Abstract

Purpose

Based on trait activation theory, this study validates the boundary effect of perceived organizational support (POS) on employee empowerment (EE) to sustain employee’s taking charge behaviour (TCB). It hypothesizes that EE has a strongly significant and positive relationship with TCB when POS is high.

Methodology

The authors selected a time-lagged cross-sectional study and collected data from two sources in manufacturing firms in China where 290 team members and 56 supervisors participated in the survey. In a questionnaire, team members self-reported employee empowerment, taking charge behaviour, and perceived organizational support, whereas supervisors rated employees’ taking charge behaviour at individual-level to avoid common method bias. In addition, for meeting the study objectives statistically, we used SPSS-Process Macro for hypotheses testing.

Findings

The study findings were significant, in which employee empowerment demonstrated positive relationship with TCB under the boundary condition of POS but under low POS. This empirical result endorses that employee empowerment accelerated by perceptions of low organizational support demonstrates a positive impact on the development of taking charge behaviour.

Practical Implications

Receivers’ reactions to organizational support are not constantly positive; sometimes, they might feel vulnerable or incapable, and sometimes “overhelped”. Our study outcomes extend these streams of work by concentrating on support from the organization and authenticating an exclusive outline associating employee empowerment with perceived organizational support on employee’s taking charge behaviour- specifically organizations might, rather counterintuitively, attain greater levels of empowered employee’s taking charge behaviour by delivering less is more-oriented organizational support programs. More specifically, it is not always high, but sometimes low POS performs as a resilient situational factor or contextual moderator that is capable of activating and encouraging employee empowerment on their taking charge behaviour.

Originality/Value

This study highlights the importance of taking charge as trait-relevant behaviour by empowered employees (a trait in our case) and organizational support as a trait-relevant cue for sustainable performance in the manufacturing industry of China.

Keywords: employee empowerment practice, perceived organizational support, taking charge behaviour, trait activation theory

Introduction

The pursuit of sustainable performance and competitive advantage is always a trending issue for scholars and practitioners alike. Firms are undergoing immediate changes in the corporate environment.1 Worldwide, many renowned companies, for example, Yahoo, BlackBerry, and Nokia, have faced defeat in this sustainable environment. One of the primary reasons that leads to failure, according to Morrison and Phelps,2 is the managers cannot supervise and manage these challenges by themselves. Firms are gradually relying on their workers to discover and deal with regular work-related problems and concerns.3 Therefore, defining how to stimulate sustainable change-oriented behaviours from workers has drawn growing research attention.4,5 Because, it promotes exploration of new and better ways of getting things done, or trying to unleash hidden potential in people or situations, which eventually leads to competitive advantage. Amongst different types of sustainable change-oriented behaviours, taking charge behaviour is crucial for the organization’s sustainable performance as it “involves employees'” voluntary and creative efforts to effect organizationally functional change with respect to how work is executed within the contexts of their jobs, work units, or organizations,2 which is aimed at sustained progress.

Although the workers’ taking charge behaviours are essential to firms in the unpredictable and unstable organizational environment, they have received inadequate research consideration. In this study, we intended to investigate the predecessors of workers taking charge. Past studies have discovered that traits-like factors or individual traits, for instance, self-actualization,6 psychological ownership;7 personal motivation, ie prosocial motivation and work engagement;8,9 and leadership quality eg, LMX quality7 can increase workers’ taking charge behaviours. Nevertheless, limited research has drawn sustainable HRM’s perspective to investigate its role in fostering the workers’ taking charge behaviours.

In the workplace context, HRM practices are generally known as a cure to encouraging or discouraging employee behaviours10 and are accountable for an organization’s sustainable growth and competitive advantage.11 Sustainable HRM, which was described as “the utilization of human resource management tools to help embed a sustainability strategy in the organization and the creation of a human resource management system that contributes to the sustainable performance of the firm”,12 might be a catalyst to encourage workers to take charge quite often. Therefore, we aspired to discover the influence of employee empowerment practice, which is a certain form of sustainable HR practice,13 on the workers’ taking charge behaviours in this research. Empowerment is a managerial tool that is intended for an organization’s benefits and can be promoted by management to derive the benefits of empowered employees.14 And according to Conger and Kanungo,15 empowerment is a form of internal drive beneficial to fostering change-oriented behaviour (eg, taking charge).

To examine the association between employee empowerment practice and the workers’ taking charge behaviours, we developed a conceptual framework by invoking the trait activation theory. Amongst the constructs in the theoretical framework, employee empowerment practice was the independent variable, employee’s taking charge was the dependent variable, and perceived organizational support was the moderator. We expected employee empowerment would fuel up employee’s taking charge only when employees perceived that they have high organizational support. Particularly, according to trait activation theory, behaviour can be explained on the basis of people’s responses to “trait-relevant cues” which surface in situations. Trait-relevance refers to the degree to which a situation provides cues for the expression of “trait-relevant behaviour”.16 Translated to our topic, a situation can provide a greater or lesser number of cues for employees that are empowered (the trait in our case) to engage themselves in taking charge (the trait-relevant behaviour in our case). Organizational support can be viewed as trait-relevant cues in the workplace. Therefore, guided by trait activation theory, perceived organizational support (POS) offers employees trait-specific discretionary cues (eg, work autonomy) which empower employees.16–18 Particularly, according to Luoh et al,19 employees are likely to take complete responsibility to discover different ways and adapt sustainable behaviours to respond to challenges when they are empowered and given job autonomy.

