Significance Statement

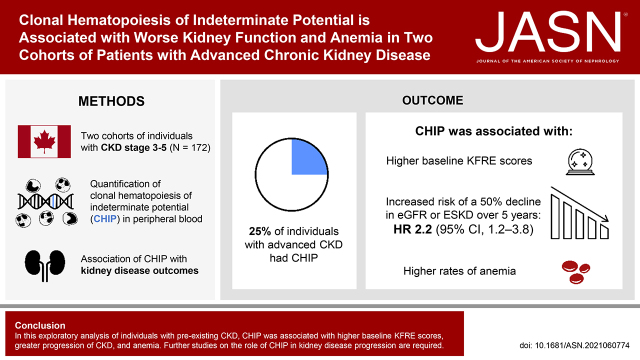

Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), a premalignant expansion of clonal leukocytes caused by acquired somatic mutations in myeloid stem/progenitor cells, occurs in 10%–15% of the general population aged 65 years or older. This proinflammatory condition appears causally associated with cardiovascular disease and death. The authors found that 43 of 172 (25%) individuals with advanced CKD had CHIP. Those with CHIP had a 2.2-fold greater risk of kidney failure over 5 years of follow-up and were more likely to have complications of CKD (including anemia) compared with those without CHIP. More research, including studies in animal models, is needed to understand the relationship between CHIP and CKD. CHIP-related inflammation might offer a novel therapeutic target for those with CHIP and CKD.

Keywords: chronic inflammation, anemia, macrophages, clonal hematopoiesis, clone cells, hematopoiesis, cohort studies, chronic renal insufficiency

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) is an inflammatory premalignant disorder resulting from acquired genetic mutations in hematopoietic stem cells. This condition is common in aging populations and associated with cardiovascular morbidity and overall mortality, but its role in CKD is unknown.

Methods

We performed targeted sequencing to detect CHIP mutations in two independent cohorts of 87 and 85 adults with an eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73m2. We also assessed kidney function, hematologic, and mineral bone disease parameters cross-sectionally at baseline, and collected creatinine measurements over the following 5-year period.

Results

At baseline, CHIP was detected in 18 of 87 (21%) and 25 of 85 (29%) cohort participants. Participants with CHIP were at higher risk of kidney failure, as predicted by the Kidney Failure Risk Equation (KFRE), compared with those without CHIP. Individuals with CHIP manifested a 2.2-fold increased risk of a 50% decline in eGFR or ESKD over 5 years of follow-up (hazard ratio 2.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.2 to 3.8) in a Cox proportional hazard model adjusted for age, sex, and baseline eGFR. The addition of CHIP to 2-year and 5-year calibrated KFRE risk models improved ESKD predictions. Those with CHIP also had lower hemoglobin, higher ferritin, and higher red blood cell mean corpuscular volume versus those without CHIP.

Conclusions

In this exploratory analysis of individuals with preexisting CKD, CHIP was associated with higher baseline KFRE scores, greater progression of CKD, and anemia. Further research is needed to define the nature of the relationship between CHIP and kidney disease progression.

Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) is a newly recognized, age-associated hematologic disorder that confers risk of multisystem morbidity and mortality.1 When hematopoietic stem cells acquire mutations in key cell regulatory genes, biased production of a clonal myeloid cell population can result in altered immune function.2–5 The three most mutated genes driving CHIP—TET2, DNMT3A, and ASXL1—are epigenetic regulators. CHIP is defined when the fraction of mutant alleles reaches at least 2% in blood. Because CHIP mutations are most often heterozygous, the clonal expansion of mutant progeny cells accounts for at least 4% of nucleated cells in the blood compartment. On the basis of this definition, the prevalence of CHIP is at least 10%–20% in persons aged 65 and older6,7 and subthreshold clones are nearly ubiquitous in people over the age of 40.8 Akin to other premalignant states, CHIP is associated with risk of transformation to hematologic cancers; however, such transformation is uncommon in people with CHIP, with an estimated annual incidence of 0.5%–1%.9,10 CHIP also predicts risk of developing cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality, including in people with CKD.11–13 The cardiovascular risk associated with CHIP is greater than that observed for some traditional cardiovascular risk factors including smoking, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.14

Myeloid cells carrying CHIP mutations produce high levels of inflammatory cytokines,6 and both dysregulated IL-6 and inflammasome signaling have been causally implicated in CHIP pathogenesis.2–5,15 Moreover, experimental recapitulation of CHIP by transplanting even a small fraction of affected hematopoietic stem cells leads to kidney tubulointerstitial fibrosis and replacement of resident macrophages with clonal progeny.4,16 Because macrophages and neutrophils play pivotal roles in innate immunity, response to injury, management of the kidney interstitial environment, and inflammatory signaling,17 we hypothesized that people with CHIP would have more rapid progression of CKD. A recent study of UK Biobank participants reported an association between CHIP and lower cystatin-based eGFR.13 In this report, we analyzed the association of CHIP with kidney function decline and its complications in two independent cohorts of individuals with baseline advanced CKD.

Methods

Study Population

Two independent Canadian CKD cohorts were studied. The first was a longitudinal cohort of individuals followed in CKD clinics at Kingston Health Sciences Centre in Kingston, Ontario, Canada (Kingston cohort). In 2009, 87 individuals were enrolled in this longitudinal cohort study.18–23 Inclusion criteria were CKD category G3–5, age 18 years or older, and with no prior history of hematologic malignancy. Participants had a median follow-up of 10.8 years (interquartile range, 5.3, 11.4). The study was approved by Queen’s University Health Sciences and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board (file no. 6023740).

The second cohort consisted of individuals enrolled in the Canadian study of Prediction of Death, Dialysis, and Interim Cardiovascular evenTs (CanPREDDICT). CanPREDDICT is a 25-site observational cohort that recruited 2546 adults with CKD from outpatient nephrology clinics across Canada in 2008–2009.24 Inclusion criteria included eGFR of 15–45 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Exclusion criteria included active vasculitis, previous organ transplantation, or a life expectancy of <1 year. Participants were followed at protocolized visits for up to 5 years; every 6 months for years 1–3 then annually for years 4–5. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the 25 participating centers. The study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (no. NCT00826319). For this study, we selected a random sample of 94 individuals for CHIP genotyping who additionally met the following criteria: aged 65–85 years and CKD attributed to any cause except GN or polycystic kidney disease (see Supplemental Figure 1).

