Abstract

Organically modified silica (ORMOSIL) nanoparticles (NPs) are widely used in biomedicine. However, their cell uptake process has not yet been characterised in detail. Here, we investigated the mechanism underlying endocytosis and subcellular localisation of ORMOSIL NPs. Exposure to ORMOSIL NPs induced a decrease in cell viability and increase in lactate dehydrogenase release in a dose-dependent manner in A549 cells. Once internalised, ORMOSIL NPs were translocated from early endosomes to the lysosomes, where they accumulated. Furthermore, deficiency of autophagosomal/lysosomal fusion failed to block lysosomal localisation of ORMOSIL NPs, suggesting that autophagy was not involved in the final lysosomal accumulation of ORMOSIL NPs. Meanwhile, an inhibitor of caveolae-mediated endocytosis, rather than inhibitors of phagocytosis or clathrin-mediated endocytosis, succeeded in blocking ORMOSIL NP cell uptake, indicating the involvement of caveolae-mediated endocytosis. Together, these results provide a new understanding of the toxicity, and suggest better biomedical applications, of ORMOSIL NPs.

Organically modified silica (ORMOSIL) nanoparticles (NPs) are widely used in biomedicine.

1. Introduction

Engineered nanoparticles (NPs) (particles with a diameter < 100 nm), such as silica nanoparticles (SiNPs), are widely used in various applications.1 Although use of these NPs has many advantages, public concerns about their safety have been raised following increasing commercialisation of SiNP-associated products. It has been reported that responses stimulated by NP exposure may be related to their accumulation within cells after endocytosis.2 Characterisation of the mechanism of NP cellular uptake could improve the sensitivity and efficiency in tumour diagnosis and therapy.3 Furthermore, these investigations may provide strategies for attenuating or even abolishing SiNP-triggered cytotoxicity.

Lysosomes are acidic cellular compartments, which contain more than 60 types of hydrolases.4 They play an important function in cellular elimination of NPs, either through dissolution, degradation, or by exocytosis.5 Some NPs, including SiNPs, enter cells and accumulate in lysosomes via different transport mechanisms.6,7 Lysosomal capture and accumulation after NP exposure has led to lysosomal dysfunctions, followed by a cell death response. SiNPs block autophagosomal degradation via lysosomal damage in phagocytes and alveolar epithelial cells, resulting in autophagy dysfunction, a common mechanism responsible for NP-induced cytotoxicity.8,9 Lysosomal acidification is a critical factor for lysosome maturation and activation of most lysosomal enzymes, and is necessary for lysosomal degradation.10 For instance, after exposure to silver NPs, the lysosomal pH is elevated, and may play a role in silver NP agglomeration and subsequent cellular damage in A549 cells.11 Other NPs, such as gold NPs or rare earth NPs, also disrupt lysosomal function by targeting acidification.12,13 The association between lysosomal accumulation and NP-triggered cytotoxicity presents difficulties in characterising NP-stimulated cellular damage, as well as in developing effective strategies for the use of these NPs in medical treatments.14

Several factors (e.g. size, shape, and surface function) are critical in endocytic pathways.15,16 For example, a systematic study of cellular uptake showed that smaller zinc oxide NPs were internalised into cells via clathrin-mediated endocytosis, while larger zinc oxide NPs entered cells via several pathways.17 Not only NPs, but also the microenvironment, can affect the endocytic pathway. In the presence of epidermal growth factor (EGF), cellular uptake of polystyrene NPs occurs via clathrin-mediated endocytosis, whereas in the absence of EGF, uptake of polystyrene NPs does not involve this process.18 Taken together, the results of different NP endocytic studies have produced variable results. In the present study, we used organically modified silica (ORMOSIL) NPs, which is a type of SiNP with large pores in the matrix that possesses good biocompatibility and applicability in biomedicine. Whether other types of SiNPs share the common mechanism underlying endocytosis and its localisation warrants further research.

Here, we investigated the subcellular location of ORMOSIL NPs and the underlying mechanism of translocation. The results showed that ORMOSIL NPs accumulated in lysosomes. Furthermore, early endosomal/lysosomal rather than autophagosomal/lysosomal fusion mediated the lysosomal localisation of ORMOSIL NPs. Finally, ORMOSIL NP-associated endocytosis was inhibited by methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), an inhibitor of lipid raft caveolae-mediated endocytosis. Taken together, our study provides detailed insight into the mechanisms underlying ORMOSIL NP-associated endocytosis and subcellular localisation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plasmids, reagents, and antibodies

The plasmids GFP-LC3, CFP-LC3 and YFP-LAMP1 were gifts from Dr Wei Liu (Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology; Zhejiang University School of medicine). The ORMOSIL nanoparticles were a gift from Dr Jun Qian (State Key Laboratory of Modern Optical Instrumentation; Zhejiang University) and suspended in Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS). The blocking serum and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit second antibody were from Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology.

