Abstract

Introduction:

Urgency, the immediate need to defecate, is common in active ulcerative colitis (UC). We investigated the association of urgency in UC patients with 1) quality of life (QoL) domains and 2) future hospitalizations, corticosteroid use, and colectomy for UC.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional and subsequent longitudinal study within IBD Partners, a patient-powered research network. We described associations of levels of urgency in UC patients with Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) QoL domains. We conducted a longitudinal cohort to determine associations between baseline urgency and subsequent hospitalization, corticosteroid use, or colectomy for UC within 12 months. We used bivariate statistics and logistic regression models to describe independent associations.

Results:

A total of 632 UC patients were included in the cross-sectional study. After adjusting for clinical variables, rectal bleeding, and stool frequency, urgency defined as “hurry”, “immediately” and “incontinence” increased the odds of social impairment (OR 2.05 95% CI [1.24-3.4], OR 2.76 95% CI [1.1-6.74], and OR 7.7 95% CI [1.66-38.3] respectively) compared to “no hurry”. Urgency also significantly increased the odds of depression, anxiety, and fatigue. Urgency was associated with a significant increase in risk of hospitalizations, corticosteroids, while “hurry”, “immediately” and “incontinence” increased the odds of colectomy within 12 months by 1.42[1.15-1.75], 1.90[1.45-2.50], and 3.69[2.35-5.80].

Discussion:

We demonstrated that urgency is a patient reported outcome (PRO) independently associated with compromised QoL and future risk of hospitalizations, corticosteroids, and colectomy. Our findings support the consideration of urgency as a UC-specific PRO and its use as an outcome in clinical trials to capture QoL and risk of clinical decompensation.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, urgency, colectomy, PROMIS, quality of life, hospitalizations

INTRODUCTION

One of the hallmark symptoms of ulcerative colitis (UC) is urgency, the uncomfortable sensation of having to defecate immediately which can create a significant burden for patients. Urgency has been noted in 85% of patients with active UC and observed in patients with both distal and pancolonic involvement[1]. In fact, a prospective cohort of UC patients demonstrated that 92% experienced urgency with active total colitis while only 11% had urgency with quiescent disease [1]. In a survey of 501 UC patients, bowel urgency impacted daily life in 44% of participants. Interestingly, urgency existed in some patients independent of frequent stools or rectal bleeding[2]. Rasmussen et al showed in a cross sectional study of 743 UC patients that urgency decreased QoL, measured by the SF-36, after adjusting for treatment, age, and clinical manifestations[3].

Physiologically, urgency is caused by increased rectal sensitivity from inflammation and associated spasm[4]. Urgency was incorporated into the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI), a clinical activity index consisting of five parameters, to evaluate UC flares[5]. However, the SCCAI has largely been replaced in clinical practice by the simplified Mayo score and PRO-2, both of which do not include urgency scales [6–8].

We therefore aimed to understand the association between urgency and 1) quality of life and 2) longitudinal clinical outcomes. We investigated whether urgency is independently associated with PROMIS quality of life (QoL) measures. Additionally, we used longitudinal data to describe associations between urgency and future clinical outcomes. Ideally, identifying UC-related patient-reported outcomes that most notably impair QoL and predict poor clinical outcomes will lead to patient-centric outcome measures incorporated both in the clinic and therapeutic trials.

METHODS

Study design

Cross sectional aim

We conducted a cross-sectional study investigating the association between bowel urgency and QoL, measured by the PROMIS criteria, within IBD Partners, the patient-powered research network of the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation[9]. For this study aim, we included participants where urgency was assessed using the following question from the SCCAI: “what has been your urgency of defecation?” with responses of “no hurry”, “hurry”, “immediately”, or “incontinence”. The SCCAI has been shown to correlate strongly with the Powell-Tuck index and biochemical markers of disease activity[5]. The main outcome was an alteration in the following PROMIS domains, defined as dichotomous variable using a cut-off of a 0.5 standard deviation score in the direction of impaired QoL: depression, anxiety, fatigue, impaired social satisfaction, pain, and sleep quality. For example, patients were labeled as “depressed” for a score ≥ 55 and “not depressed” for a score <55. For social satisfaction, a score ≤45 was deemed “impaired social satisfaction”. These definitions incorporate a clinically significant change and have been used previously in studies of IBD and other chronic disease states[10–14].

For inclusion in this portion of this study, patients were required to have a diagnosis of UC, and complete the SCCAI and PROMIS assessments. Exclusion criteria included prior bowel surgery, active reported corticosteroid prescription, and pregnancy as these are known to substantially confound urgency or QoL.

The following variables were included as covariates: age, years since diagnosis, sex, BMI, education level, race, smoking status, urgency, rectal bleeding, stool frequency, biologic use, aminosalicylate (5-ASA) use, immunomodulator use, and prior IBD hospitalization.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate analyses were performed. Continuous variables were summarized with means and standard deviations (SDs) utilizing the t-test. Categorical variables were expressed as proportions and compared using the Fisher exact and chi-squared testing. Multivariable logistic regression model was employed to evaluate the clinical and demographic characteristics associated with PROMIS outcomes. The final logistic regression model included all variables above as determined by a directed-acyclic graph associating urgency with QoL domains.

