Abstract

Issues:

Non-medical prescription opioid use (NMPOU) contributes substantially to the global burden of morbidity. However, no systematic assessment of the scientific literature on the associations between NMPOU and health outcomes has yet been undertaken.

Approach:

We undertook a systematic review evaluating health outcomes related to NMPOU based on ICD-10 clinical domains. We searched 13 electronic databases for original research articles until 1 July 2021. We employed an adaptation of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine ‘Levels of Evidence’ scale to assess study quality.

Key Findings:

Overall, 182 studies were included. The evidence base was largest on the association between NMPOU and mental and behavioural disorders; 71% (129) studies reported on these outcomes. Less evidence exists on the association of NMPOU with infectious disease outcomes (26; 14%), and on external causes of morbidity and mortality, with 13 (7%) studies assessing its association with intentional self-harm and 1 study assessing its association with assault (<1%).

Implications:

A large body of evidence has identified associations between NMPOU and opioid use disorder as well as on fatal and non-fatal overdose. We found equivocal evidence on the association between NMPOU and the acquisition of HIV, hepatitis C and other infectious diseases. We identified weak evidence regarding the potential association between NMPOU and intentional self-harm, suicidal ideation and assault.

Discussion and Conclusions:

Findings may inform the prevention of harms associated with NMPOU, though higher quality research is needed to characterise the association between NMPOU and the full spectrum of physical and mental health disorders.

Keywords: prescription drugs, opioid overdose, health outcomes, non-medical, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

The use of naturally-occurring, synthetic and semisynthetic opioids is common worldwide, with methadone, morphine and fentanyl all included on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines [1]. Strong evidence suggests that opioids are effective in the treatment of acute and cancer-related pain [2], though little evidence their use for chronic non-cancer pain exists, particularly in the long-term [3]. Nevertheless, rates of opioid prescribing increased precipitously in the United States and Canada over the past two decades [4,5]. In the United States and Canada, the increased availability of prescription opioids has contributed to a high prevalence of non-medical use: in 2015, for example, 12.5 million people in the United States engaged in non-medical prescription opioid use (NMPOU) amounting to 4.7% of the population [6]. This is of concern given that NMPOU is a primary driver of the opioid overdose epidemic affecting North America [5,7].

To date, efforts to respond to and reduce the health impacts of NMPOU have focused largely on its contribution to overdose risk [8]. However, the range of health harms associated with NMPOU remain poorly synthesized (e.g. only one scoping review on the topic exists [9]), despite a large evidence base spanning multiple scientific and clinical disciplines. This is of public health and public policy concern, given that clinicians, implementation scientists and policymakers require a comprehensive assessment of potential harms to inform clinical practice, interventions and policy responses.

We therefore conducted a systematic review of the scientific literature to assess the known associations between NMPOU and a range of clinical outcomes.

METHODS

We used Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [10]. We searched electronic literature databases, listed in Table S1 (Supporting Information), for articles published as of 1 October 2018. We defined NMPOU as: use in the context of someone else’s prescription or the use of one’s own prescription outside of prescribed parameters (i.e. dose, frequency, mode of consumption or indication) [11]. We used International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) for physical and mental health disorders potentially associated with NMPOU, using relevant Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords (see Table S1). Table 1 lists ICD-10 codes potentially associated with non-medical prescription opioid use. Hand searching of relevant academic meetings and reference lists was also done. All searches were conducted between 24 October 2015 and 15 October 2018.

Table 1.

International Classification of Diseases–10th revision codes potentially associated with non-medical prescription opioid use

| I. Infectious diseases |

| B15 – B19: Viral hepatitis |

| B20 – B24: Human Immunodeficiency Virus [HIV] |

| III. Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism |

| D65 – D69: Coagulation defects, purpura and other hemorrhagic conditions |

| V. Mental and behavioral disorders |

| F10 – F19: Mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use |

| F30 – F39: Mood [affective] disorders |

| F40 - F48: Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders |

| F00 – F99: Other psychiatric / mental health measures |

| XI. Diseases of skin and subcutaneous tissue |

| L00 – L99: Infections of the skin and subcutaneous tissue |

| XVI. Certain conditions originating in the perinatal period |

| P05 – P08: Disorders related to length of gestation and fetal growth |

| P90 – P96: Other disorders originating in the perinatal period |

| XVIII. Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings not elsewhere classified |

| R40-R46. Symptoms and signs involving cognition, perception, emotional state and behavior |

| R50-R69: General symptoms and signs |

| XIX. Injury, poisoning, and certain other consequences of external causes |

| T36 – T50: Poisoning by drugs, medicaments, and biological substances |

| XX. External causes of morbidity and mortality |

| X60-X64: Intentional self-harm |

| X85-Y09: Assault |

Eligible studies were: (i) peer-reviewed; (ii) measured current or past NMPOU; and (ii) were a randomised control trial, case-control, comparison study, cohort study, non-randomised trial, quasi-experimental study, time-series analysis or ecological study. Studies were excluded if they failed to isolate NMPOU, did not capture ICD-10 outcomes and were not written in English. Two of four investigators independently reviewed titles and abstracts in stage 1, and full texts in stage 2, classifying studies as “potentially relevant” or “irrelevant”. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

We employed the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine ‘Levels of Evidence’ [12] to assess the contribution of each study to the scientific evidence base. The ‘Levels of Evidence’ tool provides a rank based on study design, with studies designed to provide a higher level of evidence ranked lower (i.e. the highest rank is 1; the lowest is 5). For the current study, we adapted the tool to range from 1 to 4; this was done given that studies with the lowest level of evidence based on the tool (ranked at 5, and consisting of non-data driven expert opinion) were not eligible for inclusion in the systematic review because they did not present data. Two investigators independently scored studies, with a third author verifying, and consensus achieved where needed by a fourth author. Assessments of the level of evidence within the 1-4 range were not a basis for exclusion.

RESULTS

Study selection and characteristics

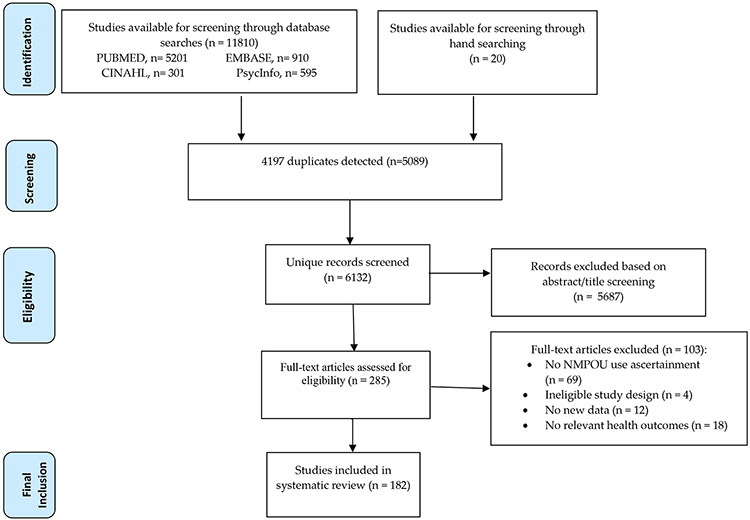

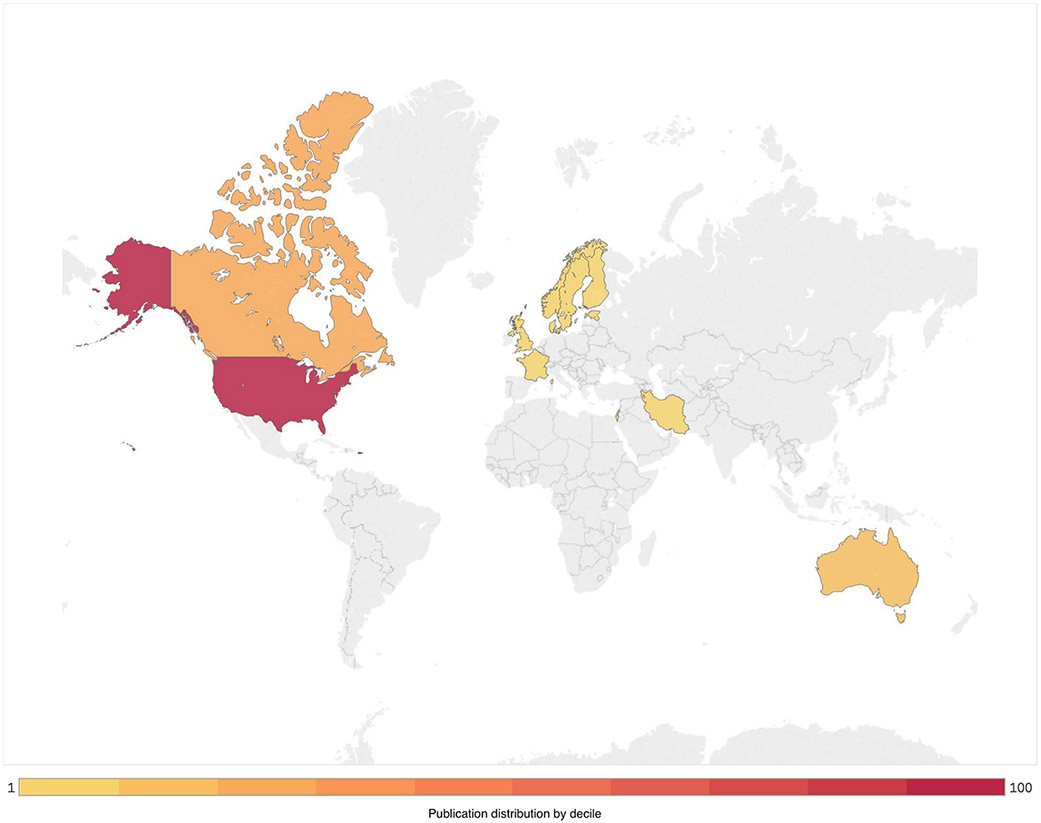

Overall, as shown in Figure 1, 11,810 studies were identified, yielding 285 full text articles assessed for eligibility, with 103 excluded. Ultimately, 182 studies met the inclusion criteria; three studies only included event count and not participant sample size [13-15]. A total of 53 (29%) studies employed cross-sectional, population-based and nationally representative observational designs [7,14,16-64]; 13 (7%) employed longitudinal, cohort-based observational designs [65-77]; 4 (2%) employed case control designs [78-81]; 6 (3%) were randomised control trials [82-87]; 54 (30%) employed cross-sectional data from convenience samples [73,88-140]; 10 (5%) employed longitudinal (including repeated cross-sectional) data from nationally representative studies [15,17,141-147]; and 42 (23%) retrospectively assessed individual-level data [13,37,148-187]. As shown in Figure 2, the majority of studies presented data from the USA (126, 69%). Other countries represented included Canada (22, 12%), Australia (13, 7%), France (4, 2%), India (4, 2%), Nordic countries (4, 2%), China (3, 2), the United Kingdom (2, 1%), Estonia (1, <1%), Iran (1, <1%) and Israel (1, <1%).

