Abstract

Art making has been adopted across multiple disciplines as a health intervention. However, our understanding of art making as a health intervention and how it differs from art therapy is still limited. Therefore, we conducted a concept analysis to better understand art making as a health intervention guided by Walker and Avant approach. We examined Eighty-five studies in which we found four defining attributes, four antecedents, and physical, cognitive, emotional, and psychological consequences. We suggest several nursing research and practical implications for nurse researchers and clinicians to aid in designing and implementing art making health interventions.

Keywords: Concept Analysis, Art Making, Art Therapy, Health Intervention, Nursing Research, Nursing Practice

Introduction

From the beginning of human history, art has been considered a vital instrument of communication, self-expression, and symbolism.1 Since the 1940s, it has gained a reputation as a therapeutic instrument.1 Hospitals began to use it for therapeutic applications in the 1960s, displaying art to create aesthetically pleasing and calming surroundings. This is in line with Florence Nightingale’s assertion that the environment has a significant influence on healing.2 In the 1970s, clinicians began to apply art as a health intervention for patients in clinical settings.3

Art has been adopted as a health intervention across multiple disciplines including medicine, nursing, psychology, and occupational therapy.4–7 Moreover, empirical evidence has accumulated demonstrating its health benefits on various health outcomes including depression, anxiety, cognitive impairment, and pain.4–7 This type of intervention is designed and implemented using various art making activities ranging from visual arts, performing arts, and media arts to creative writing. Specifically, as a health intervention, art is offered as either an art making activity itself or an art activity within psychotherapy.

Art therapy uses visual arts (e.g., painting, drawing) as a nonverbal communication technique during a psychotherapy session8 to improve well-being in individuals with mental health problems. Its use, in practice has also extended to manage various symptoms of cancers and behaviors related to dementia.9–13 Importantly, because art therapy is considered a form of psychotherapy, its practitioners should have a Master’s degree in visual arts and psychology and obtain national board certification.7,8 In early 2010, art therapy received national accreditation from the National Commission for Certifying Agencies (NCCA). This initiative provided a clear definition for art therapy: “an integrative mental health and human services profession that enriches the lives of individuals, families, and communities through active art-making, creative process, applied psychological theory, and human experience within a psychotherapeutic relationship.”8 While this definition sets a clear boundary for art therapy as a health intervention, there is still a lack of understanding about art making as a health intervention. It is unclear for nurse researchers and practitioners how art making interventions differ from art therapy. This fact was the impetus for us to conduct this concept analysis of art making as a health intervention.

Therefore, the specific aims of this analysis include (1) to understand the current uses of art making as a health intervention, (2) to identify the distinctive components of art making - defining attributes, antecedents, consequences, and (3) to provide practical implications for nurse researchers and practitioners who are using or plan to use art making as a health intervention. The concept analysis is a valuable tool for clarifying the concept of art making and examining its internal constructs.18 Using this method, the concept of art making will be isolated from other similar concepts (e.g., art therapy), clarifying the concept under consideration. As a result, we will better understand the concept of art making as a health intervention. This will ultimately help both nurse researchers and practitioners to design and implement art making interventions to improve health.

Methods

Walker and Avant’s eight-step approach was used in this concept analysis. This approach clarified the structure of the concept of art making, enabling us to operationalize it. The eight steps include (1) concept selection, (2) description of aims or purpose of analysis, (3) description of concept use, (4) identification of defining attributes, (5) construction of a model, borderline, and contrary cases, (6) identification of related concepts, (7) identification of antecedents and consequences, and (8) description of empirical referents.18

We used five databases to search for articles published from January 2010 to August 2020. These included Academic Search Premier, Alternative Health Watch, Art Full Text (H. W. Wilson), CINAHL Plus with Full Text, and Medline. We used the following search terms: “art making”, “art based approach”, “art based intervention”, “creative art therapy” and “art therapy.” We included “art therapy” as a search term because art making is a component of art therapy.