Longitudinal Aim

We conducted a longitudinal cohort study from patients within IBD Partners from 2012-2020 to assess the separate associations of self-reported urgency with hospitalizations, corticosteroid use, and colectomy within a 12-month window from time of survey. As described previously, surveys in IBD Partners are completed at baseline and follow-up surveys offered at 6-month intervals[9].

The longitudinal study population consisted of patients who completed at least two different surveys throughout the study period. Additional inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of UC and completion of the SCCAI and relevant clinical outcome assessments (hospitalization, corticosteroid use, and colectomy). Individuals were excluded during all time-points of active pregnancy. Three separate cohorts were identified for hospitalizations, corticosteroid use, and surgery in which participants were free from the outcome at baseline. Only participants who had at least one follow up survey within a 12-month period were included.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate analyses were performed to describe clinical characteristics at baseline. For continuous variables, t-tests were used to provide means and SDs. Univariate logistic regression models were utilized, pooled for repeat measurements from the same individual. Multivariate pooled logistic regression models were utilized to determine the relationship between urgency and clinical outcomes, adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and biologic use.

RESULTS

Quality of Life Assessments

A total of 632 patients were included in the cross-sectional analysis. The mean age was 46 years with a standard deviation of 14, 90% of patients were non-Hispanic white, 38% were on biologic therapy, 39% had been previously hospitalized for UC, and 81% had at least a college degree. Among all 632 patients, 47% reported “no urgency”, 44% “hurry”, 7% “immediately”, and 1% “incontinence” (Table 1). Urgency was not strongly correlated with stool frequency (r= 0.51, p<.001) or rectal bleeding (r= 0.39, p<.001).

Table 1.

Comparisons of clinical and demographic characteristics among UC patients in IBD Partners, stratified by degree of urgency in cross-sectional QoL cohort

| Characteristic | No hurry N = 301 |

Hurry N = 277 |

Immediately N = 45 |

Incontinence N = 9 |

p-value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % or mean (SD) | N | % or mean (SD) | N | % or mean (SD) | N | % or mean (SD) | ||

| Race | 0.2 | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 273 | 91 | 247 | 89 | 41 | 91 | 7 | 78 | |

| Hispanic | 9 | 3 | 12 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 8 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 9 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 | |

| Age | 301 | 47(14) | 277 | 43(15) | 45 | 49(15) | 9 | 44(17) | 0.002 |

| Sex | 0.026 | ||||||||

| Male | 195 | 65 | 206 | 74 | 35 | 78 | 8 | 89 | |

| Female | 106 | 35 | 71 | 26 | 10 | 22 | 1 | 11 | |

| Body mass index | 301 | 24.9(5) | 277 | 25.4(6) | 45 | (27.1)6 | 9 | 24.8(6) | 0.057 |

| Ever hospitalized | 116 | 39 | 110 | 40 | 19 | 42 | 4 | 44 | >0.9 |

| Stool frequency | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Normal | 252 | 84 | 129 | 47 | 6 | 13 | 2 | 22 | |

| 1-2 stools per day above normal | 42 | 14 | 100 | 36 | 7 | 16 | 4 | 44 | |

| 3-4 stools per day above normal | 6 | 2 | 37 | 13 | 17 | 38 | 2 | 22 | |

| 5+ stools per day above normal | 1 | 0 | 11 | 4 | 15 | 33 | 1 | 11 | |

| Rectal bleeding | <0.001 | ||||||||

| No blood | 273 | 91 | 168 | 61 | 21 | 47 | 2 | 22 | |

| A little blood | 27 | 9 | 89 | 32 | 9 | 20 | 5 | 56 | |

| Occasionally a lot of blood | 1 | 0 | 19 | 7 | 9 | 20 | 1 | 11 | |

| Usually a lot of blood | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 13 | 1 | 11 | |

| Current 5-ASA use | 184 | 61 | 159 | 57 | 31 | 69 | 6 | 67 | 0.5 |

| Current biologic use | 114 | 38 | 104 | 38 | 18 | 40 | 3 | 33 | >0.9 |

| Current immunomodulator use | 65 | 22 | 58 | 21 | 8 | 18 | 2 | 22 | >0.9 |

| Years since diagnosis | 301 | 16(11) | 277 | 14(11) | 15(11) | 9 | 14(15) | 0.029 | |

| PROMIS T scores ° | |||||||||

| Anxiety | 301 | 48(8) | 277 | 51(9) | 45 | 50(10) | 9 | 55(9) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 301 | 45(6) | 277 | 48(8) | 45 | 48(9) | 9 | 54(10) | <0.001 |

| Fatigue | 301 | 46(10) | 277 | 53(9) | 45 | 55(11) | 9 | 56(10) | <0.001 |

| Sleep | 301 | 48(8) | 277 | 50(8) | 45 | 50(8) | 9 | 49(6) | 0.048 |

| Social satisfaction | 301 | 57(9) | 277 | 52(9) | 45 | 47(9) | 9 | 44(13) | <0.001 |

| Pain | 301 | 45(6) | 277 | 49(8) | 45 | 54(10) | 9 | 53(6) | <0.001 |

One-way ANOVA; Pearson’s Chi-squared test

Patient reported outcome information measurement system items are measure so that US general population mean is 50 and the standard deviation is 10. Higher scores indicate more of the domain being measured.