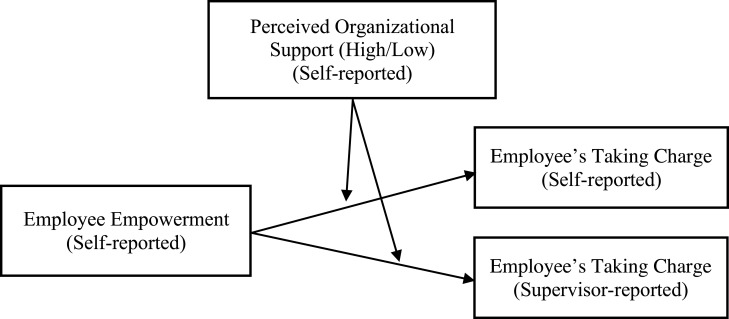

POS is a typically studied situational factor in workplaces, which signifies the extent to which workers perceive that their organization appreciates their contributions and concerns about their comfort and well-being.20 It encourages employees to apply higher-level skills and develops an intrinsic interest in the tasks.21 POS does not only lead employees to those behaviours that are required in the job description but goes beyond that and contributes to the extra-role behaviour in the organization.22 Such that, employees who perceive high organizational support make efforts aligned with the organization’s interest and demonstrate extra-role behaviour. Therefore, we included perceived organizational support and employee empowerment in our theoretical framework and observed their interaction influence on the employees’ taking charge reported by two sources. We depicted the development process of the overall conceptual framework in the following section (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

Sustainability has become an active research topic worldwide. At its core, sustainability refers to the ideas of “reproduction” and “self-sustainment” in order to ensure a system’s long-term viability or survival.23 In this sense, sustainable development can be interpreted as the ability of a society, an organization or an individual to maintain, strengthen and to develop itself (its resources, capital, etc.) from within. Meanwhile, according to Ehnert,23 sustainable HRM involves not simply attracting and retaining talented and determined employees but also providing them a person-fit work environment and opportunities to grow. However, in the research field, research on sustainability in human resources management and organizational psychology is getting adequate attention.24 One study in this domain investigated sustainable HRM’s role in encouraging employees’ sustainable behaviours.12 Others affirmed that employee empowerment is a certain form of sustainable HRM13 and taking charge is a distinctive form of behaviour that can support the organizations to attain sustainable performance.2,4,5 Although research has investigated the sustainable HRM (eg, employee empowerment) with sustainable behaviours, limited research has focused on individual-level and psychological perception inside the organization. Thus, scholars in sustainable science have called for further research to understand psychological perception and processes in sustainable development.25 In this sense, perceived organizational support is an important psychological element that might clarify the psychological process for sustaining the behaviour and performance in the organization.18,26,27 As demonstrated in Figure 1, we included the constructs mentioned above by studying the relationship between employee empowerment and employee’s taking charge behaviour and examining the moderating role of perceived organizational support.

This study aimed to offer various hypothetical contributions. Firstly, by examining the impact of employee empowerment practice on employees’ taking charge behaviour, this research made an inventive attempt to investigate the association between sustainable HR practices and change-oriented behaviours. By this attempt, we provide an inclusive understanding of how to stimulate employees to attain sustainable performance in a promptly changing and uncertain business environment. Secondly, we brought perceived organizational support as a psychological process that, based on trait activation theory, let employees perceive trait-specific discretionary cues. By doing so, we examined the interactive effect of perceived organizational support with employee empowerment on employees’ taking charge behaviours. Moreover, by examining the proposed relationships, this study answered the call for further studies by scholars to investigate the psychological processes in sustainability science.25,28

Theory and Hypotheses Development

Employee Empowerment Practice

From the resource-based perspective, a firm’s sustainable performance and its competitive gain result from the possession and authorization of valuable, non-substitutable, and rare resources.29 According to Barney and Wright,30 Wright et al,31 and Potnuru et al,32 amongst various valuable resources of an organization, effective human resources development creates a competency level and sustainable competitive gain because of its matchless role in empowering employees to accomplish desired objectives and pursue an organization’s sustainable performance.

Empowerment is a managerial tool that is intended for an organization’s benefits and can be promoted by management to derive the benefits of empowered employees. Empowerment means supporting and inspiring the workforce to make decisions with high authority inside the organization. It is termed as providing authority, autonomy, and status to employees to make crucial decisions timely for the organizations. This approach is basically comprised of practices intended at sharing information, job-related knowledge or data, and power with employees.14

Existing studies narrated significant effects of employee empowerment practice on work engagement,33 job performance,13 organizational performance,34 and employee competencies.32 Nevertheless, limited research investigated the association between employee empowerment and employee’s change-oriented behaviour, which might be important for sustaining an organization’s performance and its long-term development.2,4,25,32,34 Therefore, we investigated the impact of employee empowerment under individual-level perception about organizational support on taking charge behaviour. Our reasoning is described in the following section.

Employee Empowerment and Taking Charge Behaviour

“Employee empowerment is a relational construct that describes how those with power in organizations share power and formal authority with those lacking it”.14 Employee empowerment, according to Daft35 implicates offering employees the freedom to work, control over certain activities, and access to information to contribute in decision-making processes and organizational affairs. But, some scholars (eg, Conger and Kanungo;15 Spreitzer;36 Thomas and Velthouse37) have altered their attention to employees’ psychological traits. They stress the level of empowerment (psychological empowerment) an individual feels within him/herself ie, meaning, competence, self-determination, and impact.36 According to Conger and Kanungo,15 psychological empowerment is a form of internal drive beneficial to fostering change-oriented behaviour (eg, taking charge). Morrison38 recommended that empowerment stimulates employees, increasing their motivational drive, ambitions, and demonstration of taking charge; furthermore, for sustainable taking charge, employees must have authority and impact in the accomplishing of their occupational responsibilities. Wang and Long39 also signified that employee’s psychological empowerment positively incentivizes taking charge. A key factor of taking charge behaviour is that it is innovative and change-oriented. Moreover, it pushes individuals to be more adaptive.5 It is a crucial type of proactive behaviour that maintains organizational survival and promotes individual growth. Meanwhile, taking charge has a number of practical uses. Constructing new processes to carry out job duties, changing the approach to job performance to amplify efficiency, or making on-the-spot modifications of substandard practices or procedures are all practical uses of taking charge.2