The following primary antibodies were used: anti-EEA1 (Cell signaling, 3288), anti-LAMP1 (Cell signaling, 9091), anti-LC3 (Sigma, L7543).

2.2. Synthesis and characterization of ORMOSIL nanoparticles

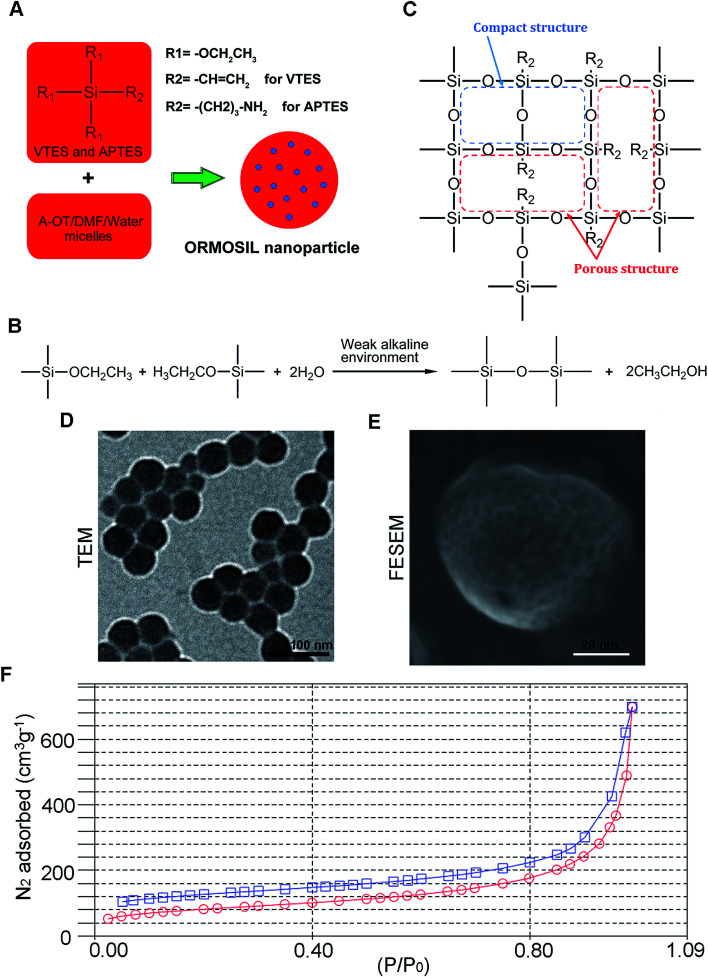

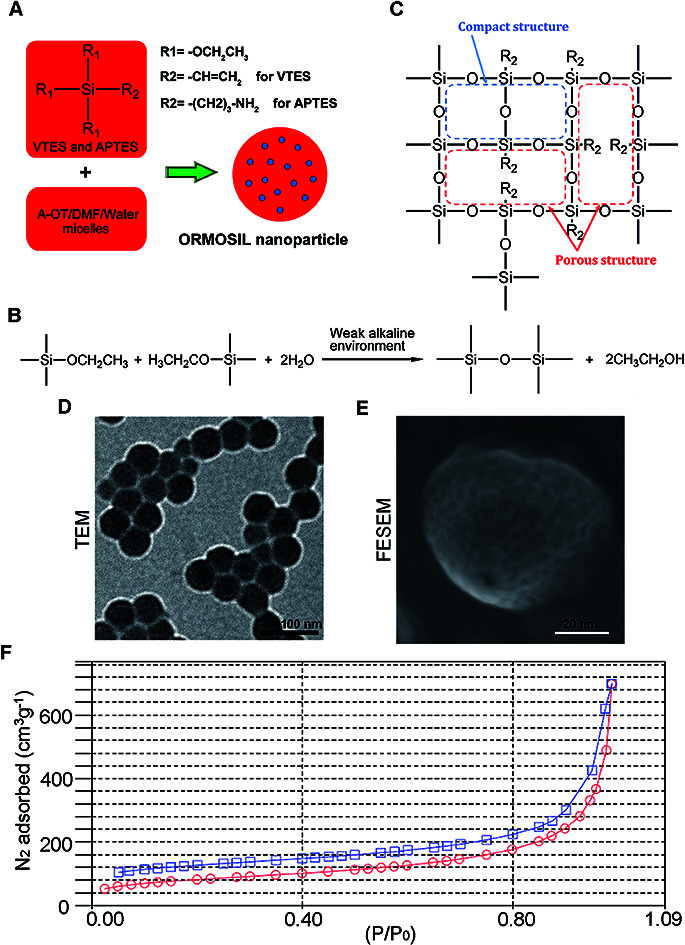

Fig. 1A shows the synthesis protocol of ORMOSIL nanoparticles. In brief, the micelles was used to dissolve a certain number of sulfobernteinsaure-bis-2-ethylhexy ester natriumsalz (Aerosol-OT) and 1-butanol in total 10 mL of DI water under energetic vigorous magnetic stirring. Among which, A-OT was used as surfactant to encapsulate the Nile red molecules into nano micelles as cores.19 The SiO2 shell would further grow on the surface of the cores.20 100 μL triethoxyvinylsilane triethoxyvinylsilan (VTES) was added to micellar system mentioned above after 30 minutes, and was stirred for another one hour. Then, silica nanoparticles were precipitated after addition of 10 μL of (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) and stirred at room temperature for another 20 h. The molecular structure of VTES and APTES were shown in Fig. 1A. They were used to provide Si and O for the SiO2 shell. Moreover, the amino of APTES was used to provide a weak alkine environment. As shown in Fig. 1B, the group R1s on VTES and APTES would react with each other in the weak alkine environment, while the group R2s would not participate in the reaction, leading to a porous SiO2 shell formed outside of the Nile red@A-OT (Fig. 1C). After successful formation of the silica nanoparticles, excess Aerosol-OT, co-surfactant 1-butanol, VTES and APTES were removed by dialyzing the solution against DI water in a 12–14 kDa cutoff cellulose membrane for 50 h. The method to synthesize SiO2 nanoparticles in this paper was first reported in 2003, and was used to encapsulate photosensitiser for photodynamic therapy.20,21 It was stated that the molecular oxygen around the SiO2 nanoparticles could diffuse into the nanoparticles and interact with the photosensitisers to form singlet oxygen. The generated singlet oxygen could also get outside of the nanoparticles. The results indicated the porous matrix of the SiO2 nanoparticles. To directly characterize this nanoparticle, we also performed TEM, FESEM images as well as N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of ORMOSIL nanoparticles (Fig. 1D–F). Finally, the dialyzed solution was then filtered by a 0.45 μm filter for further experiments. Nile red was used to mark SiNPs.22

Fig. 1. The synthesis and characterization of ORMOSIL NPs. (A–C) The schematic illustration of the synthesis of ORMOSIL nanoparticle. (D) ORMOSIL nanoparticle were imaged by TEM. (E) ORMOSIL NPs were imaged by FESEM image. (F) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of ORMOSIL NPs.