UC= ulcerative colitis, IBD= inflammatory bowel disease, QoL= quality of life, 5-ASA=5-aminosalicylate, PROMIS= Patient Reported Outcome Information Measurement System, SD=standard deviation

In the multivariate analysis, when compared to patients with an urgency level of “no hurry”, those patients with an urgency level of “hurry” demonstrated a significantly increased odds of depression (odds ratio [OR] 3.03, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.82-5.15) (Table 2). Patients with “incontinence” demonstrated an even greater increase in the odds of depression (OR 13.7, 95% CI 2.95-68.0) compared to patients with “no hurry”. Rectal bleeding and stool frequency were not significantly associated with depression. Similarly, patients with an urgency level of “hurry” demonstrated an increased odds of anxiety (OR 2.15, 95% CI 1.4-3.3) as did patients with “incontinence” (OR 5.45, 95% CI 1.21-26.5) (Table 2). Rectal bleeding and stool frequency were not associated with anxiety. Patients who reported “1-2 bowel movements above normal” had an increased risk of fatigue (OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.14-2.87), along with patients with “5+ bowel movements above normal” (OR 3.09, 95% CI 1.08-9.05) (Table 3). Patients who reported “hurry” also had an increased odds of fatigue (OR 1.95, 95% CI 1.27-3.01) compared to those patients with “no hurry”.

Table 2:

Multivariate adjusted models for depression and anxiety PROMIS measures by UC-related symptoms

| Odds of Depression Based on UC Characteristics | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Stool frequency | ||

| Normal | — | — |

| 1-2 stools per day above normal | 1.06 | 0.62, 1.78 |

| 3-4 stools per day above normal | 0.79 | 0.36, 1.67 |

| 5+ stools per day above normal | 2.75 | 0.94, 8.12 |

| Urgency | ||

| No hurry | — | — |

| Hurry | 3.03 | 1.82, 5.15 |

| Immediately | 2.3 | 0.84, 5.99 |

| Incontinence | 13.7 | 2.95, 68.0 |

| Rectal bleeding | ||

| No blood | — | — |

| A little blood | 1.07 | 0.63, 1.80 |

| Occasionally a lot of blood | 1.29 | 0.47, 3.34 |

| Usually a lot of blood | 0.48 | 0.06, 2.89 |

| Odds of Anxiety Based on UC Characteristics | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

| Stool frequency | ||

| Normal | — | — |

| 1-2 stools per day above normal | 0.84 | 0.53, 1.33 |

| 3-4 stools per day above normal | 1 | 0.50, 1.99 |

| 5+ stools per day above normal | 1.65 | 0.58, 4.69 |

| Urgency | ||

| No hurry | — | — |

| Hurry | 2.15 | 1.40, 3.30 |

| Immediately | 1.53 | 0.63, 3.62 |

| Incontinence | 5.45 | 1.21, 26.5 |

| Rectal bleeding | ||

| No blood | — | — |

| A little blood | 1.23 | 0.77, 1.95 |

| Occasionally a lot of blood | 1.24 | 0.49, 3.05 |

| Usually a lot of blood | 0.29 | 0.04, 1.72 |

OR adjusted for race, smoking status, education, age, sex, biologic/immunomodulator/5-ASA use, time from diagnosis, prior hospitalization

UC= ulcerative colitis, 5-ASA=5-aminosalicylate, PROMIS= Patient Reported Outcome Information Measurement System, OR= odds ratio, CI= confidence interval

Table 3:

Multivariate adjusted models for fatigue and sleep impairment PROMIS measures by UC related symptoms

| Odds of Fatigue Based on UC Characteristics | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Stool frequency | ||

| Normal | — | — |

| 1-2 stools per day above normal | 1.81 | 1.14, 2.87 |

| 3-4 stools per day above normal | 1.88 | 0.93, 3.79 |

| 5+ stools per day above normal | 3.09 | 1.08, 9.05 |

| Urgency | ||

| No hurry | — | — |

| Hurry | 1.95 | 1.27, 3.01 |

| Immediately | 1.66 | 0.69, 3.91 |

| Incontinence | 1.6 | 0.32, 7.53 |

| Rectal bleeding | ||

| No blood | — | — |

| A little blood | 1.28 | 0.79, 2.04 |

| Occasionally a lot of blood | 0.86 | 0.33, 2.15 |

| Usually a lot of blood | 1.78 | 0.31, 14.7 |

| Odds of Sleep Impairment Based on UC Characteristics | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