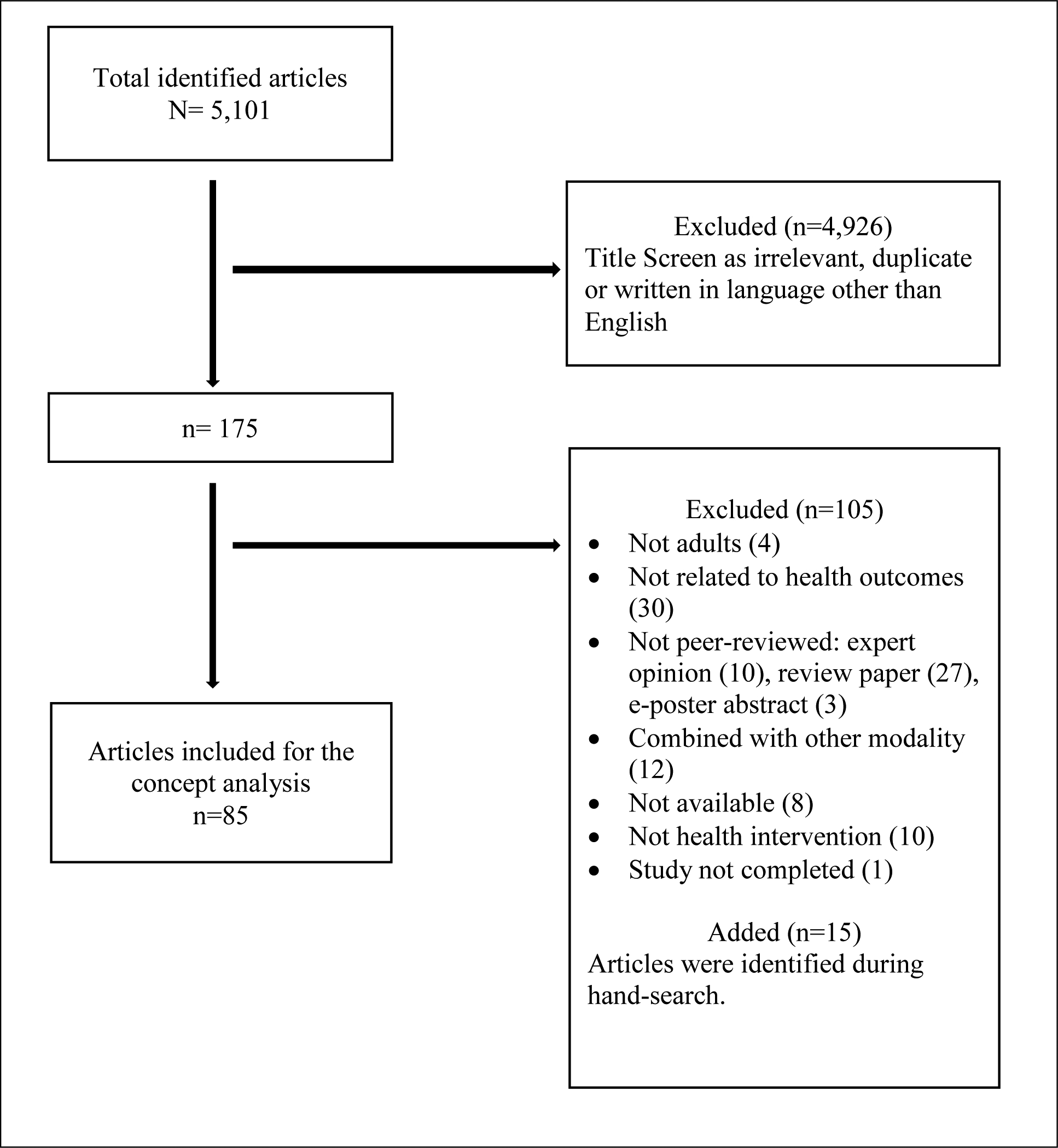

The inclusion criteria for studies this concept analysis were (1) focused on adults, defined as 18 years or older, (2) used art making as a health intervention, (3) conducted either in healthcare or community settings, (4) focused on health outcomes, (5) peer-reviewed, (6) written in English, and (7) published between January 2010 and August 2020. We excluded studies if they focused on art appreciation interventions (i.e., viewing artwork) or combined art making with another modality (e.g., mindfulness intervention). We initially identified 5,101 articles. After we screened the titles of each article for relevance, duplication, and languages other than English, we removed 4,926 articles. Among the remaining articles (n=175), we removed 94 articles after we read the abstracts because they did not meet inclusion criteria. At the same time, we added 15 articles, which were identified when we assessed systematic reviews of art making interventions found in our original searches (n=96). Lastly, we read the full text of the 96 articles and excluded 11 articles among them because they were (1) about art making in general and was not used as a health intervention (n=7) or (2) the study was not completed (n=1). Therefore, a total of 85 articles were included in this concept analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Literature Review Flow

Results

Study Characteristics

The majority of the studies were conducted in the U.S. (n=26) followed by the U.K (n=10), Canada (n=7), Australia (n=5), Germany (n=5), South Korea (n=4), France (n=4), Brazil/Hong Kong/ Italy/the Netherlands/Singapore/Taiwan (n=2, each) and others (i.e., China, Croatia, Denmark, Ireland, Israel, Malaysia, Norway, the Philippines, Russia, Serbia, Sweden, and Turkey; n=1 each). Multiple studies focused on older adult populations (n=23). None of the studies provided information on the racial/ethnic minority population of studies.

The top four disciplines that used art making as a health intervention were art therapy (n=24), medicine (n=22), nursing (n=13), and psychology (n=10). Other represented disciplines include occupational therapy (n=7), art education (n=2), social work (n=2), applied science (n=2), social science (i.e., sociology, economics; n=1 each), and not specified (n=1).

Study Design

The majority of the studies were quantitative (n=43), followed by qualitative studies (n=34), and mixed-method studies (n=8). Across the 85 studies, researchers used a variety of terms to describe art making health interventions. These terms included art making, art-based programs, art intervention, creative activity, and expressive arts.

Uses of Art Making as a Health Intervention

We observed that art making as a health intervention involved using art making activities either independently or as a component of a health intervention within psychotherapy (i.e., art therapy). Visual arts were the most commonly used a type of art making activity (n=78). These include painting, drawing, craft, tile painting, sculpture, clay, patchwork, collage, mandala, and doll making. One study offered performing arts (e.g., puppetry, dance, singing; n=1). Five studies used a combination of more than two types of art making activities such as visual and media arts (e.g., photography, n=1), visual and performing arts (n=1), visual, media and performing arts (n=1), visual and performing arts and creative writing (e.g., poetry; n=1), visual, performing and media arts and creative writing (n=1). One intervention did not specify the types of art making use.

Additionally, art making as a health intervention was used to address the following health concerns: mental health problems (e.g., anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, stress, traumatic brain injury, and PTSD; n=28), cancers (n=22), cognitive disease (e.g., dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and cognitive impairment; n=15), neurological disease (e.g., stroke, Parkinson’s disease; n=5) and others (e.g., chronic illness, chronic pain, multiple sclerosis, obesity, acquired brain injury; n=7). Eight studies used art making as a health intervention for healthy older adults to improve their physical and psychological well-being and cognitive performance. The format for delivery of the art making interventions was either individually (n=42) or within a group setting (n=43).

Defining Attributes

Defining attributes are the essential characteristics of a concept, indispensable to differentiating one concept from another.18 We identified four defining attributes of art making as a health intervention. They included (1) creation of art, (2) creativity, (3) self-expression, and (4) distraction.

Creation of Art.

All eighty-five studies demonstrated that the ‘creation of art’ is an attribute of art making. In these studies, the creation of art refers to making an artwork, which involves a participant creating an ‘object’ (e.g., painting, drawing, doll making, etc.) physically or verbally. In some cases, participants’ ideas and thoughts are also considered to be the creation of art because they are a source of the creation.19–20 Creation of art can be completed by the participant alone or with an assistant, who follows the verbalized ideas or thoughts of participants who have physical limitations.19, 21–23

Creativity.

Fifty-four studies highlighted creativity as an attribute of art making. Creativity refers to one’s uniqueness and imagination as demonstrated through one’s own art work.14–16 Participants create their own art work with minimal guidance, infusing their uniqueness (e.g., life story, personal characteristics, preferences, knowledge, artistic skills, etc.) into their art work. Throughout the art making activity, the participants decide what to create and how they prefer to use the materials given to them.23,27–28 As a result, their final artwork will differ from those of other participants. For example, in a study of women with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression, each study participant had the opportunity to create a doll.17 Participants were given various art materials to create their own dolls with their choice of art materials. This facilitated participants’ creativity because each individual selected their own art materials, demonstrating their uniqueness. Each participant was able to infuse their uniqueness into a doll, telling their story. Similarly, in a study of persons with stroke and residual physical limitations, the investigator offered various art making activities in an art making intervention (e.g., drawing, painting, collage, or handcraft).23 Each participant was able to create their own artwork with their choice of art making activity and materials. Because each participant required a different skill level due to their physical limitations, considering such limitations was a critical factor to show their creativity when selecting the art making activity. Given an intervention with multiple options to suit their varied levels of skill and ability, participants were nonetheless able to show themselves and their own unique experience through their art works.

On the contrary, non-creativity in an art making intervention is when the investigators provide detailed instruction on the art making activity, limiting participants’ ability to express themselves in a unique and personal way. For example, in an art making intervention for women with various cancers (e.g., breast, lung, gynecological), they created a ‘self-book’ containing various art making activities.11 Each step of the ‘self-book’ was guided by very specific and detailed instructions given by the investigator. Thus, there was no room for the participants to freely convey their individual uniqueness.

Self-expression.

