. Data from the European Male Aging Study (EMAS), a survey of community-dwelling men, involving 2888 subjects from 8 countries, recently showed that although 30.8% of subjects reported PE, only 7.3% declared being distressed about it [5]. Interestingly, the same study documented that the increased level of distress was associated with a progressive worsening of sexual functioning and higher risk of ED [5]. Accordingly, only a minority of the patients consulted exclusively for PE, whereas the vast majority of them approached medical consultation only when ED was associated with PE [5, 13]. In a previous meta-analysis of the available data, a bidirectional relationship between the two clinical conditions was identified since PE subjects reported an up to four-fold increased risk of ED but subjects with ED themselves declared lower IELT when compare to those without ED [2]. Interestingly, a cross-sectional study performed between 2014 and 2020 and including 1,893 subjects with ED and 483 with PE concluded that both conditions predispose patients to the other. Although acquired PE is more frequently associated with ED when compared to life-long PE, around 77% of patients stated that ED occurred as a consequence of PE.

Despite this evidence, the specific underlying mechanisms supporting the association between ED and PE are far from having been elucidated. The aim of the present study is to summarize and critically analyze available data supporting the relationship between PE and ED. Possible differences between acquired and life-long PE will be also analyzed.

Methods

A comprehensive narrative review was performed using Medline, Embase and Cochrane search and including the following words: (("premature ejaculation"[MeSH Terms] OR ("premature"[All Fields] AND "ejaculation"[All Fields]) OR "premature ejaculation"[All Fields]) AND ("erectile dysfunction"[MeSH Terms] OR ("erectile"[All Fields] AND "dysfunction"[All Fields]) OR "erectile dysfunction"[All Fields])) AND (english[Filter])). Publications from January 1, 1969 up to December the 31st, 2021 were included.

In particular, to better clarify the specific factors underlining ED and PE, an updated revision of a previously published meta-analysis [2]—evaluating the relationship between PE and ED—was also performed. The meta-analytic method was selected to minimize possible sources of bias derived from a personal interpretation of the data.

Recommendations from available guidelines

Several guidelines specifically addressing the diagnosis and management of PE are available [1, 4, 10, 14]. In addition, quite recently an updated version for some these recommendations has been published (Table 1). The first version of the ISSM guidelines, published after the introduction of the ISSM definition of life-long and acquired PE [7], emphasized the possible association between ED and PE supporting the use of ED treatments with PDE5i in patients with PE and comorbid ED. At that time, further evidence-based research was advocated [7]. In the updated version of the ISSM guidelines published 4 years later, in 2014, reliable evidence suggesting the treatment of PE and comorbid ED with ED pharmacotherapy was recognized (see Table 1; [14]). More recently, the recommendation released from the SIAMS suggests ruling out ED in all patients complaining of PE since a bidirectional relationship between the two clinical conditions has been observed (see below; [1]). Similar recommendations have been more recently released from the EAU and the Sexual Medicine Society of North American (AUA/SMSNA; [4, 10], see also Table 1). All societies also agree that, particularly when ED is comorbid, the use of ED treatment and PDE5i, in particular, can also improve PE.

Table 1.

Mai recommendations regarding the relationship between premature ejaculation (PE) and erectile dysfunction (ED) as derived from International Societies

| Parameter | Society | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Shindel et al., 2021 | AUA/SMSNA | Clinicians should treat comorbid ED in patients with PE according to the AUA Guidelines on ED |

| Salonia et al., 2021 | EAU | Treat ED, other sexual dysfunction, or genitourinary infection (eg, prostatitis) first |

| Sansone et al., 2020 | SIAMS |

We recommend investigating the presence of other sexual comorbidities, particularly ED, in all patients with PE We recommend treating ED before PE in patients with both symptoms |

| Althoff et al., 2014 | ISSM |

While ED is unlikely as a comorbidity or etiological factor for life-long PE, there are data to support that acquired PE is associated with ED There is reliable evidence to support the treatment of PE and comorbid ED with ED pharmacotherapy |

ISSM, International Society for Sexual Medicine; SIAMS, Italian Society of Andrology and Sexual Medicine; EAU, European Association of Urology; AUA/SMSNA, Sexual Medicine Society of North American

Updated meta-analysis on the relationship between PE and ED

Overall, 27 studies including 62,809 subjects with a mean age of 45.2 ± 9.5 years were included in the analysis ([5, 15–41], Table 2). Among them 13,026 (20.7%) reported PE which was defined according to different criteria. The characteristics of the retrieved trials are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the clinical studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study | Age (years) | High level education (%) | Stable relationship (%) | Depression (%) | Anxiety (%) | DM (%) | Hypertension (%) | Dyslipidemia (%) | PE definition | Acquired PE (%) | ED definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Sakka et al., 2003 [13] | 53.4 | 58.6 | 91.3 | – | – | 100 | – | – | Self-reported | 40 | IIEF-EFD |

| Basile Fasolo et al., 2005 [16] | 49.1 | 18.7 | 68.0 | – | – | 6.2 | 17.5 | 8.8 | DSM IV | 69.8 | Self-reported |

| Laumann et al., 2005 [17] | 55.5 | 31.2 | 83.9 | – | – | 10.9 | 22.4 | - | Self-reported | – | Self-reported |

| Porst et al., 2007 [18] | 41.6 | – | 80.5 | 14.2 | 15.5 | 7.8 | 22.2 | 20.1 | Self-reported | 34.6 | Self-reported |

| El Sakka et al., 2008 [19] | 56.8 | – | – | – | – | 78.2 | 34.5 | 36.9 | DSM IV | 100 | IIEF-EFD |

| Malavige et al., 2008 [20] | 55.6 | – | – | – | – | 100 | 41.5 | – | DSM IV | – | IIEF-5 |