| Stool frequency | ||

| Normal | — | — |

| 1-2 stools per day above normal | 1.15 | 0.67, 1.97 |

| 3-4 stools per day above normal | 1.09 | 0.46, 2.42 |

| 5+ stools per day above normal | 2.6 | 0.82, 7.96 |

| Urgency | ||

| No hurry | — | — |

| Hurry | 0.8 | 0.48, 1.31 |

| Immediately | 0.91 | 0.33, 2.35 |

| Incontinence | 1.04 | 0.13, 5.55 |

| Rectal bleeding | ||

| No blood | — | — |

| A little blood | 1.36 | 0.79, 2.32 |

| Occasionally a lot of blood | 0.5 | 0.12, 1.68 |

| Usually a lot of blood | 3.82 | 0.67, 24.7 |

OR adjusted for race, smoking status, education, age, sex, biologic/immunomodulator/5-ASA use, time from diagnosis, prior hospitalization

UC= ulcerative colitis, 5-ASA=5-aminosalicylate, PROMIS= Patient Reported Outcome Information Measurement System, OR= odds ratio, CI= confidence interval

Urgency was also associated with social impairment (Table 4). When compared to patients with “no hurry”, patients with “hurry” had an increased odds of social impairment (OR 2.05, 95% CI 1.24-3.4), as did patients with an urgency level of “immediately” (OR 2.76, 95% CI 1.10 - 6.77) and “incontinence” (OR 7.70, 95% CI 1.66-38.3).

Table 4:

Multivariate adjusted models for social impairment and pain PROMIS measures by UC related symptoms

| Odds of Social Impairment Based on UC Characteristics | Odds ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Stool frequency | ||

| Normal | — | — |

| 1-2 stools per day above normal | 1.33 | 0.79, 2.23 |

| 3-4 stools per day above normal | 1.82 | 0.87, 3.76 |

| 5+ stools per day above normal | 4.49 | 1.53, 13.4 |

| Urgency | ||

| No hurry | — | — |

| Hurry | 2.05 | 1.24, 3.40 |

| Immediately | 2.76 | 1.10, 6.77 |

| Incontinence | 7.7 | 1.66, 38.3 |

| Rectal bleeding | ||

| No blood | — | — |

| A little blood | 0.95 | 0.55, 1.59 |

| Occasionally a lot of blood | 0.43 | 0.13, 1.22 |

| Usually a lot of blood | 1.16 | 0.20, 7.41 |

| Odds of Pain Based on UC Characteristics | Odds ratio | 95% CI |

| Stool frequency | ||

| Normal | — | — |

| 1-2 stools per day above normal | 1.61 | 0.95, 2.71 |

| 3-4 stools per day above normal | 3.3 | 1.60, 6.79 |

| 5+ stools per day above normal | 8.97 | 2.96, 29.4 |

| Urgency | ||

| No hurry | — | — |

| Hurry | 1.37 | 0.82, 2.29 |

| Immediately | 1.51 | 0.59, 3.77 |

| Incontinence | 5.15 | 1.11, 29.5 |

| Rectal Bleeding | ||

| No blood | — | — |

| A little blood | 2.48 | 1.48, 4.12 |

| Occasionally or usually a lot of blood | 2.44 | 0.97, 6.13 |

OR adjusted for race, smoking status, education, age, sex, biologic/immunomodulator/5-ASA use, time from diagnosis, prior hospitalization

UC= ulcerative colitis, 5-ASA=5-aminosalicylate, PROMIS= Patient Reported Outcome Information Measurement System, OR= odds ratio, CI= confidence interval

Patients with “incontinence” had significantly more pain (OR 5.15, 95% CI 1.11 - 29.5) than patients with “no hurry” (Table 4). Those patients with increased bowel frequency also demonstrated an increased odds of pain as determined by the PROMIS measures. Patients with “3-4 bowel movements above normal” experienced increased odds of pain (1.61, 95% CI 0.95-2.71) as well as patients with “5+ bowel movements above normal” (3.30 95% CI 1.60-6.79). Patients who reported “a little blood” also demonstrated an increased odds of having a high pain PROMIS score (OR 2.48, 95% CI 1.48 -4.12) compared to those reporting “no blood”. Neither rectal bleeding, stool frequency, or urgency were significantly associated with the PROMIS domain of sleep quality. These associations were durable when urgency was collapsed into “urgency” and “no urgency” (Table S1,S2,S3).

Corticosteroid Prescription, Hospitalization, and Colectomy

We investigated the association between urgency and hospitalization, colectomy, and corticosteroid prescriptions within a 12-month window in the longitudinal cohort (Table 5). There were 145 total hospitalizations, 176 interval corticosteroid use outcomes, and 78 colectomies observed.