CHIP Genotyping

For the Kingston cohort, peripheral venous blood was collected in PAXgene tubes at enrollment. DNA was extracted and stored at −80°C. Genomic DNA was further purified using Axygen AxyPrep FragmentSelect-I kit, then quantified using TaqMan RNaseP qPCR assay. DNA libraries were constructed using Ion AmpliSeq Kit for Chef DL8 with a validated custom AmpliSeq targeted CHIP 48-gene panel (genomic coverage as previously described7) on the Ion Chef instrument, followed by sequencing using an Ion 540 chip on the Ion S5XL sequencer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The mean depth of coverage was >1500× for all four sequencing runs, and the sample with the lowest coverage had 1409× coverage. Sequences were aligned to hg19 and variants were called using Ion Torrent Suite software. Putative somatic mutations were identified using Ion Reporter software, excluding common genetic variants in the University of California Santa Cruz database, and rare variants in the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD); filtering for exonic location, nonsynonymous substitution, Phred quality score >20, coverage>50, and variant allele fraction (VAF) between 0.02 and 0.44; and visualizing in the Integrated Genomics Viewer (IGV, https://software.broadinstitute.org/software/igv/). The corresponding VAF was recorded for each filtered variant. Participants were classified as having CHIP if they had at least one CHIP driver mutation at a VAF≥0.02, inferred to mean that the allele is present in a heterozygous state in ≥4% of diploid cells. Those who did not meet these criteria were classified as not having CHIP.

For CanPREDDICT, samples were extracted from peripheral venous blood collected in EDTA collection tubes, centrifuged to extract the buffy coat layer, and stored at −80°C, then thawed for DNA extraction and purification and quantified as described above. DNA libraries were constructed using the TWIST Library Preparation 2.0 protocol with Enzymatic Fragmentation and Universal Adapter TWIST System. A custom TWIST panel was designed to enrich for exonic sequences in 94 CHIP driver genes associated with CHIP and hematologic cancers. Paired-end read sequencing (2 × 100 bp) was performed on the Illumina Novaseq using an SP flow cell with standard loading. The DRAGEN Bio-IT platform (version 3.8) was used to process read sequence data following the “Somatic Mode” to perform alignment to the hg38 reference genome and somatic variant calling in “tumor-only” mode. Variant calling was confined to the targeted exonic regions spanning a total of 323 kb. Putative variant calls with both “PASS” and “SOMATIC” VCF annotations were then linked to database annotations (refGene, avsnp150, dbnsfp41a, clinvar, cosmic70, icgc28, gnomAD version 2.11) using Annovar (annovar.openbioinformatics.org). All putative somatic variants were then inspected in IGV. CHIP classification in CanPREDDICT followed similar criteria as in the Kingston cohort, namely that participants were classified as having CHIP if they had at least one CHIP driver mutation at a VAF≥0.02. Nine samples with >50 putative somatic mutation calls across the 94 genes were omitted because further review suggested issues with library quality, thus leading to 85 samples for evaluation in downstream analyses.

Measurement of Outcomes

The primary outcome was a sustained 50% decline in eGFR from the baseline value or ESKD. ESKD was defined by an eGFR<15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (or the initiation of maintenance dialysis or kidney transplantation if this occurred before an eGFR<15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was recorded). A sustained 50% decline in eGFR and a sustained eGFR<15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 required two consecutive qualifying measurements 28 or more days apart in the Kingston cohort or at two consecutive study visits (≥6 months apart) for the CanPREDDICT cohort. The longitudinal slope of decline in eGFR was also assessed using a linear mixed model.

For the Kingston cohort, all serum creatinine measurements were abstracted from routine scheduled outpatient bloodwork from 2009 until December 31, 2020, excluding data from hospitalizations and “for cause” assessments. A total of 2091 creatinine measurements were collected over 527 years of follow-up for an average of four measurements per year per participant. Creatinine concentrations were measured using an isotope dilution mass-spectrometry traceable assay (Roche Creatinine Plus Modular assay). We calculated the eGFR from creatinine using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) 2021 equation which does not include race adjustment.25 We ascertained dialysis, transplantation, and mortality status by electronic chart review at the study end by a single reviewer. For the CanPREDDICT cohort, serum creatinine and outcome data were collected prospectively by chart review at established time intervals over 5 years (i.e., at baseline, then at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, and 5 years). Source documentation for possible events was reviewed by an independent adjudication committee. For eGFR-related outcome analyses, the Kingston cohort data were censored at 5 years to match the CanPREDDICT follow-up period.

Measurement of Other Study Data

For the Kingston cohort, we obtained clinical data, including medical histories and social habits, by participant self-report. We determined medication histories by electronic chart review, including prescriptions of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs). Synchronous with the time of DNA collection, cross-sectional serum urea, bicarbonate, phosphate, calcium corrected for albumin, intact parathyroid hormone (PTH), complete blood count, and C-reactive protein (CRP), as well as urine albumin-creatinine ratio (UACR), were collected at baseline for both cohorts. For the CanPREDDICT cohort, hsCRP was measured using Siemens BNII Nephelometric Immunoassay. LIAISON N-TACT PTH assay was conducted on the DiaSorin Liaison analyzer. FGF-23 measurements were obtained through plasma samples analyzed using second-generation C-terminal assay (Immutopics, San Clemente, CA).

Baseline eGFR, UACR, age, and sex were used to calculate the 2- and 5-year Kidney Failure Risk Equation (KFRE) scores using the four-variable equations.26,27 Additionally, serum ferritin, transferrin saturation, and red blood cell mean corpuscular volume (MCV) were collected for participants in the Kingston cohort. Longitudinal hemoglobin data were available for 3 years of follow-up in CanPREDDICT and up to 12 years in the Kingston cohort. We retrieved these values and averaged for every year of follow-up on a per-participant basis, with censoring upon receipt of a kidney transplant when applicable. The proportions of participants with anemia, defined as hemoglobin<12 g/dl for women and hemoglobin<13 g/dl for men,28 were also compared between those with and without CHIP.

Statistical Analyses

We tabulated baseline characteristics according to the presence versus absence of CHIP. The VAF was tabulated for each CHIP variant. Baseline laboratory data (kidney function, hematologic parameters, bone mineral markers, and inflammatory markers) were tested for association with CHIP status and quantitative VAF using linear regression in univariable and multivariable analyses adjusted for age, sex, and baseline eGFR. Baseline predicted risk of kidney failure, as quantified by the four-variable 2-year and 5-year KFRE equations, was also assessed in adjusted linear regression analyses.

For analyses of kidney disease progression, all participants were followed from the ascertainment of CHIP status until the primary outcome occurred, or they were censored due to death, loss to follow-up, or the end of the study period, whichever came first. We constructed Cox proportional-hazards regression models to estimate the association of CHIP status at baseline with the time to kidney disease outcome with adjustment for baseline age, sex, and baseline eGFR.

To assess whether CHIP improved upon 2- and 5-year KFRE predictions of ESKD, we assessed nested Cox proportional-hazards models for improvement in fit. Examination for reductions in Akaike information criterion (AIC) and ANOVA-based likelihood testing were used to assess whether the addition of variables improved the model.29

To quantify the association of CHIP status with the slope of eGFR decline, we used linear mixed model regression, allowing for random slopes and intercepts of eGFR decline in each participant while testing for a fixed effect of baseline age, sex, and CHIP on eGFR across participants. Only participants with baseline eGFR>15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 were included in this analysis, and to reduce survival bias, we limited the observation period to the first 3 years after CHIP genotyping, where 119 (85%) participants remained uncensored to minimize nonrandom censoring due to death or initiation of dialysis.