Figure 1:

PRISMA flow chart of study selection. NMPOU, non-medical prescription opioid use.

Figure 2:

Distribution of publications on clinical outcomes associated with non-medical prescription opioid use

Levels of evidence assessment

The mean assessment score was 3.30 (SD = 1.01; interquartile range = 2-4), reflecting that the studies included in the systematic review generally used designs that provided a lower level of evidence. Seven studies (4%) received a score of 1 (the highest score); 53 (29%) received a score of 2; 7 (4%) received a score of 3; and 115 (63%) received a score of 4 (the lowest score). We detected no significant association between study quality and year of publication (R2 = > −0.01, P > 0.05), suggesting no significant change in quality over time.

Results of individual studies

Table 2 presents results from all eligible studies classified by ICD-10 code. As can be seen, studies investigated the association between NMPOU and outcomes across eight major clinical domains. The median number of studies investigating each clinical outcome was 15.0 (interquartile range 3.0-23.5).

Table 2.

Summary of 182 studies examining health outcomes of non-medical prescription opioid use, sorted by World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases (ICD 10) code [V. 2016]

| Study | Study design | Participant characteristics | NMPOU exposure | Study rank |

Outcome measure | Main finding and quantitative results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

I. Infectious and parasitic diseases

B15 – B19: Viral hepatitis [Hepatitis B] | ||||||

| Havens 2007, USA | Cross-sectional | 184 prescription opioid [PO] users recruited through street outreach and snowball sampling; median age: 30 years | Injection in past 30 days | 4 | HBV [self-reported] | There was no significant difference in HBV infection between those who inject PO and those who did not (P=0.184). |

| Wylie 2006, Canada | Cross-sectional 2003-2004 | 369 PWID recruited through street outreach | Injection in past 6 months 6 months | 4 | HBV serostatus [IMX HBV core IgG] | Morphine injection was not significantly associated with HBV serostatus (OR=1.2 [0.7–1.8]); overall HBV prevalence was 30%. |

| B15 – B19: Viral hepatitis [Hepatitis C] | ||||||

| Aitken 2008, Australia | Cross-sectional 2005-2006 | 316 street-recruited PWID | Injection drug use in previous 3 months | 4 | HCV serostatus | There was no significant difference between buprenorphine injectors and non-injectors in prevalence of HCV antibody (OR=1.2 [0.5-3.0]) or ribonucleic acid (OR=0.95 [0.4-2.1]). |

| Barry 2011, USA | Cross-sectional 2006 | 4122 veterans in the third wave of a follow-up survey, median age: 52 years | Past-year use of NMPOU | 4 | HCV | Veterans in care have a high prevalence of NMPOU which was associated with hepatitis C (AOR=1.5 [1.2-1.9]); HCV prevalence: 56.8% |

| Bruneau 2012, Canada | Prospective 2004-2009 | 246 HCV-negative PWID at baseline; mean age: 34.5 years | Past month injection drug use | 2 | HCV infection [EIA test] | Compared to non-PO injectors, PO injectors were more likely to become infected with HCV (aHR 1.87 [1.16-3.03]). |

| Chelleng 2008, India | Cross-sectional 2004-2005 | 143 PWIDs including female sex workers; median age: 24.7 years | Injection drug use in previous 6 months | 4 | HCV antibodies prevalence [ELISA] | Prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies was significantly lower among exclusive PO injectors compared to exclusive heroin injectors [n=13/31] vs 85.2% (41.9% [n=23/27]], p<0.05). |

| Das 2007, India | Cross-sectional | 254 PWIDs randomly sampled and enrolled; median age: 26 years | Injection drug use in previous 6 months | 4 | HCV serostatus [EIA] | Prevalence of HCV significantly lower among exclusive PO injectors compared to exclusive heroin injectors (23.9% [n=27/113] vs 45.4% [5/11], P <0.05). |

| Hadland 2014, Canada | Prospective 2005-2011 | 940 adolescents and young adults aged 14–26 recruited through street-based outreach and snowball sampling; mean age: 21.7 years | Substance use in past 6 months (injecting, non-injecting) | 2 | HCV serostatus and seroconversion | PO injection was significantly and positively associated with HCV serostatus at baseline (OR=8.69 [5.01-15.1]), after covariate adjustment PO injection was not positively associated with HCV seroconversion (aHR=0.94 [0.40-2.21]) |

| Han 2017, USA | Cross-sectional 2015 | 51200 respondents in the 2015 NSDUH identified as prescription opioid users | Lifetime and past-year NMPOU | 4 | HBV or HCV | Among adults with prescription opioid misuse, prevalence of HBV or HCV was 12.4% (95% CI, 8.32-18.19) |

| Havens 2007, USA | Cross-sectional | 184 prescription opioid [PO] users recruited through street outreach and snowball sampling; median age: 30 years | PO injection in past 30 days | 4 | HCV [self-reported] | More people who inject PO self-reported HCV compared to those who did not inject PO, (n=9 [14.8%] vs. n=2 [1.7%], P <0.05) |

| Havens2013, USA | Cross-sectional 2008-2010 | 392 PWIDs recruited through street outreach median age: 31 years | Past month (any drug use), lifetime (injection) | 4 | HCV [home access test] | Injecting prescription opioids was significantly associated with HCV seropositivity (AOR=2.22 [1.13-4.35]); prevalence of HCV infection was 54.8% |

| Iversen 2010, Australia | Cross-sectional 1998-2008 | 15,852 PWID recruited from needle and syringe programs; mean age: 31 years | Number of years injecting NMPOU | 4 | HCV serostatus [EIA test] | For those injecting ≤ 4 years, injection of methadone or buprenorphine (female: AOR=4.78 [2.63-8.70]; male: AOR=3.06[1.58-5.92]), and injection of other prescription opioids (women: AOR=2.20 [1.24-3.90]; men: AOR=1.77 [1.03-3.04]), were associated with HCV positive serostatus |

| Lankenau 2015, USA | Cross-sectional 2009-2011 | 162 PWIDs sampled in New York and Los Angeles; mean age: 21.4 years | Lifetime NMPOU injection | 4 | HCV [self-reported] | Lifetime prescription opioid injectors were nearly 3 times more likely to report being HCV positive than non-prescription opioid injectors (AIRR=2.69 [1.07-6.78], P <0.05) |

| Mahanta 2009, India | Cross-sectional 2004-2006 | 398 PWIDs recruited from drop-in centres; median age: 26 years | Injection NMPOU in previous 6 months | 4 | HCV serostatus [EIA] | Proxyvon-only injection was associated with reduced odds of HCV infection (AOR=0.42 [0.24-0.71] |

| Patra 2009, Canada | Prospective 2004-2005 | 582 participants from the most recent follow-up in the OPICAN study; mean age:35.2 years | NMPOU use in past 30 days | 4 | HCV [self-reported] | Among participants who primarily used prescription opioids, risk of HCV positivity was low (OR=0.35 [0.12-1.01]); self-reported HCV prevalence was 24% |

| Powell 2019, USA | Ecological 2004-2015 | 50 US states | Past-year median OxyContin misuse rate | 2 | HCV incidence rate | States with above-median OxyContin misuse before the reformulation experienced a 222% increase in HCV infection rates vs. 75% increase in states with below-median OxyContin misuse |

| Wylie 2006, Canada | Cross-sectional 2003-2004 | 369 PWID recruited through street outreach | Injection NMPOU in previous 6 months | 4 | HCV serostatus [AxSYM HCV] | Morphine injection was not significantly associated with HCV serostatus (OR=1.2 [0.8-1.9]); overall HCV prevalence was 53.7% |

| Zibbell 2014, USA | Cross-sectional 2012 | 123 PWID recruited using snowball sampling | Injection NMPOU in previous in past year | 4 | HCV serostatus [PCR] | Prescription opioid injection was significantly associated with HCV positivity (AOR=5.53 [1.92-15.91]) |

| B20 – B24: HIV | ||||||

| Barry 2011, USA | Cross-sectional 2006 | 4122 veterans in the third wave of a follow-up survey; median age 52 years | Past year NMPOU | 4 | HIV | Veterans in care have a high prevalence of NMPOU which was not associated with HIV status; HIV prevalence was 60% |

| Buttram 2014, USA | Clinical trial 2008-2010 | 515 MSM participating in a risk reduction intervention trial; mean age: 38.9 years | Past year and past 90 days injection NMPOU | 2 | HIV | Prescription opioid misuse in past 90 days was associated with lower odds of HIV-positive serostatus (OR=0.825 [0.553-1.232]); HIV seropositive prevalence: 48.5% |

| Black 2013, USA | Cross sectional 2007-2011 | 29,459 PO users recruited from 540 treatment facilities; mean age=33.1 years | Past 30 days NMPOU | 4 | HIV/AIDS prevalence [ASI-MV] | Prescription opioid injection was not significantly associated with increased odds of HIV/AIDS (OR=1.05 [0.73-1.51; 1.1% reported a positive HIV/AIDS test |

| Conrad 2015, USA | Cross-sectional | 135 HIV positive persons in a rural Indiana county; mean age: 35 years | Lifetime NMPOU injection | 4 | HIV | Among 135 persons with HIV infection, 80.0% are PWIDs and inject tablets of oxymorphone as their drug of choice |

| Novak 2016, Denmark, Germany, Great Britain, Sweden | Cross-sectional 2014 | 22070 survey respondents in the European Union ages 12-49 | Lifetime and past year NMPOU | 4 | HIV | NMPO users were more likely to be HIV positive (AOR=18.9 [10-34; P <0.001] that those not reporting NMPOU |

| Obadia 2001, France | Cross-sectional 1997 | 343 PWIDs recruited at 32 pharmacies, 4 needle exchange programs and 3 syringe vending machines; median age = 30 years | Injection NMPOU in previous 6 months | 4 | HIV | Compared to people who inject [self-reported] other drugs, buprenorphine-only injection was significantly associated with reduced odds of HIV (AOR=0.63 [0.41-0.94]) |