Table 5:

Baseline characteristics of patients with UC followed prospectively for hospitalization status based on level of urgency

| Characteristic | No Hurry N = 715 |

Hurry N = 919 |

Immediately N = 213 |

Incontinence N = 27 |

p-value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % or mean (SD) | N | % or mean (SD) | N | % or mean (SD) | N | % or mean (SD) | ||

|

Total follow up time

in days |

715 | 947(773) | 919 | 890(736) | 213 | 728(682) | 27 | 692(608) | 0.001 |

| Age | 715 | 45(14) | 919 | 44(15) | 213 | 46(15) | 27 | 45(11) | 0.4 |

| Body mass index | 715 | 25(4.8) | 919 | 25.8(6.2) | 213 | 26.4(6.4) | 27 | 26.8(6.3) | 0.003 |

| Sex | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Female | 463 | 65 | 668 | 73 | 158 | 74 | 25 | 93 | |

| Male | 252 | 35 | 251 | 27 | 55 | 26 | 2 | 7 | |

| Ever hospitalized | 429 | 60 | 591 | 64 | 141 | 66 | 19 | 70 | 0.2 |

| Stool frequency ¶ | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Normal | 76 | 85 | 42 | 41 | 3 | 12 | 1 | 33 | |

| 1-2 stools per day above normal | 13 | 15 | 41 | 40 | 4 | 16 | 1 | 33 | |

| 3-4 stools per day above normal | 0 | 0 | 14 | 14 | 10 | 40 | 1 | 33 | |

| 5+ stools per day above normal | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 32 | 0 | 0 | |

| Rectal bleeding | <0.001 | ||||||||

| No blood | 610 | 85 | 555 | 60 | 70 | 33 | 9 | 33 | |

| A little blood | 96 | 13 | 295 | 32 | 82 | 38 | 11 | 41 | |

| Occasionally a lot of blood | 6 | 1 | 49 | 5 | 34 | 16 | 4 | 15 | |

| Usually a lot of blood | 3 | 0 | 20 | 2 | 27 | 13 | 3 | 11 | |

| Current biologic use | 176 | 25 | 247 | 27 | 52 | 25 | 5 | 19 | 0.6 |

| Hospitalization(outcome) | 13 | 2 | 20 | 2 | 11 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 0.061 |