Sixty-five studies described self-expression as an attribute of art making. Self-expression refers to one’s ability to express their emotions, thoughts, or experiences through color, artistic figures (e.g., line, shape, symbol or letter) and other forms (e.g., body movement, sounds, rhythm, lyrics).28,30–31 For some individuals under certain conditions or situations, self-expression using colors, artistic figures and/or other forms in art making can assist them in expressing their “inner pictures” (e.g., personal story, experience or emotions).19,32–35 Moreover, art making is a non-verbal communication and, in some cases, it can better convey the meanings or experiences of the participants than verbal communication.21

Distraction.

Ten studies mentioned distraction as an attribute of art making. Distraction refers to the involvement of art in assisting an individual in keeping their mind off their situations or health concerns by focusing on the present moment of art making.25,27 Distraction is described as “completely engrossed in and absorbed”,18 “distracting them from treatment”,27 and “a conscious distraction from the discomforts of everyday life”.19 Participants described the art making as follows: “providing distraction… in dealing with frustration and failure”,20 “It seems as though when I am painting, it can take my mind off the asthma”,15 “…to pass the time and provide a distraction”,6 “completely engrossed in and absorbed by artwork”,18 “at least I’m not like constantly thinking about what’s going through my veins”,20 “distraction from everyday life”,21 “lose track of time”,22 or “keeping one’s mind on things”.7

Model, Borderline, and Contrary Cases

Model Case.

A model case of art making as a health intervention should include all defining attributes: creation of art, creativity, self-expression, and distraction. We identified a model case from the study by Mische Lawson et al. because art making intervention in this study included all defining attributes, identified in this concept analysis (2012). In their study, tile painting was used as an art making intervention for patients with various cancer diagnoses. In their art making intervention, 20 participants painted tiles with their choice of artistic design and art materials (e.g., color and brush) to create their own style of tile (creation of art and creativity). Through tile painting, participants were able to spend time focusing on art making rather than their cancer (distraction), as well as to express their emotions, thoughts, and experience about their cancer journey (self-expression). Overall, study participants reported that tile painting was relaxing and enjoyable while helping them to decrease their psychological symptoms (e.g., fear, distress).

Borderline Case.

If art making as a health intervention includes some of the defining attributes, but not all of them, it constitutes a borderline case. We identified a borderline case of art making as a health intervention in the study of Morrison et al., (2019). In this study, art making intervention has the following defining attributes: self-expression, creativity, and creation of art but not distraction. In Morrison et al., (2019)’s study, painting and drawing were used as a vehicle of self-expression for 28 military cancer patients. Study participants were able to either paint or draw (creation of art) freely (creativity), while expressing their emotions and thoughts about their cancer journeys (self-expression). This, in turn, helped them to regulate their emotions. Study participants reported a reduction in distress, anxiety, and depression.

Contrary Case.

A contrary case is a clear example of what art making is not. In the reviewed studies, we were not able to identify a contrary case of art making as a health intervention. We, therefore, created a contrary case. Individuals with a cancer diagnosis, for example, sometimes watch TV while they are waiting for their treatments and/or during the treatments (e.g., chemotherapy and blood transfusions). Though watching TV helped people, distracting them from their ongoing symptoms (e.g., pain), it is not considered art making because it prevents creativity and self-expression, though it will never be directly involved in the creation of an artwork.

Related Concepts

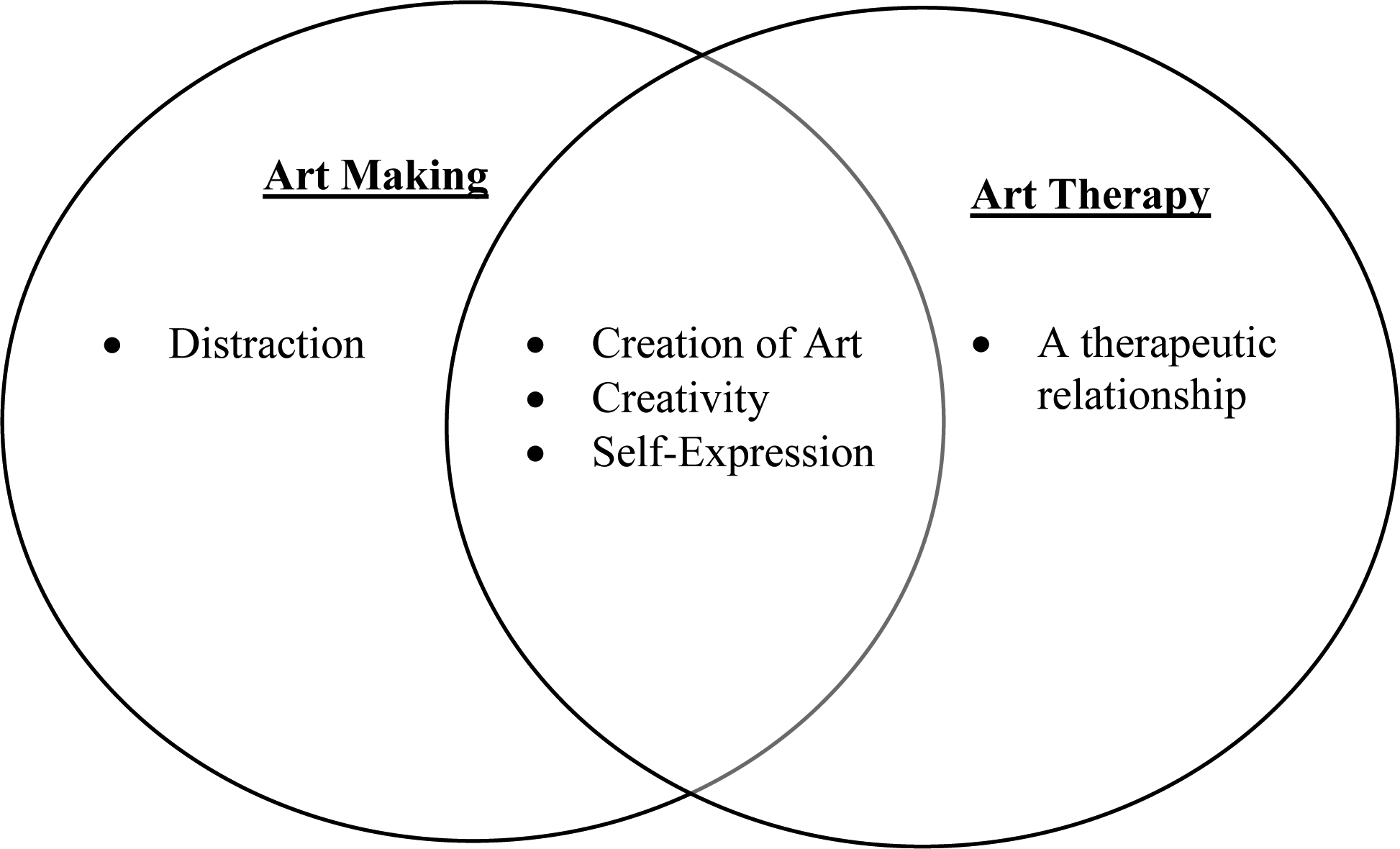

In our review, we found that the most frequently studied concept related to art making is art therapy (n=58). Using the definition from the AATA, we determined that art therapy shares some attributes with art making, including the creation of art, creativity, and self-expression (Figure 2). However, they differ in how they work to benefit the individual’s health. Art therapy benefits the individual patient through the creative self-expression of art making, which is maximized by a therapeutic relationship between an art therapist and a patient. Therefore, a therapeutic relationship between an art therapist and a patient became an essential characteristic for art therapy. Art making, on the other hand, benefits individual health through the functions of art making that provide creative distraction and self-expression.