2.3. Cell culture

The human lung epithelial cells (A549) cells purchased from Shanghai Cell Bank grows in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco). The cell were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 as well as 95% air. Before ORMOSIL nanoparticles exposure, cells was incubated for 24 h.

2.4. Cell viability analysis

The effects of ORMOSIL nanoparticles on cell viability were determined by Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) reagent (DOJINDO, CK04). In brief, 10 μL of CCK8 was added to each well of 96-well and incubated for another 2 h at 37 °C. The optical density (OD) at 450 nm was assessed by a Microplate Reader (Thermo Scientific, Varioskan Flash).

2.5. Immunofluorescence staining

The cells cultured on coverslips exposed to ORMOSIL nanoparticles for indicated condition, then were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at 4 °C, followed by permeabilization with 0.25% Triton X-100 for another 15 min at 4 °C. The non-specific binding was blocked by goat serum (Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology, #ZLI-9021) at room temperature for 1.5 h. Then the cells were incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight (anti-EEA1, 1 : 100; anti-LAMP1, 1 : 500), then followed by incubation with corresponding second antibody for 1 h. The coverslips were further stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Sigma, D9542) for 10 min to visualize nuclei. Finally, the cover slip was mounted onto a glass slide with 87% glycerol, and the immunofluorescence staining was imaged by confocal microscope (Nikon, A1R).

2.6. Transmission electron microscopy

After treatment as indicated, A549 cells were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C overnight. After dehydration, ultrathin section was embedded and stained with uranyl acetate/lead citrate. Image was captured under a transmission electron microscopy (FEI Company, TECNAI 10).

2.7. Measurement of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release

The release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was measured in the culture supernatants by measuring the LDH activity with the LDH assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng) following the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, cells were collected and incubated with reaction solution configured in a certain ratio at 37 °C for 15 min, then added 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine at 37 °C for 15 min, finally added 0.4 mM NaOH at room temperature for 5 min. The absorbance was measured at a test wavelength of 450 nm and calculated LDH activity according to formula.