| McMahon et al., 2009 [21] | 33.2 | – | 100 | – | – | – | – | – | ISSM | 0 | IIEF-5 |

| Liang et al., 2010 [22] | 33.8 | – | 100 | – | – | – | – | – | ISSM | – | IIEF-5 |

| Son et al., 2010 [23] | 35.5 | 66.5 | 70.2 | – | – | – | – | – | DSM IV | – | IIEF-EFD |

| Vakalopoulos et al., 2011 [24] | 29.8 | 72.6 | 29.6 | – | 32.8 | – | – | – | ISSM | 35 | Self-reported |

| Tang et al., 2011 [25] | 46.0 | – | 80.7 | 2.9 | 9.2 | 28.0 | 37.7 | 30.4 | PEDT | - | IIEF-5 |

| McMahon et al., 2012 [26] | 18–65 | 40 | 69.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 14.0 | 10.0 | PEDT | 49 | IIEF-5 |

| Shaeer et al., 2012 [27] | 35.2 | – | – | 20.6 | 7.1 | 6.6 | 8.1 | - | Self-reported | 43.7 | IIEF-5 |

| Shaeer et al., 2013 [28] | 52.4 | 37.6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ISSM | – | IIEF-5 |

| Lee et al., 2013 [29] | – | 55.7 | 81.2 | 34.0 | 34.0 | 5.7 | 13.5 | 5.9 | PEDT | – | IIEF-5 |

| Gao et al., 2013 [38] and 2014 [41] | 33.7 | 33.7 | – | 4.6 | 12.0 | – | – | – | Self-reported | 18.8 | IIEF-5 |

| Maseroli et al., 2015 [32]* | 60.1 | 30.4 | 95.1 | 17.6 | – | 4.0 | 29.2 | 10.2 | Self-reported | – | Self-reported |

| Brody et al., 2015 | 42.8 | – | – | – | – | - | - | - | Self-reported | – | IIEF-5 |

| Mourikis et al., 2015 | 35.9 | – | 63.5 | – | – | – | – | – | DSM-IV | – | IIEF-15 |

| Salama et al., 2017* | 53.1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | PEDT | – | IIEF-5 |

| Salama et al., 2017** | 53.8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | PEDT | – | IIEF-5 |

| Zamree et al., 2018 | 46.3 | 67.7 | 100 | – | – | – | – | – | PEDT | 15.9 | IIEF-5 |

| Song et al., 2019 | – | 87.0 | 65.9 | 4.8 | – | 8.4 | 19.2 | – | Self-reported | – | IIEF-5 |

| Tsai et al., 2019 | 41.0 | 61.4 | 72.1 | 30.9 | 29.1 | 4.4 | 1.9 | – | PEDT | – | IIEF-5 |

| Zhang et al., 2019 | 33.2 | 56.3 | – | – | – | 3.1 | 5.6 | – | PEDT | – | IIEF-5 |

| Chin et al., 2021 | 53.4 | – | – | – | – | 26.8 | 31.7 | 49.6 | PEDT | 18 | IIEF-5 |

| Corona et al., 2021 | 58.9 | – | 92.2 | – | – | 6.4 | 27.9 | – | EMAS-SFQ | – | EMAS-SFQ |

| Mohamad et al., 2021 | 39.7 | – | 100 | – | – | 0 | – | – | PEDT | – | IIEF-EFD |

IIEF, International Index of Erectile Function; EFD, Erectile Function Domain; PEDT, Premature Ejaculation Diagnostic Tool; ISSM, International Society for Sexual Medicine; DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th Edition Text Revised; DM, diabetes mellitus, PE, premature ejaculation

* Florentine Centre of the European Male Aging Study was considered. * MetS, **no MetS