One-way ANOVA; Pearson’s Chi-squared test

Limited sample size for stool frequency since variable only collected after 2017

UC= ulcerative colitis, SD=standard deviation

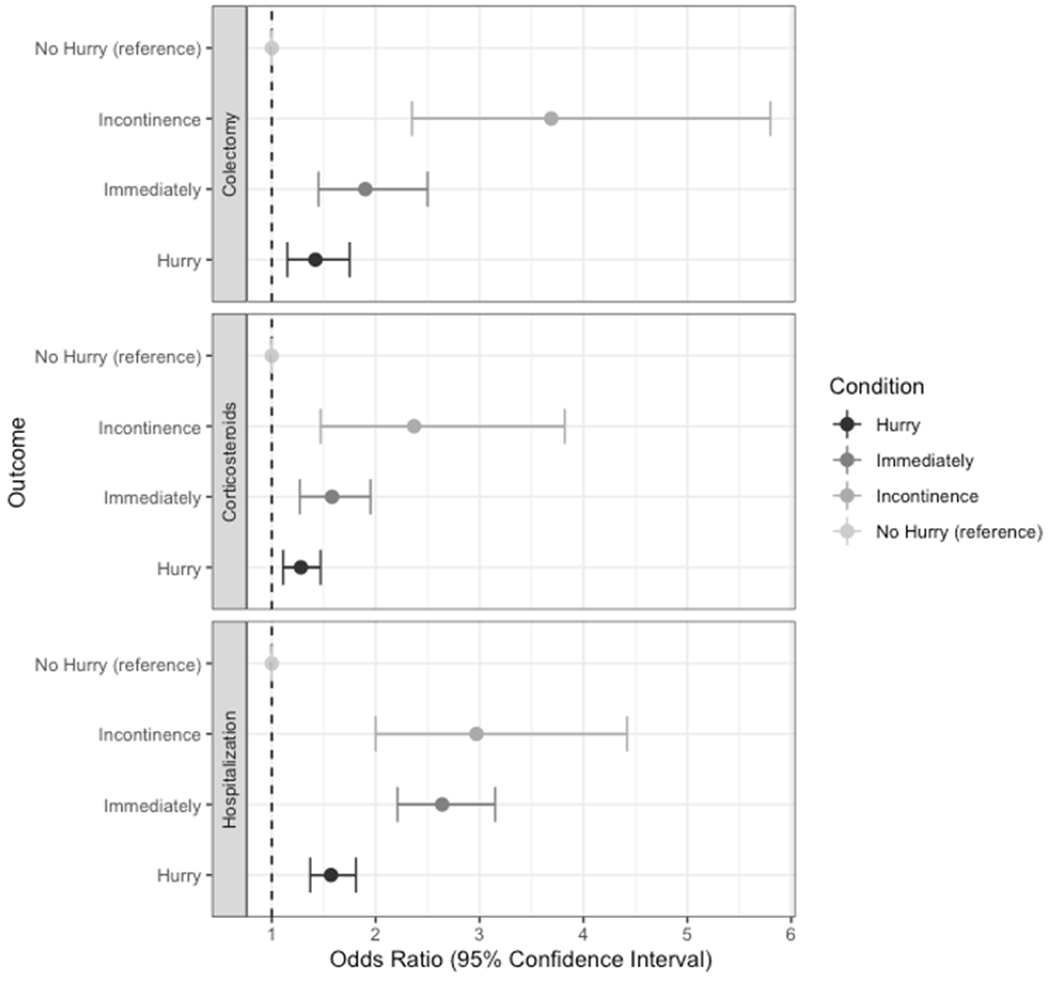

In the multivariate pooled logistic regression adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and biologic use, there was a significant association between increasing levels of urgency and higher risk of all outcomes within a 12-month period (Table 6, Figure 1). Patients who reported “hurry” had increased odds of hospitalization within 12 months (OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.37-1.81) in addition to patients reporting urgency level “immediately” (OR 2.64, 95% CI 2.21-3.15) and “incontinence” (OR 2.97, 95% CI 2.00 -4.42).

Table 6:

12-month risk of hospitalization, corticosteroids, and colectomy based on level on urgency in UC patients followed longitudinally

| Clinical Outcome | Odds ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization | ||

| No hurry (reference) | — | — |

| Hurry | 1.57 | 1.37, 1.81 |

| Immediately | 2.64 | 2.21, 3.15 |

| Incontinence | 2.97 | 2.00, 4.42 |

| Biologic Use | 1.21 | 1.08,1.36 |

| Female Sex | 0.93 | 0.82,1.06 |

| Age | 0.98 | 0.98,0.99 |

| Body mass index | 0.99 | 0.98,1.00 |

| Corticosteroids | ||

| No hurry (reference) | — | — |

| Hurry | 1.28 | 1.11, 1.47 |

| Immediately | 1.58 | 1.27, 1.95 |

| Incontinence | 2.37 | 1.47, 3.82 |

| Biologic Use | 0.97 | 0.85,1.11 |

| Female Sex | 1.01 | 0.87,1.17 |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.99,1.00 |

| Body mass index | 1.00 | 0.99,1.01 |

| Colectomy | ||

| No hurry (reference) | — | — |

| Hurry | 1.42 | 1.15,1.75 |

| Immediately | 1.90 | 1.45,2.50 |

| Incontinence | 3.69 | 2.35,5.80 |

| Biologic Use | 1.38 | 1.16,1.64 |

| Female Sex | 0.80 | 0.66,0.96 |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.99,1.00 |

| Body mass index | 1.00 | 0.98,1.01 |

| Full logistic regression model variables are listed in table above | ||

Hospitalization: UC-related hospitalization, Corticosteroids: new reported corticosteroid use, Colectomy: interval report of colectomy, all clinical events within 12 months of symptom report

UC= ulcerative colitis, CI= confidence interval

Figure 1. Longitudinal outcomes associated with baseline level of urgency among patients in IBD Partners with ulcerative colitis.

Colectomy: interval report of colectomy per patient; Corticosteroids: interval reported corticosteroid use; Hospitalization: interval UC-related hospitalization; all clinical events within 12 months of symptom report

Patients reporting “hurry” also had increased odds of corticosteroid prescription within 12 months (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.11 -1.47), as well as patients with urgency level “immediately” (OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.27 -1.95) and “incontinence (OR 2.37, 95% CI 1.47 -3.82).

Finally, urgency level of “hurry” was associated with a greater odds of colectomy within 12 months (OR 1.42 95% CI 1.15 -1.75) while patients with urgency level of “immediately” (1.90 95% CI 1.45 -2.50) and “incontinence” (OR 3.69 95% CI 2.35-5.80) also had higher risk of surgery.

When urgency was collapsed into “urgency” and no “urgency”, urgency was associated with an increased risk of hospitalizations (OR 1.78 95% CI 1.22-1.66), corticosteroids (OR 1.34 95% CI 1.17-1.53), and colectomy (OR 1.55 95% CI 1.28-1.89) (Table S4).

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional analysis paired with a longitudinal cohort using a patient-powered research network, we demonstrated that urgency was associated with a worse quality of life in multiple domains as well as an increased risk for hospitalizations, corticosteroid use, and colectomy over a 12-month follow-up period. We found that urgency is independently associated with a higher risk of depression, anxiety, fatigue, pain, and social impairment. Notably, urgency was associated with impaired social life, with a stronger association with each progressive degree of urgency from “hurry” to “incontinence”. In our multivariate longitudinal analysis, all degrees of bowel urgency were separately associated with a progressive 12-month risk of hospitalizations, corticosteroid use, and colectomy.

Recently, there has been a push to focus predominately on stool frequency and rectal bleeding as UC-PROs, while urgency has become progressively overlooked[15]. Urgency is a taboo topic for patients to discuss, with up to a third of UC patients embarrassed to address this issue with their provider[2]. However, UC patients prioritize resolution of urgency to a higher degree than diarrhea, abdominal pain, or rectal bleeding[16]. Patients’ immediate concerns are often focused on the resolution of symptoms compromising QoL, rather than endoscopic or histologic healing. This is perhaps not surprising given that urgency may significantly impair a patient’s ability to travel, attend events, and leave the house without knowledge of the closest bathroom. In the current study, we found that urgency was more highly associated with depression, anxiety, and social impairment than either stool frequency or rectal bleeding.