| Talu 2010, Estonia | Cross-sectional | 350 PWID recruited using respondent driven sampling mean age: 23.9 years | Injection NMPOU in past 28 days | 4 | HIV [HIV GACPAT] | Fentanyl injection was associated with increased risk of testing positive for HIV (AOR=2.89 [1.55-5.39]); HIV prevalence was 62% among fentanyl injectors (95% CI 56.97–67.03, P <0.001) |

| Wylie 2006, Canada | Cross-sectional 2003-2004 | 369 PWID recruited through street outreach | Injection NMPOU in previous 6 months | 4 | HIV serostatus [AxSYM HIV1/2 gO] | Morphine injection was not positively associated with HIV serostatus (OR=0.4 [0.1–1.1]); overall HCV prevalence was 7% |

|

III. Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism

D65 – D69: Coagulation defects, purpura and other haemorrhagic conditions | ||||||

| CDC 2013, USA | Case-control | Cases: 15 patients with TTP-like illnesses, Controls:28 patients recruited from a methadone clinic; median age: cases= 34 years, controls= 31 years | Injection NMPOU in previous 6 months | 4 | TTP-like illness | The cases of TTP-like illness were associated with dissolving and injecting tablets of Opana-ER, a recently reformulated extended-release form of oxymorphone intended for oral administration; 14 of the 15 case-patients, reported recent injection of reformulated Opana-ER (OR= 35.0 [3.9–312.1]) |

|

V. Mental and behavioural disorders

F10 – F19: Mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use | ||||||

| Adams 2006, USA | Prospective | 11352 patients with chronic pain taking prescription opioids | Past year NMPOU | 2 | Withdrawal [withdrawal score] | Withdrawal score of hydrocodone was significantly higher than that of tramadol (P <0.01) |

| Back 2010, USA | Cross-sectional 2006 | 55,279 respondents in the NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Dependence [DSM IV criteria] | Among the respondents, 13.2% reported prescription opioid dependence |

| Back 2011, USA | Cross-sectional | 24 non-treatment seeking individuals (12 men and 12 women) | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Dependence [DSM-IV criteria] | All recruited participants had PO dependence. The most common NMPO was with oxycontin (56%) |

| Barry 2011, USA | Cross-sectional 2006 | 4122 veterans in the third wave of a follow-up up survey; median age: 52 years | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Opioid use disorder | Veterans in care have a high prevalence of NMPOU which is associated with opioid use disorder [AOR 2.7 (1.9-3.9)]; opioid use disorder prevalence: 30.7% |

| Becker 2007, USA | Cross-sectional 2002-2004 | 6879 respondents in the NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Dependence [DSM-IV criteria] | Of those with non-medical use, 12.9% met criteria for abuse or dependence |

| Becker 2011, USA | Retrospective 2006-2008 | 3238 respondents in the NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 2 | Dependence [self-reported] | Past-year opioid analgesic abuse and/or dependence was associated with having a physician source of opioids (AOR=2.0 [1.5-2.7]); 20.3 % of participants had PO abuse/dependence |

| Blanco 2016, USA | Prospective 2001-2005 | 34653 sample of US adults participating in NESARC | Past-year NMPOU | 1 | Opioid use disorder | Prospective association between pain at wave 1 predicting PO use disorder at wave 2 (AOR=2.17 [1.35-3.48]). Predicted risk of developing PO use disorder at wave 2 was 0.44% for persons without and 0.62% for those with pain interference at wave 1 (increase of 41%) |

| Blanco 2016, USA | Prospective 2001-2005 | 34653 sample of US adults participating in NESARC | Past year NMPOU | 1 | Opioid tolerance, withdrawal | Pain at wave 1 was significantly associated with opioid tolerance (β=0.17, P=0.002) and withdrawal (β=0.24, P <0.001) at wave 2; association approached significance for taking opioids longer or at greater doses than prescribed (β=0.12, P=0.07) |

| Boyd 2009, USA | Prospective 2001-2005 | 34653 sample of US adults participating in NESARC | Lifetime and past year NMPOU | 1 | Dependence [DSM-IV criteria] | Non-medical use (at young age) in Wave 1 was associated with higher odds of a general substance or opioid abuse/dependence disorder at Wave 2 (AOR=3.42, 95% CI 1.45, 8.07) |

| Buttram 2014, USA | Clinical trial 2008-2010 | 515 MSM participating in a risk reduction intervention trial; mean age: 38.9 years | Past year and past 90 days injection NMPOU | 2 | Dependence [DSM-IVR criteria] | Non-medical prescription opioid use was associated with higher odds of substance dependence (OR=2.150 [1.253-3.689]; P=0.005); substance dependence prevalence: 62.1% |

| Cohen 2010, Ireland | Cross-sectional | 89 service users attending an outpatient methadone stabilisation and detoxification program | Lifetime NMPOU | 4 | Dependence [MAP] | Those with any history of codeine misuse were more likely to have a longer drug dependence history (P <0.05) |

| Cottler 2016, USA | Retrospective cohort 1981-1983, 2007 | 9985 participants in population-based sample | NMPOU more than 5 times in life | 2 | Alcohol abuse/dependence | Prevalence of alcohol abuse or dependence was greater in non-medical prescription opioid users (56.9%) compared to non-PO drug users (23.1%) and non-drug users (9.0%) |

| Edlund 2007, USA | Cross-sectional 1996-1997 | 9279 participants from a nationally representative study of the US civilian population | NMPOU in past 12 months | 4 | Problem opioid misuse including tolerance and/or physiologic problems [CIDI] | Users of prescribed opioids had significantly higher rates of any opioid misuse (AOR = 3.07 [2.05-4.60], P < 0.001) and problem opioid misuse (AOR = 6.11 [3.02-12.36], P < 0.001) |

| Edlund 2010, USA | Cross-sectional 2001-2004 | 36,605 enrollees in HealthCore and 9651 enrollees in Arkansas Medicaid all receiving chronic opioid therapy | Past six month NMPOU | 4 | Dependence/abuse [ICD-9-CM] | Participants with a diagnosis of 2 or more mental health disorders prior to the period of opioid use episode had increased odds of dependence/abuse in the period following opioid use episode (HealthCore patients: AOR=2.08 [1.69-2.55]; Medicaid patients: AOR=1.70 [1.21-2.39]) |

| Edlund 2014, USA | Cross-sectional 2000-2005 | 568,640 individuals with new chronic non cancer pain episode being prescribed opioids | NMPOU in the 18 months after the index date | 4 | Opioid use disorder [ICD-9-CM] | Individuals with pre-index mental health disorders had higher rates of opioid use disorders (AOR=3.12 [2.41-4.04], P <0.001) |

| Ghandour 2008, USA | Cross-sectional 2002-2003 | 7810 respondents in the 2002-2003 NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Dependence [DSM-IV] | Among past year PO users, 8.3% met criteria for opioid dependence, also individuals belonging to the highest latent class had high probabilities of endorsing each of the seven symptoms of dependence (0.70–0.99) |

| Han 2017, USA | Cross-sectional 2015 | 51,200 respondents in the 2015 NSDUH identified as prescription opioid users | Lifetime and past year NMPOU | 4 | Opioid use | Among adults with prescription disorder opioid misuse, prevalence of past-year PO use disorder was 16.7% (95% CI 14.8-18.49) |

| Humeniuk 2003, Australia | Cross-sectional 1996-1997 | 365 heroin users recruited through snowball sampling; mean age: 28.9 years | Injection NMPOU in last 6 months | 4 | Dependence [SDS scale] | Participants injecting methadone were significantly more dependent on heroin than people not injecting methadone (mean SDS scores: 8.9 vs 6.39 [F=14.5, df=1, 362, P=0.000]) |

| Kouyanou 1997, London, UK | Cross-sectional | 125 patients receiving treatment for chronic pain; mean age: 41 years | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Dependence/abuse [DSM-III-R] | Among the sample of chronic pain sufferers, 3.2% and 4.8% met criteria for opioid abuse and dependence respectively |

| Martins 2007, USA | Cross-sectional 2002-2003 | 7810 respondents in the 2002-2003 NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Withdrawal [self-reported], Tolerance [self-reported] | Prescription opioid dependence was significantly associated with withdrawal symptoms (AOR=3.76 [2.88-4.91]) and tolerance [AOR=9.90 [7.70-12.74]) |

| McCabe 2016, USA | Longitudinal observational 1993-2013 | 4072 high school seniors | Past year and past month NMPOU | 2 | SUD at age 35 | Medical use of PO without misuse during adolescence was not associated with SUD symptoms at age, while NMPOU was (AOR=2.61 [1.88-3.61]), compared to no medical or nonmedical use |

| McCabe 2012, USA | Cross-sectional 2009-2010 | 148 middle and high school students reporting past year NMPOU; mean age: 15.2 years | Past year NMPOU | 4 | SUD [CRAFT] | Among past year NMPO users, 35.1% screened positive for SUD based on the craft test |

| Miller 2004, USA | Retrospective 2000 | 534 patients admitted and discharged from an addiction detoxification unit; mean age: 40.37 years | Current NMPOU | 2 | Substance-related diagnosis [DSM criteria] | Users of NMPOs had a higher mean number of substance-related diagnosis than non-users, also opiate dependent patients were more likely to have a medical diagnosis (OR = 3.47 [2.00-5.99]) |

| Morasco 2008, USA | Randomised trial 2006-2007 | 127 patients recruited from a veteran’s affairs medical centre; mean age: 59.8 years | Lifetime NMPOU | 1 | SUD [ICD-9-CM] | Borrowing pain medication (misuse) was significantly associated with increased odds of SUD (AOR=6.62 [1.4-30.7]) |

| Morasco 2013, USA | Cross-sectional | 80 participants with chronic pain recruited from a veteran’s affairs medical centre; mean age: 54.9 years | Current opioid prescription and composite NMPOU risk measure | 4 | SUD [SCID] | Participants in the high prescription opioid misuse group had the highest rates of current substance use disorders (32% vs 20% and 0, P=0.009) |

| Morizio 2017, USA | Retrospective cohort study 2010-2015 | 923 patients admitted to a medical centre for heroin or non-heroin opioid overdose event; median age: 24 | Lifetime history of NMPOU | 2 | History of prescription opioid abuse | History of NMPOU was more prevalent among those with non-heroin opioid overdose (46.9%), compared to the heroin overdose group (21.9%), P <0.0001 |