Figure 2.

Related Concept: Attributes of Art Making and Art Therapy

During art therapy, an art therapist establishes a therapeutic relationship with their patients in order to achieve therapeutic goals. Therefore, the art therapist’s skills and experience become crucial because they influence the development of the therapeutic relationship. Once the therapeutic relationship is established, patients are able to deepen their self-discovery, self-exploration, self-control, and self-reflection through art making.23,24 For example, a study by Walker (2016) provided 15 art therapy sessions for veterans with chronic PTSD and traumatic brain injury (TBI). During art therapy sessions, a seasoned art therapist greatly helped each study participant to safely express their traumatic experiences, which led to ‘nonverbal discovery.’ Researchers in this study suggested that such deep self-expression from art making should be conducted only by an experienced art therapist. The presence of the art therapist also ensures that participants feel safe to express their emotions, thoughts, and experiences so that they can integrate them, connect them to their values, and create meaning through art making. As a result, participants experience growth and transformation. These achievements ultimately progress to liberation from their present conditions or situations and transcendence beyond their current states of being.

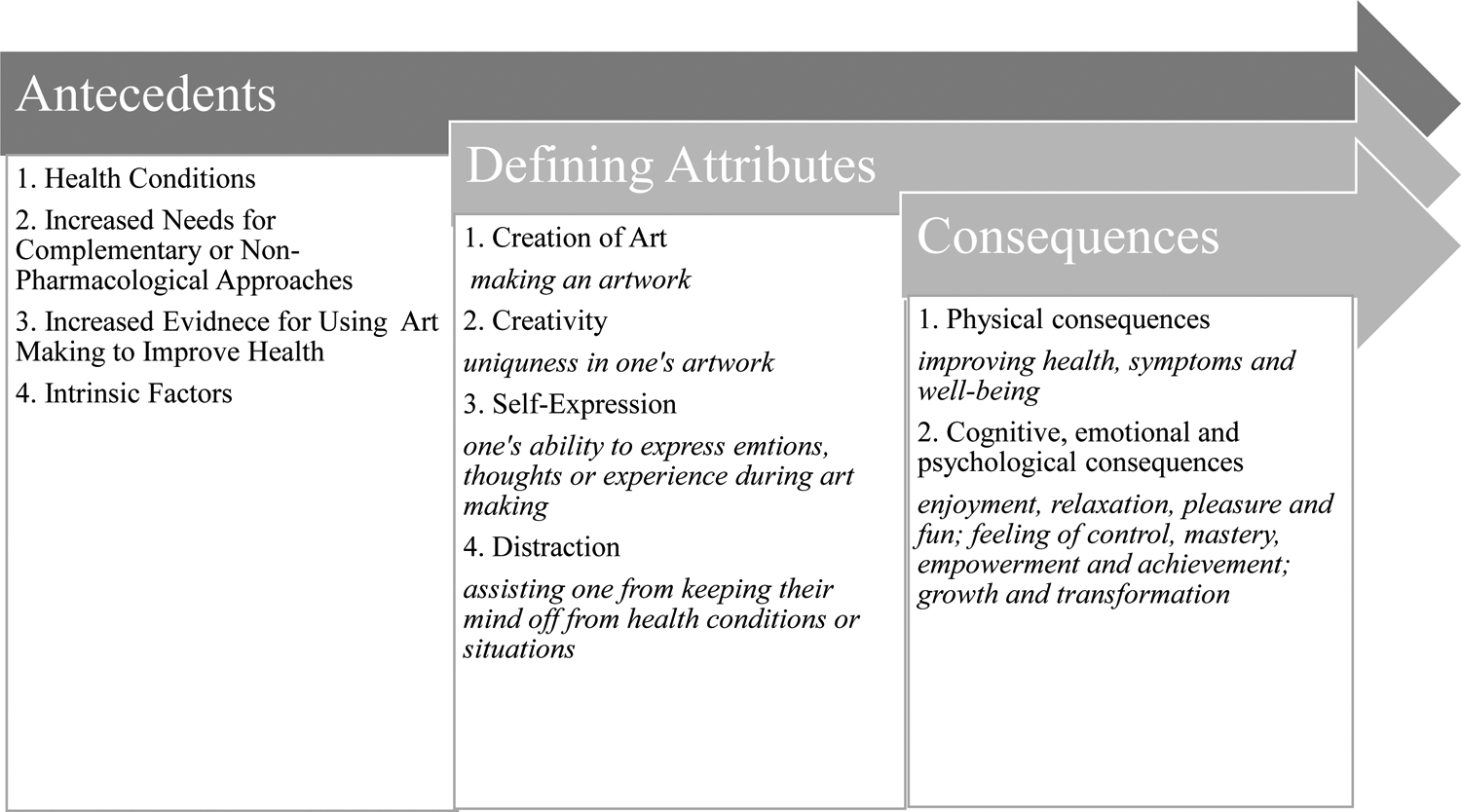

Antecedents

Antecedents are events or incidents that occur prior to the occurrence of the concept.18 There were four antecedents for art making as a health intervention (Figure 3). They included (1) health conditions, (2) increased need for nonpharmacological or complementary approaches, (3) increased evidence for using art making to improve health, and (4) intrinsic factors.

Figure 3.

Antecedents, Defining Attributes, and Consequences

Health conditions.

The most significant antecedent for using art making as a health intervention was to manage an individual health condition or improve the well-being of individuals. Researchers have asserted that art making could be a potential strategy to address individuals’ health conditions, including mental health (e.g., anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, stress, traumatic brain injury, and PTSD),33,39,42–42 various cancers (e.g., blood and marrow cancer, gynecologic cancer),7,14,22,44 cognitive diseases (e.g., dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and cognitive impairment),25–28 neurological diseases (e.g., stroke, Parkinson’s disease),26,29,30 and chronic conditions (e.g., chronic pain, multiple sclerosis, obesity, acquired brain injury).18,22,31–33

Increased need for nonpharmacological or complementary approaches.

Forty-eight studies described the increased need for nonpharmacological or complementary approaches as a reason for using art making as a health intervention. These studies reported that art making had gained increased attention and interest from researchers and clinicians. Since holistic approaches to health care have gained more attention than in the past, there is a need for complementary or non-pharmacological approaches to better manage patients’ health or symptoms.19–20,25,49 Moreover, some have argued that current pharmacological approaches can be used in combination with art making in order to reduce negative consequences (e.g., drug interaction, side effects),34–37 or enhance health benefits from pharmacological approaches.4,7,22,35,38

Increased evidence for using art making to improve health.