2.8. Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA was used to determine statistical significance for multiple groups analysis. For lysosome volume, Wilcoxon rank sum test was used. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.0. All quantitative data are presented as means ± SD. A P value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. ORMOSIL nanoparticles enter A549 cells and induce cytotoxicity

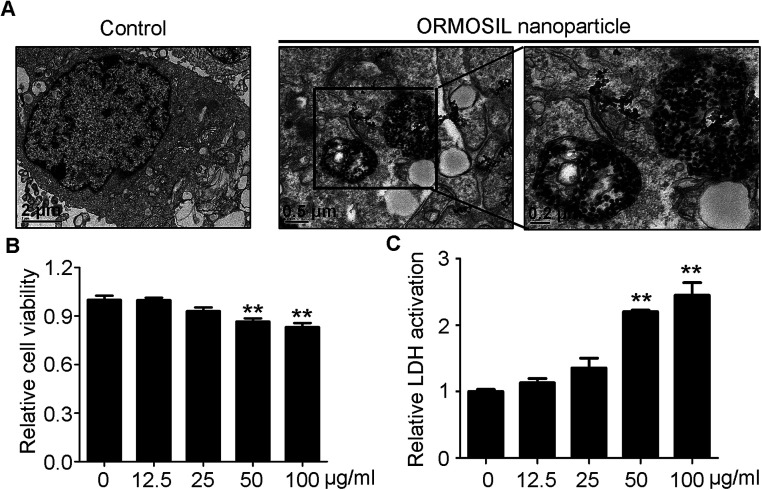

ORMOSIL NPs were prepared and characterised as described in the Methods section (Fig. 1). To determine whether ORMOSIL NPs enter A549 cells, we exposed cells to 50 μg mL−1 of ORMOSIL NPs for 24 h, and then imaged them using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The results showed that ORMOSIL NPs localised within cells in organelles with a single membrane structure (Fig. 2A). The cytotoxicity of ORMOSIL NPs was then determined after treatment at different doses for 24 h. Exposure to 50 or 100 μg mL−1 ORMOSIL NPs significantly reduced cell viability, whereas low concentrations (12.5 and 25 μg mL−1) failed to alter cell viability (Fig. 2B). ORMOSIL NP toxicity in A549 cells was also investigated using the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay. The results showed that LDH release increased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2. The cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of ORMOSIL NPs. (A) The cellular location of ORMOSIL nanoparticle in A549 cells was imaged by TEM. (B) A549 cells were treated with ORMOSIL NPs at indicated concentrations of for 24 h, and cell viability was measured by CCK-8. (C) A549 cells were exposed to ORMOSIL NPs as indicated in (D), then the LDH activation was measured and normalized to control.