| Reid 2002, USA | Retrospective 1997-1998 | Medical records of 50 veteran affairs and 48 primary care centre patients; veteran affairs patients median age: 54 years; primary care centre patients median age: 55 years | Lifetime history of NMPOU based on patient records | 2 | Substance use | Prescription opioid abuse was disorder [medical associated with a lifetime history records review] of substance use disorder (AOR=3.8 [1.4-10.8]) |

| Romach 1999, Canada | Cross-sectional | 339 long term codeine users recruited through newspaper adverts; mean age: 44 years | Past year codeine use | 4 | Dependence [DSM-IV] | Codeine dependence/abuse was present in 41% of long-term codeine users |

| Roux 2011, France | Prospective 1995-1996 | 235 HIV-infected opioid-dependent individuals; median age: 34 years | Injecting or sniffing PO in the previous 6 months | 2 | Withdrawal symptoms [self-report] | NMPOU was significantly associated with a reduced odds of experiencing opioid withdrawal symptoms (AOR=0.62 [0.36-0.89]) |

| Saha 2016, USA | Cross-sectional 2012-2013 | 36,309 respondents in the NESARC-III | Past-year and lifetime NMPOU | 4 | Any other substance use disorders | NMPOU was significantly related to having any other substance use disorder (12-month AOR=2.95 [2.54-3.44]; lifetime AOR = 3.07 [2.67-3.53]) |

| Schepis 2019, USA | Cross-sectional 2012-2013 | 14667 respondents in the NESARC-III | Persistent NMPOU (defined as past-year and prior) | 4 | Past-year substance use disorders | Persistent NMPOU significantly associated with higher past year prevalence of any substance use disorder (56.3% vs. 20.5%), alcohol use disorder (41.0% vs. 19.3%), and tobacco use disorder (48.4% vs. 24.6%) vs. no NMPOU |

| Schepis 2019, USA | Cross-sectional 2015-2016 | 114,043 respondents in the NSDUH | Past-year non-medical prescription fentanyl use | 3 | Past-year non-alcohol substance use disorders | Past-year non-medical prescription fentanyl use was associated with past-year non-alcohol substance use disorders (RR=20.64 [9.38-45.45]) compared to population controls |

| Schepis 2019, USA | Cross-sectional 2009-2014 | 103,920 adolescent respondents in in the NSDUH | Past 30 days NMPOU | 4 | Major depression in past year (DSM-IV) | NMPOU was significantly associated with major depression (AOR=1.91 [1.21-3.01]) |

| Wu 2008, USA | Cross-sectional 2005-2006 | 2675 adolescent participants in the 2005-2006 NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Dependence [DSM-IV] | Among adolescents age 12 to 17, weekly use of NMPO was significantly associated with dependence (AOR=5.45 [3.97-7.49]) |

| Wu 2009, USA | Cross-sectional 2006 | 1290 adolescent participants in the 2006 NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Dependence [DSM-IV] | Among adolescents age 12 to 17, 15.1% met DSM-IV criteria either for opioid abuse (7.4%) or dependence (7.7%) in the past year |

| Wu 2011, USA | Cross-sectional 2001-2002 | 2450 participants in the 2001-2002 National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism survey | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Substance use [DSM-IV] | Comparing prescription opioid disorder users vs users of non-opioid drugs, odds of any drug use disorder was increased among opioid users (AOR=1.31 [1.02-1.69]) |

| F30 – F39: Mood [affective] disorders | ||||||

| Ali 2015, USA | Cross-sectional 2008-2012 | 84,800 adolescents in the 2008-2012 NSDUH; mean age: 14.49 years | Lifetime NMPOU | 4 | Major depressive episode [Propensity scoring] | Adolescents who used prescription drugs non-medically were 33% to 35% more likely to experience major depressive episodes compared to their non-abusing counterparts (P < 0.05) |

| Barth 2013, USA | Case-control | Cases: 86 participants with current PO dependence; Controls:41 healthy participants in a larger study on stress; mean age: 35.4 years | Past 30 days NMPOU | 4 | Psychiatric disorders [ASI Lite] | Among individuals with prescription opioid dependence, prevalence of psychiatric disorders was: major depressive disorder 12.9%; panic disorder 20%; generalised anxiety disorder 14.1% |

| Barth 2014, USA | Cross-sectional | 307 individuals with non-alcoholic chronic pancreatitis ;mean age: 51 years | Past 30 days medication usage | 4 | Depressive symptoms [CESD] | A high opioid misuse measure score was associated with increased score on the depressive symptoms measurement scale (β = 0.38, P <0.0001) |

| Becker 2007, USA | Cross-sectional 2002-2004 | 6879 respondents in the NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Depression [CIDI-SF] | Past-year non-medical use of prescription opioids was significantly associated with depressive symptoms [AOR=1.2 (1.01–1.5)] |

| Bohnert 2013, USA | Cross-sectional 2009 | 351 adults in a residential treatment program; mean age: 35.6 years | Past month NMPOU, Lifetime use | 4 | Depression [PHQ-9] | NMPOU was significantly associated with depression (AOR=1.06 [1.01-1.11], P=0.01) |

| Bouvier 2019, USA | Cross-sectional 2015-2016 | 199 young adults treatment program; mean age: 35.6 years | Past month NMPOU, Lifetime use | 3 | Diagnosed for depression | NMPOU use was significantly associated with a depressive disorder (AOR=1.51 [1.14-1.99], P <0.01) |

| Carrieri 2003, USA | Prospective 1995-2000 | 114 HIV-infected patients on buprenorphine maintenance treatment; mean age: 33.6 years | Buprenorphine injection misuse during the previous 6 months | 2 | Depression [CESD] | Depression was associated with injection misuse in the stabilised (ARR=1.04 [1.01-1.06]) and un-stabilised (ARR=1.05 [1.01-1.09]) phase of treatment |

| Edlund 2007, USA | Cross-sectional 1996-1997 | 9279 participants from a nationally representative study of the US civilian population | NMPOU in past 12 months | 4 | Depression | Depression was significantly [CIDI] associated with self-reported opioid misuse (OR = 2.23 [1.71-2.90], P < 0.001) |

| Edlund 2015, USA | Cross-sectional 2008-2012 | 112,600 adolescents aged 12–17, and 7100 adolescents aged 12–17 | Past year NMPOU | 4 | MDE [NCS-A] | MDE was associated with NMPOU among all adolescents (OR = 1.51, P <0.001); in the sample of adolescents with NMPO use, 20% reported past year MDE |

| Fink 2015, USA | Cross-sectional 2011-2012 | 113655 participants in the 2011 and 2012 NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | MDE [DSM-IV] | Among adolescent and adult respondents, 5.8% and 4.5% reported any past-year NMPO respectively, while 8.6% and 6.8% met criteria for past-year MDE respectively |

| Grattan 2012, USA | Cross-sectional 2008-2009 | 1334 patients on chronic opioid therapy for non-cancer pain who had no history of substance abuse | NMPOU in past 2 weeks | 4 | Depression [PHQ-8 score] | Prescription opioid misuse was significantly associated with moderate depression (OR=1.75 [1.05-2.91, P=0.031]) and severe depression (OR=2.42 [1.46-4.02, P=0.001]) |

| Green 2009, USA | Retrospective 2005-2008 | 29,906 respondent assessments from 220 treatment centres; mean age: 34.9 years | Past 30 days use of any prescription opioid | 2 | Depression [ASI-MV] | Prescription opioid abuse was associated with increased odds of depression in males (AOR=1.29 [1.09-1.53]) but not significant in females (AOR=1.15 [0.96-1.38]) |

| Mackesy-Amiti 2015, USA | Cross-sectional 2008-2010 | 570 PWIDs recruited through street outreach and respondent driven sampling; mean age: 22.2 years | Past year and lifetime prescription opioid injection | 4 | Substance-induced major depression [DSM-IV] | Past year PO misuse was significantly associated with past year substance-induced major depression (AOR=1.81 [1.16–2.83]) |

| Martel 2014, USA | Cross-sectional | 82 patients with chronic pain being prescribed POs; mean age: 48.7 years | Past month NMPOU | 4 | Depression [self-report] | Depression (r = 0.25, P < 0.05) was significantly associated with prescription opioid misuse |

| Martins 2009, USA | Cross-sectional 2005-2006 | 8218 respondents in the NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | MDE [NCS-R and NCS-A] | Past year opioid users were significantly more likely to have past year MDE (AOR=1.4 [1.2-1.6]), compared to users of other illegal drugs |

| Martins 2012, USA | Prospective 2001-2002; 2004-2005 | 34653 respondents in the NESARC | NMPOU over lifetime, past-year, or since last interview | 2 | Major depressive disorder [DSM-IV] | Baseline lifetime NMPOU was associated with incident major depressive disorder (AOR=1.4 [1.1-1.9]) |

| Mason 2016, USA | Cross-sectional 2015 | 625 neurosurgery and orthopedic patients | NMPOU in the past 2 weeks | 4 | Depression [PROMIS] | Symptoms of depression symptoms experienced in the past week was significantly related to NMPOU in the past 2 weeks (AOR=1.16 [1.01-1.33]) |

| Morasco 2008, USA | Randomised trial 2006-2007 | 127 patients recruited from a veteran’s affairs medical centre; mean age: 59.8 years | Lifetime NMPOU | 1 | Depression [DSM-IV] | Participants reporting PO misuse were more likely to meet criteria for major depression (22% vs 3.7%, P=0.008) |

| Nugraheni 2020, USA | Cross-sectional 2016 | 40,632 respondents in the NSDUH | Past-year NMPOU | 4 | Major depressive episode | NMPOU associated with major depressive episode in past year (AOR=2.99 [2.47-3.62]) |

| Price 2011, USA | Cross-sectional 2008-2009 | 351 patients seeking treatment from a drug and alcohol treatment program; mean age: 35.8 years | NMPOU in past 30 days | 4 | Depressive symptoms [PHQ] | Prescription opioid misuse was associated with greater depressive symptoms (AOR=1.09 [1.01-1.18]) |

| Rigg 2015, USA | Cross-sectional 2010-2013 | 10201 respondents in the NSDUH; 18 years or older | Past-year NMPOU | 4 | Major depressive episode | NMPO users were not more likely to have experienced a major depressive episode in the past year compared to heroin users (AOR=0.774 [0.441-1.360] P-value=0.373) |