In addition, guided by trait activation theory, when employees perceive empowerment cues, they are more likely to focus on such behaviors that communicate their authority and benefit the organization.17,36 More specifically, according to trait activation theory, behaviour can be explained on the basis of people’s responses to “trait-relevant cues” which surface in situations. Trait-relevance refers to the degree to which a situation provides cues for the expression of “trait-relevant behaviour”.16 Translated to our topic, a situation can provide a higher or lesser number of cues for employees those are empowered (the trait in our case) to engage themselves in taking charge (the trait-relevant behaviour in our case). Generally, in organizations, employees are encouraged to offer helpful and change-oriented ideas for the work and the business, which might reflect their authority and importance.40,41 As such, when employees reflect a sense of control and a proactive orientation towards their role at work, they strive for sustaining organizational performance and improvement.42 In particular, several empirical studies have confirmed that individuals who experience greater empowerment at work are strongly determined to work on their taking charge behaviour to sustain performance.7,43 Coun et al44 also posited the significantly positive bond between psychological empowerment and workplace proactivity. In other words, empowered employees are keen and motivated at work and can reinforce problem-solving skills,36,39,45 resulting in a greater level of proactive behaviour. Therefore, we assume that employee empowerment will play a key role in employee’s taking charge behaviour and formed the following hypothesis;

Hypothesis 1: Employee Empowerment has a positive relationship with Employee’s Taking Charge behaviour.

Perceived Organizational Support as an Underlying Psychological Boundary Condition

Although research has investigated the sustainable HRM (eg, employee empowerment) with sustainable behaviours, there has been a call for further studies by scholars to investigate the psychological processes in sustainability science.25,28 Because, individuals perform within the organizational context, it is therefore crucial to investigate the influence of an employees’ individual-level perception of organizational factors associated with their empowerment and taking charge behaviour. For instance, the dispositional practice of employee empowerment would be better ventilated and be further predictive of taking charge in a more supportive organizational setting. Therefore, this study, building on prior outcomes, investigates the role of perceived organizational support as underlying psychological boundary condition on the employee empowerment and employee taking charge.

According to Eisenberger et al20 and Kurtessis et al,22 perceived organizational support is an imperative contextual factor that mainly dictates how individuals inside an organization act in return to promising treatments from the authorities. A supportive environment inside organization is thought to have the competence of developing an empowered and creative workforce;20 because, perceived organizational support encourages individuals’ expectancy and perception that their organization would deliver adequate job resources when required. Therefore, perceived organizational support as a significant job resource, has been indicated to be associated to taking charge positively46 and manifests to develop other respective resources; for instance, affective commitment, positive emotional outcomes, work engagement, trust, and well-being18,26 which greatly facilitate taking charge behaviour.

In addition, guided by trait activation theory, individuals would ventilate an attribute or trait just when an appropriate contextual cue is existing which is believed to “activate” the attribute or trait.16 As explained earlier, behaviour can be explained on the basis of people’s responses to “trait-relevant cues” which surface in situations.16 In our case, organizational support can be viewed as trait-relevant cues in the workplace. More specifically, we propose that a supportive organizational environment (high POS) formed by the prevalence of managers in the organization indicates that employees’ proactive behaviors are accepted and appreciated. Thus, employee empowerment would be activated which accordingly fosters taking charge through self-regulation of a resourceful job setting.

Basically, perceived organizational support (POS) offers employees trait-specific discretionary cues (eg, work autonomy) which empower employees.16–18 Particularly, according to Luoh et al19 employees are likely to take complete responsibility to discover different ways and adapt sustainable behaviours to respond to challenges when they are empowered and given job autonomy. Perceived organizational support also promotes approval of fresh ideas conceivably by mitigating the pressure related with fear of failure and by increasing identified and intrinsic motivation to seek ways to perform well.18 Consequently, employees strive for sustaining organizational performance and improvement.42 Besides, when empowered, employees take complete responsibility to ascertain new techniques and acquire a variety of skills to face organizational challenges.19 Hence, we formed the following hypothesis;

Hypothesis 2: Perceived Organizational Support moderates the relationship between Employee Empowerment and Employee’s Taking Charge behaviour. Such that, the relationship will be stronger when Perceived Organizational Support is high.

Methodology

Sample and Procedure

In order to meet the objectives of this study, we selected a cross-sectional approach and collected the data from two sources (eg, team members and team supervisors) in manufacturing firms in China. We considered individual-level data comprised of 290 team members who self-reported perceived organizational support, employee empowerment, and taking charge behaviour. Besides, to avoid common method bias about their change-oriented behaviour, we asked their immediate supervisors to rate their individual-level taking charge behaviour. Hence, in time one, we received self-reported data from team members, in time two, once we had all responses from team members, we collected supervisor-rated responses on employee’s taking charge.

Considering the demographic information, our study received 290 responses. In this sample size, 241 were male employees (83.1%) and 49 were female employees (16.9%). The majority of the respondents held a bachelor’s degree (n = 144, 49.7%). Of the remaining respondents, 48.3% were master’s degree holders (n = 140), and the rest, 2.1% (n = 6) were diploma holders. Besides, participants age ratio is as follows; the majority of the respondents were between “26–35 years old” (n = 191, 65.9%), and the remaining “20–25 years” (n = 37, 12.8%), “36–45 years” (n = 36, 12.4%), and “46 and above” (n = 26, 9.0%). Regarding tenure in the same organization, employees with “1–3 years” were the most (n = 105, 36.2%), and then “3–5 years” (n = 66, 22.8%), “less than one year” (n = 47, 16.2%), “5–8 years” (n = 38, 13.1%), and the rest had “above 8 years” experience in the same organization (n = 34, 11.7%).