The recent STRIDE II guidelines have positioned clinical remission as the most important short-term goal in the induction of UC. Frequently utilized UC PRO’s in the US include the partial Mayo score and PRO-2 , both of which utilize two-question measures of stool frequency and rectal bleeding[15]. The PRO-2 was formulated from existing indices as an interim measure and has not undergone rigorous psychometric validation[7]; however, it has been associated with endoscopic and histologic features in UC[16]. The partial Mayo score is currently the most frequently used PRO measure in UC clinical trials. It remains unclear if excluding urgency from these PRO’s will inhibit the ability to capture key QoL measures or risk of future disease-related outcomes.

Recently, urgency has been incorporated as an outcome measure in ongoing UC clinical trials. In the phase II upadacitinib trial, bowel urgency and QoL, measured by inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (IBDQ) and SF-36, were assessed. Urgency correlated with disease activity, biomarkers, and QoL with improvements in urgency paralleling clinical response and remission [17,18]. Specifically, an absence of urgency was associated with Mayo endoscopic remission, histologic remission, and mucosal healing with an OR of 3.6 (95% CI 1.8-7.2), 4.6 (95% CI 2.4-8), and 4.9 (95% CI 2.1-11.6) respectively at week 12 [19]. The phase II trial of mirikizumab demonstrated reduced bowel urgency at week 12 persisting to week 52 in patients receiving drug compared to placebo[20]. Our study provides further evidence for the importance of bowel urgency as a target outcome in clinical trials, as bowel urgency clearly reflects integral QoL parameters and risk of clinical decompensation.

There are a paucity of data associating UC-specific PRO’s and risk of future clinical outcomes. Traditionally, objective measures of disease activity such as biomarkers and endoscopic indices have be used to predict future disease activity[21]. However, there has been a push to incorporate both patient-reported outcomes and objective disease measures to gauge risk of clinical decompensation. For example, a post-hoc analysis of GEMINI 1 revealed that patients without rectal bleeding at week 14 had higher rates of sustained remission at one year [22]. We demonstrate that increasing degrees of bowel urgency are significantly associated with future risk of hospitalization, steroid prescription, and colectomy within a year from time of symptom report.

There are a number of strengths to this cohort, including the large sample size, prospective data collection, and PRO information directly from patients. Multiple covariates within the surveys permitted a robust multivariate analysis of urgency and QoL. The main limitations of the study were that all outcomes were self-reported and thus corticosteroid use, hospitalizations, and colectomies could not be confirmed by medical record. Greater than 97% of IBD Partners participants were found to have physician-confirmed IBD; however, patient-reported UC disease location was omitted in our analysis due to only 54% agreement with physician assessment [23]. Disease severity could not be directly assessed due to lack of laboratory and endoscopic data. Bowel urgency can also be related to functional gastrointestinal disease or gynecologic history, neither of which were assessed in this cohort. The self-enrolled online format of the surveys selects for a technologically-literate, and predominately white population of high socioeconomic status, which potentially decreases external generalizability.

In conclusion, we sought to better understand the specific association between the symptom of urgency in UC with both QoL domains and the longitudinal clinical outcomes of hospitalizations, corticosteroids, and colectomy. We found that urgency is associated with depression, anxiety, and social impairment independent of rectal bleeding and stool frequency. We also revealed that increasing levels of urgency are associated with an increased risk of hospitalization, corticosteroid prescriptions, and colectomy. This study underscores the importance of physicians to address not only stool frequency and rectal bleeding, but also urgency. Our findings support the consideration of urgency as a UC-specific PRO and its use as an outcome in clinical trials to capture QoL and risk of clinical decompensation.

Supplementary Material

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS KNOWN

Bowel urgency compromises quality of life in ulcerative colitis patients

Widely used short patient reported outcomes (Mayo, PRO-2) for ulcerative colitis do not include urgency

WHAT IS NEW HERE

Urgency independently increases risk of social impairment, depression, anxiety, and fatigue in ulcerative colitis patients

Urgency in ulcerative colitis patients increases risk of future corticosteroids, hospitalizations, and colectomy

Financial Support:

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, Jared Sninsky MD supported by the T32 DK007634

Potential Competing Interests:

MDL: Consulting from AbbVie, BMS, Calibr, Genentech, Gilead, Janssen, Lilly, Pfizer, Prometheus, Roche, Salix, Takeda, Target Pharmasolutions, UCB, Valeant, Genentech, Theravance, Research support Takeda, Pfizer

EB: Consulting for AbbVie, Gilead, Pfizer, Takeda and Target RWE.