| Saha 2016, USA | Cross-sectional 2012-2013 | 36309 respondents in the NESARC-III | Past-year and lifetime NMPOU | 4 | Major depressive disorder | Past-year NMPOU was significantly related to having a major depressive disorder (AOR=1.26 [1.05-1.52]) and persistent depression (AOR=1.43 [1.06-1.92]) |

| Sobieraj 2012, USA | Cross-sectional | 1334 patients treated with chronic opioids | NMPOU in past 2 weeks | 4 | Depression [self-report] | Prescription opioid misuse was significantly associated with moderate depression (AOR=1.75 [1.05-2.91]) or severe depression (AOR=2.42 [1.46-4.02]) |

| Tang 2016, China | Cross-sectional 2012 | 18686 Chinese high school students age 11-20; mean age: 15.43 | Lifetime, past-year, and past-month NMPOU | 4 | Depressive symptoms [CES-D] | Depressive symptoms were more prevalent among participants reporting past-month NMPOU (16.6%) than non-users (8.8%); P-value <0.0001 |

| Wheeler 2019, USA | Cross-sectional | 208 African-American male prisoners | Lifetime NMPOU | 4 | Lifetime severe anxiety (ASI-V) | Lifetime NMPOU was associated with severe anxiety (AOR=3.97 [1.58-9.86]) |

| Wu 2011, USA | Cross-sectional 2001-2002 | 2450 participants in the 2001-2002 National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism survey | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Mood disorder [DSM-IV] | Comparing prescription opioid users vs users of non-opioid drugs, odds of any mood disorder wasincreased among opioid users (AOR=1.07 [0.82-1.40]), though relationship was not statistically significant |

| Zale 2015, USA | Cross-sectional | 24348 participants in the 2009 NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Major depressive episode (MDE) [DSM-IV criteria] | Past year NMPOU was associated with past year MDE (AOR=2.44 [1.88-3.17], P <0.001) |

| F40 - F48: Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders | ||||||

| Becker 2007, USA | Cross-sectional 2002-2004 | 6879 respondents in the NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Panic disorder, social phobia [CIDI-SF] | Past-year non-medical use of prescription opioids was significantly associated with panic symptoms [AOR=1.2 (1.04–1.5)], and phobic symptoms [AOR=1.2 (1.1–1.4)] |

| Boyd 2014, USA | Cross-sectional 2009-2010 | 2627 secondary school students; mean age: 14.8 years | Lifetime NMPOU | 4 | Anxiety [YSR version of CBCL] | NMPOU associated with anxiety in 14.6% of sensation seekers and associated with anxiety in 3.3% of non-medical self-treaters |

| Feingold 2017, Israel | Cross-sectional | 544 chronic pain patients | NMPOU use in past 30 days | 4 | Anxiety [GAD-7] | Patients who screened positive for anxiety were significantly more likely to screen positive for PO misuse than those without anxiety (AOR=2.18 [1.37-4.17]) |

| Hall 2016, USA | Cross-sectional | 406 victimised women on probation or parole; mean age: 37.2 | Lifetime and past year NMPOU | 4 | Post-traumatic stress diagnostic scale | Participants who met diagnostic criteria for PTSD were more likely to report NMPOU (AOR=1.1 [0.61-1.8]) |

| Kerridge 2015, USA | Cross-sectional 2012-2013 | 36309 noninstitutionalised adults residing in house-holds and selected group quarters | Lifetime and past year NMPOU | 4 | PTSD [DSM-5] | Past year NMPOU was associated with PTSD in men: (AOR=1.47 [1.04–2.09]), and women: (AOR=1.41 [1.05–1.91]) |

| Mackesy-Amiti 2015, USA | Cross-sectional 2008-2010 | 570 PWIDs recruited through street outreach and respondent driven sampling; mean age: 22.2 years | Past year and lifetime prescription opioid injection | 4 | PTSD [DSM-IV] | Past year PO misuse was significantly associated with prior PTSD (AOR=2.45 [1.31–4.60]) |

| Martel 2014, USA | Cross-sectional | 82 patients with chronic pain being prescribed POs; mean age: 48.7 years | Past month NMPOU | 4 | Anxiety [self-report] | Anxiety (r =0.31, P <0.01) was significantly associated with prescription opioid misuse |

| Martins 2009, USA | Cross-sectional 2005-2006 | 8218 respondents in the NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Anxiety [self-reported] | Past year opioid use was not significantly associated with past year anxiety disorder (AOR=1.2 [0.9-1.4]) |

| Martins 2012, USA | Prospective 2001-2002; 2004-2005 | 34653 respondents in the NESARC | NMPOU over lifetime, past-year, or since last interview | 2 | Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) [DSM-IV] | Baseline lifetime NMPOU was associated with incident GAD (AOR=1.5 [1.1-2.1]) |

| Mason 2016, USA | Cross-sectional 2015 | 625 neurosurgery and orthopedic patients | NMPOU in the past 2 weeks | 4 | Anxiety | Symptoms of anxiety experienced symptoms in the past week were not [PROMIS] significantly related to NMPOU in the past 2 weeks (AOR=1.00 [0.89-1.11]) |

| Saha 2016, USA | Cross-sectional 2012-2013 | 36309 respondents in the NESARC-III | Past-year and lifetime NMPOU | 4 | PTSD | NMPOU was significantly related to having PTSD (12-month AOR=1.41 [1.13-1.75]; lifetime AOR = 1.30 [1.11-1.51]) |

| Smith 2016, USA | Cross-sectional 2004-2005 | 34653 respondents in the NESARC-III | Past-year and lifetime NMPOU | 4 | Past-year and lifetime PTSD diagnosis | Prevalence of a lifetime PTSD diagnosis was greater in those traumatic stress reporting NMPOU (19.8%) compared to non-users (9.3%). Prevalence of a past-year PTSD diagnosis was also greater in NMPO users (14.6%) compared to non-users (6.3%). Past-year PTSD diagnosis was associated with increased odds of past-year NMPOU (AOR=0.91, P <0.001) |

| Wu 2011, USA | Cross-sectional 2001-2002 | 2450 participants in the 2001-2002 National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism survey | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Anxiety [DSM-IV] | Comparing prescription opioid users vs users of non-opioid drugs, odds of any anxiety disorder was increased (AOR=1.28 [0.98-1.66]) though relationship was not statistically significant |

| Xiao 2019, China | Cross-sectional 2015 | 159640 adolescents enrolled in the School-Based Chinese Adolescents Health Survey | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Past-year sleep disturbances | Past year NMPOU use associated past month sleep disturbances among boys (AOR=2.07 [1.66-2.58]) and girls (AOR=2.16 [1.68-2.77]) |

| F00 – F99: Other psychiatric/mental health measures | ||||||

| Back 2010, USA | Cross-sectional 2006 | 55,279 respondents in the NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Psychological distress | NMPOU was significantly associated with having serious psychological stress in females (AOR: 1.65 [1.24-2.18]) but not significant in males (AOR=1.26 [0.85-1.85]) |

| Becker 2011, USA | Retrospective 2006-2008 | 3238 respondents in the NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 2 | Psychological distress [Kessler 6 inventory] | Serious psychological distress was present in 27.6% of participants |

| Boyd 2014, USA | Cross-sectional 2009-2010 | 2627 secondary school students; mean age: 14.8 years | Lifetime NMPOU | 4 | Conduct disorder | Nonmedical prescription opioid use was associated with conduct disorder in 46.3% of sensation seekers |

| Buttram 2014, USA | Clinical trial 2008-2010 | 515 MSM participating in a risk reduction intervention trial; mean age: 38.9 years | Past year and past 90 days injection NMPOU | 2 | Severe mental distress [GMDS] | Nonmedical prescription opioid use was associated with higher odds of severe mental distress (OR=1.72 [1.13-2.61]); P=0.011); severe mental distress prevalence: 57.9% |

| Chan 2020, USA | Cross-sectional 2016 | 11489 adolescent respondents in the NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Past-year major depressive episode | Past year NMPOU was significantly associated with a past-year major depressive episode (AOR=1.60 [1.11-2.32]) |

| Darke 1996, Australia | Cross-sectional | 312 persons who inject drugs (PWID) recruited through street outreach; mean age: 28.8 years | Injection NMPOU in last 6 months | 4 | Psychological distress [GHQ score] | Methadone injectors had increased psychological distress (GHQ score: 10.2 vs. 7.8, P <0.05), and met diagnostic cut-off for psychopathology (67% vs 54%, P <0.05) |

| Fischer 2013, Canada | Cross-sectional 2010-2011 | 4023 adults and 3339 grade 7–12 public system students; students’ mean age: 15.9 years; adults’ mean age: 46.3 years | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Psychological distress [PHQ-2] | NMPOU was not significantly associated with increased odds of psychological distress among students (AOR=1.14 [0.76-1.70] nor among adults (AOR=1.63 [0.95-2.80] |

| Hruschak 2020, Australia | Cross-sectional 2014-2015 | 333 patients filling prescriptions at community pharmacies | Current NMPOU (Prescription Opioid Misuse Index) | 4 | Depression | Taking more medications than prescribed was significantly associated with depression (P <0.05) |

| Kozhimannil 2017, USA | Cross-sectional 2005-2014 | 8721 NSDUH respondents; women who were pregnant at the time of survey | Past-year, past-month NMPOU | 4 | Depression or anxiety | Among pregnant women, depression or anxiety in the past year was strongly associated with NMPOU in the past year (AOR=2.15 [1.52-3.04]). Past-year depression or anxiety was also associated with greater odds of past-month NMPOU (AOR=1.90 [1.10-3.30]) |

| Kerridge 2015, USA | Cross-sectional 2012-2013 | 36,309 non-institutionalised adults residing in house-holds and selected group quarters | Lifetime to past year NMPOU | 4 | Personality disorders [DSM-5] | Past year NMPOU was associated with any personality disorder in men: (AOR=1.93 [1.52–2.45]), and women: (AOR=1.45 [1.13–1.86]) |

| Mackesy-Amiti 2015, USA | Cross-sectional 2008-2010 | 570 PWIDs recruited through street outreach and respondent driven sampling; mean age: 22.2 years | Past year and lifetime prescription opioid injection | 4 | Antisocial personality disorder [DSM-IV] | Past year PO misuse was significantly associated with increased odds of antisocial personality disorder (AOR=2.15 [1.43–3.24]) |

| Martins 2007, USA | Cross-sectional 2002-2003 | 7810 respondents in the 2002-2003 NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Mental health problems [CIDI] | Prescription opioid dependence was significantly associated with serious mental health problems (AOR=2.34 [2.04-2.69]) |