In addition, for meeting the study objectives statistically, we employed the SPSS-Process Macro by Andrew F. Hayes47–49 for hypotheses testing, and used model no. 01 for moderation effect that analyzed direct and interactional effects in one go.

Ethical Consideration

Participants were informed prior to the survey regarding the purpose of research and were given assurance for the confidentiality of data. A description was given prior to commencement of the survey. The study was conducted in line with the Helsinki Declaration principles. We used standard procedures and measurement instruments and sought approval from the academic development committee of Zhejiang Gongshang University (reference no. 202103/IRB/03, dated 2021-03-09).

Measurements

This study used established scales for a structured questionnaire survey for primary data and ensured its reliability and validity prior to further analysis. We designed a questionnaire in two portions; first section consisted of demographic information (eg, gender, age, education, experience), and second section consisted of study variables (eg, perceived organizational support, employee empowerment, and taking charge behavior) on the seven-point Likert scale; options ranged from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 7 = Strongly Agree. Besides, to match the supervisor-rated responses for each team member’s taking charge behaviour, we assigned a unique code to all participants, and amid the pandemic, we prioritized data collection electronically; for instance, we shared google form’s link to participants directly via e-mail and WhatsApp messenger.

For perceived organizational support, we adopted a measurement scale developed by Eisenberger et al,20 and modified items according to the present study. The reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) for perceived organizational support in the current study is (0.776). For measuring the effectiveness of employee empowerment, we used Men and Stacks50 and Menon51 scales, and modified construct’s items accordingly. The Cronbach’s alpha for employee empowerment for this study is (0.832). Lastly, for taking charge behaviour, we adopted the Morrison and Phelps2 scale and modified it according to self-reported response and supervisor-rated response. The reliability for self-reported taking charge behaviour is (0.801), and for supervisor-rated taking charge behaviour is (0.794).

Results

Data Analysis

In the current study, we analyzed data in two phases. In the first phase, we performed basic analysis to identify the reliability of items, convergent validity, discriminant validity, and checked model fitness. In the second phase, after receiving the significant results, we evaluated hypotheses using model no. 01 for moderation effect.

Construct Reliability and Validity

In the current study, we tested the consistency in responses to the questionnaire survey by calculating the items’ reliability. Thus, the present study staged reliability analysis of 4 constructs (including supervisor-rated taking charge) by using Cronbach’s alpha (α), and Cronbach’s value for all constructs is α > 0.7.

We retrieved the convergent validity as well. According to Hair Jr. et al,52 to validate satisfactory convergent validity, the considerable standardized average variance extracted (AVE) is supposed to be greater than 0.5 and reliability should be greater than 0.7. Hence, followed by the results, all variables’ values in the current study meet the threshold values, which demonstrate the internal consistency at a satisfactory level. Table 1 exhibits the results of reliability and validity, which are acceptable for further analysis.

Table 1.

Construct Reliability and Validity

| Main Variables | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employee Empowerment | 0.832 | 0.816 | 0.773 |

| Taking Charge (Self-reported) | 0.801 | 0.845 | 0.645 |

| Taking Charge (Supervisor-rated) | 0.794 | 0.769 | 0.581 |

| Perceived Organizational Support | 0.776 | 0.842 | 0.695 |

Model Fitness Statistics

In order to proceed with further analysis, we checked the model fitness by using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on the 3 constructs of employee empowerment, taking charge, and perceived organizational support. We performed CFA on self-reported and supervisor-rated taking charge behaviour separately. The fit of both three-factor models was verified. Table 2 demonstrates that both hypothesized three-factor models confirmed suitable fit. For the default model involving self-reported constructs, results are as follows; (X2(50) = 62.027, p < 0.005; RMSEA = 0.042, CFI = 0.976). For the default model containing two self-reported (eg, employee empowerment and perceived organizational support) and one supervisor-reported construct (eg, taking charge behaviour), results are as follows; (X2(40) = 47.587, p < 0.005; RMSEA = 0.037, CFI = 0.982). Both models have a slight difference in result, but both confirmed the authenticity of employee’s change-oriented behaviour reported by two different sources. In addition, factor loadings of all items were substantial, supporting convergent validity in the present study.

Table 2.

Model Fitness Statistics

| Model | X2 | Df | X2/Df | SRMR | RMSEA | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Default Model (Self-Reported) | 62.027 | 50 | 1.241 | 0.656 | 0.042 | 0.976 |

| Default Model (Supervisor-Rated TCB) | 47.587 | 40 | 1.19 | 0.615 | 0.037 | 0.982 |

Abbreviations: TLI, Tucker-Lewis index; CFI, Comparative fit index; RMSEA, Root mean square error of approximation’ SRMR, Standardised Root Mean Residual; TCB, Taking Charge Behaviour.

Hypotheses Testing (Direct and Indirect Channel)

Table 3 demonstrates the statistical results for proposed hypotheses (H1 and H2). The outcomes indicated employee empowerment’s positive association with self-reported taking charge (β = 1.305, t = −7.815, p = <0.01) and supervisor-reported taking charge behaviour (β = 1.190, t = −8.079, p = <0.01). This supported hypothesis 1 and confirmed that employee empowerment has a positive relationship with employee’s taking charge behaviour.

Table 3.