3.2. ORMOSIL NPs accumulate in lysosomes independently of autophagosomal/lysosomal fusion

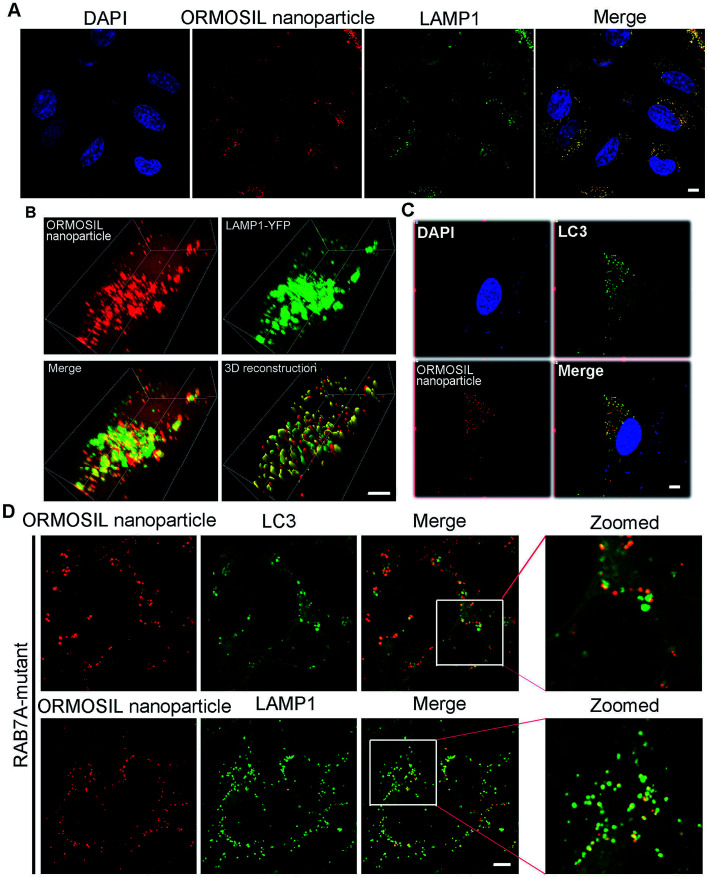

To further detect whether ORMOSIL NPs accumulated in lysosomes, we used a co-localisation assay of ORMOSIL NPs with lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1), a lysosome marker. ORMOSIL NPs were co-localised with LAMP1, suggesting that ORMOSIL NPs accumulated in engulfed lysosomes (Fig. 3A). We also used A549 cells transiently expressing YFP-LAMP1 as a marker of lysosomes, which further confirmed that ORMOSIL NPs were localised in lysosomes (Fig. 3B). Macroautophagy, hereafter called autophagy, is a “self-eating” process involving the engulfing of cytoplasmic protein or organelles into autophagosomes, followed by fusion with lysosomes and subsequent degradation. Autophagy normally acts as a survival mechanism preventing cell death, but excessive activation may lead to cell death. Almost all NPs can trigger autophagy, and it is a critical mechanism in NP-induced toxicity.23 Therefore, we investigated the role of this pathway in ORMOSIL NP lysosomal accumulation. We stained A549 cells exposed to ORMOSIL NPs with microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3), an autophagosome marker, and found that ORMOSIL NPs were co-localised with LC3, indicating that ORMOSIL NPs were located in autophagosomes or autolysosomes (Fig. 3C). Moreover, we detected co-localisation of ORMOSIL NPs with LC3 or LAMP1 under deficient autophagosomal/lysosomal fusion using a RAB7A mutant. Once autophagosomal/lysosomal fusion was impaired, ORMOSIL NPs co-localised with LAMP1 rather than LC3, indicating that autophagosomal/lysosomal fusion did not mediate ORMOSIL NP lysosomal localisation (Fig. 3D). It has been reported that SiNPs inhibit autophagosomal/lysosomal fusion and accumulate in lysosomes.6 This study supported the conclusion that ORMOSIL NPs were transported to lysosomes independently of the autophagy/lysosome system, given the absence of inhibition of autophagosomal/lysosomal fusion. However, Remaut et al. reported that cytoplasmic and subsequent lysosomal capturing of NPs can occur via an autophagy response.24 Therefore, whether autophagosomal/lysosomal fusion is implicated in NP-associated lysosomal location and is NP dependent requires further study.

Fig. 3. ORMOSIL NPs accumulated in lysosome independent of autophagosome-lysosome fusion. (A) A549 cells treated with ORMOSIL NPs at 50 μg mL−1 for 24 h were stained with LAMP1 by direct IF. (B) A549 cells transiently expressing YFP-LAMP1 were treated with ORMOSIL NPs at 50 μg mL−1 for 24 h, then the cells were fixed and imaged by confocal microscopy. The 3D structure were restructured with Imaris software. (C) A549 cells treated with ORMOSIL NPs at 50 μg mL−1 for 24 h were stained with LC3 by direct IF. (D) RAB7A-mutant cells were treated with ORMOSIL NPs at 50 μg mL−1 for 24 h, and were stained with LC3 or LAMP1. Scale bars: 5 μm.