All analyses were performed using R statistical software version 4.0.5, with the significance level (α) set to 0.05.

Results

Prevalence of CHIP in the Advanced CKD Cohort at Baseline

Mean age was 64±14 years (mean±SD) for the Kingston cohort and 74±5.5 years for CanPREDDICT; 43% of the Kingston cohort and 32% of CanPREDDICT were women; the mean baseline eGFR was 27±11 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in the Kingston cohort and 28±9 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in CanPREDDICT. All participants in the Kingston cohort self-identified as European ancestry. In CanPREDDICT, seven people self-identified as of Arabic ancestry, one person of Black ancestry, and one person of Asian ancestry.

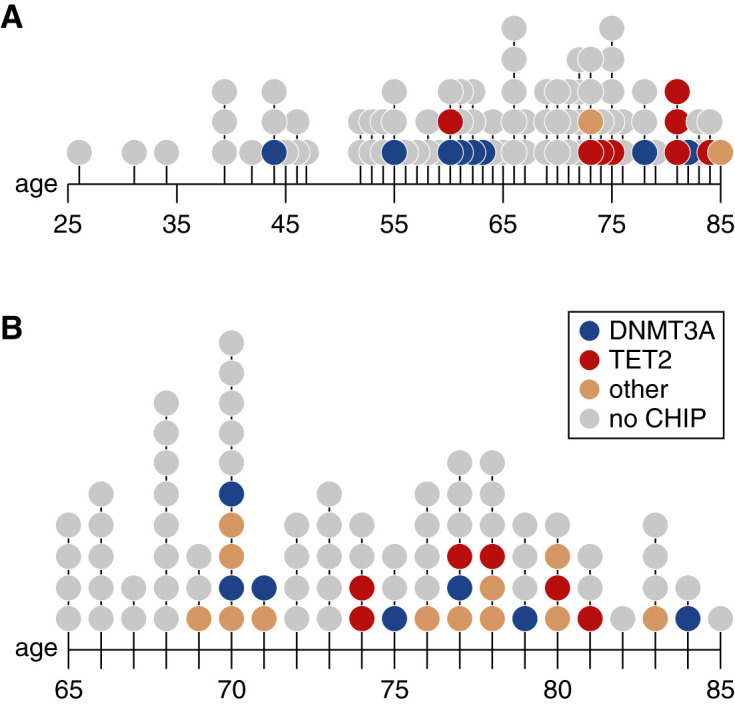

Of the 172 individuals in the cohorts combined, 43 (25%) were found to carry CHIP variants at a VAF≥2% (Figure 1). The specific variants are listed in Supplemental Table 1. The genes most commonly affected were DNMT3A (17 of 43) and TET2 (16 of 43). Twelve participants had multiple CHIP variants, and the average VAF for the largest detected clone per individual was 10% in the Kingston cohort and 15% in CanPREDDICT.

Figure 1.

The prevalence of CHIP increases with age. Age distribution of CHIP carriers in the (A) Kingston and (B) CanPREDDICT cohorts. Each point represents a person, color-coded by the gene including a CHIP driver variant.

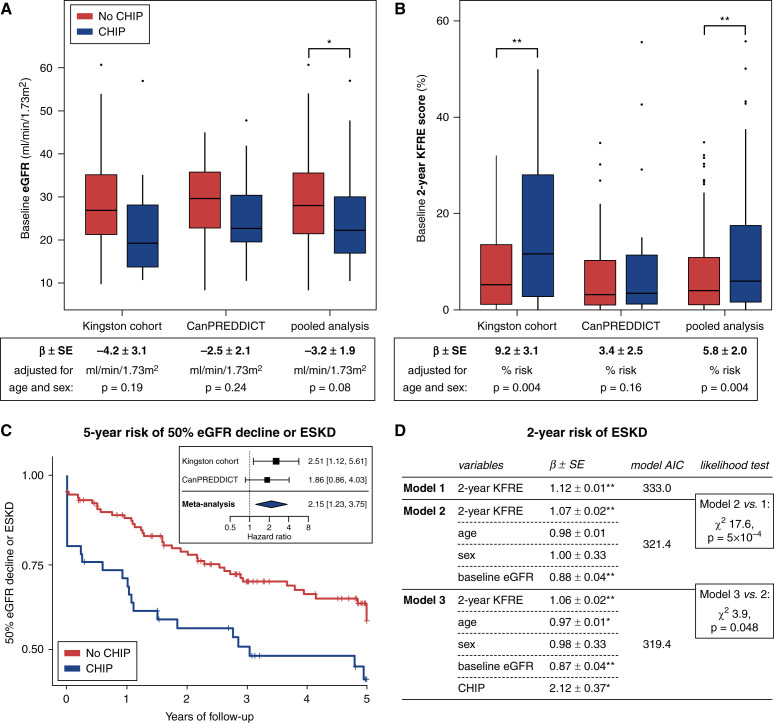

Participants with CHIP were older and had a lower eGFR at baseline (Table 1, Figure 2A). The lower baseline eGFR in those with CHIP did not remain significant after adjusting for age and sex (−3.2±1.9 ml/min per 1.73 m2, P=0.08).

Table 1.

Baseline cohort characteristics

| Characteristic | Kingston Cohort | CanPREDDICT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHIP (n=18) | No CHIP (n=69) | CHIP (n=25) | No CHIP (n=60) | |

| Age | 70.9±11.8 | 62.0±13.4 | 75.7±4.6 | 73.1±5.7 |

| Female | 9 (50) | 29 (42) | 9 (36) | 18 (30) |

| Baseline eGFR (CKD-EPI) | 23.4±11.6 | 28.4±11.3 | 26.1±9.3 | 28.9±8.7 |

| UACR (mg/g) | 248 [36, 1126] | 149 [30, 770] | 96 [24, 245] | 161 [26, 331] |

| Microalbuminuria (UACR≥30 mg/g) | 14 (78) | 48 (75) | 16 (64) | 42 (70) |

| Macroalbuminuria (UACR≥300 mg/g) | 8 (44) | 26 (41) | 6 (24) | 17 (28) |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 18 (100) | 63 (91) | 25 (100) | 60 (100) |

| Diabetes, N (%) | 6 (33) | 27 (39) | 15 (60) | 34 (57) |

| Smoking, N (%) | 8 (44) | 40 (58) | Unavailable | |

| Dyslipidemia, N (%) | 14 (78) | 61 (88) | 19 (76) | 52 (87) |

| Cause of CKD | 6 DKD 5 HTN 7 unknown/other | 24 DKD 20 HTN 25 unknown/other | 10 DKD 11 HTN 4 unknown/other | 28 DKD 24 HTN 8 unknown/other |

Data are presented as mean±SD, median [interquartile range], or count (percentage). CKD-EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration; DKD, diabetic kidney disease; HTN, hypertension.