Thirty-one studies reported that there was an increase in evidence for the use of art making in improving health. As a result, researchers considered using art making in their health interventions and building more evidence to support the use of art making. Specifically, we believed that further study of art making can address some concerns about the existing state of the evidence for art making. These concerns included, but are not limited to, (1) most evidence was anecdotal, (2) study sample was homogenous, (3) sample size was small, and (4) few studies were randomized controlled trials.7,12,14,23,31,39,40

Intrinsic factors.

Other reasons for using art making as a health intervention included individual intrinsic factors. Some researchers recognized that individual intrinsic factors lead some participants to use art making. These intrinsic factors include the desire to overcome or move beyond one’s comfort zone, or having trust in art making.37,56 Other intrinsic factors include participants’ desire for different level of independence (e.g., own pace or degree of involvement) and their positive attitudes toward art making.19,27,58

Consequences

Consequences refer to what happens as a result of the occurrence of the concept, that is, art making.18 These included physical consequences (i.e., improved symptoms and well-being) as well as positive cognitive, emotional, and psychological consequences.14,18,19,21,41 In terms of physical consequences, for example, art making facilitates participants, who have physical limitations or disabilities as a result of their health conditions, to accept their physical limitations. It thereby allowed them to adjust to a new way of living or resume their normal life (e.g., they are able to relax and enjoy a part of their life despite their health conditions).18,20,42

Art making can also elicit positive cognitive, emotional, and/or psychological consequences for participants. For example, through art making, participants reported feeling enjoyment, relaxation, pleasure, and fun.10,21,43–45 At the same time, they reported feelings of control, mastery, empowerment, and achievement.17,19,46 Psychologically, art making intrinsically motivated participants to create meaning for themselves and/or their health experiences. Such intrinsic motivation allows participants to experience growth, as well as the transformation of their health experiences. Specifically, through art making, participants were able to discover, explore, control, and reflect on their own emotions, thoughts, or experiences. These self-actions naturally lead participants to integrate” and connect to their inner-selves, others and/or their environments, which helped them to “make meanings.30–31,55,62

Empirical Referents

According to Walker and Avant, empirical referents are the instruments that can quantify the concept.18 These are closely related to the defining attributes of the concept. In our concept analysis, however, we were not able to identify empirical referents that measure the defining attributes of art making as a health intervention. Instead, we found that art making as a health intervention was indirectly measured by quantifying its efficacy on various health outcomes (e.g., psychological or physical symptoms, cognitive functions, well-being, or ill-being).10,29,45,49–51

Discussion

Our concept analysis provides a better understanding of art making as a health intervention. In the past decade, art making has been adopted in various disciplines, designed and implemented for each discipline’s specific needs and various health concerns. While art therapy has been differentiated as a health intervention, art making has not. In our concept analysis, we were able to identify the distinct components of art making using Walker and Avant’s eight-step approach. The antecedents to art making as a health intervention included (1) the desire to improve and manage patients’ health conditions, (2) the desire to use nonpharmacological or complementary approaches, (3) the increased evidence for using art making, and (4) participant’s intrinsic factors. As defining attributes, creation of art, creativity, self-expression, and distraction were identified. Physical and cognitive, emotional, and psychological benefits to the participants were identified as the consequences of art making as a health intervention.

Most importantly, we were able to examine a related concept of art making – art therapy. Unlike art making, art therapy is a form of psychotherapy, focusing on creative self-expression, therapeutic relationship between a therapist and a participant, and using the visual arts (e.g., drawing, painting) as a nonverbal communication technique.8 As a result, some similarities and differences in consequences were found between art making and art therapy as a health intervention. For example, in art therapy, a participant can dive deeper into their emotions, thoughts, and experiences because of the presence of a therapeutic relationship between the participant and the art therapist.26,56,64–65 Within the therapeutic relationship, the participant can be guided and helped during their journey of self-expression by an art therapist, who sets the goals of art therapy to help participants safely and purposefully express whatever is in their minds. Therefore, participants in art therapy not only grow and are transformed, which can also be achieved in art making, but they also reach advanced stages of liberation from their present conditions or situations and transcendence beyond their current states of being. Future research could examine whether art making can have an impact on the nurse-patient relationship.

We found no consistent terminology used for art making across disciplines. Of note, the terms used in the nursing discipline showed greater variation compared to other disciplines. There were six different terms used for art making (Table 1) noted in the review: art making, art related activity, art intervention, creative art program, art program, and art-based intervention. Such diversity in terminology contributes to the existing confusion over the definition of art making as a health intervention. Hence, we recommend consistent usage of a single term to refer art making to improve communication about art making in nursing and other disciplines. In such a way, we can create a representative image of art making in across disciplines.

Table 1.

Terms Used Across Disciplines

| Discipline | Terms used |

|---|---|

| Art therapy (n=24) |

|

| Medicine (n=22) |

|

| Nursing (n=13) |

|

| Psychology (n=10) |

|

| Occupational Therapy (n=7) |

|

Note: we only provide the top 5

The findings of this study also revealed that art making as a health intervention involved either using art making activities directly (e.g., visual arts, performing arts, media arts, and/or creative writing) or as a component of a health intervention that is used in psychotherapy (i.e., art therapy or art psychotherapy). Through our analysis, we observed that researchers used multiple types of art making activities with participants, which provides participants with choice. Additionally, the art making activities were either done individually with the participant or in a group setting with varying intervention doses (e.g., frequency and duration of the intervention). These findings highlight the patient-centeredness of art making activity. However, it is still unclear which types of activities, delivery methods, and intervention doses work best for certain types of patient populations. Future research could focus on understanding populations of interest relating to each component of art making (e.g., type of art making, delivery method, intervention dose), as well as comparing and assessing the effectiveness of art making on various patient health outcomes.

We determined that the majority of the art making interventions in this concept analysis were used for persons with chronic illnesses or mental health problems, as well as for older persons. This finding indicates that art making interventions have been designed and implemented for some disadvantaged groups (e.g., those with mental health problems and older persons). However, we were not able to identify art making interventions for other disadvantaged groups such as children, migrants, minorities, and those with disabilities. This may be because we had specific inclusion criteria for the studies in this concept analysis (i.e., only included adults 18 years or older, focused on health outcomes, and written in English). Moreover, in the 85 reviewed studies, we were not able to find culturally sensitive art making interventions or any statement regarding individual backgrounds and cultural preferences. Therefore, there is a great opportunity for nurse researchers to explore and understand cultural differences in art making interventions, and to design/implement culturally sensitive art making interventions for marginalized or underrepresented populations.