| Martins 2015, USA | Cross-sectional 2008-2010 | 4421 respondents in the NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Psychological distress [Kessler 6] | NMPOU was significantly associated with past-year serious psychological distress (AOR=2.09 [1.89–2.31]) |

| Morizio 2017, USA | Retrospective cohort study 2010-2015 | 923 patients admitted to a medical centre for heroin or non-heroin opioid overdose event; median age: 24 | Lifetime history of NMPOU | 2 | History of bipolar schizophrenia | History of bipolar schizophrenia was more prevalent among those with non-heroin opioid overdose (7.3%), compared to the heroin overdose group (2.5%), P <0.0014 |

| Novak 2016, Denmark, Germany, Great Britain, Sweden | Cross-sectional 2014 | 22,070 survey respondents in the European Union ages 12-49 | Lifetime and past year NMPOU | 4 | Serious psychological distress [K9] | NMPO users were more likely to report non-specific psychological distress (AOR=3.2 [2.6-3.9]) |

| Ouellet 2012, USA | Cross-sectional 2002-2005 | 645 non-injecting heroin users recruited through street outreach and respondent driven methods | Lifetime history of NMPOU | 4 | Psychiatric disorder [self-reported] | Being diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder was associated with PO use prior to heroin initiation (AOR=2.2 [1.2-4.1) |

| Rigg 2015, USA | Cross-sectional 2010-2013 | 10,201 respondents in the NSDUH;18 years or older | Past-year NMPOU | 4 | Psychological distress | NMPO users were not more likely to have experienced psychological distress in the past year compared to heroin users (AOR=0.876 [0.537-1.428] P-value=0.596) |

| Romach 1999, Canada | Cross-sectional | 339 long term codeine users recruited through newspaper adverts; mean age: 44 years | Past year codeine use | 4 | Psychological problems [self-reported] | A fraction of the subjects identified depression (13%) and worry (12%) as psychological consequences of long term codeine use |

| Saha 2016, USA | Cross-sectional 2012-2013 | 36309 respondents in the NESARC-III | Past-year and lifetime NMPOU | 4 | Any personality disorder | NMPOU was significantly related to having any personality disorder (12-month AOR=1.70 [1.45-1.99]; lifetime AOR = 1.97 [1.75-2.22]) |

| Shield 2011, Canada | Cross-sectional 2008-2009 | 2030 participants in the 2008-2009 Center for Addiction and Mental Health monitor | NMPOU in past 12 months | 4 | Psychological distress [GHQ-12] | NMPOU was associated with increased odds of psychological distress in men (AOR=7.55 [2.87-19.88]) and women (AOR=4.21, 1.61-11.00]) |

| Sproule 1999, Canada | Cross-sectional | 399 regular users of codeine recruited through newspaper adverts; mean age: 43.5 years | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Mental health problems [self-report] | Significantly more subjects that were codeine dependent had sought help for a mental health problem (P <0.001) |

| Subramaniam 2009, USA | Cross-sectional | 94 adolescents (ages 14-17 years) with past year diagnosis of opioid use disorder; mean age:16.9 years | NMPOU in past 30 days | 4 | Psychiatric disorders [DICA-IV] | Prescription opioid users presented with higher rates of current ADHD (P=0.01) and manic episodes (P=0.04) |

| Tetrault 2007, USA | Cross-sectional 2003 | 55,230 participants in the 2003 NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Serious mental illness [Kessler inventory] | Past year NMPOU was significantly associated with increased odds of serious mental illness in females (AOR=1.67 [1.29-2.17]) but not significantly associated with increased odds in males (AOR=1.25 [0.91-1.70]) |

| Tragesser 2013, USA | Cross-sectional | 606 students aged 18 to 52 taking psychology courses; mean age: 20.4 years | NMPOU in past 3 months | 4 | Borderline personality disorder [PAI-BOR] | Opioid misuse and dependence features were positively associated with heightened levels of borderline personality disorder features (P <0.001) |

| Uosukainen 2014, Finland | Cross-sectional 2001-2008 | 1227 clients seeking treatment for buprenorphine and amphetamine abuse; mean age: buprenorphine users 25.8 years, amphetamine users 27.6 years | Current and lifetime NMPOU | 4 | Psychotic symptoms [self-reported] | Buprenorphine abuse was associated with reduced odds of psychotic symptoms (AOR=0.33, [0.24-0.45], P <0.001) |

| Vietri 2014, USA | Cross-sectional 2010, 2011 | 25,864 participants in the 2010 and 2011 US National Health and Wellness Survey | NMPOU in the 3 months prior to the survey (modes of use: chewing, smoking, snorting, rectal, injecting) | 4 | Psychiatric conditions [self-reported] | PO abuse was significantly associated with self-reported psychiatric conditions (AOR=1.71 [1.28-2.27], P=0.0002) |

| Wang 2013, USA | Cross-sectional 2008-2009 | 75,964 participants in the 2008-2009 NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Psychological distress [K6 scale] | Non-medical use of prescription opioids was associated with increased odds of psychological distress in urban (AOR=1.64 [1.41–1.89]) and rural residents (AOR=1.63 [1.23–2.17]) |

| Wasan 2007, USA | Prospective | 288 patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain; mean age: 50.5 years | Current NMPOU | 2 | Psychiatric morbidity [PDUQ] | Presence of psychiatric morbidities such as mood disorders, psycho-social stressors, and psychologic problems was associated with self-reported measures of prescription opioid misuse (COMM P <0.01, SOAPP P <0.05) |

|

XI. Diseases of skin and subcutaneous tissue

L00 – L99: Infections of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | ||||||

| Ambekar 2015, India | Cross-sectional | 902 male PWID recruited from harm reduction centres; mean age: 33.4 years | Injection PO use in past 3 months | 4 | Abscess, blocked veins [self-reported] | Prescription opioid injectors were significantly more likely to develop abscess or blocked veins ever in their injecting life (Abscess: RR=1.39 [1.05-1.85]; blocked veins: RR=2.513 [1.89-3.35]) |

| Darke 1996, Australia | Cross-sectional | 312 PWID recruited through street outreach; mean age: 28.8 years | Injection PO use in last 6 months | 4 | Thrombosis, abscess [self-reported] | Methadone injection was associated with abscesses and infections (OR=2.4 [1.3-4.4]), and thrombosis (OR=2.2 [1.1-4.6]); prevalence of abscesses and infections: 23%; prevalence of thrombosis: 16% |

| Degenhardt 2006, Australia | Cross-sectional 2001-2004 | 795 PWID recruited through street outreach; mean age: 33.8 years | Injection PO use in last 6 months | 4 | Injection site harms (difficulty finding veins, bruising/scarring) [self-reported] | After covariate adjustment, recent morphine injection was not significantly associated with injection site harms; prevalence of difficulty finding veins was 36%, prevalence of scarring or bruising was 27% |

| Jenkinson 2005, Australia | Cross-sectional 2002 | 156 respondents in the Melbourne arm of the Illicit Drug Reporting System; mean age: 30 years | Injection PO use in last 6 months | 4 | Injection-related health problems (overdose, bruising abscesses, scarring, thrombosis) [self-reported] | Buprenorphine injection was not significantly associated with increased odds of injection-related health problems (AOR=2.9 [0.98-8.8]) |

|

XVI. Certain conditions originating in the perinatal period

P05-P08: Disorders related to length of gestation and fetal growth | ||||||

| Almario 2009, USA | Retrospective 2000-2006 | 258 opiate-addicted women treated with methadone; mean age of mothers with preterm delivery: 28.7 years | Current NMPOU | 2 | Preterm delivery | NMPOU in mothers treated for addiction was not significantly associated with lower odds of preterm birth (AOR=0.9 [0.4-2.2]) |

| Liu 2010, Australia | Retrospective 2000-2006 | 215 opioid dependent mothers; median age: 27.2 years | Current NMPOU | 2 | IUGR [ICD-10-AM] | Risk of IUGR is higher in non-smoking opioid dependent mothers compared to non-smoking non-opioid dependent mothers (RR=3.48 [1.70-7.14]) |

| Maeda 2014, USA | Retrospective 1998-2011 | 113,105 hospitalisations for delivery identified in the nationwide inpatient sample | 2 | Stillbirth, IUGR preterm labor, [ICD-9-CM] | Maternal opioid abuse or dependence was associated with stillbirth (AOR=1.5 [1.3-1.8]), preterm labor (AOR=2.1 [2.0-2.3]), IUGR (AOR=2.7 [2.4-2.9]), maternal death during hospitalisation (AOR=4.6 [1.8-12.1]) | |

| P90 – P96: Other disorders originating in the perinatal period | ||||||

| Kelly 2011, Canada | Retrospective 2009-2010 | 482 live births that occurred at a Canadian health centre; mean age: 24.5 years | Oral use, snorting or injection of opioids (most commonly oxycodone) | 2 | NAS [Infant Finnegan scores] | Narcotic-exposed neonates experienced NAS 29.5% of the time; daily maternal use was associated with a higher rate of NAS (66.0%) |

| Lee 2015, USA | Retrospective 2007-2013 | 139 cases of NAS pooled from a large Medicaid health plan | In utero exposure to prescription opioids | 2 | NAS [ICD-9], hospital length of stay | In utero exposure to methadone or buprenorphine leads to an average NICU length of stay of 21 days for NAS treatment |

| McQueen 2015, Canada | Retrospective 2010-2011 | 131 infant/mother pairs with NAS symptoms and maternal substance abuse; mean age of mothers at delivery: 25.6 years | In utero exposure to prescription opioids | 2 | NICU admission; NAS [MFS tool] | Among the eligible sample of infants, 78.6% were admitted to the NICU and 72.5 % of eligible sample received pharmacologic treatment for NAS |

|

XVIII. Symptoms, signs, and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings not elsewhere classified

R40-R46. Symptoms and signs involving cognition, perception, emotional state and behaviour | ||||||

| Ashrafioun 2017, USA | Cross-sectional 2014 | 24,653 respondents in the NSDUG | Past-year NMPOU | 4 | Suicidal ideation [self-reported] | Past-year suicidal ideation was significantly associated with less than monthly (AOR=1.52 [1.21-1.91]), monthly to weekly (AOR=1.41 [1.04-1.93]), and weekly or more (AOR=1.62 [1.19-2.21]) NMPOU in the past year |

| Barman-Adhikari 2019, USA | Cross-sectional 2016-2017 | 1426 young adults experiencing homelessness | Past-month NMPOU | 4 | Lifetime suicidal ideation | Past-month NMPOU was associated with lifetime suicidal ideation (AOR=1.8 [1.1-3.0]) |