XZ: No disclosures

JS: No disclosures

Abbreviations:

- PRO

patient reported outcome

- PROMIS

Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System

- QoL

quality of life

- UC

ulcerative colitis

REFERENCES

- 1.Rao SS, Holdsworth CD, Read NW. Symptoms and stool patterns in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut 1988;29(3):342 doi: 10.1136/gut.29.3.342[published Online First: Epub Date]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hibi T, Ishibashi T, Ikenoue Y, Yoshihara R, Nihei A, Kobayashi T. Ulcerative Colitis: Disease Burden, Impact on Daily Life, and Reluctance to Consult Medical Professionals: Results from a Japanese Internet Survey. Inflammatory Intestinal Diseases 2020;5(1):27–35 doi: 10.1159/000505092[published Online First: Epub Date]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasmussen B, Haastrup P, Wehberg S, Kjeldsen J, Waldorff FB. Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with moderate to severely active ulcerative colitis receiving biological therapy. Scand J Gastroenterol 2020;55(6):656–63 doi: 10.1080/00365521.2020.1768282[published Online First: Epub Date]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanauer SB, Present DH, Rubin DT. Emerging issues in ulcerative colitis and ulcerative proctitis: individualizing treatment to maximize outcomes. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2009;5(6 Suppl):4–16 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE, Allan RN. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut 1998;43(1):29–32 doi: 10.1136/gut.43.1.29[published Online First: Epub Date]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bewtra M, Brensinger CM, Tomov VT, et al. An optimized patient-reported ulcerative colitis disease activity measure derived from the Mayo score and the simple clinical colitis activity index. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20(6):1070–8 doi: 10.1097/mib.0000000000000053[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jairath V, Khanna R, Zou G, et al. Development of interim patient-reported outcome measures for the assessment of ulcerative colitis disease activity in clinical trials. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 2015;42 doi: 10.1111/apt.13408[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis JD, Chuai S, Nessel L, Lichtenstein GR, Aberra FN, Ellenberg JH. Use of the noninvasive components of the Mayo score to assess clinical response in ulcerative colitis. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2008;14(12):1660–66 doi: 10.1002/ibd.20520[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Long MD, Kappelman MD, Martin CF, et al. Development of an internet-based cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (CCFA Partners): methodology and initial results. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18(11):2099–106 doi: 10.1002/ibd.22895[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beleckas CM, Gerull W, Wright M, Guattery J, Calfee RP. Variability of PROMIS Scores Across Hand Conditions. J Hand Surg Am 2019;44(3):186–91.e1 doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2018.10.029[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDermott MM, Spring B, Berger JS, et al. Effect of a Home-Based Exercise Intervention of Wearable Technology and Telephone Coaching on Walking Performance in Peripheral Artery Disease: The HONOR Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018;319(16):1665–76 doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3275[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canetta PA, Troost JP, Mahoney S, et al. Health-related quality of life in glomerular disease. Kidney Int 2019;95(5):1209–24 doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.12.018[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain A, Nguyen NH, Proudfoot JA, et al. Impact of Obesity on Disease Activity and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. The American journal of gastroenterology 2019;114(4):630–39 doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000197[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kappelman MD, Long MD, Martin C, et al. Evaluation of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system in a large cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association 2014;12(8):1315-23.e2 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.10.019[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, et al. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2021;160(5):1570–83 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.031[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dragasevic S, Sokic-Milutinovic A, Stojkovic Lalosevic M, et al. Correlation of Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO-2) with Endoscopic and Histological Features in Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease Patients. Gastroenterology Research and Practice 2020;2020:2065383 doi: 10.1155/2020/2065383[published Online First: Epub Date]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh S, Louis E, Loftus EV Jr, et al. P283 Bowel urgency in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis: prevalence and correlation with clinical outcomes, biomarker levels, and health-related quality of life from U-ACHIEVE, a Phase 2b study of upadacitinib. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 2019;13(Supplement_1):S240–S41 doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy222.407[published Online First: Epub Date]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghosh S, Sanchez Gonzalez Y, Zhou W, et al. Upadacitinib Treatment Improves Symptoms of Bowel Urgency and Abdominal Pain, and Correlates With Quality of Life Improvements in Patients With Moderate to Severe Ulcerative Colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2021. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab099[published Online First: Epub Date]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubinsky MC, Panaccione R, Lewis J, et al. S0683 Absence of Bowel Urgency Is Associated With Improvements in Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis Receiving Mirikizumab. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology | ACG 2020;115 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dubinsky M, Lee SD, Panaccione R, et al. P068 MIRIKIZUMAB TREATMENT IMPROVES BOWEL MOVEMENT URGENCY IN PATIENTS WITH MODERATELY TO SEVERELY ACTIVE ULCERATIVE COLITIS. Gastroenterology 2020;158(3):S17–S18 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.11.074[published Online First: Epub Date]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins PDR. The Development of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2018;14(11):658–61 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feagan BG, Schreiber S, Wolf DC, et al. Sustained Clinical Remission With Vedolizumab in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2019;25(6):1028–35 doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy323[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Randell RL, Long MD, Cook SF, et al. Validation of an internet-based cohort of inflammatory bowel disease (CCFA partners). Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20(3):541–4 doi: 10.1097/01.Mib.0000441348.32570.34[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.