Figure 2.

CHIP is associated with worse baseline kidney function and progression of CKD. (A) The average baseline eGFR is lower in those with CHIP compared with those without CHIP (n=172) but not after adjusting for age and sex. (B) The 2-year KFRE scores are higher in those with CHIP in both cohorts, including after adjusting for age and sex. The 5-year KFRE scores are similarly higher in CHIP (29.1±4.4 versus 19.9±1.8), including after adjusting for baseline age and sex (P=0.01). (C) Survival curves for the composite outcome of 50% eGFR decline or ESKD by CHIP status adjusted for age, sex, and baseline eGFR over 5 years of follow-up (pooled cohorts; n=172; log-rank test P=0.01). Inset is a forest plot of the Cox proportional hazard ratio in each cohort independently and after meta-analysis, adjusted for age, sex, and baseline eGFR (n=172 total). (D) Iterative improvement in time-to-ESKD risk prediction. The best-fit model includes 2-year KFRE score, age, sex, baseline eGFR, and CHIP. The results for 5-year KFRE are similar and presented in Supplemental Figure 2B. Significant results are highlighted as follows: **P<0.01, *P<0.05.

Individuals with CHIP had a greater predicted risk of kidney functional decline, as quantified by the 2- and 5-year KFRE scores (2-year KFRE: 12.9±2.3% versus 8.8±0.8%, P=0.007; 5-year KFRE: 29.1±4.4% versus 19.9±1.8%, P=0.02). The increased KFRE observed in people with CHIP persisted after adjusting for differences in age and sex (Figure 2A).

Association of CHIP with Kidney Disease Progression

To test if those with CHIP manifested the increased risk of kidney functional decline, we assessed the primary outcome of a sustained 50% drop in eGFR or ESKD over 5 years of follow-up. Of 172 participants with CHIP genotypes, the primary outcome was observed in 67 participants (ESKD in 63, 50% decline in eGFR in four). The primary outcome occurred in 22 persons with CHIP (incidence rate 19.6/100 person-years) and 45 persons without CHIP (incidence rate 11.3/100 person-years). In a meta-analysis of both cohorts adjusting for age, sex, and baseline eGFR, the presence of CHIP was associated with a 2.2-fold greater risk of 50% decline in eGFR or ESKD (hazard ratio 2.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.2 to 3.8, times greater risk; Figure 2C). In linear mixed model regression, the baseline eGFR (intercept) was lower for those with CHIP, but we observed no difference in the slope of eGFR decline in the first 3 years (Supplemental Figure 2A).

KFRE scores quantifying 2-year risk of ESKD were associated with time-to-ESKD events (Figure 2D). This base model was then adjusted by including age, sex, and baseline eGFR, which significantly improved the model fit over KFRE alone despite being part of KFRE (AIC reduction from 333.0 to 321.4, likelihood ratio test P=5 × 10−4). Further adding CHIP to the model resulted in additional improvement (AIC reduction from 321.4 to 319.4, likelihood ratio test P=0.048). Results were similar when examining the 5-year KFRE risk prediction model (Supplemental Figure 2B).

CHIP and Complications of CKD

We evaluated the association between CHIP and common complications of CKD including hyperparathyroidism, hyperphosphatemia, metabolic acidosis, and anemia. Compared with those without CHIP, baseline PTH was higher (21.9±3.6 versus 13.0±1.0 pg/ml), serum phosphate levels were higher (1.29±0.04 versus 1.19±0.02 mmol/L), and serum bicarbonate levels were lower (24.7±0.4 versus 26.2±0.3 mEq/L) than those in the group with CHIP (Table 2, all P<0.05). The association between CHIP and higher PTH remained after adjusting for age, sex, and baseline eGFR (Table 2), whereas phosphate and bicarbonate were not associated in adjusted models.

Table 2.

CHIP is associated with CKD complications

| Outcome | Cohort | CHIP (univariable) | CHIP (adjusted for age, sex, and baseline eGFR) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β±SEM | P | β±SEM | P | ||

| log(ACR [mg/g]) | Kingston | 0.12±0.51 | 0.82 | 0.59±0.50 | 0.24 |

| CanPREDDICT | −0.05±0.45 | 0.91 | 0.13±0.45 | 0.78 | |

| Pooled | −0.02±0.34 | 0.95 | 0.31±0.33 | 0.35 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | Kingston | −1.62±0.42a | <0.001 | −1.38±0.39a | <0.001 |

| CanPREDDICT | −0.67±0.39 | 0.09 | −0.64±0.40 | 0.113 | |

| Pooled | −1.12±0.29a | <0.001 | −0.95±0.28a | <0.001 | |

| Urea (mmol/L) | Kingston | 4.3±1.9a | 0.02 | 2.8±1.4 | 0.05 |

| CanPREDDICT | 0.7±1.7 | 0.70 | −0.7±1.3 | 0.61 | |

| Pooled | 2.5±1.2 | 0.05 | 0.8±1.0 | 0.40 | |

| Bicarbonate (mEq/L) | Kingston | −2.4±0.7a | 0.002 | −2.0±0.7a | 0.005 |

| CanPREDDICT | −0.3±0.9 | 0.74 | −0.1±1.0 | 0.93 | |

| Pooled | −1.4±0.6a | 0.02 | −1.0±0.57 | 0.10 | |

| PTHa (pg/ml) | Kingston | 8.6±2.9a | 0.004 | 7.2±2.6a | 0.007 |

| CanPREDDICT | 9.2±6.3 | 0.15 | 8.8±5.9 | 0.14 | |

| Pooled | 8.9±2.7a | 0.002 | 6.9±2.5a | 0.006 | |

| Phosphate (mmol/L) | Kingston | 0.16±0.07a | 0.02 | 0.13±0.06 | 0.05 |

| CanPREDDICT | 0.05±0.05 | 0.35 | 0.04±0.05 | 0.38 | |

| Pooled | 0.09±0.04a | 0.03 | 0.08±0.04 | 0.06 | |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | Kingston | −0.04±0.03 | 0.23 | −0.04±0.03 | 0.27 |

| CanPREDDICT | −0.01±0.03 | 0.73 | −0.01±0.03 | 0.69 | |

| Pooled | −0.03±0.02 | 0.25 | −0.02±0.02 | 0.29 | |

| MCV (fl) | Kingston | 2.6±1.2a | 0.03 | 1.8±1.2 | 0.14 |

| Ferritin (µg/L) | Kingston | 135.6±37.9a | <0.001 | 128.2±38.2a | 0.001 |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | Kingston | 1.9±2.8 | 0.50 | 2.9±2.9 | 0.32 |

| log(CRP) | Kingston | 0.1±0.33 | 0.77 | 0.05±0.34 | 0.89 |

| CanPREDDICT | 0.1±0.28 | 0.77 | −0.02±0.29 | 0.94 | |

| Pooled | 0.1±0.21 | 0.67 | −0.03±0.22 | 0.88 | |

| log(FGF23) | Kingston | 0.11±0.26 | 0.66 | −0.06±0.21 | 0.78 |

| CanPREDDICT | −0.09±0.16 | 0.57 | −0.17±0.12 | 0.16 | |

| Pooled | 0.05±0.15 | 0.73 | −0.15±0.13 | 0.26 | |

The results of univariable (CHIP) and multivariable (CHIP, age, sex, baseline eGFR) linear regressions are presented for each secondary outcome of interest. The β coefficient indicates the quantitative change in the outcome for those with CHIP compared with those without CHIP.