The majority of the studies used a facilitator during the art making intervention. Yet the roles of the facilitator varied widely, depending on participants’ needs and preferences, from no need or merely observation15,18,20 to actively engaging in art making by offering instruction and/or assistance.14,25,29 For example, one may require a facilitator who provides art making instruction because of one’s lack of skills and knowledge in art making. In this case, a facilitator can develop an art making instruction including the types and medium of the art activities for their art making participants.12,27,45 In some cases, a facilitator offers physical assistant for the participants who are physically unable to make art without assistant in addition to art making instruction.30,45 On the other hand, one may not require or minimally requires a facilitator because they are previously exposed to art making or prefer to use other ways to get help during art making such as art making instruction book or YouTube video. Furthermore, we observed that even when a facilitator is not needed or present, participants in art making still gain physical, cognitive, emotional, and psychological benefits (e.g., improved symptoms, enjoyment, and relaxation). For this reason, we did not consider ‘a facilitator’ as a defining attribute of art making as a health intervention. This fact also clearly differentiates art making from art therapy, in which an art therapist is present and necessary to the process despite the participants’ skills/abilities and context, due to their therapeutic role in art therapy process.

Proposed Definition of Art Making

Based on this concept analysis, we are proposing that art making as a health intervention, defined as a creative diversional, and expressive process that allows an individual to create their own artwork to improve the individual’s physical, cognitive, emotional, and psychological health and/or well-being.

In our definition, we defined art making to include all the defining attributes identified in this concept analysis and an ultimate goal of art making as a health intervention. Our definition demonstrates the functions of art making (i.e., a creative diversional and expressive process to create own art work), and an ultimate goal of art making (i.e., to improve the individual’s physical, cognitive, emotional, and psychological health and/or well-being). Therefore, our definition provides a clear understanding of art making as a health intervention that is different from art therapy as a health intervention. We understand that art making focuses on the original functions of art making as a creative diversional and expressive process to benefit the individual’s health and well-being, rather than as a communication technique (i.e., expressive process) and a therapeutic relationship during psychotherapy as seen in art therapy.

Nursing Research and Practice Implications

We found that nursing was the third discipline that published and used art making as a health intervention. Specifically, 13 studies have a first author who is a nurse, and 7 studies were published in a nursing journal. This highlights the need for more nurse researchers and nursing journals to include topics such as art making health interventions in their areas of research and publication. This is important because nursing requires an understanding of both the sciences and the humanities as the basis for nursing research and practice.52

Multiple ways of knowing guide nurses about when to use art making as an intervention. Drawing on the work of Carper (1978) and Chin and Kramer (2009), we propose that there are five ways of knowing when to intervene by using art making with participants or patients—aesthetic, emancipatory, empirical, ethical, and personal.53–55 For example, suppose a patient newly diagnosed with stroke is admitted to the inpatient unit and reports feeling depressed. Prior to deciding whether art making is an appropriate intervention for the patient, the nurses will have to carefully consider the context of the situation (aesthetic), draw on her/his knowledge of stroke, depression, and the impact of art making (empirical), analyze any current dilemma between the patient’s stroke and his/her ability to participate in art making (ethical), evaluate the nurse’s own sense of the patient as a person (personal), and assess the context or the environment in which the patient can successfully participate in art making (emancipatory). All five ways of knowing are interrelated and overlapping. Each is necessary for understanding when to intervene by using art making.

Moreover, consistent with the American Holistic Nurses Association’s mission, art making is a holistic approach, incorporating a connection between body, mind, and spirit and their dynamic interaction.56 From our review, we learned that art making provides physical, cognitive, emotional, and psychological benefits for patients. Therefore, if nurses want to have a holistic impact on their patients’ well-being, art making is a possible health intervention to implement for their patients.

Art making has the potential to be designed as a patient-centered health intervention. This core concept is one of the highly regarded values of the nursing discipline.57,58 Thus, nurse researchers can design art making as a patient-centered health intervention, which accounts for individuals’ values and preferences relating to their health conditions58 and employs innovative delivery methods for all individuals despite geographic locations and abilities. Among the 85 reviewed studies, several of the art making interventions were tailored to be used by participants with physical limitations, although they did not describe their art making interventions as patient-centered.16,59 This provides nurse researchers and practitioners with ideas for designing and implementing patient-centered art making interventions, accounting for participants’ varying health conditions/needs and biopsychosocial characteristics, as well as their values and preferences relating to art making. Additionally, considering the four defining attributes that we identified in this concept analysis can help researchers in deciding what to consider when designing art making interventions.

In our analysis, three of the four attributes (i.e., creation of art, creativity, and self-expression) were frequently present in the reviewed studies. The attribute of distraction, however, only appeared in 10 studies where art making interventions were demonstrated as leisure and recreational activities.25,27,31,26 In these studies, participants focused on doing art making and enjoying art materials, which improved various chronic health conditions (e.g., multiple sclerosis, chronic pain, cancer) and symptoms.14,18,32,44,60 Further, we noticed that the attribute of self-expression can be safely brought out of each individual (e.g., trauma) when it is offered in art therapy within a therapeutic relationship between a participant and an art therapist.61,62 Therefore, we suggest that when nurse researchers try to maximize the health benefits from self-expression during an art making intervention, they should consider consulting with an art therapist prior to or during the design of their art making intervention. Alternatively, they could use art therapy instead. In most cases, we recommended designing art making interventions as actively engaging diversional leisure and/or recreational activities. That is, the art making intervention should focus on the attribute of distraction, which naturally allows participants to express their emotions, thoughts, and experiences at comfortable and acceptable levels. In this way, participants will be in a safe zone for their self-expression and will not require advanced level facilitators (e.g., art therapists) to help them during art making.

In practice, nurses can gain insights from our findings on the antecedents and consequences of art making when they decide which health conditions could benefit from art making as a health intervention. The antecedents and the consequences from this concept analysis can guide nurses to determine the goals and outcomes they want to achieve for their patients when using art making as a health intervention. Specifically, participants’ intrinsic factors can be enhanced when their environment is well designed.19,21,29,36,63 Therefore, nurses should consider how they can create a supportive, enabling, accepting environment where they can make participants feel comfortable and familiar. Most importantly, the environment should be non-threatening, non-judgmental, and non-competitive for participants to feel safe. Lastly, we also observed that the environment provides flexibility for different types of activity and safe materials (e.g., non-toxic, and odorless).

In this concept analysis, there were no instruments used to measure art making as a health intervention. The researchers in the reviewed studies instead measured the art making interventions indirectly by assessing various health benefits. This highlights the need for instrument and measurement research to evaluate art making as a health intervention. Such an instrument would allow nurses to evaluate and design art making accordingly and to understand inconsistent effects and unexpected outcomes of art making intervention. In order to develop an instrument for art making as a health intervention, nurse researchers can develop items for each of the defining attributes that we identified in this concept analysis and individually evaluate them. One way to start developing such instrument is to refer to existing instruments. For example, there is an existing instrument in art therapy that captures the defining attributes of self-expression and creativity in art making - the Diagnostic Drawing Series (DDS) - that researcher could adapt from.64 Reviewing and adapting the DDS could provide nurse researchers a starting point and idea of what to look for and how to formulate items for the defining attributes of self-expression and creativity in art making as a health intervention.