| Bohnert 2013, USA | Cross-sectional 2009 | 351 adults in a residential treatment program; mean age: 35.6 years | Past month NMPOU Lifetime use | 4 | Suicidal ideation [BSS] | Non-medical PO use was not significantly associated with suicidal ideation (AOR=1.01 [0.95-1.07]) |

| Epstein-Ngo 2014, USA | Prospective | 575 patients in an urban emergency department who screened positive for past 6 months drug use; mean age: 20 years | NMPOU in past 6 months | 2 | Aggression [TLFB-AM] | Prescription opioid misuse was more likely immediately prior to dating violence than non-dating violence (AOR=6.24 [2.81-13.88]) |

| Fischer 2013, Canada | Cross-sectional 2010-2011 | 4023 adults and 3339 grade 7–12 public system students; students’ mean age: 15.9 years; adults’ mean age: 46.3 years | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Suicidal ideation [self-reported] | Among students, NMPOU was significantly associated with suicidal ideation (AOR=2.13, [1.12-4.06]) |

| Guo 2016, China | Prospective longitudinal 2009-2010, 2011-2012 | 3273 adolescent students; mean age: 13.7 | Past-year NMPOU | 1 | Suicidal ideation | Baseline NMPOU was associated with suicidal ideation at one year follow-up (AOR=2.31 [1.30-4.11]) |

| Han 2017, USA | Cross-sectional 2015 | 51,200 respondents in the 2015 NSDUH identified as prescription opioid users | Lifetime and past-year NMPOU | 4 | Suicidal ideation | Among adults with prescription opioid misuse, prevalence of past-year suicidal ideation was 21.5% (95% CI 18.77-24.46) |

| Havens 2011, USA | Cross-sectional 2001-2004 | 800 felony probationers recruited into a HIV-prevention trial; median age: 32.3 years | Lifetime PO injection | 4 | Risky behaviour [self-reported] [reported] | Participants indicating lifetime injection of POs were 14.7 times more likely to have reported participating in risky injection behaviours (AOR=14.7 [7.7-28.1]) |

| Humeniuk 2003, Australia | Cross-sectional 1996-1997 | 365 heroin users recruited through snowball sampling; mean age: 28.9 years | Injection PO use in last 6 months | 4 | Risky behaviour [self-reported] | Methadone injectors were significantly more likely to use other drug types intravenously than non-injectors of methadone, both on a life-time scale (F =48.0, df=1, 362, P=0.000) and over the last 6 months (F=15.4, df=1, 362, P=0.000) |

| Kuramoto 2011, USA | Cross-sectional 2009 | 37,933 respondents in the NSDUH | Lifetime and past year NMPOU | 4 | Suicidal ideation [self-reported] | NMPOU was significantly associated with suicidal ideation (AOR=1.88 ([1.13-3.12]) |

| Lin 2015, USA | Cross-sectional | 1076 youths ages 12–18, presenting to primary care community health clinics in two urban settings | NMPOU in past 3 months | 4 | Delinquency [self-reported] | NMPOU was significantly associated with non-violent delinquency (OR=1.06 [1.01-1.12]) |

| Rigg 2019, USA | Cross-sectional 2012-2016 | 22,693 respondents in the NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Suicide planning and attempts | No significant differences in suicidality between participants who engage in NMPOU use in urban (AOR=1.20 [0.67-2.13]) and rural settings (AOR=2.12 [0.43-10.55]) |

| Schepis 2019, USA | Cross-sectional | 17,608 adult respondents in the NSDUH | Past-year NMPOU | 4 | Suicidal ideation | NMPOU was significantly associated with suicidal ideation (AOR=1.84 [1.07-3.19]) |

| Tang 2016, China | Cross-sectional 2012 | 18,686 Chinese high school students age 11-20; mean age: 15.43 | Lifetime, past-year, and past-month NMPOU | 4 | Suicidal ideation | Suicidal ideation was more prevalent among participants reporting past-month NMPOU (34.9%) than non-users (21.2%); P-value <0.0001 |

| Wilkins 2021, USA | Cross-sectional 2019 | 13,667 high school students enrolled in the Youth Risk Behavior Survey | Current NMPOU | 4 | Past-year suicidal ideation, planning and attempts | Current NMPOU significantly associated with higher prevalence ratios for suicidal ideation (APR=2.30 [1.97-2.69]), planning (APR=2.33 [1.99-2.79]) and attempts (APR=3.21 [2.56-4.02]) |

| Young 2012, USA | Cross-sectional 2009-2010 | 2597 middle and high school students enrolled in two school districts, mean age: 14.8 years | NMPOU in past 12 months | 4 | Aggressive behaviour [YSR version of CBCL] | Sensation seeking non-medical use of prescription opioids was associated with rule breaking behaviour, high risk of substance dependence, and aggressive behaviour |

| R50-R69: General symptoms and signs | ||||||

| Becker 2007, USA | Cross-sectional 2002-2004 | 6879 respondents in the NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | General health status [self-reported] | Respondents meeting criteria for abuse/dependence were more likely to self-report fair/poor health (AOR 2.1 [1.4–3.0]) |

| Black 2013, USA | Cross sectional 2007-2011 | 29,459 PO users recruited from 540 treatment facilities; mean age=33.1 years | Past 30 days NMPOU | 4 | General health status (liver disease, ER visit) [ASI-MV criteria] | Prescription opioid injection was significantly associated with liver disease (OR=1.71 [1.53-1.90], P < 0.0001]) and visit to the ER in the past 30 days (OR=1.84 [1.71-1.98], P <0.0001). |

| Brunet 2015, Canada | Cross-sectional 2013 | 1238 HIV/HCV co-infected persons [800 in prevalence cohort, 582 in incidence cohort] | Injection PO use in past 6 months | 4 | General health status (liver fibrosis progression) [APRI score] | Prescription opioid injection was associated with faster progression to liver fibrosis [hazard odds ratio=1.20 (0.73-1.67)] though the association was not statistically significant |

| Catalano 2011, USA | Prospective | 912 students from 1st or 2nd grade to age 21; mean age: 16.2 years | Past year and lifetime NMPOU | 2 | General physical [self-reported] and mental health consequences [CIDI] | Ever use of NMPO was associated with a 7.9 greater odds of having a current drug use disorder, 2.1 greater odds of a mood disorder, 1.4 greater odds of poor/fair health, 2.6 greater odds of being violent |

| Choo 2014, USA | Retrospective 2011 | 426,010 DAWN-defined visits involving prescription opioid | NMPOU at emergency department presentation | 2 | ED presentation | Use of prescription opioids was associated with decreased odds of hospital admission in females (AOR=0.65 [0.54–0.77]) and males (AOR=0.62 [0.46–0.83]) |

| Fischer 2013, Canada | Cross-sectional 2010-2011 | 4023 adults and 3339 grade 7–12 public system students; students’ mean age: 15.9 years; adults’ mean age: 46.3 years | Past year NMPOU | 4 | Physical health [self-reported] | NMPOU was not significantly associated with self-reported poor/fair health among students (AOR=1.30 [0.69-2.46] nor among adults (AOR=1.41 [0.79-2.52]) |

| Green 2009, USA | Retrospective 2005-2008 | 29,906 respondent assessments from 220 treatment centres; mean age: 34.9 years | Past 30 day NMPOU | 2 | >5 ER visits in past 30 days [self-reported] | Prescription opioid abuse was associated with marginally increased odds of ER visits in males (AOR=1.06 [0.56-2.03]) and in females (AOR=1.75 [0.97-3.14]), though the associations were not statistically significant |

| Griffin 2015, USA | Clinical trial | 653 prescription opioid dependent patients; mean age: 33.2 years | Current NMPOU dependence | 2 | Health-related quality of life [SF-36] | Prescription opioid-dependent patients had worse physical and mental quality of life than a healthy population or a general population [mental scores=15.3 points vs healthy population and 12.3 points vs general population; physical scores=7.1points vs healthy population and 1.7 points vs general population] |

| Han 2017, USA | Cross-sectional 2015 | 51,200 respondents in the 2015 NSDUH identified as prescription | Lifetime and past-year NMPOU | 4 | Hypertension | Among adults with prescription opioid misuse, prevalence of hypertension was 6.0% (95% CI, 5.06-7.03) |

| Hartwell 2014, USA | Case-control | 68 non-treatment seeking individuals recruited through advertisements (33 PO dependent cases and 35 healthy controls) | NMPOU in the one month prior to baseline visit | 3 | Sleep quality [PSQI and ISI] | Poor sleep quality was identified in 80.6% of the PO dependent group, as compared to 8.8% of the control group (P <0.001) |

| Jeevanjee 2014, USA | Cross-sectional 2007-2008 | 258 HIV positive individuals recruited from homeless shelters, free meal programs, and single room occupancy hotels; mean age: 48 years | NMPOU use in past 90 days | 4 | Treatment adherence [self-reported] | PO misuse was significantly associated with an increased odds of incomplete adherence to treatment (AOR=1.47 [1.06-2.03]) |

| Mason 2016, USA | Cross-sectional 2015 | 625 neurosurgery and orthopedic patients | NMPOU in the past 2 weeks | 4 | Pain and depression [PROMIS] | Interaction between pain and depression experienced in the past week was significantly associated with NMPOU (AOR=0.96, [0.92-0.99]) |

| McCabe 2013, USA | Prospective 2009-2011 | 2050 middle and high school students from two public school districts | Past year NMPOU | 1 | Physical pain [YSR], pain [YSR] | NMPOU was not significantly associated with increased odds of physical pain in the previous 6 months during year 2 of study [OR=2.0, 0.7-5.6] |

| Morizio 2017, USA | Retrospective cohort study 2010-2015 | 923 patients admitted to a medical centre for heroin or non-heroin opioid overdose event; median age: 24 | Lifetime history of NMPOU | 2 | Hospital admission due to overdose | 84.6% of patients in the non-heroin opioid overdose group required hospital admission due to overdose compared to 72.2% of the heroin overdose group, P<0.0001 |

| Nielsen 2013, Australia | Cross-sectional 2011 | 141 participants recruited from opioid substitution treatment programs; mean age: 40.8 years | NMPOU in past 28 days | 4 | Pain [Brief Pain Inventory] | Any illicit PO use was associated with pain (OR=1.85 [0.78-4.39], though the association was not statistically significant |