PTH values excluded two individuals who had primary hyperthyroidism (one individual with CHIP who was untreated at baseline and one without CHIP who had received parathyroidectomy before baseline assessment).

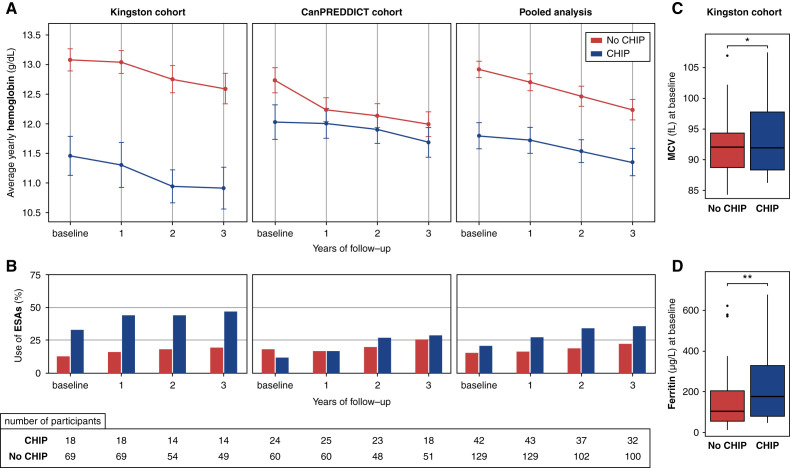

Participants with CHIP were more likely to be anemic at baseline compared with individuals without CHIP (72% versus 44%; chi square=10.1, P=0.002). Hemoglobin concentration was lower in those with CHIP at baseline (11.8±0.2 versus 12.9±0.1 g/dl, P<0.001), and the difference persisted over the 3-year observation period (Figure 3A). After adjusting for age, sex, and baseline eGFR, baseline hemoglobin was 0.9±0.3 g/dl lower in those with CHIP (P<0.001, Table 2). Further, the difference was not explained by differences in ESA use (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

CHIP is associated with lower hemoglobin, higher MCV, and higher ferritin. (A) Hemoglobin values—averaged per person over yearly periods and shown with SEM—are significantly lower in those with CHIP throughout the follow-up period in the Kingston cohort. Baseline hemoglobin is significantly different in CanPREDDICT. Hemoglobin values are censored upon receipt of a kidney transplant. (B) The proportion of individuals prescribed ESA use was not significantly different among those with CHIP. (C) MCV was higher among those with CHIP (t test P<0.05). (D) Ferritin was higher among those with CHIP (t test P<0.01), whereas transferrin saturation was not different (n=87 for both). MCV, ferritin, and transferrin saturation were only available in the Kingston cohort.

Ferritin and MCV were available for the Kingston cohort. MCV was higher in those with CHIP (Figure 3C, 94.3±1.4 versus 91.6±0.5 fl, P=0.03). Ferritin levels were also higher in those with CHIP (Figure 3D, 269±51 versus 133±14 µg/L), including after adjustment for age, sex, and baseline eGFR (Table 2, β=128.2±38.2 µg/L, P=0.004), whereas transferrin saturation was within the normal range and not different between groups (Table 2). Thus, iron deficiency was not a significant contributor to the observed anemia; instead, the higher ferritin in those with CHIP may reflect greater inflammation. Ferritin levels were negatively associated with hemoglobin levels (R=−0.405, P<0.0001), whereas log-transformed CRP (log-CRP) levels were not correlated with hemoglobin (R=−0.192, P=0.08). The association between CHIP and lower hemoglobin remained when ferritin and log-CRP were introduced as independent covariates in the model (β=−1.1±0.4 g/dl, P=0.008). Hemoglobin levels, MCV, and ferritin were also correlated with the CHIP VAF in the Kingston cohort (R=−0.29, P=0.010; R=0.34, P=0.001; R=0.33, P=0.002, respectively; Supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

In two longitudinal cohorts including 172 individuals with advanced CKD, the presence of CHIP was associated with worse baseline KFRE scores and a higher risk of developing the primary outcome of sustained 50% decline in eGFR from baseline or ESKD. Adding CHIP to a model including KFRE improved both 2- and 5-year predictions of ESKD, suggesting CHIP could help refine ESKD risk prediction.

In these participants with advanced CKD, CHIP was associated with higher rates of anemia despite no difference in iron saturation and significantly higher ferritin. Anemia in CKD is the result of a heterogeneous mix of causes including but not limited to erythropoietin deficiency; chronic inflammation (IL-6–mediated hepcidin elevation); and iron, B12, and folate deficiency.30 The inflammation observed in CHIP may contribute to anemia severity in CKD that could be treatable using new therapies for anemia of inflammation in those with kidney disease.27,31 Because CHIP mutations affect hematopoietic stem cells directly, erythrocyte development and function may also be negatively affected.32 It is conceivable that CHIP adds a layer of stress to erythropoiesis in CKD that manifests as a quantitative defect with lower hemoglobin and increased MCV, as observed in our study.33 Although CHIP is not associated with blood counts in surveys of healthy population cohorts,34 CHIP variants have been reported at a higher-than-expected prevalence in individuals with anemia.35

CHIP was common in these cohorts of advanced CKD: 25% of participants were found to have a CHIP variant at a VAF of 2% or greater. This CHIP prevalence falls within the range observed in other targeted CHIP sequencing studies (15%–30%).7,36,37 However, it is important to note that differences in participant age, comorbidities, and exposures, as well as the sequencing methodology employed and putative CHIP variant interpretation, can affect estimates of CHIP prevalence across studies. Age and cigarette smoking are common risk factors for CHIP, whereas exposure to chemotherapy has been associated with the development of CHIP with mutations in DNA damage response driver genes.38 Targeted sequencing approaches provide the greatest sequencing depth and therefore greater resolution to identify CHIP variants at a low VAF. In this study, the targeted panels had a sequencing depth of up to 2000 reads per site, allowing for detection of CHIP clones at a VAF as low as 2.2%. The largest CHIP studies have used whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing data which are less sensitive for detecting low-VAF clones; for example, in an analysis of 97,691 whole genomes the average read depth was 40×, allowing CHIP with VAF>10% to be reliably detected, but CHIP with VAF 5%–10% was only detected half of the time and CHIP with VAF<5% was not detectable.6 Differences in the interpretation of putative CHIP driver variants can also affect prevalence estimates. At present, criteria for the interpretation of putative CHIP driver variants have been proposed by Jaiswal et al.,12 Dawoud et al.,13 and Lindsley et al.39 Heterozygous germline variants with lower-than-expected VAF may also be incorrectly called somatic variants. We observed a TET2 A1505T variant with a VAF of 43%, but the variant was found to have a VAF of 51% after sequencing a colon biopsy sample from the same person, indicating it was a heterozygous germline rare variant, not a somatic CHIP mutation.