Conclusion

In our concept analysis, we were able to understand the current uses of, and to provide a clear definition of, art making as a health intervention through identifying the distinctive components of art making. Several nursing research and practical implications were suggested in which nurses can design and implement art making as a health intervention inspiring the values of nursing practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors express gratitude to Dr. Janice Staab for her writing assistance and constructive feedback on later version of this manuscript. Dr. Kyung Soo Kim is a postdoctoral fellow in Pain and Associated Symptoms at the University of Iowa, College of Nursing, supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health (T32 NR011147). Dr. Maichou Lor was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23NR019289. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that we have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

No external funding

Contributor Information

Kyung Soo Kim, University of Iowa College of Nursing, 50 Newton Rd, Iowa City, IA 52246.

Maichou Lor, University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Nursing, 701 Highland Ave. Madison, WI 53705.

References

- 1.The Story of Art, Luxury Edition by E H Gombrich. Phaidon Press; 1710. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dossey BM. Florence Nightingale’s Vision for Health and Healing. J Holist Nurs. 2010;28(4):221–224. doi: 10.1177/0898010110383111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pratt R. THE ARTS IN HEALTHCARE MOVEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES. :68.

- 4.Abbing A, Baars EW, de Sonneville L, Ponstein AS, Swaab H. The Effectiveness of Art Therapy for Anxiety in Adult Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front Psychol. 2019;10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi H, Jung DJ, Jeon YH, Kim MJ. The effects of combining art psychotherapy with pharmacotherapy in treating major depressive disorder: Randomized control study. Arts Psychother. 2020;70:101689. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2020.101689 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keating F, Cole L, Grant R. An evaluation of group reminiscence arts sessions for people with dementia living in care homes. Dement Lond Engl. 2020;19(3):805–821. doi: 10.1177/1471301218787655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saw JJ, Curry EA, Ehlers SL, et al. A brief bedside visual art intervention decreases anxiety and improves pain and mood in patients with haematologic malignancies. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27(4):e12852. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Art Therapy Association. American Art Therapy Association. Accessed March 29, 2021. https://arttherapy.org/