3.3. ORMOSIL NPs accumulate in lysosomes via the endosome pathway

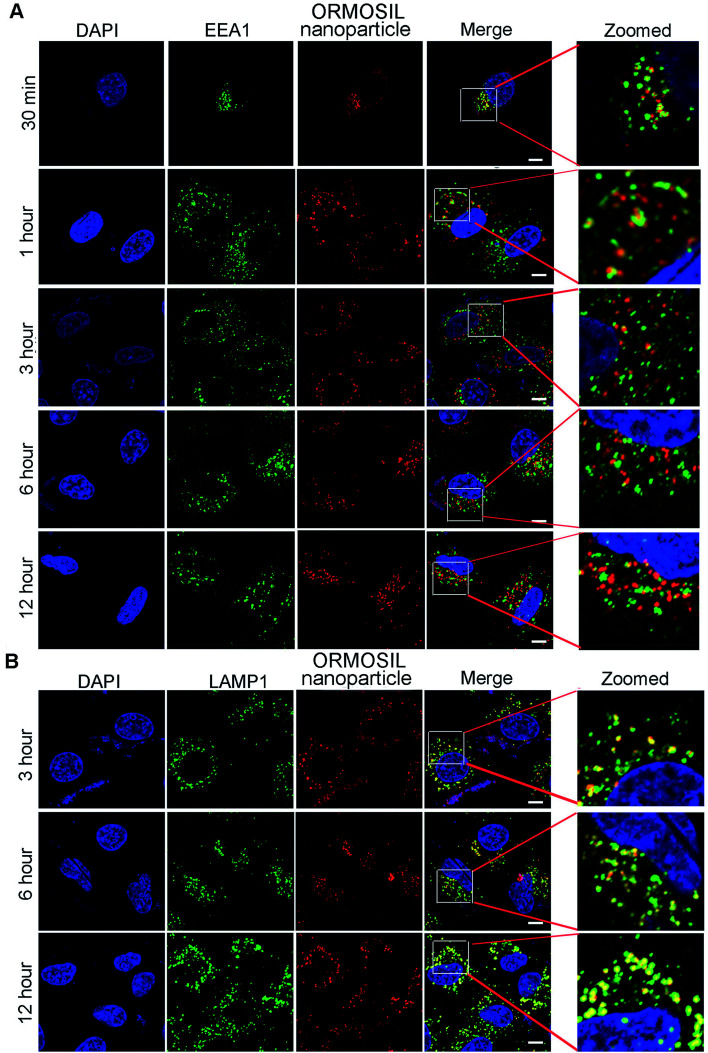

We then monitored the subcellular localisation of ORMOSIL nanoparticles after different NP exposure durations. ORMOSIL NPs co-localised with early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1), an early endosome marker, after 30 min of treatment (Fig. 4A). With extended exposure times, increasing amounts of ORMOSIL NPs were co-localised with LAMP1, accompanied by decreased co-localisation with EEA1 (Fig. 4A and B), suggesting a translocation from early endosomes to lysosomes. These results indicated that ORMOSIL NPs entered lysosomes via the endosomal/lysosomal pathway. The delivery of endocytosed cargos to lysosomes mainly occurred via endosomal/lysosomal fusion.25 Because endosomes become lysosomes through maturation, additional studies of the detailed mechanism of translocation from endosomes to lysosomes are needed.26

Fig. 4. ORMOSIL NPs located in lysosomes via endosomes. (A) A549 cells treated with ORMOSIL NPs for indicated time then stained with EEA1. (B) A549 cells treated with ORMOSIL NPs for indicated time then stained with LAMP1. Scale bar: 5 μm.