In this study, we are unable to determine if CHIP plays a causal role in CKD progression, or whether CKD itself increases the risk of CHIP. Increased proinflammatory cytokine activity appears to be a common mechanism of CHIP pathogenesis: studies using mouse models of Tet2-, Dnmt3a-, Jak2-, and Ppm1d-CHIP have implicated upregulated IL-6 and IL-1β signaling as mediators of the observed increased risk for cardiovascular disease4,5,12,40–43 as well as insulin resistance44 and osteoporosis.45 Because dysregulated inflammation is a key mediator of chronic kidney damage and fibrosis,17 CHIP may contribute to kidney disease progression. Experimental validation is required to test this hypothesis. Conversely, proinflammatory cytokines have been shown to promote clonal expansion.46–48 CHIP is more common in inflammatory autoimmune conditions,49 such as ANCA-associated vasculitis,50 rheumatoid arthritis,51 and possibly giant cell arteritis.52 Because advanced CKD is a hyperinflammatory state,17 CHIP may be more common in CKD. In studies of participants across a broader range of eGFR, the prevalence of CHIP increases as eGFR decreases, as shown in a survey of UK Biobank patients13 and in a secondary analysis of individuals in our community-based cohort7 presented in Supplemental Figure 3A. More definitive estimates of the epidemiology of CHIP in CKD are needed. Moreover, defining the causality and directionality of the relationship between CHIP and kidney health is important, because strategies aimed at the surveillance, prevention, and treatment of CHIP are in development.

A major limitation of our study is the sample size. Despite the small size of our two independent cohorts, we observed consistent significant signals between them. Studies of CHIP in other phenotypes have also yielded associations using similar sized cohorts, including studies in heart failure53,54 (n=62 and 200), valvular heart disease55 (n=279), and ANCA-associated vasculitis50 (n=117), and in patients undergoing hip arthroplasty49 (n=200). Moreover, the 2.2-fold increased risk of 50% decline in eGFR or ESKD with the presence of CHIP is in keeping with the 1.9-times greater risk for coronary heart disease observed with CHIP.12 Although this study suggests CHIP may be an inflammatory consideration in CKD progression, larger studies are needed before a definitive link between CHIP and kidney disease can be drawn.

In conclusion, in two small cohorts of patients with advanced CKD we observed an association between CHIP and worse baseline KFRE scores and a higher risk of developing sustained 50% decline in eGFR or ESKD, as well as a greater prevalence of CKD-associated anemia.

Disclosures

Unrelated to this work, C.M. Clase has received consultation, advisory board membership, honoraria, or research funding from Amgen, Astellas, Baxter, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Janssen, Leo Pharma, the Ontario Ministry of Health, Pfizer, Sanofi, and, through the LiV Academy, AstraZeneca. In 2018 she co-chaired a KDIGO potassium controversies conference sponsored at arm’s length by AstraZeneca, Bayer HealthCare, Boehringer Ingelheim, Fresenius Medical Care, Relypsa, and Vifor Fresenius Medical Care. C.M. Clase also reports Research Funding: the ONTARGET and TRANSCEND Databases, which were funded by Boehringer Ingelheim; coinvestigator on the REPORT study funded by Astellas, and on the FLUID study funded by Baxter; Honoraria: University of Alberta; and Advisory or Leadership Role: ACP Journal Club associate editor, and the Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease editor-in-chief. J. Garland reports Honoraria: Alexion and Otsuka. R. Holden reports Consultancy: Otsuka and Sanofi; Research Funding: OPKO and Sanofi; and Honoraria: Otsuka and Sanofi. B. Kestenbaum reports Consultancy: Reata Pharmaceuticals; and Honoraria: Reatta Pharmaceuticals. Unrelated to this work, M.B. Lanktree has received compensation as a speaker and advisory board member for Bayer, Genzyme, Otsuka, Reata, and Sanofi. M.B. Lanktree also reports Research Funding: as a young investigator in the KRESCENT Program, a national kidney research training partnership of the Kidney Foundation of Canada, the Canadian Society of Nephrology, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; grant funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Hamilton Academic Health Sciences Organization (HAHSO), and Hamilton Health Sciences. Unrelated to this work, A. Levin has received compensation for participation as a speaker or an advisory board member or has received research grant support from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Certa, Fresenius, Janssen, Otsuka, Precision Medicine (KPMP), and Reata. A. Levin also reports Consultancy: Bayer, Chinook Therapeutics, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH); Research Funding: the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) and the Kidney Foundation of Canada; Honoraria: Bayer and the NIH; Advisory or Leadership Role: Chinook Therapeutics, GSK, the International Society of Nephrology Research Committee, Kidney Precision Medicine, KRESCENT (Kidney Scientist Education Research National Training Program), the NIDDK, and is on the DSMB for the NIDDK, University of Washington Kidney Research Institute Scientific Advisory Committee; and Other Interests or Relationships: Steering Committee ALIGN trial, DSMB Chair RESOLVE Trial (Australian Clinical Trial Network), the Canadian Society of Nephrology, CREDENCE National Coordinator from Janssen, directed to her academic team, the International Society of Nephrology, the Kidney Foundation of Canada, and NIDDK CURE Chair Steering Committee. Unrelated to this work, G. Paré has received consulting fees from Amgen, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Lexicomp, and Sanofi, and support for research through his institution from Sanofi. G. Paré also reports Research Funding: Bayer; Honoraria: Amgen, Bayer, and Sanofi; and Advisory or Leadership Role: Amgen, Bayer, and Sanofi. C. Robinson-Cohen reports Advisory or Leadership Role: CJASN. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was funded by a Physicians’ Services Incorporated Foundation grant (funding reference number 2020-1910) and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research project grant (Institute of Genetics; funding reference number 169041). Matthew B. Lanktree and this study are supported by a Kidney Foundation of Canada Kidney Research Scientist Core Education and National Training (KRESCENT) Program New Investigator Award (reference number 628478).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr. Samuel Silver and Dr. Andrew Paterson for helpful suggestions for eGFR slope analyses and mixed model analyses; Dr. Alexander Bick, Dr. Pradeep Natarajan, and Dr. Seyedeh (Maryam) Zekavat for helpful discussions; as well as Reina Ditta, Amanda Hodge, Zachary Brautigam, and Dr. Xiao (Nick) Zhang for sample processing.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Clonal Hematopoiesis and CKD Progression,” on pages 878–879.