ED risk in patients with PE

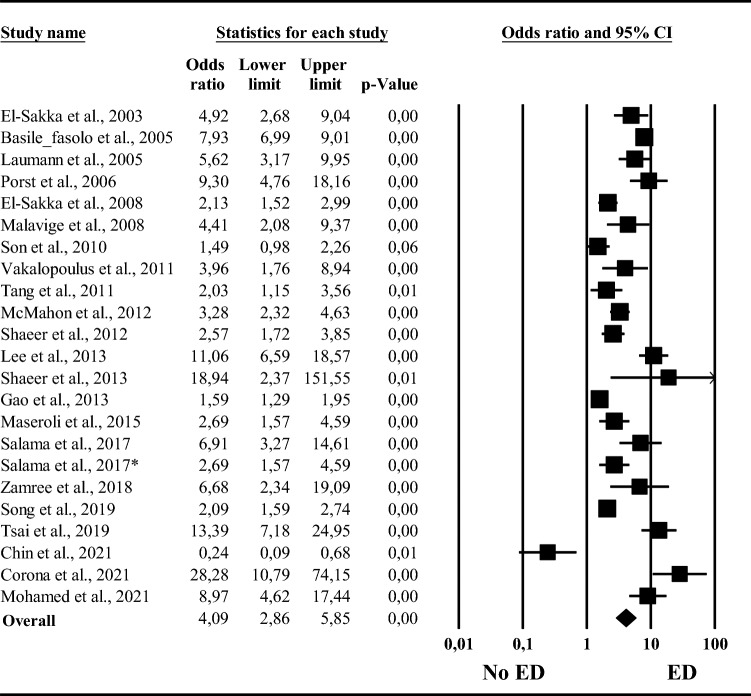

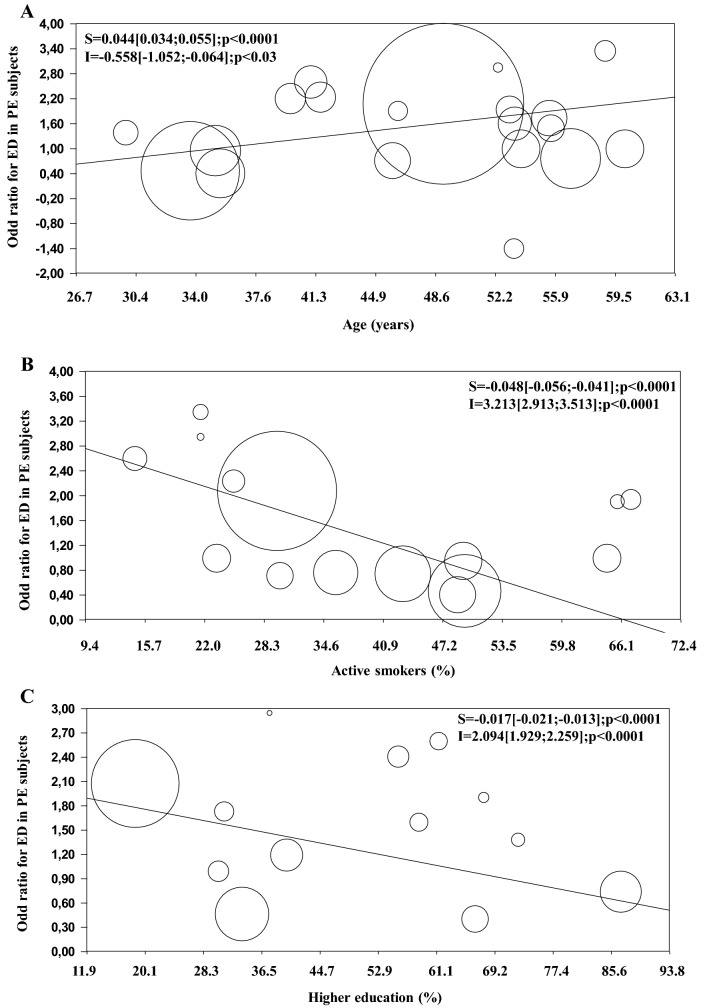

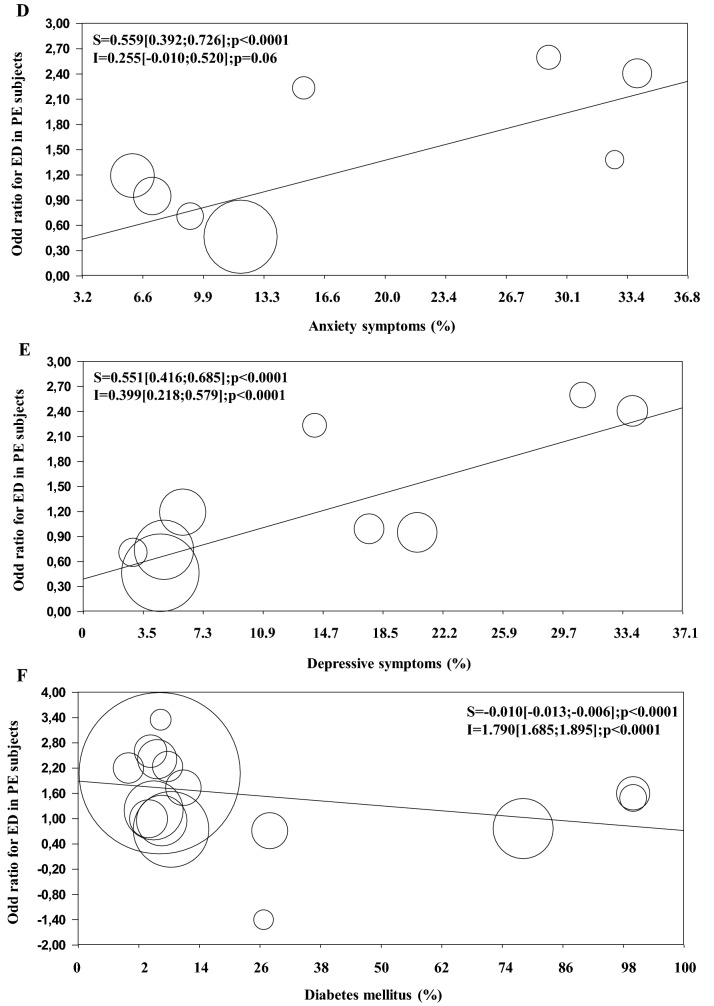

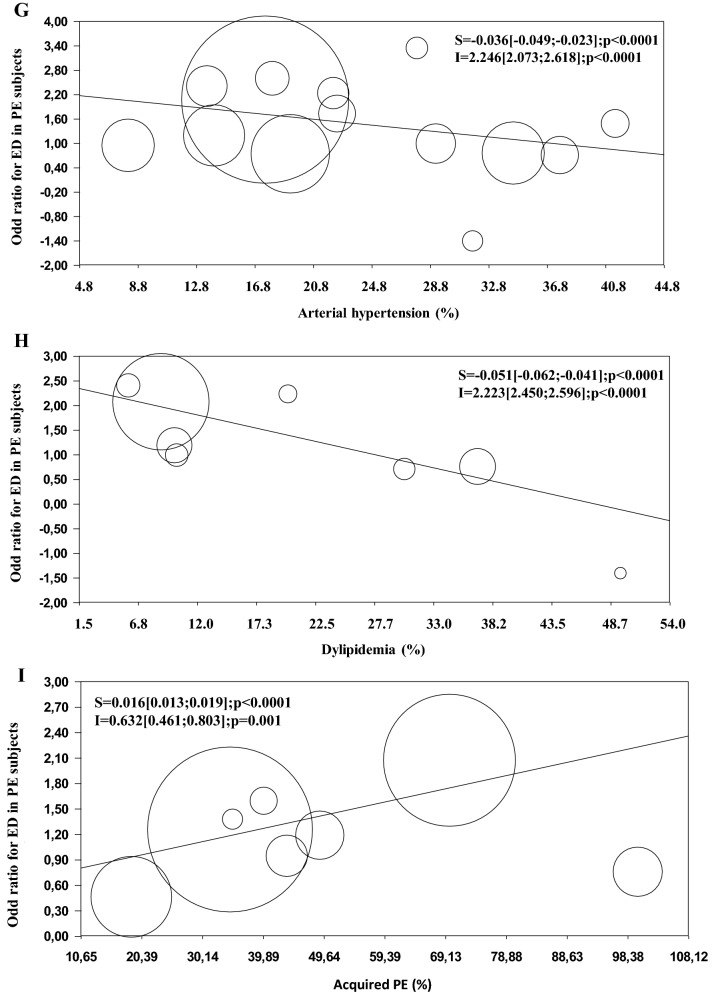

I2 in trials assessing the risk of ED related to PE was 93.7; p < 0.0001. Funnel plot and Begg adjusted rank correlation test (Kendall’s τ: 0.27; p = 0.08) suggested no major publication bias. Presence of PE, however defined, was associated with an up to six-fold increased risk of ED (Fig. 1). The data were confirmed even when different PE definitions were considered (OR = 4.04 [2.50; 6.55] vs. 4.16 [2.25; 7.70] vs. 3.25 [1.25; 8.44] for self-reported, premature ejaculation diagnostic tool (PEDT) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) definition respectively; p = NS among groups). Similarly, no differences were observed when self-reported ED was compared to the IIEF-derived definition (OR = 5.51 [3.46; 8.77] vs. 3.73 [2.59; 5.36]; Q = 1.69; p = 0.19). Meta-regression analysis was performed to identify possible determinants of ED-related PE. The risk of ED in PE subjects was higher in older individuals and inversely related to smoking habit and level of education (Fig. 2A–C). Furthermore, anxiety as well as depressive symptoms were significantly associated with a higher risk of ED (Fig. 2D, E). Conversely, associated morbidities including diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension and dyslipidemia attenuated the risk of ED (Fig. 2F–H). Finally, the risk of ED was higher in those studies reporting a higher proportion of patients declaring an acquired PE problem (Fig. 2I). All these