Regression Results

| Predictor | |||||||

| Model Summary (Self-rated TCB) | R | R-sq | MSE | f | |||

| 0.512 | 0.263 | 0.892 | 33.944 | ||||

| B | SE | t | p | ||||

| Taking Charge Behaviour (Self-Reported) | |||||||

| Constant | −1.746 | 0.972 | −1.797 | 0.073 | |||

| Employee Empowerment | 1.305 | 0.167 | 7.815 | 0.000 | |||

| Perceived Organizational Support | 0.887 | 0.217 | 4.098 | 0.001 | |||

| Taking charge x Perceived Organizational Support | −0.177 | 0.036 | −4.963 | 0.000 | |||

| Test(s) of highest order unconditional interaction(s) | R2-chng | f | |||||

| 0.603 | 24.631 | ||||||

| Model Summary (Supervisor-rated TCB) | R | R-sq | MSE | f | |||

| 0.556 | 0.309 | 0.694 | 42.510 | ||||

| B | SE | t | p | ||||

| Taking Charge Behaviour (Supervisor-Reported) | |||||||

| Constant | −1.186 | 0.857 | −1.383 | 0.168 | |||

| Employee Empowerment | 1.190 | 0.147 | 8.079 | 0.000 | |||

| Perceived Organizational Support | 0.766 | 0.191 | 4.008 | 0.000 | |||

| Taking charge x Perceived Organizational Support | −0.149 | 0.314 | −4.726 | 0.000 | |||

| Test(s) of highest order unconditional interaction(s) | R2-chng | f | |||||

| 0.054 | 22.335 | ||||||

| Moderator | Levels | Boot Indirect Effect | Boot SE | Boot t | Boot p | LLCI | ULCI |

| Perceived Organizational Support (Self-Reported TCB) | Low | 0.606 | 0.063 | 9.879 | 0.000 | 0.483 | 0.729 |

| Mean | 0.405 | 0.066 | 6.136 | 0.000 | 0.275 | 0.536 | |

| High | 0.205 | 0.090 | 2.278 | 0.023 | 0.028 | 0.382 | |

| Perceived Organizational Support (Supervisor-rated TCB) | Low | 0.603 | 0.055 | 10.917 | 0.000 | 0.495 | 0.712 |

| Mean | 0.435 | 0.058 | 7.456 | 0.000 | 0.320 | 0.550 | |

| High | 0.266 | 0.079 | 3.354 | 0.000 | 0.120 | 0.422 | |

Notes: Sample size: 290 individuals; number of bootstraps resample = 5000.

Abbreviations: TCB, taking charge behaviour; EE, employee empowerment; POS, perceived organizational support.

In line with our hypothesis 2, which assumed that perceived organizational support moderates the relationship between employee empowerment and employee’s taking charge behaviour. The results indicate that the interaction term between employee empowerment and perceived organizational support on self-reported taking charge (β = −0.177, t = −4.963. p = <0.01) and on supervisor-reported taking charge (β = −0.149, t = −4.724. p = <0.01) were negatively significant. This confirmed that the interactional effect between employee empowerment and perceived organizational support significantly influence the employee’s taking charge behaviour.

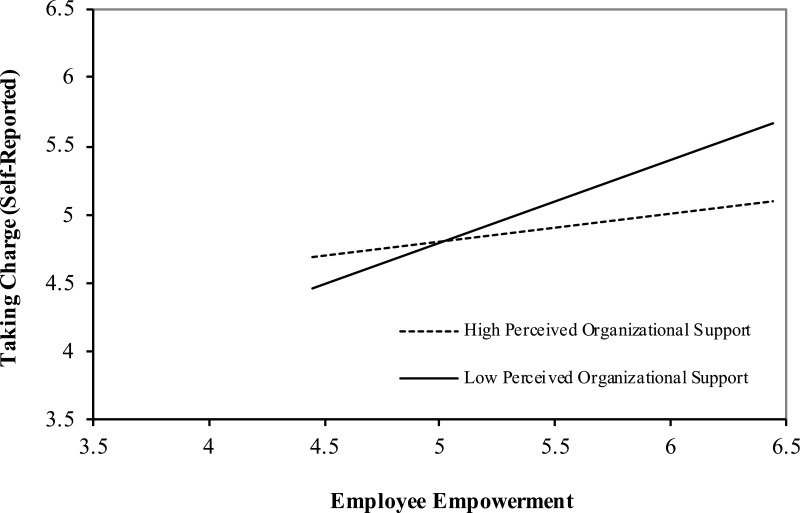

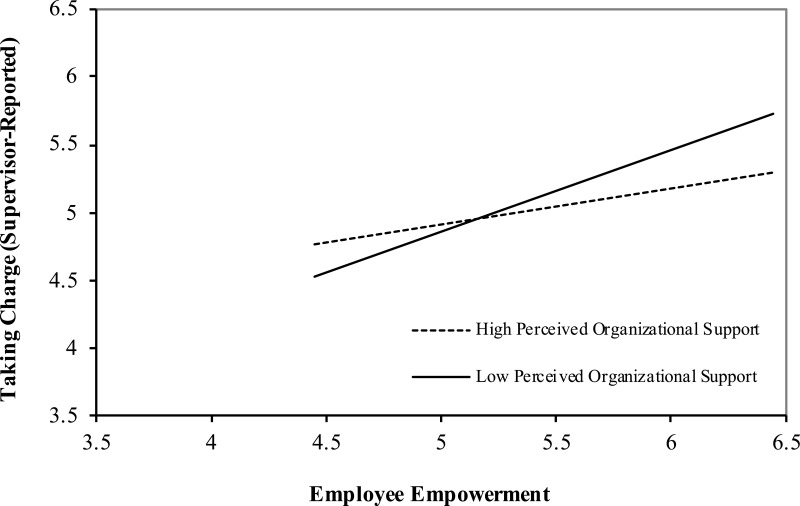

To entirely support hypothesis 2, we applied conventional practices for plotting simple slopes (Figures 2 and 3) at one standard deviation above and below the mean of the perceived organizational support measure. The positive association between employee empowerment and employee’s taking charge will improve under the condition of low perceived organizational support. This result is not consistent with hypothesis 2

perceived organizational support moderates the relationship between employee empowerment and employee’s taking charge behaviour. Such that, the relationship will be stronger when perceived organizational support is high.

Figure 2.