Author Contributions

C. Vlasschaert, R. Holden, M.J. Rauh, and M.B. Lanktree were responsible for conceptualization and formal analysis; C. Vlasschaert, A.J.M. McNaughton, M. Chong, E.K. Cook, W. Hopman, J. Garland, C.M. Clase, M. Tang, A. Levin, and R. Holden were responsible for data curation; C. Vlasschaert, A.J.M. McNaughton, M. Chong, W. Hopman, B. Kestenbaum, C. Robinson-Cohen, G. Paré, R. Holden, M.J. Rauh, and M.B. Lanktree were responsible for methodology; C. Vlasschaert, M.J. Rauh, and M.B. Lanktree were responsible for funding acquisition; C. Vlasschaert, M.J. Rauh, and M.B. Lanktree performed the investigation and wrote the original draft; C. Vlasschaert, M. Chong, S.M. Moran, and M.J. Rauh performed the validation; C. Vlasschaert, B. Kestenbaum, C. Robinson-Cohen, M.J. Rauh, and M.B. Lanktree performed the visualization; C. Vlasschaert, M. Chong, E.K. Cook, B. Kestenbaum, C. Robinson-Cohen, S.M. Moran, G. Paré, C.M. Clase, M. Tang, A. Levin, R. Holden, M.J. Rauh, and M.B. Lanktree reviewed and edited the manuscript; J. Garland, G. Paré, C.M. Clase, A. Levin, R. Holden, and M.J. Rauh were responsible for resources; R. Holden, M.J. Rauh, and M.B. Lanktree supervised the project; and M.J. Rauh was responsible for project administration.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2021060774/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Figure 1. Random selection of participants from the CanPREDDICT cohort.

Supplemental Figure 2. Supplemental kidney function analyses.

Supplemental Figure 3. Comparison of CHIP prevalence by eGFR and age.

Supplemental Table 1. Characteristics of CHIP variants observed.

Supplemental Table 2. CHIP associations with variant allele fraction (VAF).