associations were confirmed even after the adjustment for age (Table 3). However, when only those studies performed in clinical settings or those using the IIEF questionnaire for ED definition were considered the association between associated morbidities and risk of ED was not confirmed (not shown). Finally, a direct association between stable couple relationship and PE-related risk of ED was observed only when IIEF-defined ED was analyzed (S = 0.034[0.020;0.048] and I = − 1.329 [− 2.398; − 0.259]; both p < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Odds ratio (95% CI) for erectile dysfunction (ED)-related to premature ejaculation (PE)

Fig. 2.

Influence of age (A), smoking habit (B), education (C), anxiety (D) and depressive (E) symptoms, diabetes mellitus (F), hypertension (G), dyslipidaemia (H) and prevalence of acquired premature ejaculation (I; PE) on PE-related risk of erectile dysfunction (ED). The size of the circles reflects the sample dimension

Table 3.

Relationship between premature ejaculation-related risk of erectile dysfunction and several parameters

| Parameter | Adj r | p |

|---|---|---|

| Level of education | − 0.043 | < 0.0001 |

| Smoking habit | − 0.442 | < 0.0001 |

| Anxiety symptoms | 0.326 | < 0.0001 |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.591 | < 0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | − 0.384 | < 0.0001 |

| Hypertension | − 0.62 | < 0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | − 0.581 | < 0.0001 |

| Acquired ejaculatory problem | 0.371 | < 0.0001 |

Data are derived from alternative multivariate analyses after the adjustment for age