The moderating effect of perceived organizational support on the relationship between employee empowerment and taking charge (Self-reported).

Figure 3.

The moderating effect of perceived organizational support on the relationship between employee empowerment and taking charge (Supervisor-reported).

Thus, overall hypothesis 1 was supported and hypothesis 2 was rejected.

Results Discussion, Implications, and Limitations

Discussions

The present study has found that employee empowerment and perceived organizational support have a positive and significant influence on employee’s taking charge behaviour. Moreover, the results confirm that the perceived organizational support’s moderating effect is significant on the above relationships. Detailed results are further discussed below.

Employee empowerment has demonstrated a positively significant link with employee’s taking charge behaviour. In this regards, the outcome of this study is aligned with the studies of Kim et al.,7 Li et al43 and Coun et al44 that established that empowered employees will enhance proactivity at workplace and will engage taking charge behaviour. The study also identified the positive association between perceived organizational support and employee’s taking charge behaviour which confirms the hypothesis of distinguished scholars, for instance, Burnett, Chiaburu, Shapiro, and Li.46

Moreover, the perception of organizational support moderated the link between employee empowerment with employee’s taking charge behaviour. Followed by Lambert’s53 findings, employees become inept at higher levels of perceived organizational support. Specifically, our study confirmed the strong effect of POS on employee’s taking charge behaviour at low level and then moderate level; therefore, our finding empirically validates the theoretically assumed relation by Burnett et al46 and Wang et al.54 This empirical result endorses that employee empowerment accelerated by the perceptions of low organizational support might demonstrate a positive impact on the development of employee’s taking charge behaviour. In other words, our hypothesis one received statistical support and hypothesis two did not meet the expectations statistically.

Theoretical Implications

The present study has several theoretical implications for its findings. This study offers an in-depth understanding of how employee empowerment fosters change-oriented behaviour, namely taking charge in the presence of situational factor perceived organizational support. The findings verify that the link between employee empowerment and employee’s taking charge can be reinforced by low perceived organizational support. By observing perceived organizational support as a moderator, this research contributed to the literature of organizational support by delivering a comprehensive understanding of prospective advantages of perceived organizational support at certain levels. Previous research has broadly acknowledged that perceived organizational support, as a valued occupational resource, stimulates a range of employee outcomes ie, affective commitment, trust, and work engagement.18,21,26

The present study basically enhanced this stream of research and contributed to the literature of organizational support by demonstrating one more way via which perceived organizational support influences employee outcomes – by holding the moderating position. More precisely, the research outcomes of this study recommend that it’s not high, but sometimes, low perceived organizational support that performs as a resilient situational factor or contextual moderator that is capable of activating and encouraging employee empowerment on their taking charge behaviour. Such that, extreme support from organizations might “overburden” employees (cf. Burnett et al.,;46 Ilies et al.,;55 Kossek et al.,;56 Perlow,57). Hence, high perceived organizational support is not always helpful. Although, high perceived organizational support in itself enables well-being, affective commitment, work engagement, trust, and it also protects from the negative consequence ie, workplace conflicts.58 Yet, supra-optimal levels of “care” by the organization might be perceived as over controlling, overpowering, or otherwise too much (cf. Burnett et al.,46 Ilies et al.,55 Kossek et al.,56 Perlow57) which might result in unwanted consequences.

In addition, this study contributes to the trait activation theory by demonstrating organizational support as trait-relevant cues in the workplace, which provides number of cues for empowered employees (the trait in our case) to engage themselves in change-oriented behaviour (eg, taking charge – the trait-relevant behaviour in our case). Other than this, by examining the proposed relationships, this study answered the call for further studies by scholars to investigate the psychological processes in sustainability science.25,28 More specifically, the study findings brought forward the certain level of perception of organizational support as psychological process that sustains the change-oriented behaviour among empowered employees and directs them to sustainable performance.

Practical Implications

There are several practical implications for this study. Primarily, there is evidently a threshold of perceived organizational support beyond which there is probably to be detrimental outcomes. Such that, extreme support from organizations might “overburden” employees, because supra-optimal levels of “care” by organization might be perceived as over controlling, irresistible, or otherwise too much (cf. Burnett et al.,46 Ilies et al.,55 Kossek et al.,56 Perlow57). Certainly, receivers’ reactions to organizational support are not constantly positive; sometimes, they might feel vulnerable or incapable,59,60 and sometimes “overhelped”.61 Our study outcomes extend these streams of work by concentrating on support from organization and authenticating an exclusive outline associating employee empowerment with perceived organization support on employee’s taking charge behaviour, namely organizations might, rather counterintuitively, attain greater levels of empowered employee’s taking charge behaviour by delivering less is more-oriented organizational support programs. This interpretation could be welcoming for sustainable performance during times, for instance today, of a stagnating resource-constrained economy.

Further, managers may consider other sustainable HR practices ie training on self-actualization,6 counselling on self-performance expectations,62 investing in human capital,63 and providing satisfactory psychological climate64 to activate the employee empowerment that later can foster employees to engage in positive organizational behaviours. Pay is also termed as suitable HR practice that promotes taking charge behaviour.65 Consequently, managers can also revise the compensation plans for encouraging employees to sustain change-oriented behaviour.

Limitations and Future Directions

The present study has some boundaries; but these boundaries pave the way for a new pathway for future work. Although, we received responses from two different sources (eg, team members and team supervisors), but self-reporting of employee empowerment and perceived organizational support may raise issues regarding biased responses. Therefore, it is strongly recommended that future scholars consider two sources for such variables to avoid common method bias. Besides, they should conduct longitudinal research that lessens the direction of causality, caused by time-lagged cross-sectional study. In addition, future studies may consider other contextual and individual factors ie, organizational learning culture,32 emotional intelligence,66 leader-member exchange7, and regulatory focus67 to influence our model.