3.4. Caveolae was involved in ORMOSIL nanoparticles-associated endocytosis

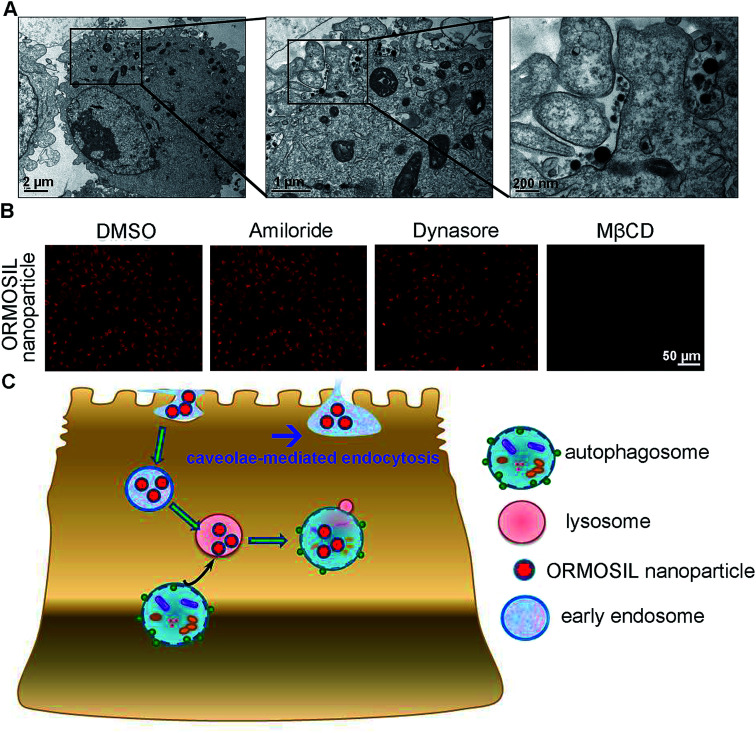

Next, we characterised the endocytic pathway of ORMOSIL NP uptake. After being added to a biological system, NPs adhere to cells and enter cells via different pathways. In general, phagocytosis is a critical endocytic mechanism for relatively large (e.g. micrometre-sized) particles.27 In addition, this process is mainly used to uptake cell debris, pathogens, and dead cells.28 In clathrin-mediated endocytosis, the binding of receptors with bound ligand leads to the recruitment and formation of clathrin inside the plasma membrane.29 Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is the most common endocytic pathway for viruses.30 Some NPs (e.g. gold, silver, and zinc oxide NPs) enter cells through this pathway.16,17,31 Another common mechanism for NP uptake is caveolin-dependent endocytosis, which involves the assembly of the hairpin-like caveolin coats. Inhibitors of caveolae-mediated endocytosis have been shown to decrease the uptake of several NPs.32,33 To directly view ORMOSIL NP uptake by the cell membrane, we exposed A549 cells to 50 μg mL−1 ORMOSIL NPs for 5 min, followed by TEM observation. ORMOSIL NPs were surrounded by the cell membrane, forming caveolae-like structures (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, we investigated the roles of three classic endocytic pathways (i.e. phagocytosis, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, and caveolae-mediated endocytosis) on ORMOSIL NP uptake using corresponding inhibitors, and found that MβCD, rather than dynasore or amiloride, blocked ORMOSIL NP cellular uptake, indicating that caveolae-mediated endocytosis was involved in ORMOSIL NP-associated endocytosis (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. Caveolae-mediated endocytosis is involved in ORMOSIL NPs cellular location. (A) A549 cells was exposed to ORMOSIL NPs at 50 μg mL−1 for 5 min, then was imaged by TEM. (B) A549 cells were treated with ORMOSIL NPs at 50 μg mL−1 for 12 h in the absence or presence of amiloride (an inhibitor of phagocytosis, 100 μM), dynasore (an inhibitor of clathrin-mediated endocytosis, 100 μM) or MβCD (an inhibitor of caveolae-mediated endocytosis, 1 mM), then were imaged by microscope. (C) A scheme diagram deciphering the process of cell uptake and subsequent cellular location of ORMOSIL NPs.

4. Conclusion

This study provides a detail description of the process of ORMOSIL NP cell uptake. After endocytosis in a caveolae-mediated manner, ORMOSIL NPs enter early endosomes, and are then translocated to lysosomes. Although autophagy is a critical response to NP treatment, it may not be involved in lysosomal accumulation of ORMOSIL NPs (Fig. 5C). This study provides a better understanding of the potential toxicity, as well as better applications, of ORMOSIL NPs in biomedicine.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thanks Dr Bo liu for providing RAB7A-mutant 293T cells. We thanks Siyuan Liu in Nantong University Analysis & Testing Center for FESEM images. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81703255, 21607082); Nantong Jiangsu scientific research project (MS12017014-8); Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20160414), Scientific Research Project of Wuxi Health and Family Planning Commission (Q201733) and The Yong Medical Talents of wuxi (QNRC036).