IIEF parameters

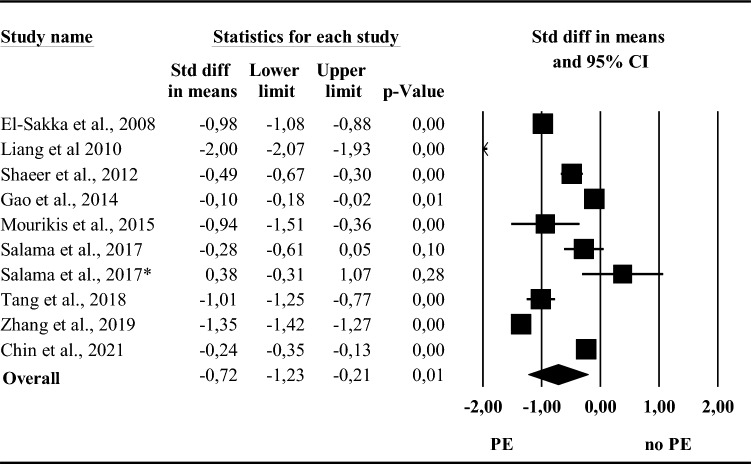

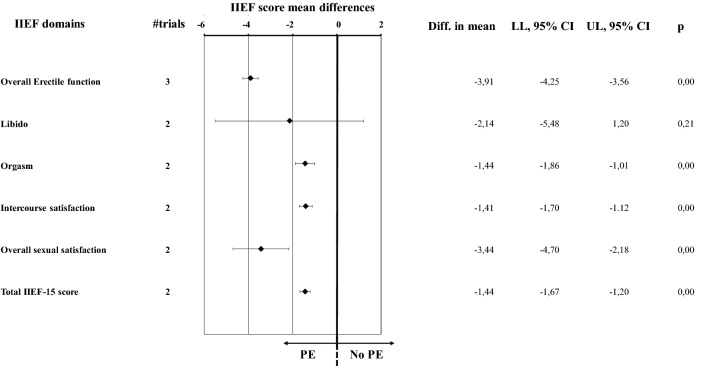

Among the available studies, 22 reported data on IIEF parameters (Table 2). Among them, three used IIEF-EFD score to evaluated ED whereas IIEF-5 was applied by all the others (Table 2). Overall I2 was 99.4; p < 0.0001. Funnel plot and Begg adjusted rank correlation test (Kendall’s τ: 0.72; p = 0.09) suggested no major publication bias. Overall, PE was associated with an impaired erectile function (Fig. 3). The data were confirmed even when only those studies considering IIEF-EFD score as outcome were analyzed (Fig. 4, and Supplementary Fig. 1, Panel A). Similarly, PE was associated with lower scores in orgasmic, intercourse and overall sexual satisfaction domains as well as in total IIEF-15 score (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 1, Panels C-F). Conversely, no differences in the libido domain between subjects with or without PE was observed (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 1, Panel B).

Fig. 3.

Effect size (with 95%CI) of erectile function component (including studies using International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF)-erectile function domain or IIEF-5 score as possible outcome) in subjects with or without premature ejaculation (PE)

Fig. 4.

Mean (with 95%CI) score on International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) domains in subjects with or without premature ejaculation (PE). Total IIEF-15 score has been reported as standardized mean (with 95%CI) for graphical purposes. Diff, differences; LL, lower limits; UP, upper limits

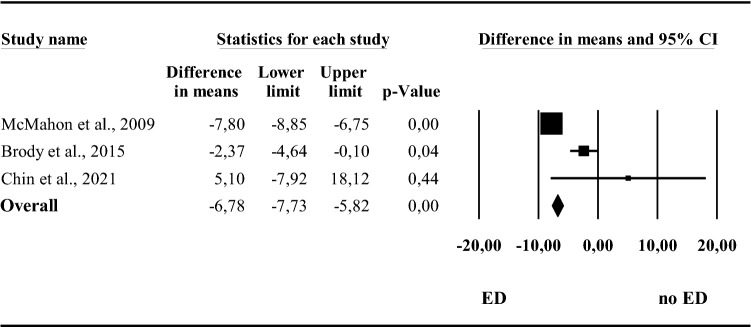

Intravaginal ejaculatory latency time

Three studies reported data on IELT according to the presence or absence of ED. By meta-analyzing available data, ED was associated with a significantly lower IELT when compared to controls (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Mean (with 95%CI) Intravaginal ejaculatory latency time (seconds) in men with or without erectile dysfunction (ED)

Available evidence analysis

The available evidence, here analyzed using an analytic approach, confirms the close association between ED and PE and the bidirectional nature of their relationship. In line with what was reported in our previous analysis of the data [2], PE was associated with a four-fold increased risk of ED independently of the definition used. In addition, the risk increased in older patients and in those with lower education, and it was associated with higher anxiety and depressive symptoms. Conversely, ED-related PE was characterized by lower associations with organic parameters such as diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia and with smoking habit. Finally, when ED was defined according to the IIEF questionnaire, the presence of a stable relationship increased the risk.

Available data cannot clarify the pattern of the temporal relationship between comorbid ED and PE. In a previous cross-sectional observational study, Chin et al., [40] showed that ED occurred after PE in 77.8% of patients with life-long PE and in 34.2% of those with acquired PE. However, the same authors found that PE and ED were comorbid at the same time in 22.2% of patients with life-long PE and 52% of those with acquired PE. Conversely, only 13.5% of patients with acquired PE reported that ED appeared earlier than PE [40]. Similar data were previously reported [42]. These indistinguishable onset times further support Jannini’s theory [42], which assumes that subjects with PE might develop ED to reduce their sexual excitement whereas those with ED can experience PE when training to increase their excitation. Accordingly, although the present data, in line with what has been previously reported by other authors [11, 31], showed that the risk of ED increased in patients with acquired PE, the possibility that ED can further complicate life-long PE due to the efforts of these subjects to reduce sexual excitement cannot be excluded [43]. On the other hand, the link between PE-related risk of ED and anxiety as well as depressive symptoms, here reported, confirms that ED subjects can secondarily experience PE as a consequence of the need for a more intense stimulation to attain and maintain an erection [42, 44]. In line with the latter hypothesis, the increased male genitalia tract smooth muscle tone, a consequence of the increased sympathetic tone, which characterizes performance anxiety, can eventually result in penile detumescence and PE [34, 45, 46]. However, it should be recognized that PE is often associated with a reduced quality of life (QoL), feelings of shame and inferiority as well as with low self esteem frequently related to depression and anxiety. Accordingly, EMAS [5] as well as the Premature Ejaculation Prevalence and Attitudes (PEPA [18]) studies documented higher depressive symptoms in patients with PE when compared to controls. In particular, the EMAS study clearly showed that depressive symptoms related to PE progressively increased as a function of PE-related distress [5].

As reported above, personal distress represents one of the crucial points, along with LT and inability to control, in correctly defining PE [1, 4, 7]. Data derived from the EMAS study have clarified that only a minority (7.3%) of subjects self-reporting PE declared being bothered about the problem [5]. The latter finding can better explain why only a limited number of subjects with PE request a medical consultation. Accordingly, we recently reported that among more than 4000 subjects seeking medical care for sexual dysfunction only 1.8% of them consulted only for PE, whereas the majority were for ED only (68.8%) and 19.4% for a combined problem of PE and ED [13]. The latter results confirm that PE can be considered a normal variant of sexual functioning in the vast majority of couples and, only when it determines distress or concomitant ED does it lead to the request for a medical consultation.