References

- 1.Jaiswal S: Clonal hematopoiesis and nonhematologic disorders. Blood 136: 1606–1614, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cull AH, Snetsinger B, Buckstein R, Wells RA, Rauh MJ: Tet2 restrains inflammatory gene expression in macrophages. Exp Hematol 55: 56–70.e13, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bick AG, Pirruccello JP, Griffin GK, Gupta N, Gabriel S, Saleheen D, et al. : Genetic interleukin 6 signaling deficiency attenuates cardiovascular risk in clonal hematopoiesis. Circulation 141: 124–131, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sano S, Oshima K, Wang Y, MacLauchlan S, Katanasaka Y, Sano M, et al. : Tet2-mediated clonal hematopoiesis accelerates heart failure through a mechanism involving the IL-1β/NLRP3 inflammasome. J Am Coll Cardiol 71: 875–886, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fidler TP, Xue C, Yalcinkaya M, Hardaway B, Abramowicz S, Xiao T, et al. : The AIM2 inflammasome exacerbates atherosclerosis in clonal haematopoiesis. Nature 592: 296–301, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bick AG, Weinstock JS, Nandakumar SK, Fulco CP, Bao EL, Zekavat SM, et al. ; NHLBI Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine Consortium : Inherited causes of clonal haematopoiesis in 97,691 whole genomes. Nature 586: 763–768, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook EK, Izukawa T, Young S, Rosen G, Jamali M, Zhang L, et al. : Comorbid and inflammatory characteristics of genetic subtypes of clonal hematopoiesis. Blood Adv 3: 2482–2486, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young AL, Challen GA, Birmann BM, Druley TE: Clonal haematopoiesis harbouring AML-associated mutations is ubiquitous in healthy adults. Nat Commun 7: 12484, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Genovese G, Kähler AK, Handsaker RE, Lindberg J, Rose SA, Bakhoum SF, et al. : Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N Engl J Med 371: 2477–2487, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steensma DP, Bejar R, Jaiswal S, Lindsley RC, Sekeres MA, Hasserjian RP, et al. : Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and its distinction from myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 126: 9–16, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, Manning A, Grauman PV, Mar BG, et al. : Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med 371: 2488–2498, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaiswal S, Natarajan P, Silver AJ, Gibson CJ, Bick AG, Shvartz E, et al. : Clonal hematopoiesis and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 377: 111–121, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawoud AAZ, Gilbert RD, Tapper WJ, Cross NCP: Clonal myelopoiesis promotes adverse outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Leukemia 36: 507–515, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaiswal S, Libby P: Clonal haematopoiesis: connecting ageing and inflammation in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 17: 137–144, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Q, Zhao K, Shen Q, Han Y, Gu Y, Li X, et al. : Tet2 is required to resolve inflammation by recruiting Hdac2 to specifically repress IL-6. Nature 525: 389–393, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sano S, Oshima K, Wang Y, Katanasaka Y, Sano M, Walsh K: CRISPR-mediated gene editing to assess the roles of Tet2 and Dnmt3a in clonal hematopoiesis and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res 123: 335–341, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vlasschaert C, Moran S, Rauh M: The myeloid-kidney interface in health and disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 323–331, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garland JS, Holden RM, Groome PA, Lam M, Nolan RL, Morton AR, et al. : Prevalence and associations of coronary artery calcification in patients with stages 3 to 5 CKD without cardiovascular disease. Am J Kidney Dis 52: 849–858, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamarche MC, Hopman WM, Garland JS, White CA, Holden RM: Relationship of coronary artery calcification with renal function decline and mortality in predialysis chronic kidney disease patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 34: 1715–1722, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garland JS, Holden RM, Ross R, Adams MA, Nolan RL, Hopman WM, et al. : Insulin resistance is associated with fibroblast growth factor-23 in stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease patients. J Diabetes Complications 28: 61–65, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerr JD, Holden RM, Morton AR, Nolan RL, Hopman WM, Pruss CM, et al. : Associations of epicardial fat with coronary calcification, insulin resistance, inflammation, and fibroblast growth factor-23 in stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol 14: 26, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garland JS, Holden RM, Hopman WM, Gill SS, Nolan RL, Morton AR: Body mass index, coronary artery calcification, and kidney function decline in stage 3 to 5 chronic kidney disease patients. J Ren Nutr 23: 4–11, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holden RM, Booth SL, Tuttle A, James PD, Morton AR, Hopman WM, et al. : Sequence variation in vitamin K epoxide reductase gene is associated with survival and progressive coronary calcification in chronic kidney disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34: 1591–1596, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levin A, Rigatto C, Brendan B, Madore F, Muirhead N, Holmes D, et al. ; CanPREDDICT investigators : Cohort profile: Canadian study of prediction of death, dialysis and interim cardiovascular events (CanPREDDICT). BMC Nephrol 14: 121, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J, Tighiouart H, Wang D, Sang Y, et al. ; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration : New creatinine- and cystatin C-based equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl J Med 385: 1737–1749, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J, Tighiouart H, Djurdjev O, Naimark D, et al. : A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA 305: 1553–1559, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tangri N, Grams ME, Levey AS, Coresh J, Appel LJ, Astor BC, et al. ; CKD Prognosis Consortium : Multinational assessment of accuracy of equations for predicting risk of kidney failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA 315: 164–174, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beutler E, Waalen J: The definition of anemia: what is the lower limit of normal of the blood hemoglobin concentration? Blood 107: 1747–1750, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chowdhury MZI, Turin TC: Variable selection strategies and its importance in clinical prediction modelling. Fam Med Community Health 8: e000262, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fishbane S, Coyne DW: How I treat renal anemia. Blood 136: 783–789, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pergola PE, Devalaraja M, Fishbane S, Chonchol M, Mathur VS, Smith MT, et al. : Ziltivekimab for treatment of anemia of inflammation in patients on hemodialysis: results from a phase 1/2 multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 32: 211–222, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Izzo F, Lee SC, Poran A, Chaligne R, Gaiti F, Gross B, et al. : DNA methylation disruption reshapes the hematopoietic differentiation landscape. Nat Genet 52: 378–387, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luis TC, Wilkinson AC, Beerman I, Jaiswal S, Shlush LI: Biological implications of clonal hematopoiesis. Exp Hematol 77: 1–5, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buscarlet M, Provost S, Zada YF, Barhdadi A, Bourgoin V, Lépine G, et al. : DNMT3A and TET2 dominate clonal hematopoiesis and demonstrate benign phenotypes and different genetic predispositions. Blood 130: 753–762, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Zeventer IA, de Graaf AO, Wouters HJCM, van der Reijden BA, van der Klauw MM, de Witte T, et al. : Mutational spectrum and dynamics of clonal hematopoiesis in anemia of older individuals. Blood 135: 1161–1170, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guermouche H, Ravalet N, Gallay N, Deswarte C, Foucault A, Beaud J, et al. : High prevalence of clonal hematopoiesis in the blood and bone marrow of healthy volunteers. Blood Adv 4: 3550–3557, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Busque L, Sun M, Buscarlet M, Ayachi S, Feroz Zada Y, Provost S, et al. : High-sensitivity C-reactive protein is associated with clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential. Blood Adv 4: 2430–2438, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coombs CC, Zehir A, Devlin SM, Kishtagari A, Syed A, Jonsson P, et al. : Therapy-related clonal hematopoiesis in patients with non-hematologic cancers is common and associated with adverse clinical outcomes. Cell Stem Cell 21: 374–382.e4, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindsley RC, Saber W, Mar BG, Redd R, Wang T, Haagenson MD, et al. : Prognostic mutations in myelodysplastic syndrome after stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 376: 536–547, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fuster JJ, MacLauchlan S, Zuriaga MA, Polackal MN, Ostriker AC, Chakraborty R, et al. : Clonal hematopoiesis associated with TET2 deficiency accelerates atherosclerosis development in mice. Science 355: 842–847, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sano S, Wang Y, Yura Y, Sano M, Oshima K, Yang Y, et al. : JAK2 V617F -mediated clonal hematopoiesis accelerates pathological remodeling in murine heart failure. JACC Basic Transl Sci 4: 684–697, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yura Y, Miura-Yura E, Katanasaka Y, Min KD, Chavkin N, Polizio AH, et al. : The cancer therapy-related clonal hematopoiesis driver gene Ppm1d promotes inflammation and non-ischemic heart failure in mice. Circ Res 129: 684–698, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y, Sano S, Yura Y, Ke Z, Sano M, Oshima K, et al. : Tet2-mediated clonal hematopoiesis in nonconditioned mice accelerates age-associated cardiac dysfunction. JCI Insight 5: e135204, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fuster JJ, Zuriaga MA, Zorita V, MacLauchlan S, Polackal MN, Viana-Huete V, et al. : TET2-loss-of-function-driven clonal hematopoiesis exacerbates experimental insulin resistance in aging and obesity. Cell Rep 33: 108326, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim PG, Niroula A, Shkolnik V, McConkey M, Lin AE, Słabicki M, et al. : Dnmt3a-mutated clonal hematopoiesis promotes osteoporosis. J Exp Med 218: e20211872, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abegunde SO, Buckstein R, Wells RA, Rauh MJ: An inflammatory environment containing TNFα favors Tet2-mutant clonal hematopoiesis. Exp Hematol 59: 60–65, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cai Z, Kotzin JJ, Ramdas B, Chen S, Nelanuthala S, Palam LR, et al. : Inhibition of inflammatory signaling in Tet2 mutant preleukemic cells mitigates stress-induced abnormalities and clonal hematopoiesis. Cell Stem Cell 23: 833–849.e5, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hormaechea-Agulla D, Matatall KA, Le DT, Kain B, Long X, Kus P, et al. : Chronic infection drives Dnmt3a-loss-of-function clonal hematopoiesis via IFNγ signaling. Cell Stem Cell 28: 1428–1442.e6, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hecker JS, Hartmann L, Rivière J, Buck MC, van der Garde M, Rothenberg-Thurley M, et al. : CHIP & HIPs: clonal hematopoiesis is common in patients undergoing hip arthroplasty and is associated with autoimmune disease. Blood : 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arends CM, Weiss M, Christen F, Eulenberg-Gustavus C, Rousselle A, Kettritz R, et al. : Clonal hematopoiesis in patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Haematologica 105: e264–e267, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rossi M, et al. : Clinical relevance of clonal hematopoiesis in persons aged ≥80 years. Blood 138: 2093-2105, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Greigert, H, Mounier M, Arnould L, Creuzot-Garcher C, Ramon A, Martin L, et al. : Hematological malignancies in giant cell arteritis: a French population-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 60: 5408–5412, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dorsheimer L, Assmus B, Rasper T, Ortmann CA, Ecke A, Abou-El-Ardat K, et al. : Association of mutations contributing to clonal hematopoiesis with prognosis in chronic ischemic heart failure. JAMA Cardiol 4: 25–33, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pascual-Figal DA, Bayes-Genis A, Díez-Díez M, Hernández-Vicente Á, Vázquez-Andrés D, de la Barrera J, et al. : Clonal hematopoiesis and risk of progression of heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 77: 1747–1759, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mas-Peiro S, Hoffmann J, Fichtlscherer S, Dorsheimer L, Rieger MA, Dimmeler S, et al. : Clonal haematopoiesis in patients with degenerative aortic valve stenosis undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Eur Heart J 41: 933–939, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.