References

- Wang Y. Zhao Q. Han N. Bai L. Li J. Liu J. Che E. Hu L. Zhang Q. Jiang T. Wang S. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in drug delivery and biomedical applications. Nanomedicine. 2015;11:313–327. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartneck M. Keul H. A. Singh S. Czaja K. Bornemann J. Bockstaller M. Moeller M. Zwadlo-Klarwasser G. Groll J. Rapid uptake of gold nanorods by primary human blood phagocytes and immunomodulatory effects of surface chemistry. ACS Nano. 2010;4:3073–3086. doi: 10.1021/nn100262h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao D. Lu M. M. Zhao Y. W. Zhang F. Tan Y. F. Zheng X. Pan Y. Xiao X. A. Wang Z. Dong W. F. Li J. Chen L. The shape effect of magnetic mesoporous silica nanoparticles on endocytosis, biocompatibility and biodistribution. Acta Biomater. 2017;49:531–540. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H. Ren D. Lysosomal physiology. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2015;77:57–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021014-071649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich E. Cellular elimination of nanoparticles. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016;46:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutz I. Lopez-Hernandez T. Gao Q. Puchkov D. Jabs S. Nordmeyer D. Schmudde M. Ruhl E. Graf C. M. Haucke V. Lysosomal Dysfunction Caused by Cellular Accumulation of Silica Nanoparticles. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:14170–14184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.710947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. J. Hartono D. Ong C. N. Bay B. H. Yung L. Y. Autophagy and oxidative stress associated with gold nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2010;31:5996–6003. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. Yu Y. Lu K. Yang M. Li Y. Zhou X. Sun Z. Silica nanoparticles induce autophagy dysfunction via lysosomal impairment and inhibition of autophagosome degradation in hepatocytes. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017;12:809–825. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S123596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X. Wei S. Li Z. Lin C. Zhu Z. Sun D. Bai R. Qian J. Gao X. Chen G. Xu Z. Autophagic flux blockage in alveolar epithelial cells is essential in silica nanoparticle-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:127. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1340-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson S. M. Axonal transport and maturation of lysosomes. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2018;51:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2018.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyayama T. Matsuoka M. Involvement of lysosomal dysfunction in silver nanoparticle-induced cellular damage in A549 human lung alveolar epithelial cells. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2016;11:1. doi: 10.1186/s12995-016-0090-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X. Wu Y. Jin S. Tian Y. Zhang X. Zhao Y. Yu L. Liang X. J. Gold nanoparticles induce autophagosome accumulation through size-dependent nanoparticle uptake and lysosome impairment. ACS Nano. 2011;5:8629–8639. doi: 10.1021/nn202155y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R. Ji Z. Qin H. Kang X. Sun B. Wang M. Chang C. H. Wang X. Zhang H. Zou H. Nel A. E. Xia T. Interference in autophagosome fusion by rare earth nanoparticles disrupts autophagic flux and regulation of an interleukin-1beta producing inflammasome. ACS Nano. 2014;8:10280–10292. doi: 10.1021/nn505002w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdenx M. Daniel J. Genin E. Soria F. N. Blanchard-Desce M. Bezard E. Dehay B. Nanoparticles restore lysosomal acidification defects: Implications for Parkinson and other lysosomal-related diseases. Autophagy. 2016;12:472–483. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1136769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. Gao H. Bao G. Physical Principles of Nanoparticle Cellular Endocytosis. ACS Nano. 2015;9:8655–8671. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b03184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brkic Ahmed L. Milic M. Pongrac I. M. Marjanovic A. M. Mlinaric H. Pavicic I. Gajovic S. Vinkovic Vrcek I. Impact of surface functionalization on the uptake mechanism and toxicity effects of silver nanoparticles in HepG2 cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017;107:349–361. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2017.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. M. Kim M. K. Paek H. J. Choi S. J. Oh J. M. Stable fluorescence conjugation of ZnO nanoparticles and their size dependent cellular uptake. Colloids Surf., B. 2016;145:870–877. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phuc L. T. M. Taniguchi A. Epidermal Growth Factor Enhances Cellular Uptake of Polystyrene Nanoparticles by Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:1301. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriagada F. Osseo-Asare K. Synthesis of nanosize silica in aerosol OT reverse microemulsions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1995;170:8–17. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1995.1064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy I. Ohulchanskyy T. Y. Pudavar H. E. Bergey E. J. Oseroff A. R. Morgan J. Dougherty T. J. Prasad P. N. Ceramic-based nanoparticles entrapping water-insoluble photosensitizing anticancer drugs: a novel drug-carrier system for photodynamic therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:7860–7865. doi: 10.1021/ja0343095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D. Zhang H. Chu L. Zhao X. Qian J. Photosensitizer doped colloidal mesoporous silica nanoparticles for three-photon photodynamic therapy. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2015;47:3081–3090. doi: 10.1007/s11082-015-0196-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J. Li X. Wei M. Gao X. Xu Z. He S. Bio-molecule-conjugated fluorescent organically modified silica nanoparticles as optical probes for cancer cell imaging. Opt. Express. 2008;16:19568–19578. doi: 10.1364/OE.16.019568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. Ju D. The Role of Autophagy in Nanoparticles-Induced Toxicity and Its Related Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018;1048:71–84. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-72041-8_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remaut K. Oorschot V. Braeckmans K. Klumperman J. De Smedt S. C. Lysosomal capturing of cytoplasmic injected nanoparticles by autophagy: an additional barrier to non viral gene delivery. J. Controlled Release. 2014;195:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzio J. P. Gray S. R. Bright N. A. Endosome-lysosome fusion. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2010;38:1413–1416. doi: 10.1042/BST0381413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott C. C. Vacca F. Gruenberg J. Endosome maturation, transport and functions. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014;31:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson J. A. Shaping cups into phagosomes and macropinosomes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:639–649. doi: 10.1038/nrm2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai S. Miyazaki T. A scavenging system against internal pathogens promoted by the circulating protein apoptosis inhibitor of macrophage (AIM) Semin. Immunopathol. 2018;40:567–575. doi: 10.1007/s00281-018-0717-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy M. M. Ma R. Ravindra N. G. Berro J. Molecular mechanisms of force production in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. FEBS Lett. 2018;592:3586–3605. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaksonen M. Roux A. Mechanisms of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018;19:313–326. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng C. T. Tang F. M. Li J. J. Ong C. Yung L. L. Bay B. H. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis of gold nanoparticles in vitro. Anat. Rec. 2015;298:418–427. doi: 10.1002/ar.23051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Twomey M. Machado C. Gomez G. Doshi M. Gesquiere A. J. Moon J. H. Caveolae-mediated endocytosis of conjugated polymer nanoparticles. Macromol. Biosci. 2013;13:913–920. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201300030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetten M. Gulumian M. Differences in uptake of 14nm PEG-liganded gold nanoparticles into BEAS-2B cells is dependent on their functional groups. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2018;363:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2018.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]