In line with what was previously reported [2], associated morbidities including diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia or traditional cardiovascular (CV) risk factors such as smoking habit were inversely related to PE-related risk of ED. Taken together these data seem to suggest that intrapsychic rather that organic factors contribute more to the development of PE-related risk of ED. However, the latter data should be interpreted with caution. We recently documented that among subjects seeking medical care for sexual dysfunction, those with comorbid ED and PE showed similar clinical and instrumental characteristics including high CV risk profile, impaired penile vascular flow at Doppler ultrasound and severe sexual complaints. Conversely, those who consulted for PE only were younger, healthier and with a more severe PE problem when compared to the other groups [13]. Hence, the concomitant presence of ED and PE seems to point to an ED problem rather than a separate sexual dysfunction, at least when clinical setting is considered. Accordingly, the present data show that the inverse association between organic comorbidities and the risk of ED disappeared when only those studies including patients evaluated in clinical settings were analyzed or when only those studies using IIEF-defined ED were considered. The latter condition represents a crucial point since it has been previously reported that up to 30% of subjects with PE who do not complain of ED have a pathological IIEF score [21]. Interestingly, when the same scenario is analyzed, a direct association between stable relationship and risk of ED was observed. It can be speculated that the reduced QoL and distress so closely associated with PE can impair couple fitness leading to a medical consultation [13, 47]. On the other hand, the possibility that a primary female sexual problem can secondarily induce the development of PE requiring medical support cannot be excluded. Accordingly, a recent meta-analysis including 26 studies and more than 15,000 subjects and 2,810 males documented that female sexual problems doubled the risk of PE [48].

Regardless of the temporal order, the presence of PE has a deleterious effect on male sexual functioning. Present data show that almost all domains of IIEF are significantly lower in patients reporting PE when compared to controls. Interestingly, however, no difference in the libido domain was observed. The latter observation seems to further support Jannini’s hypothesis suggesting that when a man tries to achieve an erection, he basically attempts to increase his excitation, possibly resulting in PE [43].

Several limitations should be recognized. First of all the use of different ED and PE definitions can represent an important source of bias. The cross-sectional nature of all the included studies must be considered as a further limitation. Similarly, data derived by combining different settings should be interpreted with caution due to high heterogeneity among the populations studied and documented by elevated I2. It must be recognized that natural history of PE-ED-related complaints is still unknown due to limited prospective and interventional studies. Finally, emerging evidence support a deterioration of erectile function and/or ejaculatory control after severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV2) infection [49–53]. No sufficient information on the relationship between ED and PE in patients recovered from coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) is available.

In conclusion, despite the aforementioned recognized weaknesses, the present data further support the view that ED and PE should be considered in a dimensional prospective way considering the possibility that both clinical entities can overlap and influence each other. In clinical settings, organic and CV risk factors seem to better support the link between ED and PE. Hence, in line with what has been suggested by all available current guidelines, concomitant ED should be ruled out in all men seeking medical care for PE [1, 7, 10, 14]. Accordingly, the use of oral PDE5i is less effective in improving ejaculatory timing when ED is not comorbid [1, 7, 10, 14]. In addition, the concomitant presence of ED should alert the clinician to screen for possible CV and metabolic morbidities to overcome ED-related risk for forthcoming CV mortality and morbidity [54–58]. On the other hand, a large body of evidence has shown that PE can negatively influence subjects self-esteem and QoL often resulting in couple fitness impairment [59, 60]. Correctly recognizing the underlying factors and sexual complaint can help the clinician in deciding the more appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic work-up.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

This article does not contain any study with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Footnotes