Data Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Disclosure

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kaplan RS, Norton DP. Transforming the balanced scorecard from performance measurement to strategic management: part I. Account Horizons. 2001. doi: 10.2308/acch.2001.15.1.87 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrison EW, Phelps CC. Taking charge at work: extrarole efforts to initiate workplace change. Acad Manag J. 1999;42(4):403–419. doi: 10.2307/257011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Detert JR, Burris ER. Leadership behavior and employee voice: is the door really open? Acad Manag J. 2007;50(4):869–884. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baik SJ, Song HD, Hong AJ. Craft your job and get engaged: sustainable change-oriented behavior at work. Sustain. 2018. doi: 10.3390/su10124404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant AM, Ashford SJ. The dynamics of proactivity at work. Res Organ Behav. 2008;28:3–34. doi: 10.1016/j.riob.2008.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar N, Zhiqiang L, Hossain MY. Examining the relationship between self-actualization and job performance via taking charge. Int J Res Bus Soc Sci. 2020;9:43–49. doi: 10.20525/ijrbs.v9i5.858 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim T-Y, Liu Z, Diefendorff JM. Leader–member exchange and job performance: the effects of taking charge and organizational tenure. J Organ Behav. 2015;36(2):216–231. doi: 10.1002/job.1971 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li SL, Sun F, Li M. Sustainable human resource management nurtures change-oriented employees: relationship between high-commitment work systems and employees’ taking charge behaviors. Sustain. 2019;11(13):45. doi: 10.3390/su11133550 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai Z, Huo Y, Lan J, Chen Z, Lam W. When Do Frontline Hospitality Employees Take Charge? Prosocial Motivation, Taking Charge, and Job Performance: the Moderating Role of Job Autonomy. Cornell Hosp Q. 2019;60(3):237–248. doi: 10.1177/1938965518797081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huselid MA. The Impact Of Human Resource Management Practices On Turnover, Productivity, And Corporate Financial Performance. Acad Manag J. 1995. doi: 10.5465/256741 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noe RA, Hollenbeck JR, Gerhart B, Wright PM. Human Resource Management: Gaining a Competitive Advantage. McGraw-Hill Education New York, NY; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen E, Taylor S, Muller-Camen M. HRM’s Role in Corporate Social and Environmental Sustainability; SHRM Foundation. Alexandria. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manzoor F, Wei L, Bányai T, Nurunnabi M, Subhan QA. An examination of sustainable HRM practices on job performance: an application of training as a moderator. Sustain. 2019;11(8):1–19. doi: 10.3390/su11082263 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez S, Moldogaziev T. Employee Empowerment, Employee Attitudes, and Performance: testing a Causal Model. Public Adm Rev. 2013;73(3):490–506. doi: 10.1111/puar.12049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conger JA, Kanungo RN. The empowerment process: integrating theory and practice. Acad Manag Rev. 1988;13(3):471–482. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tett RP, Burnett DD. A personality trait-based interactionist model of job performance. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(3):500–517. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tett RP, Toich MJ, Ozkum SB. Trait Activation Theory: a Review of the Literature and Applications to Five Lines of Personality Dynamics Research. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2021;8:199–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-062228 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenberger R, Rhoades Shanock L, Wen X. Perceived Organizational Support: why Caring about Employees Counts. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2020;7:101–124. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012119-044917 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luoh H-F, Tsaur S-H, Tang -Y-Y. Empowering employees: job standardization and innovative behavior. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2014;26(7):1100–1117. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-03-2013-0153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisenberger R, Huntington R, Hutchison S, Sowa D. Perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol. 1986;71(3):500–507. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenberger R, Stinglhamber F. Perceived Organizational Support: Fostering Enthusiastic and Productive Employees. American Psychological Association; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurtessis JN, Eisenberger R, Ford MT, Buffardi LC, Stewart KA, Adis CS. Perceived Organizational Support: a Meta-Analytic Evaluation of Organizational Support Theory. J Manage. 2017;43(6):1854–1884. doi: 10.1177/0149206315575554 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ehnert I. Sustainable human resource management: a conceptual and exploratory analysis from a paradox perspective. Contributions Management Sci. 2009. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7908-2188-8_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ehnert I, Harry W, Zink KJ. Sustainability and HRM; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg. 2014. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-37524-8_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Fabio A, Rosen MA. Opening the Black Box of Psychological Processes in the Science of Sustainable Development: a New Frontier. Eur J Sustain Dev Res. 2018;2(4):2–6. doi: 10.20897/ejosdr/3933 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ficapal-Cusí P, Enache-Zegheru M, Torrent-Sellens J. Linking perceived organizational support, affective commitment, and knowledge sharing with prosocial organizational behavior of altruism and civic virtue. Sustain. 2020;12(24):1–20. doi: 10.3390/su122410289 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aselage J, Eisenberger R. Perceived organizational support and psychological contracts: a theoretical integration. J Organ Behav. 2003;24(SPEC.ISS):491–509. doi: 10.1002/job.211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Fabio A. The Psychology of Sustainability and Sustainable Development for Well-Being in Organizations. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barney J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J Manage. 1991;17(1):99–120. doi: 10.1177/014920639101700108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barney JB, Wright PM. On becoming a strategic partner: the role of human resources in gaining competitive advantage. Hum Resour Manage. 1998;37(1):31–46. doi::: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wright PM, Dunford BB, Snell SA. Human resources and the resource based view of the firm. J Manage. 2001;27(6):701–721. doi: 10.1177/014920630102700607 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potnuru RKG, Sahoo CK, Sharma R. Team building, employee empowerment and employee competencies: moderating role of organizational learning culture. Eur J Train Dev. 2019;43(1–2):39–60. doi: 10.1108/EJTD-08-2018-0086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L, Zhang Y, Dallas M, Xu S, Hu J. How perceived empowerment HR practices influence work engagement in social enterprises–a moderated mediation model. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2018;29(20):2971–2999. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2018.1479874 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin Y, Wang Y, Lu Y. Antecedents and outcomes of employee empowerment practices: a theoretical extension with empirical evidence. Hum Resour Manag J. 2019;29(4):564–584. doi: 10.1111/1748-8583.12243 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Daft RL. Essentials of Organization Theory & Design. South Western Educational Publishing; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spreitzer GM. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad Manag J. 1995;38(5):1442–1465. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas KW, Velthouse BA. Cognitive elements of empowerment: an “interpretive” model of intrinsic task motivation. Acad Manag Rev. 1990;15(4):666–681. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morrison EW. Organizational citizenship behavior as a critical link between HRM practices and service quality. Hum Resour Manage. 1996;35(4):493–512. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang L, Long L. Idiosyncratic deals and taking charge: the roles of psychological empowerment and organizational tenure. Soc Behav Pers. 2018;46(9):1437–1448. doi: 10.2224/sbp.7084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen CC, Zhang AY, Wang H. Enhancing the Effects of Power Sharing on Psychological Empowerment: the Roles of Management Control and Power Distance Orientation. Manag Organ Rev. 2014;10(1):135–156. doi: 10.1111/more.12032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dust SB, Resick CJ, Mawritz MB. Transformational leadership, psychological empowerment, and the moderating role of mechanistic–organic contexts. J Organ Behav. 2014;35(3):413–433. doi: 10.1002/job.1904 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hornung S, Rousseau DM, Weigl M, Müller A, Glaser J. Redesigning work through idiosyncratic deals. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2014;23(4):608–626. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2012.740171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li S-L, He W, Yam KC, Long L-R. When and why empowering leadership increases followers’ taking charge: a multilevel examination in China. Asia Pacific J Manag. 2015;32(3):645–670. doi: 10.1007/s10490-015-9424-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coun M, Peters P. ‘To empower or not to empower, that’s the question’. Using an empowerment process approach to explain employees’ workplace proactivity. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2021;2:1–27. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2021.1879204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li X. The Preliminary Literature Review of Proactive Behavior. Am J Ind Bus Manag. 2020;10(05):915–919. doi: 10.4236/ajibm.2020.105061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burnett MF, Chiaburu DS, Shapiro DL, Revisiting How LN. When Perceived Organizational Support Enhances Taking Charge: an Inverted U-Shaped Perspective. J Manage. 2015;41(7):1805–1826. doi: 10.1177/0149206313493324 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instruments Comput. 2004;36(4):717–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behav Res. 2007;42(1):185–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Men LR, Stacks DW. The impact of leadership style and employee empowerment on perceived organizational reputation. J Commun Manag. 2013;17(2):171–192. doi: 10.1108/13632541311318765 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Menon S. Employee Empowerment: an Integrative Psychological Approach. Appl Psychol. 2001;50(1):153–180. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hair JF, Matthews LM, Matthews RL, Sarstedt M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: updated guidelines on which method to use. Int J Multivar Data Anal. 2017;1(2):107–123. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lambert SJ. Added benefits: the link between work-life benefits and organizational citizenship behavior. Acad Manag J. 2000;43(5):801–815. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Z, Zhang J, Thomas CL, Yu J, Spitzmueller C. Explaining benefits of employee proactive personality: the role of engagement, team proactivity composition and perceived organizational support. J Vocat Behav. 2017;101(April):90–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ilies R, Wilson KS, Wagner DT. The spillover of daily job satisfaction onto employees’ family lives: the facilitating role of work-family integration. Acad Manag J. 2009;52(1):87–102. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kossek EE, Pichler S, Bodner T, Hammer LB. Workplace social support and work–family conflict: a meta‐analysis clarifying the influence of general and work–family‐specific supervisor and organizational support. Pers Psychol. 2011;64(2):289–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perlow LA. Boundary control: the social ordering of work and family time in a high-tech corporation. Adm Sci Q. 1998;1:328–357. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caesens G, Stinglhamber F, Demoulin S, De Wilde M, Mierop A. Perceived organizational support and workplace conflict: the mediating role of failure-related trust. Front Psychol. 2019;9(JAN):1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fisher JD, Nadler A, Whitcher-Alagna S. Recipient reactions to aid. Psychol Bull. 1982;91(1):27. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee F. The social costs of seeking help. J Appl Behav Sci. 2002;38(1):17–35. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gilbert DT, Silvera DH. Overhelping. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70(4):678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hossain MDY, Liu Z, Kumar N. How does self-performance expectation foster breakthrough creativity in the employee’s cognitive level? An application of self-fulfilling prophecy. Int J Res Bus Soc Sci. 2020;9:5SE. doi: 10.20525/ijrbs.v9i5.818 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baeshen Y, Soomro YA, Bhutto MY. Determinants of Green Innovation to Achieve Sustainable Business Performance: evidence From SMEs. Front Psychol. 2021;12:5052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Irangani BKS, Zhiqiang L, Kumar N, Khanal S. Effect of competitive psychological climate on unethical pro-team behavior: the role of perceived insider status and transformational leadership. Management. 2021;25(1):1–27. doi: 10.2478/manment-2019-0057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.El BS, Fleisher C, Khapova SN, et al. Ambition at work and career satisfaction The mediating role of taking charge behavior. J Med. 2017. doi: 10.1108/CDI-07-2016-0124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miao C, Humphrey RH, Qian S. A meta-analysis of emotional intelligence and work attitudes. Int J Res Sci. 2017;177–202. doi: 10.1111/joop.12167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kumar N, Hossain MY, Jin Y, Safeer AA, Chen T. Impact of Performance Lower Than Expectations on Work Behaviors: The Moderating Effect of Status Mutability and Mediating Role of Regulatory Focus. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;Volume 14(December):2257-2270. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S342562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]