| Patra 2009, Canada | Prospective 2004-2005 | 582 participants from the most recent follow-up in the OPICAN study; mean age: 35.2 years | NMPOU in past 30 days (non-injecting) | 4 | Personal health status [self-reported] | Among participants who majorly use prescription opioids, 55% reported poor or fair health status in past 30 days |

| Price 2011, USA | Cross-sectional 2008-2009 | 351 patients seeking treatment from a drug and alcohol treatment program; mean age:35.8 years | NMPOU in past 30 days | 4 | Physical functioning [SF-12] | Prescription opioid misuse was associated with lower physical functioning; as physical functioning increased (AOR=0.94 [0.91-0.98]), likelihood of NMPOU decreased |

| Schepis 2014, USA | Prospective 2001-2002, 2004-2005 | 34,653 participants in the NESARC | Lifetime NMPOU | 2 | Health related quality of life [SF-12] | NMPOU initiation was generally associated with poorest longitudinal outcomes for health related quality of life |

| Stein 2015, USA | Cross-sectional 2012-2013 | 328 primary care patients treated with buprenorphine; mean age: 38.7 years | NMPOU use in previous month | 4 | Pain [Brief Pain Inventory] | NMPOU was associated with moderate/severe chronic pain (OR=1.55 [0.29-8.23]), though the association was not statistically significant |

| Tang 2016, China | Cross-sectional 2012 | 18,686 Chinese high school students age 11-20; mean age: 15.43 | Lifetime, past-year, and past-month NMPOU | 4 | Poor sleep [CPSQI] | Past-year and lifetime NMPOU was significantly associated with poor sleep among participants (AOR=1.47 [1.17-1.85]; AOR=1.43 [1.28-1.60]) |

| Tetrault 2007, USA | Cross-sectional 2003 | 55,230 participants in the 2003 NSDUH | Past year NMPOU | 4 | >5 ER visits in past 1 year [self-reported] | Past year NMPOU was not significantly associated with increased odds of ER visits in females (AOR=1.77 [0.98-3.21]) nor reduced odds in males (AOR=0.74 [0.31-1.78]) |

| Vietri 2014, USA | Cross-sectional 2010, 2011 | 25864 participants in the 2010 and 2011 US National Health and Wellness Survey | NMPOU in the 3 months prior to the survey (modes of use: chewing, smoking, snorting, rectal, injecting) | 4 | Work productivity and general health [WPAI:GH] | PO tampering and abuse was associated with greater loss of productivity and increased use of health care (P <0.05) |

|

XIX. Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes

T36 – T50: Poisoning by drugs, medicaments and biological substances | ||||||

| Alexander 2004, USA | Retrospective 1997-2002 | 1,175,781 opioid-related emergency medical services patient encounters; mean age=35.4 year | Current NMPOU at patient encounter | 2 | Non-fatal overdose | Patients diagnosed as having poisoning or overdose increased by 47% over the study period |

| Black 2013, USA | Cross sectional 2007-2011 | 29,459 PO users recruited from 540 treatment facilities; mean age=33.1 years | Past 30 days NMPOU (oral route:90%; snorting:36%; injection:32%) | 4 | Non-fatal overdose | Prescription opioid injection was significantly associated with non-fatal overdose (OR: 1.32 [1.22-1.42], P <0.0001) |

| Bohnert 2013, USA | Cross-sectional 2009 | 351 adults in a residential treatment program; mean age: 35.6 years | Past month NMPOU, Lifetime use | 4 | Overdose, Addiction Severity Index, ASI] | Non-medical PO use was associated with past history of overdose (AOR=2.10 [1.10-4.02], P=0.03) |

| Bonar 2014, USA | Cross sectional 2008-2009 | 326 patients recruited from substance use disorder treatment centres; mean age: 35.1 years | Past 30 days NMPOU | 4 | Overdose | Past 30 days heavy NMPOU was associated with lifetime overdose (OR=2.99 [1.53-5.84]) |

| Brands 2004, Canada | Retrospective 1997-1999 | 178 new admission patients in a methadone maintenance treatment program; mean age: 34.5 years | Current PO injection | 2 | Overdose | Among those who inject prescription opioids-only, 46.5% reported ever overdosing on opioids |

| Bretteville-Jensen 2015, Norway | Cross sectional 2006-2013 | 1355 street-recruited PWID; mean age: 37 years | PO injection in past 4 weeks | 4 | Non-fatal overdose | Illicit use of buprenorphine was associated with an increased risk of non-fatal overdose, [OR=1.132, S.E=0.298] |

| Calcaterra 2013, USA | Retrospective 1999-2009 | All overdose deaths in the US among 15–64 year olds from 1999 to 2009 | Death certificate mention of PO | 2 | Fatal overdose | Age adjusted death rate related to pharmaceutical opioids increased almost 4-fold from 1999 to 2009 (1.54/100,000 p-y [95% CI 1.49-1.60] to 6.05/100,000 p-y [95% CI 5.95-6.16; P <0.001) |

| CDC 2011, USA | Retrospective 1999-2008 | 36,450 deaths that were attributed to drug overdose | Death certificate mention of PO | 2 | Fatal overdose | Opioid pain relievers were involved in 14,800 deaths (73.8%) of the 20,044 prescription drug overdose deaths |

| CDC 2013, USA | Retrospective 1999-2010 | 15,323 deaths among women that were attributed to drug overdose | Death certificate mention of PO | 2 | Fatal overdose | Deaths from opioid pain relievers increased fivefold for women and 3.6 times for men between 1999 and 2010 |

| CDC 2000, USA | Retrospective 1996-1999 data | 484 decedents where heroin or opiate intoxication was listed as a cause of death; median age: 40 years | Death certificate mention of PO | 2 | Fatal overdose | Opiate overdose death rate increased from 3.1 per 100,000 population in 1990 to 6.6 in 1999, an increase of 112.9% (P <0.001) |

| Challoner 1990, Canada | Retrospective 1977-1987 | 57 cases of overdose on pentazocine; median age: 28 years | Recent ingestion of pentazocine | 2 | Overdose | Reasons for overdose were attempted suicide (35 cases) excessive therapeutic use (11 cases) and drug abuse to obtain a “high” (11 cases) |

| Cheng 2020, Canada | Cross-sectional 2013-2016 | 599 people who report opioid use in past 6 months | Past six month NMPOU | 3 | Non-fatal overdose in past six months | No significant differences in non-fatal overdose risk among those who did and did not acquire opioids from physicians |

| Clayton 2019, USA | Cross-sectional 2017 | 14756 respondents in the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Grades 9-12) | Lifetime NMPOU | 2 | Past-year suicide planning and attempt | NMPOU associated with past-year suicide planning (AOR=2.41 [2.15-2.71]) and attempt (AOR=3.45, [2.86-4.17]) |

| Clayton 2019, USA | Cross-sectional 2017 | 3697 respondents in the Virginia Youth Survey (Grades 9-12) | Past-year and current NMPOU | 4 | Past-year suicide planning and attempt | Current NMPOU associated with past year suicide attempt (APR=2.18 [1.21-3.93]) |

| Darke 1996, Australia | Cross-sectional | 312 PWID recruited through street outreach; mean age: 28.8 years | Injection PO use in last 6 months | 4 | Overdose [self-reported] | Ever injecting methadone was associated with overdose (OR=2.2 [1.4-3.5]); also injectors of methadone in previous 6 months were more likely to overdose (OR=2.5 [1.4-4.6]) |

| Darke 2002, Australia | Cross sectional 1996-2000 | 788 PWID interviewed in Sydney; mean age: 28.6 years | Injection PO use in previous 6 months | 4 | Overdose | Among the methadone injectors, 72% had ever overdosed |

| Degenhardt 2009, Australia | Retrospective 1985-2006 | 42,676 people who entered opioid pharmacotherapy program | PO dispensations from the New South Wales Pharmaceutical Drugs of Addiction System linked to overdose events | 2 | Overdose | Drug overdose and trauma were the major contributors of death |

| Dhalla 2011, Canada | Cross sectional 2006 | Family physician of participants who were eligible for prescription drug coverage; other details from office of the chief coroner | Administrative prescription data on PO dispensation | 4 | Mortality related to opioid use | The number of opioid-related deaths increased across prescribing-volume quintiles (P <0.001) |

| Fernandes 2015, USA | Retrospective 2003-2012 | 358 Montana residents aged 18–64 years who died from unintentional PO poisoning | PO enrolment via Medicaid | 2 | Overdose | Age-adjusted mortality rate per 100,000 from opioid poisoning in Montana Medicaid adults was eight times higher than the rate for non-Medicaid Montana adults (38.2 [CI (30.7–45.7]) vs. 4.7 (CI (4.1–5.3)]) |

| Fischer 2004, Canada | Cross sectional 2002 | 651 illicit opioid users recruited from 5 Canadian cities; mean age: 34.8 years | Injection PO use in past 30 days | 4 | Overdose | Non-injection administration of hydromorphone in the past 30 days was a predictor of overdose episodes (OR=2.73 [1.37–5.46]) |

| Fischer 2008, Canada, USA | Cross-sectional 2004-2005 | 448 participants of which 304 (62.8%) were classified as prescription only users | Injection PO use in past 30 days | 4 | Overdose [self-reported], Emergency room use [self-reported] | PO use was associated with lower odds of ER use (OR=0.88, [0.41-1.87]) and associated with increased odds of overdose (OR=1.16 [0.32-4.18]), though the associations were not statistically significant |

| Green 2011, USA | Retrospective 1997-2007 | 2900 adult with accidental/undetermined drug intoxication deaths | Post mortem toxicology report of NMPOU | 2 | Fatal overdose | From 2001, intoxication deaths involving any prescription opioid increased from previous years, (linearly: 25.14, P <0.001) |

| Hakkinen 2010, Finland | Retrospective 2000-2008 | 12,891 subjects on which a post mortem toxicological analyses was performed | Post mortem toxicology report of NMPOU | 2 | Fatal overdose | Proportion of fatal prescription opioid poisonings out of all fatal drug poisonings increased from 9.5% (52 cases) in 2000 to 32.4% (179 cases) in 2008, being 22.3% over the whole period |

| Hall 2008, USA | Cross sectional 2006 | 295 residents who died of unintentional pharmaceutical overdoses; mean age: 39 years | Post mortem toxicology report of NMPOU | 4 | Fatal overdose [post mortem records] | Pharmaceutical diversion was associated with 186 (63.1%) deaths, while 63 (21.4%) were accompanied by evidence of doctor shopping |