The paper is related to the Italian Society of Endocrinology Career Award 2021.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sansone A, Aversa A, Corona G, Fisher AD, Isidori AM, La Vignera S, et al. Management of premature ejaculation: a clinical guideline from the Italian Society of Andrology and Sexual Medicine (SIAMS) J Endocrinol Invest. 2021;44(5):1103–1118. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corona G, Rastrelli G, Limoncin E, Sforza A, Jannini EA, Maggi M. Interplay between premature ejaculation and erectile dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2015;12(12):2291–2300. doi: 10.1111/jsm.13041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCabe MP, Sharlip ID, Lewis R, Atalla E, Balon R, Fisher AD, et al. Incidence and prevalence of sexual dysfunction in women and men: a consensus statement from the fourth international consultation on sexual medicine 2015. J Sex Med. 2016;13(2):144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2015.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salonia A, Bettocchi C, Boeri L, Capogrosso P, Carvalho J, Cilesiz NC, et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Sexual and Reproductive Health-2021 Update: Male Sexual Dysfunction. Eur Urol. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Corona G, Rastrelli G, Bartfai G, Casanueva FF, Giwercman A, Antonio L, et al. Self-reported shorter than desired ejaculation latency and related distress-prevalence and clinical correlates: results from the European Male Ageing Study. J Sex Med. 2021;18(5):908–919. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.01.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowland DL, Althof SE, McMahon CG. The Unfinished Business of Defining Premature Ejaculation: The Need for Targeted Research. Sex Med Rev. 2022;9:78. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2021.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serefoglu EC, McMahon CG, Waldinger MD, Althof SE, Shindel A, Adaikan G, et al. An evidence-based unified definition of lifelong and acquired premature ejaculation: report of the second International Society for Sexual Medicine Ad Hoc Committee for the Definition of Premature Ejaculation. J Sex Med. 2014;11(6):1423–1441. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salonia A, Bettocchi C, Boeri L, Capogrosso P, Carvalho J, Cilesiz NC, et al. European association of urology guidelines on sexual and reproductive health-2021 update: male sexual dysfunction. Eur Urol. 2021;80(3):333–357. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2021.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shindel AW, Althof SE, Carrier S, Chou R, McMahon CG, Mulhall JP, et al. Disorders of Ejaculation: An AUA/SMSNA Guideline. J Urol. 2021 doi: 10.1097/ju0000000000002392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serefoglu EC, Yaman O, Cayan S, Asci R, Orhan I, Usta MF, et al. Prevalence of the complaint of ejaculating prematurely and the four premature ejaculation syndromes: results from the Turkish Society of Andrology Sexual Health Survey. J Sex Med. 2011;8(2):540–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waldinger MD, Schweitzer DH. Method and design of drug treatment research of subjective premature ejaculation in men differs from that of lifelong premature ejaculation in males: proposal for a new objective measure (part 1) Int J Impot Res. 2019;31(5):328–333. doi: 10.1038/s41443-018-0107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rastrelli G, Cipriani S, Corona G, Vignozzi L, Maggi M. Clinical characteristics of men complaining of premature ejaculation together with erectile dysfunction: a cross-sectional study. Andrology. 2019;7(2):163–171. doi: 10.1111/andr.12579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Althof SE, McMahon CG, Waldinger MD, Serefoglu EC, Shindel AW, Adaikan PG, et al. An update of the International Society of Sexual Medicine's guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of premature ejaculation (PE) J Sex Med. 2014;11(6):1392–1422. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Sakka AI. Premature ejaculation in non-insulin-dependent diabetic patients. Int J Androl. 2003;26(6):329–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2003.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basile Fasolo C, Mirone V, Gentile V, Parazzini F, Ricci E. Premature ejaculation: prevalence and associated conditions in a sample of 12,558 men attending the andrology prevention week 2001–a study of the Italian Society of Andrology (SIA) J Sex Med. 2005;2(3):376–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.20350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laumann EO, Nicolosi A, Glasser DB, Paik A, Gingell C, Moreira E, et al. Sexual problems among women and men aged 40–80 y: prevalence and correlates identified in the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17(1):39–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porst H, Montorsi F, Rosen RC, Gaynor L, Grupe S, Alexander J. The Premature Ejaculation Prevalence and Attitudes (PEPA) survey: prevalence, comorbidities, and professional help-seeking. Eur Urol. 2007;51(3):816–823. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Sakka AI. Severity of erectile dysfunction at presentation: effect of premature ejaculation and low desire. Urology. 2008;71(1):94–98. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malavige LS, Jayaratne SD, Kathriarachchi ST, Sivayogan S, Fernando DJ, Levy JC. Erectile dysfunction among men with diabetes is strongly associated with premature ejaculation and reduced libido. J Sex Med. 2008;5(9):2125–2134. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McMahon CG. Screening for erectile dysfunction in men with lifelong premature ejaculation–Is the Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM) reliable? J Sex Med. 2009;6(2):567–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang CZ, Hao ZY, Li HJ, Wang ZP, Xing JP, Hu WL, et al. Prevalence of premature ejaculation and its correlation with chronic prostatitis in Chinese men. Urology. 2010;76(4):962–966. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Son H, Song SH, Kim SW, Paick JS. Self-reported premature ejaculation prevalence and characteristics in Korean young males: community-based data from an internet survey. J Androl. 2010;31(6):540–546. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.110.010355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vakalopoulos I, Dimitriadis G, Varnava C, Herodotou Y, Gkotsos G, Radopoulos D. Prevalence of ejaculatory disorders in urban men: results of a random-sample survey. Andrologia. 2011;43(5):327–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2010.01079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang WS, Khoo EM. Prevalence and correlates of premature ejaculation in a primary care setting: a preliminary cross-sectional study. J Sex Med. 2011;8(7):2071–2078. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMahon CG, Lee G, Park JK, Adaikan PG. Premature ejaculation and erectile dysfunction prevalence and attitudes in the Asia-Pacific region. J Sex Med. 2012;9(2):454–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaeer O, Shaeer K, Shaeer E. The Global Online Sexuality Survey (GOSS): female sexual dysfunction among Internet users in the reproductive age group in the Middle East. J Sex Med. 2012;9(2):411–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaeer O. The global online sexuality survey (GOSS): The United States of America in 2011 Chapter III–Premature ejaculation among English-speaking male Internet users. J Sex Med. 2013;10(7):1882–1888. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee SW, Lee JH, Sung HH, Park HJ, Park JK, Choi SK, et al. The prevalence of premature ejaculation and its clinical characteristics in Korean men according to different definitions. Int J Impot Res. 2013;25(1):12–17. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2012.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao J, Zhang X, Su P, Liu J, Xia L, Yang J, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with the complaint of premature ejaculation and the four premature ejaculation syndromes: a large observational study in China. J Sex Med. 2013;10(7):1874–1881. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao J, Xu C, Liang C, Su P, Peng Z, Shi K, et al. Relationships between intravaginal ejaculatory latency time and national institutes of health-chronic prostatitis symptom index in the four types of premature ejaculation syndromes: a large observational study in China. J Sex Med. 2014;11(12):3093–3101. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maseroli E, Corona G, Rastrelli G, Lotti F, Cipriani S, Forti G, et al. Prevalence of endocrine and metabolic disorders in subjects with erectile dysfunction: a comparative study. J Sex Med. 2015;12(4):956–965. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brody S, Weiss P. Erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation: interrelationships and psychosexual factors. J Sex Med. 2015;12(2):398–404. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mourikis I, Antoniou M, Matsouka E, Vousoura E, Tzavara C, Ekizoglou C, et al. Anxiety and depression among Greek men with primary erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2015;14:34. doi: 10.1186/s12991-015-0074-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salama N, Eid A, Swedan A, Hatem A. Increased prevalence of premature ejaculation in men with metabolic syndrome. Aging Male. 2017;20(2):89–95. doi: 10.1080/13685538.2016.1277515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmad Zamree MR, Shaiful Bahari I, Faridah MZ, Norhayati MN. Premature ejaculation and its associated factors among men attending a primary healthcare clinic in Kelantan. Malaysia J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2018;13(2):173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song WH, Park J, Yoo S, Oh S, Cho SY, Cho MC, et al. Changes in the Prevalence and Risk Factors of Erectile Dysfunction during a Decade: The Korean Internet Sexuality Survey (KISS), a 10-Year-Interval Web-Based Survey. World J Mens Health. 2019;37(2):199–209. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.180054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsai WK, Chiang PK, Lu CC, Jiann BP. The Comorbidity Between Premature Ejaculation and Erectile Dysfunction-A Cross-Sectional Internet Survey. Sex Med. 2019;7(4):451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2019.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J, Li F, Li H, Zhang Z, Yang B, Li H. Clinical features of and couple's attitudes towards premature ejaculation: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Aging Male. 2020;23(5):946–952. doi: 10.1080/13685538.2019.1640194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chin CW, Tsai CM, Lin JT, Chen YS, Chen IH, Jiann BP. A Cross-Sectional Observational Study on the Coexistence of Erectile Dysfunction and Premature Ejaculation. Sex Med. 2021;9(6):100438. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2021.100438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohamed AH, Mohamud HA, Yasar A. The prevalence of premature ejaculation and its relationship with polygamous men: a cross-sectional observational study at a tertiary hospital in Somalia. BMC Urol. 2021;21(1):175. doi: 10.1186/s12894-021-00942-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jannini EA, Lombardo F, Lenzi A. Correlation between ejaculatory and erectile dysfunction. Int J Androl. 2005;28(Suppl 2):40–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jannini EA, Isidori AM, Aversa A, Lenzi A, Althof SE. Which is first? The controversial issue of precedence in the treatment of male sexual dysfunctions. J Sex Med. 2013;10(10):2359–2369. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dewitte M, Bettocchi C, Carvalho J, Corona G, Flink I, Limoncin E, et al. A Psychosocial Approach to Erectile Dysfunction: Position Statements from the European Society of Sexual Medicine (ESSM) Sex Med. 2021;9(6):100434. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2021.100434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Corona G, Ricca V, Bandini E, Rastrelli G, Casale H, Jannini EA, et al. SIEDY scale 3, a new instrument to detect psychological component in subjects with erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2012;9(8):2017–2026. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corona G, Ricca V, Bandini E, Mannucci E, Petrone L, Fisher AD, et al. Association between psychiatric symptoms and erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2008;5(2):458–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boddi V, Corona G, Fisher AD, Mannucci E, Ricca V, Sforza A, et al. "It takes two to tango": the relational domain in a cohort of subjects with erectile dysfunction (ED) J Sex Med. 2012;9(12):3126–3136. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chew PY, Choy CL, Sidi HB, Abdullah N, Che Roos NA, Salleh Sahimi HM, et al. The Association Between Female Sexual Dysfunction and Sexual Dysfunction in the Male Partner: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Sex Med. 2021;18(1):99–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pizzol D, Shin JI, Trott M, Ilie PC, Ippoliti S, Carrie AM, et al. Social environmental impact of COVID-19 and erectile dysfunction: an explorative review. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45(3):483–487. doi: 10.1007/s40618-021-01679-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sansone A, Mollaioli D, Ciocca G, Limoncin E, Colonnello E, Vena W, et al. Addressing male sexual and reproductive health in the wake of COVID-19 outbreak. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021;44(2):223–231. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01350-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mazzilli R, Zamponi V, Faggiano A. Letter to the editor: how the COVID-19 pandemic has changed outpatient diagnosis in the andrological setting. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45(2):463–464. doi: 10.1007/s40618-021-01673-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katz J, Yue S, Xue W, Gao H. Increased odds ratio for erectile dysfunction in COVID-19 patients. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45(4):859–864. doi: 10.1007/s40618-021-01717-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bertolo R, Cipriani C, Bove P. Anosmia and ageusia: a piece of the puzzle in the etiology of COVID-19-related transitory erectile dysfunction. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021;44(5):1123–1124. doi: 10.1007/s40618-021-01516-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Corona G, Rastrelli G, Isidori AM, Pivonello R, Bettocchi C, Reisman Y, et al. Erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular risk: a review of current findings. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2020;18(3):155–164. doi: 10.1080/14779072.2020.1745632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rastrelli G, Corona G, Fisher AD, Silverii A, Mannucci E, Maggi M. Two unconventional risk factors for major adverse cardiovascular events in subjects with sexual dysfunction: low education and reported partner's hypoactive sexual desire in comparison with conventional risk factors. J Sex Med. 2012;9(12):3227–3238. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rastrelli G, Corona G, Lotti F, Aversa A, Bartolini M, Mancini M, et al. Flaccid penile acceleration as a marker of cardiovascular risk in men without classical risk factors. J Sex Med. 2014;11(1):173–186. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sansone A, Reisman Y, Jannini EA. Relationship between hyperuricemia with deposition and sexual dysfunction in males and females. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;99:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s40618-021-01719-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Corona G, Sansone A, Pallotti F, Ferlin A, Pivonello R, Isidori AM, et al. People smoke for nicotine, but lose sexual and reproductive health for tar: a narrative review on the effect of cigarette smoking on male sexuality and reproduction. J Endocrinol Invest. 2020;43(10):1391–1408. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01257-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosen RC, Althof S. Impact of premature ejaculation: the psychological, quality of life, and sexual relationship consequences. J Sex Med. 2008;5(6):1296–1307. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rowland DL. A Conceptual Approach to Understanding and Managing Men's Orgasmic Difficulties. Urol Clin North Am. 2021;48(4):577–590. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2021.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.