- 9.Gras M, Daguenet E, Brosse C, Beneton A, Morisson S. Art Therapy Sessions for Cancer Patients: A Single-Centre Experience. Oncology. 2020;98(4):216–221. doi: 10.1159/000504448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guseva E. Bridging Art Therapy and Neuroscience: Emotional Expression and Communication in an Individual with Late-Stage Alzheimer’s. Art Ther J Am Art Ther Assoc. 2018;35(3):138–147. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2018.1524260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radl D, Vita M, Gerber N, Gracely EJ, Bradt J. The effects of Self-Book© art therapy on cancer-related distress in female cancer patients during active treatment: A randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2018;27(9):2087–2095. doi: 10.1002/pon.4758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seifert K, Spottke A, Fliessbach K. Effects of sculpture based art therapy in dementia patients-A pilot study. Heliyon. 2017;3(11):e00460. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2017.e00460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiswell S, Bell JG, McHale J, Elliott JO, Rath K, Clements A. The effect of art therapy on the quality of life in patients with a gynecologic cancer receiving chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;152(2):334–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraser C, Keating M. The Effect of a Creative Art Program on Self-Esteem, Hope, Perceived Social Support, and Self-Efficacy in Individuals With Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study. J Neurosci Nurs. 2014;46(6):330. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0000000000000094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly CG, Cudney S, Weinert C. Use of Creative Arts as a Complementary Therapy by Rural Women Coping With Chronic Illness. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30(1):48–54. doi: 10.1177/0898010111423418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peisah C, Lawrence G, Reutens S. Creative solutions for severe dementia with BPSD: a case of art therapy used in an inpatient and residential care setting. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(6):1011–1013. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211000457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stace SM. Therapeutic Doll Making in Art Psychotherapy for Complex Trauma. Art Ther J Am Art Ther Assoc. 2014;31(1):12–20. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2014.873689 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunt L, Nikopoulou-Smyrni P, Reynolds F. “It gave me something big in my life to wonder and think about which took over the space … and not MS”: managing well-being in multiple sclerosis through art-making. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(14):1139–1147. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.833303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phinney A, Moody EM, Small JA. The Effect of a Community-Engaged Arts Program on Older Adults’ Well-being. Can J Aging Rev Can Vieil. 2014;33(3):336–345. doi: 10.1017/S071498081400018X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Symons J, Clark H, Williams K, Hansen E, Orpin P. Visual Art in Physical Rehabilitation: Experiences of People with Neurological Conditions. Br J Occup Ther. 2011;74(1):44–52. doi: 10.4276/030802211X12947686093729 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirshbaum MN, Ennis G, Waheed N, Carter F. Art in cancer care: Exploring the role of visual art-making programs within an Energy Restoration Framework. Eur J Oncol Nurs Off J Eur Oncol Nurs Soc. 2017;29:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsen DJ, Stege R, King R, Egeli N. The hope collage activity: an arts-based group intervention for people with chronic pain. Br J Guid Couns. 2018;46(6):722–737. doi: 10.1080/03069885.2018.1453046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tucknott-Cohen T, Ehresman C. Art Therapy for an Individual With Late Stage Dementia: A Clinical Case Description. Published online 2016. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2016.1127710 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walker MS, Kaimal G, Koffman R, DeGraba TJ. Art therapy for PTSD and TBI: A senior active duty military service member’s therapeutic journey. Arts Psychother. 2016;49:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2016.05.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beauchet O, Launay C, Annweiler C, Remondière S, Decker L de. Geriatric Inclusive Art and Risk of In-Hospital Mortality in Inpatients with Dementia: Results from a Quasi-Experimental Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(3):573–575. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elkis-Abuhoff DL, Goldblatt RB, Gaydos M, Convery C. A pilot study to determine the psychological effects of manipulation of therapeutic art forms among patients with Parkinson’s disease. Int J Art Ther Inscape. 2013;18(3):113–121. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2013.797481 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Esker SN, Ashton C. Using Art to Decrease Passivity in Older Adults with Dementia. Annu Ther Recreat. 2013;21:3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Safar LT, Press DZ. Art and the Brain: Effects of Dementia on Art Production in Art Therapy. Art Ther J Am Art Ther Assoc. 2011;28(3):96–103. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2011.599734 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baumann M, Peck S, Collins C, Eades G. The meaning and value of taking part in a person-centred arts programme to hospital-based stroke patients: findings from a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(3):244–256. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.694574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sit JWH, Chan AWH, So WKW, et al. Promoting Holistic Well-Being in Chronic Stroke Patients Through Leisure Art-Based Creative Engagement. Rehabil Nurs Off J Assoc Rehabil Nurses. 2017;42(2):58–66. doi: 10.1002/rnj.177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guay M. Impact of Group Art Therapy on the Quality of Life for Acquired Brain Injury Survivors. Art Ther J Am Art Ther Assoc. 2018;35(3):156–164. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2018.1527638 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Neill A, Moss H. A Community Art Therapy Group for Adults With Chronic Pain. Art Ther J Am Art Ther Assoc. 2015;32(4):158–167. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2015.1091642 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sudres JL, Anzules C, Sanguignol F, Pataky Z, Brandibas G, Golay A. Therapeutic patient education with art therapy: effectiveness among obese patients. Educ Thérapeutique Patient - Ther Patient Educ. 2013;5(2):213–218. doi: 10.1051/tpe/2013032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bozcuk H, Ozcan K, Erdogan C, Mutlu H, Demir M, Coskun S. A comparative study of art therapy in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy and improvement in quality of life by watercolor painting. Complement Ther Med. 2017;30:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2016.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ciasca EC, Ferreira RC, Santana CLA, et al. Art therapy as an adjuvant treatment for depression in elderly women: a randomized controlled trial. Rev Bras Psiquiatr Sao Paulo Braz 1999. 2018;40(3):256–263. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Humphrey J, Montemuro M, Coker E, et al. Artful Moments: A framework for successful engagement in an arts-based programme for persons in the middle to late stages of dementia. Dementia. 2019;18(6):2340–2360. doi: 10.1177/1471301217744025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nan JKM, Ho RTH. Effects of clay art therapy on adults outpatients with major depressive disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2017;217:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Savazzi F, Isernia S, Farina E, et al. “Art, Colors, and Emotions” Treatment (ACE-t): A Pilot Study on the Efficacy of an Art-Based Intervention for People With Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1467. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lefèvre C, Ledoux M, Filbet M. Art therapy among palliative cancer patients: Aesthetic dimensions and impacts on symptoms. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14(4):376–380. doi: 10.1017/S1478951515001017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Lith T. Art Making as a Mental Health Recovery Tool for Change and Coping. Art Ther J Am Art Ther Assoc. 2015;32(1):5–12. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2015.992826 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crone DM, O’Connell EE, Tyson PJ, Clark-Stone F, Opher S, James DVB. “Art Lift” intervention to improve mental well-being: an observational study from U.K. general practice. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2013;22(3):279–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00862.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blomdahl C, Wijk H, Guregård S, Rusner M. Meeting oneself in inner dialogue: a manual-based Phenomenological Art Therapy as experienced by patients diagnosed with moderate to severe depression. Arts Psychother. 2018;59:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2017.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Morais AH, Roecker S, Salvagioni DAJ, Eler GJ. Significance of clay art therapy for psychiatric patients admitted in a day hospital. Investig Educ En Enfermeria. 2014;32(1):128–138. doi: 10.17533/udea.iee.v32n1a15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glinzak L. Effects of Art Therapy on Distress Levels of Adults With Cancer: A Proxy Pretest Study. Art Ther J Am Art Ther Assoc. 2016;33(1):27–34. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2016.1127687 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sauer PE, Fopma-Loy J, Kinney JM, Lokon E. “It makes me feel like myself”: Person-centered versus traditional visual arts activities for people with dementia. Dement Lond Engl. 2016;15(5):895–912. doi: 10.1177/1471301214543958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morris JH, Kelly C, Toma M, et al. Feasibility study of the effects of art as a creative engagement intervention during stroke rehabilitation on improvement of psychosocial outcomes: study protocol for a single blind randomized controlled trial: the ACES study. Trials. 2014;15(1):380. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ching-Teng Y, Ya-Ping Y, Yu-Chia C. Positive effects of art therapy on depression and self-esteem of older adults in nursing homes. Soc Work Health Care. 2019;58(3):324–338. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2018.1564108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schouten KA, van Hooren S, Knipscheer JW, Kleber RJ, Hutschemaekers GJM. Trauma-Focused Art Therapy in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Pilot Study. J Trauma Dissociation Off J Int Soc Study Dissociation ISSD. 2019;20(1):114–130. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2018.1502712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee R, Wong J, Lit Shoon W, et al. Art therapy for the prevention of cognitive decline. Arts Psychother. 2019;64:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2018.12.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poulos RG, Marwood S, Harkin D, et al. Arts on prescription for community-dwelling older people with a range of health and wellness needs. Health Soc Care Community. 2019;27(2):483–492. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sabo BM, Thibeault C. “I’m still who I was” creating meaning through engagement in art: The experiences of two breast cancer survivors. Eur J Oncol Nurs Off J Eur Oncol Nurs Soc. 2012;16(3):203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kooken WC, Kerr N. Blending the liberal arts and nursing: Creating a portrait for the 21st century. J Prof Nurs. 2018;34(1):60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2017.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johns C. Framing learning through reflection within Carper’s fundamental ways of knowing in nursing. J Adv Nurs. 1995;22(2):226–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.22020226.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thorne S. Rethinking Carper’s personal knowing for 21st century nursing. Nurs Philos. 2020;21(4):e12307. doi: 10.1111/nup.12307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gurm B. Multiple Ways of Knowing in Teaching and Learning. Int J Scholarsh Teach Learn. 2013;7(1). doi: 10.20429/ijsotl.2013.070104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Home. Accessed November 16, 2021. https://www.ahna.org/

- 57.Lauver DR, Ward SE, Heidrich SM, et al. Patient-centered interventions. Res Nurs Health. 2002;25(4):246–255. doi: 10.1002/nur.10044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ortiz MR. Patient-Centered Care: Nursing Knowledge and Policy. Nurs Sci Q. 2018;31(3):291–295. doi: 10.1177/0894318418774906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin MH, Moh SL, Kuo YC, et al. Art therapy for terminal cancer patients in a hospice palliative care unit in Taiwan. Palliat Support Care. 2012;10(1):51–57. doi: 10.1017/S1478951511000587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Safrai MB. Art Therapy in Hospice: A Catalyst for Insight and Healing. Art Ther J Am Art Ther Assoc. 2013;30(3):122–129. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2013.819283 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mahendran R, Rawtaer I, Fam J, et al. Art therapy and music reminiscence activity in the prevention of cognitive decline: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):324. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2080-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pike AA. The Effect of Art Therapy on Cognitive Performance Among Ethnically Diverse Older Adults. Art Ther J Am Art Ther Assoc. 2013;30(4):159–168. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2014.847049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hanevik H, Hestad KA, Lien L, Teglbjaerg HS, Danbolt LJ. Expressive art therapy for psychosis: A multiple case study. Arts Psychother. 2013;40(3):312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2013.05.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cohen BM, Hammer JS, Singer S. The diagnostic drawing series: A systematic approach to art therapy evaluation and research. Arts Psychother. 1988;15(1):11–21. doi: 10.1016/0197-4556(88)90048-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]